Exploring the dynamics of REDD in forest communities. K. Evans, L. Murphy and W. de Jong

Transcript of Exploring the dynamics of REDD in forest communities. K. Evans, L. Murphy and W. de Jong

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

Global versus local narratives of REDD: A case study fromPeru’s Amazon

Kristen Evans a,*, Laura Murphy a, Wil de Jong b

a Stone Center for Latin American Studies, Tulane University, United StatesbCenter for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University, Japan

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 20 December 2011

Received in revised form

18 December 2012

Accepted 19 December 2012

Keywords:

Amazon

Communities

Future scenarios

Global forest governance

Participatory methods

REDD

Tropical forests

a b s t r a c t

This paper seeks to analyze local perspectives in Peruvian Amazon forest communities

toward REDD and contrast those perspectives with current global and national REDD

narratives. REDD is a global market-based approach to provide financial incentives for local

actors to halt deforestation or to improve carbon stocks. To date, the REDD framework has

not demonstrated that it is equipped to incorporate the diverse perspectives, potential

interactions and uncertainties facing forest communities. We interviewed forest commu-

nity members in the Amazonian state of Loreto, Peru, using ‘‘future scenarios’’ methods to

elicit potential alternative narratives, both with and outside REDD. Indigenous voices reveal

ambiguous attitudes toward REDD with regard to livelihoods, benefit distribution and the

long-term impacts for communities and forests. They reveal considerable uncertainty about

the future and lack of trust in governance regimes. Long-term community priorities were in

generating work, providing educational opportunities for their children, and improving the

quality of their forest. Conflict—within the community, with local loggers and with the

recently established regional conservation area—was a prevalent theme. A REDD design

that recognizes communities as active participants in global and national climate manage-

ment and pays attention to local narratives will more likely generate the multiple benefits of

healthy forests, strong communities and, ultimately, global climate change mitigation.

# 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envsci

1. Introduction: forests and REDD

While the rate of tropical deforestation is slowing, losses of

biodiversity and biomass continue to mount (FAO, 2011) and

deforestation and forest degradation remain one of the main

sources of carbon dioxide emissions. Overall, about 20% of

annual carbon output originates from clearing or degrading

forests (IPCC, 2007). Recognizing the role of forests as a carbon

sink is essential to mitigating global climate change (Stern,

2006). REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and

forest Degradation) is a mechanism to implement the UNFCCC

(United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change).

* Corresponding author.E-mail address: [email protected] (K. Evans).

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

1462-9011/$ – see front matter # 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reservedhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

REDD+ is used as a broad term that encompasses the range of

forest conservation and reforestation options and financing

mechanisms being negotiated at the global and national levels

to reduce deforestation and forest degradation and improve

forest carbon stocks in order to mitigate climate change

(Peskett et al., 2008). REDD payments may come from national

funds set up by multilateral institutions, donor countries or

NGOs, or from emerging global carbon credit markets (Skutsch

and McCall, 2011). The United Nations REDD Programme (UN-

REDD) predicts that total financial flows from national funds

and carbon markets could reach US$30 billion a year (UN-

REDD, 2011). REDD aims to provide performance-based

payments to forest landholders in developing countries who

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

.

1 http://www.ilo.org/indigenous/Conventions/no169/lang_en/index.htm.

2 http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIP-S_en.pdf.

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x2

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

conserve their forests (Wunder, 2009). It involves establishing

a baseline for past emissions, generating business-as-usual

scenarios to predict future pathways of the emission curve,

verifying tenure and coordinating with national governments

to develop national REDD plans, and creating monitoring,

reporting and verification schemes for negotiated emission

reduction (Angelsen, 2009).

Contrasting with the global blueprint of REDD are local

forest communities. Approximately 22% of the world’s tropical

forests are owned or managed by communities (White and

Martin, 2002), and forests are home to some of the most

marginalized and poor people in the world (Sunderlin et al.,

2005). The participation of communities in REDD is considered

by many to be necessary for the mechanism to succeed in

reducing overall carbon emissions (Skutsch and McCall, 2011).

While some REDD designers see the effort as primarily an

environmental initiative with ‘‘no-harm’’ to communities,

pro-poor advocates have voiced concerns that REDD could

negatively impact upon forest communities and indigenous

groups and that too few safeguards exist to protect their

interests (Lovera, 2008; Gluck et al., 2010; Peskett et al., 2008).

Weak tenure regimes could lead to displacement of commu-

nities if more powerful local actors (e.g. ranchers, loggers,

government, and corporations) assume rights over their forest

(Wollenberg and Springate-Baginski, 2009; Lovera, 2008).

Communities are internally diverse in their histories, internal

organization, livelihood strategies and networks, and there

are risks of resource appropriation and elite capture within

communities (Peskett et al., 2008; Cano, 2012). Thus, nominally

apolitical incentives could create new tensions and incentives

to degrade forests (Lovera, 2008).

Pro-poor advocates argue that if REDD simply provides

compensation for lost livelihoods by paying people what they

would have received from a deforestation activity like logging,

REDD would become a ‘‘poverty reproducer’’ (Wollenberg and

Springate-Baginski, 2009). Instead, REDD should provide

additional income, alternative livelihoods, land tenure secu-

rity and local resource rights for communities (Skutsch and

McCall, 2011; Wollenberg and Springate-Baginski, 2009;

Peskett et al., 2008). The REDD framework must also provide

long-term pathways out of poverty and the pressure for

reducing deforestation should not fall solely on the commu-

nities themselves (Wollenberg and Springate-Baginski, 2009).

Therefore, context-specific links between poverty, develop-

ment and deforestation must be considered carefully in the

underlying assumptions, design and implementation of REDD

(Peskett et al., 2008).

At the heart of this controversy lies a governance limitation

of international environmental regimes such as UNFCCC and

derived instruments like REDD, and how much space they

leave for implementation at national level. This paper

hypothesizes that while current international climate change

policy mechanisms capture the highly diverse perceptions

and aspirations of local forest dwellers, indigenous peoples

and other forest based societies, there is a huge gap at the

national level where complex interests, environmental priori-

ties and poor governance practices are concerns for unpre-

dictable outcomes from internationally agreed climate change

policies. We examine two indigenous communities in Peru to

reveal pluralistic voices and much ambiguity, and contrast

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

those perspectives with global and national narratives that led

to the arrival of REDD mechanisms in remote corners of the

Peruvian Amazon. By signaling those contrasts and the

possible negative implications they may have for the

implementations of REDD programs and by suggesting some

possible ways forward we aim to contribute to the widely

signaled disparity between climate change narratives in global

environmental governance and local on the ground realities

where global governance has direct impacts.

