Interpreting an Early Classic Pecked Cross in the Candelaria Caves, Guatemala: Archaeological and...

Transcript of Interpreting an Early Classic Pecked Cross in the Candelaria Caves, Guatemala: Archaeological and...

Interpreting an Early Classic Pecked

Cross in the Candelaria Caves,

Guatemala: Archaeological and

Indigenous Perspectives

Brent Woodfill

Institute for Advanced Study at the University of Minnesota

Pecked crosses, a variant of a common Prehispanic American symbol often

referred to as a ‘‘quartered’’ or ‘‘quadripartite’’ circle, are commonly found in

central and northern Mexico during the florescence of Teotihuacan (ca. A.D.

100–650) and often interpreted as astronomical devices. The subject of this

article is a pecked cross found in the Candelaria Caves, Guatemala, one of

four examples that have been found to date in the Maya world. The author

interprets the symbol through two distinct lenses—first as an archaeologist

and then through its cosmological significance according to contemporary

Q’eqchi’ Maya daykeepers. Although the methodologies and approaches

differ, there is common ground between them—both point to the symbol’s

associations with ritual events, directionality, and the passage of time.

keywords Maya, Mesoamerica, ritual, Q’eqchi’, Maya religion, archaeoastron-

omy

Introduction

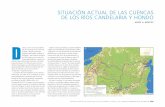

Located at the highland–lowland frontier in central Guatemala, the Candelaria

Caves (Figure 1) form the second largest cave system in Central America. First

brought to international attention in the 1970s (Dreux 1974), they have been host

to two separate archaeological reconnaissances (Carot 1976, 1989; Pope and

Sibberenson 1981) and one multi-year investigation conducted by the author

between 2000 and 2006 (Woodfill 2010; Woodfill and Andrieu 2012; Woodfill

and Monterroso 2007; Woodfill et al. 2004). A variety of evidence was

recovered—walls, platforms, caches, and large quantities of broken vessels,

human bones, and obsidian blades—all related to Precolumbian ritual activity.

Most of this ritual occurred during the latter part of the Early Classic period (ca.

ethnoarchaeology, Vol. 6 No. 2, October, 2014, 103–120

� W. S. Maney & Son Ltd 2014 DOI 10.1179/1944289014Z.00000000019

A.D. 460–550), although limited ritual activity dates to the Late Preclassic (ca. 250

B.C.–A.D. 250) and Late Classic (ca. A.D. 600–900) periods.

One of the most intriguing archaeological features documented by Patricia

Carot (1976, 1989) in her initial investigation of the Candelaria Caves was a cross-

and-circle motif that was pecked directly into the bedrock of one of the river caves

(Figure 2). While the meaning of this symbol has been long debated (e.g., Astor

Aguilera 2012; Aveni 1989, 2000; Aveni and Hartung 1986; Aveni et al. 1978;

Coggins 1980; Ruggles and Saunders 1984), most of the recorded examples are

found at and around Teotihuacan (at least 44 have been found within the site

borders alone) during the Early Classic period (A.D. 250–600), so Aveni et al.

(1978) posited a connection with this Mexican metropolis. They continue to be

rare outside of highland Mexico, with the total known corpus in the Maya world

consisting of this example (Carot 1976, 1989) and three from Uaxactun (Aveni

et al. 1978, Smith 1950).1

Unfortunately, Carot was never able to fully document the pecked cross,

although she did photograph it and note its approximate location on her map of

the Candelaria system. Park guards relocated it in late 2011 and the author

documented the cross in April 2012 with a team composed of an archaeology

student from Guatemala and seven cavers. Two Q’eqchi’ elders from the region

accompanied the team along with several local tour guides and park guards, all of

whom are active participants in village ritual. This article stems from a

conversation that occurred between the two parties while standing above the

pecked cross, in which it was discussed both for its importance as an

archaeological feature and as a central symbol for contemporary Maya religion.

Description of the Candelaria pecked cross

The pecked cross is located in the El Mico cave in the central part of the

Candelaria system, carved into the bedrock well above the flood line of the

Candelaria River in the twilight zone of the cave, between the river and a large

sinkhole. While ambient light does enter to the pecked cross and beyond, only a

1 Wanyerka (1999) identified a potential pecked cross in Stann Creek, Belize, although it might be more properly

called a ‘‘pecked asterisk.’’

figure 1 Map of the Candelaria Caves. The location of the pecked cross is indicated with an

arrow (drawing by Carlos Efraın Tox Tiul).

104 BRENT WOODFILL

cliff face on the opposite side of the sinkhole is visible, completely obscuring a view

of the sky. The cross is oriented 27u west of magnetic north and composed of 26

holes forming a cross inside a circle with a diameter of 46 cm.

The pecked cross is located in an area with ambient light that streams in from a

nearby sinkhole. The only two ways of accessing the part of the cave where the

pecked cross was found are by swimming through the cave or entering by foot

through a second, higher entrance and passing through the sinkhole and its dense

garden. The latter path was blocked by a series of walls at some point in the

history of use of the cave (Figure 3).

While pecked crosses have been traditionally dated to the Early Classic period,

the ceramics located nearby all date to the Late Classic period. Late Classic

ceramics are rare in the Candelaria Caves (Woodfill 2010), and the absence of

Early Classic material is unusual, although ample material from the earlier time

period was recovered closer to the cave entrance and the sinkhole. At present, it is

impossible to say with certainty that this cross was created in the Early Classic

period, but it is most likely for the following reasons.

figure 2 Photograph of the

pecked cross, with the

sinkhole entrance in the

background (photo by Matt

Oliphant).

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 105

1. The other known pecked crosses date to this period throughout

Mesoamerica, as does all of the ‘‘international’’ (Teotihuacan and central

Peten) symbolism in the Candelaria Caves (Woodfill 2010) and over 90% ofthe ritual evidence recovered there.

