EMI Filter Design for a Single-stage Bidirectional and Isolated ...

Developmental Psychology Do Sensitive Parents Foster Kind Children, or Vice Versa? Bidirectional...

Transcript of Developmental Psychology Do Sensitive Parents Foster Kind Children, or Vice Versa? Bidirectional...

Developmental Psychology

Do Sensitive Parents Foster Kind Children, or Vice Versa?Bidirectional Influences Between Children’s ProsocialBehavior and Parental SensitivityEmily K. Newton, Deborah Laible, Gustavo Carlo, Joel S. Steele, and Meredith McGinleyOnline First Publication, April 7, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0036495

CITATIONNewton, E. K., Laible, D., Carlo, G., Steele, J. S., & McGinley, M. (2014, April 7). Do SensitiveParents Foster Kind Children, or Vice Versa? Bidirectional Influences Between Children’sProsocial Behavior and Parental Sensitivity. Developmental Psychology. Advance onlinepublication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0036495

BRIEF REPORT

Do Sensitive Parents Foster Kind Children, or Vice Versa? BidirectionalInfluences Between Children’s Prosocial Behavior and Parental Sensitivity

Emily K. NewtonStevenson University

Deborah LaibleLehigh University

Gustavo CarloUniversity of Missouri

Joel S. SteelePortland State University

Meredith McGinleyThe Chicago School of Professional Psychology

Bidirectional theories of social development have been around for over 40 years (Bell, 1968), yet theyhave been applied primarily to the study of antisocial development. In the present study, the reciprocalrelationship between parenting behavior and children’s socially competent behaviors were examined.Using the National Institute of Child Health and Development Study of Early Child Care data set(NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005), bidirectional relationships between parentalsensitivity and children’s prosocial behavior were modeled using latent variables in structural equationmodeling for mothers and fathers, separately. Children and their parents engaged in structured interac-tions when children were 54-month-olds, 3rd graders, and 5th graders, and these interactions were codedfor parental sensitivity. At 3rd, 5th, and 6th grades, teachers and parents reported on children’s prosocialbehavior. Parental education and child gender were entered as covariates in the models. The resultsprovide support for a bidirectional relationship between children’s prosocial behavior and maternalsensitivity (but not paternal sensitivity) in middle childhood. The importance of using a bidirectionalapproach to examine the development of social competence is emphasized.

Keywords: prosocial behavior, parental sensitivity, bidirectional relationships, social competence,parent–child relationships

Research on social development often focuses unidirectionallyon the impact of the social environment on children’s behavioraloutcomes. Research on prosocial behavior is no exception; mostempirical studies examine parenting styles and behaviors as pre-dictors of children’s prosocial outcomes. Yet many comprehensivetheories of social development stress the importance of bidirec-tional influences where the child is both shaped by and shapes the

social environment. Bell (1968) proposed a bidirectional theory ofparent–child relationships arguing against the dominant idea of thetime that parents should have a fixed set of parenting practicesindependent of children’s specific behaviors and that children’soutcomes were a direct result of the parenting they received.According to Bell’s theory, both the parent and child are activeparticipants in determining the social environment as well as thechild’s continued social development. Over the past 40 years, agrowing body of empirical evidence has supported these bidirec-tional child–parent dynamics in certain domains of development.

Bidirectional dynamics are well documented in the study ofantisocial behavior and its development (Lansford et al., 2011;Pardini, Fite, & Burke 2008; Vuchinich, Bank, & Patterson, 1992).For example, Patterson (1986) developed and tested a model ofantisocial development that elucidated its association with parent-ing behaviors. He found that boys in middle childhood and ado-lescence exhibiting defiant and coercive behaviors elicited harsherparenting when parents had poor skills and low social support, andthis association between parenting practices and children’s coer-cion resulted in positive feedback, further increasing children’santisocial behavior. Overall, the research on antisocial behaviorhas suggested that children are active in shaping the parenting

Emily K. Newton, Department of Psychology, Stevenson University;Deborah Laible, Department of Psychology, Lehigh University;Gustavo Carlo, Department of Human Development and Family Stud-ies, University of Missouri; Joel S. Steele, Department of Psychology,Portland State University; Meredith McGinley, Department of BusinessPsychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

Funding was provided to the second and third authors by NationalInstitute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 1R03HD060677.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Emily K.Newton, Department of Psychology, Stevenson University, 1525 Green-spring Valley Road, Stevenson, MD 21153. E-mail: [email protected]

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

Developmental Psychology © 2014 American Psychological Association2014, Vol. 50, No. 6, 000 0012-1649/14/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0036495

1

environment they experience and that it is wise to consider bidi-rectional relationships—not just unidirectional influences—wheninvestigating the course of children’s social development.

Although past research has examined bidirectionality in thedevelopment of antisocial behavior, little attention has been paid tothe ways in which sensitive parenting and children’s prosocialitymay be mutually influential. Research on prosocial behavior (i.e.,actions or tendencies intended to benefit others, such as showingconcern for others and a willingness to help or share) has shownthat parenting behaviors, including parental sensitivity, influencechildren’s prosocial behaviors early in development (Brownell,Svetlova, Anderson, Nichols, & Drummond, 2013; Davidov &Grusec, 2006; and see Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006; Grusec,Davidov, & Lundell, 2002; Hastings, Utendale, & Sullivan, 2007,for reviews). There are multiple theoretical mechanisms by whichparental sensitivity may have such an influence. Sensitive parent-ing is characterized by warm, supportive, and contingent responsesto children’s needs (Biringen & Easterbrooks, 2012). By experi-encing sensitive responses to their needs, children may learn to beprosocial by directly observing and then modeling their parents’prosociality (e.g., Rice & Grusec, 1975). In addition, since sensi-tive parents are adept at reading the cues of their children, theymay be especially likely to scaffold children’s social-cognitiveawareness by directing their children’s attention to the cues andneeds of others (e.g., Krevans & Gibbs, 1996). Based on thisawareness, children of sensitive parents may respond more proso-cially to others’ needs. These mechanisms provide support for aunidirectional model of parental sensitivity and prosocial behavior,but we also posit that prosocial children engender sensitive re-sponses from their parents. As children develop in middle child-hood, their growing capacities to consistently display prosocialbehaviors might elicit more positive parenting behaviors, includingmore warm, responsive interactions (just as children exhibitingantisocial behaviors elicit harsher or more timid parental re-sponses). These theoretical mechanisms provide strong support forbidirectional models of prosocial development and sensitive par-enting.

