Enhancing the role of participatory scenario planning processes: Lessons from Reality Check...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Enhancing the role of participatory scenario planning processes: Lessons from Reality Check...

Enhancing the role of participatory scenario planning processes:Lessons from Reality Check exercises

Arnab Chakraborty *

University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, 611 E. Lorado Taft Drive, M230 TBH MC/619, Champaign, IL 61820, USA

1. Participatory scenario planning – bridging the gap between top-down and bottom-up approaches

The avowed value-neutral comprehensive rational planning for the collective public interest, from the Progressive era on,has often been criticized as serving the interests of civic and business elites while promoting middle-class values to theexclusion of others [1]. A new direction in planning is needed to undo these past harms, by both advocating for marginalizedpopulations and including them in the planning process to create a more equitable society [2–4]. The participatory scenarioplanning process described in this paper attempts to bridge the gap between top-down comprehensive rational planning andempowered advocacy that works from the bottom up [2,5,6].

Planning as a supposedly value-neutral, top-down, rational decision-making process has been shown to be unable to dealwith complex problems involving multiple publics and issues of inequality and injustice. Postmodernist, post-colonial andfeminist critiques of planning have resulted in alternative theoretical frameworks for how planning can occur that offers thepromise of a less exclusionary process. Although the approaches differ in their degree of centralized authority, they share anemphasis on process over outcome and principles of equality.

Different conceptions of the public interest have plagued planning as a profession since its inception during theProgressive era. What was imagined to be a collective public interest was in reality many different and often divergent publicinterests. The failure of planners to recognize this led to a collective loss of faith in planning by the public during the social

Futures 43 (2011) 387–399

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Available online 28 January 2011

A B S T R A C T

This paper critically assesses a series of scenario planning exercises in the Washington

Metropolitan region and the State of Maryland within a broad and evolving framework of

participatory planning. Reality Check, as the exercises were called, were a daylong set of

activities using tools that encouraged stakeholder participation to develop scenarios

focused on long-term regional sustainability. The paper draws upon planning theory,

participant reactions, media reports, post-exercise outcomes and author’s experiences of

shaping the process. It illustrates how the model was adapted to multiple scales and

contexts, and variations in desired technical complexity. The paper concludes that such

processes have an inherent value in capturing the issues of the future and in creating

awareness and knowledge. It argues that certain considerations such as early strategic

engagement of stakeholders, flexibility of technical tools and diversity among organizers,

all played a role in enhancing the dialogue. Furthermore, it suggests that when timed with

favorable external conditions and designed within suitable institutional frameworks, they

have the potential to provide a foundation from which tangible regional benefits can be

realized.

� 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

* Tel.: +1 217 244 8728; fax: +1 217 244 1717.

E-mail address: [email protected].

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Futures

journal homepage: www.e lsev ier .com/ locate / fu tures

0016-3287/$ – see front matter � 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.01.004

unrest of the 1960s. As the heterogeneity of society increases, the ability of planners to address this multiplicity of publicswill become even more important.1 Planning for culturally diverse populations will require planners to move beyond theirreliance on technical-rationality and scientific methods to embrace different ways of knowing that include experiential,intuition and local knowledges [7]. An emphasis on a communicative planning process that empowers the public andencourages real participation can legitimize these other ways of knowing.

While market failures justify the need for planning, it does not necessarily follow that planning needs to be done by professionalplanners alone. The emphasis should be on communicative processes that attempt to implement participatory democracy asmuch as possible while building capacity in the community [8]. Specific approaches can vary from advocacy planning to equityplanning, depending on the context. Both attempt to use traditional planning skills based in the paradigm of technical-rationality,to address socio-economic injustice, with the latter working within the centralized system of public agencies [9].

However, the focus should not be on the outcome alone, but rather on a participatory process that empowers the stakeholdersto navigate the planning process and decide what is in their best interest. It can be argued that advocacy alone does not affectmeaningful change because it serves to ‘‘weaken and even co-opts neighborhood political activists,’’ resulting in incrementalimprovementswhen systematic change is required to redirect development on a more sustainable path [10]. In response, plannersshould serve as advocates, but in the context of a communicative process. Planners should serve as technical advisors, mediatorsand facilitators, helping a community to reach consensus and navigate the public planning bureaucracy, but through the process ofexperiential learning. Although advocacy is needed to address imbalances in power and wealth that limit equal participation in theplanning process, the goal should be to build capacity and remove barriers to effective citizen participation [11].

Planning that merely serves to advance the narrowly defined interests of a vocal civic or business elite will likely be metwith continued skepticism from the general public. However, planning done in the context of participatory democracy withthe goal of a more just and sustainable society has the opportunity to regain legitimacy in the eyes of the many differentpublics it serves. As a process to shape future outcomes by developing strategies to achieve better possibilities, scenarioplanning offers the possibility to realize these goals [11–14]. Scenario planning lies at the intersection of positive andnormative planning theory, using quantitative analysis and modeling to describe current patterns of development andproject viable futures [15]. A scenario planning process attempts to bridge the gap between empowered advocacy andcomprehensive rational planning by utilizing technical tools of the planning professional to empower and engage the publicin the political planning process through imagining a normative future. [16–18]. The broad multi-dimensional nature ofscenario planning generates alternative futures using multiple paths while comparing their outcomes on similar parameters.Quantitative analysis can be used to produce feasibility tests using past data to judge a model’s predictive capacity [19–21].At the same time, qualitative methods are used in a process to engage stakeholders and generate alternative objectives thatare not possible in a purely data-driven system. A process that engages the public and cultivates their interest from earlystages is also more effective at navigating through controversies.

