The State of the Question Regarding Early Medieval Fortress Construction in Southern Germany

Transcript of The State of the Question Regarding Early Medieval Fortress Construction in Southern Germany

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133

The State of the Question Regarding Early Medieval FortressConstruction in Southern Germany

Peter Ettel*Bereich Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Löbdergraben 24a, D-07743Jena, Germany

AbstractEarly medieval fortresses and fortifications in southern Germany, and consequently both within theFrankish region and in the region influenced by the Franks, usually filled more than one function.Indeed, even large-scale fortifications, which sometimes are denoted simply as refuges (Germ.Fluchtburgen) often can be identified as multi-functional. Fortresses were a central tool of rule for kings,the church, and the high nobility beginning in the seventh century, and then especially again duringthe tenth century. This was equally true in the context of the development of territorial lordships, andin the assarting and development of new lands, both within long-settled areas and on the frontier,from the tenth century onwards, and went hand in hand with the development of new types offortifications. In addition, fortifications also served as symbols of power. The nobility certainly alwayshad a part to play in these developments, and sometimes a decisive role. Thus, rather than a “darkcentury,” the tenth century saw a flowering in the construction of fortresses and fortifications, whichwere more multifunctional, multi-dimensional, and differentiated than had been true at any otherperiod in the early Middle Ages.

1. Historiographical Background

The construction of fortresses and strongholds in early medieval history was part of a broaderpattern of a multi-phased process of “Frankisization” (Frankisierung) in the lands east of theriver Rhine, stretching over southern, middle, and northern Germany. This process beganwith the victories of the Franks over the Alamanni (496) and Thuringians (531), whichstretched to the territories of the Danes and Vikings. The Frankish empire achieved itsgreatest territorial extent during the reign of Charlemagne (768–811), and stood at this timeas a great power on an equal footing with the empires of the Byzantines and the Arabs. Dur-ing the early middle ages, that is the period from roughly the sixth century through the 11thcentury, there were two main areas of fortress construction. These were the Frankish, orFrankish-influenced region, which bordered upon the Saxon region to the northwest, andthe Slavic-influenced region. Following his conquest of Saxony, Charlemagne’s empirebrought the Frankish region into direct territorial contact with the Slavic region (Fig. 1.1).The older historiographical tradition concerning the Frankish region, up through c. 1980,

was founded upon several syntheses that took a supra-regional approach to the topic. Amongthese was R. von Uslar’s 1964 study, “Studien zu frühgeschichtlichen Befestigungenzwischen Nordsee und Alpen”.1 In the following decade, a number of regional analyses orreports were published regarding fortresses in northern Hesse, Hesse, and Mainfranken,and northern Bavaria by R. Gensen, K. Weidemann, and K. Schwarz, respectively. H. Patzealso published a historical interpretation of fortresses, which raised important legal and con-stitutional issues.2 In addition to these regionally focused studies, a number of monographs

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

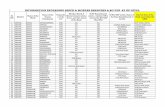

Figure 1. 1 The Empire of Charlemagne around 800 and the region of the West Slavs. - 2 Early Medieval fortifications insouthern Germany east of the river Rhine: ●● = identified as early medieval fortifications on the basis of topographicalfeatures, ■■ = excavated fortifications.

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 113

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

114 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

dealing with particular fortresses were published, including P. Grimm’s study of Tilleda, G. P.Fehring’s work on Unterregenbach, and G. Wand’s book on Büraburg.3 These were amongthe first studies to provide a detailed examination of the defences and construction of earlymedieval fortifications that were based, at least in part, on extensive excavations.However, the depictions of the construction of fortresses were influenced, in some

cases, by politically driven historical models, which had been developed by Schlesingerand his students.4 In the Slavic regions, state ideology, i.e. communism, played asignificant role as well. Research in the two German states, that is East and WestGermany, went in separate directions, influenced by very different outlooks and empha-ses. One example of this is the work by H. Brachmann, “Der frühmittelalterlicheBefestigungsbau in Mitteleuropa. Untersuchungen zu seiner Entwicklung und Funktionim germanisch-fränkischen Gebiet,” (Early Medieval Fortress Construction in CentralEurope: An Investigation of their Development and Function in the German-FrankishRegion) which provides a first-rate survey of the subject, but is nevertheless far tooone-sided because it was influenced by political, especially communist, ideology.5 Thereunification of Germany in 1989/1990 therefore marks a major shift in the scholarlytreatment of medieval fortifications.Over the course of the last 20–25 years, there has been enormous growth in the research

and publications on early medieval fortress construction. Numerous surveys and presenta-tions of Frankish-style fortifications have appeared in volumes of scholarly essays, as well asmore popularly oriented exhibition catalogues of excavated sites. These include publicationsby Fehring, Wieczorek, and Hinz, von Freeden and Schnurbein, as well as the exhibitioncatalogue of the exhibit “Archäologie in Deutschland 2002”.6 My own work in 2001utilized the extensively excavated sites at Karlburg, Roßtal, and Oberammerthal to drawbroader conclusions about 250 or so fortifications in northern Bavaria.7 The valuable hand-book, Burgen in Mitteleuropa (Fortifications in Central Europe), published in 1999, includes achapter on fortress construction in early medieval Europe, as does the companion volumeto the 2010 exhibition “Die Burg”.8 Inventories of historical sites in, for example, Bavariahave led to the publication of excellent topographical plans.9 Finally, recent scholarly inves-tigations have led to the publication of a series of monographs on individual fortresses,including Grimm’s second volume on Tilleda, P. Donat’s study of Gebesee, my own publi-cations on Karlburg, Roßtal, and Oberammerthal, M. Hensch’s work on the fortress ofSulzbach, and B. Friedel’s study of the fortification at Nürnberg.10

For a very long time, research on this topic focused on the dating and typology offortifications. Increasingly, however, more comprehensive excavations have led to a greaterinterest in the types of defences that were present, and greater attention to the internalstructure of the fortifications. The regions around fortifications also have received increasingattention from scholars. This type of study had been pioneered in the formerly communistcountries with regard to Slavic fortresses because of the ideological and political influencesthat were in play there.The following essay will outline the general chronological and geographical develop-

ments in fortress construction during the early medieval period. However, the mainfocus is on the tenth century, because it was then that the evidence permits the mostdetailed and multifaceted discussion of fortress construction, and related issues. Inaddition, the tenth century has been and continues to be at the centre of currentscholarly work on fortifications. This extensive body of scholarship provides an oppor-tunity to investigate these fortresses in their cultural–historical context, and to situatethem in the broader discussions of social–political structures, regional archaeology, aswell as ecological and economic history.

