ISSUES IN ACCOUNTING EDUCATION Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance...

Transcript of ISSUES IN ACCOUNTING EDUCATION Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance...

ISSUES IN ACCOUNTING EDUCATION American Accounting AssociationVol. 26, No. 4 DOI: 10.2308/iace-500662011pp. 701–723

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matterto Student Performance and SatisfactionWhen Taking the Introductory Financial

Accounting Course?

Ronald F. Premuroso, Lei Tong, and Teresa K. Beed

ABSTRACT: Teaching and student success in the classroom involve incorporating

various sound pedagogy and technologies that improve and enhance student learning

and understanding. Before entering their major field of study, business and accounting

majors generally must take a rigorous introductory course in financial accounting.

Technological innovations utilized in the classroom to teach this course include Audience

Response Systems (ARS), whereby the instructor poses questions related to the course

material to students who each respond by using a clicker and receiving immediate

feedback. In a highly controlled experimental situation, we find significant improvements

in the overall student examination performance when teaching this course using clickers

as compared to traditional classroom teaching techniques. Finally, using a survey at the

end of the introductory financial accounting course taught with the use of clickers, we

add to the growing literature supporting student satisfaction with use of this type of

technology in the classroom. As universities look for ways to restrain operating costs

without compromising the pedagogy of core requirement classes such as the

introductory financial accounting course, our results should be of interest to educators,

administrators, and student retention offices, as well as to the developers and

manufacturers of these classroom support technologies.

Keywords: audience response systems (ARS); clickers; interactive pedagogy; learning;

online homework manager systems (OHMS); satisfaction.

Data Availability: Contact the first author for the data used in this study.

Ronald F. Premuroso is an Assistant Professor, Lei Tong is a Masters of Accountancy Graduate, and TeresaK. Beed is a Professor, all at The University of Montana.

We appreciate comments and suggestions received from workshop and conference participants of the School of BusinessAdministration at the University of Montana and the School of Business at Montana State University. We thankProfessor Terri Herron for her comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript. We also thank studentsat the University of Montana for participating in this study, the School of Business Administration at the University ofMontana for financial support provided for this study, the Advising Department of the University of Montana School ofBusiness Administration, including Sue Malek and Tara Kirkham, for their help in the data collection required for thisstudy, and Lingqian Jiang and Jessica Trethewey for their assistance in the final preparation of the manuscript. Theexperiment using human subjects described in this manuscript was approved by the Institutional Review Board for theUse of Human Subjects in Research at the University of Montana. We also thank Bill Pasewark (editor) and threeanonymous reviewers for comments on a prior version of this manuscript.

Published Online: November 2011

701

INTRODUCTION

Many higher institution education budgets are under pressure (and possibly for the

foreseeable future) from a combination of shrinking state revenues, the growth of

online and/or distance learning programs, reduced donor contributions, and the

inability (in the current economic environment) to raise student tuition to cover ever-increasing

operating costs. Simultaneously, the introduction of course-related classroom technology systems

potentially allows colleges to consider larger class sizes for certain required courses in the

curriculum without reducing the quality and pedagogy of such courses. The use of new classroom

technologies may also create a more interactive and dynamic teaching-learning environment

compared to the traditional lecture-style classroom. Therefore, combined use of sound pedagogy

and/or technology can potentially improve student learning experiences and enhance their

understanding of the related course material for courses in certain academic disciplines (Chan and

Snavely 2009).

A relatively recent innovation in the classroom is the use by instructors of Audience Response

Systems (ARS), otherwise known simply as ‘‘clickers.’’ Clickers allow students to respond to

instructor-posed problem sets or questions in the classroom. The system software immediately

summarizes the answers submitted by all students and displays a graphical summary of the results

that the instructor can display in the classroom. In principle, clickers should be beneficial to

students by engaging them actively in the learning process and providing them with immediate

feedback to answers to the problem sets or questions. Additionally, clickers also should benefit

instructors, providing them with instant feedback about the class’s comprehension of various core

course concepts tested by problem sets or questions.

Clicker systems can be implemented at a relatively low cost to both students and universities.

For students, the cost of the clicker ranges from $30–$50 (less, if used). Most clickers are reusable

and powered by commonly available batteries that generally last at least one semester. Suppliers of

clicker-type technologies normally provide the instructor module and a USB drive for recording

student clicker responses to questions posed in the classroom without cost. Also, no special

hardware or software investment is required by the university to operate the clicker in the

classroom as most clicker systems use commonly available computer hardware and software

technologies.1

Most universities require business majors to take up to two introductory accounting courses:

an introduction to financial accounting course and an introduction to managerial accounting

course. Typically, introductory accounting courses are taught using traditional lecture methods

covering textbook concepts, a series of examinations, quizzes, homework assignments, and/or

homework using a web-based online homework manager system (OHMS). It is important for

educators and instructors to understand the potential impact of using the clicker technology, from a

student perspective including student performance, in teaching these introductory accounting

courses.

We study the effectiveness of using clicker technology in the classroom on student

performance, specifically for the introductory financial accounting course. Prior research generally

shows a positive relationship between student performance on ‘‘pen-and-paper’’ homework

assignments and student final grade performance in many college courses, including both

1 The authors acknowledge there is a wide variety of clicker classroom solutions available in the marketplace, withvarying choices of business models that can be employed by the university and the instructor. The pricingstrategy employed by i . Clicker, as described in this paragraph, is the exception, rather than the norm, in thatmany educational institutions may face high investments in hardware, software, and technical support if theypursue a campus-wide, clicker-type solution (compared to an individual classroom application).

702 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

introductory and upper-level accounting courses (Beed and Evans 2008; Rayburn and Rayburn

1999; Ryan and Hemmes 2005). Prior research also shows a generally positive relationship between

student performance in the introductory accounting course and the use of web-based OHMS in a

variety of courses (Berry 2009; Gaffney et al. 2010). Also, no studies exist that specifically address

the impact of using the clicker on student performance in the introductory financial accounting

course as compared to or combined with traditional teaching pedagogy in a highly controlled

experiment.

We accomplish the first objective of studying the effectiveness of clicker technology by

analyzing student performance in the introductory financial accounting course, first using in-class

quizzes and graded homework assignments and a web-based OHMS in one semester, and then

using clickers as a substitute for the in-class quizzes and graded homework assignments in a

subsequent semester, to determine if the use of the clicker matters to student performance in this

course. We undertake a highly controlled experiment, whereby the same instructor teaches the same

introductory financial accounting course in two different semesters, using the same course textbook,

instructor notes, course examinations, and OHMS homework questions. The only differentiating

factor between the two classes is the use of the clicker in the classroom as a substitute for the other

traditional methods of stimulating student interest in the course materials (in our case, for the

quizzes and homework assignments). The goal is to estimate the potential impact the clicker makes

on student performance in the introductory financial accounting course by comparing student

examination results in the two classes.

