Leon Battista Alberti and His Somniatic Troubles - DSpace@MIT

Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

Transcript of Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���4 | doi ��.��63/9789004�67848_���

Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition*

Petra M. Sijpesteijn

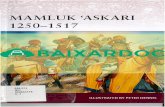

As Mark Cohen pointed out in his monumental study on letters written by or on behalf of the Jewish poor in Fatimid and Ayyubid Egypt, the formulae in those documents requesting help and relief from financial pressures fol-low closely those attested in Arabic petitions of a more general nature “to a ruler or other dignitary requesting redress of a grievance or some kind of assistance.”1 The document that is the subject of this paper is exactly such an Arabic petition. It is addressed by a certain ḥajj Aḥmad al-Adamī to the chief Shāfiʿī judge of Cairo requesting that an ongoing financial conflict between the petitioner and some creditors, which has caused Aḥmad’s repeated imprisonment, be looked into by the Shāfiʿī court. Below follows the edi-tion of the petition followed by a commentary and discussion of some of the issues raised by this text.

The petition is now kept in the University of Utah papyrus collection under inventory number UU 1286.2 Professor Aziz Suriyal Atiya compiled the col-lection, which he and his wife purchased over a period of several years from dealers in Egypt, Beirut, and London. While most documents are from Egypt,

* I would like to thank especially Jo van Steenbergen and Yossi Rapoport for their valuable com-ments on the reading and interpretation of this document, and Geoffrey Khan and Christian Müller for their remarks concerning the edition. I would also like to acknowledge the work of Roy Bernabela who presented his preliminary edition of this document in the context of a master’s seminar at Leiden University. Any remaining mistakes are of course my own. In this article the following abbreviations are used: CPR XXI = Corpus Papyrorum Raineri XXI, Gladys Frantz-Murphy, ed., Arabic Agricultural Leases and Tax Receipts from Egypt 148–427 A.H./ 765–1035 A.D. (Vienna: Brüder Hollinek, 2001); P.Heid.Arab. II = Werner Diem, ed., Arabische Briefe auf Papyrus und Papier aus der Heidelberger Papyrus–Sammlung (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1991); P.Vente = Yūsuf Rāġib, ed., Actes de vente d’esclaves et d’animaux d’Égypte médiévale I (Cahier des Annales Islamologiques 23) (Cairo: IFAO, 2002); P.Vind.Arab. III = Werner Diem, ed., Arabische amtliche Briefe des 10. bis 16. Jahrhunderts aus der Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Wien (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1996).

1 Mark R. Cohen, Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 175.

2 I am grateful to Luise Poulton, Manager of the Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, for her help in obtaining so quickly and smoothly the image of this paper document and the permission to publish it in this publication.

353Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

Figu

re �

Mam

luk p

etiti

on fr

om a

n in

debt

ed p

rison

er to

the c

hief

Shā

fiʿī q

āḍī o

f Cai

ro. A

rabi

c Pap

er U

U 12

86 r

& v

© R

are B

ooks

Div

ision

, Spe

cial

Col

lect

ions

, J. W

illar

d M

arrio

tt Li

brar

y, Th

e Uni

vers

ity o

f Uta

h.

354 sijpesteijn

nothing is otherwise known about their provenance.3 Although undated, based on the formulae and layout of the document, it should probably be dated to the Mamluk period and a comparison with documents from Egypt suggests a prov-enance from that region.4 The petition is written on a fine piece of yellowish paper in black ink. The paper shows three vertical and three horizontal folds, presumably caused when the letter was folded and sent. The paper is stained in some places and there are a few holes and tears that have damaged the text in two places (top left corner and bottom middle). Diacritical dots are writ-ten in some places and the shīn is indicated with three dots above it. On the verso two lines are written, a name and a line of individual, unligatured Arabic letters. The relationship between these two lines and the text on the recto remains unclear.

Text

Recto

�لر�ح�يم و�هو�ح��س�ب�ي �لرح�م��ب ا �ل��ل�ه ا �ب���م ا 1> ب�مي���� �ي >و��س���ش ]�ـ�ا ـ� �ل����ي����سب �ي ا

��ب �ب�ا ��ي�ا �ب�ا و�مولا ��ي ��س����مي�د �ب��ي�ب �ي�دب

ر�� لا �مب�ل ا�ي����ي 2

و]د[ �ل��ل�ه �بو�حب ع ام �م�مي ع�لا لا �ل�ع��ل�م�ا ا م و�م��ل�ك ا ��س�لا لا �ي�ب ا �ا �م��سش 3

م �ل��س�لا �ي وا �ل���م�لا �ل ا ��ب���مب �مر�ي محمد ع�����ي�ه ا �ي ربر� ��ب م و�ح���ش �ب�ا لا ا 4

�م�����ي�ه �ي �م�ع�ا��ي ��ب ع��ل� �ب�ا ل و��س��ب و �ع�مي�ا

ل ودب �ل���ا ��ير ا�ل ��ب����ي �ب�ه ر�ب �ه� ا و��ي��ب 5

�ير ولا �م��ط�����ب و . . . . . . . . ا �ل��مي��� �ل�ه رب �ل��ش�هي و �ل��ش�ا � ا �ي��ي�ب و�ه�دب �مر 6�لر�ح�يم�هي ط���ب ا �ل�عوا �ل�ع���م�مي���م�هي وا �ي ا ��ي�ا �ل���م�د �ل�ه �م��ب ا . . . و��سوا 7