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 115

2. The Development of Early Medieval Fortress Construction

The first phase of the development of fortress construction throughout southern Germany(Fig. 1.2) began during the late Merovingian period, approximately in the second half ofthe seventh century, and can be traced back to the heartland of the Frankish kingdom, theRhineland.11 This phase of development was consolidated particularly during the second halfof the eighth century. It is during this period that the king appears clearly as the builder offortresses, and that fortresses were constructed over a wide area. During the ninth and tenthcenturies, increasing numbers of fortifications were built, and certain regional concentrationsof fortifications can be identified. Overall, however, the later period largely mirrors the ear-lier period. We do not see an expansion of the geographical area in which fortresses are builtuntil the eleventh century. However, the tenth century does witness a change in the struc-ture of fortresses. First, there was the development of the so-called Hungarian forts in the firsthalf of the tenth century. Second, this period witnessed the development of fortified centersof lordship, which might also be detectable in the construction and layout of two-partfortresses, comprising a main stronghold and a fortified bailey. During the eleventh century,large strongholds begin to disappear, and are replaced by smaller fortresses that wereconstructed on high points or in lowlands.In this period, fortifications, almost all of which were constructed on a high point, and, as a

consequence, are known as “Höhenburgen”, can be divided into three basic types based ontheir form and their construction.12 The first of these types is the “Ringwall” and the secondis the promontory fort (Germ. Abschnittsbefestigung), which is characterized by a wall that cutsacross a plateau, facing the side that permits ingress. The last type is the geometrically shapedfortress, which begin to appear in the course of the ninth and tenth centuries. These latterfortifications were not built to take advantage of the natural topography, and many of them,as a consequence, demonstrate a geometrical shape, often rectangular, half-circular, or oval.Three different types of fortress construction can be identified (Fig. 2) based largely on

reconstructions developed through analyses of excavated sites. These are drywall construc-tion, mortared wall construction, and “heaped up” walls. Dry walls were, in some cases, free-standing. In other cases, they had earth and timber walls behind them (Fig. 2a. b above).Mortared walls also could be either free standing, or have a blended construction, in whichthey had an earth and timber wall behind them (Fig. 2b). Both dry wall and mortared wallfortifications were widely diffused from the earliest period throughout the entire east Frankishregion, east of the Rhine. In this context, it is possible to identify a progression in the types offortifications that were constructed, although this certainly is not a fixed pattern that is appli-cable in every case. There is clear evidence of the construction of mortared walls in Hesse froman early date, and perhaps from the end of the seventh century.13 These include, for example,Büraburg and Christenberg.14 In northern Bavaria, mortared walls are detectable at Karlburgfrom no later than the second half of the eighth century. By the tenth century, the techniqueof constructing mortared walls was diffused universally, both to strengthen the front-side ofwalls, or as free-standing walls. Often, these mortared walls were equipped with several towerson their front sides. By the 11th century, mortared walls became prevalent in the Frankishinfluenced fortress region.The tenth century witnessed a high point in the development of fortress construction. On

the other hand, this period also marked a distinct break with the past. The danger posed bythe Hungarians and the introduction of fortresses constructed by and for individual noblefamilies can be understood as representing dramatic political changes, not only in southernGermany, but throughout central Europe. During the tenth century, both fortresses andthe construction of strongholds were multilayered, differentiated, and multivalent.

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Figure 2. Types of fortifications: (a) facing dry stone wall at the Eiringsburg; (b) dry stone wall with wood-earth-construction (above) and dry stone wall with mortar wall and towers of the later Ottonian period in Roβtal(bottom); (c) earth rampart at the Karlburg.

116 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

3. Refuges Against the Hungarians and “Heaped up” Walls

For between 50 and 60 years, forces of mounted Hungarians repeatedly raided the EastFrankish kingdom (the German kingdom after 925), in the lands of contemporary Germany,Italy, France, and the Iberian peninsula (Fig. 3.1) causing severe destruction as “the scourgeof the West.” Contemporary historical works such as those of Regino of Prüm andWidukind of Corvey offer testimony regarding the havoc caused by the Hungarians. Thelatter were feared for their style of combat and arms, which were typical of steppe peoples.They specialized in mounted combat, which allowed them great speed and flexibility in bothbattle and in raids. After successful attacks, the Hungarians were able to withdraw veryrapidly, and put great distance between themselves and their pursuers. Their reflex bows

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Figure 3. 1 Historically referenced Hungarian attacks between 933 and 955. - 2 Topographical plan of the“Frauenberg” above the monastery of Weltenburg with the excavated areas, 6 = excavation in 1966. - 3 Topographicalplan of the “Waldburg” near Häggenschwil. - 4 Topographical plan of the “Birg” near Hohenschäftlarn.

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 117

allowed them both to shoot from the saddle, and to hit their opponents at relatively greatdistances. In some cases, they were able to use fire arrows against settlements, monasteries,and cities, as well as against wooden strongholds and fortresses. Moreover, in the battlearound Augsburg (955), the Hungarians are reported to have brought with them siege equip-ment and tools to bring down the walls. This meant that the Hungarians had matched themilitary technology of the East Frankish kingdom.15

In 1930, P. Reinecke argued that high walls were typical of the “Hungarian” strongholds,that is, refuges, that were constructed in southern Germany.16 This view continues to play animportant role in the modern scholarly treatment of this topic. The best-known and histor-ically documented example of refuge against the Hungarians is from St. Gall (Fig. 3.3).According to a report by Ekkehard IV, a wall that was protected by both a ditch and a barrier

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

118 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

was raised up in 926 because of the danger posed by the Hungarians. However, this refuge,the “Waldburg” near modern Häggenschwil, was not attacked by the Hungarians. The1.4 hectares (3.5 acres) area within the fortification served as a refuge for more than 100monks from the monastery of St. Gall, which was located about 6.5 kilometres (four miles)away. The cross, memorial book, and treasury of the monastery also were taken from thechapel at St. Gall and brought into the refuge.17

There was a similar situation at the monastery of Schäftlarn. The monastery was establishedbetween 760 and 764 in the valley of the river Isar in the foothills of the Alps. About onekilometre (0.6miles) north of the monastery, there was a stronghold in the forested landon the opposite bank of the Isar (Fig. 3.4). Here, there was a plateau, which dropped precip-itously for 90meters on three of its sides. The site was almost predestined to serve as a forti-fication. The area of the plateau, itself, which measured some eight hectares, was protectedby a 300 meter long promontory fort. This wall, which still survives to a height of ten meters,was protected by a double system of trenches. The southwestern portion of the wall wasfurther protected by several rows of zig-zagging ditches. Because this fortification has notbeen excavated, the dating of its construction must remain hypothetical. But the site mayoriginally have been a Carolingian stronghold, which was later equipped with a wall duringthe period when the Hungarians posed a major threat.18

A very similar situation can be observed with regard to the Frauenberg fortification, whichis located above the monastery of Weltenburg (Fig. 3.2). The massive Wolfgangswall, whichstill survives to a height of 11 meters, was protected by a ditch, and was equipped with atower in the centre of the wall. It dominated the plateau of the Frauenberg, which alsodropped precipitously on three sides, and was almost completely surrounded by the watersof the Danube river. The presumed site of the gate in the wall was excavated in 1966 byW. Sage. In 1977, Sage dated the site to the tenth century. Then, Spindler dated the siteto the late antique period. Finally, Hensch re-dated the site again to the Ottonian period.19

Unfortunately, the excavations in 1966 only touched the outer foot of the wall, itself. As aresult, it remains an open question what methods were utilized in building the wall. Whetherthere was a pre-medieval fortification on this site or if there were several phases in the con-struction of this fortress also remain open questions. The material in the wall consists of clay,earth, and some very large stones. There is no evidence for the use of wood in its construc-tion, or for a mix of building materials on the wall’s outer surface. There is a burn layer onthe upper surface of the body of the wall, which stretches down to the old route to the wall.This shows that in addition to the utilization of wood for the construction elements thatsurmounted the wall, understood as a palisade or a breastwork, the builders also employedwood elements in the area of the gate. All of these were destroyed by fire.In the more than 80 years since Reinecke introduced the topic of defences and fortified

refuges against the Hungarians, it is clear that the topographical features of the fortificationshave played the dominant role in defining the nature of these installations. Characteristic inthis regard is the treatment of the early medieval walls that still survive to a height of four tosix meters. The ditches that protected these walls were, on average, ten to twelve meters inwidth. Entrance into the internal area of these strongholds was provided by simple gates orpassageways that bent toward the gate along the edge of the fortification, or conversely alongthe side of the edge of the plateau on which the fortification was constructed. This type ofpromontory fort often was characterized by multi-layered systems of ditches, which blockedentrance to the plateau. By contrast, circular walls (Germ. Ringwälle) were not commonlypart of the defences. Over the past several decades, it has been demonstrated, in addition, thatthe range of obstacles that protected promontory forts also included simple ditches with wallsbehind them, as well as piled-earth obstacles, and fields that were filled with ditches.