Also, accounting studies seldom use multivariate analysis, including controlling for other

factors, in evaluating the effectiveness of technology on student course grade performance in the

introductory financial accounting course.2 Most prior literature focuses on the results from either

univariate or survey methodologies to evaluate the technology impacts from the clicker on student

performance. In general, prior literature shows several factors contribute to a student’s performance

in accounting courses. We control for these factors in the multivariate models included in our study,

including grade point average (GPA), gender, the student’s declared major at the time of taking the

course, as well as other factors, to better isolate the impact of clicker use on student grade

performance in the introductory financial accounting course.

Second, this paper provides feedback on a series of survey questions asking students to rate

their experience with the clicker in the introductory financial accounting course. It is important to

understand student perceptions at the end of the semester after using the clicker in the introductory

financial accounting course, as this will inform educators considering the use of clickers in such

courses.

This study will help deans and other administrators evaluate the use of technology such as

clickers to restrain operating costs in these challenging economic times while simultaneously not

compromising course quality, related delivery, and teaching pedagogy in the classroom. The Office

of Student Retention on campuses also should be interested in our results if changes in teaching

pedagogy result in lower student failure rates in core courses such as the introductory accounting

courses. Further, our results should be of interest to the developers and manufacturers of classroom

support technologies, as they consider new or incremental product developments that could increase

the pedagogical content of the future classroom delivery of courses, such as the introductory

accounting courses, across the nation. Finally, our results should be of interest to all accounting

instructors who are looking for ways to stimulate student interest in the classroom when teaching

2 We discuss, compare, and contrast later in this manuscript literature with regards to the use of multivariateanalysis in the introductory managerial accounting course, a course that differs in both course content and topicalcoverage from the introductory financial accounting course.

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 703

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

the introductory accounting courses required of most business majors, while simultaneously

potentially increasing the instructor ratings3 they receive from students. Accounting instructors also

can benefit from a number of other direct and indirect benefits of using clickers in the classroom,

including the reduction of either instructor and/or student assistant time spent grading traditional

pen-and-paper based quizzes and homework assignments and a reduction in errors when grading

such student work.

This manuscript is organized as follows: the next section reviews the literature related to both

business and accounting course studies regarding clicker use in college classrooms. This section

includes a brief history of the use of the clicker, how the clicker works functionally in the

classroom, student attitudes toward the clicker, and relevant literature to date. We then develop

hypotheses related to usage of the clicker in the introductory financial accounting course. Next we

discuss in detail our controlled experiment involving the use of the clicker compared to traditional

classroom methods. A discussion of the results of surveys performed in the class using the clicker,

including the descriptive statistics for the introductory financial accounting courses using and not

using clickers, is included. This is followed by the discussion of the results of the multivariate

models. Finally, we summarize our conclusions, discuss limitations of our study, and outline areas

for future study related to the use of clickers in the introductory accounting courses.

CLICKER BACKGROUND INFORMATION, LITERATURE REVIEW,AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Brief History of the Use of Clickers in the Classroom

The use of clickers in college classrooms has grown extensively since the technology was

introduced in the 1980s. For example, at the University of Colorado, 19 departments, 80 courses,

and over 10,000 clickers were in use during the Spring 2007 semester alone (Keller 2007). One of

the major suppliers of clickers (i . Clicker: see http://www.iclicker.com) estimates the company

has sold approximately 3 million clickers for use in the U.S. educational market alone.

Virtually every academic discipline, including the sciences, arts, and business, has introduced

various clicker systems into their classrooms at colleges and universities across the nation and the

world (Zhu 2007). Instructors use clickers in the classroom for a variety of purposes, depending on

the learning objectives of the course and the teaching methods and pedagogy employed by the

instructor, including the following:

� To assess student subject knowledge on a topic currently being covered or recently covered

in the class before moving on to the next subject;� To evaluate students’ understanding of new materials about to be covered or assigned by the

instructor before a certain class meeting;� To initiate classroom discussions on new or difficult course-related topics;� To record student class attendance and participation;� To gather student feedback on instructional teaching methods; and/or� To administer tests and/or quizzes during a lecture (Zhu 2007).

3 The instructor (who is one of the co-authors of this manuscript) received either statistically significantly higher(ssh) or similar (s) ratings from students taking the introductory financial accounting course in the class using theclickers compared to the class not using the clicker, in the following categories contained in the university’sstandard Course and Instructor Evaluation Form: Student Interest Level (ssh); Intellectual Challenge (s); StudentEffort Level (s); General Course Quality (ssh); Instructor Availability (s); Instructor Explanations (ssh);Instructor Preparedness (ssh); and Instructor Effectiveness (ssh). These instructor evaluation results are also arobustness test of the results comparing student satisfaction using a clicker compared to not using a clicker in theintroductory financial accounting course later in the manuscript.

704 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

The above list is certainly not exhaustive and also includes, potentially, a combination that the

instructor may choose from among any of the above-mentioned uses. The only limitation on the

innovative application of clickers in the classroom is the creativity of the instructor (Zhu 2007).

What Is an Audience Response System (ARS) and, Consequently, a Clicker?

The general type of ARS system available in the market today consists of three components:

� The clicker itself (see Exhibits 1 and 2) is a wireless handheld transmitter approximately the

size of a small TV control transmitter. It can be used individually by each student to transmit,

for example, an answer choice using primarily radio frequency transmission technology;� The instructor’s receiver module (Exhibit 2) is a relatively small transportable device,

including an antenna (receiver) that receives each student’s individual response to a problem

or question posed by the instructor. The receiver module records the response on a

removable USB storage device; and� The software included in the receiver module allows the instructor to record and display, in

graphical form in real time in the classroom, the total class-related student responses to

questions posed by the instructor immediately after a question is asked. The instructor,

EXHIBIT 1Illustration of Use of the Clicker by Students in the Classroom Answering

Instructor Questions

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 705

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

therefore, can evaluate the entire class’s comprehension of any particular course concept

posed during class, quickly and efficiently. After class, the instructor electronically transfers

the student data captured in the USB storage drive to the gradebook contained in a learning

management system (LMS). The software included in the instructor module leaves a detailed

trail, including the answer submitted by each student and the correct answer for each

question posed by the instructor during any particular class, as well as a copy of the actual

question itself. Students can review their clicker grade performance throughout the semester

on the LMS on a daily basis. If a student misses a particular class meeting or does not answer

a clicker question (see Exhibit 3) during a class session, most clicker systems record the

student as AB, or absent.4

The advantages to the instructor and the university of using clicker technology include:

� Green benefits (no paper is required to administer classroom quizzes);� Time savings (the instructor or the instructor’s grader can save time compared to manually

grading and posting quiz grades); and� Increased posting accuracy (there is improvement in the accuracy of recorded student grades

on quizzes, especially compared to manually grading and recording quizzes in a

gradebook).5

Student Attitudes toward Using Clickers in the Classroom

Various surveys and research studies performed over the past 20 years have found both

strengths and weaknesses regarding student attitudes toward using clickers in the classroom.

