Guest workers' programs: H-2 visas in the United States

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Guest workers' programs: H-2 visas in the United States

Papeles de Población

ISSN: 1405-7425

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México

México

Trigueros Legarreta, Paz

Los programas de los trabajadores huéspedes: las visas H-2 en Estados Unidos

Papeles de Población, vol. 14, núm. 55, enero-marzo, 2008, pp. 117-144

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México

Toluca, México

Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=11205506

How to cite

Complete issue

More information about this article

Journal's homepage in redalyc.org

Scientific Information System

Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal

Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative

104

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

Paz Trigueros LegarretaUniversidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Azcapotzalco

Resumen

En este artículo se hace un análisis de las visaspara los trabajadores temporales con bajacalificación en Estados Unidos: las H-2A y lasH-2B; sus diferencias con aquéllas enfocadas alos trabajadores calificados, y las formas enque se han aplicado en diversos periodos.Primeramente se describen los programas delos trabajadores temporales en ese país, asícomo la legislación relacionada con lostrabajadores no inmigrantes. Posteriormente seanalizan los programas H-2, sus característicasprincipales, ramas económicas en las que seutilizan, número de participantes y países deorigen, así como estados a los que se dirigen.Se termina con una evaluación de susbeneficios y limitantes, poniendo especialatención en la experiencia de los trabajadoresmexicanos.

Palabras clave: visas, legislación migratoria,trabajadores temporales no calificados,migrantes mexicanos, política migratoriaestadunidense.

Introduction

T

Abstract

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in theUnited States

In this article an analysis of the H-2A and H-2B visas for low-qualified temporary workersin the United States is made; their differencesfrom those of qualified workers, as well as theways in which they have been applied indifferent periods. Firstly, the programs oftemporary workers in this country and thelegislation related to the non-migrant workersare described. Later, the H-2 programs, theirmain characteristics, the economic brancheswhere they are used, number of participantsand their country of origin are analyzed,including the states they head to. The articleconcludes with an evaluation of their benefitsand limits, paying special attention to theexperience of Mexican workers.

Key words: visa, migratory legislation, non-qualified temporary workers, Mexicanmigrants, migratory policy, North Americancitizen.

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas inthe United States

he programs of guest workers have become important in developedcountries as they complement the domestic labor offer. According to thereport by OECD in 2005, between 1992 and 2000, the number of

seasonal workers in the United States grew four times, in Australia it grew threetimes and in the United Kingdom it was doubled. Likewise an important flow ofthis sort of laborers has been seen in many European countries, even thosetraditionally catalogued as ejectors, this is the case of Spain, Greece, Ireland, Italy

105 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

and Portugal, and western countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary,Poland and the Russian Federation, as well as many other Asian, Latin Americanand African countries (UN, 2006: 38-41).

The programs are focused on both low and high qualified workers, especiallythose who work in high-tech fields, namely informatics, biotechnology, andcomputing among other. Nonetheless, while facilities are given to those qualified,increasingly greater restrictions are set for those who are not, with suchargumentations as they are not required by the recipient economy, there areenough domestic workers to carry out the national tasks, their presence becomesan obstacle to technologize the economic branches where they are hired, etc. Itis so that before the requirements of this sort of labor force and the refusal of thelocal governments to recognize them, undocumented migration has noticeablyincreased in the aforementioned countries. It is calculated that in the UnitedStates there are circa 11 million unauthorized people among which the lessqualified workers prevail.1

The United States is the recipient country with the most seasonal andpermanent migrants or immigrants, and according to the general trends they haveintensified the mechanisms to import highly-qualified seasonal workers. Besidesconstructing the largest contingent, these highly-qualified workers have a seriesof prerogatives as for the time they stay, facilities to renew it and even to becomedefinitive migrants.

In this research we make an analysis of the visas for workers with lowqualifications in the United States: the H-2A and H-2B visas; their differencesfrom those focused on qualified laborers and the way they have been implementedthrough time, making an evaluation of their benefits and limits, with specialattention to the Mexican workers’ experience. To sum up, this work presents adescription of the programs of seasonal workers in the United States, the mainlaws related to the non-migrant laborers, the application of the H-2 programs andsome conclusions.

1 According to Passel, unauthorized workers are noticeably underrepresented in white-collaredoccupations: in those of administration and professions, as well as in those of administrative supportand sales. Hence, while the percentage of local workers employed in them was 62 percent in March2005; the unauthorized were only 23 percent. Conversely, in activities such as the agricultural, andconstruction and extraction, their weight was three times as much more than the natives’. In the serviceoccupations something similar occurs, the undocumented were 31 percent, which is almost the doubleof the percentage of the natives (16 percent) (Passel; 2005: 11).

106

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

The programs of seasonal workers in the United States2

a) Traditionally, the United States have been seen as a country of permanentmigration. The symbolism of Ellis Island as the beginning of the American dreamwas present in million of Europeans who arrived to this country during the XIXcentury and in the early XX. This has not been the case of Mexican workershowever; whilst the processes of administration of European immigrants tookplace in the northwest part of the United States, an important number of Mexicanpeople crossed the border on the other end of this country, in a seasonal manner,to carry out non-qualified duties, such as the laying of railways, agriculture, thepackaging of fish or in the Californian gold mines. Despite their importance forthe regional development, they were virtually ignored in the changing migratorylegislation. Politicians and entrepreneurs recognized their contributions, yet theynever set any sort of regulation to organize this migratory flow and not to mentionto defend them from the abuses of the employers. They rather let it work in aninformal manner following the requirements of the market.

As a mater of fact, according to Jachimowicz and Meyers, the practice ofseasonal hiring of workers was banned in 1885, when the First Act on laborcontracts was approved (Jachimowicz and Meyers, 2002). In spite of this, the1917 Immigration Act contemplated the presence of guest workers, and paidspecial attention to those from Mexico, who were exempt from the requisite ofbeing literate, imposed to immigrants, since there was a great need from thefarmers to have this sort of labor force (Rural Coalition Policy Center, 2003), butwithout establishing any regulation on their numbers, characteristics, sort ofhiring, et cetera.

b) It was not until 1942 when a program of guest workers was adopted, theEmergency Farm Labor Program, widely know as the Bracero Program, dueto the emergency caused by WWII. For the first time, Mexican laborersaccessed the agriculture of the United States in a legal, supervised and regulatedform (Galarza; 1964: 14), protected, in the paper, from the abuses of entrepreneursand intermediaries. Between 1942 and 1947 said program functioned on the basis

2 Seasonal workers are accounted for in official documentation as non-immigrants. By and large, itis thought that a non-immigrant is “an alien who seeks to temporarily enter the United States witha specific purpose” (DHS, 2002: 82). In the case of seasonal workers or non-immigrant workers thepurpose is in fact to carry out the job they were hired for.

