Diffusion of voluntary protection among family forest owners: Decision process and success factors

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Diffusion of voluntary protection among family forest owners: Decision process and success factors

Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Forest Policy and Economics

j ourna l homepage: www.e lsev ie r .com/ locate / fo rpo l

Diffusion of voluntary protection among family forest owners: Decision process andsuccess factors

Katri Korhonen a,⁎, Teppo Hujala b, Mikko Kurttila c

a University of Eastern Finland, School of Forest Sciences, Joensuu, Finlandb Finnish Forest Research Institute, Vantaa, Finlandc Finnish Forest Research Institute, Joensuu, Finland

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +358 40 7622 983; faxE-mail address: [email protected] (K. Korhon

1389-9341/$ – see front matter © 2012 Elsevier B.V. Allhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2012.08.010

a b s t r a c t

a r t i c l e i n f oArticle history:Received 25 January 2012Received in revised form 27 June 2012Accepted 30 August 2012Available online 26 September 2012

Keywords:Biodiversity conservationCommunication channelsDiffusion of innovationInnovation–decision processPolicy implementation

The ongoing forest biodiversity protection programme in Finland (METSO) relies on voluntary participationof family forest owners. Even though the programme has gained wide acceptability among owners, comparedto traditional conservation such as land acquisition, more owners need to be engaged. In this study, we ex-amined how the new protection measures have diffused among forest owners. This analysis will help findmeans to promote the protection among owners who could but have not yet participated. The theoreticalbackground is innovation diffusion. We focused on the communication channels and attributes of innovationthat would be important for the rest of the adopters. Data were gathered from owners who have protectedtheir forests in the eastern part of Finland. The results showed that the idea of protection has reached forestowners mainly via certain advisors of a regional Forestry Centre or via forestry magazines and newspapers. Inthe future, it is important that the advisors of local Forest Management Associations and employees of timberbuying companies promote the programme more, since they are the most familiar forestry experts for manyowners. In addition, it would be necessary to increase the role of peer forest owners and enhance the visibil-ity of protected areas. Highlighting the rationality and ease of protection to potential adopters is important.

© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Major changes in forestry's internal and external operational envi-ronments imply that forestry needs innovations that emphasise the ef-ficient and diversified use of forest resources (cf. Rametsteiner andWeiss, 2006; Weiss et al., 2011). New practices may emerge at thegrass root level as small enhancements to existing practices (cf. Chenget al., 2011) or they can be disseminated into practice via traditionalpolicy-driven top-down processes (Cubbage et al., 2007). In these poli-cy intervention chains, new practices flow from the upper policy levelthrough various institutions and individuals to the grass root, i.e., theforest owner level (Mickwitz, 2006). Particularly in countries wherenon-industrial family forest ownership plays an important role, theowners' motives and readiness (or not) to adopt new forest-relatedpractices need to be considered.

The worldwide agreements to halt the decline in biodiversity haveaffected national forest policies and resulted in, for example, the de-velopment of new conservation programmes (e.g., Kauneckis andYork, 2009; Ma et al., 2012). New environmental policy instrumentsemphasise economic values, a market-driven approach and voluntaryparticipation of forest owners (Brown, 2002; Mayer and Tikka, 2006).Voluntary practices and incentives for forest owners have gained

: +358 29 532 3113.en).

rights reserved.

wide acceptability and they are more successful than authoritativenature conservation because they appreciate forest owners' variousperspectives and property rights (Horne et al., 2009). Voluntary forestprotection is not a new thing as different practices have been appliedin several countries from as early as the 19th century (Frank andMüller, 2003). However, the practices and definitions of voluntaryprotection vary among different countries (Mayer and Tikka, 2006;Kauneckis and York, 2009).

In Finland, besides the statutory means of biodiversity protection,voluntary protection instruments for family forest owners have beendeveloped. This development can be seen as the diffusion of a newpolicy that is realised as a new practice (Paloniemi and Varho, 2009;Mäntymaa et al., 2009). A programme that can be considered as a pol-icy innovation is the ongoing Forest Biodiversity Programme forSouthern Finland, widely known as the METSO programme (FinnishGovernment, 2008). In the METSO programme, forest owners canoffer ecologically valuable areas from their forest for protection. Thetrial period of the METSO programme was implemented during theyears 2003 to 2007. The aim of the trial phase was to develop aprocedure that highlighted new ways of protection, such as volun-tary, owner-orientated participation, the possibility of temporaryagreements and compensation claims from forest owners (FinnishGovernment, 2008; Mäntymaa et al., 2009). From the beginning ofthe year 2008, the instruments have been fine-tuned, so that ownerswith their forests located inside the METSO programme area have

83K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

been able to make permanent or fixed-term protection agreements ifthe forests they offer fulfil the selection criteria (Finnish Government,2008). The programme will continue until at least the end of 2016.

The compensation that owners receive in the METSO programmeis based on the value of growing stock and the market price of timber.The programme is funded by annual budget allocations and accordingto a recent study, the compensations for owners cover the losses ofnot selling timber (Suihkonen et al., 2011). Compared to the volun-tary protection implemented in other countries, the compensationin the METSO programme is high (Kauneckis and York, 2009). There-fore, the programme could even be defined as a compensation-drivenone, since the rather good monetary compensation can also be con-sidered as a new way to earn income from the forest.

The overall objective of this study was to examine how the newvoluntary biodiversity protection policy instruments have diffusedto the “grass root” level, i.e., among forest owners, by analysing theactualised protection processes. The study aimed to dig deeper intothe stages of forest owners' decision processes towards making vol-untary biodiversity protection agreements. By applying the theorydescribed below and the concepts of innovation diffusion and empir-ical data to the perceptions of owners, the key information sourcesand accelerators of protection decisions were identified. The more de-tailed study questions were:

(1) How were voluntary protection processes initiated and whichcommunication channels were most actively utilised at the dif-ferent stages of innovation decision processes? In the discussionsection, we evaluate which communication channels should beimproved.

(2) Which characteristics of the voluntary protection innovationhave been important for different innovation adopter catego-ries? Following these results, we discuss which characteristicsshould be promoted to diffuse the innovation of voluntary pro-tection among late adopters.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Innovation decision process

Innovation can be defined as a practice, which is perceived as newamong individuals (Schumpeter, 1934; Rogers, 2003; Oslo Manual,2005 p. 46). Innovation diffuses to the social system through certainchannels over time. During the diffusion process, uncertainty aboutthe innovation is reduced and over time, the diffusion can lead to asocial change or to institutional renewal (Rogers, 2003; Åkerman etal., 2010). However, adoption of a new practice demands a take-offfrom equilibrium to a new level of activity, and a fear of changes com-plicates the diffusion.