Scenario planning has been applied in a wide variety of situations for some time. Some of the earliest uses of scenarios inplanning situations came with the realization of the ‘‘wicked’’ nature of planning problems and a search for strategies thatdeal with uncertainties of the future [22]. Scenario planning serves this well as it provides a platform for sharing divergentviewpoints in a pluralistic society, and when combined with evolving tools, it helps us develop multiple visions for the futurethat look beyond the traditional limits of scale, time-horizon, and disciplinary and institutional boundaries. These principleshave been used worldwide in many regional planning processes including, Norwegian Long Term Program (NLTP),Sustainable Seattle, Oregon Shines, Metropolitan Tunis, and Envision Utah [23–26]. Some of these were government-led(NLTP) while others were originally public–private partnerships (Envision Utah). Sustainable Seattle started with 70 peoplein 1991 but their effort, with many successes, continues today. The Envision Utah process led to a successful quality growthstrategy that was adopted by the Utah Legislature in 1999 and has since influenced regional and local land use decisions.More recently, advances to computing technologies have made scenario planning more widespread and complex (e.g. LEAMGeoportal and Chicago Go To 2040) and though technology has arguably widened its reach, the effects on scenario planning’sparticipatory ideals are not yet known [27,28].

A complementary field of inquiry is large group intervention (LGI) methodologies. LGIs are applied in large organizationsystems in many sectors to look, collaboratively, at processes and practices. Emery’s Community Search Conferences ofAustralia [29] to Bunker and Alban’s [30] review of cases have demonstrated that a critical mass of participants (from anorganization or community) can use scenario building as a process to move beyond the ‘‘natural tendency’’ to think of thefuture in terms of extrapolation of the past.

In their edited volume, Engaging the Future: forecasts, scenarios, plans and projects, Hopkins and Zapata [31] discuss variouspaths scenario analysis can take to be effective in the planning process. These include devising a process that is inclusive andresult-oriented, understanding the issues and forces for the future of a community or region, generation and effectivecommunication of ideas, and having an implementation mechanism. The historic role of the planning in imagining a utopian

1 Publics refer to groups with divergent, sometimes overlapping, interests with which individuals and communities identify and, during a planning

process, around which they occasionally organize. The notion of multiplicity of publics reflects not just a large range of interests but also individuals’

identification with different publics in connection to different causes. According to the communicative model of planning theory, identification and

inclusion of such publics, especially the non-dominant ones, as stakeholders in a process are a planner’s key challenge behind broadening their power and

enfranchisement.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399388

vision of the future has been discredited by past mistakes and an over reliance on the myth of a unitary public interest [17].Scenario planning in a participatory framework attempts to rebuild this trust by directly engaging with stakeholders andempowering them to affect the direction of future development.

It is within this framework of evolving values of participatory planning that this paper critically assesses a series ofscenario planning exercises. Reality Check, as the exercises were called, were one-day events in the WashingtonMetropolitan region and the State of Maryland that asked participants to focus on long-term regional sustainability. Theprocess around these events involved building coalitions among divergent groups and tools that facilitate dialogue as well ascapture and visualize outcomes. The next sections discuss frameworks of scenario planning, followed by details of eachprocess and its lessons including, author’s experiences in shaping the process, participants’ reactions and media reports,follow-up engagement with stakeholders and tangible outcomes in the post-exercise period. The conclusion sectionsynthesizes lessons for ongoing work especially those that have transferable relevance. Finally, the discussion reflects onconsiderations for planning such as early strategic engagement of stakeholders, flexibility of technical tools and diversityamong organizers, and external conditions in the effectiveness of the exercise.

2. Frameworks for public participation

Post WWII, government led planning efforts in the United States at the federal, state and local levels attempted torevitalize the declining central city. In the process, the urban core of many cities became little more than hollowed outcenters of business with adjacent concentrations of poor minorities or immigrant populations, the middle class having leftthe city for the suburbs [32]. The large-scale displacement of low-income neighborhoods occurred as urban renewalschemes demolished these areas to make space for high rent housing and commercial space, thereby protecting the realestate investments of the business community. The activism of the 1960s was a direct response to these initiatives, with thepublic demanding a greater role in the planning process at the local level [33]. As a result, opportunities for publicparticipation have greatly increased, often with state and federal mandates setting minimum guidelines for participation atthe local, regional and state level [34]. While most mandated participation in the planning process has amounted tocommenting on already developed plans, a participatory scenario planning process presents stakeholders the opportunity todirectly affect the future direction of development in their community. The distinction is a shift from focusing only onplausible futures to the idealized vision of a more sustainable future desired by both planners and stakeholders.

This is accomplished by first imagining a range of plausible futures based on current trends and conditions to understandwhat is uncertain and what is immovable [35]. At the same time, stakeholder values and goals are assessed and their overlapsand differences are used to create a range of desired futures. These two steps do not occur in isolation, with the first intendedto influence the latter. The facts, trends, constraints and issues identified through analysis are presented to and derived fromthe stakeholders to inform the visioning process. A strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis can beused to help identify issues and driving forces. The purpose of the exercise is not to eliminate conflicting goals and objectives,but rather to create clusters that when combined lead to plausible but divergent futures. In the process of developingplausible futures, options for intervention are also identified. These elements of uncertainty can be altered through policychanges to orient development towards one desired future or another. In planning, these interventions can includetraditional policy tools like land use controls, zoning ordinances, infrastructure provisions as well as more innovativeapproaches like financial incentives linked to economic development or public–private partnerships. At the same time,indicators are developed, so that scenarios can be evaluated to determine their impact on quantifiable measures ofsustainable development.