EXHIBIT 2Illustration of the Instructor Module (Left) and the Student Clicker (Right)

4 The authors acknowledge there is a wide variety range of features and functionality in clicker product solutionsavailable today in the marketplace from various suppliers. The clicker solution utilized in this study from i .Clicker is regarded in the industry as a low-end, low-cost system with somewhat limited features andfunctionality. Other clicker solutions provided by other suppliers provide the instructor with other features andfunctionality, including (1) minute-by-minute tracking of respondent feedback during an event or presentation;(2) spatial or location-based types of questions (in addition to the usage of standard, multiple-choice types ofquestions); (3) team scoring on a real-time basis; and (4) many other additional features. In fact, i . Clicker hasintroduced, since the completion of this study, i . Clicker 2 in June 2011, which includes additional entry types,such as: True/False; Yes/No; Text Entry; Fill in the Blank; Rankings; Short Answers of up to 15 Characters; andMultiple Correct Responses.

5 These advantages were observed by the authors in their use of clickers during this study.

706 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

In general, research shows students enjoy using clickers in the classroom because it makes the

instructor’s lecture both fun and interesting (Conoley et al. 2006; Duncan 2006; Stuart et al. 2004).

At the same time, research shows that students are able to improve their understanding of both the

related course content and the instructor’s course expectations when using clickers in the classroom

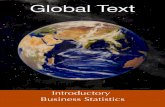

EXHIBIT 3Example Financial Accounting Clicker Question and Graphical Classroom Question Results

Displayed to Students

Panel A: Example Financial Accounting Clicker Question

Panel B: Graphical Classroom Question Results Displayed to Students

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 707

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

(Zhu 2007; Tomorrow’s Professor Blog 2006). Students also are more likely to respond to

instructor questions and participate in classroom discussion when clickers are used (Greer and

Heaney 2004; Hoffman and Goodwin 2006). In general, clickers have been shown to facilitate and

enhance a student’s learning experience in a variety of college subjects, ranging from the sciences

(including physics, chemistry, and geology) (Fies and Marshall 2006) to business (including

accounting) (Edmonds and Edmonds 2008), history, mathematics, psychology, sociology, and

journalism (Conoley et al. 2006; Uhari et al. 2003). Other studies show changes in classroom

dynamics result from the use of clickers, including higher rates of student class attendance, less

sleeping in class, and greater student involvement in classroom activities, especially if the clicker-

posed questions were stimulating (Keller 2007).

On the other side, negative complaints about the clicker from students include the clicker cost

(Greer and Heaney 2004), the occasional encountering of technical problems with the clicker

during classroom usage (Zhu 2007), more noise in the classroom (as students converse when

questions are being presented by the instructor in the process of using clicker technology) (Keller

2007), and use of the clicker ‘‘ruining’’ the flow of a particular traditional lecture (Zhu 2007).

Students also disliked clickers if the instructor required and used clickers in the classroom solely to

take attendance or to record their answers on questions posed during class without any

corresponding grade credit (Zhu 2007).

Studies Related to Effects of Clickers on Measures of Student Learning in Business Courses,

Including Accounting

Bryant and Hunton (2000) appealed to researchers to investigate the pedagogical benefits of

using technology to deliver instruction in the accounting classroom. Since then, several studies

using a variety of research techniques, including survey and archival data, have attempted to

address the effects of clickers on student learning in accounting courses. Carnaghan and Webb

(2007) studied student self-reported perceptions of the learning effects of clickers, including using

and not using clickers in four different introductory management accounting courses during various

parts of one semester, and found clickers helped students learn the material. In addition, the

summarized class answers, in the form of histogram charts presented by the instructor in class after

each clicker question was posed by the instructor, helped students in the Carnaghan and Webb

(2007) study track their personal progress in the course. Finally, the response to clicker questions in

the Carnaghan and Webb (2007) study related to learned behaviors showed students felt clickers

encouraged them to work hard as well as to come prepared for class.

Carnaghan and Webb (2007) also tested objective measures of the learning effects of using

clickers. As a proxy, they used the performance on exam questions in a limited regression model

and found mixed results. Within the course itself, Carnaghan and Webb (2007) found an overall

improvement in exam performance on course concepts covered with clicker questions in class,

especially for high ability students (those with high GPAs entering the class). However, when they

used a repeated-measures ANOVA to analyze their data, with clicker usage as the within-subjects

factor and with ability and order of usage as the between-subject factors, Carnaghan and Webb

(2007) found improvement in student performance was limited to exam questions that were similar

to those questions employed when using the clicker only.

Similarly, Cummings and Hsu (2007) find clicker usage in the tax accounting course improves

student exam scores only where the underlying tax concepts are both taught and discussed

specifically by the instructor in class using the clicker. Our study is a more stringent test of the

pedagogical effects of clicker usage in the accounting classroom compared to such prior research,

and does not include the use of clicker questions that are purposely similar, in any significant

708 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

manner or to any significant degree, to the examination questions given to students during the

introductory financial accounting course.

Cunningham (2008) reports on the use of action research, including the use of a clicker, to

align an instructor’s classroom activities or strategies with course goals in an elementary accounting

course taught to (primarily) sophomore students (similar to this study). Despite the fact that this

study encountered technological problems with the clicker (problems that the current study did not

encounter), overall, the course evaluations and questionnaire comments indicated students believed

clickers enhanced the classroom environment, helped maintain student interest and focus, and

provided immediate feedback both to the students and the professor.

Edmonds and Edmonds (2008), in a highly controlled experiment performed similar to the

current study on courses including introductory managerial accounting students, found that students

in the courses using clickers outperformed students in the courses not using clickers after

controlling for age, gender, prior GPA, and ACT scores.

A more recent study by Chan and Snavely (2009) in the finance classroom found students were

satisfied with using clickers and believed using clickers helped improve their examination

performance. However, using various multivariate models and controlling for other confounding

factors, Chan and Snavely (2009) found no difference in student examination performance between

students using and not using clickers in the classroom.

To our knowledge, no such study comparing students’ examination performance in classes

using and not using clickers in a highly controlled experiment, including controlling for other

confounding factors, has been performed in the introductory financial accounting course, a void this

study will help fill.

Theoretical Rationale for ARS Effects on Student Learning and Related Hypotheses

The ‘‘Conversational Framework,’’ an influential theory developed originally in 1993 and

upgraded and expanded by Laurillard (2002), envisions the learning process as an iterative dialog

between student and teacher and describes how technology positively affects student learning in

higher education courses. Interactive teaching, using technology products like the ARS used in this

study, also is likely to encourage active learning and, therefore, influence student motivation in the

classroom positively, if used correctly by the teacher. Students’ active engagement in the

classroom, including being engaged with ideas and applications, supports student learning

according to several other studies summarized by Draper et al. (2002). At the same time, Cue

(1998) argues ‘‘timely feedback and reinforcement are vital to the synthesis and integration

process’’ of learning for a student, which is another feature of the ARS.

We hypothesize that the ARS will improve student motivation and, therefore, learning and

overall performance in the introductory financial accounting course for several reasons. First, the

biggest learning gains from using the ARS are likely to come as a result of the quicker student

feedback from the teacher, the method of teaching in which questions are used as part of the

classroom lecture, discussions in class initiated by well-designed questions, and the commitment of

each student to an initial position on each ARS question before receiving the answer to the question

(Draper et al. 2002). Second, although interactive teaching using ARS may not result in an increase

in active student cognitive experiences automatically, students have been found to be engaged more

mentally when involved in the classroom in learning activities such as problem solving (Van Dijk et

al. 2001). Finally, the types of interactive teaching techniques involved when using products like

the ARS generally create an atmosphere where true engagement by students is encouraged and

supported by the teacher (Martin 1999).

