Enlil and Namzitarra Cohen in RA 104

Transcript of Enlil and Namzitarra Cohen in RA 104

[RA 104-2010]

Revue d’Assyriologie, volume CIV (2010), p. 87-97

87

‘ENLIL AND NAMZITARRA’: THE EMAR AND UGARIT MANUSCRIPTS AND A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF THE ‘VANITY THEME’ SPEECH

BY Yoram COHEN

The composition ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’ is represented by seven Old Babylonian Sumerian manuscripts.1 From the so-called western periphery and of a later date come manuscripts from Emar and Ugarit.2 In Emar, several disparate pieces, written in the so-called Syro-Hittite script, probably originally made up one single manuscript. In Ugarit, all that remains of the composition is a fragment; its contribution lies in that it provides the Akkadian translation of parallel lines of the Emar manuscript which are missing. Both the Emar and Ugarit manuscripts represent the bi-lingual stage of the composition which saw the translation into Akkadian, and expansion of the Old Babylonian Sumerian version. Two strophes of the Old Babylonian Sumerian Version (ll. 20-21) dealing with the well-known ‘vanity theme’ were developed into a longer section which led the composition to its near end.3 In addition, the Emar manuscript carries an ill-preserved Akkadian wisdom composition, following the end of ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’, spreading over both the left and right columns of the tablet.

The aim of this brief study is twofold: to present the arrangement of the Emar manuscript and consider its relationship to the Ugarit manuscript; and to offer a new interpretation of the ‘vanity theme’ speech contained within the composition. We will argue that contrary to what is claimed, the ‘vanity theme’ speech is delivered by Namzitarra and not Enlil. We begin first by presenting the peripheral manuscripts and include a brief commentary to explicate our readings.

The Emar and Ugarit Manuscripts

Upon reviewing Arnaud’s edition of the composition from Emar, Civil (1989: 7) made some important contributions by correctly ordering the fragments of the Emar tablet and by including an additional piece to Arnaud’s edition. Following Civil, the Emar fragments are: Emar 773 (Msk 74238l), Emar 592 (Msk 74112b), Emar 771 (Msk 74174a), Emar 774 (Msk 74182a), and probably Emar 772 (Msk 74148r), which cannot be confidently placed.4 While Civil’s comments have been acknowledged in subsequent editions of the piece (Alster 2005: 336-338; Kämmerer 1998: 222-227), to my knowledge no full attempt to integrate his finds has been

1. Civil 1974-1977; Kämmerer 1998: 218-221; Alster 2005: 327-335; ETCSL, 5.7.1. See also the discussionsof Vanstiphout 1980; Lambert 1989; Klein 1990.

2. Arnaud 1985-1987: 367-371; id. 2007: 140-141. Numeration follows Alster 2005: 327-338. Editions of theEmar compositions were given by Klein 1990; Kämmerer 1998: 222-227; Alster 2005: 336-338.

3. We follow here the terminology provided by Alster 2005 for this type of wisdom discourse.

4. Kämmerer 1998: 226, n. 479, following Arnaud’s suggestion, considers Emar 772 to be a duplicate of themain manuscript, but that is not certain.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

pp. 87-97

YORAM COHEN [RA 10488

made. Therefore, our understanding of the relation of the fragments to one another and the overall implication regarding the length of the text when complete has been lacking.5 The correct ordering of the fragments also assists to improve the reading of the Ugarit fragment and solve some textual cruxes. As such it is worthwhile first to present the Emar tablet on the basis of Civil’s ordering and placement of the fragments.6 The tablet is schematically visualized in fig. 1.

Fig. 1: ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’—The Emar Tablet (top: obverse; bottom: reverse)

The reverse of Emar 771, which represents a complete tablet, as far as the left column is concerned, has a total twenty-five lines (not including the edge). The obverse of the tablet, Emar 773 (+) 592 carries eight lines and Emar 771 (+) has sixteen lines, resulting in a total of twenty-four lines. This means that one to two lines are lost in the gap between Emar 773 (+) and Emar 771 (+). The raven episode and ‘Enmešarra myth’, suspected to have been missing from the Emar version, were probably contained between this one to two lines gap and down through the almost completely lost seven lines of Emar 771 obv. (0´-6´), hence a total of eight to nine lines. In the Old Babylonian Sumerian version, the raven episode and the ‘Enmešarra myth’ span seven lines (ll. 12-18).

