Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients

Depression, Anxiety, and SocialDisability Show Synchrony of Changein Primary Care Patients

Johan Onnel, PhD, Michael Von Korff, ScD, Wim Van Den Brink, MD,Wayne Katon, MD, Els Brilman, MA, and Tineke Oldehinkel, MA

IntroductionRecent studies have shown that de-

pression in primary care patients is com-mon and often is not self-limiting or tran-sient; that most cases in the community areseen by general practitioners; and that rel-atively few patients are referred to mentalhealth specialists.1-'5 Other studies haveshown a clinically significant association ofdepression with social disability. 1U-30 Thereis evidence that the associated disabilitycan be rather persistent.17 Because per-sonal, clinical, social, and economic costsare involved,'6"17'31 it is important to un-derstand what disability is associated withcommon psychiatric illness and whethersymptom and disability levels follow par-allel trajectories over time.

To date, few studies have examinedthe longitudinal relationship between de-pression and disability. In a 1-year fol-low-up study of 185 distressed health main-tenance organization enrollees in the topdecile of users of ambulatory health care, itwas found that a reduction in depressionlevels was accompanied by a reduction indisability days of approximately 50%. 18

However, the generalizability of these find-ings is unclear, owing to the selective na-ture of the sample (in which there was ahigh prevalence of comorbidity of physicalillness and depression) and the exclusivereliance on self-report measures. The latterfactor may have caused information biasthrough the overly negative response set ofpatients with depressive symptoms.32'33 Inaddition, previous research has not exam-ined the relationship of specific diagnosticcategories (e.g., anxiety, depression) to

disability.In the context of the triad of impair-

ment, disability, and handicap, disabilityis typically defined as "any restriction or

lack of capacity to perform an activity in a

manner or within a range considered nor-mal for a human being."34 35 In the presentstudy, disability was conceptualized as arestriction or lack of capacity to performactivities and/or manifest behaviors as ex-pected in four well-defined social roles:self-care, family role, social role, and oc-cupational role. Self-care refers to howone takes care of oneself and presentsoneself to others in everyday encounters.Family role function is evaluated in termsof participation in and preservation of thehousehold as an independent unit. Socialrole refers to quantity and quality of con-tacts with others, excluding family mem-bers and professional colleagues. Occupa-tional role concems adherence to dailyroutine, performance, and relationshipswith colleagues at work (for people ingainful employment, volunteer work, orhousekeeping); in activities directed at se-curing a job (for people about to graduateor unemployed); or in daily activities (incase of retirement or long-term unemploy-ment). Consequently, our conceptualiza-tion of disability is more social and general

Johan Ormel, Wim Van Den Brink, Els Bril-man, and Tineke Oldehinkel are with the De-partment of Psychiatry, University of Gronin-gen, Groningen, The Netherlands. JohanOrmel is also with the Department of HealthSciences at the University of Groningen.Michael Von Korff is with the Center for HealthStudies, Group Health Cooperative of PugetSound, Seattle, Wash. Wayne Katon is with theDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sci-ence, University of Washington, Seattle.

Requests for reprints should be sent toJohan Ormel, PhD, Department of Psychiatry,University of Groningen, Oostersingel 59, 9713EZ Groningen, The Netherlands.

This paper was submitted to the JournalDecember 30, 1991, and accepted with revi-sions October 22, 1992.

Editor's Note. See related commentary byFogel (p 319) in this issue.

American Journal of Public Health 385

-ee ..............

.v .X'11;

Ormd et al.

than the usual approach in terms of instru-mental activities of daily living and dis-ability days.

The present study had three objec-tives: (1) to characterize disability associ-ated with common psychiatric illnesses;(2) to test whether severity of psychiatricillness and disability show synchrony ofchange, while controlling for physical ill-ness; and (3) to establish how invariantthis longitudinal relationship is acrossbaseline severity, recency of onset, andpsychiatric diagnosis.

