In the Realm of the Incas: An Archaeological Exploration of Household Exchange, Long-Distance Trade...

Transcript of In the Realm of the Incas: An Archaeological Exploration of Household Exchange, Long-Distance Trade...

321

P

if i have learned something as an economic anthropologist with sympathies toward his-tory and archaeology, it is that markets are very unstable and that they originate, rise, grow, reach their zenith, and fall. and their demise, in the longue durée, is entirely predictable. (Mayer, this volume)

In the preceding chapter, my colleague and friend enrique Mayer offers a commen-

tary on the intellectual history of the anti-market position in the pre-hispanic andes as advocated by John Murra, and Mayer provides his own pro-posal for a more nuanced position on this issue. i believe that he is correct when he suggests that part of the attraction of Murra’s position was the anti-market bias of many anthropologists and archae-ologists, including myself, who were sympathetic to the critiques of american market expansion and global imperialism in the late 1960s and 1970s. of course, today the pendulum has swung to the right, and we must be careful not to let the widespread

admiration of the market system unduly color our interpretations of the ancient andes.

My purpose in this chapter is to briefly explore some of the archaeological implications of Mayer’s analysis and discussion. at the core of his com-mentary is that the anti-market position found in Murra’s late writings is both oversimplified and unrealistic. There probably was always some market activity, even during inca times, though not nec-essarily in formal marketplaces. This is a position foreshadowed in the writings of Patterson (1988, 1991), salomon (1977, 1986), and rostworowski (1970, 1975), but unlike these authors, Mayer does not focus on the northern frontier of the empire or the special case of the chincha Valley; instead, he is concerned with everyday life in tawantinsuyu, the core of the inca empire,. For Mayer and me, the real question is the nature, not the existence, of markets in the ancient central andes. There must have been major changes in the kinds of goods exchanged, the direction of these exchanges, the actors involved, and the intensity and scale of these transactions.

13

In the Realm of the IncasAn Archaeological Reconsideration of Household Exchange,

Long-Distance Trade and Marketplaces in the Pre-Hispanic Central Andes

r i c h a r d l . b u r g e r

322 Burger

Moreover, even if John Murra was correct that between the late fifteenth and early sixteenth cen-tury, market activity was of relatively little signifi-cance in the political economy of tawantinsuyu (Murra 1995), localized exchange for subsistence goods almost certainly continued to occur between households or villages, coexisting—as it does in modern times—with other kinds of transactions and economic relationships.

Perhaps what is most important, for those in -vestigating andean prehistory, is realizing that the situation in the 1530s, as observed by the spaniards, was not the inevitable culmination of socioeco-nomic evolution in the andean world, but rather a historically specific moment in which a unique social formation, the inca state, seized the produc-tion and distribution of prestige goods as part of a strategy of imperial power. in doing so, the state suppressed market activity by circumscribing the goods that could be exchanged. eliminating the most valuable goods from the equation greatly constrained the potential for market activity. nonetheless, archaeologists have demonstrated that the scale and bureaucratic organization of tawantinsuyu had no equivalent among earlier pre-hispanic states, and, thus, there is no reason to assume that we can use the role of the market in the inca empire as a guide to visualizing mar-ket activity among its predecessors—particularly those in the culturally diverse regions that the inca conquered. Just as Josef stalin sought to suppress market activity in soviet union during the 1920s and 1930s, and Pol Pot tried to extinguish it in cambodia in the 1970s—only for market exchange to return with force to russia and cambodia in the twenty-first century—so there exists a complex and nonlinear history for markets and exchange in the Pre-columbian andes of Peru.

to illustrate this line of reasoning, i will briefly touch upon some of the archaeological evi-dence relevant to the history of exchange and mar-kets in the callejón de huaylas and callejón de conchucos, in what is now the northern Peruvian andes. but before i do, it is worth considering the issue of merchants in ancient Peru from an archae-ological perspective.

Searching for Merchants and Their Tools

Market activity does not require a group of full-time specialists devoted to exchange and, in con-trast to colonial historical records for ecuador and Mesoamerica, there is scant evidence that such a group existed in Peru prior to the spanish conquest. if such a collective had existed, its continuing sur-vival would have depended on the profit made by exchange, and, thus, its members would have had a special interest in maximizing the range and vol-ume of items exchanged. in many ancient societies, such as sumerian Mesopotamia or new kingdom egypt, such entities constituted significant interest groups that influenced political and economic deci-sions (trigger 2003). This does not appear to have occurred in the prehistoric andes of Peru.

