Learning to Be Overconfident - Meet the Berkeley-Haas Faculty

J. Renfrew, G. Gavalas, M. Ugarković, J. Haas-Lebegyev & C. Renfrew, 2013. The other finds from...

Transcript of J. Renfrew, G. Gavalas, M. Ugarković, J. Haas-Lebegyev & C. Renfrew, 2013. The other finds from...

The settlement at DhaskalioEdited by Colin Renfrew, Olga Philaniotou, Neil Brodie, Giorgos Gavalas & Michael J. Boyd

The sanctuary on Keros and the origins of Aegean ritual practice: the excavations of 2006–2008Volume I

ISBN: 978-1-902937-64-9ISSN: 1363-1349 (McDonald Institute)

© 2013 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research

All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Publisher contact information:McDonald Institute for Archaeological ResearchUniversity of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge, UK, CB2 3ER(0)(1223) 333538(0)(1223) 339336 (Production Office)(0)(1223) 333536 (FAX)[email protected]

Distributed by Oxbow BooksUnited Kingdom: Oxbow Books, 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford, OX1 2EW, UK.Tel: (0)(1865) 241249; Fax: (0)(1865) 794449USA: The David Brown Book Company, P.O. Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA.Tel: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468www.oxbowbooks.com

Chapter 31The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Jane Renfrew, Giorgos Gavalas, Marina Ugarković, Judit Haas-Lebegyev and Colin Renfrew

How to cite this chapter:Renfrew, J., G. Gavalas, M. Ugarković, J. Haas-Lebegyev & C. Renfrew, 2013. The other finds from Dhaskalio, in The Settlement at Dhaskalio, eds. C. Renfrew, O. Philaniotou, N. Brodie, G. Gavalas & M.J. Boyd. (McDonald Institute Monographs.) Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 645–65.

645

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Chapter 31

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Jane Renfrew, Giorgos Gavalas, Marina Ugarković, Judit Haas-Lebegyev & Colin Renfrew

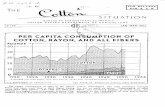

worn that it is difficult to see what type of weaving they represent. The remainder show impressions of three main types of woven mats: circular twined mats, straight twined mats, split warp twined straw mats, and one interesting example of a mat with a multi-stranded changing warp and double twined weft (see diagrams of the different types of weaves found at Dhaskalio in Fig. 31.1). All of them show signs of being at the end of their useful life: most are torn or have holes in them, so that it appears that they had been much used before they were employed in the processes of pottery production, and had not been specially made for that purpose.

In order to study the weaving techniques, posi-tive impressions were taken using dental latex by Daphne Lalayannis of the Naxos Museum. Many of the illustrations show these positive impressions rather than the negatives on the pot sherds as these reveal the weaving technique more clearly.

Circular twined matsDM1 shows up to eight rows of twined weft, neatly done and close together, on a maximum of 29 warps; there are indications of additional warps being added as the mat grew in diameter. The centre of the mat is not shown and it is difficult to know what its original diameter might have been (see Fig. 31.2).

DM2 is one of the best-preserved impressions covering the entire base of the pot (see Figs. 31.3 & 31.4). The pot was not placed on the centre of the mat. There is a maximum of 57 rows of neatly twined weft showing on the base (170 mm diameter). The warps increase from a minimum of 11 at one side, nearest the centre of the mat, to a minimum of 44 round the circumference of the pot base. Additional warps were added when needed in a fairly random fashion as the diameter of the mat increased. As with DM1 the weft was quite tightly woven so that no indication of the nature of the warp could be seen. It is probable that the weft was made from rush stems.

This chapter contains a detailed description of the other categories of find recovered during the excava-tion (with the metal objects following in Chapter 32). It should be noted that bone artefacts are described in Chapter 20 in the discussion by the faunal specialist, Katerina Trantalidou. The shell artefacts are discussed by Lilian Karali in her malacological discussion in Chapter 21. In this way each category of artefact recovered during the excavation has been described in detail.

A: The mat and vine-leaf impressionsJane Renfrew

The mat impressionsThere are twenty-one mat impressions from the Dhaskalio settlement site. Most of them are on the bases of pots, and show considerable wear through the constant use of the vessels. Three of them are so

Figure 31.1. Matting techniques: a) straight twined mat; b) split warp twined mat; c) circular twined mat; d) multi-stranded changing warp with double weft.

646

Chapter 31

DM12 is an impression on a worn pot base and shows a much more open weave circular mat with about 8 rows of weft showing, which appear to have been of straw. The impression is so worn that it is impossible to make out the nature of the warp. It is an example of how difficult it is to interpret worn impressions.

Table 31.1. Circular twined mats.Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.

DM1 VI, 37–8 11151 On 4 sherds fitted together A 31.2

DM2 VII, 3 5388Impression on whole of pot base, 170 mm diameter

C 31.3, 31.4

DM12 XXI, 11 - Worn impression C -

Straight twined matsThe straight twined mats form the largest category represented. Many of the impressions are rather worn. The clearest ones are illustrated and show the range of qualities of matting found.

DM7 shows a coarse mat with five rows of warp and six rows of weft. The mat appears to have been made of straw (Fig. 31.5).

DM13 is of another coarse mat of a loose weave. The impression is rather worn but shows 14 rows of warp and 9 rows of weft and appears neater than DM7. The mat had clearly seen better days as the base of the impression shows that it was badly torn and disintegrating when it was used in the process of manufacturing the pot (Fig. 31.5).

DM14 is of the coarsest weave in this category: 6 rows of warp and three rows of weft are shown in this impression; they appear to be made from thick reed stems, the warps being approximately 10 mm apart (Fig. 31.5).

DM15 shows possibly the neatest mat. Twelve rows of warp can be traced and nine rows of weft. The weave is even, but there are indications towards the top of the impression that this mat was already in a state of disintegration in parts when used for potting purposes (Fig. 31.5).

Table 31.2. Straight twined mats. Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.DM3 III, 3 - Within floor B -DM4 IV, 2 - 1 row weft B -

DM5 V, 2 (C2383)Spout of baking pan, impression on base of spout

B -

DM6 IV, 5 - Worn impression B -DM7 I, 8 8401 Coarse mat B 31.5

DM8 XX, 28 - Rather worn 6 rows weft C -

Figure 31.2. Circular twined mat (DM1).

Figure 31.3. Positive impression of circular twined mat (DM2).

Figure 31.4. Detail of impression of circular twined mat (DM2).

DM1

DM2

647

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.

DM9 XXIV, 1–3

11134, 11161

Extremely worn on 4 base sherds C -

DM10 XV, 1 - Worn, 7 rows weft C -DM11 XI, 11 - Indistinct C -

DM13 VI, 31 11140Three large base sherds with coarse mat impression

C 31.5

DM14 XX, 20 11154 Coarse mat 3 rows weft C 31.5

DM15 XXI, 9 11166Neat, medium weave mat, very clear

C 31.5

Split warp twined straw matsThere are two clear impressions which show the split warp twining technique where the warp strands were alternately split or combined by the weft strands on alternate rows (see Fig. 31.1b).

DM16 covers the entire base of the pot, 170 mm in diameter. It is of a loosely woven mat and like most of the others it shows considerable signs of wear prior to having been used in potting. At least eleven rows of warp are shown and twelve rows of weft. The warp is

made up of many thin strands perhaps of grass stems, and the weft is much thicker, probably of straw (Fig. 31.6).

DM17 is a clear impression of a much neater mat and is a good example of this technique. Eleven warp rows and seven weft rows are shown. The warp is multi-stranded, again probably of grass stems; the weft is probably of straw and much thicker (Fig. 31.6).

Table 31.3. Split warp twined straw mats.Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.

DM16 VII, 7 11143

Coarse mat covering whole base, 170 mm diameter.

C 31.6

DM17 VI, 43 11144 Clear impression C 31.6

Multi stranded changing warp with double twined weftDM18 is the most interesting of these mat impres-sions as it appears to have been made by a different technique. The multi-stranded warp moves from one row of warp to the next by one strand being picked up by the weft and moved across the fabric at each row of the weft. In this case there appear to be four

Figure 31.5. Straight twined mat (DM7); coarse mat impression on three large base sherds (DM13); coarse straight twined mat (DM14); neat, medium thickness, straight twined mat (DM15).

DM7 DM13

DM14 DM15

648

Chapter 31

strands of warp in every row, and as one is transferred across to the right another is taken in from the left by the double-weft threads. In this case the warp and weft appear to have been made of the same materials, which look like rushes. The technique is illustrated in Figure 31.1d and this impression is illustrated in Figure 31.7.

Table 31.4. Multi stranded changing warp with double twined weft.Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.DM 18 II, 30 8403 Clear impression C 31.7

Very worn indistinct impressionsThe Dhaskalio mat impressions show a range of quali-ties and techniques of manufacture. We cannot be sure where these mats were made or used, but we can be certain that they were in their final function during the processes of pottery manufacture, wherever that took place, and that there were competent weavers of mats

in the early bronze age of the Cyclades. The coarse mats were probably used on the floors of houses, but it is unclear as to how the finer mats such as DM2 were used.

