Foreclosure sales

-

Upload

abtassociates -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Foreclosure sales

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Foreclosing on the neighborhood: Organized irresponsibility inforeclosure sales

Hannah Thomas, Ph.D., Abt Associates

Abstract

The foreclosure crisis presents an interesting problem. Foreclosures, if sold in the manner of a regular home sale, should not cause a marked difference in either the price that they are sold for, nor who they are sold to. Nor should their sale create secondary negative outcomes in the neighborhoods, towns and cities where they are sold. And yet the data and research over the last twenty years has documented a series of market distortions and negative outcomes associated with foreclosures and foreclosure sales. These market distortions and negative outcomes range from lower sales prices for foreclosed properties and neighboring properties (Haider and McGarry 2005; Immergluck 2010; Mallach 2010; Immergluck 2011), to increased investor purchase of foreclosed properties, to higher rates of vacancy and crime in the vicinity of the foreclosure (Haider and McGarry 2005; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck 2010; Mallach 2010),. These outcomes impact the longer-term trajectory of the neighborhood(Li and Morrow-Jones 2010).

Data point to the important role of the institution conducting the sale. Immergluck and Smith found that Federal Housing Authority foreclosures did not have a statistically significant impact on the prices of neighboring properties (Immergluck and Smith 2006b). The identified differencein those sales was the institution selling the properties, suggesting that differences in institutional foreclosure sales practices may create the negative spillover effects in neighborhoods. Yet despite the important role that the mortgage servicer plays, cities and towns have been stymied in their capacity to assign responsibility to any entity in seeking to recover the costs of poorly managed foreclosure sales.

Using data from Boston, this paper will argue that both the increased risk to the community from a foreclosure sale, and the inability of municipalities to assign responsibility emerge from the problem of organized irresponsibility – the phenomenon of a complex system where no one is in charge. The paper will explore the role of the organizations involved in the foreclosure sale focusing particularly on the mortgage servicer and their loss mitigation and asset managementpractices (including protocols, organizational arrangements and decision-making). With foreclosures continuing apace, understanding the organizational ecology of those involved in the foreclosure sale process provides important insights that can help fine-tune existing policiesand suggest new policies to prevent the loss of community assets as a result of foreclosures.

Introduction

1

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

The foreclosure crisis presents an interesting problem. Foreclosures, if sold in the manner of a regular home sale, should not cause a marked difference in either the price that they are sold for, nor who they are sold to. Nor should their sale create secondary negative outcomes in the neighborhoods, towns and cities where they are sold. And yet the data and research over the last twenty years has documented a series of market distortions and negative outcomes associated with foreclosures and foreclosure sales. These market distortions and negative outcomes range from lower sales prices for foreclosed properties and neighboring properties (Haider and McGarry 2005; Immergluck 2010; Mallach 2010; Immergluck 2011), to increased investor purchase of foreclosed properties, to higher rates of vacancyand crime in the vicinity of the foreclosure (Haider and McGarry 2005;Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck 2010;Mallach 2010). These outcomes impact the longer-term trajectory of theneighborhood(Li and Morrow-Jones 2010).

This paper will present data from an institutional ethnography showingthat it is the loss mitigation and asset management practices of the mortgage servicer that create these distortions and negative outcomes.The negative outcomes and market distortions actually end up harming not only the community surrounding the foreclosure, but also the mortgage servicer and mortgage-backed securities investors by reducingthe sale price of future foreclosure sales in the neighborhood, and increasing the risk of damage to properties currently in the foreclosure process.

This seems counter-intuitive and leads to the question: Why do servicers employ loss mitigation and asset management practices that distort the market for foreclosure sales and potentially harm their and their clients’ future asset interests? The answer, I will argue, is due to a phenomenon known as organized irresponsibility. Organized irresponsibility is the process wherein discrete decisions made by individuals operating within organizations that are part of a larger system result in negative outcomes for the system (or society) for which no one can be held responsible. When a system is characterized by organized irresponsibility it is harder for municipalities, states,federal governments, mortgage backed security investors and other injured parties to levy fines or hold any one individual organization responsible. As Hannah Arendt put it “no-one is in charge!”

Organized irresponsibility in the foreclosure sales market is characterized by the transfer of risk away from organizations. Organizational decisions to manage and limit risk exposure in the

2

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

foreclosure sales market, i.e., the distressed property disposition market, drive decisions by a servicer about how a property is managed,how contracts are written, and, ultimately, who is positioned to buy the property. Risk is transferred away from organizations able to isolate and protect themselves from risk, while that risk concentratesat the neighborhood level. New risks emerge as attempts to control risk by organizations in the system (e.g. servicer) interact with neighborhood character and create problems for a neighborhood in the absence of any state regulation or intervention. This creates a foreclosed property marketplace laden with financial potholes for a buyer and potentially negative costly outcomes for a neighborhood. Borrowing from Jacob Hacker, I call this process “risk shift” (Hacker 2006).

This pattern of risk shift has a distinct geographic pattern. Organizations with the power over decisions that impact foreclosure sales are national or even international, while the communities to which risk is shifted are local. Actors within organizations, such asthe servicer, make decisions aligned with the structured incentives ofthat organization. For organizations with power, in the case of the foreclosure sale, those incentives are to ensure maximum profit or, atleast, to minimize losses and ensure future business. Oriented towardsglobal capital markets, the stakeholders responsible for decisions over how a foreclosing or foreclosed property should sell are focused on minimizing portfolio losses and maintaining large operations. Localreal estate markets do not function in ways that fit with large administrative bureaucracies managing foreclosure sales en masse. Local real estate markets require flexibility and responsiveness to the potential buyer and to the distinctiveness of any particular property and neighborhood. The interaction between these two differently oriented systems creates frictions that manifest as new orshifted risks within the system.

These risks created as friction in the disposition of foreclosed property between the needs of global securities markets for large-scale transactions and local real estate markets focused on individualproperties are externalized and dumped at the local neighborhood level. The neighborhoods most vulnerable to these risks tend to be where foreclosures are concentrated, neighborhoods that have a long history of post-World War II capital abuses from redlining to targetedsubprime and predatory mortgage lending. These risks are above and beyond the risks already absorbed by public and private stakeholders in the foreclosure process and arguably would be unnecessary within a

3

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

differently structured credit market. Figure 1 illustrates the processof this risk shift.

Figure 1: Risk shift in foreclosure sales

Source: Developed by the author.

The following paper will first review the documented market distortions and negative outcomes resulting from how foreclosure salesare conducted and then turn to the literature on organized irresponsibility. Drawing on data from an institutional ethnography of foreclosure sales in Boston, it will then look at the asset management and loss mitigation practices that lead to these market distortions. The following section will seek to answer the question ofwhy the mortgage servicer, a key stakeholder responsible for the assetmanagement and loss mitigation practices that lead to market distortions, operates in the ways that it does. Finally the paper willexplore how these practices are a manifestation of organized irresponsibility and what policy makers might do about it.