107 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

of a formal agreement with the Mexican government,3 because of this the latterwas able to negotiate several entries in favor of its workers: guarantee of non-discriminatory treatment, deign conditions of labor, wages equitable to those ofthe American laborers (Morales, 1989: 146). Nevertheless, when the war wasover, conditions changed. The American workers returned and, although thefarmers asked to preserve the program, the capacity of negotiation of theMexican Government decreased.

Its importance lies both in the quantity of people in it involved and in thedynamics established between the United States’ capitalist agriculture and theMexican labor force. According to Galarza (1964), its boom occurred in the1950’s, as the Public Law 78 was decreed in 1951, this system bloomed, thusbecoming the main element in the agricultural economy of Texas, California,New Mexico, Arizona and Arkansas, and to a lesser extent in other 20 States.In said decade, more than 3.3 million Mexicans were hired as braceros and 275important agricultural areas of the nation made use of them (Galarza, 1964: 15).According to Holley, between 1951 and 1957, the percentage of braceros inrelation to the total of seasonal agricultural labor force was doubled, and itchanged from 12 to 28 percent. In some regions they were 100 percent (Holley,2001: 583).

The Law established that the employers had to pay the wage prevailing in theagricultural sector in order to prevent an adverse effect on the local workers, thetransportation expenses (arrival and departure) and expenditures on housing andalimentation. Notwithstanding, the considered stipulations were seldom fulfilled,for the contracts were controlled by associations of farmers and were writtenin English, which was added to the fact that the workers were unable to join anyorganization4 (Waller, 2006: 1-2). According to the Rural Coalition Policy Center(2003), the consequence was the depression of salaries of the local workers andthe institutionalization of conditions below the norm for all of the workers linkedto the agricultural industry.

3 It was the commission created by the Immigration and Naturalization System, in April 1942 —integrated by the Commission of Employment in Wartime, the Departments of Agriculture, State andJustice, as well as the Mexican Secretariat of Labor —which suggested that in order to implement anyprogram which wanted to take Mexican workers the participation of the Mexican Federal Governmentwas necessary (Morales, 1989: 145).4 This was contributed by their lack of knowledge of the English language, scarce schooling, unawarenessof the stipulations of the contracts, distancing of the cities and the little interest of the U.S. authoritiesand Mexican consular representatives to assist their demands.

108

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

The pressure of the unions, churches and civil right organizations, amongother groups, led to the cancelation of the program (in 1964) because of theabuses committed, in spite of the advantages that it offered the agriculturalentrepreneurs, and which are still emphasized by those who strive to set a newsimilar system of hiring.

Concluded the Bracero Program and without any other option to organize theMexican flow, the government of the United States gave way to irregularmigration,5 necessary to satisfy a labor demand which only the Mexican laborerswere interested in covering.

c) In addition to the Bracero Program, in the years of WWII the British WestIndies Temporary Alien Labor Program (BWITALP) was created, whichallowed attracting to the East Coast some 66000 workers for the fruit, vegetaland sugar cane sectors, mainly. It had its origin in a Memorandum of Understandingbetween governments such as Bahamas, Barbados, Canada and Jamaica andthat of the United States, a document that the parties progressively signedbetween 1943 and 1947. Finally, it was formalized under the Public Law 45;when the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), also known as the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, the Memorandum was absorbed by the H-2 seasonalworkers program. Since it was an agreement between governments, as theBracero Program, the recruiting was organized between them, later the employerswere allowed to make negotiations on their own in other islands (Waller, 2006:1-3).

The program concluded due to the disagreements between sugar-caneproducers and workers, because of the violations to the labor contracts, at themoment when the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) was beingdiscussed and the inclusion of Mexican and Chinese laborers was discussed6

(Griffith, 2002: 20-26). Notwithstanding, and in spite of the vulnerability theywere exposed to, many a Caribbeans longed for the opportunity to work in theUnited States, so the in new program of H-2 visas, included into IRCA, theirparticipation remained in reduced numbers and mainly in visas for non-agriculturalworkers.5 We have to point out though, that undocumented migration was never suppressed during the timeof the Bracero Program. Nevertheless, its numbers increased when bookings were reduced.6 Griffith (2002: 27) points out the elements that undermined the program: sues pressed by the workersbecause of the continuous violations to their rights from the employers and which cost the latter severalmillions; the changes in the program of H visas in IRCA in 1986; violations to labor and human rightsof the workers, denounced by researchers, journalists, human rights’ defenders and even filmmakers;the disclosure of corruption of the Jamaican functionaries in charge of manage the program and theinvestigations of the Congress.

109 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

The United States’ legislations on non-immigrant laborers

Independently from the agreements of the government of the United States withsome countries to cover the demand of labor force, mainly in agriculture, thecongress of this country has issued several laws tending to regulate migrationboth seasonal and permanent. Below the most important laws for the topic willbe analyzed.

a) McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 considers for the first time the hiring ofseasonal workers in certain occupational categories during scarcity of laborforce. In it qualified workers are distinguished from those unqualified, as itcreates H-1 visas to import specialized labor force and H-2 visas for thatunqualified. In this time, it was not well defined what it was understood by“specialized”, so a wide variety of professionals were considered as such. H-2visas, conversely, were focused on covering the demand of agricultural work inthe west part of the country, since the contracts of the Mexican braceros werenot included in them (Holley, 2001: 581 and 587; Wassem and Collver, 2001: 2and 5). These visas were preserved after the Bracero Program finished, alwaysin reduced numbers, and it was not until the changed implemented into the 1986legislation that Mexicans were able to partake of them.

b) Besides cancelling the Bracero Program, and in view of stopping Mexicanimmigration, the government of the United States issued the Immigration andNationality Act Amendments in 1965, for the first time it was intended to limitthe number of admissions of Mexican immigrants to 66000 a year.7 However,the demand for inexpensive labor force made the law inoperative, for inaccordance with Vernez and Ronfeldt (1991: 1190) the Mexican immigrantsgrew five times within the 1970-1988 period, being two thirds of themundocumented.

Complaints among the sectors traditionally concerned by immigration beganafresh, mainly during the crises of the American economy in 1974 and 1980-1981, the same as for the attacks on the Mexican laborers whom were blamedon all the evils, especially unemployment. It is so that a large part of the periodfrom 1975 to 1986 a new legislation to solve the problem was discussed in thegovernmental media.