a single historic document, the famous Aviso published by María rostworowski (1970), states that there were six thousand merchants in the valley of chincha during inca times; this lone historical source has led to much speculation about the exis-tence in chincha of pre-hispanic merchants with links to traders of exotic pink-colored Spondylus on the north coast and even in ecuador. during the four decades since the publication of the aviso in english and spanish, there has been abundant archaeological research seeking confirmation of rostworowski’s claim, but no evidence of these merchants or their activities has yet been found. as craig Morris and Julián idilio santillana have writ-ten: “none of the research of several projects spon-sored jointly by the american Museum of natural history, instituto andino de arqueología . . . and the institute of andean research have found sig-nificant quantities of Spondylus…there is the pos-sibility that the information of the ‘aviso’ document is somehow inaccurate or exaggerated” (Morris and santillana 2007:136). attempting to salvage some-thing of the aviso’s credibility, Morris and santillana offer the unlikely alternative that it was written as a blueprint for the future rather than as a description of historical reality. not surprisingly, today most scholars remain skeptical about the accuracy of the aviso and its interpretation, and of the existence of full-time pre-hispanic merchants in general.

In the Realm of the Incas 323

it is interesting in this light that two com-mon tools used by merchants elsewhere in the world seem to be lacking or underdeveloped in the central andes: money and a standardized system of weights and measures. These two elements are particularly noteworthy because of the unambigu-ous traces they leave in the archaeological record. as a medium of exchange, money is designed to make transactions more fluid and to permit the accumulation of wealth. but exchanges can be made without money, and there are ways to accu-mulate wealth without the existence of money. nonetheless, money particularly in the form of precious metal coinage has distinct benefits. in the old World, metal coinage was first issued around 700 bc in lydia or aegina, and its advantages in market transactions account for its rapid adoption throughout the aegean, anatolia, and Persia over the following two centuries. independent but dis-tinctive inventions of metal coinage occurred in india and china, and its introduction there like-wise resulted in a comparably rapid spread over large areas (grierson 1977; Price 1986).

in the central andes, the introduction of possible special-purpose money known as naipes appears several centuries before the inca; these have been found in Piura in deposits from the lambayeque culture in the form of thin hammered-copper sheets (see also topic, this volume). They have not been found in refuse, but they do occur as tomb offerings, sometimes in decimally organized packets tied with string (hosler et al. 1990:18–20). some archaeologists have suggested the naipes could have played a part in long-distance exchange (shimada 1985), and others have even seen a link between these naipes and the mention in the aviso document of the use of copper for exchange by the supposed chincha merchants (hosler et al. 1990). if specialized merchants had existed in ancient Peru during the late pre-hispanic era, i would have expected the potential of the naipes as a medium of exchange would have been obvious—and that their use to have spread rapidly across ancient Peru, as did coinage in the old World. but thus far no naipes have been found anywhere south of lambayeque, and their adoption within the ancient

Peruvian area seems very limited. in contrast, the idea of distinctive standardized copper objects related to the naipes and known as axe-money seems to have found a more receptive audience fur-ther north, spreading first to ecuador and then into west Mexico, eventually reaching as far as oaxaca (hosler et al. 1990). it may be significant that the zones that adopted the relatives of the naipes are areas where the presence of merchants is confirmed by ethnohistoric documents. in ecuador, mer-chants known as mindalaes were reminiscent of the pochteca who thrived in Mexico during aztec times (salomon 1977, 1986; see also nichols, this volume; topic, this volume). one wonders, or at least i won-der, whether the lack of a robust class of merchants in ancient Peru may have been responsible for pre-venting the spread of the naipes to the south as a medium of exchange.

similarly, in ancient Peru there was no institui-onalized organization of weights or measures—at least not one that was mentioned in the ethnohis-toric record—nor have sets of standardized weights been recovered from the archaeological record. according to rowe (1946:324–325), although the incas employed a system of distance measurement that was at least as exact as that used in sixteenth-century europe, they did not have a standard system of weights. examples of the pan balance (aysana) are known from some late prehistoric sites in Peru, but i am unaware of any examples of them that predate the late intermediate Period or that come from out-side the coastal valleys. The absence of an accurate system of weights and measures would seem consis-tent with a tradition of exchange that emphasized barter and lacked specialized merchants.

in summary, the weak historic and archaeo-logical evidence of specialized merchants and the lack of money and a system of measurement by weight or volume suggests that while some form of market exchange probably existed throughout pre-hispanic times in the central andes, these activities may have remained underdeveloped in comparison to some parts of the old World or even Mesoamerica. This hypothesis, however, should be reevaluated as new archaeological research comes to light and not taken as an established fact.

32 4 Burger

Searching for Prehistoric Markets and Marketplaces: A Speculative Case Study

The role of marketplaces is particularly tricky from an archaeological perspective. as Mayer notes, if female domination of marketplaces, documented by contemporary ethnographers in Peru, pre-vailed in antiquity, then the spanish chroniclers may have systematically ignored these activi-ties because of gender bias. even in areas such as Mesoamerica, where marketplaces are recognized as being important in prehistory, they are difficult to identify archaeologically since they may involve few permanent structures and leave few residues (stark and garraty 2010). on the other hand, the

presence of market activity may be detectable from macropatterns revealed through artifact analysis, so we should not give up hope (hirth 1998; stark and garraty 2010).

