central services - signalling projects group - dickthesignals.co.uk

G-protein-coupled receptors signalling at the cell nucleus: an emerging paradigmThis paper is one of...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of G-protein-coupled receptors signalling at the cell nucleus: an emerging paradigmThis paper is one of...

MINIREVIEW / MINISYNTHESE

G-protein-coupled receptors signalling at the cellnucleus: an emerging paradigm1

Fernand Gobeil Jr., Audrey Fortier, Tang Zhu, Michela Bossolasco, Martin Leduc,Michel Grandbois, Nikolaus Heveker, Ghassan Bkaily, Sylvain Chemtob, andDavid Barbaz

Abstract: G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) comprise a wide family of monomeric heptahelical glycoproteins that rec-ognize a broad array of extracellular mediators including cationic amines, lipids, peptides, proteins, and sensory agents.Thus far, much attention has been given towards the comprehension of intracellular signaling mechanisms activated bycell membrane GPCRs, which convert extracellular hormonal stimuli into acute, non-genomic (e.g., hormone secretion,muscle contraction, and cell metabolism) and delayed, genomic biological responses (e.g., cell division, proliferation, andapoptosis). However, with respect to the latter response, there is compelling evidence for a novel intracrine mode of ge-nomic regulation by GPCRs that implies either the endocytosis and nuclear translocation of peripheral-liganded GPCR and(or) the activation of nuclearly located GPCR by endogenously produced, nonsecreted ligands. A noteworthy example ofthe last scenario is given by heptahelical receptors that are activated by bioactive lipoids (e.g., PGE2 and PAF), many ofwhich may be formed from bilayer membranes including those of the nucleus. The experimental evidence for the nuclearlocalization and signalling of GPCRs will be reviewed. We will also discuss possible molecular mechanisms responsiblefor the atypical compartmentalization of GPCRs at the cell nucleus, along with their role in gene expression.

Key words: ligands, receptors, cell nucleus, signal transduction, gene transcription.

Resume : Les recepteurs couples aux proteines G (RCPG) font partie d’une grande famille de glycoproteines heptahelicesmonomeriques qui reconnaissent un large eventail de mediateurs extracellulaires comprenant les acides cationiques, les li-pides, les peptides, les proteines et les agents sensoriels. Jusqu’a present, une grande attention a ete accordee a la compre-hension des mecanismes de signalisation intracellulaire actives par les RCPG membranaires, qui convertissent les stimulihormonaux extracellulaires en reponses biologiques aigues, non genomiques (e.g., secretion hormonale, contraction muscu-laire et metabolisme cellulaire) et en reponses biologiques genomiques retardees (e.g., division cellulaire, proliferation etapoptose). Toutefois, en ce qui concerne le dernier point, il existe des arguments probants en faveur d’un nouveau modede regulation genomique intracrine par les RCPG, qui implique l’endocytose et la translocation des RCPG peripheriquesinduits par un ligand et (ou) l’activation des RCPG situes dans la partie nucleaire par des ligands non secretes, produits demaniere endogene. Un excellent exemple du dernier scenario est donne par les recepteurs heptahelices qui sont actives parles lipoıdes bioactifs (e.g., PGE2, PAF), dont une grande quantite pourrait etre formee a partir des membranes a doublecouche y compris celles du noyau. Nous ferons une synthese des donnees experimentales relatives a la localization et a lasignalisation nucleaires des RCPG. Nous discuterons aussi des mecanismes moleculaires qui pourraient etre responsablesde la compartimentation atypique des RCPG au niveau du noyau cellulaire, ainsi que de leur role dans l’expression ge-nique.

Mots cles : ligands, recepteurs, noyau cellulaire, transduction du signal, transcription genique.

[Traduit par la Redaction]

Received 19 August 2005. Published on the NRC Research Press Web site at http://cjpp.nrc.ca on 10 May 2006.

F. Gobeil Jr,2 A. Fortier, M. Grandbois, and D. Barbaz. Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Universite deSherbrooke, 3001, 12th North Avenue, Fleurimont, QC J1H 5N4, Canada.T. Zhu, M. Bossolasco, M. Leduc, N. Heveker, and S. Chemtob. Department of Pediatric, Ophthalmology and Pharmacology,Research Centre of Hopital Sainte-Justine, Universite de Montreal, Montreal, QC H3T 1C5, Canada.G. Bkaily. Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Universite de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC J1H 5N4,Canada.

1This paper is one of a selection of papers published in this Special Issue, entitled The Nucleus: A Cell Within A Cell.2Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]).

287

Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84: 287–297 (2006) doi: 10.1139/Y05-127 # 2006 NRC Canada

Introduction

According to the current state of knowledge, heptahelicaltransmembrane GPCRs are viewed as cell surface functionalentities that recognize extracellular stimulants of diverse na-ture. Upon activation by ligand binding, these receptors cou-ple to heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins(G-proteins), which relay signals to multiple downstreamsignaling pathways via dissociation of their a and b/g subu-nit complex. The theory of the subunit dissociation require-ment for G protein activation is, however, not universal(Willard and Crouch 2000). a and b/g subunits specificallymediate signalling via downstream effectors (enzymes, ionchannels) that alter the production of second messenger mol-ecules like inositol triphosphates, diacylglycerol, calcium,cAMP, and cGMP. These second messengers may partici-pate in the acute (e.g., hormone secretion, muscle contrac-tion, and cell metabolism) as well as the delayed, mostlygenomic, responses (e.g., cell division, proliferation, andapoptosis) mediated by GPCRs. The following section willbriefly summarize our current understanding of the molecu-lar aspects involved in converting the hormonal stimulusinto a transcription response.

The mechanistic bases on which GPCRs regulate geneexpression appear exceedingly complex and are not yetwell understood. With the exception, perhaps, of cAMP/PKA-dependent CREB pathway, the control of gene expres-sion by GPCRs relates, quasi exclusively, on the traditionalmodel of signal transduction by cytosolic mitogen-activatedprotein kinases (MAPK) with subsequent shuttling of tran-scription factors to the nucleus (Pierce et al. 2001; Yang etal. 2003). Current evidence has demonstrated that mamma-lian MAPK are ubiquitous enzymes exhibiting distinct sub-cellular distribution and whose activities are tightlycontrolled by a series of scaffolding factors (Chang andKarin 2001; Yang et al. 2003). Consequently, a number ofstudies have recently emerged offering alternative comple-mentary pathways for MAPK regulation and signalling(Chang and Karin 2001; Yang et al. 2003). In this context,a novel mechanism for GPCR signalling in MAPK-depend-ent gene activation that virtually bypasses the classical sec-ond-messenger pathways has been put forward (Daub et al.1997; Pierce et al. 2001). This distinctive pathway includesmetalloprotease-dependent transactivation of receptor tyro-sine kinases involving de novo release of their ligand(e.g., epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growthfactor (FGF)) by receptor endocytosis-associated b-arrestin-c-Src interaction leading ultimately to activation of Rasand MAPK. Such a mechanism has been broadly evi-denced in vitro for the endothelin, bombesin, thrombin, an-giotensin, lysophosphatidic acid, and muscarinic receptors(Daub et al. 1997; Pierce et al. 2001) and in vivo for theangiotensin receptors (Voisin et al. 2002).

There are other complementary pathways that have gainedprominence and that bolster the concept of heterogeneousGPCR regulatory mechanisms implicated in gene expres-sion. A number of independent studies have uncovered anunusual mode of cell signalling by peptide and, more re-cently, lipid ligands via intracrine actions (Re 1999; Gobeilet al. 2002, 2003a, 2003b; Marrache et al. 2004). In the ma-jority of these studies, the novel localization of nuclear

GPCRs has been proposed to be essential for many cellularregulatory processes including gene transcription, enhance-ment, or inhibition of effects elicited by cell surface receptoractivation, cell proliferation, and trophicity (for explicit andcomprehensive reviews on this topic, see Re 1999, 2001).Thus far, this peculiar type of intracellular signalling as-cribes to the endocytosis and nuclear translocation of periph-eral liganded GPCRs or the activation of nuclearly locatedGPCRs by endogenously produced non-secreted ligands (Re1999). Both of these novel perspectives, as detailed in thesucceeding sections, add a further layer of intricacy to thestudy of GPCR-coupled signal transduction associated withgene activation.