�ب �بم����ح�ك�م�هي �ل��بوا ��د ا ����ب�ع�ه لا �� ود �ل��ل�ه �ي�ع�ا �ه ا �ل�ه �لو�ب �ي ��ار ��ب

�ل��ب���ب ا 8��ي�هي ر�ع�ي �م�د �ل���ش �ه ا �لو�ب �ل�ه ع��ل� ا �ي ��ا

ر ��ب �ل�مي��ب���ب

�ع�مي�هي����ب �ا �ل��سش �ي ا د �ل��س�ا ا 9

�هي ر�ي����ب�ل���ش لم����ح�ك�م�هي ا �ي ا

ع�ا ��ب �ل�د �ي�ه وا]. . [�م�ا ا �ب�ا �ل�د �ح��س�ا ع�����ي�ه وا 10�م��ي�ب �������ا و�لر�م����ا ا �������ا و�ب��ب �ل��ل�ه و�ع��طب ���ا ا

ر���ب ���ش 11�ل�ك ا �ه� دب

��ب ا 12

In the right margin��ي���م�هي

لمم���وك ا

م�ي د لا ح�م�د ا �ل���ا�ب ا ا

3 See http://content.lib.utah.edu/cdm/az?page=61 (accessed 1 May 2012).4 See the commentary to lines 2, 5, 7, 9, 12 and the margin, and below, pp. 359–60.

ر�

355Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

Versoر د �ل����ي�ا �ع�مب�د ا

��ي ر �ل��س����ب�د ا

ب ر ع ل �� �ه ا ل ا ��� ل ا مب ��

ا ل �

Translation

Recto1 In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. He is sufficient for me.2 He kisses the earth before our lord and master, chief jud[ge, <main>3 shaykh of Islam, sovereign of the most learned scholars, may God make

mankind enjoy their life [through4 His existence and may He join him into the group of Muḥammad, may

the highest blessings and peace be upon him,5 and he claims that he is a man in a poor condition with a family and that

he was imprisoned because of a remaining part of his taxes6 twice and this is the third time and that he does not receive any visitors

and no request and . . .7 . . . So his petition for the all-embracing bounties and merciful

benevolences8 is that his case be looked at, for the sake of God, may He be exalted, and

that it be passed on to one of the representatives of the9 supreme Shāfiʿī court to look into his case from an Islamic legal point of

view, as an act of mercy10 and kindness toward him and [(they will experience)] the prayer in the

honorable court,11 may God honor, venerate, exalt, and ennoble it. Amen. He (i.e., the slave)

has reported this.

In the right marginPetitionof the slavethe ḥājj Aḥmad al-Adamī.

VersoʿAbd al-Qādiral-Sakandarīa l - K h i ḍ r , p e a c e b e u p o n h i m

356 sijpesteijn

Commentary

Recto1. Ḥisbī Allāh also follows the basmala in a seventh/thirteenth-century pri-

vate letter and in an unpublished Viennese document.5 For the ḥasbala for-mula, see also ḥisbī Allāh wa-kafā, which precedes the basmala in a fourth/tenth-century contract of sale.6 In none of these documents is the direction of writing changed as in our petition, where these words are written at a 90-degree angle to the basmala, even though there is enough space to continue the writing horizontally on the same line.

2. Contrary to other kinds of letters, petitions are composed in the third person.7 According to al-Qalqashandī (d. 821/1418), the standard open-ing formula of Mamluk petitions after the basmala is al-mamlūk yuqabbilu al-arḍ . . . wa-yunhī anna.8 Documents show the phrase coming into regular use with the reign of the Fatimid caliph al-Āmir (r. 495–524/1101–30),9 then devel-oping into a popular expression of politeness which, especially by the Mamluk period, appeared in all sorts of letters, not only petitions.10 Al-Qalqashandī writes that the name of the petitioner in Mamluk petitions appears either directly after the verb yuqabbilu or in the margin of the petition outside the

5 The private letter is kept in the papyrus collection of the Heidelberger Universitäts-Bibliothek (P.Heid.Arab II 68.1). In the commentary to the published edition of this text the editor, Werner Diem, mentions the unedited paper document kept in the collection Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer in Vienna A.Ch. 10366r2.

6 P.Vente 6.1, dated 310/922–23 from the Michaelides collection in Cambridge. The ḥasbala read by Adolf Grohmann in PSR 251 from the papyrus collection of the Heidelberger Universitäts-Bibliothek, in Adolf Grohmann, Einführung und Chrestomathie zur arabischen Papyruskunde (Prague: Státní pedagogické nakladatelství, 1954), 118, and referred to by Rāġib, P.Vente 17n40 (note, however, his incorrect reference to P.Berol. 15093.8 from the Berlin papyrus collection) is not reproduced by the editor of this text, Gladys Frantz-Murphy in CPR XXI 12 and is not visible on the photograph (plate 7 of the same publication).