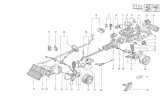

The innovation decision process is the cycle that any potentialadopter experiences while deciding whether to adopt the innovation.The process can be divided into five different stages (Fig. 1) (Rogers,2003). In the knowledge stage, an individual becomes aware of the ex-istence of an innovation and makes the first impression. Typically,one of the most important channels to deliver information at thisstage is mass media, which reaches a large number of forest owners

Fig. 1. The innovation decision process and the most importan

effectively and quickly (Rogers, 2003; Hannerz et al., 2010). The mes-sages from mass media can lead to changes and adoption of the inno-vation if the innovation is compatible with the values of an individual(Rogers, 2003 p. 194).

In the persuasion stage, an individual forms a preferential or oppos-ing attitude towards the innovation by evaluating pros, cons and theconsequences of the possible adoption of innovation (Rasamoelina,2008). Personal contacts and discussions with peers are important,since these contacts even change individual's opinion (Rogers, 2003).Hubbard and Sandmann (2007) suggested that the more forest ownersparticipate in the activities of different forest-related organisations orthe more contacts they have with acquaintances or extensionists, themore likely it is that theywill adopt the innovation. According to the in-novation diffusion theory, change agents are individuals who affect thedecision making of potential adopters and accelerate the adoption(Rogers, 2003). Typically, change agents are professionals from a com-pany or organisation that diffuses the innovation. In forestry, extensionworkers or agency personnel can be seen as change agents (Muth andHendee, 1980).

In the decision stage, the actions that lead to adoption or rejection ofthe innovation are made. Deployment of innovation happens in the im-plementation stage. Implementation in nature protection is actually, inmost cases, non-implementation; cutting or other silvicultural treat-ments are not executed. The possible actions that can happen in the im-plementation stage are, for example, marking of the protected area orrestoring operations in the forest. In the confirmation stage, an individu-al searches confirmation for the decision that has been made.

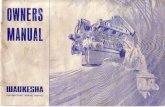

2.2. Innovation adopter categories and characteristics of innovation

The diffusion of innovation during a course of time can be describedwith a cumulative S-shaped curve (Fig. 2) (Rogers, 2003). The shape ofthe curve is based on communication between individuals in society.First, a great effort and resources are used to diffuse the innovation;however, only a few actually adopt the innovation. The diffusion accel-erates when those who have not yet adopted the innovation begin toimitate the adopters (Bass, 1969). Rogers (2003) classified people intofive different categories based on the time of adoption (Fig. 2). The ear-lier the person adopts an innovation, the more innovative s/he is. Inno-vativeness describes how receptive individuals are for new ideas andhow independently they make their decisions about adopting.

Innovators are the first ones to adopt the innovation (Fig. 2). Theyare described as venturesome risk takers and are the links that bringnew information from the global to the local level. For them, a messagethrough mass media is an adequate push to try something new. Earlyadopters are often respected people or even opinion leaders in theirlocal communities (Rogers, 2003; Crona and Bodin, 2010). They haveseveral contacts with locals and high influence on others. Their “task”in innovation diffusion is to decrease the uncertainty about the innova-tion and act as role models for the rest of the adopters.

Most people belong to the early or late majority. The importanceof persuasion or even pressure from peers, as well as the time usedfor decision making, increases when proceeding to the later adoptercategories. According to Moore (2002), the best reference for the

t accelerators (partly adopted from Rogers, 2003 p.170).

Fig. 2. Diffusion of innovation and adopter categories, adopted from Rogers (2003). Thegrey S-curve represents the cumulative number of adopters within a population, whilethe black curve represents the number of new adopters at each point of time. The lay-out of the figure is adopted from Wikipedia commons under a public domain licence;for this version, chasm (Moore, 2002) was added by the present authors.

84 K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

early majority is spoken experience from another member of theearly majority. The lack of references from the same group mayeven cause a chasm between early adopters and the early majority,preventing the diffusion (Fig. 2). The chasm exists because differentadopters have different expectations. The early majority ask for prac-tical benefits and easy-to-use services, therefore, the innovation can-not be presented to them in the same way as for the early adopters,who seek fresh solutions. The late majority and laggards, who arethe last ones to adopt the innovation, are even more sceptical thanthe early majority. An innovation must be convincing and bring eco-nomic benefits, while the common norms must favour innovation be-fore they are willing to adopt it.

Studies about innovation diffusion related to the use of naturalresources have concentrated particularly on farmers (cf. Clearfield andOsgood, 1986; Sheaffer, 2000). Among forest owners, the studies haveclassified owners into regenerators and non-regenerators (Palmer etal., 1985; Doolittle and Straka, 1987; Sheaffer, 2000). In addition,Rasamoelina (2008) applied an innovation diffusion process whenstudying the factors affecting the adoption of sustainable forest prac-tices among forest owners. Even though the theory of chasmhasmainlybeen used when adopting high-tech products, it has also beenrecognised in the field of forest policy (Rametsteiner andWeiss, 2006).

Innovations have certain characteristics that affect their adoptionand especially the speed of adoption. It is believed that compatibility,relative advantage, trialability and observability have positive effects,while complexity has a negative one on diffusion (Rogers, 2003). Inthe case of biodiversity protection, the most important characteristicseems to be compatibility with values, culture, beliefs and needs(Fritz-Vietta et al., 2011). Nature protection is an issue that typicallyevokes strong feelings and might raise conflicts due to competinguses of land. The most likely protection adopters are owners whosevalues and forest management motivations are positive towards bio-diversity protection (Horne, 2006). Relative advantage describes howbeneficial the innovation is compared to earlier solutions and other for-est uses. Benefits are typically monetary. In the case of the METSOprogramme, owners receive compensation and according to earlierstudies, compensation is highly important for owners (Horne, 2006).

If the innovation can be understood and implemented easily, itscomplexity is low. Trialability, in turn, describeswhether the innovationcan be experimentedwith. According to Rogers (2003), trialability is es-pecially important for early adopters due to the lack of peer experience.In the case of fixed-term voluntary nature protection, trialability allures

owners for protection (Horne, 2006). Observability describes how easyit is to perceive the innovation or communicate with others about theinnovation.

