A Organização do Espaço Monástico entre os Cistercienses, no Portugal Medievo

Humanism, Painting and Patronage at Mogiła Abbey in the Renaissance. Abbot Erasmus Ciołek and...

-

Upload

jagiellonian -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Humanism, Painting and Patronage at Mogiła Abbey in the Renaissance. Abbot Erasmus Ciołek and...

Cîteaux – Commentarii cistercienses, t. 65, fasc. 1-4 (2014)

1 Henryk SamSonowicz, Polens Platz in Europa, Ostfildern 1997.2 Idem, “War das jagellonische Ostmitteleuropa eine Wirtschaftsinheit?”, Acta Poloniae Historica,

vol. 41 (1980), p. 85-97.3 Urszula BorkowSka, “The Ideology of ‘Antemurale’ in the Sphere of Slavic Culture (13th—17th

centuries)”, The Common Christian Roots of the European Nations. An International Colloquium in the Vatican, Florence 1982, p. 1206-1221.

4 Henryk GapSki, “Cystersi w Rzeczypospolitej i na Śląsku w XVI–XVIII wieku” [“Cistercians in the Kingdom of Poland and Silesia in the 16th–17th Centuries”], Monasticon Cisterciense Poloniae, I: Dzieje i kultura męskich klasztorów cysterskich na ziemiach polskich i dawnej Rzeczypospolitej od

HUMANISM, PAINTING AND PATRONAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEY IN THE RENAISSANCE

ABBOT ERASMUS CIOŁEK AND ARTIST-MONK STANISLAUS SAMOSTRZELNIK

Marcin STarzyńSki

The merger of the Kingdom of Poland with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania undoubtedly created not only the greatest but also one of the most populated European countries at the close of the fifteenth and well into the sixteenth centu-ries (Fig. 1).1 The Czech and Hungarian kingdoms remained under the rule of the Jagiellon dynasty of Lithuania, which was in control from 1386 to 1526. It there-fore seems appropriate to consider the Central Europe of this time the Europe of the Jagiellon.2

In the language of diplomacy of the second half of the fifteenth century, the Kingdom of Poland—located between the two cultures of the East and West—was considered the bulwark of Christianity (antemurale christianitatis).3 Poland was ethnically and religiously diverse, with a strong international position, and in an economic boom at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Having one of the oldest universities in that part of Europe (founded in Krakow in 1364), it was open to humanistic thought coming mainly from Italy, but echoes of Martin Luther’s speeches also reverberated. Initially, his words were well received mainly in the northwestern part of the Kingdom which had close ties to Germany, but were not as noticeable in Lesser Poland, a southern region bordering on Hungary where Krakow, the capital, was located. A considerable role was also played by the Polish ruler, Sigismund I the Old (1506-1548), a man utterly devoted to Catholicism. It is worth noting that despite considerable changes affecting the geography of the monastic network in Central Europe—brought about both by the development of the Protestant Reformation in the West and the Turkish expansion in the East—not a single Cistercian monastery in the Kingdom of Poland was liquidated during the sixteenth century.4

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 299 29/09/14 09:41

300 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

średniowiecza do czasów współczesnych [The History and Culture of Male Cistercian Monasteries in the Polish Territories from the Middle Ages to Modern Times], ed. Andrzej Marek wyrwa, Jerzy STrzelczyk, Krzysztof kaczmarek, Poznan 1999, p. 55-60.

5 Statuta capitulorum generalium Ordinis Cisterciensis, ed. Josephus Maria Canivez, IV, Louvain 1937, p. 236, no. 9 (1421); p. 244, no. 22 (1422); p. 259, no. 8 (1423); p. 289, no. 29 (1425); p. 471, no. 37 (1439); and others.

6 Tomasz kawka, Hugo leSzczyńSki, O. Cist., “Kacice-Mogiła”, in Monasticon Cisterciense Poloniae, II: Katalog męskich klasztorów cysterskich na ziemiach polskich i dawnej Rzeczypospolitej

Amongst the Polish houses of White Monks, the monastery in Mogiła (Clara Tumba) played a powerful role. Founded near Krakow in the 1230s by the knightly family of the Odrowąż, it was the tenth Cistercian foundation in Poland and the fifth in Lesser Poland. In the fifteenth century Mogiła was acknowledged as the leading centre of reform. Its abbots were granted the right to use the bish-op’s symbol of power (pontificalia), which put them among the clerical elite in Lesser Poland. They also served as inspectors of the Polish Cistercian abbeys on behalf of the General Chapter.5 Aware of the changes in the West and conse-quently concerned about them, the Cistercians of Mogiła at the beginning of the sixteenth century were far beyond their reach. As a result, we cannot share the opinion of the Polish historians Hugo Leszczyński, O. Cist., and Tomasz Kawka that the first half of the sixteenth century witnessed a decline in the number of priestly vocations, an economic crisis, and general laxity of discipline.6 not only

Fig. 1. Map of Poland and the grand Duchy of Lithuania, first half of the 16th century (ed. M. Starzyński).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 300 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 301

[Catalogue of Male Cistercian Monasteries in the Polish Territories], red. Andrzej Marek wyrwa, Jerzy STrzelczyk, Krzysztof kaczmarek, Poznan 1999, p. 104.

7 The cult of Crucified Jesus in Mogiła has not yet been developed in the scholarly literature. Lists of miracles were compiled from the 16th and 17th centuries using older notes, and all known informa-tion was revised in the 19th century; see Marcin STarzyńSki, Maciej zdanek, “Mogiła w czasach Stanisława Samostrzelnika. Szkic do dziejów klasztoru na przełomie XV i XVI wieku” [“Mogiła in Stanislaus Samostrzelnik’s Time. A Sketch of the History of the Convent at the Turn of the 15th to the 16th Century”], Cistercium Mater Nostra, vol. 1 (2007), p. 33-61.

8 Barbara MiodońSka, Miniatury Stanisława Samostrzelnika [The Miniature Paintings of Stanislaus Samostrzelnik], Warsaw 1983.

9 By way of clarification, there are two different men named Erasmus Ciołek who appear in the sources at the same time: the abbot of Mogiła under discussion here (b. c. 1492, abbot 1522-1546), and an older distinguished diplomat (1474-1522), secretary to King Alexander Jagiellon and bishop of Płock (1504-1522).

10 Marcin STarzyńSki, Maciej zdanek, “Mogiła w czasach Stanisława Samostrzelnika”, p. 49.

did Mogiła Abbey—which was wisely administered at the turn of the century by three abbots: doctor of theology of Krakow University Johannes Taczel of Racibórz (1493-1503), Johannes Weinrich (1504-1522) and Erasmus Ciołek (1522-1546)—strengthen its position in the structure of the church of Krakow, but raised its prestige as well. During Ciołek’s abbacy, Mogiła had thirty-three monks, and its substantial property holdings situated it amongst the most affluent Cistercian monasteries in the Polish territory. Additionally, it rose to be named one of the most important pilgrimage centers in Lesser Poland, owing to the growing popu-larity of the cult of the miraculous figure of the Crucified Jesus.7

Enjoying this elevated and apparently solid financial position, the community at Mogiła undertook major renovations. The Renaissance reconstruction of some of the abbey buildings took place under the abbacy of Erasmus Ciołek (1522-1546), including the creation of a new library, preserved in almost unaltered condition, and an important redecorating campaign of the interior of the monastery.

