Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3: considerations on the oldest continental...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3: considerations on the oldest continental...

DOI: 10.1127/0077-7749/2009/0251-0095 0077-7749/09/0251-0095 $ 3.50©2009 E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, D-70176 Stuttgart

N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh.2009, vol. 251/1, p. 95–108, Stuttgart, January 2009, published online 2009

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3:considerations on the oldest continental faunas from theGuadix Basin (Southern Spain)

Raef Minwer-Barakat, Antonio García-Alix, Granada & Barcelona, Elvira Martín-Suárezand Matthijs Freudenthal, Granada

With 4 figures and 2 tables

MINWER-BARAKAT, R., GARCÍA-ALIX, A., MARTÍN-SUÁREZ, E. & FREUDENTHAL, M. (2009): LateTurolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3: considerations on the oldest continentalfaunas from the Guadix Basin (Southern Spain). – N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh., 251: 95–108;Stuttgart.

Abstract: The fauna from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 (RCH-3), a new uppermost Miocene micro-mammal site from the Guadix Basin, is described. This level has yielded remains of Paraethomysmeini, Occitanomys alcalai, Stephanomys cf. dubari, Cricetinae indet., Erinaceidae indet., andSoricidae indet. This faunal assemblage can be assigned to the upper Turolian (MN13). The section ofRambla de Chimeneas is situated in the lower part of the oldest exclusively continental stratigraphicunit distinguished in the filling of the Guadix Basin. Other rodent faunas from this unit werepreviously assigned to the middle Turolian (MN12). In this paper we reconsider the age of the oldestmammal localities from the Guadix Basin, concluding that none of them can be clearly assigned toMN12. Therefore, there is no evidence of the continentalization of the basin before the late Turolian.

Key words: Late Turolian, Late Miocene, Rodents, Micromammals, Guadix Basin.

1. Introduction

The Guadix Basin has one of the most completemammal records of the Iberian Peninsula. Fossili-ferous localities from the Pliocene and Pleistocene arequite abundant and have yielded very rich and diversefaunas (AGUSTÍ 1986; AGUSTÍ et al. 1987; MARTÍN

SUÁREZ 1988; ALBERDI et al. 1989; SESÉ 1989; SESÉ

et al. 2001; RUIZ BUSTOS 2002; ARRIBAS et al. 2004;MINWER-BARAKAT et al. 2004, 2005, 2007, 2008a, b).Nevertheless, Upper Miocene sites are scarce. Con-trary to other South Iberian areas, like Crevillente(MARTÍN SUÁREZ & FREUDENTHAL 1998) and theGranada Basin (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a, b), wherelate Turolian faunas are abundant and well known,

very few Turolian localities have been reported fromthe Guadix Basin. The small mammal faunas fromthe section of Botardo (MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1988), PinoMojón (SESÉ 1989) and Negratín 1 (MINWER-BARAKAT 2005) have been assigned to the late Turo-lian (MN13), as well as the large-mammal locality ofAbla (CUEVAS et al. 1984). The oldest mentionedcontinental fauna from this basin is that of Salinas,with very few rodent remains, and assigned to themiddle Turolian (MN12) by SORIA & RUIZ BUSTOS

(1992). Consequently, the base of the stratigraphicunit IV, the oldest continental unit of the GuadixBasin, has been dated as middle Turolian by manyauthors (FERNÁNDEZ et al. 1996, SORIA et al. 1998,1999; VISERAS et al. 2003, 2006).

eschweizerbartxxx author

96 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

In this paper we study the section of Rambla deChimeneas, a new well-exposed and continuoussection very close to the boundary between marineand continental deposits in the central part of theGuadix Basin. We have prospected several levels,all of them poor in fossil remains. After extensivesampling of one of these levels, Rambla de Chime-neas-3, we dispose of a collection of 26 identifiablemicromammal teeth. The species we have recognizedcan be assigned clearly to the late Turolian (MN13).

Finally, we reconsider the age of the scarce rodentfauna from Salinas, a locality situated very close toRambla de Chimeneas-3, previously assigned to theMN12 (SORIA & RUIZ BUSTOS 1992). Consequently,in this paper we question the age of the continentali-zation of the Guadix Basin.

2. Geological setting and description of thesection of Rambla de Chimeneas

The Betic Cordillera is situated in the south of theIberian Peninsula and, together with the North AfricanRif, represents the western extreme of the belt ofAlpine chains around the Mediterranean. It has twomain structural domains: the Internal Zones (or Albo-ran Block) located to the South, and the ExternalZones to the North, representing the deformed SouthIberian paleomargin (VERA 2001). Neogene-Quater-nary basins, one of which is the Guadix Basin, devel-oped in both these domains, beginning in the late Mio-cene, and trapped the sediments resulting from theerosion of the relief in the Internal and External Zones(VISERAS et al. 2005).

The Guadix Basin, situated in the central sector ofthe Betic Cordillera, was established as a separateintramontane basin in the LateMiocene (VISERAS et al.2004, 2005). The basin’s sedimentary infill has beendivided into six genetic units (FERNÁNDEZ et al. 1996)whose boundary unconformities are related to bothtectonic events and eustatic changes (SORIA et al.1998, 1999). The two lower units (Units I and II) weredeposited in a phase of marine sedimentation duringthe Tortonian, and the third one (Unit III) includessediments deposited during the retreat of the sea fromthe central sector of the Betic Cordillera at the end ofthe Tortonian. The three youngest units (Units IV, Vand VI) cover the late Turolian to the Late Pleistocene,which was a period of exclusively continental sedi-mentation in an endorheic basin context (VISERAS &FERNÁNDEZ 1995). This sedimentary phase was inter-rupted in the Late Pleistocene, when a geomorpho-

logical inversion of the basin took place and it wascaptured in its entirety by the drainage network of theGuadalquivir River, becoming an exorheic domainmainly subjected to erosion (CALVACHE & VISERAS

1997).The section of Rambla de Chimeneas, with a total

thickness of 120 m, is situated in the central part of thebasin, 10 km east of Villanueva de las Torres and 6 kmwest of the Negratín Dam, between coordinates30SVG999578 and 30SVG996580, on the left bank ofthe Guadiana Menor River. On the opposite riverside,close to the base of the section, Late Miocene bio-clastic calcarenites crop out, corresponding to the pre-ceding phase of marine sedimentation. The sectionforms part of the continental deposits of Unit IV, theoldest exclusively continental unit of the infilling ofthe Guadix Basin (VISERAS et al. 2004).

In this section, several kinds of deposits can bedistinguished (Fig. 1):

1. Clast-supported conglomerates with mainlymetamorphic clasts (schist and quartzite) and, in les-ser amounts, dolomite fragments, showing normalgrading. These conglomerates form bodies with ero-sional bases and decimetric to metric thickness. Theyare overlayed by dark sands with abundant schistgranules, in some cases showing planar cross-bed-ding, greenish silts and red clays. These depositscorrespond to the Axial System (FERNÁNDEZ et al.1996), with supplies coming from the Internal Zonesof the Betic Cordillera (mainly from the Nevado-Filábride Complex). The gravel and sand bodies re-present the infilling of fluvial channels, whereas thelutitic levels correspond to floodplain deposits.

2. Heterometric, clast-supported conglomerateswith mostly limestone fragments, up to 15 cm in dia-meter, and with no internal organization. Upwards,these conglomerates change to brown or red sandswith planar cross-bedding. These are relatively pro-ximal alluvial deposits, corresponding to non-co-hesive debris flows, belonging to the External Trans-verse System (FERNÁNDEZ et al. 1996), whose sourcearea lies in the External Zones of the Cordillera.