If prosocial behavior and parental sensitivity did not evidencesome stability, we would not expect them to be substantiallyinfluential over time. However, parental sensitivity is moderatelystable in infancy and early childhood (Corwyn & Bradley, 2002;Holden & Miller, 1999; Joosen, Mesman, Bakermans-Kranenburg,& van IJzendoorn, 2012; Knafo & Plomin, 2006) and later inchildhood (Holden & Miller, 1999; Rimehaug, Wallander, & Berg-Nielsen, 2011). Studies of prosociality have also shown modeststability, with prosociality generally becoming more stable aschildren enter middle childhood and continue into adolescence(Eisenberg et al., 2006), suggesting that these later years could bean important time in which bidirectional effects between prosocialbehavior and parenting emerge.

Due to their stability and the theoretical basis for mutual influ-ence, parental sensitivity and prosocial behavior seem to be primecandidates for a bidirectional association evidencing the complex-ity of positive (not just negative) development. Indeed, Bell (1968)briefly suggested that parental warmth (one component of parentalsensitivity) and children’s moral development would be bidirec-tionally related, but no empirical tests of this have been conducteduntil quite recently. In a 3-year, longitudinal study of adolescents,Carlo and colleagues (Carlo, Mestre, Samper, Tur, & Armenta,

2011) found bidirectional relationships between parental warmthand youth prosocial behaviors using youth self-report assessmentsof both constructs. They found that youth moral reasoning, whichwas positively associated with their prosocial behavior from theprevious year, was in turn positively associated with their mothers’warmth the following year, and vice versa. In much youngerchildren, Barnett, Gustafsson, Deng, Mills-Koonce, and Cox(2012) recently found mixed evidence of bidirectional associationsbetween sensitive parenting and toddlers’ social competence, pri-marily showing that social competence at 24 months of age pre-dicted later sensitive parenting rather than the reverse. Thesestudies of older and younger children suggest that middle child-hood, the unexplored gap, may be an important developmentalperiod for positive bidirectional influences in the parent–childrelationship. During this period of development, children are be-coming increasingly autonomous, engaging in peer interactionsmore frequently, and experiencing a wider variety of social con-texts (Raikes & Thompson, 2005; Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker,2006). During this time, the nature of the parent–child relationshipis changing as children’s ecologies and capacities change (Rich-ardson, 2005). This period of transition may also involve importantshifts from unidirectional to bidirectional influences in positivedevelopment.

Parental sensitivity depends, of course, on the specific parentinteracting with the child. Both maternal behavior and paternalbehavior have previously been examined as predictors of chil-dren’s prosocial outcomes, often resulting in different patterns foreach parent. Several studies have found maternal behavior to havea stronger influence than paternal behavior on children’s prosocialbehaviors (Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Hastings, McShane, Parker,& Ladha, 2007). For example, Hastings, McShane, et al. (2007)found that maternal style, behaviors, and cognitions predictedchildren’s sex-typed prosocial behaviors, while paternal style, be-haviors, and cognitions were unrelated to children’s prosocialbehaviors with few exceptions. Davidov and Grusec (2006) foundthat maternal sensitivity significantly predicted children’s empathyand prosocial behavior, but paternal sensitivity was not signifi-cantly predictive of children’s empathy and prosocial behavior. Itseems likely that different parents would have different degrees ofinfluence on the same child depending on the quality of eachparent–child relationship and the amount of time spent together orin conflict. From a bidirectional perspective, it also makes sensethat children’s behaviors would differentially affect parenting be-haviors based on the quality and intensity of the parent–childrelationship and interactions. Indeed, Carlo and colleagues (2011)found significant paths from adolescent prosocial behavior to laterparental warmth from mothers but not from fathers. Becausematernal and paternal parenting have been shown to be differen-tially related to children’s prosocial development, we exploredwhether this was also the case for bidirectional relationships be-tween parental sensitivity and children’s prosocial behaviors inmiddle childhood.

In the present study, we longitudinally examined the bidirec-tional relationships between children’s prosocial behavior and bothmaternal and paternal sensitivity in early and middle childhoodusing the National Institute of Child Health and Human Develop-ment Study of Early Child Care (NICHD SECC; NICHD EarlyChild Care Research Network, 2005). To our knowledge, this isthe first study to examine the bidirectional relations of parenting

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

2 NEWTON, LAIBLE, CARLO, STEELE, AND MCGINLEY

and prosocial behaviors in middle childhood. We hypothesizedthat parental sensitivity assessed when children were 54 monthsold, in third grade (9 years old), and in fifth grade (11 years old)would influence children’s prosocial behavior when children werein third grade (9 years old), fifth grade (11 years old), and sixthgrade (12 years old) and that children’s prosocial behavior wouldhave a reciprocal relationship with parental sensitivity. We alsoexpected to find different bidirectional patterns in maternal andpaternal sensitivity in relation to children’s prosocial behaviors.Because maternal behaviors have been shown to have a greaterimpact than paternal behaviors on children’s prosocial outcomes(Davidov & Grusec, 2006) and because earlier prosocial behaviorshave been shown to have a greater impact on later maternal thanpaternal warmth (Carlo et al., 2011), we expected to find suchsimilar patterns of bidirectional relations in the present study.