The edge of the tablet (Emar 771 rev.) contains the very end of the Akkadian wisdom literature composition (and is not the continuation of the left column, but follows the right column, the end of which is lost). It runs on, as Civil already had correctly noted, to the fragment Emar 773. The colophon, which is missing, would have probably been present on the right-hand side of the edge or the lower half of Emar 771 rev. With this ordering of the Emar fragments, we can compare both the Emar and Ugarit manuscript.

5. See the table which served as our starting point in Klein 1990: 66, n. 23.

6. See also the important remarks by Cooper 2011: 42.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

2010] ‘ENLIL AND NAMZITARRA’: THE EMAR AND UGARIT MANUSCRIPTS… 89

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

(rea

d m

u-tá

l)

YORAM COHEN [RA 10490

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

2010] ‘ENLIL AND NAMZITARRA’: THE EMAR AND UGARIT MANUSCRIPTS… 91

COMMENTS ON INDIVIDUAL LINES

Emar 773 (+) Emar 592

3´: mu-tal[…] = mu-zal-le of the Old Babylonian version; see Civil 1989: 7. 4´: Cf. me-ta = ayyānu, ‘where’, CAD/A 1: 226-227. 5´: Cf. [gudu4.ba]l.lá.gub.ba = ša man-za-al-ti, Lu iv 75, cited in CAD/M 1: 228, sub manzaltu, ‘office’, ‘station’. 6´: Consider a syllabic spelling [gu]-du for gudu4, or restore [ì]-gub-[bu-nam] according to the Old Babylonian version, l. 6 ; cf. ki = ašar, CAD/A 2: 456, sub ašru. (7´): Restored according to Emar 771 rev. 27´; cf. the Old Babylonian version, l. 7. (8´): The restoration šu[ḫmuṭāku], ‘I am burning’, ‘I am in a rush’, is of course tentative; it is based on the Old Babylonian version, l. 9: gìr-mu u4 táb-táb ‘I am in a hurry’ and Emar 771, rev. 28´: u4 gìr-mu ub-bi (which seems an attempt to convey the same meaning, although corrupt); see the remarks of Civil 1974-1977: 70 and id., 1989: 7.

Emar 771 obv. (+) Emar 774

7´: The Akkadian ⸢dEn⸣-líl at-t[a…] ( ) proves that the Sumerian den-líl-me-en (l. 22 in the Old Babylonian version) is the second person singular, hence this line is spoken by Namzitarra. See the discussion below. 8´: Restoring [mu-zal-le] in Kämmerer 1998: 222 and Alster 2005: 336 is incorrect according to Civil’s ordering of manuscripts; see 3´ above and Cooper 2011: 42.

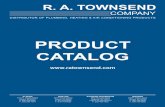

Fig. 2: RS 22.341+28.53a (following Arnaud 2007, pl. 22)

The Ugarit Manuscript (RS 22.341+28.53a; see fig. 2)

1´-2´: Arnaud 2007: 39-40; 140-141 considered the arrangement of the Ugarit manuscript different than the Emar version. In light of our reconstruction, however, this view cannot be withheld. See below. 1´: Arnaud read here [ki-ma i]-na [u4]-um ša-t[e], corresponding to the Old Babylonian version, l. 18. However, given our comparison of the manuscripts, and on the base of the Ugarit copy, we read here […] šu-um-ka! n[am!-zi-tar-ra]. The nam- sign in nam-zi-tar-ra is not well written, but no other option comes to mind. 2´: Arnaud reads [makkūr]-ka pu!-ga!-ku (presumably from the Assyrian puāgu ‘to acquire’, ‘to control by force’), corresponding, in his opinion, to the Old Babylonian version, l. 18.7 But reading with the signs of the copy, we suggest [namtarri]-ka ⸢li⸣-šimx(šam)-ku → liššīmku (N Stem of šâmu ‘to allot, decree’+ 2nd person Sg. dative suffix) ‘May your [fate] be allotted for you’ corresponding to [nam]-zu ḫi-ib-[tar-re] (Emar 771 obv. 11´) and nam-zu ḫé-tar-re (Old Babylonian version, l. 25). Read here šam=šimx. In this period and area the value of the vowel in many

7. Arnaud 2007: 140: [Comme e]n ce [j]our, j’ai ravi [ton trésor]. The Sumerian reads: u4-dè en-gim nam ga-zu-e-še. According to most commentators, this line means (whatever the case for the lost Akkadian), ‘Now I shall surely know the fates, like a lord’; see Alster 2005: 335 with references. Vanstiphout 1980: 67 offers ‘That day, I surely know this/you.’