To summarize, the appropriate use of ARS in the classroom should improve interaction

between the student and the instructor in the classroom. At the same time, the attempt by students to

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 709

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

solve problems and questions posed by the instructor using the ARS, and the immediate feedback

provided by the instructor in the classroom to such problems and questions, should both enhance

student satisfaction with the course itself and improve student performance in the introductory

financial accounting class. This paper, therefore, tests two hypotheses:

H1: Using clickers increases student satisfaction with an accounting course.

H2: Using clickers improves student performance in the introductory financial accounting

course compared to not using clickers in the same course, assuming all other factors

remain equal.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The controlled experiment of teaching two sections of the introductory financial accounting

course, one with and one without the use of clickers, involved one of the authors over two

different semesters (Spring 2009 and Spring 2010)6 at one university. The introductory financial

accounting course is a required course taken by all students majoring in business; it also is an

elective course for other students attending the university. The course typically is taken during

the student’s sophomore year. The same course textbook,7 syllabi, course schedule, OHMS8

(including use of the same homework questions and problems in the OHMS), instructor lecture

notes prepared by the instructor teaching the course, weekly class meetings and times (Tuesday

and Thursday mornings), and multiple choice examinations (three examinations during the

semester plus one department-wide common comprehensive final examination) were used in both

semesters.9 The only difference between the two classes was that students taking the Spring 2009

course took various unannounced pencil and paper multiple-choice quizzes in class and

submitted various pre-assigned homework assignments during the semester at the request of the

instructor on an unannounced basis, while students taking the Spring 2010 course were quizzed

in class using the clicker as a direct substitute for the aforementioned quizzes and hand-graded

homework assignments.10 The instructor also used the same multiple-choice quiz questions and

homework problems from the Spring 2009 course (translating the homework problem into

clicker-type, multiple-choice questions) when teaching the Spring 2010 course using the

clicker.11

6 Both semesters were equal in length (16-weeks long) and exactly one calendar year apart.7 The course textbook used in both classes was titled Fundamentals of Financial Accounting, 2nd edition, by

Phillips, Libby, and Libby (2008); published by McGraw-Hill Irwin.8 The OHMS used for the classes is the companion online Homework Manager product offered with the above-

mentioned Phillips, Libby, and Libby course textbook by McGraw-Hill Irwin.9 There was no student in the 2010 class who took the same class with the same instructor in 2009. In the 2010

class, there were five students who took the same class with another instructor in 2009. Our results remainunchanged when excluding these five students from our results shown in Tables 1, 3, 4, and 5. Also, studentswere not allowed to retain or obtain copies of either the homework solutions or the course examinations as amatter of departmental policy for their permanent records.

10 Another minor difference was the Spring 2009 class consisted of two class sections meeting in the mornings,back-to-back, with an equal number of students in each class, whereas the Spring 2010 was one class consistingof all the students taking the course with the instructor. As will be seen later, the larger size of the Spring 2010class did not affect the examination performance of students taking the class compared to students in the Spring2009 classes in a smaller class size situation. This is also important to our results in this study as, counter-intuitively, one may believe the larger class size might adversely affect student performance in such a course.

11 The 200 clicker questions used by the instructor in the introductory financial accounting course are available bycontacting the author whose name is listed first on the title page of this article.

710 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

Description of How Clickers Were Used in the Classroom in This Study

During the first week of class, the instructor explained to the students how clickers12 would be

used in the course during the semester. This included:

� How clickers would be incorporated into the classroom lectures;� How much the clicker responses throughout the semester would count toward the student’s

total course grade that semester (the percentage weight toward a student’s final grade for the

class using clickers was the same as for the class not using clickers but having unannounced

quizzes and graded homework assignments); and� Instructions on how both to use the clicker in the classroom and how to register the clicker

online at the supplier’s website.13

A course syllabus and a detailed course schedule were provided to each student on the LMS,

advising them of the materials (consisting of textbook chapter readings and exercises and/or

problems assigned in each chapter) to be read and/or prepared in advance of each class meeting.

The instructor used clickers in the classroom starting the second week of classes and used the

clicker to pose various computational-type problems and theoretical questions to students during

every class meeting for the remainder of the semester, except for the scheduled course examination

dates.

The instructor scattered clicker questions throughout each classroom lecture: some at the

beginning of class, some during class, and some questions at the end of class. The instructor

prepared the clicker questions in Microsoftt Word beforehand. On a random basis, the clicker

questions covered materials from the previous classroom lecture, the present classroom lecture, and

any new materials included in that day’s scheduled classroom lecture or assigned homework

exercises and problems shown on the course schedule. The majority of the clicker questions

consisted of multiple-choice type questions and five different answer choices.

After each clicker question was posed and the polling time period for student answers for the

question was closed, the instructor immediately provided the students with the correct answer to the

question, including a bar graph showing the total performance of the class on that particular

question. When student performance was perceived by the instructor to be low or not acceptable on

a particular question (for example, more than 50 percent of the students selected an incorrect

answer), the instructor discussed the question again in detail with the class. In the case of

computational-related questions, the instructor immediately provided a detailed explanation of the

correct answer in the classroom (the same explanations were provided throughout the semester for

the class not using clickers for the quizzes and homework problems collected in that course). This

form of immediate feedback to students is an important feature of the clicker technology and related

interactive pedagogy. In the case of a question showing poor class results, the instructor also

occasionally presented a similar question ‘‘on the fly,’’ immediately after explaining the correct

answer to the previous question, to retest the comprehension levels of the class on challenging

course-related concepts. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that clicker use has sometimes led to

improved student performance.

12 The instructor and the students used clicker technology supplied by i . Clicker (http://www.iclicker.com).13 It is important to note the majority of students using clickers in the introductory accounting course included in

this study had previous experience with using clickers in some other college-level course at the university. Theinstructor posted instructions on Blackboard on how to use the clicker in class to assist those students with noexperience using clickers in the classroom and to answer any questions students might have on the operation ofthe clicker in the classroom. The combination of having previous experience with the clicker and the instructionsprovided by the instructor on its use leads the authors of this manuscript to believe students knew how to use theclicker correctly in the classroom throughout the semester under study.

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 711

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

Students received credit for each clicker question answered correctly with no credit given for

incorrect answers; for the class not using clickers, the same rules were applied in the case of the

quizzes and graded homework assignments. After class, the instructor downloaded the day’s clicker

results into the LMS.14 Thus, the credit students received for correctly answering the clicker

questions essentially mimics the credit students received in the course not using clickers for correct

answers on the quizzes and the graded homework assignments.

During the last week of the semester in the class using the clicker, the instructor distributed a

one-page survey in the form of a questionnaire consisting of 18 questions, asking students to rate

usage of the clicker during the course on a scale of 1 (1¼ totally disagree) to 5 (5¼ totally agree). In

addition, at the end of the questionnaire there was an open-ended question requesting students to list

any other comments they had regarding the clicker use in the course. The analysis of these survey

results was used to test H1.