Method

Sample

The National Institute of Child Health and Human DevelopmentStudy of Early Child Care (NICHD SECC) data set was used toexamine the research questions of the current study. The NICHDSECC is a longitudinal investigation of 1,364 participants frombirth to age 15 and includes four phases of data collection. Par-ticipants were originally recruited from 10 sites across the UnitedStates. Details on the procedures used to recruit families for thisproject can be found in NICHD Early Child Care Research Net-work (2005). Because our research question is specific to early andmiddle childhood, the current study uses data gathered during thesecond and third phases of the NICHD SECC, including assess-ments at 54 months as well as third, fifth, and sixth grades. Thesample included 1,364 children (52% boys) along with their par-ents and teachers. Ten percent of the mothers had less than a highschool education, and 35% had at least one college degree; 24% ofthe children were of an ethnic minority; and 14% of mothers weresingle when the child was born. In order to ensure that the fatherin the paternal model was the same caregiver across all time pointswhere paternal sensitivity was assessed, only participants withindividuals identified as “father” (compared to mother’s partner,grandparent, or other caregiver) at 54 months, third grade, and fifthgrade were included in the sample for the paternal model. Eightpercent of fathers had less than a high school education, and39% of fathers had at least one college degree. Because manyparticipants had other secondary caregivers participating (e.g., agrandparent) or did not have a secondary caregiver participatingin the study during these waves of data collection, the samplefor the paternal model (N � 459) is smaller than the sample forthe maternal model (N � 1,155).

Attrition in this sample was related to several covariates. Weassessed missingness in parental sensitivity measures at any timepoint, as well as in prosocial behaviors reported by mothers.Missing data on maternal sensitivity was significantly related toboth mother’s education (�2 � 4.72, p� .030) and gender (�2 �4.34, p � .037), with missing data on sensitivity being associatedwith mothers who reported lower education as well as for mothersof boys. Father’s education was also related to missing reports ofprosocial behaviors (�2 � 7.29, p � .007), with higher levels ofreported education in fathers being associated with more missing-

ness in maternal reports of prosocial behavior. No other differ-ences were found with regard to missing data. Child gender andparent education were used as covariates in the final analyses.

Measures

Prosocial behavior (third, fifth, and sixth grades). Mothersand teachers completed a modified version of Ladd’s revision ofthe Child Behavior Scale (Ladd & Profilet, 1996). The question-naire was designed to measure the study child’s relationships andbehaviors with peers in third, fifth, and sixth grades. Only thenine-item prosocial subscale was used in the current analyses. Oneexample item states, “[The target child] seems concerned whenclassmates are distressed.” Respondents rated the study child’sprosocial behavior with peers on a 3-point scale (0 � not true, 1 �sometimes true, and 2 � often true) for each of the nine items. Thisscale had adequate internal consistency with both reporters in theNICHD SECC sample (�s ranged from .80 to .88), and the reportsfrom mothers and teachers were consistently correlated (rs � .28,p � .01).

These two reports were used to identify a latent construct ofprosocial behavior for the child that was meant to reflect theoverall prosocial behavior of the child regardless of context, eitherat home with parents or in school. How this construct influencedthe reported scores was set to be equal across all occasions.Additionally, the averages of these scores over time were also setto be equal. This was done to ensure that we were measuring thesame construct at each time point, and any difference over timewould be reflected at the level of the construct of prosocialbehavior and not attributable to nuances in measurement (Wida-man & Reise, 1997). However, there is an additional dependencypresent among these latent constructs that results from the fact thatthe mother’s reports represent the same mother reporting on thesame child over time, whereas the teacher reports are from differ-ent teachers at each time point. To account for this dependency wecorrelated the unique portion of the mother’s reports across time inour models.

Parental sensitivity (54 months, third grade, and fifthgrade). Maternal and paternal sensitivity were assessed sepa-rately using structured observational tasks specifically designedfor children in early and middle childhood. At 54 months, therewere three components: a maze task, a block tower reconstructiontask, and a free play task with puppets. At third and fifth grades,the structured observational tasks consisted of a planning activityand a discussion activity. These interactions at each assessmentwere videotaped, and coders rated each parent on a scale from 1(very low) to 7 (very high) on two dimensions: respect for thechild’s autonomy and supportive presence. A high score on respectfor autonomy indicated that the parent encouraged the child tonegotiate a problem on his or her own and that the parent acknowl-edged the child’s perspective throughout the interaction. A highscore on supportive presence indicated that the parent was emo-tionally supportive, reinforced the child’s successes, and showedconfidence in the child. These scales had moderate internal reli-ability (�s ranged from .78 to .85). Two raters coded 200 parent–child interactions independently for each age and parental partic-ipant and reached satisfactory interrater reliability (rs ranged from.57 to .84).

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

3KIND CHILD, OR SENSITIVE PARENT?

As with the measures of prosocial behavior, we used the twomeasures of parental sensitivity—respect for autonomy and sup-portive presence—to create a latent variable at each time point.This was done for mothers and fathers separately. Here as well, weequated the influences of the construct on the observed measuresas well as the means of each measure at each time point. Again,this was done to ensure we were measuring the same constructover time and that any changes over time were at the level of theconstruct and not a result of nuances in measurement.

Results

Descriptive information and bivariate correlations appear inTable 1. Bivariate correlations revealed that all of the study vari-ables (with the exception of some of the controls) were signifi-cantly correlated in the expected directions.