Where should we begin our search for the elusive marketplaces of the pre-hispanic andes? if ethnography and ethnohistory can serve as a guide, pilgrimage and cult centers may be a good place to start. in contemporary Peru, in both high-land and coastal locations, syncretistic belief sys-tems draw thousands of believers to sacred points on the landscape or chapels and churches with miraculous saints and Virgins at crucial points of the year. While visitors often travel great distances to worship and participate in religious ceremonies,

figure 13.1Map of Peru indicating sites mentioned in the text. drawing by richard burger.

In the Realm of the Incas 325

adjacent to the places of worship are usually large fairs or markets, which operate parallel to and largely independent of the cultic activities (e.g., see the description of the cult of Wank’a and Qolla riti in sallnow 1987; the discussion of the celebration of the Virgen de yauca in silverman1991; and blanton, this volume).

among the goods exchanged are secular items not produced or available in most rural communi-ties as well as goods that relate specifically to the sacred place or the ceremonial practices carried out there. This pattern, of course, is not limited to the andes. as british anthropologists simon coleman and John elsner observed in their comparative study of old World religious pilgrimages, “pilgrim-age is as concerned with taking back some part of the charisma of a holy place as it is about actually going to the place. one of the most characteristic aspects of pilgrimage art in all the world religions

is the proliferation of objects made available to pilgrims and brought home by them as remind-ers and even tangible channels of connection with the sacred experience. in this way, the influence of the site can be retained in the domestic or mun-dane context into which a pilgrim has returned” (coleman and elsner 1995:100). given this close association between markets and pilgrimage cen-ters not only in the andes but also in the old World, it seems appropriate to consider the possibility that chavín de huántar could have served as an early hub of market activity (Figure 13.1).

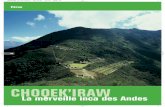

at 3,150 meters above sea level (masl) in the northern highlands of ancash, Peru, chavín de huántar is one of the best-known cult centers of pre-hispanic andes and has been the focus of archaeological investigations since Julio c. tello’s work in 1919 (Figure 13.2). located at the junction of two natural routes of transportation across the

figure 13.2google earth photograph of chavín de huántar with West Field (+) and kotosh religious tradition shrine (*) indicated.

326 Burger

glaciated cordillera blanca, chavín would have occupied a crucial spot for those traveling from the coast or callejón de huaylas into the callejón de conchucos and adjacent Marañón drainage (burger 1984, 1992). The site has been interpreted as an early pilgrimage complex (e.g., burger 1988; Patterson 1971; sallnow 1987 that thrived from 1,000–300 bc. elsewhere, i have suggested that it was the domi-nant center of a network of branch oracles which were scattered from nasca to lambayeque on the coast and from ayacucho to northern cajamarca in the highlands (burger 1988, 2008).

Much work has been carried out in chavín de huántar’s temple sector. archaeologists have doc-umented an impressive complex of open plazas, inner chambers, and summit buildings all devoted to religious worship, as expressed in the depiction of supernatural beings and mythical processions in the stone sculpture that adorns the buildings. The interpretation of this monumental complex as fun-damentally religious in character is reinforced by the ceremonial paraphernalia recovered from the excavations, such as mortars to grind hallucino-gens, spoons to inhale psychotropic snuff, engraved shell trumpets, and the lanzón, a remarkable cult object that remains in situ in the core of chavín de huántar’s old temple.

archaeological work within the chavín site has documented abundant exotic materials brought to the religious center by people from the coast and highlands. one of the most famous sculptures, known in Peru as the Medusa stone (Figure 13.3), shows the highland temple’s main deity holding two shells, Strombus and Spondylus, both of which are native to the warm waters off the coast of ecuador and northernmost Peru. This and other sculptures suggest that the identity of the old temple was closely linked with its access to distant goods of spe-cial power and value.

This iconographic claim has been more than confirmed by archaeological fieldwork (Figure 13.4). in the ofrendas gallery alone, luis lumbreras recovered more than three hundred ceramic ves-sels, most of which were brought from outside chavín de huántar (lumbreras 1971, 2007; see also burger 1984). The gallery contents included painted,

figure 13.3The Medusa stone, chavín de huántar. drawing by richard burger.

single-necked ceramic bottles from cajamarca; stirrup-spout bottles from the north coast valleys of chicama and Moche; heavily incised bowls from the central coast; a stone beaker from Jequetepeque; and a stone platter in the form a fish from Jaen. in 2001, in the nearby caracolas gallery, John rick unearthed twenty shell trumpets crafted from actual Strombus shell (rick 2008:27–28); interest-ingly, many are incised with imagery typical of the highlands and the cloud forest (ceja de selva) zone near the ecuador-Peruvian border. elsewhere in the temple area archaeologists have recovered obsid-ian from the Quispisisa source in ayacucho and cinnabar, probably from the santa barbara mine of huancavelica in the south central highlands (burger et al. 2006; burger and glascock 2000; burger and Matos 2002). These materials are proba-bly not evidence of market activity. on the contrary, these objects should be interpreted as gifts or trib-ute brought to the temple by pilgrims from distant areas, perhaps from those places with branch ora-cles or shrines. The finds do, however, provide vivid evidence of the long-distance movement of peoples of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds to the sacred center at chavín de huántar during the first millennium bc.

