The legionary fortress of VI Victrix at León (Spain). The new evidence (1995-2005)

Fortress Guahan Reprint

Transcript of Fortress Guahan Reprint

This article was downloaded by: [Frank Quimby]On: 11 February 2012, At: 11:21Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The Journal of Pacific HistoryPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjph20

Fortress Guåhån:Frank Quimby aa Former Guam Desk Officer, US Government and current ResearchAssociate, Micronesian Area Research Center

Available online: 27 Sep 2011

To cite this article: Frank Quimby (2011): Fortress Guåhån:, The Journal of Pacific History, 46:3,357-380

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2011.607606

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 46, No. 3, December 2011

Fortress Guahan:

Chamorro Nationalism, Regional Economic Integration and

US Defence Interests Shape Guam’s Recent History

It is high time that there be granted to the people, respectful, loyal and devoted to the greatAmerican nation, the same rights that have been granted to the different states, territories andpossessions . . . by . . . defining the status of the Chamorro people.

Thomas Calvo AndersonFirst Guam Congress, 19171

Military control of these islands is essential . . .The economic development and administration ofrelatively few native inhabitants should be subordinate to the real purpose for which these islandsare held.

Vice Adm. George D. Murray,Commander, Naval Forces Marianas, 19452

In 1998, Guam leaders paradoxically marked the 100th anniversary of theisland’s relationship with the US. Many praised the benefits of a century ofsocial, economic and political development for the US territory, which has self-government under locally elected leaders, an economy that annually generates aUS$4 billion gross domestic product (GDP) and a standard of living that is theenvy of Islanders across the region. Other local leaders, however, used thecentennial of US annexation to frame their annual appeals to the United Nationsabout Guam’s non-self-governing status, denouncing what they call the island’scolonisation and militarisation and requesting UN assistance for the self-determination struggle of the Chamorro people — the descendants of theindigenous inhabitants who are now outnumbered in their homeland by a settlerpopulation.

This dichotomy reflected the impact of Chamorro nationalism, a force thathas significantly influenced social and political developments on Guam in thepast three decades and made ‘self-determination’ a mantra in the island’srelations with Washington. Under the movement’s banner, a new generation ofChamorro leaders shaped strategies to redefine Guam’s ‘anomalous’ relationshipwith the US. While most of these leaders affirm the value of their US affiliationand citizenship, they also seek greater political autonomy, limits to federalpowers in their homeland and the primacy of the island’s indigenous people,reflecting a dual political identity.

1Cited in Donald R. Shuster, ‘Guam and Its Three Empires’, referenced 12 October 2010, � 2009

GuampediaTM, URL: http://guampedia.com/guam-and-its-three-empires/2 Epigram cited in Mar-Vic Cagurangan, ‘Secret Military Memo’, Marianas Variety News, 19 June 2007,

available online at http://decolonizeguam.blogspot.com/2007/06/secret-military-memo.html

ISSN 0022-3344 print; 1469-9605 online/11/030357–24; Taylor and Francis

� 2011 The Journal of Pacific History Inc.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2011.607606

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

Concurrently, Guam underwent integration into the economies of industrialEast Asia under a mass tourism strategy that brought significant new wealth aswell as the social and economic impacts inherent in globalisation and free marketcapitalism. The island’s other economic engine, US defence spending on its basecomplex, is building toward an historic and controversial expansion thatChamorro rights groups oppose and elected leaders fear will overwhelm Guam’slimited land and aging infrastructure.

The Struggle for Civil and Political Rights

The major expression of Chamorro nationalism in this period — and thedominant theme in federal–territorial relations — was the movement forcommonwealth status. This initiative was both a continuation of indigenousrights struggles from the early 20th century and a reaction to US negotiationswith Guam’s neighbours to end the United Nation’s Trust Territory of thePacific Islands.

Before World War II, Chamorro leaders sought basic civil rights andrepresentative self-government denied them under the autocratic US Navy ruleinstituted after the island was seized from Spain during the Spanish–AmericaWar. The US had acquired Guam (as well as Puerto Rico and the Philippines)during a burst of expansionism aimed at making America an imperial power,without prior consideration of how these distant lands with disparate culturesand traditions would fit into the US federal system and predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. The issue reached the US Supreme Court in 1901, when thejustices ruled by a five to four decision in Downes v Bidwell that the full rightsguaranteed under the US Constitution do not automatically extend to all areasunder American control. The Constitution did not necessarily follow the flag.3

By the narrowest of margins, the court rationalised the acquisition of a newclass of overseas possessions, a decision upheld in subsequent rulings known as theInsular Cases, which enunciated a doctrine based on a convenient distinction. TheUS Constitution applied fully to ‘incorporated’ territories, such as Alaska andHawaii, which were considered part of the US and expected to follow the normalevolution to statehood. However, the Constitution applied only partially to‘unincorporated’ territories, which were, in the words of one justice, ‘appurte-nant thereto as a possession’, but not an integral part of the nation. The USCongress, which has plenary authority for territories under the Constitution,could designate an official status for these acquisitions and extend civil and

3Penelope Bordallo-Hofschneider, A Campaign for Political Rights on the Island of Guam, 1899–1950 (Saipan

2001). Guam’s efforts included petition drives, recommendations to naval governors from appointed and

elected advisory congresses and lobbying visits to Washington, seeking US citizenship and self-government.

Though a few naval governors and a number of US congressmen supported these campaigns, the NavyDepartment maintained self-government conflicted with its interests and authority, often arguing the

indigenous people were not ready for US citizenship or that it would adversely affect them. For a Guam

government perspective, see Hale‘-ta: I Ma Gobetna-na Guam: Governing Guam: before and after the war (Hagatna1994). Contemporary Chamorro views of these early efforts are in Vincente M. Diaz, ‘Political rights on the

island of Guam’, Micronesian Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3:1–2 (2004), 94–100.

358 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

political rights to the indigenous people, including self-governance through‘organic acts’ that establish the structure and functions of local government.

However, the US Congress chose not to designate a status for Guam or extendrights to its indigenous people. During the first half of the 20th century, the islandwas an ‘anomalous state’ in a US polity constitutionally premised on rule byconsent of the governed. Guam’s ‘native inhabitants’ were deemed non-citizen‘nationals’, and their governance was left to the fiat of naval officers whoexercised all executive, legislative and judicial powers on the island. In effect,Guam was an American colony, and the US Navy had virtually absoluteauthority over its indigenous population.4

The early Chamorro rights struggle eventually led to congressional passage ofthe Guam Organic Act of 1950, which provided US citizenship, an abbreviatedBill of Rights and a modest degree of local self-government through an electedlegislature, appointed governor and local court system. The Act also designatedGuam an ‘unincorporated’ territory, making clear that the islanders were notofficially on a track for eventual statehood.