2. Late Classic ritual in caves throughout the region was mostly restricted to

high natural stages where status-reinforcing ritual could have been

conducted in front of an audience (Woodfill 2010), making this out-of-the-way location not only anachronistic but counter-productive to the

principal goals of ritual activity during this later period.

3. Finally, since the pecked cross was first identified in the 1970s, after the

region had been largely abandoned for over a millennium, it is unlikely to befrom a later time. As such, it will be assumed to be an Early Classic feature.

Other pecked crosses in Mesoamerica

Anthony Aveni et al. (1978:275–8), in their synthesis of pecked cross features inMesoamerica, note seven particular patterns, which I summarize and compare

with the present example below.

1. Form: Pecked crosses tend to consist of two concentric circles around a

simple cross form with a mean diameter of just under a meter. This pecked

cross is smaller than average, with a diameter of 46 cm. It also consists of a

single circle surrounding the cross.

2. Setting: Like the present example, most pecked crosses were inscribed

directly onto bedrock; the rest were on floors of buildings.

3. Execution: While three incised circle-and-cross shapes were catalogued byAveni (1978), each of the true pecked crosses was created with a percussive

device and consists of holes averaging 1 cm in diameter and separated by 2

cm spaces. The holes tend to be conical in shape, like the present example.

4. Orientation of the axes: Most of the pecked crosses seemed to have beenintentionally oriented towards important architecture or astronomical

events. Since the sky is not visible from this example, however, it is unlikely

figure 3 Caver Nancy Pistole

examines walls that blocked

access to the cave interior

near the entrance of this

section of Cueva El Mico

(photo by Matt Oliphant).

106 BRENT WOODFILL

to have been oriented towards any particular celestial body, and the team

could find no obvious correlation with any parts of the cave.

5. Relationship with other crosses: Many of the crosses at Teotihuacan seemed

to be oriented in relationship with each other, potentially serving to delimitsurveys or astronomical events. This example, in contrast, is located about

250 km away from its nearest known kin, making it highly improbable that

it was created in relation to any other examples.

6. Numerology: The number of dots seems to be significant in most cases.

Many are composed of approximately 260 dots, for example, which is theday count in the Mesoamerican divinatory calendar. The calendar is

composed of 20 nawales (spirits associated with specific days) who each

have 13 aspects. Since this example has 26 dots, it is possible to argue that itis tied to the number 13 (half of 26) or 260 (the number of days in the Maya

ceremonial calendar).

7. Skew: Previously recorded examples were often skewed clockwise from

north, apparently either correlated with the Teotihuacan grid (15–17

degrees) or the rising and setting points of the solstice suns in northernMexico (24–26 degrees), with the three examples from Uaxactun falling

just outside of the range of the former category (17.5 degrees). The presentexample, in contrast, is skewed 27 degrees counter-clockwise. It does not

seem to be oriented towards anything within the cave—the entrance would

have been located off-center in its northwest quadrant and the section of theriver accessible from this cave passage would have been contained within its

northeastern quadrant.

As is apparent, this pecked cross does differ from the norm in several respects, but

still fits comfortably within the existing paradigm.

The pecked cross and interregional exchange

Previous research in the Candelaria Caves and other nearby shrines (Woodfill2010; Woodfill and Andrieu 2012; Woodfill et al. 2012) has shown that much of

the ritual activity performed during the Early Classic period was related to

merchants and travelers along the Great Western Trade Route (Figure 4; Adams1978; Arnauld 1990; Demarest 2006; Demarest and Fahsen 2002; Hammond

1972; Seler 1993; Woodfill 2010; Woodfill and Andrieu 2012; Woodfill et al.2012) who moved between the highlands and lowlands to acquire and trade avariety of raw materials and finished products. The ritual paraphernalia left behind

was ‘‘international,’’ with styles that borrowed from the central Peten, the

Guatemalan highlands, and even central Mexico and were otherwise absent locally(Figure 5e, Woodfill 2010). The pecked cross is one such link to the Mexican

metropolis of Teotihuacan, along with a Tlaloc (highland Mexican rain god) face

from a broken bowl (Figure 5d), several Mexican style warriors on stelae in TresIslas (Figure 5f), and multiple slab-footed tripod cylindrical vessels (Figure 5a–c,

Woodfill 2010; Woodfill and Andrieu 2012).

As one of the principal trade routes connecting the Guatemalan highlands and

lowlands, the Pasion River and the land route immediately to its south would have

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 107

figure 4 Map of the Maya world showing the location of the Great Western Trade Route and

the sites discussed in this text (drawing modified by the author from the original by Luıs

Luin).

108 BRENT WOODFILL

been heavily trafficked by merchants and travelers throughout the Preclassic and

Classic periods. Since Teotihuacan-style material in the Maya world is typically

filtered through Tikal and its allies in the Early Classic (Braswell 2003), it is more

likely that this demonstrates links not with the distant Mexican city but with the

central Peten, where there was a high demand for goods such as jade, obsidian,

quetzal feathers, and iron pyrite that traveled through the Candelaria region

(Andrieu and Forne 2010; Arnauld 1990; Demarest 2006; Demarest et al. 2008;

Fahsen et al. 2004; Hammond 1972; Woodfill 2010; Woodfill and Andrieu 2012).

Any identifiable links with the central Peten stop around the end of the Early

Classic period (ca. A.D. 550) and ritual activity in the Candelaria Caves and other

shrines in the region became greatly diminished just as Cancuen was founded (ca.

figure 5 ‘‘International’’ styles present in the Candelaria Caves and the surrounding region.

a–c) central Peten-style slab-footed cylindrical tripod vessels (drawings by Luis Luin), d)

appliqued polychrome Tlaloc mask (drawing by Walter Burgos), e) Serpent Head X motif on a

Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome vessel (drawing by Walter Burgos), f) Tres Islas Stela 2

depicting a warrior in Teotihuacano garb (drawing by Luis Luin).