In the Realm of the Incas 327

Possible evidence of market activity can be gleaned from excavations in the residential zone adjacent to the ceremonial sector (Figure 13.5). in my doctoral research in chavín de huántar, i docu-mented that the residential zone spanned both sides of the huachecsa and that it expanded from only a few hectares in the urabarriu Phase (1000–700 bc) to more than thirty hectares along the western side of the Mosna river in Janabarriu Phase (600–300 bc). subsequent research by archaeologists from the instituto nacional de cultura and the stanford Project identified an additional residential zone of at least six hectares in la banda along the eastern

bank of the Mosna river across from the tem-ple area; this occupation dates primarily to the Janabarriu Phase (sayre 2010). i originally estimated that the peak population associated with the site at chavín de huántar may have reached between two and three thousand inhabitants (burger 1984), and the recent research in la banda only increases the plausibility of this original estimate. i also argued that the residents to the north of the huachecsa and further from the temple core seemed to be of lower status than those on the slopes adjacent to the tem-ple area. i suggest here that the growth of a large resident population and the short-term presence of

figure 13.4Map showing the sources of exotic materials brought to the chavín de huántar temple. drawing by richard burger.

328 Burger

pilgrims and travelers at chavín de huántar during the Janabarriu Phase would have made it an attrac-tive place for market exchange.

hirth (1998) has observed that marketplaces exchange make a wide range of products available to all households, albeit tempered by differences in wealth, and that this pattern should be observ-able archaeologically. Judging from the evidence currently available, this pattern indeed appears in the chavín residential areas. What is remarkable about the materials found in the residential areas is the quantity of exotic items associated with both the lower- and upper-status households. access to

exotic goods was not limited to one or two items; on the contrary, it applied to a variety of goods from many parts of the Peruvian highlands and coast. For example, considering the abundance of exotic styles, the ceramic vessels used in the resi-dential areas included pottery from the Moche and chicama valleys on the north coast, huánuco in the central highlands, and cajamarca in the northern highlands (burger 1984). a petrographic and x-ray fluorescence study of ceramics from the chavín residential area by isabel druc concluded that a substantial portion (thirty-six percent) of the pottery came from non-local sources. although

figure 13.5Map showing the sources of exotic materials brought to the chavín de huántar settlement. drawing by richard burger.

In the Realm of the Incas 329

most fragments could not be identified, some were attributed to Pallka in the middle casma Valley and huaricoto in the central callejón de huaylas (druc 1998:309–310). This situation at chavín de huántar was in sharp contrast to the other public coeval centers on the coast and in the highland studied by druc, all of which utilized locally produced pottery almost exclusively (druc 1998; druc et al. 2001).

The pattern of exotic household ceramics at chavín is paralleled by the lithic remains recov-ered. in domestic refuse from the Janabarriu Phase, the chipped lithics consist almost entirely of obsid-ian artifacts, which were common in all of the excavations regardless of household status (burger 1984:248). This pattern of abundant obsidian deb-itage and tools from household contexts was like-wise encountered by Matthew sayre in his 2005 excavations in la banda (sayre 2010:161). a study of eighty-six of the obsidian artifacts collected by burger revealed that about ninety-five percent came from the Quispisisa source located near huanca sancos in central ayacucho, some six hun-dred kilometers to the south (burger and glascock 2000), while small amounts came from the even more distant sources: the alca source in the cotahuasi Valley in the department of arequipa and the Petreropampa source in the department of apurimac (burger 1998:248, cuadro 21; burger et al. 1998, 2006).

access to non-local items by chavín residents extended even to the food they ate. a significant number of fish bones were recovered in the chavín de huántar midden, and all proved to come from the Pacific shores, probably in dried and salted form; at least three species were consumed (burger 1998:238, cuadro 18). There was also evidence of mollusk shells in both the lower- and upper-status areas, with at least thirteen different species repre-sented; clams, mussels, and sea snails were all iden-tified from the burger excavations. sayre likewise encountered numerous fragments of Pacific shells in the la banda residential area, including most of the species found in the household areas on the other side of the Mosna (sayre 2010:156). While a few of these mollusks may have been acquired for shell-ornament production, most seem to have

been consumed as food. i have suggested elsewhere that marine fish and shellfish, as a source of iodine, were especially valuable in highland diets in order to avoid goiter (burger 1985:276). both sayre and burger also recovered rare pieces of unmodified coral, which likewise must have come from coastal waters and been transported to the site (sayre 2010:160). like obsidian and exotic pottery, Pacific shell appears to have been available to the chavín de huántar population regardless of social status.