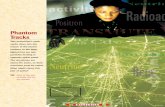

Heptahelical receptors at the cell nucleus

Several independent studies (of varying quality and co-gency) have suggested that heptahelical receptors for differ-ent classes of ligands can localize at the plasma membraneand cell nucleus. The emerging paradigm of the novel local-ization and functionality of nuclear GPCRs is based upon invivo and in vitro experimental evidence supported by immu-nohistology using electron and fluorescence microscopy ofdifferent tissues, normal and transformed (cancer) cell line-ages, by autoradiographic experiments with specific radioli-gands injected systemically in the whole animal, and (or) byligand binding or functional assays on intact tissues andcells and (or) nuclei isolated thereof (Table 1). One couldfind evidence for the 3 families of GPCRs in support of theatypical nuclear location of heptahelical receptors (Table 1).In this regard, using flow cytometry and confocal micro-scopy techniques, we were able to detect the spontaneousnuclear localization of endogenous chemokine receptorCXCR4 in purified nuclei from cultured HeLa cells(Fig. 1A and 1B). Such nuclear localization of CXCR4 haspreviously been detected by immunohistochemistry in vari-ous cancer tissues, namely hepatocellular carcinoma (Shi-buta et al. 2002), nonsmall cell lung cancer (Spano et al.2004), and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Wang et al. 2005).The fact that a variety of ligands can bind and regulate theactivity of nuclear GPCRs also points towards an intracellu-lar pool of receptors important in signalling distinct fromendoplasmic reticulum resident misfolded receptor proteinseventually undergoing degradation via the ubiquitin-protea-some system (Petaja-Repo et al. 2001).

Our group recently disclosed, by means of complementaryand multidisciplinary experimental approaches, the nuclearlocalization of functional GPCRs that are specific for prosta-glandins (PGE2) (Bhattacharya et al. 1998, 1999; Gobeil etal. 2002), platelet-activating factor (PAF) (Marrache et al.2002), lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) (Gobeil et al. 2003b),and apelin (Lee et al. 2004) in different cell types of cen-tral (brain) and peripheral (liver) organs. The use of high-resolution electron microscopy allowed us to identify withprecision their subnuclear distribution at both inner andouter nuclear membranes (PGE2-EP1 and LPA-LPA1)(Bhattacharya et al. 1998; Gobeil et al. 2003b) and, insome cases, within the nucleoplasm (LPA-LPA1 and PAF)of different cell types (Marrache et al. 2002; Gobeil et al.2003b). A number of recent independent studies have ele-gantly demonstrated by means of transmission electron and

288 Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Vol. 84, 2006

# 2006 NRC Canada

Table 1. Experimental evidence for the novel localization of nuclear GPCRs.

GPCR subfamilies Cell/tissue Species Method of detection References

Family 1ACh Corneas, corneal cells, CHO

cellsRabbit Autoradiographic ligand binding Lind and Cavanagh 1993,

1995Angiotensin II Vascular EC, VSMC,

cardiomyocytesRat Autoradiographic ligand binding Robertson and Khairallah

1971Liver Rat Chromatin solubility assay, radioligand binding Re et al. 1983, 1984Liver Rat Radioligand binding Booz et al. 1992Liver Rat Radioligand binding; gene transcription assay

(slot blot hybridization)Eggena et al. 1993, 1996

Brain cortex Rat IHC (Ang II) Erdmann et al. 1996Cardiomyocytes Rat Electrophysiological assay De Mello 1998VSMC Rat Ang II microinjection and Ca2+ assay Haller et al. 1999Brain, neuronal cells Rat ICC and Western blot (AT1) Lu et al. 1998VSMC Human ICC and Western blot (AT1); Ca2+ assay Bkaily et al. 2003a

Apelin Cerebellum, transfected D283cells

Human IHC, ICC, and Western blot (ApelinR) Lee et al. 2004

Chemokine CXCL12 Hepatoma, HT 29 cells Human IHC (CXCR4) Shibuta et al. 2002NSCLC Human IHC (CXCR4) Spano et al. 2004Hela cells Human ICC (CXCR4) Present study

Dynorphin B Cardiomyocytes Hamster Radioligand binding; PKC activity and genetranscription assay (RPA)

Ventura et al. 1998

Endothelin-1 Liver Rat Radioligand binding Hocher et al. 1992VSMC Human Ca2+ assay Bkaily et al. 2000Cardiomyocytes, brain Canine, rat ICC and Western blot (ETB); PKC activity and

Ca2+ assayBoivin et al. 2003

EEC Human ICC (ET-1, ETB); Ca2+ assay Jacques et al. 2005Leukotriene D4 Colorectal cancer, Int 407 and

CaCO-2 cellsIHC, ICC, and Western blot (CysLT1); Ca2+

assayNielsen et al. 2005

LPA CMVEC, liver, transfectedHTC4 cells

Porcine, rat radioligand binding; IHC, ICC, and Westernblot (LPA1); Ca2+ assay, Akt activation, genetranscription (RT-PCR) and eNOS activity

Gobeil et al. 2003b, 2006

NPY Pituitary cells Rat ICC (NPY) Chabot et al. 1988EEC Human ICC (NPY1); RIA for NPY; Ca2+ assay Jacques et al. 2003

PAF Liver Rat DAG production assay Miguel et al. 2001Brain, CMVEC, transfected

CHO cellsPorcine radioligand binding; IHC, ICC, and flow cyto-

metry (PAFR); RIA (PAF); Ca2+ assay,cAMP and IP3 production, NFkB binding,gene transcription (RT-PCR)

Marrache et al. 2002

Prolactin Liver Rat PKC activity Buckley et al. 1988Prostaglandin E2 Brain, myometrium, transfected

HEK293 and Swiss 3T3 cellsRadioligand binding; ICC and IHC (EP1); Ca2+

assay and gene transcription (RNA hybridi-zation)

Bhattacharya et al. 1998

Brain, liver Porcine, rat Radioligand binding; Western blot (EP3a, EP4),ICC (EP3a, EP4); Ca2+ assay and gene tran-scription assay (RNA hybridization)

Bhattacharya et al. 1999

CMVEC Porcine EP3 functional assays: MAPK and Akt activa-tion, cAMP and IP3 production, Ca2+assayand gene transcription assay (RT-PCR)

Gobeil et al. 2002

Family 2PTH/PTHrP Osteoblast-like cells Mouse ICC (PTHrP) Henderson et al. 1995

Liver, kidney, gut, uterus, ovary Rat IHC (PTH1 and PTHrP); Western blot (PTH1) Watson et al. 2000aMC3T3-E1, UMR106, SaOS-2

cellsICC (PTH1) Watson et al. 2000b

Cartilage, osteoclast cells Red deer IHC, ICC and Western blot (PTH1), Faucheux et al. 2002

Family 3Glutamate Neuronal cells, transfected

HEK293 cellsMurine ICC and Western blot (mGLU5); Ca2+ assay O’Malley et al. 2003

Note: Classification of GPCRs based on their amino acid sequences (Bockaert and Pin 1999). VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells; EEC, endocardialendothelial cells; CMVEC, cerebral microvascular endothelial cells; RPA, RNase protection assay; RIA, radioimmunoassay; IHC, immunohistochemistry;ICC, immunocytochemistry; PAF, platelet-activating factor; NPY, neuropeptide Y; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; ACh, acetylcholine; PTH/PTHrP, parathyroidhormone/parathyroid hormone-related peptide; NSCLC, nonsmall-cell lung cancer; DAG, diacylglycerol; PKC, protein kinase C.