MethodsThe study was carried out in the

province of Groningen, The Netherlands,during the late 1980s.8,19,36-38

SubjectsSampling ofprimary care patients oc-

curred in a two-stage design. In stage 1,2237persons aged 16 to 65 yearswhowerepatients of 25 general practitioners (GPs)were approached for screening with the30-item General Health Questionnaire(GHQ)39(40 and rated by their physician oncurrent mental health status. Of the 1994persons who agreed to participate, 43%were positive according to the question-naire (GHQ+) and 28% were positive ac-cording to the general practitioner (GP+)."Positive" was defined as having a scoreof 5 or higher on the questionnaire or hav-ing a current mental health problem de-tected by the general practitioner. The 25general practitioners were a representa-tive sample from the total population ofgeneral practitioners in the city of Gron-ingen and some surrounding towns (totalpopulation 275 000; number of generalpractitioners approximately 110). Thephysicians also indicated whether the pa-tient had had a mental health problem inthe year preceding the index visit. If thiswas the case the patient was designated"old"; if not, the patient was considered"new."1

Persons selected for baseline exami-nation at stage 2 were a stratified randomsample, with differing probabilities de-pending on physician rating (GP+/GP-),questionnaire status (GHQ+/GHQ-),and "old" or "new" status. Because themain study objective was the long-termoutcome of "new" cases of psychiatricillness detected or undetected by generalpractitioners, the following samplingscheme was used: all "new" detected(GP+) patients (n = 206); a random sam-ple (n = 91) from the 397 "new" unde-tected (GP-/GHQ+) patients; a random

sample (n = 62) from the 847 "new"GP-/GHQ- patients; and a random sam-ple (n = 42) from the 221 "old" GP+/GHQ+ patients. Of this total of 401, 285were flJly examined at baseline (105 re-fused the baseline interview and 11 hadimportant missing data).

According to the Present State Ex-amination4l (see below), 91 of the 285completely examined baseline subjectshad less than three psychiatric symptoms.These "asymptomatic" patients, desig-nated "normal" patients, were excludedfrom follow-up at 1 year (T2) and 3.5 years(T3) post index visit. Because of attritionand missing data, complete longitudinaldata were obtained on 143 of the 194 pa-tients eligible for follow-up.

MeasuresAt Ti (the baseline interview, which

took place 1 to 2 weeks after the indexvisit), T2, and T3, the Present State Ex-amination (PSE)41 and the Groningen So-cial Disability Schedule (GSDS)4243 wereadministered, primarily by clinical psy-chologists. The time frame for both instru-ments was the 4 weeks preceding the in-terview.

The Present State Examination is astandardized semistructured interviewcovering 140 psychiatric symptoms. Datafrom the examination were used to assigndiagnoses and to construct a sum score ofnonpsychotic symptoms (PSE-TOT) thattook into account the severity of symp-toms. Interviewer-observer reliability onthe Present State Examination items usedhas generally been good: kappa valuesrange from .38 to .81, with a mean of .61.?6

The Groningen Social DisabilitySchedule42'43 is a standardized semistruc-tured interview focusing on self-care, fam-ily role, social role, and occupational role,each comprising various dimensions.Scores on each dimension and role rangefrom 0 (no disability) through 1 (mild dis-ability) and 2 (moderate disability) to 3 (se-vere disability). For each dimension, theseverity categories have been descnbed inbehavioral terms.42.43 By asking standard-ized questions from the schedule andprobing, the interviewer collected factualdata and made the dimensional and roleratings. The criteria used to evaluate func-tion applied to the reference group ofhealthy people of the same sex, age, andprofession. Interviewer-observer reliabil-ity on the Groningen Social DisabilitySchedule has been shown to be good in a

variety of populations, with weightedkappa values for different social rolesranging from .63 to .93.42,43 Because

symptom and disability data were col-lected by the same interviewer, many rat-ingswere checked independentlybya sec-ond rater (typically another interviewer orproject staff member), using the writtenreport of the interviewer, and discussed.