In order to test H2, we used a multiple regression model to examine the examination outcomes

from using and not using the clicker technology in the classroom. There were 98 students in the

class using clickers and, coincidentally, there also were 98 students in the class not using clickers.

During the semester, four students dropped (withdrew) from each class; we address this in the

robustness tests section below. Therefore, the final number of students included in both classes in

the regression models is n ¼ 94. The advising office of the School of Business Administration

helped us collect the required student demographic and academic data. We used the LMS to record

student grades in both classes on the course examinations, the OHMS, the clicker grades from each

class meeting for the class using the clickers, and the quiz and homework grades in the course not

using clickers.

Using ordinary least squares (OLS), we use the following multiple regression model to

examine the effectiveness of using clickers in the introductory financial accounting course:

Exam average ¼ k1 þ k2Clicker averageðHW=quiz averageÞ þ k3Semester credit hours

þ k4GPA þ k5Gender þ k6Major þ k7OHMS averageþ e; ð1Þ

where:

Exam average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the four examinations;

Clicker average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the clicker questions;

HW/quiz average ¼ the student’s average percent score on homework and quizzes;

Semester credit hours ¼ the student’s total semester hours enrolled for the semester;

GPA ¼ the student’s GPA as of the semester the student took the course;

Gender¼ a dichotomous variable of 1 if the student is female, 0 otherwise;

Major¼ a dichotomous variable of 0 if the student is a declared business administration major,

1 otherwise;15

OHMS average ¼ the student’s average score on the question and problem sets performed in

the online homework manager system; and

e ¼ the random error term.

14 This consists of downloading the day’s clicker data from the USB drive into a column in the course LMS, aprocedure that takes about one minute for the instructor to perform. It also is free of any clerical or unintentionalerrors that might occur in the case of the manual grading and posting of the results of quizzes or homeworkassignments.

15 At the university where this experiment was performed, students are not required to declare their major formallyuntil completion of a lower core of classes. Until that time, students can make a general declaration of their majorin the university’s advising system, which can include BADM (a business administration major) or otherdisciplines outside of BADM, as well as undeclared.

712 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

Exam average (the average of each student’s three examination scores and the comprehensive

final examination score during the semester) is the dependent variable in each of the regression

models and the measure we use to proxy for student performance in the introductory financial

accounting course, similar to Chan and Snavely (2009). First, we estimate Equation (1) for the class

of n ¼ 94 students using clickers (including the related k2Clicker average variable); then, we

separately estimate Equation (1) for the class of n¼ 94 students not using the clicker (including the

related amount for the k2HW/quiz variable in the model). We expect to find a positive relationship

between the k2 variables in the separate models and the student exam average. Finally, we estimate

Equation (1) in a pooled regression model for both of the classes combined (a total of n ¼ 188

students), including for k2Clicker the average variable for the students using clickers and zero for

the students not using clickers, following Chan and Snavely (2009).

The explanatory variables included in the models are based upon factors previously found to be

associated with student performance in the introductory accounting and other types of business

courses in both clicker-related regression models (Carnaghan and Webb 2007; Cummings and Hsu

2007) and non-clicker related regression models (Beed and Evans 2008). We expect to find a

positive relationship between the GPA and the OHMS independent variables and the dependent

variable, exam average. We expect to find a negative relationship between the Semester credit hours

variable and exam performance. We have no expectations for the signs on the coefficients either for

the Gender or the Major16 control variables.

RESULTS

Students Using Clickers—Survey Results

Table 1 shows the results of the questionnaire distributed to students during the last week of the

semester in the class that used the clicker. Out of 94 students taking the course, 83 (88.3 percent)

voluntarily filled out the questionnaire.

As can be seen in Table 1, the mean response for many of the ‘‘positive’’ survey questions was

in excess of 4 on a scale of 1 to 5. Students felt the clicker questions practiced in class increased

their understanding of the material (mean ¼ 4.40), better prepared them for the exams (mean ¼4.26), and improved their learning experience when they could see the correct answer immediately

after each clicker question was presented in class by the instructor (mean ¼ 4.74). It also is

important to note students said they were more likely to attend class because of the daily use of the

clicker (mean ¼ 4.53). Using the clicker in every class meeting during the semester also helped

students stay more focused during class itself (mean ¼ 4.08). Overall, students believed using a

clicker was very effective in this particular accounting course (introductory financial) (mean ¼4.38).

Student responses to some of the ‘‘negative’’ survey questions showed students disagreed with

whether the clicker actually helped them during the course. Students indicated they did not agree

that they spent less time preparing and studying for this class than usual because of the use of the

clicker (mean ¼ 2.08). Also, students disagreed with the statement their grades were worse than

16 At the university where this experiment was conducted, students are not able to declare their specific major fieldof study until they complete their required lower core of studies (generally two years of general educationrequirements), which includes the introductory financial accounting class (typically taken some time during thesecond year of studies). However, students can declare before completion of their lower core of classes if theirgeneral course of studies will be Business Administration, undeclared (unknown), or a major outside of studiesrelated to the business school. We control for the Major declared or not declared by each student accordingly inour model.

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 713

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

they expected due to use of the clicker (mean¼ 1.93), and that using the clicker every class meeting

took up too much class time (mean ¼ 1.69).

Overall, the survey results indicate students seemed to be satisfied with using a clicker in the

introductory financial accounting course, and also were satisfied with the manner in which the

clicker was used as part of the interactive learning pedagogy utilized by the instructor in teaching

the course, adding to the literature in this area and confirming H1.

Table 2 shows a sample of the student open-ended comments regarding use of the clicker in the

introductory financial accounting course. In general, students supplied the instructor with positive

TABLE 1

Survey of Students Taking the Introductory Financial Accounting Course(n ¼ 83)

Survey Questions Mean Median Std. Dev.

1. The clicker questions practiced in class increased my

understanding of the course material.

4.40 4.00 0.67

2. I believe the use of the clicker increased my learning experience

compared to other classes where my instructor did not use the

clicker.

4.15 4.00 0.90

3. Practicing problems using the clicker in class prepared me better

for the exams.

4.26 4.00 0.90

4. Seeing the correct answer after each clicker question was

important to my learning experience.

4.74 5.00 0.47

5. The clicker questions were too difficult. 2.65 3.00 1.02

6. I believe using the clicker to solve accounting-type problems

every class meeting is important.

3.88 4.00 0.97

7. I was more likely to attend class because of the daily use of the

clicker.

4.53 5.00 0.87

8. I spent less time preparing and studying for this class than usual. 2.08 2.00 1.03

9. I believe my grade was worse than expected due to the use of

the clicker.

1.93 2.00 1.09

10 I was satisfied with the number of clicker questions posed by the

instructor during each class meeting.

3.99 4.00 0.86

11. Using a clicker every class meeting takes up too much class

time.

1.69 1.00 0.91

12. I retained more of the lecture material as a result of using a

clicker.

4.04 4.00 0.82

13. Using a clicker in every class helped me stay more focused

during class.