Table 31.5. Very worn indistinct impressions.Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.DM 19 IV, 3 5548 Very worn B -DM 20 XXIV, 1 11161 Faint traces C -DM 21 XXIV, 1 11134 Very worn circular? C -

The vine impressions Three vine-leaf impressions on the bases of pots were found in the Phase C levels in Trench VII at Dhaskalio, and a further one came from the surface of the north shore. Two of them (DV1 and DV4) showed that these pots had stood on more than one leaf in the process of their manufacture, the other two show impressions of just a single leaf. All the impressions show prominent veins indicating that the leaves had been used with their smooth side down.

Table 31.6. Vine-leaf impressions.Cat. no. Context SF no. Other details Phase Fig.

DV1 VII, 32 11127 3 overlapping leaves C 31.8

DV2 VII, 28 - Worn impression C -DV3 VII, 37 - Strong central vein C 31.8

DV4North Shore

surface-

2 leaves, one superimposed at right angles to the other

- 31.8

The use of vine leaves as mats for standing hand-coiled pots on during their manufacture enabled them to be turned more easily before the potters’ wheel was introduced. Pieces of old mats were also used for the

Figure 31.6. Coarse mat covering base of pot: split warp twined straw mat (DM16); split warp twined straw mat (DM17).

DM16 DM17

DM18

Figure 31.7. Multi-stranded changing warp with double twined weft (DM18).

649

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

same purpose. Once the pots had dried and were fired an impression of the leaf remained clearly imprinted on the pot base. The use of latex to make a positive cast of the impression clearly shows the veins of the leaf. This use of vine leaves indicates that vines were grow-ing close to the places of pottery manufacture and that the leaves were easily available. Vine-leaf impressions occur frequently on the bases of early bronze age pot-tery in the Aegean. They were already reported from

that Special Deposit North at Kavos excavations of 1987–88 (J. Renfrew 2007, 374–5) and they have also been found at Kavos in the Special Deposit South (Volume II). They were also found at the settlement of Markiani on Amorgos (J. Renfrew 2006a, 195–9). No fewer than 49 vine-leaf impressions on the bases of small bowls were found at Chalandriani on Syros (Sherratt 2000, 355 n.15). It has been claimed that the impressions may have been deliberately used here to decorate the bases of these bowls as most of them are very symmetrically arranged. They have also been found on Paros (Tsountas 1898, 174), Amorgos (Tsoun-tas 1898, 167 pl. 19 no. 24), Siphnos (Gropengiesser 1987, 29, 52 n. 60 pls. 89, 91), Early Helladic Corinth (Kosmopoulos 1948, fig. 45), Synoro in the Argolid (Willerding 1973, 221–40), Zygories (Blegen 1928, fig. 91.2), and the Menelaion, Sparta (Vickery 1936, 32) where the mouth of a LH III jar was sealed with a potsherd and clay which bore the impressions of vine leaves. In Crete they are known from the Early Minoan settlement at Myrtos (J. Renfrew 1972, 239 fig. 107 pl. 183D). Four vine-leaf impressions were found on Early and Middle Minoan pots at Knossos (Renfrew 2011) and they have also been found on pots in the Stavro-mytis cave, Juktas (Sakellarakis & Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1997, 385 fig. 338).

B: Spindle whorls and related objectsGiorgos Gavalas

Only four spindle whorls (with three further shaped and perforated potsherds, which functioned as whorls) were found during the excavations of 2007 and 2008 on Dhaskalio (Figs. 31.9 & 31.10). Three of the whorls, 5818, 12854 and 11167, are fragmentary and have been dated by their context to Dhaskalio Phase C. One is intact: 5484, dated to Phase A.

The spindle whorls and the shaped and perfo-rated sherds have fabrics which are mainly micaceous, corresponding well with those of the pottery. All should be considered imports to the site from other Cycladic islands since none seems to be of local fabric. The whorls are hand-made, but the standardization of their shape suggests the use of some type of mould in their production.

They may be assigned to known spindle whorl types (Carrington Smith 1975):

Flat-discoid: spindle whorl 5818. This type is seen in the Special Deposit North at Kavos (Gavalas 2007b, 377, figs. 10.18–10.19, SF 319), at Markiani on Amorgos (Gavalas 2006, 201, EE420 fig. 8.20:6, EE216 fig. 8.20:9) where it is the most common type, and at Kat’ Akrotiri (Tsountas 1898, pl. 8:4). This is the most common type

Figure 31.8. Vine-leaf impressions DV1, DV4 and DV3 (two with overlapping leaves: DV1 and DV4).

DV1

DV4

DV3

650

Chapter 31

in the Cyclades and rather rare in other areas of the Aegean (Gavalas 2006, 201).

Conical: whorl 12854. This is the most common type all over the Aegean (Cosmopoulos 1991, 87). The type is known at Markiani on Amorgos (Gavalas 2006, 202, EE062, fig. 8.20:3) and from Cycladic cemeter-ies (Tsountas 1898, pl. 8, 5; Papathanasopoulos 1962; Doumas 1977, 199), as well as from Troy, Ayia Irini, Lerna and Phylakopi.

Bi-conical: whorls 11167 and 75484. The type is known mainly from the northeast Aegean (Carrington Smith 1975). 11167 is a combination of uneven cones, the upper flat ellipsoid, the lower truncated, known also from Troy (Schmidt 1902, 205, type Cb), Poliochni Blue (Bernabò Brea 1964) and Sitagroi (Elster 2003, fig. 6.1:b). The cones in 5484 are low and even, resembling examples found at Troy (Schmidt 1902, 206, type Da) and at Sitagroi (Elster 2003, 232, fig.6.2:a).

Their decoration is made up of incised linear motifs, comparable with examples from Markiani phases III and IV and from the northeast Aegean at Troy I (Blegen et al. 1950b, pl. 22, nos. 35–103) and Poliochni Yellow (Bernabò Brea 1976, pl. CCXXX:e). The motif seen on 12854 is formed by groups of crossed oblique straight lines forming a row of lozenges; similar but not identical decoration is seen from Sitagroi (Elster 2003, fig. 6.14), Beycesultan (Lloyd & Mellaart 1962, 274, fig. F.5:2, from level XIV) and from Aphrodisias (Sharp Joukowski 1986, 377, fig. 313:1 & 16). The motif on 11167 is made up of two groups of three parallel curvilinear lines intersecting to form what resembles an eye motif; similar motifs are known from Troy II (Schmidt 1902, 214, nos. 4982, 4502, Taf. VII; Blegen et al. 1950a, 50, phase IIg), from Aphrodisias (Sharp Joukowski 1986, 378, fig. 314:7) and from Tarsus (Goldman 1956, fig. 447:22). Finally, the motif on 5484 with a deeply incised line at the edge of the two cones separating two zones, is known from Troy II (Schmidt 1902, 208, nos. 4499, 4502, Taf. I; Blegen et al. 1950a, 50 phase IIg) and in a different combination from Tarsus (Goldman 1956, fig. 448:26).

The shaped and rounded sherds are mainly body sherds, with flat or slightly concave–convex surfaces, forming ellipsoid or rounded discs. They are also known from the Special Deposit North on Kavos (Gavalas 2007b) and from Markiani (Gavalas 2006, 206). The perforation has been drilled from both sides and in 5380 we see the initial stages of this technique.

The ellipsoid sherd 14009 from Trench IV and the rounded sherd 5392 from Trench VII are dated to Dhaskalio Phase C. The ellipsoid-shaped and

perforated sherd 5380 found in Trench II (Phase B) is contemporary with Markiani phase IV in which many similar-shaped perforated sherds have been found (Gavalas 2006, 206).

Catalogue of Dhaskalio spindle whorls and shaped and perforated sherds (Figs. 31.9 & 31.10)

Spindle whorlsPhase A5484 (II, 26). Bi-conical spindle whorl.Intact: a small part of the surface is missing, burnt. H. 25 mm; D. 27 mm; D. perforation 5 mm; Wt 14 g.Micaceous clay with a few other inclusions, burnished. Two low, even, truncated cones. Incised decoration: a deeply incised line at the edge of the two cones separates two zones. In each a single group of three successive curvilinear lines runs in opposition to the other.

Phase C5818 (VII, 9). Discoid spindle whorl.Fragment: two-thirds preserved.H. 44 mm; Th. 11 mm; D. 40 mm; D. perforation 6 mm; Wt 13 g.Sponge-like micaceous clay with thin inclusions, coated, smooth surfaces.Flat discoid, plain.

12854 (XXV, 15). Conical spindle whorl.H. 27 mm; D. perforation 4 mm; Wt 7 g. Fragmented: sponge-like red-brown clay with thin inclusions. Low truncated cone.Incised decoration: groups of crossed oblique straight lines forming a row of lozenges.