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 109

A.D. 630). Since this city was initially established to control trade along the route

and quickly began importing raw highland materials (Andrieu and Forne 2010;

Barrientos and Demarest 2000; Demarest 2006; Demarest et al. 2008), processing

them, and exporting them further into the lowlands, it appears that much of the

long-distance travel along this route was cut in half. As a result, the ritual

importance of the Candelaria Caves and other shrines diminished, and the limited

ritual activity in the region’s shrines would have been conducted principally by

locals for sporadic ceremonies more focused on reinforcing elite status (Woodfill

2010).

There are several areas throughout the region in which the Early Classic ritual

remains were so spectacular or special that they became the focus of Late Classic

ritual, however. The most dramatic of these is probably the nearby cave shrine of

Hun Nal Ye (Woodfill 2010; Woodfill et al. 2012), in which six whole vessels and

a carved stone coffer were left in a niche and on the floor below it. During the Late

Classic, at least one major ritual event occurred in front of them—two whole

vessels of a local style (one containing part of a juvenile pelvis) were cached in a

hole in front of the earlier offerings. They were then covered by a mixture of

smashed vessels and burnt organics. It is probable that the pecked cross similarly

‘‘marked’’ this cave section, since the ledge nearby is the only context where Late

Classic material has been recovered in this part of the system.

Caves and crosses

The location of the pecked cross is unique—it is one of just four examples that

have been identified in the Maya world and the only one found inside a cave. Aveni

et al. (1978:276) did posit a link between caves and pecked crosses, however,

noting that many of the Mexican examples were located close to caves.

The symbol of the cross itself has strong associations with caves throughout the

Maya world, most notably demonstrated through a cross-shaped artificial cave in

Esquipulas, Guatemala (Brady and Veni 1992), carved crosses on artificial cave

walls underneath the Postclassic city of Q’umarkaj, Guatemala (Woodfill 2014),

and crosses that have been erected in front of caves in the Yucatan (Astor Aguilera

2012) and Chiapas (Vogt 1969). Quatrefoils, ‘‘four-leafed’’ patterns similar to the

circle-and-cross motif, are often used in Classic period iconography to represent

portals to the underworld (Astor Aguilera 2012; Bassie-Sweet 1991; Stone 1995;

Stuart 1995) and are associated with the place of ‘‘emergence and submergence of

the sun’’ (Astor Aguilera 2012:229) into and out of caves. With all of this in mind,

it is surprising that this is the only identified example of a cross-and-circle motif

from caves in the Maya world.

Archaeological sites and caves as contemporary sacred space

While archaeological investigations by this and other projects in the region are

(and will continue to be) focused on recovering data on the ancient Maya who

lived and died here, life on-site is more complicated. Beginning in the 1960s,

Q’eqchi’ Maya from the Coban area began their second great migration down into

110 BRENT WOODFILL

the lowlands (Demarest and Woodfill 2011; Sapper 1985; Wilson 1995), and by

the 1990s much of the land had been converted to horticultural plots managed by

residents of hundreds of small villages. Although missionaries and, until recently,

the Guatemalan government have been trying to stamp down contemporary Maya

ritual (Demarest and Woodfill 2011), it lives on—villagers conduct rituals before

every planting, harvest, construction, or life-changing event such as marriage,

divorce, death, birth, or sickness. Like their ancestors, the villagers conduct these

rituals in the most sacred spaces—hills, caves, and archaeological sites (Adams and

Brady 2005; Demarest and Woodfill 2011; Garcıa 2003, 2007; Maxwell and

Garcıa Ixmata 2008; Scott 2009; Wilson 1995).

In 1998, the Guatemalan government created a Commission for the Definition

of Sacred Sites and the Guatemalan congress has passed several agreements

allowing indigenous populations to control places they deem ritually important.

As a result of this and similar developments throughout the Maya world, there is a

growing movement among Mayanists to establish partnerships and engage in

dialogue with the local communities (e.g., Ardren 2002; Demarest and Barrientos

2004; Fruhsorge 2007; Ishihara et al. 2008; McAnany and Parks 2012; Mortensen

2009; Parks et al. 2006; Pyburn and Wilk 1995; Woodfill 2013). This has led to

new challenges and opportunities for contemporary projects. Archaeological site

management is no longer simply based on concerns for the artifacts, features, and

ecology, but also often requires coming to an agreement over which areas are to be

set aside for local ritual activities. This has led to collaborations between

archaeologists and Maya spiritual leaders that would have been very difficult even

15 years ago.

A contemporary Q’eqchi’ ritual

One such situation that would have been unlikely in the past occurred within

several hours of having left the Candelaria Caves. The archaeological and

speleological team found themselves climbing a small mountain above the town of

Fray Bartolome de las Casas to engage in a mayejak (literally ‘‘offering’’) led by

Qawa’ (‘‘Don’’) Tomas Mez, a local Q’eqchi’ daykeeper. The mayejak is the

principal Q’eqchi’ ritual, performed before any major undertaking (planting,

harvesting, traveling, new construction, etc.) or during any life crisis (sickness,

divorce, personal attacks, a string of bad luck, etc.). What follows is a description

of that particular ceremony, although when necessary, references will be made to

other ceremonies observed by the author. The interpretations of and rationales for

specific parts of the ceremony are syntheses of conversations the author has had

with multiple Q’eqchi’ ritual specialists.