In the following section, we outline climate change in both

global governance and Peru’s domestic governance and how

this incorporates the voice of indigenous people. Section 3

introduces our field methods. Section 4 presents the results of

our work in indigenous communities in the Amazon Basin of

Peru. We then use the results of our field work for an

alternative framing of REDD, which we compare with the

global narratives (Section 5). In the final section, we reflect on

how the political process of climate change needs to connect

with the local realities that we have analyzed in this paper.

2. Global and national climate governance andlocal communities

One of the causes leading to the problem whereby local

communities are marginalized in REDD is the imperfect

democracy of global governance and its implementation

nationally. Several profound changes in governance practice

and theory have occurred worldwide in recent decades

reflected by concepts such as democratization, decentraliza-

tion, and new modes of governance (e.g. Arnouts, 2010). The

worldwide shift in governance values, including new demands

for democratic and stakeholder participation, has had a

profound influence on international environmental regimes,

and they in turn have had profound influences on national

forest policies, for instance through national forest programs.

Some international agreements, such as the Convention on

Biological Diversity (CBD), provide for participation from

communities while the United Nations Forum on Forests

(UNFF) has regular multistakeholder dialogs as an informal

input in conference of parties (COP) meetings (Hiraldo and

Tanner, 2011). International Labour Organization Convention

1691 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous People2 stipulate that indigenous and tribal people

should be consulted in any matters relevant to them and the

use of their traditional lands. In Peru, Law 29785 on Previous

Consultation (El Peruano, 2011) grants the right to indigenous

communities to be consulted on any legislative or adminis-

trative matters that directly affects their collective rights, their

physical existence, cultural identity or quality of life, or their

development. This has resulted in an indigenous climate

change counter-narrative, which emphasizes industrialized

countries’ responsibility for current levels of greenhouse gas

emissions, the low carbon production and consumption habits

of indigenous peoples, and unique indigenous capacities for

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x 3

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

climate change adaptation and mitigation (e.g. PFII, 2010).

However, Peruvian indigenous peoples have been less

noticeable in influencing, for example, UNFCCC related

decision making (Hiraldo and Tanner, 2011), or the preparation

of Peru’s Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP).3

Peru’s R-PP was presented in 2011 and has received

comments from many actors (e.g. Murdiyarso et al., 2012),

but specifically from AIDESEP (2011), the association that

represents ethnic indigenous organizations of the Peruvian

Amazon. Murdiyarso et al. (2012, p. 679) considers Peru to be

one of the countries that require ‘‘transformational changes

beyond the forestry process’’. This observation is shared, for

instance, by Pokorny et al. (forthcoming) and de Jong et al.

(2010) who observe that the largest threat to REDD implemen-

tation in Peru remains aggressive Amazonian development

ambitions. In the case of the country’s REDD implementation

plans, AIDESEP (2011) questions a number of aspects of the

Peru proposal, including the lack of land or carbon property

rights over forest or carbon stocks that will be addressed in

subsequent REDD policy implementations, clear mechanisms

that guarantee rural dwellers to have a full and active role in

the decision making process, and the lack of measures that

will prevent an invasion of REDD projects into people’s

territories and lives. As for the latter, Peru has several

experiences of so-called ‘‘carbon cowboys’’, in other words

entrepreneurs who, exploiting inadequate legal or adminis-

trative definitions, negotiate with remote forest dwellers

carbon agreements, which they subsequently use to raise

funds from international investors.4

In international, and especially, national negotiations on

REDD the input from local communities and indigenous

peoples is considered necessary. A question, however,

remains: How does the global and national structuring of

the climate regime, including both dominant and counter

climate and forest narratives, actually reflect local perceptions

and aspirations related to climate change, proposed forest

based solutions to climate change and the implications that

this might have for local forest dwellers? Or, reformulating the

same question more operationally: What are the local

narratives on REDD, and can it be helpful for international

and national REDD programs to be better aware of the

particularities of these narratives?

In this paper we contribute evidence to answer these

questions. Such questions are relevant when evaluating the

convoluted global political processes of forest based climate

change mitigation, and are equally important for the out-

comes of national proposals for REDD implementation. For

this purpose we compiled the divergent visions of, first, the

global narrative on REDD that emerges from online and

printed source material from international organizations and

from Peru’s national REDD community and, second, narratives

of indigenous communities that reside in the Peruvian

Amazon, and who are being targeted for involvement in

REDD projects. We use the concept of global narrative as an

equivalent of discourse as defined by Hajer and Versteeg (2005,

p. 175) as: ‘‘an ensemble of ideas concepts and categories

through which meaning is given to social and physical

3 http://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/fcp/PE.4 http://www.redd-monitor.org/2012/09/18/.

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

phenomena, and which is produced and reproduced through

an identifiable set of practices’’. We see the concept of local

narrative as the equivalent of a discourse among actors who

do not rely on printed or electronically reproduced media, as is

the case with most Amazonia tropical forest dwellers. In this

view, local narratives are stylized stories on certain conten-

tious issues among a certain confined group that express

shared, debated and thus evolving views on such issues.

Global and local narrative analyses are useful for this

purpose, as the former reflect dominant policy and program-

matic thinking among the REDD establishment, which

strongly influences how national REDD programs will be

implemented in countries such as Peru. We also argue that

local narratives which emerge in response to global narratives

are an appropriate indicator to judge how proposed solutions

like REDD are perceived locally, as well as to anticipate

challenges with their implementation. Local narratives, in

turn, when examined together with global and national

narratives provide an indication on how well proposed locally

constructed solutions may contribute to resolving global

issues such as climate change.