The artistic supervisor of the wall paintings was Brother Stanislaus, called Samostrzelnik, who has been acknowledged by art historians as the most distin-guished painter-miniaturist of Central Europe in the first half of the sixteenth century.8 The aim of this paper is to bring these two men—Abbot Erasmus Ciołek and Br. Stanislaus Samostrzelnik—closer together, to place them in the historical context early Renaissance Poland, and to present the fruits of their collaboration at Mogiła: the monumental wall-paintings which decorate the walls and vaults of the interior of the conventual church and other buildings within the monastery.

I. Erasmus CIołEk, abbot-HumanIst

Abbot Erasmus Ciołek9 is considered one of the pillars of Catholic orthodoxy in the ecclesiastical circles of Krakow during the first half of the sixteenth century,10 a description that does not exclude his penchant for the humanistic thought which was then gaining popularity in the Kingdom of Poland. He was born in Krakow c. 1492, one of three sons of the Krakow craftsman Mathias, a soap-boiler by

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 301 29/09/14 09:41

302 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

11 Helena FriedBerG, “Rodzina Vitreatorów (zasańskich) i jej związki z Uniwersytetem Krakow-skim na przełomie XV i XVI w.” [“The Vitreatores Family (zasańscy) and its Connections with Krakow University at the Turn of the 15th to the 16th Century], Biuletyn Biblioteki Jagiellońskiej [Bulletin of the Jagiellonian Library], vol. 18 (1968), p. 19-37.

12 Statuta nec non liber promotionum philosophorum ordinis in universitate studiorum Jagellonica ab anno 1402 ad annum 1849, ed. Josephus muczkowSki, Krakow 1849, p. 153.

13 Krakow, Jagiellonian Library, Cim. 4049: Iudicium astrologicum anni 1525, p. 2.14 Acta Tomiciana, vol. 14, ed. Vladislaus pociecha, Poznan 1952, no. 59.15 Marcin STarzyńSki, “Geschichte des Wappens der Cistercienserabtei in Mogiła”, Analecta cis-

terciensia, vol. 62 (2012), p. 274-275.16 Wypisy źródłowe do dziejów Wawelu z archiwaliów kapitulnych i kurialnych krakowskich 1539-

1541 [Source Excerpts on the History of Wawel Castle from the Archives of the Cathedral Chamber and Episcopal Curia in Krakow 1539-1541], ed. Bolesław przyBySzewSki, (Źródła do dziejów Wawelu [Sources on the History of Wawel Castle] 11/4), Krakow 1991, no. 681.

trade, and Agnes zasańska.11 One of his brothers, Johannes, became a doctor of medicine, another, Stanislaus, became a canon and episcopal judge in Płock.

Erasmus Ciołek began his studies at Krakow University in 1507, receiving a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts two years later and in 1512 a master’s degree, after which he began delivering lectures in the liberal arts.12 He made friends with nicolaus of Szadek, the renowned Krakow astrologer, who dedicated the horo-scope he prepared for the year 1525 to Erasmus. nevertheless, he abandoned a university career and decided to enter the Cistercian monastery of Mogiła. There, at a tender age (aetate iuniore),13 he was elected abbot, partly a result of his con-nections with the affluent family of the zasański, whose members were affiliated with the university. In late 1531 he was sent as an envoy of King Sigismund I to Pope Clement VII in Rome. On his return he visited Desiderius Erasmus in Freiburg, who gave him a letter for the bishop of Krakow, Petrus Tomicki (1524-1535), with his response to the accusations of the chief opponents of Albert Pii and Beda natalis.14 Fascinated by the personage of the philosopher, Abbot Erasmus sent him a gift, a masterful set of silver cutlery with allegorical representations, now in the collection of the Kunstmuseum in Basel. On the box containing those valuables is the inscription: ERASMVS ABBAS CLARATVMBAE ERAS(mo) ROTHERODAMO DONO MISIT and the coat-of-arms of Mogiła Abbey (Fig. 2).15

In 1531, Erasmus Ciołek was the first abbot of Mogiła to be honored by being made a canon of the Krakow Cathedral Chapter, and then auxiliary bishop of Krakow in 1544 while retaining his position as abbot. He maintained close con-tacts with numerous church dignitaries, whom he symbolically depicted via images of their coats of arms on the keystones of the library vaults and wall paintings of which fragments survive in the abbey church. Abbot Erasmus appar-ently granted loans to some of these dignitaries, such as Bishop Johannes Chojeński of Krakow and Johannes Wilamowski, canon of Krakow’s cathedral (who became bishop of Kamieniec in 1539).16 He was also on friendly terms with Petrus Gamrat, archbishop of Gniezno and bishop of Krakow (1538-1545), who apparently understood Ciołek’s taste, as in 1543 Gamrat gave him a generous gift: a chasuble made of red satin, richly embroidered with gold and embellished

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 302 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 303

17 Wypisy źródłowe do dziejów Wawelu z archiwaliów kapitulnych i kurialnych krakowskich 1542-1545 [Source Excerpts on the History of Wawel Castle from the Archives of the Cathedral Chamber and Episcopal Curia in Krakow 1542-1545], ed. Bolesław przyBySzewSki, (Źródła do dziejów Wawelu [Sources on the History of Wawel Castle] 11/5), Krakow 1997, no. 1403. The chasuble has unfortu-nately not survived.

18 Cracovia artificum 1501-1550, ed. Marian FriedBerG, Krakow 1936-1948, no. 1173. 19 Krakow, Prince Czartoryski Library, Ms no. 3061 IV.20 Marcin STarzyńSki, “Geschichte des Wappens”, p. 272-276.21 Kazimierz ŁaTak, “Cystersi mogilscy w nekrologu krakowskiego klasztoru kanoników regular-

nych laterańskich. Uwagi do dziejów konfraterni” [“Cistercian Monks of Mogiła in the necrology of Krakow’s Monastery of Regular Canons in the Lateran. notes on the History of the Confraternity”], Nasza Przeszłość [Our Past], vol. 90 (1998), p. 463.

with the crucifixion and images of saints.17 The abbot’s penchant for beautiful things can also be deduced by his own actions, for not only did he receive valu-able gifts, he also had them made. Krakow goldsmith Johannes zimermann was commissioned to make certain ecclesiastical ornaments (certa clenodia, “genuine jewels”) in gold and silver, although their exact nature is unknown as Ciołek was unable to pay for them.18

Images of Ciołek’s predecessors are known only from schematic representations on seals and stylized representations in the manuscript of the early sixteenth-cen-tury monastic chronicle by nicolaus of Krakow.19 An image of Erasmus Ciołek has, however, been preserved; it was made by Br. Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, the monk-artist who will be discussed in greater detail below. The painter depicted the abbot as an adorer present at the Crucifixion in the monastic cloister.20 Here the clergyman’s round face with prominent cheekbones and chiseled chin does not retain any features of ascetic dignity, and although he piously raises his eyes towards Christ, he smiles and appears to beam with inner serenity (Fig. 6).