Gobeil Jr. et al. 289

# 2006 NRC Canada

confocal fluorescence microscopy that nuclei of manymammalian cells and tissues contain numerous channelsarising presumably either from the invagination of bothouter and inner nuclear envelopes (based on the presence

of multi-nuclear pore complexes) (Fricker et al. 1997; Luiet al. 1998; Echevarria et al. 2003; Lagace and Ridgway2005) or the inner nuclear membrane exclusively (Isaac etal. 2001). This novel concept of the existence of distinct,

Fig. 1. Constitutive nuclear localization of chemokine receptor CXCR4 in HeLa cells demonstrated by (A) flow cytometry and (B) laserscanning confocal microscopy. (A) Nuclei from cultured, unstarved, quasi confluent (80%) HeLa cells were isolated by cell fractionationusing the hypotonic/Nonidet P-40 lysis method (Gobeil et al. 2002). Purified nuclei were incubated for 30 min at 4 8C in phosphate-bufferedsaline (PBS) containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% goat serum, and anti-human CXCR4 monoclonal 44716 antibody (5 mg/mL) (R&DSystems; bold line) or monoclonal anti-mouse IgG2B isotype control/KLH antibody (5 mg/mL) (R&D Systems; thin line), followed by incu-bation with goat anti-mouse fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200) (Chemicon International, Temecula, Calif.). CXCR4 expres-sion was evaluated by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). (B) Purified HeLa nuclei prepared as indicatedabove were laid down on 3’-aminopropyltriethoxysilane coated glass slides, fixed with PBS plus 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, thenblocked and permeabilized with PBS – 5% fetal bovine serum – 5% goat serum – 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature.Nuclei were then stained for CXCR4 with monoclonal 44716 antibody (10 mg/mL) followed by goat anti-mouse fluorescein-conjugatedsecondary antibody (1:200). Nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodine (PI) dye (0.5 mg/mL). In a separate experiment, anti-CXCR4antibody was replaced by monoclonal anti-mouse IgG2B isotype control/KLH antibody. Samples were observed using a LSM 510 laserscanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Imaging from 1 z-axis optical midsection of a single nucleus is presented. Scale bar represents5 mm.

290 Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Vol. 84, 2006

# 2006 NRC Canada

dynamic tubular membranes within the nucleus, termed thenucleoplasmic reticulum and R-rings/nucleolar channel sys-tems, may reconcile the apparent nucleoplasmic localiza-tion previously observed for LPA and PAF (and other)GPCRs with their integral membranous association charac-teristics. These structural entities secluded within the nu-cleus that are induced by the phosphatidylcholine-formingenzyme phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-a and enrichedin inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (InsP3) receptors were shownto partake in fine-tuning the regulation of local calcium re-lease and signalling (Echevarria et al. 2003; Lagace andRidgway 2005). It is tempting to speculate that such mo-bile membranal foci are engaged in activating perinuclearand (or) nuclear GPCR and (or) participate in the spatio-temporal coordination of specific gene replication. This in-ference does not, however, exclude the possibility ofGPCRs being integrated in nonmembranous lipophilic do-mains (Wells and Marti 2002) and (or) engulfed in lipidvesicular sheds within the nucleus.

Breakdown and reformation of the nuclear envelope arenormal steps of cell division (Imai et al. 1997; Ellenberg etal. 1997; Wiese et al. 1997). The nuclear envelope disassem-bling process involves the formation of heterogeneousvesicles that bind onto the chromatins to seal the entirechromosome. Thus, one could speculate that the observedintranuclear PAF and LPA GPCRs ensue from the presenceof remnant nuclear membrane vesicles (bona fide bound tochromatin) trapped within nuclear ambient from previouscell division. However, the consistent intranuclear localiza-tion of immunoreactive LPA and PAF receptors in postmi-totic, nondividing cells (hepatocytes, neurons, andendothelial cells) argues against this possibility (Marracheet al. 2002; Gobeil et al. 2003b).

Stimulation of GPCRs can take place within the cell (Du-mont et al. 1999; Gobeil et al. 2002). A noteworthy exampleapplies to heptahelical receptors activated by bioactive lip-oids such as PGE2, PAF, and LPA since these ligands canbe formed from membranes, including that of the nucleus,in the proximity of their cognate receptors (D’Santos et al.1998; Gobeil et al. 2002, 2003a, 2003b; Marrache et al.2002; Vazquez-Tello et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2005). The waypeptides (and other nonlipid ligands) can be generated intra-cellularly and act as intracrine modulators of nuclear func-tions, if not captured from extracellular space, is still anunresolved issue, even though they can still be recognizedat the nuclear level using immunostaining techniques (e.g.,Ang II, ET-1, NPY, PTHrP) (Chabot et al. 1988; Hendersonet al. 1995; Erdmann et al. 1996; Watson et al. 2000a;Bkaily et al. 2003b; Jacques et al. 2003, 2005).

Nuclear GPCR functions and physiologicalrelevance

The inference of functional nuclear heptahelical receptorsfor miscellaneous ligands is supported by the presence of afull complement of downstream signal transduction compo-nents at the nuclear membranes and nucleoplasm includingG proteins (Gs, Gi/Go), enzyme effectors (phospholipasesA2, C, and D, PKC, PKA, adenylate cyclase, and eNOS),and ion channels (e.g., K+, Na+, Cl–, Ca2+, and Zn2+),pumps, and exchangers (Willard and Crouch 2000; Gobeil

et al. 2003a; Bkaily et al. 2003b; Marrache et al. 2004;Gobeil et al. 2005). In addition, other recently describedconstitutive effector molecules in the nucleus may intervenein receptor-signalling processes implicated in genetranscription-associated events. These include nuclear factorkappa B (NFkB) or Rel proteins (Marrache et al. 2002; Go-beil et al. 2002, 2003a, 2005), mitogen-activated proteinkinases (MAP kinase; Erk1, Erk2 and Erk3), and constitu-ents of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt system (Neri etal. 2002; Gobeil et al. 2003a, 2003b).

Stimulation of nuclear receptors by their cognate ligandsmodulates consecutively intranuclear Ca2+ fluxes, proteinkinase activity, and subsequent transcriptional regulation oftarget genes such as cfos, eNOS, COX-2, and iNOS in cul-tured brain microvascular endothelial cells (Bhattacharya etal. 1998, 1999; Gobeil et al. 2002; Marrache et al. 2002;Gobeil et al. 2003b). Along these lines, we have demon-strated that some nuclear receptors, notably EP3 and PAFR,exert distinct functions at the nucleus and plasma mem-brane, likely owing to coupling to different G proteins (Go-beil et al. 2002; Marrache et al. 2002). In this regard, weshowed that stimulation of intracellular PGE2 receptors byexogenous EP3 receptor selective agonist M&B28767, whichcrosses the plasma membrane by facilitated carrier-mediatedtransport through the prostaglandin transporter, leads to theup-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOSIII) in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, thereby in-creasing eNOS-dependent vasorelaxation to substance P oncerebral microvessels in situ (as assessed by video-imagingtechnique) (Gobeil et al. 2002, 2003a), whereas stimulationof cell surface EP3 is linked to acute contractile responses(Gobeil et al. 2002). To the best of our knowledge, this isthe first clear demonstration of the physiological relevanceof nuclear heptahelical receptors, beyond in cellulo models,in the control of gene expression that impacts on physiolog-ical regulation, specifically blood flow regulation in thiscase (Gobeil et al. 2002, 2003b; Hardy et al. 2005). A rolefor nuclear prostaglandin receptors in pregnancy and parturi-tion has also recently been proposed (Helliwell et al. 2004).

