How to read ethnography by Gay y Blasco, Paloma and Huon Wardle (2007)

-

Upload

st-andrews -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of How to read ethnography by Gay y Blasco, Paloma and Huon Wardle (2007)

Reviews

Bowen, John R. 2007. Why the French don’tlike headscarves: Islam, the state, andpublic space. Princeton and Oxford:Princeton University Press. x + 290 pp.Hb.: £17.96. ISBN: 978 0 691 12506 0.

In answering the question in the title of hisbook, Bowen aims to practise an‘anthropology of public reasoning’, whichrelates political philosophy, public policy andcommon sense. In the first part of the book heanalyses France’s Rousseau’s social contractphilosophy-inspired ‘Republican thinking’,which is characterised by emphasising generalinterests and shared values over individualinterests and pluralism, implying the crucialrole of the state to educate people in what itmeans to be a French citizen, thus creatingunity over regional and religious differences.

Bowen argues that the dominantnarrative of laıcite should be understoodagainst the background of the Republicanstruggle against the Catholic Church, thelegacy of which is handed down to Frenchcitizens through civic instruction and popularmedia. The contemporary presence of Islamin schools is seen as a threat that the clockmay be turned back on state efforts to keepreligion from controlling young minds and itsstruggle to forge a common French identity.

The author notes that the notion oflaıcite as ‘protected public space’ as used inthe debates about headscarves goes farbeyond the 1905 law, which is generallyreferred to as its official introduction in theFrench administration. Concerned withprotecting the individual’s freedom to believeor not believe, and to practise one’s faith, thelaw constrained the state, not ordinarycitizens. Bowen points out that it is oftenunclear what meanings of ‘public space’ areinvolved in current debates over threats tolaıcite: (public) state services; all shared socialspace; or the general interest. He argues that

these kind of no agreed-on definitionsprovide a narrative framework that permitspublic figures to speak as if there is ahistorical object called laıcite, when in fact thedebates are about what laıcite should be andhow Muslims ought to act.

In the second part of the book, Bowenargues that it was the specific conjuncture ofdomestic and foreign circumstances thatcaused headscarf ‘affairs’ and turned theheadscarf into a symbol of social problems,e.g. the celebration of the bicentennial of theFrench Revolution, the Rushdie incident, thebirth of the FIS (Front Islamique du Salut),Algerian civil war and the 1995 bombings inParis.

In the third part of the book, a thirdexplanation of ‘why the French don’t likeheadscarves’ is given by arguing that peoplelinked the headscarf problem to three othersocietal issues: the fear of communalism,which would threaten the directcommunication between the state andcitizens; the fear of Islamism, perceived as aform of communalism which denies therestriction of religion to the private sphere andclaims the superiority of Islamic values overothers; and the fear of sexism, perceived as adenial of the equality between the sexes andneo-feminist celebrations of the female body.

The author’s focus on ‘naturallyoccurring’ arguments in presentations anddebates from which he draws certain ways ofreasoning that may account for actions isfruitful. Interestingly, the openly ironic toneBowen uses to comment on the claims ofthose opposing the headscarf in the name oflaıcite is missing when he discusses thestatements of headscarf-wearing Muslimwomen. Since he acknowledges that ‘we allwrite from within our backgrounds’ (p. 7) thiscan be appreciated in the author’s positioningof himself. Such positioning becomesproblematic, however, in several instances

360 Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale (2008) 16, 3 360–387. C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.doi:10.1111/j.1469-8676.2008.00043.x

REVIEWS 361

when he discusses interviews with Muslimwomen, and tends to treat their responses as‘facts’ or observed information rather thanreported information. For example, when heappears to take at face value (headscarf-wearing) Saida Kada’s claims about what wassaid during her interview with the LaıciteCommission (p. 197). In other instancesBowen is so determined to prove that hisreadings of (oral) texts are valid that he fillspages with very detailed ethnographicdescriptions, thus testing the perseverance ofhis readers.

Despite these minor weak points, Bowenwrote a marvellous book which illustratesthat ‘affairs’ concerning Muslims andnon-Muslims cannot be explained in terms ofa general incompatibility of Islam and theWest, but call for detailed analysis of localcivic cultures, as well as a contextualisedunderstanding of specific domestic andforeign factors contributing to societaltensions.

MARJO BUITELAARUniversity of Groningen (The Netherlands)

Byron, Reginald and Ullrich Kockel (eds.).2006. Negotiating culture. Moving, mixingand memory in contemporary Europe.Berlin: Lit Verlag. x + 209 pp. Pb.: €24.90.ISBN: 3 8258 8410 4.

The book under review discusses the subjectof cultural boundaries within a region where,in the context of transnational mobilisation,people who belong to different ethnic groupslive together, interact, cross borders andbridge margins. There is a lively discussion onhow people experience heterogeneity withinnational borders within Europe, and howcultural boundaries can influence everydaypractices. Conditions in Europe have changedin response to the dramatic increase ofimmigrants, most of whom are from countriesoutside Europe. The enlargement process ofthe European Union enhances and developsan environment which increases cultural,linguistic and religious diversity. The book

deals with south-eastern Europe (SEE) (theBalkans), the Italian Alpine Valley, theCzech–German frontier, Northern Ireland,Hungary and Sweden.

Klaus Roth demonstrates how peoplecommunicate by describing their everydaypractices and shows how people in SEEmanage to live under a ‘system’ ofcoexistence. He singles out four mainstrategies of inter-ethnic relations: those ofharmony, coexistence, segregation andconflict. Additionally, he argues that there areessential lessons to be learned from SEEcountries, and he encourages the use of SEEtraditions of inter-ethnic coexistence inEuropean Union practices. Ana Lulevafocuses on gender construction processes andtheir development over time in the southernpart of the Bulgarian Black Sea coast, thetowns of Sozopol, Nesseba and Pomorie. In2003 she conducted a field study in thosethree towns and she investigatesintermarriages between Bulgarians andGreeks. She also describes the construction ofGreek and Bulgarian femininity in thosecities. She explores the similarities and thedifferences that exist between Bulgarian andGreek women, their roles and theconsequences for marriage practices.

In her contribution Mladena Prelicundertakes an analysis of the Serbiancommunity living in Hungary. Thecommunity is small in number but stillmanages to preserve a distinctive identity. Shefocuses on the community’s socioculturalpractices, particularly its openness in thechoice of spouses. Young people tend tomarry partners outside the community,though the older generation oftendisapproves, fearing that ‘Serbianness’ couldeventually be lost to assimilation by thesemarriage practices.

Mairead Nic Craith and AmandaMcMullan discuss migration processes inNorthern Ireland by providing a historicalframework with respect to Chinese, Pakistaniand Indian immigrants. Gabriele Marrancistudies Muslims in Northern Ireland and heshows that although they come from differentcountries – which in their local contexts may

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

362 REVIEWS

even be hostile to one another – Muslimimmigrants often say that they feel part of‘one family’ (p. 168). He tells how the Englishlanguage is used in mosques instead of Arabic,because English has become the ‘symbol’ ofintegration into a wider global community(p. 182).

Jaro Stacul interprets the advancement ofthe Right in the Italian political arena in theVanoi valley, an Alpine community in theTrentino region. He identifies ‘localism’ as‘the term that best describes the politicalorientation of the people of the valley’ (p. 34)because the Trentino region used to be astronghold of the Christian Democratic Party(DC). Local culture is seen as a set of sharedideas centring on the notions of autonomouswork and private property (p. 40). ‘Localism’also demonstrates a preference for a place(this valley) without (non-European)immigrants. Stacul expresses the complexitiesof politics where xenophobia and oppositionto migration provide space for discrimination.Adam Kuper in his chapter presents the‘culture of discrimination’. He argues that themulticulturalist discourse has to be seen as anobject of analysis and not an analytical tool(p. 186). He points out that ‘culture is soambiguous, even though we do seem to knowwhat we mean by culture’ (p. 190). Hehighlights the different uses of culture inFrench, German and English traditions, andthe role of anthropologists in formulating adiscourse against racism.

In conclusion, the book explores culturesand cultural boundaries and the formationand negotiation of identities. It describespeople’s (transnational) mobilisation in themeans of cultural diversity, culture contactand the coexistence in multiethnic societies.This collection of articles is a goodintroduction for students and researchersdealing with boundaries, nationalism,culture contact, multiculturalism,cross-border mobilisation and inter-ethnicrelations.

CHRISTOS KARAGIANNIDISUniversity of Sussex (UK)

de la Cadena, Marisol and Orin Starn(eds.). 2007. Indiginous experience today.Oxford and New York: Berg. vii + 415 pp.Pb.: £19.99. ISBN: 978 184520 519 5.Hb.: £55.00. ISBN: 978 184520 518 8.