We refer to Lynam et al. (2007) and Evans et al. (2006, 2008,

2010) who discuss research methods to elicit local views and

preferences, similar to those that rural Amazonia dwellers

may have on climate change or mitigation mechanisms and

which are reflected in local narratives, to support the choice of

future scenarios, participant observation and semi-structured

interviews that we used in our research.

3. Field methods

3.1. Research location

The Ampiyacu-Apayacu river basin in the northeastern state

of Loreto in Peru is a vast, almost impenetrable swathe of

Amazon forest. Four small communities comprise our field

sites. Most data collection occurred in two sister settlements;

Pucaurquillo inhabited by Boras, and Pucaurquillo inhabited

by Huitotos. The two villages, although having the same name,

maintain separate leadership, physical spaces and identities,

but share a school, church, phone service, and electricity

network (IBC, 2010).

Most families in the Ampiyacu-Apayacu river basin grow

manioc and plantain as their main staples in swiddens, in

addition to a plethora of annual and perennial crops

(Denevan and Padoch, 1987). Fifty percent of the families

generate cash from sales of surplus agricultural products,

and tourism provides modest income to a handful of

families. Logging is a common activity for the men, employ-

ing by most estimates at least half of the male villagers and

households. Most community members work as peones

(laborers) earning a daily wage of 10–15 soles5 per day, but

some residents strike deals with timber merchants, hire a

team, manage supplies and transportation and oversee the

felling of trees and transportation of timber. In villages on the

Apayacu River, commercial fishing is the primary source

5 At the time of interviews 1 sol was equal to US$0.35. http://www.oanda.com/currency/historical-rates/.

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x4

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

of income generation, which is also illegal but financially and

physically less risky than logging.

A new regional conservation area (Area de Conservacion

Regional Ampiyacu-Apayacu, ACR-AA), of 433,099 ha was

established in 2011, covering most of the river basin (IBC,

2010). ACR is a new designation created in 2010 to allow

departmental governments in Peru to establish and manage

conservation areas. The 17 indigenous communities in the

ACR-AA watershed are considered its ‘‘primary beneficiaries’’

(IBC, 2010). Whether ecosystem services might be an alterna-

tive for communities, and who would benefit from REDD

payments associated with the ACR-AA, was unclear to local

experts consulted at the time (field interviews). Currently, a

new Environmental Services Law is awaiting approval by the

Peruvian Congress. According to the law, the regional

government could choose to transfer environmental services

usufruct rights to communities, although it is not required to

do so (MINAM, 2011).

Owing to its remoteness, the Ampiyacu-Apayacu river

basin is considered by some REDD experts to be under less

conversion pressure than other parts of Peru (Percy Summers,

pers. comm., May 2010), with the exception of rampant illegal

logging. Armas et al. (2009) consider the region to be

‘‘moderately threatened’’.

3.2. Narratives, participant observation, and futurescenarios

We conducted narrative-based participant observation, indi-

vidual interviews and future scenarios workshops (Leach

et al., 2010; Evans et al., 2006) in indigenous communities

during May–June 2010. We used Spanish language for the

interviews, as residents of the villages in the Ampiyacu-

Apayacu basin speak this language in addition to their native

language. We engaged in a process of information sharing

about REDD, whereby we made 32 informal presentations at

community meetings and households on key concepts of

climate change, the carbon cycle, payments for ecosystem

services, and REDD to inform participants about the science

and proposals. We also held informal discussions and

conducted interviews. This created a common base of

knowledge to engage in informed discussions about REDD.

We selected twenty households, including farmers, loggers,

laborers, fishermen, artisans and schoolteachers, community

leaders, and leaders of the indigenous federation (FECONA for

its acronym in Spanish) for detailed interviews. Interviewees

were asked questions about livelihood activities, knowledge of

REDD, prospective use of REDD benefits and, finally, how they

thought the REDD scheme might impact upon the community.

We also interviewed political leaders and merchants for their

views on the matter.

We also ran participatory ‘‘future scenarios’’, methods to

help people think about their own complex lives and physical

and social environments, and create narratives about the

future (Brewer, 2007; Evans et al., 2006; Peterson et al., 2003b).

Participants developed realistic stories of possible outcomes

based on their understanding of the driving forces of change

and contingencies resulting from uncertainty. The intention

was to consider a variety of possible futures rather than to

focus on the accurate prediction of a single outcome (van der

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

Heijden, 1996; Peterson et al., 2003a; Wollenberg et al., 2000;

Evans et al., 2006, 2008, 2010).

For the communities members who participated in this

study, the objective was to allow individuals to construct their

own narratives for their future in which REDD is part of the

plot. First, the concerns expressed by respondents through

interviews were compiled into major themes; these were then

posted for discussion. During the scenarios exercise, partici-

pants reviewed the themes, discussed them, then individually

ranked by voting for the three most important concerns. The

concerns formed the basis for defining ‘‘driving forces’’, or

influences that affect the future of the community. Partici-

pants then engaged in the scenario-building process. They

generated narratives that included those driving forces.

The activities created a space for community members to

share and construct potential futures based on discussions of

the drivers of change affecting them. The future scenarios

workshop was performed first with a group of 12 adults. All

members of the community were invited to attend; those who

did participate generally held some position in the communi-

ty, for example as a teacher, officer of FECONA, president of

the natural resources management committee or some other

role. The workshop was then repeated with a group of 38 high

school students (Evans, 2010). The interviews and the

narratives were transcribed and translated. This complete

set of results was analyzed, the frequency of answers was

tabulated, and themes were identified. The results were

synthesized and are described below. Household data were

used to calculate incomes, which are included in the themes

and also compared against rough calculations of REDD income

(see Appendix). Finally, the scenarios were compiled to share

community members’ visions of a future with REDD.

We recognize that this methodology has limitations.

Informing a community about REDD and then discussing

local perspectives on REDD challenges the researcher to make

it clear that there are assumptions involved in the information

given. We have attempted to make these assumptions clear to

participants particularly because REDD has not fully formed in

the international debate. However, the objective of this

process was to creatively construct community narratives in

order to reveal local perspectives on the contemporary issues

surrounding REDD, including deforestation, livelihoods and

financial incentives. This is a process, not fundamentally

different from public participation processes in the formula-

tion of legislation or public policies, common in most modern

democratic national and subnational administrations. The

REDD discussions provided a catalyst to stimulate that

expression. Furthermore, the challenges of communicating

and understanding REDD and its possible outcomes—by

community members, researchers and REDD experts alike—

was itself an informative result of the activity.