Identifying distinct futures depends on the inclusion of a diverse group of stakeholders with varying opinions aboutpossible outcomes. Although most residents or workers in a region will meet some definition of a stakeholder, projectresources and scale are two of the many factors that limit who is included. For example, Common Ground was a regionalplanning process where organizers conducted meetings across Chicago neighborhoods over three years, and anyone whoattended was heard and was a stakeholder [36]. Such processes are sometimes criticized for their cost, publicity strategiesthat are biased towards dominant groups and potential for ‘‘takeover’’ by a vocal and influential minority [17]. Morestructured and longer running processes, such as Porto Alegre’s landmark participatory budgeting process [37], havemultiple levels of interaction with stakeholders and have been successful, in part, as they are a legislated practice withknown high stakes. In a process designed for shorter interaction period but covering a large region (Fig. 1), stakeholders arechosen to represent a diversity of views and perspectives. Stakeholders should include both public and private interests fromdifferent roles, disciplines, cultures and ethnicities within the target community. Attention should be paid to representationand the inclusion of credible leaders to ensure stakeholders have the capacity to shape policy based on the outcomes of thescenario planning process. Equally important is the selection of the facilitators and technical staff. These should be drawnfrom as many participating agencies as possible to bolster the legitimacy of the process.

The scale of a planning process can range from a local community to a metropolitan region, county or state. The objectiveor mission of the planning process should be agreed upon in advance and will inform both the scale of the endeavor and therange of participants. While in some cases the objective is formation of policies by participant stakeholders to movedevelopment towards some more desired future, in other cases the objective is the dialogue created by the process itself.Depending on the scale, a participatory scenario planning process provides the opportunity to bring together stakeholdersthat would not otherwise interact, creating connections and building capacity for future action.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399 389

After the scenarios and their potential policy interventions are identified, the next step is testing and evaluation todetermine success in moving development towards the desired future. Testing can include application of analytical modelsthat translate characteristics of a scenario into physical changes to development patterns. Klosterman [21] has categorizedtools for scenario analysis (also called planning support systems) on the basis of their technical roles rather than policy focus.He categorizes them as large-scale urban models, rule-based models, state change models, impact assessment models and cellular

automata models. While large-scale urban models have been in use for decades mainly for transportation planning purposes,California Urban Futures (CUF) model [20] was the first GIS-based urban development model.

Many authors have noted that even the most sophisticated and integrated models are not able to incorporate all variablesof interest. Hopkins [38] explains that numerous urban models have been developed, based on different perspectives andtheoretical foundations; some simulate markets for land, housing and labor. Others rely on rules for the likelihood of landconversions from one use to another. Some consider preferences of households and firms based on past behavior withrespect to prices. Others rely on past probabilities of land conversions, and some seek an equilibrium solution. Some aredynamic, usually in discrete time intervals in which actions depend on the results of previous time intervals. Some modeltrip-behaviors given locations, others locate housing based on accessibility.

Regardless of the model used, the goal is to provide feedback to the participant stakeholders so that scenarios and theirinterventions can be revised to align with the desired future outcomes. This iterative process provides stakeholders andpolicy makers with the ability to evaluate the impact of their actions, highlighting unintended consequences and pointing tothe inherent tradeoffs required among participants to achieve the desired future. The next section discusses themanifestations of these principles in the context of our exercises.

3. Developing the process

3.1. Overview

Scenario analysis in some form or another has become an accepted part of many large-scale planning analysis and planmaking processes. Visioning exercises, as a part of scenario analysis, sit at the critical interface where planning processes

[()TD$FIG]

Fig. 1. Reality Check process.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399390

have a true potential for public engagement. However, as the preceding sections demonstrate, several aspects of visioningexercises, including their structure, audience, objectives, etc. influence their outcomes and success. They may draw upon theexperiential knowledge of stakeholders to communicate spatial interdependencies or contain formal planning analysis toconstruct alternative visions with measurable differences;2 yet others seek primarily to promote interaction andunderstanding among stakeholders [17]. In the latter case, their inherent value is in starting a conversation about issuesamong divergent groups and providing a platform to think big picture, appreciate differences and question potentially biasedassumptions in otherwise ‘‘expert’’ driven planning analysis.

Reality Check (RC) exercises were an attempt to develop the foundation and support mechanisms for regional action inmany regions. A study of development of the process helps us assess strategies to select representatives of the public to inviteto participate in such an exercise and challenges to build communication channels among groups with different prioritiesand interests. It also sheds some light on creating an environment that allows participants to express their views and desires,and listen to responses. Furthermore, as it turned out, it provided the organizers with a responsibility to select datasets thatprovide broad yet concise information to stakeholders in a very short period of time and devise technical methods that caninternalize and, in part, quantify the subjective discussions that takes place.

Our five-year effort in shaping this process allowed us to experiment with (and learn from) many facets of regionalvisioning. They include setting regional boundaries, projecting control totals and planning horizons, building leadershipgroups of representative organizations, selecting participants, building tools that facilitate planning discussions andconnecting processes to preliminary outcomes. The three main processes discussed in this paper (Table 1) are RealityCheck Washington (RC Washington), Reality Check Fredericksburg (RCF), and Reality Check Plus – Imagine Maryland(RC Maryland). These processes were organized in overlapping regions and were built on lessons of the preceding ones.Their outcomes provide ideas for future organization of such processes, and testing their effectiveness. Table 1summarizes the similarities and differences among them followed by a discussion on specific challenges and lessons inthe next sections.

3.2. Early attempts at engagement

Reality Check Washington was a one-day visioning exercise held on February 2nd 2005. It was organized to give theinvited audience ‘‘a sense of projected growth in the state’’. They were given tools to develop spatially explicit growthscenarios. Later on the same day, impacts of growth such as proximity of new development to transit, net futuredensities, etc., were computed and presented back to the group. The invited participants included, civic leaders,business leaders, environmentalists and elected officials, and their numbers and locations were balanced – weighted bypopulation of the sub-regions of their main activity. A group of organizers was responsible for getting a set of diverseparticipants.