Finally, rare finds in household refuse of exotic items—such a Spondylus bead (sayre 2010), a tiny fragment of soldered gold jewelry (burger 1998:436–443; lechtman 1998) and a polished chlo-rite earspool covered with bright cinnabar pigment (burger 1998:187–188)—suggest that some distinc-tive costume items made of rare raw materials were also obtained by the local population.

The presence of these non-local materials by chavín de huántar residents can be explained if they had access to a marketplace or some other market activity. Particularly notable at chavín de huántar is the ample distribution of exotics among the households and the wide range of materials involved. The pattern just described for chavín de huántar differs sharply from the patterning that has been documented at inca sites. For example, in the huánuco Pampa region, exotics are totally absent from most households and when they occur, they are usually limited to a very few items distrib-uted by the inca elite to local ethnic leaders collabo-rating with them (e.g., Morris and Thompson 1985).

if the exotic items in the household refuse of the chavín de huántar residents were acquired by market mechanisms from pilgrims and/or trad-ers, it is reasonable to wonder what was received in exchange. one possibility is that the goods were exchanged for food and lodging, neither of which would leave easily identifiable archaeological traces. but it is also possible that items were pro-duced locally for exchange. some of these could have been of purely local origin—such as pota-toes from the upper slopes above the temple or the freeze-dried llama meat (charki) that the chavín de huántar villagers consumed in their own homes, or the freeze-dried tubers (chuño) produced in the

330 Burger

high grasslands above chavín de huántar (burger and Van der Merwe 1990; Miller and burger 1995). While plausible, these possibilities are difficult to evaluate archaeologically at this time.

in contrast, there is ample evidence of local craft activities that may have produced objects for exchange as well as for local consumption. For example, artifacts of llama bone were common in the residential area of chavín de huántar through-out the first millennium bc (burger 1998; sayre 2010). as mentioned, pilgrims frequently obtain objects from sacred centers in order to take back part of the charisma of the holy place to their homes and to demonstrate to others that they have successfully completed a difficult pilgrimage. carved spatulas and other bone ornaments carved with chavín reli-gious iconography have been found throughout the Peruvian coast and highlands, and are often used to illustrate the spread of the chavín cult (Figures 13.6–13.9). could some of these carved bones have been produced in the chavín de huántar residential area for the purpose of market exchange?

some additional support for this idea comes from sayre’s recent work in la banda, where he found evidence of craft activity in a residential area. Four bones were highly modified with chavín imagery, and two bore simple carvings etched into their surfaces. he further observed that “bone pieces similar to these appear across the site and may have been an artifact easily carried away by pil-grims and other visitors to the site” (sayre 2010:154).

other items possibly crafted for exchange from highland (puna) products include thread and textiles spun and woven from camelid wool and products made from the skins of slaughtered lla-mas, such as leather sandals. The latter possibility receives some support from one set of excavations in the chavín de huántar residential area, where a unique concentration of unifaces and drills were encountered; these tools are used in the manufac-ture of leather goods, such as footwear (burger 1998:39–40, 183).

The residents of the chavín de huántar settle-ment also created items from exotic raw materials that were hard to acquire. For example, i found evi-dence that one upper-status household in the area

to the west of the temple was involved in making beads and pendants from Spondylus shell (burger 1998:203, cuadros 14, 15, Figure 432). More recently, sayre has documented the production of carved and polished ornaments from what appears to be whalebone (sayre 2010:157–158). The latter cases are particularly interesting since they suggest that not only did the local population have access to a wide range of foods and household objects for personal use, but also they acquired exotic raw materials to work and presumably to exchange with others.

The evidence reviewed here provides a case for early market activity in the Peruvian andes, per-haps one with no parallel in inca times. it is tempt-ing to speculate where such a marketplace would

figure 13.6carved bone spatula from huaricoto, callejón de huaylas. drawing by richard burger.

In the Realm of the Incas 331

figure 13.7carved bone spatula: (a) front and (b) back view, kuntur Wasi, upper Jequetepeque Valley. courtesy of yoshio onuki and kinya inokuchi. Photographs by yutaka yoshii.

figure 13.8carved bone spatula, ofrendas gallery, chavín de huántar. after lumbreras 2007.

figure 13.9carved bone spatula, campanayuq rumi, Vilcashuaman, ayacucho. Photograph by yuichi Matsumoto.a b

