Driving Forces Behind Participation and Satisfaction with Social Networking Sites

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Driving Forces Behind Participation and Satisfaction with Social Networking Sites

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 33

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Keywords: DegreeofInfluence,Identification,InteractionPreference,Participation,Satisfaction,SNS,TAM,Word-of-Mouth,

INTRODUCTION

The concept of community emerges from the sociological perspective as a group of people linked by social ties, sharing common values and interests and having common meanings and expectations. In the context of consumer-brand relationships, Muñiz and O´Guinn (2001, p. 412) define brand community as a “specialized, non-geographically bound community, based on

a structured set of social relationships among admirers of a brand”. The online community is seen as a social relationship aggregation, in which members communicate and interact through the Internet (Rheingold, 2000) and share a specific objective (Blanchard & Markus, 2004). Members of such communities engage in knowledge sharing, problem solving and learning through posting and responding to questions, narrating personal experiences and

Driving Forces Behind Participation and Satisfaction with Social Networking SitesSandraMariaCorreiaLoureiro,MarketingProfessor(ISCTE-IUL),Departmentof

Marketing,OperationsandGeneralManagement,ISCTE-IULBusinessSchool,Lisbon,Portugal

F.JavierMiranda,AssociateProfessor(UniversidaddeExtremadura),BusinessManagementandSociologyDepartment,FacultaddeCienciasEconómicasyEmpresariales,Badajoz,

Spain.

AnaR.Pires,MasterinScience(UniversityofAveiro),DepartmentofEconomy,ManagementandIndustrialEngineering,UniversityofAveiro,Portugal,Aveiro,Portugal

ABSTRACTThisstudyaimstoinvestigatetheantecedentsofparticipationinandsatisfactionwithsocialnetworkingsites(SNS)basedonextensionoftheTechnologyAcceptanceModel.Themodelistestedonagroupof336youngadultswhouseFacebookfrequently.ThefindingsrevealthatidentificationwiththeSNSandthedegreeofinfluencearetwoimportantdriversoftheusefulnessoftheSNS,andinturn,leadtousingitmorefrequentlyandencouragingotherstojoin.InteractionpreferencecaninfluencefavourablythebeliefthattheSNSiseasytouse,however,easeofusedoesnotseemtocontributesignificantlytoindividualsparticipatingactivelyinSNS.

DOI: 10.4018/jvcsn.2012100103

34 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

discussing subjects relevant to the network (Toral, Martínez-Torres, Barrero, & Cortés, 2009; Lin, 2009).

Social networking sites (SNS) are online communities with specific characteristics. Boyd and Ellison (2007) argue that SNS allow indi-viduals to build a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, interact and share a connection with other users on a list, and view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. Unlike the Web, which is largely organized around content, online social networks are organized around users. The resulting social network provides a basis for maintaining social relationships, finding users with similar interests and locating content and knowledge that has been contrib-uted or endorsed by other users. Hence, users’ behaviour should be influenced not only by their own motivations, but also by other members within their online SNS (Li, 2011).

However, research into social media, and specifically SNS, is still at an embryonic stage (Michaelidou, Siamagka, & Christodoulides, 2011). Due to the complexity and dynamics of SNS in terms of the number of antecedents and the interactions among them, a single research method/model can neither provide a compre-hensive view in academia, nor provide the best solution to even a single problem in practice (Lee & Chen, 2011). Indeed, the driving forces behind SNS member participate, interact, and find new friends, as well as, the overall satisfac-tion toward usage SNS, are not yet well known and established. In order to contribute to fulfil this gap in literature, the major goal of this study is to analyze antecedents and outcomes of satisfaction and participation in social net-working sites. The proposed model integrates technology acceptance variables with relational and personality variables.

Following this introduction, we provide a theoretical foundation for the present study based on an extension of the Technology Ac-ceptance Model (TAM) and we characterize SNS. Then, section 3 presents a research model and proposes hypotheses to be tested. The next section describes the research methodology

of the empirical study, which is followed by the report on the testing of the hypotheses and discussion. Finally, we present conclusions, implications, limitations and suggestions for future research.

LITERATURE BACKGROUND

Social Networking Sites

According to Lesser, Fontaine and Slusher (2000), the concept of an online community has been at the core of the Internet since its birth. Initially, only scientists used the Internet to share knowledge, collaborate on research and exchange messages, but today people have many electronic tools for making contact through the Internet (Toral etal., 2009). Therefore, online communities enable people to engage in joint activities and discussion, help each other and share information (Raban & Rafaeli, 2007) beyond the boundaries of geography or time.

In recent decades, we have seen an explo-sion in popular interest in social networks, due to the popularization of new social networking sites (SNS), or web-based services that help people build a public profile, choose a list of users with whom they share a connection and view the public profiles of their list of con-nections (Lewis et al., 2008; Kwon & Wen, 2010). Consequently, SNS such as MySpace, Facebook, Hi5 or Twitter allow their users to link or make groups where they interact with other users who have analogous interests. These interests can be various: to maintain contact with friends and family, meet new people, share contents or media, summarize or acquire social capital (Kwon & Wen, 2010).

In the European Union (EU 27), in 2010, 80 percent of young Internet users are active on social media. Particularly, while the vast major-ity of Internet users (more than 80 percent) aged between 16 and 74 use e-mail, with regard to posting messages to chat sites, blogs and social networks, it is the youngest age-group (16-24), 80 percent, who do so, followed by 42 percent of individuals aged 25-54 years and only 18 percent of older people (55-74) (Seybert &

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 35

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Lööf, 2010).According to Nielsen (2012) social media report, during 2011 females make up the majority of visitors to social networks and blogs, and people aged 18-34 have the highest concentration of visitors among all age groups.

In the Portuguese context, 90 percent of young individuals aged 16-24 and 65 percent aged 25-54 post messages to chat sites, blogs and social networks (Seybert & Lööf, 2010). Therefore, young individuals are an appropriate target to study participation in, and satisfaction with SNS.

Facebook has emerged as a leading social networking site, with 845 million active users in February 2012. There are two implications for business firms: Facebook is a gathering place for a large pool of consumers and this social networking site is also a mine of consumer information and a means of spreading informa-tion to build market presence (Hsu, 2012). In Portugal, 73.5 percent of Internet users in the first half of 2010 accessed Facebook.com, so this SNS is the leading social site, according to MKT Portugal (2010) (see Figure 1).

Technology Acceptance Model

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is based on the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which states that human beliefs influ-ence attitudes and shape behavioural intentions (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Davis, 1989). Ajzen

(1991) extended the TRA adding perceived behaviour control and developing the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB).

