Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles THE REPUBLIC ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles THE REPUBLIC ...

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO.

All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy.

© FAO 2009

3

CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 5Economicactivities 8Majorcrops 8Fisheries 9Forestry 9Animalproduction 9Mineralresources 10

2. SOILS AND TOPOGRAPHY 10Soils 10Topography 10

3. CLIMATE AND AGRO-ECOLOGICAL ZONES 11Climate 11Azonalrainfall 12ClassificationofBeninoisclimates 12Vegetation(agro-ecologicalzones) 13Hydrographicnetwork 17

4. RUMINANT LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMS 18Sedentaryproductionsystems 19Migratorylivestockrearing 20Somecattlebreeds 20Smallruminants 22

5. THE PASTURE RESOURCE 25Naturalpasture 25Cultivatedforages 26Grasses 27Covercrops 28Cropresidues 29

6. OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVEMENT OF PASTURE RESOURCES 30Forageresourcedevelopment 30Plantingleguminousandfoddertrees 30Developmentoffallowvegetationinrelationtolanduseintensity 30Constraints:threatsandsolutions 31

7. RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS AND PERSONNEL 32

8. REFERENCES 33

9. CONTACTS 35

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 5

1. INTRODUCTION

ThepresentRepublicofBeninwasthepowerfulKingdomof Dahomey, once known as the Slave Coast becauseof trafficking from there to theAmericas. It became aFrenchColony in the late1800s,gaining independencein 1960. The country’s current name was adopted inNovember1975.

Benin borders Niger to the north, Burkina Faso tothenorthwest,Nigeriatotheeast,TogotothewestandtheGulfofGuineatothesouth(seeFigures1aand1b).Beninextends from theNigerRiver in thenorth to theAtlanticOcean in the south, a distance of 700 km. Itscoastlinemeasures121km;thecountryisabout325kmatitswidestpoint.Benin’slatituderangesfrom6°30′Nto12°30′Nanditslongitudefrom1°Eto3°40′Ewithanareaof112622km2.ThehighestpointisMt.Sokbaro658mwhile the lowestpoint is theAtlanticOceansealevel.

Beninhasapopulationof7862944(8791832[July2009 est.]with a 2.977%growth rate according to theWorld Factbook). In 2006 GDP was USD5.92 billion;GDP growth rate, 4.2% and per capita GDP wasUSD749(CIA–WorldFactbookProfile,1993;2007).

Themajor citieswith their population estimates are;Cotonou533000,PortoNovo317000,Djougou132000,AbomeyCalavi126000,Parakou107000 (1992).Thecapital City is Porto-Novo. Benin land use consists of:31% forests; pastures 4%; agricultural-cultivated land17%, and other 48% (CIA – World Factbook Profile,1993;2006).PilotAnalysisofGlobalEcosystems(PAGE)calculationsbasedonGlobalLandCoverCharacteristicsDatabase(GLCCD)(1998)indicatedthatBeninRepublichas93.1%grasslandarea,makingitthecountrywiththehighestgrasslandareainsub-SaharanAfrica.

The land area covered by vegetation represents anarea of 11 million ha. This is distributed as follows:25% (2 750 000 ha) is in afforested zones; 23.5%(2 585 000 ha) is arable land; 8% (880 000 ha) is inpermanentcrops;4%(440000ha)ispermanentpasture;while 39.5% (4 345 000 ha) is for other uses (open/fragmented land and other land cover). In 2006, 20%(2 200 000 ha) was cropped and of the cropped land25%(550000ha)wasusedasthegrazingzoneforlargeherds of cattle. This, however, excludes 45% reservedforestsoccupyingasurfaceareaof1375000haofwhich14000haareteakplantations.Oftheavailablehectaresofarableland,2200000haweredevelopedin2006.

ThelowfarmingrateinBeninisattributedto:• lowmechanizationofagriculturecoupledwithan

almosttotalabsenceoflargefarms;• lackofmarketoutletsforfarmproduceatcompeti-

tiveprices;and

Figure 1a. Map of the Benin RepublicSource: World Factbook

Figure 1b. Political map of the Benin RepublicSource: World Atlas.com Inc

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile6

• the land tenure system,whichuntil recentlywasbasedoncustomaryrights.

Ingeneral,verylittlelandisoccupiedinallofBenin.Yet,thereareveryfertileareassuchas theNigerValley, reputed tobe themostfertileaftertheNileValley.

Theprincipal foodcropsaremaize,cassava, sorghum,yams,millet and beans. Important cash crops, produced mainly inthe south, include cotton, cocoa, coffee, groundnuts and palmkernels. The herding of cattle, sheep, and goats predominatesin the grasslands of the north.An exploding population (3.3%population growth or 2.977% according to theWorld Factbookisputtingpressureon forests for firewood,agriculturalclearing,pasturelandsandhousing(CIA–WorldFactbookProfile,2006).Table1showsoutputofsomemajorstaplefoodandexportcropsfrom1998to2007.

Palm oil was a major cash crop in Benin during the 1980s,but its cultivationwasmarginalizedby thepopularityof cotton,theonlycashcropsuitedtosmall-scalefarmers,makingup40%of the country’s GDP and over 80% of export revenues. Thecountry’s fertile land has suffered environmental degradation asa resultof theemphasisonproductionofcotton forexport,andbecause90%ofallpesticidesareusedoncotton.

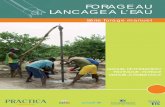

Benin is one of the poorest countries in Africa, with itseconomydependent, as in colonial times, on an agriculture thatis largely undeveloped, and reliance on subsistence farmingand regional trade.Figure2 shows subsistence farmersworkingon their farms.About two-thirds of the work force in Benin isengaged in agriculture, mainly subsistence farming. Much oftheinteriorpopulationisstilldependentonsubsistencefarming;growingbeans,maizeandyams.

For administrative purposes, Benin is divided into 12departments which are further subdivided into 77 communes(Figure 3).The landDivisions areAlibori,Atakora,Atlantique,Borgou,Collines,Kouffo,Donga,Littoral,Mono,Oueme,PlateauandZou.

FrenchistheofficiallanguageofBeninbutmostpeoplespeaktriballanguages,with47%ofthepopulationspeakingFon,12%.

Table 1. Production statistics of some major staple foods and export crops (tonnes) Staples 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Maize 662 227 782 974 750 442 685 902 622 136 788 320 842 626 864 698 671 949 900 000*Millet 29 427 29 519 36 352 34 969 40 632 35 457 36 817 37 707 32 842 40 000*Sorghum 138 429 126 440 155 275 165 342 195 468 163 276 163 831 169 235 156 333 200 000*Yams 1 583 710 1 647 010 1 742 000 1 700 980 1 875 010 2 010 699 2 257 254 2 083 785 2 239 757 2 240 000FCassava 1 989 020 2 112 960 2 350 210 2 703 460 2 452 050 3 054 781 2 955 015 2 861 369 2 524 234 2 525 000FBeans 75 452 74 237 85 613 78 353 100 462 81 823 93 789 104 564 80 178 80 500FGroundnuts 99 160 101 943 121 159 125 377 146 214 124 979 151 666 140 329 99 382 130 000*Others (export) Cocoa 200* 100* 100* 100* 100* 100* 100* 100* 100* 100*Coffee 200F 200F 200F 150F 100F 60* 60F 60F 60* 60*Cotton 364 127 375 586 339 909 393 060 485 522 420 000* 425 000* 341 000F 220 000F 313 500FPalm kernels 220 000 220 000F 220 000 220 000F 220 000F 244 000F 244 000F 245 000F 245 000F 275 000F

* = Unofficial figure F = FAO estimate FAOSTAT [© FAO Statistics Division 2009] viewed 15 March 2009

Over half of Beninois are subsistence farmers

FAO

/17511/R Faidutti

Sunflowers are intercropped with organic cotton as a form of complementary pest control

OB

EPA

B

Figure 2. Subsistence farmers working on their farms

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 7

Adja,10%Bariba,9%Yoruba,5%Sombaand5%Aizo.

Traditional religious beliefsare professed by about 60% ofthe population. Voodoo originatedin Benin and was introduced toBrazil and the Caribbean IslandsbyAfricans.Europeanmissionariesbrought Christianity to the southandcentralareasofBenin.RomanCatholicismisthereligionofabout28.1%,thegreatmajorityofwhomliveinthesouth.Islamisthereligionofabout24%ofthepeople,mostofwhomliveinthenorth.MostoftheMuslims are of the Fulani, BaribaandDenditribes.

In the 2002 census, 43.9%of the population of Benin wereChristian(28.1%RomanCatholic,5% Celestial Church of Christ,3.2% Methodist and 7.6% otherChristian denominations); 24%were Muslim, 17.3% practiceVodun, 6.4% other traditionallocalreligiousgroups,1.9%otherreligious groups, and 6.5% claimno religious affiliation (USDS,2008).

Benin’s political history since independence has been eventful.The first president,HubertMaga,wasoustedin1963bythearmycommander,andaseriesoffourcoupsfollowedinthenextsixyears.In 1970 a three-member presidential commission took power and suspended the constitution. Themembers,includingformerpresidentMaga,weretoserveaspresidentsuccessively.Magaheldofficefirst,succeededin1972byJustinAhomadegbe.Laterthatyear,however,MajorMathieu(laterAhmed)Kérékouseizedpower,endingthecommissionformofgovernment.

Anewconstitution,makingthecountryaone-partystate,waspromulgatedin1977.Threeformerpresidents,detainedsincethecoupof1972,werereleasedin1981.KérékouwaselectedpresidentbytheNationalRevolutionaryAssemblyin1980andre-electedin1984.Kérékousurvivedamilitarycoupattemptfouryearslater.Inlate1989heabandonedMarxism-Leninismandatransitionalgovernmentestablished in1990paved theway for a revivalofmultipartydemocracy.PrimeMinisterNicephoreSoglodefeatedKérékouinthepresidentialelectionofMarch1991.In1996KérékoudefeatedSoglointheelectionsandwaseasilyre-electedinMarch2001.Termlimitspreventedhimfromrunningagain.Kérékousteppeddownattheendofhissecondtermin2006andwassucceededbyThomasYayiBoniinApril2006;apoliticaloutsiderandindependentassumedthepresidency.

Beninwitnessedaseriesofmilitarycoups,anassociationwithMarxism,andthesomewhattypicalhealthandinfrastructureproblemscommontoitsneighbours,andmostWestAfricancountries.Asanewdemocracy,thebrightsideisthatBenin’seconomyisgrowingandtourismisontheincrease,especiallyalongthecoastalareasandinthewildlifenationalparksofthenorth.

ThemajorityofBenin’s7.86millionpeopleliveinthesouth.Thepopulationisyoung,withalifeexpectancyof53years.Around99%ofthepopulationisAfricanof42ethnicgroupssettledinBeninatdifferenttimesandmigratedwithinthecountry.Thefourlargest,whichconstitute54%ofthepopulation,aretheFon,theAdja,theBaribaandtheYoruba.The42groupscanbedividedintofivebroadclustergroups(1)theVoltaic,(2)theSudanese,(3)theFulani,(4)theEweand(5)theYoruba.Thereisasmall

Figure 3. Administrative divisionsSource: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection Benin maps

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile8

European community, of which the Frenchconstitute the largest group. Figure 4 showsthepopulationandtribaldistributionofBeninRepublic.