Analyses have shown that the fourroles measured by the Groningen SocialDisability Schedule constitute a one-di-mensional hierarchical scale, suggestingthat a simple sum score (GSDS-TOT) canbe meaninlly applied."

The presence ofphysical illness in the4 weeks preceding the interview was glo-bally assessed at baseline and atT2 andT3by means of a Present State Examinationitem. This item asked the interviewer torate physical illness according to the fol-lowing categories: 0 (no physical illness);1 (minor physical illness, e.g., commoncold, stiff neck, cough); 2 (mild to moder-ate physical illness, e.g., mild duodenalulcer, uncomplicated diabetes mellitus); 3(serious physical illness, e.g., carcinoma,severe arthritis).

Diagnostic ClassificafionPsychiatric diagnoses were made ac-

cording to the Bedford College criteria de-veloped to differentiate the spectrum ofcommon psychiatric illnesses in the com-munity and among primary care pa-tients.45 The following categories are dis-tinguished: depression, anxiety, andminor psychiatric disorder (which in-cludes minor depression and minor anxi-ety). The criteria are described in theAppendix. An additional category, non-specific psychiatric distress, was con-structed for persons without a BedfordCollege diagnosis who had at least threenonspecific psychiatric symptoms (e.g.,worrying, tension pains, muscular ten-sion, tiredness, restlessness, hypochon-driasis, irritability, poor concentration).Mixed anxiety/depression refers to co-morbidity of anxiety and depression. Inaddition, major psychiatric disorder in-cludes anxiety or depression or both, withor without a minor disorder.

Recency ofonset refers to the time ofonset of psychiatric symptoms present atthe time of the index visit. Time of onsetwas established by the interviewer duringa short semistructured interview. Re-cency of onset was classified as recent(onset of less than 12 months prior to theindex visit) or remote (onset of more than12 months prior to index visit; this cate-gory also included persons whose remote-onset symptoms had recently been exac-

erbated). Recency of onset was assessedbecause the "new" GP+ and/or GHQ+

March 1993, Vol. 83, No. 3386 American Journal of Public Health

Depression, Anxiety, and Social DiabiHly

cases were not necessarily recent (or in-cident) cases because the symptoms maynot have been presented by the patient ordetected by the general practitioners in theyear prior to the index visit. Reliabilitydata are not available.

Symptom Improvement by BaselineSeverity

A study subject was classified as im-proved if the mean of the two follow-upPSE-TOTs was reduced by at least 50%relative to his or her baseline PSE-TOT.Next, subjects were cross-classified bybaseline severity (minor and nonspecificvs major) and improvement status (im-proved, unimproved) in four severity-improvement groups.

AnaysisRepeated-measures general linear

models analysis was performed with SASsoftware46 to assess longitudinal differ-ences in disability levels by severity-improvement status, with physical illnesscontrolled for. A nonproportionally strat-ified sampling scheme was used; there-fore, statistical tests should be interpretedcautiously. Because weighting did not af-fect the pattern of findings, unweighteddata are presented.

ResultsCross-Sectional Findings

Table 1 depicts the sociodemo-graphic characteristics of normal patients(PSE-TOT < 3) and patients with three ormore psychiatric symptoms (case pa-tients, classified by recency of onset).Larger numbers of women were foundamong case patients than among normalpatients (Wald's test, P < .02), in con-formance with other reports.113'47 Noclear association of mean age and educa-tional attainment with case status was ob-served. Recent-onset case patients werelikely to be younger (t test, P < .01) andbetter educated than remote-onset casepatients (Wald's test, P = .03).

Table 2 presents mean psychopathol-ogy (PSE-TOT) and disability (GSDS-TOT) scores, as well as the percentage ofpatients with at least minor impairment inthe four roles. Case patients differedstrongly from normal patients in terms ofoverall as well as role-specific disability.Impaired social and occupational rolefunctioning contnbuted most to the over-all level of disability; self-care and familyroles were typically intact. Severity of

psychiatric illness (PSE-TOT) correlatedsubstantially with level of disability (Pear-son r = .48).