11167 (XX, 8). Bi-conical spindle whorl. H. 17 mm; D. perforation 3 mm; Wt 3 g.Fragmented: one-third preserved.Sponge-like brown clay, burnished; possible traces of a white pig-ment in the incised decoration. Bi-conical shape. The cones are not even. The upper is flat ellipsoid, the lower truncated cone. Incised decoration: two horizontal groups of three parallel curvi-linear lines intersecting to form an eye-like motif.

Shaped and perforated sherdsPhase B5380 (Ii, 17). Ellipsoid-shaped and perforated sherd, probably used as spindle whorl. Fragmented: one-third preserved.L. 5 mm; Th. 10 mm; D. perforation 8 mm; Wt 11 g.Micaceous clay with some thin inclusions.Flat body, part perforated. Funnel-like circular cavities on both sides suggest drilling which had not been completed.

Phase C14009 (IV, 9). Ellipsoid-shaped perforated sherd, probably used as spindle whorl. Fragmented: half preserved.L. 42 mm; Th. 10 mm; D. perforation 10 mm; Wt 11 g.Red-brown coarse clay, talc ware.Irregular ellipsoid, convex-concave. Irregular funnel-shaped per-foration.

5392 (VII, 5). Rounded shaped perforated sherd, probably used as spindle whorl.Fragmented: one-third preserved.

651

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Figure 31.9. Spindle whorls and perforated sherds. Scale 1:2.

0 3 cm

581812854

11167

5484 5380 5392

Figure 31.10. Incised spindle whorls. Scale 1:1.

0 3 cm11167 12854 5484

L. 54 mm; Th. 8 mm; D. perforation outer 6 mm, inner 3 mm; Wt 16 g.Brown clay, talc ware. Nearly rounded, perforation off -centre.

Textile production on DhaskalioA shaped, rounded and perforated artefact of marine shell (see Chapter 21) might also have been used as a spindle whorl. The diameter of its perforation and its weight suggest that it might have been used for the production of a fi ne thread.

The decoration of the spindle whorls may be an indication of their possible use for specialized work (Gavalas 2006, 206). Georgakopoulou’s observation (Chapter 32; see Figs. 32.8 & 32.9) that similar isolated incised signs resembling pott ers’ marks are seen on both tuyères and on spindle whorls should be noted.

Schmidt’s admirable study of the decorated spindle whorls from Troy shows the vast variety of motifs used there (Schmidt 1902).

The distaff s used for spinning seem to have had a thickness between 3 mm to 8 mm as suggested from the range of the diameters of the perforations here. The weights of the shaped and perforated sherds ranges from 11 g to 16 g, suggesting that they were heavier than the whorls and were probably used for other types of thread. In general, however, the spindle whorls and the shaped perforated sherds are not very heavy, from 11 g to 18 g, suggesting that they were used to produce thread possibly from wool instead of linen. The few animal bones found on site (Chapter 20) do not give evidence of animal herding strategies pertaining to wool.

652

Chapter 31

Apart from these four spindle whorls there is lit-tle solid evidence at Dhaskalio for textile production. There are no loom weights. As previously noted from the finds from Markiani and from other Cycladic set-tlements, the lack of loom weights may be indication that in the Cyclades the warp-weighted loom was not in such broad use as it seems to have been in the northeast Aegean (Gavalas 2006, 207–8).

The other equipment perhaps relating to textile production consists only of a few copper needles (Chapter 32). This suggests that such production must have been very limited at Dhaskalio.

The spindle whorls and the shaped perforated sherds were mainly found in the buildings near the summit, chiefly in the building complex of Trenches XX, XXV and Trench VII. But one (from Phase A) comes from Trench II on the east slope. The evidence for various other activities in the same areas suggests that some limited thread-making activity may have occurred along with these, but that no area of the site was used specifically for making thread or for producing textiles.

The study of impressions on pot bases from Dhaskalio (Chapter 31A) and the Special Deposit South on Kavos (Volume II) has revealed many cloth impressions which were formed when pottery was placed to dry upon cloth prior to firing. Pottery was produced elsewhere in the Cycladic islands and was imported to the site and so the occurrence of these impressions gives no insight into the production or use of textiles at Dhaskalio.

Indications of a specific area within a settlement used for textile production are known from Troy (Blegen et al. 1950a), from Myrtos in east Crete (War-ren 1969) and from Asomatos in Rhodes (Marketou 1996). In Markiani on Amorgos, 109 spindle whorls and shaped and perforated sherds were found in one specific location, and in total 203 related artefacts dating to least two settlement phases (Gavalas 2006, 200–201). In contrast only these seven artefacts relat-ing to spinning or weaving were found on Dhaskalio. Colin Renfrew’s suggestion (1972, 351–4), that the Early Cycladic settlements show a high degree of craft specialization may be relevant here: clearly there is no good evidence on Dhaskalio for weaving.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues Peggy Sotirakopoulou and Myrto Georgakopoulou for interesting discussions about these artefacts.

C: Worked sherds and ceramic discsMarina Ugarković

The excavations on the island of Dhaskalio produced a number of finds made from recycled potsherds. These were reworked into their present shapes and finished, as were those found at Kavos. On Dhaskalio, the fol-lowing types are represented: triangular, rounded, oval and disc-like. The rounded ones occur both with and without a perforation. As is also the case with those from Kavos, these modified sherds could have had various uses, according to shape — for instance as pot lids.

Triangular shapeThis small group of finds consists of reworked pot-tery body sherds. They vary in size and fabrics. Their smoothed edges could have been used for burnish-ing pottery prior to firing, but in the absence of other evidence for the production of pottery on Dhaskalio some other use seems more likely. Reworked triangu-lar sherds are dated to Phases B and C.

Phase B

5357 (I, 6). L. 46 mm; W. 38 mm; T. 5 mm. Figs. 31.11 & 31.12.Complete. Coarse, half grey, half orange fabric.Edges well finished or smoothed (from use-wear?). Straight profile. Encrusted.

5379 (II, 17). L. 37 mm; W. 27 mm; T. 8 mm. Complete. Coarse, pink fabric. Edges worn (from use?). Straight profile. Encrusted on both sides.

11130 (I, 35). L. 52 mm; W. 41 mm; T. 8 mm. Complete(?). Coarse, orange farbic with dark grey core.Possibly part of a rounded sherd, deliberately modified. Well fin-ished on both sides. Straight profile.

Phase C

5371 (VI, 12). L. 41 mm; W. 31 mm: T. 6 mm Figs. 31.11 & 31.12.Complete. Coarse, dark orange fabric.Two pointed, and one slightly rounded corner (from use-wear?). Straight profile. Encrusted.

5371.2 (VI, 12). L. 33 mm; W. 29 mm; T. 5 mm. Fig. 31.11.Complete. Medium, orange-light brown fabric.All edges pointed and slightly worn. Straight profile. Encrusted.

10020 (XXI, 11). L.33 mm; W. 27 mm; T. 5 mm.Compete. Coarse, brown fabrics.All edges from use. Straight profile. Encrusted all over.

11125 (VII, 24). L. 35 mm; W. 20 mm; T. 4 mm.Complete. Fine-medium, brown fabrics. Edges worn and slightly rounded (from use?). Straight profile. Encrusted on both sides.

Similarly modified sherds have also been found at late neolithic Nea Makri where they were interpreted

653

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

as ceramic tools (Pantelidou Gofa 1991, 3, fig. 5: 7-124, 12-176, 12-13, 4-57), and in the Special Deposit South at Kavos (Volume II).

Rounded shapeThese are reworked body sherds that vary in size and fabric. They could have been used as stoppers, or pot lids, or for some other unknown purpose. They are represented in Phases B and C, with the majority in Phase B. Rounded circular sherds of diameter greater than 80 mm have been classified as ceramic discs (below).

Phase B

5355 (II, 3). D.36 mm; T. 6 mm.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Chipped edges. Straight profile. Encrusted on the inside.

5355.2 (II, 3). L.48 mm; W. 36 mm; T. 8 mmFragmentary. Coarse, orange fabric.Neatly chipped edges. Straight profile.

5356 (II, 10). L.49 mm; W. 43 mm; T. 11 mm. Fig. 31.12.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Roughly chipped edges. Straight profile. Traces of irregular lines scored on the inside. Partially encrusted.

5358 (II, 6). L. 44 mm; W. 40 mm; T. 11 mm.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Roughly chipped edges. Slightly curving profile. Encrusted on both sides.

5360 (I, 4). L. 28 mm; W. 27 mm; T. 8 mm.Complete. Coarse, half grey half orange fabric.Roughly chipped edges. Straight profile. Encrusted on both sides.

5364 (I, 3). L. 34 mm; W. 32 mm; T. 8 mm.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Chipped edges. Straight profile.

5365 (II, 4). L.34 mm; W. 31 mm; T. 7 mm.Complete. Medium, orange fabric.Neatly chipped edges. Straight profile. Encrusted on both sides.

5370 (I, 11). L. 52 mm; W. 45 mm; T. 10 mm.Complete. Coarse, brown fabric.Roughly chipped edges. Straight profile. Encrusted on both sides.

5372 (I, 12). L.54 mm; W. 51 mm; T. 9 mm.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Roughly chipped edges. Straight profile. Smoother on one side than the other.