The core factor of the Theory of Planned Behaviour is the individual’s intention to per-form a given behaviour, that is, “the intentions are assumed to capture the motivational factors that influence a behaviour; they are indications of how hard people are willing to try, of how much of an effort they are planning to exert, in order to perform the behaviour” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 181). The key lies in the idea that the stronger the intention to engage in a behaviour, the more likely its performance.

TPB presents three independent variables of intention. The first, attitude towards the behaviour, refers to the “degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable evalu-ation or appraisal of the behaviour in question” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188), the second variable is the subjective norm that focuses on the “perceived social pressure to carry out or not carry out the behaviour, and the third is the degree of perceived behavioural control, which refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour and it is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188). Here, the key is, “the more favourable the attitude and subjective norm with respect to a behaviour, and the greater the perceived behavioural control,

Figure1.SNS’s-Topsingleusers-1sthalfof2010

36 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

the stronger should be an individual’s intention to perform the behaviour under consideration” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188).

The TAM model (see Figure 2) focuses particularly on users’ acceptance of computer technology (Liu, 2010). At the core of the TAM model are two specific beliefs: perceived useful-ness and perceived ease of use. These beliefs determine people’s behavioural intention to use a technology, which in turn, influence subse-quent behaviour (Liu, 2010). Perceived useful-ness is a belief that the information technology or system will help the user in performing his/her task (Davis, 1989). Perceived ease of use is defined as the degree to which individuals believe that using a particular system will be free of effort (Chung & Tan, 2004).

Later, external variables of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Lee etal., 2003) were introduced in order to examine the usage-context factors that may influence users’ acceptance (Moon & Kim, 2001). Sev-eral studies introduced variables such as social influence, job relevance, image, quality, com-patibility, trust, computer self-efficacy, com-puter anxiety or computer playfulness, per-ceived enjoyment and objective usability (e.g. Venkatesh, 2000; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Chen, Gillenson, & Sherrell, 2002; Yu, Ha, Choi, & Rho, 2005; Liu, 2010; Huarng, Yu, & Huang, 2010). In the context of SNS, Kwon and Wen (2010) proposed social identity, altru-ism, and telepresence. Chen, Chen, Lin, & Chen (2011) develop a conceptual model that inte-grates the post-acceptance model of information system continuance with perceived ease-of-use

and perceived usefulness in the context of social networking. In this study, continuance intention is influenced by the relationship quality and information system quality.

Attitude towards using technology has been omitted in several extended models (e.g. Igbaria, Guimaraes, & Davis, 1995; Kwon & Wen, 2010) and perceived usefulness and per-ceived ease of use link directly to intentions.

Participation and Satisfaction as Attitudes

One of the basic mechanisms behind any type of community is members’ participation. Without participation, it will be difficult to share ideas, stories and traditions (Muñiz & O’Guinn, 2001), interact with other members with re-lated interests (Lewis etal., 2008), or help to solve problems through posting comments in blogs (Toral etal., 2009) or SNS. Participation in online communities, such as SNS, can be seen a general attitude or collective intention among the members to participate (Bagozzi & Dholakia, 2002; Lin, 2006).

In this vein, participation or the mechanism that makes online communities work has been studied mainly from two perspectives: i) social identity theory and the psychological sense of community (e.g. Bhattacharya, Rao, & Glynn, 1995; Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003; Carlson, Suter, & Brown, 2008) and ii) information system success models (e.g. Wachter, Gupta, & Quad-dus, 2000; DeLone & McLean, 2003; Wixom & Todd, 2005). The first perspective suggests that social identity, group behaviour (Bagozzi

Figure2.Technologyacceptancemodel(TAM)

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 37

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

& Dholakia, 2006) or perceived degree of influ-ence in the community (Algesheimer, Dholakia, & Herrmann, 2005; Nambisan & Baron, 2007; von Loewenfeld, 2006) can induce participa-tion in communities. The second perspective posits that system quality, information quality and service quality affect both user satisfaction and behavioural intention to use information systems. In this study we attempt to integrate the social identity perspective in the technology acceptance model (TAM), presenting both as drivers of participation and satisfaction with SNS.

Satisfaction has been analyzed from two perspectives: transactional and cumulative. In a transactional perspective customers evaluate or make a judgment of a specific service en-counter or consumption situation (e.g., Oliver, 1980; Anderson, Fornell & Lehmann, 1994), Comparatively, in a cumulative perspective, customer satisfaction is a holistic evaluation of the total purchase and consumption experience with a product over the time (Fornell et al., 1996). Oliver (1999) defines overall satisfac-tion as a cumulative process across a series of transactions or service encounters. Research has demonstrated empirically that the cumulative perspective is a superior predictor of behavioral intentions (e.g., Fornell etal., 1996; Loureiro, 2010). Therefore, in the current study satisfac-tion is considered as an overall evaluation or attitude toward usage SNS, regarding meet expectations and matching members’ interests and needs (McMillan & Chavis, 1986).

RESEARCH MODEL AND HYPOTHESES

Assuming that choice is voluntary, people adopt Facebook (or any other network technology) because they believe it will be useful in improv-ing their efficiency and effectiveness in com-municating their message and pictures. When performing the traditional behavioural intention models in information systems, research may be

modified and extended when they are applied to the study of adoption of Internet services (Yang & Lin, 2011).

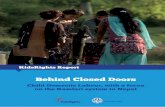

In this study we follow and extend the model proposed by Wixom and Todd (2005), but integrating the social perspective, less studied in the context of SNS, instead of in-formation system perspective. The proposed model introduces external variables to the two major belief constructs, i.e., perceived useful-ness and perceived ease of use (see Figure 3). Thereby, identification, degree of influence and interaction preference are regarded as external variables of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Satisfaction and participation in SNS are viewed as direct consequences or attitudes toward usage, which, in turn, lead to word-of-mouth and actual use. In the current study satisfaction is an overall evaluation or attitude toward usage SNS and in Wixom and Todd’s (2005) study satisfaction is an information and system evaluation shaped by beliefs (external variables) about the information system.

An individual who perceives usefulness and ease of use in SNS is more willing to in-teract and establish social contact and to be satisfied with it. Finally, when a member is engaged and actively participates in a com-munity, she/he is more willing to make positive word-of-mouth comments (e.g. Algesheimer etal., 2005; Kim & Jung, 2007; Muñiz & Schau, 2007) and will tend to use SNS frequently, spend more time on SNS, and expend more effort on SNS (actual use).