7 Contemplated successive reductions until reaching 20000 in 1976.

110

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

c) These processes culminated in 1986 with the implementation of the Publiclaw 99-603, Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). Altogether with themeasures of entrepreneurial and border control considered, this law enabled thelegalization of an important number of undocumented workers who resided in theUnited States even before 1982, and of those who had worked on the agricultureat least for 90 days the previous year. What is more, for fears of theentrepreneurs of scarcity in labor force because of the border reinforcement, thislaw reformed the H-2 visas program to include Mexican laborers, both agriculturaland non-agricultural, whose work had an evident seasonal character; with thissort of visas it was sought to prevent the new workers from remainingindefinitely, thus avoiding the expenses of supporting their families and themselveswhen they were no longer useful for the economy of the United States.

d) Another important change in the migratory legislation was the issuing ofthe Immigration Act of 1990 (IMMACT90); unlike 1986 IRCA, which sought tosolve the problem of the undocumented laborers, most of which had lowqualifications, the new law was focused on the attention to the employers’demands for highly qualified workers. Global competence, computing revolutionand the transformations in the productive processes posed, for both leadingenterprises and research centers, the disjunctive of attracting workers with greatabilities and remain in worldwide competence or losing terrain in this field. Thetwist was deep as the traditional schema of migratory policy was modified,prioritizing the admissions by occupational qualification over those focused onfamilial reunification that had prevailed ever since this scheme was establishedin the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952. The proportion of immigrants who wereable to enter this country in a year on the basis of their abilities changed from 10to circa 21 percent, which means an increment from 54000 to 140000 (Alarcón,2000: 2). A system of preferences which defined how these 140 thousand visaswere to be assigned was established, naturally, those people with extraordinaryabilities had a predominant place, whereas only 10000 visas were destined forunqualified laborers (Alarcón, 2000: 4; Mehta, 2004).

It is noteworthy that the number of admissions of immigrants turned out to beinsufficient to assist the market requirements, so there was also a modificationin regards to the policy of seasonal workers’ admission, where special attentionwas paid to qualified workers. Out of 17 categories of different sorts of non-immigrant workers, only two were assigned to workers with low qualifications,despite the traditional claims from the enterprises which make use of this typeof labor force. The more emphasized visas were the H-1, which were split into

111 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

H-1A and H-1B and their requirements were better defined so as to really attracthighly qualified laborers. H-1B visas, in particular, were created for the workerswho perform the ‘special occupations’, based on educational level, abilities,expertise, among which distinguishable are those of analysts and computingprogrammers, followed by medics, scientists, engineers and university professors,to name a few (DHS, 2003: 94).

Moreover, new categories were created to attract workers who, withoutfulfilling the requirements for H-1B visas, were considered “workers withextraordinary abilities and important achievements”,8 and some visas previouslycreated were updated, which authorize their bearers to work seasonally in theUnited States.9

Waller (2006: 3) stresses the sheer contrast between the reduced number ofdefinitive admissions and (155 330 in the year 2004) and that of admissions ofnon-immigrant workers and trainees with their relatives (1.48 million), which isan instance of the turn the United States gave their traditional role as a countryof immigrants. It bears mentioning, however, that in reality what was beingcaused with this policy, and mainly with the imposition of restrictive measures toentrance, was the increment of undocumented immigration which was socontrolled and the extension of the stay in the country.

H-2 visas for non-qualified workers

With these visas which respond to the requirements of some powerful economicsectors such as that of farmers, it is intended that the less qualified workers enterthe United States and carry out the task they were hired for, with the petitioneremployer and return their country thereafter.

8 Among the new visas outstanding are the ‘O’, destined for people distinguished in sciences, arts,education, business, sports and film or television production; the ‘P’ for athletes, trainers andinternationally recognized artists, or within an interchange program or “culturally unique”; ‘Q’ visasfor participants of international cultural interchange programs and ‘R’, for those who perform workof religious nature (DHS, 2002: 120). Later the ‘TC’ visas were first created, then the ‘TN’ —whichsubstituted the ‘TC’— as a result of NAFTA, between Canada, United States and Mexico, where Mexicoaccepted that these visas were only destined for people who travelled to take part in professionalbusiness activities, leaving aside the Mexican workers who traditionally work in U.S. economy(Cornelius, 2000: 4; DHS, 2003: 94).9 Among them, ‘F’ and ‘M’ visas which are assigned to students; ‘J-1’ visas to interchange visitors and‘L-1’ for intra-company-transferred personnel to perform managerial duties or executives ininternational enterprises and corporations.

112

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

H-2A visas have as an end the admission of agricultural workers to carry outa determinate activity, seasonal by nature. Several governmental organizationstake part into its implementation: the Department of Labor (DOL), whichcertifies; Immigration and Naturalization Service (currently U.S. Citizenship andImmigration Services),10 which administrates it and allows the permission forvisas, and the Department of State which grants the visas through someconsulate (Wassem and Collver, 2001: 2).

The function of DoL is to issue a labor certification, after carrying out aninvestigation to prove there are not workers residing in the United States who areinterested, qualified and available at the moment and place to carry out the jobor service involved in the petition; as well as the fact that the work of the foreignerin said service or job does not adversely affects the wages and conditions of theworkers in the United States employed under the same conditions. It also has tosupervise the functioning of the program and, in the case of violations, sanctionfor up to 1000 USD for each one of them (Wassem and Collver, 2001: 2-4).

Among the obligations imposed to employers are: 1) pay the same salary theUnited States’ residents perceive11; 2) provide a document where the worker’sthe total income is detailed , labor conditions and working hours; 3) transport fromthe home of the worker to the place of work and then to the following place ofemployment when the contract concludes; 4) housing with the least conditionsat federal level; 5) agricultural tools and implements; 6) food or facilities for theworkers to cook; 7) compensation insurance; and 8) guarantee at least threequarters of the total workload offered (Wassem and Collver, 2001: 3).

With these requisites the hiring of foreigners is intended to be more onerousthan that of local workers. Nevertheless, this is hardly ever fulfilled since theywork in places far away from the city and the law does not provide adequateforms for the worker to call on authorities (Holley, 2001: 574).

Visas might be valid for a year, but renewable for three consecutive years(Wassem and Collver, 2001: 4).

10 As from March 11th 2003, the U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) come one of thethree components inherited from INS to integrate the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS).USCIS is fundamentally in charge of transforming and improving the immigration and citizenshipservices, at the time it reinforces national security (http://www.uscis.gov/graphics/aboutus/index.htm).11 Wage must be the highest among the Adverse Effect Wage Rate, the prevailing minimum wage, federalor State, of the region where the job is performed. AEWR is annually determined by DoL in each regionof the country, in order to avoid the salary paid to this sort of laborers adversely affects the wages ofAmericans in similar positions.