Table 2 also presents the percentageof patients with at least mild physical ill-ness. Compared with recent-onset casepatients, remote-onset case patients weremore likely to have at least mild physicalillness (Wald's test, P < .06) and lesslikely to have disability (t test, P = .09).The two groups did not differ significantlyin terms of severity ofpsychiatric illness (ttest, P < .41).

Presence of at least mild physical ill-ness at baseline was not associated withseverity of psychiatric illness (t test,P < .11). Level of disability was slightlyhigher among patients with at least mildphysical illness, but was not statisticallysignificant. These observations were rep-licated at follow-ups.

Table 3 presents mean disabilityscores by diagnostic category. Althoughdepressive illness was associated withhigher disability thanwere anxiety and mi-nor psychiatric disorders (t test,P < .01),the disability associatedwith the latter twodid not differ significantly from the levelobserved in the nonspecific distressgroup. Similar trends were observed forthe role scores. These findings suggestthat depression (with or without anxiety)in particular is associated with disability.

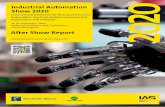

Longitdinal FindingsFigure 1 depicts the course of disabil-

ity for each of four severity-improvementgroups: (1) major psychiatric disorder (de-pression and/or anxiety) at baseline andnot improved; (2) major psychiatric disor-der at baseline and improved; (3) minorpsychiatric disorder or nonspecific dis-tress at baseline and not improved; and (4)minor psychiatric disorder or nonspecificdistress atbaseline and improved. Personswith improved symptoms had substan-

tially lower levels of disability at follow-up, whereas persons with unimprovedsymptoms had disability levels that wereonly slightly lower than their baseline lev-els. At follow-up, disability among per-sons with improved symptoms dropped tothe level found among the asymptomatic(normal) patients at baseline.

In the repeated-measures general lin-ear models analysis for the three occa-sions on which disability was measured,baseline severity of psychiatric illness andimprovement statuswere entered as factorsand severity of physical iliness was con-trolled for. The analysis indicated a highlysignificant interaction between time and im-provement status (F = 50.1, P < .001).This interaction confirmed the hypothesisthat patients with improved psychiatricsymptoms and patients with unimprovedpsychiatric symptoms would have differ-ent trajectories of disability. We repeatedthe analysis to establish whether the pat-tern of results was similar for diagnosticcategory (depression, anxiety, mixedanxiety/depression) and for recency ofon-set (recent onset, remote onset). Thesestratified analyses showed that the syn-chrony ofchange in symptom severityanddisability was independent of diagnosticcategory and recency of onset (graphs notpresented).

BiscussionThe major finding of this study was

that common psychiatric illnesses in pri-mary care were associated with disability,both cross-sectionally and longitudinally.The cross-sectional findings showed thatmost disability consisted of impaired so-cial and occupational role function andthat greater disability was found amongpatientswith depression than among thosewith anxiety. In general, the more severe

the psychiatric illness was in terms of

American Journal of Public Health 387March 1993, Vol. 83, No. 3

number and severity of symptoms, thehigher the level of disability. These obser-vations are in line with earlier work withcommunity samples and psychiatric out-patients.2225 At the index visit, disabilitylevels among patients with major depres-sion and mixed anxiety/depression weresimilar to disability levels found in Dutchpsychiatric outpatients."t

The longitudinal analysis demon-strated that primary care patients whosepsychiatric symptoms substantially im-proved showed corresponding changes indisability level, whereas patients with un-improved or only slightly improved symp-toms showed, on average, no improve-ment in disability level. This patternappeared to be invariant across the diag-nostic categories of depressive illness,anxiety, and mixed anxiety/depression.The disability level of improved patientshad returned at follow-up to approxi-mately the same level found among thenormal patients at baseline. The longitu-dinal results strengthen and extend thefindings of the only other longitudinalstudy in primary care, that conducted inSeattle byVon Korffet al18 The similarity

March 1993, Vol. 83, No. 3388 American Journal of Public Health

Onnel et al.