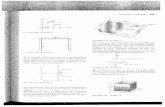

At the event (Fig. 2), 300 participants were divided into groups of ten that represented both the geographic and interestgroup diversity in the region. At each table, participants gathered around a large tabletop map of the region, color-coded torepresent the existing population and employment density, major highways, subway and commuter rail lines and stations,parklands and other protected conservation areas. The maps also had airports, military bases, and other governmentinstallations, rivers, floodplains, and other bodies of water. The participants were presented with a brief overview of theplanning issues of the region and the structure of the exercise.

To encourage participants to think regionally, rather than locally, all jurisdictional boundaries were intentionallyomitted from the base map, although place names of cities and towns were included for orientation and a sense of scale. Atrained scribe/computer operator and a trained facilitator staffed each table. Before considering where to accommodategrowth, participants were asked to reach consensus on a set of principles to guide their decisions. Principles, which variedfrom table-to-table, included protecting open space, making use of existing infrastructure, maintaining jobs-housingbalance and building new highways. The participants’ task was to envision allocating 2 million new residents and 1.6million new jobs in the Metropolitan Washington region (forecasts for 2030 by the Metropolitan Planning Organization) inthree hours.

During the pre-event months, we experimented with a commercial planning support system (Index1-Paint the Region).It was proposed that as participants around each table suggested a location to accommodate new growth, a computeroperator would zoom in on a projected map of the region to that locality and using Index1 software interface add newgrowth to the region. As each suggested location was discussed and eventually recorded by the operator, participants wouldbe able to see the computerized results, including remaining growth to be allocated and preliminary impacts of change,projected on a screen next to each table.

A series of mock games were held to ‘‘field-test’’ various maps and this two-step procedure. It soon became clear,however, that once the computer phase began, the active discussion among participants tended to tail off while they waitedfor the computer operator to record and display their decisions. Part of the difficulty was that the scale of Index1 seemedunsuitable for the macro nature of this multi-jurisdiction effort. It was recognized that use of the planning support systemwas having the unintended effect of slowing the momentum of the exercise.

2 For a detailed structure, see Fig. 1. Conceptual model of improved decision-making through scenario planning [39].

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399 391

Table 1

Summary table of Reality Check visioning exercises.

Event (Year) Led by Attendees Region # of Exs. Technical model Follow-up actions

RC Washington

(2004–05)

ULI. Washington, Council

of Governments, Board

of Trade

300 (1/3 civic and community

leaders, 1/3 business leaders,

1/3 elected officials)

Washington DC and

suburban Maryland

and Virginia Counties

1 Index, blocks/GIS None

RC Fredericksburg

(2005–06)

Fred. Chamber of

Commerce

100 (same distribution as above) Fredericksburg City

and surrounding VA

counties (w/in Rappahannock

Development Council)

1 Blocks/GIS None

RC Maryland

(2006–08)

NCSG/1000 Friends/ULI,

Baltimore

1000 (same distribution as above) State of Maryland 4 Blocks/GIS, followed

by focus groups

Scenario Analysis

Group (SAG),

Partnership for Land

Use Success (PLUS)

A.

Ch

ak

rab

orty

/Futu

res4

3(2

01

1)

38

7–

39

93

92

As a result, a few weeks before the event a new, more ‘‘hands-on’’ model was suggested, and after a few trials, adopted.This model used colored Lego1 blocks to represent the growth projections for each region: blue blocks represented 6000jobs; yellow blocks represented 3000 housing units. Each table was given a box with a number of colored blocks thatrepresented the total growth projected to come to the region. The task on each table was to allocate all the blocks to the mapwhile trying to build consensus with the rest of the group.

Maps of baseline conditions were overlaid with a grid scaled to a size where a single block fills a single square of thegrid. Participants who wanted to add more housing or jobs to a single square than what was represented by a singleblock simply needed to stack the blocks (possible due to modular structure of Lego1). Those who wished to proposemixed-use development could represent that by stacking housing and job blocks together. Once complete, the locationand height of the blocks represented a three-dimensional vision of the participants’ desires for growth throughout theregion.

Each square grid on the base map had a unique ID, which corresponded to a cell on a spreadsheet model and a polygon in aGIS database. At the conclusion of the exercise, the scribes and facilitators entered the number of blocks into the spreadsheetmodel, which then automatically updated the GIS database. In the end, 30 unique scenarios, one from each table, were fedinto the GIS database for overall analysis. Since the outputs varied by tables and region, the results were aggregated inmultiple ways. This included taking an average of all the tables by adding the final population and employment numbers ineach grid cell and dividing the sum by the total number of tables and taking a standard deviation of each grid across thetables. The presentation to participants included a comparison of their stated principles with quantitative assessments of theimpacts of their development visions.

The mock game attendees, who were chosen to mimic the diverse background of the event participants, also brought outthe challenges to communicating several aspects of the planned exercise. Scale of the map around a table that fits an areagreater than 5000 square miles, number of colored blocks that could be practically placed in less than three hours and a rangeof related questions raised by the attendees, helped us adjust many parameters of the process. As another example, manystakeholders questioned the validity of projected growth numbers (developed by the regional planning organization) thatthey were asked to use. This is a valid question given the projected growth was based on an extension of past trends, andassumptions on future policies. The organizers of the Washington exercise, however, made the growth projections ‘‘non-negotiable.’’ This was an error in our opinion that was corrected in subsequent Maryland exercise, not because theprojections are always wrong (though they are), but because, (1) the value of the exercise is not in its technical accuracy, and(2) the flexibility of changing projections made the participants feel more empowered.

During the event, discussion among participants reflected multiple aspects of the sustainability debate ranging fromequity in investment of public funds to negative impacts of land use controls on economic development, particularly in ruralcounties. Still there was a broad appreciation of the value of the process as evident in the following quotes from participantsrepresenting a range of backgrounds and interests.

[()TD$FIG]

Fig. 2. Scene at a Reality Check visioning event (Washington).