113 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

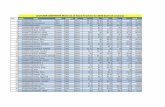

Form their inception, the number of people hired with H-2A visas has beendrastically reduced, mainly if we compare it with the 1.2 million people hiredannually in the agricultural fields in the United States for a wage.12 Unfortunately,the number of people who enter each year with said visas is not certainly known,since data published by the involved instances make reference to differentaspects.13 In graph 1, one sees some of these discrepancies, although data fromthe Department of State and DHS (formerly from INS) coincide on theincrement the visas had in the 1990’s decade, changing from 7243 in 1993 to30200 in 2000, in the information of DoS and from 14 628 to 32 372, in those ofINS, quantities are utterly different. The contrast is stressed as from then, as thetrends change. In the information from DoS the people who received these visasthe following years are still on the rise, with the exception of the year 2003; while,in that from DHS they are reduced, save in 2004, until they reach 7011 in the year2005.14

Separately, citizens from 33 countries received H-2A visas in the 2005 fiscalyear. Workers from Mexico concentrated the most shares (89.6 percent),followed from afar by South-Africans, with 3.9 percent; Peruvians, with 2.2percent and Thais, with 1.2 percent (see graph 2). This is also the case of theregistrations of DHS are different indeed, and although in them Mexican also aredistinguishable, their weight has been notably reduced. Whereas in 1996 theywere 91.7 percent of the workers who entered with these visas, for 2004 theyonly were 77.8 percent.15 Jamaica, which after labor problems and changes invisas reduced its presence, in recent years it has incremented its presence in suchmanner that, while in 1996 Jamaicans were only 1.3 percent of total, in 2003 theyreached 17.6 percent, decreasing a little in 2004 (11.9 percent).16 However, in

12 Out of which half of them, at least, are undocumented (Martin, 2001).13 Thus, for example, DOS in charge of issuing visas does not include the countries whose citizens donot need to apply for a visa in any consulate, such as it is the case of Canada and Jamaica; conversely,DHS records the entrances with each visa, so the same person might be recorded several times. DOL,on its own, indicates the number of occupations it certifies, and the same worker might perform severalof these occupations as they might last a few days and varied periods (Wassem and Collver, 2001: 4-5).14 Even though it is very likely that the exaggeratedly reduced of this last figure might be due toregistration errors, as it is not believable that after the difficulties to acquire and pay for the visas theydecide not to enter; this is verified when one sees the reduced number of workers who headed for NorthCarolina, and which was only 162.15 the figures of the year 2005 are not very believable for they show a petty amount of Mexicans withH-2A: 1282, which make up 18.3 percent of the total, below Jamaica, which concentrates 40.2 percent(2816 entrances).16 Despite we know the relative importance of the bearers of these visas, Jamaicans and Canadians arenot included as, previously declared, they were not recorded by DoS, since they do not apply for visasin their countries.

114

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

Sour

ce: f

or ad

mis

sion

s IN

S an

d D

HS

year

book

s of d

iffer

ent y

ears

. For

issu

ed v

isas

from

199

3 to

200

3: A

nder

son,

28-

1-04

. For

200

4-05

, D

epar

tmen

t of

Sta

te,

http

://tra

vel.s

tate

.gov

/vis

a/ab

out/r

epor

t/rep

ort_

2786

.htm

l#.

7,24

3

16,0

11

31,5

38

29,8

82

31,8

92

14,6

28

9,63

5

33,2

92

14,0

94

22,1

41

7,01

1

0

5,00

0

10,0

00

15,0

00

20,0

00

25,0

00

30,0

00

35,0

00

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

Vis

as e

miti

das

Ent

rada

sIs

sued

vis

asEn

tranc

es

GRA

PH 1

NU

MBE

R O

F AD

MIS

SIO

NS A

ND

EN

TRA

NCE

S ‘H

-2A

’ VIS

AS F

ROM

1993

TO

2005

115 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

Sour

ce:

Dep

artm

ent

of S

tate

, 20

05 (

prel

imin

ary

data

), ht

tp://

trave

l.sta

te.g

ov/v

isa/

abou

t/rep

ort/r

epor

t_27

86.h

tml#

.

89.6

3.9

2.2

1.2

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.

0

Méx

ico

Sud

áfric

a

Per

ú

Taila

ndia

Nue

va …

Rum

ania

Nic

arag

ua

Aus

tral

ia

Gua

tem

ala

Chi

le

H-2

A

GRA

PH 2

MA

IN R

ECEI

VIN

G O

F H-2

A V

ISA

S ISS

UED

BY

TH

E D

EPA

RTM

ENT

OF S

TATE

IN 20

05 (P

ERCE

NTA

GES

)

New

..

Mex

ico

Th

aila

nd

Sou

th

Afr

ica

Ro

man

ia

Per

u

116

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

Sour

ce, f

or 1

999,

Was

sem

and

Col

lver

: 200

1, a

nd fo

r 200

3, U

.S. D

epar

tmen

t of L

abor

, Em

ploy

men

t & T

rain

ing

Adm

inis

tratio

n.

24.5

13.9

9.27.2

1.9

5.5

4.53.1

2.53.6

1.90.6

1.2

21.6

8.2

7.2

5.8

4.7

4.64.

13.1

3.1

2.92.

82.

52.2

0.0

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

25.0

30.0

Nor

th

Caro

lina

Geo

rgia

Virg

inia

Ken

tuck

yLo

uisia

naN

ew Y

ork

Tenn

esse

eA

rkan

sas

Sout

h C

arol

ina

Texa

sId

aho

Flor

ida

Cali

forn

ia

1999

2003

GRA

PH 3

PERC

ENTA

GE

IN C

ERTI

FICA

TIO

NS F

OR

WO

RKER

S WIT

H H

-2A

VIS

AS O

F TH

E M

AIN

STA

TES

BY FI

SCA

L Y

EAR

(199

9 Y 20

03)

117 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

absolute terms, it number has been reduced. For by the end of the 1990’s decadesomewhat more than four thousand entered the United States, which in the year2000 and subsequent years were reducing until reaching 1577 in 2002. Eventhough as from then they began to increase, their number was always below3000; followed in importance by: South-Africa, Canada, Peru and Thailand,although their numbers are much lower (below 1000 annually).