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

YORAM COHEN [RA 104

92

CVC signs was variable; see Huehnergard 1989: 28-29 and 30-31. The value ú = šam is found in Mesopotamian scholarly texts from Ugarit (a lexical list and a Lamaštu incantation; see Huehnergard 1989: 381, no. 318). Less probable, but also possible is to read the verb liššamku with an unexpected theme vowel (/a/ instead of /i/), a phenomenon often seen in both peripheral and contemporary texts from Babylonia; see Huehnergard 1989: 119-120. 3´-5´: We take lu to be affirmative rather than modal: ‘You will certainly have…’. See discussion below. 7´: The reading of the verb, following Arnaud, is not certain, but the first person pronoun anāku is clear. The personal pronoun appearing after the verb and the plene spelling in ]ka-a strongly imply that the clause is interrogative. The reading of [ayi]ka by Arnaud fits the traces, although the interrogative pronoun is not known to equal me-šè (preserved in the Emar version only). Regarding the speaker of this and the following lines, see the discussion below. 8´: Following Arnaud’s reading; the verb kapāpu ‘to bend, curve’ equals gúr (GAM). Although the exact sense of [ūmī] amēlutti ⸢ikpupū⸣, ‘[the days] of mankind are bending, declining’ remains allusive, the overall meaning is clear from the context. 12´: The Ugarit manuscript has one additional li-im-ṭì, prompting us to restore [ūmī amēlutti] limṭi ‘[the days of mankind] will diminish’.

Emar 771 edge (+) Emar 773

42´-43´: These lines represent the end of the Akkadian wisdom literature composition (not given here), found on the left edge of Emar 771 and joined with the first line of Emar 773, as Civil 1989 already saw.

The ‘Vanity Theme’ Speech in ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’

Having presented and commented on both the Emar and Ugarit manuscripts, we are in a better position to consider the following issue.

Virtually all translators and commentators of this text, whether be it the Old Babylonian or the Emar version, have taken the ‘vanity theme’ speech as Enlil’s words.8 After Namzitarra successfully solves the riddle regarding Enlil’s identity, Enlil grants Namzitarra a fate befitting his name.9 Enlil proclaims the ‘vanity speech’, announcing that material gifts are of no value, because man’s life is fleeting (‘The days of mankind are diminishing…etc.’).10 However, in our understanding, it is Namzitarra and not Enlil who pronounces the ‘vanity theme’. We present our interpretation and proceed to give support for our reading.11

The Old Babylonian Sumerian Version

19 kù ḫé-tuku za ḫé-tuku gud ḫé-tuku udu ḫé-tuku 20 u4 nam-lú-u18-lu al-ku-nu 21 níg-tuku-zu me-šè e-tùm-ma 22 den-líl-me-en nam-mu tar-ra 23 a-ba-àm mu-zu 24 nam-zi-tar-ra mu-mu-um 25 mu-zu-gim nam-zu ḫe-tar-ra (Enlil blesses Namzitarra, after he is recognized through his disguise:) 19 ‘You will have silver, you will have precious stones, you will have cattle, you will have

sheep.’

8. Although see recently Alster 2008: 60 and note 14 below.

9. Vanstiphout 1980.

10. Arnaud 2007: 39-41 sees in the speech Enlil’s recounting or paraphrasing of the curse he had put on mankind since the flood. If so, that would be a first of such an expression issuing forth from the mouth of a god, as far as is known to us. Our reconstruction and understanding of the passage is different, as we will argue in the following discussion.

11. Following the editions and translations provided for by Civil 1974-1977, Alster 2005: 327-338 and Klein 1990, with Arnaud 2007: 140-141 for the Ugarit manuscript.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

2010] ‘ENLIL AND NAMZITARRA’: THE EMAR AND UGARIT MANUSCRIPTS… 93

(To which Namzitarra replies:) 20 ‘The day of mankind is approaching (death), 21 So where does your wealth lead? 22 You are Enlil himself! – then decree my fate!’12

(Enlil responds:) 23 ‘What is your name?’

(And Namzitarra says:) 24 ‘Namzitarra is my name.’

(Enlil decrees that:) 25 ‘Your fate will be allotted like your name!’