4. Local narratives about REDD

The following section synthesizes the results of the inter-

views, participant observation and scenarios into major

themes, which include: widespread illegal logging and its

complex connection to rural livelihoods; the deeply ambigu-

ous attitudes toward REDD; and concerns about prospects for

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x 5

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

appropriate governance of REDD. These results intersect to

raise concerns over possibility for fair local distribution of the

benefits and the inclusion of ACR-AA resources in benefits.

4.1. Livelihoods and logging

The average income of the families interviewed is 215 soles/

month; income from handicrafts ranges from 20 to 200 soles/

month (1 US dollar equaled approximately 3 Peruvian soles at

the time of our field research). Agriculture earnings are 20–

600 soles/month, with a median of 50 soles/month for 6–8

months of the year. Logging laborers might earn 96 soles/

month for 1–4 months of the year, or 400–600 soles for the

season, and loggers typically net 3000 soles during the season.

Schoolteachers earn 900 soles/month on average. One shop-

keeper grosses 1005 soles/month; widely known to be a logger,

he claimed that his income came from running a store.6 Not

surprisingly, in this economic context community members

express divided opinions about lucrative but illegal and

dangerous logging. Many receive some income from illegal

logging.

Because commercially valuable species have already been

extracted from the communities’ lands, logging is now

occurring entirely upriver, but within the borders of the

ACR-AA. Logging is a seasonal activity, during the rainy

months from December to April when the rivers rise and

seasonal small streams allow funneling tree trunks into the

river. Massive trunks, deep water and rainy, slick conditions

make logging dangerous business; injury and deaths are

common. Logging is also financially risky as work is organized

through debt-peonage relationships. Merchants, usually from

Iquitos, the regional capital, give the local loggers habilito (cash

or in-kind advances), and the loggers pay off their debt in

wood. The merchants purposefully underestimate the volume

of the timber and many loggers cannot harvest enough wood

to pay off their debts. Loggers create their own debt-peonage

arrangements with their own laborers. Laborers are charged

elevated prices for provisions in the forest. The loggers might

also provide in-kind habilito to laborer’s families prior to the

harvest when food is most needed.

FECONA charges ad hoc fees of 50 soles for 100 4-m long

sawlogs and 300 soles for 150 timber quarters to loggers who

float wood down the Ampiyacu River (data from field inter-

views). While exploitative, dangerous and illegal, logging

allows Ampiyacu residents to receive cash and goods through

habilito. Although people commonly become mired in debt,

they also are able to receive money upfront during a family

emergency or at the beginning of the school year.

Respondents know that the forest is being degraded. Sixty

percent used the terms ‘‘destruir’’ (destroy), ‘‘depredar’’

(depredate), ‘‘maltratar’’ (mistreat) or ‘‘desordenado’’ (disor-

dered) in their descriptions of current forest activities.

However, families that are logging feel that they have few

other alternatives to earn cash and many would welcome

another equally lucrative option. Community members who

do not engage in logging say much of the income from logging

6 A store in this case is a very simple affair, usually a small roomin a household that sells a limited assortment of dry goods. Therewere 3-4 shops in the two Pucaurquillos.

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

is wasted, and not used wisely. When asked what people will

do when there are no more trees to log, several community

members mentioned that people will likely move to Iquitos

and even Lima. One community member said that he would

turn to commercial fishing or coca cultivation, both illegal

activities.

4.2. The potential benefits of REDD

There is skepticism about the potential for REDD to work in the

community. One logger said that the community is too divided

and could never organize itself to make REDD happen, and

there must be an alternative to logging that generates similar

income. Other respondents said that 20% of the community

will not go along with REDD, and that the loggers are going to

be a source of problems for REDD unless other work is found

for them.

Others say that with a payment, conservation will work.

Suggested incentive payments range from 50 to 400 soles/

month per family. Community members also frequently

expressed interest in reforestation activities and the possibili-

ty that these could be incentivized under a REDD project.

Fifteen out of twenty respondents say that REDD would

have a positive impact on the community by providing

income, improving life for families, restoring the quality of

the forests and providing employment for young people. The

majority of respondents believe that for REDD to work, all

families need to benefit and all must be involved: if one family

fails, everyone does. Yet, many felt it would be difficult to

persuade all families to support REDD. Furthermore, some

respondents were uncertain as to how individuals or families

will be held accountable under the common-tenure manage-

ment regime: ‘‘You cannot do this individually. Every

community has to be in charge of its territory, and everyone

has to take responsibility’’ commented one informant. Others

emphasized that there must be processes in place to ensure

compliance: ‘‘When you have monitoring and oversight, yes,

[REDD] will function.’’

One idea that was popular with several respondents was to

set aside some portion of REDD money to create a higher

education fund. Several informants brought up the pitfalls of

using ‘‘REDD money’’ to invest in income-generating commu-

nity projects. Prior attempts to develop new income-generat-

ing activities, such as new agricultural products, have

generally failed due to either poor implementation or lack

of a market. External pressures are collapsing the local market

for many locally produced goods, cutting off livelihood options

for agricultural products and any new income-generating

projects. Of those respondents who desired projects, the key

theme was work: community members want and need

income-producing work.

4.3. Potential for conflict

There was concern over the administrative capacity of

government agencies. The majority of respondents expressed

concerns that FECONA and community leaders are not

currently capable of administering a project such as REDD

and distributing benefits fairly. Corruption and lack of

administrative capacity were two commonly provided

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x6

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

reasons. For example, when asked who should administer

REDD and the distribution of benefits, 16 of the 20 respondents

did not trust FECONA to handle payments that would come

from REDD. One informant stated: ‘‘There are no leaders

trained in administration. Before REDD arrives, the leaders

must be trained. If benefits were to arrive now, everything

would be misspent’’.

Stories of abuse of authority in FECONA and the use of

funds for personal gain were common. There are no

mechanisms for transparency and control within FECONA.

Two of the three respondents who support FECONA to

handle REDD funds were (not surprisingly) the FECONA

president and secretary. Even other FECONA officers admit

that the organization needs strengthening to be able to

manage REDD. Sixteen of twenty respondents believed that

the best way to minimize mismanagement of funds and

encourage participation in the scheme would be bypassing

FECONA, distributing money to the community president or

directly to the families. Most supported payments directly to

families. Furthermore, there is the sense that it is the

bureaucrats, NGO officials and consultants that benefit most

from projects such as these, while community members are

often burdened with risk, debt and wasted effort if the

projects fail.

The dominant concern expressed was that REDD would

generate conflict among the families if individuals faltered

in compliance, with the loggers being the principal actors

expected not to comply. One community member com-

mented that the real issue was with the government

institutions and their inability to enforce the law. Another

commented that conservation efforts really needed to be

directed at reforming INRENA, the National Institute of

Natural Resources. INRENA used to be in charge of

controlling illegal logging, but some INRENA officials were

considered to have been corrupted by loggers and mer-

chants. While INRENA has been abolished and its functions

have now been divided between the Ministry of the

Environment and regional governments, the general point

made remains valid.

Many community members supported the mission of the

ACR-AA and its conservation and watershed protection goals

namely supporting the idea of protecting environmental

services. But opinions are mixed about the specific benefits,

ranging from full support to antagonism. Negativity stemmed

from a sense of exclusion from the process, which was

ostensibly participatory but in fact exclusionary and not

representative. One community member recounted how the

ACR-AA was approved by a handful of FECONA leaders (the

‘‘community representatives’’) in a closed-door meeting with

an NGO technician and departmental official (the other

‘‘stakeholders’’ in the ACR-AA process). Resentment also

emerged from fear at being denied access to the natural

resources in the ACR-AA vital to their livelihoods, including

illegal logging and fishing. New ACR-AA restrictions would

hamper these activities.

Aside from watershed protection, much uncertainty and

anxiety reined about how the communities would benefit

from the ACR-AA regime. The intentions of the regional

government in establishing the ACR-AA do not align with the

provision of clear benefits to communities.

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

4.4. Hope for the future

The future scenarios created by the people of the Pucaurquil-

los provided insights into the nuanced, ambiguous opinions

and hopes of community members with respect to desirable

outcomes for themselves and their forest. They grasp the scale

of natural resource and ecosystem degradation; they appreci-

ate that the future of the community is tightly linked to the

health of the forest and river. The young people perceive that

without the forest, there is little future for them in their forest

villages. Yet they feel powerless because of the roles of more

powerful actors—businessmen, loggers and regional govern-

ment—who exert control over their livelihoods, forest and

future, expressed through the new ACR-AA.

The people of the two Pucaurquillos are hopeful that the

communities can be empowered to take control of their

natural surroundings, manage them effectively for the benefit

of the community and ensure the long-term sustainability and

health of the forest. Clear threats to this future include elite

capture, corruption among community leaders, conflict, and

continued degradation by outsiders in spite of attempts at

control.

5. Discussion: analyzing dynamic REDDsystems

5.1. Local narratives versus regional and globalassumptions

When the local narratives and views are related to national

and global narratives, discrepancies become evident. Potential

payments based on estimations (see Appendix) exceed what

respondents said would be necessary to encourage conserva-

tion. These payments could be expected to provide incentives

to conserve forests and engage in reforestation projects. But,

as our findings suggest, they would not meet all communal

expectations.

The causes of forest degradation are not just local

livelihood demands, but the collision of local needs with

global markets and government policy within a context of

poor enforcement and weak governance at all levels. These

multiple level linkages are not likely to disappear when REDD

schemes become implemented. For some community mem-

bers, illicit and sporadic logging, while dangerous and

unreliable work, offers a pathway to new opportunities to

generate cash for children’s schooling. Thus community

members engage in or facilitate logging, but outside influences

generate demand and regional and national governments are

largely unable or unwilling to stop it. Community members

also continue to impact forested areas outside of their tenured

lands, areas they have traditionally hunted, fished and logged,

as demonstrated by their active participation in logging in the

ACR-AA. It is unclear at present whether REDD could offer

incentives to discourage logging in the ACR-AA by community

members.

The illegal logging issue in Peru is one example of regional-

level elements of the dynamic climate change/REDD system

that are linked to local and global levels, but which are also

shaped by their own drivers, largely unconnected to local

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x 7

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

drivers. The particular example of illegal logging also

demonstrates the vagaries and uncertainties that may

influence the implementation of REDD schemes in locations

similar to the Ampiyacu-Apayacu river basin. Another exam-

ple relates to the possibility that REDD benefits from carbon

schemes in the area would flow to government departments

and thus further restrict pathways out of poverty for residents

through limiting access to resources and exacerbating lack of

trust in government (MINAM, 2011).

5.2. Social and human capital challenges

While adequate economic incentives for carbon saving forest

conservation can be anticipated, uncertainties remain with

regard to communally owned resource management, as

evidenced in our case study by current practices related to

collective land tenure arrangements, communal management

of the electricity network, and use rules for chambira, a wild-

grown palm used in handicrafts. In the entire Ampiyacu-

Apayacu river basin, there is a prevailing lack of trust in

leaders, community members and institutions, particularly

FECONA. Transparency is key and conflict is inevitable, and

determining how conflicts will be managed is certain to be an

important step for any REDD-type initiative at the community

level. REDD is not just an environmental and financial

mechanism involving resource stocks; it will also have

significant social consequences. Implementing REDD effec-

tively in common-pool resource regimes requires strong social

capital (Putnam, 2000), which receives little attention in

national and global narratives on REDD. The problem of weak

governance, poor enforcement and susceptibility to outside

influences are thus significant. Will providing payments to

communal landholders such as these forest communities, in

such a fragile, untrustworthy governance regime, work to

protect forests and mitigate carbon emissions, or its converse?

The region could easily become a target area for other forms of

resource extraction, market demand and land conversion,

such as soybean growers from Brazil, or coca for the global

drug trade.