332 Burger

have been located at chavín de huántar. The large plazas and terraces of the temple would have been an option, but this seems unlikely given the sacred nature of the temple space and the activities carried out there. Moreover, excavations in the open plaza areas have not found evidence of market activity. Following ethnographic examples, it seems more likely that such activities would have been carried out behind the temple. one possibility would have been the area referred to locally as the West Field (Figure 13.2). The zone is poorly known; however, in Janabarriu times, it featured a series of broad ter-races supported by masonry walls. since the two trails across the cordillera blanca funnel into this zone, it would be a convenient place to establish a marketplace to serve the arriving pilgrims and other travelers. This is one of the few areas outside the temple where domestic architecture has not been encountered. near the northwestern portion of this zone, daniel contreras (2010) found what appears to be small ceremonial structure of the kotosh religious tradition (krt). i interpret it as a non-chavín religious structure possibly built for visitors from the callejón de huaylas and other areas where these traditional highland ceremo-nial practices were still popular during the early horizon (burger and salazar 1985). This structure predates the open Janabarriu terraces, and little is known about the context of the small krt build-ing. it is possible that this structure was buried to create the open terraces, a space that would have been suitable as a marketplace, or alternatively, the marketplace could have already existed in this area and this krt shrine could have been located adja-cent to it. More research is needed in this zone to evaluate these admittedly speculative hypotheses.

before ending this exploration of the idea of marketplace exchange in chavín de huántar during the first millennium bc, i would like to briefly mention one other line of relevant evi-dence. beginning in the late initial Period, roughly around the time of chavín de huántar’s establish-ment, there is the first evidence for the use of lla-mas in long-distance transport. harnessed llamas were left as offerings at the templo de las llamas at the huaca negra in the Virú Valley (strong and

evans 1952); the animals are depicted on stirrup-spouted bottles recovered in north coast cemeter-ies; and occasional llama bones have been found at north coast sites such as huaca lucia (shimada and shimada 1985). More recently, analyses of fau-nal remains from campanayuq rumi, a chavín ceremonial center near Vilcashuaman, ayaucho, and excavated by yuichi Matsumoto (2010), indi-cated that llamas were being herded by 1,000 bc. This is germane because campanayuq rumi may have been pivotal in the acquisition and distribu-tion of Quispisisa obsidian to chavín de huántar. This process would have been greatly facilitated by the existence of llama caravans traveling from the high grasslands of ayacucho during the first millennium bc (browman 1974, 1975). The role of llama caravans organized by puna dwellers as a seasonal activity has been well documented eth-nographically in southern Peru and northern bolivia (e.g., Flores 1968; tripcevich 2007), and pre-hispanic versions of these camelid caravans may prove to be more relevant than the mindalaes of ecuador and the pochteca of Mesoamerica for understanding exchange and market activity in the pre-hispanic andes.

as suggested at the outset of this chapter, the role of market exchange in the central andes is not a linear one. While there seems to be some evidence for market activity at chavín de huántar dur-ing the first millennium bc, there is equally con-vincing proof that this region of highland ancash became increasingly isolated during the nine cen-turies after the collapse of the temple complex at chavín de huántar. Foreign items from the coast or other parts of the highlands are virtually absent at sites that belong to the huarás and recuay cultures during the terminal early horizon and the early intermediate Period. obsidian completely disap-pears, as does coastal shell and fish bone (burger, lau, Ponte, and glascock 2006; lau 2005, 2010). no imported pottery from the coastal salinar and Moche cultures has been encountered in the high-land sites. The lack of access to exotics by any mech-anism, market or otherwise, is exemplified by the local production of faux Strombus shell trumpets (pututus) made of ceramic.

In the Realm of the Incas 333

it is not until the eighth century ad with the demise of recuay and the subsequent expansion of Wari influence into the area that this insu-lar pattern breaks down and foreign materials begin to appear again at both large and small sites (burger, lau, Ponte, and glascock 2006; lau 2005). This trend reaches its peak during the late Middle horizon (ad 850–950), and ruth shady has suggested that the abundant ceramics and other exotics that appear at these sites may have more to do with increased market exchange than they do with a Wari conquest and/or state con-trol (shady 1988). but this apparent expansion of market activity was short lived. by ad 1000, the callejón de huaylas and the callejón de conchucos return to a state of relative isolation with little evidence of long-distance exchange or market activity during the poorly known late intermediate Period.

Final Remarks

to conclude, i would simply observe that the evi-dence from highland ancash illustrates the dan-ger of trying to essentialize the central andes as

a nonmarket civilization based on the inca case. The central andes saw the rise and fall of a mul-titude of civilizations, probably some with robust market activity and others with market activity reduced to a low level on a local scale. While pow-erful states and empires existed in the central andes long before the incas, tawantinsuyu may have been unusual or even unique in using state power to suppress market activity to the point where it was barely visible to spanish invaders.