In order to better understand the antecedents of participation in, and satisfaction with social networking sites, this study regards constructs such as identification, degree of influence, interaction preference, usefulness and ease of use (see Figure 3). The first three variables are based on psychological sense of community and are regarded as being drivers for ensur-ing a brand community’s customer participa-tion (Algesheimer etal., 2005; Nambisan & Baron, 2007; von Loewenfeld, 2006), as well

38 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

as online community’s member participation (Woisetschläger etal., 2008). As noticed, online community are social relationship aggregation, in which members communicate and interact through the Internet (Rheingold, 2000) and share a specific objective (Blanchard & Markus, 2004), like Facebook and other SNSs.

McMillan and Chavis (1986) define the concept of psychological sense of community as a feeling members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to being together. Thus, psychological sense of commu-nity comprises several elements: membership, influence, integration and fulfilment of needs, and shared emotions.

Members of a group must feel they have influence over the group and the group depends on the influence exercised on its members (McMillan & Chavis, 1986). Integration and fulfilment of needs means the interdependence with other members, a willingness to maintain this interdependence by doing for others what one expects from them (Sarason, 1974). Shared emotions increase the likelihood that people will become close and facilitates a group bond. Membership of the community involves emo-

tional safety to reveal real feelings, a sense of belonging and identification, common symbol systems, language, dress and rituals.

Antecedents of Ease of Use and Usefulness

Identification is a concept established in the field of psychology and has been adapted for the marketing context. Therefore, brand identifica-tion can be defined as the consumer’s perception of similarity between him/herself and the brand (e.g. Bagozzi & Dholakia, 2006; Bergami & Bagozzi, 2000). Consumer identification with an organization is based on his/her perceptions of its core values, mission and leadership (e.g. Whetten & Godfrey, 1998; Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003). Indeed, social identification is the perception of belonging to a group with the result that an individual identifies with that group (Bhattacharya et al., 1995). The indi-vidual’s specific characteristics and interests are similar to those of the group. Bagozzi and Dholakia (2006) found that social identity is the cognitive self-awareness of membership of the brand community, affective commitment and perceived importance of membership.

Figure3.Conceptualmodel

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 39

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Social identification has been proposed as a crucial determinant that affects the inten-tion to use a specific technology or system in virtual community service settings (Song & Kim, 2006). In the case of SNS, the group is the social network community. In order to be identified with SNS, members should feel they belong to the community, perceive the impor-tance of membership and view themselves in many aspects of the community. The identifica-tion can influence the individual behavioural beliefs about using a SNS system, this means, the degree to which an individual believes that using the SNS which she/he identifies would enhance her/his job performance (usefulness) and would be at least almost free of effort, due to the motivation for the SNS (ease of use). Hence, the current study suggests that identity with SNS will positively influence perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, and so the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: Identification has a positive effect on ease of use,

H1b: Identification has a positive effect on usefulness.

Interaction preference is another variable that could influence how SNS work and the individual behavioural beliefs about using a SNS system. According to Wiertz and de Ruyter (2007), the preference for an online community is defined as an individual’s prevailing tendency to interact with relative strangers in an online environment. Therefore, an individual who enjoys interacting and exchanging with other members and likes actively participating in discussions online is more willing to believe that SNS facilitate participation, would enhance his/her job performance and that using an SNS does not require much effort (usefulness and ease of use). We therefore hypothesized that:

H2a: Interaction preference has a positive effect on ease of use,

H2b: Interaction preference has a positive effect on usefulness.

Besides identification and interaction pref-erence, other aspects such as degree of influence are important in motivating participation inside the community. Degree of influence is related to the concept of self-efficacy. The psychological theory of psychological sense of community, proposed by Chavis etal. (1986), discusses the concept of influence for members as the feeling they have some control and influence within the community. This theory was first developed in a neighbourhood context, but later applied to relational communities, such as Internet com-munities (Obst, Zinkiewicz, & Smith, 2002). As Bandura (1986) proposes, a high degree of influence should mean more willingness to engage in the community. Thereby, degree of influence in the SNS context should also be regarded as the feeling of control over the use of technology and consequently being engaged in the network. Indeed, an individual who believes in their ability and skill in using SNS will be more active using the network and will perceive that SNS are useful and easy to use. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: Degree of influence has a positive effect on ease of use,

H3b: Degree of influence has a positive effect on usefulness.

Concerning the two main beliefs of TAM, ease of use and usefulness, they have been seen as linked, since several studies demonstrate the significant influence of perceived ease of use on perceived usefulness (e.g., Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Kwon & Wen, 2010; Yang & Lin, 2011). Therefore it is argued that:

H4: Ease of use has a positive effect on use-fulness.

Direct Antecedents of Participation and Satisfaction

Participation and interaction in SNS may occur in many ways. Individuals in SNS can perform several activities such as: share information,

40 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

seek advice, give advice, find new friends, communicate events and organize events (von Loewenfeld, 2006). These forms of interaction enable consumers to share information, support each other and develop social bonds. Hence, an individual more aware of the potentiality of the SNS, with the skills and knowledge to operate SNS and believing that the SNS will help in performing acts and tasks, is more willing to interact and establish social contact through SNS (e.g. Teo etal., 2003):

H5a: Ease of use has a positive effect on par-ticipation,

H5b: Usefulness has a positive effect on par-ticipation.

Satisfaction is recognized as one of the important and widely studied concepts in mar-keting. The concept is regarded as an emotional reaction to a specific goods/service encounter, and this reaction comes from disconfirmation between the consumer´s perceived performance and the consumer´s expectation (e.g. Mano & Oliver, 1993; Swan & Oliver, 1989; Tse & Wilton, 1988). It is also viewed as the overall evaluation performance and based on prior experiences (e,g. Anderson & Fornell, 1994; McDougall & Levesque, 2000). Although satisfaction/dissatisfaction studies tradition-ally assume a cognitive focus (Oliver, 1980), nowadays researchers consider it a cognitive phenomenon with affective elements (e.g. Wirtz & Bateson, 1999; Wirtz, Mattila, & Tan, 2000). Indeed, an individual who knows how to operate SNS, generally using SNS for several activities believing that the technology can help in their connection inside the network and that using the technology does not require too much ef-fort, is more likely to be satisfied with his/her activities in SNS. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a: Ease of use has a positive effect on sat-isfaction,

H6b: Usefulness has a positive effect on sat-isfaction.

Consequents of Participation and Satisfaction

In this study, satisfaction and participation in SNS are considered as positive attitudes towards use of social networking. Behavioural inten-tions, such as word-of-mouth, and even actual use are in turn determined by the individual’s attitude towards the use of technology (e.g. Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen, 1991; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Wixom & Todd, 2005; Kwon & Wen, 2010). Therefore, when a member of an SNS is engaged and actively participates in a community, she/he is more willing to make positive word-of-mouth comments (e.g. Algesheimer etal., 2005; Kim & Jung, 2007; Muñiz & Schau, 2007), and tends to use SNS frequently, spends more time on SNS, and puts more effort into SNS (actual use). Consequently, the following hypotheses are suggested:

H7a: Participation has a positive effect on actual use,

H7b: Participation has a positive effect on word-of mouth.