Though the Navy Department had consistently opposed the Chamorros’ pre-war rights campaigns, the Administration of US President Harry S. Truman,motivated by its domestic civil rights agenda and the post-war internationalmovement for decolonisation, included Guam on the United Nations’ list of non-self-governing territories in 1946. That provided official UN scrutiny over USactions on Guam and required Washington to report regularly on the island’ssocial, economic and political advancement. Truman then pushed for organiclegislation after the elected Guam Congress, which had been authorised by thenaval government, staged a 1949 walkout to protest the admiral/governor’sheavy-handed actions and spur a US response to renewed local appeals for self-government. Prompted by news reports of the protest in the Washington Post andNew York Times, which were highly critical of naval rule, Truman also transferredUS supervisory authority over Guam from the Department of the Navy to theDepartment of the Interior and appointed the island’s first civilian governor.5

4The Insular Cases’ impact on US territorial policy is detailed in Arnold H. Leibowitz, Defining Status:

a comprehensive analysis of United States territorial relations (Dordrecht 1989), 17–26. For the US Attorney General’s

description of Guam as an ‘anomalous state’, see ibid., 15, and for a detailed analysis of Guam’s current status,

ibid., 313–400. The views of US anti-imperialists who opposed the acquisition of overseas colonies (but whosepolitical standard-bearers lost the 1900 presidential election) were reflected in the dissenting comments of

Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, who held that the majority opinion in the first of the Insular Cases

rationalised a colonial system not authorised by the US Constitution: ‘The idea that this country may acquire

territories anywhere upon the earth, by conquest or treaty, and hold them as mere colonies or provinces — thepeople inhabiting them to enjoy only such rights as Congress chooses to accord to them — is wholly inconsistent

with the spirit and genius, as well as with the words, of the Constitution.’ See Downes v Bidwell, 182 US 244,

372–3.5 The 1949 walkout is detailed in Anne Perez Hattori, ‘Righting civil wrongs’, Isla: a journal of Micronesian

Studies, 3:1 (1995), 1–27. An account of Guam’s post-war struggle from the perspective of its stateside allies is in

Doloris Coulter Cogan,We Fought the Navy and Won: Guam’s quest for democracy (Honolulu 2008). The US position

on Guam’s post-war self-governing status is described by the island’s first appointed US civilian governor,Carlton Skinner, in his After Three Centuries: representative democracy and civilian government for Guam (San Francisco

1997), 100–1.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 359

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

In 1962, US President John F. Kennedy appointed the first Chamorrogovernor for Guam and lifted the Navy security clearance required for enteringthe island, a measure that had been instituted during the Korean War. Thepeople of Guam also received the rights to elect their governor (in 1968) and anon-voting delegate to the US House of Representatives (in 1972). US officialsmaintain that these post-war actions established meaningful self-government,rectifying the island’s non-self-governing ‘colonial’ status.

In the early 1970s, the Northern Mariana Islands, which the US had wrestedfrom Japan in 1944, administered as part of the UN trusteeship and regarded asstrategically important, began negotiations with Washington for politicalaffiliation. By 1975, the northern islanders, most of whom also are Chamorrosand Guam’s nearest neighbours, had sealed a agreement for US commonwealthwhich was modelled on the status negotiated by Puerto Rico in 1950. TheNorthern Marianas ‘Covenant’ provided a significant degree of autonomy undera locally adopted constitution, requiring ‘mutual consent’ for key self-government provisions to be modified, limiting land ownership to residents ofNorthern Marianas descent, delegating control of immigration, labour and taxlaws to the local government and providing a US$420 million assistance packagefor 14 years.6

The speedy negotiations and innovative agreement shocked and angeredGuam leaders. The voters of Guam had rejected reunification with theunderdeveloped Northern Marianas in 1969, primarily because the northernIslanders, who had been under Japan’s pre-war rule, had assisted the Japanesemilitary in their brutal wartime occupation of Guam. The Chamorros of Guamhad remained steadfastly loyal to ‘Uncle Sam’ during those agonising war years,many suffering starvation, torture and death at the hands of the Japanese, andmost losing their homes and businesses in the US bombardment and recapture ofthe island.

The perception of many Guam leaders was that their loyalty, patriotism andsacrifice counted for little, while those who had aided America’s wartime enemywere rewarded with high-level US attention, comprehensive negotiations and amore honourable status in the American family. This was a major psychologicalblow for Guam’s senior leadership. As Antonio Won Pat, Guam’s delegate to theUS Congress, said at the time, ‘Whatever the needs — real or perceived — of thePentagon in the Western Pacific, the willingness of Washington to deal sogenerously with non-citizens while denying their fellow Americans equaltreatment can only be viewed with suspicion and resentment by the people ofGuam.’7

6The Northern Marianas commonwealth agreement, negotiated from December 1972 to February 1975,

was approved by the Islanders in a 17 June 1975 plebiscite by a 78.8% margin. The agreement became

US Public Law 94-241 (90 Stat. 263), and is codified at 48 USC x 1801 note. An insider’s history of thenegotiations is Howard P. Willens and Deanne C. Siemer, An Honorable Accord: the covenant between the Northern

Mariana Islands and the United States (Honolulu 2002). For background, see these authors’ National Security and Self

Determination, United States Policy in Micronesia: 1961–1972 (Westport, CT and London 2000); also Samuel F.McPheters, Self-Government and Citizenship in the CNMI (Saipan 1997); and Don Farrell, History of the Northern

Mariana Islands (Saipan 1991).

360 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

Won Pat’s generation had seen the island’s military role transformed from asmall naval coaling station into a major US staging base for the war on Japan,with more than 200,000 military personnel and 21 bases occupying an estimated80% of the island’s 212 square miles (550 square kilometres). After the war,about 58% of the island was officially retained (bought or leased) — much ofthat through controversial eminent domain land condemnation proceedings —to convert the bases into Cold War sentinels. These acquisitions displaced morethan 11,000 Chamorros, almost half of the indigenous population — a painfuldenouement to their liberation from wartime trauma. The new installationsincluded a Strategic Air Command base, which supported US forces in theKorean War and hosted B-52 bombers that flew thousands of missions in theVietnam War; a naval base which homeported Polaris nuclear missilesubmarines and nuclear-powered attach submarines in the era of MutuallyAssured Destruction; and a Naval Air Station and top-secret Naval Facilitywhich tracked Soviet naval activity in the Pacific.8

The evolving US military posture on the island had significantly affected theindigenous population, retarding political and economic development beforeWorld War II and causing major land alienation, immigration and environ-mental impacts in the post-war years. US immigration policy was regarded asespecially controversial because many Chamorros believe the federal governmenthas allowed an unnecessarily high number of permanent immigrants into theisland, adversely affecting the social, cultural and political character of theirhomeland. Indigenous rights advocates maintain that this policy violates the UNCharter, which discourages permanent immigration into non-self-governingterritories.

Residents who claim Chamorro ancestry today represent about 37% of theisland’s 180,000 residents, down from 90% in 1950 and 55% in the mid-1970s.The other two-thirds of Guam’s population are immigrants (and theirdescendants) from the Philippines, US states and other Asian and Pacificnations, including a recent wave of more than 35,000 citizens of the FreelyAssociated States (the Federated States of Micronesia, Palau and the MarshallIslands). Filipinos are now the second largest ethnic group on Guam, accountingfor about 26% of the population.9

7Delegate Won Pat’s quote is in Donald R. Shuster, ‘Guam and its three empires’, referenced 12 October

2010, � 2009 GuampediaTM, URL: http://guampedia.com/guam-and-its-three-empires/. For effects of Japan’s

2½-year occupation, see Wakako Higuchi, ‘Impact of Japanese military occupation of Guam’, referenced

19 August 2010, � 2009 GuampediaTM, URL: http://guampedia.com/impact-of-japanese-military-occupation-of-guam/.

8 For impact of post-war land takings, see Hattori, ‘Righting civil wrongs’, 7–9; also Robert F. Rogers,

Destiny’s Landfall: a history of Guam (Honolulu 1995), 214–23.9 For Guam’s demographic breakdown by ethnicity, see Guam Statistical Yearbook 2008 (Hagatna 2009), 295.