Maya religion—both ancient and modern—is based on the idea of a covenant

with the supernatural beings (saints, spirits, and divinities, including Qawa’ Dios,

the Christian god) upon whom we depend for sustenance, fortune, and continued

existence (Adams and Brady 2005; Demarest and Woodfill 2011; Fischer 2001;

McAnany 1995; Maxwell and Garcıa Ixmata 2008; Scott 2009; Vogt 1976;

Wilson 1995). A variety of offerings typically including sugar, incense, chocolate,

multi-colored candles, rosemary, alcohol, a chicken, cologne, and cigars, are

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 111

placed in a comal (clay pan for cooking tortillas and toasting spices) or, ideally,

directly upon the earth in a slight depression that serves as an altar. These are then

burnt, causing a sort of transubstantiation—the conversion of the offerings to

smoke allows them to be consumed by the supernaturals to whom they are being

offered. Each of the materials offered have all been previously smudged with a

chocolate drink, alcohol, incense smoke, and chicken blood in a separate ceremony

called a wa’atesink (Figure 6, which literally means ‘‘feeding’’) and prayed over

during several days leading up to the event.

As the sacred flame grows and gains strength, the daykeeper calls out to multiple

tzuultaqas (‘‘hill-valleys’’), supernatural owners of specific pieces of land in order

to honor them and ask for their protection. All of the participants in the ceremony

face each of the four cardinal directions in turn, praying and kissing the earth. As

the fire continues to burn, each of the 13 avatars of the 20 nawales (spirits

associated with specific days with specific powers and characteristics) are called

and petitions are made to each one, beginning with the nawal of the present day.

On the day Kan (snake), for example, the 13 avatars of Kan are chanted in order

(Jun [One] Kan, Wiib’ [Two] Kan, etc., up to Oxlaaju’ [Thirteen] Kan). Prayers

specifically dedicated to Kan are then made before moving on to the 13 avatars

associated with the following day, Keme’ (Death). Additional offerings are thrown

in when a new nawal is called in order to keep the flame burning and further

ingratiate the spirits to the petitioner.

The flame serves two functions according to the daykeepers—it is a vehicle to

bring the offerings to the spirits and a tool for prognostication and interpretation.

Daykeepers read it for positive or negative signs—an ideal flame signifying

acceptance by the nawal burns bright and tall, spins in a counter-clockwise manner

(following the perceived path of the sun [Astor Aguilera 2012]), and does not favor

any particular direction. Sometimes the daykeepers give the nawales a little

‘‘push,’’ spinning counter-clockwise around the fire, kicking up the flame with a

wooden pole, or adding dollops of highly flammable alcohol or cologne. If the

flame moves towards a specific direction, that is also taken into account—each of

figure 6 Wa’atesink

blessing of the offerings,

which include balls and

wrapped packages of

incense, bottles of hard

liquor, and candles wrapped

in paper to be used in a

mayejak (photo by the

author)

112 BRENT WOODFILL

the four cardinal points has a specific set of associations (money, guilt, etc.) andeach of the 20 nawales (also associated with specific traits) are visualized in a ring

around the altar. Once the ritual is over and the flame dies, the daykeeper can see

how much of the offering is left, which also speaks to the rite’s success. An idealceremony will leave nothing but ash and resin, while an offering that is not

completely accepted will still have large chunks of unbroken or unburnt materials.

The setup for the ceremony began when Qawa’ Tomas cut a cross-and-circleshape through the burnt remains from a previous ceremony with a sharpened stick

(one never uses metal on the altar), first making the cross pattern before carving a

counter-clockwise swirl around it. This same shape was then repeated on multipleoccasions throughout the preparations. The first offering to be deposited was sugar

(Figure 7), arranged in a circle-and-cross pattern with each spoke of the crossaimed towards one of the cardinal directions. Incense balls were placed atop the

sugar in the same pattern, as were the candles and sticks of ocote (resinous slivers

of pine), which were the last objects to be added. Near the conclusion of theceremony, Qawa’ Tomas cut the cross into the offering again in order to break up

some of the chunks that had been resistant to burning, and finally each of the

figure 7 The sugar at the

base of the mayejak offering

in the form of a circle-and-

cross with incense balls in the

center and the four cardinal

points. Elders in the upper

left are unwrapping other

offerings to be used in the

ceremony (photo by Matt

Oliphant)

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 113

principal participants in the ceremony circled the fire in a clockwise direction three

times, cutting circles through the remains in order to signify the completion of the

ceremony.

The repeated cross-and-circle pattern was intentionally likened to the four

cardinal directions and the center throughout the ceremony, both literally through

the orientation of the cross and the prayers to the cardinal directions, and

symbolically, as the candles that were placed in the offering were organized

according to the colors of each direction—white for north, black for west, yellow

for south, red for east, and blue and green for the sky above and earth below the

center. The cross-and-circle patterns in this and other contemporary Maya

ceremonies consist of a single circle, unlike the typical pecked crosses ringed by

concentric circles that were common to the Early Classic period.

The meaning of the pecked cross

The pecked cross from the Candelaria Caves represents one of only four that have

been discovered in the Maya world. It can be understood as having multivalent

importance, both through its relation to larger patterns of interregional trade and

through intergenerational patterns and symbolism that span at least 1500 years. It

does, in fact, appear to be a summarizing symbol as defined by Ortner

(1973:1344): ‘‘Summarizing symbols are primarily objects of attention and

cultural respect: they synthesize or ‘collapse’ complex experience, and relate the

respondent to the grounds of the system as a whole. They include most

importantly sacred symbols in the traditional sense.’’

As a central, key symbol, the cross has multiple meanings and readings, but

what stands out when engaging with both a typically scientific approach based on

interregional and ethnohistoric comparisons, and an ethnographically-informed

interpretive framework based on identification by ritual specialists and associa-

tions with contemporary symbols, is the overlap between the interpretations

reached by both methods.