3. Grey marls, in decimetric to metric thick levels,which are more abundant towards the upper part of thesection. These deposits correspond to the LacustrineSystem (FERNÁNDEZ et al. 1996), and were depositedwhile the valley of the main fluvial system (AxialSystem) was temporarily occupied by small shallowlakes.

eschweizerbartxxx author

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 97

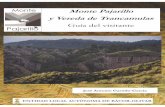

Fig. 1. Stratigraphic column of the Rambla de Chimeneas section, showing the location of the fossiliferous level ofRCH-3.

eschweizerbartxxx author

98 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

The level of Rambla de Chimeneas-3 (RCH-3) islocated at coordinates 30SVG997579; it is a 50 cmthick level of dark marls with relatively abundantremains of gastropods. The faunal list of this fossili-ferous level is the following: Occitanomys alcalai,Stephanomys cf. dubari, Paraethomys meini, Crice-tinae indet., Erinaceidae indet., and Soricidae indet.

3. Dental terminology and measuringmethods

The terminology used in the descriptions of the teeth ofMuridae is that of VAN DE WEERD (1976). Lengths andwidths have been measured as defined by MARTÍN SUÁREZ

& FREUDENTHAL (1993). The nomenclatures employed inthe descriptions of the few teeth of Cricetinae, Erinaceidaeand Soricidae are those of FREUDENTHAL et al. (1994),MEIN & MARTÍN SUÁREZ (1993), and REUMER (1984),respectively.

Specimens are kept in the Departamento de Estratigrafíay Paleontología de la Universidad de Granada, Spain.

4. Systematic paleontology

Family Muridae ILLIGER, 1811Genus Paraethomys PETTER, 1968

Paraethomys meini (MICHAUX, 1969)Fig. 2

Mater ia l : One complete and one incomplete M1, 2 M2,2 incomplete M3, 1 complete and 1 incomplete M1, 2 M2,1 complete and 1 incomplete M3.

Descr ipt ion:M1: The anteroconid is slightly asymmetrical, with thelingual lobe larger and placed in a more anterior positionthan the labial lobe. There is no tma. In the complete spe-cimen, the labial lobe of the anteroconid is connected tothe protoconid, but the lingual lobe is separated from themetaconid, so the enamel islet is lingually open. In thefragmented specimen, the islet is completely closed. Thereis no longitudinal connection between protoconid-meta-conid and hypoconid-entoconid. The labial cingulum isattached to the protoconid. The c1 is very large and connec-ted to the hypoconid. The complete specimen has a smallaccessory labial cuspid between the anteroconid and proto-conid. The posterior heel is low, oval, and connected to theposterolingual part of the hypoconid. There are two roots.

M2: The outline is nearly square. The anterolabial cuspid islarge and round. There is a weak longitudinal spur that doesnot reach the protoconid-metaconid pair. The c1 is large,oval and placed very anteriorly; it is weakly connected to thehypoconid in one specimen, and not connected in the otherone. There is no differentiated labial cingulum, but anenamel protrusion on the labial side of the protoconid. The

Fig. 2. Paraethomys meini: A, RCH-3 2, right M1; B, RCH-3 3, left M2; C, RCH-3 7, left M1; D, RCH-3 9, left M2;E, RCH-3 11, left M3. Scale bar 1 mm.

eschweizerbartxxx author

posterior heel is low, oval, and attached to the hypoconid.There are two roots.

M3: There is no anterolabial cuspid. The protoconid issomewhat larger than the metaconid. The hypoconid-ento-conid complex is slightly shifted towards lingual. There isno c1, nor a longitudinal crest. There are two roots.

M1: The t1 is posterior with respect to t3, and weaklyconnected to t2. There is neither t1bis nor t2bis. There is nolongitudinal connection between t1 and t5. The t3 has asmall posterior spur directed towards t6. There is a smallstyle minuscule tubercle on the posterolabial part of t3, nearthe labial border. The t4 is somewhat posterior with respectto t6, separated from t8 in one specimen and weaklyconnected to t8 in the other one. The t9 is smaller than t6and connected to it. In the complete specimen, due to theadvanced wear, t12 appears like a protuberance on theposterolabial part of t8. There are two large roots, anteriorand lingual, and a smaller posterior one.

M2: The t1 is large, high, oval and isolated. The t3 is muchsmaller and lower than the t1, round, isolated and close tothe t5. The t1 and t3 have no posterior spurs. The t4 is some-what posterior with respect to t6 and connected to t8. The t8is very large and slightly shifted towards the labial side. Thet9 is reduced to a crest connecting t6 and t8. There is no t12.There are two small roots in anterolabial and posterolabialpositions and a large bilobated lingual root.

M3: The t1 is very large, oval and protruding over theanterior and lingual borders. It is separated from t4 by avery deep valley, and only connects to t5 in a very advancedstage of wear. There is no t3. The t4, t5, t6 and t8 areconnected forming a ring with a central deep funnel, com-pletely closed by the t4-t8 connection. The t5 and t6 arehardly individualized. The t8 is small, round and centrallyplaced. There are three roots, in anterolingual, anterolabialand posterior positions.

Measurements: See Table 1.

Discussion: The measurements of the few teeth fromRCH-3 are very similar to those of the type population ofParaethomys meini, Sète, which has yielded few specimenstoo (MICHAUX 1969; ADROVER 1986). The size of thematerial from RCH-3 is also similar to that from Negratín-1(MINWER-BARAKAT 2005). In general, P. meini from thesections of Purcal and Calicasas in the Granada Basin issimilar in size to the population from RCH-3, whereas thespecimens from the section of La Dehesa are slightly smal-ler (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a).

The size is similar to that of other populations of thesame species from the Teruel region like Orrios (VAN DE

WEERD 1976), Aldehuela, Arquillo III, Villalba Alta, OrriosIII (ADROVER 1986), Villalba Alta Río and Peralejos E(ADROVER et al. 1988); the only difference is the width ofthe M2, which is somewhat larger in the specimens fromRCH-3. The teeth from RCH-3 are somewhat larger thanthose from La Juliana (MONTENAT & DE BRUIJN 1976) and

smaller than those from Botardo 2 and C and Gorafe 4(MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1988).

The morphology of the material from RCH-3 is verysimilar to that of the specimens of the type population. Themost characteristic feature is the lack of t9 in M2; however,the reduction or complete absence of the t9 is a commoncharacter in all species of Paraethomys. Other featuresshared by the material from RCH-3 and that from Sète are:the weak labial cingulum in the lower molars, the absence oftma in the M1 and the lack of well-developed posterior spursin the t1 and t3 of the M1. The M1 from RCH-3 have anenamel islet originated by the union of the lingual andlabial lobes of the anteroconid with the metaconid andprotoconid, respectively, a feature also observed in otherpopulations of P. meini like Gorafe 4 (MARTÍN SUÁREZ

1988). However, this character is not present in all thepopulations of the species; in fact, the specimens of the typepopulation lack this enamel islet.

No significant differences have been found between thematerial from Maritsa (type population of Paraethomysanomalus, see DE BRUIJN et al. 1970), that from Khen-dek-el-Ouaich (type population of Paraethomys miocaeni-cus, JAEGER et al. 1975) and that of several populationsassigned to P. meini. Therefore, we accept the synonymybetween these three species proposed by MONTENAT & DE

BRUIJN (1976) and VAN DE WEERD (1976), and acceptedlater by many other authors (ADROVER 1986; MARTÍN

SUÁREZ 1988; CASTILLO 1990; FREUDENTHAL & MARTÍN

SUÁREZ 1999).We have compared the material from RCH-3 with

several populations of P. meini kept in the University ofLyon I: Amama 2, Arquillo 4 and Tolosa (previouslyassigned to P. miocaenicus), Maritsa, Peralejos E, Caravaca,Brisighella and Amama 3 (previously ascribed to P. ano-malus), Layna, VillalbaAlta, VillalbaAlta Río 2, Serrat d’enVacquer andVilleneuve de la Raho (originally assigned to P.meini). We have observed no significant differences in sizebetween these populations. Regarding morphology, noimportant differences can be observed in the lower molars,M1 and M3. The development of the t9 in the M2 is variablewithin some populations. In Amama 2 (ascribed to P. mio-caenicus), Amama 3, Peralejos E, Brisighella (assigned to P.anomalus) and Layna (P. meini) some specimens have anindividualized t9. In most specimens from these localities,

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 99

Table 1. Measurements (in mm) of the teeth of Paraethomysmeini (MICHAUX, 1969) from Rambla de Chimeneas-3.