Main Data Analysis Plan

To reasonably address any potential bias that could result frommissing data, full information maximum-likelihood estimation wasused to fit the models, along with the inclusion of our two cova-riates, parent education and gender (0 � Female, 1 � Male). Allmodels were fit using Mplus Version 6.11 for Linux (Muthén &Muthén, 1998–2010).

In order to examine the cross-lagged (i.e., bidirectional) rela-tions among social behaviors and parental sensitivity, we specifieda path model wherein we regressed later prosocial behavior ontothe previous wave’s parenting (e.g., fifth grade prosocial behaviorwas regressed onto third grade parenting) and regressed laterparenting onto the previous wave’s prosocial behavior (fifth gradeparenting was regressed onto third grade prosocial behavior).These cross-lagged effects were accompanied by autoregressiveeffects in which we used previous values of the construct to predictfuture values (e.g., parental sensitivity at third grade predictingparental sensitivity at fifth grade). Finally, gender and parentaleducation (collected just following the birth of the child) werecontrolled for in the models by regressing both parenting andprosocial behavior variables onto these variables.

To assess model fit, we adopted the guidelines proposed byHu and Bentler (1998, 1999). We report the following indices

for all fitted models: the root-mean-square error of approxima-tion (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the stan-dardized root-mean residual (SRMR). Good model fit is re-flected by values of SRMR � .08 and CFI � .95 or RMSEA �.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). See Kline (2010) and Martens (2005)for introductory information about these fit indices and theiruse.

Cross-Lagged Model Results for Maternal Sensitivityand Prosocial Behavior

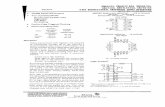

Path model results for the cross-lagged model for prosocialbehaviors and maternal sensitivity are illustrated in Figure 1.Results showed that this model had acceptable fit (SRMR �.050; CFI � .970; RMSEA � .045, 90% confidence interval[CI; 0.038, 0.051]). Only the first wave of earlier maternalsensitivity predicted subsequent prosocial behavior, and thethird grade prosocial behavior additionally predicted fifth gradematernal sensitivity.

Results of the inclusion of covariates in this model areillustrated in Figure 2. Maternal education was associated withsensitivity at all time points, and prosocial behavior at onlythird grade. Thus, higher levels of maternal education wereassociated consistently with more maternal sensitivity and alsoprosocial behavior from their children during third and fifthgrades. Gender was also associated with prosocial behavior;girls were rated as significantly more prosocial than boys dur-ing third grade. Finally, gender was also associated with ma-ternal sensitivity at third grade only. Mothers with girls wererated as more sensitive than mothers with boys at third grade.Standardized estimates are reported in Table 2.

Cross-Lagged Model Results for Paternal Sensitivityand Prosocial Behavior

Path model results for the cross-lagged model for prosocialbehaviors and paternal sensitivity are presented in Figure 3. Re-sults showed that this model had good fit (SRMR � .039; CFI �.990; RMSEA � .025, 90% CI [0.000, 0.039]). Prosocial behaviorat third grade was predicted by earlier (54 months) sensitivity;however, the bidirectional path was not statistically significant.

Table 1Descriptive Data and Bivariate Relations Between the Variables for Children’s Prosocial Behavior and Parental Sensitivity

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 M (SD)

1. Maternal education — .65�� .04 .36�� .40�� .34�� .13�� .18�� .23�� .23�� .27�� .21�� 14.23 (2.51)2. Paternal education — .01 .24�� .29�� .21�� .19�� .24�� .20�� .10� .14�� .12� 15.41 (2.55)3. Gender — .01 .12�� .12� .00 .16�� .01 .21�� .22�� .22��

4. Maternal sensitivity 54m — .39�� .39�� .18�� .21�� .17�� .24�� .23�� .27�� 10.38 (2.23)5. Maternal sensitivity 3rd — .46�� .23�� .26�� .24�� .28�� .26�� .22�� 9.88 (1.97)6. Maternal sensitivity 5th — .20�� .27�� .24�� .27�� .27�� .24�� 10.09 (1.77)7. Paternal Sensitivity 54m — .30�� .24�� .14�� .14�� .12�� 10.97 (1.93)8. Paternal Sensitivity 3rd — .36�� .20�� .23�� .13�� 10.76 (1.75)9. Paternal sensitivity 5th — .17�� .17�� .20�� 10.48 (1.77)10. Prosocial behavior 3rd — .51�� .46�� 1.57 (0.35)11. Prosocial behavior 5th — .58�� 1.56 (0.34)12. Prosocial behavior 6th — 1.57 (0.34)

Note. 54m � 54 months; 3rd to 6th � third grade to sixth grade.� p � .05. �� p � .01.

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

4 NEWTON, LAIBLE, CARLO, STEELE, AND MCGINLEY

Results of the inclusion of covariates in this model are illus-trated in Figure 4. Paternal education was related to third gradeprosocial behavior and paternal sensitivity at 54 months and thirdgrade. Fathers who were more educated were more sensitive andhad children who were more prosocial. Gender was associatedwith prosocial behavior during third grade such that girls wererated as more prosocial. Finally, gender was related to paternalsensitivity at third grade only, such that fathers with daughterswere more sensitive than fathers with sons at third grade. Stan-dardized estimates are reported in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine bidirectional linksbetween prosocial behavior and parental sensitivity in middlechildhood. Although much of the past research has explored thebidirectional relationship between antisocial behaviors and nega-tive qualities of parenting in this age group, the current studyfocuses attention on bidirectional relationships between children’sprosocial behaviors and positive parenting qualities. Moreover, weexamined these relations in a cross-lagged model using data froma relatively large, diverse sample of mothers, fathers, and childrenin the United States. In general, the findings yield evidence forbidirectional relations between mothers’ (less so for fathers’) sen-sitivity and children’s prosocial behaviors.