5375 ( I, 14). L. 51 mm; W. 43 mm; T. 8 mm.Complete. Meduim, orange fabric.Chipped edges. Smoothed on the inside. Whiteish slip. Straight profile.

5396 (II, 17). L. 49 mm; W. 43 mm; T. 8 mm. Fig. 31.12.Complete. Coarse, grey at core, orange/brown at surface.Roughly chipped edges. Straight profile.

10021 (II, 4). L. 32 mm; W. 16 mm; T. 4 mm.

Fragmentary. Medium, orange fabric. One third of the reworked sherd remains.Neatly chipped edges. Straight profile.

10022 (IV, 9). L. 66 mm; W. 63 mm; T. 9 mm. Fig. 31.11.Complete. Coarse fabric with grey core and thin orange surface.Chipped off edges. Exterior surface with scoring and potters’ mark (x) with slight encrustration.

Phase C

5362 (VII, 4). L. 48 mm; W. 30 mm; T. 8 mm; est. D. 75 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse, brown fabric. One quarter of the reworked sherd remains.Neatly chipped off edges. Slightly curving profile. Encrusted on both sides and on the edges.

10023 (VI, 15). L. 57 mm; W. 40 mm; T. 7 mm; est. D. 80 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse, buff/orange fabric. One quarter of the reworked sherd remains.Neatly chipped off edges. Straight profile. Encrusted.

10024 (XX, 17). L. 33 mm; W. 26 mm; T. 8 mm, est. D. 55 mm.Frgamentary. Coarse/medium grey at core, orange at surfaces fabric. One quarter of the reworked sherd remains.Unusually well-finished edges. Polished surface. Straight profile. Encrusted all over.

12855 (XXV, 15). D. 56 mm; T. 6 mm. Fig. 31.11.Complete. Medium, orange fabric.Smoothed edges. Straight profile. Completely encrusted on the outside.

12865 (XXV, 24). D. 55 mm; T. 7 mm. Fig. 31.12.Complete. Medium fabric with grey core, dark orange on surfaces.Well-smoothed edges. Straight profile.

Besides those from Dhaskalio and Kavos, rounded shapes have been found at late neolithic Nea Makri (Pantelidou Gofa 1991, 3, fig. 4; 5-121, 12-57), Emporio, Chios (Hood 1982, 634, pl. 132:30–41), and at Lithares in Boeotia (Tzavella-Evjen 1984, 214, fig. 92:a–k, m–p).

Rounded shape with perforationTwo objects that cannot be considered loomweights, each with a single complete perforation, were perhaps part of a lead clamp used to mend a broken vase. The lead was connected to a similar piece on the other side of a break. These finds were apparently rounded at a later stage, and perhaps used in some other way. Both are of Phase B.

Phase B

5366 (III, 1). L. 45 mm; W. 40 mm; T. 22 mm; D. hole 9 mm. Figs. 31.11 & 31.12.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Almost rounded clay object that had an intentionally pierced hole in the middle. The perforation is filled with lead. Perhaps part of a lead clamp.

5383 (I, 14). L. 59 mm; W. 46 mm; T. 9 mm; D. hole 6 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse dark grey at core, orange on surfaces fabric. Two-thirds of the reworked sherd remains.

654

Chapter 31

Figure 31.11. Worked sherds and ceramic discs. Scale 1:2.

0 3 cm

5357 5371 5371.2

10022 128555366

10027 10028

11840 12094

Neatly chipped of edges. Surface not smoothed. Curving profile. Traces of irregular lines on the inside, probably from scoring. Part of a lead clamp?

Oval shapeWith finished edges, they vary in size and fabric. Use unknown. Dated mainly to Phase B at Dhaskalio, with two exceptions dated to Phase C.

Phase B

5359 (I, 3). L. 40 mm; W. 21 mm; T. 6 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse, orange fabric. One-third of the reworked sherd remains.Chipped edges.

5361 (VI, 9). L. 30 mm, W. 30 mm; T. 5 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse, orange fabric. Half of the reworked sherd remains.Encrusted on both sides.

655

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Figure 31.12. Worked sherds and ceramic discs. Scale 1:2.

0 3 cm

5357 5371

5366

1209410029

12865

5369 10028

53965356

5369 (I, 11). L. 44 mm; W. 35 mm; T. 8 mm. Fig. 31.12.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric.Straight profi le. Slightly encrusted on both sides.

10025 (V, 3). L. 100 mm; W. 58 mm; T. 8 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse, orange fabric. Half of the reworked sherd remains.Chipped and encrusted edges.

10026 (V, 1). L. 39 mm; W. 22 mm; T. 5 mm.Complete. Coarse, brown fabric.Well-fi nished edges.

10027 (II, 3). L. 25 mm; W.19 mm; T. 5 mm. Fig. 31.11.

Complete. Medium, grey fabric.Well-fi nished and encrusted all over.

Phase C

5363 (VII, 1). L. 72 mm; W. 61 mm; T. 10 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse half grey/half orange farbic. Half of the reworked sherd.Chipped off edges.

10028 (VII, 11). L.43 mm; W. 29 mm; T. 5 mm. Figs. 31.11 & 31.12.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric. Smoothed and encrusted edges. Finished on one side, but not the other.

656

Chapter 31

Besides Kavos, similiar objects, identified as ceramic tools such as burnishers, have also been found at late neolithic Saliagos (Evans & Renfrew 1968, 69/70, fig. 83, pl. 50), late neolithic Nea Makri (Pantelidou Gofa 1991, fig. 6:12-128), FN Kephala on Keos (Coleman 1977, pl. 71b), Lithares (Tzavella-Evjen 1984, 214, fig. 92:σ–φ) and Ayia Irini (Wilson 1999, 161–2, pl. 100, 101 sf 302–35).

Ceramic discsCut with a sharp tool, these objects vary in diameter from approximately 80–100 mm; their thickness is in almost all cases about 10 mm, which suggests that they were recut from the same type of broken vessel. The pots in question were not very well-fired: with one exception, they all have a dark core. Their roughly chipped edges precluded their use for burnishing. The most plausible explanation is that they functioned as pottery lids. All the clay discs from Dhaskalio are of Phase C. Note that Dhaskalio yielded a much greater number of stone discs, in various sizes, although most of them are the same size as the discs made of clay (Chapter 30). Ceramic discs of diameter less than 80 mm are classified as ‘rounded shapes’ above.

10029 (VII, 32). D. 90 mm; T. 9 mm. Fig. 31.12.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric with pink core.Roughly chipped edges. Almost straight profile.

10030 (VII, 11). L. 89 mm; W. 75 mm; T. 17 mm; est. D. 85 mm.Nearly complete. Coarse, orange fabric with grey core.Roughly chipped edges. Almost straight profile. The upper layer on one side removed.

11512 (XV, 2). D. 100 mm; T. 10 mm.Nearly complete. Coarse, orange fabric with dark grey core.Roughly chipped edges. Almost straight profile. Two encrusted breakeges on sides. Small hole on the inside that does not continue to the outside surface. Unfinished?

11840 (XXI, 11). D. 92 mm; T 10 mm. Fig. 31.11.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric with dark grey core.Roughly chipped edges. Almost straight profile. 11924 (XXII, 6). L. 101 mm; W. 65 mm; T. 10 mm; est. D. 100 mm.Fragmentary. Coarse, orange-brown fabric with grey core.Neatly chipped edges. Almost straight profile. Heavily encrusted on both sides.

12094 (XXIII, 14). D. 85 mm; T. 11 mm. Figs. 31.11 & 31.12.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric with dark grey core.Roughly chipped edges. Almost straight profile. Rough on both surfaces.

12096 (XXIII, 14). D. 82 mm; T. 10 mm.Complete. Coarse, orange fabric with dark grey core.Roughly chipped edges. Outside surface smoother then inner. Profile slightly curving.

Similar clay discs have also been found at late neolithic Saliagos (Evans & Renfrew 1968, 70, fig. 85, pl. 54),

late neolithic Nea Makri (Pantelidou Gofa 1991, 3, fig. 4: 12-172, 2-98), Ayia Irini (Wilson 1999, 160, pl. 100), at Phylakopi from A2 and in later periods (Cherry & Davis 2007, 406, 411, pl. 48:l), at Aghios Kosmas (Mylonas 1959, 41, 45, 146, fig. 174), and Emporio (Hood 1982, 634, pl. 132:31).

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Colin Renfrew for the opportunity to study and publish these finds. I am also grateful to Peggy Sotira-kopoulou, for her meticulous study of the Cycladic pottery that led to discovery of these sherds. I am indebted to Pat Getz-Gentle for her suggestions and comments, and for her kindness in improving my English.

D: The bone tubesMarina UgarkovićWith an appendix by Yannis Maniatis

In 2008, excavation on the islet of Dhaskalio produced five worked bone pigment tubes (see Fig. 20.1). These are the only examples of their kind to have been recov-ered at Dhaskalio or Kavos, at least during sanctioned exploration. Although found at many early bronze age Aegean sites and beyond, they are most often associ-ated with the Cyclades, where they had a noteworthy place in the assemblage of artefact types and are found chiefly in sepulchral contexts of EC II. These objects also provide a link between the EC II Keros-Syros and EC II–III Kastri phases (Manning 1995, 86). The examples from Dhaskalio were recovered from layers of Phase C.