4.08 4.00 0.91

14. Overall, I believe using a clicker is very effective in this

accounting course.

4.38 5.00 0.77

15. I wish all of my instructors used a clicker to pose questions and

work problems during class.

3.38 3.00 1.24

16. Earning 15% of my grade during the semester using a clicker is

reasonable.

4.24 4.00 0.82

17. I believe the use of the clicker improved my final grade in this

course.

3.86 4.00 1.05

18. The use of the clicker increased my interest in accounting. 3.26 3.00 1.16

Rating Scale: 1¼Totally Disagree; 2¼ Somewhat Disagree; 3¼Neither Agree nor Disagree; 4¼ Somewhat Agree; 5¼Totally Agree.

714 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

written comments about the use of the clicker in this particular course. The positive comments

shown in Table 2 include students believed the clicker helped them in terms of learning and

understanding the course materials and the course examinations in terms of preparation, kept them

engaged in the class lectures, and raised their expectations of the final grade they expected to earn in

the course. It should be noted, however, that some students wrote that the clicker was too expensive

and sometimes they felt rushed when using the clickers to respond to the questions posed by the

instructor in class.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3, Panel A separately shows student performance on each part of the introductory

financial accounting course requirements, including the mean, median, and standard deviation for

each part, for the class using clickers and the class not using clickers. Panel A is broken down

TABLE 2

Representative Sample of Student Open-Ended Comments Regarding Use of the Clicker inthe Introductory Financial Accounting Course

(n ¼ 83)

(Survey Question: Please list any other comments you have regarding clicker use in this classin the space below.)

Student Positive Comments

I used the clicker at the University of Colorado, and I think it is very beneficial to our understanding of the

material.

Once I got used to the speed required in order to answer the questions, I began to like the clicker.

The clicker definitely put my thinking into higher gear and focused my attention more.

I thought the clicker problems were a very effective way of teaching.

Go Clicker!

First time I used clickers; I thought it is a great idea and really think it helps with the exams.

I think you have a good system going. Accounting is very complicated and working through problems can

be very helpful.

I really like the clicker because it helped me learn the material. Doing examples in class with the clicker is

extremely helpful!

I feel I would not have had a chance passing this class without the participation of the clickers.

Clickers were very important and helped my grade in the course.

Clicker is a good way to keep the class engaged in the lecture and inspires us to know the material prior to

class.

Student Comments Containing Some Type of Prefacing WordsSometimes I felt rushed by the clicker.

I do not believe it is necessary every class to use clicker, but using clickers in class is very useful.

Clickers make class somewhat impersonal, as no one can share answers.

Just another expense to an already expensive class.

I like the clicker, but I am slow sometimes and need more time to work out the math in the problems.

Please give us some more time to think. It is too fast.

For the longer problems or questions using clickers, sometimes I felt rushed.

I think you go too fast on some clicker questions. Otherwise, high five!

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 715

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

TABLE 3

Descriptive Statistics-Student Performance in IntroductoryFinancial Accounting Course

Panel A: Student Performance on Each Section of the Course Requirements in theIntroductory Financial Accounting Courses

PointsPotential Course Requirement

Using Clickers(n ¼ 94)

Not Using Clickers(n ¼ 94)

p-valueaMean Median Std. Dev. Mean Median Std. Dev.

100 Exam 1 74.04 78 14.16 72.20 74.5 12.06 0.152

100 Exam 2 68.64 72 16.00 68.70 69.5 15.10 0.500

100 Exam 3 69.51 72 17.77 66.60 70 20.69 0.143

100 Final Exam 73.23 77 16.73 68.10 71 20.54 0.032

40 Group Project 38.71 40 7.07 38.80 40 10.37 0.482

65 HW Manager 49.29 52.3 11.35 46.60 48.62 11.17 0.046

95 Clickers vs. Quizzes

and Graded Homework

85.51 86.5 16.82 79.60 80 17.65 0.009

600 Total 458.93 467.5 80.67 440.60 447.87 89.56 0.062

Panel B: Analysis of Student Grade Performance in the Introductory Financial AccountingCourses

Number of StudentsAchieving a Grade of: Clicker Used Percent Clicker Not Used Percent

A 13 0.138 10 0.106

B 27 0.287 20 0.213

C 30 0.319 35 0.372

Subtotal 70 0.745 65 0.691

D 20 0.213 17 0.181

F 4 0.043 12 0.128

Subtotal 24 0.255 29 0.309

Total Number of Students 94 1.000 94 1.000

Class Course Grade Point Average 2.30 2.01

p-valueb 0.05

HW manager is the online homework manager product included as part of the course textbook.Quizzes are multiple-choice quizzes given and graded by instructor in course not using clickers, and graded homework istextbook homework due for each class meeting, collected and graded at random by the instructor.For Grade Point Average calculations: A ¼ 90% and above; B ¼ 80–89.9%; C ¼ 73–79.9%; D ¼ 60–72.9%; and F ¼below 60%.a One-tailed t-test of mean differences between the classes using and not using clickers.b One-tailed t-test of mean difference in grade point average between the classes using and not using clickers.

716 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

further for each class into student performance on (1) Exams 1, 2, and 3, separately; (2) the

cumulative final examination; (3) the group financial analysis project;17 (4) the web-based online

homework manager assignments (OHMS); and (5) for the clickers (for the class using clickers)

versus the quizzes and graded homework (for the class not using clickers). The last column of Panel

A shows one-tailed, p-values of a t-test for the difference in the means between the two classes for

each course requirement. The number of students completing each course was n ¼ 94.18

As can be seen in Panel A, students in the course using clickers significantly outperformed

students in the course not using clickers on the course comprehensive final examination (p¼ 0.032,

one-tailed), on the web-based OHMS assignments (p¼0.046), and on the performance comparison

between the clicker grade for the entire semester for the class using clickers and the quizzes/graded

homework assignments for the class not using clickers (p¼ 0.009). Consequently, there also was a

significant difference between the two classes on the total points earned, on average, by all students

taking the two courses (p ¼ 0.062).

Table 3, Panel B shows an analysis of the overall class student average in the two introductory

financial accounting classes. Importantly, the overall class GPA in the class using the clicker was

significantly higher (p¼ 0.05, one-tailed) than the class not using the clicker. Also, fewer students

in the clicker class (24) received a failing grade (D or F) in the course compared to the class not

using the clicker (29).19

Table 4, Panels A and B, provides the descriptive summary statistics for the continuous and

dichotomous variables used in Equation (1). The statistics in both panels are partitioned between the

class using clickers and the class not using clickers, with the t-statistics for equal means shown for

the continuous variables and z-statistics for equal proportions provided for the dichotomous

variables. In general, Panels A and B show there are no statistically significant differences between

the two groups of students in the number of semester credit hours being taken, GPA, Gender, and

Major, which potentially could bias the results we obtain in the pooled regression model.