Specimen Dental element Length Width

RCH-3 2 M1 2.04 1.32RCH-3 3 M2 1.48 1.47RCH-3 4 M2 1.46 1.46RCH-3 6 M3 1.19RCH-3 7 M1 2.37 1.57RCH-3 9 M2 1.61 1.63RCH-3 10 M2 1.57 1.63RCH-3 11 M3 1.12 1.16

eschweizerbartxxx author

100 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

and in all the teeth from the rest of sites we have comparedwith, a t9 is absent, like in the populations from Sète (typelocality of P. meini, MICHAUX 1969) and RCH-3. Thethickness of the crest connecting t6 and t8 is variable in allthe mentioned populations. Some M2 of the very numerouspopulation from Purcal 4 (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a) alsohave a small t9. We conclude that the development of t9 inthe M2 shows a certain intraspecific variability.

The specimens from RCH-3 are smaller than those ofParaethomys belmezensis from Bélmez-1 (CASTILLO 1992).Morphologically, the studied material differs from P. bel-mezensis in the absence of tma in M1 and in the crestconnecting t6 and t8 in M2, which is lower in P. belmezensis.Paraethomys abaigari from Villalba Alta Río (ADROVER etal. 1988) and P. aff. abaigari from Purcal 13 and Calicasas-5A (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a) are clearly larger than thematerial from RCH-3, and have more developed posteriorspurs in the t1 and t3 of M1. Paraethomys jaegeri fromGorafe-2 (type population, MONTENAT & DE BRUIJN 1976),Gorafe-3 and 5 (MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1988), Asta Regia-3(CASTILLO & AGUSTÍ 1996) and Mont-Hélène (AGUILAR etal. 1986) is notably larger than P. meini from RCH-3; thesespecies can be distinguished mainly by the great differencein size.

The Pleistocene species from North Africa, P. rbiae, P.darelbeidae and P. filfilae, clearly differ from P. meini intheir larger size and more developed stephanodonty(RENAUD et al. 1999). The species P. chikeri, found in LatePliocene African localities like Ahl al Oughlam (GERAADS

1995) is also larger than P. meini and has longitudinalconnections in the upper and lower molars.

The genus Paraethomys has a circummediterraneandistribution. The oldest (Late Miocene) and youngest (Plei-stocene) species are found in North Africa. In Europe, thegenus is present since the late Turolian until the final Rus-cinian. The first representative of the genus in the IberianPeninsula is P. meini, whose first occurrence is posteriorto that of Stephanomys ramblensis (MARTÍN SUÁREZ &FREUDENTHAL 1998). During the Pliocene, this genus be-comes more diversified, and larger species occur (P. abai-gari, P. jaegeri, P. belmezensis).

Genus Occitanomys MICHAUX 1969

Occitanomys alcalai ADROVER, MEIN & MOISSENET,1988Fig. 3

Mater ia l : One complete and 1 incomplete M1, 1 comple-te and 1 incomplete M3, 1 M1, 1 M2, 1 M3.

Descr ipt ion:M1: The posterior part is considerably wider than theanterior part. The anteroconid is slightly asymmetrical, withthe lingual lobe somewhat anterior with respect to the labialone. There is no tma. The anteroconid is connected to theprotoconid-metaconid intersection by a crest, which is veryweak in one specimen. There is no longitudinal crest, but avery short longitudinal spur. The c1 is large and connectedto the hypoconid. There is no other accessory labial cuspid.The labial cingulum is continuous and reaches the antero-conid. The posterior heel is much smaller than the c1, lowand elongated. The posterior border is straight. There aretwo roots.

M3: One specimen has a minuscule anterolabial cuspid.The protoconid and metaconid are practically symmetrical.There is no longitudinal crest. The posterior complex issomewhat shifted towards the lingual side. The c1 is absent.There are two roots.

M1: The t1 is placed very posteriorly and widely separatedfrom the t2. There is a small but well-differentiated t1bis.There is no t2 bis. The t3 has a small posterior spur thatdoes not reach the t5. The posterolabial end of t1 is con-nected to the lingual face of t5. The t4 is connected to t8 bya crest. The t6 is larger than t9 and connected to it. There isa small t12 attached to the posterolabial part of t8; it hasalmost disappeared because of wear. In lateral view, the t6 isstrongly inclined backwards. There are three roots.

M2: The t1bis is oval and connected to t1 and t5. A verylow crest connects t1 to t5. The t3 is round and separated

Fig. 3. Occitanomys alcalai: A, RCH-3 13, right M1; B, RCH-3 15, right M3; C, RCH-3 17, left M1; D, RCH-3 18, left M2.Scale bar 1 mm.

eschweizerbartxxx author

from t5. The t4 is weakly connected to t8 and t5. The t6is larger than t9 and connected to it. The t12 cannot beobserved because of wear. There are two small roots, antero-labial and posterolabial, and a larger lingual root.

M3: The t1 is large, well individualized, and connected tot5. The t5 is also connected to t4 and t6 by two crests. Thet6 is connected to t8 and this latter joins t4, closing a centralfunnel. The roots are not preserved.

Measurements: See Table 2.

Discussion: The dimensions of Occitanomys from RCH-3 fit the size ranges of the type population of O. alcalai(Peralejos E), except for the lengths of the M3, M2 and M3

and the width of the M3, that are slightly smaller than in thetype population. The specimens from RCH-3 are smallerthan those from PUR-4 and 13 (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a),with the exception of the M1, which is larger in RCH-3. Thefew teeth of O. alcalai from the Portuguese locality ofEsbarrondadoiro (ANTUNES & MEIN 1995) are similar insize to the specimens from RCH-3. Anyhow, all thementioned localities have yielded very few specimens, sothe differences in size are not conclusive. Practically all themeasurements of the teeth from RCH-3 fit the size ranges ofother more abundant populations of O. alcalai, like thosefrom Valdecebro 3 and 6 and La Gloria 5 (ADROVER et al.1988; 1993).

All the diagnostic characters of the species O. alcalaihave been recognized in the material from RCH-3: rela-tively high crown, well-developed t1bis, absence of isolatedcusps in the upper molars, and lack of complete longitudinalcrests in the lower molars. We have compared the materialfrom RCH-3 with that from the type locality stored in theUniversity of Lyon I. The morphology of the M1 is verysimilar in RCH-3 and in Peralejos E. In the population fromPeralejos E, some M1 have different features than thosefrom RCH-3: better development of the t1bis, presence of at2bis, stronger t3-t5 connection, or absence of the t1- t5 andt4-t8 connections. Nevertheless, other specimens are mor-phologically identical to the M1 from RCH-3. The rest of thedental elements show no differences with the material fromPeralejos E.

We have also compared with the population of O.alcalai from Purcal-4 (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a). Some

M1 from PUR-4 have the longitudinal spur more developedthan the specimens from RCH-3. No differences can beobserved in the rest of dental elements.

The measurements of O. alcalai from RCH-3 are clearlysmaller than those of O. adroveri from Los Mansuetos (typelocality) and other Spanish populations like Masada delValle 3 and 5, Concud 3 (VAN DE WEERD 1976), Aljezar B(ADROVER 1986), Crevillente 7, 8, 15 and 17 (MARTÍN

SUÁREZ & FREUDENTHAL 1993). With respect to the mor-phology, clear differences exist between O. adroveri and thespecimens of O. alcalai from RCH-3. Many M1 and M2 ofO. adroveri have a well developed longitudinal spur, or evena complete longitudinal crest. The M1 of O. adroveri fromAljezar B have an elongated posterior heel with a crest thatreaches the posterolingual part of the entoconid. Contrary,in the specimens from RCH-3 the posterior heel is oval andlacks this crest. The anterolabial cuspid of the M3, present inall the specimens of O. adroveri from its type locality and inmost teeth from Aljezar B, is absent in one out of two M3from RCH-3. The M1 of O. alcalai have a higher crown, abetter-developed stephanodont crest and a less backwardt1 than those of O. adroveri. The t1-t5 connection in M2,which is present in the specimen from RCH-3, is morefrequent in O. alcalai than in O. adroveri.