Bone tubes 11845 and 11848 were recovered during excavation, while the other three tubes were identified by Trantalidou during her post- excavation work on animal bones (Chapter 20). All animal bones from which tubes were manufactured were identified by Trandalidou and are described in Chapter 20. Bone tube pigment has been analysed by Maniatis (see appendix below).

Catalogue

11845 (XXI, 11). Bone tube. Almost complete. Caprine tibia. Fig. 31.14.L. 101 mm; W 19 mm; T. 1.7 mm. Cylindrical section of a worked bone. Hollowed and with one end narrowed to a point. The opposite end is cut straight. Polished and decorated with incised encircling parallel lines 1mm apart (first group has three lines, the others four, and are at equal distance). Filled with greenish pigment. Encrusted and broken off half-way along the opposite side from the pointed end. 11848 (XXI, 11). Fragmentary bone tube in two joining pieces. Caprine tibia? Fig. 31.16.L. 27 mm + 25 mm; W. 17 mm. Cylindrical sections of worked bone. The ends are missing. Hol-

657

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

lowed. Undecorated. Containing five lumps of green-blue pigment inside a green matrix, with traces of the colour visible on the interior. Pigment is identified as chrysocolla and malachite (see appendix).

10050 (XIV, 8). Bone tube. Left tibia of a caprine. Figs. 31.13 & 31.14.L. 91.7 mm; W. 16 mm; T. 1.6 mm.Cylindrical section of a worked bone. Ends are damaged. Originally polished. Undecorated.

10051 (XIV, 9). Fragment of a bone tube. Tibia of a caprine. Figs. 31.13, 31.14 & 31.15.L. 48.8 mm; W. 14 mm; T. 19 mm.Undecorated. One end damaged, the other is missing. The end of the bone, around the lip, bears grooves at irregular distances (Chapter 20).

10052 (XXV, 15). Fragment of a bone tube. Figs. 31.13 & 31.14.L. 39.6 mm; W. 17 mm; T. 1.6 mm.Reconstructed from three eroded flakes.

Discussion The long bones of sheep, goats, pigs, deer or other animals were used in different cultures, places and periods to make small portable objects. Both handy and durable, bone could easily be hollowed and adapted, and provided a good surface for the addition of incised ornamentation.

The CycladesIn the Cyclades bone tubes have been found at a number of sites, listed here. Graves with at least one tube containing pigment are marked with an asterisk. Graves containing two or more are indicated thus: (×2), (×3) or (×4).

• Ayia Irini on Keos: this is the only one found in a settlement (Krzyszkowska 1999, 159, pl. 99:SF 262).

• Chalandriani on Syros: graves 174, 190, 195, 237*, 255*, 263* (×2), 271, 288, 291, 300*, 307* (×3 or ×4), 308*, 322, 327* (×2), 338 (×2), 351, 355, 356* (×2),

358, 359*, 361, 394, 398* (×2), 417*, 468 (Rambach 2000, 76, 79, 81, 88, 91, 93, 99, 101, 103, 105, 107, 113, 115, 116, 117, 118, 126, 127, 131; pls. 28:2, 29:7, 31:1, 34:4, 36:3, 39:5, 41:6, 42:7, 44:2, 47:7, 50:5 & 7–9, 51:4, 60:4, 175:1–12, fig. 176:1–9, 177:1 & 4–7; Tsountas 1899, 104). (There is a slight discrepancy in the total number of tubes found at Chalandriani: Tsountas says he found a total of 35, but the recorded total is 33, while Rambach accounts for 34.)

• Aplomata on Naxos: graves 15, 18, 23*(×2) (Ram-bach 2000, 157, 158, 161; Kontoleon 1972, 153, pl. 144:a, d).

• Spedos: graves 18*and 21 (Marangou 1990, 52, no. 16; Papathanasopoulos 1962, 126, 127).

• Notina* on Amorgos (Dümmler 1886, 24)

Figure 31.13. Bone tubes. Scale 1:2.

0 3 cm

10050 10052 100510 3 cm

Figure 31.14. Bone tubes 11845, 10050, 10051 and 10052.

10050

1005210051

11845

Figure 31.15. Grooves at end of bone tube 10051.

658

Chapter 31

With the exception of tubes found in graves 300, 358, 359, 394 and 398 at Chalandriani (Rambach 2000, 101, 116, 117, 126, 127; pls. 41:6, 50:8–9, 51:4; figs. 176:1, & 3–9, 177:4) and at Aplomata in graves 15 and 23 (Ram-bach 2000, 157, 161; Kontoleon 1972, 153, pl. 144:b–c) that have no decoration, all bone tubes found in the Cyclades are incised.

The AegeanBone tubes have been found in the eastern Aegean at Troy, Poliochni on Lemnos (Bernabò Brea 1964, 457, 702, pl. CLXXVIII:12), Emporio on Chios (Hood 1982, 674, pl. 141:51) and Thermi on Lesbos (Lamb 1936a, 200, pl. XXVII:30, 41–3, 45). They have been found in the west Aegean at Pefkakia Magoula in Thessaly (Christmann 1996, 311, T.153.15), on Skyros (Parlama 1984, 112), at Manika on Euboea (Papavasileiou 1910, 17; Sampson 1988, 49–53; Sapouna Sakellarakis 1987, 243, pl. 41:c), at Eutresis and Lithares (Tzavella-Evjen 1985, 48, pl. 25:k–o) in Boeotia, at Aghios Kosmas in Attica (Mylonas 1959, 30), on Aegina in the Saronic Gulf, and at Lerna and Tiryns in the Argolid (Kilian 1983, 314, pl. 43:2). They have also been found in the Ionian islands at Steno and Nidri on Lefkas (Kilian-Dirlmeier 2005, 121, pl. 6:9; Zachos & Dousoungli 2003, 35). See further Hekman (2003, 159) and Kilian-Dirlmeier (2005, 167, list 4; Kouka 2008, 276). It should be noted that most bone tubes outside the Cyclades might be considered Cycladic in origin, while others are local versions of the type.

Popular in the Aegean, pigment storage tubes of bone have been found from the eastern Mediterranean and as far as Sardinia and the Atlantic coast in the West (Childe 1925, 45, 61). The earliest examples in the greater Mediterranean area, dated to about 5500 bc, were found at Hacilar (Mellaart 1970, 164). They were also common in Predynastic Egypt and a number of early bronze age sites in Palestine, Lebanon and Syria (Hennessey 1967, 82). Beyond the Cyclades, but within the orbit of their external relations and with a place in the Aegean early bronze age cultural koine, bone tubes have been found as far east as western Anatolia, as far north as Troy, and as far west as Ithaka and Lefkas, with many more places in between.

The tubes occur in two variations that do not seem to indicate a difference in use or contents. The simpler, less common of the two was cut straight at the ends (e.g. Syros, T.356: Tsountas 1899, pl. 10:5, with traces of blue pigment inside). Most numerous are tubes with one end pointed in a simple leaf shape, apparently designed to allow for greater control in transferring the powdery contents to a larger recepta-cle such as a marble bowl. It has been suggested that the pointed tubes might have been used as primitive

fountain pens (Marangou 1990, 52). In such a scenario — unlikely in itself because the tubes contained dry pigments, not paint — it does not seem likely that the flow of paint could have been successfully controlled. Conceivably, however, an empty tube’s point could have been dipped in the paint, much like a Japanese bamboo pen. The opposite end of tubes of both types was sometimes equipped with one or two holes for the attachment of a stopper, only rarely preserved, probably because the stoppers were normally made of wood. Three examples of such stone stoppers (with a hole or holes corresponding to those of their miss-ing tubes) were found by Tsountas (eg. Syros, T.262: Tsountas 1899, pl. 10:4).

In the Cyclades four bone tube stoppers — two of steatite (T.322, T.398), one of ‘stone’ (T.263), and one not identified, but presumably made of soft stone (T.262) have been found at Chalandriani (Rambach 2000, pl. 93:105 & 127; fig. 36.9, 43.4, 57.8, 157.9:11; Tsountas 1899, pl. 10:4). Outside the Cyclades they are found at Manika (Sampson 1988, 314, 311, fig. 71.33 T.IV; fig. 71.35 T.XIII).

With contents still present, as they were in some eleven of the 34 mostly fragmentary tubes found at Chalandriani by Tsountas (1899, 104), they are nearly always in the form of a friable blue substance or residue of blue colour, chiefly from azurite. Recently, remains of green or greenish pigment have also been found in bone tubes: the two Dhaskalio examples, and a third from Naxos (Aplomata T.23: Kontoleon 1972, pl. 144:c).