Although untested in previous research with this age group,theorists have suggested that children’s prosocial behavior should

predict their parents’ subsequent sensitivity (e.g., Bell, 1968). Thistheoretical claim is supported by evidence from the mother–childdyads in the present study. Accordingly, children’s prosocial be-havior predicted mothers’ subsequent sensitivity even when con-trolling for concurrent prosocial behavior and past parental sensi-tivity. In contrast, children’s prosocial behavior did not predictpaternal sensitivity. These findings suggest that there is a bidirec-tional relationship between mothers’ parenting and children’sprosocial behavior in middle childhood, adding to research onearlier childhood (Barnett et al., 2012) and adolescence (Carlo etal., 2011) showing similar patterns. Children who are more kind,compassionate, and helpful earlier in childhood may be morelikely to elicit more responsive and warm parenting from theirmothers, but not necessarily their fathers, later in childhood.

Perhaps most interesting was that these bidirectional modelsdiffered substantially for mothers and fathers. Children’s prosoci-ality did not predict their fathers’ parenting, suggesting that pater-nal warmth and responsive behavior may fully depend on otheraspects of parents, their children, and their relationship, includinggenetic predispositions and earlier experiences in the parent–childrelationship. Indeed, even though the bidirectional path fromprosociality to sensitive parenting was not significant, paternaleducation related to fathers’ sensitivity, suggesting that other con-structs are more important in explaining fathers’ sensitivity thanchildren’s earlier prosociality. In addition to the lack of a bidirec-tional relation between prosociality and fathers’ sensitivity, thepredictive association between paternal sensitivity and children’slater prosociality was significant only early in development, fromfathers’ sensitive behavior with their 54-month-olds to their thirdgraders’ prosocial behavior. These findings are consistent withother research in early childhood and in adolescence that fathers’parenting is less associated than mothers’ parenting with children’sprosocial behaviors (Carlo et al., 2011). Research has suggestedthat mothers and fathers do play different parental roles with

Figure 2. Covariate influences for the maternal sensitivity model.SensM � maternal sensitivity; ProS � prosocial behavior; EdM � mater-nal education; k � kindergarten; Male indicates gender (1 � Male).Subscripts indicate measurement occasion for all variables. Significantpositive paths are indicated with ���, significant negative paths are indi-cated with �-�, and significant paths are additionally represented withthicker lines. Squares represent manifest variables, circles represent latentvariables, single-headed arrows represent regressions, and dotted lines areincluded for reference to the full structural model specification.

Figure 1. Maternal sensitivity path model. SensM � maternal sensitivity;ProS � prosocial behavior; SP � supportive presence; RA � respect forautonomy; MR � mother report; TR � teacher report; u � manifestvariable uniqueness. Subscripts indicate measurement occasion for allvariables except uniquenesses. Significant paths are indicated with ���;significant structural paths are additionally represented with thicker lines.Squares represent manifest variables, circles represent latent variables,single-headed arrows represent regressions, and double-headed arrowsrepresent correlations.

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

5KIND CHILD, OR SENSITIVE PARENT?

children in middle childhood. Furthermore, some research hassuggested that fathers spend less time with their children and thatthe time spent with their children differs in character compared tothat of mothers (Collins & Russell, 1991), which could makefathers less susceptible to the influence of their children’s proso-ciality. Alternatively, given the evidence of gender differences inspecific types of prosocial behaviors (Eagly & Steffen, 1986),fathers’ parenting may be associated with specific forms of proso-cial behaviors (e.g., risky, instrumental) but not other forms ofsuch behaviors. Finally, these findings could also reflect differ-ences between fathers and mothers in their expressions of nurtur-ance and affection with their young children, such that mothersmay be stronger models for expressing prosocial behaviors. Al-though fathers’ socialization has not been studied as intensely asmothers’ socialization (Lamb, 2000), fatherhood is a rapidlyevolving construct (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth,& Lamb, 2000), and more research is required to understand thedifferent ways that fathers may impact and be impacted by theirchildren’s social development.

In contrast to the results from the father–child dyads, the resultsfrom the mother–child dyads showed significant bidirectionalassociations between prosocial behavior and maternal sensitivity.Consistent with prior research on the relations between maternalsensitivity and children’s prosocial behavior, we generally foundthat mothers’ sensitivity with their younger children predicted

greater prosociality for those children at later ages. Specifically,54-month-old children who experienced more sensitive interac-tions with their mothers were more prosocial at third grade, sug-gesting that maternal sensitivity does indeed shape the develop-ment of children’s prosociality. This same finding was evident inthe paternal model, although the bidirectional path from children’sprosocial behavior to later sensitivity was not. These findings fitwell with a traditional view of parental socialization (Hastings,Utendale, & Sullivan, 2007). Parents who behave moresensitively—including more warmly and responsively—towardtheir children may foster prosociality in their children throughmodeling responsive behavior. These expected patterns hold evenwhen controlling for children’s gender and parents’ educationlevel, although it is likely that other factors, including geneticpredispositions and experiences earlier in development, also influ-ence both children’s prosocial behavior and parental sensitivity.