Foreclosures, foreclosure sales and negative impacts on neighborhoods

4

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Foreclosures often negatively impact individuals and families living in or owning foreclosed properties (Nettleton and Burrows 1998;Nettleton and Burrows 2000; Nettleton 2001; Nettleton and Burrows 2001; Ernst, Keest et al. 2006; Ellen, Schwartz et al. 2009; Bradbury,Burke and Trieste, 2013; Thomas 2013). In addition, they can also increase the risk for a variety of negative impacts on neighborhoods and community assets where the foreclosures occur (Haider and McGarry 2005; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Campbell, Giglio et al. 2009; Center for Responsible Lending 2009; Coulton, Schramm et al. 2010; Buitrago 2011; Ergengor and Fitzpatrick 2011; Simon 2011). In this section I will review the literature on the relationship between foreclosures and neighborhood externalities, whatI call negative neighborhood outcomes, over the short- and long-term and then outline gaps in understanding the mechanisms that lead to these negative impacts. I make the case that the organization of the sales process plays a role in creating many of the neighborhood externalities seen in some neighborhoods hard hit by foreclosures. Throughout the literature review I will refer to foreclosures instead of foreclosure sales, since the literature uses foreclosures rather than breaking out particular sub-categories of the types of sale, an important oversight in helping us understand the dynamics at play.

Short term negative impacts on the neighborhood The evidence that foreclosures lead to negative neighborhood

impacts stems back to at least the 1970s. In the 1970s problems with the FHA 235 program1 led to vacant and abandoned properties because of foreclosures (Immergluck 2010).2 Short-term negative impacts pointed toin the literature include discounted sales prices, increased vacancy rates, and an increased likelihood of violent crime in the vicinity (Haider and McGarry 2005; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck and Smith 2006; Immergluck 2010; Mallach 2010; Mallach 2010; Immergluck 2011). Additionally, investor-buyers have strong interest in 1The FHA 235 program was a Federal Housing Authority program designed to lowerbarriers to homeownership by providing insurance for private lenders to lend in inner-city areas. The program fostered an unregulated mortgage lending environment in which unscrupulous developers sold poorly rehabilitated buildings to minority families. Those families unable to afford the work needed on these buildings often ended up in foreclosure. The program further helped to segregate America’s cities Gotham, K. F. (2000). "Separate and Unequal: The Housing Act of 1968 and the Section 235 Program." Sociological Forum 15(13-37). 2Unfortunately, no data seem to be publicly accessible on the impacts of the Savings and Loans induced foreclosure crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

5

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

foreclosed properties but research suggests investor-buyers are more likely to leave properties vacant or be poor landlords (Immergluck 2011). This can be harmful to the neighborhood. The following section reviews each of these short-term negative impacts on the neighborhood.

Foreclosed property price discounts. A majority of studies that look at the impact of foreclosures, focus on price changes resulting from foreclosures. Studies generally find that foreclosed and distressed properties sell at a discount (Haider and McGarry 2005; Immergluck 2010; Mallach 2010; Immergluck 2011) or do not appreciate as much as the properties that surround them (Pennington-Cross 2006). Obviously, house price trends are sensitive to the temporal context of the housing market and to the spatial characteristics of the neighborhood where the foreclosure occurs. In the current crisis, most researchers have found significant price discounts for foreclosure sales, though most analysis has been on REO properties rather than on short sales orauctions. These studies have not controlled for geographic heterogeneity. However, a 2012 study re-examining foreclosure data found that controlling for geographic heterogeneity using a fixed effects model substantially reduced the price discount from the foreclosure itself (Gerardi, Rosenblatt, Willen and Yao, 2012). This paper found that price discounts were greater for properties that werevacant, and properties that were lender owned and in below average condition. Conversely lender owned properties in above average condition saw positive effects from the foreclosure sale. The authors of the paper consider different interpretations of these findings, including that foreclosures may drive down prices from an oversupply, and that reduced investment in the property by lender owners may also drive down prices.

Since we are looking primarily at Boston, understanding the property discount rate in the context of a market full of multi-familyproperties is very important. A 2010 study by the Federal Reserve Bankin Boston examined REO sales discounts in Massachusetts (Lee, 2010). Lee found that 33 percent of REO sales in Massachusetts were small multi-family units and that these properties spent longer on the market than single-family and condominium REO properties. Importantly,small multi-family unit REOs, compared with equivalent regular sales, experience greater price differentials (40.6 percent) while single family (19.9 percent) and condominium (29.2 percent) REO properties have smaller differentials. However, these numbers do not take into account the physical state of the property itself or other confoundingvariables to ensure that we are comparing apples to apples. Using a composite model, Lee found that holding all things equal, a small-

6

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

multi-family REO sale in Massachusetts experiences a 4.6 percent discount, the largest discount of all properties in Massachusetts examined in this paper (Lee 2010).

Little writing exists trying to explain these notable price discounts. Some articles point to the neighborhood itself as a confounding factor in the price discounts experienced (and presumably other negative outcomes). Higher REO price differentials are experienced in neighborhoods that have a higher likelihood of foreclosure as determined by a higher share of high-cost loans, higherminority population, and lower income. These studies do not, however, explain the mechanisms in play that lead to the price discounts. This is surprising since case law on foreclosure auctions has developed in an attempt to prevent “price chilling,”-pricing property lower than its value-from occurring in the auction process.

Neighborhood spillover effects. Non-foreclosed neighboring property values arealso impacted by foreclosed and distressed property sales in a processknown as the “foreclosure spillover effect” (Rogers 2010). There is some disagreement about the dollar amount of the foreclosure spillovereffect or the marginal effect, given the potentially non-linear natureof the effect (Shlay and Whitman 2006). Controlling for confounding factors with econometric modeling, the effects demonstrated on surrounding property values from a foreclosure ranged from 0.9 percent(Immergluck and Smith 2006; Rogers 2010) to 8.7 percent (McKernan, Ratcliffe et al. 2009). Increased distance from the foreclosure in time and space reduced the marginal effect in most of the studies (Mikelbank 2008; Schuetz, Been et al. 2008; McKernan, Ratcliffe et al.2009; Rogers and Winter 2009) and early foreclosures seem to have a greater impact than later foreclosures (Been 2008).

Mechanisms of negative externalities from foreclosures. Most of the focus on the question of the foreclosure spillover effect has been on refining models to gauge the dollar losses in a neighborhood. Less effort has been put into examining the mechanisms leading to spillover effects. The primary assumed mechanisms are neighborhood blight from the foreclosure, a glut in the supply of properties on the market, and problems with valuation in the neighborhood (Haider and McGarry 2005).For example, the fact that foreclosed buildings might be more often abandoned or vacant could be at play in creating price discounts. Shlay and Whitman (Shlay and Whitman 2006) found a $7,627 price decline for regular properties with abandoned buildings neighboring them in Philadelphia. Whittaker and Fitzpatrick (2011) found vacant properties reduced surrounding properties’ values by 1.4 percent.

7

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Large numbers of properties coming onto the market potentially increase the supply of houses for sale, leading to lower prices for the property. Interestingly, in the literature these negative impacts are accepted as inevitable without questioning whether there might be problems in how the property is sold that could be rectified to prevent such negative externalities from occurring in the first place.

Pointing towards the question of whether such negative externalities are necessary, Immergluck and Smith (2006a) found that who the foreclosing lender is has some impact on the negative marginaleffect of the foreclosure on neighborhood property values. They found that Federal Housing Authority (FHA) foreclosures have no significant impact on property values in neighborhoods, while foreclosures with conventional mortgages do.3 This finding suggests that the foreclosure process and sale proceeds may differ by type of lender, perhaps because of internal process and policy, pointing to the possibility that institutional factors may play an important role in whether thereare negative externalities from a foreclosure sale.

The lack of research in understanding why the price of foreclosure sales is discounted and why the foreclosure spillover effect differs by lender, points to a need to better understand the foreclosure sale process. Indeed, Immergluck and Smith’s work reveals that FHA foreclosures do not have significant impacts on neighborhood property values suggesting the importance of the organizational structures involved in managing the foreclosure sale.