2.4-

2.2 - - MAJOR DISORDER/NOT IMPROVED

2~~~|>1.8

og1.6 3MAJOR DISORDER/IMPROVED-1.6

a 12MINOR+NON-SPECIFIC/NOT IMPROVED

080L: 0.6-

0.4-

0.2- MINOR + NON-SPECIFIC/IMPROVED

0 Baseline 1-Year 3.5-Year(TI) Follow-up (T2) Follow-up (T3)

Measurement Wave

FIGURE 1-Synchrony ofchange In psychopatholgyand disability, stratified by base-line (TI) symptom severity.

I

I-1

of findings is striking, considering the sub-stantial differences between the Seattleand Groningen studies in sample, design,time frame, and measures.

Our results suggest that the cross-sectional and longitudinal association be-tween severity of psychiatric illness anddisability level was largely independent oftime of onset of the symptoms. As ex-pected, the remote-onset case patientstended to be older, to be more likely tohave comorbidity of mild physical illness,and to have lower levels of disability thandid recent-onset case patients. These pat-terns, however, did not affect the relation-ship between psychiatric illness and dis-ability.

Disability in this study was concep-tualized and measured in terms of dys-function in four social roles (self-care,family role, social role, and occupationalrole). Although disability in these rolesmay be due to physical as well as psychi-atric illness, the underlying mechanismsmay differ somewhat. Physical illnessmayproduce disability because of limitationsin physical capacities such as mobility, vi-sion, aerobic capacity, and strength,whereas psychiatric illness may producedisability through limitations in cognitive,motivational, and emotional capacitiesand the tendency to experience multipleminor physical symptoms49 (e.g., fatigueand pain).

Our diagnosis-specific findingsshould be interpreted cautiously. Al-though we were able to follow up a rea-sonable number ofpatientswith major andminor depression, minor anxiety, andnonspecific psychiatric distress, the smallnumber of major anxiety cases rendersconclusions about this category highlytentative.

Only a minority of our second-stagesample (15%) had mild to serious physicalillness. The low severity ofphysical illnessin this sample may explain the lack of arelationship between physical illness anddisability ratings. The global and crudemeasurement of physical illness by a sin-gle item may also have been a factor; lim-itations in physical capacities were not as-sessed. At the same time, the lack of asignificant association between physicalillness and disability may be due to thepossibility that disability in role function isless sensitive to mild physical illness thanto psychiatric illness. It may be easier toperform the selected roles with mild tomoderate limitations in physical capaci-ties than with psychiatric illness that im-pairs the highest-order capacities of thehuman organism.

March 1993, Vol. 83, No. 3

It should be stressed that our studysample is not fully representative of con-secutive patients with psychiatric illnessin primary care. "New" cases were sam-pledwith higher probabilities. However, itis unlikely that the sampling scheme seri-ously biased the results. Many "new"cases had onsets ofmore than 1 year priorto the index visit but were rated by thephysician as "new" because the patienthad not presented the psychiatric illness inthe previous year or because the illnesswas not detected by the physician at anearlier visit. Substantial differences in therelationship of psychiatric illness to dis-ability were not found between recent-onset and remote-onset case patients.

Another question iswhether our find-ings can be generalized to the community.We selected the primary care setting be-cause it is the setting where most psychi-atric illness is presented and managed.'5At least two thirds of community patientswith nontransient psychiatric illness con-sult their general practitioners and only afew are referred. There may be, however,a considerable time lag between onset andconsultation,50 and psychiatric illness isoften presented in a somatic idiom.8,36,39

Our longitudinal data on psychiatricillness and disability show synchrony ofchange but not how and why this syn-chrony occurs. Because dates of onsetand remission of disability were not as-sessed, causal ordering cannot be deter-mined. There are arguments that psychi-atric illness may be secondary todisability, with social stress resulting fromdisability as the etiologic mechanism.21More plausible is the hypothesis that de-pression and disability are mutually rein-forcing mechanisms, with initial psychiat-ric distress leading to impairment in theoccupational and social roles, in turn re-ducing social reinforcement and self-es-teem and further exacerbating psycholog-ical distress.