H-2A workers are required to very diverse activities; almost a third part ofthe visas certified by DoL are for tobacco cultivations; 16 percent for fruits (athird for apples), and 12 percent for vegetables. Yet they are also needed for thecare of sheep, livestock, fowl, bees; to work with Christmas trees, sugarcane andgreenhouses and irrigation, machinery operation, etc. it is not surprising that theStates with the most of certifications are tobacco producers: North Carolina,Georgia, Virginia and Kentucky, among which the first is notable with more thana fifth part (graph 3). Conversely, the main recipients of migrants: Texas andCalifornia, only receive 2.9 and 2.2 percent of the visas, so that are ranked 10th

and 13th respectively.b) H-2B visas are oriented to non-agricultural seasonal workers and impose

two conditions: no availability of workers in the United States and prove it is aseasonal activity. DoL recognizes four situations where there is a seasonal needfor workers: for recurring seasonal activities, for intermittent activities, harvesting-loading and activities that only occur once17 (Wassem and Collver, 2001: 2;Siskind, 2004).

Similarly to H-A2 visas, the longest period is a year and it might be extendedfor up to three; but in this case there is a limit of 66000 annual workers,18 whichwas reached for the first time in 2004.

Eligible are both qualified and non-qualified workers, with the exception ofmedics and agricultural workers. The typical branches they are hired in are:gardening, forest conservation/ logging, tourism both in hotels and leisure centers,mainly where workloads are concentrated on certain seasons; education,construction, health and food processing, among others.

The work in the forest of the people called ‘piners’ is the second in the numberof these visas,19 after that of gardener. It is of the utmost importance for the17 There is not a rule on how long a season may be, yet most of the offices of DoL reckon that seasonsof more than nine or ten months in a year are a continuous and not temporary job (Siskind, 2004).18 Not included in this limit the applications to extend the period for a worker H-2B already in theUnited States, and those which ask to change the terms of the employment for H-2B workers alreadyin the United States, and those in which the H-2B workers, in the United States, ask to change or addemployers (Siskind, 2004).19 Knudson and Amezcua (2005) calculate the number of piners between 15000 and 20000, and eventhough they live with some undocumented people most of them are H-2B workers.

118

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

conservation of forests in the United States and, for decades, only workers fromLatin America are interested in taking it, for it is one of the most dangerousactivities and with worst life conditions, since it is developed in the mostinaccessible places where some sort of vigilance is seldom carried out (Knudsonand Amezcua: 2005).

In touristic services, the workers are required in a wide variety of activities:managers, trainers and athletes, who do not satisfy the requirements for othervisas for sportspeople (O and P), gardeners, bellboys, croupiers, porters,dishwashers, kitchen helpers, housemaids, waiters, employees for the maintenanceof golf courses and for the fixing and installation of central heating and airconditioning systems.

They are also highly appreciated in the processing of sea products. In Alaska,for instance, Japanese workers are hired to adequately classify and pack salmonand its roe, as the local workers do not have the expertise to prepare the productaccording to the requirements of the Japanese market. In Louisiana they arehired to fish sheatfish; in North Carolina, Virginia and Maryland, in the processingplants of blue crab, and in the South West, in seafood industry (Porter, 2004;Flanagan, 2005; Gentes, 2004). In many of these companies Mexican womenhave replaced previous female workers, most of them Afro-American of lowincomes, since the latter have found other more attractive opportunities in thetouristic industry, leisure activities and nursery20 (Griffith, 2002: 33). Mexicanfemale workers started to arrive in 1988, the program grew and now they arebetween 1200 and 1600 women hired in 28 to 30 factories. Nonetheless, this hascaused the reduction of workloads, thereby, wages (Griffith, 2002: 33).

The application process for H-2B visas is similar to that for H-2A visas; theemployer must obtain the certification from DoL and, to achieve it, lead arecruiting campaign, taking into account the directions from the Agency of StateEmployment on the sort of recruiting efforts required in the area (Siskind, 2004,and Flanagan, 2005). Then the employer must fill up an form of USCIS and paythe fees to obtain it and, finally, obtain the approval of visas from the Departmentof State (Flanagan et al., 2005).

The applications have to be done up to 120 days before the workers areneeded, which makes it difficult for summer employers, as in the moment theyhave possibilities to apply, the visas have been given to ski instructors, jockey

20 Griffith (2002:31) points out that the work in crab fisheries is of very little attractiveness for womenwho reside in the U.S. because it is tedious, repetitive, dangerous and unpredictable; the payment is widelyvariable and the places of work are uncomfortable and smell badly.

119 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

Ent

ries

H

-2A

H-2

B

Gen

eral

A

dmis

sion

of

agri

cultu

ral l

abo

rers

. A

dete

rmin

ate

acti

vity

. N

on-

agri

cult

ural

wo

rker

s w

ith

or w

ith

out

qual

ific

atio

n, y

et s

easo

nal

L

engt

h A

yea

r th

at m

ight

be

pro

long

edfo

r tw

o o

r m

ore

Dem

and

to t

he

emp

loye

rs

Pay

the

sam

e w

age

as t

he U

.S. r

esid

ents

Hou

sing

, fo

od,

tra

nspo

rt, t

ools

, co

mpe

nsat

ion

insu

ran

ce

Th

e sa

me

dem

ands

are

no

t im

pose

d in

the

ca

ses

of H

-2A

D

ocu

men

t tha

t sp

ecif

ies

lab

or

cond

itio

ns

Gua

rant

ee a

t lea

st 3

/4 o

f w

ork

Gov

ern

men

tal

inst

ance

s th

at

par

tici

pate

D

epar

tmen

t of

Lab

or

(cer

tific

atio

n);

Cit

izen

ship

an

d Im

mig

rati

on S

ervi

ces

Off

ice

(aut

hor

izes

the

ass

igna

tio

n o

f vi

sas)

; D

epar

tmen

t of

Sta

te (

gra

nts

the

visa

s)

Act

ivit

ies

that

inc

lude

Tho

se r

elat

ed t

o a

gric

ult

ure

(tob

acco

, fru

its

and

veg

etab

les)

, w

ater

ing,

live

stoc

k, b

ovi

ne a

nd

ovi

ne, p

oult

ry, h

orse

s, e

tc.

A b

road

var

iety

, no

tabl

e ar

e: g

arde

ners

, fo

rest

al w

ork

ers,

lod

ging

act

ivit

ies,

co

nst

ruct

ion

, sta

bles

, sp

ort

ins

truc

tors

se

afo

od p

roce

sso

rs.

Lim

its

N

o

66 0

00 a

nnu

al v

isas

So

urce

: U.S

. Dep

artm

ent o

f Hom

elan

d Se

curit

y.

TABL

E 1

CHA

RACT

ERIS

TICS

AN

D R

EQU

IREM

ENTS

FOR

H-2

VIS

AS

120

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

players and others winter workers. Among the most affected entrepreneurs wefind the crab processers in North Carolina, hotels in the places of summerholidays, and the operators of helicopters for the fire departments along the west(Porter, 2004).