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 119

However, in analyzing the state of the question regarding these types of fortifications, it isnecessary to draw attention to a sobering conclusion.20 Of the fifty or so refuges against theHungarians that have been postulated in literature, some for quite a long time, there are onlya handful that can be demonstrated with great likelihood, albeit without absolute certainty,on the basis of the excavations to have been “heaped-up” walls that were constructed inthe period of the Hungarian raids from the end of the ninth century up through the first halfof the tenth century. Among these are Karlburg, Veitsberg, and likely also the Wolfgangswallover Weltenburg. However, the purpose and dating of the great majority of the so-called“Hungarian walls” must remain uncertain. Some of the sites that have been suggested in thisrole certainly should be removed from the list.The identification of individual fortifications as refuges against the Hungarians should be

viewed with considerable scepticism, and must be proven in each case. On the basis of theirimportance, as well as the considerable evidence for settlement, including finds within thedefended areas, it is quite clear that Karlburg, Veitsberg (see more on both below), andWeltenburg were not simply refuges that were utilized in periods of emergency. Topographicalcharacteristics such as high walls are not sufficient for an interpretation of these sites as refugesagainst the Hungarians. Such an interpretation would depend also on the identification ofadditional obstacles for those attempting to approach the fortification, particularly fields thatwere prepared with ditches or earthen berms. The identification of such obstacles must remainhypothetical in southern Germany until sites have been investigated through excavations.21 Byanalogy, the historical depiction of this kind of fort at St. Gall does permit the dating to theHungarian period of “heaped up” walls with concomitant obstacles to hinder approach, andto interpret these sites as refuges. Nevertheless, such a conclusion is too simplistic, and shouldbe avoided in the absence of investigations of the internal areas of these strongholds.

4. City Defences

External dangers, such as the Hungarian raids, certainly were a reason for the establishment ofdefences both near monasteries, and around episcopal seats, such as Eichstätt or Würzburg,and even central places of the highest rank, such as Regensburg. Eichstätt was establishedas a Benedictine monastery in 741 by St. Willibald, and soon after was raised to the statusof an episcopal seat, between 741 and 750. In contrast to the contemporary episcopal foun-dations at Würzburg, Büraburg, and perhaps even Erfurt, Eichstätt was not established inconjunction with, or even within a fortress. It was not until 908, in the context of the dangerposed by the Hungarians, that Eichstätt was fortified. In this year, Bishop Erchamboldobtained a license from King Louis the Child (899–911) on behalf of Eichstätt to establisha market, with concomitant control over tolls and minting, as well as permission to constructa fortification, i.e. “to construct a fortress to defend against attacks by the pagans.”22

Excavations in 1984 and in 1985–1986 revealed what may have been a ditch that was dug,at least in some places, in two separate phases. The ditch comprised two levels. At the top,this “v-shaped” ditch was 12meters in width, and was four meters in width at its bottom.This ditch was accompanied by a palisade, which was located, on average, one meter behindinner edge of the ditch. (Fig. 4.1–2). It is likely that the material from the ditch was used toconstruct the wall, although this has not been demonstrated conclusively. The fortificationhad a length of approximately 700meters, and was round in form. It should be understoodas the same fort that was constructed by Bishop Erchambold in 908.23

Regensburg, which was established in 179 AD as the camp of the Roman legion IIIItalica, survived the period of barbarian invasions (Fig. 4.3). From the Merovingian periodonwards, Regensburg served as a ducal and royal palace, as well as an episcopal seat. As a

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Figure 4. 1 Eichstätt: plan of the fortification after 908. 2 Reconstruction of Eichstätt in the tenth century.- 3 Regensburg in early medieval period with churches, legionary wall, and the so-called “Arnulfmauer”.

120 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

consequence, the city had considerable political and economic prestige, and served as animportant role as a centre of trade along the Danube. The Arnulfian wall, constructed by DukeArnulf around 920, was intended as a defence against Hungarian attacks. This wall wasprotected by a double system of ditches and enclosed an expanded area of the city of approx-imately 30.5 hectares (75 acres), including the region around the monastery of St. Emmeram.24

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Figure 5. 1 Tilleda: plan of the tenth and 11th century. 2 Topographical plan of Roβtal with the excavated areas from1960 to 1994 and 2000.

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 121

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

122 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

5. Palaces and Fortresses that Resembled Palaces

Tilleda, located in contemporary Sachsen-Anhalt, demonstrates the types of developments thatcould take place in fortifications during the Ottonian period. Tilleda possessed a palace, palacechapel, storage buildings, and a settlement of craft producers, all of which were protected by amulti-part fortified installation.25 Tilleda is typical of tenth-century palaces that wereconstructed with defences on high points. This type of palace was a new development thatstood in contrast to palaces of the eighth and ninth centuries, most of which were not fortified.26

The palace was divided into two parts. These were a main fortress (Germ. Hauptburg) ofone hectare (2.5 acres) on the east side, and a two-part (later three-part) fortified bailey(Germ. Vorburg) in the west and south, which enclosed some four hectares (10 acres)(Fig. 5.1). Within the area of the main fortress, there were a number of buildings that wereconstructed around a central space. There are three identifiable periods of construction upthrough the time when the site was abandoned in 1200, which witnessed the constructionof numerous high prestige buildings with stone foundations. These include the palace chapel,the main hall, and the royal accommodations. The two-part bailey shows a dense area ofconstruction, with about 200 pithouses/pit dwellings (Germ. Grubenhäuser). The southernpart of the bailey is characterized by both sunken-floored structures, and houses that werebuilt on level ground and utilized posts in their construction (Germ. Pfostenhäuser). Thelatter may have served as sheds for storage facilities. The western section of the bailey hadguard stations, storage facilities, and dwellings. In addition, there is considerable evidencefor the production of both cloth and other craft goods in this part of the bailey. For example,it is clear that in addition to work on both ivory and bone, metal goods also were producedthere, including iron and copper items.The fortress of Roßtal, near Nürnberg (Fig. 5.2), which measured almost six hectares in

area, was comparable in size to palaces.27 Historical sources mention this fortification inthe context of a battle fought there on 17 June 954. The stronghold, which was held bysupporters of the King Otto I’s son Liudolf, withstood a siege led by Otto. Over the courseof the first half of the tenth century, the Carolingian-era timber and earth fortification, whichwas enhanced with a dry stone wall, was further strengthened with berms and protectiveditches. In addition, the original dry stone wall front of the fortress was enhanced with amortared stone front measuring approximately one meter in width. In the areas where thefortress was particularly exposed, namely along the plateau, the wall was further strengthenedby a tower and an additional protective ditch (Fig. 2b).The internal area of the fortress was already heavily utilized and divided into separate sec-

tions during the Carolingian period. Excavations of a large part of the internal surface area ofthe fortress reveal a functional and planned out division of the space, particularly for craftproduction. This includes both pithouses and work trenches, as well as spaces for the con-struction of buildings that utilized post-type construction on level ground. Traces of fencesin form of post holes leading from the back side of the wall divided the flat internal area inthe south-western part of the fortress into three separately functioning units, which enclosedstorage facilities for hay or dwellings, silos, and perhaps stalls or barns. This tri-part division ofthe area was maintained throughout the entire period that the fortress was in use, andrepresents at least three phases of development from the origin of the installation until itwas abandoned during the second half of the tenth century.