The Yoruba are found in the southeast(migratedfromNigeriainthetwelfthcentury);theDendiinthenorth-centralarea(camefromMali in the sixteenth century); the Baribaand the Fulbe (Peulh) in the northeast; theBetammaribe and the Somba in the AtacoraRange;theFonintheareaaroundAbomeyinthe South Central and theMina, Xueda, andAja(whocamefromTogo)onthecoast.RecentmigrationshavebroughtotherAfricannationalsto Benin which include Nigerians, TogoleseandMalians.TheforeigncommunityincludesmanyLebaneseandIndians involved in tradeand commerce. The personnel of the manyEuropeanembassies and foreignaidmissionsand of non-governmental organizations andvariousmissionarygroupsaccountforalargenumberofthe5500Europeanpopulation.

Economic activitiesBenin’s economy is based on agriculture.Cottonaccountsfor40%ofGDPandroughly80%ofofficialexports.Also,thereisproduc-tionoftextiles,palmproductsandcocoa.Corn,beans, rice, groundnuts, cashews, pineapples,cassava, yams and other various tubers aregrownforlocalsubsistence(Figure5).

Major cropsThe major cash crop is cotton with a pro-duction record of 427 000 tonnes during the2004/2005 farming season. Its productionhowever decreased to 191 000 tonnes duringthe 2005/2006 season. The future of cottonpresentlygives cause for concern inviewof:(i)environmentaldegradation;(ii)thedysfunc-tioninthestructurestemmingfromreformsinthesector;and(iii)fluctuationinglobalpricesthatnegatively impactsonrural revenuesandthecountry’seconomy.Cropssuchaspineap-pleandcashewnutswhoseproductionattained110000and40000tonnesrespectivelyinthe2004/2005farmingseasonhavebeenaccordedsome recognition. The production from oilpalm went from 130 000 tonnes in 1994 tonearly 280 000 tonnes in 2005. These levelsofproductionarelargelyinadequatetosatisfynational and regional market needs (CIPB,2007).

Figure 4. Population and tribal distributionSource: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection Benin maps

Figure 5. Economic activitiesSource: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection Benin maps

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 9

Foodcropproductionlargelyconsistsofgrainonnearly1100000haofwhich54%aredevotedtomaize.Productionin2005wasestimatedat841000tonnesformaize,207000tonnesforsorghumand73000tonnesforrice.Maize is themostprofitablegrainbut its2004production level(goingbyanaverageconsumptionhypothesis)leftastaplereserveofonly124830tonnesagainst161840tonnesin2005 (CIPB,2007).This isnot enoughgiven that it is thebasecomponent in themanufactureofchildren’scerealsandpoultryfeed.

Ricehasbecomeastrategiccropwithgrowingimportanceinthenationalconsumptionpatternandtrade betweenneighbouring countries (Niger,Nigeria andTogo).Although its level of production isincreasing(from16045tonnesin1995to73000in2005),therearesignificantimports(over450000tonnesin2004andapproximately378000in2005)tocomplementinternalandre-exportationneeds(CIPB,2007).

Asforrootandtubercrops,particularlyyamandcassava,productionlevelshaveremainedconstantin the course of this decade.Cassava has taken on a non-negligible significance as a food crop forthe masses and accounts for 54% of the national production of roots and tubers. There has beenno appreciable improvement in the quality of products owing to lack of consecutive infrastructuraldevelopmenttofacilitateaccesstomarkets(CIPB,2007).

FisheriesThefisherysubsectoraccountsforthelivelihoodof50000fishermenand20000fisherfolk(mostofwhomarewomen).Itisameansoflivelihoodforapproximately70000peopleandaccountsfor2%of the country’sGDP.During the period 1998 to 2005, production stagnated around 40 000 tonnes/yearandtheimportationoffrozenfishincreasedfrom20000tonnesin2001to45000tonnesin2005.Furthermore,theexportofshrimps,onceapotentialsourceofrevenue,fellfrom1000tonnestolessthan700tonnesinthesameperiod(CIPB,2007).Thewaterwaysarenotjudiciouslyexploited,whileaquacultureandthehalieuticproductionarestillunderdeveloped.

Forestry Theforestrysubsectorischaracterizedessentiallybyacontinuousdegradationofforestresourcesandofwildfaunaasaresultofhumanactivity.Thesituationisallthemorealarmingbecause:anincreasinglyimportantfringeofthepopulationlivesunderthethresholdofpovertyandhasnootherchoicethantooverexploitthenaturalresourcestosurvive;needsinfirewoodandtimberareincreasingbythedayduetopopulationgrowthandtothedevelopmentofeconomicactivities(CIPB,2007).

Animal productionMost projects that were designed to promote animal production through support to animal geneticresources(AGR),training,information,animalhealth,etc.,haveendedwithnoobviousindicationforacontinuation.Oneoftheweaknessesofthesystemliesintheextensionoftheveterinarydutiestoprivateclientele.Ongoingeffortsarefocusedonsupportingmodernandtraditionalraisingofsmallruminantsand dairy production.However, the problemof safeguarding the zoological germplasmmanaged byvariousgovernment-ownedfarmsremainsunresolved(CIPB,2007).

The livestock subsector accounts for approximately 6% of the GDP. It is marked by traditionalhusbandry practices of bovine, goats, pigs and poultry despite conclusive results attesting to highproductionlevelsofmodernbreedingprojectsinthelastdecade.

Currentestimatesin2004were1826300bovines,2300000smallruminants,293200swineand13200000birds,whicharenotenoughtocoverthecountry’sneedsinanimalprotein,particularlyinmeat,milkandeggs.Thepresentlevelofimportedfrozenmeat(8800tonnesin2005)meansthatBenininhighlydependentonimports(CIPB,2007).Furthermore,modernlivestockbreedingoutletsthathavedevelopedinperi-urbanareasfortheproductionofeggsandofbroilersfacedirectandstiffcompetitionfromtheimportersoffrozenpoultryandeggssoldatverycheappricesinthelocalmarket.

The raising of non-conventional species (snails, grass-cutters/bush rats, rabbits, etc.) is beingincreasinglydevelopedbutatapacethathasnotyetcompensatedforthedeficits,butwhichleavesroomforpossibledevelopmentoffoodpreferenceshereandthere(CIPB,2007).

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile10

Mineral resourcesBeninbeganproducingamodestquantityofoffshoreoilinOctober1982.Productionceasedinrecentyears but exploration of new sites is ongoing. Other mineral resources of Benin include iron ore,phosphates, chromium, rutile, clay,marble, diamonds and limestone. Limestone is produced for usein cementmanufacturing, and industrial diamonds are recovered for export, butmost othermineralresourcesareundeveloped.

A number of formerly government-owned commercial activities are now privatized, and thegovernment,consistentwithitscommitmentstotheIMFandWorldBank,hasplanstocontinueonthispath.SmallerbusinessesareprivatelyownedbyBeninoiscitizens,butsomefirmsareforeignowned,primarilybyFrenchandLebanese.Theprivatecommercialandagriculturalsectorsremaintheprincipalcontributorstogrowth(BureauofAfricanAffairs,June2008).

2. SOILS AND TOPOGRAPHY

SoilsBenin soils vary significantly as much in nature as in fertility and geographical distribution. Totalcultivableareaaccountsfor62.5%ofthetotalsurfaceareaofthecountry,andonly20%ofthisareaor12.24%ofthenationalterritoryisactuallyexploited.Fivemajorsoiltypescanbeidentified(Figure6).Theseare:(i) tropicalferruginoussoilsdevelopedongranito-gneissicformationsofcentralandnorthernBenin,

andontheschistsofthenorthwest.Theyoccupyapproximately70%oftheterritory;(ii)ferraliticsoilsformedontheContinentalterminalandCretaceoussandstone.Thesecoverapproxi-

mately7to10%ofthetotalsurfaceareaofthecountry;(iii)hydromorphic soils.These cover between5

and8%of thecountryandcanbe found inthevalleys,basinsandalluvialplains;

(iv)verticgreensoils.Thesecoverapproximately5%of thelandandareusuallyfoundintheMedian Dip (i.e. between the northern andsouthernpartsofthecountry);and

(v) roughandundevelopedmineralsoils.Theseoccupybetween5and7%oftheland.TheyareusuallyfoundincoastalareasandrockyoutcropsofMiddleandGreaterBenin(NAP/DC,1998).

TopographyThecountrycanbedivided into fourareas fromsouthtonorth.Thelowlying,sandy,coastalplain(highestelevation10m) isatmost10kmwide.It is marshy and dotted with lakes and lagoonscommunicating with the ocean. The plateausof southern Benin (altitude between 20 m and200m)aresplitbyvalleysrunningnorthtosouthalong the Couffo, Zou, and Oueme Rivers. Anarea of flat lands dottedwith rocky hillswhosealtitude seldom reaches 400 m extends aroundNikkiandSave.

A range of mountains extends along thenorthwestborderandintoTogo;thisistheAtacora,

Figure 6. Map of soil types in Benin RepublicSource: Soil Maps of Africa. ORSTOM, Paris

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 11

Table 2. Climate chart for Cotonou (60 35 N, 20 38 E, 29 feet [9 m] above sea level)Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Avg. temperature 81 83 84 83 82 80 78 77 78 80 82 82

Avg. max temperature

88 90 90 89 88 85 83 82 83 85 88 89

Avg. min temperature

77 78 79 79 77 76 75 75 75 76 77 77

Avg.rain days 0 1 2 5 6 10 6 5 6 5 1 0

Avg. snow days 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

withthehighestpoint,MontSokbaro,at658m.Twotypesoflandscapepredominateinthesouth.Beninhasfieldsoflongfallow,mangrovesandremnantsoflargesacredforests.Intherestofthecountry,thesavannahiscoveredwiththornyscrubanddottedwithhugebaobabtrees.

3. CLIMATE AND AGRO-ECOLOGICAL ZONES

ClimateBenin has a tropical climate (hot and humid) with two rainy and two dry seasons. The principalrainyseasonisfromApriltolateJuly,withashorterlessintenserainyperiodfromlateSeptembertoNovember.ThemaindryseasonisfromDecembertoApril,withashortcoolerdryseasonfromlateJulytoearlySeptember.

Byitslocation(between06°10’and12°25’N)Beninisintheinter-tropicalzone.ItsclimaticconditionisthereforetypicaloftheWestAfricanclimate,whichalternatesbetweenthemonsoon(fromtheocean)duringthecoolandwetseason,andthehighthermalamplitudeharmattanwindthatblowsdailyduringthedryseason(fromtheSahara).Thesetwosetsofpowerfulwinds(MonsoonandHarmattan)recedealternatelytowardsnorthandsouth.Theirpointofcontact,calledtheInter-tropicalFront(ITF),isthecentral point of all precipitation that causes atmospheric disruptions.Temperatures and humidity arehighalongthetropicalcoast.InCotonou,forexample,theaveragemaximumtemperatureis31°C;theminimumis24°C.Table2presentstheclimatechartforCotonou.