Another finding that fits well with previous research is thepattern of gender differences in prosocial behavior. As has beenfound in other studies (see Fabes & Eisenberg, 1998, for a meta-analysis), girls were reported as more prosocial than boys at allwaves. Although the patterns and strengths of gender differencesin prosocial behavior vary widely depending on the type of as-sessment used (self-report, other-report, behavioral) and the age ofthe person, middle childhood is a developmental period where thegender difference in prosociality is quite robust in favor of girls

Table 2Maternal Sensitivity Model

Variable Estimate SE p

95% CI

Lower Upper

Structural regressionsMaternal sensitivity ¡ Prosocial behavior

54m ¡ 3rd 0.355 0.045 .000 0.266 0.4443rd ¡ 5th –0.075 0.065 .247 –0.203 0.0525th ¡ 6th 0.010 0.056 .857 –0.099 0.119

Prosocial behavior ¡ Maternal sensitivity3rd ¡ 5th 0.311 0.069 .000 0.175 0.447

Prosocial behavior ¡ Prosocial behavior3rd ¡ 5th 0.944 0.082 .000 0.783 1.1045th ¡ 6th 0.978 0.060 .000 0.860 1.097

Maternal sensitivity ¡ Maternal sensitivity54m ¡ 3rd 0.348 0.037 .000 0.276 0.4213rd ¡ 5th 0.324 0.045 .000 0.235 0.413

CovariatesMother’s education ¡

Prosocial behavior 3rd 0.208 0.042 .000 0.126 0.290Prosocial behavior 5th 0.017 0.034 .608 –0.049 0.083Prosocial behavior 6th 0.000 0.028 .998 –0.054 0.054Maternal sensitivity 54m 0.373 0.022 .000 0.331 0.416Maternal sensitivity 3rd 0.255 0.024 .000 0.208 0.301Maternal sensitivity 5th 0.190 0.029 .000 0.132 0.247

Male ¡

Prosocial behavior 3rd –0.329 0.043 .000 –0.412 –0.245Prosocial behavior 5th –0.043 0.055 .438 –0.151 0.065Prosocial behavior 6th –0.011 0.047 .817 –0.103 0.081Maternal sensitivity 54m –0.005 0.032 .863 –0.067 0.056Maternal sensitivity 3rd –0.117 0.030 .000 –0.175 –0.059Maternal sensitivity 5th 0.039 0.038 .296 –0.034 0.113

Note. CI � confidence interval; 54m � 54 months; 3rd to 6th � third grade to sixth grade. Standard root-meanresidual � 0.050; comparative fit index � 0.970; root-mean-square error of approximation � 0.045; 90% CI[0.038, 0.051].

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

6 NEWTON, LAIBLE, CARLO, STEELE, AND MCGINLEY

(Fabes & Eisenberg, 1998). The reasons for this are beyond thescope of this article, but it may well be that parenting—especiallymaternal socialization—contributes to differences in prosocial be-havior between the genders, as has been suggested in past research(Hastings et al., 2007). However, given the gender differences inprosocial behaviors (Eagly & Steffen, 1986), it is important to notethat the present findings may be partly due to the nurturant,emotional responsive orientation of most items used in the presentmeasure of prosocial behavior. Other measures that tap into riskyor instrumental forms of prosocial behavior may elicit a differentpattern of gender differences.

Several study characteristics limit the interpretation of the find-ings. First, although the NICHD SECC data set has the benefit ofobservational measures of parental behavior and multiple infor-mants of prosocial behavior, there were only two points in timewhere prosocial behavior and parental sensitivity were assessed inconsistent ways. This limited the models to a single bidirectionalpathway from third grade prosociality to fifth grade parental sen-sitivity. Additional equivalent measures of prosocial behaviors atearly ages and of parental sensitivity at later ages would have beendesirable. Second, using a cross-lagged, longitudinal model allowsfor the examination of the direction of effects, but future workshould incorporate interventions (see e.g., Schonert-Reichl, Smith,Zaidman-Zait, & Hertzman, 2012) and experimental methods tobetter infer causal relations. Third, the present study used struc-tured rather than unstructured tasks to measure sensitive parenting.

In past research, structured and unstructured tasks have eliciteddifferent parenting behaviors, especially related to parental control(Ginsburg, Grover, Cord, & Ialongo, 2006; Rubin, Cheah, & Fox,2001). It is possible that the structure of the tasks in the presentstudy may have influenced parents’ displays of sensitivity and itscomponents, and future research should examine bidirectionalrelations between parental sensitivity in unstructured interactionsand children’s prosocial behavior. Fourth, because maternal re-ports of children’s prosocial behavior were included in the latentconstruct of prosocial behavior, caution should be exercised wheninterpreting the results from the maternal model. It could be thatmothers who perceive their children as more prosocial are parent-ing in more sensitive ways. Unfortunately, paternal perceptions ofchildren’s prosocial behavior were not assessed in this study.Finally, the maternal and paternal models had different samplesizes, since many children did not have fathers participating in thestudy at all data collection waves. This, again, limits the conclu-sion that can be drawn about the models, since the maternal modelwas more diverse (with many single-parent households) and thestatistical power in this model was greater due to the increasedsample size. Future research should address these limitations byexamining larger samples of fathers as well as paternal perceptionsof prosocial behavior.

Despite these limitations, the present findings yield evidencethat bidirectional relations between prosocial behaviors and paren-tal sensitivity are evident by third grade in mother–child relation-ships but not in father–child relationships. These findings suggestexciting avenues for future research. In addition to the interventionand experimental method implications mentioned above, futureresearch designed to understand the lack of bidirectional relationsbetween fathers and children’s prosocial behaviors would be use-ful. As prosocial behavior tends to increase in consistency later inchildhood, it may have a stronger effect on parental sensitivity inboth mothers and fathers. In addition, parental sensitivity is just

Figure 4. Covariate influences for the paternal sensitivity model.SensD � paternal sensitivity; ProS � prosocial behavior; EdD � paternaleducation; k � kindergarten; Male indicates gender (1 � Male). Subscriptsindicate measurement occasion for all variables. Significant positive pathsare indicated with ���, significant negative paths are indicated with �-�, andsignificant paths are additionally represented with thicker lines. Squaresrepresent manifest variables, circles represent latent variables, single-headed arrows represent regressions, and dotted lines are included forreference to the full structural model specification.