6. Royal and Monastic Estates

Generally, royal estates are seen as standing below the palaces in terms of importance. Theseestates comprised a group of central places whose development was dependent on a number

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Figure 6. 1 Archaeological-historical topography of the area of Karlburg with castle and valley settlement, height above250m a.s.l. grey screened. - 2 Phases of the Karlburg: A Carolingian; B Ottonian. - 3 Reconstruction of the fortificationof the Karlburg. (a) Carolingian; (b) Ottonian. - 4 Historical topography of the basin of Bad Neustadt a.d. Saale. 5 Plan ofthe fortification of the “Veitsberg” near Bad Neustadt a.d. Saale with the excavated areas. 6 Aerial photo of theVeitsberg with the excavated areas from 2011, in the background the basin of Bad Neustadt a.d. Saale with the riverSaale and the village Salz, view from the northwest.

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 123

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

124 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

of different factors. Each one of these royal estates certainly should be considered individu-ally, although at present the state of archaeological research is still quite preliminary. Gebesee,located in the Erfurt district in Thuringia, makes clear the considerable importance that couldbe attained by an Ottonian monastic estate. In the case of Gebesee, the level of importancewas comparable to a palace.28

Numerous excavations of Karlburg in Franconia, undertaken between 1971 and 2008,permit insights into the structure of a royal estate.29 By comparison with palaces, whichare characterized by the dense concentration of elite building elements within a small area,at Karlburg these same elite building elements are distributed over a much wider area(Fig. 6.1). Both historical and archaeological evidence provide information about a coherentsettlement complex that included two fortifications, one at Karlburg and the other on theGrainberg, located on the other side of the river Main. There was a settlement in the valleybelow Karlburg, which include a royal estate as well as a monastery, and a landing area forships along its central stretch. This settlement was founded during the seventh century, andcontinued to develop up through the tenth century and beyond. During the course of thetenth century, the settlement was fortified. The settled area of the valley extended forapproximately one kilometre (0.6miles) in length and for a width of 200meters (656 feet),with a total surface area of approximately twenty hectares (49 acres).The originally royal fortress at Karlburg came into the possession of the bishops of

Würzburg in the period 751–753. During the first half of the tenth century, the apparentlyCarolingian-era defences were abandoned. The ditches were filled in and leveled off, as anewer, larger installation was established on the previously unutilized land. The new fortifi-cation, which had walls measuring 170× 120meters ( 557 × 393 feet), had an internal area of1.7 hectares (4.2 acres) (Figs. 6.2 and 6.3). The new fortification took on a bow-shape,defined by the plateau it bordered.30 The defences comprised a wall, which was constructedfrom earth and stone, a so called “heaped up” wall. The wall was approximately 9–10meters(29–32 feet) (in width, and was protected by a ditch, but not by a berm. This phase ofdefences also included a small, bow-shaped wall, approximately 150meters (492 feet) inlength, which was located some 100meters (328 feet) in front of the eastern edge of themain wall. This forward wall also had a protective ditch.31 This smaller wall had a widthof 5.5meters (18 feet) and still survives to a height of 0.8meters (2 feet). The protective ditch,which also did not have a berm, was 5.5meters (18 feet) wide and 1.7meters (5 feet) deep. Aswas true of the main wall, the smaller, forward wall had a “heaped-up” construction. Anadditional 100meters (328 feet) before the smaller wall was yet another barrier comprising awall and ditch, this one which survives today to a length of 40meters (131 feet). These twobarriers which projected toward the rising ground north of the main wall represented effectivebarriers to approach from this direction, particularly for mounted forces.The 20-hectares (49 acres) large settlement in the valley of the Main that was located

below Karlburg (Fig. 6.1) also was fortified during this period. The approximately six hectarecentral area of the settlement, which included both the monastery and the landing area forships, was enclosed within a seven to eight-meter wide and three-meter deep ditch, andperhaps a simple earthen wall as well.Salz, located on the Frankish-Saale, provides a similar example of a royal estate district. A tithe

of the revenues from the royal estate at Salz as well as from the royal church of St.Martin in Brandwas granted to the bishopric of Würzburg when it was first established. Numerous settlementsand cemeteries from the Merovingian and Carolingian period have been identified and partiallyexcavated in the area around Bad Neustadt on the Saale (Fig. 6.4). These sites permit the infer-ence that there was an extensive royal estate complex in this area.32 This early medieval centralplace was founded during the Merovingian period and, like Karlburg, represents the

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 125

development of an entire fiscal complex from the kernel of a royal estate. This estate underwentfurther development with the establishment of a palace at Salz, which appears for the first time inthe written record during a visit by Charlemagne in 790. Thereafter, there are numerousaccounts of visits and stays by rulers, kings, emperors, and ambassadors at Salz in the period790–948.The multifaceted central place at Neustadt on the Saale, which was located along a main

transportation artery between Bavaria and Middle Germany/Thuringia, will benefit fromexcavations in the next several years. The focus of this excavation will be to identify thelocation of the fortifications that were associated with this site and to identify where thepalace was located.33 In total, three medieval installations are known to have existed in theimmediate vicinity, all of which were present during the late Merovingian/early Carolingianperiod (Fig. 6.4). The first of these was located near the Liutpold heights, north of Salz, on aplateau that rises up from the valley of the river Saale. This site originally possessed twopromontory walls, which were approximately 60meters (196 feet) in length, and four meters(13 feet) in width. The second site is Salzburg, which is mentioned in the written sources forthe first time around 1160. The third site is Veitsberg. This plateau had a fortificationmeasuring 174× 160meters (570× 524 feet), and was located on a topographically advanta-geous location above the right bank of the Saale River, almost directly above the earlymedieval settlement on the left bank of the river (Fig. 6.5–6). Excavations undertaken in1983–1985, and 2006 have brought to light a main fortress and fortified bailey, whichunderwent several phases of construction during the Carolingian-Ottonian period. Excava-tions, which have been underway since 2010, have confirmed the view that the fortressunderwent several phases of construction, although the relative sequence and dating of theindividual phases of construction remain to be clarified.