Nuclear import of cell surface heptahelicalreceptors

Several GPCRs have been detected in the perinuclear and(or) nuclear region following their activation and (or) inter-nalization upon extracellular treatment with their cognateagonists (e.g.,angiotensin-AT1 (Lu et al. 1998; Chen et al.2000; Bkaily et al. 2003a) and -AT2 (Senbonmatsu et al.2003), somatostatin-ST2 (Krisch et al. 1998), neurotensin-NT1 (Toy-Miou-Leong et al. 2004), and of late, LPA-LPA1receptors (Moughal et al. 2004)). The biological significanceof the unidirectional transfer of GPCRs to the nucleus is un-clear, but may be pertinent to bringing about full receptorsignalling activity reminiscent of the actions mediated byseveral growth factor and cytokine receptors in turning-onnuclear events (Re 1999; Stachowiak et al. 2003; Johnsonet al. 2004). Whether the phenomenon of GPCR emigrationfrom plasma membranes to perinuclear areas show a rela-tionship with the extent and (or) latency of ligand signallingin nuclear responses is not yet known. Lending support to aninstrumental role of receptor endocytosis in gene modulation

Gobeil Jr. et al. 291

# 2006 NRC Canada

is the prerequisite of internalization of somatostatin-receptorcomplexes for the transcriptional repression of growth hor-mone in the pituitary cell line AtT-20, which occurs inde-pendently of activation of the adenylate cyclase pathway(Sarret et al. 1999).

The endocytosis and nuclear relocalization of GPCRsmay be necessary for its transcriptional activity, as proposedfor angiotensin and PTHrP receptors (Re 1999, 2001; Clem-ens et al. 2001). Since the caveolar compartment plays apivotal role in the signalling propagation of these peptidesincluding other factors sharing growth-related activitiessuch as LPA (Goetzl and An 1998), and because a varietyof tyrosine-kinase receptors and effector molecules (e.g.,Ras, PKCa, MAP kinases, eNOS, etc.) are localized in cav-eolae (Anderson 1998), we tested the hypothesis that cav-eolae (and (or) so-called intermediate organellecaveosomes (Pelkmans et al. 2001)) are responsible forconveying the LPA-LPA1 GPCRs (liganded or not) to thenucleus where they modulate gene expression, notwith-standing the evidence that pointed out the kinetic immobil-ity of these organelles (Gratton et al. 2004). Indeed, thereare selected examples of single transmembrane receptorscontaining tyrosine kinase activities, suggesting that caveo-lae take part in the interorganelle transport and exchangeof ligand-receptor complexes to the nucleus. For instance,VEGF stimulated the translocation of its cognate receptorFlk-1/KDR as well as eNOS and caveolin-1 into the nu-cleus of vascular endothelial cells (Feng et al. 1999). More-over, it was demonstrated that the endocytosis and nucleartranslocation of the IFNg/IFNg-R1/STAT1a multimeric com-plex proceeds via filipin-sensitive caveolae-like microdo-mains in human amnion WISH cells (Subramaniam andJohnson 2002). On the other hand, we recently demonstrated,by means of caveolae-disrupting agents and sucrose hyper-tonic solution (for inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocyto-sis) that the sequestration and transcellular transport of LPA-R via caveolae- and clathrin-coated pits to the nucleus is nota prerequisite for LPA-R activity on gene expression in por-cine cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (Gobeil et al.2003b). Thus, it remains to be established whether the cav-eolar endocytic machinery represents a viable avenue for aportion of internalized ligand-GPCR complexes that have es-caped degradation or recycling to operate at the cell nucleus.

Possible mechanisms for GPCR nuclearhoming

A question that has to be answered is what determines theorigin of GPCR nuclear homing in a particular cell? Clearly,part of the answer depends upon the specific receptor sub-types and the cell type (Lee et al. 2004). The classical path-way of heptahelical receptor regulation and desensitizationmay be implicated in their relocalization (Ferguson 2001).Several researchers have proposed, although debatably, thatnuclear receptors are derived from the cell membrane(Yang et al. 1997; Lu et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2000; Re1999). The transfer of membrane receptors (liganded or not)to the nucleus could be attributed to the presence of a pep-tide sequence referred to as a nuclear localization signal(NLS). The classical and by far most well characterized mo-nopartite NLS, which consists of multiple basic amino acids

including lysine and arginine residues, was originally identi-fied in the SV40 large T antigen (Yoneda et al. 1999; Chris-tophe et al. 2000), whereas the archetype of the bipartitebasic-type NLS originates from a sequence of nucleoplasmin(Christophe et al. 2000). Limited number of GPCRs have aclearly recognizable NLS motif in the eighth helix (e.g., ad-enosine, growth hormone, motilin, purine, angiotensin, bra-dykinin, and endothelin receptors) and (or) in the thirdintracellular loops (e.g., apelin receptor) (Lee et al. 2004).NLS-bearing receptors may be directed to the nucleusthrough the Ran-GTP/importin mechanism (Christophe etal. 2000) as suggested recently for transmembrane EGF re-ceptors (Lin et al. 2001). Moreover, there seems to exist alarge variety of heterogeneous sequence motifs that bear noresemblance to classical basic type NLS but that can stillpromote import of proteins (Christophe et al. 2000). Alterna-tively, the receptors may be imported to the perinuclear and(or) nuclear regions in association with carrier proteins con-taining a basic NLS sequence. Such a possibility was ob-served for the transmembrane angiotensin II type 2receptor, which requires an association with the NLSbearing-transcription factor promyelocytic zinc finger pro-tein for phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase gene activation inmouse fibroblast-derived R3T3 cells (Senbonmatsu et al.2003; Kelly et al. 2004). Whereas in the case of PTHrP/PTH receptor, the NLS could be provided by its ligand(Henderson et al. 1995; Watson et al. 2000a; Lam et al.2000; Clemens et al. 2001).

There are other sequences confined within the internalloops and C-terminal segments of heptahelical receptorsthat could participate in receptor transport to and compart-mentalization at the nucleus; this is the case for the endo-plasmic retention sequence (Teasdale and Jackson 1996;Marrache et al. 2002). Lateral diffusion of newly synthe-sized membrane proteins may also constitute a mechanismby which heptahelical receptors at the rough endoplasmic re-ticulum locate at nuclear membranes (perinuclear area) con-tiguous with the former. In this regard, application ofphotobleaching methods such as fluorescence recovery afterphotobleaching and fluorescence loss in photobleachingshould detect changes in GPCR diffusion within the reticu-lum and (or) nuclear membranes, as reported for fluores-cent-tagged protein lamin B receptor targeted at the innernuclear membrane, independent of vesiculation (Ellenberget al. 1997). Investigations along these lines should reconcilethe translational mechanisms of heptahelical receptor bio-genesis from the endoplasmic reticulum (Hegde and Lin-gappa 1999; Kochl et al. 2002; Andersson et al. 2003).

Alternatively, a distribution of GPCRs from the Golgi net-work to specific sub-cellular regions can be postulated.Thus, there should be strong incentive towards researchareas focusing on the biogenesis, topology, and post-translational maturation of polytopic (multispanning) mem-brane proteins such as GPCRs. For instance, it is believedthat from the Golgi apparatus, vesicles are sorted out to dif-ferent subcompartments including the plasma membrane, thelysosome, and the nucleus. Hence, one must consider thatnuclear heptahelical receptors may derive from the Golgi ap-paratus, and that the specificity of compartmentalizationconfers distinct receptor functions. Along these lines, the ap-pearance of glycosylated receptors at the cell nucleus sug-

292 Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Vol. 84, 2006

# 2006 NRC Canada

gests that these proteins originate effectively from the Golgiapparatus or the plasma membrane following their internal-ization. It is known that N-glycosylation, a quasi-universalposttransductional modification among heptahelical recep-tors, modulates the cellular compartmentalization and (or)the functionality of these receptors (Wheatley and Hawtin1999). In this context, a mode of nuclear import dependenton glycosylation (and NLS-independent) for soluble glyco-proteins has been recently demonstrated (Duverger et al.1995; Rondanino et al. 2003). Whether this mode of trans-port prevails for the intracellular trafficking of GPCRs isnot known. On the other hand, our Western blot resultsshowing the occurrence of glycosylated and undegraded,nearly full-length immunoreactive PGE2-EP3, PAF-PAF1,and LPA-LPA1 GPCRs in highly purified nuclear fractionsof endothelial cells and hepatic tissues, comparable to thoseof cell membrane fractions, does not support this latter con-tention (Bhattacharya et al. 1999; Marrache et al. 2002; Go-beil et al. 2003b). This however does not exclude a role forglycosylation in intracellular GPCR distribution.