Increased rates of crime. There is some limited evidence that foreclosures are linked to increases in crime (Immergluck and Smith 2006). The hypothesized link between foreclosures and increased crime is that foreclosed properties are more likely to be abandoned and vacant leading to negligence and unchecked decay, i.e. the “broken window theory.” According to this theory, abandoned and vacant buildings offer signals of neighborhoods experiencing social disorganization (Shaw and McKay 1942; Sampson and Groves 1989). Social disorganizationtheory posits signs of disorder, such as vacant buildings, signal disinvestment and lead to migration, residential instability (Shaw andMcKay 1942; Sampson and Groves 1989; Sampson and Raudenbush 1999), increased segregation (Krivo, Peterson et al. 2009), and lack of social cohesion. With fewer “guardians” of the streetscape (Jacobs 1961) and markers of lower social cohesion, crime is more likely to

3 Federal Housing Authority mortgages are mortgages made typically to borrowers who do not qualify for conventional private market financing. FHA mortgages are those insured by the Federal Housing Authority to protect private lenders from risk of default loss.

8

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

occur. In the case of foreclosure sales, vacant and abandoned buildings act as a marker of lower social cohesion, as well as fewer eyes on the street, offering more opportunity to create spaces for illegal and dangerous activities.

Higher rates of investor-buyers. Research has found that in the most recent crisis there were a high number of investor-buyers active in the foreclosure sales market, particularly REO buyers (Immergluck and Smith 2006; Newburger 2010). The investor-buyers are often seen as a potential problem by policy makers because in some markets they are liable to either flip a property for a quick profit while making no repairs (Mallach 2010; Ergengor and Fitzpatrick 2011) or to hold the property and keep it vacant instead of finding tenants or reselling toan owner-occupant (Immergluck 2011). Indeed, Mallach points to the negative impacts accruing from foreclosures as being transitory if an owner-occupant purchases the property. However, where an investor purchases the property, Mallach suggests negative impacts can be longer term and more entrenched, depending on the intentions of the investor buyer (Mallach 2010).

In general, researchers and policy makers have thought that owner-occupants increase the stability and social capital built in a neighborhood; although, some research challenges this finding (Dietz and Haurin 2003). Thus, policy goals, especially in Boston, have tended towards increasing owner-occupant homeownership. In Boston, where the housing market has been “hot,” the foreclosure crisis and consequential drop in housing prices in some neighborhoods created an opportunity for families that might not otherwise have been able to afford homeownership to purchase. However, the combination of active investor-buyers and constraints in mortgage financing from conventional lenders meant that owner-occupant buyers have had less success than policy makers might have hoped. Active investor-buyers have been pushing community development corporations and other affordable housing developers out of the market, a challenge seen in deploying Neighborhood Stabilization Program funds (Newburger 2010).

Social capital and foreclosures. Less research has been completed on the impactsof foreclosures and foreclosure sales on neighborhood social capital. By social capital I mean “the collective value of all "social networks" [who people know] and the inclinations that arise from thesenetworks to do things for each other ["norms of reciprocity"].”4 The

4 Definition taken from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government website: http://www.hks.harvard.edu/programs/saguaro/about-social-capital Accessed January 10, 2014

9

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

literature on social capital has attempted to operationalize measures of social capital; looking at civic engagement such as voter turnout,trust in government, hours volunteering, or attendance at social clubs(Putnam 2000). We know that foreclosures result in lower rates of trust in institutions, such as banks, for those who lose their homes to foreclosure (Ross and Squires, 2011) but no study has examined the impact on trust in government institutions. We also know that foreclosure sales result in disrupted relationships and networks in the neighborhood; for example, school attendance (Been et al 2011) andschool performance (Bradbury, Burke and Trieste 2013). We also know that foreclosure and foreclosure sales mean that people, both owners and tenants of foreclosed buildings, must leave the neighborhood, reducing the number of eyes that are physically able to watch the street. The hypothesized link between increased crime rates and foreclosed properties is that there is lower social cohesion in neighborhoods experiencing foreclosure because residents must move out; as a result, fewer people are then living in the neighborhood (Immergluck and Smith 2006). Recent research demonstrates a link between high foreclosure neighborhoods and lower voter turnout in the 2008 elections (Estrada and Johnson 2012).

Long-term neighborhood change and foreclosures Short-term negative neighborhood impacts have effects in the medium and long term, yet forecasting those long-term impacts is difficult. Within the extensive neighborhood change literature few studies have looked at the overall medium- to long-term change at the neighborhood level resulting from foreclosures or how foreclosures are disposed or sold. In the medium-term, Coulton, Schramm and Hirsh (2010) looked at data for Cuyahoga County, Ohio, (Cleveland), which experienced an increase in foreclosures much earlier than the rest of the country, peaking in 2007. By February 2010, about half of the properties that had left REO status between 2004 and 2009, but had been sold originally as REO in the lowest price bracket, were vacant and delinquent on taxes. This was double the rate of the overall group, inwhich about one quarter of the REO sales were vacant or tax delinquent.

Preliminary analysis of foreclosure sales in Saint Louis County, Missouri, found properties with a foreclosure more likely to have had one or more foreclosures in the previous five years (Rogers and Winter2009). Increased risk of future foreclosures in properties and neighborhoods that are currently experiencing foreclosures and associated foreclosure sales will possibly impact the longer term

10

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

trajectory of the neighborhood, creating a continued cycle of negativeimpacts such as vacancy and depressed property prices.

Work by Li and Morrow-Jones (2010) attempted to better understandthe longer term impacts of foreclosure on neighborhood change. Using foreclosures that occurred between 1983 and 1989 in Cuyahoga County inOhio, they assessed longer term impacts evident between 1990 and 2000 in high-foreclosure neighborhoods. They found that foreclosures increased the proportion of black households, female-headed households, and households experiencing unemployment in a neighborhood(census tract). Unexpectedly, they also found that certain inner-city neighborhoods, shown as high foreclosure areas in the initial data, had experienced an increase in the median income of households in the neighborhood; while median income in the other high foreclosure neighborhoods had decreased. Li and Morrow posit the existence of two different types of neighborhoods: Type 1, where longer term changes included an increase in black, female-headed and unemployed householdsbut with an increased median income; and Type 2 neighborhoods with an increase in black, female-headed and unemployed households with an associated decline in the median income. They suggested redevelopment and gentrification in the 1990s in Type 1 neighborhoods the likely explanation for the increase in median income of these particular neighborhoods, even though the proportion of black female-headed and unemployed households increased. This suggests that Type 1 neighborhoods might have experienced an increase in inequality.

Li and Morrow-Jones note that who moves into the neighborhood after foreclosures impacts the direction the neighborhood takes. And, who decides to move into the neighborhood is directly affected by who initially buys the properties at foreclosure (investor-buyers, milker,5

rehabbers, flippers or holders, governments, lower income or higher income owner-occupants) and the sale process itself (length of time before sale, marketing of property, maintenance of property, etc.).

Costs to cities Foreclosures cost cities needed funds. Tax delinquency associated withforeclosures (negligent investor buyers, or abandoned properties) impacts the city funds that are available to flow back to the neighborhood to mitigate other negative impacts from foreclosure and influences the funds available to flow into community assets such as

5 A milker is an investor who buys a property, does not rehab it at all, and rents it out, milking the rent from the property without improving it at all. In other words, a milker is a slumlord Mallach, A. (2010). Meeting the Challenge of Distressed Property Investors in America's Neighborhoods. New York, LISC.