Archaeological interpretations of the pecked crossIn various publications, Aveni and his collaborators have suggested multiple

meanings and functions for pecked crosses. Aveni et al. (1978) suggested that the

crosses served as a record of the 260-day ceremonial calendar (following Smith

[1950:21], who referred to them as ‘‘calendar circles’’), orientational devices

(either related to parts of the site or celestial bodies), or as games. Ruggles and

Saunders (1984) suggested that many of the pecked crosses served as ‘‘bench-

marks’’ or surveying markers at Teotihuacan and elsewhere. The game hypothesis

has been largely unexplored. Aveni and Hartung (1986:38) discounted it in the

1980s, although Aveni has picked it up again (Aveni 2005).2 Most of Aveni’s later

work, however, has focused on the symbol’s potential as a calendric device (Aveni

2 Barbara Voorhies (2013) recently documented game boards in Mesoamerica that consist of similar, cup-shaped holes

in the floor. The games were played with tokens and a simple die (neither of which were found in the cave), and they

were mostly restricted to oval- or arc-shaped patterns unlike the circle-and-cross present here.

114 BRENT WOODFILL

1989, 2000, 2005), although he does argue that ‘‘no single hypothesis fits all of the

data’’ (Aveni 2000:255).

The Candelaria example goes against the grain for the majority of Aveni’s

suggestions. The spokes of the cross do not seem to point to any natural feature in

the cave and there is no associated architecture. While it is found within the

twilight zone of the cave, there is no view of the sky, rendering it unlikely that

there was a celestial association, and due to the difficulty of access to the part of

the cave in which the pecked cross is found, it seems like a rather inconvenient

location to play a board game. The calendric function thus appears to be the most

likely of Aveni’s suggestions.

Contemporary Q’eqchi’ interpretations of the pecked crossThis potential calendric function was echoed by the Q’eqchi’ ritual specialists who

accompanied the archaeologists and cavers on the reconnaissance trip. For them,

the pecked cross serves both as a ceremonial calendar related to the observance of

an important ritual event and as a cosmogram representing the world and

emphasizing the cardinal directions and the center. Francisco Tiul suggested that

the 26 pecked holes that compose the cross represent the 13 days before and 13

days after performing a mayejak, which must be marked with prayer and penance

in order for the ceremony to be successful. A second, less likely calendric

interpretation proffered by the Q’eqchi’ elders was that the 26 dots stand for the

whole 260 day ritual calendar. However, since the Precolumbian Maya used a

base-20 system instead of the Western base-10, this might reflect modern bias and

not the intention of the original creator of the feature.

The second interpretation suggested by Q’eqchi’ elder Andres Cho was that the

cross is a representation of the world itself, depicting the four cardinal directions

and the center. The counter-clockwise motion used in drawing the circle echoes the

Maya belief that the sun rotates in a counter-clockwise motion (Astor Aguilera

2012). The sunwise motion is the fundamental significance of the repetition of the

cross-and-circle in the set-up of the modern ritual offerings observed by the author.

A number of archaeologists have noted that a quadripartite circle does represent

the world center in Maya iconography (e.g., Astor Aguilera 2012; Headrick 2004;

Reilly 1994) and that caves themselves can serve as cosmograms (Moyes 2000), so

it seems natural to find this symbol here. The ubiquity of the cross-and-circle in

Maya religion could also explain the Candelaria example’s variance from the

canonical double circle, making this a uniquely Maya variant of a Mexican

symbol.

As a symbol of the world and the four directions, it is largely irrelevant whether

or not the four spokes line up with cardinal points, although as Brady and Veni

(1992) have shown, the ancient Maya did have the ability to do rather complex

surveying. This move from the literal to the symbolic was seen in the mayejak

performed that night—Qawa’ Tomas, instead of bringing a compass or studying

the stars simply conferred with several other ritual practitioners in order to anchor

his cross-and-circle to what was determined by consensus to be north. Even with

large-scale public works, the ancient Maya sometimes abandoned actual function

and directionality in favor of symbolic function. E-Groups, for example, began as

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 115

ways of marking the solstices and equinoxes that defined the passage of the year.

By the Classic period, however, they were not actually linked to the astronomical

events but existed principally as monumental reminders of the importance of the

elites and their connections to broader forces in the universe (Doyle 2012).

Conclusions

While it is dangerous to assume that the meaning of symbols remains static from

person to person, much less over a time span of 1500 years (Anderson 1991;

Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983), the concurrence of a calendric interpretation

reached through both hypothesis-driven and interpretive approaches makes such a

meaning tempting to assign. If this is indeed an Early Classic pecked cross and not

an imitation from a later date, it was obviously important to subsequent

generations of Maya, since people continued to be drawn to the part of the cave

where it was found over the next several hundred years. Such reuse of ‘‘marked’’

sacred space has been found in a variety of other ceremonial contexts in the region,

most notably at the aforementioned Cave of Hun Nal Ye (Woodfill 2010; Woodfill

et al. 2012).

While this pecked cross can be understood as a fundamentally Mexican symbol

representing some degree of ties with Teotihuacan, it can also be readily

understood in a specifically Maya cultural milieu, in that the cross was modified

from the original, concentric circles-and-cross form to represent a more Maya

cultural expression. This fits with other examples of foreign art and symbolism

adopted by the Maya world throughout history, from Early Classic Teotihuacan-

style atlatl and war-serpent headdresses (Schele and Freidel 1990; Taube 1992) to

the Terminal Classic Mexican rain god Tlaloc (Maldonado and Repetto Tio 1988)

and the fineware ceramics of the southern Gulf Coast (Bishop 2008). The

Hapsburg eagle still figures prominently on many Maya textiles, prompting one

Kaqchikel Maya academic (Otzoy 1996:144) to note: ‘‘it is probable that the motif

was adopted by the Maya precisely because it fit in with an already existing system

of Maya metaphors and that it is continually reinterpreted in a manner consistent

with Maya philosophy and experiences.’’ Even the standard offerings in the

ceremony described above included ladino-made liquor and perfumes as well

rosemary, a Mediterranean herb.