7. Aristocratic Fortifications and Early Territorial Lordship

Aristocratic fortresses/ fortified complexes represent a new type of fortification thatdeveloped over the course of the ninth and tenth centuries. They were constructed to securelordship, and were intended for both security and the marking of territorial boundaries.These types of fortifications were less likely than cities to be sites where craft production,trade, or industrial production took place.34

One of many examples of early noble fortresses is the stronghold of the Ebersberg counts.As early as the ninth century, the counts had established a considerable concentration ofpower over the property around Ebersberg. Count Sigihard received the royal fiscal propertyat Sempt, which was located on the Salt Road, from Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia. Sigihard’ssuccessors added to this original grant the office of margrave of Carantania. Narrative sourcesrecord that the first fortress, which was constructed of wood, was replaced by a stonebuilding by Count Eberhard I in 933–934. As a consequence, the stronghold posed aninsurmountable barrier to Hungarian attacks. Excavations in 1978/–1979 (Fig. 7.1) show thatthere was a church on this site, which was protected by a wooden wall during theCarolingian period. However, as a consequence of what appears to have been an attack,perhaps by the Hungarians, the wooden walls were destroyed by fire, which is evidencedby a burn layer. The wooden wall was then replaced by a stone fortification, comprising amortared wall, which is also described in written sources.35

The Round Mountain (Germ. Runde Berg) fortress in Baden-Württemberg (Fig. 7.2)makes clear that the list of early noble fortresses in southern Germany likely is quite large.The fortress, which was built during the ninth or tenth century on Round Mountain,includes stone walls, towers, living quarters, a glass-windowed church that underwent three

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Figure 7. 1 Topographical plan from the “Schloβberg” of Ebersberg with the excavated areas. - 2 Aerial photo of the“Runder Berg” near Urach. - 3 Castles of the counts of Schweinfurt (filled signature: identified in written sources,unfilled signature; may have been in the possession of the counts Schweinfurt). 4 Reconstruction of Sulzbach-Rosenberg.- 5 Oberammerthal: Ottonian castles with main castle, bailey and churche.

126 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 127

or four periods of development, artisanal buildings, kilns/tiled stoves (Germ. Kachelofen), andfinds of reticular glass. All of these elements present a figure of a comfortable facility, which maywell bespeak its construction as an aristocratic fortified seat.36 However, this fortress does notappear in any written sources, and once again demonstrates that historical sources provide infor-mation about just a fragment of the total number of fortifications that once stood.We are better informed by historical sources about the fortresses of the Schweinfurter

counts, which also have benefitted from extensive excavations. These strongholds providea paradigmatic figure of the roles played by fortifications during the tenth century. Thietmarof Merseburg discusses the group of fortifications held by the Schweinfurter counts innorthern Bavaria in the context of describing their rebellion destruction in 1003. TheSchweinfurter counts, who from 939 onwards held office as margraves in previously ducalterritory of the Baviaran Nordgau and consequently possessed the entire region of north--eastern Bavarian in their own hands, built their network of fortifications during the secondhalf of the tenth century (Fig. 7.3). These fortresses served to secure their wide-ranging prop-erties. These strongholds included their namesake fortress at Schweinfurt, as well asfortifications at Kronach, Creußen, Banz, Burgkundstadt, and Oberammerthal, and perhapsthose at Sulzbach-Rosenberg, Nabburg, Cham, and Nürnberg as well.37 Thus, the militaryand political functions of the fortresses clearly come into focus. The fortifications representthe military, administrative, economic, and ecclesiastical–political points that together com-prised the backbone of the expansionist efforts of the Schweinfurter margraves to establish aterritorial lordship. In effect, their power rose and fell along with their possession of thesefortresses. In 1003, following his removal of the margraves, King Henry II destroyed all ofthe Schweinfurter strongholds and consequently sealed the end of this dynasty.Most of the Schweinfurter fortifications were not new installations. Rather, they were older

strongholds that were improved by the Schweinfurter counts during the tenth century, usingthe most modern techniques of fortification that were available at the time. Among theseimproved strongholds was the fortress at Oberammerthal in the Upper Palatinate region, whichwas constructed during the Carolingian period as a wood, earth, and stone installation, thatenclosed some two hectares (5 acres). During the tenth century, the site, which was now inthe possession of the Schweinfurter counts, was divided into two parts, with a main fortressand a bailey. Both of the sections were given the protection of a mortared wall. The baileywas further equipped with towers (Fig. 7.5). The main fortress had a church and other buildingsthat were intended to represent the power of the Schweinfurter counts.38

The fortress at Sulzbach-Rosenberg in the Upper Palatinate region (Fig. 7.4), which re-cently has benefitted from excavations, is the single best example of an aristocratic domesticfortress, which served the purpose of providing an administrative centre with correspondingbuildings that represented the power of its builders.39 For the first phase of construction ofthe fortress, in the eighth century, excavations have revealed evidence of construction inwood. During the second phase of construction, from the ninth to the early tenth century,there is evidence of a 15-meter (49 feet) long and 7.5meter (24 feet) wide building, whichwas constructed of quarried stone. This building had a relatively well developed apse on itseast side, which appears to have been a Carolingian-era fortress church. Excavations also haverevealed a 21.5meter (70 feet) long and 8-meter (26 feet) wide building, which utilized adouble-wall construction technique. This building possessed a stone fireplace that was setin the middle of the structure. Additional finds include fragments of window glass, someof which were painted with letters, which paint a figure of an establishment with a noblemanner of life. The third period of construction, during the tenth century, saw a heatedliving structure and other stone buildings. Thietmar of Merseburg’s use of the term “urbs”to describe the destruction of this place permits the inference that he was discussing

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

128 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

Sulzbach-Rosenberg. On the basis of the range of amenities found the fortress, including thecostly tombs in the outer area of the church as well as the apparent size and organization ofthe 4.2 hectare (5 acres) complex of the main fortification and bailey, Hensch came to theconclusion that this may have been the official seat of the counts of Nordgau, and that thecounts of Schweinfurt may have resided here in the role as royal governors.

8. Conclusion

Early medieval fortresses and fortifications in southern Germany, and consequentlyboth within the Frankish region and in the region influenced by the Franks, usuallyfilled more than one function. Indeed, even larger fortifications often can be identifiedas multi-functional, particularly during the tenth century.40 There is no questionregarding the military function of the fortifications. Their economic functions areindicated by the area devoted to craft production, which was sometimes quite large,particularly in larger fortifications up to and including palaces. Fortifications also playedan important role in controlling communications. In addition, there is evidence that anumber of fortifications also had a sacral role, particularly when there is evidence ofchurches having been constructed there. In this context, attention should be drawnto episcopal fortifications as central ecclesiastical places, and also to fortresses thatserved as episcopal seats.41

In addition to military, sacral, and economic functions, there likely were importantpolitical and administrative functions that were associated with fortifications. Thesecannot not be identified with any clarity through archaeological investigation, but cer-tainly are noted in historical sources as, for example, when fortifications are identified asthe locations where charters are issued, as the assembly points for tributes and taxes andthus as centres of administration, and also as the seats of landlords. Both finds within aswell as the type and manner of construction of the internal area of fortifications, includ-ing palace-like major buildings, high prestige buildings, internal heating systems, andcostly tombs indicate that these strongholds were lordly seats, whether noble or clerical.These fortifications also certainly could serve as refuges. Nevertheless, in contrast to theassumptions made in earlier scholarship, these noble seats only served this functionexclusively in a tiny minority of cases.Fortresses were a central tool of rule for kings, the church, and the high nobility beginning

in the seventh century, and then especially again during the tenth century. This was equallytrue in the context of the development of territorial lordships, and in the assarting and devel-opment of new lands, both within long-settled areas and on the frontier, from the tenthcentury onwards, and went hand in hand with the development of new types of fortifica-tions. In addition, fortifications also served as symbols of power.The nobility certainly always had a part to play in these developments, and sometimes

a decisive role. Even in the tenth century, fortifications took on an increased importancefor those nobles who understood that crises within the kingdom and external dangersoffered them the opportunity to expand their power. This was particularly true of thehigh nobility, which is made clear by the nature of noble fortifications and earlyterritorial lordships. As a consequence, the loosening and delegation of the royal rightto build fortifications, which was set out in the edict of Pîtres (864), profited boththe nobility and the church. Thus, rather than a “dark century,” the tenth centurysaw a flowering in the construction of fortresses and fortifications, which were moremultifunctional, multi-dimensional, and differentiated than had been true at any otherperiod in the early Middle Ages.