The Bi-lingual Version from Emar and Ugarit

Sumerian Column Akkadian Column 7´ den-líl-⸢me-en⸣ nam-tar-[ra…] […] Enlil att[a …] 8´ nam-zi-ta-ra den-lí[l…] […] Namzitarra […] 9´ [a-b]a-àm [mu-zu] […] šumka […] 10´ [nam-z]i-tar-ra mu-mu-[um]

[mu-zu-gim] […N]amzitar[ra…]

11´ [nam]-zu ḫi-ib-[tar-re] […namtarri]ka liššīmku 12´ [o] ḫé-ib-[…] [lost or omitted] 13´ en-na kù.babbar ḫé-tuku [kaspa(m) l]u tīšu 14´ na4 za.gìn ḫé-tuku [uqnî lu] tīšu 15´ gud ḫé-tuku [alpī lu tī]šu 16´ [u]du ḫé-tuku [immerī] lu tīšu 17´ kù.babbar-zu na4 za.gìn-zu gud-zu udu-zu kaspaka uqnîka alpīka immerīka 18´ me-šè al-tùm [ayik]a ⸢alqe⸣ anāku 19´ u4 nam-lú-u18-lu al-gúr-na ūmī amēlutti ⸢ikpupū⸣ 20´ u4-an-na ḫa-ba-lá ūmi ana ūmi limṭi 21´ iti-an-na ḫa-ba-lá arḫi ana arḫi limṭi 22´ mu mu-an-na ḫa-ba-lá šatti ana šatti limṭi 22a´ [u4 nam-lú-u18-lu ḫa-ba-lá] [ūmī amēlutti] limṭi (Ugarit only) 23´ mu 2 šu-ši mu-meš nam-lú-u18-lu 2 šūši šanātu lū ikkib amēlutti pá-la?-ša?

24´ níg-gig-bi ḫi-a25´ ki-u4-ta-ta nam-lú-u18-lu ištu u4-da adi inanna 26´ e!-na ì-in-éš ti-la-e-ni amēluttu balṭu 27´ é-šè gá-e-me-en ina bītia allak 28´ nu-na-an-gub na-an-gub u4 gìr-mu ub-bi

(Namzitarra recognizes Enlil, saying:)

12. Thus Cooper 2011: 41, l. 22, alone among all translations known to me. Cooper’s understanding of –menas ‘you are’, is vindicated by Emar 774, 2´ which reads dEn-líl at-t[a…] = Emar 771 obv., 7´: den-líl-⸢me-en⸣ ; see above.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

kasapka

˹qerbū˺

YORAM COHEN [RA 10494

7´ ‘You are Enlil himself!—[then decree my] fate!’

(not clear) 8´ Namzitarra…Enlil…

(Enlil asks:) 9´ ‘What is [your name?]’

(Namzitarra responds:) 10´ ‘[Namz]itarra is my name.’

(Enlil says:) 11´ ‘Your [fate] will be allotted to you [like your name], 12´ It will be … […], 13´ You will have silver, 14´ You will have lapis lazuli gems, 15´ You will have cattle, 16´ You will have sheep.’

(To which Namzitarra replies:) 18´ ‘[Whe]re will I have taken 17´ Your silver, your lapis lazuli, your sheep? 19´ The days of mankind are declining, 20´ Day after day they are diminishing, 21´ Month after month they are diminishing, 22´ Year after year—they are diminishing, 22a´ [The days of mankind]—they are diminishing (Ugarit only), 23´/24´ 120 years – that is the limit of mankind’s life, its term,13 25´ From that day till now, 26´ as long as mankind has existed. 27´ So I am going home, 28´ Do not stop me, do not stop me, I am in a hurry! (i.e., I don’t have much time left;

Sumerian only).’

In our understanding, in the Old Babylonian version, Namzitarra solves Enlil’s identity (ll. 11-18). Enlil then proceeds to award him with materials gifts (l. 19). Namzitarra rejects them because they are of no lasting value;14 he demands that Enlil, renown for determining the fates, determine his (ll. 20-22). Enlil asks for Namzitarra’s name (l. 23) which he supplies (l. 24). Following that, Enlil assigns him his fate—granting his successors a prebend in his temple (ll. 25-27).15 In the Emar version, the order is slightly changed, as far as we can tell. Apparently Namzitarra recognizes Enlil and asks him to determine his fate (l. 7´). Enlil asks for his name (l. 9´) to which he replies (l. 10´). Enlil assigns him his fate (l. 11´) by providing him with material

13. For this translation of níg-gig = ikkibu, see Cooper 2011: 42, n. 11; Klein 1990 and Alster 2005 prefer‘bane’. For the unclear signs at the end of the line, Klein (personal communication) suggests reading pá-la?-ša? → palâša ‘its (amēluttu, ‘mankind’) term’, which we accept here; see CAD/P: 74.