7 Eva M. Grob, Documentary Arabic Private and Business Letters on Papyrus: Form and Function, Content and Context (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011), 40n41.

8 Aḥmad b. ʿAlī l-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā fī ṣināʿat al-inshāʾ, edited by Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Rasūl Ibrāhīm, 14 vols. (Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-Khidaywiyya, 1913–22), 6:203.

9 Geoffrey Khan, “The Historical Development of the Structure of Medieval Arabic Petitions,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 53 (1990): 24–6; idem, Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents in the Cambridge Genizah Collections (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 309–11; idem, “Judaeo-Arabic,” in Encyclopaedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, ed. C. Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 526–36.

10 Esther-Miriam Wagner, Linguistic Variety of Judaeo-Arabic in Letters from the Cairo Geniza (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 100.

357Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

line of the basmala.11 In this petition the name of the petitioner appears in the right bottom margin (see below, commentary to margin). No initial blessing on the person to whom the petition is addressed occurs in this text, but the titu-lature of the addressee appears as a locative complement, as became common practice from the Ayyubid period onwards.12 There is no space at the end of the line in the lacuna for shaykh, which is to be expected before mashāʾikh on the next line. But see the alternative ways of addressing the chief judges cited in the commentary to line 3.

3. Mattaʿa Allāh bi-wujūdihi al-anām is attested in another petition for a chief judge using form IV of the root m-t-ʿ: amtaʿa Allāh bi-wujūdihi al-anām.13 Cf. in another petition to a chief judge dating from 912/1506: amtaʿa Allāh taʿālā bi-ṭawl ḥayātihi al-anām wa-yunhī.14 In these seventh/thirteenth-century peti-tions the qāḍī l-quḍāt is addressed in almost the same way as in our text: yuqa-bbilu al-arḍ bayna yaday sayyidinā wa-mawlānā qāḍī l-quḍāt shaykh al-islām malik al-ʿulamāʾ al-aʿlām.15

4. Wa-ḥashsharahu fī zumra is not attested in other documents. Cf. wa-sīqa alladhīna . . . zumaran (Q 39:71, 73).

5. Muʿāmala can refer to any kind of financial transaction, among others a partnership (commenda).16 It is also used for taxes due, especially in combina-tion with bāqī, together referring to the remaining part of taxes to be paid.17 Petitioners often refer to themselves as rajul faqīr al-ḥāl wa-dhū ʿayāl.18

11 Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā, 6:203.12 Cf. Khan “Historical Development,” 29–30.13 ʿAbd al-Laṭīf Ibrāhīm, “Silsilat al-dirāsāt al-wathāqīya. I Wathāʾiq fī khidmat al-āthār,” in

al-Muʾtamar al-thānī li-l-āthār fī l-bilād al-ʿArabīya, Baghdād 18–28 November (Tishrīn al-thānī) 1957 (Cairo: Jāmiʿat al-Duwal al-ʿArabīya, 1958), 237, dating to the seventh/thirteenth century.

14 ʿAbd al-Laṭīf Ibrāhīm, “Wathīqat istibdāl,” Majalla Kullīyat al-Ādāb ( Jamīʿat al-Qāhira) 25 (1963), recto lines 4–5.

15 Ibrāhīm “Silsilat al-dirāsāt al-wathāqīya,” 237; Ibrāhīm, “Wathīqat Istibdāl,” 10.16 Cf. Abraham L. Udovitch, Partnership and Profit in Medieval Islam (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1970), 202–03 and n. 107.17 See especially the many attestations of muʿāmala and bāqī l-muʿāmala in al-Nābulsī’s

Taʾrīkh al-Fayyūm; see Abū ʿUthmān b. Ibrāhīm al-Nābulsī (d. c.640/1243), Taʾrīkh al-Fayyūm wa-bilādihi, ed. B. Moritz (Cairo: Bibliothèque Khèdiviale, 1898), 145, 186, and elsewhere. I would like to thank Yossi Rapoport for pointing out to me this meaning of muʿāmala and the occurrences in al-Nābulsī’s text. For the technical use of bāqīya for taxes remaining, see also Petra M. Sijpesteijn, Shaping a Muslim State: The World of a Mid-Eighth-Century Egyptian Official (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 280.

18 Cf. Mark R. Cohen, The Voice from the Poor in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 77.

358 sijpesteijn

6–7. The last words on line 6 and the first word on line 7 pose a problem of reading and interpretation. Laysa lahu zāʾir is followed by a parallel construc-tion, possibly wa-lā maṭlab.

7. Wa-suʾāl al-mamlūk min al-ṣadaqāt al-ʿamīma wa-l-ʿawāṭif al-raḥīma: Using al-ṣadaqāt al-ʿamīma (as opposed to al-sharīfa) is the correct way to address an authority below the sulṭān, according to al-Qalqashandī.19 See also the variants that appear in contemporary petitions: wa-suʾāl al-mamālīk min al-ṣadaqāt al-ʿamīma20 and wa-suʾāluhu min al-ṣadaqāt al-ʿamīma.21 In some cases the person from whom intercession is requested is mentioned after ṣadaqa (e.g., wa-suʾāl al-mamālīk min ṣadaqāt mawlānā).22

8. The encouragement li-wajh Allāh taʿālā appears in a petition dated 749/1348 from St. Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai.23

9. ʿAlā l-wajh al-sharʿī resonates with similar expressions current in Mamluk petitions such as ʿ alā ḥukm sharīʿat al-ruhbān in the seventh/thirteenth- century document from the papyrus collection of the Heidelberger Universitäts-Bibliothek, P.Heid.Arab. II 2.11, and in the examples given in the commentary to this text edition.