The specimens from RCH-3 are, with the exceptionof the M1, clearly larger than those of O. debruijni fromMaritsa 1. In addition, the M1 of O. debruijni has a lowerstephanodont crest than that of O. alcalai.

The M1, M3 and M3 from RCH-3 are similar in size tothose of O. benericettii from Brisighella 25 (DE GIULI

1989); the M1 and M2 are larger in RCH-3. The lowermolars of O. benericettii have better-developed longitudinalcrests than those of O. alcalai, and the M2 has four roots,contrary to the specimen from RCH-3, which has threeroots.

The material from RCH-3 is similar in size to O. son-daari from its type locality (Tortajada A) and other sites ofthe Teruel region (VAN DE WEERD 1976; ADROVER 1986),and from Crevillente 2, 4B and 5A (MARTÍN SUÁREZ &FREUDENTHAL 1993), except for the M1, which is larger inRCH-3. With regard to the morphology, O. sondaari can bedistinguished from O. alcalai from RCH-3 by the weak orabsent t6-t9 connection in M1 and M2, the lower t4-t5 crest,the absence or small size of t1bis in the M1, in the widelyseparated t1 and t1bis (or t2), in the less-developed labialcingulum in the lower molars, and in the more frequentlongitudinal spur in the lower molars.

The size of O. alcalai from RCH-3 is much smallerthan that of O. brailloni from its type locality (Layna) andother sites like Nîmes, Sète (MICHAUX 1969), Arquillo 3(ADROVER 1986), Moreda 1-A, and 1-B (CASTILLO 1990),Gorafe-5 (MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1988) and Tollo de Chiclana-1B(MINWER-BARAKAT et al. 2005). In addition, O. braillonican be distinguished fromO.alcalai by the better-developedlongitudinal crests in the upper molars.

Occitanomys alcalai is restricted to Upper Miocene andLower Pliocene localities in the Iberian Peninsula. Insoutheastern Spain, O. alcalai is present in Crevillente 6(MARTÍN SUÁREZ & FREUDENTHAL 1993), in the SorbasBasin (MARTÍN SUÁREZ et al. 2000), the Granada Basin(GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a), and also in the Guadix Basin,

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 101

Table 2. Measurements (in mm) of the teeth of Occitanomysalcalai ADROVER, MEIN & MOISSENET, 1988 from Ramblade Chimeneas-3.

Specimen Dental element Length Width

RCH-3 13 M1 1.61 1.10RCH-3 15 M3 0.93 0.92RCH-3 16 M3 0.91RCH-3 17 M1 1.96 1.35RCH-3 18 M2 1.27 1.31RCH-3 19 M3 0.84 0.89

eschweizerbartxxx author

102 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

in the localities of Botardo-3, B and C, Gorafe-4 (unpublis-hed data) and Negratín-1 (MINWER-BARAKAT 2005). Thisspecies is considered an immigrant in the Iberian Peninsula,because it shows notable differences with the species of thegenus previously present in Spain, belonging to the lineageO. sondaari-O. adroveri (ADROVER et al. 1993; FREUDEN-THAL & MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1999).

Genus Stephanomys SCHAUB, 1938

Stephanomys cf. dubari AGUILAR, MICHAUX,BACHELET, CALVET & FAILLAT, 1991

Fig. 4

Mater ia l : One incomplete M1, 2 M2, 1 M2.

Descr ipt ion:M1: The only fragment corresponds to the posterior part ofa rather worn molar. The entoconid is connected to theintersection between protoconid and metaconid by a highlongitudinal crest. The c1 is oval and connected to theanterolabial part of the hypoconid. The posterior heel is lowand transversally elongated; it is shifted towards the lingualside of the molar and continues in a lingual crest thatreaches the posterolingual part of the entoconid.

M2: The outline is subquadrate. The anterolabial cuspid iscomma-shaped and connected lingually to the protoconid.The longitudinal crest is well developed; it connects theentoconid to the protoconid-metaconid intersection. Thelabial cingulum is attached to the protoconid. In onespecimen, c1 is attached to the labial side of the hypoconid;in the other one, c1 is connected to the hypoconid at itsanterolingual end. There is a minuscule accessory labialcuspid in one specimen. The posterior heel is large and oval.There are two roots.

M2: The single specimen is rather worn. The t1bis is lin-gually connected to t1. The t1 is very large and connected tot5 by crest situated quite lingually. The t3 is comma-shaped,and connects to the t5-t6 intersection by a well-developed

labially situated longitudinal crest. The t4 is placed in a veryposterior position with respect to t6 and connected to t8 bya low crest. The t6 is much larger than t9. A t12 cannot beobserved, but this may be due to the advanced stage of wear.The roots are not preserved.

Measurements: Only 3 specimens have been measured.Their dimensions (length x width) are: Two M2: 1.56 x 1.49mm and 1.59 x 1.51 mm; one M2: 1.65 x 1.68 mm.

Discussion: The measurements of the specimens fromRCH-3 fit the size range of S. dubari from its type locality,Castelnou 3, the mean lengths and widths are very similar inboth samples. The size is also very similar to that ofS. dubari from several localities of the Granada Basin(GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a).

The measurements also fit the size range of the typepopulation of S. ramblensis, Valdecebro 3 (VAN DE WEERD

1976). Nevertheless, the M2 from RCH-3 is notably largerthan the specimens of other populations of S. ramblensisfrom the Teruel region like Masada del Valle 6 and VillalbaBaja 1. Anyhow, biometrical criteria are not sufficient toperform a specific determination of the material fromRCH-3, because the size ranges of the type populations ofS. dubari and S. ramblensis widely overlap. The use of thesize as a diagnostic criterion is especially problematic due tothe scarcity of the material from RCH-3.

We have compared our material with that of the typepopulation S. dubari kept in the University of Lyon, ob-serving a great morphological similitude. The lower molarsfrom RCH-3 have a slightly lower longitudinal crest thanthose from Castelnou 3, although the difference is verysubtle. The single M2 from RCH-3 has, like most specimensfrom Castelnou 3, a crest connecting t3 and t5. In any case,this is a variable character in the type population of thespecies and in others such as Purcal-4 (GARCÍA-ALIX et al.2008a), in which some specimens lack this labial longitudi-nal connection. The single M2 from NGR-1 (MINWER-BARAKAT 2005) does not have a complete crest, but a smallspur on the t5 directed towards the t3.

On the contrary, morphological differences with thetype population of S. ramblensis are evident. The M2 have alarger anterolabial cuspid in Valdecebro 3 than in RCH-3.

Fig. 4. Stephanomys cf. dubari:A, RCH-3 22, left M2;B, RCH-3 23, left M2.Scale bar 1 mm.

eschweizerbartxxx author

The longitudinal crests of the lower molars are notablylower in S. ramblensis from Valdecebro 3 than in NGR-1.The crest connecting t3 and t5 that exists in the M2 fromRCH-3 is a very unusual character in the type population ofS. ramblensis.

We have also compared our material to S. ramblensisfrom Crevillente 14 and 31 (MARTÍN SUÁREZ & FREUDEN-THAL 1993). The M2 from these sites are smaller than thosefrom RCH-3, and have a notably lower longitudinal crest,and a smaller and more elongated posterior heel. The onlyM2 from Crevillente 31 has a weak anterior spur on thet5, directed towards the t3, instead of the complete longi-tudinal crest that is present in the specimen fromRCH-3.

Summarizing, the sample from Rambla de Chimeneas-3is more similar to S. dubari from Castelnou 3 than to S.ramblensis from Valdecebro 3. Some characters are inter-mediate between the two type populations, but the size, theheight of the longitudinal crests and the morphology of theposterior heel and labial cingulum in the lower molars aremuch more similar to those of S. dubari.

The dimensions of the specimens from RCH-3 are simi-lar to the minimum values of S. cordii RUIZ BUSTOS 1986of the type population, Alcoy. We have directly comparedto material from Alcoy, observing that the M2 have atubercular posterior heel and a stronger longitudinal crestthan those from RCH-3. The M2 from Alcoy have better-developed labial and lingual longitudinal connectionsthan those from RCH-3. The crown of all the dentallements is higher in S. cordii than in S. cf. dubari fromRCH-3.