Variations in temperature increase when moving north through savannah and plateau towards theSahel.AdrywindfromtheSaharacalledtheharmattanblowsfromDecembertoMarch.Grassdriesup,thevegetationturnsreddishbrown,andaveiloffinedusthangsoverthecountry,causingtheskiestobeovercast.Itisalsotheseasonwhenfarmersburnbushinthefields.TheRepublicofBeninclimateispeculiarinsomeareas.ForexampleCIPB(2007)reportedthatBeninhasthreeclimaticzonesthatcomprise:

• Adrytropicalzonebetween90and120.Rainfallrecordsrangefrom900to1100mm/year.Theperiodofvegetativegrowthislessthan145daysduringtherainyseason.

• A dry savannah zone between 80 and 90 N. Average rainfall fluctuates between 1 000 and1200mm/year.Theperiodofvegetativegrowthisabout200daysduringtherainyseason.

• AsubequatorialzonestretchingfromtheAtlanticCoasttoalinepassingthroughSavé(7°30’N)where rainfall recordsvarybetween950 to1400mm/year; theperiodofvegetativegrowth isnearly240days.

The climatic zones are characterized by two rainfall patterns. From the coastal areas up to Save,presentsabimodalrainfallpattern(ApriltoJuneandSeptembertoNovember).Rainfallinthisregionisratherunpredictableanddifficulttoharnessespeciallywithregardtonon-perennialcrops.Moreover,theannualrainfallisnotsufficienttogeneratesatisfactoryproductionlevelsforcropssuchasoilpalm,cocoaandcoffee.

Source: CIA- World Factbook Profile /Wikipedia

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile12

Beyond Savé and the further one goes north, a unimodal rainfall pattern emerges (fromMay toOctober).Thiszoneissuitablefordiversefoodcropsandforcottonproduction.

Azonal rainfall Asfarastherainfallpatternisconcerned,Benin’sazonalityisremarkablebothwithregardtothetotalaverage rainfall level per annum, and its level on the rainfall scale.The total average rainfall levelsper annum fall symmetrically into the following two: high rainfall level in the northwest (Djougouand surrounding areas) and southeast (Porto-Novo and surrounding areas) (1 500–1 400 mm); andlowrainfalllevelinthenorthandnortheast(theNigervalley)andlowMonovalleyinthesouthwest(1000–850mm).

WithinthesetwoextremeregionsisavastareaincludingtheZou,MiddleOuéméandCentralBorgoubasinswhereannualaveragerainfalllevelsoscillatebetween1100and1200mm.TheconfigurationoftheannualisohyetsshowsanindigentrainfallzonelocatedintheareasborderingtheseawhichextendsdiagonallyinlandtowardstheSW–NEinadownwardcurve.

Benin is characterized by the following two rainfall gradients; a littoral gradient extending fromSèmè (1 500mm) towards the “thalweg” of the diagonal on theGrand-Popo-Bopa-Zagnanado axis,andanorthernsubmeridiangradientextendingfromDjougoutothepiedmontsoutheastoftheAtacoramountainrange(1400mm),towardsMalanvilleintheNigervalley(900mm)(DRP,BeninRepublic,1996).Betweenthe7°30’and9°parallels,arainfall“marsh”extendswithsomelocalized“poles”ontotheinselbergs(island-mountains)oftheIdaca–Cabècountry.

Rainfall patterns: Dependingonone’spositiononthelatitude, therainyperiodscombineinvariouswaystodefinetherainfallpattern.Thus,thereis:

i. abimodalpatternwithfourseasonsincludingtwodryandtworainyseasonstothesouthofparallel7°45’;

ii.aunimodalpatternwithtwoseasons,oneofwhichisadryseasonandtheotherarainyseasontothenorthofparallel8°30‘and

iii.anintermediatepatternalternatingbetweenbimodalandunimodalbetweenthesetwoparallels.Allthingsconsidered,Beninpresentstworainfallpoles:i. eastoftheOuéméDeltainthesoutheasternpartofthecountry;andii. thepiedmontsoutheastoftheAtacoraMountainrange.

Classification of Beninois climates Thespatialanalysisofthethreemajorclimaticparametersincludingtemperature(thermalamplitude),rainfall(coefficientofconcentrationofseasonalprecipitation)andrainfallvariance(coefficientofvaria-tionofannualprecipitations)madeitpossibletoidentify12climaticfeaturesinBenin(Figure7).Thesecanbeclassedundernineprimaryclimatetypes,allofwhicharedividedintotwogroups:

Group of climates with unimodal rainfall pattern Inthisgroupare:(i)theSubsahelianclimateofNorthernBorgouintheNigerbasin,characterizedbystrongthermalamplitude,ashortrainyperiod(3to4months),butwithlowvariabilityininter-annualrainfalllevel;and(ii)theCentralBorgouClimate,whichisatropicaltransitionalclimatewithastrongerthermalamplitude.Thetropicaltransitionalclimatehasalongrainyperiodandlowvariabilityininter-annualrainfall.

Group of climates with bimodal rainfall pattern In thisgroupare: (i) the InselbergclimateofcentralBenin,whichhas thesamecharacteristicas theAtacoraclimate;(ii)theZouMiddleBasinclimate,especiallythelowerOkparaclimateandthemiddleZouclimate;(iii)theLowerNorthernPlateauxclimate(tothenorthoftheLamadip),whichisavariantofthetropicalandsubmarineclimate(lowrainfallvariability,maritimeinfluences,longrainyperiod)theonlydifferencebeingaslightlyhigherrainfallvariabilitylevel;(iv)theLowerSouthernPlateauxclimatemadeupoftheeasternplateauxandwesternplateauxclimates;(v) theLowerOuémé(ortheOuémé

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 13

Delta)climatewhichhastwotendenciesincludingthePorto-NovoareaandtheCotonouareaclimates;and(vi)theLowerMonoandLakeAhéméclimates.Thisclassificationlaysemphasisparticularlyontheclimaticconstraintstowhichruralcommunities’productionactivitiesaresubjected.

Vegetation (agro-ecological zones)Inspiteoftheapparentlyfavourablegeographicalposition,Beninisnotaforestcountrylikeneighbour-ingNigeria,GhanaandCôted’Ivoire.However,about65%ofthewholeterritoryiscoveredbybushyvegetation.Out of this brushy vegetation, PAGE (PilotAnalysis ofGlobal Ecosystems) calculationsbasedonGlobalLandCoverCharacteristicsDatabase(GLCCD,1998),indicatedthatBeninhas93.1%grasslandarea,makingitthecountrywiththehighestgrasslandinsub-SaharanAfrica.Generally,thetypesofnaturalformationsfoundinBenin,dependingonthevariousclimaticconditions,are:

The South with its subequatorial type climatehasaBrazilian-type Ipomoea lawn, thatconsistsofRemirea maritima, Ipomoea asarifoliaontheoldoffshorebar;aclearforestwithLophira lanceolata(falsekaritétree),Carissa edulis, Byrsocarpus coccineus ontheoldoffshorebar;amarshyformationinthewestmadeupofMitragyna inermis, Cola grandiflora, Ceiba pentandra, Lonchocarpus sericeus, Andropogon gayanus,etc.Inbrackishareas,amangroveformationmadeupofRhizophora racemosa(mangrove),Avicennia germinansandDalbergia ecastaphyllum.Thedisappearanceofthiswoodyveg-etation gaveway toPaspalum vaginatum, Philoxerus vermicularis, andSesuvium portulacastrum; amarshyformationintheEastmadeupofRaphiale(Raphia hookeri, Raphia vinifera), Ficus congensis, Anthocleista vogelii, Alstonia boonei, Cyrtosperma senegalense, Cyperus papyrus, Eleocharis spp., etc;andalittleeverywhere,butmoreonclayeysoilinElaeis guineensis(oilpalm)plantations.

North-central with the Guinea-Sudan type climateLocatedbetweenparallel8°NigerRiver(NR),theSavè–Savalouline,andparallel9°30NigerRiver(NR),theKoura–Partago-Bori–Guinagourouline,thiszoneconsistsof:drythickforests(betweenSavalouandDjougou)withIsoberlinia doka, Isoberlinia tomentosa, Pterocarpus erinaceus, Afzelia africana, Antiaris africana, Chloptelea grandis, Milicia excelsa, Cola gigantea, Celtis zenkeri, Khaya senegalensis, Khaya grandifolia, Amblygonocarpus andongensis, Swartia madagascariensis, Erythophleum guineense; clear forests and savannahs withAnogeissus leiocarpa, Butyrospermum paradoxum,Daniellia oliveri, Isoberlinia doka, Parkia biglo-bosa, Combretum micranthum, Guieria senegalensis, Boscia salicifolia, Albizia chevaileri;andforestsgallerieswithCeiba pentandra, Milicia excelsa, Khaya senegalensis, Diospyros mespiliformisandVitex doniana.

The North with its Sudan-Sahel type climateLocatedbetween10°Nand12°30’N,ithasshrubbyandwoodedsavannahswithLophira lanceolata, Acacia ataxacantha, Acacia.macrostachya, Butyrospermum paradoxum, Parkia biglobosa, Entada africana, Burkea africana, Terminalia spp, Combretum spp, Pterocarpus erinaceus, Detarium microcarpum, Sterculia tomentosa Acacia seyal, Balanites aegypti-aca, Guieria senegalensis;clearforestswithAnogeissus leiocarpa(deepsoils)orwithIsoberliniadoka(siliceous soils); and forest galleries withKhaya senegalensis,Diospyros eliottiti,Kigelia africana, Diospyros mespiliformis, Vitex chrysocarpa, Cola laurifolia, Syzygium guineense, Mimosa pigra andDaniellia oliveri.

ThefloraofBeninissufficientlydiversified;howeveritisunfortunatetonotethatforestcoverbecomesdangerouslymore sparsewitheachyear thatpasses (DRP,1996).Alsoapartlydepleted thick forestonclaysoilbetweentheoffshorebarandlatitude7°NRalsoexistbutonlyavestigeofthisremainsintheformofscrapsdeepintheheartoftheLAMAclassifiedforest,botanicalreserves,theINRABOil-palmResearchCentre inPobè, forest relicsand/orsacredforestsofall sizesandformsscatteredalongthisstrip.Speciescharacteristicofthisformationare:theAfzelia africana(ling),Ceiba pentan-dra,Triplochidon scleroxylon(samba),Milicia excelsa(Iroko),Diospyros mespiliformis(falseebony),.Albizia glaberrima, Albizia ferruginea, Albizia zygiaandAntiaris toxicaria.