11

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

public schools. Moreover costs accrue to the city and taxpayers as a result of mitigating the negative impacts associated with foreclosure.A study in Boston attempted to document the dollar cost of foreclosure-induced vacant properties and associated increases in crime to the city; it pegged the dollar amount per property somewhere between $157,000 and $1 million (Simon 2011). A General Accounting Office (GAO) report from 2011 also documented the costs for cities andcommunities that have increasing numbers of vacant properties throughout the country (GAO 2011). For example, between 2009 and 2011 Detroit spent $20 million to destroy 4,000 vacant foreclosed properties. Recent news reports that cities are attempting to find ways to reclaim some of those costs.6

SummaryIn summary, foreclosures and particularly foreclosure sales impact community assets in several ways:

1. Neighborhood quality – neighborhood safety (rate of property and violent crime) and racial and socio-economic diversity reduces as crime increases and neighborhoods become either gentrified or more low-income. Indicators of social cohesion decline as measured by the visual landscape of the street.2. Housing prices – foreclosure sales diminish the collective value of housing and as a result impact the collective property tax resource base for the city. 3. Housing stock deterioration – the collective value of the physical housingstock in the neighborhood deteriorates as an increase in abandoned properties occurs. 4. Social capital – relationships between residents are interrupted as residents (owners and tenants) must leave the foreclosed buildings in order for a foreclosure sale to proceed. Buildings sit vacant for sometimes years with a smaller number of families living in the neighborhood, visiting businesses, and using neighborhood amenities. Trust deteriorates and civic participation declines.5. Fiscal costs – community and city financial resources are strained in managing the costs of mitigating the impacts of foreclosure sales.

Passing the Buck: Organized Irresponsibility and Risk Transfer

6 The City of Richmond is attempting to prevent the cost of future foreclosures by using eminent domain to purchase mortgages and write down the cost of the mortgage to the real value.

12

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Foreclosure sales offer an example of a system characterized by organized irresponsibility. Organized irresponsibility is the process when a system produces risks that cannot be tied back to any one organization or individual. Hannah Arendt describes this form of poweras the most “tyrannical” of all since no-one can be held accountable(Arendt 1998). Nobody is in charge! A number of scholars have pointed to organized irresponsibility emerging within different systems, particularly the environmental hazards emerging from industrial production (Alario 2000; Beck 1992, 2007; Crotty and Crane 2004). Sassen, without referring to the term organized irresponsibility, has documented how complicated forms of financial investment instruments, such as derivatives, create their own new level of risk resulting fromthe network of highly leveraged investments which are at the core of derivative products (Sassen 2009). But none have explored the process of how organized irresponsibility actually emerges within a system. This lack of conceptual clarity in understanding the mechanisms of organized irresponsibility provides few levers to develop policy.

Organizations are critical in the distribution of risk. Risk produced by an organization is often transferred away from that entitytowards another. Thus organizations “are both centres for processing and handling risks and potential producers and exporters of risk”(Hutter and Power 2005). Institutional contexts, social milieus and organizational cultures of risk-taking impact how organizations construct, perceive and manage risk (Hutter and Power 2005; Vaughan 1996). Individuals operating within organizations don’t always understand the risks they are undertaking, or how their actions will produce risk (Hutter and Power 2005) because they are isolated from understanding the full context of the organization, and also the system the organization is operating in (Vaughan 1996).

In any system or institution there are multiple entities as sitesof decisions about risk exposure and management. Risk is continuously being created, processed and moved around. Inevitably these risks accumulate in one place more than another and unintended and unforeseen consequences result. But there is often no one clear party to hold accountable when something goes wrong. And so emerges the concept of “organized irresponsibility”: the risks are nobody’s responsibility (Beck 1998).

Method and data As outlined earlier in the paper, two key questions guide this paper. Specifically, what about the structure of the mortgage finance market is driving foreclosure sales to create negative outcomes in

13

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

communities? And then, what can we do about it? The paper draws on research conducted for a larger study that focused on seeking to understand the systemic reasons for increased risk in neighborhoods asa result of foreclosure sales. The following section provides details on the methodological approach of the study, and the data used for this paper.

Institutional ethnography The data used in this paper was gathered using the methodological approach of institutional ethnography. As well as understanding the experiences of informants, institutional ethnography seeks to understand the complex set of social relations7 within an institution (in this case the foreclosure sales market), including economic and social relationships between stakeholders such as workers inside bureaucracies, professionals, and legislators. Institutional ethnographers locate themselves as having a principal interest in the structure of ruling relations of institutions. Ruling relations are those social relations in power that structure how institutions operate. At the same time, the methodology offers a practical understanding of how institutions and actors interlink, revealing the often unintended consequences of rules and regulations within institutions, making it an ideal approach to understanding ways policycan be effective (or not) (Carroll 2006). The purpose of institutionalethnography is not to generalize about a group of people, but instead to find and describe social processes that have generalizing effects (DeVault and McCoy 2006) (18). The larger study that this paper draws data from sought to understand the social relations of the housing finance system that created negative outcomes from foreclosure sales.

Data analysis: Between grounded theory and institutional ethnography Data for this paper was analyzed merging the approaches of grounded theory and institutional ethnography. Grounded theory offers a rigorous approach to qualitative research. Pioneered by Glaser and Strauss (1965), the defining elements of a grounded theory approach include: simultaneous involvement in data collection and analysis, constructing analytic codes and categories from data, using constant comparison during each stage of the analysis, advancing theory development during each step of data collection and analysis, memo-writing to elaborate categories, specify relationships and identify gaps, theoretical sampling, and completion of the literature review

7 Social relations are the set of structural power relationships between organizations and individuals within a social system. See Smith, D. (2005) fora more in depth discussion.

14

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

after developing an independent analysis (Charmaz 2006) (5-6). Grounded theory is well suited to institutional ethnography according to Dorothy Smith, who developed the concept of institutional ethnography in the 1980s and who notes that analysis should be concurrent with data collection to follow trails and markers from interviews and observations that will allow data and fact checking andgive the researcher an increasingly in-depth and complete picture of institutional relations (Smith 2006).

I modified this grounded theory approach to meld with the approach of institutional ethnography. Before beginning to code in Nvivo (the qualitative software package used for this research), I diagrammed the organizations, decisions and social relations involved in each sales process on a large piece of paper along with their relationship to the neighborhood.8 While drawing this map, I wrote memos to articulate different patterns observed in the different sales. With this map established as my basis for understanding the complex set of social relations described in the data, I began to codethe first few interviews in Nvivo using a grounded theory approach, starting with full coding of the entire interview to develop emergent codes. I then used Nvivo to develop out key framing codes which included organizational entities, relationships of power, the different sales, discussions of neighborhood, and discussions of risk.Within each of these codes I drew in the emergent codes and developed out more code categories to deepen the analysis. As the coding progressed, I cycled between coding and memoing within the qualitativesoftware package Nvivo (di Gregorio 2003).

Data sources The data used for this paper was drawn from a wide variety of sources between the period January 2009 and December 2011, including: interviews, observations, textual analyses, Boston sales data, and industry organizational data. A total of 47 interviews were conducted.These included interviews with 26 real estate agents, three real estate lawyers, three foreclosure auctioneers (and an additional threeconversations with auctioneers in the field), four investors, five owner-occupant buyers interested in foreclosures, one non-profit staffperson, and two servicer employees. Other sources of information

8 Institutional ethnographers still lack an appropriate software to provide this level of mapping for their data analysis. I have since discovered Prezi to be a useful tool. However, at the time of initial mapping I was not aware of this software’s potential to be used in this way. Nvivo’s mapping section is limited and not useful for the kind of detail necessary in the mapping endeavor.

15

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

reviewed and analyzed included: short sale, auction and REO sales contracts, marketing materials for foreclosure sales, Multiple ListingService (MLS)9 listings for foreclosure sales, and training materials for real estate agents in general and specifically for foreclosure sales. Field observations were conducted of eight foreclosure auctions, the daily work of an REO real estate agent and three City ofBoston “Buying a Foreclosed Property” classes, and an online training provided for real estate agents on short sales by the National Association of Realtors.

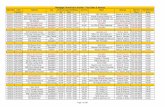

Quantitative data was purchased and examined for all foreclosure petitions in Jamaica Plain and Dorchester zip codes for 2008 supplemented by pulling a sample of 150 petitions to examine subsequent sales data, specifically, whether investors purchased the property and how many times the property was sold after the auction. Data were also collated and analyzed from industry publications such as Inside Mortgage Finance to provide context (scale and business volumes) for each of the different types of organizations involved in the foreclosure sales process. Table 1 summarizes the data drawn on inthis study.

Table 1: Data sources

Type of Data

Type of Foreclosure Sale

Data Sources GeographicRelevance

Interviews REOAuctionShort sale

Real estate agentsAuctioneersLawyersBuyers (investors and owner-occupant)Non-profit employeeMortgage lenderServicer employee

Boston

Sales data REOAuctions

Warren Group dataCity of Boston Foreclosure report data

Dorchesterand Jamaica Plain

Observation REO Auction sales Greater 9 Multiple Listing Service (MLS) is a real estate advertising and marketing company. It provides an online database of all property for sale by real estate agents in the United States. It also includes information about past sales of properties.

16

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

AuctionShort Sale

REO property managementProperty open housesCity of Boston classes

BostonDorchester, JPBoston

Real EstateAgent training materials

REOShort Sale

Online Short Sale trainingReal Estate Agent training materialsForeclosure Sale training material

MassachusettsNational

Sales documents

REOAuctionShort Sale

REO Purchase and Sale contract

Auction sale contract

Short sale Purchase and Sale and Offer contracts

MLS listings

Auction websites and brochures

DorchesterJamaica Plain

Inside Mortgage Finance Data

Servicer industryWall Street InvestorsTrustees

Annual statistics National

Census Bureau data2010

Neighborhood data

Housing Vacancy rates Census tractNational

The approach of drawing on multiple sources of data provided a rich and multi-faceted way to understand foreclosure sales. In collecting data, standard sociological practices for ethnographic observation (Maanen 1988; Emerson, Fretz et al. 1995; Preissle and Grant 2004; Lofland, Snow et al. 2006) and in conducting semi-structured recorded interviews (Weiss 1994; Corbin and Morse 2003; Warren, Barnes-Brus et al. 2003) were drawn upon.

17

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

BostonTwo neighborhoods in Boston were used to explore how foreclosure salesare sold and to look at the ways that organizations interact in the sales process. The goal was to reveal the social processes and relations that structure the sales process, in order to give insights,both theoretical and policy related, into the real potential for socially undesirable outcomes to occur at the neighborhood level as a result of these particular sales.

Boston and specifically two neighborhoods in the city – Jamaica Plain and Dorchester – were selected as the site for this study for mostly practical reasons, related to access and the author’s existing relationships with key stakeholders. Previous research conducted in Boston by the author also provided an additional important perspectiveon the problem of foreclosure sales.

Theoretically Boston is an interesting city for study. It is located on the east coast of the U.S. Its 2010 population was 617, 594, having grown 4.8 percent since 2000. Fifty-three percent of the city’s population is non-white, making it a majority-minority city. The greater Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), a larger spatial entity that incorporates the surrounding counties including two New Hampshire counties, is 4.55 million, growing 3.67 percent from2000. This study will refer to the City of Boston rather than the MSA unless otherwise noted. Boston’s housing market is characteristic of a “hot” or desirable location, and yet this is despite experiencing urban industrial decline in the 1970s, characteristic of “old industrial cities,” like Pittsburg, Detroit and Philadelphia. Boston’scity-wide foreclosure rate of 0.4 percent, is low compared with some of these same old industrial cities, including Detroit’s at 1.5 percent (Realty Trac) and New Haven’s at 0.6 percent.

Boston has a recent history of large numbers of foreclosure sales, having seen a peak of foreclosure activity in the savings and loans crisis in the 1990s. The 1990s saw foreclosures and foreclosure sales dramatically increase to higher absolute numbers than currently documented.

In the most recent foreclosure crisis, foreclosures and foreclosure sales started to increase during 2005, rapidly reaching a peak in 2008, and bumping up and down between 2009 and 2010, mostly inresponse to systemic policy-related challenges to the foreclosure process, e.g., the Ibanez decision and robo-signing (see page 17 for details of these cases). The chart below, taken from the “City of Boston Foreclosure Trends” report, provides a graphic representation

18

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

of the current foreclosure crisis in Boston compared with the last foreclosure crisis in 1992.

Foreclosure deeds (completed foreclosure auctions) are predominantly located in the city neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan, East Boston and Hyde Park. These are neighborhoods that are lower-income than other parts of the city and with higher percentages of immigrants, African-Americans, Latinos and Asian-Americans. These neighborhoods also received a disproportionate share of subprime mortgages (Campen 2007) and were historically redlined in the mid-twentieth century. The city has designated certainareas of these neighborhoods as foreclosure hot spots with targeted investment and rehabilitation activity. The target hot spots are focused on streets with increased crime and concentrated foreclosures.10

Figure 2: Foreclosure deeds11 in Boston 1990 – 2011

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

1800

Source: City of Boston Foreclosure Trends report 2009.

Figure 3 shows the cumulative distribution of foreclosure deeds by census tract between 2000 and 2010. Clear clustering can be seen in10 http://www.cityofboston.gov/news/default.aspx?id=4206 11 Foreclosure deeds are completed foreclosure auctions where a lender has sold the property at auction and a completed foreclosure deed is recorded in the registry of deeds.

19

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan in census tracts with a low percentage of white families – in other words, in neighborhoods of color. These neighborhoods experienced foreclosures during 2005-2006 at the very start of the foreclosure crisis, before other parts of thecity saw any increased foreclosure activity. They have also seen the greatest drops in house prices (Department of Neighborhood DevelopmentCity of Boston 2010). These neighborhoods rank in the top twenty zip codes in Massachusetts with the highest proportion of housing units inforeclosure. The experience of these high foreclosure neighborhoods isin stark contrast with that of low foreclosure neighborhoods in Boston.

20

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Figure 3: Cumulative foreclosure rate by census tract between 2000 and2010, City of Boston

Source: Warren Group Foreclosure Data provided by the Research Department, Department of Neighborhood Development, The City of Boston; US Census Data race by census tract Table Summary File 1 DP-1 2010 Census data.

ASSET MANAGEMENT AND LOSS MITIGATION PRACTICES THAT CREATE MARKET DISTORTIONS AND NEGATIVE NEIGHBORHOOD OUTCOMES

Before diving into the asset management and loss mitigation practices that create market distortions and negative neighborhood outcomes, I want to provide a brief flavor of how the foreclosure sales process unfolds. The first part of this section of the paper will review the foreclosure auction and the

21

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

REO sale. Then I will go on to review the specific practices thatcreate problems in the neighborhood.

Foreclosure sale process In each of the different types of foreclosure sales - short sale,auction, and REO sale -certain practices established by the mortgage servicer and by the real estate agent influenced the neighborhood’s community assets. These sales practices limit the pool of buyers, leading to preferences for investors, and lower sales prices while increasing the likelihood of vacancy in the property. The following section will review sales practices at foreclosure auctions and in REO sales, describing the ways that these sales practices can cause a loss of community assets.

Auction sales practices It is a cold, sunny day in Boston. Standing outside the house I watch as three men walk over to the lady auctioneer standing on thesidewalk outside the house everyone assumes is up for auction. Theyjoke and chat with one another as they sign up on her clipboard to participate in the auction. Two of the men, both in their mid-thirties, walk over to the front door of the house. The one with short cropped hair, in a dark jacket and jeans, takes a small flashlight and shines it in through the little window at the top ofthe door, straining on tiptoes to peer in. The second man walks down the steps to the side of the house to look at the electric meter. One of the other bidders, I do not catch who, asks which house is up for auction. The auctioneer clarifies that it is the house on the left. The other bidders start to mutter amongst themselves, obviously confused by this clarification since the listing shows a basement apartment that was clearly non-existent from looking at the house.

“You and Frank together today then,” the auctioneer says to one of the men milling around on the sidewalk. Then she quietly starts reading the deed of the property while standing on the sidewalk. She reads it very quickly out loud and I can’t understand what she is saying. An older man with a beard silently scans another document on his clipboard while she talks. The other men, all of them white, and in their 30s, three of them—one of them has dark sunglasses and short, gelled, dark blonde hair—mill around on the sidewalk, not completely listening, but they look like they are waiting for something, pacing around, turning in small circles. A black man with a cell phone and a hands-free ear piece gets out of a car that has just pulled up to the sidewalk while the auctioneer

22

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

continues to read the deed. He asks the white man with the sunglasses which property is being auctioned.

The woman auctioneer stops reading the deed and says “it goes on and on, and oh guess what I have…a municipal lien. March 29th $801 and 36 cents. I don’t know about condo association.” One man asks about this, but a bus drives by and I can’t hear the next minute. She says, “No questions? You guys know what you are doing.” And shemockingly remarks about how they will all drive away as soon as it is over. The men then move in tightly, huddling around her. She makes the opening bid, and the man with the blonde hair and dark glasses says “$330,000.” Then she says, “Going once, going twice, sold.” It takes maybe one minute. She stands close with the beardedman muttering with him and periodically calling him the bank. All of the men, except for the guy with blonde hair and dark glasses, walk away quickly back to their cars and drive off. The auctioneer,“the bank” and the highest bidder gather around the hood of the auctioneer’s car, signing paperwork. Five minutes later, the streetis empty again.”

Field Notes from a Dorchester Auction December 2009

The description of a foreclosure auction in Dorchester highlightsthe fast pace of the event, the insider knowledge of regular investor bidders, and the lack of transparency in the sale. Potential buyers cannot see inside the property. Listings and descriptions of the property may be inaccurate or misleading. A buyer must decide within a few minutes whether they will put in abid. Investors interviewed for this study described the extensivebackground work they conducted prior to the auction that allowed them to make such a snap decision. They also knew that if they bought the property and it turned out to be a dud, it was part ofa portfolio strategy that could absorb one or two failed properties. All of these qualities create a scenario that is intimidating for any newcomer especially a homeowner looking to purchase a low-priced property.

The foreclosure auction sale is not just intimidating, it isalso risky. Making a purchase at an auction is high-risk for the

23

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

buyer due to a number of clauses hidden in the paperwork of the auction sale and the parameters of the sale set by the mortgage servicer. These include: a deposit requirement, liability for thedifference in price between the first and second bidders at the auction, the “as is” clause, inability to see inside the property, a very short closing period, establishment of a price floor, and the forcing of seller (servicer provided) title insurance.

These strategies all reduce the risk of the servicer incurring additional costs that might eat into any returns gainedfrom the auction. Consequently, these strategies limit the pool of buyers at the auction sale to predominantly regular investors who can absorb that risk, and as a result it reduces the price and the likelihood that the property will be sold at auction. Ralph, an investor and auctioneer, described to me the kinds of risks involved in buying at an auction:

RALPH: I personally have been in a situation where the first time I ever bought a house at foreclosure…I was the high bidder, and I bid up…I couldn’tget the bank in there ‘cause I need to get an appraisal. The bank had to send the appraiser. People would not let the appraiser in. It took me three months. Every time I got an extension beyond the month, the bank charged me another $5,000. If I’d backed out, I would be losing 15 grand at that point,instead of five. So it takes nerves of steel, I think. And it’s not for the faint at heart…(emphasisadded). ‘Cause I’ve seen more than my fair share of houses…sold at auctions.People don’t know. It’s like a grab bag. You buy it and you look inside to see what you got. And when you finally get inside, you don’t want it. All the piping has been removed or the heating system. Or the sink has been running for the past three weeks, and now there’s mold. And all these kinds of crazy things, unexpected things that happen. And it just costs lots of money.

Consequently the risk is very high that the property will end up either as an REO property or investor-owned. These two outcomes lead to higher risks for vacant properties in the neighborhood as REO properties are usually vacant for a period, sometimes years, and investor-buyers of foreclosed properties tend to have higher incidences of vacancy (Immergluck 2011). Investor-buyers are also more likely to be problem landlords and to be delinquent on taxes (Coulton, Schramm et al. 2010).

24

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

The sales practices at the foreclosure auction limit the number and type of potential buyers to mainly investor buyers, limits the potential price that may be garnered for the property,and increases the likelihood that the property will become a vacant bank-owned or REO property.

REO propertiesProfessionals like Ralph, working with foreclosure auctions, describe them as the riskiest deal of all foreclosure sales. Bank-owned sales are considered less risky and easier for the buyer to purchase. Homebuyers perceive this difference too, strongly preferring REO sales to buying at an auction. This does not mean that REO sales are not without higher levels of risk than a normal home sale. Bank-owned sales (REO or real estate owned sales) are those in which the servicer that has bought the property at the auction (essentially paying themselves money to close out the mortgage)12 now wants to sell the property. The advantage for the buyer of a bank-owned sale over a foreclosure auction is that the servicer has paid off all of the outstanding mortgage liens on the property. Thus the title of a bank-owned property is usually clearer than at a foreclosure auction, where the highest bidder must cover all outstanding liens on the property e.g., water bills, tax bills, etc. Buyers can also get inside REO properties to view them and see what they are buying. However, recent fiascos in the foreclosure process revealed in USBank vs. Ibanez and the robo-signing scandal (see page 17 for a detailed description of these cases) still make buying an REO property a risky proposition. Challenges to title from servicer mistakes can invalidate REO sales years down the line and the automated nature of the process in large servicers makes these mistakes more likely.

Once a property becomes bank-owned, the servicer moves the property from the loss mitigation department to the asset management department and assigns it an asset manager. The asset manager’s goal is to sell the property as quickly and for as much12 One investor noted that she is seeing more cases of the bank buying the property back at “full debt” where the opening bid is the full amount of the debt owed to the bank. She surmised that this has been since the bail-out where the bank may be able to write off losses incurred at the foreclosure auction and gain some benefit through the bail-out.