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 129

Short Biography

Peter Ettel studied pre- and early history, history, and provincial Roman archaeology at theuniversities of Munich, Kiel, and Bonn from 1981 to 1989. In 1985, he received his master’sdegree after completing a thesis entitled A Study early Bronze Age Depot Finds in the CarpathianBasin. He received his doctorate at Munich in 1989 after completing his thesis, Cemetariesfrom the Hallstatt Period in Upper Franconia. From 1990-1996, he served as a research associatefor Walter Janssen, who held the chair in pre- and early history at the University ofWürzburg. In 1996, he published his Habilitationsschrift with the title, Karlburg - Roβtal -Oberammerthal. A Study of Early Medieval Fortress Construction in Northern Bavaria. In 1998,he became the director of the Office for Preservation of Archaeological Monuments inMecklenburg-Vorpommern and accepted a teaching appointment at the University ofRostock. In 2000, he was appointed to the chair for pre- and early history at theFriedrich-Schiller University in Jena. His research foci are the iron age in Europe, pre-historicaland early historical construction of fortifications, the pre- and early history of Thuringia andcentral Germany, as well as settlement archaeology.

Notes* Correspondence: Bereich Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Löbdergraben 24a, D-07743Jena, Germany. Email: [email protected]

1 v. Uslar, Befestigungen; Ettel, ‘Frühmittelalterlicher Burgenbau’: Böhme et al. ‚‘Burgenforschung’.2 Gensen,‘Burgen’; Weidemann, ‘Archäologische Zeugnisse’; Schwarz, ‘Landesausbau’; Patze, Burgen.3 Grimm, Tilleda Hauptburg; Fehring, Unterregenbach; Wand, Büraburg;4 Schlesinger, ‘Ostbewegung’.5 Brachmann, Befestigungsbau.6 Fehring, Einführung; Wieczorek et al., Europas Mitte; v. Freeden et al., Spuren; Menghin et al., Menschen; Andrae-Rau,‘Bibliographie I–II’.7 Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal.8 Böhme, Burgen in Mitteleuropa; Brachmann, ‘Burgenbau’; Grossmann et al., Burg.9 Abels, Geländedenkmäler; Stroh, Geländedenkmäler; Pätzold, Geländedenkmäler.10 Grimm, Tilleda Vorburg; Donat, Gebesee; Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal; Hensch, Sulzbach; Friedel Nürnberg.11 Brachmann, Befestigungsbau, 62 ff.; Ettel, ‘Entwicklung Burgenbau’.12 Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal, 195 ff.13 Ettel, ‘Frühmittelalterlicher Zentralort’, 461.14 Wand, Büraburg, 90 ff.; Gensen, ‘Christenberg’.15 Daim, Heldengrab; Anke et al., Reitervölker; Büttner, ‘Burgenbauordnung’; Jahn et al., Bayern Ungarn, 81; Schulze-Dörrlamm, ‘Ungarneinfälle’.16 Reinecke, ‘Oppida‘ u. ’Staffelberg’.17 Schwarz., Fernwege, 157.18 Haberstroh, ‘Birg’, 114 f.; Schwarz, ‘Birg’, 222 ff.19 Sage, Weltenburg, 131–148; Spindler, ‘Weltenburg’; Hensch, ‘Frauenberg’; Rind, ‘Frauenberg’.20 Ettel, ‘Ungarnburgen’.21 Kerscher, ‘Steppenreiter’; Ettel, ‘Ungarnburgen’.22 Flachenecker, ‘Zentren’, 247 ff.23 Rieder, ‘Neue Aspekte’.24 Codreanu-Windauer et al., ‘Regensburg’; Röber, ‘Zwischen Antike’.25 Grimm, Tilleda Hauptburg; Tilleda Vorburg.26 Gauert, ‘Königspfalzen’.27 Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal, 100 ff.28 Donat, Gebesee; to central places: Ettel, ‘Grundstrukturen’.29 Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal, 32 ff.; Ettel, ‘Frühmittelalterlicher Zentralort’; Ettel, ‘Grundstrukturen’.30 Ettel, ‘Ungarnburgen’.31 Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal, ,33 fig. 3.

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

130 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

32 Wamser, ‘Neue Befunde’; Ettel ‘Grundstrukturen’.33 Ettel, ‘Entwicklung’.34 Ettel, ‘Burgenbau Franken’, 43 ff.; Böhme et al., ‘Burgenforschung’.35 Sage, ‘Ebersberg’; Haberstroh, ‘Schloßberg’.36 Koch, Runder Berg, 116 ff.; Kurz, Baubefunde.37 Ettel, ‘Entwicklung’ Emmerich, ‘Landesburgen’, 67 ff.;, Friedel, Nürnberg, 136 f.;, Hensch, ‘Genese’,38 Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal, 154 ff.39 Hensch, Sulzbach, 59 ff. 400 ff.40 Böhme, ‘Burgen Salierzeit’, 379–401; Ettel, Karlburg Roßtal Oberammerthal; Ettel, ‘Frühmittelalterlicher Burgenbau’;Ettel, ‘Burgenbau Franken’, 34–49.41 Streich, Burg und Kirche.

BibliographyAbels, B.-U., Die vor- u. frühgeschichtlichen Geländedenkmäler Unterfrankens. Materialh. Bayer. Vorgesch, 6 (Kallmünz:Lassleben, 1979).

Andrae-Rau, M., ‘Bibliographie zu den Burgen im Deutschen Sprachraum. Teil 1’. Zeitschrift für Archäologie desMittelalters, 21 (1993): 185–234.

Andrae-Rau, M., ‘Bibliographie zu den Burgen im Deutschen Sprachraum. Teil 2’. Zeitschrift für Archäologie desMittelalters, 22 (1996): 187–234.

Anke, B. et al., Reitervölker im Frühmittelalter. Hunnen – Awaren – Ungarn. Archäologie in Deutschland Sonderheft 2008(Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 2008).

Böhme, H.-W. (ed.), Burgen in Mitteleuropa: ein Handbuch (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1999).Böhme, H. W., ‘Burgen der Salierzeit. Von den Anfängen adligen Burgenbaus bis ins 11./12. Jahrhundert’, in J. Jarnutand M. Wemhoff (eds.), Vom Umbruch zur Erneuerung? Das 11. und beginnende 12. Jahrhundert – Positionen der Forschung.Mittelalter Studien 13 (München: Fink, 2006), 379–401.

Böhme, H. W. and Friedrich, R., ‘Zum Stand der hochmittelalterlichen Burgenforschung in West- undSüddeutschland’, in P. Ettel, A.-M. Flambard Héricher and T. Mc Neill (eds.), Études de castellologie médiévale; bilandes recherches en castellologie; actes du colloque international de Houffalize (Belgique) 4-10 septembre 2006; [le 23e Colloque In-ternational de Castellologie Château Gaillard], Château Gaillard, 23 (Caen: Publication du CRAM, 2008), 45–60.

Brachmann, H., Der frühmittelalterliche Befestigungsbau in Mitteleuropa. Untersuchungen zu seiner Entwicklung und Funktion imgermanisch-deutschen, Schriften zur Ur- u. Frühgeschichte, 45 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993).

Brachmann, H., ‘Der frühmittelalterliche Burgenbau’, in H. W. Böhme (ed.), Burgen in Mitteleuropa: ein Handbuch, 1 vol.(Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1999), 138–144.