Erasmus Ciołek died on December 6, 1546 after 24 years of service as abbot and was buried in the presbytery of the monastic church.21

Fig. 2. The cover of the box containing the set of silver cutlery sent by Abbot Erasmus Ciołek to Erasmus Desiderius, before 1536, Basel, Kunstmuseum. The inscription reads ERASMVS ABBAS CLARATVMBAE ERAS(mo) ROTHERODAMO DONO MISIT and is shown with the coat of arms of Mogiła abbey. (Feliks Kopera, “dary z Polski dla Erazma z Rotterdamu w historycznym Muzeum Bazylejskim” [“Gifts from Poland to Erasmus Desidersius in the Historical Museum in Basel”], Sprawozdania Komisyi do Badania Historyi Sztuki w Polsce [Report of the Commission to Study the History of Art in Poland], vol. 6 (1900), p. 130.)

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 303 29/09/14 09:41

304 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

II. stanIslaus samostrzElnIk, monk-artIst

When Erasmus Ciołek assumed the monk’s habit at Mogiła, the future author of his portrait, Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, was pursuing a distinguished artistic career outside the monastery walls.22 Samostrzelnik was born in Krakow c. 1480, son of Peter and Catherine (Anne?), who lived in a house belonging to the abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Koprzywnica. He entered the convent in Mogiła most probably after 1495 (when he was fifteen his future fellow monk, the monastic chronicler, nicolaus of Krakow, joined Mogiła Abbey).23 Called pictor de Mogila, Stanislaus appears in the sources for the first time in 1506.24 At that time the illus-trations of nicolaus of Krakow’s chronicle outlining Mogiła’s history—written in the popular form (gesta abbatum)—was being finalised in the monastic scripto-rium. Several painters, including Samostrzelnik, embellished the manuscript with somewhat humorous pen and ink sketches with a color wash of Mogiła’s abbots (Fig. 3).25

A few years later, around 1510, Samostrzelnik appeared at the court of Chris-topher Szydłowiecki, who was a friend and close associate of King Sigismund I the Old and later chancellor of the Kingdom of Poland, undoubtedly one of the most important and influential persons in the country.26 It is entirely possible that Samostrzelnik’s work was already quite well known, since Szydłowiecki, fasci-nated by the artist’s talent, brought about his exclaustration, made him his chap-lain,27 and employed him as a court painter. Moreover, he enabled Samostrzelnik to become acquainted with the newest trends in European Renaissance art, allegedly taking him on a journey to Buda in 1514 to the court of Vladislaus Jagiellon, and certainly to Vienna in 1515 where the meeting took place between the Jagiellon brothers— King Sigismund the Old of Poland and King Vladislaus of the Czech lands and Hungary—with the Emperor Maximilian Habsburg. In the known miniatures by Samostrzelnik one can discern echoes of those expeditions in the form of clear borrowings, not only from the paintings of Jörg Kölderer, court

22 Barbara MiodońSka, Miniatury, passim.23 Chronicon monasterii Claratumbensis Ordinis Cisterciensis auctore fratre Nicolao de Cracovia,

ed. Wojciech kęTrzyńSki, (Monumenta Poloniae Historica 6), Krakow 1893, p. 462.24 Wypisy źródłowe do dziejów Wawelu z archiwaliów kapitulnych i kurialnych krakowskich 1501-

1515 [Source Excerpts on the History of Wawel Castle from the Archives of the Cathedral Chamber and Episcopal Curia in Krakow 1501-1515], (Źródła do dziejów Wawelu [Sources on the History of Wawel Castle] 4), ed. Bolesław przyBySzewSki, Krakow 1965, no. 71.

25 Krakow, Czartoryski Library, Ms no. 3061 IV; Marcin STarzyńSki, “Chronicon monasterii Claratumbensis”, Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, ed. Graeme R. dunphy, Boston-Leiden 2010, p. 372.

26 Jerzy kieSzkowSki, Kanclerz Krzysztof Szydłowiecki. Z dziejów kultury i sztuki zygmuntowskich czasów [Chancellor Christopher Szydłowiecki. From the History of Culture and Art of the Time of King Sigismund I], Poznan 1912, p. 176.

27 Samostrzlnik then became a diocesan priest. Most probably it was a temporary exclaustration, because he signed his works with letters S.C. i.e. Stanislaus Claratumbensis. Unfortunately no written sources relating to this move from the monastery to Szydłowiecki’s court are known.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 304 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 305

Fig. 3. ‘Portraits’ of Mogiła’s abbots in the monastery chronicle written by Nicolaus of Krakow; pen and ink with color wash, before 1506, Krakow, Prince Czartoryski Library, ms. no. 3061 IV, p. 65 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 305 29/09/14 09:41

306 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

painter of the house of Habsburg, but also Albrecht Altdorfer, Albrecht Dürer and other artists working in his circle, such as Hans Suess of Kulmbach or Hans Sebald Beham.28

A certain number of Samostrzelnik’s works—or at least mention of them—can be traced. Petrus Tomicki, now bishop of Przemyśl and vice-chancellor of the Kingdom of Poland, was a humanist and influential patron of the arts whom the artist most likely met during the trip to Vienna in 1515; the following year Samostrzelnik illuminated a now-lost missal for the bishop.29 Before 1518 he was one of the illuminators of a missal for Bishop Erasmus Ciołek of Płock,30 and in 1519 he embellished the Privilege of Szydłowiecki for the collegiate church in Opatów.31

From 1520 to 1535 Samostrzelnik lived in Krakow where he had an illumina-tor’s studio. During this time he seems to have led a rather colorful life and as a result suffered some legal difficulties, including the pawning of (inter alia) a chal-ice from the church in Grocholice, of which he was then parish priest, into the hands of Krakow’s alchemist, nicolaus Lipko. He also had numerous slander actions filed against him, and was sued for child support by two of Krakow’s townswomen.32 not without reason did his biographer, Barbara Miodońska, describe him as impulsive and inconsiderate.