Thevegetation in theGuineaZones is dominatedbymoistwoodlands and savannahs (Figure 8).Theseparationbetweenanorthernandasouthernpartcoincidewiththenorthernboundaryofbimodal

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile14

rainfall in southernBenin.TheNorthernGuineaZone ischaracterizedbywoodlands, treeandshrubsavannahswithabundantIsoberliniaspp.andButyrospermum paradoxa(Adjanohounet al.,1989).

In the Southern Guinea Zonemoister types of woodland and savannahs with abundantDaniellaoliveriarefound.IntheGuinea-CongolianandCoastalZoneamosaicofforestsandsavannahsexists(Figure9).Inthetwozonesmostoftheoriginalvegetationhasbeenreplacedbysecondarygrasslandsorsavannahsduetohumanimpact.Thisfactwasemphasizedbyvegetationstudiesonbushandgrassfallows(Bohlinger,1998).

Vegetation zones in Niger and Benin – present and past zonationSource: Alexander Wezel, Brigitte Bohlinger and R. Böcker (1999)

Vegetation zones in BeninSource: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection Benin Maps

Figure 7. Vegetation zones of Benin

Figure 8. Moist woodlands and savannahsSource: Alexander Wezel, Brigitte Bohlinger and R. Böcker (1999). Vegetation zones in Niger and Benin - present and past zonation.

Figure 9. Coastal zone (mosaic of forests and savannahs)Source: Alexander Wezel, Brigitte Bohlinger and R. Böcker (1999). Vegetation zones in Niger and Benin - present and past zonation.

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 15

TheprevailingvegetationtypesintheSudanianZonearewoodlandsandsavannahs.Alongrivers,galleryforestscanbefound.IntheNorthernSudanianZone,vegetationisdominatedbyCombretaceaeandMimosaceaewoodlandorsingletreeswithperennialgrasslayersofAndropogon gayanus(sandysoils),Loudetiaspp.(laterite,glacis)andHyparrheniaspp.(moistersites)(PeyredeFabrègues,1980).

TheNationalAgriculturalResearchInstituteofBenin(Anon,1995)recognizedfiveagro-ecologicalzonesdefinedasSouthernZone,TransitionZone,SouthernBorgou/SouthernAtacoraZone;NorthernBorgouzone andAtacoraZone (Vissohet al., 2004).Table3presents the characteristicsof the fiveagro-ecologicalzonesofBenin.

Southern ZoneTheSouthernZonecoversapproximately13%of thetotalareaof thecountrywheremorethan60%ofthetotalpopulationofBeninlive.ProductionsystemsintheSouthernZonearecharacterizedbyahighpopulationdensityestimatedonaverageat323inhabitantskm2(Table3)accordingtothe‘InstitutNational de la Statistique et de l’AnalyseEconomique’ (Anon, 2003), resulting in a strong pressureonarableland(Brouwers,1993).Animalhusbandryislimitedtosmallruminantsandpoultry.Landismostlyinheritedandextremelyfragmented(Vissohet al.,2004).

Transition ZoneHumanpopulationdensity in theTransitionZone,averaging47 inhabitantskm2, is lower than in theSouthernZone,resultinginlesspressureonarablelandthanintheSouthernZone(Anon,2003).Apartfromsmall-ruminanthusbandryandpoultry,thereisanattempttorearoxenbyafewricherfarmersinanattempttousedraughtfarmingtoexpandtheircottonarea.AsintheSouthernZone,agricultureisnotassociatedwithlivestock(Vissohet al.,2004).

Borgou-Atacora ZoneTheproductionsystemsoftheSouthernBorgou-SouthernAtacoraZone,theNorthernBorgouZoneandtheAtacoraZonearetakentogetherasproductionsystemsoftheNorthernZonebecauseofthesimilari-tiesamongthem,particularlywithregardtosoilsandrainfallpatterns.

TheproductionsysteminnorthernBeninischaracterizedbyanevenlowerpopulationdensitythanintheTransitionZone(onaverage27inhabitantskm2)(Vissohet al.,2004).

The rainfall pattern is unimodal.Over theperiod1970–2000, the amount of rainfall per year hasvariedconsiderably,withaseveredecreaseinthethirddecade(1981–1990),averaging1000mmintheSouthernBorgou-SouthernAtacoraZonesandabout750mmintheNorthernBorgouZone.Livestockisquitedevelopedandisintegratedinthearablefarmingactivities.Inadditiontotheimplementsusedin

Table 3: Characteristics of the five agro-ecological zones of Benin

Agro-ecological zone

Relative area%

Annual rainfall (mm)

Climate Soil type1 Natural vegetation

Main crops2 Land holding

Southern Zone

13 1 000–1 400 Subequatorial, with two rainy and two dry seasons

Ferralitic Relics of forest

Maize, cassava, cowpea, oil palm, vegetables

Inheritance, purchased

Transition Zone

15 1 000–1 200 Transitional (no clear distinction between the two rainy seasons)

Tropical ferruginous

Woody savannah

Maize, cashew, cassava, cotton, groundnut, yam

Inheritance, rented

Southern Borgou Southern Atacora Zone

32 900–1 300 Sudano- Guinean. One rainyand one dryseason

Tropical ferruginous

Woody savannah

Sorghum, cotton, maize, yam

Inheritance

Northern Borgou Zone

24 600–800 Soudano-Sahelian. One rainy and one dryseason

Tropical ferruginous

Shrubby savannah

Cotton, maize millet, sorghum

Inheritance

Atacora Zone 16 900–1 200 Sudanian. One rainy and one dry season

Tropical ferruginous

Treed savannah

Sorghum, cowpea maize, millet

Inheritance

1 FAO classification2 Most important crop first, other crops in alphabetical order.Source: Anon, 1995, cited in Vissoh et al., 2004

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile16

theotherproductionsystems,farmersusedraughtoxenortractorstoexpandtheirareasandmaximizeprofit(Vissohet al.,2004).

Besidestheabove-mentioned,theCouncilofPrivateInvestorsinBenin(CIPB,2007)furtherreportedeightagro-ecologicalzonesforBenininwhichvariousvegetables,animal,halieuticandagro-forestryactivitiesarecarriedout.Theeightagro-ecologicalzonescomprise:

Zone 1Zone1comprisestheKarimama,MalanvilleandnorthernKandicommunitiesintheDistrictofAlibori.Therearetwotypesofsoilsinthiszone:theferro-soilwithacrystallinebaseandtheveryfertilealluvialsoilsoftheRiverNiger.Thezoneissusceptibletohigherosion.

Themaincropsfoundherearemillet,sorghumandcowpea.Inaddition,cotton,maize,rice,beans,onionsandvegetablesarealsogrownalongtheNigerandAliboriRivers.

Potatohasonlybeenrecentlyintroduced.Themajoradvantagesarethevastexpanseofarablelandandthepracticeofanimaldrawnharnessed

cropping. The land bordering the rivers allows for large-scale off-seasonmarket gardening such aspepperandtomato.TwolargemarketsnamelytheKarimamaandMalanvillemarketsprovideoutletsformarketingagriculturalproducts.

Zone IIZone II covers Kerou and the northeast of Kouandé communities in the District of Atacora andBanikouara,Segbana,GogounouandthesouthofKandicommunitiesintheAliboriDistrict.Theclimateistropicalwithonlyonerainyseason(800to2000mm/year).Thesoiltypeisferrosolonacrystallinebase.Thecroppingofcottoniswell-developedandaddssomevibrancytothesocio-economicactivitiesinthezone.Theagro-economicconditionsareconducivetothecultivationofawidevarietyofcropssuchascotton,maize,groundnutandsorghum,whicharegrowneachyear.Theperennialcropsareshea-butterandcashew-nuttrees.Therootcropsareyamandcassavausedforchips.

Zone IIIZoneIIIcoversthesouthernBorgouexceptthesouthofTchaourouandextendsfromPehunco,easternDjougouintheDistrictofDonga,tonorthernTchaourou,ParakouandN’dali,Perere,Nikki,Dinende,KaladeandBemberekeallintheBorgouDistrict.

Ithasatropicalclimatewithamonomodalrainfallpattern.Thesoilistropicalferrosolanditsfertilityisvariableandsusceptibletoleaching.

The vegetation is savannah shrub with a dominance of Butyrospermum paradoxa (shea-butter)species.Thecroppingsystemismainlysorghumandyamwithahighincidenceofcottonandmaizeintercropping.Cassava,peanut,riceandlegumesarealsogrown.

Thenumerousadvantagesofthiszoneare:• anagro-ecologysuitableforfruitandforestcrops;• landavailability;• easyaccesstoagriculturalinputsthroughtheservicesofCOBEMAG(CoopérativeBéninoisede

MatérielAgricole);• possibleaccesstoagriculturalservices:labour,transportforharvestedproduce,and;• arelativelydevelopedlivestockbreedingsector.

Zone IVZone IV ismadeup ofOuake,Copargo,Boukoumbe,Tanguieta,Materi,Natitingou,Toukountouna,Kouandé,CoblyandthewestofDjougoucommunities.Theclimateistropicalandtendstowardsthedrysavannahwithanirregularandfluctuatingrainfallpattern.Thesoiltypeisferrosolwithadeepbaseandpoorwaterreserve.Thesesoilsarescarcelyfertileexcepttheswampyareas.

The cropping system is dominated bymillet, sorghum, fonio, Bambara groundnuts, cowpea andgroundnut.Theswampsandsomewaterreservesofferthepossibilityofgrowingcocoyam,wateryam,sweetpotato,riceandoff-seasonmarketgardenproduce.

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 17

Zone VThiszoneistropicalguineasavannahwithahighrainfallpattern(1100to1400mm/year)andstretchesfromtheDistrictsofAtacora,Borgou,Mono,OuémetotheZouwithalargeexpanseofvirginlandinBassilaintheAtacoraDistrict.

Yams,maize,cassava,groundnut,rice,citrusandcashew-nutarethemaincropsgrowninthiszone.Shea-butter, almonds andParkia nuts aswell asmaize andgroundnut aremarketed inDjougouandTogo.

ZoneValsocoversthesouthofthesubdistrictofTcharaouintheBorgouDistrictwherefoodcropsarecultivated.TheMono,thenorthernAplahoueandKloukanme,aswellasthenortheastofLalo,havegreatpotentialforagriculturalproductionofannualandfruitcrops.

TheOueméDistrict is in thenorthofKetou and thenorthofPobé.This zone is very fertile andis suitable for growingmaize, groundnut, cowpea, cassava, yam and cotton.The income-generatingactivitiesrevolvearoundthecollectionandmarketingofmaize,cowpeaandyam.

IntheZouDistrict,zoneVcoversthesubdistrictofnorthernZouandDjidja.Theannualcropsgrownareyams,cassava,cotton,groundnuts,cowpea,maizeandpepper.Off-seasonfarmingsuchasoff-seasonmarketgardenproduceandriceisundertakenintheswamps

ofDassa,GlazoueandSavalouandthemarketingoffoodcropsandtheirderivativesisverydeveloped.

Zone VIThis zone extends from the Plateau,Atlantic,Mono-Couffo andOuemé to the ZouDistricts and ischaracterizedbyatropicalguineaclimateandabimodalrainfallpattern.

Thesoilishardpanprofoundlydegradedandeasytoworkon.Thecropscultivatedherearemaize,peanut, cowpea, cassava, pepper, coffee, fruit trees (mangos, citrus and banana) and oil palm trees.Legumes,livestockbreeding,avicultureandaquaculturearealsopractised.

Privateirrigationinitiativesfromartisanaldrillingsorfromwaterwaystosupportoff-seasonlegumefarmingandricecultivationhavestartedinthiszone.

Zone VIIThis zone covers theAtlantic,Mono,Ouemé and theZouDistricts. It is characterized by a tropicalguineaclimatewithabimodalrainfallpattern.Itshumidanddeepclayeysoilisfertilebutoftenhydro-morphicanddifficulttoworkon.Thecroppingsystemisdominatedbymaize(leadingrotatingcrop),cowpeaandvegetables,riceandforesttrees,smallholderstock-raisingandaviculture.

Zone VIIIIt stretches from theAtlantic,Mono to theOueméDistricts.The climate is tropicalGuineanwith abimodalrainfallpattern.Whilethealluvialsoilisveryfertile,thesandysoiloftheLittoralismarginallyfertile.Thecroppingsystemisdominatedbymaize(leadrotatingcrop),cowpeaandvegetables.Maizeandcassavaarethemajorcropsgrownonthesandysoils.TheAtlanticandLittoralDistrictsencompasstheurbantownsofCotonou,OuidahandtheAbomey-CalaviandSo-Avacommunities.Arablelandisnotreadilyavailable:off-seasoncropandvegetablecultivationiscarriedoutinthevalleysandincludesfreshmaize,tomato,pepper,vegetables.Thevegetationzone(agro-ecologicalzones)classificationsofthedifferentauthorsvary,however,astheyportraytoalargeextenttemporaltrendsofthecountry.

Hydrographic networkBeninhasmanyhydrographicalnetworks including3048kmofwatercourses.and333km2ofwaterbodies(lakesandlagoons),locatedinthesouthernpartofthecountry.

Threebasinsfeedthisnetwork:theNigerbasin,thePendjaribasinandtheCoastalbasin.

The Niger basinTheRiverNiger,oneof the largest inAfrica (4206km), servesasa120-kmborderbetweenBeninandNiger.TheNigerBasinismadeupofthreerivers:Mékrou(410km),Alibori(338km)andSota(250km).

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile18

The Pendjari BasinThePendjariBasin in thewest(380km)takes itssourcefromtheAtacoramountainrangeinBenin,flowstowardsthenorthwest,movingtowardsthesouthwestintotheRepublicofTogowhereitisknownasOti,beforefallingintotheVoltaRiverinGhana.WiththeexceptionoftheRiverNiger,alltheserivershavethesametropicaltide,risingduringtherainyseason(July–October)andebbingtowardstheendofApril.

The Coastal Basin TheCoastalBasinismadeupofthreeriversknownas:Ouémé,CouffoandMono.TheOuéméRiveristhelargestinthecountry(510km),andistheoutletoftwomajortributaries:Okpara(200km)totheleftbankandZou(150km)totherightbank.ItissubjecttotheinfluenceoftheSudanandsubequato-rialclimates,buthasarathertropicaltide.Thesubequatorialinfluenceisweakandexistsonlyinonesmallareatowardsthemouthoftheriver.ItusesLakeNokouéandthePorto-Novolagoonasconduitsinitspathtowardsthesea.Couffoisasmallcoastalriverof190kmthattakesitssourcefromtheDjamimountainrangeinTogo.ItdrawswaterandalluviafromLakeAhémé.

Finally,moretothewest,theMonoRiver(500km)servesastheborderbetweentheRepublicsofBeninandTogoonthelast100kmofitscourse.IttakesitssourcefromtheAlédjomountainrangeinTogo,andfalls into theGrand-Popolagoon,which itusesasaconduit into thesea throughtheAvlopass.Themajorwaterbodiesare:(i)LakeNokoué(150km²);(ii)LakeAhémé(78km²);(iii)LakeToho(15km²);(iv)OuidahLagoon(40km²)(v)Porto-NovoLagoon(35km²);and(vi)Grand-PopoLagoon(15km²).

4. RUMINANT LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION SYSTEMS

Traditionally,livestockareacomponentinfarmingsystemsandalsoanimportantsourceofincomeforthepoorinBenin,asinmostdevelopingcountries.Animalproductionmayproducehigherreturnsthancropproduction.Animalproductionisacommoditywithahighvalueaddedoutput,thoughaccessibilityisoftenlimitedbycapitalforpurchaseoflivestockwhilepotentialusemaybelimitedbyculturalandreligiouspreferences(Delgadoet al.,1999).

Livestockisimportantinlivelihoodstrategiesofthepoor(savings,insurance,security,accumulationanddiversificationofassets,socialandculturalfunctions).

Theherdingofcattle,sheepandgoatspredominatesinthegrasslandsofthenorth.ServiceNationaldel’Elevage(1977)estimatedcattlepopulationat726000,sheep881000andgoats848.00.In1997cattlewereestimatedat1350000; sheep634000andgoats1087000.However, theWorldGuide(undated)estimateforcattlewas1438000;sheep645000andgoats1183000goats.In2003therewere1600000cattle,670000sheepand1300000goats,(WorldGuide,undated).FAOfiguresfor2007areasfollows:cattle1900000,sheep811200andgoats1439600.

Detailedprojectionsofthelivestocksubsectormaybeestimates(Table4a);however,dataformeatand milk production, live animal and milk/milk product imports are given in Table 4b (from FAOdatabase,2009).

Gruvel(1978)reportedthatthedistributionofcattlebreedsinBeniniscomplicatedandinaconstantstateofchange.ThefourcattletypesinBeninaretheLagune,orDwarfWestAfricanShorthorn,theSomba, or Savannah Shorthorn, the Borgou, which is a Zebu x humpless crossbred, and the Zebu.Table5presentscattledistributionbybreedtypes,whileTable6presentsdistributionbyprovinces.

The table indicates that the largest breed group is theZebu xBorgou crossbreed.This illustratestheabsorptionprocessofhumplesscattlebyZebu.The2700SombarecordedforBoukombéDistrictmay,however,beanunderestimate. In the table thebreed typesare reduced to fourgroupswith theapproximatedistributionofeach.

TherearetwogeneraltypesoftraditionalcattleproductioninBenin;(i)sedentaryproductionintheGuineanregion,whichaccountsforabout20%ofthenationalherd,and(ii) transhumantproduction,whichaccountsfortheother80%(Atchy,1976).

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 19

Sedentary production systemsSedentaryproductionsystemsinthesouthcanbegroupedintothreetypes.Thefirstinvolvesfreegrazingonfloodedplains.WhenwatersarelowintsetseareasfromDecembertoJune,theanimalsarelefttograze freelyon fieldsdemarcatedbywater.As thewater rises, the animals aregathered together andkepton raftsand fodder iscollected fromoutside the floodedareaandbrought to themeverydayby

Table 4b. Benin statistics for meat and milk production (tonnes), live animal (head) and milk imports for the period 1998–2007 Products 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Beef and veal prod. 19 800 18 920 17 983 19 173 19 783 20 438 21 109 21 780 22 000 22 570Sheep meat prod. 2 315F 2 289F 2 355F 2 297F 2 349F 2 347F 2 452F 2 626F 2 930F 3 050FGoat meats prod. 3 860 3 881 4 076 4 255 4 232 4 424 4 594 4 732 4 800 4 900FGame meat prod. 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 000F 6 100FTotal milk prod. 25 075 26 995 29 875 31 245 32 130 33 150 34 322 35 325 36 360 37 200Live cattle imports nos. 642 273 6 591 9 680 3 113 15 526 8 355 15 000 18 000 -Live sheep imports nos. 17 000 20 300 35 000 49 500 45 800 21 000 22 200 20 000 15 514 R -Live goat imports nos. 13 200 11 000 30 000 56 348 52 137 56 348 40 000 35 000 35 000 -Whole Milk evaporated imports (,000.MT) 1 549 2 369 2 025 925 1 248 1 059 2 037 1 648 1 623 -

R - Estimated data using trading partners database F – FAO estimates - No data Source: FAOSTAT data (FAO Statistics Division 2009) Accessed 13 March 2009

Table 4a Data on Benin ruminant livestock population (head) Livestock species

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Cattle 1 370 780 1 438 140 1 487 160 1 584 380 1 635 060 1 689 010 1 744 750 1 800 000 1 850 000 1 900 000Goats 1 113 628 1 175 891 1 234 409 1 250 000 1 270 000 1 300 000 1 350 000 1 380 000 1 410 000 1 439 600Sheep 620 278 653 530 672 099 655 000 670 000 670 000 700 000 750 000 780 000 811 200Asses 500 500 572 600 600 600 600 600 - -Horses 500 389 913 1 000 1 000 1 000 1 000 1 000 1 000 1 050Camels - - - - - - - - - -

- Data not available Source: FAOSTAT data (FAO Statistics Division 2009) Accessed 13 March 2009

Table 5. Cattle distribution by breed type Breed Type Distribution Number % of National herd

Zebu North of Borgou Province 55 200 7.7Zebu x Borgou Centre and south of Borgou Province 253 100 35.3Somba Boukombé District 2 700 0.3Borgou x Somba Atacora Province 104 600 14.6Borgou South Borgou and east Atacora 193 600 27.0Borgou x Lagune South and centre of country 81 700 11.4Lagune Lower valleys of Ouémé, Aplahoué and Abomey 26 500 3.7Total 717 400 100.0

Source: Canard, P. and B. Striffling, quoted in Gruvel, 1978

Table 6. Cattle distribution by province Province Cattle

Numbers % of National total

Lagune Somba Borgou and crosses

Predominantly Zebu

Borgou 482 600 66.5 - - a aAtacora 138 700 19.1 - a a -Zou 56 100 7.7 a a -Ouemé 21 500 3.0 a - b -Atlantique 12 000 1.7 a - b -Mono 14 700 2.0 a - b -Total 725 600 20 000 75 000 500 000 130 000% 100.00 3 10 69 18

a. Majority group; b. Minority group.Source: Service National de l’Elevage, 1977.

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile20

boat.Animalsbelongingtovillagefishermenandfarmersarecombinedinoneherdthatistendedbyahiredherdsman.Inotherareas,farmhouseholdsowntwoorthreecowsonly,whichtheytakeoutinthemorningtograzetetheredattheedgeofthefields.Theyarebroughtbacktothefarmsintheevening.

Most livestockproductioninthecentralandnorthernpartsof thecountryiscarriedoutbyFulaniwholookaftertheirownanimals(accountingformorethan50%ofthetotalcattlepopulation)orarehiredtolookafteranimalsthatbelongtootherpeople.TheFulaniinBeninarerelativelysedentary,butmakebriefseasonalmigrationsleavingtheoldpeopleandafewcowsthathaverecentlycalvedattheirwintercamp,whichisnevermoved.