For immigration issues, see Leibowitz, Defining Status, 387. A brief history of Chamorro–Filipino relations is in

Vicente M. Diaz, ‘Bye bye Ms. American Pie: the historical relations between Chamorros and Filipinos and the

American dream’, Isla: a journal of Micronesian Studies, 3:1 (1995), 147–60. Freely Associated State residents arepermitted to enter US states and territories under the Compact of Free Association. See Leibowitz, Defining

Status, 643–59.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 361

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

These post-war developments, especially the accelerating change in theisland’s ethnic makeup, led to growing concerns regarding the loss of Chamorroculture and primacy. Diminishing use of the Chamorro language, which hadbeen removed from the public school system and replaced with English underNavy rule, was seen as symptomatic of the loss of indigenous identity. In the late1960s, the local government began mandating Chamorro cultural studies andlanguage programmes in public elementary, secondary and college curriculums.These initiatives reflected linkages in the evolving views of many Chamorrosregarding cultural preservation, indigenous primacy and greater autonomywithin the US polity. The blanket application of US laws to the island was seenas especially problematic because the people of Guam do not have an equal voicewith communities in US states in the formulation and enactment of federal lawsaffecting them. Owing to the island’s unincorporated status, Guam residentshave no representation in the US Senate, only a non-voting delegate in the USHouse of Representatives, and may not vote for President.10

The sense of being ignored by US officials while Northern Marianas residentsreceived first-class treatment spurred the Guam Legislature to institutionalise apolitical status movement by establishing official commissions to study options,issue reports, conduct public education campaigns, recommend plebiscites andengage Washington in negotiations. A 1973 legislative status commission,eschewing independence and statehood as unrealistic, concluded that the mostfeasible option for an improved interim political relationship with the US was thecommonwealth status Puerto Rico enjoyed and which the Northern Marianaswas using as a model. Because US administrations had accepted commonwealthagreements with these two territories, Guam leaders assumed it represented anew transitional status in the US territorial relations hierarchy — aboveunincorporated but below incorporated — which could limit US federal powerand enhance local control of island affairs.

Commonwealth was seen as a solution that allowed continued US sovereigntywhile addressing local autonomy issues, such as the application of US law,military land acquisition policy and preservation of Chamorro culture andprimacy. The commission also invited a UN committee on decolonisation to visitGuam in October 1974 to affirm that the island was non-self-governing and hada right to independence as an ultimate political status. The US government,which maintained that Guam had opted for US affiliation and achieved self-government, blocked the visit.

As the Northern Marianas negotiations concluded, US National SecurityCouncil officials, who appreciated the implications of the new agreement,conducted a classified study that supported a comparable status for Guam. USPresident Gerald R. Ford approved the recommendation, and US Secretary ofState Henry Kissinger instructed an Under Secretaries Committee to ‘seekagreement with Guamanian representatives on a commonwealth arrangement

10 For a synopsis of Guam leaders’ views c. 1973–74 on the need for status improvements, see Andrew Gayle,

An Analysis of Social, Cultural and Historical Factors Bearing on the Political Status of Guam (Agana 1974).

362 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

no less favorable than that which we are negotiating with the NorthernMarianas’. However, US officials responsible for carrying out the directive wereextremely reluctant to engage Guam in substantive negotiations (which mightinclude such ostensibly ‘non-negotiable’ topics as US sovereignty, military basesand foreign affairs). Their reactive, foot-dragging approach attempted to cajoleisland officials to open a ‘dialogue’ on Guam–federal relations with a limitedagenda without actually informing them of the Presidential directive.Disagreement among Guam leaders on status approaches and the strongpreference of Rep. Philip Burton, the powerful chairman of the US HouseSubcommittee on Territorial and Insular Affairs, for a locally-drafted-constitu-tion approach ended consideration of the proactive status negotiation envisionedin the Ford/Kissinger directive.11

Guam’s Commonwealth Strategy

During this period, Chairman Burton, who regarded himself as a protector andbenefactor of the island territories, repeatedly told Guam leaders that he wouldensure that the benefits the Northern Marianas received under its new statuswould eventually be provided to Guam. He urged Guam leaders not to objectformally to the Northern Marianas commonwealth legislation in Congress andinsisted that allowing Guam to draft its own constitution would enable theislanders to gain the status improvements they sought.12

Guam leaders established a new political status commission in 1975 and,persuaded by Burton and Won Pat to support the draft constitution approach,organised a 1976 plebiscite on options. The island, already suffering from highunemployment and inflation, was struck by super-typhoon Pamela in May,which caused widespread damage to homes and public utilities, as well as themilitary base complex, leading to large infusions of federal emergency relief fundsand capital rehabilitation investments. In a September 4 plebiscite, 58% ofvoters chose the status quo ‘with improvements’ over four other options.Statehood was second with 24%.

The following month, as a result of Won Pat’s efforts with Burton to provideGuam another means of expanding local self-government, Congress authorisedisland leaders to draft a constitution and federal relations act ‘within the existingterritorial–federal relationship’. Both documents, which would replace thefederal Organic Act, required US approval. However, Guam voters rejected thedraft constitution in 1979, primarily under the logic of ‘political status first’. The

11The 1973–74 Guam political status commission activities are from Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 250.

The National Security Council study was uncovered by Howard P. Willens and Dirk A. Ballendorf, The Secret

Guam Study: how President Ford’s approval of the commonwealth was blocked by federal officials (Mangilao and Saipan2004), which cites the Kissinger quote from ‘Memorandum, February 1, 1975, Kissinger to Chairman,

Under Secretaries Committee’, on pp. 1 and 67; and includes the entire memorandum as Appendix 1 on p. 143.

The abandonment of the Presidential directive is detailed in pp. 77–115.12Rep. Burton’s promises to Guam are reported in Willens, Honorable Accord, 356, and in Willens and

Ballendorf, The Secret Guam Study, 13–15.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 363

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

spirited convention debates, carried live via television, and extensive publicadvocacy campaigns, culminating in the defeat of the draft constitution,provided a major impetus for the next evolution in the process. Reflectinggrowing public awareness of the UN mandated ‘self-determination’ processsweeping Micronesia and continued concern with the loss of Chamorro cultureand primacy, Guam leaders established a Commission on Self-Determination,under the direction of the Governor, to supplant the previous commissions onpolitical status, which had been under the control of the Guam Legislature. Thechange in terminology and organisation reflected a growing assertivenessregarding the island’s agenda for negotiations.13

The new commission then organised a 1982 plebiscite, resulting in a pluralityvote for commonwealth (49%), which was generically defined along the lines ofthe Puerto Rico and Northern Marianas pacts. Statehood received 26% of thevote; status quo 10%; while free association and independence each received 4%.A runoff chose commonwealth (73%) over statehood (27%) as the preferredstatus.

The 1983 death of Rep. Phil Burton removed a strong advocate for the islandand potential ally in the commonwealth quest. However, a group of UScongressmen, at the urging of Won Pat, advised island leaders in 1984 to developa ‘working draft’ of a bill that addressed their concerns, but to remain willing tocompromise when negotiations on the proposal were joined. Rep. Morris K.Udall, chairman of the House committee with primary jurisdiction over the bill,reiterating the need for flexibility.14

The Commission drafted and refined a proposal, but ultimately decided thatGuam voters should ratify the bill before submitting it to the Congress. The finalversion called for mutual consent on key self-government aspects of a federal–territorial relationship, including the application of federal law to the island;provided the local government authority on immigration, labour law, ExclusiveEconomic Zone rights; prohibited the federal use of eminent domain power toacquire land for military bases; and required the return of excess base lands to thelocal government and consultation with Guam officials before major changes toforce levels or base missions. Guam Governor Joseph F. Ada described theproposed status as ‘a relationship of mutual consent: in which the power of thefederal government unilaterally to change our status, change agreementswe arrive at, and impose unilateral federal law upon us is restricted . . . Onlyby giving us the right of consent can our people truly be empowered.’15

Grassroots groups that had been garnering public support for Chamorrorights for more than a decade through advocacy campaigns on cultural andenvironmental preservation, indigenous land rights and political status, lobbiedfor many of these provisions. More importantly, because Guam remained on theUN list of non-self-governing territories and was ostensibly eligible for an

13Hale‘-ta: Kinalamten Pulitikat: sinenten i Chamorro/Issues in Guam’s Political Development: the Chamorro perspective

(Hagatna 1996); also Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 271–4.14 Ibid., 271–5.15Governor Joseph F. Ada, ‘Time for change’, Isla: a journal of Micronesian Studies, 3:1 (1995), 135.