Büttner, H., ‘Zur Burgenbauordnung Heinrichs I’, Blätter für Deutsche Landesgeschichte, 92 (1956): 1–17.Codreanu-Windauer, S. and Wintergerst, E., ‘Regensburg – eine mittelalterliche Großstadt an der Donau’, in A.Wieczorek and H.-M. Hinz (eds.), Europas Mitte um 1000, Beiträge zur Geschichte, Kunst und Archäologie (Stuttgart:Theiss Verlag, 2000), 179–183.

Daim, F. (ed.), Heldengrab im Niemandsland. Ein frühungarischer Reiter aus Niederösterreich, Mosaiksteine, Forschungen amRömisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseum, 2 (Mainz: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, 20072).

Donat, P., Gebesee – Klosterhof und königliche Reisestationen des 10.-12. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1999).Emmerich, W., ‘Landesburgen in ottonischer Zeit’, Archiv für Geschichte und Altertumskunde von Oberfranken, 37 (1957):50–97.

Ettel, P., Karlburg – Roßtal – Oberammerthal. Studien zum frühmittelalterlichen Burgenbau in Nordbayern, Frühgeschichtlicheund provinzialrömische Archäologie. Materialien und Forschungen, 5 (Rahden/Westf.: Leidorf Verlag, 2001).

Ettel, P., ‘Frühmittelalterlicher Burgenbau in Deutschland. Zum Stand der Forschung’, in P. Ettel, A.-M. FlambardHéricher and T. Mc Neill, Études de castellologie médiévale; bilan des recherches en castellologie; actes du colloque internationalde Houffalize (Belgique) 4-10 septembre 2006; [le 23e Colloque International de Castellologie Château Gaillard], ChâteauGaillard, 23 (Caen: Publication du CRAM, 2008), 161–188.

Ettel, P., ‘Burgenbau unter den Franken, Karolingern und Ottonen’, in G. U. Grossmann and H. Ottomeyer (eds.), DieBurg (Dresden: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2010), 34–49.

Ettel, P., ‘Der frühmittelalterliche Zentralort Karlburg am Main mit Königshof, Marienkloster und zwei Burgen inkarolingisch-ottonischer Zeit’, in J. Macháček and Š. Ungerman (eds.), Frühgeschichtliche Zentralorte in Mitteleuropa,Studien zur Archäologie Europas, 14 (Bonn: Habelt Verlag, 2011), 459–478.

Ettel, P., ‘“Ungarnburgen – Ungarnrefugien – Ungarnwälle” Zum Stand der Forschung’, in Zwischen Kreuz und Zinne.Festschrift für Barbara Schock-Werner zum 65. Geburtstag, Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Burgenvereinigung ReiheA, 15 (Braubach: Deutsche Burgenvereinigung, 2012a), 45–66.

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time 131

Ettel, P., ‘Die Entwicklung des frühmittelalterlichen Burgenbaus in Süddeutschland bis zur Errichtung vonUngarnburgen und Herrschaftszentren im 10. Jahrhundert’, in P. Ettel, A.-M. Flambard Héricher and T. Mc Neill(eds.), Études de castellologie médiévale. L’Origine du château médiéval. Actes du Colloque International de Rindern (Allemagne)28 août-3 septembre 2010, Château Gaillard, 25 (Caen: Publication du CRAM, 2012b), 139–158.

Ettel, P., ‘Grundstrukturen adeliger Zentralorte in Süddeutschland Repräsentationsformen und Raumerschließung’, inDas lange 10. Jahrhundert – struktureller Wandel zwischen Zentralisierung und Fragmentierung, äußerem Druck undinnerer Krise. Colloquium in Mainz March 2011 (forthcoming-a).

Ettel, P., ‘Frankish and Slavic Fortifications and Castles in Germany in the Time between the 7-10/11 Centuries’, inLondon Conference in London November 2007 (forthcoming-b).

Ettel, P., Werther, L. and Wolters, P., ‘Der Veitsberg - Forschungen im karolingisch-ottonischen Pfalzkomplex Salz,Stadt Bad Neustadt a.d. Saale, Landkreis Rhön-Grabfeld, Unterfranken’, Archäologisches Jahr in Bayern, 2011 (2012):129–131.

Fehring, G. P., Unterregenbach. Kirchen, Herrensitz, Siedlungsbereiche, Forschungen und Berichte der Archäologie desMittelalters in Baden-Württemberg, 1 (Stuttgart: Müller und Gräff, 1972).

Fehring, G. P., Einführung in die Archäologie des Mittelalters (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1987).Flachenecker, H., ‘Zentren der Kirche in der Geschichtslandschaft Franken’, in C. Ehlers (ed.), Places of Power – Orte derHerrschaft – Lieux de Pouvoir, Deutsche Königspfalzen, 8 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007), 247–261.

v.Freeden, U. and v.Schnurbein, S. (eds.), Spuren der Jahrtausende. Archäologie in Deutschland (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag,2002).

Friedel, B., Die Nürnberger Burg. Geschichte, Baugeschichte und Archäologie, Schriften des Deutschen Burgenmuseums, 1(Petersberg: Imhof, 2007).

Gauert, A., ‘Zur Struktur und Topographie der Königspfalzen’, in Deutsche Königspfalzen. Beiträge zu ihrer historischen undarchäologischen Erforschung, Veröffentlichenungen des Max-Planck-Instituts für Geschichte, 11,2 (Göttingen:Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1965), 1–60.

Gensen, R., ‘Frühmittelalterliche Burgen und Siedlungen in Nordhessen’, in Ausgrabungen in Deutschland,Monographien des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 1,2 (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-GermanischenZentralmuseums, 1975a), 313–337.

Gensen, R., ‘Christenberg, Burgwald und Amöneburger Becken in der Merowinger- und Karolingerzeit’, in W. Schlesinger(ed.), Althessen im Frankenreich, Nationes 2 (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1975b), 121–172.

Grimm, P., Tilleda, eine Königspfalz am Kyffhäuser. I. Die Hauptburg, Schriften zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte, 24 (Berlin:Akademie-Verlag, 1968).

Grimm, P., Tilleda. Eine Königspfalz am Kyffhäuser. II. Die Vorburg und Zusammenfassung, Schriften zur Ur- undFrühgeschichte, 24 (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1990).

Grossmann, G. U. and Ottomeyer, H. (eds.), Die Burg (Dresden: Sandstein, 2010).Haberstroh, J., ‘“Birg”. Ringwallanlage und Abschnittsbefestigung’, in K. Leidorf and P. Ettel, Burgen in Bayern(Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1999a), 114–115.

Haberstroh, J., ‘Schloßberg. Burg und Hauskloster der Grafen von Ebersberg’, in K. Leidorf and P. Ettel, Burgen inBayern (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1999b), 92–93.

Hensch, M., Burg Sulzbach in der Oberpfalz: archäologisch-historische Forschungen zur Entwicklung eines Herrschaftszentrums des8. bis 14. Jahrhunderts in Nordbayern (Büchenbach: Faustus, 2005).

Hensch, M., ‘Neue archäologische Aspekte zur mittelalterlichen Geschichte des Frauenberges’, in M. M. Rind (eds.),Höhenbefestigung der Bronze- und Urnenfelderzeit. Der Frauenberg oberhalb Kloster Weltenburg, Regensburger Beiträge zurPrähistorischen Archäologie, 16 (Regensburg: Habelt, 2006), 341–422.