Les quatorze articles publies dans cet ouvragecollectif ont ete presentes d’abord lors d’unsymposium international organise par lafondation Wenner-Gren, en mars 2005.Invites a reflechir sur les pratiques identitairesdes peuples autochtones, les chercheurs,anthropologues pour la plupart, ont fournides contributions dans le but de depasserl’idee selon laquelle les peuples autochtonessont voues a l’assimilation et de montrer, aucontraire, qu’ils seront des acteurs majeurs auXXIe siecle. Cet ouvrage se presente commeune contribution critique dans le champ desetudes postcoloniales et a l’ambition desusciter une lecture plus complexe de laquestion autochtone contemporaine.

L’introduction, redigee par les editeurs,invite a travailler sur les questions autochtonesa partir d’une demarche relationnelle etprocessuelle. Les articles qui suivent enadoptent le principe, composant ainsi unouvrage d’une grande coherence. Commepoint de depart, les editeurs defendent l’ideequ’il n’existe pas de definition univoque duterme autochtone et que l’essence de l’identiteautochtone est diverse et dynamique, commeen temoignent la circulation internationale duconcept et la diversite des engagementsautochtones dans les revendicationsidentitaires. Le terme autochtone necessiteainsi une nouvelle conceptualisation qui passepar une mise en perspective relationnelle del’identite autochtone et par la reconnaissancede l’importance des non autochtones dans laconstruction de cette identite. Toute etude surcette question doit egalement etre conduitedans une perspective historique etprocessuelle qui met en avant le role des Etatsdans la definition de l’identite et l’influence deleur organisation politique sur la variabilitedes revendications autochtones.

Ce programme est suivi opiniatrementpar les auteurs dont les articles sont repartis

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 363

en cinq parties. La premiere partie analyse lacirculation du concept d’autochtone et lavariabilite de son utilisation entre les groupesethniques (Anna Tsing, Emily T. Yeh) et al’interieur de ces memes groupes (ClaudiaBriones). Le texte de Claudia Briones analyse,par exemple, les differentes strategiesidentitaires des Mapuche d’Argentine. Ellemontre comment les jeunes mapucheaffirment leur identite autochtone au sein degroupes de fans de heavy metal, lesMapuheavies, ou de musique punk, lesMapunkies, tout en imposant de nouvellesvaleurs.

La deuxieme partie de cet ouvragereprend les questions du territoire et de lasouverainete. La question du territoire estconsideree comme la pierre angulaire de touterevendication autochtone. Il faut cependantconsiderer la singularite du developpement dechaque revendication en la replacant dans lecontexte politique dans lequel elle s’estdeveloppee (Valerie Lambert, FransescaMerlan). Michael F. Brown interroge le termede souverainete qui a trop peu fait l’objet,selon lui, de remises en question, et ce, malgrel’usage frequent qui en est fait tant par lesautochtones que par les anthropologues. Il entrace donc l’itineraire, depuis l’Amerique duNord, et explique que le terme apparaıtrarement dans les documents de l’ONUrelatifs aux questions autochtones du fait deson attachement intrinseque a la formepolitique qu’est l’Etat. Il revele cependant quel’usage du concept de souverainete au sein desdebats sur les droits autochtones s’est etendude son application politique a tous les aspectsde la vie autochtone (education, langue,religion, arts. . .).

La troisieme partie entend depasser l’ideeconventionnellement admise que lesautochtones sont fixes a un territoire precis etpropose une analyse sur les diasporas despeuples autochtones (James Clifford) et lafacon dont les caracteristiques de l’identiteautochtone d’un groupe peuvent etrereutilisees dans les strategies identitaires d’unautre groupe (Michelle Bigenho). C’est danscet esprit que Louisa Schein analyse lesrelations que la communaute Hmong/Miao

americaine entretient avec ses communautesd’origine du sud est de l’Asie. Elle montre lerole joue par les medias Hmong dansl’entretien de relations economiques avec lepays d’origine par le biais de developpementsde projets cinematographiques conjoints etanalyse l’importance des images idealisees, surle pays et la culture d’origine, que vehiculentces productions videos chez les Hmong endiaspora.

La quatrieme partie traite des politiquesdont l’objet est de definir l’identiteautochtone (Amita Baviskar, Francis B.Nyamnjoh, Linda Tuhiwai Smith). L’articlede Linda Tuhiwai Smith analyse le role jouepar les reformes neoliberales dans laconstruction de nouvelles subjectivites chezles Maoris de Nouvelle-Zelande. Elle montreque le desengagement de l’Etat, dans lecontexte neoliberal, et la prise en main decertains secteurs par des associations et desorganismes maoris ont permis aux Maoris demontrer leur capacite d’autogestion, leurdonnant l’espace et la legitimite de reclamerl’independance. La cinquieme partie invite areflechir sur l’hegemonie du savoir occidentaldans la definition de l’identite autochtone(Julie Cruikshank, Paul Chaat Smith) et meten abıme ainsi une reflexion sur la relationentre anthropologues et autochtones.

En somme, ce recueil d’articles a l’interetde reveler la grande diversite des pratiquesidentitaires autochtones, tout en montrant laforce des reseaux et l’influence structurantedes Etats. Cet ouvrage sera utile aux etudiantssouhaitant prendre conscience de la variationdes pratiques identitaires, mais egalement auxchercheurs specialises sur cette questiondesireux de comparer leurs donnees.

CAROLINE HERVEEHESS, Paris (France) and Universite Laval,Quebec (Canada)

Cerwonka, Allaine and Liisa H. Malkki.2007. Improvising theory. Process andtemporality in ethnographic fieldwork.Chicago: Chicago University Press. xi +203 pp. Pb.: $18.00. ISBN: 0 226 100316. Hb.: $45.00. ISBN: 0226 10030 8.

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

364 REVIEWS

Liisa Malkki et Allaine Cerwonka proposentun livre novateur qui donne a voir, de maniereoriginale et instructive, l’ethnographie tellequ’elle se pratique. Improvising Theory reunitla correspondance qu’entretiennent les deuxjeunes femmes lors du premier travailethnographique que mene Allaine Cerwonkaau milieu des annees 1990. Jeune etudiante ensciences politiques, elle conduit une enquete aMelbourne sur le nationalisme australien atravers l’etude d’un groupe de jardinage (EastMelbourne Garden Club) et d’uncommissariat de police (Fitzroy PoliceStation). Liisa Malkki, sans dirigerdirectement ses recherches – role qu’occupaitalors Mark Pettraca de l’Universite deCalifornie a Irvine – conseille la jeunechercheuse et l’aide a developper uneapproche originale, eloignee des techniquestraditionnellement utilisees en sciencespolitiques.

Les echanges d’e-mails, reproduits iciavec le minimum d’alteration, rendentintelligemment compte de la specificite d’untravail de terrain. Le lecteur peut suivre leshesitations, les excitations et les deceptionsd’une enquete en train de se derouler. Onmesure alors l’importance de la subjectivite duchercheur dans la conduite d’un travailscientifique, au-dela du mythe romantiqued’un anthropologue omniscient,imperturbable collecteur de donneesobjectives, scientifique ‘froid’ au sein d’unepopulation indigene. Le livre soulignenotamment l’importance de ce qu’AllaineCerwonka appelle les ‘Nervous Conditions’sur le travail de recherches; elle ecrit ainsi: ‘Tosay that understanding is always a situatedpractice is not simply to acknowledge that wealways bring personal “bias” (. . .) to ourresearch. It is to say that we alwaysunderstand through a set of priorities andquestions that we bring to thephenomenon/object that we are researching(. . .). This point bears on the importantquestion of how one’s personhood is also acondition for knowledge claims, rather than adeterrent to understanding’ (p. 28).

Certes, a force de vouloir montrer letravail ethnographique au quotidien realise

par des individus tirailles par une multituded’emotions, l’ouvrage s’ouvre a quelquescritiques. Par exemple, il flirte parfois avec unsubjectivisme un peu inutile. L’effet estd’ailleurs renforce par le choix des auteurs quiisolent le processus reflexif de sesconsequences concretes sur le travailscientifique final, publie notamment en 2004(voir Cerwonka 2004). Et les attaques desdeux auteurs a l’encontre d’une approche dite‘positiviste’ des sciences sociales, erigee enveritable repoussoir normatif peu a meme decomprendre la dimension humaine de touterecherche, apparaissent parfois caricaturales.

Mais l’ouvrage demeure d’une qualitereelle. Son importance pedagogique doitd’ailleurs etre soulignee. Nul doute que lalecture de ce livre devrait guider leschercheurs confrontes pour la premiere foisau travail ethnographique en leur permettantd’accepter la difficile prise en compte desemotions dans le travail d’enquete. Car bienau-dela de la normativite des ‘bonnespratiques’ que proposent trop souvent lesmanuels de recherche, Cerwonka et Malkkirappellent ici l’importance et la fecondite des‘bonnes questions’ qui doivent determiner letravail scientifique.

Leur travail bibliographique estegalement d’excellente qualite et s’avere d’uneaide precieuse pour toute reflexion surl’imperatif d’une approche reflexive ensciences sociales. Quelques referencessupplementaires auraient d’ailleurs pu etremobilisees pour resituer le livre dans lamultitude de contributions qui, aujourd’hui,aident a repenser ces questions; Gupta etFerguson, abondamment cites, auraient puetre confrontes a d’autres auteurs commePhilippe Bourgois, Nancy Scheper-Hughesou Michael Burawoy. Mais il s’agit la bienplus d’un commentaire que d’une critique carl’usage des references qu’elles choisissent demobiliser apparaıt systematiquementpertinent.

Saluons pour conclure le courage desdeux auteurs. A une epoque ou la reflexivitese reduit trop souvent a un mot d’ordre, a unnouvel imperatif auquel les chercheurssacrifient des pages inutiles, vides de sens et

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 365

d’interet, A. Cerwonka et L. Malkki montrentveritablement la fecondite d’une interrogationconstante sur son rapport a l’objet. L’exerciceest difficile: il renvoie directement a l’intime etimpose un retour sur soi dont il est parfoiscomplexe d’isoler le veritable interetscientifique. Cet ouvrage, en abordantfrontalement mais finement la complexite deces interrogations, apporte une reponsenovatrice. Et ce benefice n’est possible quegrace a l’honnetete des deux jeunes femmes etnotamment d’Allaine Cerwonka qui, endonnant a voir ses doutes, ses peurs et sesjoies a su intelligemment montrer que:‘Anthropology is not a social science toutcourt, but something else. What thatsomething else is has been notoriouslydifficult to name precisely because it involvesless a subject matter – which, after all,overlays with that of other disciplines in thehumanities and the social sciences – than asensibility’ (p. 162).

ReferenceCerwonka, Allaine. 2004. Native to the nation:

disciplining landscapes and bodies in Aus-tralia. Minneapolis: University of MinnesotaPress.

SEBASTIEN ROUXUniversite Paris 13 et CNRS, Paris (France)

Eller, Jack David. 2007. Introducinganthropology of religion. Culture to theultimate. New York and London: Routledge.xv + 352 pp. Pb: £19.99. ISBN:9780415408967.

Ainsi que l’annonce l’auteur, cet ouvrageentend, d’une part, servir d’introduction al’anthropologie des religions et, d’autre part,‘appliquer une approche anthropologique al’etude des religions mondialescontemporaines’, demarche qu’Eller estimedelaissee et urgente a mettre en œuvre.

Soucieux de ce double objectif, l’auteurexpose d’abord (chapitres 1 a 6) les methodes(‘L’etude anthropologique de la religion’) etthematiques classiques du domaine (la

croyance, le symbolisme, le langage et lecomportement religieux, l’ordre et la morale)de facon claire et plus developpee qu’il n’estcoutume dans les ouvrages introductifs. Laseconde partie de l’ouvrage expose les debatssouleves par le monde contemporain a travers,successivement, les nouveaux mouvementsreligieux, les religions mondiales, la violencereligieuse, le secularisme, le fondamentalismeet la religion aux Etats-Unis. La bibliographieest riche, et un index precis permet une lecturetransversale.

Certains passages stimulent le lecteur,debutant ou avide de synthese, notammentl’etat des lieux du debat passionnant autourdes ‘espaces rituels, performances rituelles et“theatre social”’ (pp. 128–133). D’autres sontplus critiquables: il est peu representatifd’exposer la notion de purete et le systemehindou des castes a partir du seul article deGough, et sans mentionner Dumont.D’autant que le chapitre concerne reprend etrelie precisement les themes (religion, ordresocial et pollution) au cœur de lademonstration dumontienne.

L’argument central de l’auteur se resumea deux parti-pris auxquels je souscrispleinement: 1) ‘l’integration de la religiondans la culture englobante’ (p. xiii), 2)l’anthropologie, consciente de la relativite desa terminologie et soucieuse des religionstelles qu’elles sont pratiquees, localement rendcompte de la diversite des phenomenesreligieux (entre religions, et a l’interieur dechacune d’elle).

L’organisation interne de la plupart deschapitres illustre le premier parti-pris, enintroduisant le propos par une discussiond’anthropologie generale ensuite appliquee al’anthropologie des religions(‘L’anthropologie du symbolisme’ introduitlonguement le chapitre ‘Symboles etspecialistes religieux’).

Ce lien explicite, et justifie, entre religionet culture constitue le fil rouge de l’ouvrage,annonce en sous-titre. Mais l’on regrette lasystematicite de l’approche, qui reduitsouvent la religion a une simple projection dela culture. L’ouvrage aurait a mon sens gagnea aborder les problematiques d’anthropologie

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

366 REVIEWS

generale a partir des debats d’anthropologiedes religions. En effet, le lecteur se demobilisedevant la precaution-leitmotiv precisant queles debats d’anthropologie religieuse n’offrentjamais qu’une replique des debats generauxconcernant la culture (pp. 110, 162, 172, 219,276 entre autres. . .). Sans doute est-ce ce rolede reference (d’explicateur ?) ultime attribueaux structures culturelles qui mene Eller anegliger par exemple la fonction contestataireou l’effet anxiogene des religions, pourprivilegier leur role de reponse aux besoinscollectifs et individuels (pp. 10–11).

En outre, le doute ainsi emis sur l’interetspecifique du champ religieux est renforce parl’equilibre choisi entre ethnographie ettheorie. La premiere est tres peu presente, etquasiment toujours a usage d’illustration de laseconde. Le souci qu’a l’auteur du relativismeet de ce qu’il nomme la ‘modularite’ (lareligion en tant qu’assemblage variabled’elements divers) l’incite a privilegier uneenumeration de cas ethnographiques, qui estdecevante car donnant insuffisamment dechair et d’assise a la partie theorique qui laprecede (sur les specialistes religieux, parexemple) et ne resolvant en rien la doubledifficulte terminologique et taxinomiqueposee au depart. De meme, l’usage des deux‘cas d’etude’ par chapitre n’introduitl’ethnographie qu’a la marge. Dans cesencadres d’une page chacun, Eller se contentede resumer le contexte, les configurationslocales ou la theorie d’un auteur.Contrairement a l’annonce des editeurs, lelecteur ne trouvera dans ce livre que peud’ethnographie, et aucune presentationapprofondie d’une situation religieusespecifique dans son contexte social etculturel.

Afin d’atteindre son deuxieme objectif,fonder une anthropologie des religionsmondiales contemporaines, l’auteur orienteson expose autour d’objets d’etudes (laviolence, le secularisme) permettant uneapproche transversale, qui completeidealement l’organisation thematique despremiers chapitres. Cette partie m’a pourtantnettement moins convaincu. Le chapitre surles ‘religions mondiales’, notamment, remet

lui-meme serieusement en cause, et avecraison, la pertinence de la classification, et lapossibilite ou l’interet d’etudier les religionsautrement que sous leur forme locale et/ousyncretique (p. 189). De meme, s’il estprobable que ‘le fondamentalisme religieuxcontemporain est un type de NouveauMouvement Religieux qui s’en defend’(p. 280), on aurait prefere le voir mis encontexte dans le chapitre sur les NouveauxMouvements Religieux plutot que de lire unpanorama historique succinct desfondamentalismes chretien, juif, musulman,hindou et bouddhiste.

Malgre ces critiques, je conseille lalecture de cet ouvrage, notamment pour laclarte de ses chapitres d’introduction audomaine, entreprise toujours perilleuse et, ici,globalement reussie.

CLAVEYROLAS MATHIEUEHESS and CNRS, Paris (France)

de l’Estoile, Benoıt. 2007. Le gout desautres. De l’exposition coloniale aux artspremiers. Paris: Flammarion. 454 pp. Pb.:€28.00. ISBN: 978 2 082 0498 2.

2006 saw a major shake-up of the Parisianmuseum scene as far as anthropology isconcerned. The ethnographical collections ofthe Musee de l’Homme, at the Trocadero site,were moved to a newly built museum on theother bank of the Seine, the Musee du quaiBranly, a stone’s throw away from the EiffelTower. As a consequence, the Musee del’Homme has been reduced to a shadow of itsformer self, i.e. a collection of merelyprehistoric and physical-anthropologicalexhibits, while the new, more aestheticallyoriented museum on the left bank continuesto draw large crowds since its opening to thepublic. These transformations (decided at thehighest level of the French government) didnot fail to spark vociferous protests by Frenchanthropologists at the time. Published aboutone year later, Benoıt de l’Estoile’s thoroughanalysis of the debate, its premises and itsimplications is a welcome contribution to alevel-headed understanding of the past,

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 367

present and future of museums ofanthropology not only in France, butworldwide.

De l’Estoile proposes to establish agenealogy of the various discoursessurrounding anthropological museumexhibits over the last 100 years. The 1930shold a particular interest for the author. Alarge-scale colonial exhibition opened atVincennes near Paris in 1931, while the Museede l’Homme, not only a museum, but also acentre for research and teaching, theimportance of which for Frenchanthropology cannot be overestimated, wasfounded in 1937. De l’Estoile detects someparallels between the colonial exhibition andthe new Musee du quai Branly: both set out tocelebrate the cultural diversity of mankind,and, in different ways, the exemplary role ofFrance (either as a model coloniser, or as achampion of diversity vis-a-vis real orperceived US-American hegemony). As del’Estoile points out, a simple Manichaeanvision of the colonial age will not do – thereare many complex interconnections betweenFrench colonialism and ethnology in itsinfancy; both often shared the samevocabulary and had similar scientificaspirations.

The decline of the Musee de l’Homme,perceptible from the 1980s onward, has to beseen in the context of the general crisis ofethnographical museums today. Their morallegitimacy, the criteria for the choice of theirexhibits, and their presentation to the public(and what public exactly?) have been calledinto question. Intriguingly, about 100 yearsafter Western artists discovered ‘primitive art’,the aestheticisation of the exotic Otherreturns with a vengeance. Even if art museumslike the quai Branly claim that they contributeto the revalorisation of foreign cultures,honouring their best artists in the same way asthe creative geniuses of the Western art canon,their museography creates multiple problems,as de l’Estoile points out. First, the objectsexhibited in this kind of museum are chosenthrough a Western lens, which in the case ofthe quai Branly museum leads to a preferencefor objects that can easily be classified as

‘sculptures’, while textiles or items made offeathers tend to be neglected, for instance.Second, the accompanying texts often describerather than explain the exhibits. Third, theinner architecture and the arrangement of theobjects in the museum create a mystifyingatmosphere and reinforce stereotypicalrepresentations linking ‘exotic cultures’ withcliched notions such as sensuality, dance,rhythm and harmony with nature. From thispoint of view, the Musee du quai Branly canhardly be seen as an improvement overtraditional museums of anthropology.

While thus criticising the latestdevelopments in French ethnographicalmuseography, Benoıt de l’Estoileacknowledges that the experience of theMusee de l’Homme could not be continuedas it was either. He suggests that theanthropology museum of the future ought tohave two distinct characteristics: reflexivity(representing the history of the representationof the Other, as it were) and an emphasis ondialogue (displaying the interconnections andinterdependencies between Us and theOther).

The best passages in de l’Estoile’s bookare the analytical ones; they are interspersedwith long descriptive chapters, particularly alengthy section on French ethnology in the1930s. One cannot avoid the impression thatin some respects Le gout des autres comprisestwo books in one: an analytical essayreflecting on the new Musee du quai Branlyand a history of French ethnology in relationto museums, with a particular focus on thefoundational years of the 1930s. This trulyfascinating and often insightful book wouldhave benefited from rigorous copy-editing,which could have cut down the more than400 pages and, incidentally, straightened outsome minor spelling or factual errors.

ANNE FRIEDERIKE MULLER-DELOUISAcademie d’Orleans-Tours (France)

Franklin, Sarah. 2007. Dolly mixtures: theremaking of genealogy. Durham: DukeUniversity Press. x + 253 pp. Pb.: $22.95.ISBN: 978 0 8223 3920 5.

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

368 REVIEWS

Although Dolly became famous as theworld’s first cloned mammal, which indeedlacked a proper genealogy, Dolly the sheep isnot a real ‘clone’. She is not the result of anasexual copying process, but a designeranimal of an intriguing genetic mixture: thenuclear DNA is from a Finn Dorset ewe,while the mitochondrial DNA is from aScottish Blackface, gestated by severalsurrogate sheep. Ironically, Dolly is called aclone because she is so different from all othermammals that come into being through sexualreproduction. The term ‘clone’ thus signifiesall the mixtures that set Dolly apart in herparadoxical uniqueness.

Sarah Franklin suggests thinking ofDolly as a ‘morphism, a kind of mutationalspace in which cultural and biologicalcategories, presumptions, and expectationsare warped’ (p. 27). Not only a clone, but atthe same time an ancient domestic mammal, asymbol of innocence, of subordination and ofChristian piety, Dolly the sheep is an animalthat is ‘good to think with’; especially with thetechnological transformations of classificatorysystems, categories and identities her birth hasinitiated. She is the embodiment and evidenceof a revolutionary cloning technique, as muchas she is a perfectly ordinary sheep. Dolly isboth frontier and horizon, opportunity andthreat. As the iconic animal of the twentiethcentury, she indicates cloning as an ethicalfrontier of animal–human mixtures and ofthe domestication of human cells, as muchas she points to the horizon of therapeuticpotential of stem cells in regenerativemedicine and to anticipated high profitsin the biotechnological growthindustry.

Tracing Dolly’s pedigree along thehistory of animal domestication, Franklinreveals sheep–human associations andintertwined genealogies through past andfuture, and shows that Dolly is a very Britishsheep indeed: Dolly and her revolutionarycombination of genes with its significancefor reproductive biomedicine are bothdeeply entangled in, and are the outcome of,British history of sheep breeding, ofexpanding wool markets (especially into

Scotland and Australia), of colonisation andindustrialisation.

Biology, as her argument goes, ‘is sociallyproduced, thick with specific andaccumulated histories, and always alreadyculturally mediated’ (p. 6). Dolly and hertechnique of somatic cell nuclear transferindicate the era of biological control, i.e. theability to grow animal and human cells in alaboratory dish (like bacteria). This is the eraof domestication and manipulation ofreproductive possibilities. By discussingcontagious and dead sheep, Franklin alsoshows the reverse of biological control,namely biology out-of-control disasters.Britain’s 2001 foot and mouth diseaseepidemic highlights once again the linkagesof people and sheep through their sharedgenealogies, soils, local and national identities.

Franklin thus uses sheep as a vantagepoint and as an ethnographic window into thechanging relationalities that connect animalsand humans through potentially remixed andtechnologically assisted genealogies. Shedescribes her method as genealogicalreckoning: an orientating look backward atthe specific conditions that shaped Dolly’scoming into being and – based upon a glanceinto the other direction – anticipate specificfuture trajectories.

One might have expected a broaderdiscussion of the gender aspects related to thiskind of future, and of Dolly’s implications forgender dimensions in concepts of procreationand parenthood. Nevertheless, DollyMixtures is without doubt anothermasterpiece by Sarah Franklin, to be highlyrecommended for scholars interested inexploring assemblages and mixtures of allkinds: human, animal, technological,economic, legal, scientific, medical and media.

The well written, accessible style of thebook and its carefully selected illustrationsmake these complex issues comprehensible. Itpresents astonishing insights into far-rangingrelationships between science and wider socialpractices. Furthermore, the book providesfascinating and at times delightful readingthrough eloquent puns such as theextraordinary egg-oism of Dolly’s

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 369

development (out of two egg cells), herewe-niqueness, or her kin-sheep. With clonesheep Dolly, argues Sarah Franklin,perspectives on genealogy are inevitably inneed of rumination.

EVA-MARIA KNOLLSocial Anthropology Research Unit, AustrianAcademy of Sciences, Vienna (Austria)

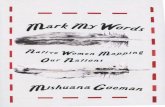

Gay y Blasco, Paloma and Huon Wardle.2007. How to read ethnography. London:Routledge. 214 pp. Pb.: €24.29. ISBN: 9780 415 32867 8.

Paloma Gay y Blasco (PGB) et Huon Wardle(HW) livrent avec How to read ethnographyun ouvrage original et reussi, dont l’objectifcentral est d’enseigner comment traiter‘ethnographic texts anthropologically’(p. 133), comme les produits d’acteurssinguliers et de milieux specifiques. Davantageque des contenus, ce sont donc explicitementdes habitudes de pensee que PGB et HWcherchent ici a transmettre. A cette fin, ilsengagent une serie de reflexions sur laconstitution des savoirs anthropologiques etsur l’identite des textes ethnographiques –leur specificite par rapport a certains genreslitteraires tiendrait ainsi a ce que lesethnographes soient tenus pour responsablesde la verite de leurs recits (pp. 195–197). Lesreflexions depassent en fait largementl’objectif initial, essentiellement pedagogique,que se donnent les auteurs. Si le livre est a biendes egards concu comme un manuel, larigueur exemplaire, la clarte et la systematicitede l’argument en font un outil intellectuelsusceptible d’interesser en fait la communauteanthropologique dans son ensemble. En effet,l’ouvrage evite a mon sens les ecueils a la foisdu post-modernisme et d’un positivisme troppeu attentif a ce que les ethnographies doiventaux ethnographes.

Centre, donc, sur la question de l’analyseanthropologique des textes ethnographiques,le livre introduit les evolutionsepistemologiques et terminologiques parpetites touches, au fil des problematiquesabordees. Chaque partie de chapitre est suivie

d’une serie de ‘summary points’ qui resumentson contenu et facilitent un usage pedagogiquede l’ouvrage. Dans la meme perspective,chaque chapitre se termine par une conclusionsynthetique (entre un demi-page et une pageselon le chapitre) et, de facon plus originale,par un court texte d’anthropologie (cinq asept pages), veritable exemple-exercice surlequel des questions sont posees, invitant parexemple le lecteur, selon le theme du chapitre,a y deceler les usages explicites et implicites dela comparaison, les objectifs poursuivis parl’auteur, les types d’arguments utilises. . .