The Candelaria pecked cross is a powerful, enduring symbol that combines both

Maya and non-Maya traditions, and as a result can be used to understand a variety

of issues of interest to archaeologists, from interregional trade and Mexican–Maya

interaction to worldview and the ritual calendar. In this sense, then, the Candelaria

pecked cross is fundamentally another example of the flexibility of Maya

symbolism at the same time that it demonstrates the durability of the Maya

cosmovision.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken through grants provided by the Alphawood

Foundation and InHerit at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill with

116 BRENT WOODFILL

permissions granted to the Cancuen and Salinas de los Nueve Cerrosarchaeological projects by the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture and Sports,

General Direction of Natural and Cultural Patrimony, and the Department of

Prehispanic and Colonial Monuments. I’d like to thank Patricia Carot, who sharedher knowledge and documentation of the pecked cross with me and the Candelaria

Caves National Park guards who rediscovered the pecked cross after two years ofsearching for it, Santiago Chub Ical, David Caal Rax, Mauricio Cu, and Miguel

Caal Quib. I was accompanied by a large group of people who helped document

the archaeological remains and their context: Karen Mansilla, Andres Choc,Francisco Tiul, Eduardo Asij Xol, Bonifacio Asij Choc, David Caal Rax, Miguel

Caal Quib, John Wyeth, David Marin Roma, Antonio Trapaga, Juan Ernesto

Vossberg, with special thanks to Matt Oliphant, Charley Savvas, and NancyPistole.

My understanding of the mayejak and aspects of Maya religion discussed in this

paper have come out of several years of conversations with Q’eqchi’ daykeepers,particularly Qawa’ Mario Caal and Qawa’ Tomas Mez, and the elders Qawa’

Francisco Tiul and Qawa’ Andres Choc. Qawa’ Tomas also served as fact-checker

for the description and interpretation of the rituals discussed. Glenn Skoy, ArthurDemarest, Carlos Rene Paniagua Morales, Kristin Landau, and Annabeth

Headrick helped me to obtain several of the publications I cite. Anthony Aveni,

Arthur Demarest, Patricia McAnany, Kristin Landau, the editors ofEthnoarchaeology, and anonymous reviewers all gave valuable critiques during

the writing process and guided me towards several works that I would never have

discovered on my own.

References cited

Adams, Abigail and James Brady. 2005. Ethnographic notes on Maya Q’eqchi’ cave rites: Implications for

archaeological interpretation. In In the maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican ritual cave use, ed. James

Brady and Keith Prufer, 301–327. Austin: University of Texas Press, Austin.

Adams, Richard. 1978. Routes of communication in Mesoamerica: The Northern Guatemalan Highlands and

the Peten. In Mesoamerican communication routes and cultural contacts, ed. Thomas Lee and Carlos

Navarette, 27–36. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation No. 40. Provo: Brigham Young

University Press.

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined communities. New York: Verso.

Andrieu, Chloe and Melanie Forne. 2010. Produccion y distribucion del jade en el Mundo Maya: talleres,

fuentes y rutas del intercambio en su contexto interregional: vista desde Cancuen. In XXIV Simposio

deiInvestigaciones arqueologicas en Guatemala, 2009, eds. Barbara Arroyo, Adriana Linares Palma, and

Lorena Paiz Aragon, 947–956. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueologia e Etnologıa.

Ardren, Traci. 2002. Conversations about the production of archaeological knowledge and community

museums at Chunchucmil and Kochol, Yucatan, Mexico. World Archaeology 34(2):379–400.

Arnauld, Marie Charlotte. 1990. El comercio clasico de obsidiana, rutas entre Tierras Altas y Tierras Bajas en

el area Maya. Latin American Antiquity 1(4):347–367.

Astor Aguilera, Miguel. 2012. The Maya world of communicating objects: Quadripartite crosses, trees, and

stones. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Aveni, Anthony. 1989. Pecked cross petroglyphs at Xihuingo. Archaeoastronomy 14:S74–S115.

——. 2000. Out of Teotihuacan: Origins of the celestial canon in Mesoamerica. In Mesoamerica’s classic

heritage, eds. David Carrasco, Lindsay Jones, and Scott Sessions, 253–268. Boulder: University of Colorado

Press.

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 117

——. 2005. Observations on the pecked designs and other figures carved on the south platform of the Pyramid

of the Sun at Teotihuacan. Journal for the History of Astronomy 36(1):31–48.

Aveni, Anthony and Horst Hartung. 1986. The cross petroglyph: an ancient Mesoamerican astronomical and

calendrical symbol. Indiana 6:37–54.

Aveni, Anthony, Horst Hartung, and Beth Buckingham. 1978. The pecked cross symbol in ancient

Mesoamerica. Science 202:267–279.

Barrientos, Tomas and Arthur Demarest. 2000. Resdescubriendo Cancuen: nuevos datos sobre un sitio

fronterizo entre las Tierras Bajas y el Altiplano maya. Paper presented at the XIV Simposio de

Investigaciones Arqueologicas en Guatemala, Guatemala City.

Bassie-Sweet, Karen. 1991. From the mouth of the dark cave: Commemorative sculpture of the Late Classic

Maya. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Bishop, Ronald. 2008. Archaeological ceramics and scientific practice. In VII Congreso Iberico de

Arqueometrıa, eds. Salvador Rovira Llorens, Manuel Garcıa-Heras, Marc Gener Moret, and Ignacio

Montero Ruiz, 236–49. Madrid: Quadras.

Brady, James and George Veni. 1992. Man-made and pseudo-karst caves: The implications of subsurface

features within Maya centers. Geoarchaeology 7(2):149–167.