The portrait of Stanislaus compiled from judicial sources does differ substan-tially from the stereotypically sober image of an austere Cistercian monk, leading one to conclude, perhaps not unjustly, that Samostrzelnik’s relationship with Mogiła was rather more due to practical reasons than to a monastic—and priestly—vocation. Without a doubt he lived dynamically and his career developed along a similar vein.33 In 1524 he illuminated a prayer book for King Sigismund the Old,34 and established a relationship with the Jagiellon royal house which lasted for several years. In 1527 he illuminated a prayer book for Queen Bona,35 and in 1535 a now-lost prayer book for Sigismund’s and Bona’s daughter, Hedwig Jagiellon, wife of the elector of Brandenburg, Joachim II Hector Hohenzollern.

28 Barbara MiodońSka, Miniatury, p. 18-20.29 Wypisy źródłowe do dziejów Wawelu z archiwaliów kapitulnych i kurialnych krakowskich 1516-

1525 [Source Excerpts on the History of Wawel Castle from the Archives of the Cathedral Chamber and Episcopal Curia in Krakow 1516-1525], (Źródła do dziejów Wawelu [Sources on the History of Wawel Castle] 5), ed. Bolesław przyBySzewSki, Krakow 1970, no. 16.

30 not to be confused with the abbot of Mogiła (see n. 10). Warsaw, national Library, Ms no. 3306; Barbara MiodońSka, Miniatury mszału Erazma Ciołka [Miniature Paintings from the Missal Book of Erasmus Ciołek], Warsaw 2006, p. 6.

31 Opatów, Archive of St Martin’s Collegiate Church; Wojciech GerSon, “Przywilej opatowski” [“Privilege of Opatów”], Sprawozdania Komisyi do Badania Historyi Sztuki w Polsce [Report of the Commission of the Study of the History of Art in Poland], vol. 5 (1896), p. 102-106.

32 Wypisy źródłowe do dziejów Wawelu z archiwaliów kapitulnych i kurialnych krakowskich 1516-1525 [see n. 30 above], no. 243.

33 Barbara MiodońSka, Miniatury Stanisława Samostrzelnika, p. 5-23.34 London, British Library, Ms Add. 15281.35 Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms Douce 40, 21614.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 306 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 307

In cooperation with a painter known only as Johannes, Samostrzelnik decorated a banner which Albrecht Hohenzollern—the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights before secularization—gave to Sigismund I in homage on April 10, 1525 in the main market square in Krakow.36 He also illustrated the peace treaty signed with Turkey in 1533,37 and illuminated prayer books for Szydłowiecki in 152438 and the Lithuanian chancellor Albert Gasztołd in 1528.39 Moreover, Urszula Borkowska ascribed to Samostrzelnik the illumination of yet another prayer book made for Christopher Szydłowiecki.40

Before 1532, Samostrzelnik was working on the decoration of a chronicle of the Szydłowiecki family (Liber geneseos illustris familiae Schidloviciae),41 as well as painting the interior of the castle and the church in Szydłowiec.42 He renewed cooperation with Bishop Petrus Tomicki of Krakow, who commissioned (with associates) a collection of miniatures representing the archbishops of Gniezno to illustrate a text by Johannes Długosz entitled A Catalogue of the Archbishops of Gniezno.43 In the years 1533-1534 he illuminated two liturgical books for Bishop Tomicki, Ordo in feria quinta cenae Domini and Ewangelistarium.44 At orders from his episcopal patron, Fr. Stanislaus created a design which included the bishop’s ancestral coat of arms to adorn the bars closing the entrance to his burial vault, manufactured in the studio of Hans Vischer in nuremberg. It cannot be excluded that he also worked on the painted decoration of the burial chamber.45 He painted wax images of the bishop which were destined as votive offerings after his miraculous recovery (from an unidentified disease) in 1535,46 and designed

36 Adam Bochnak, “Mecenat artystyczny zygmunta Starego w zakresie rzemiosła artystycznego” [“The Artistic Patronage of Artistic Crafts by Sigismund the Old”], Studia do dziejów Wawelu [Studies on the History of Wawel Castle], vol. 2 (1961), p. 157, 252, n. 156.

37 zygmunt WdowiSzewSki, “Uwagi o dwóch zaginionych dziełach Stanisława Samostrzelnika [“notes on Two Missing Works by Stanislaus Samostrzelnik”], Sprawozdania Poznańskiego Towarzy-stwa Przyjaciół Nauk [Report of the Poznan Society of the Friends of Science], vol. 1 (1952-1954), p. 134-135.

38 Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, studio prefetto; Archivo Storico Civico, Mss 459-460.39 Munich, Bayerisches nationalmuseum, Ms 3663.40 Urszula BorkowSka, “Odzyskany modlitewnik Krzysztofa Szydłowieckiego [Recovered

Prayer Book of Christopher Szydłowiecki”], in Benedyktyńska praca. Studia historyczne ofiarowane o. Pawłowi Szczanieckiemu w 80. rocznicę urodzin [Benedictine Work. Historical Studies Dedicated to Father Paweł Szczaniecki OSB on his 80th Birthday], ed. Jan A. Spież, OP, and zbigniew wielGoSz, Tyniec 1997, p. 213-224.

41 Kórnik, Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Ms MK 3641-3651.42 Wanda PuGeT, “Przyczynek do działalności Stanisława Samostrzelnika. Malarstwo ścienne

w budowlach fundacji Szydłowieckich [“A Contribution to the Activities of Stanislaus Samostrzelnik. Wall Painting in Buildings Founded by the Szydłowiecki Family”], in Renesans. Sztuka i ideologia [Renaissance. Art and Ideology], ed. Tadeusz S. JaroSzewSki, Warsaw 1976, p. 487-503.

43 Warsaw, national Library, BOz, Ms no. Cim. 5.44 Krakow, Archive and Library of the Cathedral Chapter, Ms 16 KP, 19 KP.45 Jerzy KieSzkowSki, Przyczynek do kulturalnej działalności Piotra Tomickiego [A Contribution to

the Cultural Activities of Petrus Tomicki], Krakow 1905, p. 13-16.46 Marian SokoŁowSki, “Wota woskowe florenckie jako objaśnienie wotów Tomickiego” [“Floren-

tine Wax Votive Offerings as an Explanation for Tomicki’s Votive Offerings”], Sprawozdania Komisyi

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 307 29/09/14 09:41

308 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

embroideries to adorn a mitre belonging to the bishop of Krakow, Thomas Strzempiński (1455-1460),47 and probably the crook of the crosier located today in the treasury of St Mary’s Church in Krakow.48 Samostrzelnik is considered the author of a portrait of Petrus Tomicki on the cloister wall of the Franciscan monastery in Krakow,49 while a painting representing St George in the treasury of the Wawel Cathedral has also been attributed to him.50