Le premier chapitre est consacre a lacomparaison, puisque celle-ci est constitutivede l’ethnographie dans la mesure ou lesethnographes utilisent ‘themselves and theirknowledge of their own society as a startingpoint for understanding and representingothers’ (p. 17): la place occupee et lesquestions posees a cet egard par le travail desethnographes travaillant dans leur propresociete sont peut-etre trop vite passees soussilence ici, puisque l’ethnographie est avanttout presentee, dans l’introduction et laconclusion, comme ‘the study of others’(p. 5), laquelle enrichit les discussions ‘aboutwhat it means to be human’ (p. 3). Le chapitren’en reste pas moins valable, exposant avec untalent pedagogique certain des questions-clescomme le caractere inseparable desdescriptions et des perspectives theoriques quiguident la pratique descriptive, ou les usagesethnographiques multiples des comparaisons(a des fins de singularisation ou degeneralisation, par exemple).

Les contraintes de place inherentes a cetype de compte rendu obligent a passer plusrapidement sur les chapitres suivants. Ainsi,les deuxieme et troisieme chapitres montrentla place essentielle tenue par les operations decontextualisation dans toute ecritureethnographique, puis comment lesethnographies construisent a partir del’experience quotidienne, par selection etabstraction, des systemes de relations et desschemas de pensee. Le quatrieme chapitremontre l’usage crucial que les ethnographesfont de descriptions du quotidien, lesquellesoccupent souvent un role fondamental dans

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

370 REVIEWS

l’etayage empirique d’analyses de portee plusgenerale. Le cinquieme chapitre montrecomment les ethnographies se positionnenttoujours, implicitement ou plus explicitement,par rapport a des debats anthropologiques encours, et comment l’ethnographie est en cesens fatalement relationnelle: elle s’inscritdans un champ intellectuel precis. Lesethnographies toutefois ne s’inscrivent passeulement dans un champ intellectuel maisaussi dans un contexte social, culturel,politique, plus large, lequel contribueegalement a les faconner. C’est l’objet dusixieme chapitre. Le ‘anthropological canon’(p. 129) evolue ainsi au fil du temps.L’influence du feminisme sur celui-ci, parexemple, est aujourd’hui manifeste(pp. 129–133).

La reflexion se poursuit dans les septiemeet huitieme chapitres, les auteursd’ethnographies emergent ‘out of specificconstellations of relationships in the field andin the academy’ (p. 155). Sont alorsnotamment evoques le role des prefaces et desremerciements, avec la place qu’y occupent‘academic mentors’ et ‘intellectual heroes’(p. 164), ou encore la facon dont semanifestent les ‘scholarly allegiances’ (p. 171)– par le biais, par exemple, de la mobilisationde certains concepts. C’est pour ainsi dire lafonction politique du jargon qui est evoquee.Enfin, PGB et HW degagent en conclusiontrois aspects de l’ethnographie qui cohabitentaujourd’hui, a savoir l’ethnographie commefait, comme provocation et comme savoirliberateur ‘in a generalised conversation aboutbeing human’ (p. 195).

JOEL NORETFonds National de la Recherche Scientifique(Belgique)

Hovanessian, Martine. 2007. Le liencommunautaire. Trois generationsd’Armeniens. Paris: L’Harmattan. viii +319 pp. Pb.: €27.50. ISBN: 978 2 29602869 2.

This book, which was written in 1992 andrepublished fifteen years later (without any

addition or modification apart from aneight-page preface), deals with the Armeniancommunity of Paris and analyses the‘dialectics of loss and reconstitution’ (p. 303)from an anthropological point of view. Itillustrates the different preoccupations ofthree generations: the first generation iscomposed of the ‘orphans’, who lost theirfamilies during the 1915 genocide and arrivedin France under very difficult conditions. Apart of the book is structured, in fact, aroundthe narrative of Haroutioun, an informant ofthe first generation born in 1910 in Stanoze(30 km from Ankara) and a direct witness tothe persecution between 1920 and 1923. Thesecond generation, whose social integrationand memories are also examined in the book,is made up of those born in the 1930s, whocompose 90% of the members of theassociations in Issy-les-Moulineaux, a suburbof Paris, and have participated through theireconomic success – mostly through the textilecraft industry – in the production of the imageof a well-integrated community (p. 215). Thethird generation, born in the 1950s, as theauthor tells us, is very little involved inassociative life and tries to negotiate (in apersonal, hesitating and sometimes artisticway) its belonging to the Armeniancommunity and its sense of identity. Thissame generation even accuses their parents ofabandoning their Armenian specificity.

The author constantly reminds us notonly of the generation gap inside thecommunity, but also of the division caused byreligious options (between those who belongto the Evangelical Church, the CatholicChurch or the Apostolic Church and thosewho have chosen to be agnostic) and bypolitical stances (principally for or against thepolitics of the former Soviet Union, underwhose system of government the Republic ofArmenia was established, and more recentlytoward Armenian terrorism, which took formbetween 1975 and 1985). As the authorremarks, ‘it seems that the Armenians have avery weak inclination for unity. To theuninterrupted dismemberment of theArmenian nation a certain localism is added’(p. 31). This ‘constant pulverization of the

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 371

ethnic paradigm’ (p. 30) is illustrated byexamples of minor importance such as thefighting between Armenian children living inthe rue de De and those in the boulevardRodin (p. 80); and the stabbing of adult menin the rue de la Defense, where lived rural anduneducated Armenians who didn’t manage tofollow the general social ascension of theircompatriots (p. 82). But events of majorgeopolitical interest, such as the arrival of newArmenian immigrants in France fleeing fromLebanon and Syria between 1975 and 1980,are also linked to this fragmentation of thecommunity. Each one of these groups ismarked by a different historical experienceand carries cultural specificities that thealready established French-Armenians aremore or less ready to criticise. This Frenchcommunity, in its variety, is on the horns of aserious dilemma: how to position itselftoward two rival styles of life, the Orientaland the Occidental one.

From the beginning, the authorestablishes a constant dialogue betweenanthropological analysis and psychoanalysis(p. 9 and p. 182ff), with citations from Lacanand Freud. Reference is made to the ‘morbidatmosphere’ that sometimes characterises thefamily cell, and to the parental relations thatseem to be fixed on the fact of castration(evenement castrateur), that is the persecutionduring the genocide and the corporal marksleft on the mother’s and the father’s bodies(p. 166). The vain quest for unity is said to be‘obsessional’ (p. 102) and utopian, and thesecond generation of Armenians to be themain heirs of ‘this narcissistic wound’(p. 178). According to a female informantof the second generation, school, for her, was‘a cold place’, where no love was given butwhere one could find refuge: school was notcharged with traumatic memories of slaughteras home was (p. 279). Armenian terrorism isalso described as being ‘psychotic craziness’(p. 278). All these terms suggest the existenceof a ‘pathological memory’, which affects themembers of the community and the successivegenerations. The reader cannot but formulatethe hypothesis that this book is proposed asthe starting point of a ‘treatment’ against this

(supposedly inherited, inevitable and ethnic)pathology. A more general criticism, whichneeds to be made, concerns the absence of aninternational bibliography, which would haveallowed the development of a comparativepoint of view. The bibliography is exclusivelyFrench, a fact that limits the scope of analysis.Beside this criticism, the book succeeds notonly in giving us a multi-vocal image of theFrench-Armenian community and itsevolution through time, but also in presentingthe (initially rural) immigrant as an activeurban agent.

KATERINA SERAIDARILaboratoire Interdisciplinaire SocietesSolidarites Territoires, Toulouse (France)

Maynard, Kent (ed.). 2007. Medicalidentities: healing, well-being andpersonhood. New York and Oxford:Berghahn Books. ix + 162 pp. Pb.:£15.00/$25.00. ISBN: 1 84545 100 7.Hb.: £30.00/$50.00. ISBN: 1 84545038 8.

Sur la couverture de l’ouvrage se trouve leportrait d’un homme masque, mais il n’y a pasde doute sur son identite professionne c’est unchirurgien. Du point de vue anthropologique,les problemes commencent la ou semble seclore la reconnaissance spontanee des signesexterieurs d’une profession, d’un genre etd’une categorie d’age. Mais le conceptanalytique d’identite, qui sert ici de categorieunificatrice, permet-il de bien degager lesprocessus en jeu?

L’objectif de Kent Maynard, le directeurde publication et l’organisateur d’un seminairesur ce theme a l’universite d’Oxford en 2003,est d’explorer a partir de cette question undomaine particulier, le champ de la sante, enreunissant des travaux depassant les clivagesdisciplinaires (histoire, anthropologie,sociologie), geographique (du Cambodge ala Grande-Bretagne) et institutionnelle(des medecins generalistes aux devinszoulous).