25

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

money as possible. Many servicers, or lenders, in the 2007-ongoing foreclosure crisis are contracted with third party asset management companies to manage the process of disposing of REO properties. This has the added advantage of reducing liability exposure for the servicer by having an entity that is now responsible for managing the property and any liability suits that might come up, for example, a tenant who sues as a result ofan injury obtained from a damaged part of the property. Asset management third party entities also allow the servicer to quickly add capacity.13 Third party standards appear to be low-quality, as evidenced by complaints made by Fannie Mae representatives in a Senate Committee hearing in 2010. Whether itis the servicer or the third party, the representative asset manager contracts with a real estate agent to manage and maintainthe property until it is listed for sale.

By the time the property has moved into and through the REO process, the foreclosure could have taken up to four years (oftenas a result of mistakes in the foreclosure process). The REO property is sold in two ways that increase the risk for the neighborhood. The first is the servicer prefers that the propertyis sold empty and so tenants of the building are offered cash-for-keys to leave the property. For the servicer a vacant property is less of a risk. A vacant property reduces complications for the sale of a property as many institutional buyers prefer vacant properties. Tenants also mean liability, forexample if a tenant breaks a leg on a broken stair. But this leaves the property vacant and susceptible to all the associated problems such as an increase in crime and property deterioration.The second factor that increases risk for the neighborhood is themultitude of requirements in the contract and sales process that make it a risky prospect for an individual owner-occupant or small time investor buyer. The property is thus more likely to end up in the hands of a larger investor. While this is not necessarily always a bad outcome for the neighborhood, there is

13 The web-page for one asset management company, Bank Asset Management REO, states : “Outsourcing of asset management can measurably reduce days in inventory through strict timeline management, ensure high recovery rates versus valuation benchmarks, insulate the seller from third party claims, and provide for temporary or permanent staffing reductions while utilizing the skills and experience of highly trained real estate brokers.” www.bamreo.com Accessed February 9, 2011

26

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

the risk that the investor is an irresponsible landlord14 in the neighborhood. Investors have strategies that are not always in the best interests of the neighborhood and the aggregate impact of large numbers of investors buying in a neighborhood can lead to problems such as the concentration of low-income households orlow-quality properties.15

These issues for the neighborhood are exacerbated when mistakes are made in the foreclosure process by the servicer. Theresult can be that the foreclosure sale process takes many years to resolve and the chances are much higher that the property is vacant during that time.

Transferring risks to the buyer leads to reduced demand for foreclosed propertiesAs illustrated in the description of the auction and REO

sales, in a foreclosure sale, risk is transferred very explicitlytowards the buyer. In a normal property sale the buyer has some negotiating capacity to ensure that the risks of the sale (no sale occurring, over or under-paying, additional closing costs, problems with the title, problems with the property) are shared between the buyer and seller. However, in foreclosure sales, the buyer is responsible for many of the risks of the property by thestructure of the sales contract and the sales process and practice. The exception to this rule is when the servicer pays off outstanding liens at the auction, making the REO sale less risky for the buyer with regards to liens; however the title can still be problematic because of mistakes and sloppy practice by the servicer as was seen in the Ibanez case and the robo-signing scandal. The following table describes the risks that are transferred from the seller to the buyer in a foreclosure sale, particularly an auction or REO sale.

Table 2: Risks transferred from seller to buyer

Risks transferred from seller to buyer

Impact for buyerif risk realized

Type of sale

14 By irresponsible landlord I mean that they do not maintain the buildings well, charge inflated rents, and are non-responsive to neighbor complaints with their property or tenants. 15 For example, one investor interviewed described a strategy of purchasing foreclosed properties to hold as Section 8 rentals until the market improved at which point they would sell the properties for a substantial profit.

27

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Needed property repairs

Cash or financing neededfor investment

Short saleAuctionREO sale

Compliance with building code

Cash or financing

Short saleAuctionREO sale

Title issues Cash and legal help

AuctionREO sale

Liens against property

Cash and potentially legal help

Auction

Tenants Legal help and time

AuctionREO sale

Damage to property during sale process

Insurance needed= cash impact

AuctionREO sale

Preference for cash vs financing

Reduces likelihood of purchasing REO property

AuctionREO sale

Losing deposit Cash impact AuctionREO sale

Responsible for difference between highest and next highest bid

Cash impact Auction

Deal takes longer toclose than 30 days –fines imposed

Cash impact AuctionREO sale

Losing out on betterproperty

Potential financial cost

Auction

Source: Table developed by author. May 2012.

Part of this strategy of risk transfer to the buyer is the goal of servicer risk deflection to ensure the smallest financiallosses possible. Three key outcomes result: (1) investors buy foreclosed properties more of the time than owner-occupants because they are more able to absorb the financial risks that a servicer deflects, (2) foreclosure sales prices are lower than regular home sales depressing real estate prices in the

28

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

neighborhood; and (3) a property is more likely to be vacant (both as a result of sales practice and as a result of subsequentinvestor-buyer actions).

Asset management and loss mitigation practices that cause problems for the neighborhoodThis paper does not allow for a review of all the data showing the asset management and loss mitigation practices that cause problems for the neighborhood, however here is a summary of the servicer practices that increase the likelihood that a property will end up with an artificially low sales price, investor owned,vacant and falling into disrepair.

(1) Preference for vacant properties – mortgage servicers prefer that a property that they are managing is vacant. This allows them to reduce the risks associated with having tenants.

(2) Onerous sales contracts – the auction sales contract is particularly risk for any buyer. It requires a buyer to takemost, if not all, the financial costs associated with backing out of the sale, even though the buyer is usually not able to see the inside of the property before buying. The REO sale has a sales contract that requires sellers title insurance, has few protections for the buyer and does not allow for negotiation.

(3) Marketing practices (targeted buyer lists, lack of open houses and staging, lock boxes) – REO realtors target investor buyers to ensure the highest likelihood of sale, they conduct no open houses, and set up lock boxes for otherrealtors to show the property. This is markedly different from how most regular sales go forward.

(4) Preference for cash-buyers – the mortgage servicer prefers cash-buyers because there are not the requirements set by the buyer’s mortgage contract that might derail the sale.

(5) Selective investments in REO properties – mortgage servicers appear to make decisions based on REO realtor’s recommendations about whether to repair or invest in a property e.g. install a new kitchen or bathroom.

(6) Length of time for short sale – the length of time that it takes the loss mitigation department to respond to a request

29

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

for a short sale often leads to the selling realtor losing potential buyers who need a response more quickly.

(7) Lack of responsiveness in price negotiation at auction – for some large servicers, even though the highest bid is just a few thousand less than the required minimum that the servicer will accept, the servicer will still refuse that bid and move the property into REO status increasing the time the property is in limbo and increasing the likelihood the property will become vacant.

(8) Limited realtor payments – limited realtor payments for eachREO management activity means that realtors are operating onefficiencies and not finding incentives to go above and beyond in their work. They are motivated to get the quickestturnaround for the property which is usually from an investor who has purchased an REO before.

(9) Controlled list of tasks for realtor – With a controlled list of assigned tasks for the REO realtor to do, there is limited room for creativity and personal relationships. This is the emotional work that many realtors talk about being a critical part of why they enjoy their job. Several realtors that I spoke with refused to do REO sales because of this. One REO realtor talked about the lack of “puppies and flowers” in the REO sales business and suggested there were very specific types of “money oriented” realtors who were selling REOs. This impacts which clients are attracted to the sales.

These sales practices lead to intermediary impacts seen in Bostonforeclosure sales, such as an increased risk for investor buyers or a higher likelihood of vacancy. The intermediary impacts causea loss of community assets—a decrease in neighborhood safety froman increase in crime, neighborhood environment quality16 decline,

16 Neighborhood environment quality is measured through the aesthetic impact of the neighborhood. The quality would be measured through the quality of the housing stock (abandoned, vacant, boarded up or inhabited and cared for buildings), people on the street, trash and litter prevalence. These are all indicators of social decay. Jane Jacobs has written extensively about the impact that the visual experience can have on a neighborhood, and the crime sociology literature refers to such indicators as signaling the level of social cohesion on a street.