Testing the Validity of the Regression Models

The variance inflation factors (VIF) for all of the variables used in Equation (1) in each of the

models are all less than five, suggesting multicollinearity is not a problem. As a rule of thumb, a

variable whose VIF factor is greater than ten merits further investigation for multicollinearity (Hair

et al. 2006). In addition, the degree of collinearity, measured by determining the tolerance for all

variables in our models (defined as 1/VIF), is generally greater than 0.1, which is comparable to a

variable inflation factor of less than ten. In general, our results suggest multicollinearity is not a

serious problem that might affect the coefficients and standard errors obtained using OLS to

estimate Equation (1) in each of our models.

In addition, we find that levels of kurtosis (the average is less than four) and skewness (the

average is less than one) for each of the variables included in each of the models do not violate the

17 In both classes, the group project requirement was performing a vertical and horizontal financial analysis andvarious ratio analyses of the most recent financial statements of Home Depot, including answering somequestions in writing regarding the results of this financial analysis. Up to five students per group completed thegroup project, which the instructor graded manually during the last week of the semester when the project wasdue. We did not include the scores earned by students in the group project as a control variable in our Equation(1), as the group project was performed by students at the end of the semester, based upon course materials thatwere covered by the instructor in the later portion of the course and that were not tested in detail on any of thecourse examinations.

18 Two students withdrew from each of the two classes during the respective semesters, and none of these fourstudents completed any of the course requirements before withdrawing.

19 The instructor did not implement a curve on any portions of the course requirements, including on any of thecourse examinations, in either class.

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 717

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

normality assumptions important to the results obtained in OLS (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007).

Finally, in our pooled regression model, we find the Durbin-Watson statistic to be 1.94, indicating

that correlated residuals are not present in our data (Ott and Longnecker 2010).

Regression Results

The second and third columns of Table 5 show the regression model results for the class using

clickers. The overall model is significant (F-statistic ¼ 10.34, p-value , 0.0001, n¼ 94), and the

adjusted R-squared for the model is approximately 42 percent. The coefficient on Clicker average is

both positive and significant (p-value¼0.015), indicating the clicker average earned by students on

TABLE 4

Descriptive Summary StatisticsRegression Model Variables

Panel A: Continuous Variables

Variables

Using Clickers(n ¼ 94)

Not Using Clickers(n ¼ 94)

t-testaMean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

Clicker average 90.01 17.80 — — —

HW/quiz average — — 83.79 20.49 —

Semester credit hours 14.41 3.19 13.57 3.85 0.90

GPA 2.85 0.59 2.72 0.83 0.67

OHMS average 75.83 17.56 71.69 18.72 1.77

Exam average 71.36 14.75 68.90 16.44 1.45

Panel B: Dichotomous Variables

Variables

Using Clickers(n ¼ 94)

Not Using Clickers(n ¼ 94)

z-testbMean Std. Dev Mean Std. Dev

Gender 0.64 0.48 0.62 0.49 0.33

Proportion female ¼ 1, 0 otherwise

Major 0.41 0.49 0.45 0.50 �0.48

Proportion business administration major

¼ 1, 0 otherwise

a t-test is t-statistic for equal means comparing class using clickers and class not using clickers.b z-test is z-statistic for equal proportions comparing class using clickers and class not using clickers.

Variable Definitions:Clicker average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the clicker questions posed by instructor;HW/quiz average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the homework problems and multiple-choice quizzes;Semester credit hours ¼ the number of credit hours the student is registered for in the semester when taking the

introductory financial accounting course;GPA¼ the student’s grade point average as of the semester the student takes the introductory financial accounting course;OHMS average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the question and problem sets performed in the online

homework manager system;Exam average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the four examinations including the final exam;Gender¼ 1 for female, 0 otherwise; andMajor ¼ 1 for a declared business administration major, 0 otherwise.

718 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

questions posed by the instructor in the clicker class significantly contributes to their average

examination score for the four examinations students took during the course. The control variables

Gender (p-value ¼ 0.006) and OHMS average (p-value ¼ 0.001) also contribute positively and

significantly to student performance on the course examinations. The number of Semester credit

hours taken by a student and the student’s Major are not significantly associated with the student’s

exam performance in the class using the clicker. A student’s GPA contributes positively and

marginally (p-value ¼ 0.120) to a student’s examination performance during the course using

clickers.

The fourth and fifth columns of Table 5 show the OLS results for Equation (1) applied to the

class not using clickers. Again, the overall model is significant, and the adjusted R-squared in this

model not using clickers improves to almost 68 percent. Both the HW/quiz average and the OHMS

average (both p-values¼ 0.0000) contribute significantly, as expected, to the student’s examination

performance in the class not using clickers. This association between students doing their

homework, being prepared for class, and course performance is not surprising, as prior literature has

TABLE 5

Regression Model Results in the Introductory Financial Accounting Course

Variable

Using Clickers Not Using Clickers Pooled Regression

EstimatedCoefficient

t-testp-valuea

EstimatedCoefficient

t-testp-valuea

EstimatedCoefficient

t-testp-valuea

Intercept 19.483 0.009 5.919 0.132 9.303 0.026

Clicker average 0.226 0.015 — — 0.248 0.000

HW/quiz average — 0.336 0.000 0.261 ,0.0001

Semester credit hours �0.293 0.242 0.433 0.071 0.029 0.452

GPA 2.909 0.120 �0.149 0.461 4.395 0.006

Gender 6.967 0.006 4.450 0.018 5.698 0.000

Major �0.140 0.478 �0.041 0.492 0.076 0.485

OHMS average 0.303 0.001 0.369 0.000 0.303 ,0.0001

Adjusted R2 (%) 41.908 47.596 56.480

F-statistic 10.34 ,0.0001 30.25 ,0.0001 33.18 ,0.0001

n 94 94 188

Exam average ¼ k1 þ k2Clicker averageðHW=quiz averageÞ þ k3Semester credit hoursþ k4GPAþ k5Gender

þ k6Major þ k7OHMS averageþ ea p-values are one-tailed.

Variable Definitions:Exam average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the four examinations including the final exam;Clicker average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the clicker questions posed by instructor. In the pooled

regression model, Clicker average is the student’s percent score in the class using clickers, and for the class notusing clickers, the student’s Clicker average is zero;

HW/quiz average¼ the student’s average percent score on the homework and quizzes. In the pooled regression model,HW/quiz average is the student’s percent score on the homework and quizzes in the class not using clickers, and forthe class using clickers, the student’s HW/quiz average is zero;

Semester credit hours ¼ the number of credit hours the student is registered for in the semester student takes theintroductory financial accounting course;

GPA¼ the student’s grade point average as of the semester the student takes the introductory financial accounting course;Gender ¼ 1 for female, 0 otherwise;Major ¼ 1 for a declared business administration major, 0 otherwise; andOHMS average ¼ the student’s average percent score on the question and problem sets performed in the online

homework manager system.

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 719

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

consistently concluded that students diligently performing their accounting-related homework

assignments improve their grade performance in the related accounting course (Beed and Evans

2008; Rayburn and Rayburn 1999).

The last two columns of Table 5 show the pooled regression results for Equation (1),

combining the data for the class using clickers and the class not using clickers. The Clicker average

variable for the class not using clickers is entered as zero in the pooled regression; the HW/quiz

average variable for the class using clickers also is entered as zero in the pooled regression model.