9–10. For ṣadaqatan ʿalayhi wa-iḥsānan ladayhi, see ṣadaqatan ʿalayhim wa-iḥsānan ilayhim in two eighth/fourteenth-century petitions both from St. Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai.24

10. Duʿāʾ is written without the hamza following a long vowel.25 This sen-tence seems to relate to the captatio benevolentiae that sometimes appears in petitions from Ayyubid and Mamluk Egypt (e.g., wa-duʿāʾuhum bi-dawām hādhihi al-dawla al-mubāraka;26 wa-adhāqa hādhihi al-dawla al-ʿādīla naʿīm

19 Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā, 6:203.20 D. S. Richards, “A Mamluk Petition and a Report from the Dīwān al-Jaysh,” Bulletin of the

School of Oriental and African Studies 40 (1977), recto lines 9–11.21 Ibrāhīm, “Wathīqat Istibdāl,” 10–11.22 Khan, Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents, no. 92; S. M. Stern, “Petitions from the

Mamlūk Period (Notes on the Mamlūk Documents from Sinai),” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 29 (1966), no. 1; Kāmil Jamīl al-ʿAsalī, Wathāʾiq maqdisīya taʾrīkhīya (Amman: Manshūrāt al-Jāmiʿa al-Urdunīya, 1983; 1985; 1989), 1:213.3–4.

23 Stern, “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” no. 2.8.24 Ibid., no. 3, recto line 10, dated 750/1349; Richards, “A Mamluk Petition,” recto line 12,

dating to the eighth/fourteenth century.25 Simon Hopkins, Studies in the Grammar of Early Arabic: Based Upon Papyri Datable to

Before A.H. 300/A.D. 912 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 21 (§ 20).26 In an Ayyubid petition addressed by the monks of Mt. Sinai to al-Kāmil (r. 1218–38), in

S. M. Stern, “Petitions from the Ayyubid Period,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 27 (1964): no. 2.11.

359Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

ajrihim wa-duʿāʾihim;27 wa-duʿāhum li-hādhihi al-dawla al-ʿāmīra),28 but the exact reading and sense here remains unclear. Maḥkama is difficult to read, seemingly being obscured by a large medial hāʾ written through it, but this reading seems most likely.

12. Anhā dhālika is written with scriptio plena of the long alif in dhālika.29 It represents the common Mamluk closing formula of a request, but already appears in Ayyubid petitions. For Mamluk usage, see three eighth/fourteenth-century petitions from St. Catherine’s monastery and a late seventh/thirteenth-early eighth/fourteenth-century petition concerning a financial dispute.30

Margin. Qiṣṣa is used in the Mamluk period to refer to petitions.31 Aḥmad al-Adamī is not identifiable.

VersoIt is not clear how this name relates to the petition on the recto or to the other text on this side of the paper. The loose Arabic letters are reminiscent of magical writings.32 They might be connected to read al-Khiḍr ʿalayhi al-salām, written with a superfluous alif appearing before the sīn. This reference to the Islamic mythical figure al-Khiḍr might be considered as an apotropaic phrase, perhaps helping the letter to reach its destination or generally offering protection.33

Historical Development of Petitions

The petition edited here contains some standard features of Ayyubid and Mamluk petitions from Egypt and Palestine. When examining these formulae

27 In a Mamluk petition addressed by the monks of Mt. Sinai to Ḥasan b. Muḥammad in 749/1348, in Stern, “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” no. 2.10–11.

28 In a Mamluk petition addressed by the monks of Mt. Sinai to a high dignitary in 750/1349, in Stern, “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” no. 3.10–11.

29 Hopkins, Studies, 14 (§ 11).30 Petitions from St. Catherine’s monastery: P.Heid.Arab. II 4.9, eighth/fourteenth century;

Stern “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” no. 2 recto line 11, dated 749/1348; 3 recto line 11, dated 750/1349; Richards, “A Mamluk Petition,” recto line 12. Petition concerning financial disagreement from the collection Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer in Vienna P.Vind.Arab. III 63 recto line 10, dating to 698–708/1299–1309.

31 Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ, 6:202.32 See Lloyd D. Graham, “Qurʾānic Spell-ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic Talismans,”

online: www.academia.edu/516626/Qur_anic_Spell-ing_Disconnected_Letter_Series_in_Islamic_Talismans (accessed 24 October 2012).

33 I am grateful to Marina Rustow for discussing such an interpretation of this phrase with me.

360 sijpesteijn

in more detail and comparing them with other petitions we can locate the text edited above most certainly in Mamluk Egypt.