364 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

internationally monitored self-determination process, indigenous rights advocateshad urged the commission early in its deliberations to address that issue,introducing a new and potentially governing dynamic.16

Citing UN decolonisation principles and international treaties, the commis-sion determined that the ‘self’ in self-determination could only be the indigenousresidents and their descendants, since post-World War II settlers had by birth ornaturalisation already chosen their national affiliation. The residual sovereigntyof the Chamorro people was asserted in commonwealth bill provisions thatprovided for special cultural preservation and land trust programmes and theexclusive right to determine the island’s ultimate political status in a future act ofself-determination. The Chamorro ‘self’ was further defined as people born onGuam as of 1 August 1950 (the effective date of the Guam Organic Act) andtheir descendants. All qualified voters could vote on the draft commonwealthbill, however, because it was deemed an ‘interim’ or ‘transitional’ status. Guamvoters approved most of the bill in an August 1987 referendum. Immigration andself-determination provisions that had failed to receive a majority were revisedand narrowly approved in a second vote.17

The bill had been largely drafted under the administration of GovernorRicardo J. Bordallo (1983–86) and became the keystone of the territory’s federalrelations platform under him and later under Governors Joseph F. Ada (1987–94) and Carl Gutierrez (1994–2003). Beginning in the spring of 1988, thelegislation was introduced in several consecutive sessions of the US Congressduring the tenures of Guam Delegates Ben Blaz (1985–93) and RobertUnderwood (1993–2003) and received two hearings (1989 and 1997) by theUS House Interior Subcommittee on Territorial and Insular Affairs. Among itsstrategies, the Ada Administration hoped that emphasising the island’s ‘colonialstatus’ under an ostensibly ‘anti-colonial’ nation would encourage US officialsto offer concessions. The Gutierrez efforts included a demonstration of partyloyalty, with more than US$1 million in contributions to the re-electioncampaign of US President William J. Clinton.18

However, the administrations of US Presidents George H.W. Bush (1989–93)and Clinton (1993–2001) opposed major provisions of the bill, focusing theirobjections on issues of sovereignty, constitutionality and policy continuity, andarguing that the proposal sought a composite status that included incompatible

16Robert A. Underwood, ‘Guam’s political status’, referenced 12 October 2010, � 2009 GuampediaTM,

URL: http://guampedia.com/guams-political-status/.17Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 271–4; and Hale‘ta-Kinalamten Pulitikat (1996).18 The text of the Guam Commonwealth Act is available online at the Library of Congress site: http://

ecip.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c105:H.R.100. Guam’s official position on the bill was enunciated in numerous

testimonies, including ‘An overview of Guam’s Commonwealth quest presented by Joseph F. Ada . . . to the

House Interior Subcommittee on Insular and International Affairs’, Honolulu, Hawaii, 11 December 1989

(Hagatna 1989), and ‘Statement on Commonwealth before Congress by the Honorable Carl T.C. Gutierrez.Oct. 29, 1997 available online at http://calrepublic.tripod.com/guam.html. A comprehensive statement of the

Chamorro position on political status is Laura Souder, Paul Jaffrey and Robert Underwood (eds), Chamorro

Self-Determination (Agana 1987). For Ada administration’s colonial focus, see Leland Bettis, ‘Political reviews:Guam’, The Contemporary Pacific, 6:1 (1994), 173; and Stewart Firth, ‘Decolonization’, in Robert Borofsky (ed.),

Remembrance of Pacific Pasts (Honolulu 2000), 330.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 365

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

aspects of independence, free association, commonwealth and statehood. The billwould authorise the exclusion of US citizens (the settler population), based onethnicity, from a vote on ultimate status, which US officials maintainedconflicted with constitutional protections against non-discriminatory voting.Other provisions, they argued, ran counter to strategic defence interests andterritorial policy. In an ‘all or nothing’ strategy, Ada publicly maintained that hewas bound by the bill’s language and unable to negotiate changes. The measurewas never reported out of committee.

Guam officials involved in the commonwealth quest generally attribute itsfailure to the US refusal to recognize the Chamorro people’s non-self-governingstatus and exclusive right to self-determination and the fear that greater localautonomy would restrict and jeopardize the US defense posture and militaryflexibility in the region. Robert F. Rogers, a Guam historian and former politicalstatus advisor to Gov. Ricardo J. Bordallo, agrees that US ‘obduracy’ played animportant part, especially regarding Washington’s geopolitical use of the islandor allowing local leaders to participate in determining US national securitypolicy for the region. However, Rogers attributes most of the failure to what hecalls the adversarial posture, inflexible position and poor strategy of Guamleaders, who forfeited an opportunity to craft a compromise bill with aDemocratically-controlled Congress, relegating negotiations to US ExecutiveBranch officials who habitually defend the status quo. Guam’s approach wassubstantially shaped, Rogers asserts, by political pressure from Chamorro rightsgroups.19

Frustrated by federal rejection, the Guam Legislature established aCommission on Decolonization for the Implementation and Exercise ofChamorro Self-Determination and instituted a companion Chamorro Registry.The 1997 law called for a plebiscite, with or without US congressionalauthorisation, so that ‘native inhabitants’ could express a preference forindependence, free association or statehood. The commission was oftenunfunded, the vote remains unscheduled and the registry is incomplete.20

East Asian Economic Integration

Guam’s commonwealth quest coincided with the greatest period of economicexpansion in the island’s history, powered primarily by Japanese investment andtourism development. After Kennedy removed the Navy’s security clearancerequirement for foreign visitors, the industry began slowly in the late 1960s, wasdrawing half a million visitors a year by 1988 and a million annually by 1995.Plant investment spawned a construction boom, with more than 40 hotels,

19Robert F. Rogers, ‘Requiem for a quest: the failure of Guam’s leaders to secure fundamental politicalchanges,’ in Donald R. Shuster, Peter Larmour and Karin Von Strokirch (eds), Leadership in the Pacific Islands:

Tradition and the Future (Cambridge and Guam 1998), 89–99.20 The Guam Legislature’s ‘Act to Create the Commission on Decolonization . . . is Public Law 23-147;

the Chamorro Registry is Public Law 23-130, 30 September 1997. Both laws are available online at

www.guamlegislature.com/23rd_public_laws.htm.

366 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

including many high-rise units from international chains, sprouting up over threedecades, mostly in the Tamuning–Tumon Bay area along the island’spicturesque northwest coast. At its peak, the sector offered 9,000 rooms andemployed more than 20,000 island workers.

Currently, about 1.4 million visitors arrive each year, generating aboutUS$1.34 billion in annual tourism spending. Japanese visitors account for almost80% of arrivals, and South Korea is the second largest and fastest growing sector— about 10%. Other promising markets include Taiwan, Hong Kong, Russiaand the People’s Republic of China, now the world’s second largest economywith an expanding middle class. Guam leaders are asking US officials to establisha China–Russia Guam Visa Waiver Program that could accelerate tourism fromthese major new markets to diversify the island’s visitor base and wean the localeconomy from its heavy dependence on Japanese visitors.21

Guam officials estimate that the tourism sector accounts for about 20% of theisland’s GDP, currently US$4.3 billion; 35% of the island’s jobs and 25% of thelocal government’s revenue. Guam’s GDP increased 75% from 1988 to 1992 andlocal government revenues rose to an average of US$575 million a year in the1990s, peaking at US$679 million in 1995. This unprecedented growth reversedthe core revenue-generating components of Guam’s economy, which in the 1960swas based 75% on US federal and military spending, 20% on tourism and 5%on other activities. By 2003, tourism generated about 60% of the island’srevenue, while US federal and military spending accounted for about 30%, withother activity generating 10%. This remarkable turnaround led a Bank ofHawaii economist to quip, ‘In economic and financial terms, Guam seemed morelike a part of Japan than a territory of the United States.’22

Most local leaders enthusiastically welcomed this expansion, which generateda sense of economic and political empowerment after decades of dependence onUS assistance and defence spending. The growth also underscored the island’ssignificant economic development potential which US defence officials haddownplayed for half a century. As Lt Governor Frank Blas told a 1991conference, ‘Our economic prosperity has made it possible for us to consider

21Tourism revenue statistics from the Guam Economic Development Authority, available online at http://

www.investguam.com, and Guam Statistical Yearbook 2008, 347–50; also John C. Salas, ‘Evolution of the tourism

industry on Guam’, referenced 12 October 2010, � 2009 GuampediaTM, URL: http://guampedia.com/evolution-of-the-tourism-industry-on-guam-2.