14. This seems also to be the latest understanding implied by Alster 2008: 60: ‘…in line with good wisdomtradition, Namzitarra was not satisfied with material wealth, but asked for something of lasting value instead…’.

15. On this issue, see Cooper 2011.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

approaching,

2010] ‘ENLIL AND NAMZITARRA’: THE EMAR AND UGARIT MANUSCRIPTS…

95

wealth (ll. 13´-16´) which Namzitarra then rejects through his expanded ‘vanity theme’ speech (ll. 17´-28´).16

There are three compelling reasons that support our new understanding. We will consider these briefly as we move from the general to the specific—the ‘vanity theme’ within the genre of Mesopotamian wisdom literature, parallel thematic constructions in Sumerian literature, and the narrative structure of ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’.17

Having the human hero of our story Namzitarra speak out the ‘vanity theme’ speech in this composition fits well with other articulations of similar themes elsewhere in Mesopotamian wisdom literature.18 The shortness or futility of human life is usually expressed, if not by the poet, then by human figures and not by the gods. Archetypical figures, such as the barmaid Siduri in the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’, or the father instructing his son (as represented in šima milka or the ‘Instructions of Šuruppak’), out of which the figure of the wise man, such as Ziusudra, emerged, are the ones to offer advice on the attainment of a good or proper life in spite of its difficulties and eventual death. Gods determine the fates, as Enlil does in our story (and elsewhere in Mesopotamian sources), but they generally do not impart reflective attitudes concerned with the limit or futility of human life.19 It is Namzitarra as a human who acknowledges the shortness of his life, and therefore, rejects Enlil’s gift.20

Secondly we need to consider the following poetic unit from the ‘Marriage of Martu’, which deals with the same theme and is constructed very much like our speech, as Klein 1990: 59-60 pointed out. We follow Klein’s reading and interpretation of this unit, but demonstrate that it supplies us by way of a parallel construction a good understanding of who the speaker in ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’ is.21 In ‘The Marriage of Martu’, the protagonist of the poem, the god Martu, rejects material gifts from Numušda, his future father-in-law.

16. The differences between the two versions are that in the Emar-Ugarit version 1.) Namzitarra reveals his

name and asks Enlil to determine his fate prior to Enlil’s grant. This causes the entire prebend episode of the Old Babylonian version to be abandoned; and 2.) lines 20 (‘The day of mankind is approaching’) and 21 (‘where does your wealth lead?’) of the Old Babylonian version are interchanged, permitting the development of the vanity theme (Emar-Ugarit version ll. 19´-26´).

17. It should also be noted, in addition to the reasons given below, that with the publication of the Ugarit manuscript, we can see that the Sumerian verb al-tùm (l. 18´) was translated into Akkadian as the first person singular. Regardless of how the verb is to be read (because of the tablet’s sorry state of preservation), the first person pronoun anāku is clear. This requires that we take the list of material goods as the object of the clause, which now translates (ll. 18-17) as, ‘[to whe]re will I have taken your silver, your lapis lazuli, your sheep?’ Moreover, the use of the first person pronoun anāku is not accidental: it may imply the change of speaker in order to supply a contrast with the previous speaker (‘I, on the other hand…’), especially in the case of reported dialogue, where the speakers are not explicitly designated within the narration. This of course is not compulsory and it is a matter of stylistics. Arnaud 2007: 141 and 39 assumes indeed, in line with the customary interpretation of line 18´ of the Old Babylonian version, that the speaker is Enlil, who tells Namzitarra that he might one day remove all of his wealth away.

18. Consider here what Alster 2005: 328 has to say about Enlil’s speech: ‘…is it not rather the scribe who speaks here, promulgating his wisdom?’

19. In ‘Atra-ḫasīs’, it is by Enlil’s command that mankind’s life is curtailed but the gods are not concerned about the futility or vanity of man’s life.