InBorgouProvince,theherdsarebroughtineveryeveningandindividualanimalsaretetheredinacirculararrangementnearthecamp.Thecalvesaretetheredinthecentreandthecowsontheoutside,withthebullsleftfree.Thecowsaremilkedtwiceaday.

Sombafarmersinthenortheastkeepcattleinsmallfamilyherds.Theyareherdedduringthecroppingseason,butaftertheharvesttheyarelefttoroamfreely

Migratory livestock rearing Transhumancegenerallyoccursfromthesouthtothenorthandfromthewesttotheeast.Itisthepatternof regularmovement between areas according to the season determined by the nutritional need andhealthofthelivestock,andthesocialandeconomicneedsofthepastoralists.Herdsaremovedinsearchofgrazinglandandwater.

Transhumance takes place primarily towards the north–south ofBenin for two reasons: (i) cattlerearersinthenationareconcentratedmainlyinthenortherndepartments,especiallythezonesaroundBorgou,Alibori,AtacoraandDonga,whichaloneaccountfor85%ofnationalsupplyorabout1200000cattle;and(ii)sincethedroughtexperiencedinthe1970sand1980s,transhumanceofcattlefromthebordering countries (Niger,Nigeria,BurkinaFaso) increased significantlywith nearly 200 000 headofcattleand17000headofsheepfoundduringthe1994–1995dryseason).Transhumantherdersareconfrontedwithgrowingcompetitionforgrazingresources.

However,theagro-pastoralandpastoralproductionsystemsestablishedintheseregionsencouragedthemigratorylivestockfarmingsystem.Thelatterledtoaspacemanagementsystemcharacterizedbydaytimepastureandtwotypesoftranshumanceinparticular:

–shorttranshumancefortherainyperiod;–longtranshumanceduringthedryseasonforadurationofaboutsixmonths.ThereceptionzonesformigratingcattlerearersandtheirherdsareinCouffo,southernZou,northern

AtlantiqueandtheBonouplateau.Thereisathirdproductionsystem,inwhichcattlebelongingtoseveralownersarebroughttogether

inherdsand tendedbyhiredFulaniherdsmenunderpalm trees, coconut trees,on fallow landoronbushsavannah.Theseherdsaremilkedregularlyandthemilkismarketedinthetowns.TheanimalsarelargelyBorgou,andmanysufferfromstreptothricosis.

Some cattle breedsLagune Lagunecattlehaveacoatthatisusuallyblack,blackwithwhitespots,orblack-and-white.Redorred-and-white animals arevery rare.Themucosa, eyelids andhoofs areblack and the averageheight atwithersforasampleof17adultcowsrecordedbyStriffling(1977)was0.88m.

The calving rate of Laguna cattle kept under village conditions is only 35 to 45% (Heinemann,1963), while at Samiondji Station calving rate was 58% in 1976–77 (Lazic 1978). The Ministèredu Développement Rural et de l’Action Coopérative gave a calving rate of 70% for cross-breedingoperations ,which seems very high comparedwith the figures given in the other sources. For cross-breedingoperations,theMinistèreduDéveloppementRuralreportedmortalityratesof15%forcalvesuptooneyearand7%foradultanimals.AtSamiondjiStation,mortalityratesrecordedwere24%forcalvesuptooneyearand5%foradultcows(Lazic,1978).

Striffling(1977)reportedaveragebirthweightsof11kgfor8femalecalvesand10kgfor5males.Atsixmonthsbodyweightswere53kgforthesamegroupoffemalesand47kgforthemales.Theaverageweightofadultcowswas131kg.AverageweightsfordifferentagegroupsarepresentedinTable7.

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 21

A summary of the estimates of the mainproduction traits required for building up aproductivityindexcoveringthetotalweightofone-year-oldcalfplustheliveweightequivalentofmilkproduced per 100 kg of cowmaintained per yearof the Laguna cattle is presented inTable 8. Theproductivityindexwasderivedformeatproductionunder the conditions of Samiondji Station in amediumtsetsechallengearea.

Somba The Somba cattle are stocky animals with goodconformation formeat production in Benin. Theheightatwithersis0.90to1.00m,andthecoatisgenerallydark,eitheruniformlyblack,black-and-white, red-and-white or pied, usually with darkextremities(ILCA,1981).Averagemeasurementsfrom two surveys reported by Striffling, (1977);Domingo,(1976)arepresentedinTable9.

BorgouTheBorgouisacrossbreedbetweenWestAfricanZebu(mainWhiteFulaniZebu)andWestAfricanShorthorn.The coat is usuallywhite or grey, orsometimes black-and-white and the mucosa areusuallyblack.Heightatwithersrangesfrom1.05to1.20mamongadultanimals(Striffling,1977).These animals are much more docile than theLaguneorSomba.

Striffling (1977) reported a calving rate undervillage conditions of 54.5% in Borgou Province,compared with 73% for a sample of 14 cows atM’Bétécoucou Station. The calving rate variesconsiderablyaccordingtothedegreeoftrypanosomiasisinfestation.Lazic(1978)recordedacalvingrateatM’Bétécoucouofonly33%in1976/77.AtM’Bétécoucou,themortalityrateduring1976/77was28%forcalvesand12%foradultcows(Lazic,1978).TheaverageweightsofBorgoucattleatM’BétécoucouStations(a)and(b)arepresentedinTable10.

Averageweightsforadultanimalsrangearound250kg.Striffling(1977)recordedanaverageweightof244kgforasampleof81adultcowsundervillageconditionsand248kgforasampleof30adultcowsunderranchingconditions;whileLazic(1978)reportedanaverageweightof226kgfor73adultcowsatM’BétécoucouStation.AtOkparaFarm,anaverageweightof307kgwasrecordedin1974forasampleof43malesoverfiveyearsold(Strifflinget al.,1975).

Viaut(1966)recordedanaveragedressingoutpercentageof52%attheParakouabattoirfor24malesand8females.Theaverageliveweightofthemaleswas265kgandtheaveragecarcassweight137kg,whileforthefemalesaverageliveweightwas227kgandcarcassweight117kg.

Lazic(1978)summarizedestimatesofthemainproductiontraitsforBorgoucattleneededtobuildupaproductivityindexcoveringthetotalweightofone-year-oldcalfplusthelive-weightequivalentofmilkproducedper100kgofcowmaintainedperyear(seeTable11).TheproductivityindexderivedformeatproductionundertheseconditionswasalsoatM’BétécoucouStationinamediumtsetsechallengearea.

Pabli TheexistenceofaPablibreedintheKérouareanorthofKouandéinAtacoraProvincehasbeenmentionedbyseveralauthors(forexampleBrémaud,1967).However,theKérouareanorthofKouandéareaisnow

Table 7. Average weights for Lagune cattle Females Males

number kg number kg

Birth 16 9.5 17 106 months 11 47.0 9 4912 months 6 87.0 5 83Adults 51 152.0 - -

Source: Lazic, 1978

Table 8. Lagune productivity estimates Parameter Production

environment Station/medium challenge/meat

Cow viability (%) 95Calving (%) 58Calf viability to one year (%) 76Calf weight at one year (kg) 85Annual milked out yield (kg) -Productivity indexa per cow per year (kg) 38.4Cow weight (kg) 152Productivity indexa per 100 kg cow maintained per year (kg)

25.3

a. Total weight of one-year-old calf plus live weight equivalent of milk produced. Source: Lazic, 1978; ILCA, 1981

Table 9. Measurements from two samples of Somba cattle Parameters I IINumber of animals 36 76Sex and age adult cows over 5 yearsHeight at withers (m) 0.92 0.97Scapulo-ischial length (m) 1.05 1.20Heart girth (m) 1.30 1.37Body weight (kg) 149

Sources: For I, Striffling, (1977); for II, Domingo, (1976); cited in ILCA (1981).

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile22

populatedbytypicalBorgoucattle.ThePablihaseffectivelybeenabsorbedbytheBorgou.

CrossbreedsThere is great variety in appearance amongcrossbreeds in Benin depending on theoriginal breeds that were crossed and theproportions of each. There are no precisedata on the performance of the crossbreeds,buttheirvaluesaregenerallysimilartothoseobtainedforthebreedsthatwerecrossed.TheN’Dama breed was introduced on OkparaFarm near Parakou in Borgou Province andin the south at the SOBEPALH (SociétéBéninoise de Palmeraies d’Huile) palmplantationnearOuédoinAtlantiqueProvincefor crossbreeding purposes. There is littletraceofN’Damainfluenceinvillageherds.

The size of cattle herds depends on theownersandtheproductionsystememployed.Herdsinthesouthtendtobesmall,whilethoseinthenorth,particularlyinBorgouProvince,tend to average about 80 head (Striffling,1977).Typicalherdcompositionsforthetwomain livestock regions, Borgou andAtacoraProvinces,andforthesouth,wheretheherdsare chiefly composed of Lagune cattle, arepresentedinTable12.

Small ruminantsSheep and goats are owned by individualhouseholds and are generally kept in smallnumbers around the house. The animals ofa village are never brought together in oneflock.Mosthouseholdskeepsheepandgoatstogetherandhave two to fiveanimals inall.Theyarenotgivenanyveterinaryattentionorsupplementary feeding. The most importantdiseaseaffectingsmallruminants inBeninispeste des petits ruminants (PPR).Many ani-malssuffer fromhelminthiasis,whichmakesthemweakandmoresusceptibletoinfectiousdiseasessuchasPPR(Anon,2004).

SheepThesheepbreedsinBeninaretheSahelian(big)andtheGuineanorDjallonké(Small).MostofthesheepinBeninareoftheDjallonkébreed(Figure10).Guineansheeparesmall(Figure11);liveweightisrarelymorethan30kgbutwithahighqualityofmeatandyieldofabout48%.TheSaheliansheeparelargeandratherheavy(80kg).Theyarebutchershopanimals(40to50%ofyield).InthenorththerearealsoFulanisheepandcrossbredsbetweenthetwotypes.Sheepinthenorthtendtobebiggerthaninthesouth(Anon,2004).

Sheeparemoreorlessresistanttopestsbutverysensitivetothegastro-intestinalparasites.Therearemorethan1.7millionsmallruminantsinBenin,withapproximatelythesamenumberofsheepasgoatsforthecountryasawhole.

Table 10. Average weights of Borgou at M’Bétécoucou Stations Station (a)

Age Females Males

number kg number kg

Birth 15 16 26 176 months 16 66 18 8612 months 17 112 12 130

Station (b)

Age in months Females Males

number kg number kg

Birth 26 15.6 29 16.46 19 71.5 19 90.912 17 116.7 11 125.918 13 151.7 10 163.624 9 206.7 9 199.536 2 197.0 3 225.6

Source: Lazic, 1978 (a); Striffling (1977) (b); cited in ILCA (1981)

Table 11. Borgou productivity estimate Parameter Production

environment Station/medium challenge/meat

Cow viability (%) 88Calving (%) 33Calf viability to one year (%) 72Calf weight at one year (kg) 119Annual milked out yield (kg) -Productivity indexa per cow per year (kg) 30.1Cow weight (kg) 226Productivity indexa per 100 kg cow maintained per year (kg)

13.3

a. Total weight of one-year-old calf plus live-weight equivalent of milk produced. Source: Lazic (1978); cited in ILCA (1981)

Table 12. Herd composition in three areas (%) Borgou

Province Atacora Province

Southern Area

Male calves (< 1 year) 11.6 10.3 8Young bulls (1-3 years) 9.5 8.8 4Oxen and bulls 2.4 5.4 2 - 3.4 3Total males 23.5 27.9 17Female calves (< 1 year) 12.2 10.9 11Heifers 16.8 18.0 14Cows 47.5 43.2 58Total females 76.5 72.1 83

Sources: For Borgou and Atacora, (Striffling, 1977); for southern area, (Brémaud, 1967, cited in ILCA 1981

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 23

InBorgouProvince there aremore sheep thangoats,while in Zou and Mono Provinces the sheep and goatpopulations are about equal. There aremore goats thansheepintheothersouthernprovincesandAtacoraProvince(Table13).Table14presentstheproductivityparametersofgoatsandsheep.

Arnaud(1977)quotedanannualbirthrateof1.74lambspereweover twoyearsat theLycéeAgricoledeSékou.The same author reported 10months as average age atfirstlambingundervillageconditionsandapproximately40%lambmortalityrate.Averageweightsforadultewesingoodconditionsrangedbetween20and25kg,andforadultramsbetween30and35kg.

Table 15 gives summarized estimates of the majorproduction traits required tobuildupaproductivity indexbasedonthetotalweightoffive-month-oldlambsproducedper 10 kg of ewe maintained per year. This productivityindexwasderived forproductionunder station conditionsinalowtomediumtsetsechallengearea.

GoatsGoats are the most numerous species after poultry inall agro-ecological zones in Benin or (in the savannaharea) sheep. Four types of goats, Long legged Sahelian(LLS),LongleggedfromNorth(LLN),Shortleggedbutnot dwarf (SLND) and Short legged dwarf like (SLD)(Figure12)arefound(Dossaet al.,2006)indicatingthatthegoats inBeninaremostlyof theWestAfricanDwarftype.Figure13showsgoatsunderatraditionalproductionsystem.Meatgoatsweighabout15to20kgbutlessthandairySaheliangoats thathaveanadultweightof35kg.Goats aremorepopular than sheep in theSouth and areimportant in livelihood strategies of rural people (Dossaet al.,2008).

Dossa et al. (2008) observed that the ownership ofgoats was higher (91%) than sheep (35%) because goats are not affected by any ethnic or culturalrestrictions.Goatsarealsoperceivedtobelessriskytoinvestincomparedtosheep.Womenrepresented71%of thekeepersofgoats inBeninRepublic.The results showed thatyoungerhouseholdmembersespeciallyyoungwomen(60%)aremorelikelytoownsmallruminants.Ownersofsmallruminantsarelesslikelytobeinvolvedinoff-farmactivitiesandwouldoftenhavenoaccesstocreditfacilities.Gender,ethnicityandperceptionofriskassociatedwithspeciesarethemajorfactorsaffectingpeople’schoiceofspecies.Theyalsoobserved thatgoatsoffer a strongopportunity fordevelopmentprograms to enhance

Table 13: Sheep and goats distribution by province Province Sheep Goats

Numbers % of National Total Numbers % of National Total

Borgou 367 500 41.7 284 000 33.5Atacora 165 000 18.7 199 000 23.4Zou 200 000 22.7 190 000 22.4Ouemé 60 000 6.8 73 000 8.6Atlantique 14 600 1.7 31 000 3.7Mono 74 000 8.4 71 000 8.4Total 881 100 100.0 848 000 100.0

Source: Service National de l’Elevage, (1977); cited in ILCA (1981)

Figure 10. Djallonke sheep breed in BeninSource: Gbangboche et al. (2005).

Figure 11. Guinean sheep breed in Benin Source: Anon (2004).

Table 14. Productivity parameters for goats and sheepParameters Goat Sheep

Weights at birth (kg) 1.2 2.1Weight at 90 day (g) 4.2 8.1Weights at 90 day (kg) 11.1 14.1Weighed productivity (kg) 5.3 9.7

Source: Anon (2004).

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile24

women’s economic autonomy and to empowerthem.Womenweremore inclined towardsgoatsthanmen.Thisisbecausegoatspresent lowriskininvestmentandareeasiertokeep.

They observed that there is a cultural biasagainstsheep insomeethnicgroups.However,thepotentialofsmallruminants,especiallygoats,as an effective and feasible way of enhancinglivelihoods of the resource-poor people is stillunder-exploited.

Kitchenwaste and herbage cut from fallowland are somemajor sources of feed for smallruminants, although sheep are often tethered

Table 15: Sheep productivity estimates Parameter Production

environment Station/low to

medium challenge Ewe viability (%) 95aLambing (%) 174Lamb viability to one year (%) 60Lamb weight at five months (kg) 11.5Productivity indexb per ewe per year (kg) 12.3Ewe weight (kg) 22.5Productivity indexb per 10 kg ewe maintained per year (kg)

5.5

a. Estimate, b Total weight of five-month-old lamb produced. Source: Arnaud, (1977); information from country visits (Cited in ILCA(1981).

Long legged from the NorthShort legged dwarf-like

Short legged but not dwarf Long legged from Sahelian countries

Figure 12. Four types of goats in BeninSource: Dossa et al., 2006

Figure 13. Goats under traditional production systemSource: Anon (2004) ILRI

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 25

andgrazed.Peste des petits ruminants (PPR)appearedtobeamajorcauseofsmallruminantmortality.Constraints were identified relating both to the system of production and to the socio-economicenvironment.The former includeddisease, feedscarcity, lackofwaterandhousing.Socio-economicconstraintsincludedaninadequateextensionserviceandlivestocktheft.Managementpracticesusedforsmallruminantsaretraditionalandimproved(confinement).

5. THE PASTURE RESOURCE

Natural pasture Naturalpasture is the feedofalmostall ruminant livestock inBenin; thevegetation typeshavebeendescribedabove.Thecountryiscoveredwithdensevegetation.Mostpastoralistsgrazetheirherdsonseasonalpasturelands(Brottem,2006).Themainfeedsourcesavailabletograzinganimalsarenaturalpasture,cutforagefromforests,someadditionalfodderandcropresidues.

Thepresenceof the grassAndropogon gayanus, and the dicotyledons Indigofera secundiflora (inAtacora)andChromolaena odorata(inSavè)arerecognizedasindicatorsoffertilesoil,whereasHyptisspp.,Striga hermonthica andSpermacoce filifolia (inAtacora) indicate infertile soils (Vissoh et al.,2004;Saïdouet al.,2004).

Oloulotanet al.(2008)investigatedtheproductivityofnativegrasslandsinNikki-Kalale(northestern)Beninandobservedthatshrubbysavannahsaregrazed63to69%moreofthegrazingtimeindryseasonperiodwhile fallowsaregrazed60% in the rainy season.Shrubby fallowand savannahsare equallygrazedatthebeginningofJuly.FallowsonhumidsoilsinJunehadacarpetwith80%ofgrasses;and78%of grasses areBrachiaria falcifera,Schedonnarduspaniculatus andHyparrhenia diplandra.AttheendofMay,thebiomasswas685.2kg/haandhasacarryingcapacityof3.1ha/animal,dominatedby Imperata cylindrica,Brachiaria falcifera,Paspalum sp,Dactyloctenium aegyptium andDigitaria horizontalis. InAugust, itwas 4 964 kg/ha.They concluded that fodder production inNikki-Kalalegrasslands regularlygrowsandrangedfrom1.98 tonnes/ha inMay to12.4 tonnes/ha inAugustwithrespective carrying capacities of 2.6 ha/beast and 0.73 ha/beast. Finally the productionwas slightlydependantonsitesandsoil types,while thecarryingcapacityof theareawashighand it requiredareductionof104133beastsforajudiciousexploitationofthetargetedpastures.Theyconcludedthatrotationof thepastures, sedentarybreeding and judicioususeof bush fires shouldbe alternatives toimprovethepastureproductivityinNikki-Kalale(northestern)Benin.

Kreis et al. (2008) investigated the contribution of the agropastoral areas of the department ofBorgou: districts ofKalalé andNikki and reported that fallowswere dominatedby the grasses suchasPennisetum polystachion,Digitaria horizontalis (60% of recovery in the young fallow and 90%in the old one). Ledermanniella ledermannii, Diheteropogon amplectens and Andropogon gayanusdominated savannahs whereas Sargassum brevifolium, Andropogon pseudapricus and Hyparrhenia diplandracharacterizeddepressions.Thepastoralvaluesofbothdistrictsrangedfrom35to60%.Thehollow formations (savannahs and fallow) aswell as the old fallow (>5 years) on summits showedthatthehighestpastoralvalueoftheserieswas54.5–59.4%withagreatercontributionofgrassesandnon-fodderspecies(49to78%).Theoptimalpastoralvaluevariesandrangedfrom0.5to0.88whichindicatedadequateuseofavailablepasturesinthedistricts.Theyobservedthatforthewholedominantspecies,availableenergyfromfodderspeciesfortheproductionofmilk,contentsofdigestibleproteinsofthesmall intestinepermittedbyenergyandthosebynitrogendecreasedalongtheactiveperiodofvegetation.Thedecreasewasmore forSchyzachirium exile, andPennisetum polystachion fallowbuthigherintheyoungfallow.ToimprovethepastoralvalueofthefallowofP. polystachiontheysuggestedthat it was important to have leguminous plants to maintain a judicious sustainable exploitation ofavailablepasture.

HouéhanouandHouinato(2006)studiedpastoralmanagementandtheroleofgalactogenicwoodyspeciessavedinthefieldsfordairyproductionandtheeffectofAfzelia africanaonthequantityand

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile26

thequalityofmilk.TheyreportedthatAfzelia africana wasrecognizedby70%ofherdersasafodderfavouredfordairyproduction.Afzelia africanafodderappearedtobethepreferredalternativebyPeulhinthedryseasonasafeedforherbivores.Afzelia africanawasmoresoughtthanotherfodder.Sinsin(1993)investigatedsomesoilfactorsandgrassland-typerelationshipsinthesubhumidzoneofnorthernBenin.AlsoLejolyandSinsin(1993) investigatedfodderspeciescomposition,productivity, feedandgrazingvaluesofPennisetum polystachionpastureutilizedinnorthern-Beninforgrazing.