22 The value of tourism to Guam’s economy is from the Guam Economic Development Authority statistical

summary available online at http://www.investguam.com, as well as ICF International, Draft North and Central

Guam Land Use Plan Prepared for the Government of Guam (Seattle 2009), 4–2, available online at http://www.investguam.com/pdf/2009/draft-land-use-plan-012209.pdf. Tourism jobs as 35% of the labour force is in

Leroy O. Laney, Economic Forecast — Guam Edition (Honolulu 2007), 3. For economic downturn, see A Report on

the State of the Islands ([Washington] 1999), 36–43, available online at http://www.doi.gov/oia/StateIsland/

islands.pdf. For island GDP, see Bureau of Economic Analysis Releases Estimates of Gross Domestic Product for Guam,

American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands . . . (Washington 2010), available online at http://

www.bea.gov/newsreleases/general/2010/territory_0310.htm. Local revenues, labour force and visitor totals are

from Guam Statistical Yearbook 2008, 143, 225 and 347, respectively. Quote from Wali M. Osman, Guam Economic

Report 2003 (Honolulu 2003), 5, available online at http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs//

OsmanGuamEconomicReport2003.pdf.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 367

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

realistically changing our political status into one more equitable and fair to thepeople of Guam . . . [W]e no longer have the previous dependence on the federalgovernment that constrained us in the past.’23

This euphoria was tempered by the realisation that the capital investment inland, hotel and service sector construction drove island real-estate prices beyondthe means of many local residents. By some estimates, the median price of asingle-family home on the island had more than doubled by 2003. Tourisminvestment also increased alienation of land because there are no ethnic ornationality restrictions on private land ownership on Guam. Hotel constructionand road, power and water utility extensions also posed environmental andinfrastructure challenges which adversely affected the island’s overall quality oflife.24

Moreover, regional economic contractions, exacerbated by natural disasterssuch as a major earthquake in 1993 and super-typhoons in 1997 and 2002, posedsignificant financial problems for the local government. A major driver of tourisminvestment in the 1980s was Japan’s speculative asset price bubble which burst inthe early 1990s, causing Guam’s economy to suffer a downturn in 1993–94. Aftersome recovery in 1995–96, the economy again suffered a setback in 1997, and theAsian financial crisis of 1997–98 further slowed arrivals. Similar, though smaller,impacts were felt in the wake of the 2001 Al Qaeda attacks, Iraq War and SARSepidemic. From 1996 through 2002, tourist traffic fell 22% overall and hoteloccupancy rates dropped 38%. Japanese tourists who visited spent less, from anestimated US$864 million in 1996 to US$452 million in 2001.25

Following the end of the Cold War, annual US defence outlays on Guamdeclined for most of the 1990s, dropping from about US$507 million early in thedecade to about US$461 million by its close. Defence spending is a majorcomponent of overall US government expenditures on Guam, which includeshealth, education, welfare and general operations grants to the local governmentand the transfer of income taxes paid by US military and federal civilianemployees on the island. The US government also makes direct payments toindividuals, including federal civilian employees and retired US servicemen andwomen, including thousands of local residents. Total federal spending on Guam,including defence, averaged US$870 million a year from 1995 through 2001.26

The double dip in defence and tourism led to several years of economicrecession, beginning in 2000, which saw business bankruptcies, bank foreclosuresand double digit unemployment. This retriggered a ‘brain drain’ of educatedworkers with marketable skills, primarily Chamorros, who left for Hawaii andthe US mainland to find work or better paying jobs. Though the exodus between1996 and 2004 was much smaller than what occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, it

23 Blas quote from Judith Paulette Guthertz and Katherine L. Singh (eds), Public Policy, Island Development

and the Chamorro People (Hagatna 1991), 338.24 For housing costs increase, see ICF International, Guam Land Use Plan, 3–4 and 4–3.25Osman, Guam Economic Report 2003, 4–18, and A Report on the State of the Islands, 36–43.26Guam Statistical Yearbook 2008, 132.

368 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

contributed to an ongoing migration of indigenous residents to Hawaii and USmainland states, where by some estimates, there are now 60,000 to 70,000Chamorros — nearly equal to the number on Guam. Many of these migrants arecurrent and retired members of the US armed services. Guam has a higher percapita enlistment rate than many stateside communities of comparable size.27

Because of the need to maintain essential public services and local leaders’reluctance to layoff workers while continuing to maintain a generous publicemployee compensation and retirement system, the government’s budget isdominated by personnel expenditures and other relatively fixed costs — expensesthat remained stable as revenues fluctuated. From the late 1990s through the firstdecade of the 21st century, this imbalance led to annual budgetary shortfalls andaccumulated deficits; by 2006, Guam had a US$524 million general fund deficit.Some local tax revenues also were lost due to the tax cuts under US PresidentGeorge W. Bush, because Guam’s income tax system ‘mirrors’ the federal systemand can be modified only through US congressional legislation.28

In response to declining revenue streams, the local government was forced todelay payments to commercial suppliers and income tax returns due to residents;and to assume extraordinary obligations, including borrowing in the bondmarket and from its public employee retirement fund to meet governmentpayrolls and fulfil other financial obligations. These developments led toacrimonious debate and infighting among local leaders concerning how toaddress the government’s deteriorating financial situation. Inadequate funding ofsome essential services and insufficient capital maintenance and improvementscontributed to court decisions that placed several local agencies in receivershipand hired independent entities to carry out some of their functions.29

By 2004, Guam’s economy began to turn around, as spending in both mainengines of growth gradually increased. The Japanese economy had begun a slowrebound, though it remained problematic for most of the decade; internationalair travel security improved; and US defence spending began to rise, as agingbase facilities damaged by typhoons were refurbished. Total federal expenditureson Guam, which had averaged less than US$900 million annually throughoutthe 1990s, rose steadily from 2001 through 2008, when they reached US$1.5billion. From 2002 to 2007, Guam’s GDP, adjusted for inflation, grew at anaverage annual rate of 1.8%, increasing from about US$3.6 to US$4.3 billion.30

27 See Laney, Economic Forecast, 1–12. Unemployment numbers from Osman, Guam Economic Report, 9–10,

and Guam Statistical Yearbook 2008, 225–7; and ibid., 47, for Chamorro population in US.28Guam’s Tax Collection Activities, Report Hi-EV-GUA-0002-2008 (Washington 2008), 3, available online at

http://www.doioig.gov/images/stories/reports/pdf/HI-EV-GUA-0002-2008.pdf.29Osman, Guam Economic Report, 4–18, and Report on the State of the Islands, 36–43.30Wali M. Osman, An Update on the Economy of Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

(Washington 2004), 1–3, available online at http://www.doi.gov/oia/Osman/Osmanreports/An%20Update%20on%20the%20Guam%20and%20CNMI%20Economies.pdf. Also Guam Statistical Yearbook 2008,

132–5. For GDP rise, see Bureau of Economic Analysis Releases Estimates of Gross Domestic Product for Guam.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 369