Closely related, a key element for any REDD scheme

success is benefit sharing. Ampiyacu-Apayacu residents

would expect a transparent program of conditional cash

transfers directly to families as well as projects that

strengthen the community and create jobs. Community

members, furthermore, hope that REDD might initiate effec-

tive capacity-building within the community. Interests in

training workshops about forest management, mapping,

monitoring and administration were mentioned several times

in the interviews. Training young people and creating jobs for

them was a frequent theme; REDD schemes should provide

opportunities for young people so that they do not have to

leave the community to find their future. REDD, if carefully

constructed and adapted to community realities, should

strengthen local community capital, challenge local institu-

tions, provide investments in an education fund and support

local reforestation efforts.

In summary, our research reveals a preference for the

creation of a diversified REDD-centered economic sector, with

multiple opportunities for employment and income-genera-

tion for community members at many levels, within the

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

community and beyond. Throughout the process, flexibility,

resilience and participation are key characteristics that should

be maintained. However, rather than the ‘‘win-win-win’’ of

climate change mitigation, conservation and poverty allevia-

tion, the result of REDD intersecting with regional conserva-

tion politics, community dynamics and global demand is likely

to create winners and losers at different levels. The Pucaur-

quillos villagers, in our case study, similar to many other local

forest users who will be subjected to REDD projects, are

unlikely to be all-around winners. Their forest holdings are

small in comparison to the land they currently access for

resources. The deforestation risk to the forest is relatively low,

meaning lower REDD payouts. The ACR-AA theoretically could

be a big winner, since it is a large area, and the regional

government is looking for income to manage it. It is unclear,

however, how the ACR-AA will benefit communities. There is

resentment that the ACR-AA land was not titled to the

communities, and it is perceived by some as a land grab by the

Loreto regional government. While the communities are

officially the ‘‘primary beneficiaries’’, the regional government

has rights and control of the ACR-AA.

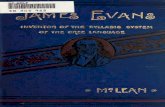

Hence, local level narratives (forests, livelihoods, and

pathways out of poverty) are currently connected by only a

narrow channel of communication with national and global

narratives. The hourglass in Fig. 1 captures this bottleneck of

dialog and the different actors participating in these distinct

narratives. The distances are great—geographically, but also

in terms of the understanding of the problems and possible

solutions—when perspectives are limited to economics and

carbon.

6. Conclusions: appreciating local narrativeson REDD

While REDD designers acknowledge the spatial and temporal

complexities of their endeavor, they construct models based

on assumptions that are intended to apply to multiple

countries well into the future. Forest, people and livelihoods,

in all of their diversity at different levels and different time

horizons are transformed into global representations of local

populations, hectares of forest, tons of carbon and dollars.

Considering the multiple actors, levels and dynamics of REDD,

it becomes clear that distinctively different narratives will

apply in different locations. Communities that are expected to

become important actors in the implementation of the REDD

program are themselves complex, diverse, dynamic networks

of peoples, connected to other networks, interacting with the

landscape of the forest ecosystem in a multitude of ways.

To a degree, the global narrative on REDD does acknowl-

edge uncertainty through national programs, and flexibility

exists in the application of REDD programs to meet local

needs. The importance of communities, the risks they face

and the need for REDD to offer multiple benefits is recognized.

REDD designers, however, risk simplifying too early, of

averaging, compiling and transforming the thousands

of dynamic systems that reflect communities and their

intersection with government and international actors into

misleadingly simple curves, charts and trends. Currently

governments, NGOs, fund managers, consultants and large

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

UNFCCC

UN-REDD PROGRAMME

World Bank FCPFNorway

European Climate Exchange EDFCIFORNational

Governments

NGOs

Indigenous RightsOrganizationsCERs CDM

Kyoto Protocol

Carbon markets

Safeguards

Dollars

Tons of carbon

REDD+

Opportunitycosts

Nationalbaselines

WWFTNCMonitoring

verification reporting

Market-based Fund-based

Creating jobs

Paying school fees

NGOs

FECONA

IBC

Health clinic

Curaca Artisans

Tourists

Loggers

Timber merchants

ACRReforestation

Improved forest

Clean air and water

Community president

Families

Illegal logging

Future of community

Lots of children

20 celsius

Debts

Conflict

Adminstrative capacity

Trust

global narrative

local narrativePopulation changes

Actors in blackConcepts in gray

Pro-poor

The debate must be broadened outand opened up tomerge the global

and local narratives.

Chambira FishingFarmers

Communities

Coca

Fig. 1 – Bottlenecks in global and local narratives.

Source: the authors.

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x8

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

landholders are those who best understand the discussions

about REDD and how it will eventually be implemented. This

knowledge will influence who will capture the benefits when

they materialize. The rural communities are at a severe

disadvantage in this respect.

We also struggled with the difficulties of translating

REDD—a complex and evolving international initiative—in a

readily comprehensible way to local people. Our research has

revealed local narratives in only two communities of the many

thousands that may eventually participate in REDD. However,

we believe that the limitations under which we worked

actually highlight the tremendous challenge of applying a

highly technical top-down policy to the highly variable micro-

contexts of tropical forests. These same challenges will have

to be met by REDD projects elsewhere. More outreach and

more research are needed.

By embracing diverse narratives and mirroring the

dynamic forest-human systems that it attempts to frame,

REDD has a better chance of connecting incentives and

benefits with forest conservation to approach the desired

‘‘win-win-win’’ of conservation, climate change mitiga-

tion and poverty alleviation. Revealing local narratives

about REDD broaden out and open up the REDD narrative

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

beyond the economics-centered and policy-focused nar-

ratives that have dominated REDD development to date.

The key step is involving local actors and reflecting the

larger values at stake: not just carbon, but forests; not just

market-based solutions, but resilient and adaptive local

livelihoods that tackle the dynamics of poverty and

exclusion; not just lack of data or technical knowledge,

but gaps in trust. Future scenarios, community forums,

citizen’s juries and other participatory planning methods

can break down distances and pull community members’

knowledge, hopes and perspectives into the heart of the

REDD design process. A collaborative approach to REDD

design that embraces local narratives will be more likely

to generate the multiple benefits of healthy forests, strong

communities and, ultimately, national and global climate

change mitigation.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the commu-

nities of the Ampiyacu-Apayacu, El Instituto del Bien

Comu n, Jomber Chota, the Stone Center for Latin

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

.10

yea

rp

ay

men

to

n

iced

per

ton

of

Meth

od

2.