Spliced variants of numerous heptahelical receptors arealso known to be distributed differently (Kilpatrick et al.1999). In this respect, the PTH/PTHrP receptor gene uses al-ternate promoters in a tissue-specific manner resulting in al-ternatively spliced transcripts (Joun et al. 1997). A novelPTH/PTHrP receptor splice variant that lacks the signal pep-tide has been described and infers distinct compartmentali-zation (Joun et al. 1997). These contingencies should, inprinciple, lead to the detection of structurally divergentGPCR isoforms.

Conclusion

The concept that signalling of miscellaneous ligands(polypeptides, lipids, amino acid, etc.) could emerge at thelevel of specific subcellular regions expressing their cog-nate receptors, analogous to the steroid hormones actions(Scheller and Sekeris 2003; Thomas et al. 2005; Revankaret al. 2005) has gained much interest and appreciation inrecent years. The novel discovery of nuclear receptors fora broad array of ligands opens new avenues in the biologyof heptahelical receptors, notably in the manner in whichthey control gene transcription following activation and(or) inhibition by endogenous hormones and by xenobiot-ics, especially undersized nonpeptide antagonists, whichmay have access to cytosolic space and bind to these nu-clear sites (Haller et al. 1999). Future investigations areneeded (most importantly, in vivo) for an in depth knowl-edge of the biological roles of these receptors in bothphysiological and pathological conditions, as conclusionsemerging from these studies may have a major impact ontherapeutic drug development and impart a shift in treat-ment paradigm. In this regard, an increased proportion ofnuclear opioid k receptors, associated with a rise of nu-clear PKC activity upon their stimulation, were unravelledin an experimental animal model of primary hereditary hy-pertrophic cardiomyopathy (Ventura et al. 1998). Notewor-thy, the expression of nuclearized GPCR CXCR4 in cancercells (Shibuta et al. 2002; Spano et al. 2004) and CysLT1(Nielsen et al. 2005) in the clinical setting significantlycorrelates with prognosis. The augmented nuclear distribu-

tion of the above-mentioned GPCRs witnessed in cardio-vascular disease and cancer could unveil a crucialinvolvement of nuclear GPCRs in pro-survival and (or)proliferative pathways.

AcknowledgementsDr. Fernand Gobeil Jr. is recipient of a Junior 1 scholar-

ship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Sante du Quebec(FRSQ) and a researcher of the Canada Foundation for Inno-vation. This work was supported in part by the Heart andStroke Foundation of Quebec and the Canadian Institutes ofHealth Research grants.

ReferencesAnderson, R.G. 1998. The caveolae membrane system. Annu. Rev.

Biochem. 67: 199–225. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199.PMID: 9759488.

Andersson, H., D’Antona, A.M., Kendall, D.A., Von Heijne, G.,and Chin, C.N. 2003. Membrane assembly of the cannabinoidreceptor 1: impact of a long N-terminal tail. Mol. Pharmacol.64: 570–577. doi:10.1124/mol.64.3.570. PMID: 12920192.

Bhattacharya, M., Peri, K.G., Almazan, G., Ribeiro-da-Silva, A.,Shichi, H., Durocher, Y., et al. 1998. Nuclear localization ofprostaglandin E2 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95:15792–15797. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15792. PMID: 9861049.

Bhattacharya, M., Peri, K., Ribeiro-da-Silva, A., Almazan, G., Shi-chi, H., Hou, X., et al. 1999. Localization of functional prosta-glandin E2 receptors EP3 and EP4 in the nuclear envelope. J.Biol. Chem. 274: 15719–15724. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.22.15719.PMID: 10336471.

Bkaily, G., Choufani, S., Hassan, G., El-Bizri, N., Jacques, D., andD’Orleans-Juste, P. 2000. Presence of functional endothelin-1receptors in nuclear membranes of human aortic vascularsmooth muscle cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 36: S414–S417.PMID: 11078437.

Bkaily, G., Sleiman, S., Stephan, J., Asselin, C., Choufani, S., Ka-mal, M., et al. 2003a. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor internaliza-tion, translocation and de novo synthesis modulate cytosolicand nuclear calcium in human vascular smooth muscle cells.Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 81: 274–287. doi:10.1139/y03-007.PMID: 12733826.

Bkaily, G., Jacques, D., D’Orleans-Juste, P., Gobeil, F., Jr., Chem-tob, S., Choufani, S., and Nader, M. 2003b. Nuclear membraneschannels, exchangers and G-protein coupled receptors: a newtarget for drug action. Curr. Top. Pharmacol. 7: 269–278.

Bockaert, J., and Pin, J.P. 1999. Molecular tinkering of G protein-coupled receptors: an evolutionary success. EMBO J. 18: 1723–1729. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.7.1723. PMID: 10202136.

Boivin, B., Chevalier, D., Villeneuve, L.R., Rousseau, E., and Al-len, B.G. 2003. Functional endothelin receptors are present onnuclei in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:29153–29163. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301738200. PMID: 12756260.

Booz, G.W., Conrad, K.M., Hess, A.L., Singer, H.A., and Baker,K.M. 1992. Angiotensin-II-binding sites on hepatocyte nuclei.Endocrinology, 130: 3641–3649. doi:10.1210/en.130.6.3641.PMID: 1597161.

Buckley, A.R., Crowe, P.D., and Russell, D.H. 1988. Rapid activa-tion of protein kinase C in isolated rat liver nuclei by prolactin,a known hepatic mitogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85:8649–8653. PMID: 3186750.

Chabot, J.G., Enjalbert, A., Pelletier, G., Dubois, P.M., and Morel,G. 1988. Evidence for a direct action of neuropeptide Y in the

Gobeil Jr. et al. 293

# 2006 NRC Canada

rat pituitary gland. Neuroendocrinology, 47: 511–517. PMID:3399034.

Chang, L., and Karin, M. 2001. Mammalian MAP kinase signalingcascades. Nature, 410: 37–40. doi:10.1038/35065000. PMID:11242034.

Chen, R., Mukhin, Y.V., Garnovskaya, M.N., Thielen, T.E., Iijima,Y., Huang, C., et al. 2000. A functional angiotensin II receptor-GFP fusion protein: evidence for agonist-dependent nucleartranslocation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 279: F440–F448.PMID: 10966923.

Christophe, D., Christophe-Hobertus, C., and Pichon, B. 2000. Nu-clear targeting of proteins: how many different signals. Cell.Signal. 12: 337–341. doi:10.1016/S0898-6568(00)00077-2.PMID: 10822175.

Clemens, T.L., Cormier, S., Eichinger, A., Endlich, K., Fiaschi-Taesch, N., Fischer, E., et al. 2001. Parathyroid hormone-relatedprotein and its receptors: nuclear functions and roles in the renaland cardiovascular systems, the placental trophoblasts and thepancreatic islets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 134: 1113–1136. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704378. PMID: 11704631.

Daub, H., Wallasch, C., Lankenau, A., Herrlich, A., and Ullrich, A.1997. Signal characteristics of G protein-transactivated EGF re-ceptor. EMBO J. 16: 7032–7044. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.23.7032.PMID: 9384582.