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

Regional Security Integration

In 2006, US and Japanese officials, without consulting Chamorro leaders, agreedto relocate substantial American forces from Okinawa to Guam in conjunctionwith other realignments, requiring a significant expansion of the island’s militarybases over the next decade. The main elements of the proposed build-up wouldtransfer about 8,000 members of the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force and 9,000of their dependents; and about 650 Army Missile Defense Task Force personnel(and their 900 family members) to establish a Patriot anti-ballistic missilebattery. The expansion would also develop facilities at Naval Base Guam toaccommodate additional nuclear-powered submarines and a nuclear-poweredaircraft carrier, which typically carries about 5,000 sailors and airmen. With theimported workers needed for the upgrade and expansion, the expected influxover the course of the build-up could be as high as 79,000 people — a 40%increase on an island with a population density of 840 per square mile (2,175.6per square kilometre).31

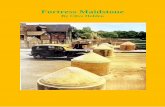

There are currently about 15,000 US military personnel and family memberson Guam. The naval base has three nuclear-powered attack submarines, a tenderand two dozen other units that support US fleet operations. The base, which alsohosts US Coast Guard vessels, is located at the southern reach of Apra Harbor,while the northern arm contains Guam’s commercial seaport, which handlesabout 2 million tons of cargo a year (see Figure 1). Anderson Air Force Base, atthe island’s northern tip, is home to rotating deployments of B-1, B-2 and B-52bombers, KC-135 refuelling tankers and squadrons of F-16 and F-22 fighters.Anderson also hosts Global Hawk unmanned surveillance aircraft. With its hugefuel storage facilities and dual runways, Andersen is a key logistics support centrefor contingency forces deploying to East and Southeast Asia and the IndianOcean (see Figure 2). Both the Air Force and Navy maintain extensiveconventional weapons storage facilities on Guam as well as the capacity to storenuclear weapons. A Naval Computer and Telecommunications Station, whichprovides global and universal communications services to fleet units, shoreactivities and joint forces, is the third largest defence installation on the island.32

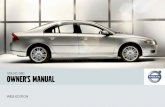

The base complex has served as a hub for joint air–sea military exercises,including operations with Australian, Japanese and South Korean defence forces(see Figure 3). The planned realignment would expand this role, enabling thebases to function as a centre for intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance andstrike operations — a composite capability to support US and allied forces in theAsia-Pacific region. Defence officials believe the expansion will return the

31Final Environmental Impact Statement: Guam and Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands relocation (Pearl

Harbor 2010), ES-1 to ES-10, available online at http://www.guambuildupeis.us/. More on relocation is at the

Joint Guam Program Office website, http://www.jgpo.navy.mil.32 For current naval base missions, see http://www.cnic.navy.mil/Guam. For Anderson, see http://

www.andersen.af.mil/.

370 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

complex to prominence in the US defence posture, making it one of the mostimportant overseas US bases in the world.33

The US Government Accountability Office estimates that the total Guambuild-up will exceed US$17.4 billion in costs. Japan has agreed to provide

FIGURE 1: The USS Kitty Hawk, CV 63, is manoeuvred into a berth in the inner harbour of the

Naval Base Guam, which shares Apra Harbor with the Guam commercial port. (US Navy photoby Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Stephen Rowe)

FIGURE 2: F-15E Strike Eagles and the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber over Andersen Air Force Base,

Guam. (US Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Cecilio Ricardo)

33Richard R. Burgess, ‘Guam’s return to prominence’, Sea Power (Military.com: 25 January 2007),

available online at http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,123418,00.html.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 371

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

US$6.9 billion for the project, including US$2.8 billion in direct cashcontributions, has already contributed about US$834 million, and anotherUS$420 million was approved on 29 March in Japan’s budget. As the largestproposedmilitary build-up onGuam since the end ofWorldWar II, the expansionis expected to generate unprecedented economic growth, exceeding the tourismboom of the 1980s and 1990s, according to financial analysts. The relocations,construction and support services could generate US$2.1 billion in gross receiptsand corporate and personal income taxes for Guam between 2010 and 2020, thePentagon estimates. Some local officials believe that Guam will see betweenUS$400 million and US$1 billion in military construction annually for six to 10years. In addition to temporary construction jobs, the development is expected tocreate permanent civilian jobs with themilitary, its contractors and related privatesector suppliers. By one estimate, support services for the new facilities couldgenerate 6,000 additional permanent civilian jobs on island.34

While the 11 March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster in Japanraised concerns about the viability of the costly realignment project, US

FIGURE 3: A US Air Force B-52 leads a formation of Air Force and Navy F-16, F-15 and F-18

aircraft over the USS Kitty Hawk (CV 63), USS Nimitz and USS John C. Stennis Strike Groups

during Valiant Shield, the largest joint exercise in the Pacific in 2007. Held in the Guam operating

area, the exercise included 30 ships, more than 280 aircraft and more than 20,000 service membersfrom the Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard. (US Navy photograph by Mass

Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jarod Hodge)

34 Ibid.; and Final Environmental Impact Statement. ES-1 to ES-10. For job estimates, see Defense Infrastructure:

DOD needs to provide updated labor requirements . . .GAO-10-72 (Washington 2009). According to one economicanalyst, the base expansion ‘will constitute the largest military build-up on Guam since the end of World War

II, and it promises to boost Guam growth beyond anything it has experienced in modern times, potentially well

exceeding the tourism investment boom.’ See Laney, Economic Forecast, 8. Japan’s contributions to the projectare detailed in ‘Scrap bill to ratify Guam treaty’, Japan Press Weekly, 3 April 2009, available online at http://

www.japan-press.co.jp/2009/2617/usf_2.html.

372 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, JapaneseForeign Minister Takeaki Matsumoto and Japanese Defense Minister ToshimiKitazawa officially reconfirmed their commitment at a 21 June meeting of theirjoint Security Consultative Committee. They acknowledged, however, that thetarget dates would have to be changed because relocation of the Marines couldnot be accomplished until a new Marine air station on Okinawa’s northeasterncoast is completed in 2014. They estimated that the relocation to Guam would becompleted as soon as practicable after that date.35

While several polls on Guam indicate widespread public support for the build-up, including a majority of Chamorros according to one survey, critics say thepolls are misleading because they do not ask respondents to weight the potentialsocial and environmental impacts. Moreover, many local leaders expressedconcerns that the expansion will overwhelm the islands’ road and utility systems.Indigenous rights leaders oppose what they regard as further militarisation of theisland through ‘national security imperialism’. As LisaLinda Natividad, aUniversity of Guam assistant professor, told the Washington Post, ‘This is old-school colonialism all over again. It boils down to our political status — we areoccupied territory.’36

Guam leaders have limited lobbying power because of their territorial statusand no legal means of halting the build-up. The local government’s major publicconcern is that timely and adequate US funding will not be provided to upgradethe island’s commercial port, water and sewer systems, power grid, hospital,highways and social services. Local officials estimate it will cost more than US$3billion to improve these facilities to support the build-up and expectedpopulation increase and have urged US officials to slow the deployment ofMarines until sufficient federal development assistance arrives. ‘We don’t mindbeing the tip of spear, but we don’t want to get the shaft’, said Simon A. SanchezII, chairman of Guam’s commission on public utilities. ‘We have been asking forhelp from Day One.’37

The potential environmental impacts of the expansion have also raisedobjections from local leaders and community groups, especially the proposeddredging of coral reefs at the naval base to accommodate the berthing of anaircraft carrier and the siting of a proposed Marine Corps firing range complexon Guam’s northeast coast. The Guam Historic Preservation Office, Guam

35 For the 21 June 2011 recommitment of US and Japanese leaders to the Marine relocation from Okinawa

to Guam, see the US Department of State websites http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/06/166597.htm and

http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/06/166600.htm.36The Pacific Daily News, a US Gannett Company, Inc.-owned daily newspaper published in Guam, found

61% of Guamanians, including 56% of Chamorros, believed the military expansion was ‘a good thing’. The

Guam Chamber of Commerce 2008 survey found that 71% of residents supported an increase in the US

military presence, nearly 80% believing the build-up would generate additional jobs and tax revenue; and 60%

believing the additional Marines would be a positive development and improve the quality of life. A 2010University of Guam survey reported similar results. See http://www.guampdn.com, 18 February 2008. The

‘old-school colonialism’ quote is from ‘On Guam, planned Marine base raises anger, infrastructure concerns’,

Washington Post, 22 March 2010, available online at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/story/2010/03/21/ST2010032102932.html.

