report of investigation - into allegations of sexual harassment ...

Effects of rain and fly harassment on the feeding behaviour of free-ranging feral goats

Transcript of Effects of rain and fly harassment on the feeding behaviour of free-ranging feral goats

Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 24 (1989) 31-41 31 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam - - Printed in The Netherlands

Effects of Rain and Fly Harassment on the Feeding Behaviour of Free -Ranging Feral Goats

EMMA L. BRINDLEY 1'*, DAVID J. BULLOCK 1 and FIONA MAISELS ~

I Department of Biology and Pre-clinical Medicine, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, Fife KY16 9TS (Gt. Britain) ~Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Edinburgh, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JU (Gt. Britain)

(Accepted for publication 30 March 1989)

ABSTRACT

Brindley, E.L., Bullock, D.J. and Maisels, F., 1989. Effects of rain and fly harassment on the feeding behaviour of free-ranging feral goats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 24: 31-41.

This paper describes the effects of rain and the headily (Hydrotaea irritans) on the feeding behaviour of feral goats. Rain reduced feeding bout lengths and caused an increase in the use of both man-made and natural shelter (vegetation), resulting in reductions in daily feeding time. Feeding time was particularly reduced for those goats which had been shorn. Goats responded to increasing fly abundance by increasing their rates of head shaking, ear flicking and movement. Feeding bout lengths and the number of feeding stations used decreased in response to increasing fly abundance. In general, increasing fly abundance was associated with decreased feeding time. Shorn goats were particularly susceptible to fly harassment and showed a correspondingly greater loss in feeding time than unshorn goats. The study demonstrated the importance of shelter to goats, especially those that have been shorn.

INTRODUCTION

The ways in which r u m i n a n t s feed is repor ted to be de te rmined largely by body size and the qual i ty and quan t i t y of available forage ( H o f f m a n n , 1968; J a r m a n , 1974). E n v i r o n m e n t a l variables such as wea ther and insect harass- m e n t also inf luence feeding behaviour . Arno ld and Dudzinsk i (1978) no ted tha t in sheep, cat t le and horses, rain appeared to have little effect on general behav iour unless it was heavy. A m o n g s t domest ic l ivestock, the goat appears to be par t icu lar ly sensit ive to wet weather , f requent ly seeking shel ter in per- s is tent rain. For feral goats on the Isle of R h u m , the a m o u n t of the day spent

*Author to whom correspondence should be addressed at: Animal Behaviour Research Group, Department of Zoology, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2DE, Gt. Britain.

0168-1591/89/$03.50 © 1989 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

32

sheltering in caves was positively associated with the level of rainfall on that day (Boyd, 1981 ). Thus, rain may depress total daily feeding time and, assum- ing no changes in either bite rate or bite size, total daily intake. However, the effects of rain on the feeding behaviour and feeding time of ruminants have rarely been quantified.

Harassment by biting or sucking Dipterans has been reported to have a con- siderable effect on the ecology and behaviour of caribou and reindeer (Rangi- fer) during summer. For instance, fly harassment causes increased movement and aggregation in this species, and the resultant high level of interaction pre- vents individuals from nursing calves (White et al., 1981). In horses, attacks by tabanid flies similarly reduce total daily feeding time (Duncan and Vigne, 1979). In domestic sheep, harassment by the sucking headily (Hydrotaea ir- ritans: Muscidae) may result in weight losses of up to 9 kg (Hunter, 1975), presumably through a reduction in feeding time. Casual observations by one of us ( D.J.B. ) suggested that domestic goats show similar losses of feeding time when subject to severe fly harassment.

Factors affecting the feeding behaviour of free-ranging feral goats have been little studied. Such data are of enormous potential importance to the goat farmer, in particular those involved with the increasingly popular production of cashmere wool from feral goats. In this industry, cashmere must be har- vested by combing or shearing in late winter/spring, with the result that combed/shorn goats lose the insulating value of their coats during the season of poorest weather, when they are likely to be in poorest body condition. In this paper, we describe the effects of both wet weather and fly harassment on the feeding behaviour of feral goats.

STUDY AREA AND METHODS

The study was conducted between 3 June 1987 and 8 July 1987 at Tentsmuir Point National Nature Reserve, Fife (56o26 'N, 2o49 ' w ) , where feral goats are being used in experimental scrub control trials. Male goats in three groups (see Table 1) were available and were contained within 50X 50-m paddocks provided with wooden, waterproof shelters and water. Two groups within Pad- docks H1 and H2 each comprised 3 unshorn and 1 shorn goat. A third group within Paddock L1 comprised 2 shorn goats. Shorn goats were machine shorn in March and by June the fleece depth was approximately half that of an un- shorn goat (Table 1).