3. Materials and methods

Data were gathered from forest owners who had voluntarilyprotected part of their forest holding in the METSO programme in2009. The holdings were located in North Karelia, Eastern Finland,which does not drastically differ from other regions in terms of forestowner andholding characteristics (Hänninen et al., 2011 p. 89–94). Thereare approximately 22,000 forest holdings in the region (Leppänen andSevola, 2012), and in 2009, the share of holdings participating theMETSO programme was approximately one percent. In the study, therewere two types of protection agreements. The permanent protectionagreementsweremadewith the Regional Environment Centre, presentlyknown as the Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Envi-ronment (later referred to as ELY). Out of the 20 ownerswho hadmade apermanent agreementwith ELY in North Karelia, 19 agreed to participatein the interview. Fixed-term agreements (10 years) were made with theForestry Centre (FC). In 2009 about 160 owners had made fixed-termagreement inNorthKarelia. Only 40 of themwere asked for the interviewsince they had made the kind of agreement where protected areas wereenlargements around areas determined in forest laws. It is voluntary tomake an enlargement, however, it depends also on the characteristicsof the forest whether the enlargement is ecologically meaningful. 25 of40 owners agreed to participate in the interview. Owners wereinterviewed by phone. Interviews lasted from 20 min to 1 h. Callswere taped and transcribed. In addition, three ELY and five FC offi-cials, who had negotiated the agreements with the forest owners,were interviewed.

The interviews were semi-structured accompanied by a structuredpart. Discussion themes of the semi-structured part consisted offive dif-ferent themes. Themes considered motivation for protection, progressof the protection process and owners' satisfaction with the compensa-tion and with the protection process. Owners' social network duringthe protection process was inquired both in the semi-structured aswell as in the structured part. The structured question pattern aboutthe forest owners' social networks considered the relationships thatowners had with 11 predefined or other individuals and organisationsduring the protection process. Questions included the existence of therelationship, contact occasions and direction of the contact. In addition,it was askedwhether the person was familiar to owner, how they com-municated (e.g. meeting, phone, email) and about what issues theydiscussed. Furthermore, background information about the forestowners, their forest holdings and the protected areas were requested.

The analysis of the semi-structured part was qualitative with a dis-course analytical approach (David and Sutton, 2004; Creswell, 2009 p.185). After transcribing the interviews, the texts were carefully readthrough to get an overview. The detailed analysis continued theme bytheme. The interviews were processed several times to get more versa-tile information from every interview. The NVivo programme (Bazeley,2007)was used as a tool for coding, condensing and classifying the data.

The different stages of the decision making process were definedaccording to the innovation diffusion theory (Fig. 1). In this study, theknowledge stage considered the first idea, initiation or a contact thattriggered the forest owner to see the possibility of protection. The per-suasion stage considered all the contacts, both actively searching andpassively receiving, the forest owners had after the first initiative andbefore they made their decision to protect in the decision stage. Deci-sionwas realised in a protection agreement.Wemerged the implemen-tation and confirmation stages, since the owners did not have muchtime in between the agreement and the interview, and because it is typ-ical that these stages are not visible in biodiversity protection projects.After defining the stages, different communication channels and con-tents of the communication were determined in every stage. Both

85K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

qualitative and quantitative data were used to examine the channelsand connections.

In the second phase of the study, forest owners were divided intotwo groups based on the type of agreement (fixed-term or perma-nent), after which they were further divided into innovation adoptercategories. The division of innovation adoption types was based onthe theory of communication behaviour among adopter categories.According to the theory, the more innovative forest owners are, themore actively they seek information and the more cosmopolitanthey are (Rogers, 2003). Innovation adoption types were definedaccording to two criteria: (1) type of initiative and (2) type of chan-nels that the owners used for information gathering (Table 1). Bothcriteria were divided into three categories and every forest owner re-ceived a score from 1 to 3 in both criteria. The higher the scores theowners received, the more innovative they were interpreted to be.

According to Moore (2002), there is a distinct difference betweenearly adopters and the early majority. We aimed to find this chasm(see also Fig. 2) and divided our respondents into two groups: earlyand late adopters. The owners whose score sums were five or morewere classified into early adopters and those who received less thanfive were classified into late adopters. Late adopters comprised atleast the early and possibly the late majority, since it was assumedthat laggards were not yet among those who tended to make protec-tion contracts during 2009. It was also assumed that innovators hadalready protected their land in the METSO testing phase or during2008. Finally, we had four groups. The differences between thegroups in the attributes of innovation were studied qualitatively. Dif-ferences between the background characteristics in different ownercategories were assessed with cross-tabulation and comparison ofsample means. Non-parametric Mann–Whitney and Fisher's Exacttests were used to find statistically significant differences.

4. Results

4.1. Contacts and communication channels at different stages of thedecision process

4.1.1. Knowledge stageBefore the establishment of the METSO programme, even 10 years

ago, some owners had had discussions with the officials of FC or thelocal Forest Management Association (FMA) about the area that wasnow protected. These discussions took place when owners received in-formation about the fact that high quality key habitats, defined by theforest law, were found from their forest in nationwide inventories. At

Table 1Theory-driven classification criteria for determining owners' innovation adoptercategories.

Criterion (A) Initiative for protection Score

The owner is highly self-active. Owner has his/her own idea toprotect before a contact with a professional.

3

The owner has his/her ownwill and it is his/her decision to protect;however, a clue from the professional or acquaintance is needed.

2

Protection is strongly recommended for the owner and the ownerfeels partly obliged to protect.

1

Criterion (B) Channels used for information gathering Score

The owner is active in gathering information from differentorganisations. Owner may have professional experience fromthe field of forestry or environment.

3

Besides mass media, the owner has mainly regional informationnetworks. S/he has read or heard about the protectionexperiences of other forest owners.

2

The owner is not active in gathering information and has onlypersonal connections with forestry professionals andacquaintance.

1

that time, owners were only told that silvicultural operations thatwould change the characteristicswere prohibitedwithin these habitats.However, in most cases, compensations were not offered. Contrary tothese experiences, some owners have had their own goal, already foryears, to protect a certain area in their forests.