Two long-standing protectors and patrons of Samostrzelnik, both admirers and connoisseurs of the masterful illuminator’s art, died one after the other, Szydłowiecki in 1532 and Tomicki three years later. Whether tired of his mode of life, or concerned about the impossibility of finding further influential and wealthy patrons (costly manuscript painting was being superseded by much cheaper wood-cuts), the versatile artist—operating effectively both in manuscript illumination and in wall and easel painting—decided to return to life at Mogiła Abbey. Abbot Erasmus—given the privilege exempting the monastic church from the rules of enclosure by the Holy See and thus opening it to both men and women to pray every day at certain hours51—decided to use Samostrzelnik’s talent to remodel the interior of the church and other abbey buildings in the spirit of the Renaissance. The coming together at this time of these two renowned personages resulted in the last great artistic undertaking in which Stanislaus of Mogiła was involved – deco-ration of the interior of the monastery with monumental wall paintings, which will be the subject of the next section. With this task accomplished by about 1538, Samostrzelnik produced no more work, apparently abandoning the profession he had practised for at least forty years. He died at Mogiła in 1541 at the age of nearly sixty.52

do Badania Historyi Sztuki w Polsce, [Report of the Commission of the Study of the History of Art in Poland], vol. 7 (1906), col. CCLXXXIX-CCXCII.

47 Adam Bochnak, “Mitra biskupa Tomasza Strzempińskiego i Stanisław Samostrzelnik [The Mitre of Bishop Thomas Strzempiński and Stanislaus Samostrzelnik]”, Sztuka i historia. Księga pamiątkowa ku czci profesora Michała Walickiego [Art and History. A Memorial Book in Honour of Professor Michał Walicki], Warsaw 1966, p. 92-96.

48 Jan Samek, “ ‘Bacula pastoralia’ w Polsce (nieznany pastorał w kościele Mariackim w Krakowie i Stanisław Samostrzelnik) [‘Bacula pastoralia’ in Poland (the Unknown Crosier in St Mary’s Church in Krakow and Stanislaus Samostrzelnik)]”, Folia Historiae Artium, vol. 11 (1975), p. 91-107, esp. 102-104.

49 Barbara MiodońSka, “Renesansowe portrety biskupów krakowskich w klasztorze Franciszkanów w Krakowie” [“Renaissance Portraits of Krakow’s Bishops in the Franciscan Monastery in Krakow”], Rocznik Krakowski [Krakow’s Yearbook], vol. 35 (1961), p. 8-10, 16-19, fig. 1-2.

50 Tadeusz DoBrowolSki, “ze studiów nad ikonografią patrona rycerstwa” [“From the Icono-graphic Studies of the Patron Saint of Knighthood]”, Folia Historiae Artium, vol. 9 (1973), p. 59-69.

51 Krakow, Prince Czartoryski Library, Ms 3652 III, p. 49.52 Kazimierz ŁaTak, “Cystersi”, p. 463.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 308 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 309

III. a mEEtIng of tHE mInds: CIołEk’s and samostrzElnIk’s rEdECoratIng CampaIgn at mogIła abbEy

Realizing the vision of Abbot Ciołek and Stanislaus Samostrzelnik was not a simple task, especially because of the considerable surface area of walls and vaults which were to be decorated. The artist would presumably have assembled a team of assistants who, under his care, stood on scaffolding and began the time-consuming work. Vaults in the library, the cloister, and the presbytery were adorned with floral and vegetal ornament (Fig. 4), and several monumental wall paintings were applied to the walls of the church and the cloisters (Fig. 6 and 7).

During conservation work on the church from 1945-1948, hitherto unknown fragments of sixteenth-century paintings were uncovered in the south transept over the twin eastern chapels, consisting of monumental representations of the Odrowąż and Awdaniec coats of arms.53 Under the shields, which were sur-rounded by Samostrzelnik’s characteristic ribboned laurel wreaths, are fragments of Latin inscriptions which facilitate identification of their owners. The Odrowąż device can be indisputably linked to Krakow’s bishop, Ivo Odrowąż (1218-1229) a founder of the abbey (Fig. 5), and the Awdaniec to Johannes Chojeński (1537-1538),54 one of Ivo’s successors as bishop, a prominent humanist, affiliated with King Sigismund the Old and the intellectual elite of Poland. This portion of the Mogiła church decoration can thus be dated to Chojeński’s brief tenure as bishop from July 1537 to March 1538. While Bishop Ivo did not during his lifetime use this heraldic device, the idea of attributing the Odrowąż coat of arms to him was no doubt linked to the widespread sixteenth-century belief in the so-called antiq-uity of the heraldic devices.55

Somewhat earlier another scene was discovered on the east wall of the presby-tery: the Annunciation with the angel on the left presenting a lily to Mary, who stands on the right under a splendid orange tent. A much smaller figure of Veron-ica holding her veil appears at the summit over the oculus; she is flanked by two coats of arms with mitres and crosiers, symbolizing a bishop and an abbot. The half-figure of a cloaked man wearing the papal tiara and pointing to an orb held in his left hand appears above the annunciate angel (Fig. 6). An inscription above the coats of arms explains that this wall was painted during the tenures of Bishop Johannes Latalski and Abbot Erasmus, which falls most likely between February 1536 and July 1537.56

53 Józef duTkiewicz, “nowoodkryte dekoracje malarskie” [“newly Discovered Painted Decora-tion”], Ochrona Zabytków [Protection of Monuments], vol. 1 (1948), p. 69-70.

54 Władysław pochiecha, “Chojeński Jan”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish Biographical Dictionary], vol. III, Krakow 1937, p. 396-399.

55 Marcin STarzyńSki, Herby średniowiecznych opatów mogilskich [Coats of Arms of the Medieval Abbots of Clara Tumba], Krakow 2005, p. 101.

56 Irena SuŁkowSka-kuraSiowa, “Latalski Jan”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish Biographical Vocabulary], vol. 16, Wrocław-Warsaw-Krakow 1971, p. 562-563.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 309 29/09/14 09:41

310 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

Fig. 5. Mogiła Abbey church, east wall of the south transept, detail of heraldic decoration showing the imagined coat of arms of the founder of the monastery, Bishop Ivo Odrowąż of Krakow; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1537–1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 4. Mogiła Abbey cloister vault, detail of the floral decoration; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, before 1541 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 310 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 311

The north wall of the cloister contains a fresco discovered in 1912 showing the scene of the Crucifixion (Fig. 7). In addition to the central figure of Christ flanked by Mary, John and three angels, a figure clothed in a white habit and holding a crosier kneels at the base of the cross. As mentioned above, this can be none other than the abbot of Mogiła, Erasmus Ciołek, donor of the fresco as indicated by the inscription: fr(ater) Erasmus abbas fecit, and the date 153(?), most probably 1538. The coat of arms at the base of the cross is that of the abbey (derived from the Odrowąż coat of arms, and similar to that on the transept wall57), not the abbot’s personal device, for as a burger he did not have the coat of arms of a noble family, but used that of the convent, i.e. the so-called assumed coat of arms. In this man-ner, he manifested not only his relations with the mighty family of the Odrowąż, but simultaneously stressed the “longevity” of the monastery in the eyes of Krakow’s church and the structures of the order in the Polish territory. The mitre

57 Tadeusz doBrowolSki, Studja nad średniowiecznym malarstwem ściennym w Polsce [Studies on Medieval Wall Painting in Poland], Poznan 1927, p. 117-129. Similar to the prayer books illuminated by Samostrzelnik, a heraldic motif was placed symmetrically under the painting where it forms a semantic enclave.