Acknowledgments

special thanks to kenneth hirth and Joanne Pills-bury for encouraging my joint participation in the presentation with enrique Mayer in the 2010 dumbarton oaks Pre-columbian studies sympo-sium and for their willingness to allow us to divide the talk into two independent chapters for publish-ing purposes. i also appreciate comments on the manuscript by ken hirth, Jason nesbitt, Joanne Pillsbury, Jeffrey Quilter, and lucy salazar, and the assistance on the maps from christopher Milan. Finally, many of the ideas here came out of my dis-cussions with my friend enrique Mayer.

r e f e r e n c e s c i t e d

browman, david l. 1974 Pastoral nomadism in the andes.

Current Anthropology 15(2):188–196.

1975 trade Patterns in the central highlands of Peru in the First Millennium bc. World Archaeology 6(3):322–329.

burger, richard l. 1984 The Prehistoric Occupation of Chavín de

Huántar, Peru. university of california Publications in anthropology 14. university of california Press, berkeley.

1985 concluding remarks: early Peruvian civilization and its relation to the chavín horizon. in Early Ceremonial Architecture in the Andes, edited by

christopher donnan, pp. 269–289. dumbarton oaks research library and collection, Washington, d.c.

1988 unity and heterogeneity within the chavín horizon. in Peruvian Prehistory, edited by r. W. keatinge, pp. 99–144. cambridge university Press, cambridge.

1992 Chavín and the Origins of Andean Civilization. Thames and hudson, london.

1998 Excavaciones en Chavín de Huántar. Fondo editorial, Pontificia universidad católica del Perú, lima.

334 Burger

2008 chavín de huántar and its sphere of influence. in Handbook of South American Archaeology, edited by helaine silverman and William isbell, pp. 681–703. springer, new york.

burger, richard l., Frank asaro, Paul trawick, and Fred stross

1998 The alca obsidian source: The origin of the raw Material for cuzco type obsidian artifacts. Andean Past 5:185–202.

burger, richard l., Fidel Fajardo, and Michael d. glascock

2006 Potreropampa and lisahuacho obsidian sources: The geological origins of andahuaylas a and andahuaylas b type obsidians in the Province of amaraes, department of apurimac. Ñawpa Pacha 28:109–127.

burger, richard l., and Michael d. glascock 2000 locating the Quispisisa obsidian source

in the department of ayacucho, Peru. Latin American Antiquity 11(3):258–268.

burger, richard l., george lau, Victor Ponte, and Michael d. glascock

2006 The history of Prehispanic obsidian Procurement in highland ancash. in La complejidad social en la sierra de Ancash: Ensayos sobre paisaje, economía, y continuidades culturales, edited by a. herrera, c. orsini, and k. lane, pp.103–120. civiche raccolte d’arte applicata del castello Fozesco, Milan.

burger, richard l., and ramiro Matos Mendieta 2002 atalla: a center of the Periphery of

the chavín horizon. Latin American Antiquity 13(2):153–177.

burger, richard l., and lucy salazar 1985 The early ceremonial center of

huaricoto: a diachronic View. in Early Ceremonial Architecture in the Andes, edited by christopher donnan, pp. 111–138. dumbarton oaks research library and collection, Washington, d.c.

burger, richard l., and nicholaas van der Merwe 1990 Maize and the origin of highland

chavín civilization: an isotopic Perspective. American Anthropologist 92(1):86–96.

coleman, simon, and John elsner 1995 Pilgrimage: Past and Present. british

Museum Press, london.

contreras, daniel 2010 a Mito-style structure at chavín de

huántar: dating and implications. Latin American Antiquity 21(1):1–19.

druc, isabelle 1998 Ceramic Production and Distribution in

the Chavín Sphere of Influence (North-Central Andes). bar international series 731. bar, oxford.

druc, isabelle, richard l. burger, regina Zamojska, and Pierre Magny

2001 ancón and garagay ceramic Product-ion at the time of chavín de huántar. Journal of Archaeological Science 2(1):29–43.

Flores, Jorge 1968 Los pastores de Paratía: Una introduc-

ción a su estudio. instituto indigenista interamericano, Mexico city.

grierson, Philip 1977 Origins of Money. athlone Press,

london.

hirth, kenneth g. 1998 The distributional approach: a new

Way to identify Marketplace exchange in the archaeological record. Current Anthropology 39(4):451–476.

hosler, dorothy, heather lechtman, and olaf holm 1990 Axe-Monies and their Relatives.

dumbarton oaks research library and collection, Washington, d.c.

lau, george F. 2005 core-Periphery relations in the recuay

hinterlands: economic interaction at chinchawas, Peru. Antiquity 79:78–99.

2010 house Forms and recuay culture: residential compounds at yayno (ancash, Peru), a Fortified hilltop town, ad 400–800. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 29:327–351.

lechtman, heather 1998 examen técnico de un objecto de ale-

ación de oro procedente de chavín de huántar. in Excavaciones en Chavín de Huántar, by richard burger, pp. 252–256.