“… three years ago, we were there with the entire family. That's whenI threw the idea out there that this will never be felled and that'swhen the idea took off. So it was me who took the initiative … Thenthis METSO programme came about even more, so I called the Envi-ronmental administration…” (FO14, M52: interviewee ID 14, male,52 years)1

After the establishment of the METSO programme, the initiatives toprotect came primarily either from the forest owner or an FC official. Al-though the majority of the forest owners stated that it was strongly theirown will to protect the area, some kind of push was usually needed totake thefirst step to contact the officials (Fig. 3). For some owners, aware-ness about such a programme acquired from newspapers or forestrymagazines was an adequate push. In addition, several owners said thatthey found the information about who to contact from these magazines.

“My own idea, that I subscribed to some forestry magazine that I thenread and there was an article in it about this protection and the nameof the Lieksa [name of city] contact person and I contacted him …”

(FO24, F48)

Owners' own professional experience or education in the field of for-estry helped them become informed. In particular, several of the ownerswho entered fixed-term agreements were forestry professionals.

“… I myself worked in the forestry business for a long time, for thestate-owned Metsähallitus for thirty-three years and they had theseconservation areas established for Metsähallitus in those times andso the idea grew from that.” (FO20, M72)

A possibility to meet and discuss with a forestry advisor in differentevents, for instance in a forestry exhibition, also enabled the start of theprocesses. In addition to official events and networks, owners were ableto gather knowledge from unofficial networks such as hunting clubs.Only a few owners got their idea from other forest owners who hadmade protection agreements.

If the idea to protectwas the owner's own, thefirst “visible” stepwascontacting the forestry professionals. Some of the owners, since they al-ready knew the officials of FC or FMA, took at first contact to these orga-nisations. From the FC or FMA, some of themwere forwarded to the ELY.Besides forest owners' own initiative, especially in fixed-term agree-ments, the initiatives came from FC officials. The advisor of the FC typi-cally found the valuable area during a stand-wise inventory for forestplanning and suggested protection to the owner. Closer examination re-vealed that the FC had certain advisors who were more active thanothers in proposing protection to owners. Although the initiativecame from the advisor, owners admit that they had already been think-ing about saving the area from cuttings.

“… it must have been that, the Forestry Centre, advisors might theyhave been the ones to make the initiative, but I've always had thisidea at the back of my head that, erm, at least I didn't want to fellthem.” (FO35, M46)

4.1.2. Persuasion stageAfter the first idea or initiative, owners gathered information from

their social network and the media. Owners received information

1 The presented interview quotations have been translated from Finnish to Englishby a double-native speaker to maintain both the meaning and tone.

Fig. 3. Overview of factors at different stages of the protection agreement. The direction of the arrows describes the flow of information. Two-directional arrows describe conver-sational relationships that are typical in persuasion and decision stages.

Table 2The share of forest owners' contacts with different service providers and other network

86 K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

about different protection possibilities and discussed mainly with theforestry professionals with whom they finally made the agreement.Especially in fixed-term agreements with the FC, connections toother organisations were rare (Table 2). There were two cases inwhich an FMA advisor took care of the whole process on behalf ofthe forest owner. Only in a few cases, owners asked for offers fromboth the FC and ELY to compare the compensations of different agree-ment types. Owners also requested information or opinions from ac-quaintances they considered as experts or peers with knowledge.These people were typically relatives.

“… in another Forestry Centre I have a nephew, is erm, in a similarjob and with him we've discussed it.” (FO31, M68)

A remarkably high number of the forest owners, besides gettingthe first idea for protection, had received support for decision makingfrom forestry and agricultural magazines and newspapers (Fig. 3).The owners read experiences of those owners who had alreadystarted to protect their forests. Internet as an information channelwas used particularly in fixed-term agreements. There were ownerswho replied that they did not receive or search for information fromany other source than the other party of the agreement; however,these owners felt that they had received enough information to beable to make a decision.

members during the whole protection process (descending order sorted by the share ofcontacts in permanent protection).

Permanentagreement, %(n=19)

Fixed-termagreement, %(n=25)

[Number of owners are in squarebrackets]

ELY 100 [19] 16 [4]Forestry Centre, FC 79 [15] 100 [25]Family members 79 [15] 80 [20]Neighbours 63 [12] 60 [15]Forest Management Association, FMA 58 [11] 20 [5]Relatives (including other owners injoint ownerships)

47 [9] 60 [15]

Timber-buying company 26 [5] 32 [8]Familiar expert (e.g., peer forest owner) 26 [5] 32 [8]Another forest owner with a similaragreement

21 [4] 12 [3]

Other forest-related organisations 11 [2] 0Other 11 [2] 8 [2]Average number of contact parties 4.2 3.1

Average number of contact parties does not include the contact with the other party of theagreement. Difference in the number of contact parties between the two agreement typesis significant (p≤0.05).

4.1.3. Decision stageThe decision about the protection was only seldommade alone. In

jointly-owned forests, as well as in families, there were several dis-cussions and often the protection had been under consideration fora long time. Principally, those who owned the forest participated inthe decision making. Normally, one of the owners, typically male,took care of the process both in families and in jointly-owned forests.

“… I always make copies of this to everyone and everyone gets toread their own and be in touch and, everyone's been happy with thisway of doing it and going forward.” (FO28, joint ownership, M65)

Most owners included their spouse into making the decision, eventhough the spouse was not always a forest owner. Owners' children,as future forest owners, often participated in the decision making aswell. In addition, if the holding was inherited from parents whowere still alive, they were asked for approval.

Most owners replied that after the first contact with ELY or FC, theprocess proceeded easily and owners got on well with the officials.They communicated by email, phone and mail. Typically, owners met

the officials at least once in the forest: first, to assess whether the forestwas appropriate for protection and second, to determine the amount oftimber and its value. There were several cases of absentee owners. Insome of these cases, the owners did not meet the officials at all duringthe process. However, according to owners and professionals, the com-munication in these distance processes was smooth.

“I haven't even seen these people, these people that all of it has beendealt with over the phone and by e-mail and then the papers havebeen signed via post.” (FO31, M68)

4.1.4. Implementation and confirmation stageAfter making the agreement, some owners openly talked about the

protection agreement with their familiars. Some of the fixed-term pro-tectors briefly discussed the agreement with timber-buying companiesor with officials of the local FMA, for example, while conducting timbertrade in adjacent areas. Relatives who had had no decision makingpowerwere typically informedafterwards about theprotection. Althoughseveral owners had mentioned the protection to their neighbours, there

Table 4Innovativeness scores of fixed-term protectors.