Satisfaction is widely regarded as influenc-ing intention behaviour (e.g., Oliver, 1999) and even actual use. The link between satisfaction and intentions has been analyzed in several contexts, such as banking services, airline ser-vices, health services, education services (e.g., An & Noh, 2009; Thuy & Hau, 2010; Hau & Thuy, 2012; Chang etal., 2012), tourism service and destination (e.g. Loureiro 2010; Yuksel etal., 2010) and online stores (e.g. Finn, 2005). Therefore, we posit that an individual satisfied using an SNS is more willing to speak positively to others, recommend it and encourage others to join, as well as using the SNS more frequently. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H8a: Satisfaction has a positive effect on actual use,

H8b: Satisfaction has a positive effect on word-of mouth.

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 41

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

METHOD

Sample Characteristics

Drawing from the literature review, the question-naire that operationalized the latent variables and the socio-demographic variables was pre-tested on ten young adults (5 full-time students and 5 working students) who were personally interviewed. Minor changes were made based on their suggestions. Then, the questionnaire was accessible through a link posted in Face-book and other SNS (Hi5, Twitter, Linkedin). The sample process began as a convenience sample, asking a group of university students to participate by posting the link in their SNS. The students were instructed to recruit other participants, which developed into snowball sampling as more participants recommended other participants (Goodman, 1961; Walsh & Beatty, 2007).

Therefore, 415 young adults completed the questionnaire but most of them, 336 (81%) post more frequently in Facebook and the remaining 19% in several other SNSs. In order to avoid bias (because the majority use Facebook and also the fact that the internal structures and the purposes of the SNS are different), we use data of the 336 young adults who post more frequently in Facebook. Student behaviour is a good proxy for actual online behaviour in using social networking sites, since statistics show young people to be the dominant Internet users (Zickuhr & Smith, 2012), and most (80%) young Internet users (16-24 years) in the European Union post messages to chat sites, blogs or social networking sites (Seybert & Lööf, 2010). The sample consisted of 48.2% male participants and 51.8% female participants; the average age was 22 years and standard deviation 2.7.

Measurement

The items in the questionnaire were first written in English (based on previous studies), trans-lated into Portuguese, and then back translated

to English. Back translation was used to ensure that the items in Portuguese communicated similar information to those in English (Sekaran, 1983) meaning that conceptual equivalence was assured.

The nine latent variables in this study were measured by means of multi-item 5 point Likert-type scales (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). Identification, satisfaction, degree of influence and participation were adapted from von Loewenfeld (2006). Ease of use, usefulness and actual use are based on Thong etal. (2002) and Davis et al. (1989). Interaction prefer-ence is based on Wiertz and Ruyter (2007). Finally, word-of mouth is assessed based on Algesheimer etal. (2005) and Loureiro (2010).

Data Analysis

In this study a PLS approach is used, which employs a component-based approach for es-timation purposes (Lohmöller, 1989). As Wold (1985) wrote, “in large, complex models with latent variables, PLS is virtually without compe-tition” (p. 590). In terms of analysis advantages, PLS simultaneously estimates path coefficients and individual item loadings in the context of a specified model. As a result, it enables research-ers to avoid biased and inconsistent parameter estimates. On the basis of recent developments (Chin, Marcolin, & Newsted, 2003), PLS has been found to be an effective analytical tool to test interactions by reducing Type II errors. By creating a latent construct that represents an interaction term, a PLS approach significantly reduces this problem by accounting for error related to the measures (Echambadi, Campbell, & Agarwal, 2006).

The PLS model is analysed and interpreted in two stages. First, the suitability of the mea-sures is assessed by evaluating the reliability of the individual measures and the discriminant validity of the constructs (Hulland, 1999). Then the structural model is appraised. Composite reliability is used to analyse the reliability of

42 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

the constructs. To determine convergent valid-ity, we used the average variance of variables extracted by constructs (AVE), which should be at least 0.5, and to assess discriminant validity we follow the rule that the square root of AVE should be greater than the correlation between the construct and other constructs in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Bootstrap is used to estimate the precision of the PLS estimates and to analyse the significance of the beta coef-ficients. Tenenhaus etal. (2005) proposed the geometric mean of the average communality and the average R2 (from 0 to 1) as overall goodness of fit (GoF) measures for PLS.

RESULTS

First, the suitability of the measures is assessed by evaluating the reliability of the individual measures and the discriminant validity of the constructs. All factor loadings of reflective constructs exceed 0.707 (the lowest value is 0.741), which indicates that more than 50% of the variance in the manifest variable is ex-plained by the construct (Carmines & Zeller, 1979). All constructs in the model satisfied the requirements for reliability (composite reliability greater than 0.70) and convergent validity (Table 1).

The measures also demonstrate discrimi-nant validity, according to the criteria defined in Methods. As showed in Table 2, the diagonal elements are greater than corresponding off-diagonal elements.

The figures in the sub-diagonal are cor-relation coefficients and the bold figures in the diagonal represent square root of AVE.

Central criteria for evaluation of the inner model comprise R2 and the Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) index by Tenenhaus etal. (2005). All values of the cross-validated redundancy measure Q2 (Stone-Geisser-Test) are positive, indicating high predictive power of the ex-ogenous constructs (Chin, 1998). The model demonstrated a high level of predictive power

for participation as the modelled constructs explained 69.6% of the variance in participa-tion, 70.4% of the variance in satisfaction, 54.2% of the variance in actual use and 77.7% of the variance in word-of-mouth. The aver-age communality of all reflective measures is high, leading to a good GoF outcome (0.70). In this study, a nonparametric approach, named Bootstrap, was used to estimate the precision of the PLS estimates. So, twelve of fifteen path coefficients are significant at a level of 0.001, 0.01 or 0.05 (see Figure 4).

Table 3 shows that the total effects of the relationships are significant except for the causal order from identification to ease of use.

In fact, interaction preference and degree of influence are found to be positively related to ease of use (β = 0.266, p<0.05 and β = 0.302, p<0.05, respectively), thus supporting H2a and H3a. Identification and degree of influence are significantly related to usefulness (β = 0.274, p<0.05 and β = 0.206, p<0.05, respectively), supporting H1b and H3b. Ease of use has a positive effect on usefulness (β = 0.348, p<0.001), supporting H4.Then, usefulness is found to be positively directly related to par-ticipation (β = 0.767, p<0.001), thus supporting H5b, and both ease of use and usefulness are found to be related to satisfaction (β = 0.462, p<0.001 and β = 0.430, p<0.001, respectively), supporting H6a and H6b. Participation and satisfaction are positively related to actual use (β = 0.221, p<0.05 and β = 0.551, p<0.001, respectively), which support H7a and H8a. Finally, participation and satisfaction are posi-tively related to word-of-mouth (β = 0.389, p<0.001 and β = 0.543, p<0.001, respectively), which supports H7b and H8b.