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399 393

‘‘We are going to concentrate on issues such as using our current infrastructure, specifically our transportation modesto really foster affordable hosing, workforce housing as well as jobs in the region on a very broad basis.’’ Retta Gilliam,President and CEO, East of the River CDC

‘‘As a professional of business, I knew it [projected growth] was big but until I saw it physically, on a map, I did not realize

how big it really is!’’ Jim Todd, President, The Peterson Companies

‘‘It’s going to have an impact as it is a really ingenious way of using maps and physical demonstration that exemplify these

issues of land use and density. . .’’ Anthony Williams, Mayor, Washington D.C.

3.3. Lessons from Reality Check Washington

In the days following the event, it received a wide coverage in the regional media. The Washington Post [40] reported:‘‘Despite the diverse interests at the 30 map tables, the solutions reached by afternoon shared a remarkable number ofthemes. . . If nothing else, yesterday’s exercise represented a rare attempt at regional land planning in Washington, an areariven by rivalries among more than 20 local governments, each with its own views of how the area should grow.’’ A report inthe Baltimore Sun [41] noted the agreements on principles but disagreements on location and density of new developments,while acknowledging the ‘‘lively debate, with some members pushing for more open space and others saying property rightsmust not be forgotten.’’ The comments and other observations made by participants, organizers and observers underscorethe inherent value of public participation in a future-oriented exercise.

However, the tangible post-event outcomes of the exercise are not clear. The visions generated during the exercise werenot intended for a finer-level analysis. There was no clear plan of further engaging the participants of the exercise and fewplanning agencies involved in the process showed any interest in connecting the momentary success of the exercise to anypolicy related initiative. This could be blamed, in part, to the lack of effective policy focus in visioning exercises, somethingintrinsic to the scale of such processes. In other words, deriving specific policy outcomes was not an explicit objective of theexercise.

Other criticisms of the effort were contradictory. On one hand, the lack of policy focus was attributed to lack of an existingregulatory framework within which to effort was organized. Maryland counties, Virginia counties and the District ofColumbia, all have different land use policy regimes, which were, in part, blamed for a lack of unified policy prescriptions. Forexample, zoning at the county level is paramount in Maryland, whereas city level zoning and county level comprehensiveplans are the main guiding documents in Virginia. On the other hand, issues of scale (too big for some, too small for others),non-inclusion of major areas (most importantly, Baltimore), and an urban area driven focus were blamed for a disconnectwith the reality.

One region that attempted to ride the interest generated by RC Washington was Rappahannock region in Virginia. It iswithin the boundaries of RC Washington region with Fredericksburg as the main urban center. Rappahannock RegionalCouncil organized a follow-up exercise titled, Reality Check Fredericksburg. It was an exercise that mimicked RC Washingtonat a smaller scale (5 counties, 30,000 projected population change) and it was not successful in generating even on-the-dayexcitement seen at the RC Washington event. Interestingly, due to the presence of large military training facilities (QuanticoMarine Corps Base and Fort A.P. Hill), much of the discussion revolved around uncertainties regarding federal governmentsupported jobs in the region.

In any case, these efforts provided several lessons (some mentioned above, others incorporated in the next section) thatinformed Reality Check Plus – Imagine Maryland (RC Maryland).

3.4. Reality Check Maryland in the context of previous efforts and policy

RC Maryland was an effort that grew out of the opportunity to impact regional action in land use in Maryland andfrustrations over lack of tangible impacts of the RC Washington exercise. The organizing team involved many leadingmembers of the RC Washington effort, including this author. However, first it is important to place this effort in the historicalcontext of regional thinking in Maryland.

Maryland has a long history of innovative planning action at both local and regional levels. Since the 1937 RegionalPlanning Report produced by the Maryland State Planning Commission [42], regional agencies have continued to workforward. Most notable of these plans are the 1960s ‘‘On Wedges and Corridors – a general plan for the Maryland–Washingtonregional district’’ [43] and the Critical Areas Act of 1984. More recently, the 1997 legislature passed the five initiatives thathave led to Maryland’s recognition as a leader in the promotion of smart growth; They are: (1) The Priority Funding Areas(PFAs) Act that limited state subsidies for infrastructure only to projects that are either within municipalities, inside thebeltways, or in other areas that meet certain criteria; (2) The Rural Legacy Act under which the state provides funds topurchase development rights on properties in rural areas in order to preserve agriculture, forest, and natural resource landsin contiguous blocks; (3) Brownfield Voluntary Cleanup and Redevelopment Act that provides incentives and assistance to

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399394

eligible participants in the cleanup and redevelopment of underutilized industrial properties that are, or are perceived to be,contaminated; (4) Live Near Your Work program that promoted linkages between employers and nearby communities byoffering incentives to employees to buy homes in proximity to their workplace; and (5) Job Creation Tax Credit Act designedto boost employment within the newly established PFAs by providing state income tax credits to employers who created 25or more new, full-time jobs in those areas.

These programs, collectively called Maryland’s Smart Growth Program, positioned Maryland as a national leader inproactive development policies; especially its reliance away from regulations and towards spatially specific incentives [44].However, the efficacy of Maryland’s program has been in many recent studies have been questioned. For example, Shen andZhang [45] found that though higher share of urban development after 1997 happened inside PFAs, but only in thosecounties that had strict local development regulation prior to 1997. A separate study by Howland and Sohn [46] found thatmany wastewater treatment investments, including some funded by the state were happening outside the PFAs. Suchstudies suggest that despite implementing innovative policies, it is difficult to make significant changes to continuing trends,especially when supportive local policies are lacking.

3.5. Structure of Reality Check Maryland

The above discussion is pertinent to the background of Reality Check Maryland for multiple reasons. Those organizersfrom Maryland who had participated in the Washington effort understood the benefits of working within an existing, unifiedinstitutional framework. However, structurally that meant adjusting the exercise to consider many ex-urban and rural areasnot part of a metropolitan area, and generating interest among the residents of these areas and their leaders. The first set ofevents was in 2006, the year of gubernatorial election and many legislative elections in Maryland. It provided a goodopportunity to enhance the visibility of the effort by inviting prominent candidates. Several of them accepted the invitation,including then Mayor of Baltimore (and present Governor of Maryland) and another leading candidate for the same post. Thisprovided added visibility to the events that helped attract other invited participants. Other external events that helped shapethe exercise, audience and outcomes included, general concern about Maryland’s infrastructure, environmental health of theChesapeake Bay, Baltimore’s economy, projected growth in suburban counties, and then increasing housing prices andrelated affordable housing ‘‘crisis’’ [40].

It is within this context that RC Maryland – a platform to discuss alternative policies that may lead to a desirable future fordiverse interest groups – was organized. In the new format, the state was divided into four regions (Fig. 3) in each of which aseparate event was held. Projection for the year 2030 developed by the Maryland Department of Planning was used ascontrol totals and it was divided up into four parts that were the sum of projections in all the counties within these regions.This was important for many reasons. The events could be held closer to the participants and assured higher participation. Itdevoted more time to the exurban and rural areas of the state and their issues. And it allowed larger maps of each region onwhich existing conditions and plans could be scrutinized in greater detail. Splitting the state also led to several newquestions, such as where to draw regional boundaries, how the control totals should be allocated, and how the participantswill treat the given control totals. Other issues included differences in mean densities and development types between urbanand rural regions and that affected the assumptions we could make for each region and the state.

[()TD$FIG]

Fig. 3. Combined map of four Reality Check regions.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399 395

This exercise used blocks of four different colors to represent the growth projections for each region: blue blocksrepresented jobs; white blocks represented the top 80 percent of new housing units in the region based on price; yellowblocks represented the bottom 20 percent of new housing based on price, essentially a stand-in for non-subsidized affordablehousing; and, black blocks represented lower density housing development that could be exchanged for higher densitywhite blocks at a ratio of 4:1. Again, each table was given a box with exactly enough colored blocks to represent the totalgrowth projected to come to the region. Since the outputs varied by tables and regions, after all the exercises were completeda method was devised to aggregate everything into a single, statewide scenario. For each region, all the tables were averagedto create a final, aggregate regional scenario. All the regional scenarios were finally joined and the resulting statewide gridwas named the Reality Check scenario.

As in other exercises, the participants were presented with the outcomes of each table, an aggregate vision for theregion and a compilation of guiding principles. However, this time two additional scenarios were developed,exogenously, for the participants to consider and compare to their own version – (1) a spatially disaggregated Council ofGovernments (COG) scenario, based on COGs projection of spatial distribution of growth in jobs and households, and (2)a buildout scenario, based on an assessment of buildout under existing zoning (Fig. 4). These provided two alternativeversions of the future – one a ‘‘business as usual’’ scenario (COG) for 2030 and the other, where development occurred tofill up the entire existing capacity without regard to a specific time horizon – a proxy for completely successful localgovernment planning.

Together they presented three hypothetical yet plausible alternative futures that were then compared on a set of quality-of-life indicators. These included, percentage of development in each scenario that were inside PFAs and Beltways,development close to transit and major roads, and new development that went into currently undeveloped andenvironmentally sensitive areas. Development patterns were also compared by projected impacts on vehicle miles travelledunder each scenario, new lane miles needed to maintain existing level of services and new impervious surfaces created. The

[()TD$FIG]

Fig. 4. From top to bottom-Household distribution in Maryland in year 2000, household distribution under buildout of zoning and household distribution in

the aggregate Reality Check Maryland scenario for year 2030. Darker and taller blocks represent higher densities.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399396

participants were then asked to reflect upon the results of their own and other scenarios with respect to their stateddevelopment principles. Finally, they broke-out into groups to reflect upon the lessons learned from the exerciseand how they may apply it in their field of interest and influence as well as in other public forums where theyparticipate.

3.6. Lessons from Reality Check Maryland

RC Maryland addressed many of the shortcomings identified in RC Washington. They include subdividing the region intosub-regions with comparable geography, culture and challenges, and devising a more nuanced exercise with physical blockswithout taking away the ease of a hands-on game type format. In addition, it provided benchmarks for participants tocompare their scenarios with other futures based on wide set of easily understandable indicators. In general, it presented anew model for large group interaction efforts subsequently adopted in several regional exercises including, RC-Tampa,Vision North Texas, RC Charleston, SPAN Europe.

The event engaged more than 100 organizations in a leadership role and close to a 1000 invited participants during thefour exercises. The participants represented diverse sections of the society including ethnic and geographic groups. Whileassigning participants by individual tables careful attention was paid to mix interests and backgrounds. This somewhat tookaway the possibility of generating radically different scenarios but kept focus on regional issues and helped establish acommon ground across the table. Thus, when the principles that emerged from different tables were analyzed, there was ahigh-degree of agreement.

Policy related layers displayed on the map, such as PFA boundaries, channeled discussion on policy ideas in similar arena,in particular, state level land use and infrastructure policy. These were then complemented by encouragement fromfacilitators to think about other agencies and ideas, including private actions and government agencies working at a differentscale. Many participants, especially representatives of rural communities, developers and minority leaders, admittedattending such an event for the first time and getting a better sense of regional issues.

In the months following the exercise, the success of the event acted as a foundation to develop multiple initiatives rangingfrom analysis to advocacy. These involved old and new collaborators including, universities (University of Maryland atCollege Park; University of Maryland, Baltimore), environmental organizations (1000 Friends of Maryland, Chesapeake BayFoundation), real estate organizations (Urban Land Institute, Baltimore, National Association of Home Builders) andgovernmental agencies (Maryland Department of Planning and Maryland Department of Transportation). The two mostvisible follow-up efforts have been – Partnership for Land Use Success (PLUS), an advocacy organization devoted togenerating more awareness of land use issues and Scenario Analysis Group (SAG), a focus group to review and support finer-level scenario analysis.

4. Conclusion

For the organizers, the exercises provided an opportunity to build a coalition of divergent regional groups, experimentwith models to engage representative stakeholders, and devise tools for effective scenario planning. For the participants, theexercise presented an opportunity for discourse. The base map and blocks provoked discussion not only on ‘‘where we grow,’’but also on ‘‘how we grow’’ as a region. The information on regional trends and their local implications, negotiations withopposing interests across the table, and the exercise on generating common principles of growth informed and enhanced thisdiscussion. For both the organizers and the participants, the process was also an opportunity for unlearning and finding acommon ground with representatives of groups with opposing viewpoints. For example, redevelopment and infill strategiesare often promoted in growing ‘‘smart’’ literature. However, an assessment of redevelopment-oriented scenariosdemonstrated that given the projected growth, potential impacts of redevelopment are low and the challenges are high.Other impact measures such as loss of open space and vehicle miles travelled showed developers and business leadersregional impacts of land use preservation policies.

From a policy standpoint, the value of scenario evaluation and computed measures of impact are less clear. The degree ofanalysis got more sophisticated over time, and preliminary results presented to the participants, howsoever crude, wereinformative. The analytical process had numerous oversimplifying assumptions. For example, there were limitations indefining variables, in using a limited number of indicators to judge a scenario and in selecting the best unit of analysis and inproper interpretations of results. The connection to top-down processes, in particular large-scale regional models thatevaluate policy decision and ultimately its integration into the policy-making framework remains the focus on ongoingwork.

Still the outcomes were successful in demonstrating measurable differences among scenarios created by differentgroups and, scenarios developed external to the participatory process. In the author’s opinion, the evolution of RealityCheck tells the story of a developing participatory framework that gradually elevates its intrinsic value in combiningtechnical analysis with participant generated ideas and conflicts that lead to a self-realization of challenges,opportunities and their own role in the process to shape the future. In addition, as the sequence of exercises and theirpreliminary outcomes demonstrate, the timeliness of the effort, external conditions including institutionalframework, market forces, and structural components of the process itself, all play a role in its tangible externaloutcome.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399 397

5. Discussion

Planning by definition is an exercise in imagining and shaping the future. Literature has demonstrated that planner’s rolein shaping the future should not be limited to outcomes but extend to process. Such a process should be inclusive of theunderrepresented, engaging to the community from its earliest stages, and use technical and other tools to communicatetrade-offs. In case of Reality Check, the analytical and participatory facets of the planning process were acknowledged and anattempt was made to integrate the two in a simultaneous exercise. This was done in different degrees in different exercisesand a comparison of outcomes illustrates the significance of a more thoughtfully designed process.

Still, barriers to participants’ understanding of planning issues could be resolved only through constant involvement. Anobservation made by some participants that is worth noting here is the lack of visible differences among most scenarios. Thiswas sometimes due to crude aggregation of indicators, or underestimation of the differences as perceived by the participants.This is an example where planners understanding of local issues and ability to communicate complex ideas plays a crucialrole in the success of the process. Another example is the relentlessness with which participants challenged the assumptionsand definitions used in the exercise. Most commonly challenged ones were the regional forecasts and the organizers choiceof regional boundaries. This underscored the biases that planners bring when defining boundaries by existing institutionalstructures, whereas others may have their own definitions of a region based on culture, commute-shed, etc. Theseconversations led to others that ultimately helped many participants think more regionally or from a statewide perspective.Specifically, it provided policymakers and stakeholders a way to look beyond short-range, budget-cycle-based programs.

In summary, the growing literature on efficacy of regional planning processes needs more examples of innovativeparticipatory methods and quantitative modeling techniques. Examples that connect the two are limited and recent. But theresults are encouraging. In the case of post-Reality Check effects, the SAG workshops led to evaluation of many policy-basedscenarios including a high-speed rail scenario and a Baltimore dominated growth scenario, based on ideas that wereoriginally floated during the RC Maryland Exercise. Many concurrent processes have since emerged whose existence couldbe partly credited to Reality Check Maryland. This includes an ongoing effort to build a statewide transportation model and astatewide land use model, which will together provide the capability to assess impacts of land use and transportationinvestment policy. Other models that assess impacts of development on the Chesapeake Bay’s water quality, regional airquality, fiscal impacts of growth under different scenarios are also under development. The process continues engage manyof the earliest participants through regular public forums3 and an open source information exchange portal.4

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education at the University of Maryland,College Park. The research and action teams included more than 100 collaborators and volunteers representing variousorganizations within Metropolitan Washington region and the State of Maryland. Opinions expressed in this paper are solelythose of the author.

References

[1] R.E. Klosterman, Arguments For and Against Planning, in: S. Fainstein, S. Campbell (Eds.), Readings in Planning Theory, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 1996,pp. 86–100.

[2] C.E. Lindblom, The Science of ‘‘Muddling Through’’, Public Administration Review 19 (2) (1959) 79–88.[3] J. Jacobs, The Death and Life of the Great American Cities, Random House, New York, 1961.[4] J. Friedmann, Planning in the Public Domain, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1987.[5] P. Davidoff, Advocacy and pluralism in planning, in: S. Fainstein, S. Campbell (Eds.), Readings in Planning Theory, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2003, pp.

210–223.[6] N. Krumholz, A retrospective view of equity planning, Journal of the American Planning Association 41 (3) (1982) 298–304.[7] L. Sandercock, Toward Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1998.[8] J. Forester, What Do Planning Analysts Do? Planning and Policy Analysis as Organizing, Planning in the Face of Power, University of California Press, Berkeley,

1989.[9] J.M. Thomas, Planning History and the Black Urban Experience: Linkages and Contemporary Implications, Journal of Planning Education and Research 14 (1)

(1994) 1–11.[10] S.A. Harwood, Environmental Justice on the Streets: Advocacy Planning as a Tool to Contest Environmental Racism, Journal of Planning Education and

Research 23 (1) (2003) 24–38.[11] M. Brooks, Planning Theory for Practitioners, APA Planners Press, Chicago, 2002.[12] H. Baum, Culture matters – but it shouldn’t matter too much, in: M. Burayidi (Ed.), Urban Planning in a Multicultural Society, Praeger, Westport, CT, 2000.[13] P. Hall, Scenarios for Europe’s cities, Futures 18 (1986) 2–8.[14] P.W.F. Van Notten, J. Rotmans, M.B.A. Van Asselt, D.S. Rothman, An updated scenario typology, Futures 35 (5) (2003) 423–443.[15] A. Carlsson-Kanyama, K.H. Dreborg, H.C. Moll, D. Padovan, Participative backcasting: a tool for involving stakeholders in local sustainability planning,

Futures 40 (2008) 34–46.[16] L. Borjeson, M. Hojer, K.H. Dreborg, T. Ekvall, G. Finnveden, Scenario types and techniques: towards a user’s guide, Futures 38 (7) (2006) 723–739.[17] D. Myers, A. Kitsuse, Constructing the future in planning: a survey of theories and tools, Journal of Planning Education and Research 19 (2000) 221–231.[18] D.R. Porter, Downtown linkages, Urban Land Inst, 1985.[19] J.D. Hunt, D.S. Kriger, E.J. Miller, Current operational urban land-use – transport modeling frameworks: a review, Transport Reviews 25 (3) (2005).

3 For more details on the ongoing efforts, please visit http://www.smartgrowth.umd.edu/marylandscenarioproject/index.htm.4 For more details on the Geoportal, please visit http://www.leam.uiuc.edu/maryland/.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399398

[20] J. Landis, The California urban futures model: a new generation of metropolitan simulation models, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 21 (4)(1994) 399–420.

[21] R.E. Klosterman, Guest editorial – an update on planning support systems, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 32 (4) (2005) 477–484.[22] H.W.J. Rittel, M.M. Webber, Dilemmas in a general theory of planning, Policy Sciences 4 (1973) 155–169.[23] A. AtKisson, Developing indicators of sustainable community: lessons from sustainable Seattle, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 16 (1996) 337–350.[24] G.R. Kissler, K.N. Fore, W.S. Jacobson, W.P. Kittredge, S.L. Stewart, State strategic planning: suggestions from the oregon experience, Public Administration

Review 58 (1998).[25] R.J. Grow, A. Matheson, Envision Utah: laying the foundation for quality development, Urban Land 65 (2006) 63.[26] A. Barbanente, A. Khakee, M. Puglisi, Scenario building for metropolitan Tunis, Futures 34 (2002) 583–596.[27] B. Deal, A. Chakraborty, Cyber-physical planning support systems: advancing participatory decision-making in complex urban environments, International

Journal of Operations and Quantitative Management: Special Issue on Complex Systems vol. 16 (2010) 1–15.[28] CMAP’ s GO TO 2040 comprehensive planning campaign, 2009-11-05 23:57:58. http://www.goto2040.org/about.aspx.[29] M. Emery, The power of community search conferences, After Atlantis: working, managing, and leading in turbulent times (1997) 149.[30] B.B. Bunker, B.T. Alban, Introduction to the special issue on large group interventions, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science vol. 41 (2005) 9–14.[31] L.D. Hopkins, M. Zapata, Engaging the Future: Forecasts, Scenarios, Plans, and Projects, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Mass, Cambridge, 2007.[32] P. Hall, Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century, third ed., Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2002.[33] N. Krumholz, Equitable approaches to local economic development, readings in planning theory, in: S. Fainstein, S. Campbell (Eds.), Readings in Planning

Theory, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 1996.[34] S.D. Brody, D.R. Godschalk, R.J. Burby, Mandating citizen participation in plan making: six strategic planning choices, Journal of the American Planning

Association 69 (3) (2003) 245–264.[35] U.P. Avin, J.L. Dembner, Getting scenario-building right, Planning 67 (11) (2001) 22–27.[36] H. Morgan, L. Deuben, Planning at the speed of change, in: URISA Annual Conference/GIS In Addressing Conference Proceedings, 2005.[37] B. de Sousa Santos, Participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre: toward a redistributive democracy, Politics and Society 26 (1998) 461–510.[38] L.D. Hopkins, Integrating knowledge about land use and the environment through use of multiple models, in: Paper Delivered at Arizona State University

Conference, 2000.[39] T.J. Chermack, Improving decision-making with scenario planning, Futures 36 (3) (2004) 295–309.[40] P. Whorisky, Building Strategies To Map Out Growth, Washington Post, February 3 (2005) B01.[41] C. Walker, How D.C.’s Future Stacks Up, Baltimore (MD) Sun, February 3, 2005.[42] Regional Planning Part IV Baltimore–Washington–Annapolis Area, Maryland State Planning Commission, 1937.[43] On Wedges and Corridors, A General Plan for the Maryland–Washington Regional District, Montgomery County Planning Department, 1963.[44] J.R. Cohen, Maryland’s ‘‘Smart Growth’’: using incentives to combat sprawl, in: G. Squires (Ed.), Urban Sprawl: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses,

Urban Institute Press, Washington, DC, 2002, pp. 293–324.[45] Q. Shen, F. Zhang, Land-use changes in a pro-smart-growth state: Maryland, USA, Environment and Planning A 39 (2007) 1457–1477.[46] M. Howland, J.Y. Sohn, Has Maryland’s priority funding areas initiative constrained the expansion of water and sewer investments? Land Use Policy 24 (1)

(2007) 175–186.

A. Chakraborty / Futures 43 (2011) 387–399 399