The specimens from RCH-3 are similar in size to thoseof S. stadii from Cucuron (MEIN & MICHAUX 1979). Withrespect to the morphology, S. stadii has lower longitudinalcrests in lower and upper molars, a less-developed lingualcingulum in the M1 and M2, and a less-accentuated asym-metry between the labial and lingual cuspids than S. cf.dubari from RCH-3.

The size of S. cf. dubari from RCH-3 is slightly smallerthan that of S. minor. The main morphological differencesbetween these species are the crest-shaped posterior heel inthe M1 and M2, and the higher longitudinal crests in S.minor. The rest of the Pliocene species of Stephanomys(S. margaritae, S. donnezani, S. thaleri, S. vandeweerdi, S.calveti, S. balcellsi) are notably larger than S. dubari, andhave clearly higher longitudinal crests in lower and uppermolars.

Stephanomys dubari has been reported from severallocalities of the Ibero-Occitan province. AGUILAR et al.(1991) assigned several populations to S. dubari that werepreviously attributed to other species, like those from Cara-vaca (DE BRUIJN 1974), La Tour (AGUILAR et al. 1982) andLa Alberca (MEIN et al. 1973). Later on, this species hasbeen recognized in Southern Spain in Zorreras 3A (MARTÍN

SUÁREZ et al. 2000), in various localities in the GranadaBasin (GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a), and in the locality ofNegratín-1 in the Guadix Basin (MINWER-BARAKAT 2005).Probably, other populations from the uppermost Turolianpreviously attributed to S. ramblensis might also correspondto S. dubari.

Family Cricetidae FISCHER DE WALDHEIM, 1817Subfamily Cricetinae FISCHER DE WALDHEIM, 1817

Cricetinae gen. et sp. indet.

Mater ia l : One M1.

Descript ion and discussion: The enamel of the singleM1 found from RCH-3 is very damaged, so the tooth cannotbe measured (the approximate length of the specimen is1.95 mm, but the real length would be considerably larger,since the enamel and dentine are partially lost). The distri-bution of crests and cusps cannot be observed clearly.Therefore, it is impossible to determine this tooth.

This specimen is similar in size to Apocricetus alberti,and considerably smaller than A. barrierei, as evidencedafter direct comparison with material of these species. It isquite probable that the tooth from RCH-3 belongs to A.alberti, a species recognized in several nearby localities ofthe same age (Negratín, MINWER-BARAKAT 2005; Purcal 3,23, 24 and 25, GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008c). Anyhow, giventhe scarcity and poor preservation of the material, we prefernot to make any specific or even generic ascription.

Family Erinaceidae FISCHER DE WALDHEIM, 1817

Erinaceidae gen. et sp. indet.

Mater ia l : One I2.

Descr ipt ion: The single I2 is a compressed tooth, with aslightly convex labial side and a concave lingual side. Theposterior border is straight and sharp; this border curvestowards the lingual side near the base of the crown, andthickens forming a small bulge. The tooth has a singleroot.

Discussion: The scarcity of the material does not allow aspecific or even generic determination of the single toothfrom RCH-3. Nevertheless, the studied specimen is verysimilar in size and morphology to those of Parasorexibericus from Otura-1 (type population, MEIN & MARTÍN

SUÁREZ 1993), Purcal-4 and 13 (unpublished data) andNegratín-1 (a site close to RCH-3, equivalent in age andwith a very similar faunal list, MINWER-BARAKAT 2005).Parasorex ibericus has been found in numerous localitiesin the Iberian Peninsula, ranging in age from the finalVallesian to the Early Pliocene. In the Guadix Basin, thisspecies has been recorded in Cortijo de la Piedra (MEIN &MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1993), Botardo 3 and C (unpublisheddata), and the above mentioned locality of Negratín-1. Othersites have yielded material of Erinaceidae that has notbeen determined due to their scarcity (Bacochas-1, Rambladel Conejo-3, Barranco de Quebradas-1, SESÉ 1989;Colorado 2, GUERRA MERCHÁN et al. 1991; Yeguas, SORIA

& RUIZ BUSTOS 1991); as in the case of the specimen fromRCH-3, some of these remains probably correspond toP. ibericus.

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 103

eschweizerbartxxx author

104 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

Family Soricidae FISCHER DE WALDHEIM, 1817

Soricidae gen. et sp. indet.

Descr ipt ion: Only one fragment of a M2 has been found,which corresponds to the labial part of the molar. The meta-cone is higher than the paracone. There is a well-markedcingulum bordering the posterior face. Although the lingualpart of the tooth is missing, one can observe that the widthis notably larger than the length.

Discussion: The scarcity of the material does not allow adetermination, even at the generic level. The size and theobserved morphological features are very similar to those ofthe few specimens of Soricidae indet. from Negratín-1, anearby locality of the same age (MINWER-BARAKAT 2005).It is quite probable that the material from both localitiescorresponds to the same form.

5. Age of the fauna of Rambla deChimeneas-3

The murids Paraethomys meini, Occitanomys alcalaiand Stephanomys dubari are very typical elements ofthe upper Turolian Spanish faunas. The first occur-rence of the three species is documented in the lateTurolian (MN13). More exactly, the entrance of Para-ethomys meini into the Iberian Peninsula is dated inthe final part of the late Turolian, approximately at 6.2my (GARCÉS et al. 1998; VAN DAM et al. 2001; AGUSTÍ

et al. 2006).As argued in previous paragraphs, the size and

morphology of S. cf. dubari from RCH-3 suggest thatthis site is somewhat older than the type locality of thespecies, Castelnou-3, from the Turolian-Ruscinianboundary. This fact also indicates a late Turolian agefor the site of RCH-3. With all these data, the faunafrom the locality of Rambla de Chimeneas-3 can beclearly assigned to the upper Turolian (MN13).

The fauna of RCH-3 is very similar to that ofNegratín-1 (MINWER-BARAKAT 2005), a nearby upperTurolian locality from the Guadix Basin. In fact, allthe species identified in RCH-3 are also present inNegratín-1 and show very similar morphological andbiometrical characters. The locality of Pino Mojón hasalso been assigned to MN13 (SESÉ 1989); we agreewith this ascription, although the specific determina-tion of some taxa from that site must be reconsideredtaking into account more recent findings (for ex-ample, Stephanomys ramblensis and Occitanomys cf.adroveri should be compared with S. dubari and O.alcalai respectively). The sites of Botardo A, B, C, 2and 3, considered to be close to the Miocene-Plioceneboundary (MARTÍN SUÁREZ 1988), are somewhat

younger than RCH-3; some species that will persistin the basin during the Pliocene are already presentin Botardo (Castillomys gracilis, Apodemus gora-fensis).

Fossiliferous localities from the upper Turolian arenumerous in different areas of the Iberian Peninsula:the Granada (PADIAL 1986; GARCÍA-ALIX et al. 2008a,b) and Fortuna basins (GARCÉS et al. 1998), the area ofCrevillente (MARTÍN SUÁREZ & FREUDENTHAL 1998)and the Teruel region (MEIN et al. 1990; VAN DAM etal. 2001). In these areas, with a very complete micro-mammal record, several typical late Turolian species(Apodemus gudrunae, Occitanomys alcalai, S. ram-blensis) appear clearly earlier than the genus Para-ethomys. Thus, the locality of RCH-3 is younger thanthose late Turolian sites in which Paraethomys is notyet present, like Canteras de Jun, Pulianas 1, 2 and 3,Crevillente 14, 22 and 31, La Gloria 6, Masada delValle 7, Valdecebro 3 and 6, Arquillo 1 and Villastar.The localities of La Dehesa, Arquillo 4, Celadas 2,Crevillente 6, Librilla, Venta del Moro and La Al-berca, where P. meini is present, are equivalent in ageto RCH-3. The sites of Zorreras 2B and 3A in theSorbas Basin (MARTÍN SUÁREZ et al. 2000), with O.alcalai, P. meini, S. dubari and Debruijnimys almena-rensis, are also equivalent in age to RCH-3.