Figure 3. Paternal sensitivity path model. SensD � paternal sensitivity;ProS � prosocial behavior; SP � supportive presence; RA � respect forautonomy; MR � mother report; TR � teacher report; u � manifestvariable uniqueness. Subscripts indicate measurement occasion for allvariables except uniquenesses. Significant paths are indicated with ���,significant structural paths are additionally represented with thicker lines.Squares represent manifest variables, circles represent latent variables,single-headed arrows represent regressions, and double-headed arrowsrepresent correlations.

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

7KIND CHILD, OR SENSITIVE PARENT?

one aspect of parenting that contributes to children’s social com-petence, as suggested by the modest to moderate effect sizes in thepresent study. Future research could also model the bidirectionalrelations between other types of prosocial behaviors and otheraspects of positive parenting in order to further the understandingof such relations. Finally, as children develop in middle childhood,their prosocial behavior may engender bidirectional patterns withpeers. The present study may be used as a basis for further workinvestigating how children’s peer relationships influence, and areinfluenced by, their prosocial behaviors.

In sum, the present study adds new complexity to the growingbody of literature on children’s prosociality. We asked aboutthe bidirectional relations between parental sensitivity andprosocial behavior. These findings show us the importance ofasking: Which parent’s sensitivity? Thus, when asking whethersensitive parenting fosters prosocial behavior or vice versa—the findings from this study suggest that both are mutuallyinfluential in mother– child relationships but that fathers’ sen-sitive behaviors seem less affected by their children’s prosoci-ality in middle childhood.

References

Barnett, M. A., Gustafsson, H. Deng, M., Mills-Koonce, W. R., & Cox, M.(2012). Bidirectional associations among sensitivity parenting, language

development, and social competence. Infant and Child Development, 21,374–393. doi:10.1002/icd.1750

Bell, R. Q. (1968). A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studiesof socialization. Psychological Review, 75, 81–95. doi:10.1037/h0025583

Biringen, Z., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (2012). Emotional availability: Concept,research, and window on developmental psychopathology. Developmentand Psychopathology, 24, 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000617

Brownell, C. A., Svetlova, M., Anderson, R., Nichols, S. R., & Drummond,J. (2013). Socialization of early prosocial behavior: Parents’ talk aboutemotions is associated with sharing and helping in toddlers. Infancy, 18,91–119. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00125.x

Cabrera, N., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bradley, R. H., Hofferth, S., & Lamb,M. E. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Develop-ment, 71, 127–136. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00126

Carlo, G., Mestre, M. V., Samper, P., Tur, A., & Armenta, B. E. (2011).The longitudinal relations among dimensions of parenting styles, sym-pathy, prosocial moral reasoning, and prosocial behaviors. InternationalJournal of Behavioral Development, 35, 116 –124. doi:10.1177/0165025410375921

Collins, W. A., & Russell, G. (1991). Mother-child and father-child rela-tionships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental anal-ysis. Developmental Review, 11, 99 –136. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(91)90004-8

Corwyn, R. F., & Bradley, R. H. (2002). Stability of maternal socioemo-tional investment in young children. Parenting, 2, 27–46. doi:10.1207/S15327922PAR0201_2

Table 3Paternal Sensitivity Model

Variable Estimate SE p

95% CI

Lower Upper

Structural regressionsPaternal sensitivity ¡ Prosocial behavior

54m ¡ 3rd 0.174 0.075 .020 0.027 0.3223rd ¡ 5th –0.087 0.119 .465 –0.321 0.1475th ¡ 6th –0.036 0.071 .615 –0.174 0.103

Prosocial behavior ¡ Paternal sensitivity3rd ¡ 5th 0.137 0.103 .181 –0.064 0.338

Prosocial behavior ¡ Prosocial behavior3rd ¡ 5th 0.931 0.179 .000 0.579 1.2835th ¡ 6th 0.795 0.093 .000 0.614 0.977

Paternal sensitivity ¡ Paternal sensitivity54m ¡ 3rd 0.356 0.054 .000 0.250 0.4613rd ¡ 5th 0.399 0.059 .000 0.282 0.515

CovariatesFather’s education ¡

Prosocial behavior 3rd 0.156 0.075 .038 0.009 0.304Prosocial behavior 5th –0.006 0.054 .907 –0.112 0.099Prosocial behavior 6th 0.031 0.025 .213 –0.018 0.081Paternal sensitivity 54m 0.233 0.035 .000 0.164 0.301Paternal sensitivity 3rd 0.183 0.031 .000 0.122 0.244Paternal sensitivity 5th 0.062 0.032 .051 0.000 0.125

Male ¡

Prosocial behavior 3rd –0.226 0.089 .011 –0.400 –0.052Prosocial behavior 5th –0.146 0.100 .147 –0.343 0.051Prosocial behavior 6th –0.055 0.075 .462 –0.202 0.092Paternal sensitivity 54m 0.003 0.051 .956 –0.097 0.102Paternal sensitivity 3rd –0.180 0.048 .000 –0.247 –0.087Paternal sensitivity 5th 0.096 0.051 .062 –0.005 0.196

Note. CI � confidence interval; 54m � 54 months; 3rd to 6th � third grade to sixth grade. Standard root-meanresidual � 0.039; comparative fit index � 0.990; root-mean-square error of approximation � 0.025; 90% CI[0.000, 0.039].