An important question is what can bedone in primary care for those patientswho suffer from persistent psychiatric ill-ness and associated disability. Althoughsome work on this question has alreadybeen done,e-g 49,51,52 there is a strong needfor clinical trials in primary care settings inwhich pharmacological and psychosocialinterventions are evaluated with respectto their abilities to improve functional sta-

tus. Such studies should also provide dataon temporal relationships between symp-tomatology and disability. Our examiiner-based, three-wave data covering a periodof 3.5 years strongly suggest that success-

Depression, Anxiety, and Social Disabity

ful treatment of psychiatric illness bringsabout a reduction of disability in role func-tion. E

AcknowledgmentsThis research was supported by the MedicalFoundation of the Dutch Organization for Sci-entific Research (NWO), grants 900-556-002and 900-556-050, and the Prevention Fund,grant 28-1209. Some ofthe analyses andwritingwere perfonned when Dr. Ormel was a visitingscholar at the Center for Health Studies, GroupHealth Cooperative of Puget Sound, and theDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sci-ence at the University of Washington, Seattle,Wash.

References1. Blacker CVR, Clare AW. Depressive dis-

order in primary care. Br J Psychiatry.1987;150:737-751.

2. Mann AH, Jenkins R, Belsey E. Thetwelve-month outcome of patients withneurotic illness in general practice. PsycholMed. 1981;11:535-550.

3. SchulbergHC, McCleliandM, GoodingW.Six-month outcomes for medical patientswith major depressive disorders.J Gen In-tern Med. 1987;2:312-317.

4. Regier DA, Burke JD, Manderscheid RW,Burns BJ. The chronically mentally ill inprimary care. Psychol Med. 1985;15:265-273.

5. Cooper B, Fry J, Kalton GW. A longitu-dinal study of psychiatric morbidity in ageneral practice population. BrJPrev SocMed. 1969;23:210-217.

6. Hankin JR, Locke BZ. The persistence ofdepressive symptomatology among pre-paid group practice enrollees: an explor-atory study.Am JPublic Health. 1982;29:2-10.

7. Shepherd M, Cooper B, Brown AC, Kal-ton GW. Psychiatric Illness in GeneralPractice. London, England: Oxford Uni-versity Press; 1966.

8. Ormel J, BrinkWVan Den, Koeter MWJ,et al. Recognition, management and out-come ofpsychological disorders in primarycare: a naturalistic follow-up study. Psy-chol Med. 1990;20:909-923.

9. Von Korff M, Shapiro S, Burke JD, et al.Anxiety and depression in a primary careclinic: comparison of DIS, GHQ and prac-titioner assessments.Arch Gen Psychiatry.1987;44:152-156.

10. Barrett JE, Barrett JA, Oxman TE, GerberPD. The prevalence of psychiatric disor-ders in a primary care practice. Arch GenPsychiatry. 1988;45:1100-1119.

11. Hoeper EW, Nycz GR, Cleary PD, RegierDA, Goldberg ID. Estimated prevalence ofRDC mental disorder in primary medicalcare. Int J Ment Health. 1979;8:6-15.

12. MurphyJM, Olivier DC, Sobol M, MonsonRR, LeightonAH. Diagnosis and outcome:depression and anxiety in a general popu-lation. Psychol Med. 1986;16:117-126.

13. HankinJR,OktayJS.MentalDlsorderandPrima)y Medical Care: An Anaytic Re-view of the Literature. Washington, DC:US Dept of Health, Education, and Wel-

American Journal of Public Health 389

Ornel et al.

fare; 1979. National Institute of MentalHealth Series D5, publication ADM 78-661.

14. Kessler LG, Cleary PD, Burke JD. Psychi-atric disorders in primary care: results of afollow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1985;42:583-587.