Vegetation cover consisted of a ground layer of herbs, graminoids and creep- ing willow (Salix repens), and a scrub layer of birch (Betula pendula) ~ 1 m tall. In 1986, the percentage cover of birch in H1, H2 and L1 was 18.2, 8.7 and 23.8, respectively (Bullock and Kinnear, 1988) so that H2 provided consider- ably less natural shelter than H1 or L1. To reduce the possible effects of dif- ferences in the amounts of natural shelter between paddocks, goats in H1 and

TABLE 1

The composition of goat groups in each of three paddocks in June

Paddock Goat Weight (kg) Fleece depth (mm)

HI US1 45.5 16.0 US2 39.5 14.5 US3 40.5 15.5

S1 24.5 7.5

33

H2 US4 41.5 15.5 US5 42.5 14.0 US6 37.0 15.0

$2 34.0 7.5

L1 $3 53.3 7.0 $4 35.5 7.0

US, unshorn; S, shorn. Fleece depth was measured as the vertical projection of a ruler from the skin surface to the outermost hairs.

H2 were exchanged after 18 days. Sample wind speed recordings made at both feeding and sheltering sites (after Staines, 1976) provided an estimate of shel- ter available.

Unseasonably cold and wet weather during the first half of June allowed observations on the effects of weather to be made in the absence of headflies. Headily abundance increased dramatically after mid-June in response to the warmer and drier weather. Headily was by far the most abundant harassing fly and virtually all irritable behaviour could be ascribed to the effects of this species.

Behavioural observations

Data were collected on the following. Feeding bout length: estimated using the log survivor function (Slater, 1974)

of gaps in feeding from instantaneous scan samples (Altmann, 1974 ) taken at 60-s intervals throughout a 24-h period between 3 and 4 June. Examination of' the curve showed that a gap of 10 min in feeding indicated termination of a feeding bout, so this criterion was employed in measuring bout lengths.

Ear flicking rate: no. of flicks of either ear per 60 s. Head shaking rate: no. of head shakes per 60 s. Pace rate: no. of movements of left foreleg per 60 s. Feeding station: defined as a location of feeding separated by at least two

paces from the last one. Interruption to lying: (in response to fly harassment), standing up from

lying, followed within 60 s by lying down again.

34

Latency to seek shelter: time taken to move to shelter (whether man made or increased density of vegetation) after the onset of rain.

Wet hour: one in which rain fell for > 30 min. Dry hour: one in which rain fell for ~< 30 min. Behaviour and time budgets were recorded using instantaneous scan sam-

pling, focal animal sampling (Altmann, 1974) and field notes written onto a checksheet. Scan sample intervals were usually 5 min, in the first, second, third and fourth of which the number of ear flicks, number of head shakes, number of paces and number of feeding stations, respectively, were recorded.

Observations on the effects of fly harassment took place between 09.00 and 17.00 h, the period of maximum headily activity (Titchener et al., 1974). Fly abundance was estimated every 30 min by counting the number of flies around the stationary observer's head after a period of 2 min at goat head height. Abundance classes were 0, I, II, III and IV, corresponding to 0, 1-5, 6-10, 11- 15 and > 15 flies, respectively.

Data analysis

Feeding bout lengths (as determined using the log survivor function ) of shorn and unshorn goats were compared for various environmental conditions using "t" tests. Differences in the mean time that individuals spent in shelter and the mean latency to seek shelter were compared using Kruskal-Wallis one- way analysis of variance (Siegel, 1956). In order to avoid the pooling fallacy (Machlis et al., 1985 ), i.e. the use of repeated measures of the same individual as independent values, mean values for each individual have been used.

RESULTS

Effects of weather

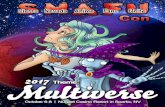

Feeding time: dry conditions Total observation time under dry conditions amounted to 131 h. All goats

showed a daily activity pattern that included two main feeding periods, early morning and late evening. Typically, shorn goats tended to have longer total daily feeding times than unshorn goats (Fig. 1). For example, US1 and US4 fed for an average of 10.3 and 8.4 h, respectively, over three recorded dry days, whereas $3 and $4 fed, on average, for 14.0 and 13.9 h, respectively. The dif- ference was particularly marked for Goats Sl and $2 (which were also smaller and lighter than the other goats; Table 1 ), which fed for an average of 15.8 and 15.7 h, respectively over the same sample period. The 2 shorn goats running together in L1 fed for longer periods than those running with unshorn goats.