Criterion Information gathering

Initiative 1 2 3

1 0 0 0

2 4 5 0

3 0 9 7

Late adopters 9

Early adopters 16

87K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

were only a few who had really discussed or recommended the protec-tion to their acquaintances. Contrary to open-minded owners, someeven wanted to keep quiet because they were afraid to become markedas conservationists. Despite the fact that owners thought that protectionis a positive thing, not all of themwanted to spread the “gospel” of volun-tary protection.

“… we had the need to get a story, a METSO-themed, a few stories.Well forest owner wouldn't go for it because he is in the Forest Man-agement Association's payroll or he like gets his salary from there. …somehow he felt that there wouldn't be a wrong message.” (a profes-sional from FC, FO34)

The scarce feedback that owners received was mainly positive. Forinstance, neighbours who owned summer cottages near the protectedforests were satisfied. However, a few owners thought that negativefeelings could be seen from the face of the neighbour even thoughthey were not spoken aloud. The comments from timber-buying com-panies were mainly neutral or they did not comment at all; however,a few of the salesmen made harmless jokes about the owner's deci-sion to protect.

Table 2 shows that permanent protectors received informationfrom a wider network, especially from forest-related organisations,than fixed-term protectors. However, timber-buying companies wereinformed about the protection more often in fixed-term agreements.

4.2. The characteristics of innovation among adopter categories

Therewere 19 ownerswhohadmade a permanent agreement, 13 ofthem were classified as early adopters and 6 as late adopters (Table 3).Among the 25 forest owners who made a fixed-term agreement, 16were early adopters and 9 late adopters (Table 4).

4.2.1. CompatibilityEarly adopters, especially permanent protectors, were typically

highly protection-minded and even called themselves conservation-ists (Table 5). Statistically significant differences between early andlate adopters in permanent agreements were found in the numberof contacts during the agreement and level of education (Table 6).In addition, some statistically significant differences, were found be-tween permanent and fixed-term protectors (Table 6). Several ofthe early adopters in permanent agreements did not conduct timbersales at all during the time they owned the forest and some evenbought their holding in order to protect it. Fixed-term protectors,both early and late adopters, recognised an important, restrictedarea from their forests. These areas had already been saved from cut-tings for decades and even by the former generation. These ownersbelieved that not everything needed to be used commercially. Some ofthem would have been willing to protect their area even permanently.

Among the late adopters, there were owners who had unsatisfac-tory experiences from the previous nature protection processes and

Table 3Innovativeness scores of permanent protectors.

Criterion Information gathering

Initiative 1 2 3

1 1 1 0

2 1 2 2

3 1 8 3

Late adopters 6

Early adopters 13

these owners were slightly afraid of losing the authority over theirforest if they made a permanent agreement. Protection was theleast compatible for the late adopters who made a permanent agree-ment; some of them even felt some kind of pressure to protect. How-ever, most of them admitted that they were also willing to protectand some of them were as protection-minded as early adopters, butnot that eager to take an initiative. A few mentioned that they feltthey were too old to conduct cuttings or regeneration actions and itwas easier for them to protect the forest.

4.2.2. Relative advantageRelative advantage mainly considers the amount of compensation

with respect to the alternative use (revenues from cutting) of the for-est instead of protection. If an owner is willing or has the opportunityto cut the forest, the relative advantage of protection is lower than ifthere are no preconditions to harvest. In permanent agreements, onlya few of the early adopters considered cutting the forest (Table 5). Onthe other hand, better compensation was a reason to select the per-manent protection instead of a fixed term. Approximately one thirdof fixed-term protectors had been considering cuttings instead of pro-tection. They also pointed out that in some part of the forest, the cuttingswere already forbidden by law. Getting at least some compensation wasone but a secondary reason for actually making the protection agree-ment. In permanent agreements, several late adopters considered cut-tings; however, like in fixed-term agreements, they admitted that thegrowing stockwas already old and rotten or that it would have been dif-ficult tomake cuttings due to awet terrain or steep slopes. Early adopterswith fixed-term agreementsweremost satisfiedwith the compensation,while late adopters with permanent agreements were less satisfied oruncertain about whether the compensation was enough (Table 5).

4.2.3. ComplexityMost owners were satisfied with the forestry professionals' actions

and the protection process was easy for them. A few of the earlyadopters with a permanent agreement were even somehow ahead ofthe professionals in protection issues. They would have wanted to pro-tect their forest earlier, thus finding the right professional from the right

Table 5Summary of the owners' perceived importance of different attributes affecting the in-novation adoption. Ease is inversed complexity.

Adopter category Early Late

Agreement type Permanent Fixed-term Permanent Fixed-term

Compatibility High Medium Medium/Low Medium

Relative advantage High Medium Low Medium

Ease Medium High Medium High

Trialabililty Low High Low High

Observability High Medium Low Medium

Table 6Differences in owners' background characteristics with respect to agreement andadopter types.

Agreement type Permanent Fixed-term

Adopter category Early(n=13)

Late(n=6)

Early(n=16)

Late(n=9)

Number of contact parties during theagreement

4.7 3.0 3.0 3.3 a

Size of the holding (ha) 42 65 58 55Average share (%) of protected area oftotal forest area

38 24 13 9 a

Elapsed time since the latest timbertrade (years)

8 5 2 2 a

Age 59 66 53 61Female (%) 31 33 25 22Joint ownership (vs. individual) (%) 8 17 25 44Matriculation examination (%) 54 0 38 44Existing forest plan (%) 54 83 94 100 a

Distance forest owner (%) 46 50 25 44

Bold = the difference is significant between early and late adopters (p≤0.05).a Differences between thepermanent andfixed-termagreements are significant (p≤0.05).

88 K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

organisation was difficult. Some of the late adopters with permanentagreements felt that the processwas slightly difficult. They had to nego-tiate several times with ELY to be able to agree upon the amount ofcompensation or restrictions for forest usage. The process was easyand smooth for fixed-term protectors. Some of them also had anupfront assumption that the process with the FC was simpler thanwith the ELY. This was partly the reason why they ended up with thefixed-term agreement.

4.2.4. Trialability and observabilityAlthough it is difficult to test the protection agreements, the nature

of fixed-term agreements can be understood so that the first 10-yearperiod gives the owner a possibility to experimentwith the biodiversityprotection. If the experiences are positive, the result can be a secondfixed-term or a permanent agreement. Trialability was important onlyfor half of the owners who were early adopters with fixed-term agree-ments. These owners mentioned that they were the first ones to havethis kind of agreement among their acquaintances; therefore, theyneeded to have a trial period, at least before considering a permanentagreement. Others did not raise trialability as an important attribute(Table 5).

Permanently protected areas of early adopters are often in impor-tant and visible places, for instance, near a home or summer cottage,next to a walking trail or by the shore of a lake. Moreover, individualsother than forest owners see or benefit from these areas. Most of theearly and late adopters with fixed-term agreements use the protectedareas actively for the purposes mentioned above. According to thesedata, late adopters with permanent agreements differed clearly fromthe others; their protected areas were typically hidden in the middleof the forest and these owners did not actively talk about the protectionwith other people (Table 5).

5. Discussion

5.1. The important role of the Forestry Centre and mass media

The main information sources for forest owners when protectingtheir forests in the METSO programme seemed to be forestry profes-sionals and the media. The present results highlight the role of the FC'sprofessionals, especially forest planners. According to the results, a forestplan, usually delivered by FC in Finland, is an important channel forowners to receive information about the possibilities of protecting theirforests. This is in line with the earlier studies; when adopting innova-tions, personal and frequent contacts with professionals have beenshown to have high importance (Hodges and Cubbage, 1990; Primmerand Wolf, 2009).

The FC professionals who are active in conducting protectionagreements can be called change agents. The concentration of protec-tion agreements with certain people is undoubtedly due to the tasksgiven to them inside the organisation, although the planners' ownvalues and motives may also have an effect. Even though it is desir-able that change agents exist, knowledge about protection issuesshould not only be in the hands of a limited number of professionals.The main messages about voluntary protection opportunities to pon-dering owners – especially to late adopters – should be coherent andeasily available from anyone within an organisation: it is importantthat change agents promote the innovation also within their own or-ganisation and not only among forest owners.

The role of local FMA's advisorswasminor in actualised agreements;they were typically only informed afterwards. However, for severalowners, the local FMA is themost important or the only source of forestadvice, at least in timber sales (Korhonen et al., 2012). When diffusingan innovation, it is important that the owners appreciate and trust thepeople delivering themessage and the FMAwould be a naturalmessen-ger of voluntary protection. Timber-buying companies, in turn, areoften perceived as contrary to nature protection. The results of thisstudy showed that some timber buyers had a biassed attitude towardsprotection; they were not interested or felt that protection was a com-petitor for their branch. It seems that owners are cautious of tellingabout their protection to timber-buying companies.

The message of voluntary protection has advanced through the FCwell because advisors in the FC represent “forestry people” for owners.In contrast, some owners named the officials of ELY as “nature protec-tion people”. For these owners, ELY was unknown and their functionswere seen as difficult and bureaucratic before the protection process.Furthermore, earlier results suggested that the least favourable alterna-tive for the initiation of nature protection was environmental adminis-tration, which might be due to the negative experiences of previousnature protection programmes (Horne, 2006). However, the results ofthis study revealed that afterwards, most of the owners who made thepermanent agreement with ELY were highly satisfied with the process.This observation indicates that organisational reputation may changeslowly but the change is possible.

According to the present results, information delivery, especiallythrough local newspapers or forestry magazines, has been effectiveand has led to agreements with early adopters. According to the inno-vation diffusion theory, when trying to reach late adopters, the effectof mass media will decrease and the significance of personal channelswill increase (Rogers, 2003). There are several studies that highlightthe importance of peer forest owners when diffusing somethingnew (e.g., Doolittle and Straka, 1987; Kittredge, 2004). However, theresults of this study indicated that in the informing or persuasionstages, only a few peer relationships existed. If an owner was seekinginformation from someone other than officials of the FC or ELY, s/heturned to those acquaintances who were also some kind of experts,for instance, a professional elsewhere or at least a more experiencedforest owner. These people were typically also relatives. The impor-tance of relatives' opinions might be due to the forest-owning culturein Finland; forests are perceived as a property of a family.

Whether themessage of voluntary protectionwill reach absentee for-est owners has been questioned in earlier studies (Mäntymaa et al.,2009). In this study, several absentee owners had made an agreementand the communication in these processes had been smooth. Althoughabsentee owners were served well by professionals, the communicationbetween neighbouring forest owners becomes difficult if their numberincreases. Several of the interviewed owners did not know their neigh-bours. Either the owners themselves were not living on their holdingsor their neighbours were not living there. Despite neighbouring forestowners knowing each other, only a fewof themhaddiscussed protectionmatters, at least in advance. This observation speaks for some coordinat-ed action aiming to bring neighbours together or in better communica-tion with each other.

89K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

5.2. Important attributes for late adopters

The theory of adopter categories has been criticised due to its limita-tions; adopter categories can be defined precisely only after the diffusion(Wright and Charlett, 1995). In addition, the existence of characteristicssuch as innovativeness has been questioned. As the diffusion of the vol-untary protection was ongoing in Finland when the data for this studywere collected, we could not define all adopter categories or forecastthe future. However, the principal characteristics of diffusion have beenrepeated similarly in different processes (see e.g., Doolittle and Straka,1987; Hodges and Cubbage, 1990) and therefore, the adopted approachcan be useful when aiming to find the attributes that late adopters con-sider important when making a protection agreement.

When classifying the forest owners into early and late adoptersaccording to the initiative and information gathering, some associa-tion between these two criteria was found (Tables 3 and 4). Therewere owners who were eager to protect (initiative for protection),but whose channels for information gathering were weak. This indi-cates that diverse channels for providing information in addition toready-made opportunities for protection are needed among forestowners.

In the present results, a common concern among late adopters, espe-cially with permanent agreements, was the relationship between com-pensation and future cutting income losses. Contrary to early adopters,who are visionary and willing to change, late adopters want rational so-lutions, efficiency and productivity (Moore, 2002; Rogers, 2003). Thetheory and present empirical results both support the suggestion byMäntymaa et al. (2009) that protection as a reasonable and alternativesource of income should be highlighted to owners. The results alsorevealed that some elderly owners were relieved not to conduct silvicul-tural operations anymore after signing a protection contract. The mes-sage of voluntary protection as an easy alternative to laborious forestryoperations, especially when the terrain is difficult and timber qualitylow, is worth spreading.

The question of whether to prefer permanent or temporary pro-tection agreements has been discussed in Finland (Mönkkönen etal., 2010). According to our results, it seems that trialability was im-portant especially for early adopters with fixed-term agreements,due to the lack of peer experiences. In contrast, late adopters didnot raise trialability as an important element. However, those classi-fied as late adopters mentioned that they wanted to have a temporaryagreement since they were afraid of losing authority over their ownforests. It is possible that when earlier experiences of previoustop-down nature protection programmes are superseded by morepositive voluntary protection experiences and related testimonialsfrom peers, the demand for temporary protection from the ownerswill decrease. However, the late adopters are not (yet) willing toshare their experiences or even admit that they are protecting theirforest. It remains to be seen whether this will change when the inno-vation diffusion progresses and protection becomes a social normamong forest owners.

When interpreting the results of this study, it must be noted thatthe data covered only one region in Finland and agreements madeduring 2009. The ownership structure in North Karelia does not dras-tically differ from the total population of forest owners; however, ahigher share of the area's forest owners has valid forest managementplans than the average Finnish forest owner (Hänninen et al., 2011).This may indicate that the interviewed forest owners are more activein different forestry issues than the average owner. In addition, NorthKarelia was the region where one of the METSO programme's pilotprojects was located (e.g., Kurttila et al., 2008). Thus, forest ownersin this region have become familiar with the programme and its in-struments. As a result, in other parts of the country, the diffusion pro-cess may not have yet progressed as far as in North Karelia. Inaddition, as pointed out by Mäntymaa et al. (2009), to be able to en-hance protection processes, it would also be important to study why

protection has failed and focus on those who have not consideredmaking protection agreements or whose protection process was notsuccessfully finalised.

5.3. Conclusions

The present study shows that adopting the concept and theories ofinnovations can be useful when the activities and policy processes inthe public sector are analysed and developed. Even though the resultsof this study considered voluntary biodiversity protection, the resultsare useful when implementing other innovations related to forestmanagement among family forest owners with diverse backgroundsand ownership motives.

Essential and functional elements as well as weaknesses in thecommunication chain, when introducing possibilities for voluntaryprotection to forest owners, were explored. It can be concluded thatdelivering the message of voluntary protection to forest owners hasso far been effective, especially via newspaper articles and in the con-text of making a regular forest plan with the FC. Among the advisorsof the FC even some change agents were found. The existence ofchange agents elsewhere, i.e., in other organisations and positions,should be promoted. It is essential that FC and ELY officials continuethe promotion of the programme and offer ready protection servicesto owners. However, to further diffuse the idea of voluntary protec-tion, a more profound change in attitude is needed among forestryprofessionals. More efforts are required from the purchasers oftimber-buying companies. In particular, FMA advisors could be excel-lent change agents. However, their currently absent communicationwas seen as a weakness in the actualised processes.

Almost all fixed-term protectors also had a forest plan (Table 6),indicating that fixed-term protectors were also active forest man-agers. Those who have protected their forest were active to acquireinformation. It can be derived that the voluntary protection messagehas so far reached the most active forest owners. Reaching the passiveowners is essential in the future and our theory based assumption isthat the message will not proceed to the laggards only through pro-fessionals. The results suggest a shift from general mass media infor-mation delivery to delivering and sharing concrete experiences. Forexample, peer-to-peer learning testimonials could accelerate the de-cision making of late adopters, who need to be convinced about theease and rationality of voluntary protection. To cross the chasm be-tween early and late adopters (Moore, 2002), active peer forestowners, who are proud of their protected property and willing toshare experiences with other owners, need to be found. These activeowners, who are appreciated among other owners, can even benamed as opinion leaders (Kittredge, 2004; Crona and Bodin, 2010).If and when positive peer experiences increase, trialability may notbe that important and the need of fixed-term protection contractsmay decrease.

Acknowledgements

The Niemi Foundation and the Graduate School of Forest Sciencesoffered financial support for the study. Mirja Rantala took part informing the interview questions. Pekka Saukkola interviewed some ofthe owners and transcribed the interviews. Nina Garlo translated thequotations. In addition, we are grateful to the professionals from theForestry Centre and ELY Centre in North Karelia for their participation.

References

Åkerman, M., Kilpiö, A., Peltola, T., 2010. Institutional change from the margins of nat-ural resource use: the emergence of small-scale bioenergy production within in-dustrial forestry in Finland. Forest Policy and Economics 12 (3), 181–188.

Bass, F., 1969. A new product growth model for consumer durables. Management Science15 (5), 215–227.

Bazeley, P., 2007. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. Sage Publications Ltd., London.

90 K. Korhonen et al. / Forest Policy and Economics 26 (2013) 82–90

Brown, K., 2002. Innovations for conservation and development. The GeographicalJournal 168 (1), 6–17.

Cheng, A.S., Danks, C., Allred, S.R., 2011. The role of social and policy learning in chang-ing forest governance: an examination of community-based forestry initiatives inthe U.S. Forest Policy and Economics 13 (2), 89–96.

Clearfield, F., Osgood, B.T., 1986. Sociological Aspects of the Adoption of Conservation Prac-tices. Soil Conservation Service, Washington, D.C. [Online document] Available at:http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb1045620.pdf. [Cited 4Jan 2012].

Creswell, J.W., 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed MethodsApproaches, third ed. Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

Crona, B., Bodin, O., 2010. Power asymmetries in small-scale fisheries: a barrier to gov-ernance transformability? Ecology and Society 15 (4), 32.

Cubbage, F., Harou, P., Sills, E., 2007. Policy instruments to enhance multi-functionalforest management. Forest Policy and Economics 9 (7), 833–851.

David, M., Sutton, C.D., 2004. Social Research, The Basics. Sage Publications, London.Doolittle, L., Straka, J., 1987. Regeneration following harvest on nonindustrial private

pine sites in the south: a diffusion of innovations perspective. Southern Journalof Applied Forestry 11 (1), 37–41.

Finnish Government, 2008. Government resolution on the forest biodiversity programmefor Southern Finland 2008–2016 (METSO). 15 pp. [Online document]. Available at:http://www.miljo.fi/download.asp?contentid=111229&lan=fi. [Cited 24 Jan 2012] .

Frank, G., Müller, F., 2003. Voluntary approaches in protection of forests in Austria. En-vironmental Science & Policy 6, 261–269.

Fritz-Vietta, N.V.M., Ferguson, H.B., Stoll-Kleemann, S., Ganzhorn, J.U., 2011. Conserva-tion in a biodiversity hotspot: insights from cultural and community perspectivesin Madagascar. In: Zachos, F.E., Habel, J.C. (Eds.), Biodiversity Hotspots. Springer,Berlin, pp. 209–233.

Hannerz, M., Boje, L., Löf, M., 2010. The role of internet in knowledge-building amongprivate forest owners in Sweden. Ecological Bulletins 53, 223–234.

Hänninen, H., Karppinen, H., Leppänen, J., 2011. Suomalainen metsänomistaja 2010(Finnich Forest Owner 2010). Working Papers of Finnish Forest Research Institute,208. Vantaa. (In Finnish).

Hodges, D.G., Cubbage, F.W., 1990. Adoption behavior of technical assistance forestersin the southern pine region. Forest Science 36 (3), 516–530.

Horne, P., 2006. Forest owners' acceptance of incentive based policy instruments in for-est biodiversity conservation — a choice experiment based approach. Silva Fennica40 (1), 169–178.

Horne, P., Koskela, T., Ovaskainen, V., Karppinen, H., Horne, T., 2009. Forest owners' at-titudes towards biodiversity conservation and policy instruments used in privateforests. In: Horne, P., Koskela, T., Ovaskainen, V., Horne, T. (Eds.), Safeguarding for-est biodiversity in Finland: citizens' and non-industrial private forest owners'views: Working Papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 119. Vantaa.

Hubbard, W.G., Sandmann, L.R., 2007. Using diffusion of innovation concepts for im-proved program evaluation. Journal of Extension 45 (5).

Kauneckis, D., York, A.M., 2009. An empirical evaluation of private landowner partici-pation in voluntary forest conservation programs. Environmental Management44 (3), 468–484.

Kittredge, D., 2004. Extension/outreach implications for America's family forest owners.Journal of Forestry 102 (7), 15–18.

Korhonen, K., Hujala, T., Kurttila, M., 2012. Reaching forest owners through their socialnetworks in timber sales. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 27 (1), 88–99.

Kurttila, M., Leskinen, P., Pykäläinen, J., Ruuskanen, T., 2008. Forest owners' decision sup-port in voluntary biodiversity-protection projects. Silva Fennica 42 (4), 643–658.

Leppänen, J., Sevola, 2012. Metsämaan omistus 2010. Metsätilastotiedote 8/2012. OfficialStatistics of Finland; Agriculture, forestry and fishery. [Online document]. Available

at: http://www.metla.fi/metinfo/tilasto/julkaisut/mtt/2012/metsamaan_omistus2010.pdf. [Cited 25 Jun 2012]. (In Finnish).

Ma, Z., Butler, B.J., Kittredge, D.B., Catanzaro, P., 2012. Factors associated with landown-er involvement in forest conservation programs in the U.S.: implications for policydesign and outreach. Land Use Policy 29 (1), 53–61.

Mäntymaa, E., Juutinen, A., Mönkkönen, M., Svento, R., 2009. Participation and com-pensation claims in voluntary forest conservation: a case of privately owned for-ests in Finland. Forest Policy and Economics 11 (7), 498–507.

Mayer, A.L., Tikka, P.M., 2006. Biodiversity conservation incentive programs for pri-vately owned forests. Environmental Science & Policy 9, 614–625.

Mickwitz, P., 2006. Environmental policy evaluation: concepts and practice.Commentationes Scientiarum Socialium, 66 . Gummerus, Vaajakoski.

Mönkkönen, M., Reunanen, P., Kotiaho, J.S., Juutinen, A., Tikkanen, O.-P., Kouki, J., 2010.Cost-effective strategies to conserve boreal forest biodiversity and long-termlandscape-level maintenance of habitat. European Journal of Forest Research 130(5), 717–727.

Moore, G.A., 2002. Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling Technology Products toMainstream Customers. NY Harper Business, New York.

Muth, R.M., Hendee, J.C., 1980. Technology transfer and human behavior. Journal ofForestry 78 (3), 141–144.

Oslo Manual, 2005. Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, third ed.OECD/Eurostat. [Online document]. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ramon/statmanuals/files/9205111E.pdf. [Cited 5 Jan 2012].

Palmer, M.A., Straka, T.J., Doolittle, M.L., 1985. Socioeconomic characteristics, adoptions of in-novations and non-industrial private forest regeneration. Mississippi Agricultural andForestry Experiment Station Information Bulletin, 72, pp. 108–117. [Online document].Available at: http://sofew.cfr.msstate.edu/papers/8614Palmer.pdf. [Cited 24 Dec 2011].

Paloniemi, R., Varho, V., 2009. Changing ecological and cultural states and preferences ofnature conservation policy: the case of nature values trade in south-western Finland.Journal of Rural Studies 25, 87–97.

Primmer, E., Wolf, S., 2009. Empirical accounting of adaptation to environmentalchange: organizational competencies and biodiversity in Finnish forest manage-ment. Ecology and Society 14 (2), 27.

Rametsteiner, E., Weiss, G., 2006. Innovation and innovation policy in forestry: linking in-novation process with system models. Forest Policy and Economics 8 (7), 691–703.

Rasamoelina, M.S., 2008. Adoption of sustainable forestry practices by non-industrialprivate forest owners in Virginia. Dissertation. Faculty of the Virginia PolytechnicInstitute. State University, Virginia. 225 p. [Online document]. Available at:http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-05232008-135626/unrestricted/Mami_dissertation_revised_07_01.pdf. [Cited 5 Jan 2012].

Rogers, E.M., 2003. Diffusion of Innovations, Fifth ed. Free Press, London.Schumpeter, J.A., 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts.Sheaffer, A.L., 2000. Diffusion of innovations model for agricultural and forest land-

owners. Dissertation, ETD Collection for Purdue University, Indiana.Suihkonen, L., Ahtikoski, A., Hynynen, J., Hänninen, R., Loiskekoski, M., 2011. Määräaikaiset

suojelukorvaukset ja laskennalliset tulonmenetykset vapaaehtoisessa metsienmonimuotoisuuden turvaamisessa (Compensations from fixed-term protectionand calculatory losses of incomes in voluntary protection of forest biodiversity).Working Papers of Finnish Forest Research Institute, 207. Vantaa. (In Finnish).

Weiss, G., Pettenella, D., Ollonqvist, P., Slee, P., 2011. Innovation in Forestry: Territorialand Value Chain Relationships. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Wright, M., Charlett, D., 1995. New product diffusion models in marketing: an assess-ment of two approaches. Marketing Bulletin 6, 32–41.