To date, a number of Arabic Ayyubid and Mamluk petitions have been published. Petitions and drafts of petitions sent by the Jewish communities of Fusṭāṭ to the Fatimid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk authorities were found in the Geniza collections.34 Petitions are also found among Arabic document collec-tions at universities, libraries, and museums in the Middle East, Europe, and North America, but the provenance of these documents is uncertain, since most of them were bought on the antiquities market in Egypt without any indi-cation of their history.35 The archives of St. Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai36 and the Ḥaram al-Sharīf37 in Jerusalem also contain Ayyubid and Mamluk peti-tions. With these examples it is possible to establish the common features of these petitions as well as the differences in detail in the formulae used, and thus to trace historical developments in chancery practice and formulaic pref-erences related to the rank and position of the addressee.38

The petition edited above exhibits the elements common to these kinds of documents as described by al-Qalqashandī39 and attested in other Mamluk petitions and which continue earlier practices, namely: (1) a basmala; (2) a tarjama (al-mamlūk fulān ibn fulān); (3) an opening formula (al-mamlūk yuqabbilu al-arḍ . . . ); (4) an exposition, a short description of the complaint (wa-yunhī kadhā wa-kadhā); (5) the request (suʾāl al-mamlūk min al-ṣadaqāt

34 Published in Khan, Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents, nos. 70–102.35 Published in P.Vind.Arab. III; Ibrāhīm, “Wathīqat istibdāl”; idem, “Silsilat al-dirāsāt

al-wathāqīya.”36 Stern, “Petitions from the Ayyūbid Period”; idem, “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period”;

Richards “A Mamluk Petition.”37 Al-ʿAsalī, Wathāʾiq maqdisīya taʾrīkhīya; Donald P. Little, A Catalogue of the Islamic

Documents from al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf in Jerusalem (Beirut: Orient-Institut der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft; Wiesbaden: in Kommission bei Franz Steiner, 1984); idem, “Five Petitions and Consequential Decrees from Late Fourteenth Century Jerusalem,” Arab Journal for the Humanities 14 (1996): 348–96; idem, “Two Petitions and Consequential Court Records from the Ḥaram Collection,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 25 (2001): 171–94. The publications by al-ʿAsalī and Little should be studied together with Werner Diem, “Philologisches zu mamlūkischen Erlassen, Eingaben und Dienstschreiben,” Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 33 (1997): 7–67.

38 Al-Qalqashandī prescribes closing off the petition with in shāʾa Allāh taʿālā followed by the ḥasbala and blessings on the Prophet as well as other expressions of piety, see al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā, 6:203. Extant Mamluk petitions show variants in the formulae used; cf. Stern “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” 241 and n. 27 and ḥasbunā Allāh wa-naʿm al-wakīl, in P.Vind.Arab. III 63.10.

39 Al-Qalqashandī’s description is well discussed by Stern (“Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” 239–40).

361Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

al-ʿamīma wa-ʿawāṭif al-raḥīma); (6) a closing formula, including an appeal to the benevolence of the person or institution to whom the petition is addressed (ṣadaqatan ʿalayhi wa-iḥsānan ladayhi); (7) closing blessings and (8) a final ref-erence to the petitioner filing his report (anhā dhālika).

The addition bayna yaday after the opening formula, al-mamlūk yuqabbilu al-arḍ, which appears in this petition, seems to locate it more accurately in place and time. While the additional bayna yaday is not discussed by al-Qalqashandī,40 it is attested in documents. It occurs in the Ayyubid period in a petition addressed to Sulṭān al-ʿĀdil I (r. 596–615/1200–18) whose name is reconstructed by the editor based on the titulature used: [al-mamlūk yuqabbi]l al-arḍ bayna yaday al-mawlā l-sayyid al-ajall . . . [ ] . . . al-humām nāṣir al-Islām ghiyāth al-ā[nām] sulṭān juyūsh al-Muslimīn khallada Allāh mulkahu wa-yunhī.41 This phrase also appears in some Judaeo-Arabic letters addressed to high-ranked Jewish dignitaries and in other letters containing polite requests from the Ayyubid period as well.42

The petition edited above was written to the chief judge (qāḍī l-quḍāt), presumably of the Shāfiʿī legal school in Cairo. Sixth/twelfth and seventh/thirteenth-century Arabic petitions from Egypt addressed to regular qāḍīs do not contain this additional formula, while petitions sent to the chief judge at the Ḥaram al-Sharīf also do not contain this expression.43 Conversely, the two other petitions addressed to Mamluk chief judges in Egypt do display the “bayna yaday” phrase together with some other rather unusual and otherwise unattested formulae that also appear in our petition: yuqabbilu al-arḍ bayna yaday sayyidinā wa-mawlānā qāḍī l-quḍāt shaykh al-islām malik al-ʿulamāʾ

40 Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā, 6:339–40.41 Khan, Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents, no. 88. Diem’s suggestion that the

addition was used for judges and some other high dignitaries below the sulṭān should thus be adjusted; see P.Heid.Arab. II 4.2, commentary.