De Mello, W.C. 1998. Intracellular angiotensin II regulates the in-ward calcium current in cardiac myocytes. Hypertension, 32:976–982. PMID: 9856960.

D’Santos, C.S., Clarke, J.H., and Divecha, N. 1998. Phospholipidsignalling in the nucleus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1436: 201–232. PMID: 9838115.

Dumont, I., Hou, X., Hardy, P., Peri, K.G., Beauchamp, M., Najar-ian, T., et al. 1999. Developmental regulation of endothelial ni-tric oxide synthase in cerebral vessels of newborn pig byprostaglandin E(2). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 291: 627–633.PMID: 10525081.

Duverger, E., Pellerin-Mendes, C., Mayer, R., Roche, A.C., andMonsigny, M. 1995. Nuclear import of glycoconjugates is dis-tinct from the classical NLS pathway. J. Cell Sci. 108: 1325–1332. PMID: 7615655.

Echevarria, W., Leite, M.F., Guerra, M.T., Zipfel, W.R., andNathanson, M.H. 2003. Regulation of calcium signals in the nu-cleus by a nucleoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 440–446.PMID: 12717445.

Eggena, P., Zhu, J.H., Clegg, K., and Barrett, J.D. 1993. Nuclearangiotensin receptors induce transcription of renin and angioten-sinogen mRNA. Hypertension, 22: 496–501. PMID: 8406654.

Eggena, P., Zhu, J.H., Sereevinyayut, S., Giordani, M., Clegg, K.,Andersen, P.C., et al. 1996. Hepatic angiotensin II nuclear re-ceptors and transcription of growth-related factors. J. Hypertens.14: 961–968. PMID: 8884550.

Ellenberg, J., Siggia, E.D., Moreira, J.E., Smith, C.L., Presley, J.F.,Worman, H.J., and Lippincott-Schwartz, J. 1997. Nuclear mem-brane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of aninner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J.Cell Biol. 138: 1193–1206. doi:10.1083/jcb.138.6.1193. PMID:9298976.

Erdmann, B., Fuxe, K., and Ganten, D. 1996. Subcellular localiza-tion of angiotensin II immunoreactivity in the rat cerebellar cor-tex. Hypertension, 28: 818–824. PMID: 8901829.

Faucheux, C., Horton, M.A., and Price, J.S. 2002. Nuclear localiza-tion of type I parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-relatedprotein receptors in deer antler osteoclasts: evidence for para-thyroid hormone-related protein and receptor activator of NF-kappaB-dependent effects on osteoclast formation in regenerat-

ing mammalian bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 17: 455–464. PMID:11874237.

Feng, Y., Venema, V.J., Venema, R.C., Tsai, N., and Caldwell,R.B. 1999. VEGF induces nuclear translocation of Flk-1/KDR,endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and caveolin-1 in vascular en-dothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256: 192–197.doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.9790. PMID: 10066445.

Ferguson, S.S.G. 2001. Evolving concepts in G protein coupled-re-ceptor endocytosis: The role in receptor desensitization and sig-nalling. Pharmacol. Rev. 53: 1–24. PMID: 11171937.

Fricker, M., Hollinshead, M., White, N., and Vaux, D. 1997. Inter-phase nuclei of many mammalian cell types contain deep, dy-namic, tubular membrane-bound invaginations of the nuclearenvelope. J. Cell Biol. 136: 531–544. doi:10.1083/jcb.136.3.531.PMID: 9024685.

Gobeil, F., Jr., Dumont, I., Marrache, A.M., Vazquez-Tello, A.,Bernier, S.G., Abran, D., et al. 2002. Regulation of eNOS ex-pression in brain endothelial cells by perinuclear EP(3) recep-tors. Circ. Res. 90: 682–689. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000013303.17964.7A. PMID: 11934836.

Gobeil, F., Jr., Vazquez-Tello, A., Marrache, A.M., Bhattacharya,M., Checchin, D., Bkaily, G., et al. 2003a. Nuclear prostaglandinsignaling system: biogenesis and actions via heptahelical recep-tors. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 81: 196–204. PMID: 12710534.

Gobeil, F., Jr., Bernier, S.G., Vazquez-Tello, A., Brault, S., Beau-champ, M.H., Quiniou, C., et al. 2003b. Modulation of pro-in-flammatory gene expression by nuclear lysophosphatidic acidreceptor type-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 38875–38883. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212481200. PMID: 12847111.

Gobeil, F., Jr., Zhu, T., Brault, S., Geha, A., Vazquez-Tello, A.,and Fortier, A., et al. 2006. Nitric oxide signaling via nuclear-ized e-NOS in the expression of immediate early genes i-NOSand mPGES-1. J. Biol. Chem. 281: In press. PMID: 16574649.

Goetzl, E.J., and An, S. 1998. Diversity of cellular receptors andfunctions for the lysophospholipid growth factors lysophosphati-dic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate. FASEB J. 12: 1589–1598.PMID: 9837849.

Gratton, J.P., Bernatchez, P., and Sessa, W.C. 2004. Caveolae andcaveolins in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 94: 1408–1417.doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000129178.56294.17. PMID: 15192036.

Haller, H., Lindschau, C., Quass, P., and Luft, F.C. 1999. Intracel-lular actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J.Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10: S75–S83. PMID: 9892144.

Hardy, P., Beauchamp, M., Sennlaub, F., Gobeil, F., Jr., Tremblay,L., Mwaikambo, B., et al. 2005. New insights into the retinalcirculation: inflammatory lipid mediators in ischemic retinopa-thy. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids, 72: 301–325.doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2005.02.004. PMID: 15850712.

Hegde, R.S., and Lingappa, V.R. 1999. Regulation of protein bio-genesis at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Trends CellBiol. 9: 132–137. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01504-4. PMID:10203789.

Helliwell, R.J., Berry, E.B., O’Carroll, S.J., and Mitchell, M.D.2004. Nuclear prostaglandin receptors: role in pregnancy andparturition? Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids, 70:149–165. doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2003.04.005. PMID: 14683690.

Henderson, J.E., Amizuka, N., Warshawsky, H., Biasotto, D.,Lanske, B.M., Goltzman, D., and Karaplis, A.C. 1995. Nucleo-lar localization of parathyroid hormone-related peptide en-hances survival of chondrocytes under conditions that promoteapoptotic cell death. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 4064–4075. PMID:7623802.

Hocher, B., Rubens, C., Hensen, J., Gross, P., and Bauer, C. 1992.Intracellular distribution of endothelin-1 receptors in rat liver

294 Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Vol. 84, 2006

# 2006 NRC Canada

cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 184: 498–503 doi:.10.1016/0006–291X(92)91222-C

Imai, N., Sasagawa, S., Yamamoto, A., Kikuchi, F., Sekiya, K.,Ichimura, T., et al. 1997. Characterization of the binding of nu-clear envelope precursor vesicles and chromatin, and purifica-tion of the vesicles. J. Biochem. (Tokyo), 122: 1024–1033.PMID: 9443820.

Isaac, C., Pollard, J.W., and Meier, U.T. 2001. Intranuclear endo-plasmic reticulum induced by Nopp140 mimics the nucleolarchannel system of human endometrium. J. Cell Sci. 114: 4253–4264. PMID: 11739657.

Jacques, D., Sader, S., Perreault, C., Fournier, A., Pelletier, G.,Beck-Sickinger, A.G., and Descorbeth, M. 2003. Presence ofneuropeptide Y and the Y1 receptor in the plasma membraneand nuclear envelope of human endocardial endothelial cells:modulation of intracellular calcium. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol.81: 288–300. doi:10.1139/y02-165. PMID: 12733827.