Hensch, M., ‘Urbs Sulcpah – Archäologische Grabungen im Zuge der Neustadt-Sanierung. Zur Genese des früh- undhochmittelalterlichen Burgzentrums Sulzbach’, in Das Neustadt-Viertel. Festschrift zur Sanierung der Sulzbacher“Neustadt” 2010 (Sulzbach-Rosenberg: Stadtarchiv, 2010), 13–38.

Hensch, M., ‘Zur Genese der früh, hoch- und spätmittelalterlichen urbs und stat Sulcpah. Ergebnisse der baubegleitendenarchäologischen Untersuchungen in der Sulzbacher Altstadt 2008 und 2009’, Beiträge zur Archäologie in der Oberpfalzund in Regensburg, 9 (2011), 195–264.

Jahn, W. and Wurster, H. W. (eds.), Bayern - Ungarn Tausend Jahre : zur Bayerischen Landesausstellung 2001: Haus derBayerischen Geschichte, Veröffentlichungen. Bayer. Gesch. u. Kultur (Passau: Pustet, 2001).

Kerscher, H., ‘Gegen die Steppenreiter? – Neue Beobachtungen am Ringwall Vogelherd bei Kruckenberg, GemeindeWiesent, Landkreis Regensburg, Oberpfalz’, Archäologisches Jahr in Bayern (2010): 113–116.

Koch, U., ‘Die frühgeschichtlichen Perioden auf dem Runden Berg’, in H. Bernhard (ed.), Der Runde Berg beiUrach, Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Baden-Württemberg, 14 (Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1991),83–127.

Kurz, S.,Die Baubefunde vom Runden Berg bei Urach, Materialhefte zur Archäologie in Baden-Württemberg, 89 (Stuttgart:Theiss, 2009).

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

132 Fortress Construction in Early Medieval Time

Menghin, W. and Planck, D. (eds.), Menschen – Zeiten – Räume. Archäologie und Geschichte in Deutschland (Stuttgart:Theiss, 2002).

Patze, H. (ed.), Die Burgen im deutschen Sprachraum. Ihre rechts- und verfassungsrechtliche Bedeutung, Vorträge undForschungen, 19 (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1976).

Pätzold, J., Die vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Geländedenkmäler Niederbayerns, Materialhefte zur bayerischen Vorgeschichte, B2 (Kallmünz: Lassleben, 1983).

Reinecke, P., ‘Spätkeltische Oppida im rechtsrheinischen Bayern’, Bayrischer Vorgeschfreund, 9 (1930): 29–52.Reinecke, P., ‘Der Ringwall Staffelberg bei Staffelstein’,Archiv für Geschichte und Altertumskunde Oberfranken, 36 (1952): 12–32.Rieder, K.-H., Eichstätt’, in Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Deutschland, 15 (Stuttgart: Theiss, 1987), 36–45.Rieder, K.-H., ‘Neue Aspekte zur “Urbs” der Eichstätter Bischöfe’, in K. Kreitmeir and K. Maier (eds.), Verwurzelt inGlaube und Heimat, Eichstätter Studien N.F., 58 (Regensburg: Pustet, 2010), 1–21.

Rind, M. M., ‘Die Befestigung auf dem Weltenburger Frauenberg’, in K. Leidorf and P. Ettel, Burgen in Bayern(Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag, 1999), 97–101.

Rind, M. M., Höhenbefestigung der Bronze- und Urnenfelderzeit. Der Frauenberg oberhalb Kloster Weltenburg, RegensburgerBeiträge zur Prähistorischen Archäologie, 16 (Regensburg: Habelt, 2006).

Röber, R., ‘Zwischen Antike und Mittelalter. Thesen zur Ausgestaltung und räumlichen Entwicklung ausgewählterBischofssitze an Rhein und Donau’, in U. Gross, A. Kottmann and J. Scheschkewitz (eds.), Frühe Pfalzen– FrüheStädte. Neue Forschungen zu zentralen Orten des Früh- und Hochmittelalters in Süddeutschland und der Schweiz,Archäologische Informationen aus Baden-Württemberg, 58 (Esslingen a. Neckar: Geselllschaft für Archäologie inWürttemberg und Hohenzollern, 2009), 103–136.

Sage, W., ‘Ausgrabungen an der Toranlage des “Römerwalls” auf dem Frauenberg oberhalb Weltenburg, Lkr.Kelheim’, Jahresbericht zur Bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege, 15/16, 1974/75(1977): 131–148.

Sage, W., ‘Ausgrabungen in der ehemaligen Grafenburg zu Ebersberg, Oberbayern, im Jahre 1978’, Jahresbericht zurBayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege, 21 (1980): 214–228.

Schlesinger, W., ‘Zur politischen Geschichte der fränkischen Ostbewegung von Karl dem Großen’, in W. Schlesinger(ed.), Althessen im Frankenreich, Nationes, 2 (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1975), 9–62.

Schulze-Dörrlamm, M., ‘Spuren der Ungarneinfälle des 10. Jahrhunderts’, in F. Daim (ed.), Heldengrab im Niemandsland.Ein frühungarischer Reiter aus Niederösterreich, Mosaiksteine, Forschungen am Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseum,2 (Mainz: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, 20072), 43–63.

Schwarz, K., ‘Die Birg bei Hohenschäftlarn’, in Führer zu vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern, 18 (Mainz: v. Zabern,1971), 222 ff.

Schwarz, K., ‘Der frühmittelalterliche Landesausbau in Nordost-Bayern archäologisch gesehen’, in Ausgrabungen inDeutschland, Monographien des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 1, 2 (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 1975), 338–409.

Schwarz, K., Archäologisch-topographische Studien zur Geschichte frühmittelalterlicher Fernwege und Ackerfluren. ImAlpenvorland zwischen Isar, Inn und Chiemsee, Materialh. Bayer. Vorgesch. 45 (Kallmünz, 1989).

Spindler, K., ‘Archäologische Aspekte zur Siedlungskontinuität und Kulturtradition von der Spätantike zum frühenMittelalter im Umkreis des Klosters Weltenburg an der Donau. Archäologische Denkmalpflege in Niederbayern’,Arbeitshefte des Bayerischen Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, 26 (1985): 179–200.

Streich, G., Burg und Kirche während des deutschen Mittelalters. Untersuchungen zur Sakraltopographie von Pfalz- undBurgkapellen bis zur staufischen Zeit, Vorträge und Forschungen, 29 (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1984).

Stroh, A., Die vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Geländedenkmäler der Oberpfalz, Materialh. bayer. Vorgesch. B 3(Kallmünz/Opf.), 1975.

v. Uslar, R., Studien zu frühgeschichtlichen Befestigungen zwischen Nordsee und Alpen, Beihefte zum Bonner Jahrbuch, 11(Köln: Böhlau, 1964).

Wamser, L., ‘Neue Befunde zur mittelalterlichen Topographie des fiscus Salz im alten Markungsgebiet von BadNeustadt a. d. Saale, Lkr. Rhön-Grabfeld, Unterfranken’ Archäologisches Jahr in Bayern (1984): 147–151.

Wand, N., Die Büraburg bei Fritzlar. Burg - “Oppidum” - Bischofssitz in karolingischer Zeit (Marburg: Elwert, 1974).Weidemann, K., ‘Archäologische Zeugnisse zur Eingliederung Hessens und Mainfrankens in das Frankenreich vom 7.bis 9.Jahrhundert’, in Schlesinger, 1975, 95–120.

Wieczorek, A. and Hinz, H.-M. (eds.), Europas Mitte um 1000 (Stuttgart: Theiss, 2000).

History Compass 12/12 (2014): 112–132, 10.1111/hic3.12133© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd