Disaster & development: Examining global issues and cases

Transcript of Disaster & development: Examining global issues and cases

1

Chapter 1Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

Naim Kapucu and Kuotsai Tom Liou

N. Kapucu, K. T. Liou (eds.), Disaster and Development, Environmental Hazards, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-04468-2_1, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014

N. Kapucu () · K. T. LiouUniversity of Central Florida (UCF), Orlando, FL, USAe-mail: [email protected]

1.1 Introduction

Disaster management and economic development have become two major public policies for many developed and developing countries in recent years. To achieve goals of economic development, policymakers and public managers have to de-sign different development policies and programs to seek opportunities for business formation and industry development and to address problems of economic cycles and recessions and consequences of the special financial crisis. While focusing on development goals, the leaders in these countries have to adjust their policies pri-orities and rearrange valuable resources to deal with occurrences and challenges of a variety of natural, man-made, and technological disasters, which are directly or indirectly related to economic development. For example, the four hurricanes that damaged portions of Florida in 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, the earthquake and resultant tsunami and nuclear power plant acci-dent that struck Japan in 2011, the China’s Sichuan earthquake in 2008 (Wenchuan) and again in 2013 (Ya’an) provide unfortunate reminders of the vulnerability of communities to natural disasters. These unfortunate events, like many others, illus-trate how disasters impact individuals and communities and affected social-techni-cal systems and economic functions and community lives.

While the impact of disasters on development has been recognized, the complex relationship between disaster and development has not been fully studied by schol-ars of disaster management and economic development. Disasters and their conse-quences may produce severe negative effects on economic and social development of communities and interrupt their planned development goals and policies. On the other hand, disaster management, especially disaster recovery, may also provide opportunities for policymakers and community leaders to reconsider their policy priorities and use valuable resources for the consideration of sustainable economic development. The relationship between disaster and development is a dynamic one

2 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

and its implications, positive or negative ones, depends on the unique social and cultural of local communities and the managerial capacity of their disaster and de-velopment.

This book is designed to study the dynamic relationship between disaster and development by examining important theoretical and policy issues and reviewing specific cases or examples in different countries. The introductory chapter first intro-duces major theoretical concerns in the literature of disaster and crisis management and economic development and then offers a conceptual framework to examine factors contributing to disaster recovery and sustainable economic development.

1.2 Conceptual and Theoretical Concerns

In the field of emergency and crisis management, too much emphasis is placed on response to disasters. Research on the economic impacts of disasters and disaster recovery is limited (Chang 1984; Kapucu and Ozerdem 2012; Miller and Rivera 2011; Phillips and Neal 2007). This is due to the fact that researchers and practi-tioners alike “in disaster and/or development must contend just not with varying disciplinary and political perspectives but also with the tension between academic endeavor and practitioner-led interests” (Fordham 2006, p. 341). In disaster and de-velopment, interdisciplinary and inter-agency boundaries are crossed and initiatives to introduce early forms of mitigation tend to be seen as a luxury not a necessity. To add to the problem, not only is the discipline vast but, as noted by Fordham (2006), early research on the subject was carried out due to an environmental divide creat-ing “dissimilarity in subject matter and literature between disaster researchers and development researchers” (p. 337).

Looking at disasters and development as a whole, one must consider the role es-sential development can play in managing disasters as they affect “society’s capac-ity—both in preparedness and recovery” (Tran et al. 2009, p. 404). Many factors can impede the process of integrating disasters and development. Rapid growth and poor re-development can create challenges and increase disaster risk in vulnerable communities. These issues create a need for a shift from perfecting response and recovery to looking at the benefits of disaster development in the early stages of mitigation and preparedness. Risk reduction and environmental management, in this sense, play a key role in developing policies that sustain communities (Collins 2009; Tran et al. 2009).

1.2.1 Disasters

With disasters on the rise and surmounting threats and impacts of climate change the urgent need presented is how to properly address the stresses and challenges di-sasters place upon a society. Sanker and Herath (2009) found that there is a relation-ship between a country’s level of vulnerability and how severely it is impacted by

31 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

an event, revealing the need for strengthening disaster risk reduction. The level of vulnerability is not only determined by the seismic and geological risks and threats in regions but can be exacerbated by the built environment of a community. To explain this Sanker and Herath state, “[i]t is quite evident that the disasters are not ‘natural’ but disasters are the final effect of the collision of ‘natural hazards’ with ‘vulnerabilities’ and ‘exposures’” (p. 139). With this information one can then visualize a picture of the built environment constantly under threat from various hazards, both natural and manmade. Thus, as Wisner (2003) puts it, disaster can be equated with failure of human development.

Risk reduction measures and practices are integral for improved disaster response and recovery and overall mitigation of vulnerabilities and risks. Underdeveloped communities increase their susceptibility to hazards and must consider implement-ing disaster reduction strategies that create “forward-looking policies pertaining to social development and equity, economic growth, justice and environmental quali-ty;” otherwise risks are heightened (Ahrens and Rudolph 2006, p. 208). On the other hand disasters present the opportunity to potentially alter human behavior. Thus, as emphasized earlier, vulnerability to hazards occurs not only as the result of geologi-cal conditions but also because of the actions of humans living within a particular environment (Lindell et al. 1997). In that sense, individuals’ and local governments’ assessment of own vulnerabilities is critical for reducing risk and “determining what mitigation practices can be implemented” (UNISDR 2012, p. 5). Understanding disasters as a two way process, “nonstructural” mitigation, which is the process of amending individual actions, can empower communities to understand the risks they accept regarding land use choices (Kendra and Wachtendorf 2006). These ac-tions will help to create a participatory environment in disaster and mitigation de-velopment once individuals are able to identify, in a new light, the risks within their community (Godschalk et al. 1999; Norris et al. 2008; Wisner et al. 2004).

1.2.2 Development

Development is defined by Blakely and Leigh (2010) as local economic develop-ment that “is achieved when a community’s standard of living can be preserved and increased through a process of human and physical development that is based on principles of equity and sustainability” (p. 75). Unlike disaster responses, develop-ment tends to be “forward-focused” (p. 335), reaching for the attainment of long term goals and set on advancing the economic and social environment (Fordham 2006). The relationship between disaster and development is important from the perspective of sustainable development.

The term sustainable development has been referred to as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future genera-tions to meet their own needs” (WCED 1987, p. 43). It has also been defined as “improving the quality of human life while living within the carrying capacity of supporting ecosystems” (IUCN/UNEP/WWF 1991, p. 211). The former definition

4 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

emphasizes equity issues between the present and future generations and the latter definition addresses the balance between economic development and environment protection. The interest in sustainable development has to do with concerns about negative consequences of environmental and equity problems of economic devel-opment. Disasters affect sustainable developments in both generation equity and environment protection because disaster outcomes produce negative effects on local natural and environmental conditions and disaster policies and program affect not only recovery efforts for the current generation, but also development opportunities for future generations. Sustainable development and related quality of life concerns have become major goals of development policies and programs for many local governments (e.g., Greenwood and Holt 2010).

1.2.3 Disaster and Development

Recognizing the importance of disaster and development, researchers have tried to examine key issues or topic about the relationship between disaster and develop-ment studies. For example, researchers of the United Nations International Strat-egy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) (Fordham 2006; Tran et al. 2009; UNISDR 2012) have identified three key variables of development in risk reduction and di-saster sustainability and stressed the importance of “disaster reduction, social and economic development, and sympathetic environmental management” (Fordham 2006, p. 340). Tran et al. (2009) stress “developmental management, environmental management and disaster risk management” (p. 409) as focus points for sustainable disaster management. In his review of disaster research between 1977 and 1997, Alexander (1997) highlights the same issue and concludes that analysis of disasters should be multi-disciplinary, sophisticated, and comprehensive in terms of study context. These authors all emphasize the importance of managing sustainable de-velopment with disaster recovery and management.

Unsustainable development strategies are key reasons for increased cost of di-sasters (FEMA 2000). Impact of climate change and global environmental chal-lenges necessitate a perspective that integrates disaster and development (Pelling 2003). A need for integrating perspective was also recognized by the United Nations Millennium Development Goals by placing sustainable development as critical for disaster risk reduction (UN 2013). To support the connection between disaster and development, researchers (e.g., Kasemir et al. 2003; Paterson 2006) also stress the importance of creating participatory and collaborative processes, allowing civil so-ciety to engage in and take responsibility in disaster risk management and sustain-able development. For example, Kasemir et al. (2003) promote the participation of citizens and other stakeholders for policy making in sustainable development. They suggest consultation procedures to integrate technical scientific modeling with democratic decision-making processes. Similar concerns are also highlighted by Paterson (2006) in regard to disaster policy.

In order to make progress in the development stages of disaster reduction, inter-disciplinary studies must occur to develop better risk reduction strategies and until

51 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

policies reflect this need, communities will potentially remain vulnerable and weak (Alabaster 2011; Collins 2009; Paterson 2006). It is important to create a participa-tory processes, allowing civil society to engage in and take responsibility in disaster risk management. This point is highlighted by Paterson (2006) in regard to disaster policy stating that eventually, “law’s contribution will be in terms of providing and guaranteeing the processes by which a wide range of actors (state, private sector, and civil society) interact in both the technical and policy aspects of disaster risk manage-ment” (p. 73). Participatory actions provide opportunities for a wide range of actors to interact and share knowledge. This process, it is hoped, will bring about connec-tions between environmental knowledge and risk reduction. An example used by Pa-terson (2006) to highlight this relationship is the need for experts to share earthquake predications in order to inform policy makers of the need to integrate risk reduction.

The holistic approach to integrating disaster with development has been empha-sized and practiced by policymakers and public managers of local communities. For example the city of Greensburg Kansas has incorporated multiple aspects into their Sustainable Comprehensive Plan. To complement future rebuilding twelve goals were created to address the “built environment, hazard mitigation, economic devel-opment, resource management, housing, transportation, infrastructure, parks and green corridors, and future land use” (Berkebile and Hardy 2010, p. 38). This effort reflects an opportunity presented in the pre-planning stages of disaster management to incorporate not only geological hazards but also social and economic features. The relationship between disaster and development will be further examined in the following section with explanation the integrated framework.

1.3 Integrated Disaster and Development Framework

The idea of integrating disaster and development to understand their relationship is relatively new. The interdependent (and blurred) relationship between disasters and development is extremely complex and requires new strategies to address both (Manyena 2012; UNISDR 2013; UNDP 2004; McEntire et al. 2002; Mileti 1999). Disaster recovery efforts should include sustainable development perspectives with an aim of vulnerability reduction (Bankoff et al. 2004; Berke et al. 1993; McEntire 2004; Stenchion 1997). Disaster and development concepts were not used together with the hazard perspectives before the 1970s. Vulnerability reduction perspective gained some influence in the field during 1980s and 1990s when vulnerability per-spectives and disaster development were used together (Manyena 2012). Similar to disaster vulnerability reduction perspectives, disaster resiliency perspectives that focus on sustainable development and disaster risk reduction have also been em-phasized in recent years i (Kapucu and Ozerdem 2012; Miller and Rivera 2011).

No one wants any disaster to occur in their communities. However, when they occur, disasters might create opportunity to improve community conditions, reduce risk, and create new economic and community development options (Skidmore and Toya 2002; Waugh and Smith 2006). Webb et al. (2002), in their extensive re-

6 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

search on business recovery were unable to find a significant relationship between disasters and long-term recovery. However, they were able to identify a relationship between disasters and short-term recovery and immediate post impact. They also found that the type of business significantly impacts the long-term recovery. The ability of quick adaptation for small business and nonprofit organizations is critical for sustainable economic and community recovery (Boin et al. 2010; Bruneau et al. 2003). Other positive and negative influences included in the study were: age of the business (negative), duration of closure (negative), financial condition of the business (negative), primary market, and business climate (positive). Post-disaster research mostly shows that small businesses and nonprofits are not able to recover, compete, or survive after disasters (Alesch et al. 2001; Ingram et al. 2006; Simo and Bies 2007) since they need assistance from government for long-term recovery.

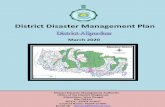

As depicted in Fig. 1.1, we propose that community based partnerships, net-works, social capital with effective disaster risk reduction policies and strategies are important factors in supporting community disaster resiliency and sustainable community recovery. These factors will be briefly reviewed here and will be further examined in different chapters throughout the book. The success of the integrated model is based on such factors as effective disaster policies and governance, com-munity resilience, collaborative capacity, civic engagement and participation, the support of nonprofit and civil society organization.

Com

mun

ity R

esili

ency

Sust

aina

ble

Dis

aste

r Rec

over

y an

d D

evel

opm

ent

(Nat

ural

, soc

ial,

envi

ronm

ent,

econ

omic

, and

bui

lt en

viro

nmen

t)

Community andOrganizational

Capacity Building

Effe

ctiv

e D

isas

ter P

olic

ies &

Gov

erna

nce

Community-basedSolutions

Interagency andInter-organizational

Collaboration

CivicEngagement

Fig. 1.1 Integrated framework for disaster and development

71 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

1.3.1 Disaster Recovery and Sustainable Development

Disasters can be seen as a “window of opportunity” for development and well-planned development can certainly reduce impacts of disasters. However, disasters were not recognized as a potential for development and development agencies were not involved in disaster management (Cuny 1983). This has been the case for both domestic and international development. Literature suggests mixed results on the relationship between disasters and economic recovery and development. Natural di-sasters might have long term positive impact on human, social, and physical capitals as well as productivity (Chang 1984; Skidmore and Toya 2002; Waugh and Smith 2006). Laura Reese (2006) claims that many of the lessons of disaster response and recovery can be applied to economic recovery as well. Reese indicates important characteristics for an effective disaster recovery and redevelopment, which include commitment, cooperation, creativity, inclusivity, and flexibility (Reese 2006).

1.3.2 Policies and Governance for Hazards and Vulnerability Reduction and Resiliency

Vulnerability and hazards over the past few decades have increased due to poor de-velopment practices and policies that lack sustainable outcomes and infrastructure. As a result counties and communities find themselves struggling in the recovery stage to provide both financial and physical resources after a disaster. Using for-ward thinking development practices implemented after disasters may provide the opportunity and resources needed to enhances sustainable community development, mitigation efforts and decrease future recovery costs (Birkland 1998; FEMA 2000).

Considering the aspect of human involvement and the role individuals play in hazard vulnerability. Kusenbach and Christmann (2013) define vulnerability in a way that incorporates these aspects. The important concept is that an individual’s perception of vulnerability is affected by the environment they are in, their ideals and the concerns of others that make up their community provided that individuals do have a choice regarding the level of exposure they choose to live within. When this is considered light is shed on a potential aspect of vulnerability which can then be used to hinder or promote development practices (which include mitigation and the use of vulnerability assessment factors).

A crisis such as a major disaster can become the opportunity for community wide sustainable development. One attainable feature of sustainable development is creating resiliency in the face of catastrophic events (FEMA 2000). It is known that the effects of disasters are linked to poverty and previous degradation of natu-ral land (Alexander 1997). These concepts when considered together highlight the need to create resiliency before a disaster as a way of reducing community vulner-abilities and subsequently, recovery costs after a disaster. There is a dire need for the creation and implementation of structured policies in response to or as mitigative efforts to disasters which regard the physical and natural environment as well as

8 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

the economic environment. Such policies need to also withstand the pressures of politics at all levels of government.

Resiliency can be created by communities, individuals, and organizations through the execution of choice and action. May (2013) notes that there are many reasons that facilitate the participation and creation of policies in the wake of di-sasters that can lead to more resilient communities. He discusses two important concepts that can lead to the creation of participation in resiliency efforts. The first is enacting some form of mandate on state and local governments which focuses on the reduction of hazards; while the second is extending planning efforts to identify common recovery goals in partnerships with all levels of the community.

1.3.3 Collaborative Capacity for Development After Disasters

As more citizen service delivery moves to the private sector, it is clear that there is an increased need for collaboration across sectors as well as within organizations and a need for an improvement of current practices. Partnerships, even an unlikely unification of people or services, can enhance response and recovery operations after a disaster through the increase outreach creates. It is said that even the most unlikely partnerships can be of benefit when disaster strikes (Ansell and Gash 2008; Bryson et al. 2006; Gazley 2013; Gray 2007).

Disasters have no discretion or boundaries associated with their paths of destruc-tion. As a result many organizations, jurisdictions, and agencies need to be involved in addressing the impacts. Looking more closely at the local level the resources within a community can belong to and benefit multiple sectors. Consider the in-frastructure that may be damaged, and may be public or privately owned and can benefit the whole community or just a few. Thus, the level of participation needed to effectively recover from a disaster must be considered.

Reese (2006) highlights these concerns and the many different players involved in recovering from the East Grand Forks floods. The processes and policies created and followed by this town proved to be efficient and long lasting. The fact that sin-gle fund sources were only a small piece to a larger recovery picture illustrating the critical role each organization had in working together as well as towards common goals. In this case partnerships were needed to reach the citizens were imperative to fostering trust in the process (Reese 2006). Partnerships with private companies, faith based organization, community associations, and even schools and local sports organizations extend the reach of local governments creating collaborative capac-ity while providing a connection to those citizens who may have otherwise been missed.

91 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

1.3.4 Civic Engagement and Participation in Recovery and Development

In a study to determine if citizen’s evaluation of the processes of civic participation and engagement were perceived as a positive endeavor in recovery efforts, Kweit and Kweit (2004) highlighted the long term success perceived in citizen participa-tion. They examined the recovery efforts of two cities affected in a flood. One used civic participation fully in recovery efforts and the other relied mostly on the guid-ance of elected officials with some community meetings and discussion forums. Results showed that civic participation was linked to the overall level of trust found within each community. Trust is a critical factor government officials should invest their time and resources in developing prior to a disaster as it enhances recovery processes and creates resiliency. It is in these times that both officials and citi-zens are vulnerable to making wrong decisions that affect not only themselves but the community as a whole. In some communities members have little control over events that lead to a disaster, but civic participation helps citizens visualize and cre-ate the outcomes of disaster recovery which in turn strengthens the social fabric of a community.

It has been found in previous research as well as the aforementioned study that citizen participation provides improved long term recovery efforts (Kweit and Kweit 2004). Considering the creation of policies in the wake of a disaster, it is identified that engaging citizens in this process promotes the success of policies in two ways. These include the acceptance level citizens have towards the policy as well as participation in shaping the policy which will be unique to their community.

1.3.5 The Support of Nonprofit and Civil Society Organizations for Community Based-Solutions

The nonprofit sector has become highly developed and more active in disaster man-agement in more recent times. This was not a direct strategy of the nation but rather the emergence of a response to specific disasters and cultural changes over the past decades (Eikenberry et al. 2007; Ott and Dicke 2012). This emergence has provid-ed a foundation for nonprofit organizations to succeed in the collaborative efforts needed in response to disasters. Kapucu (2007) states that nonprofit organizations can assist in “local, state and national problems through negotiated efforts or part-nerships” (p. 552). This idea can also be extended to the processes of international relief.

Foundations established in communities may also play a unique role in disaster recovery. Reese (2006) notes that foundations can provide resources to programs and efforts that are not able to be funded through the government or other nonprofit organizations. This is due to the fact that foundations are semi-private organizations and tend to have less bureaucracy in place and more discretion over spending in oc-casions of rare instances such as a disaster.

10 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

Until recently international aid came mostly in response to disasters and their effects on societies. There are multiple reasons for focus from international relief to center around processes of response and recovery; these include the policies of particular countries and the desires of donors as funding is more expansive when compared to that of preparedness and mitigation (Alexander 1997). In the early 90s international relief organizations started to recognize the link between disasters and underdeveloped communities or what we can refer to as unsustainable develop-ment. The turnaround in thinking lead to consideration of the importance of mitiga-tion activities and implementation prior to disasters (Berke 1995).

Community based solutions in the field of emergency management are needed to fully integrate mitigation and preparedness techniques into the creation of develop-ment policies. Edwards (2013) contributes this practice to the environment individu-als find themselves within, specifically the built environment, the geographic loca-tion and the ‘natural systems’ of the community. It is in this sense that citizens be-come vulnerable, due to both individual choices and decision made to protect which actually end of creating additional hazards. The example highlighted by Edwards (2013) is the levee breech of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina as well as dam failures and seawall hazard displacement. Not only does the environment create a need for community based solutions but social demographics in communities may also create unique situations during and after a disaster. Utilizing an approach to address these issues require the mobilization of resources of the entire community.

Edwards (2013) looks at community based solutions as bottom up approaches to managing disaster. She identifies the community actors or organizations as so-cial capital and the benefits in taking stock of them regarding what is unique and a potential benefit to citizens in the event of a disaster. The benefit of social capital and mobilization of additional resources is important because officials can increase community resources by including these organizations in preparedness and plan-ning efforts. Community-based approaches in turn assist in the success of long term recovery efforts such as displacement issues including those of the special needs population, job placement, medical care, etc. It is not only organizations but also individuals that drive recovery efforts after a disaster. Edwards (2013) notes that during the recovery efforts of Hurricane Katrina there were two unique situations where individuals played a leadership role; one situation where an individual was responsible for the re-opening of a community clinic and one incident where an individual single-handedly reopened a local school system.

1.3.6 Capacity Building for Sustainable Development after Disasters

The capacity of an organization or community to respond to and recover from a disaster can be linked to the concept of disaster and development including the concepts of resiliency, policy creation, and governance. Berkes (2007) illustrates this point through defining resiliency as a community concept in which response to a disaster includes adaption and absorption of the impact. Being able to absorb

111 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

and adapt to the impact of a disaster would mean that a community has the capacity to deal with the event and is resilient. Capacity building takes this concept a step further and integrates preventative and mitigation efforts through the use of effec-tive and feasible disaster development policies (The National Academies 2012). The capacity building perspective requires the creation of a culture of preparedness at individual, family, community, government, and private and nonprofit sector or-ganizations. Capacity building is directly linked to the improvement of managing disasters in ways that development in not compromised.

Capacity building can also be present in the form of institutional memory. After a disaster strikes individuals within an organization that have had experience have a rare opportunity to capture the interest of their peers and share knowledge thus stimulating ideas and increasing the capacity to adapt. Institutional memory is also a factor in self-organization which can be critical in long term recovery efforts and the formation of an adaptive structure within the community (Berkes 2007).

Capacity building in the form of accumulating human resource capacity and other resources creates a better understanding of the situation when disaster man-agement is considered due to the inter-agency and inter-organizational nature of disaster response and recovery (Kapucu et al. 2013; Manyena 2012). The role of these partners is highlighted through the use of their expertise in pre and post disas-ter efforts. In the aftermath of a disaster situation it is important for officials to come together to fully recognize and anticipate the needs of the community and identify areas where capacity needs to be developed.

1.4 Conclusion

Integrating disaster and development into a framework is valuable in theory and practice and the understanding of the integrated framework will be useful for both scholars and practitioners. Disasters have the ability to both encourage new op-portunities for growth or interrupt current or focused development projects. As a result disasters can be either an opportunity for a community or a loss of previous hard work. It is for these reason that disaster and development must be considered together when creating and/or maintaining policies and development procedures concerning local disasters. In this sense disasters may provide an opportunity to reduce community vulnerability, as well as, decrease disruption to future develop-ment through increased preparedness and mitigative efforts.

Sustainable development is a process that can be centrally planned or can be the result of local disaster recovery efforts. This is because disasters often pres-ent a unique opportunity for communities to not only rebuild but also improve the functions and infrastructure of their community. The only way to fully manage these large scale recovery efforts is with the integration of multiple organizations, and multiple levels of the government, nonprofit sector and even private entities alongside the inclusion of citizens. Civic participation in recovery efforts and policy building as a form of mitigation efforts increases trust, and as a result resiliency in

12 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

the face of disasters. The multi-level approach required for disaster development relies not only on the decisions of the multiple organizations involved but also the choices and actions of citizens.

The four phases of disaster management each provide opportunities for develop-ment. In the preparedness cycle, the need for civic participation in early phases of development will encourage trust between the government and assisting organiza-tions, and to the multiple citizens it is capable of reaching. During the mitigation cycle, the buy-in created in preparedness activities helps to discover and enhance the needs for action within each community, in turn creating a certain level of com-munity backing for mitigation efforts. In the response phase it is important to call on those unique organizations that reach citizens that average government agencies may not have access to. This enhances information exchange and transparency in critical times of disasters. It is found that in the recovery phase these processes then lead to individual self-organization as well as future participation and acceptance of planning and recovery efforts and overall development of sustainable policies. It is also important to monitor success of policies and governance tools in building resil-ient and sustainable communities. Focusing on different elements of the framework, the chapters in this book provide additional studies to examine theoretical issues and disaster cases among developed and developing countries and communities about the experience and lessons of integrating disaster and development.

References

Ahrens, J., & Rudolph, P. M. (2006). The importance of governance in risk reduction and disaster management. Journal of Contingencies & Crisis Management, 14(4), 207–220.

Alabaster, O. (2011) Earthquake response plan vital: U.N. disaster risk expert. The Daily Star, October 24. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Local-News/2011/Oct-24/152026-earthquake-response-plan-vital-un-disaster-risk-expert.ashx#ixzz1s K7h10Mg. Accessed 17 April 2012.

Alesch, D. J., Holly, J. N., Mittler, E., & Nagy, R. (2001). Organizations at risk: What happens when small businesses and not-for-profits encounter natural disasters. Fairfax: Public Entity Risk Institute.

Alexander, D. (1997). Study of natural disasters, 1977–1997: Some reflections on a changing field of knowledge. Disasters, 21(4), 284–304.

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571.

Bankoff, G., Frerks, G., & Hilhorst, D. (Eds.). (2004). Mapping vulnerability: Disasters, develop-ment, and people. London: Earthscan.

Berke, P. R. (1995). Natural hazard reduction and sustainable development: A global assessment. Journal of Planning Literature, 9(4), 370–382.

Berke, P. R., Kartez, J., & Wenger, D. (1993). Recovery after disaster: Achieving sustainable de-velopment. Disasters, 17(2), 93–108.

Berkes, F. (2007). Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: Lessons from resilience thinking. Natural Hazards, 41(2), 283–295.

Berkebile, R., & Hardy, S. (2010). Moving beyond recovery: Sustainability in rural America. Na-tional Civic Review, 99(3), 36–40.

Birkland, T. A. (1998). Focusing events, mobilization, and agenda setting. Journal of Public Pol-icy, 18(1), 53–74.

131 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

Blakely, E. J., & Leigh, N. G. (2010). Planning local economic development: Theory and practice (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Boin, A., Comfort, L. C., & Demchak, C. C. (2010). The rise of resilience. In L. C. Comfort, A. Boin, C., & C. Demchak (Eds.), Designing resilience: Preparing for extreme events (1–12). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bruneau, M., Chang, S., Eguichi, R. T., Lee, G. C., O’Rourke, T. D., Reinhorn, A. M., & von Win-terfeldt, D. (2003). A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthquake Spectra, 19(4), 733–752. doi:10.1193/1.1623497.

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of cross-sec-tor collaborations: Propositions from literature. Public Administration Review, 66(S1), 44–55 (Special Issue).

Chang, S. (1984). Do disaster areas benefit from disasters? Growth and Change, 15(4), 24–31.Collins, A. E. (2009). Disaster and development. London: Routledge.Cuny, F. C. (1983). Disasters and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Edwards, F. (2013). All hazards, whole community, creating resiliency. In N. Kapucu, C. Hawkins,

& F. Rivera (Eds.), Disaster resiliency: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 21–47). New York: Routledge.

Eikenberry, A. M., Arroyave, V., & Cooper, T. (2007). Administrative failure and the international NGO response to hurricane Katrina. Special Issue. Public Administration Review, 67, 160–170.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2000). Planning for a sustainable future: The link between hazard mitigation and livability. http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=1541. Accessed 10 Aug 2012.

Fordham, M. (2006). Disaster and development research and practice: A necessary eclecticism? In H. Rodriguez, E. L. Quarantelli, & R. R. Dynes (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research. New York: Springer.

Gazley, B. (2013). Building collaborative capacity for collaborative capacity. In N. Kapucu, C. Hawkins, & F. Rivera (Eds.), Disaster resiliency: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 84–98). New York: Routledge.

Godschalk, D. R., Beatley, T., Berke, P., Brower, D. J., & Kaiser, E. J. (1999). Natural hazard mitigation: Recasting disaster policy and planning. Washington D.C: Island Press.

Gray, B. (2007). The process of partnership construction: Anticipating obstacles and enhancing the likelihood of successful partnerships for sustainable development. In P. Glasbergen, F. Biermann, & A. P. J. Mol (Eds.), Partnerships, governance and sustainable development: Re-flections on theory and practice (pp. 29–48). Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Greenwood, D. T., & Holt, R. P. F. (2010). Local economic development in the 21st century: Qual-ity of life and sustainability. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

Ingram, J. C., Franco, G., Rumbaitis-del Rio, C., & Khazai, B. (2006). Post-disaster recovery dilemmas: Challenges in balancing short-term and long-term needs for vulnerability reduction. Environmental Science and Policy, 9(7–8), 607–613.

IUCN/UNEP/WWF. (1991). Caring for the earth: A strategy for sustainable living. Gland, Switzerland.

Kapucu, N. (2007). Non-profit response to catastrophic disasters. Disaster Prevention and Man-agement, 16(4), 551–561.

Kapucu, N., & Ozerdem, A. (2012). Managing emergencies and crises. Boston: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Kapucu, N., Hawkins, C., & Rivera, F. (Eds.). (2013). Disaster resiliency: Interdisciplinary per-spectives. New York: Routledge.

Kasemir, B., Jager, J., Jaeger, C. C., & Gardner, M. T. (2003). Public participation in sustain-ability science: A handbook. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kendra, J., & Wachtendorf, T. (2006). Community innovations and disasters. In H. Rodriguez, E. L. Quarantelli, & R. R. Dynes (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research (pp. 316–334). New York: Springer.

14 N. Kapucu and K. T. Liou

Kusenbach, M., & Christmann, G. (2013). Understanding hurricane vulnerability: Lessons from mobile home communities. In N. Kapucu, C. Hawkins, & F. Rivera (Eds.), Disaster resiliency: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 61–83). New York: Routledge.

Kweit, M. G., & Kweit, R. W. (2004). Citizen participation and citizen evaluation in disaster re-covery. American Review of Public Administration, 34(4), 354–373.

Lindell, M. K., Alesch, D., Bolton, P. A., Greene, M. R., Larson, L. A., Lopes, R., May, P. J., Mulilis, J.-P., Nathe, S., Nigg, J. M., Palm, R., Pate, P., Perry, R. W., Pine, J., Tubbesing, S. K., & Whitney, D. J. (1997). Adoption and implantation of hazard adjustments. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 15, 327–453 (Special Issue).

Manyena S. B. (2012). Disaster and development paradigms: Too close for comfort? Development Policy Review, 30(3), 327–345.

May, P. (2013). Public risk and disaster resilience: Rethinking public and private sector roles. In N. Kapucu, C. Hawkins, & F. Rivera (Eds.), Disaster resiliency: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 126–145). New York: Routledge.

McEntire, D. A. (2004). Development, disasters and vulnerability: A discussion of divergent theo-ries and the need for their integration. Disaster Prevention and Management, 13(3), 193–198.

McEntire, D. A., Fuller, C., Johnston, C. W., & Weber, R. (2002). A comparison of disaster para-digms: The search for a holistic policy guide. Public Administration Review, 62(3), 267–281.

Mileti, D. S. (1999). Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States. Washington, D.C: Joseph Henry Press.

Miller, D. M. S., & Rivera, J. D. (Eds.). (2011). Community disaster recovery and resiliency: Ex-ploring global opportunities and challenges. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Commu-nity resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities and strategy for disaster readiness. Amer-ican Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6.

Ott, J., & Dicke, L. (2012). The nature of the nonprofit sector. Boulder: Westview Press.Paterson, J. (2006). A note on georisk, sustainable development and law. AIP Conference Proceed-

ings, 825(1), 67–78.Pelling, M. (Ed.). (2003). Natural disasters and development in a globalizing world. New York:

Routledge.Phillips, B. D., & Neal, M. D. (2007). Recovery. In W. L. Waugh, Jr. & K. Tierney (Eds.), Emer-

gency management: Principles and practice for local government (2nd ed., pp. 207–233). Washington DC: ICMA.

Reese, L. A. (2006). Economic versus natural disasters: If detroit had a hurricane …. Economic Development Quarterly, 20(3), 219–231.

Sanker, S. & Herath, G. (2009). Macroeconomic management and sustainable development. In R. Shaw & R. R. Krishnamurthy (Eds.), Disaster management: Global challenges and local solu-tions (pp. 135–149). Hyderabad: Universities Press.

Shreib, K., Norris, F. H., & Galea, S. (2010). Measuring capacities for community resilience. So-cial Indicators Research, 99(2), 227–247. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9576-9.

Simo, G., & Bies, A. (2007). The role of nonprofits in disaster response: An expanded model of cross-sector collaboration. Public Administration Review, 67(S1), 125–142.

Skidmore, M., & Toya, H. (2002). Do natural disasters promote long-run growth? Economic In-quiry, 40, 664–687.

Stenchion, P. (1997). Development and disaster management. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 12(3), 40–44.

The National Academies. (2012). Disaster resilience: A national imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Tran, P., Sonak, S., & Shaw, R. (2009). Disaster, environment and development: Opportunities for integration in Asia-Pacific region. In R. Shaw & R. R. Krishnamurthy (Eds.), Disaster manage-ment: Global challenges and local solutions (pp. 400–423). Hyderabad: Universities Press.

United Nations (UN). (2013). The millennium development goals report. New York: UN.United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2004). Reducing disaster risk: A challenge

for development-a global report. New York: United Nations.

151 Disasters and Development: Investigating an Integrated Framework

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). (2005). International day for disaster reduction, United Nation. http://www.unisdr.org/2005/campaign/2005-iddr.htm. Accessed 15 Feb 2012.

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). (2012). Towards a post-2015 framework for disaster risk reduction. http://www.unisdr.org/files/25129_posthfaconsul-tationpaperfinal30.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2012.

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). (2013). Synthesis report consultations on a post-2015 framework on disaster risk reduction. Geneva, UN.

Waugh, W. L. Jr., & Smith, B. R. (2006). Economic development and reconstruction on the Gulf after Katrina. Economic Development Quarterly, 20(3):211–218.

Webb, G. R., Tierney, K. J., & Dahlhamer, J. M. (2002). Predicting long-term recovery from di-sasters: A comparison of the Loma Prieta earthquake and hurricane Andrew. Environmental Hazards, 4(1), 45–58.

Wisner, B. (2003). Changes in capitalism and global shifts in the distribution of hazard and vulner-ability. In M. Pelling (Ed.), Natural disasters and development in a globalizing world (pp. 43–56). New York: Routledge.

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2004). At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulner-ability and disasters (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.