Fig. 6. Mogiła Abbey church, east wall of the presbytery, the Annunciation showing the figures of Mary and Gabriel, the Veil of St Veronica, two heraldic devices with mitres and crosiers and the half-figure of a pope; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1536–1537 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 311 29/09/14 09:41

312 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

Fig. 7. Mogiła Abbey cloister, north wall showing the Crucifixion; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 312 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 313

placed above the shield indicated that abbots of Mogiła had the right to use the episcopal insignia, which, accordingly, positioned them within the elite of the cler-gymen of the time.58 It also constituted a clear visual representation—the shield carrying the insignia of the convent crowned with an attributes of the abbot’s authority.

Special attention should also be paid to the decoration of the abbey library made during Ciołek’s tenure, the focal points of which are ten images of coats of arms painted on the keystone bosses. Combined with details of heraldic decoration in the abbey church and cloisters, these paintings together form a great heraldic pro-gramme, a means by which the abbot—as patron—was striving to commend him-self to God and to future members of the community (“brother Erasmus, abbot, did this”). And to his contemporaries, he was demonstrating in visual terms the rela-tionships he had cultivated within the church milieu, the royal court, the univer-sity, and finally, the intellectual elite of the time.

The first scholar to suggest that the decoration of the Mogiła library was made by the monk Stanislaus of Krakow was Jerzy Kieszkowski,59 following which Stanisław Tomkowicz identified the coats of arms on the library vault keystones. This work is now, however, incomplete, for Tomkowicz carried out his inventory of the library prior to its extensive restoration.60 After the conservation of the vault and restoration of the frescos c. 1912, Gerard Kowalski, O. Cist., undertook the identification of the coats of arms and attempted to link them to specific people.61 Bearing in mind that this programme was intended to convey a specific ideological content, it will be crucial both to identify the coats of arms and their owners, and to consider their composition: the arrangement of the devices, their hierarchy, and the shape of the shields and attributes. Only then will it be possible to fully decode the intended message.

The room that was refurbished as a library was erected in the second half of the fifteenth century, which may be deduced by the traces of the superstructure over the eastern chapels of the south transept of the conventual church, perhaps

58 Marek derwich, “Rola opata w koronacjach królów polskich” [“The Role of Abbots in the Cor-onations of Polish Kings]”, Imagines potestatis. Rytuały, symbole i konteksty fabularne władzy zwierzchniej. Polska X–XV w. [Imagines potestatis. Rituals, Symbols and Iconographic Contexts of the Supreme Power. Poland 10th to 15th Centuries], ed. Jacek BanaSzkiewicz, Warsaw 1994, p. 31-58.

59 Jerzy kieSzkowSki, “nowe szczegóły do wewnętrznego urządzenia kaplicy Tomickiego w kate-drze krakowskiej” [“new Details of the Interior Decoration of the Tomicki Chapel in Krakow Cathe-dral”], Sprawozdania Komisyi do Badania Historyi Sztuki w Polsce [Report of the Commission to Study the History of Art in Poland], vol. 6 (1900), col. LXXVIII-LXXIX.

60 Stanisław Tomkowicz, “Powiat krakowski” [“District of Krakow”], Teka Grona Konserwatorów Galicyi Zachodniej, [Report of the Circle of Conservators of Western Galicia], vol. 2, Krakow 1906, p. 177-178.

61 Gerard kowalSki, “Polichromia sali bibliotecznej opactwa mogilskiego z r. 1538” [“Paintings in the Mogiła Abbey Library (1538)”], Sprawozdanie i Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Opieki nad Polskimi Zabytkami Sztuki i Kultury za rok 1913 [Report and Publication of the Society for the Protection of Polish Monuments of Art and Culture for the Year 1913], Krakow 1914, p. 10-12.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 313 29/09/14 09:41

314 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

originally used as a chapel.62 It has been preserved nearly intact since the sixteenth century remodeling, except for replacement of the floor and bookshelves during a restoration in 1913 (Fig. 8). The redecorating was finished in 1538, as stated in the inscription on the north wall: AD HONOREM ET GLORIAM OMNIPOTENT(is) DEI, FR(atr)IB(us) SUIS AD UTILITATEM, FRATER ERASMUS ABBAS FECIT 1538.

In addition to the vegetal ornaments along the ribs, the vault is adorned with ten coats of arms painted on the bosses of the keystones. The Renaissance shields with the Odrowąż coat of arms and the initials E A C (Erasmus abbas Clarae Tumbae) (Fig. 9), located on the walls under the rib consoles, reinforce the inscription pictorially.

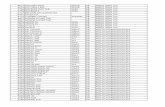

The keystones on which coats of arms were painted are situated in three rows, in the arrangement 3 + 4 + 3 (Fig. 10). Those in the middle row are slightly larger and turned toward the north wall of the library, which is contiguous with the pres-bytery wall of the abbey church, while the coats of arms on the smaller keystones are turned to the axis of the room.

In the centre of the programme (middle row, second and third keystones – B & C), are the coats of arms of the royal couple, King Sigismund the Old (the eagle of Sigismund with a interlaced monogram S) (Fig. 11) and Queen Bona Sforza (the snake of the Sforza family wearing an open crown with four finials) (Fig. 12). On the right heraldic side of the eagle of Sigismund the Old is the coat of arms of his son, Sigismund Augustus (A) (Fig. 13). At the opposite side of the room is a Sulima coat of arms (black half-eagle over three gold stones = D) of Krakow’s bishop Petrus Gamrat, a trusted counselor to the Queen, bibliophile, collector of works of art and patron of the arts, who during the meetings he orga-nized gathered the intellectual elite of Krakow (Fig. 14). Bearing in mind that the preconization of Gamrat for Krakow’s bishopric took place on July 24, 1538, and a ceremonial ingressus on October 26, it can be assumed that the redecorating of the Mogiła library vault most likely took place in the autumn of that year.63

The six remaining coats of arms on the vault of the library can all be linked to canons of Krakow cathedral, including Abbot Erasmus Ciołek (F), who had been appointed to the chapter in 1531 (Fig. 15) .

nałęcz (E) (silver kerchief in a circle on a red shield = (Fig. 16) was identified by Kowalski with Gregory of Szamotuły,64 rector of Krakow University in 1538, although it could equally be ascribed to Lucas noskowski, rector in 1526-1527, town councillor of Krakow, doctor to king Sigismund the Old, Bishop Tomicki

62 Ewa Łużyniecka, Architektura klasztorów cysterskich filiacji lubiąskiej [Cistercian Architecture of the Daughter Houses of Lubiąż Abbey], Wrocław 1995, p. 82.