Even if the congressmen of the States with the greatest problems to hireseasonal workers have asked to increased their numbers, it has not beensuccessful since it is pointed out that it is part of the reform to migration as awhole. The only response to their petition was Save Our Small and SeasonalBusiness Act on May 23rd 2005, where it was established that for the fiscal year2005 approximately another 35 thousand workers will be able to enter (DHS,2005).

In the beginning, H-2B visas were sparsely asked, however, the applicationfor them was notably increased as from the turn of the century. Whereas in 1996,12200 visas were issued, in 2000 their number had grown four times (45037),reaching 87490 in 200521 (graph 4). Even though H-2B workers are distributedacross the United States, data from DHS22 show Texas takes the largest number(12.2 percent), followed by North Carolina (7.2 percent), Florida (5.9 percent),and Colorado (5.3 percent).

All in all, forty-seven countries send people with H-2B visas, among whichMexico is distinguishable with 89184 people, followed by Jamaica with 9123,Guatemala (3725), Canada (2641), South Africa (1714) and England (1517).Unlike H-2A visas, in these others the weight of Mexico was on the rise, for whilein 1996 the entrances of Mexican people only were 38.6 percent, they reached72.6 percent23 in 2005. It is notable the participation of European and Canadianworkers, which perhaps is due to the participation of specialized workers in thisprogram, such as it is the case of sportspeople. Nevertheless, the availableinformation does not allow us to know the details on them. Even though we haveto mention that differently from H-1B visas which are granted to highly qualifiedpersonnel and where two-thirds are for Asians and a fifth for Europeans, H-2Bvisas are only assigned to 5.6 percent of Europeans and 1.7 to Asians.

21 Even if in recent years their number surpasses the limit of 66000, this is due the exceptions statedin the note 18 and in the year 2005, and also to the aforementioned Save Our Small and SeasonalBusinesses Act.22 The Department of State dos not publish information in the destination States, so perhapsinformation from DHS is used.23 It is not surprising that in the case of entrances the percentage is higher (72.6 percent) than in theissued visas (68.9 percent), because of adjacency.

121 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

c) To locate and contact workers, the employers use different methodsamong which the media, familial and paisano networks are outstanding as wellas the sending of envoys. This depends, to a large extent, on the number ofworkers needed, on the ties with previous laborers (who on occasions may havebeen hired as undocumented) and the number of people required.

In different researches and journalistic reports there are examples of thesesorts of hiring; remarkable, among them, is the method used by the NorthCarolina Growers Association (NCGA), and that is the one which hires the mostH-2A workers hire, especially for tasks in tobacco.24 Its network reachesMexican towns through subcontractors coordinated by its local branch, Manpowerof America (MOA), company established in Monterrey, five blocks away fromthe U.S. consulate. According to an article by Cano and Nájar, the managercharges 500 USD to each applicant and another 500 USD to each grower perworker (Cano and Nájar, 2004).

The network of MOA extends throughout Durango, Zacatecas, San LuisPotosi, Hidalgo, Guanajuato, Nayarit, Oaxaca, Puebla, Jalisco, Veracruz andsome other States, and handles 13500 visas a year; although its main clients areranchers from North Carolina, it also has some in Georgia, Indiana, Mississippi,Texas and Ohio (Cano and Nájar, 2004).

In the case of H-2B visas there are also similar instances; in the reportagesby Chris Guy (2005) of the Baltimore Sun, on the crab industry on the UnitedStates, the enterprise called Del Al Associates from Virginia is mentioned, whichhas an office in Monterrey, with subcontractors in other localities. The one inCuidad del Maíz, San Luis Potosi, where the women in charge states she hires800 women to work in Alabama, Virginia, North Carolina and Maryland.

The role of these enterprises is not over with hiring: MOA also has otherbusinesses such as: transport to move the workers and an office to send money.25

Del Al Associated earns, besides the fees from the female workers, fromtransport and services of ATM and exchange rates. In total, according to theinterviewed women, the transport to the United States costs circa 650 USD.

In some cases, local governments become the intermediaries betweenentrepreneurs and future hired. In Zacatecas, for instance, the State Institute of

24 According to the information from DoL (2005) in 2003, 9516 workers from North Carolina werecertified, who constitute 21.6 percent of the total certifications, which is 25 percent of the total ofcertified enterprises (http://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/foreign/h-2a_atlanta.asp).25 We have to point out, in this respect, that these contractors charge the workers the tools and thetransport they use, which should be paid by the employer (Cano and Nájar, 2004).

122

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

58,3

27

91,3

60

161,

643

107,

19613

8,95

8

124,

096

11,0

04

31,5

3831

,892

12,2

00

58,2

1578

,955

87,4

92

0

20,0

00

40,0

00

60,0

00

80,0

00

100,

000

120,

000

140,

000

160,

000

180,

000

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

H-1

BH

-2A

H-2

B

Sour

ce:

Dep

artm

ent

of S

tate

, 20

05 (

prel

imin

ary

data

), ht

tp://

trave

l.sta

te.g

ov/v

isa/

abou

t/rep

ort/r

epor

t_27

86.h

tml#

GRA

PH 4

NU

MBE

R O

F H-1

B; H

-2A

AN

D H

-2B

VIS

AS I

SSU

ED B

Y T

HE

DEP

ART

MEN

T O

F STA

TE FR

OM

1996

TO

2005

123 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

68.

9

9.7

4.2

2.3

2.1

1.8

1.7

1.7

1.5

1.3

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

Mex

ico

Jam

aica

Gua

tem

ala

Bra

zil

Col

ombi

a

Ven

ezue

la

Sou

th …

Arg

entin

a

Gre

at …

Aus

tral

ia

H-2

B

Sour

ce:

Dep

artm

ent

of S

tate

, 20

05 (

prel

imin

ary

data

), ht

tp://

trave

l.sta

te.g

ov/v

isa/

abou

t/rep

ort/r

epor

t_27

86.h

tml#

GRA

PH 5

MA

IN C

OU

NTR

IES W

HIC

H R

ECEI

VE

H-2

B V

ISA

S ISS

UED

BY

TH

E D

EPA

RTM

ENT

OF S

TATE

IN 20

05

124

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

Migration (Instituto Estatal de Migración) promotes the hiring of theseseasonal laborers through the Program of Temporary Employment (Programade Empleo Temporal), so as to reduce frauds and undocumented migration(Wassem and Collver, 2001: 2). Annually agents from different enterprisesarrive, among them the representatives from the City of Thornton, to hireworkers for gardening, however, women are also hired to work in Mississippi(Hernández, 2004).