DISCUSSION

The results found in the current study lead us to point out several aspects about antecedents and outcomes of participation and satisfaction with SNS, especially Facebook (since the data

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 43

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

continuedonthefollowingpage

Table1.Measurementresults

Construct Item Loading

LV Mean Alpha CR AVE*

Identification 2.78 0.907 0.926 0.643

V5 I see myself as belonging to this SNS 0.761

V8 I see myself as a typical and representative member of this SNS 0.741

V12 This SNS plays a part in my everyday life. 0.850

V14 This SNS confirms in many aspects my view of who I am. 0.823

V16 I can identify with this SNS. 0.852

V18 I have strong feelings for this SNS 0.791

V30 I feel like I belong in this SNS 0.786

Interaction Preference 2.81 0.789 0.876 0.703

V28 I am someone who likes actively participating in discus-sions with other SNS members 0.805

V29 In general, I thoroughly enjoy exchanging ideas with other SNS members 0.856

V27 am someone who enjoys interacting with other SNS members. 0.853

Degree of Influence 2.83 0.782 0.873 0.697

V9 As a member of SNS, I can influence the community as a whole. 0.802

V10 I am satisfied with the degree of influence to shape this SNS. 0.847

V11 A single member has the chance to be an active part in this SNS. 0.855

Ease of Use 3.29 0.724 0.876 0.780

V38 I find this SNS easy to use 0.920

V42 The process of using the SNS is clear and understandable 0.844

Usefulness 3.16 0.878 0.916 0.732

V6 Using this SNS enables me to acquire more information or meet more people 0.827

V37 This SNS is a useful service for communication 0.873

V40 This SNS is a useful service for interaction of members 0.865

V41 Using the SNS would improve my efficiency in sharing information and connecting with others 0.858

Participation 2.87 0.897 0.924 0.708

V7 Members of this SNS help each other 0.824

V13 When I seek advice, I am likely to find someone sup-portive in this SNS 0.814

44 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

used in data treatment relate to such SNS).Identification with the SNS, particularly with Facebook, together with the degree of influ-ence to shape the social network, are the bases to explain usefulness. Individuals who enjoy participating in discussions, exchanging ideas

and interacting with other members and those who actively influence the SNS are more likely to find the SNS easy to use. Therefore, the degree of influence is an important aspect in considering the SNS easy to use and useful. This study also confirmed that ease of use has

Table1.Continued

Table2.Discriminantvalidity

Construct 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1.WM 0.909

2.Actual Use 0.699 0.921

3.Ease of use 0.708 0.534 0.833

4.Degree of Influence 0.724 0.631 0.633 0835

5.Identification 0.853 0.742 0.652 0.793 0.802

6.Interaction Preference 0.846 0.692 0.631 0.683 0.843 0.838

7.Participation 0.814 0.651 0.674 0.757 0.887 0.812 0.842

8.Satisfaction 0.847 0.724 0.793 0.722 0.817 0.766 0.781 0.874

9.Usefulness 0.831 0.608 0.768 0.763 0.812 0.767 0.832 0.785 0.856

Construct Item Loading

LV Mean Alpha CR AVE*

V15 I found new friends as a result of joining this SNS 0.833

V17 Friendships in this SNS are important to me. 0.849

V19 Social contacts and friendships are supported by this SNS community’s interaction possibilities 0.886

Satisfaction 2.98 0.845 0.906 0.764

V20 Overall, this SNS meets my expectations 0.894

V21The content of this SNS matches my interests exactly. 0.873

V24 This SNS fulfils my needs. 0.855

Actual Use 3.22 0.822 0.917 0.848

V1 I tend to use this SNS frequently 0.905

V2 I spend a lot of time on SNS 0.936

WOM 3.03 0.895 0.934 0.826

V31 I have said positive things about this SNS to other people 0.904

V32 I have recommended this SNS to people who seek my advice. 0.917

V33 I have encouraged other people to join this SNS. 0.905

*AVE: Average Variance Extracted; CR: Composite Reliability; Cranach’s Alpha

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 45

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Figure4.Structuralresults

Table3.Standardizeddirectandtotaleffectsbetweenconstructs

PathsStandardized

Coefficient Direct Effect

Standardized Coefficient Total Effect

Hypotheses Results

Identification -> Ease of use 0.189 ns 0.189 ns H1a:not accepted

Identification-> Usefulness 0.274* 0.339** H1b:accepted

Interaction Preference -> Ease of use 0.266* 0.266* H2a:accepted

Interaction Preference -> Usefulness 0.176 ns 0.269*H2b:accepted regard-ing the total effect

Degree of influence -> Ease of use 0.302* 0.302* H3a:accepted

Degree of influence -> Usefulness 0.206* 0.311** H3b:accepted

Ease of use -> Usefulness 0.348*** 0.348*** H4:accepted

Ease of use -> Participation 0.086 ns 0.352 ***H5a:accepted regard-ing the total effect

Usefulness -> Participation 0.767*** 0.767*** H5b:accepted

Ease of use -> Satisfaction 0.462*** 0.612*** H6a:accepted

Usefulness -> Satisfaction 0.430*** 0.430*** H6b:accepted

Participation -> Actual use 0.221* 0.221* H7a:accepted

Participation -> WOM 0.389*** 0.389*** H7b:accepted

Satisfaction -> Actual use 0.551*** 0.551*** H8a:accepted

Satisfaction -> WOM 0.543*** 0.543*** H8b:accepted

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; p<0.001; ns: not significant

46 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

a positive impact on usefulness, as is suggested by several researchers (e.g., Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Kwon & Wen, 2010).

When we turn to the total effect, only the causal order from identification to ease of use is not supported. These empirical findings high-light, for the first time, the particular importance of the individual’s identification with the social network and the degree of influence to believe in its usefulness. Furthermore, identification does not have a significant effect on ease of use, which is in accordance with the findings of Kwon and Wen (2010).

Usefulness and ease of use influence positively the satisfaction with SNS, but the direct effect of ease of use on participation is not significant. Thereby, usefulness, together with identification and degree of influence seem to be important direct and indirect drivers for satisfaction and participation in SNS. An indi-vidual tends to be more connected to the SNS, feel that members help each other, find new friends and social interaction, and believe that the SNS fulfils his/her needs when he/she identi-fies with the SNS, can influence the network, and find the SNS useful. The empirical find-ings are in accordance with previous research (e.g. Algesheimer etal., 2005; Kim & Jung, 2007; Muñiz & Schau, 2007) in the context of online and offline communities, which points to identification and degree of influence as di-rect antecedents of participation. In this study, we analyse as favourable the indirect effect of identification and participation on participation through usefulness.

The consequences of participation and be-ing satisfied as a member of an SNS are active engagement in recommending the network and all activities to others and the tendency to use the SNS frequently. Finally, an individual who is more aware of the potentiality of the SNS, with the skills and knowledge to operate the SNS, this means, an individual that believes that using a SNS would be free of effort (ease of use) is not necessarily more willing to interact and establish social contact through SNS (e.g. Teo etal., 2003).

Regarding theoretical implications, social identity and the psychological sense of commu-nity variables are proved to be important external variables of behavioural beliefs and these, in turn, influence satisfaction and participation in SNS communities. In this study, trust in SNS system was not explored as an individual construct. However, in previous studies trust has been regarded as an important factor to increase the engagement within the community. Moreover, the existence of control options gives users the feeling of being protected and therefore increase trust within the community (Krasnova etal., 2010). In fact, Krasnova etal. (2010) point out that it is possible that the easy to use generates the strong feeling of control on the system. Thereby, the findings in the current research are in accordance with this point, this means, despite the effect of trust on participation and satisfaction was not analyzed, the meaning of trust appear undercover behind behavioral believes such as usefulness and ease of use. An individual that believes in the usefulness of the system (SNS) and that using the system will be free of effort will tend to use that system with more pleasure and trustfulness.

CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH

This study provides a model integrating tech-nology acceptance variables with relational and personality variables in order to consider antecedents and outcomes of participation in social networking sites, providing an insight into social network sites, the study of which is scarce.

To sum up, the current model has been confirmed by the results, with all hypotheses supported, except for the relationships between identification and ease of use, ease of use and participation, and between preference interac-tion and usefulness. Thus, we conclude that the proposed variables are good predictors of participation and satisfaction. However, iden-tification, perceived usefulness, and interaction

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 47

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

preference are the most important antecedents influencing participation. Of course, identifi-cation and interaction preference are acting as indirect antecedents of participation. Degree of influence and identification exercise an indirect effect on participation through perceived useful-ness. Participation in social networking sites, in turn, is linked to higher levels of actual use and word-of–mouth. Satisfaction with the online social network is a function of ease of use and usefulness, and exercises a direct and significant influence on actual use and word-of-mouth.

Managers that decide to put their brands on social networking sites should be aware of these insights. The more identified a commu-nity member is, and the greater the perceived usefulness and perceived influence, the more willing he/she will be to keep the community alive through interacting with other members. More active, participating members are more willing to communicate about the group in question to others, and this could be a good ve-hicle to promote brands and companies. Active members tend to be natural leaders who lead the group around a theme, interest, cause or brand.

In future, different member profiles should be categorized in order to better understand the characteristics of leaders and followers among members of social networking sites. Since the sample used in this study consisted mainly of individuals between 16 and 24 years old, we have to be careful if we want to use the results to explain all generations’ participation in social networks. Thus, a comparative study between different age groups would be interesting in order to evaluate differences in results. Another suggestion for future research concerns study of the influence of differences between indi-viduals, such as personality, past experience of participation and satisfaction with the SNS.

Future research could examine other factors such as security, trust, reliability, enjoyment and group affiliation to improve the explanatory power. In addition, the sample could include non adopters as they may be driven by dif-ferent factors. Future research could also use respondents from different cultures in order to allow greater generalisation of results.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human DecisionProcesses, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Ev-idence from European car clubs. JournalofMarket-ing, 69(3), 19–34. doi:10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363.

An, M., & Noh, Y. (2009). Airline customer satisfac-tion and loyalty: Impact of in-flight service qual-ity. ServiceBusiness, 3(3), 293–307. doi:10.1007/s11628-009-0068-4.

Anderson, E. W., & Fornell, C. (1994). A customer satisfaction research prospectus. In R. T. Rust, & R. L. Oliver (Eds.), Servicequality:Newdirectionsintheoryandpractice (pp. 241–268). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781452229102.n11.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Lehmann, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share and profitability: Findings from Sweden. JournalofMar-keting, 58(2), 112–122. Retrieved from http://web.itu.edu.tr/~elmadaga/MKT/Principles%20of%20MKT-master%20articles/Anderson%201994.pdf.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. D. (2006). Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. InternationalJournal of Research inMarketing, 23(1), 45–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.01.005.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. M. (2002). Inten-tional social action in virtual communities. JournalofInteractiveMarketing, 16(2), 2–21. doi:10.1002/dir.10006.

Bandura, A. (1986). Socialfoundationsofthoughtandaction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bergami, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2000). Self-categori-zation, affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organi-zation. TheBritishJournalofSocialPsychology, 39(4), 555–577. doi:10.1348/014466600164633 PMID:11190685.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Rao, H., & Glynn, M. A. (1995). Understanding the bond of identification: An investigation of its correlates among art museum members. Journal of Marketing, 59(4), 46–57. doi:10.2307/1252327.

48 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer-company identification: A framework for under-standing consumers’ relationships with companies. JournalofMarketing, 67(2), 76–89. doi:10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609.

Blanchard, A. L., & Markus, M. L. (2004). The experienced ‘sense’ of a virtual community: characteristics and processes. TheData Base forAdvances in Information Systems, 35(1), 64–79. doi:10.1145/968464.968470.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journalof Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x.

Carlson, B. D., Suter, T. A., & Brown, T. J. (2008). Social versus psychological brand community: The role of psychological sense of brand community. Journal of Business Research, 61(4), 284–291. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.022.

E. G. Carmines, & R. A. Zeller (Eds.). (1979). Reli-abilityandvalidityassessment. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Chang, H. H., Jeng, D. J. F., & Hamid, M. R. A. (2012). (in press). Conceptualizing consumers’ word-of-mouth behavior intention: Evidence from a university education services in Malaysia. ServiceBusiness. doi: doi:10.1007/s11628-012-0142-1.

Chavis, D., Hogge, J., McMillan, D., & Wandersman, A. (1986). Sense of commu-nity through Brunswick’s lens: A first look. JournalofCommunityPsychology, 14(1), 24–40. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<24::AID-JCOP2290140104>3.0.CO;2-P.

Chen, L., Gillenson, M. L., & Sherrell, D. L. (2002). Enciting online consumers: An extended technology acceptance perspective. Information&Management, 39(8), 705–719. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00127-6.

Chen, S.-C., Chen, H.-H., Lin, M.-T., & Chen, Y.-B. (2011). A conceptual model to understand the effects of perception on the continuance intention in Face-book. AustralianJournalofBusinessandManage-mentResearch, 1(8), 29–34. Retrieved from http://www.ajbmr.com/articlepdf/AJBMR_17_45i1n8a5.pdf.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares ap-proach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), ModernMethods forBusinessResearch (pp. 239–252). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publisher.

Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable mod-eling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail emotion/ adoption study. InformationSystems Research, 14(2), 189–217. doi:10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018.

Chung, J., & Tan, F. B. (2004). Antecedent of per-ceived playfulness: An exploratory study on user acceptance of general information-searching Web sites. Information&Management, 4(7), 869–881. doi:10.1016/j.im.2003.08.016.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information tech-nology. ManagementInformationSystemsQuarterly, 13(3), 319–340. doi:10.2307/249008.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. JournalofManagementInformationSystems, 19, 9–30. Retrieved from http://www.asiaa.sinica.edu.tw/~ccchiang/GILIS/LIS/p9-Delone.pdf.

Echambadi, R., Campbell, B., & Agarwal, R. (2006). Encouraging best practice in quantitative manage-ment research: An incomplete list of opportunities. JournalofManagementStudies, 43(8), 1801–1820. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00660.x.

Finn, A. (2005). Reassessing the foundations of customer delight. JournalofServiceResearch, 8(2), 103–116. doi:10.1177/1094670505279340.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief,attitude,intention,andbehavior:Anintroductiontotheoryandresearch. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. B. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d5fa40f1-43dd-4465-9740-279ac4e6ae83%40sessionmgr114&vid=11&hid=123 doi:10.2307/1251898.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural models with unobservable variables and measurement error. JMR, Journal of MarketingResearch, 18(1), 39–50. Retrieved from http://faculty-gsb.stanford.edu/larcker/PDF/6%20Unob-servable%20Variables.pdf doi:10.2307/3151312.

Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. An-nals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1), 148–170. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177705148.

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 49

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Hau, L. N., & Thuy, P. N. (2012). Impact of service personal values on service value and customer loy-alty: A cross-service industry study. ServiceBusiness, 6(2), 137–155. doi:10.1007/s11628-011-0121-y.

Hsu, Y.-L. (2012). Facebook as international eMar-keting strategy of Taiwan hotels. InternationalJournalofHospitalityManagement, 31(3), 972–980. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.11.005.

http://cn.nielsen.com/documents/Nielsen-Social-Media-Report_FINAL_090911.pdf.

Huarng, K.-H., Yu, T. H.-K., & Huang, J. J. (2010). The impacts of instructional video advertising on customer purchasing intentions on the Internet. ServiceBusiness, 4(1), 27–36. doi:10.1007/s11628-009-0081-7.

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic ManagementJournal, 20(2), 195–204. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7.

Igbaria, M., Guimaraes, T., & Davis, G. B. (1995). Testing the determinants of microcomputer usage via a structural equation model. JournalofManage-mentInformationSystems, 11(4), 87–114. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d5fa40f1-43dd-4465-9740-279ac4e6ae83%40sessionmgr114&vid=5&hid=123.

Kim, K. H., & Jung, Y. M. (2007). Website evalua-tion factors and virtual community loyalty in Korea. AdvancesinInternationalMarketing, 18, 231–252. doi:10.1016/S1474-7979(06)18010-2.

Krasnova, H., Spiekermann, S., Koroleva, K., & Hildebrand, T. (2010). Online social networks: Why we disclose. Journal of Information Technology, 25(2), 109–125. doi:10.1057/jit.2010.6.

Kwon, O., & Wen, Y. (2010). An empirical study of the factors affecting social network service use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 254–263. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.04.011.

Lee, S. M., & Chen, L. (2011). An integrative research framework for the online social network service. Service Business, 5(3), 259–276. doi:10.1007/s11628-011-0113-y.

Lee, Y., Kozar, K. A., & Larsen, K. R. T. (2003). The technology acceptance model: Past, present, and future. Communications of the Associationfor Information Systems, 12, 752–780. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d5fa40f1-43dd-4465-9740-279ac4e6ae83%40sessionmgr114&vid=5&hid=123.

Lesser, E. L., Fontaine, M. A., & Slusher, J. A. (2000). Knowledgeandcommunities. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Lewis, K., Kaufman, J., Gonzalez, M., Wimmer, A., & Christakis, N. (2008). Tastes, ties and time: A new social network dataset using Facebook.com. Social Networks, 30(4), 330–342. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2008.07.002.

Li, D. C. (2011). Online social network acceptance: A social perspective. Internet Research, 21(5), 562–580. doi:10.1108/10662241111176371.

Lim, S., Trimi, S., & Lee, H.-H. (2010). Web 2.0 service adoption and entrepreneurial orientation. Service Business, 4(3/4), 197–207. doi:10.1007/s11628-010-0097-z.

Lin, H.-F. (2006). Understanding behavioral inten-tion to participate in virtual communities. Cyber-psychology&Behavior, 9, 540–547. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9.540 PMID:17034320.

Liu, X. (2010). Empirical testing of a theo-retical extension of the technology acceptance model: An exploratory study of educational wikis. Communication Education, 59(1), 52–69. doi:10.1080/03634520903431745.

Lohmöller, J. B. (1989). The PLS program system: La-tent variables path analysis with partial least squares estimation. MultivariateBehavioralResearch, 23(1), 125–127. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2301_7.

Loureiro, S. M. C. (2010). Satisfying and delight-ing the rural tourists. JournalofTravel&TourismMarketing, 27(4), 396–408. doi:10.1080/10548408.2010.481580.

Mano, H., & Oliver, R. L. (1993). Assessing the dimensionality and structure of the consumption experience: Evaluation, feeling and satisfaction. TheJournalofConsumerResearch, 20(3), 451–466. doi:10.1086/209361.

Marktest. (2011). Marktest – netpanel. Retrieved November 20, 2012, from http://www.marktest.com/wap/a/n/id~15d9.aspx

McDougall, G., & Levesque, T. (2000). Customer satisfaction with services: Putting perceived value into the equation. Journalof ServicesMarketing, 14(5), 392–410. doi:10.1108/08876040010340937.

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. AmericanJournal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I.

50 International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A theory and definition.

Michaelidou, N., Siamagka, N. T., & Christodoulides, G. (2011). Usage, barriers and measurement of social media marketing: An exploratory investigation of small and medium B2B brands. IndustrialMarket-ingManagement, 40(7), 1153–1159. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.09.009.

Moon, J. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2001). Extending the TAM for a world-wide-web context. Information&Management, 38(4), 217–230. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(00)00061-6.

Muñiz, A. M. Jr, & O’Guinn, T. C. (2001). Brand community. The Journal of Consumer Research, 27(4), 412–432. doi:10.1086/319618.

Muñiz, A. M. Jr, & Schau, H. J. (2007). Vigilante marketing and consumer-created communications. JournalofAdvertising, 36(3), 35–50. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367360303.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2007). Interactions in virtual customer environments: Implications for product support and customer relationship manage-ment. JournalofInteractiveMarketing, 21(2), 42–62. doi:10.1002/dir.20077.

Nielsen (2012). Nielsen-social-media-report. Re-trieved November 20, 2012, from http://cn.nielsen.com/documents/Nielsen-Social-Media-Report_FI-NAL_090911.pdf

Obst, P., Zinkiewicz, L., & Smith, S. (2002). An ex-ploration of sense of community, Part 3: Dimensions and predictors of psychological sense of community in geographical communities. JournalofCommunityPsychology, 30(1), 119–133. doi:10.1002/jcop.1054.

Oliver, R. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 33–44. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d5fa40f1-43dd-4465-9740-279ac4e6ae83%40sessionmgr114&vid=8&hid=123 doi:10.2307/1252099.

Raban, D. R., & Rafaeli, S. (2007). Investigating ownership and the willingness to share informa-tion online. ComputersinHumanBehavior, 23(5), 2367–2382. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2006.03.013.

Rheingold, H. (2000). The virtual community:Homesteadingontheelectronicfrontier (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sarason, S. B. (1974). Thepsychologicalsenseofcommunity:Prospectsforacommunitypsychology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sekaran, U. (1983). Methodological and theoretical issues and advancements in cross-cultural research. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2), 61–73. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490519.

Seybert, H., & Lööf, A. (2010). Internetusagein2010–HouseholdsandIndividuals:Eurostatdata. Retrieved February 20, 2011 from http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-QA-10-050/EN/KS-QA-10-050-EN.PDF

Song, J., & Kim, Y. J. (2006). Social influence process in the acceptance of a virtual community service. Information Systems Frontiers, 8(3), 241–252. doi:10.1007/s10796-006-8782-0.

Swan, J. E., & Oliver, R. L. (1989). Postpurchase communication by consumers. JournalofRetailing, 65(4), 516–533. Retrieved from http://web.ebsco-host.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d5fa40f1-43dd-4465-9740-279ac4e6ae83%40sessionmgr114&vid=10&hid=123.

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Assessing IT us-age: The role of prior experience. ManagementInformation Systems Quarterly, 19(2), 561–570. doi:10.2307/249633.

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computa-tionalStatistics&DataAnalysis, 48(1), 159–205. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005.

Teo, H. H., Chan, H. C., Wei, K. K., & Zhang, Z. (2003). Evaluating information accessibility and community adaptivity features for sustaining vir-tual learning communities. International Journalof Human-Computer Studies, 59(5), 671–697. doi:10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00087-9.

Thuy, P. N., & Hau, L. N. (2010). Service personal values and customer loyalty: a study of banking services in a transitional economy. InternationalJournal of Bank Marketing, 28(6), 465–478. doi:10.1108/02652321011077706.

Toral, S. L., Martínez-Torres, R., Barrero, F., & Cortés, F. (2009). An empirical study of the driving forces behind online communities. InternetResearch, 19(4), 378–392. doi:10.1108/10662240910981353.

Tse, D. K., & Wilton, P. C. (1988). Models of con-sumer satisfaction formation: An extension. JMR,Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 204–212. doi:10.2307/3172652.

International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking, 4(4), 33-51, October-December 2012 51

Copyright © 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information Systems Research, 11(4), 342–365. doi:10.1287/isre.11.4.342.11872.

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. doi:10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926.

von Loewenfeld, F. (2006). Brand communities. Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler.

Wachter, R. M., Gupta, J. N. D., & Quaddus, M. A. (2000). IT takes a village: Virtual communities in support of education. InternationalJournalofInfor-mationManagement, 20(6), 473–489. doi:10.1016/S0268-4012(00)00039-6.

Walsh, G., & Beatty, S. E. (2007). Customer-based corporate reputation of a service firm: Scale devel-opment and validation. JournaloftheAcademyofMarketing Science, 35(1), 127–143. doi:10.1007/s11747-007-0015-7.

Whetten, D. A., & Godfrey, P. C. (1998). Identityinorganizations:Buildingstrategythroughconversa-tions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wiertz, C., & de Ruyter, K. (2007). Beyond the call of duty: Why customers contribute to firm-hosted com-mercial online communities. OrganizationStudies, 28(3), 347–376. doi:10.1177/0170840607076003.

Wirtz, J., & Bateson, J. E. G. (1999). Consumer satisfaction with services: Integrating the environ-ment perspective in services marketing into the traditional disconfirmation paradigm. Journal ofBusiness Research, 44(1), 55–66. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00178-1.

Wirtz, J., Mattila, A. S., & Tan, R. L. P. (2000). The moderating role of target- arousal on the impact of affect on satisfaction - An examination in the context of service experiences. JournalofRetailing, 76(3), 347–365. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00031-2.

Wixom, B. H., & Todd, P. A. (2005). A theoreti-cal integration of user satisfaction and technology acceptance. InformationSystemsResearch, 16(1), 85–102. doi:10.1287/isre.1050.0042.

Woisetschläger, D. M., Hartleb, V., & Blut, M. (2008). How to make brand communities work: Antecendents and consequences of consumer’s participation. JournalofRelationshipMarketing, 7(3), 237–256. doi:10.1080/15332660802409605.

Wold, H. (1985). Partial least squares. In S. Kotz, & N. L. Johnson (Eds.), Encyclopediaofstatisticalscience (pp. 581–591). New York, NY: Wiley.

Yang, S.-C., & Lin, C.-H. (2011). Factors affecting the intention to use Facebook to support problem-based learning among employees in a Taiwanese manufacturing company. AfricanJournalofBusinessManagement, 5(22), 9014–9022. doi: doi:10.5897/AJBM11.1191.

Yu, J., Ha, I., Choi, M., & Rho, J. (2005). Extending the TAM for a t-commerce. Information&Manage-ment, 42(7), 965–976. doi:10.1016/j.im.2004.11.001.

Yuksel, A., Yuksel, F., & Bilim, Y. (2010). Destina-tion attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. TourismManagement, 31(2), 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.tour-man.2009.03.007.

Zickuhr, K., & Smith, A. (2012). Digital differ-ences. Retrieved November 12, 2011, from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Digital_differences_041312.pdf