35

I00

C

~5 ¢ 5 0

03

. . . . . . , ,

O0 0600 0900 1200 1500 1800 2100 2400

T ime of day ( h ) ( B S T )

Fig. 1. Feeding activity {percentage feeding in 30-min intervals from scan samples taken at 1- or 5-min intervals) of one goat selected at random from each paddock over 1 day (11 June 1987). Paddock H1, 0 ; H2, O; L1, A.

Feeding time: wet conditions Total observation time in wet conditions amounted to 68 h. All goats showed

a reduction in total daily feeding time in wet weather compared with that in dry weather. Shorn goats were particularly reluctant to start feeding after the onset of rain. During rain, shorn animals showed a great reduction in both percentage (45%) and total amount of time spent feeding. Morning feeding time dropped from 69.1% of total observation time in dry weather to 44.3% in wet conditions, and from 74.3% of dry evening periods to 34.6% in rain. Un- shorn goats also reduced their feeding time during rain, but only in the after- noon/evening period, with a decrease from 64.0 to 35.5% of total observation time (15.00-23.00 h).

Effects of weather on feeding bout length

In dry weather, mean feeding bout lengths during morning and evening pe- riods were generally longer than those at other times of day. Feeding bout lengths for shorn goats were significantly longer than those of unshorn goats (Fig. 2).

In rain, shorn goats showed a significant reduction in feeding bout length in both the early morning and late evening periods (Fig. 2). In contrast, mean feeding bout length of unshorn goats remained similar to those in dry weather. The mean number of feeding bouts in each time period decreased significantly for shorn goats when exposed to rain. During the early morning period (before 09.00 h), the mean number of feeding bouts decreased from 9.8 (S.E.--0.3 ) to 0.5 (S.E.--0.2), (t=3.41, d f = l l , P<0.01) . In contrast, unshorn goats main- tained a similar number of feeding bouts, irrespective of weather. For the time

36

0oia 5

150 [b ]

: l o o , /

Q 0 9 09-12 14-17 17-20 >20

Time ol day (h } [BST)

Fig. 2. Diurnal variation in feeding bout length (x_+ 95% C.L. ). (a) Dry weather. (b) Wet weather. Shorn, ~ ; unshorn, m. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. "t" tests were used throughout.

period before 09.00 h, mean numbers of feeding bouts in dry and wet weather were 8.1 ( S.E. = 0.6 ) and 7.9 (S.E. = 0.5 ), (t = 1.85, d f = 17, P > 0.05 ).

Shelter-seeking behaviour

Sample free wind speed recordings est imated the shelter afforded by vege- tation to equal a 52, 63 and 54% reduction in Plots A, B and E, respectively. In all plots, man-made shelters afforded a 99% reduction in free wind speed.

All goats sought shelter in rain (Table 2). Shorn Goats S1 and $2, within groups dominated by unshorn goats, spent less time in shelter than shorn Goats $3 and $4 in Paddock L1, which contained no unshorn animals. Latency to seek shelter after the onset of rain was significantly shorter for shorn goats (irrespective of whether the group contained unshorn animals) than for un- shorn goats of equivalent body size (Table 2). Importantly, shorn goats lost a much greater proportion of total daily feeding time to sheltering behaviour than did unshorn goats.

Effects of headily

Total observation time in the presence of headfly amounted to 59 h. Irritable behaviour (ear flicking and head shaking) only occurred when headflies were

37

TABLE2

Median percentage of time spent sheltering and median latency to seek shelter after the onset of rain fbr unshorn goats in Paddock H1 (US1, US2, US3), Paddock H2 (US4, US5, US6) and shorn goats (S1, $2, $3, $4). For percentage time spent in shelter, the number of hours of observation time is given in parentheses. For latency to seek shelter, the total number of observations is given in parentheses

Goat Percentage of time spent in shelter Latency (min) to seek (median) shelter ( median )

Dry Wet

US1, US2, US3 0.30 (41) 38.91 (21) 18.00 (15) US4, US5, US6 0.90 (45) 39.00 (27) 13.86 (12) S1,$2, $3, $4, 3.65 (41-45) 61.80 (20-27) 1.99 (12 17) Kruskal Wallis H 6.956 6.564 7.086 P <0.01 <0.05 <0.01

f 75

¢ a~

m 5.0 m

o)

":z6 25 L ~ j _ ~

50

4o =_ E 30

20

z 10

o I IL III IV

Fly abundance

Fig. 3. Relationships between head shaking rate, ear flicking rate (2_+ 95% C.L.) and fly abun- dance. Figures show comparisons of one shorn ( C:] ) and one unshorn ( ill ) goat chosen at ran- dom. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. "t" tests were used throughout.

38

c

:'5 ..,a ~' 2 ~ - ,~ a, o ~ ~ 25" 50 7 5 - ~

u .

Z

50 o

2.5

._c

0 I II III IV S Z

Fly abundance

Fig. 4. Changes in feeding bout length, pace rate and number of feeding stations used for shorn ( [:Z ) and unshorn ( I ) goats in relation to fly abundance. All values are 2 + 95 % C.L. * P < 0.05; • * P < 0.01; *** P< 0.001. "t" tests were used throughout.

present and became more f requent with increasing fly abundance. At all t imes, headflies harassed shorn goats more t h a n unshorn goats (Fig. 3). Highest ear flicking rates occurred when feeding or lying in direct sunl ight as opposed to when in shade; ha ra s smen t was considerably reduced on movemen t to shade.

For all goats, increasing fly abundance was inversely related to mean feeding bout length (Fig. 4). Shorn goats effectively s topped feeding in response to intense harassment . Increas ing fly abundance also caused an increase in pace rate and a decrease in the number of feeding s ta t ions used, par t icular ly when fly abundance exceeded Class III (Fig. 4). Shorn goats were again more liable to ha ra s smen t t h a n unshorn goats. Thus , fly ha ra s smen t resulted in increased walking with a consequent reduct ion in t ime available for feeding.

DISCUSSION

Effects of weather and shearing

The feeding behaviour of shorn and unsho r n goats was clearly al tered by bo th rain and fly harassment . In dry weather , the tota l daily feeding t ime of

39

shorn goats was often longer than that of unshorn goats. We had no reason to suspect that there were differences in bite size between individual goats within the same group on the same day, and bite rates varied little throughout the study (D.J. Bullock and F. Maisels, in preparation). Thus, we believe that the longer total daily feeding time of shorn goats in dry weather reflected higher total daily intakes. This is in contrast to shorn sheep for which grazing time increases only slightly, but bite size increases by up to 43% (Arnold and Birrell, 1977).

During rain, unshorn goats began fewer feeding bouts, but bout length changed very little; shorn goats similarly began fewer feeding bouts in rain, but these were invariably short. This suggests that shorn goats would show reduced intake and a consequent loss of condition in periods of persistent rain and in the absence of adequate shelter. Similar observations have been re- ported for shorn sheep; on cold days those in poor condition ceased to feed almost totally (Arnold and Birrell, 1977).

The practice of shearing farmed feral goats for their cashmere underwool ill early spring will accelerate heat loss at the skin surface. Cold stress in the clipped ungulate is considerably greater than for those with a natural coat length (Alexander, 1974 ). Heat loss is also dependent upon body size and basal metabolic rate; smaller goats with a higher surface :volume ratio are likely to be subject to cold stress under less extreme conditions. The chilling effects of' wind with rain can be particularly marked; wet (sheep) fleece provides only 52% of' the insulation of that of a dry fleece (Alexander, 1974). A general equa- tion describing the effects of wind on a wet fleece (Blaxter et al., 1963) when applied in the present circumstances, shows that for shorn goats with a fleece depth half that of unshorn goats, total fleece insulation is only ~ 50% of the value obtained for full coat depth. Also, calculated values considerably under- estimate the true extent of heat loss since the goat presents a higher sur- face :volume ratio than that assumed by a cylindrical model or even a sheep of the same mass. The 2-fold increase in heat loss in shorn goats is likely to be the cause of their longer total daily feeding times (and consequently higher intake than unshorn goats) in dry weather. The greater readiness of unshorn goats to shelter from rain was presumably an attempt to minimise heat loss.

Effects of headily

As fly abundance rose, the feeding behaviour of the goats was increasingly subject to interruptions during which ear flicking and head shaking were used to repel flies. Head shaking, interruptions to lying and ear flicking will not only reduce feeding time, but can also be expected to result in a cost in terms of energy expenditure. In combination with reduced feeding bout lengths, in- creased pace rate and a decrease in the number of feeding stations used per unit time, fly harassment may serve to reduce daily intake considerably.

40

Shorn goats were more susceptible to fly harassment than unshorn goats. This is likely to have been because of their greater sensitivity to settling flies, in combination with an increased a t t ract ion of flies to the head, neck, back and belly. Lying down as a response to harassment has been observed in some farmed red deer, Cervus elaphus L. (Espmark and Langvatn, 1979), but not others (Woollard and Bullock, 1987). In the present study, however, lying down in direct sunlight led to an increased attraction of flies to both the head and eyes. Subsequent responses included frequent interruptions to lying, increased walking and, in extreme cases, movement to shade.

Implications

This study has shown that the feeding behaviour of a small ruminant can be strongly affected by both rain and fly harassment. Thus, at tempts to relate the feeding behaviour of ungulate species to body size and the quanti ty of available forage should take these variables into account. It follows that comparisons between similar species, or between the sexes, may be invalid unless observa- tional data are collected under conditions where weather or fly abundance are similar.

The study has also shown that feral goats, whether farmed for pasture im- provement, fibre production or both, are likely to suffer least from the effects of rain and flies if provided with dry, man-made shelters. Provision of shelters would not only protect goats, but probably increase grouping behaviour and prevent straying.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Universities' Federation for Animal Welfare, the British Eco- logical Society and the Russell Trust for financial support. Moneylaws Farm and Nether Hindhope Farm helped with goat husbandry. We thank Peter Kin- near and the Nature Conservancy Council for permission to work at Tentsmuir Point N.N.R. and the many people who helped us catch goats. We are grateful for the constructive criticism of the manuscript by Dr. M.C. Appleby, Profes- sor P.J.B. Slater and two anonymous referees.

REFERENCES

Alexander, G., 1974. Heat loss from sheep. In: J.L. Monteith and L.E. Mount (Editors), Heat Loss from Animals and Man. Butterworths, London.

Altmann, J., 1974. Observational study of behaviour: sampling methods. Behaviour, 48: 227-267. Arnold, G.W. and Birrell, H., 1977. Food intake and grazing behaviour of sheep in varying body

condition. Anim. Prod., 24: 343-353.

4]

Arnold, G.W. and Dudzinski, M.L., 1978. Ethology of Free-Ranging Domestic Animals. Devel~ opments in Animal and Veterinary Sciences. 2. Elsevier, London.

Blaxter, R., Joyce, A. and Wainman, B., 1963. Effects of air velocity on heat losses in sheep and cattle. Nature (London), 198: 1115-1116.

Boyd, I.L., 1981. Population changes and distribution of a herd of feral goats (Capra sp.) on Rhum, Inner Hebrides 1960-78. J. Zool. (London), 193: 287-304.

Bullock, D.J. and Kinnear, P.K., 1988. The use of goats to control birch in dune systems: an experimental study. Aspects Appl. Biol., 16:163 - 168.

Duncan, P. and Vigne, N., 1979. The effects of group size in horses on the rates of attack by blood- sucking flies. Anim. Behav., 27: 623-625.

Espmark, Y. and Langvatn, R., 1979. Lying down as a means of reducing fly harassment in red deer. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 5:51 54.

Hoffmann, R.R., 1968. Comparisons of the rumen and omasum in East African game ruminants in relation to their feeding habits. In: M.A. Crawford (Editor), Comparative Nutrition of Wild Animals. Symp. Zool. London, 21, Zoological Society, London, pp. 179-194.

Hunter, A.R., 1975. Sheep headily disease in Britain. Vet. Rec., 97: 95-96. Jarman, P.J., 1974. The social organisation of antelope in relation to their ecology. Behaviour, 48:

215-267. Machlis, L., Dodd, P.W.D. and Fentress, J.C., 1985. The pooling fallacy: problems arising when

individuals contribute more than one observation to the data set. Z. Tierpsychol., 68:201 214. Siegel, S., 1956. Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioural Sciences. McGraw-Hill, Kogaku-

sha, Tokyo. Slater, P.J.B., 1974. The temporal pattern of feeding in the zebra finch. Anim. Behav., 22: 506-

515. Staines, B.W., 1976. The use of natural shelter by red deer in relation to weather in north-east

Scotland. J. Zool. (London), 180: 1-8. Titchener, R.R., Berlyn, A.D. and Newbold, J.W., 1974. Ecology and control of headfly attacking

sheep in the west of Scotland. Parasitology, 69: i-xxvii. White, R.G., Bunnell, F.L., Gaare, F., Skogland, T. and Hubert, B., 1981. In: L.C. Bliss, D.W.

Heal and J.J. Moore (Editors), Tundra Ecosystems - A Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 343-387.

Woollard, T.H. and Bullock, D.J., 1987. Effects of headily (Hydrotaea irritans, Fallen) infesta- tions and repellents on earflicking and headshaking behaviour of farmed red deer (Cervus eIaphus L.). Appl. Anita. Behav. Sci., 19: 41-49.