Nonetheless, altogether with these big businesses, contractors and localgovernments, there are many workers who simply have verbal arrangementswith their future employers when they are working there or through somerelative. There is not information on the way they, the workers, perform theformalities in the U.S. consulate and whether they manage to avoid the use ofintermediaries or coyotes.

d) The conditions of work depend heavily on the employer, on the sort of workand how far from the cities the place of work is; nonetheless, most of theMexicans and Central-Americans contracted under these programs carry outworks classified as 3D: dirty, dangerous and demanding (Waller, 2006: 3). Thetreatment of the employers, housing, food and, mainly, respect for the agreedconditions, widely vary. It is so that while some hired workers seek to returnevery year with the same patron, others prefer to return earlier, quit their job andlook for an activity as undocumented, or simply not going back. We have to pointout, however, that many return in spite of everything because the situation in theircountry is much worse.

Whilst approval comments are uttered in cases of the authorities of the Cityof Thornton, Colorado, and the employers of Indiana (Hernández, 2004), in thecase of the ‘piners’ there are numberless complaints that are described in detailin different media, as the narrations made by Hudson and Amezcua, ofSacrament Bee (2005), and Greenhouse, of the New York Times (2001). In bothcases there are references to the very inferior salaries to those in the zoneswhere they work very long hours (which reach 70 hours a week), the badconditions of the housing (if they are offered any), deficient food and the hygienicconditions. What is more, unlike that which occurs with H-2A workers, there isnot an obligation to offer them these services so these are paid at higher pricesthan their real value. No one is responsible for these abuses, for the owners ofthe forests, which frequently are national forests, state that the contractors are,the contractors argue they only take the workers but they are not responsible.

125 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

A list of abuses has also been written down in the case of the tobaccogrowers, who, supported by the contractors from MOA, exercise an almostmilitary discipline on the laborers, where mistreatment and insults are part of thelabor organization, and the black role becomes an almost constant threat in theface of any indiscipline display.

By and large, the working days are exhausting and, in many a cases the workis paid as tender, the working pace is accelerated, which for instance the growersneed as the products are perishable, whose value is dictated by a very volatilemarket (Holley, 2001: 576-577). The fatigue accumulated is stressed when theplaces where the workers live are in bad conditions; stacking, lack of beds, andutensils to cook food, as well as lack of potable water.

Because of the type of work they perform, accidents and diseases resultingfrom the labor and environmental conditions are very frequent. The mostdramatic case is that of ‘piners’, whose activity is considered as one of the mostdangerous in the United States. Knudson and Amezcua (2005) point out: they areslashed by chainsaws, concussed by the trees and rocks that fall, verbally abusedand forced to live in miserable conditions. The storms hit them, freezing windsblow upon them, hunger hunts them, and death grasps them. Fourteen Central-American guest workers died victims of the worst accidents in the place of work(not related to fire) in the history of the United States.

Also the agricultural activities are considered very hazardous for health, andin most of the cases, the accidents and diseases are not properly assisted (Holley,2001: 575). For the employers they are purchased merchandise, they use it forsome time and send it back when the work is done; they disavow anything thatmeans wasted time, extra expenditure, a loss of investment. Under theseconditions, workers prefer not to complain and thus avoid to be sent back to theirhomelands without earnings; besides they know that if they did it they would beblack-listed, which would leave them aside from the program for ever.

As it was previously mentioned, one of the functions of DoL is to supervisethe fulfillment of the stipulated conditions and in the case of violations sanctionfor up to 1000 USD. Nevertheless, this supervision is lax, both because of thereduced personnel and the scarce interest, mainly when it is related to works infar-off places.

The difficulties faced by the workers to press charges on abusive employersis due to both the control exercised by the foremen and supervisors and that manywork places are isolated, as well as the racist attitudes of the judges and, ingenera, of the local population who are more interested in protecting theemployers.

126

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

H-2 seasonal workers are not protected by laws as the “Act of protection formigrant agricultural seasonal workers” (AWPA), which rules standards of laborand benefit of unemployment; they do not have social security and do not haveprotection from National Relation Labor Act (NRLA), which establishes theright to collective negotiation. Federal statutes, regulations and laws that rule thissort of workers, rather than compensate vulnerability they are subject to, makeit graver as they are excluded by different juridical means (Holley, 2001: 591-611).

Despite this, the H workers’ programs have also been severely criticized bythe employers because of the governmental instances that take part into theimplementation of the programs, the amount of the necessary steps (which makethe employers hire a lawyer), and because of the slowness of the certification(Wassem and Collver, 2001: 5). This situation is especially grave in the case ofagricultural activities as, according to the employers, the delays affect an activitywhich because of its nature does not admit lateness and too often the period theworkers are required for passes, so they opt for the hiring of undocumentedlaborers who, in spite of difficulties, are easier, faster and more economic to hire.

Conclusions

Along history, Mexicans, who recently have been joined by other Latin-American workers, documented or undocumented, have carried out a series ofjobs, which require scarce qualification, nonetheless necessary for the economicdevelopment of the United States in its different stages.

Notwithstanding, when the different migratory laws are analyzed oneobserves that Mexican people have only been seen as a labor force that is usedand then discarded when it is no longer needed. Thus occurred when the hugemigratory flows prior to the crisis of 1929 appeared; while million of Europeanswere seen as immigrants and many of them as citizens, Mexican migrants wereignored. Their condition of laborers was never verified, neither were theydefended from the employers’ abuses.

The emergence of WWII and the alarm motivated in the American farmerswere the instances, which after half a century being ignored make them be“invited” to participate in the agricultural work of the country. It was then, forthe first and only time that an agreement with the Mexican government wassought, which allowed fixing salaries and deign conditions, even if these only

127 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

lasted as long as the war was on. Although the program was extended until 1964,the labor conditions of the workers progressively deteriorated and the violationsto the contracts from the employers increased.

Finally, this cumbersome system was not required when there was availablework force that entered the country undocumented, which the employers wereable to use and discard according to their needs; since it was intended to preventthe Mexican workers from remaining in this country, the Immigration andNationality Act of 1965 limited, for the first time the number admissions ofMexican immigrants.

The strategy was not successful, before the failure of other optionsundocumented migration increased and once again a strategy had to be schemedto stop the flow. The law with which it was attempted to solve the problem wasIRCA of 1986. It was thought that with the legislation of the undocumented andsome agricultural workers who already lived in the country so that the farmershired the labor force they needed the problem of the Mexican presence in thecountry would be solved once and for all. Ever since, the migrants were givena minute number of seasonal visas, hard to obtain, and very few options to residepermanently.