Jacques, D., Descorbeth, M., Abdel-Samad, D., Provost, C., Per-reault, C., and Jules, F. 2005. The distribution and density ofET-1 and its receptors are different in human right and left ven-tricular endocardial endothelial cells. Peptides, 26: 1427–1435.doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.048. PMID: 16042982.

Johnson, H.M., Subramaniam, P.S., Olsnes, S., and Jans, D.A.2004. Trafficking and signaling pathways of nuclear localizingprotein ligands and their receptors. Bioessays, 26: 993–1004.doi:10.1002/bies.20086. PMID: 15351969.

Joun, H., Lanske, B., Karperien, M., Qian, F., Defize, L., and Abou-Samra, A. 1997. Tissue-specific transcription start sites and alter-native splicing of the parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-relatedpeptide (PTHrP) receptor gene: a new PTH/PTHrP receptorsplice variant that lacks the signal peptide. Endocrinology, 138:1742–1749. doi:10.1210/en.138.4.1742. PMID: 9075739.

Kelly, K.F., Otchere, A.A., Graham, M., and Daniel, J.M. 2004.Nuclear import of the BTB/POZ transcriptional regulator Kaiso.J. Cell Sci. 117: 6143–6152. doi:10.1242/jcs.01541. PMID:15564377.

Kilpatrick, G.J., Dautzenberg, F.M., Martin, G.R., and Eglen, R.M.1999. 7TM receptors: the splicing on the cake. Trends Pharma-col. Sci. 20: 294–301. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01355-3.PMID: 10390648.

Kochl, R., Alken, M., Rutz, C., Krause, G., Oksche, A., Rosanthal,W., and Schulein, R. 2002. The signal peptide of the G protein-coupled human endothelin B receptor is necessary for transloca-tion of the N-terminal tail across the endoplasmic reticulummembrane. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 16131–16138. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111674200. PMID: 11854280.

Krisch, B., Feindt, J., and Mentlein, R. 1998. Immunoelectronmi-croscopic analysis of the ligand-induced internalization of thesomatostatin receptor subtype 2 in cultured human glioma cells.J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46: 1233–1242. PMID: 9774622.

Lagace, T.A., and Ridgway, N.D. 2005. The rate-limiting enzymein phosphatidylcholine synthesis regulates proliferation of thenucleoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell, 16: 1120–1130.doi:10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0874. PMID: 15635091.

Lam, M.H., Thomas, R.J., Martin, T.J., Gillespie, M.T., and Jans,D.A. 2000. Nuclear and nucleolar localization of parathyroidhormone-related protein. Immunol. Cell Biol. 78: 395–402.doi:10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00919.x. PMID: 10947864.

Lee, D.K., Lanca, A.J., Cheng, R., Nguyen, T., Ji, X.D., Gobeil, F.,Jr., et al. 2004. Agonist-independent nuclear localization of theApelin, angiotensin AT1, and bradykinin B2 receptors. J. Biol.Chem. 279: 7901–7908. PMID: 14645236.

Lin, S.Y., Makino, K., Xia, W., Matin, A., Wen, Y., Kwong, K.Y.,et al. 2001. Nuclear localization of EGF receptor and its poten-

tial new role as a transcription factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 802–808. doi:10.1038/ncb0901-802. PMID: 11533659.

Lind, G.J., and Cavanagh, H.D. 1993. Nuclear muscarinic acetyl-choline receptors in corneal cells from rabbit. Invest. Ophthal-mol. Vis. Sci. 34: 2943–2952. PMID: 8360027.

Lind, G.J., and Cavanagh, H.D. 1995. Identification and subcellulardistribution of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-related proteinsin rabbit corneal and Chinese hamster ovary cells. Invest.Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 36: 1492–1507. PMID: 7601630.

Lu, D., Yang, H., Shaw, G., and Raizada, M.K. 1998. AngiotensinII-induced nuclear targeting of the angiotensin type 1 (AT1) re-ceptor in brain neurons. Endocrinology, 139: 365–375. doi:10.1210/en.139.1.365. PMID: 9421435.

Lui, P.P., Lee, C.Y., Tsang, D., and Kong, S.K. 1998. Ca2+ is re-leased from the nuclear tubular structure into nucleoplasm in C6glioma cells after stimulation with phorbol ester. FEBS Lett. 432:82–87. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00838-2. PMID: 9710256.

Marrache, A.M., Gobeil, F., Jr., Bernier, S.G., Stankova, J., Rola-Pleszczynski, M., Choufani, S., et al. 2002. Proinflammatorygene induction by platelet-activating factor mediated via its cog-nate nuclear receptor. J. Immunol. 169: 6474–6481. PMID:12444157.

Marrache, A.M., Gobeil, F., Jr., and Chemtob, S. 2004. Intracrinesignaling of phospholipid mediators, via cognate nuclear G pro-tein-coupled receptors. Gene Ther. Mol. Biol. 8: 115–124.

Miguel, B.G., Calcerrada, M.C., Martin, L., Catalan, R.E., andMartinez, A.M. 2001. Increase of phosphoinositide hydrolysisand diacylglycerol production by PAF in isolated rat liver nu-clei. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 65: 159–166. PMID:11444588.

Moughal, N.A., Waters, C., Sambi, B., Pyne, S., and Pyne, N.J.2004. Nerve growth factor signaling involves interaction be-tween the Trk A receptor and lysophosphatidate receptor 1 sys-tems: nuclear translocation of the lysophosphatidate receptor 1and Trk A receptors in pheochromocytoma 12 cells. Cell. Sig-nal. 16: 127–136. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.08.004. PMID:14607283.

Neri, L.M., Borgatti, P., Capitani, S., and Martelli, A.M. 2002. Thenuclear phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway: a new secondmessenger system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1584: 73–80.PMID: 12385889.

Nielsen, C.K., Campbell, J.I., Ohd, J.F., Morgelin, M., Riesbeck,K., Landberg, G., and Sjolander, A. 2005. A novel localizationof the G-protein-coupled CysLT1 receptor in the nucleus of col-orectal adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 65: 732–742. PMID:15705869.

O’Malley, K.L., Jong, Y.J., Gonchar, Y., Burkhalter, A., and Ro-mano, C. 2003. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptormGlu5 on nuclear membranes mediates intranuclear Ca2+

changes in heterologous cell types and neurons. J. Biol. Chem.278: 28210–28219. doi:10.1074/jbc.M300792200. PMID:12736269.

Pelkmans, L., Kartenbeck, J., and Helenius, A. 2001. Caveolar en-docytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 473–483. doi:10.1038/35074539. PMID: 11331875.

Petaja-Repo, U.E., Hogue, M., Laperriere, A., Bhalla, S., Walker,P., and Bouvier, M. 2001. Newly synthesized human deltaopioid receptors retained in the endoplasmic reticulum are retro-translocated to the cytosol, deglycosylated, ubiquitinated, anddegraded by the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 4416–4423.doi:10.1074/jbc.M007151200. PMID: 11054417.

Pierce, K.L., Luttrell, L.M., and Lefkowitz, R.J. 2001. New me-chanisms in heptahelical receptor signaling to mitogen activated

Gobeil Jr. et al. 295

# 2006 NRC Canada

protein kinase cascades. Oncogene, 20: 1532–1539. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204184. PMID: 11313899.

Re, R. 1999. The nature of intracrine peptide hormone action. Hy-pertension, 34: 534–538. PMID: 10523322.

Re, R.N. 2001. The clinical implication of tissue renin angiotensinsystems. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 16: 317–327. doi:10.1097/00001573-200111000-00002. PMID: 11704700.