The pooled regression model is statistically significant (F-statistic¼33.18, p-value , 0.0001, n

¼ 188), and the independent variables in the model explain approximately 56 percent of the

variation in the dependent variable, examination performance. The Clicker average variable again

positively and significantly (p-value ¼ 0.000) contributes to the student’s average examination

performance in the introductory financial accounting course. The HW/quiz average and the OHMS

average also significantly contribute, as expected, to the student’s examination performance in the

pooled regression model. The GPA and Gender control variables also positively and significantly

contribute to exam performance in this pooled regression model.

The results in Table 5 suggest using the clicker in the classroom enhances the student’s

performance in the introductory financial accounting course, proxied for in this study by a student’s

average examination performance throughout the entire semester the course is taught.

Robustness Tests

Four students withdrew during various parts of the semester from both the class using clickers

and from the class not using clickers. Chan, Shum, and Lai (1996) show a potential impact of

survival bias on the results of regression models like Equation (1) due to students withdrawing from

the course. Following Chan et al. (1996), we used TOBIT estimation to mitigate the potential

survival bias in Equation (1) of the four students in the class using clickers, the class not using

clickers, and the eight students combined in the pooled regression model, using their control

variable information to estimate the students’ exam averages had they finished the respective

courses. We then reran Equation (1) for the class using clickers, the class not using clickers, and the

pooled regression, and our results (not presented in the interest of parsimony) previously shown in

Table 5 basically remained unchanged.

Two students in both the classes using and not using the clicker registered for the courses but

did not complete any of the course requirements. We again used TOBIT estimation and included

the results of these students as if they had completed the course requirements and reran each of our

models shown in Table 5; our results remained essentially unchanged when including these students

in our models. We also used TOBIT estimation and included both the aforementioned four students

withdrawing and the two students not completing the course using and not using the clicker, and

again our results shown in Table 5 remained essentially unchanged.

Similar to Chan and Snavely (2009), we reran the pooled regression model, substituting a

dichotomous variable named Clicker (1 for students in the class using clickers, 0 otherwise) for the

Clicker average independent variable.20 This is a simple test of whether the use of the clicker itself

significantly contributes to student exam performance in the introductory financial accounting

course. Our results (not presented in the interest of parsimony) shown in the last two columns of

Table 5 basically remain unchanged, except the Clicker variable is significant only at the 10 percent

level (p ¼ 0.099, one-tailed) instead of at the approximately 1.5 percent level shown in the third

column of Table 5 when including the Clicker average continuous variable as the independent

20 We also enter at the same time the variable HW/quiz average in this test as zero for the students in the class usingclickers, and maintain the original HW/quiz average for the students in the class not using clickers.

720 Premuroso, Tong, and Beed

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

variable. This result provides some evidence that it is not merely the use of the clicker that

contributes to student exam performance, but how the clicker is used by the instructor and the

resulting average obtained by the student on their clicker grade throughout the course that

contribute to student examination performance in the introductory financial accounting course. We

will comment on this result in the conclusion section.

CONCLUSIONS, LIMITATIONS, AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Conclusions

The use of ARS, including clickers, continues to expand in classrooms across the nation,

including their use in the introductory accounting courses required in most business-related and

accounting major programs. Educators, deans, administrators, and Offices of Student Retention on

university and college campuses are continuously looking for new classroom technologies that

allow for the consideration of enlarging class sizes without compromising the quality and the

pedagogy of these required accounting courses in the curriculum. The intent of this research is to

inform the decision makers of those constituencies considering the use of clicker technology in the

introductory accounting course classroom. Our results suggest that using clickers in the classroom

matters not only to student satisfaction, but also matters to student performance in the introductory

financial accounting course, a required course in the business curriculum that is challenging for

many students in both content and pedagogy. It is important in an increasingly competitive

environment to both obtain and retain higher enrollments in the face-to-face classroom, and the use

of clickers can potentially assist in attaining these important higher education goals.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Consistent with prior research, the average responses to our survey questions in the

introductory financial accounting course using the clicker suggest strong student satisfaction with

the use of this technology in the classroom. We acknowledge that the results we found in our survey

of students using the clicker have limitations—we expressly asked students to answer the questions

on the survey honestly. However, demand effects, including students believing a positive response

to the survey questions was the required or desired response, are possible, although as explained in

the results section, student responses to the ‘‘negative survey’’ questions do not indicate a significant

demand effect bias in the survey results. Also, though most of the students in the class using

clickers responded voluntarily to the survey, non-response bias may exist due to the 11 students

(out of the 94 students taking the course) who were absent the day the survey was administered in

the classroom.

Another limitation of our study is determining the exact impact the use of the clicker has on

student performance without, at the same time, employing the OHMS feature included in most

introductory accounting courses. At the same time, it is possible the pedagogical approach we used

in this study for the questions posed to students in the class using the clicker (both the degree of

difficulty and the instructor’s participation in the administration of the clicker questions) may

unduly influence (either positively, like it did in the case of our study, or negatively) student

performance on the examinations in such a course. Additionally, at what point the number of

students in one introductory accounting course classroom, as well as the different types of ARS

available in the marketplace, impacts both student satisfaction and performance in such a course is

an open question.

Finally, it is possible certain characteristics of both the instructor using the clicker (such as

years of teaching experience in the introductory financial accounting course, for example) as well as

differing levels of clicker question difficulty may influence the performance, one way or the other,

Does Using Clickers in the Classroom Matter to Student Performance and Satisfaction? 721

Issues in Accounting EducationVolume 26, No. 4, 2011

of students in these types of courses. There are many other additional and important outcome

variables, for example, measuring a student’s interest in accounting or measuring a student’s self-

perceived changes in learning or learning attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs from using a clicker in

the classroom, that could be measured. Additionally, it is possible that student examination

performance is impacted more or less positively by clicker usage in the classroom with respect to

certain aspects of the different types of materials covered in the introductory financial accounting

course (i.e., the quantitative aspects versus the conceptual aspects of accounting). We leave it to

future research to answer these questions before reaching additional conclusions on the effects of

the use of clickers in accounting education.

REFERENCES

Beed, T. K., and J. Evans. 2008. Does homework really affect accounting grades? Available at: http://

cengagesites.com/academic/assets/sites/3309_BEED_homeworkstudy.doc

Berry, P. 2009. The Effect of the Introduction of a New Technology to an Introductory Accounting Course.

Working paper, Commerce Department, Mount Allison University.

Bryant, S. M., and J. E. Hunton. 2000. The use of technology in the delivery of instruction: Implications for

accounting educators and education researchers. Issues in Accounting Education 15 (1): 129–163.

Carnaghan, C., and A. Webb. 2007. Investigating the effects of group response systems on student

satisfaction, learning and engagement in accounting education. Issues in Accounting Education 22

(3): 391–409.

Chan, K. C., C. Shum, and P. Lai. 1996. An empirical study of cooperative instructional environment on

student achievement in principles of finance. Journal of Financial Education 22 (Fall): 21–28.

Chan, K. C., and J. C. Snavely. 2009. Do clickers ‘‘click’’ in the finance classroom? Journal of FinancialEducation 35 (Fall): 25–40.