Nevertheless, the calculations failed once again, business were still in theneed for this sort of work force in ever growing numbers and now, moreover, notonly were workers with low qualification required, but also those with prominentacademic degrees and labor trajectories. A new legislation focused the problemeven if it prioritized the attraction of qualified laborers. With IMMACT of 1990as in most countries, it was distinguished the necessity to attract brains tomaintain the productivity of the enterprises and be able to compete into a globaleconomy where the great world powers were with state-of-the-art technologies.In order to attract the best, they are offered great stimuli, as well as the possibilityto obtain definitive residence taking care, naturally, that the incentives are onlyfor them; whereas, the workers with low qualifications were condemned toseasonal migration or, as in reality has occurred, undocumented migration.

For the highly-qualified laborers from any part of the world a set of optionsis opened, these options which include that of remaining permanently in thecountry where they work currently or want to work in, most of the Mexicanlaborers, and now also from other Countries for the American continent arecondemned to a reduced number of seasonal visas. Their situation of exclusiondoes not end there, for unlike the qualified foreigners, unqualified workers aresubject to, on many occasions, an almost military control from the employers, and

128

CIEAP/UAEMPapeles de POBLACIÓN No. 55

ALARCÓN, Rafael, 2000, “Migrants of the information age: Indian and Mexican engineersand regional development in Silicon Valley”, in Working Paper, num. 16, Center forComparative Immigration Studies University of California, San Diego.CANO, Arturo and Alberto Nájar, 2004, “De braceros a “trabajadores huéspedes”.Mexicanos en la lista negra”, in Masiosare, num. 355, October 10th, 2004.CORNELIUS, Wayne A., 2000, The international migration of the highly skilled: “high-tech braceros” in the United States and Europe, en Ponencia presentada en la AnnualMeeting of the American Society for Legal History, Princeton, October 19th to 21st , 2000,N.J.FLANAGAN, Brendan et al., 2005, H-2B short-term workers: essential for U.S. employers’survival, in immigration daily from ilw.com, February 28th, 2005, http://www.ilw.com/lawyers/articles/2005,0228-flanagan.shtm.FRENCH, Al, 1999, “Guestworkers in agriculture: the H-2A Temporary AgriculturalWorker Program”, publisehd in Labor Management Decisions, vol. 8, num. 1, Winter-spring, taken from: http://are.berkeley.edu/APMP/pubs/lmd/html/wintspring_99 /LMD.8.1.guestwork.html #Guestworkers#Guestworkers.GALARZA, Ernesto, 1964, Merchants of labor: the Mexican Bracero story. An accountof the managed migration of Mexican farm workers in California. 1942-1960, Mc.Nally and Loftin, Publishers, Santa Barbara.GENTES, Lisa, 2004, Northeast tourism to suffer as seasonal visas drying up, TheAssociated Press, April 14, 2004, http://www.chron.com/cs/CDA/ssistory.mpl/business/2504308.GREENHOUSE, Steven, 2001, Migrants plant pine trees but often pocket peanuts,New York Times, February 14th, 2001.

return to their country when they have wasted their health and spent their mostproductive years. Deprived, in most of the cases, of social security, and first aid,as well of accessible legal instances to be defended, they are forced to acquirevisas by means of diverse bribes, labor exploitation backed by a military control,black lists, accidents at work and abuses from the employers.

We have to mention, however, that this occurs because many of the taskscarried out by seasonal workers are year-round activities and they are notrecognized. It is because of this that, as Cornelius states: “in the absence of aneffective bureaucratic and political national apparatus which the politicians insiston imposing to reinforce the closure of “seasonal” workers’ programs, systematicviolations and “seasonal” workers, eventually made de facto permanent additionsto manpower can be anticipated” (Cornelius, 2000: 13).

Bibliography

129 January / March 2008

Guest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United StatesGuest workers’ programs: H-2 visas in the United States /P. Trigueros

GRIFFITH, David, 2002, “El avance del capital y los procesos laborales que no dependendel mercado”, in Relaciones, 90.GUY, Chris, 2005, “The pilgrims of palomas”, BaltimoreSun.com. Series of articlespresented between February and June 2005.HERNÁNDEZ, María del Refugio, 2004, Irán más zacatecanos a trabajar en EU, Imagende Zacatecas, February 13th, 2004.HOLLEY, Michael, 2001, “Disadvantaged by design: how the law inhibits agriculturalguest workers from enforcing their rights”, in Hofstra Labor & Employment Law Journal,July 3rd, 2001.JACHIMOWICZ, Maia and Deborah W Meyers, 2002, Spotlight on temporary high-skilled migration, Migration Policy Institute, http://www.migrationinformation.org/USfocus/display. cfm?id=69#1.KNUDSON, Tom and Amezcua, Hector, 2005, The pineros forest workers caught in webof exploitation, The Sacramento Bee, November 13th-15th 2005.MEHTA, Cyrus D., 2004, US immigration laws: emerging trends in policies andprocedures, American Immigration LLC, ILW.COM.MORALES, Patricia, 1989, Indocumentados mexicanos. Causas y razones de lamigración laboral, Editorial Grijalbo, Mexico.OCDE/SOPEMI, 2005, Trends in international migration 2004.ORGANIZACIÓN DE NACIONES UNIDAS, 2006, Migración internacional y desarrollo,Informe del Secretario General, General Assembly May 18th, 2006.PORTER, Eduardo, 2004, Shortage of seasonal workers is feared, The New York Times,April 10th, 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/10/business/10visa.html.RURAL COALITION POLICY CENTER. The history of U.S. policies toward the Mexicanagricultural worker and the impact of new legislation, Electronic document consultedin 2003 at: http://www.ruralco.org/html/policy/guestwork.htm.SISKIND, Gregory, 2004, Understanding the H-2B cap, Immigration Daily, ilw.com,March 18th, 2004, http://www.ilw.com/articles/2004,0318-siskind.shtm.U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, 2005, “USCIS to accept additionalH-2B filings for FY 2005 and 2006”, Press Office, USCIS, Office of Communications, May23rd, 2005.U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, varios años, Yearbook of immigrationstatistics, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.VERNEZ, and Ronfeldt, 1991, “The current situation in mexican immigration”, in Science,American Association for the Advancement of Science.WALLER MEYERS, Deborah, 2006, “Temporary worker programs: a patchwork policyresponse”, in Migration Policy Institute, Insight num. 12, January 2006, https://secure2.convio.net/ mpi/site/ Ecommerce/266085274?store_id=1241&product_id=1621&VIEW_PRODUCT=true.WASSEM, Ruth Ellen, and Collver, Geoffrey, 2001, Immigration of agricultural guestworkers: policy, trends and legislative issues, reported prepared for the CongressionalResearch Service, United States, http://www.ncseonline.org/NLE/CRSreports/Agriculture/ag-102.cfm.