Analyses have been carried out in the case of the two of four examples in the Louvre. In both tubes the blue pigment was derived from azurite and, to a lesser degree, malachite (Thimme 1977, 543, no. 448a, b) which is often found with azurite. Presumably, if the concentration of malachite were high enough, the resulting pigment would have been green from the start. What appears now as green colour is found also on an EC II marble figure (Hendrix 2000, 136), as well as in an EC II marble bowl and footed cup (Getz-Gentle 1996, 104 with 223 n. 191, 165) and on the underside of the lids of two marble pyxides (Getz-Gentle 1996, 130–31, 145–6). One of the Dhaskalio bone tube pigments has been analysed and described as a blue-green pigment inside a green matrix that comes from a copper ore called chrysocolla and also malachite (see appendix below). The nearest sources of the raw material, chrysocolla ore, can be found on the island of Seriphos.

Only rarely, if ever, do the tubes hold red colouring matter. Deposits were removed from a marble bowl found in early excavations at Spedos on Naxos. In the process, a badly worn fragment of

659

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

a small bone tube was revealed, with red pigment inside the bowl (Papathanasopoulos 1962, 128, pl. 60:ab, T.21). There is no mention of pigment in or on the tube. In 1990 these objects were published again, with the ambiguous statement: ‘There are traces of red pigment inside the vase as well as the upper section of a tubular pigment container’ (Marangou 1990, 68, no. 48). It is unclear from the description that red was observed inside the tube. A tube from Chalandriani contained blue and a vague trace of red pigment (Rambach 2000, 117 T.359, Sf 11820). While the first may or may not have contained traces of red, the second appears to be the only tube described in the literature definitely to have held as much as a trace of red. Broodbank (2000b, 248) mentions tubes holding azurite and cinnabar, but without further documentation. It is worth mentioning, however, that sometimes lumps of red pigment are found in Early Cycladic graves: e.g. Tsountas (1899, 75) in T.142 at Akrotiraki on Siphnos; in T.14 at Dokathismata on Amorgos, and in three graves at Chalandriani on Syros (Tsountas 1899, 104). One is not included in Rambach’s inventory; the others are T.356, which also held two tubes, and T.264 (Rambach 2000, 94, 116). Red pigments did not crumble easily, obviating the need for special storage canisters. A possible lump of red pigment was found at Dhaskalio in Trench XXV layer 3, and others from Trench XXI layer 9, but these have not been analysed. The latter are associated with bone tubes 11845 and 11848.

Cycladic bone tubes, like those found outside the archipelago, were often left undecorated — this is true of four examples from Dhaskalio — but many are ornamented with rectilinear incision. Several have closely-spaced encircling rings covering virtually the entire surface, as on the better-preserved tube from Dhaskalio (11845), as well as on a tube from Syros (Tsountas 1899, pl. 10:5). One was found (with its stopper) at Manika (Sampson 1988, fig. 71.33); another example is of unknown provenance (Thimme 1977, no. 448d). A variety of more complex patterns and motifs was also used. These include horizontally and diagonally hatched triangles and lozenges, zigzag and herringbone, with elements of the design sometimes interrupted or bounded by two or more parallel encir-cling rings (Thimme 1977, fig. 30:1–7; Tsountas 1899, pl. 10:3; Zervos 1957, fig. 262).

Bone tubes from Aegean sites have been found in both settlements and cemeteries, the majority the latter. In the Cyclades bone pigment tubes have hith-erto been associated almost entirely with cemeteries and on only three islands: Syros (Chalandriani, 34 tubes), Naxos (Aplomata and Spedos, six tubes) and Amorgos (Notina, one tube). A single example

comes from a settlement context, on Keos (Ayia Irini). Altogether 47 bone tubes, including the five from Dhaskalio, have now been recorded from the Cyc-lades. Of these, only thirteen or 27% were definitely not found on Syros.

Neither this writer nor Getz-Gentle (pers. comm.) has been able to find any tubes from the Cyclades now outside Greece other than the four tubes in the Louvre (Thimme 1977, no. 448a–d). For the Louvre pigment tubes, Getz-Gentle informs me that she has informa-tion from the Museum that they were acquired in 1956 from the Paris-based antiquities dealer, Nicolas Kout-oulakis, who mentioned Ios as their provenance. Given the information supplied by the Louvre, Getz-Gentle believes it possible that the four tubes were in fact found in the Special Deposit North at Kavos on Keros.

Since Dhaskalio appears not to have been an ordinary settlement and Kavos opposite was not a cemetery in any usual sense of the word, it is difficult to speculate as to the reason for the presence of the five bone tubes containing green and green-blue pigment in a place where there may also have been red ochre. It is not inconceivable that paints were prepared here, or even that there was a place dedicated to ritual painting required for certain rites performed by visitors to the Dhaskalio and Kavos complex.

The bone tubes found on Dhaskalio evidently belong to Phase C, the last phase of the site’s use. This, along with the Syriote stylistic parallel for the decora-tion on 11845, suggests that the pigment tubes from Dhaskalio might have been made at Kastri on Syros where the vast majority have been recovered. Indeed, it is conceivable that all decorated bone tubes found in the Cyclades and at least some of those found else-where in the Aegean may have been produced, over several generations, in a limited number of Syriote workshops.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Colin Renfrew for his trust in giving me the opportunity to publish the bone tubes from Dhaskalio. Gratitude is also given to Katerina Trantalidou for identify-ing the animal bones, and three of the bone tubes during her study of animal bone. I am indebted to Pat Getz-Gentle for her interest in the topic, her suggestions and comments, and for her kindness in improving my English.

Appendix: report on the examination of a blue-green pigment from DhaskalioYannis Maniatis

Object description Remains of blue-green pigment in a bone tube found at Dhaskalio, Trench XXI in 2008 (Fig. 31.16).

660

Chapter 31

Sample and techniquesA small sample was taken from the pigment in the bone tube and was subject to examination and analy-sis with the following techniques: optical microscope examination; and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray analysis.

ResultsThe initial optical examination of the sample revealed that it is an aggregate of blue and green grains in a

pale green matrix (Fig. 31.17). The sample was then placed on a stub coated with carbon and examined in the SEM. Magnification of 227× revealed grains of different size and form; the sample is inhomogeneous. Bulk analysis of the whole sample revealed that its average composition consists mainly of the elements copper (Cu), silicon (Si) and a considerable amount of calcium (Ca) (Table 31.7).

Detailed examination of particular grains (Fig. 31.18) shows that they are mainly composed of Cu and

0 2 cm

Figure 31.16. Fragmentary bone tube 11848.

Table 31.7. Bulk and point analysis with SEM-EDXA.

Area Na2O MgO Al2O3 SiO2 P2O5 SO3 Cl2O K2O CaO BaO TiO2 MnO Fe2O3 CuO ZnO As2O3 PbO

Overall bulk (1.2 × 1.2 mm) 0.71 1.90 1.44 25.28 0.45 0.76 0.00 0.31 42.67 0.53 0.17 0.19 1.42 22.82 0.64 nd 0.71

Blue grain 2 (left of scratch) (Fig. 31.18a)

0.28 0.94 0.89 28.85 0.48 0.41 0.35 0.33 11.63 0.15 0.24 0.16 0.66 50.95 1.15 nd 2.50

Bright particles inside blue grain 2 (Fig. 31.18a)

1.07 1.33 1.10 34.12 0.72 0.36 0.48 0.64 17.68 2.52 nd 0.45 1.25 35.15 0.88 nd 2.26

Green grain, Area 1 (Fig. 31.18b) 0.88 1.10 0.97 20.64 0.41 0.42 0.40 0.34 4.29 nd 0.48 0.43 1.02 62.52 3.37 1.12 1.61

Green grain, Area 2 (Fig. 31.18b) 1.47 1.02 0.99 11.81 0.27 0.00 0.21 0.16 5.65 nd 0.60 0.35 0.87 68.06 5.45 0.88 2.21

Bright particles in grain (Fig. 31.18c) 0.42 0.84 19.97 11.94 14.86 9.29 0.34 0.25 2.16 0.00 0.19 0.19 3.04 11.35 0.54 4.09 20.52

Grey amorphous matrix of above grain (Fig. 31.18c)

0.00 0.63 0.81 50.71 0.25 0.73 0.27 0.16 1.38 nd 0.34 0.77 1.20 37.39 0.79 nd 4.58

Grain no. 1 (Fig. 31.18d) 0.20 0.61 1.64 24.87 nd 0.22 0.19 0.17 4.73 0.25 0.20 0.43 3.14 59.45 1.79 nd 2.10

Figure 31.17. View of the sample from 11848.

661

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

Si and some other elements. Ca is always present but in much lesser amounts in the individual grains. The blue grains contain Cu and Si and an amount of lead (Pb), together with smaller amounts of iron (Fe), zinc (Zn) and aluminium (Al) (Table 31.7). The green grains contain more Cu and less Si and higher amounts of Zn than the blue grains. Arsenic (As) is present only in the green grains (Table 31.7). Rare grains rich in Pb are also present (bright particles in Fig. 31.18c) and they also contain high amounts of phosphorus (P), sulphur (S), Al and As (Table 31.7). Also a certain amount of Fe is present.