63 Kazimierz harTleB, “Gamrat Piotr”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish Biographical Vocabu-lary], vol. 7, Krakow 1948-1958, p. 264-266.

64 kowalSki, Polichromia, p. 11; “Grzegorz z Szamotuł”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish Biographical Vocabulary], vol. 9, Wrocław-Warsaw-Krakow 1961, p. 90-91.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 314 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 315

Fig. 8. Mogiła Abbey library, remodeled during the second half of the 15th century with vault paintings by Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538, floor replaced in 1913, furni-ture modern (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 9. Mogiła Abbey library wall, coat of arms of Abbot Erasmus Ciołek with his initials E A C (Erasmus abbas Clarae Tumbae), 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 315 29/09/14 09:41

316 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

south wall of sanctuary

mon

astic

gar

dens

east

wal

l of s

outh

tran

sept

Fig. 10. Mogiła Abbey, schematic diagram of the coats of arms on the library vault (letters in subsequent figures refer to this diagram):A. White Eagle of Sigismund AugustusB. White Eagle of Sigismund the OldC. Snake of Sforza familyD. SulimaE. nałęczF. OdrowążG. SzaszorH. Ciołek I. TopórJ. Jastrzębiec

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 316 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 317

Fig. 12. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (C) with the coat of arms of the Polish queen Bona Sforza (1494–1557), wife of Sigismund the Old; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 11. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (B) with the coat of arms of the Polish king Sigismund the Old (1467–1548); Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 317 29/09/14 09:41

318 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

Fig. 14. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (D) with the coat of arms of the bishop of Krakow, Petrus Gamrat (1487–1545); Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 13. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (A) with the coat of arms of the Polish king Sigismund Augustus (1520–1572), son of Sigismund the Old and Bona Sforza; Stani-slaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 318 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 319

Fig. 15. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (F) with the coat of arms of Abbot Erasmus Ciołek; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 16. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (E), with the coat of arms possibly of Johannes Zbąski, a royal secretary, canon of Krakow cathedral; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 319 29/09/14 09:41

320 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

and chancellor Christpher Szydłowiecki,65 i.e. a person closely related to the mighty protectors of the painter of the Mogiła library. While it is true that Greg-ory of Szamotuły could, as a university professor and in accordance with a priv-ilege from Sigismund the Old in 1535, use the noble family coat of arms, such use is not confirmed in any of the surviving sources. nevertheless, it is certainly justifiable—by virtue of placing the coat of arms of the rector of the university in the programme—to emphasize the long-standing relations between the abbot of Mogiła and Krakow’s academic circle. What is more probable, however, is that the nałęcz coat of arms belonged (as did those displayed on the smaller keystones) to one of Krakow’s canons. I am of the opinion that it should be identified with Johannes zbąski, a royal secretary, canon of Krakow cathedral and a dean.66

Szaszor (G) (headless silver eagle on a red shield (Fig. 17) is identified with a Krakow canon, Johannes Wilamowski (later bishop of Kamieniec),67 and Ciołek (H) (red bull on a silver shield, without colors on the vault (Fig. 18) was the coat of arms of the secretarius maior Regni Samuel Maciejowski.68

The Topór coat of arms (I) (silver axe on a red shield, Fig. 19) was identified by Gerard Kowalski with Stanislaus Tarło, a long-standing royal secretary, canon of Krakow cathedral and bishop of Przemyśl from 1537, and—importantly—listed in the act appointing Ciołek to the cathedral chapter.69 Jastrzębiec (J) (cross surrounded by a silver horseshoe on a blue field; uncolored on this vault, Fig. 20) of George Myszkowski, an arch-deacon of Krakow, chancellor to Bishop Petrus Tomicki, and—similarly to Stanislaus Tarło—was listed in the act of appointment of Abbot Erasmus to the Cathedral Chapter.70

The coats of arms of the four canons—nałęcz (E), Ciołek (H), Szaszor (G) and Jastrzębiec (J)—were placed on shields of the same shape, whereas those of Krakow’s bishop and two apostolic protonotaries—the abbot of Mogiła (F) and the bishop of Przemyśl (I)—were painted on shields that are different from the others. The arms on the smaller keystones turned, according to heraldic courtesy, to the

65 Janina Bieniarzówna, “noskowski Łukasz”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish Biographical Vocabulary], vol. 23, Wrocław-Warsaw-Krakow-Gdansk 1978, p. 225-226.

66 Ludwik ŁęTowSki, Katalog biskupów, prałatów i kanoników krakowskich. Prałaci i kanonicy krakowscy [Catalogue of Krakow’s Bishops, Prelates and Canons. Krakow’s Prelates and Canons], vol. 4, Krakow 1853, p. 303; Władysław pociecha, Królowa Bona (1494-1557). Czasy i ludzie Odrodzenia [Queen Bona (1494-1557). People of the Renaissance], vol. 2 Poznan 1949, p. 385; vol. 4, Poznan 1958, p. 81.

67 ŁęTowSki, Katalog, vol. 4, p. 227–228.68 Włodzimierz dworzaczek, “Maciejowski Samuel”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish

Biographical Vocabulary], vol. 19, Wrocław-Warsaw-Krakow-Gdansk 1974, p. 64-69. The surname Ciolek, and the coat of arms of Ciolek are two different and unrelated things; ‘ciolek’ in Polish means a young bull, hence the image.

69 kowalSki, Polichromia, p. 11; Władysław pociecha, Królowa Bona, vol. 2 (1949), p. 10-11; vol. 4 (1958), p. 38-41, 198-199, 206.

70 Archive of the Cistercian monastery of Krakow-Mogiła, Ms 27, fol. 67; Halina kowalSka, “Myszkowski Jerzy”, Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. 22, Wrocław-Warsaw-Krakow-Gdansk 1977, p. 372-373.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 320 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 321

Fig. 18. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (H) with the coat of arms of the secretarius maior Regni Samuel Maciejowski; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 17. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (G), with the coat of arms of Johannes Wilam-owski, canon of Krakow cathedral; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 321 29/09/14 09:41

322 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

Fig. 20. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (J) with the coat of arms of George Myszkowski, canon of Krakow cathedral; Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

Fig. 19. Mogiła Abbey library, keystone (I) with the coat of arms of the bishop of Przemyśl, Stanislaus Tarło (c. 1480-1544); Stanislaus Samostrzelnik, 1538 (photo: Mogiła Abbey).

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 322 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 323

centre of the room where the arms of the royal family and the bishop of Krakow were prominently placed in the middle row. This denotes the hierarchy of impor-tance: in the center of the program the symbolic (heraldic) representation of the Polish state and the diocese of Krakow, flanked by the signs of close associates of the royal court, and the bishop.