37 Ibid.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 373

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

Preservation Trust and National Preservation Trust have jointly filed a lawsuit toblock the proposed firing range. Noting the presence of an ancient Chamorrovillage site and other cultural resources in the area, the suit alleges that the Navyfailed to adequately consider alternative locations that would have less impact onthe environment and historic resources; and did not adequately examinethe environmental consequences of its actions, as required by the US NationalEnvironmental Policy Act.

Moreover, local planners point out that most defence construction, includingbarracks and family housing for the Marines (as well as the live-fire trainingrange) will be concentrated in the northern half of the island, which is dominatedby a coralline limestone plateau, gently sloping from the island’s waist to about600 feet (182.8 metres) above sea level along the northern coast. In addition tonumerous military installations, this area already hosts 60% of the island’spopulation and Guam’s major fresh water aquifer. Underlying this concern is thepalpable fear that US officials will require additional land for the build-up andmay resort to eminent domain powers to acquire that acreage.38

The US federal government currently retains about 32% of the island’s land,29% of that for bases, and maintains its option to acquire more acreage as part ofthe expansion, including an estimated 1,100 acres for the live-fire training range.Ostensibly, the military would acquire this by leasing acreage from the localgovernment and private owners. In 2010, Guam’s then Governor Felix P.Camacho and Delegate to Congress Madeleine Z. Bordallo urged defenceofficials to limit the build-up to the current military footprint and not use theireminent domain powers. US Senator Jim Webb, a key congressional leader onforeign and defence policy, supports this limitation. ‘If additional lands must beacquired out of a national security interest’, Webb has said, ‘theU.S. government out of respect for the people of Guam should seek privatearrangements for use of the land and not exercise its right of eminent domain’.39

38 LisaLinda Natividad and Gwyn Kirk, ‘Fortress Guam resists US military buildup’, Asia Times Online,

14 May 2010, available online at http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Japan/LE14Dh01.html; also see EPA Comments

on Draft Environmental Impact Statement (San Francisco 2010), available online at http://www.epa.gov/region9/

nepa/letters/Guam-CNMI-Military-Reloc-DEIS.pdf. The US military’s historic ecological impacts on Guam

inform current environmental concerns regarding the base expansion. The Brown Tree Snake (Boiga irregularis)

infestation is one of the most widely recognised post-war effects, for example. The species was introduced fromMelanesia on a military cargo vessel during World War II, and because it has no natural predators on Guam

and was initially misidentified as the ‘helpful’ Philippine rat snake, the invasive reptile multiplied rapidly,

devastating the island’s native bird species and causing significant damage to the island’s power grid by shorting

out transmission lines.39Dionesis Tamondong, ‘Military buildup is a national issue’, Pacific Daily News, 20 February 2010. Full

text of Webb’s remarks is available online at http://www.webbforsenate.com/news?id=0044. Webb served as

an Assistant Secretary of Defense and Secretary of the Navy under US President Ronald Reagan. Currently

a member of the US Senate Committee on Armed Services and the East Asia and Pacific Affairs Subcommitteeof the Foreign Relations Committee, Webb is regarded as a friend of Guam who is familiar with the issue of

eminent domain land-taking on the island, which he discussed in Micronesia and US Pacific Strategy: a blueprint for

the 1980s (New York 1974). See also, ‘Delegate Bordallo opposes use of eminent domain By DoD for landacquisition’, 12 January 2010, available online at http://www.house.gov/list/press/gu00_bordallo/

opposed.html.

374 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

As the most contentious subject in federal–territorial relations since WorldWar II, federal land-taking by eminent domain power ‘is the only issue in Guamwhich radicalizes even the most mild mannered Chamorro’, one local leader andindigenous rights advocate asserts. ‘[It] is the singular issue with the federalgovernment that can turn the loyal military retiree, the police officer, the teacherand the nurse into Chamorro activists.’40 For Guam’s indigenous people, landwas a historic source of livelihood through subsistence activities, and continues tobe a chief source of indigenous identity, family security and wealth and a primarygauge of local status and authority.

At the outset of American rule, the US government controlled only limitedamounts of island land, mostly surrendered Spanish crown lands and port areasthat had not been in Chamorro ownership for centuries. By the outbreak ofWorld War II, however, the US Navy had increased its holdings to nearly one-third of the island, though defence needs for land had decreased in the previoustwo decades owing to decisions not to fortify Guam. While local leadersappreciate that US national security interests drive Washington’s policy, manybelieve that the eminent domain powers that took huge swathes of private landfor the post-war bases were used arbitrarily, without appropriate restraint.Moreover, much of the acquired land was designated for contingency, remainingunused for decades and unavailable for local farmers, ranchers and developers.In addition, valuable beaches were taken for the exclusive recreational use ofmilitary dependents, removing Chamorro families who had lived there forgenerations and placing communal fishing areas off-limits.41

US federal court cases confirmed landowners’ complaints that just compensa-tion was not made in many of these land takings; and more than US$40 millionhas since been paid to land claimants in restitution. In response to repeatedappeals by local leaders and the efforts of Guam’s Delegate to Congress RobertUnderwood, the US government also transferred about 9,000 acres of excessmilitary land to the local government in the 1990s, including parcels adjoiningthe international airport that had hosted the Naval Air Station. Under the 1994federal Guam Excess Lands Act, sponsored by Underwood, more than two dozenadditional properties have been transferred to the local government, whichdecides how that land will be used, either for public purposes or returned to theoriginal land owners. These transfers enabled the local government to presentseveral Chamorro families with the deeds to their ancestral lands in 2002, the firstof more than a dozen claimants under the local Ancestral Lands Commissioninitiative.42

40Quote from Robert Underwood in ‘Afterword’ of Bordallo-Hofschneider, Campaign for Political Rights on

the Island of Guam, 211.41Hattori, ‘Righting civil wrongs’, 1–27; Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 158.42 Anne Perez Hattori, ‘Guam’, The Contemporary Pacific, 15:1 (2003), 150–62. The 1994 Guam Excess Lands

Act, US Public Law 103-339, mandates that control of federally returned lands be transferred to the

Government of Guam, which determines the future of these lands. Guam enacted legislation in 2000

establishing that excess military lands would be placed in the inventory of the Ancestral Lands Commission,which is responsible for helping original landowners and their heirs reclaim lands they lost in the US post-World

War II land condemnations.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 375

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

A parade of US officials has visited Guam since the build-up was announcedto reassure local leaders that the US government understands their concerns andis adjusting planning to address the issues. The list includes Secretary of DefenseRobert Gates, Chair of the White House Council on Environmental QualityNancy Sutley and Deputy Secretary of Defense William Lynn, the senior USofficial directly overseeing the build-up. Lynn assured Guam leaders in 2010 thatthe US government has made a binding US$100 million commitment to upgradethe island’s commercial port, which will need to handle hundreds of millions oftons of construction material and related cargo for the expansion. He also saidJapan has agreed to provide US$740 million for local infrastructure projects. USdefence officials are working with Guam leaders and local agencies, Lynn noted,to plan improvements for Guam roads, utilities, schools, health care and publicsafety.43

‘The Department of Defense is committed to respecting and preserving theChamorro culture and the spirit of the Guam community’, Lynn told aconference of senators, mayors, education officials and private sector representa-tives. ‘We will not exceed the capacity of Guam’s infrastructure as we constructthe new military facilities. The Environmental Impact Statement makes clearthat we have many ways of controlling the pace of this endeavor.’ His pledgescame a few days after 250 local protesters demonstrated against the MarineCorps training range.44