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

8 NEWTON, LAIBLE, CARLO, STEELE, AND MCGINLEY

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Untangling the links of parentalresponsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Devel-opment, 77, 44–58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x

Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1986). Gender and aggressive behavior: Ameta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychologi-cal Bulletin, 100, 309–330. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.100.3.309

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial develop-ment. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3,Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 646–718).Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Fabes, R. A., & Eisenberg, N. (1998). Meta-analysis of age and sexdifferences in children’s and adolescents’ prosocial behavior. Unpub-lished manuscript, Department of Family Resources & Human Devel-opment, Arizona State University.

Ginsburg, G. S., Grover, R. L., Cord, J. J., & Ialongo, N. (2006). Obser-vational measures of parenting in anxious and nonanxious mothers:Does type of task matter? Journal of Clinical Child and AdolescentPsychology, 35, 323–328. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_16

Grusec, J. E., Davidov, M., & Lundell, L. (2002). Prosocial and helpingbehavior. In P. K. Smith & C. H. Hart (Eds.), Blackwell handbook ofchildhood social development (pp. 457–474). Oxford, England: Black-well.

Hastings, P. D., McShane, K. E., Parker, R., & Ladha, F. (2007). Ready tomake nice: Parental socialization of young sons’ and daughters’ proso-cial behaviors with peers. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168, 177–200.doi:10.3200/GNTP.168.2.177-200

Hastings, P. D., Utendale, W. T., & Sullivan, C. (2007). The socializationof prosocial development. In J. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Thehandbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 638–664). NewYork, NY: Guilford Press.

Holden, G. W., & Miller, P. C. (1999). Enduring and different: A meta-analysis of the similarity in parents’ child rearing. Psychological Bulle-tin, 125, 223–254. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.223

Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariancestructure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. StructuralEquation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Joosen, K. J., Mesman, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzen-doorn, M. H. (2012). Maternal sensitivity to infants in various settingspredicts harsh discipline in toddlerhood. Attachment & Human Devel-opment, 14, 101–117. doi:10.1080/14616734.2012.661217

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation mod-eling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Knafo, A., & Plomin, R. (2006). Prosocial behavior from early to middlechildhood: Genetic and environmental influences on stability andchange. Developmental Psychology, 42, 771–786. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.771

Krevans, J., & Gibbs, J. C. (1996). Parents’ use of inductive discipline:Relations to children’s empathy and prosocial behavior. Child Develop-ment, 67, 3263–3277. doi:10.2307/1131778

Ladd, G. W., & Profilet, S. M. (1996). The Child Behavior Scale: Ateacher-report measures of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, andprosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1008–1024. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1008

Lamb, M. E. (2000). The history of research of father involvement: Anoverview. Marriage & Family Review, 29, 23– 42. doi:10.1300/J002v29n02_03

Lansford, J. E., Criss, M. M., Laird, R. D., Shaw, D. S., Pettit, G. S., Bates,J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Reciprocal relations between parents’

physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middlechildhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23,225–238. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000751

Martens, M. P. (2005). The use of structural equation modeling in coun-seling psychology research. Counseling Psychologist, 33, 269–298.doi:10.1177/0011000004272260

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010).Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.).Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2005). Child care and childdevelopment: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care andYouth Development. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Pardini, D. A., Fite, P. J., & Burke, J. D. (2008). Bidirectional associationsbetween parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from child-hood to adolescence: The moderating effect of age and African-American ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 647–662. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9162-z

Patterson, G. R. (1986). Performance models for antisocial boys. AmericanPsychologist, 41, 432–444. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.4.432

Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Relationships past, present, andfuture: Reflections on attachment in middle childhood. In K. A. Kerns &R. A. Richardson (Eds.), Attachment in middle childhood (pp. 255–282).New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rice, M. E., & Grusec, J. E. (1975). Saying and doing: Effects on observerperformance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 584–593. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.32.4.584

Richardson, R. R. (2005). Developmental contextual considerations ofparent-child attachment in later middle childhood years. In K. A. Kerns& R. A. Richardson (Eds.), Attachment in middle childhood (pp. 24–45). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rimehaug, T., Wallander, J., & Berg-Nielsen, T. S. (2011). Group andindividual stability of three parenting dimensions. Child and AdolescentPsychiatry and Mental Health, 5, 19.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions,relationships, and groups. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner(Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, andpersonality development (6th ed., pp. 571–645). New York, NY: Wiley.

Rubin, K. H., Cheah, C. S. L., & Fox, N. (2001). Emotion regulation,parenting and display of social reticence in preschoolers. Early Educa-tion and Development, 12, 97–115. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1201_6

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Smith, V., Zaidman-Zait, A., & Hertzman, C.(2012). Promoting children’s prosocial behavior in school: Impact of the“Roots of Empathy” program on the social and emotional competence ofschool-aged children. School Mental Health, 4(1), 1–21. doi:10.1007/s12310-011-9064-7

Vuchinich, S., Bank, L., & Patterson, G. R. (1992). Parenting, peers, andthe stability of antisocial behavior in preadolescent boys. DevelopmentalPsychology, 28, 510–521. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.3.510

Widaman, K. F., & Reise, S. P. (1997). Exploring the measurementinvariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substanceuse domain. In K. J. Bryant, M. Windle, & S. G. West (Eds.), Thescience of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and sub-stance abuse research (pp. 281–324). Washington, DC: American Psy-chological Association.

Received August 24, 2012Revision received January 14, 2014

Accepted February 7, 2014 �

Thi

sdo

cum

ent

isco

pyri

ghte

dby

the

Am

eric

anPs

ycho

logi

cal

Ass

ocia

tion

oron

eof

itsal

lied

publ

ishe

rs.

Thi

sar

ticle

isin

tend

edso

lely

for

the

pers

onal

use

ofth

ein

divi

dual

user

and

isno

tto

bedi

ssem

inat

edbr

oadl

y.

9KIND CHILD, OR SENSITIVE PARENT?