Op

po

rtu

nit

yco

sts,

10

yea

rp

ay

men

to

np

er

hect

are

ba

sis

Meth

od

3.

Op

po

rtu

nit

yco

sts,

10

yea

rp

ay

men

to

na

per

ton

of

carb

on

ba

sis

Co

nse

rva

nd

oJu

nto

s

ty

Pa

ym

en

t

per

fam

ily

per

yea

r

Pa

ym

en

tto

the

com

mu

nit

y

per

yea

r

Pa

ym

en

t

per

fam

ily

per

yea

r

Pa

ym

en

tt

oth

e

com

mu

nit

y

per

yea

r

Pa

ym

en

t

per

fam

ily

per

yea

r

Pa

ym

en

tt

oth

eco

mm

un

ity

per

yea

r

Pa

ym

en

tp

er

fam

ily

per

yea

r

$2007

$366,2

43

$5813

$177,4

75

$2817

$5924

$94

$1495

$281,4

67

$4330

$136,3

94

$2098

$4553

$70

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x 9

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

American Studies, Sven Wunder, Dennis del Castillo and

Martin Mendoza. We also thank two anonymous

reviewers for their constructive criticism of earlier drafts

of the paper.

Appendix A. Estimates of REDD payments tocommunities

Below are estimates of REDD payments to the communities

studied based on projections by Armas et al. (2009). Data are

presented per community and per family for illustrative

purposes. According to input from community members

interviewed, the preferred actual distribution of benefits

within communities could take various forms, including

payments directly to families, investment in community

projects, or a mixture of both.

A.1. Assumptions

Peruvian soles US$

Opportunity cost per ha

in Pebas,7 in soles

(Armas et al., 2009)

S/. 8327.00 $2914.45

Opportunity cost per ton of

carbon in Pebas, in soles

(Armas et al., 2009)

S/. 15.64 $5.47

1 sol = 0.35 US$.

Community Number of

families

Total

area

(ha)

Estimated

high

forest (80%)

Carbon/

ha8

Boras de

Pucaurquillo

63 2244.01 1795.21 258

Huitotos de

Pucaurquillo

65 1724.58 1379.66 258

A.2. Calculations

Estimated REDD payments based on three possible

REDD methods for calculating payments, plus Conservando

Juntos.

Co

mm

un

ity

Meth

od

1

afi

xed

pr

carb

on

9

Pa

ym

en

t

toth

e

com

mu

ni

per

yea

r

Bo

ras

de

Pu

cau

rqu

illo

$126,4

44

Hu

ito

tos

de

Pu

cau

rqu

illo

$97,1

75

7 The communities are located in the municipality of Pebas.Armas et al. (2009) estimate opportunity costs based on munici-pality.

8 The total carbon per hectare is calculated based on the esti-mate provided by Armas et al. (2009) of 260 tons/ha for the de-partment of Loreto, minus an estimated seven cubic meters perha, that is, typically lost through high-grading for commercialtimber (CATIE, 2007), at 0.25 tons of carbon per cubic meter (Green-spirit, 2011), to arrive at an estimated 258 tons/ha.

9 Payments for Methods 1, 2 and 3 represent 70% of the totalcalculated value, assuming that 20% of total costs will be go toproject implementers and 10% to government, leaving 70% tocommunities, following projections by FCPF (2010).

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narratives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x10

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

r e f e r e n c e s

AIDESEP, 2011. Analisis y propuestas indigenas sobre el RPP (3aversion) del REDD Peru. http://www.redd-monitor.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Analisis-AIDESEP-sobre-RPP3-Per%C3%BA-21.2.2011.pdf (accessed 28.11.12).

Angelsen, A. (Ed.), 2009. Realising REDD+: National Strategiesand Policy Options. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia.

Armas, A., Borner, J., Tito, M., Dıaz, L., Tapia-Coral, S.C.,Wunder, S., Reymond, L., Nascimento, N., 2009. Pagos porservicios ambientales para la conservacion de bosques en laAmazonıa peruana: Un analisis de viabilidad. SERNANP,Lima, Peru , 92 pp.

Arnouts, R., 2010. Regional nature governance in theNetherlands; four decades of governance modes and shiftsin the Utrechtse Heuvelrug and Midden-Brabant.Dissertation. Wageningen University, Netherlands.

Brewer, G.D., 2007. Inventing the future: scenarios, imagination,mastery and control. Sustainability Science 2,159–177.

Cano, W., 2012. Formal Institutions, Local Arrangements andConflicts in the Northern Bolvia Communities after ForestGovernance Reforms. PROMAB Scientific Series,Wageningen, Netherlands.

CATIE, 2007. Estado actual de los bosques de produccion encuatro paises amazonicos. Revista Recursos Naturales yAmbiente No. 49-50. CATIE, San Jose, Costa Rica.

de Jong, W., Borner, J., Pacheco, P., Pokorny, B., Sabogal, C.,Benneker, C., Cano, W., Cornejo, C., Evans, K., Ruiz, S.,Zenteno, M., 2010. Amazon forests at the crossroads:pressures, responses, and challenges. In: Alfaro, R.,Kanninen, M., Lobovikov, M., Mery, G., Swallow, B., Varjo, J.(Eds.), Future of Forests – Responding to Global Changes.IUFRO, Vienna, Austria, pp. 283–298.

Denevan, W.M., Padoch, C. (Eds.), 1987. Swidden-FallowAgroforestry in the Peruvian Amazon. Advances inEconomic Botany, vol. 5. Botanical Garden, New York.

El Peruano, 2011. Empresa Peruana de Servicios Editoriales. S.A.Lima, Peru. http://www.elperuano.pe/Edicion/ (accessed07.12.12).

Evans, K., June 2010. Report of REDD Fieldwork. IBC, Iquitos,Peru.

Evans, K., Velarde, S.J., Prieto, R.P., Rao, S.N., Sertzen, S., Davila,K., Cronkleton, P., de Jong, W., 2006. Field guide to the future:four ways for communities to think ahead. In: CIFOR, ASBsystem-wide program of the Consultative Group onInternational Agricultural Research. ICRAF, Secretariat of theMillennium Ecosystem Assessment, Nairobi, Kenya.