The species identified in RCH-3 are uncommonoutside the Iberian Peninsula. The lack of commonspecies allows only an approximate correlation withlate Turolian localities like Lissieu (France), Cassino,Baccinello V2 (Italy) and Polgardi 2 and 4 (Hun-gary). The latest Miocene faunas from Castelnou 3(AGUILAR et al. 1991) and Brisighella (DE GIULI 1989)include some of the taxa present in RCH-3 togetherwith other typical Pliocene species; therefore, weinterpret that they are somewhat younger thanRCH-3.

6. Considerations on the age of the oldestcontinental faunas from the Guadix Basin

The age of the base of the Unit IV has been situated inthe middle Turolian (MN12) in different papers(FERNÁNDEZ et al. 1996; SORIA et al. 1998, 2003;VISERAS et al. 2003). This interpretation is based on asingle locality in the Guadix Basin assigned to theMN12, Salinas, in which SORIA & RUIZ BUSTOS

(1992) identified the species Ruscinomys schaubi andOccitanomys adroveri. Nevertheless, the assignationof this locality to the middle Turolian must be recon-sidered. First, according to RUIZ BUSTOS (1992, 1995,

eschweizerbartxxx author

2002), R. schaubi and O. adroveri are present in theIberian Peninsula from the final middle Turolian to thelate Turolian (MN12 and 13); in fact, both species arefound in the reference locality for MN13, Arquillo 1.Therefore, the presence of these species does notallow assigning the locality of Salinas either to MN12or to MN13. Secondly, SORIA & RUIZ BUSTOS (1992)indicated that the single specimen of O. adroveri fromSalinas (a M1) is smaller than the mean values of O.adroveri from Los Mansuetos (type locality) andMasada del Valle 5, has slender cusps and shows aconnection between t1 and t5. According to thisdescription, it is very probable that this specimencorresponds to O. alcalai, a smaller species than O.adroveri, with thinner cusps and better-developedlongitudinal connections in the upper molars, whichoccurs in the late Turolian (MN13). In RCH-3, veryclose to Salinas, we have recognized O. alcalai, withfeatures very similar to the single tooth describedfrom Salinas, together with Paraethomys meini, aspecies that reaches the Iberian Peninsula during thelate Turolian. These data suggest that the locality ofSalinas probably corresponds to the MN13. Anyhow,the material from this locality consists only of thesetwo teeth, whose specific determination is difficult, soit is practically impossible to know its age precisely.Therefore, in agreement with the current data, theoldest mammal localities from the Guadix Basin witha well-established age (Rambla de Chimeneas-3,Negratín-1, Pino Mojón and Abla) correspond to thelate Turolian, and so the base of the unit IV must bedated to the same age. The lack of knowledge ofany older fossil mammal level does not exclude thepossibility of continental sedimentation previous tothe late Turolian. Nevertheless, given the present stateof knowledge there is no evidence supporting that thecontinentalization of the basin took place prior to thelate Turolian.

7. Conclusions

The locality of Rambla de Chimeneas-3 has yieldedremains of Paraethomys meini, Occitanomys alcalai,Stephanomys cf. dubari, Cricetinae indet., Erina-ceidae indet. and Soricidae indet. Although small, thissample is by far the most complete found in this area,and allows a clear assignation to the late Turolian(MN13).

The only citation of an older continental fauna inthe Guadix Basin is that from Salinas, situated bySORIA & RUIZ BUSTOS (1992) in the middle Turolian

(MN12). In our opinion, the specific ascription givenby these authors for the scarce material from that site(only two teeth) is doubtful. Moreover, the two speciescited by SORIA & RUIZ BUSTOS are not restricted toMN12, but also found in MN13. For these reasons, wequestion the age of the site of Salinas, concluding thatthe oldest continental faunas from the Guadix Basinwith a reliable dating are those from de Rambla deChimeneas-3, Negratín-1 and Pino Mojón. Therefore,there is no faunal evidence of the continentalization ofthe basin before the late Turolian.

Acknowledgements

We thank P. MEIN, who put the material stored in the Uni-versity of Lyon I at our disposal. The photographs weremade by I. SÁNCHEZ-ALMAZO, using the Fei Quanta 400Scanning Electron Microscope of the “Centro Andaluz deMedio Ambiente”, Granada. Careful reviews by P. MEIN

and I. CASANOVAS-VILAR greatly improved the manuscript.This study was supported by the group “Paleogeografíade Cuencas Sedimentarias” (RNM190) of the Junta deAndalucía, the project Programa Consolider-Ingenio 2010(CSD2006-00041), and the Researching Hominid OriginsInitiative (RHOI-HOMINID-NSF-BCS-0321893).

References

ADROVER, R. (1986): Nuevas faunas de roedores en el Mio-Plioceno continental de la región de Teruel (España).Interés Bioestratigráfico y Paleoecológico. – 423 pp.;Teruel (Instituto de Estudios Turolenses).

ADROVER, R., MEIN, P. & MOISSENET, E. (1988): Contri-bución al conocimiento de la fauna de roedores delPlioceno de la región de Teruel. – Teruel, 79: 91-151.

– (1993): Roedores de la transición Mio-Pliocena de laregión de Teruel. – Paleontología i Evolució, 26-27:47-84.

AGUILAR, J. P., CALVET, M. & MICHAUX, J. (1986): De-scription des rongeurs pliocènes de la faune du Mont-Hélène (Pyrénées-orientales, France), nouveau jalonentre les faunes de Perpignan (Serrat-d'en-Vacquer) et deSète. – Paleovertebrata, 16 (3): 127-144.

AGUILAR, J. P., DUBAR, M. & MICHAUX, J. (1982): Noveauxgisements à Rongeurs dans la formation de Valensole:La Tour près de Brunet, d’âge miocène supérieur(Messinien) et Le Pigeonnier de l’Ange près de Ville-neuve, d’âge pliocène moyen. Implications stratigraphi-ques. – Comptes rendus de l’Académie des SciencesParis, 295: 745-450.

AGUILAR, J. P., MICHAUX, J., BACHELET, B., CALVET, M. &FAILLAT, J. P. (1991): Les nouvelles faunes de rongeursproches de la limite Mio-Pliocène en Rousillon. Impli-cations biostratigraphiques et biogéographiques. –Palaeovertebrata, 20 (4): 147-174.

AGUSTÍ, J. (1986): Synthèse biostratigraphique du Plio-Pléi-stocène de Guadix-Baza (Province de Granada, sud-estde l’Espagne). – Géobios, 19 (4): 505-510.

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 105

eschweizerbartxxx author

106 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

AGUSTÍ, J., GARCÉS, M. & KRIJGSMAN, W. (2006): Evidencefor African-Iberian exchanges during the Messinian inthe Spanish mammalian record. – Palaeogeography,Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 238: 5-14.

AGUSTÍ, J., MOYÁ-SOLÀ, S., MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E. & MARÍN,M. (1987): Faunas de mamíferos en el Pleistoceno in-ferior de la región de Orce (Granada, España). – Paleon-tologia i Evolució, Memoria Especial, 1: 73-86.

ALBERDI, M. T., ALCALÁ, L., AZANZA, B., CERDENO, E.,MAZO, A. V., MORALES, J. & SESÉ, C. (1989): Consider-aciones bioestratigráficas sobre la fauna de vertebradosfósiles de la cuenca de Guadix-Baza (Granada, España).– Trabajos sobre el Neógeno-Cuaternario, 11: 347-355.

ANTUNES, M. T. & MEIN, P. (1995): Nouvelles données surles petits mammifères du Miocène terminal du bassin deAlvalade, Portugal. – Comunicaçoes Instituto Geologicoe Mineiro, 81: 85-96.

ARRIBAS, A., BAEZA, E., BERMÚDEZ, D., BLANCO, S.,DURÁN, J. J., GARRIDO, G., GUMIEL, J. C., HERNÁNDEZ,R., SORIA, J. M. & VISERAS, C. (2004): Nuevos registrospaleontológicos de grandes mamíferos en la Cuenca deGuadix-Baza (Granada): Aportaciones del ProyectoFonelas al conocimiento sobre las faunas continentalesdel Plioceno-Pleistoceno europeo. – Boletín Geológico yMinero, 115 (3): 567-581.