In the Realm of the Incas 335

Fondo editorial, Pontificia universidad catolica del Perú, lima.

lumbreras, luis g. 1971 towards a re-evaluation of chavín. in

Dumbarton Oaks Conference on Chavín, edited by elizabeth benson, pp. 1–28. dumbarton oaks research library and collection, Washington, d.c.

2007 Chavín: Excavaciones arqueológicas. 2 vols. universidad alas Peruanas Press, lima.

Matsumoto, yuichi 2010 The Prehistoric ceremonial center

of campanayuq rumi: interregional interactions in the Peruvian south-central highlands. Phd dissertation, department of anthropology, yale university, new haven.

Miller, george, and richard l. burger 1995 our Father the cayman, our dinner

the llama: animal utilization at chavín de huántar, Peru. American Antiquity 60(3):421–458.

Morris, craig, and Julián idilio santillana 2007 The inca transformation of the chincha

capital. in Variations in the Expression of Inka Power, edited by richard l. burger, craig Morris, and ramiro Matos Mendieta, pp. 135–163. dumbarton oaks research library and collection, Washington, d.c.

Morris, craig, and donald Thompson 1985 Huanuco Pampa: An Inca City and

Its Hinterland. Thames and hudson, london.

Murra, John V. 1995 did tribute and Markets Prevail in the

andes before the european invasion? in Ethnicity, Markets, and Migration in the Andes: At the Crossroads of History and Anthropology, edited by brooke larson and olivia harris, with enrique tandeter, pp. 57–72. duke university Press, durham, n.c.

Patterson, Thomas c. 1971 chavín: an interpretation of its

spread and influence. in Dumbarton Oaks Conference on Chavín, edited by elizabeth benson, pp. 279–48.

dumbarton oaks research library and collection, Washington, d.c.

1988 Merchant capital and the Formation of the inca state. Dialectical Anthropology 12:217–227.

1991 The Inca Empire: The Formation and Disintegration of a Pre-Capitalist State. berg, new york.

Price, Martin 1986 Thoughts on the beginning of coinage.

in Studies in Numismatic Method Presented to Philip Grierson. cambridge university Press, cambridge.

rick, John 2008 context, construction, and ritual in the

development of authority at chavín de huántar. in Chavín: Art, Architecture and Culture, edited by William conklin and Jeffrey Quilter, pp. 3–34. cotsen institute of archaeology, university of california, los angeles.

rostworowski, María 1970 Mercaderes del valle de chincha en la

época prehispánica: un documento y unos comentarios. Revista española de antropología americana 5:135–177.

1975 Pescadores, artesanos y mercaderes costeños en el Perú prehispánico. Revista del Museo Nacional 41:311–351. lima.

rowe, John howland 1946 inca culture at the time of the spanish

conquest. in Handbook of South Ameri-can Indians, edited by Julian h. steward, vol. 2, pp. 183–330. cooper square, new york.

sallnow, Michael J. 1987 Pilgrims of the Andes: Regional Cults in

Cusco. smithsonian institution Press, Washington d.c.

salomon, Frank 1977 Pochteca and Mindalá: a comparison

of long-distance traders in ecuador and Mesoamerica. Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society 9(2):231–246.

1986 Native Lords of Quito in the Age of the Incas: The Political Economy of North Andean Chiefdoms. cambridge university Press, cambridge.

336 Burger

sayre, Matthew 2010 life across the river: agricultural,

ritual and Production Practices at chavín de huántar, Peru. Phd disser-tation, department of anthropology, university of california, berkeley.

shady, ruth 1988 la época huari, como interracción de

las sociedades regionales. Revista andina 6:67–99.

shimada, izumi 1985 Perception, Procurement, and Manage-

ment of resources: an archaeological Perspective. in Andean Ecology and Civilization, edited by shozo Masuda, izumi shimada, and craig Morris, pp. 357–399. university of tokyo Press, tokyo.

shimada, Melody, and izumi shimada 1985 Prehistoric llama breeding and herding

on the north coast of Peru. American Antiquity 50:3–26.

silverman, helaine 1991 The ethnography and archaeology of

two andean Pilgrimage centers. in Pilgrimage in Latin America, edited by

n. ross crumrine and alan Morris, pp. 215–228. greenwood Press, new york.

stark, barbara l., and christopher P. garraty 2010 detecting Marketplace exchange in

archaeology: a Methodological review. in Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies, edited by christopher P. garraty and barbara l. stark, pp. 33–58. university of colorado Press, boulder.

strong, William duncan, and clifford evans 1952 Cultural Stratigraphy in the Viru Valley,

Northern Peru: The Formative and Florescent Epochs. columbia university studies in archaeology and ethnology 4. columbia university Press, new york.

tripcevich, nicholas 2007 Quarries, caravans, and routes to

complexity in the south-central andes. Phd dissertation, department of anthropology, university of california, santa barbara.

trigger, bruce 2003 Understanding Early Civilizations.

cambridge university Press, cambridge.