The presence of Cu together with Si indicates that this pigment is derived from a specific copper ore called chrysocolla. A typical chemical formula of pure chrysocolla is (Cu,Al)2H2Si2O5(OH)4•n(H2O) and its typical composition is shown below:

Al2O3 (%) CuO (%) SiO2 (%) H2O (%)3.88 42.39 36.59 17.14

Full data and detailed description may be found at http://webmineral.com/data/Chrysocolla.shtml.

Figure 31.18. A: Image of blue grain from sample from 11848, scale in microns; B: image of green grain from 11848 (see Table 31.7), scale in microns; C: image of grain containing particles rich in Pb, P, S and As bright particles in a matrix rich in Si and Cu (grey background), scale in microns; D: image of grain 1 from 11848 (see Table 31.7), scale in microns.

662

Chapter 31

The natural ore of chrysocolla usually contains small amounts of lead oxides, iron oxides, magnesium oxides and zinc oxides and very small amounts of lime. These are all compatible with the analysis of the pigment in the bone tube, apart from the lime which is unusually high in the Dhaskalio pigment.

The appearance of chrysocolla ores (as can be seen in the examples given in the reference above) are the same as the Dhaskalio pigment and contain a mixture of blue and green grains (Fig. 31.19). The greener areas are malachite (copper hydrous carbon-ate). Indeed, as can be seen from Table 31.7, the green grains of the Dhaskalio sample contain much more copper than Si and this together with the presence also of As indicates that the green grains are mala-chite. The blue grains however are pure chrysocolla.

The high amounts of Ca contained in the bulk of the sample are not characteristic of the natural ore and may indicate that either powdered calcite was mixed with the copper ore to make the colour paler blue-green or that it has been absorbed by the pig-ment from the surrounding bone tube and the highly calcareous environment of Dhaskalio.

ConclusionThe blue-green pigment in the bone tube in Trench XXI has been identified as the copper ore chrysocolla containing also malachite. It is possible that the pig-ment was mixed with white calcite to make the colour paler blue-green, but the enrichment with Ca from the bone and especially from the high calcareous soil of Dhaskalio cannot be excluded. The closest place known to have chrysocolla ores is the island of Seriphos.

E: Other finds of stoneJudit Haas-Lebegyev & Colin Renfrew

Ornaments: stone beads and pendantFour jewellery items made of stone were found during the excavations between 2007 and 2008 in Dhaskalio. Three are beads made of semi-precious stones: one is of a translucent stone, rock crystal or calcite, and two others of carnelian (Figs. 31.20 & 31.21). The fourth piece is a pendant made of a decorative limestone (Figs. 31.22 & 31.23).

Apart from some minor damage, all four pieces are complete. Apparent wear marks are seen only on the limestone pendant, in the form of discolouration at the two perforations caused by the suspension string.

The rock crystal or calcite bead (5166) was found in the eastern slope of the island, in Trench II, while the two carnelian beads and the limestone pendant were recovered on the summit area (the beads 11017 in Trench XXI, and 12562 in Trench XX, and the pendant 5835 in Trench VII).

The three beads from Dhaskalio belong to three different shape variants, representing characteristic forms of beads of the Cycladic early bronze age: the rock crystal or calcite bead (5166) has a spherical shape, whereas one of the carnelian beads is of short biconical shape (11017), and the other is of elongated, slightly biconial shape (12562).

Spherical beads are often made of rock crystal, a hard stone available in the Aegean and valued for its transparency. Carnelian, however, can be considered as a rare, exotic stone. It is found in India and southern Iran. So far no sources are known from the Aegean, thus the Aegean examples of the early bronze age can be considered as imports from Egypt, Anatolia or from the Near East (Reinholdt 2008, 52). It may, however, have been found in the coastal areas (Reinholdt 2004, 1117, n. 132; 2008, 54). Its use within the Aegean is first attested from the early bronze age, with a distri-bution pattern mostly restricted to the Cyclades and Crete (Banks 1967, 251; Reinholdt 2008, 53; for Crete: Effinger 1996). In the mainland from an early bronze age context it is only known from two graves found at Zygouries (Tomb VIIa and Tomb XX: Blegen 1928, 43–55; Konstantinidi 2001, 55) and from a hoard found at Kolonna on Aegina (Reinholdt 2004, 1117; 2008 16, 52–4). Carnelian beads found in the Cyclades are most frequently carved in a variety of biconical shapes. An elongated biconical carnelian bead was also found in the Special Deposit North at Kavos (Birtacha 2007a, no. 411, figs. 9.15, 9.16).

All three types of bead usually form part of a necklace. This may be made up from beads of the same material and shape, as shown by a necklace of barrel-

Figure 31.19. Characteristic ore sample of chrysocolla with malachite.

663

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

shaped steatite beads from the Phyrrhoghes cemetery on Naxos, grave 27, dated to the Grott a-Pelos culture (Papathanasopoulos 1981, 139, no. 67; Marangou 1990, 58, no. 24). Or it may be made of beads of diff erent materials and shapes, as evidenced by a necklace from Naxos, Akrotiri, grave 8 (Marangou 1990, no. 26) again dated to the Grott a-Pelos culture, or by another from Despotikon, Zoumbaria, grave 135 of the Keros-Syros culture (Papathanasopoulos 1981, no. 64). The closest parallel for a necklace composed entirely of similar short biconical and elongated biconical carnelian beads similar to 11017 and 12562 is known from the early bronze age Treasure E from Troy (Trejster 1996, 111, nos. 121–2) and from the Kolonna hoard from Aegina (Reinholdt 2004, Taf. 15; 2008, 117, Taf. 3).

The elongated ellipsoid stone pendant (5835), pierced at the two ends, most probably had an orna-mental function. It could have served as a pendant worn in a horizontal position. From the Cyclades simi-lar elongated pendants likewise made of limestone usually have only one end perforated, and thus were worn in a vertical position (Amorgos, Kapros grave 17: Tsountas 1898, pl. 8:65, Rambach 2000, Taf. 3:5, 180:5).

Several similar pieces with a pierced hole at each end are known from Lerna and Kolonna from Early Helladic III contexts, and from Early Minoan vaulted tombs in the Mesara plain in southern Crete. These objects, based on analogous examples known in large numbers from the area of the Bell Beaker culture, were recently interpreted as ornamental parts of wrist guards (probably made of leather) serving to protect the arm from the recoil of the bowstring (Maran 2007, 13–14; Rahmstorf 2008b, 160–61). The best parallel for 5835, found in an Early Helladic III date context at Kolonna (Rahmstorf 2008b, 160, fi g. 5:2), conforms with the Phase C date of the Dhaskalio object.

Similar objects, however, are known from earlier and later contexts as well. A stone pendant of similar shape and with perforations at both ends was found at Prodomos, Thessaly, and dated to the neolithic period

(Kyparissi-Apostolika 2001, no. 732, pls. 26, 44). A c. 200 mm long object of similar shape with a pierced hole at one end came to light in a late MH–early LH context, in the so-called Grave Circle in Pylos, and was interpreted as a hone (Taylour, in Blegen et al. 1973, 167, fi g. 232:3).

As the parallels cited above indicate, beads and pendants are usually found in graves or as part of hoards in the early bronze age Aegean, and are only very rarely recovered in other contexts. The stone ornaments found in Dhaskalio thus provide clear evidence that they were also made to be worn by the living and did not only accompany the dead or end up deposited in hoards.

Catalogue

Phase B5166 (II, 3). Almost complete. Preserved L. 6.5 mm; D. max. 7.5 mm; D. perforation 2.5 mm; Wt 0.5 g. Figs. 31.20, 31.21.Rock crystal or calcite. According to Dixon the source could be from a local calcite vein.Spherical semi-translucent, polished calcite bead. Straight perfo-ration, drilled from both sides. Small, recent breakage at one end, otherwise intact.

Phase C11017 (XXI, 9). Complete. L. 4.5 mm; W. 5 mm; T. ends 4 mm, max. (middle) 5.5 mm; D. perforation 2 mm, in the lower half aft er 1 mm the diameter of the perforation narrows to 1 mm; Wt 0.5–1 g. Figs. 31.20, 31.21.Carnelian.Reddish-orange, small, biconical, semi-translucent, polished car-nelian bead. Longitudinally pierced. Biconical perforation, drilled from both sides. On the orange surface diagonal darker patches.Parallels: Carnelian beads of identical shape: Aegina, Kolonna, hoard, fi ve identical beads forming part a necklace of carnelian beads of various shapes (Reinholdt 2004, 1117, Taf. 15:4; 2008, 109, nos. 037, 039, 040, 041, 042, Taf. 3, Taf. 13, 2–3); Troy (Treasure E: Trejster 1996, 111, no. 121); one identically shaped bead in a neck-lace of six carnelian beads of various shapes; and a separate piece

0 2 cm

5166 11017 12562

Figure 31.20. Stone beads 5166, 11025, and 12562. Scale 1:1. 0 2 cm

5166

11017

12562

Figure 31.21. Stone beads. Scale 2:1.