Re, R.N., LaBiche, R.A., and Bryan, S.E. 1983. Nuclear-hormonemediated changes in chromatin solubility. Biochem. Biophys.Res. Commun. 110: 61–68 doi:. 10.1016/0006–291X(83)91260–3

Re, R.N., Vizard, D.L., Brown, J., and Bryan, S.E. 1984. Angioten-sin II receptors in chromatin fragments generated by micrococ-cal nuclease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 119: 220–227doi:. 10.1016/0006–291X(84)91641–3

Revankar, C.M., Cimino, D.F., Sklar, L.A., Arterburn, J.B., andProssnitz, E.R. 2005. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen re-ceptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science, 307: 1625–1630.doi:10.1126/science.1106943. PMID: 15705806.

Robertson, A.L., Jr., and Khairallah, P.A. 1971. Angiotensin II: ra-pid localization in nuclei of smooth and cardiac muscle.Science, 172: 1138–1139. PMID: 4324923.

Rondanino, C., Bousser, M.T., Monsigny, M., and Roche, A.C.2003. Sugar-dependent nuclear import of glycosylated proteinsin living cells. Glycobiology, 13: 509–519. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwg064. PMID: 12672698.

Sarret, P., Nouel, D., Dal Farra, C., Vincent, J.P., Beaudet, A., andMazella, J. 1999. Receptor-mediated internalization is criticalfor the inhibition of the expression of growth hormone by soma-tostatin in the pituitary cell line AtT-20. J. Biol. Chem. 274:19294–19300. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.27.19294. PMID: 10383439.

Scheller, K., and Sekeris, C.E. 2003. The effects of steroid hor-mones on the transcription of genes encoding enzymes of oxida-tive phosphorylation. Exp. Physiol. 88: 129–140. doi:10.1113/eph8802507. PMID: 12525861.

Senbonmatsu, T., Saito, T., Landon, E.J., Watanabe, O., Price, E.,Jr., Roberts, R.L., et al. 2003. A novel angiotensin II type 2 re-ceptor signaling pathway: possible role in cardiac hypertrophy.EMBO J. 22: 6471–6482. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg637. PMID:14657020.

Shibuta, K., Mori, M., Shimoda, K., Inoue, H., Mitra, P., and Bar-nard, G.F. 2002. Regional expression of CXCL12/CXCR4 in li-ver and hepatocellular carcinoma and cell-cycle variation duringin vitro differentiation. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 93: 789–797. PMID:12149145.

Spano, J.P., Andre, F., Morat, L., Sabatier, L., Besse, B., Comba-diere, C., et al. 2004. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 and early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: pattern of expression and cor-relation with outcome. Ann. Oncol. 15: 613–617. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh136. PMID: 15033669.

Stachowiak, M.K., Fang, X., Myers, J.M., Dunham, S.M., Berez-ney, R., Maher, P.A., and Stachowiak, E.K. 2003. Integrativenuclear FGFR1 signaling (INFS) as a part of a universal ’’feed-forward-and gate’’ signaling module that controls cell growthand differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 90: 662–691. doi:10.1002/jcb.10606. PMID: 14587025.

Subramaniam, P.S., and Johnson, H.M. 2002. Lipid microdomainsare required sites for the selective endocytosis and nuclear trans-location of IFN-gamma, its receptor chain IFN-gamma receptor-1, and the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STA-T1alpha. J. Immunol. 169: 1959–1969. PMID: 12165521.

Teasdale, R.D., and Jackson, M.R. 1996. Signal-mediated sortingof membrane proteins between the endoplasmic reticulum andthe golgi apparatus. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12: 27–54.doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.27. PMID: 8970721.

Thomas, P., Pang, Y., Filardo, E.J., and Dong, J. 2005. Identity ofan estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in humanbreast cancer cells. Endocrinology, 146: 624–632. PMID:15539556.

Toy-Miou-Leong, M., Bachelet, C.M., Pelaprat, D., Rostene, W.,and Forgez, P. 2004. NT agonist regulates expression of nuclearhigh-affinity neurotensin receptors. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 52:335–345. PMID: 14966200.

Vazquez-Tello, A., Fan, L., Hou, X., Joyal, J.S., Mancini, J.A.,Quiniou, C., et al. 2004. Intracellular-specific colocalization ofprostaglandin E2 synthases and cyclooxygenases in the brain.Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 287: R1155–R1163. PMID: 15284079.

Ventura, C., Maioli, M., Pintus, G., Posadino, A.M., and Tadolini,B. 1998. Nuclear opioid receptors activate opioid peptide genetranscription in isolated myocardial nuclei. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13383–13386. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.22.13383. PMID: 9593666.

Voisin, L., Foisy, S., Giasson, E., Lambert, C., Moreau, P., andMeloche, S. 2002. EGF receptor transactivation is obligatory forprotein synthesis stimulation by G protein-coupled receptors.Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283: C446–C455. PMID:12107054.

Wang, N., Wu, Q.L., Fang, Y., Mai, H.Q., Zeng, M.S., Shen, G.P.,et al. 2005. Expression of chemokine receptor CXCR4 in naso-pharyngeal carcinoma: pattern of expression and correlationwith clinical outcome. J. Transl. Med. 3: 26[Epub ahead ofprint] doi:. 10.1186/1479–5876–3–26

Watson, P.H., Fraher, L.J., Hendy, G.N., Chung, U.I., Kisiel, M.,Natale, B.V., and Hodsman, A.B. 2000a. Nuclear localizationof type 1 PTH/PTHrP receptor in rat tissues. J. Bone Miner.Res. 15: 1033–1044. PMID: 10841172.

Watson, P.H., Fraher, L.J., Natale, B.V., Kisiel, M., Hendy, G.N.,and Hodsman, A.B. 2000b. Nuclear localization of the type 1parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related peptide recep-tor in MC3T3–E1 cells: association with serum-induced cellproliferation. Bone, 26: 221–225. doi:10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00264-1. PMID: 10709993.

Wells, A., and Marti, U. 2002. Signalling shortcuts: cell-surface re-ceptors in the nucleus? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3: 697–702.doi:10.1038/nrm905. PMID: 12209129.

Wheatley, M., and Hawtin, S.R. 1999. Glycosylation of G-protein-coupled receptors for hormones central to normal reproductivefunctioning: its occurrence and role. Hum. Reprod. Update, 5:356–364. doi:10.1093/humupd/5.4.356. PMID: 10465525.

Wiese, C., Goldberg, M.W., Allen, T.D., and Wilson, K.L. 1997.Nuclear envelope assembly in Xenopus extracts visualized byscanning EM reveals a transport-dependent ’envelope smooth-ing’ event. J. Cell Sci. 110: 1489–1502. PMID: 9224766.

Willard, F.S., and Crouch, M.F. 2000. Nuclear and cytoskeletaltranslocation and localization of heterotrimeric G-proteins. Im-munol. Cell Biol. 78: 387–394. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00927.x. PMID: 10947863.

Yang, H., Lu, D., Vinson, G.P., and Raizada, M.K. 1997. Involve-ment of MAP kinase in angiotensin II-induced phosphorylationand intracellular targeting of neuronal AT1 receptors. J. Neu-rosci. 17: 1660–1669. PMID: 9030625.

Yang, S.H., Sharrocks, A.D., and Whitmarsh, A.J. 2003. Transcrip-tional regulation by the MAP kinase signaling cascades. Gene,320: 3–21. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00816-3. PMID:14597384.

Yoneda, Y., Hieda, M., Nagoshi, E., and Miyamoto, Y. 1999. Nu-cleocytoplasmic protein transport and recycling of Ran. CellStruct. Funct. 24: 425–433. doi:10.1247/csf.24.425. PMID:10698256.

296 Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Vol. 84, 2006

# 2006 NRC Canada

Zhu, T., Gobeil Jr., F., Vasquez-Tello, A., Rihakova, L., Bosso-lasco, M., Bkaily, G., et al. 2006. Intracrine signaling throughlipid mediators and their cognate nuclear G-protein-coupled re-

ceptors: a paradigm based on PGE2, PAF, and LPA1 receptors.Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. This issue.

Gobeil Jr. et al. 297

# 2006 NRC Canada