Without specifically mentioning China, its naval build-up or recent claims ofsovereignty over much of the South China Sea and East China Sea, Lynn toldUniversity of Guam students that the rise of Asia economically and militarily isthe most significant change in the US strategic environment. ‘Five ofWashington’s seven international defense pacts are with East and SoutheastAsian nations and Guam bases would now play a larger role in supporting thosealliances’, Lynn said. ‘From bases here, our forces can ensure the security of ourallies, quickly respond to disasters and humanitarian needs, safeguard the sealanes that are so vital to the world economy, and address any militaryprovocation that may occur.’45

Dual Identities and Decolonisation

Though public interest and support for self-determination and political statusnegotiations waned in the first decade of the 21st century as local leaders focusedfederal–territorial relations on gaining incremental improvements in US

43The full text of Deputy Defense Secretary’s Lynn’s 27 July 2010 remarks to University of Guam are

available online at http://www.defense.gov/speeches/speech.aspx?speechid=1493.44 Ibid.45 Ibid. US international defence agreements in the Asia-Pacific region include the bilateral treaties with

Japan, South Korea and the Philippines; the Manila Pact which includes Thailand; and the ANZUS Treaty,

now suspended between the US and New Zealand but still maintained as a bilateral defence alliance with

Australia. US ships, aircraft and forces in Hawai‘i and Guam directly serve those defence agreements. SeeStewart Firth, ‘Sovereignty and independence in the contemporary Pacific’, The Contemporary Pacific, 1:1–2

(1989), 84–5.

376 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

domestic programmes, Chamorro nationalism continues to influence the island’sdevelopment.

Former Governor Felix Perez Camacho (2002–10), current Governor EddieBasa Calvo and Delegate Bordallo support Chamorro self-determination.Bordallo has won legislation to authorise federal funding for political statuseducation programmes to inform Guam voters of their political options. ‘Ourpeople must be afforded the ability to exercise their right to self-determinationand express their desire for a permanent status’, Bordallo said.46

In what could be interpreted as a symbolic act of indigenous repossession,Governor Camacho directed all local government agencies in February 2010 tobegin using Guahan, instead of Guam, as the island’s name. He also requestedthe legislature to designate the island officially as Guahan. Camacho said theword, which means ‘a place that has’ or ‘we have’ in the Chamorro language(referring to the island’s abundant natural resources), instils indigenousownership and helps to preserve and promote Chamorro culture and history,which he called a paramount priority. The first US naval governor adopted thename Guam, which appears in historical records in addition to Guahan, in theearly 1900s, and it became the island’s official name under American rule.47

The reversion to Chamorro nomenclature has been part of the indigenousrights cultural renewal and preservation movement since the late 1960s.Chamorro has been established as an official language of the island, alongwith English, and indigenous names have been designated for government officesand activities as well as island locales, landmarks and communities. Hagatna, forexample, has replaced Agana, as the official name of the island’s capital.

A number of Chamorro rights leaders have won elective office as a result oftheir self-determination and decolonisation advocacy. Among the best known isRobert Underwood, a chief architect of the indigenous rights movement, whowas elected to five consecutive terms as Guam’s Delegate to the US Congress andwas narrowly defeated in two gubernatorial campaigns in the last decade. Hiselectoral support is especially strong among the younger generation on Guam,where the median age is 27. Underwood, currently president of the University ofGuam, believes ‘the desire for political fulfillment will always be a feature ofGuam’s ongoing relationship with the US. At times, this desire will appeardormant and then it will spring to life as it did in the 1930s and 1940s and againin the 1970s and 1980s.’48

But the issues remain difficult and controversial, Underwood notes: ‘Shouldthere be a formal mechanism such as a plebiscite to consult the will of the

46Congresswoman Madeleine Z. Bordallo’s 19 May 2010 testimony in support of H.R. 3940, at an oversight

hearing of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, available online at http://www.house.gov/list/press/gu00_bordallo/politicalstatus.html.

47 The Honorable Felix P. Camacho, Finishing Strong, State of the Island Address (Hagatna 2010), 9,

available online at http://guamgovernor.net/SOTI_2010.pdf.48Robert A. Underwood, ‘Guam’s political status’, referenced 12 October 2010, � 2009 GuampediaTM,

URL: http://guampedia.com/guams-political-status/.

FORTRESS GUAHAN 377

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

Chamorro people? As the Chamorro population of Guam dwindles to less than 50percent, the issue seems more urgent than ever. Does Guam have the right toindependence and self-determination, as the United Nations claims all small nonself-governing territories do? Is this right rejected by federal authorities? What willget federal attention in the near future?’49

Current Governor Calvo calls Chamorro self-determination a priority for hisadministration. He has funded the Commission on Decolonization, called for a‘diligent and aggressive’ campaign to increase the number of indigenous peopleon the Guam Decolonization Registry (previously known as the ChamorroRegistry) and called for a plebiscite on self-determination as soon as practicable,possibly by next year. ‘What’s most important is to make sure our people makean educated decision on the political status they want to move toward’, Calvosaid in a 20 June radio address. ‘For nearly half a millennium the Chamorropeople have been unable to reach their full socio-economic potential because ofour political status. Now, more than ever, it is important to move forward, whilethere are still Chamorros left to express our right to self-determination.’50

In a statement to the United Nation’s Committee on Decolonization,delivered on his behalf by his sister (Clare Calvo) and the Director of Guam’sDecolonization Office (Ed Alvarez), Governor Calvo stated, ‘For far too long theChamorro people have been told to be satisfied with a political status that doesn’trespect their wishes first. For far too long the native people of Guam have beendealing with inequality of government. We have been dealing with taxationwithout full representation, with quasi-citizenship and partial belonging. Now itis time for us to realize our full political destiny, so we can take control and leadand live the way that is best for our people. I am urging this body to support ourhuman rights as citizens of this world, to help us become citizens of a place — ofour place in this world.’51

Guam’s self-determination efforts are rooted in a dilemma confronting manyChamorro people who are caught, as E. Robert Statham Jr notes, between anational polity in which citizens are equal before the law, regardless of ethnicity,and a homeland polity in which they wish to retain indigenous culture and groupprimacy. On the one hand, Chamorros have American citizenship and USaffiliation which most of them highly value; on the other, many desire a quasi-independent status that can assure them continuing control of Guam’s social,economic and political affairs — of the island itself. This has left manyChamorros with a dual identity as ‘both Americans and a distinct people’ in an

49 Ibid.50 For Governor Calvo 20 June 2011 Radio Address on Chamorro self-determination, see http://

www.kuam.com/story/14935661/2011/06/19/governors-weekly-radio-address-june-20.51 For the Governor’s statement to the UN Decolonization Commission: ‘500 Years Overdue’, see http://

www.pacificnewscenter.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14982:governors-speech-to-

the-united-nations-decolonization-commission&catid=45:guam-news&Itemid=156.

378 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fran

k Q

uim

by]

at 1

1:21

11

Febr

uary

201

2

incomplete political status that does not offer them an acceptable resolution oftheir predicament.52

Chamorros currently exert predominant local control on Guam by winningthe vast majority of elective offices, including governor, senators, villagecommissioners and various boards and commissions. Their tight-knit extendedfamilies, high voter turnout and control of local political parties have enabledthis political dominance. Holding most appointed directorships and civil servicepositions in the local government, Chamorros manage its machinery andadminister its financial and service resources. The indigenous population alsocontrols a considerable portion of the island’s land, with the Government ofGuam holding 20 to 25% and Chamorro families and individuals owning muchof the private acreage. But less than half of the island is available for privateownership, and increasing numbers of non-Chamorros are acquiring land due toimmigration and tourism-related investment.53