Braswell, George, ed. 2003. The Maya and Teotihuacan, reinterpreting Early Classic interaction. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Carot, Patricia. 1976. Etude comparee des grottes de Candelaria, Julik et Bombil Pec. Spelunca 3

(suplemento):25–31.

——. 1989. Arqueologıa de las cuevas del norte de Alta Verapaz. Cuadernos de Estudios Guatemaltecos I.

Mexico City: Centre d’Etudes Mexicaines et Centramericaines.

Coggins, Clemency. 1980. The shape of time: political implications of a four-part figure. American Antiquity

45(4):727–739.

Demarest, Arthur. 2006. The Petexbatun regional archaeological project: A multidisciplinary study of the

Maya collapse. Vanderbilt Institute of Mesoamerican Archaeology Vol. 1. Nashville: Vanderbilt University

Press.

Demarest, Arthur and Tomas Barrientos. 2004. Los proyectos de arqueologıa y de desarrollo comunitario en

Cancuen: Metas, resultados y desafıos en 2003. In VII Simposio de investigaciones arqueologicas en

Guatemala, 2003, eds. Juan Pedro Laporte, Barbara Arroyo, Hector Escobedo, and Hector Mejıa, 450–

464. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueologıa y Etnologıa.

Demarest, Arthur and Federico Fahsen. 2002. Nuevos datos e interpretaciones de los reinos occidentals del

Clasico Tardıo: Hacia una vision sintetica de la historia Pasion-Usumacinta. Paper presented at the XVI

Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueologicas en Guatemala, Guatemala City.

Demarest, Arthur and Brent Woodfill. 2011. Sympathetic ethnocentrism and the autorepression of Q’eqchi’

Maya culture. In The ethics of anthropology and Amerindian research: Reporting on environmental

degradation and warfare, eds. Richard Chacon and Ruben Mendoza, 117–146. Berlin: Springer Press.

Demarest, Arthur, Brent Woodfill, Marc Wolf, Tomas Barrientos, Ronald Bishop, Mirza Monterroso, Edy

Barrios, Claudia Quintanilla, and Matilde Ivec. 2008. De la selva hacia la sierra: Investigaciones a lo largo

de las rutas riberenas y terrestres del Occidente. In XXI Simposio de investigaciones arqueologicas en

Guatemala, eds. Juan Pedro Laporte, Barbara Arroyo, Hector Mejıa, 179–194. Guatemala City Museo

Nacional de Arqueologıa y Etnologıa, Guatemala City.

Doyle, James. 2012. Las plazas preclasicas del registro del tiempo: Reconsiderando los complejos de

conmemoracion astronomica. Paper presented at the XXVI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueologicas en

Guatemala. Guatemala City, July 20.

Dreux, Daniel, 1974. Recherches en Alta Verapaz (1968–1974). Paris: CERSMT.

Fahsen, Federico, Tomas Barrientos, and Arthur Demarest. 2004. Taj Chan Ahk y el apogee de Cancuen.

Paper presented at the XVIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueologicas en Guatemala, Guatemala City.

Fischer, Edward. 2001. Cultural logics and global economies: Maya identity in thought and practice. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Fruhsorge, Lars. 2007. Archaeological heritage in Guatemala: Indigenous perspectives on the ruins of Iximche.

Archaeologies 3:39–58.

118 BRENT WOODFILL

Garcıa, David. 2003. Vınculus espirituales y religion alrededor de Cancuen. In XVI Simposio de

investigaciones arqueologicas en Guatemala, 2002, eds. Juan Pedro Laporte, Barbara Arroyo, Hector

Escobedo, and Hector Mejıa, 10–15. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueologıa y Etnologıa.

Garcıa, David. 2007. Territorio y espiritualidad: Lugares sagrados q’eqchi’es en Chisec. In Mayanizacion y

vida cotidiana: La ideologıa multicultural en la sociedad guatemalteca. Vol. 2, ed. Santiago Bastos and Aura

Cumes. Guatemala City: FLACSO/CIRMA.

Headrick, Annabeth. 2004. The quadripartite motif and the centralization of power. In K’axob: Ritual, work

and family in an ancient Maya village, ed. Patricia McAnany, 367–378. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute.

Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Ishihara, Reiko, Marvin Coc, Patricia McAnany, Shoshi Parks, and Satoru Murata. 2008. The Maya area

cultural heritage initiative (MACHI) in Belize: Bridging the past and the present through a public education

program in the Toledo District, Belize. In Archaeological investigations in the eastern Maya lowlands:

Papers of the 2007 Belize archaeology symposium, ed. John Michael Morris, 307–313. Belmopan: Institute

of Archaeology.

Hammond, Norman. 1972. Obsidian trade in the Mayan area. Science 178:1092–1093.

McAnany, Patricia. 1995. Living with the ancestors: Kinship and kingship in ancient Maya society. Austin:

University of Texas Press.

McAnany, Patricia, and Shoshaunna Parks. 2012. Casualties of heritage distancing: Children, Ch’orti’

indigeneity, and the Copan archaeoscape. Current Anthropology 53(1):80–107.

Maldonado, Ruben, and Beatriz Repetto Tio. 1988. Los ‘‘Tlalocs’’ de Uxmal, Yucatan. Revista Espanola de

Antropologıa Americana no. XVIII:9–19.

Maxwell, Judith, and Ajpub’ Pablo Garcıa Ixmata. 2008. Power in places: Investigating the sacred landscape

of Iximche’, Guatemala. Submitted to the the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies,

Inc. http://www.famsi.org/reports/06104/, accessed on December 12, 2013.

Mortensen, Lena. 2009. Copan past and present: Maya archaeological tourism and the Ch’orti’ in Honduras.

In: The Ch’orti’ Maya area: Past and present, eds. Brent Metz, Cameron McNeil, and Kerry Hull, 246–257.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Moyes, Holley. 2000. The cave as a cosmogram: Function and meaning of Maya speleothem use. In: The

sacred and the profane: Architecture and identity in the Maya lowlands, Acta Mesoamericana, Vol. 10, eds.