In these details one may perceive careful planning and sizing in the heraldic composition. Its ideological significance consisted of a symbolic presentation of tise circle of friends, who at the same time played the role of mighty protectors of Abbot Erasmus and Mogiła Abbey, among them the king himself and the bishop. The canons were related to the Court Office, and, as Abbot Erasmus, to the diplomatic service of King Sigismund the Old. By way of illustration, Samuel Maciejowski played the role of Court Secretary and director of the office from 1537; Johannes Wilamowski, as one of the most trusted envoys, was sent to Pope Paul III and Emperor Ferdinand I. Tarło participated in John zapolya’s diplo-matic mission to the Viennese court to settle the problem of border robberies, and to discuss details of the marriage of Sigismund Augustus with Archduchess Eliz-abeth;71 he was also in the wedding retinue of Isabel the Jagiellon, daughter of king Sigismund the Old, for her marriage to John zapolya. Abbot Ciołek himself played the role of envoy to Rome at the turn of 1531-1532 with a mission to endorse the prenuptial agreement of George Olelkowicz Słucki and Helena Radziwiłł. All these personages must be recognised as the most distinguished representatives of humanism amongst the Polish episcopate in the first half of the sixteenth century.

ConClusIon

“Coats of arms constitute the language for the one who is able to decode them”, as Victor Hugo said in Cathedral of Notre Dame.72 So it was through the coats of arms that Abbot Erasmus Ciołek expressed himself as a patron of the arts. I believe, however, that not only gloria of almighty God and utilitas of the monks made him decide to establish the polychrome decoration inside Mogiła Abbey, but that in the representations of these coats of arms he immortalised his protectors and simulta-neously presented wide relationships within the milieu of the royal court and the church of Krakow. Heraldic emblems which adorned the monastic interior epito-mise this significance, as well as showing to what extent the language of heraldry was propagated in Poland in the first half of the sixteenth century. They illustrate as well how, during the five centuries since the foundation of the Order, Cistercian

71 Andrzej wyczańSki, Między kulturą a polityką. Sekretarze królewscy Zygmunta Starego (1506-1548) [Between Culture and Politics. Secretaries of King Sigismund the Old (1506-1548)], Warsaw 1990, passim.

72 Pour qui sait le déchiffrer, le blazon est une algebre, le blazon est une langue. Victor huGo, Notre Dame de Paris, Paris 1836, p. 155.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 323 29/09/14 09:41

324 MARCIn STARzyńSKI

artistic ideals had changed. Last but not least, they can also be illustrative of the great—albeit somewhat forgotten—mural painting of Lesser Poland during the reign of King Sigismund the Old.

Institute of History Marcin STarzyńSkiJagiellonian UniversityGolebia 13, 31-007Krakow, Poland

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 324 29/09/14 09:41

HUMAnISM, PAInTInG AnD PATROnAGE AT MOGIŁA ABBEy 325

Humanisme, peinture et patronage à l’abbaye de Mogiła pendant la Renaissance : L’Abbé Erazm Ciołek et le Père Stanisław Samostrzelnik

Stanisław Samostrzelnik (vers 1480–1541), l’un des plus grands enlumineurs de manuscrits en Pologne au cours de la première moitié du XVIe siècle, était aussi moine du monastère cistercien de Mogiła (Clara Tumba). L’auteur retrace ici le contexte de la vie artistique et décrit les oeuvres de celui qu’il nomme le Maître de Mogiła : de grandes fresques dans l’église conventuelle, sur les murs et les voûtes du cloître, et les voûtes de la bibliothèque. En exécutant cette tâche, l’artiste a inclus des blasons dans la décoration intérieure, ce qui est à interpréter comme une carte symbolique des contacts de l’abbaye à l’intérieur de l’Église de Petite-Pologne. En témoigne la manière dont est représenté un groupe d’amis intimes et de protecteurs d’Erazm Ciołek (vers 1492-1546), abbé de Mogiła, également chanoine de Cracovie et évêque de Laodicée, un humaniste fasciné par Érasme et étroite-ment lié tant avec la cour royale polonaise qu’avec l’Université de Cracovie.

Humanism, Painting and Patronage at Mogiła Abbey in the Renaissance: Abbot Erasmus Ciołek and Fr. Stanislaus Samostrzelnik

Stanislaus Samostrzelnik (c. 1480–1541) was one of the greatest manuscript illuminators in Poland in the first half of the 16th century, while also a monk at the Cistercian monastery of Mogiła (Clara Tumba). The author here creates the context for the artistic life and last known works of this so-called Master of Mogiła, which were large-scale frescoes in the convent church, walls and vaults of the cloisters, and library vaults. In carrying out this commission, the artist included heraldry in the interior decoration, interpreted here as a symbolic map of the abbey’s contacts within the Church structure of Lesser Poland. This is done by showing how they represent a group of intimate friends and protectors of Erasmus Ciołek (c. 1492–1546), abbot of Mogiła and also canon of Krakow cathedral and Laodicean bishop, a humanist fascinated by Erasmus Desiderius and closely connected to the Polish royal court as well as Krakow University.

Humanismus, Malerei und Patronage in der AbteiMogiła während der Renaissance: Abt Erasmus Ciołek und Fr. Stanislaus Samostrzelnik

Stanislaus Samostrzelnik (1480–1541) war einer der bekanntesten Illustratoren von Hand-schriften in Polen in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts und zugleich Mönch in dem zisterzienserkloster Mogiła (Clara Tumba). Der Autor zeigt den zusammenhang des künst-lerischen Lebens und der letzten bekannten Arbeiten dieses so genannten Meisters von Mogiła auf, bei denen es sich um großformatige Fresken in der Konventkirche, an den Wänden und Gewölben des Klosters und in den Gewölben der Bibliothek handelt. Bei der Ausführung dieser Arbeiten nahm der Künstler bei der Innenausstattung heraldische Ele-mente auf, die in diesem Aufsatz als symbolische Darstellung der Beziehungen des Abtes innerhalb der kirchlichen Struktur in Kleinpolen interpretiert werden. Die geschieht, indem aufgezeigt wird, inwieweit diese eine Gruppe enger Freunde und Protektoren von Erasmus Ciołek (1492–1546) sind, der Abt von Mogiła sowie Kanoniker an der Kathedrale von Kra-kau und ein religiös indifferenter Bischof war; ein Humanist, der von Erasmus Desiderius fasziniert war, und enge Verbindung zu dem polnischen Königshof und der Universität Krakau unterhielt.

97342_Citeaux_t65_05_aStarzynski.indd 325 29/09/14 09:41

![Os Cistercienses e a Água [The Cistercians and Water]](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/631576d6c32ab5e46f0d51ca/os-cistercienses-e-a-agua-the-cistercians-and-water.jpg)