30

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

a decrease in neighborhood diversity through either concentrationof low-income families or gentrification, and a disruption in neighborhood relationships from evicted owners and tenants reducing social capital.

Table 3 describes in more detail some of the outcomes from the sales process, the mechanisms through which these risks are transferred, the specific part of the sales process causing the problem and the type of sale that this problem is seen in. The risk that there will be negative impacts from a foreclosure sale increases along a continuum of related potential points of sale of the property from the short sale through to the REO sale. At the point of the short sale, there is the potential to avoid manyof the neighborhood risks, such as vacancy. A successful short sale will mean that there is the shortest possible time for vacancy in the entire process. If the short sale is not approved,then the highest risk sale of all proceeds—the foreclosure auction. The auction increases the likelihood that the property will be vacated and increases dramatically the risk that the property will be purchased by an investor. At the auction, the property also has a good chance of ending up as an REO sale whichwill extend the vacancy period, increasing the risks for the buyer in the sale and as a result boosts the likelihood that an investor will purchase it. By the point of the REO sale, the property will be in servicer management the longest and the risksfor property deterioration also multiply, though from real estateagent and servicer reports this does appear to depend on the neighborhood.

Table 3: Risks transferred to the neighborhood from the foreclosure sales process

Outcome from sales process

Mechanism Sales process Type of sale

Investors advantage in sales process over owner-occupants – more able to absorb risk

Financial risks to buyer

Bank preference for cash buyers =investors

“As is” clauseTitle insurance

Buying sight unseen (auction)

Marketing to

REO saleAuction

31

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

- access to cash/financing with fewer ties

Information distribution networks to investors

investors

Vacant houses Tenants removed from bank-owned properties

Preference of real estate agentand servicer: selling houses empty

Reduced risk for law-suits from tenants

REO sale

Abandoned houses

Unclear title Undue foreclosureprocess

REO sales

Investors more active

Deal falls through

Length of time for response fromservicer

Short sale

Lower sales prices

Reduces potentialbuyers (fewer buyers interestedin “fixer-uppers”)

Buyer investment needed to improveproperty

Little maintenance or investment by servicer in some neighborhoods

Onerous and riskycontract and process for buyer(“as is,” sight unseen)

Challenging and lengthy sales process

AuctionREO saleShort sale

Source: Table developed by author. May 2012.

Mistakes in the foreclosure process mean abandoned foreclosed properties Not only does the intentional process of foreclosure sales

increase risks for the buyer but unintentional mistakes cause problems that compound the community asset loss seen in

32

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

concentrated foreclosure sales. During the course of two years offieldwork I witnessed two major cases of what have been termed “foreclosure fiascos” (Engel 2011) that led to increased rates ofabandoned foreclosed buildings around the neighborhoods of Boston. The first is generally termed “the Ibanez decision.” Thisbegan when the assignment of the mortgage, necessary for the servicer to foreclose on the property, had been conducted after the foreclosure began. Judge Long, in the Massachusetts judiciary, ruled that this was illegal and that the foreclosure must be correctly conducted, which invalidated the foreclosure and subsequent sale. As a result of this ruling, thousands of properties (we do not have good estimates of the numbers) in Massachusetts were thrown into a state of legal limbo and responsibility and ownership reverted to the original owner who lost the property in the foreclosure. However, most of these owners were not still living in the property and were not notified of their new responsibilities. The servicer had to submit a new and correct foreclosure after correctly assigning the mortgage. This process took years in some cases, and many of the 2008 foreclosures affected by this ruling sat vacant until 2011. Still by 2012 some of these properties have not been resold. These vacant properties are costly to the neighborhood, leading to an increase in vacancies, and as a result an increase in opportunity for crimes. Neighborhood property values also decrease further impacting neighbors who are not in foreclosure.

The second case that occurred during my fieldwork was the “robo-signing” scandal where it appeared that hundreds of thousands if not millions of foreclosure documents had been illegally signed by workers at signature factories instead of thevice-presidents of the foreclosing servicer as required by the law. When this came to light in judicial foreclosure states, Bankof America was forced to suspend foreclosures across the country to assess their foreclosure processes to ensure that this did nothappen again. Non-judicial foreclosure states such as Massachusetts were unable to assess the extent of the issue, and are still unable to assess and contest the validity of signaturesin the foreclosure documents. For the foreclosure sales market, this ruling had an impact in that it slowed the foreclosure process down as well as gumming up the resulting inventory of foreclosed properties. It did not however, directly impact the

33

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

foreclosure sale process itself other than extending the time forpossible short sales and impacting the capacity of servicers responding to the issue.

WHY DOES THE MORTGAGE SERVICER BEHAVE IN WAYS THAT MAY NEGATIVELY IMPACT THEIR CLIENT – THE TRUSTEE AND MBS INVESTORS?

To understand why the mortgage servicer behaves in the ways that it does, we need to have a more in-depth understanding of the organizational ecology of the housing credit market as it relates to foreclosure sales. Figure XX (page XX) provides a visual representation of the relationships between each stakeholder and the geographical nature of the entity itself.

Table 9 on the following page provides a more detailed overview of the types of relationships between the different entities that makeup the housing credit market involved in foreclosure sales. For the purposes of understanding the larger groupings, industry group refers to the nexus of related entities. The Servicer industry group includesthe servicer and all of its third party contractors, and the Trustee industry group includes the Trustee and the investors that the Trusteerepresents. Particularly note-worthy is the geographical nature of each organization, which moves from the investors being international in actual location and in orientation, to the REO real estate agents who are generally local though possibly regional. Government is an important stakeholder in the housing credit market that structures howthe housing credit market unfolds and is discussed later in this section of the paper.

Table 9: Groups/organizations making up the housing credit market in foreclosure sales

Organization Industry Group Geography RelationshipsInvestor Investor International/

nationalBuys Trustee tranche

Trustee Investor International/national

Pools mortgagesContract with servicer

Servicer Servicer National Contract with TrusteeContracts with third party

34

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

entitiesLoss mitigationcompany

Servicer – third party

National Contracts with servicer

Asset management company

Servicer – third party

National Contracts with servicer

Law Firm Servicer – third party

State-wide/regional

Contracts with servicer

Auctioneer Servicer – third party

Regional Contracts with servicer

REO real estateagent

Servicer – third or fourth party

Local/regional Contracts with servicer or asset management co.

Source: Developed by the Author. May 2012.

While Table 9 provides detail on most of the groups and organizations making up the housing credit market, there are permutations and variations. For example, some REO real estate agents work in groups asproperty management companies. I have not included these variations since they can be considered as variations on the main category included here.

Figure XX: The social relations of the foreclosure sales market organizations

35

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood

Source: Developed by Author. May 2012.

Global Financial Investors and “the Trustee”When a mortgage is originated it is usually packaged together

with other mortgages into a Trust. The Trust then sells the rights to the income from the mortgages to investors. The Trust establishes a set of rules, or a contract, up front, which determines how the Trust will operate and who it will contract with to manage the mortgage income, an arrangement that allows the Trust to remain tax neutral through something known as “passive management.” Passive management isan Internal Revenue Service (IRS) designation that requires the Trustee to not make any decisions about how the mortgages and income

36

H. Thomas – Foreclosing on the neighborhood