La force du concept d’identite est, selonlui, d’embrasser a la fois la dimension

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

372 REVIEWS

individuelle et collective, l’appartenance a ungroupe comme l’experience. Plus loin, il endistingue les trois echelles: l’identitesubjective, le statut social et l’identitecollective. Reprenant une formule de Marx etEngels – nous sommes ce que nous faisons – le‘lieu’ de l’identite est alors situe dans l’atelierde sa fabrication, voir dans le faire lui-memeou le corps qui le met en œuvre. Donc, lesagents de sante, se distinguant par une classed’activite, faconnent une identite particuliere.Or, le lecteur ne comprend pas tres bien legain intellectuel a enregistrer la variabilite desidentites, plutot qu’etudier un processusgeneral qui rende intelligible la differenciationou non d’une sphere d’activite et les strategiesde distinctions de ces principaux agents.Aussi, ce qui semble gagne par la formidableextension du concept d’identite, se perd-il ensubstance sur le plan anthropologique par unefaible comprehension.

Au fond, le concept d’identite ressembleici a une reponse dont on n’aurait pasclairement formule l’ensemble des questionsqu’elle pretend pourtant clore simultanement.Plus largement, s’agit-il d’un conceptscientifique? Son succes sociologique n’a eneffet d’egal que son succes social. Longtempsau centre d’une lecture denonciatrice etnominaliste de la construction des identites, onla trouve ici au service d’une lecture banaliseeet realiste de la production des identites. Or, setrouvent meles dans la problematique aumoins trois processus de reconnaissancesociale tres differents. Entre la (i) production etla perception de l’image sociale d’un medecin(une production discursive et sa reception),(ii) la logique de son appartenance a uneprofession ou a un segment professionnel(une socialisation individuelle) et (iii) sonidentification par l’Etat ou une instancecollective de legitimation (une attributioncategorielle), il n’y a rien de commun.

C’est dans ce cadre analytique que peutmieux se comprendre l’interet des sept articlesreunis dans ce volume. Le premier articled’Anne Digby, dont l’analyse comparativerepose sur un corpus de lettres etd’autobiographies de medecins generalistes en

Grande-Bretagne et Afrique du Sud au debutdu XXeme siecle articule la problematique (i)qui est de l’ordre de l’etude classique desrepresentations et de la rhetoriqueprofessionnelle, (ii) qui donne une idee de lavie de ces medecins et (iii) qui montre l’impactdes transformations des politiques de santesur la profession. Sans ces distinctions claires,la lecture de l’article est rendue tres difficile.Cette remarque vaut aussi pour le texte deIng-Britt Trankell et Jan Ovesen, lequel portesur l’etat de l’offre de medicaments auCambodge et ressort clairement – meme si leconcept manque – de l’analyse du pluralismetherapeutique, puisqu’il s’agit de rendrecompte de la trajectoire des consommateurs etla reconnaissance des recours possibles entrepharmacien, distributeur de medicaments etautres agents de sante. C’est aussi le processusqu’analyse Kent Maynard dans sacontribution en montrant plus specifiquementcomment les nouveaux ‘docteurstraditionnels’ au Cameroun se distinguent des‘medecins indigenes’ en suivant une formationde professionnalisation de la pratique deguerison. Gina Buijs analyse le statut de devinzoulou qui peut fournir un role socialacceptable pour les homosexuels et leslesbiennes. Ce sont les processus (ii) et (iii)qui dominent ici l’analyse comme dans letexte autobiographique d’Elisabeth Hsu quirelate sa socialisation au metier d’acuponcteuren forgeant le concept ‘d’experienceparticipante’. Le volume se termine sur lesetudes de Janette Davies et Jenny Littlewoodqui portent sur la legitimite professionnelle etles formes de competence de deux activites desante (auxiliaire de soin et sage-femme) auxconfins du monde medical.

Malgre mes reserves sur le conceptd’identite et la confusion qu’il comporte sur leplan analytique, le volume reunit des etudesde cas qui meritent d’etre lues comme autantde contributions a la sociologie desprofessions medicales et a l’anthropologiede la sante.

SAMUEL LEZEEHESS, Paris (France)

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 373

McAra, Sally. 2007. Land of beautifulvision: making a Buddhist sacred place inNew Zealand. Honolulu: University ofHawai’i Press. xiv + 210 pp. Hb.: $45.00.ISBN: 0 8248 2996 4.

The academic study of Buddhism hasundergone several interesting developmentsin recent years. One of them is a blurring ofdisciplinary and methodological borderswhere scholars coming from a background inAsian or Religious Studies engage withlong-time fieldwork and ethnographic writingwhile anthropologists with an interest inBuddhism often find it necessary tocomplement participant observation andface-to-face encounters with various forms of‘polymorphous engagements’, thus expandingthe notion of fieldwork. Another trend is thegrowing interest in emerging forms ofBuddhism outside Asia. ‘Western BuddhistStudies’, with a double focus on the religiouslives of immigrant communities as well asWestern convert Buddhists (including theoccasional overlap), has now becomeestablished as a lively, inter-disciplinary fieldof research in its own right. Finally, a numberof researchers have also come out of the closetas Buddhist practitioners. Quite a few of themhave also, in a spirit of seasoned reflexivity,managed to make good scholarly use of theirfirst-hand experiences, thus showing therelevance of the ‘halfie’s’ perspective in thestudy of religion.

The different volumes in the Topics inContemporary Buddhism series brought outby University of Hawai’i Press have providedgood examples of these trends, and all of themare present in its most recent addition: SallyMcAra’s Land of Beautiful Vision. Thesubject of this study is the establishment of aretreat centre and the subsequentconstruction of an elaborate stupa in ruralNew Zealand by members of the globalorganisation Friends of the Western BuddhistOrder (FWBO). The author’s choice of fieldmakes it possible for her to investigate severalinteresting but somewhat neglected aspects ofcontemporary, globalised Buddhism.

As this field is still dominated by NorthAmerican material, studies like this have anintrinsic value – not the least as they show that‘Western Buddhism’ is a more heterogeneousphenomenon than the popular image of an‘upper middle way’ suggests. Land ofBeautiful Vision adds to the ethnographicarchive an account of a complex,post-colonial situation where convertBuddhists find themselves forced to come toterms not only with their Judeo-Christianheritage, but also a web of political, naturaland indigenous spiritual forces. The authormakes use of familiar tropes like bricolage,creolisation and conjunctures in her analysis ofan indigenisation process that is not alwayssmooth. More interesting, at least to thisreviewer, is McAra’s focus on the importanceof material culture (exemplified by the stupa)and the sense of place in the establishment (orinvention) of a religious tradition.

The greatest strength of this ethnographymight be in how it challenges certain commonbut oversimplified notions of ‘ProtestantBuddhism’. This concept was originally usedto describe developments in colonial Ceylon,but ‘Protestant’ or ‘modernist’ Buddhism (theconcepts are often treated as synonyms) havealso been useful analytical tools forunderstanding reform movements in otherparts of Asia, as well as the reception ofBuddhist ideas and practices in Europe andthe United States. Like other ideal types,‘Protestant Buddhism’ has a certain seductiveappeal, and one could argue that it has beenonly too ‘good to think with’. True enough,some Buddhist practitioners, and a fewscholars, still celebrate the idea of arationalistic and thoroughly sanitised religion(sometimes glossed as a ‘science of mind’),stripped of ritual elements and other‘superstitions’. There are also several goodreasons why such attitudes could be called‘Protestant’. The question is, however, howcommon such sentiments are.

Detailed ethnographic accounts, such asthis one, present us with a more complexpicture. The readiness by which manyWestern converts embrace traditional forms

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

374 REVIEWS

of Buddhist ritual (devotional as well asmeditative) and the creative, eclectic way newones are invented, suggest that contemporary,Western (or global) Buddhism as a whole issomething quite different than the thoroughlyanti-ritualistic, iconoclastic, antinomian,psychologising and individualisticquasi-religion it is often imagined to be.Having a branch of the FWBO illustrate thispoint is felicitous as this organisation is oftenseen as a paradigmatic example of Western‘Protestant Buddhism’. In this respect, McArasuccessfully accomplishes her purpose ofpresenting a nuanced discussion, rather thananother set of simple (or over-simplified)typologies, thus affirming the value of anethnographic approach in this field.

PER DROUGGEStockholm University (Sweden)

Mutongi, Kenda. 2007. Worries of theheart. Widows, family, and community inKenya. Chicago: Chicago University Press.xii + 256 pp. Hb.: $50.00. ISBN: 0 22655419 8.

Born in an independent Kenya, KendaMutongi came back to her fieldwork after10 years of living in the US. To her surprisethe women she met wanted to have back aformer life style where men were supposed totake care of the widows and their families,solving their worries of the heart (KehendaMwoyo).

Usually the anthropological literaturewould deal with a case like this one as aleviratic problem, therefore isolating the‘tribal’ life of the Maragoli in order to contrastit with other Luyia groups. Mutongi rejectsthis traditional path. Comparing her ownpersonal memories with the perspective of oldvillagers, along with information obtainedthrough documental research, the authorreveals the actual value of a reflexiveethnographic work, far beyond what isobtained in the archives or through oralhistory alone.

A reader eager to understand present-dayKenya finds in Mutongi’s book one century

of historical experiences, retraced through thelife stories of widows whose husbandsdisappeared in conflicts similar to those wenow see from a distance. The first part of herbook recovers the colonial policy and itsconsequences. Here the author unearthsdifferent narratives (traveller’s accounts,missionaries’ diaries, official documents),showing us that the process of conversion waspossible in so far as the missionaries acceptedthe practice of widow inheritance. Mutongidemonstrates that this concession was the firststep to disseminate among the localpopulation notions about private property.Christians were the ones who understoodland as private individual property and not assomething owned by lineage or clan.Convinced by the missionaries, the newChristians evicted their neighbours in orderto establish idyllic Christian villages (iliini).However, the same private property allowedthe sale of the land and the inevitabledisintegration of the Christian Villages.Therefore the new order was ruled by ‘legalbureaucracy that they could not understandor trust’ (p. 94).

The second part deals with the FamilyLife, another element fundamental forunderstanding the initial dilemma opposingthe colonial order nostalgia and the defence ofcontemporary democratic values acquiredafter independence. To ‘escape the ache andindignity of manual labour’ (p. 101), manyparents, most of them widows, wanted to givetheir sons a better education. Here again thewhite missionaries played an important role,providing bursaries to the students.According to Mutongi the experiencesoutside the village, especially the degradingcolonial policies, didn’t help the sons achievethe expectations of their mothers. Both –mothers and sons – agreed that taking care ofa woman, especially of widows, was anecessary condition to be a proper man. Bythe same token these men wanted to marrywell-educated girls, but they also could notcope with the ambivalent progressive woman.

In the mid-1940s technical reformsintroduced in African courts by the colonialgovernment opened a new arena of

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 375

negotiation for women and theircontemporary problems, like divorce, forexample. Re-editing or reinventing the modelof Maragoli masculinity, the ‘men in thecourts had assumed familiar, and proper,gender roles’ (p. 158) and the courts began tobe considered ‘a supportive institution’(p. 159). Gradually the small community wasbeing replaced by the laic structures of anemergent State.

The postcolonial promises and thesubsequent disappointments are the mainissues of the third part of the book. Alongwith the structural shifting, a new languageemerged in Kenya. Widows and other people,instead of calling themselves poor suffering,claimed their land back as citizens of universalrights and duties, being therefore obliged ‘toarticulate their grievances in terms of the lesspersonal and more political new language ofcitizenship’ (pp. 167–71). Despite the hopeinvested in them, the newly elected blackleaders tended to favour local elite members.The widows felt betrayed. Actually theNation State in formation was, from theirpoint of view, a trap, dominated by Swahilispeakers, by Kikuyu authorities ‘full ofukabila (tribalism)’ (p. 186), where the ruralpoor had no chance to have their pleasfulfilled.

The author tries to find an answer to aquestion I’m sure many anthropologists askthemselves during their research: how couldour hosts in the field miss the colonial order?She tries to understand such statements ‘evenif they contradict our own personal,intellectual, and political thinking’ (p. 198). Inorder to take the evaluations our interlocutorshave about their own history seriously, theanthropologist needs more than just a fixedscheme. Kenda Mutongi taught us animportant lesson in which political concernand ethnographic precision come togetherwith epistemological seriousness.

ANTONADIA BORGESUniversidade de Brasılia (Brazil)

Muller, Birgit. 2007. Disenchantment withmarket economics. East Germans and

western capitalism. New York and Oxford:Berghahn. ix + 244 pp. Hb.: $75.00. ISBN:1 84545 217 8.

The twenty years since the fall of the BerlinWall have seen a number of works dealingwith the change from state-Communist tomarket-capitalist regimes. Birgit Muller’sDisenchantment with Market Economics isone of these. Originally published inGermany in 2002, it is the first of a series oftranslations into English of material publishedin other languages, organised by the Societyfor the Anthropology of Europe of the AAA.

Muller presents that change from theperspective of production workers and somemanagers, originally in three enterprises thathad operated in East Berlin. Using interviewsafter the fall of the Wall, complemented byparticipant observation, she collected theirmemories of work in the GDR. One of thoseenterprises survived die Wende, unification,and she followed workers in it to understandtheir experience of and reaction to thecapitalist system they now confronted. Theresult is a book that describes the changingsituation of work and orientation of workersthat occurred with the shift from plan tomarket.

The first and longest part of the book isbased on people’s descriptions of enterpriseorganisation and operation in the GDR, whenwork revolved around meeting and evadingthe plan. By 1980 central planning confrontedenterprises and their workers with scarcity. Tosecure supplies, managers developed links topeople in enterprises that produced what theyneeded. To get the most out of ageingmachines, workers and engineers cooperatedand innovated to keep the machine runningand to fit production to what the machinescould do. Scarcity also led to indifference todemand: there was no shortage of buyers forwhat the enterprises produced. Workers alsohad to cope with efforts to make sure thatthey were good socialists, participating in theactivities of their workers’ brigades andreporting on them in brigade diaries. As withthe plan, workers responded with a mixtureof compliance and evasion. A brigade outing

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

376 REVIEWS

to a May Day parade, for instance, couldmean a nip down a side street for a beer;entries in the brigade diaries could, with care,be repeated year after year.

The second part of the book is concernedwith die Wende, the period between theeffective dissolution of the GDR and theunification of Germany. Workers foundthemselves increasingly able to criticise theold regime publicly, but they foundthemselves in a confused and confusingsituation as the enterprises that they hadthought their own became private property.As well, workers and managers did not realisethe consequences of the end of scarcity. Orderbooks suddenly emptied; instead of beingcourted by buyers they had to court them,and they were not very good at it. Dislocationand uncertainty weakened the older solidaritythat had united workers in their commonefforts to cope with the plan, wage differencesincreased and workers fearful of losing theirjobs confronted an increasingly powerful andaloof management. This was made worse byworkers’ lack of understanding of howcapitalism worked.

That understanding increased sharply asunification proceeded, the topic of the finalpart of the book. It focuses on workers in theone enterprise that survived, bought by theEuropean subsidiary of an Americanmultinational. That company ‘empowered’workers, in two senses. Firstly, it providedthem with relatively little direction: thedetailed production plans of the old orderwere replaced by rough guidelines. This gaveworkers flexibility, but only within the overallconstraint of steady demand for increasingproductivity. Secondly, it defined failure asthe fault of workers, who had not takenenough steps to assure that they couldcomplete their tasks on time. Those who wereof the right temperament flourished, thoughperhaps cynically. The rest tried to survive inan environment both alien and hostile.

I have omitted much that Mullerdescribes, especially her discussion ofdifferent aspects of the complex relationshipbetween those from the West, Wessis, andthose from the East, Ossis. That is because

they are secondary to what seems her centralconcern, the ways that sets of workersconfront and seek to deal with the constraintsof the system in which they operate. In theGDR, constraint appeared to come from planand party; after die Wende constraintappeared to come from management, whichclaimed to be constrained by competitivecapitalism. As Muller shows in this interestingand detailed, if somewhat depressing, book,these two systems constrained workers indifferent ways. This produced different sortsof work experience and orientation, asworkers under both pursued a mixture ofevasion and compliance.

JAMES G. CARRIERIndiana University (USA) and OxfordBrookes University (UK)

Ozyurek, Esra. 2006. Nostalgia for themodern: state secularism and everydaypolitics in Turkey. Durham and London:Duke University Press. xii + 227 pp. Hb.:£56.00. ISBN: 0 8223 3879 3.Pb.: £13.99.ISBN: 0 8223 3895 5.

Esra Ozyurek nous livre une analysedidactique de la maniere dont une ideologied’Etat, le kemalisme, fait son entree dans ledomaine prive. Ces dernieres annees, denombreux citoyens formulent en effet leurattachement aux fondements secularistes de laRepublique de Turquie a travers la manieredont ils organisent leur espace domestique ourelatent leur histoire de vie, exprimant ainsileur ‘nostalgie pour la modernite’. Enadherant volontairement a ces principes, ils lesdefendent de l’accusation d’avoir ete imposespar un Etat autoritaire, et leur conferent unelegitimite accrue. Cette analyse, qui offre unelecture stimulante de la reconfiguration desfrontieres entre spheres privee et publique,suscite de nombreuses reflexions.

L’utilisation des categories n’est pastoujours convaincante: des oppositionsideologiques artificielles sont parfoisexagerees pour finalement etre nuancees.Ainsi, l’ouvrage oppose deux logiques,etatique et de marche, avant de conclure que

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 377

le ‘kemalisme nostalgique’ navigue entrecelles-ci et que les domaines de l’Etat, de lasociete et du marche ne sont pasmutuellement exclusifs (p. 148) – ce qui a dejaete montre par bien des etudes et aurait duconstituer le point de depart de l’analyse, etnon la conclusion. Ainsi, l’auteure continue autiliser des categories qu’elle deconstruit. Bienqu’anthropologue, elle semble donc prise dansle piege des mots, reifier les categories –comme celle de ‘modernite’ – et omettre parmoments d’en distinguer les usages emic etetic. Il aurait ete utile d’analyser les logiquessous-jacentes a la production et a l’entretiende ces oppositions.