15. Giel R, Koeter MWJ, Ormel J. Detectionand referral of primary care patients withmental health problems: the second andthird filter. In: Goldberg D, Tantam D, eds.The Public Health Impact of Mental Ill-ness. Bern, Switzerland: Hans Huber AG;1990.

16. Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnham MA.Psychiatric disorder in a sample of the gen-eral population with and without chronicmedical illness.AmJPsychiatry. 1988;145:976-981.

17. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK,Kit Tse C. Depression, disability days, anddays lost from work in a prospective epi-demiologic survey.JAMA. 1990;264:2524-2528.

18. Von KorffM, OrmelJ, Katon W, LinEHB.Disability and depression among high utiliz-ers of health care: a longitudinal analysis.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:91-100.

19. Wohlfarth TD, BrinkWVan Den, Ormel J,Koeter MWJ, Oldehinkel TJ. The relation-ship between social dysfunctioning and psy-chopathology. BrJPsychiatry. In press.

20. Berkman LF, Berkman CS, Kasl S, et al.Depressive symptoms in relation to phys-ical health and functioning in the elderly.Am JEpidemiol. 1986;124:372-388.

21. Turner RJ, BeiserM. Majordepression anddepressive symptomatology among thephysically disabled: assessing the role ofchronic stress. JNerv MentDis. 1990;178:343-350.

22. Hurry J, Sturt E. Social performance in apopulation sample: relations to psychiatricsymptoms. In: Wing JK, Bebbington P,Robins LN, eds. What is a case? London,England: Grant McIntyre; 1981.

23. Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, LinkB, Levav I. Social functioning of psychiat-ric patients in contrast with communitycases in the general population. Arch GenPsychiatry. 1983;40:1174-1182.

24. Casey PR, Tyrer PJ, Platt S. The relation-ship between social functioning and psy-chiatric symptomatology in primary care.Soc Psychiatry. 1985;20:5-9.

25. Hecht H, Zerssen D, Wittchen HU. Anx-iety and depression in a community sam-ple: the influence of comorbidity on socialfunctioning. J Affective Disord 1990;18:137-144.

26. Rodin G, Voshart K. Depression in themedically ill: an overview.Am J Psychia-try. 1986;143:696-705.

27. Craig TJ, Van Natta PA. Disability and de-pressive symptoms in two communities.Am IPsychiatry. 1983;140:598-601.

28. Blumenthal MD, Dielman TE. Depressivesymptomatology and role function in a gen-eral population. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1975;32:985-991.

390 American Journal of Public Health

29. Paykel ES, Weissmann MM. Social adjust-ment and depression. Arch Gen Psychia-try. 1973;28:659-663.

30. Hecht H, Zerssen D, Krieg C, Possl J, Wit-tchen HU. Anxiety and depression: co-morbidity, psychopathology, and socialfunctioning. Conipr Psychiatry. 1989;30:420-433.

31. Stoudemire A, Frank R, Hedemark N, Ka-mlet M, Blazer D. The economic burden ofdepression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1986;8:387-394.

32. Watson D, Pennebaker JW. Health com-plaints, stress, and distress: exploring thecentral role of negative negativity. PsycholRev. 1989;96:234-254.

33. Ormel J, Wohlfart T. How neuroticism,long-term difficulties, and life situationchange influence psychological distress: alongitudinal model. J Pers Soc PsychoL1991;60:744-755.

34. International Classification of Impair-ments, Disabilities and Handicaps.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Orga-nization; 1980.

35. Susser M. Disease, illness, sickness; im-pairment, disability and handicap. PsycholMed 1990;20:471-473. Editorial.

36. Wilmink FW. Patien; Physician, Psychi-atstt:Assessment ofMental Health Prob-lems in Pri*nary Care. Groningen, TheNetherlands: University of Groningen;1989. PhD thesis.

37. Ormel J, Koeter MWJ, BrinkWVan Den,Willige G Van De. Recognition, manage-ment and course of anxety and depressionin general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatty.1991;48:700-706.