Aschfalket al. (2000) tested leaves from10 selectedWestAfrican trees and shrubswithvaryingtannin contents to determine their suitability as an alternative and supplementary browse feed toimproveproductivityofWestAfricandwarfsheepinsmall-scaleholdingsinBeninandobservedthatdrymatterintakeperkgmetabolicbodyweight(DMg/kgW0.75)variedbetweenthedifferentbrowsesandbetweenthedifferenttrialsandrangedfromzero(Leucaena leucocephala)upto26.7DMg/kgW0.75

(Margaritaria discoidea).Thedigestibilityoftheorganicmatteralsovariedbetween58.9%(Leucaena leucocephala)and68.2%(Mallotus oppositifolius).Agelaea obliquashowedthehighestlevelsoftotalphenols(10.2%),tanninphenols(8.8%)andextractablecondensedtannins(8.0%).Leavesfrombrowseswereagoodandprotein-richsupplementaryfodderinadditiontothegrassPanicum maximumforsheep,butitwasconcludedthatfeedingofCnestis ferrugineashouldbeavoidedduetotoxiccomponents.

Cultivated foragesPasture production is traditionally unknown in Benin Republic, but forage cultivation is done onnational farms (Gruber, 2008). Cultivated fodders have been experimented with but are of littleimportanceinsmallholderstockrearing.ThereareanumberofgrassandlegumesspeciesinBenintosupport the nutrition of ruminant livestock. Some commonpastures grasses and legume species andplant-communities are: Guinea grass (Panicum maximum); Elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum),Brachiaria ruziziensis, Andropogon gayanus and Hyparrhenia; Stylosanthes guianensis, Pueraria phaseoloides,Mucuna pruriens, andCentrosema. Feeding themas single feedor asmixtures servesasfeedresourcesforruminantanimals. Earlyintherainyseason,Brachiaria ruziziensis andPanicum maximum arethemostcommonforagegrassesgrazedbymostanimals.

Kindomihou et al. (2006) subjected five tropical grass species (Andropogon gayanus var.bisquamulatus, Elymandra androphila, Hyparrhenia subplumosa, Panicum maximum var. C1 andPanicum maximumvar. local) tovariousclipping treatments toexaminewhether silicaconcentrationcorrelatedtootherleafstructuralandchemicalparametersinBeninRepublicandfoundthatdefoliationincreasedsilicaconcentrationinthreeoffivespecies(bladesandsheaths),buttheresponsewasrarelystrong and varied with clipping frequency. Defoliation also caused other changes in leaf structure,suchasproductionofleaveswithjuvenilecharactersincludinghigherspecificleafarea(SLA),higherrelativewatercontent(RWC)andlowercarbonconcentration.Dataobtainedsuggestedthatenhancedsilicaaccumulationwasnotaveryspecific response todefoliation.Furthermore, silicaconcentrationwasobserved tovary among species andwas correlated to leaf structure and chemical composition.Andropogon gayanus var. bisquamulatus had the lowest silica concentration and the highest carbonconcentration, whilePanicum maximum showed the opposite combination of traits, suggesting thatspecieswithmoresclerifiedleavesmightbelesssilicified.Positivecorrelationsbetweensilicacontentand RWC, soluble ash and SLA suggest that variation in silica accumulation among species andtreatmentsmightberelatedtotranspirationrate.

Gafari and Adandedjan (2008) carried out agronomic evaluation of several fodder ecotypes inBeninthatconsistedof23species(7grasses;11herbaceouslegumesand5woodylegumes)inphaseof establishment onOkapara ranch, and 19 species (7 grasses; 8 herbaceous legumes and 4woodyleguminousspecies)inphaseofproductionofbiomassonCalavifarmandobservedthatsoilcoverratevariesfromonespeciestoanotherandthisincreasesastheplantgrowsinage.Forthegrassspecies,it ranged from11% to79.5%,exceeding50%at theendof theestablishment (12weeks)except forBrachiaria brizantha6780 (38%)whilePanicum maximum673showed thehighest rate (79.5%).P.maximum 673,Andropogon gayanus Samiondji andBrachiaria ruziziensis hadhigher recovery rates(>70%). Species at average recovery rates (50–70%) were Andropogon gayanus 621, Brachiaria dictyoneura,andBrachiaria decumbens whilethespeciesatlowrecoveryrate(<40%)wasBrachiaria brizanthaMarandu.Thespeedatwhichthespeciescolonizethesoilwascategorizedintotwogroups

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile 27

(i)reportA>25%hadBrachiaria ruziziensis(28%);while(ii)reportA<15%werePanicum maximum 673,Andropogon gayanusSamiondji,Brachiaria brizantha6780,Brachiaria decumbens,Andropogon. gayanus621,Brachiaria dictyoneura.

Forherbaceouslegumes,thecoverraterangedfrom31to97%,withanaverageratehigherthan50%exceptforArachispintoï(44%).Mucuna utilisshowedthehighestvalue(98.7%).Periodofmeasurementandspecieswerehighlysignificant.Alsotheaveragerecoveryratewasbetterwithleguminousspecies(73%) than grasses (63.7%). Vigorous species at high cover rates were distinguished from the leastvigorous:(i)recoveryratewashigherthan58%(Mucuna utilis:70.7%;andDolichos lablab58.5%);(ii)recoveryratelowerthan40%( Aeschynomenehistrix:38%;Centrosemabrasilianum:35.1%;Stylosanthes hamata:33.5%;Stylosanthes guianensis136:32.5%;Centrosema macrocarpum5452:27.7%).

Theydistinguishedthreegroupswithintheleguminousspecies:(i)reportA>25%:Mucuna.utilis(31.2%);(ii)A<15% report:Stylosanthes guianensis 136,Centrosema macrocarpum 5452,Centrosema brasilianum,Aeschynomene histrix;(iii)A>15%wereDolichos lablab(18.8%)Stylosanthes hamata(17.9%).

Forwoody leguminous species, they observed that the height of growth variedwith species andincreasedwithage.Thisrangedfrom20.5to101.7cmwithanaverageof41.7cm.AmongthewoodylegumesCajanus cajanshowedhighervalue(>101cm),whileFlemingia macrophyllaat21cmwasthelowest.Theyalsoobservedthattheaerialbiomassproductivityvariedwithspeciesandage.Biomassproductivity of Brachiaria dictyoneura Lanero, and Brachiaria humidicola increased quickly andexceeded4 605kg/ha at the endof establishment (12weeks)whilePanicum maximum 673 at 23%had lowbiomassproduction from the sixth to theninthweekbut reached5380kg/haat theendofestablishment.Brachiaria brizanthalaLibertad(980–1969kg/ha),Brachiaria brizanthaMarandu(890–2643kg/ha)andPanicum maximumT58(1042–2545kg/ha)werealsolowinbiomassproductivity.

Herbaceouslegumesshowedanaverageproductivityof2470kg/haasagainst3460kg/haforgrasses.Herbaceouslegumesweresubdividedinto2groups:(i)moreproductiveand(ii)leastproductive.Themore productive specieswereStylosantheshamata: (2 551 kg/ha);Centrosemamacrocarpum 5 452and Centrosema macrocarpum 5 713 (2 452 kg/ha), while the least productive were Stylosanthescapitata:(1528kg/ha);Centrosema pubescens:(1420kg/ha);Stylosanthessympodialis(1296kg/ha);Centrosema acutifoliumVichada:(1007kg/ha)andCentrosema acutifolium:980kg/ha).

Thewoody leguminousspeciesshowedavariation from900 to2991kg/ha from6 to12weeks,with theLeucaena leucocephala was themoreproductivewithvalues that rangedbetween1059 to2991kghawhilethelowestwasFlemingia macrophyllaatbetween1263to1469kg/hafromthe6thto9thweek,anddecreasedto985kg/hainthe12thweek.

Babatounde et al. (2008) investigated the grazing behaviour and fattening performances of 12DjallonkesheepontwoplotsofpasturecontainingeitherAndropogon gayanus+Aeschynomene histrix(M1)orPanicum maximumvar.C1+Aeschynomene histrix(M2)duringtherainyseason(July,AugustandSeptember)andwasrepeatedduringthedryseason(OctoberandNovember).Theyobservedthatin the pasture, the proportions of the time used by the various diurnal activitieswere distributed asfollows:64to85%forgrazing,3to12%perdayforruminationandfrom11tothe25%perdayforrestingtime.Acleardifferencewasobservedbetweentheperiodsoftimededicatedtograzingactivitiesduringthemorningandtheafternoon.Thetime%agedevotedtograzingisnotsignificantlyinfluencedbytheseason(p>0.05).TheyobservedthatseasonhadnoinfluenceonruminationortherestingtimewhenthesheepgrazeanM1mixture.Onthecontrary,withtheM2mixture,thesheeprestedmoreintheafternoons,especiallyatthebeginningofthedryseason.Voluntaryintakevariedbetween31and79gDM/kgLW.ThehighestvalueswereregisteredduringtherainyseasonandtheanimalsoperatedaselectioninfavourofAeschynomene histrixwithregardtograss.Theforageenergyconcentrationvariedbetween0.73and0.84UF(unitéfourragère–obsolescentfeedunit)andbetween0.79and0.89UF.TheproportionDCP/UFvariedbetween140and150g/kgofDMforM1mixtureandbetween75and140g/kgofDMforM2.Thesedietsallowedforagefatteningperformanceof50g/day/animal.

GrassesThemajorcultivatedfoddersaregrasses.SomeprominentgrassandfodderspeciessuchasGuineagrass(Panicum maximum),Elephantgrass(Pennisetum purpureum)andHyparrhenia rufa amongothers areavailableinBenin.

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profile28

Guinea grass (Panicum maximum)Panicum maximumisaperennialgrass(Figure14)nativetoBeninthatiswelleatenbyallclassesofgrazing livestock, with particularly high intakesof young leafy growth. It is ideal for cut-and-carryandhighlysuitedtogrowingwithtreesandshrubs due to its shade tolerance. Reasonablypalatablewhenmature, providinggood roughageforuseinconjunctionwithfoliageofbrowsesandmultipurposetrees.Itcombineswellwithtwininglegumes under light grazing. It spreads alongwatercoursesandungrazedroadsides.

Elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum)Elephant orNapier grass (Pennisetum purpureum)is native to tropical Africa but is now availablethroughout the tropics (Figure 15). It is a tall,clumped perennial that is planted in some placesonbundsas awindbreakand to conserve the soil.Althoughthedrystemsorcanesareusedforfenc-ingandforhousewallsandceilings,itisprimarilygrown for fodder. It is a very suitable fodder in acut-and-carryproductionsystem.ElephantorNapiergrasscangrowinmixturewithlegumes.Ithasbeenobserved that when it is intercropped with herba-ceouslegumes,cuttingorgrazingmanagementcanbeadjustedtofavourthelegumesinordertomain-tainasatisfactorymixedsward.Elephantgrasscanalsobegrownasanalleycropwithfodderlegumessuch as Leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala), calli-andra (Calliandra calothyrsus), sesbania (Sesbania sesban)andgliricidia(Gliricidia sepium).

AndropogongayanusisfoundonsandysoilsinBeninwhileHyparrhenia rufaisfoundinmoistersitesinBenin(PeyredeFabrègues1980).