Ainsi, l’auteure identifie le liberalisme –qu’elle semble considerer comme une realitecoherente et homogene – comme ‘drivingforce’ derriere les phenomenes observes.Cependant, elle n’explique pas comment celiberalisme opere concretement. Lesindications sociologiques sur les initiateursdes expositions ou des commemorationscelebrant les premieres annees de laRepublique sont insuffisantes – unesociographie plus detaillee des cadres du TarihVakf aurait permis de mieux apprehenderleurs positionnements. D’une manieregenerale, la question de l’agency aurait merited’etre traitee de front: les kemalistesprovoquent-ils vraiment des changements deregistres de justification (p. 150), ous’adaptent-ils seulement a des evolutionsqu’ils ne maıtrisent pas?

Par ailleurs, la nouveaute des evolutionsetudiees semble parfois exageree: l’auteureparle de ‘new kinds of politics’, qui rendraientdesormais necessaire d’analyser la politique endehors de l’Etat. Cependant, les frontieres del’Etat n’ont jamais ete nettes, et l’Etat et lapolitique n’ont jamais ete co-extensifs, commele montre par exemple une lecturefoucaldienne des relations interpersonnelles(Meeker 2002). De meme, l’intimite a etepolitique bien avant les evolutions decrites –meme si elle n’etait pas consideree commetelle –, ainsi que le suggerent les travaux surl’usage de la pilosite comme symbolepolitique (Delaney 1994). Ainsi, l’argumentselon lequel ‘avant’ le kemalisme n’avait pas

d’existence dans la sphere privee souffre dufait que des sources de meme nature que pourles annees 1990 ne sont pas disponibles pourles annees 1930. On pourrait en effet suggererque la dimension privee de la relation a Kemaln’est pas si neuve que l’affirme l’auteure,partant du presuppose selon lequel lekemalisme est par definition public et produitpar l’Etat. La jeune Republique avait en effetcontribue a personnaliser la relation, commele montre le choix du patronyme ‘Ataturk’.Dans ces conditions, comment dissocier cequi est lie a de reels changements, de ce quireleve avant tout d’evolutions du regard?Ainsi, pourrait-on interpreter la privatisationde l’attachement au kemalisme comme laresultante de l’evolution des formes dejustification, le libre arbitre etant devenu laprincipale garantie de legitimite publique.

Enfin, on peut regretter que l’auteure nemette pas le kemalisme nostalgique en relationavec d’autres formes de nostalgiecontemporaines, comme celle,patrimonialisante, portant sur la vievillageoise (Fliche 2005). Une telle perspectivepermettrait de mieux cerner les specificites dela nostalgie kemaliste, au-dela d’unchangement general de la relation au passe,et d’en tirer des enseignements plusspecifiques.

Pour finir, quelques erreurs factuellesnuisent a la credibilite de l’expose: entreautres, le traite de Lausanne a ete signe en1923 et non en 1924 (p. 70); la conferenceHabitat n’a pas eu lieu en 1993 (p. 134) maisen 1996; l’apparition des chaınes de televisionprivees ne date pas du milieu des annees 1980(p. 132), mais du debut des annees 1990. Cesremarques ne sauraient faire oublier le grandinteret de cet ouvrage qui ouvre de nouvellesperspectives stimulantes.

ReferencesDelaney Carol. 1994. ‘Untangling the Meaning

of Hair in Turkish Society.’ AnthropologicalQuarterly 67 (4): 159–172.

Fliche, Benoit. 2005. ‘Hemsehrilik and the vil-lage: the stakes of an association of for-mer villagers in Ankara’, European Jour-nal of Turkish Studies, Thematic Issue

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

378 REVIEWS

N◦2, Hometown Organisations in Turkey.http://www.ejts.org/document385.html

Meeker, Michael. 2002. A Nation of Empire.The Ottoman Legacy in Turkish Modernity,Berkeley: University of California Press.

ELISE MASSICARDCNRS, Paris (France)

Sahadeo, Jeff and Russell Zanca (eds.).2007. Everyday life in Central Asia: pastand present. Bloomington: IndianaUniversity Press. 401 pp. Pb.: $24.95.ISBN: 978 0 253 21904 6. Hb.: $65.00.ISBN: 978 0 253 34883 8.

The editors have succeeded in presenting acollection of essays which describe thecomplexities of everyday life in a region witha dramatic history. The focus on everyday lifehighlights alternative perceptions, revealingSoviet influences and changes sinceindependence. The contributions to thisvolume provide a glimpse into a region that isreassessing its history, introducing‘traditional’ values, and what this means.

The book contains 23 essays, dividedinto six sections, of which I am only able tocomment on a few. In the first section, ScottLevi provides a short regional history,examining the political forces that shaped it.This provides a reference to the mix ofhistories and traditions examined in thefollowing essays.

The second section examines communitylife, people’s relationships and how peopleinteract with their surroundings. AdrienneEdgar, for example, provides a historicalsnapshot of a Turkmen camp, tracing the dailyexperiences and obligations of a young manand his new bride. Morgan Liu’s essayexamines the ‘traditional’ and Sovietcharacteristics of Osh, Kyrgyzstan and howthis shapes people’s perception of the city andrelationships in independence.

The third section focuses on gender.Several essays examine Soviet attempts toestablish gender equality, demonstrating thatwhile women received education and wereincluded in the workplace, they were still

limited by family responsibilities and socialopinion. Through detailed archive work,Douglas Northrop illuminates Soviet attemptsto liberate Uzbek women from the veil, whichofficials viewed as a sign of patriarchal andreligious submission. In the 1920s, somewomen unveiled, but for many, communitypressure forced women to continue wearingthe veil. Northrop notes that in Uzbekistansome women still wear veils, expressing theirnational and religio-cultural identity, and howthis inscribes gender relations into politics.Other essays examine changing genderperceptions since independence. GretaUehling discusses various hierarchies imposedon women, and how these reinforce notionsof masculinity. During a dinner with a local‘strongman’ in Tajikistan, Uehling recounts anumber of toasts which established a ‘natural’gender order delineating their roles, whilealso recognising modern views supportingwomen’s role in constructing a new Tajiksociety.

The next section examines hospitality,food, music and public celebrations. PaulaMichaels recounts how her idea of a simplebirthday party feast horrified her Kazakhlandlady, opening a discussion on the properforms of hospitality and the kinds ofpreparation necessary. Russell Zancaexamines how fat is prized in Uzbek cookingfor the taste it adds to food and for creating adistinctive culinary style. This is an insightfulview into the importance placed on food,but will turn the stomachs of the healthconscious.

Section five examines howSoviet-constructed systems of education,welfare, language and borders have beenreinterpreted in independence. ShoshanaKeller examines how Soviet-influenced focuson nationalism has created contemporarynotions of ‘Uzbekness’. The story of twoyoung girls finishing high school illustrateswhat prospects children now face based on anationalist-orientated education system miredin corruption. Madeleine Reeves discusseshow internal Soviet borders becameinternational borders and the effect this hashad on people in the Fergana Valley. A

C© 2008 European Association of Social Anthropologists.

REVIEWS 379

personal account of the difficulties of crossingseveral borders reveals how travel has beenreduced and information stopped. Reevesargues that globalisation has not facilitated theexchange of information, travel orconnections, but has had the opposite effect,cutting people off from one another.

The final section focuses on religion andreligious practices. David Abramson andElyor Karimov analyse multiple religioustraditions from more than 2,000 sacred sites inUzbekistan. The way people understand theirreligion and practice it daily may not alwaysconform to the state’s model, but revealsmuch about social interaction. SebastienPeyrouse discusses the Christian minority.Small churches suffer from a variety ofproblems: they struggle against the OrthodoxChurch’s attempt to control the region’sChristians and encounter administrative andpolitical pressures. The various ways peopleinterpret this, and work around it, provides afascinating insight into a growing group.

This book contains important materialon a region that is often limited to discussionsof terrorism, energy resources or failingstates. The decision to limit theoreticaldebates makes the book accessible to anon-specialist audience. However, it wouldhave benefited from including more localauthors. For example, life narratives of localauthors would have added complexity tounderstandings of the everyday. Overall, thisis an excellent introduction to a fascinatingregion, which is changing rapidly andreinterpreting its Soviet past.

DAVID GULLETTEUniversity of Cambridge (UK)

Sillitoe, Paul (ed.). 2007. Local science vs.global science: approaches to indigenousknowledge in international development.New York and Oxford: Berghahn. xi +288 pp. Hb.: £80.00. ISBN: 1 84545 014 0.

Paul Sillitoe introduces this edited volume of13 articles by 24 authors with a workingdefinition of science that would comfortablyclassify mountaineers as scientists (p. 3).