BRUIJN, H. DE (1974): The Ruscinian rodent succession inSouthern Spain and its implications for the biostratigra-phic correlation of Europe and North Africa. – Sencken-bergiana Lethaea, 55 (1-5): 435-443.

BRUIJN, H. DE, DAWSON, M. R. & MEIN, P. (1970): UpperPliocene Rodentia, Lagomorpha and Insectivora (Mam-malia) from the Isle of Rhodes (Greece). I, II & III. –Proceedings Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie vanWetenschappen, (B), 73: 536-584.

CALVACHE, M. L. & VISERAS, C. (1997): Long-term controlmechanisms of stream piracy processes in southeastSpain. – Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 22:93-105.

CASTILLO, C. (1990): Paleocomunidades de micromamí-feros de yacimientos kársticos del Neógeno Superior deAndalucía Oriental. – 268 pp.; unpublished PhD thesis(University of Granada).

– (1992): Paraethomys belmezensis nov. sp. (Rodentia,Mammalia) du Pliocène de Córdoba (Espagne). – Géo-bios, 25 (6): 775-780.

CASTILLO, C. & AGUSTÍ, J. (1996): Early Pliocene rodents(Mammalia) fromAsta Regia (Jerez basin, SouthwesternSpain). – Proceedings Koninklijke Nederlandse Aka-demie van Wetenschappen, 99 (1-2): 25-43.

CUEVAS, F., MARTÍN PENELA, A., RODRÍGUEZ FERNÁNDEZ,J., SANZ DE GALDEANO, C. & VERA, J. A. (1984): Pre-mière datation du Turolien à la base de la Formation deGuadix (Secteur d’Abla, Almería, Espagne). – Géobios,17 (3): 355-361.

DAM, J. A. VAN, ALCALÁ, L., ALONSO ZARZA, A., CALVO, J.P., GARCÉS, M. & KRIJGSMAN, W. (2001): The UpperMiocene mammal record from the Teruel-Alfambraregion (Spain). The MN system and continental stage/age concepts discussed. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleon-tology, 21 (2): 367-385.

FERNÁNDEZ, J., SORIA, J. M. & VISERAS, C. (1996): Strati-graphic architecture of the Neogene basins in the centralsector of the Betic Cordillera (Spain): tectonic controland base-level changes. – In: FRIEND, P. F. & DABRIO, C.J. (Eds.): Tertiary basins of Spain: The StratigraphicRecord of Crustal Kinematics, 353-365; Cambridge(Cambridge University Press).

FISCHER DE WALDHEIM, G. (1817): Adversaria zoologica. –Mémoires de la Société Impériale des NaturalistesMoscou, 5: 357-472.

FREUDENTHAL, M., HUGUENEY, M. & MOISSENET, E.(1994): The genus Pseudocricetodon (Cricetidae, Mam-malia) in the Upper Oligocene of the province of Teruel(Spain). – Scripta Geologica, 104: 57-114.

FREUDENTHAL, M. & MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E. (1999): FamilyMuridae. – In: RÖSSNER, G. E. & HEISSIG, K. (Eds.): TheMiocene Land Mammals of Europe, 401-409; München(Pfeil).

GARCÉS, M., KRIJGSMAN, W. & AGUSTÍ, J. (1998): Chrono-logy of the late Turolian deposits of the Fortuna basin(SE Spain): implications for the Messinian evolutionof the eastern Betics. – Earth and Planetary ScienceLetters, 163: 69-81.

GARCÍA-ALIX, A., MINWER-BARAKAT, R., MARTÍN SUÁREZ,E. & FREUDENTHAL, M. (2008a): Muridae (Rodentia,Mammalia) from the Mio-Pliocene boundary in theGranada Basin (southern Spain). Biostratigraphic andphylogenetic implications. – Neues Jahrbuch für Geo-logie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 248: 183-215.

– (2008c): Cricetidae and Gliridae (Rodentia, Mammalia)from the Miocene and Pliocene of Southern Spain. –Scripta Geologica, 136: 1-37.

GARCÍA-ALIX, A., MINWER-BARAKAT, R., MARTÍN, J. M.,MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E. & FREUDENTHAL, M. (2008b): Bio-stratigraphy and sedimentary evolution of late Mioceneand Pliocene continental deposits of the Granada basin(southern Spain). – Lethaia: 41 (4): 431-446.

GERAADS, D. (1995): Rongeurs et insectivores (Mammalia)du Pliocène final de Ahl Al Oughlam (Casablanca,Maroc). – Géobios, 28 (1): 99-115.

GIULI, C. DE (1989): The rodents of the Brisighella latestMiocene fauna. – Bollettino della Società Paleonto-logica Italiana, 28 (2-3): 197-212.

GUERRA MERCHÁN, A., RUIZ BUSTOS, A. & MARTÍN-PENELA, A. J. (1991): Geología y fauna de los yacimien-tos de Colorado 1, Colorado 2, Aljibe 2 y Aljibe 3.(Cuenca de Guadix-Baza, Cordilleras Béticas). – Geoga-ceta, 9: 99-102.

ILLIGER, C. (1811): Prodromus systematis mammalium etavium additis terminis zoographicis utriusque classis. –301 pp.; Berlin (Salfeld).

JAEGER, J. J., MICHAUX, J. & THALER, L. (1975): Présenced’un rongeur muridé nouveau, Paraethomys miocaeni-cus nov. sp., dans le Turolien supérieur du Maroc etd’Espagne. Implications paléogéographiques. – Comp-tes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences Paris, D, 280:1673-1676.

MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E. (1988): Sucesiones de micromamíferosen la Depresión de Guadix-Baza (Granada, España). –241 pp.; unpublished PhD thesis (University ofGranada).

eschweizerbartxxx author

MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E. & FREUDENTHAL, M. (1993): Muridae(Rodentia) from the lower Turolian of Crevillente (Ali-cante, Spain). – Scripta Geologica, 103: 65-118.

– (1998): Biostratigraphy of the continental upper Mio-cene of Crevillente (Alicante, SE Spain). – Géobios, 31(6): 839-847.

MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E., FREUDENTHAL, M., KRIJGSMAN, W. &RUTGER FORTUIN, A. (2000): On the age of the continen-tal deposits of the Zorreras Member (Sorbas Basin, SESpain). – Géobios, 33 (4): 505-512.

MEIN, P., BIZON, G., BIZON, J.-J. & MONTENAT, C. (1973):Le gisement de mammifères de La Alberca (Murcia,Espagne méridionale). Corrélations avec les formationsmarines du Miocène terminal. – Comptes rendus del’Académie des Sciences Paris, (D), 276: 3077-3080.

MEIN, P. & MARTÍN SUÁREZ, E. (1993): Galerix iberica sp.nov. (Erinaceidae, Insectivora, Mammalia) from the lateMiocene and Early pliocene of the Iberian Peninsula. –Géobios, 26 (6): 723-730.

MEIN, P. & MICHAUX, J. (1979): Une faune de petits mam-mifères d’âge Turolien Moyen (Miocène Supérieur) áCucuron (Vaucluse): données nouvelles sur le genreStephanomys (Rodentia) et conséquences stratigraphi-ques. – Géobios, 12 (3): 481-485.

MEIN, P., MOISSENET, E. & ADROVER, R. (1990): Biostra-tigraphie du Néogène Supérieur du bassin de Teruel. –Paleontologia i Evolució, 23: 121-139.

MICHAUX, J. (1969): Muridae (Rodentia) du Pliocènesupérieur d’Espagne et du Midi de la France. – Palaeo-vertebrata, 3: 1-25.

MINWER-BARAKAT, R. (2005): Roedores e insectívoros delTuroliense superior y el Plioceno del sector central de lacuenca de Guadix. – 548 pp.; unpublished PhD thesis(University of Granada).