38. Brink W Van Den, Leenstra A, Ormel J,Willige G Van De. Mental health interven-tion programs in primary care: their scien-tific basis.JAffectiveDisord 1991;21:273-284.

39. Goldberg DP. Detection and assessment ofemotional disorders in primary care. IntJMent Health. 1979;8:30-48.

40. KoeterMWJ, Ormel J. Handleidingvan deNederiandse versie van de General HealthQuestionnaire. Lisse, The Netherlands:Swets & Zeitlinger; 1991.

41. Wing JK, Cooper J, Sartorius N. The mea-surement and classification of psychiatricsymptoms. Cambridge, Mass: CambridgeUniversity Press; 1974.

42. Wiersma D, DeJong A, Ormel J,Kraaykamp HJM. Groningen Social Dis-ability Schedule and Manual. 2nd ed.Groningen, The Netherlands: UniversityofGroningen, Department of Psychiatry;1990.

43. Wiersma D, DeJongA, Ormel J. The Gron-ingen Social Disability Schedule: develop-ment, relationship with ICIDH, and psy-chometric properties. Int J Rehab Res.1988;11:213-224.

44. DeJongA, Molenaar IW. An application ofMokken's model for stochastic cumulativescaling in psychiatric research. JPsychiatrRes. 1987;21:137-149.

45. Finlay-Jones R, Brown GW, Duncan-Jones P, Harris T, Murphy E, Prudo R.Depression and anxiety in the community:replicating the diagnosis of a case. PsycholMed. 1980;10:445-454.

46. SAS User's Guidee: Statistics, Version 5.Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1985.

47. Marks JN, Goldberg D, Hillier VF. Deter-minants of the ability of general practitio-ners to detect psychiatric illness. PsycholMed. 1979;9:337-353.

48. Staal JL, Ormel J, Schoenmacker J, et al.Het beloop van psychopathologie en so-ciale beperkingen. Tijdschr Soc Gezond-heidszorg. 1989;67:1-4.

49. Katon W, Sullivan M. Depression andchronic medical illness. J Clin Psychiatty.1990;51:3-11.

50. Ormel J, Brook GFG, Wiersma D. De-pressie, de behandelde en onbehandeldemorbiditeit in de (Nederlandse) bevolking.Tijdschr Soc Gezondheidszorg. 1984;17:670-678.

51. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T,Ormel J. Adequacy and duration of antide-pressant treatment in primary care. GenHosp Psychiatry. 1992;30:67-76.

52. Paykel ES, Freeling P, Hollyman JA. Aretricyclic antidepressants useful for mild de-pression? A placebo controlled trial. Phar-macopsychiatry. 1988;21:15-18.

uedtnoodaud4or butnmpsarepresetixatwouldpet-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.................moreofthefollowing 10 symptoms: hope~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~...... m. t a.iansi.f.er.s.nor.nl as..lesanss, uicidl. idas o ...onsw .....ght........a....hs atg ryn ud smie

loss, earlywakening~~~~~~~~ delayed sleep, poor (depressed nxxd~~~~~.........da ...ea.5t..loc...e. traion..e.e.......tb..od lo.s.the.1sy pt..lite.fr.ep e .io). nofinterest, se........... .....o... and........i.. m n rs ssy hc sd fn d a 1 re

ty..le a..........an...tym.rtha......hetie.ormo..hetie,...lssthn.iv.pniatac.,othanfive -attacks;or (2) fme-floating (3) situational antononiicamdetyandavoid-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~............autoraunicanxietylessthan5G% of the titne anon whenever possible.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.. ........

endonetofourpanic attacks or (3) sitna- N~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~n~~ In theorig~~~~~........Bedford....Collegetionalautonomican,detynndmarkod#ener-tion, the term"borderline"isused~~~~~~~~~~~~~...................alization of ..idnc. instead...of...........We ..p..fer t use.... .iwe..hted ..s......... ..aeE~ o ep o ..or.....i.. per.... ality..disorder..

am atio snati.. y......y .... .........

.. .....March..1993,.Vol..83,.No..3