42 A search in the Princeton Geniza Project’s database yields, for example, a letter to the ga ʾon Sar Shalom ha-Levi (in office ca. 1177–95), see Cambridge, Taylor Schechter Collection (T-S) 10J17.16, line 1; a petition and a letter to Maimonides (d. 1204) ca. 1180, T-S 10J20.5 recto, and T-S 16.291, lines 17–18; a letter to judge Ḥananel b. Shemuʾel (d. 1237), T-S 13J21.22, lines 2–3; and two letters mentioning him, T-S Ar. 54.91, line 2 and Cambridge University Library Collection (CUL) MSS ADD. 3415, lines 1 –2; as well as several undatable letters with requests, for example from a teacher asking to be paid, London, British Museum, Or. 5542.23; to a prominent person asked to repay his debt, T-S 8J14.9; and from a petitioner asking for help in paying the poll-tax, T-S 10J12.4, lines 14.

43 Qāḍīs in the documents from the collection Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer in Vienna P.Vind.Arab. III 67; 68; qāḍī l-quḍāt in the Ḥaram al-Sharīf collection: Diem “Philologisches,” no. 2, dated 799/1388.

362 sijpesteijn

al-aʿlām amtaʿa Allāh bi-wujūdihi al-anām wa-yunhī.44 Another example dated 912/1506 also directed at a chief qāḍī in Cairo similarly contains a variation on part of this formula ( yuqabbilu al-arḍ bayna yaday sayyidinā wa-mawlānā qāḍī l-quḍāt shaykh al-islām amtaʿa Allāh taʿālā bi-ṭawl ḥayātihi al-anām wa-yunhī).45 It seems then that the very exceptional opening formulae used in these three petitions to chief judges from the seventh/thirteenth to the tenth/sixteenth centuries were in some way reserved for the qāḍī l-quḍāt in Mamluk Egypt.

The petition does not contain the endorsement of the judge’s office that we often find on other petitions written on the verso or at the bottom of the petition itself.46 Whether a separate decree was issued in response to the petition—directly to one of the nuwwāb bi-maḥkama as requested in the petition—or whether this petition never reached the intended chief judge or failed to be heard remains unclear.47

An additional remark that dovetails nicely with Mark Cohen’s observation concerning the parallel language of Judaeo-Arabic petitions in the more con-fined context of letters from the poor and Arabic petitions relates to the pres-ence of a common pool of scribal practices from which Christian, Jewish, and Muslim scribes took their information. Scribal changes occurring over time had an impact on the writings produced in these different milieus. The changes in scribal practice can be linked to political and social developments in Egypt.48

Intercessors and Roads of Redress: A Case of Legal Shopping?

Aḥmad al-Adamī was a private individual seeking the help of the court to settle a conflict over money, most likely related to tax arrears that had led to his imprisonment three times. Why did Aḥmad turn to the head of the Shāfiʿī court in Egypt to solve his ongoing financial conflict? The decision of Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn (r. 1171–93) to appoint only one Shāfiʿī qāḍī l-quḍāt in Cairo gave the Shāfiʿīs unprecedented power in Egypt. Not only did the Shāfiʿī court become

44 Ibrāhīm, “Silsilat al-dirāsāt al-wathāqīya,” 237, seventh/thirteenth century.45 Ibrāhīm, “Wathīqat istibdāl,” recto lines 4–5. 46 E.g. P.Vind.Arab. III no. 68, seventh/fourteenth century; Khan, Arabic Legal and

Administrative Documents, nos. 95, 98.47 Cf. Stern, “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” 245. Stern fails to identify a pattern behind

the presence or absence of endorsements on the petitions, describing it rather as “to a certain degree arbitrary.” See, however, Khan, Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents, 305, who wonders whether unendorsed petitions “were submitted but failed to be processed in the appropriate manner due to clerical negligence.”

48 See for example the disappearance of opening blessings for the Fatimid caliphs resulting from the rise of power of the vizier, as discussed in Khan “Historical Development,” 26–7.

363Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

the most important medium for the legitimate use of power, but the Shāfiʿī judge also functioned as a means (requested and unrequested) to overrule verdicts of the other schools.49 This situation lasted until 660/1262, when Sulṭān Baybars (r. 1260–77) established four chief judgeships in Cairo—for the Shāfiʿī, Mālikī, Ḥanafī, and Ḥanbalī schools—with equal powers.50 This situ-ation, which lasted until the Ottoman conquest, was paralleled over the next century in other Mamluk cities such as Damascus, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Tripoli, and Gaza.51 The Shāfiʿī school, however, continued to be dominant during the Mamluk sultanate.

The chief qāḍīs of the four legal schools were present at the audiences that the Mamluk sulṭāns held for petitioners and were consulted by the sulṭān if he deemed it necessary.52 This petition, however, is directly addressed to the qāḍī l-quḍāt without the intermediary of the sulṭān. In addition to the petitions to the sulṭān that may have been forwarded to the discretion of lower officials, many extant petitions were in fact formally addressed to officials such as qāḍīs, viziers, and other dignitaries and dealt with by them.53

Although addressed to the Shāfiʿī qāḍī l-quḍāṭ, there is no indication that the petition should be located in the period described above when there was only one, Shāfiʿī, qāḍī l-quḍāṭ. Aḥmad turned to the chief Shāfiʿī judge because Aḥmad considered him to have most intercessory power and to be most useful in solving his conflict. Representing the highest legal authority in the sultanate, the Shāfiʿī qāḍī l-quḍāṭ would have been, in that sense, a powerful addressee.54 It is also possible that the Shāfiʿī chief judge was actually in charge of the prison where Aḥmad was kept. After all, in the Mamluk period, those judged by the chief judges, especially debtors, were incarcerated in so-called sujūn al-quḍāt,

49 Sherman Jackson, Islamic Law and the State: The Constitutional Jurisprudence of Shihāb al-Dīn al-Qarāfī (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 54.

50 Ibid., 52; Karen Stilt, Islamic Law in Action: Authority, Discretion and Everyday Experiences in Mamluk Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 34; Yossef Rapoport, “Legal Diversity in the Age of Taqlīd: The Four Chief Qāḍīs Under the Mamluks,” Islamic Law and Society 10 (2003): 210–28; Joseph H. Escovitz, The Office of the Qāḍī al-Quḍāt in Cairo under the Bahri Mamluks (Berlin: Schwarz, 1984).

51 Yossef Rapoport “Siyāsa and Sharīʿa: A Legal History of the Mamluk Sultanate,” Mamluk Studies Review 16 (2012): 76.

52 Stern, “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period,” 265.53 Cf. ibid., 258. Stern did not know at the time of any examples of this kind and expresses

his surprise at the petition and endorsement issued by some dignitary (n. 3). But see Khan’s discussion of Fatimid practice of petitions directed at caliphs and viziers, in Khan, “Historical Development,” 27. Cf. Khan, Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents, nos. 72, 78–85, 93–102.

54 Rapoport, “Legal Diversity,” 217.

364 sijpesteijn

while sujūn al-wulāt were intended for criminals taken in by the wālī.55 It is not clear, however, whether, the quḍāṭ also administered these prisons.56 Rather than appealing to one of the representatives of the maḥkama, Aḥmad appeals to the highest authority, who was also head of the court.57

Aḥmad’s reference to the reason for his imprisonment, an outstanding debt from a financial transaction or more precisely a tax payment due (ʿalā bāqī muʿāmalatihi), places him in the category of debtors. Due to the stricter doctri-nal position, most debtors’ cases ended up at the Ḥanafī court. While most law-yers upheld the position that debtors who are declared bankrupt do not have to pay off their debts, only the Ḥanafīs maintain the strict interpretation that bankruptcy is only accepted after a period of imprisonment.58 Aḥmad’s time in jail might be related to his claiming bankruptcy in order to avoid paying his debt. His petition to the Shāfiʿī chief judge, whose school did not maintain the Ḥanafīs’ strict interpretation, might be interpreted as an attempt to have himself declared bankrupt and insolvent directly in the Shāfiʿī court and might thus be considered a case of legal shopping.59

It is of course known that premodern prisons were not used for punishment, but rather as a place to keep accused individuals whose cases were pending judgments, and those convicted and awaiting punishment or payment of their

55 In 741/1341 the sulṭān al-Nāṣir Muḥammad (r. 1293–4; 1299–1309; 1309–41) “freed the prisoners who were being held in the prisons run by the governors of al-Qāhira and Fusṭāṭ and those under the authority of the Chief Judges”; see Aḥmad al-Maqrīzī, Kitāb al-sulūk li-maʿrifat duwal al-mulūk, ed. Muḥammad Muṣtafā Ziyāda, 4 vols. (Cairo: Lajnat al-Taʿlīf wa-l-Tarjama wa-l-Nashr, 1956–73), 2:519, cited in Adam Sabra, Poverty and Charity in Medieval Islam: Mamlūk Egypt 1250–1517 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 64. In 721/1321 a high court official, Karīm al-Dīn al-Kabīr “had all the imprisoned debtors brought forward,” appeased them with their creditors and released them “so that there was no one left in the sijn al-quḍāt and it was closed,” in al-Maqrīzī, Sulūk, 2:228, cited in Sabra, Poverty and Charity, 64, in a more limited way. I would like to thank Jo van Steenbergen for pointing me to the more extensive description. See also additional examples of debtors ending up in the chief judges’ prisons cited by Sabra, Poverty and Charity, 65–6. Cf. sujūn al-ḥukm al-ʿazīz, mentioned in a waqf endowment dated 707/1307, cited by Sabra, Poverty and Charity, 86.

56 I would like to thank Jo van Steenbergen for pointing out this nuance to me.57 Similarly, the petitioner in charge of postal horses and animals powering certain

watermills requests a document instructing a local ruler to urge farmers to bring hay to feed the animals, rather than appealing to the local ruler himself, see P.Vind.Arab. III 51, 698–708/1299–1309.

58 Rapoport, “Siyāsa,” 83.59 As in Yossef Rapoport’s description of the mechanism of “Legal Diversity,” 220–21.

365Financial Troubles: A Mamluk Petition

debt or fine.60 Also, prisoners depended on outside contacts for food and other basic provisions for the duration of their incarceration. This petition is an example of the frequent and open contacts between prisoners and the outside world. Additional petitions were written by incarcerated individuals, such as the sixth/twelfth-century letter addressed to a judge in which a miller asks the judge to send someone to provide food and water for his camels while he is in prison.61 In another, much earlier letter written on papyrus, a prisoner requests that the addressee look into the false accusation that he claims is the cause of his incarceration.62

Select Bibliography

al-ʿAsalī, Kāmil Jamīl. Wathāʾiq maqdisīya taʾrīkhīya. 3 vols. Amman: Manshūrāt al-Jāmiʿa al-Urdunīya, 1983–89.

Cohen, Mark R. Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

———. The Voice from the Poor in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Diem, Werner. “Philologisches zu mamlūkischen Erlassen, Eingaben und Dienstschreiben.” Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 33 (1997): 7–67.

———. Arabische Briefe auf Papyrus und Papier aus der Heidelberger Papyrus–Sammlung. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1991.

———. Arabische amtliche Briefe des 10. bis 16. Jahrhunderts aus der österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Wien. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1996.

Frantz-Murphy, Gladys, ed. Arabic Agricultural Leases and Tax Receipts from Egypt 148–427 A.H./765–1035 A.D. Vienna: Brüder Hollinek, 2001.

Ibrāhīm, ʿAbd al-Laṭīf. “Silsilat al-dirāsāt al-wathāqīya. I Wathāʾiq fī khidmat al-āthār.” In al-Muʾtamar al-thānī li-l-āthār fī l-bilād al-ʿarabiyya. Baghdād 18–28 November (Tishrīn al-thānī) 1957, 205–87. Cairo: Jāmiʿat al-Duwal al-ʿArabiyya, 1958.

———. “Wathīqat istibdāl.” Majalla Kullīyat al-Ādāb ( Jamīʿat al-Qāhira) 25 (1963).Hopkins, Simon. Studies in the Grammar of Early Arabic: Based Upon Papyri Datable to

Before A.H. 300/A.D. 912. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.Jackson, Sherman A. Islamic Law and the State: The Constitutional Jurisprudence of

Shihāb al-Dīn al-Qarāfī. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

60 For the Islamic prisons, the case has been made by Irene Schneider, “Imprisonment in Pre-Classical and Classical Law,” Islamic Law and Society 2 (1995): 157–73.

61 P.Vind.Arab. III 67.62 This unpublished second/eighth-century Viennese papyrus will appear in my forthcoming

publication Structures of Dependency in Early Islamic Egypt.

366 sijpesteijn

Khan, Geoffrey. Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents in the Cambridge Genizah Collections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1993.

———. “The Historical Development of the Structure of Medieval Arabic Petitions.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 53 (1990): 8–30.

Little, Donald P. “Two Petitions and Consequential Court Records from the Ḥaram Collection.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 25 (2001): 171–94.

———. “Five Petitions and Consequential Decrees from Late Fourteenth Century Jerusalem.” Arab Journal for the Humanities 14 (1966): 348–94.

———. A Catalogue of the Islamic Documents from al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf in Jerusalem. Beirut: Orient-Institut der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft; Wiesbaden: in Kommission bei Franz Steiner, 1984.

al-Maqrīzī, Aḥmad (d. 845/1442). Kitāb al-sulūk li-maʿrifat duwal al-mulūk. Edited by Muḥammad Muṣṭafā Ziyāda. Cairo: Lajnat al-Taʿlīf wa-l-Tarjama wa-l-nashr, 1956–73.

al-Qalqashandī, Aḥmad b. ʿAlī. Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā fī ṣināʿat al-inshāʾ. 14 vols. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-Khidiyawīya, 1331–38/1913–22.

Rāġib, Yūsuf, ed. Actes de vente d’esclaves et d’animaux d’Égypte médiévale I (Cahier des Annales Islamologiques 23). Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 2002.

Rapoport, Yossef. “Legal Diversity in the Age of Taqlīd: The Four Chief Qāḍīs Under the Mamluks.” Islamic Law and Society 10 (2003): 210–28.

———. “Siyāsa and Sharīʿa: A Legal History of the Mamluk Sultanate.” Mamluk Studies Review 16 (2012): 71–102.

Richards, Donald S. “A Fāṭimid Petition and ‘Small Decree’ from Sinai.” Israel Oriental Studies 3 (1973): 140–58.

———. “A Mamluk Petition and a Report from the Dīwān al-Jaysh.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 40 (1977): 1–14.

Sabra, Adam. Poverty and Charity in Medieval Islam: Mamlūk Egypt 1250–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Schneider, Irene. “Imprisonment in Pre-Classical and Classical Law.” Islamic Law and Society 2 (1995): 157–73.

Sijpesteijn, Petra M. Shaping a Muslim State. The World of a Mid-Eighth-Century Egyptian Official. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Stern, S. M. “Petitions from the Ayyūbid Period.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 27 (1964): 1–32.

———. “Petitions from the Mamlūk Period (Notes on the Mamlūk Documents from Sinai).” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 29 (1966): 233–76.

Stilt, Kristen. Islamic Law in Action: Authority, Discretion and Everyday Experiences in Mamluk Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Tillier, M. “Vivre en prison à l’époque abbasside.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 2 (2009): 635–59.

Wagner, Esther-Miriam. Linguistic Variety of Judaeo-Arabic in Letters from the Cairo Genizah. Leiden: Brill, 2010.