Pierre R. Colas, Kai Delvendahl, Marcus Kuhnert, and Annette Schubart, 137–148. Gotingen, Germany:

Verlag Anton Saurwein.

Ortner, Sherry. 1973. On key symbols. American Anthropologist 75(5):1338–1346.

Otzoy, Irma. 1996. Maya clothing and identity. In: Maya cultural activism in Guatemala, eds. Edward Fischer

and R. McKenna Brown, 141–155. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Parks, Shoshaunna, Patricia McAnany, and Satoru Murata. 2006. The conservation of Maya cultural heritage:

Searching for solutions in a troubled region. Journal of Field Archaeology 31(4):435–432.

Pope, Keven and Malcolm Sibberenson. 1981. In search of Tzultacaj: cave explorations in the Maya lowlands

of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Journal of New World Archaeology 4(3):16–54.

Pyburn, K. Anne, and Richard Wilk. 1995. Responsible archaeology is applied anthropology. In Ethics in

American archaeology: Challenges for the 1990s, eds. Mark Lynott and Alison Wylie, 71–76. Lawrence,

Kansas: Allen Press.

Reilly, F. Kent. 1994. Visions to another world: Art, shamanism, and political power in Middle Formative

Mesoamerica. Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Ruggles, Clive, and Nicholas Saunders. 1984. The interpretation of the pecked cross symbols at Teotihuacan:

A methodological note. Journal for the History of Astronomy, Archaeoastronomy Supplement 15(7):101–

110.

Sapper, Karl. 1985. The Verapaz in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: A contribution to the historical

geography and ethnography of northeastern Guatemala., trans. T. Gutman. Occasional Paper 13. Los

Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles Institute of Archaeology.

Schele, Linda, and David Freidel. 1990. A forest of kings: Untold stories of the ancient Maya. New York:

William Morrow.

CANDELARIA CAVES, GUATEMALA 119

Scott, Ann. 2009. Communicating with the sacred earthscape. Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Seler, Eduard. 1993. On the origin of some forms of Quiche and Cakchiquel myths. In Collected works in

Mesoamerican linguistics and archaeology, Volume IV, eds. J. Eric S. Thompson and Francis Richardson,

323–325. Culver City, California: Labyrinthos, Culver City.

Smith, A. L. 1950. Uaxactun, Guatemala: excavations of 1931–37. Carnegie Institution of Washington

Publication 588. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Stone, Andrea. 1995. Images from the underworld: Naj Tunich and the tradition of Maya cave painting.

Austin: University of Texas Press.

Stuart, David. 1995. Kings of stone: A consideration of stelae in ancient Maya ritual and representation. Res:

Anthropology and Aesthetics 19/20:149–172.

Taube, Karl. 1992. The temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred warfare at Teotihuacan. Res:

Anthropology and Aesthetics 21:53–87.

Vogt, Evon. 1969. Zinacantan: A Maya community in the highlands of Chiapas. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

——. 1976. Tortillas for the gods: A symbolic analysis of Zinacantan ritual. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press.

Voorhies, Barbara. 2013. The deep prehistory of Indian gaming: Possible late Archaic Period game boards at

the Tlacuachero Shellmound, Chiapas, Mexico. Latin American Antiquity 24(1):98–115.

Wanyerka, Phil. 1999. Pecked cross and patolli petroglyphs of the Lagarto Ruins, Stann Creek District, Belize.

Mexicon 21:108–111.

Wilson, Richard. 1995. Maya resurgence in Guatemala: Q’eqchi’ experiences. Norman: University of

Oklahoma Press.

Woodfill, Brent. 2010. Ritual and trade in the Pasion-Verapaz region, Guatemala. Vanderbilt Institute of

Mesoamerican Archaeology, vol. 6. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

——. 2013. Community development and collaboration at Salinas de los Nueve Cerros, Guatemala:

Accomplishments, failures, and lessons learned conducting publically-engaged archaeology. Advances in

Archaeological Practice 1(2):105–20.

——. 2014. Three newly-discovered cave features in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Mexicon

36(4):114–120.

Woodfill, Brent, and Chloe Andrieu. 2012. Tikal’s Early Classic domination of the Great Western Trade

Route: Ceramic, lithic, and iconographic evidence. Ancient Mesoamerica 23(2):189–209.

Woodfill, Brent, Stanley Guenter, and Mirza Monterroso. 2012. Changing patterns in ritual activity in an

unlooted cave in central Guatemala. Latin American Antiquity 23(1):93–119.

Woodfill, Brent, and Mirza Monterroso. 2007. Investigaciones espeleologicas en las Cuevas de Candelaria,

Temporadas 2004 y 2005. In Proyectoa arqueologico Cancuen informe final no. 6, eds. Arthur Demarest,

Tomas Barrientos, Brent Woodfill, Claudia Quintanilla, and Luis Luin, 697–724. Nashville: Department of

Anthroplogy, Vanderbilt University.

Woodfill, Brent, Alvaro Ramırez, Emilia Gazzuolo, Mirza Monterroso, Adriana Segura, Carlos Giron, Jose

Hurtado, Nicolas Miller, and Paul Halacy. 2004. Descripcion y registro de cuevas, rasgos, y artefactos

culturales en las cuevas de Candelaria. In Proyecto arqueologico Cancuen informe final no. 5, eds. Arthur

Demarest, Tomas Barrientos, Brigitte Kovacevich, Michael Callaghan, Brent Woodfill, and Luis Luin, 633–

678. Nashville: Department of Anthropology, Vanderbilt University.

Notes on contributor

Correspondence to: [email protected] z502.4919.0640 2716 Flag Ave N

New Hope, MN 55427

120 BRENT WOODFILL