20. Alster 2005: 330 suggested that the final lines of the Emar-Ugarit composition (ll. 27´-28´), which tell of Namzitarra’s departure home, are to be understood metaphorically as the hero’s descent to the netherworld. Such an interpretation, as well as the general tone of the poem, would neatly provide the reason for the inclusion of the Akkadian wisdom composition at the end of the main composition. It deals with the death of the father (Namzitarra himself?) on the one hand and the future of the successors on the other. Klein (personal communication) suggests that the author of the Emar-Ugarit version was interested to end the tale on a pessimistic note, rejecting the end of the Old Babylonian composition (perhaps because its relevance was no longer understood?), in anticipation of the Akkadian wisdom composition which follows. For the Akkadian wisdom composition, see Klein 1990: 60, and 67-68, nn. 26-27; Kämmerer 1998: 224-227. This composition will be treated by the present author elsewhere.

21. Although Klein 1990 drew attention to this comparison, he did not suggest the change of speaker in ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’ as here.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

YORAM COHEN [RA 104

96

dnu-[muš]-da dmar-tu ḫúl-la-e kù m[u-u]n-na-ba-e šu nu-um-ma-gíd-i-dè za [mu-un-n]a-ba-e šu nu-um-ma-gíd-i-dè… [kù-zu me-da-tùm] za-zu me-da-tùm

Numušda, rejoicing over Martu, Presents him with silver – he accepts not, Presents him with (precious) stones – he accepts not… (Says Martu) ‘[Your silver – where does it lead?], your (precious) stones – where do they lead?’22

As Klein correctly understood, Martu would rather marry Numušda’s daughter, the goddess Adgarkidu, than possess such material gains. What good would your (i.e., his future father-in-law’s) gifts be to me, Martu rhetorically asks, if I cannot marry your daughter?

Like in the ‘Marriage of Martu’ where the ‘yours’ (-zu) refers back to the belongings of the previous speaker, and not to Martu’s future gains, in ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’, likewise, ‘yours’ (-zu) refers back to the one who is about to bestow material gains, hence Enlil. What use have I of your (i.e., Enlil’s) material gifts, Namzitarra rhetorically asks, if life itself is short.

In both the ‘Marriage of Martu’ and ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’, the protagonists engage in an eristic debate with the opposite notion (pitted by Numušda and Enlil respectively)—that good fate or success depends on material wealth. This is expressed as a literary trope in the following example:23

níg-gur11 tuku nam-tar-ra [tuku ḫé-me-en] za-e lú kù tuku-bi [ḫé-me-en] za-e lú še tu[ku-bi ḫé-me-en]

‘May you have property, [may you have] a (prosperous) fate, You—[may you] have silver, You—[may you ha]ve grain.’

Material gifts (níg-gur11), which at first glance seem of worth, like a prosperous fate (nam-tar-ra), are rejected by those who know better.24

Finally, in terms of the narrative structure of the plot, our reading represents a common place ploy of many folktales and popular stories. The hero is given a challenge. After overcoming it, he is offered a reward. Wisely, he sees through what it is actually worth and rejects it. He then requests something he deems to be of greater or everlasting value, which he is granted.25 Namzitarra, having seen though Enlil’s disguise as a raven, is offered a reward of riches. He rejects these. In the Old Babylonian version he offers no more than a pithy saying on the passing of human life. In the Emar bi-lingual version, however, he develops the ‘vanity theme’, echoing ideas found elsewhere during this period, like in the ‘Ballad’ and sima milka

22. Following the edition and translation of Klein 1997: 111 and 114-115, ll. 76-82.

23. ‘Dumuzi-Inanna O’, ll. 26-28 = Sefati 1998: 211; ETCSL, 4.08.15. Alster 2005: 335 mentioned this composition, but not that it holds the exact opposite notion which is expressed, for example, in our composition.

24. Other examples of the rejection of wealth in Sumerian literature are supplied by Klein 1990: 66, n. 22, who explores this idea in detail throughout.

25. This narrative structure is echoed in other Sumerian compositions (mentioned by Cooper 2011: 39-40, although this is not to state that he holds the same view about the ‘vanity theme’ speech as us). In ‘Lugalbanda and Anzu’ (ETCSL, 1.8.2.2), Lugalbanda receives blessings from Anzu but he rejects each of them. Anzu then grants him what he desires. Similarly, in ‘Inanna’s Descent’ (ETCSL, 1.4.1), the galatura and the kurgara reject Ereškigal’s offerings of gifts in order to request their wish which is to receive Inanna’s corpse. As Cooper notes, both Anzu and Ereškigal are said to ‘decree destiny’ when presenting their gift.

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.

2010] ‘ENLIL AND NAMZITARRA’: THE EMAR AND UGARIT MANUSCRIPTS…

97

wisdom composition, retrieved in the western periphery sites, but expressing current Babylonian sentiments.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Alster, B. 2005 Wisdom of Ancient Sumer. Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press. 2008 Scribes and Wisdom in Ancient Mesopotamia. In: (Perdue, L.G., ed.) Scribes, Sages, and Seers:

The Sage in the Eastern Mediterranean World (Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments 219). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 47-63.

Arnaud, D. 1985-1987 Recherches au pays d’Aštata: Emar VI: Les textes sumériens et accadiens. Paris: ERC. 2007 Corpus des textes de bibliothèque de Ras Shamra-Ougarit (1936-2000) en sumérien, babylonien

et assyrien (Aula Orientalis Supplementa 23). Barcelona: editorial AUSA. Civil, M. 1974-1977 Enlil and Namzitarra. AfO 25, 65-71. 1989 The Texts from Meskene-Emar. Aula Orientalis 7, 5-25. Cooper, J.S. 2011 Puns and Prebends: The Tale of Enlil and Namzitarra. In: (Heimpel, W. & Frantz-Szabó, G., eds.)

Strings and Threads: A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 39-43.

Huehnergard, J. 1989 The Akkadian of Ugarit (Harvard Semitic Series 34). Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. Klein, J. 1990 The ‘Bane’ of Humanity: A Lifespan of One Hundred Twenty Years. Acta Sumerologica 12, 57-

70. 1997 The God Martu in Sumerian Literature. In: (Finkel, I.L. and Geller, M.J., eds.) Sumerian Gods

and their Representations (Cuneiform Monographs 7). Groningen: Styx, 99-116. Kämmerer, T. R. 1998 Šimâ milka: Induktion und Reception der mittelbabylonischen Dichtung von Ugarit, Emār und

Tell el-Amarna (AOAT 251). Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. Lambert, W.G. 1989 A New Interpretation of Enlil and Namzitarra. Orientalia 58, 508-509. Sefati, Y. 1998 Love Songs in Sumerian Literature: Critical Edition of the Dumuzi-Inanna Songs (Bar Ilan

Studies in Near Eastern Languages and Culture). Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press. Vanstiphout, H.L.J. 1980 Some Notes on ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’. RA 74, 67-71. Postscript : I wish to thank J.S. Cooper for sending me his forthcoming paper on ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’ (now published as Cooper 2011), which provided a source of inspiration for this study. Additional thanks are extended to him as well as to J. Klein and P. Steinkeller for their close reading of my manuscript and their numerous suggestions and improvements of my translations. Responsibility of the contents of this study naturally lies with the author. Abbreviations follow the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary; note in addition, Emar = Arnaud 1985-1987 and ETCSL = http://etcsl.orint.ox.ac.uk. This study was supported by an ISF Grant (no. 621/08, with Prof. Ed Greenstein, Bar Ilan University).

ABSTRACT

This article discusses the Emar and Ugarit manuscripts of the composition ‘Enlil and Namzitarra’. As part of the discussion, it offers a new interpretation of the ‘vanity theme’ speech contained within the composition, arguing that contrary to what is claimed in the literature, this speech is delivered by Namzitarra and not by Enlil.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article examine les manuscrits de ‘Enlil et Namzitarra’ provenant d’Émar et d’Ugarit. Il propose notamment une nouvelle interprétation du discours sur le ‘thème de la vanité’ contenu dans cette composition soutenant que, contrairement à ce qui est affirmé dans la littérature, le discours est prononcé par Namzitarra et non par Enlil.

Dept of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, The Faculty of the Humanities The Gilman Building, Tel Aviv University, 69978 Tel Aviv ISRAEL Yoram Cohen

Doc

umen

t tél

écha

rgé

depu

is w

ww

.cai

rn.in

fo -

-

- 82

.166

.183

.243

- 1

5/06

/201

2 15

h22.

© P

.U.F

. D

ocument téléchargé depuis w

ww

.cairn.info - - - 82.166.183.243 - 15/06/2012 15h22. © P

.U.F

.