664

Chapter 31

in Treasure L (Trejster 1996, 172, no. 219). Compare also Poliochni (Bernabò Brea 1976, pls. CCXLVII:c–d, CCLII:1).

12562 (XX, 30). Complete. L. 15.5 mm; W. 5 mm; T. middle 5 mm, ends 4 mm; D. perforation 2.5 mm, 3 mm; T. at end 1 mm; Wt 1 g. Figs. 31.20, 31.21.Carnelian.Elongated slightly biconical, semi-translucent, polished reddish-orange carnelian bead with light pink spots. Longitudinally pierced. Straight perforation, drilled from both sides. Small chip broken off at one end.Parallels: Carnelian beads of identical shape: Aegina, Kolonna, hoard, one bead in a necklace composed of carnelian beads of vari-ous shapes (Reinholdt 2004, 1117, Taf. 15:4; 2008, 109, no. 038, Taf. 3, Taf. 13, 2–3); Troy, Treasure E, as centre-piece of a necklace of six carnelian beads of different shapes, and a separate piece (Trejster 1996, 111, nos. 121, 122). Similar, but more strongly biconical bead from the Special Deposit North, Kavos, Trench I, unit 112 (L. 20 mm; T. 20 mm: Birtacha 2007a, 365, no. 411, fig. 9.159:16). Eleven carnelian beads of similar shape, but narrower ends, forming part of a necklace together with fifteen spherical carnelian beads from Eutresis, grave 6 (Middle Helladic: Goldman 1931, pl. XX:1).

5835 (VII, 11). Complete. L. 75 mm; W. max. 18 mm (at the middle), min. 65–70 mm (at the two ends); T. max. 7.5 mm (at the middle), min. 35 mm (at the ends); D. pierced holes 35 mm; Wt 16 g. Figs. 31.22 & 31.23.Brownish-grey limestone or siltstone with pinkish in-filled bur-rows. The stone was described by Dixon as: ‘metamorphosed ferruginous siltstone with in-filled burrows. Now crystalline with scattered enedral magnetites, more in burrow fill than matrix. Bur-row form shows it was sediment and has not been deformed: i.e. metamorphosis not accompanied by deformation. Hence doubtful if Naxos but magnetites suggest emery affinity’. Source: uncertain, possibly Naxos.Elongated, ellipsoid limestone pendant, with straight ends, one flat

side, and plano-convex from the ends towards the middle of the other side with smooth, polished surface. Pierced at the two ends. Two asymmetrical bulging biconical perforations drilled obliquely from the two sides meeting in the middle. Ancient and probably also recent scratches on the flat side, and curving upper surface. On the flat surface ancient diagonal scratches concentrating especially at one pierced end. Horizontal scratches around the longer side of the upper surface. At one pierced end on both sides a whitish patch: the discolouration is probably caused by a suspension string.Parallels: Aegina, Kolonna, from EH III layer (5b/06-6 Λ 21: Rahmstorf 2008a, 160, fig. 5:2). A fragmentary piece from the same site, also of EH III context, originally belonged to a similar piece (7a1-2/03 Λ 24: Rahmstorf 2008a, 160, fig. 5:4). A stone pen-dant of similar shape and with comparable dimensions, but with only one perforation, is known from Amorgos, Kapros, grave 17 (Tsountas 1898, pl. 8:65; Rambach 2000, 14, Taf. 3:5, 180:5). From the neolithic period, a similar stone pendant also pierced at both ends, from Prodromos, Thessaly (L. 88 mm; W. 15 mm: Kyparissi-Apostolika 2001, no. 732, pls. 26, 44). From middle to late bronze age contexts, similar objects but pierced only at one end: Tarsus, L. 108 mm (Goldman 1956, fig. 418:102); Pylos, so-called Grave Circle (Taylour, in Blegen et al. 1973, fig. 232:3). Outside the Aegean a very similar piece is known from a Bell Beaker burial in Slovakia (Vladár 1977, pl. 6:5).

Miscellaneous objects A small rock crystal disc (11849, Figs. 31.24 & 31.25) discovered in Trench XXI has no close parallels from the early bronze age in the Cyclades. Similar objects of early bronze age date were found in ‘Treasure L’ at Troy, in which 46 similar, but slightly larger (c. 24–25 mm in diameter) flat or plano-convex rock crystal discs (‘lenses’) were included (Trejster 1996, 156–69,

5835

Figure 31.23. Stone pendant 5835. Scale 1:1.Figure 31.22. Stone pendant 5835. Scale 1:1.

0 3 cm0 3 cm

5835

665

The Other Finds from Dhaskalio

173–6, nos. 176–216, 222–4, 229–30). Since traces of bronze- and iron-oxide were found on several of the Trojan discs, they were interpreted by Schmidt as inlays of bronze belts (cited by Trejster 1996, 224); Ble-gen, however, was of the opinion that ‘the small seg-ments of rock crystal were perhaps used as counters in a royal game, or may have been utilized as inlays’ (Blegen 1963, 77).

A number of slightly plano-convex rock crystal discs of comparable dimensions to the disc from Dhaskalio were found in Crete in later contexts. Several pieces of usually larger dimensions were discovered at the Temple Repositories at Knossos in a Middle Minoan IIIB context, occasionally backed with silver and gold foil on their flat surface; they were interpreted as decorative inlays on gaming boards (Evans 1921, 469–72). A disc of exactly the same size as the Dhaskalio piece was found together with other rock crystal objects of different shape in a Late Minoan II context in Room P of the Unexplored Mansion at Knossos (Popham 1984, 82, P 40, pl. 219:17): this was interpreted as either for use on a gaming board or serving as an inlay on a piece of furniture (Evely 1984, 240). Of Late Minoan IIA–III date are several pieces found in the Palace of Knossos and in the Mavrospelio cemetery (Forsdyke 1927, 288, fig. 40:VII A.13; Sines & Sakellarakis 1987, 191–2, fig. 3). For the use of the three pieces found in the Mavrospelio cemetery, For-sdyke listed several possible explanations: as inlays, as optical instruments, or as burning-glasses (Forsdyke 1927, 288). Based on the examination of several similar rock crystal discs found in a possibly Archaic Period context in the Idaean cave, Sines and Sakellarakis suggested that these objects in general, together with the early bronze age pieces from Troy and the Late Minoan discs from Knossos and Mavrospelio, served as magnifying lenses (Sines & Sakellarakis 1987, 191–3). Through its very slightly convex upper surface, the Dhaskalio disc does have some magnify-ing properties but, as the magnification is not large,

and as its surface is not completely transparent, it has some distortion. This object therefore probably served other, most probably ornamental, purposes. The same opinion was expressed by Evely concerning the Minoan ‘lenses’ (Evely 1984, 293–4, n. 113). Moreover, Sines and Sakellarakis also suggested that rock crystal discs, even when giving some magnification, could have served as ornaments or gaming pieces and not, or not only, as lenses (Sines & Sakellarakis 1987, 196).

The rock crystal disc was found close to an incised decorated bone tube containing green pigment (11845, see Chapter 31D), along with pieces of red pigment (11836), and fragments of copper pins (11839, 11844 and 11850). The connection with these finds may have been accidental, but they could also form part of a set of related objects. Association between metal artefacts and pigments was also observed in Cretan contexts. For a pair of similar rock crystal discs found in Grave III at the Mavrospelio cemetery, Forsdyke supposed some connection with a small bronze bal-ance and a lead weight found in the same tomb as part of the apparatus of a craftsman (Forsdyke 1927, 288). A disc from the Little Palace at Knossos, used as inlay for the eye of a steatite bull’s head rhyton, was painted on its lower surface (Evans 1914, 82).

Catalogue

Phase C11849 (XXI, 11). Complete. D. 16.5 mm; T. 6 mm; Wt 3 g.Rock crystal.Translucent, disc-shaped object. Circular ends with flat surfaces, slightly convex, short vertical sides. Small chips broken off at the edges.From the eastern part of the trench, from the upper floor surface. Near to an incised decorated bone tube containing green pigment (11845, 11848), along with pieces of red pigment (11836) and frag-ments of copper/bronze objects including tweezers (11839, 11844). On floor surface associated with layer 11.Parallels: Similar flat, but oval shape fragmentary rock crystal disc from Treasure L at Troy (Trejster 1996, 174, no. 224). Similar discs from Late Minoan and later contexts; Palace at Knossos (Sines & Sakellarakis 1987, fig. 3); Idaean cave (Sines & Sakellarakis 1987, figs. 1, 2).

11849

0 3 cm

Figure 31.25. Rock crystal disc 11849. Scale 1:1.Figure 31.24. Rock crystal disc 11849. Scale 1:1.

11849

0 3 cm

![E=F9;mklge]j ZYjge]l]j L`ak lae] alÌk h]jkgfYd2 ^jge [gfkme]j lg [g%[j]Ylgj](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/631789cb7451843eec0ab6f2/ef9mklgej-zyjgelj-lak-lae-alik-hjkgfyd2-jge-gfkmej-lg-gjylgj.jpg)