Evans, K., de Jong, W., Cronkleton, P., 2008. Future scenarios as atool for collaboration in forest communities. Surveys andPerspectives Integrating Environment and Society 1, 97–103.

Evans, K., de Jong, W., Cronkleton, P., 2010. Participatorymethods for planning the future in forest communities.Society and Natural Resources 23, 1–16.

FAO, 2011. State of the World’s Forests 2011. Food andAgriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

FCPF, 2010. Global dialogues on R-PP preparation. Presentationon August 13-14 2009 at Grupo-REDD Peru. World Bank,Washington DC, USA.

Gluck, B., Angelsen, A., Appelstrand, M., Assembe-Mvondo, S.,Auld, G., Hogl, K., 2010. Core components of theinternational forest regime complex. In: Rayner, J., Buck,A., Katila, P. (Eds.), Embracing Complexity: Meeting theChallenges of International Forest Governance. A GlobalAssessment Report. Prepared by the Global Forest ExpertPanel on the International Forest Regime. IUFRO WorldSeries, vol. 28. IUFRO, Vienna, Austria.

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

Greenspirit. 2011. Web site. Accessed 31-March-2011.www.greenspirit.com.

Hajer, M.A., Versteeg, W., 2005. A decade of discourse analysisof environmental politics: Achievements, challenges,perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 7(3), 175–184.

Hiraldo, R., Tanner, T., 2011. The Global Political Economy ofREDD+: Engaging Social Dimensions in the Emerging GreenEconomy. UNRISD Publications No. 4In: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/(LookupAllDocumentsByUNID)/B0B96C3130210583C12579760057FA24?OpenDocument(accessed 07.12.12).

IBC, 2010. Instituto Bien Comun. In: http://www.ibcperu.org(accessed 10.05.10).

IPCC, 2007. Climate Change 2007, the IPCC Fourth AssessmentReport. International Panel on Climate Change, Geneva,Switzerland.

Leach, M., Scoones, I., Stirling, A., 2010. DynamicSustainabilities: Technology Environment, Social Justice.Earthscan, London, UK.

Lovera, S., 2008. The Hottest REDD Issues: Rights, Equity,Development, Deforestation and Governance by IndigenousPeoples and Local Communities. Briefing Note, IUCN. In:http://www.rightsandresources.org/publication_details.php?publicationID=904 (accessed07.12.12).

Lynam, T., de Jong, W., Sheil, D., Kusumanto, T., Evans, K., 2007.A review of tools for incorporating community knowledge,preferences, and values into decision making in naturalresources management. Ecology and Society 12 (1), In: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art5/.

MINAM, 2011. Ley que regula la compensacion de los serviciosambientales. Ministerio del Ambiente, Lima, Peru.

Murdiyarso, D., Brockhaus, M., Sunderlin, W.D., Verchot, L.,2012. Some lessons learned from the first generation ofREDD+ activities. Current Opinion in EnvironmentalSustainability 4 (6), 678–685.

Peskett, L., Huberman, D., Bowen-Jones, E., Edwards, G., Brown,J., 2008. Making REDD Work for the Poor. Prepared for thePoverty Environment Partnership. In: http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/making_redd_work_for_the_poor_final_draft_0110.pdf(accessed 07.12.12).

Peterson, G.D., Cumming, G.S., Carpenter, S.R., 2003a. Scenarioplanning: a tool for conservation in an uncertain world.Conservation Ecology 17, 358–366.

Peterson, G.D., Beard Jr., T.D., Beisner, B.E., Bennett, E.M.,Carpenter, S.R., Cumming, G.S., Dent, C.L., Havlicek, T.D.,2003b. Assessing future ecosystem services: a case study ofthe Northern Highlands Lake District, Wisconsin.Conservation Ecology 7 (3), In: http://www.consecol.org/vol7/iss3/art1/.

Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (PFII), 2010. TheCopenhagen Results on the UNFCCC; Implications forIndigenous Peoples’ Local Adaptation and MitigationMeasures. In: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/E.C.19.2010.18 EN.pdf (accessed 07.12.12).

Pokorny, B., Scholz, I., de Jong, W., forthcoming. REDD+ for thepoor or the poor for REDD+? About the limitations ofenvironmental policies in the Amazon and the potential ofachieving environmental goals through pro poor policies.

Putnam, R.D., 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival ofAmerican Community. Simon & Schuster, New York City,USA.

Skutsch, M., McCall, M.K., 2011. Why community forestmonitoring? In: Community Forest Monitoring for theCarbon Market: Opportunities under REDD, Earthscan,London, UK.

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y x x x ( 2 0 1 3 ) x x x – x x x 11

ENVSCI-1163; No. of Pages 11

Stern, N., 2006. Economics of Climate Change. Office of theExchequer, London, UK.

Sunderlin, W., Angelsen, A., Belcher, B., Burgers, P., Nasi, R.,Wunder, W., 2005. Livelihoods, forests, and conservation indeveloping countries: an overview. World Development 33(9), 1383–1402.

UN-REDD, 2011. United Nations REDD Programme. In: http://www.un-redd.org/ (accessed 03.04.11).

van der Heijden, K., 1996. Scenarios: The Art of StrategicConversation. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA.

White, A., Martin, A., 2002. Who Owns the World’s Forests?Forest Trends, Washington, DC, USA.

Please cite this article in press as: Evans, K., et al., Global versus local narr(2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.013

Wollenberg, E., Springate-Baginski, O., December 2009.Incentives + How Can REDD Improve Well-being in ForestCommunities?. InfoBrief No. 21. Center for InternationalForestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia.

Wollenberg, E., Edmunds, D., Buck, L., 2000. AnticipatingChange: Scenarios as a Tool for Adaptive ForestManagement. Centre for International Forestry Research,Bogor, Indonesia.

Wunder, S., 2009. Can payments for environmental servicesreduce deforestation and forest degradation? In: Angelsen, A.(Ed.), Realising REDD+: National Strategies and Policy Options.Centre for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia.

atives of REDD: A case study from Peru’s Amazon. Environ. Sci. Policy