MINWER-BARAKAT, R., GARCÍA-ALIX, A., MARTÍN SUÁREZ,E. & FREUDENTHAL, M. (2004): Arvicolidae (Rodentia)from the Pliocene of Tollo de Chiclana (Granada, SESpain). – Géobios, 37: 619-629.

– (2005): Muridae (Rodentia) from the Pliocene of Tollode Chiclana (Granada, SE Spain). – Journal of Verte-brate Paleontology, 25 (2): 426-441.

– (2007): Blarinoides aliciae sp. nov., a new Soricidae(Mammalia, Lipotyphla) from the Pliocene of Spain. –Comptes Rendus Palevol, 6: 281-289.

– (2008b): Micromys caesaris, a new murid (Rodentia,Mammalia) from the late Pliocene of the Guadix Basin,Southeastern Spain. – Journal of Paleontology, 82 (2):436-441.

MINWER-BARAKAT, R., GARCÍA-ALIX, A. & FREUDENTHAL,M. (2008a): Desmaninae (Talpidae, Mammalia) fromthe Pliocene of Tollo de Chiclana (Guadix Basin,Southern Spain). Considerations on the phylogeny ofthe genus Archaeodesmana. – Géobios, 41 (3): 381-398.

MONTENAT, C. & BRUIJN, H. DE (1976): The Ruscinianrodent faunule from La Juliana (Murcia); its implicationfor the correlation of continental and marine biozones. –Proceedings Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie vanWetenschappen, (B), 79 (4): 245-255.

PADIAL, J. (1986): Estudios de los Roedores y Lagomorfosdel Mioceno continental de la Depresión de Granada. –308 pp.; unpublished PhD thesis (University of Gra-nada).

PETTER, F. (1968): Un muridé Quaternaire nouveau d’Al-gérie, Paraethomys filfilae. Ses rapports avec les Muri-dés actuels. – Mammalia, 32: 54-59.

RENAUD, S., BENAMMI, M. & JAEGER, J. J. (1999): Morpho-logical evolution of the murine rodent Paraethomys inresponse to climatic variations (Mio-Pleistocene ofNorth Africa). – Paleobiology, 25 (3): 369-382.

REUMER, J. W. F. (1984): Ruscinian and early PleistoceneSoricidae (Insectivora, Mammalia) from Tegelen (TheNetherlands) and Hungary. – Scripta Geologica, 73:1-173.

RUIZ BUSTOS, A. (1986): Análisis del proceso evolutivo delgénero Stephanomys (Rodentia, Muridae). – Paleomam-malia, 1: 1-22.

– (1992): Biostratigrafía del Neógeno en las CuencasBéticas. Significado geológico regional de las agrupa-ciones de yacimientos. – Actas del III Congreso Geo-lógico de España y VIII Congreso Latinoamericano deGeología, Salamanca, 1: 549-553.

– (1995): Biostratigraphy of the Continental Deposits inthe Granada, Guadix and Baza Basins (Betic Cordillera).– In: GIBERT, J., SÁNCHEZ, F., GIBERT, L. & RIBOT, F.(Eds.): The hominids and their environment during theLower and Middle Pleistocene of Eurasia, 153-174;Orce (Proceedings of the International Conference ofHuman Paleontology).

– (2002): Características Climáticas y Estratigráficas delos Sedimentos Continentales de la Cordillera BéticaDurante el Plioceno, a partir de las Faunas de Mamí-feros. – Pliocénica, 2: 44-64.

SCHAUB, S. (1938): Tertiäre und quartäre Murinae. –Abhandlungen der Schweizerischen PaläontologischenGesellschaft, 61: 1-38.

SESÉ, C. (1989): Micromamíferos del Mioceno, Plioceno yPleistoceno de la cuenca de Guadix-Baza (Granada). –Trabajos sobre el Neógeno-Cuaternario, 11: 185-214.

SESÉ, C., ALBERDI, M. T., MAZO, A. & MORALES, J. (2001):Mamíferos del Mioceno, Plioceno y Pleistoceno de laCuenca Guadix-Baza (Granada, España): revisión de lasasociaciones faunísticas más características. – Paleonto-logia i Evolució, 32-33: 31-36.

SORIA, J. M., FERNÁNDEZ, J., GARCÍA, F. & VISERAS, C.(2003): Correlative lowstand deltaic and shelf systems inthe Guadix Basin (Late Miocene, Betic Cordillera,Spain): The stratigraphic record of forced and normalregressions. – Journal of Sedimentary Research, 73 (6):912-925.

SORIA, J. M., FERNÁNDEZ, J. & VISERAS, C. (1999): LateMiocene stratigraphy and paleogeographic evolution ofthe intramontane Guadix Basin (Central Betic Cor-dillera, Spain): implications for an Atlantic-Mediterra-nean connection. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology,Palaeoecology, 151: 255-266.

SORIA, J. M. & RUIZ BUSTOS, A. (1991): Bioestratigrafía delos sedimentos continentales del sector septentrional dela Cuenca de Guadix, Cordilleras Béticas. – Geogaceta,9: 94-96.

Late Turolian micromammals from Rambla de Chimeneas-3 107

eschweizerbartxxx author

108 R. Minwer-Barakat et al.

SORIA, J. M. & RUIZ BUSTOS, A. (1992): Nuevos datos sob-re la edad del inicio de la sedimentación continental enla Cuenca de Guadix. Cordillera Bética. – Geogaceta,11: 92-94.

SORIA, J. M., VISERAS, C. & FERNÁNDEZ, J. (1998): LateMiocene-Pleistocene tectono-sedimentary evolution andsubsidence history of the central Betic Cordillera(Spain): a case study in the Guadix intramontane basin.– Geological Magazine, 135 (4): 565-574.

VERA, J. A. (2001): Evolution of the South Iberian Con-tinental Margin. – Mémoires du Muséum Nationald’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 186: 109-143.

VISERAS, C. & FERNÁNDEZ, J. (1995): The role of erosionand deposition in the construction of alluvial fan se-quences in the Guadix Formation (SE Spain). – Geologieen Mijnbouw, 74: 21-33.

VISERAS, C., FERNÁNDEZ, J., SORIA, J. M. & CALVACHE, M.L. (2003): Models for Late Miocene-Modern alluvialfan development, Granada and Guadix Basins (CentralBetic Cordillera). Field Trips-Post Conference. – 33 pp.;Sorbas, Spain (International Alluvial Fans conference2003).

VISERAS, C., SORIA, J. M., DURÁN, J. J., PLA, S., GARRIDO,G., GARCÍA GARCÍA, F. & ARRIBAS, A. (2006): A large-mammal site in a meandering fluvial context (FonelasP-1, Late Pliocene, Guadix Basin, Spain). Sedimento-logical keys for its palaeonvironmental reconstruction. –Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,242: 139-168.

VISERAS, C., SORIA, J. M., & FERNÁNDEZ, J. (2004): Cuen-cas neógenas postorogénicas de la Cordillera Bética. –In: VERA, J. A. (Ed.): Geología de España, 576-581;Madrid (Sociedad Geológica de España, Instituto Geo-lógico y Minero de España).

VISERAS, C., SORIA, J. M., FERNÁNDEZ, J. & GARCÍA

GARCÍA, F. (2005): The neogene-quaternary basins of thebetic cordillera: an overview. – Geophysical ResearchAbstracts, 7: 11123-11128.

WEERD, A. VAN DE (1976): Rodent faunas of the Mio-Plio-cene sediments of the Teruel-Alfambra Region, Spain. –Utrecht Micropaleontological Bulletins, Special Publi-cation, 2: 1-217.

Manuscript received: April 28th, 2008.Revised version accepted by the Stuttgart editor: July 10th,2008.

Addresses of the authors:

RAEF MINWER-BARAKAT, ANTONIO GARCÍA-ALIX, InstitutCatalà de Paleontologia, Universitat Autònoma de Barce-lona, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain;e-mail: [email protected]& Departamento de Estratigrafía y Paleontología, Universi-dad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain

ELVIRA MARTÍN-SUÁREZ & MATTHIJS FREUDENTHAL,Departamento de Estratigrafía y Paleontología, Universidadde Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain.

eschweizerbartxxx author