contents - Open Magazine

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of contents - Open Magazine

www.openthemagazine.com 32 november 2020

contents2 november 2020

12

THe InSIDer By PR Ramesh

18

OPINIONLeft, right and

nowhereBy Minhaz Merchant

20

WHISPERERBy Jayanta Ghosal

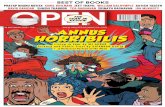

Cover by Saurabh Singh

56

52

16

HoW ILL Is InDIA’s HeALtH sectoR?With government hospitals overburdened, bottomlines of private ones wiped out, and an insurance system that seems to be unable to wrap its head around the pandemic, Covid-19 has laid bare India’s health infrastructureBy Lhendup G Bhutia

Be PAtIentBeing non-Covid patients in the time of a pandemicBy Nikita Doval

DoctoRs JUMPInG BoRDeRsWith the disruption in corporate hospitals, underpaid medical professionals and neighbourhood nursing homes are stepping into the breachBy V Shoba

PUNJABI RAPPolitical brinkmanship in Punjab has taken a dangerous turn after the farm reform laws By Siddharth Singh

LETTER FROM LAHORELand without small mercies By Mehr Tarar

28

34

38

44

48

16

ToUCHSToneAn American

folk taleBy Keerthik Sasidharan

14

InDIAn ACCenTSReimagining

the GitaBy Bibek Debroy

52

beHoLDen To THe FATHer FIGUre

Sofia Coppola on her departure from reflective character studies

By Rajeev Masand

56

‘THe TIDe IS SHIFTInG AWAY From mALe SUPremACY’

Parvathy on the Kerala film industryBy Ullekh NP

60

THe InvISIbLe oTHerWhat makes us who we are?

Increasingly in popular culture it is who we are opposed to

By Kaveree Bamzai

65

HoLLYWooD rePorTerEwan McGregor on his

new docu-series Long Way UpBy Noel de Souza

66

noT PeoPLe LIKe USA new beginning

By Rajeev Masand

5

LoComoTIFThe trial

then and nowBy S Prasannarajan

6

oPen DIArYBy Swapan Dasgupta

28

22

OPEN ESSAYMao against

NehruBy Iqbal Chand Malhotra

5

22

2 november 20204

waiting for deathMuch as we may yearn ‘to cease upon the midnight with no pain’, we may not really end up being fortunate enough when our turn comes (‘The Sense of an Ending’ by Arun Shourie, October 26th, 2020). Yama’s emissaries are not known to be kind nor do they come sequentially. So probably, we should remember the maxim that ‘preparedness is all’. Truly, being organised in death, as in life, is crucial to a peaceful end. Writing a will can indeed be liberating because it gives us a glimpse of our own end. Once we have our after-plan ready, we can, like passengers in a lounge, soak in the moment.

Sangeeta Kampani

tamil twistThe B JP has finally got a face to activate its cadre in Tamil Nadu for the electoral race (‘Getting It Right’ by By Maalan Narayanan, October 26th, 2020). The party’s plans to rope in Rajinikanth has not yielded any results as the actor chose to float his own party. Khushbu Sundar who could not shake the Congress much may be better placed in the BJP because the former party is in a shambles in the state. The BJP doesn’t have any history there and may strike a chord with the voters who are fed up of AIADMK’s and DMK’s shenanigans.Though Khushbu is no Jayalalithaa, she is no Sasikala either. She has a clean track record and

with the right backing of the BJP’s leaders, she could be the much needed alternative in Tamil Nadu politics. If the BJP doesn’t get it right this time, it will be a longwinding road ahead for them. With the current EPS adminstration’s poor performance and DMK’s MK Stalin, Kamal Haasan and Rajini still struggling to become relevant, Khushbu could be the real alternative Tamil voters are looking for. It’s now or never.

Ashok Goswami

Switching parties is a way of life in Tamil Nadu politics and actor Kushbu Sundar has perfected the art by now. She has had a lacklustre career in both the DMK and the Congress. Now, the BJP’s arrival on the Tamil scene has given her new opening and a third chance to turn into reality the part she has been dreaming of. Let us wait and watch how the BJP fares in the next Tamil Nadu elections and whether it is able to grow beyond elections. Whoever wins, party-hopper Kushbu is having a field day trying her political luck out again and again.

CK Jayanthimaniam

C letter of the week

Despite opposition parties being in disarray and Rashtriya Janata Dal founder Lalu Prasad serving

a prison term for a multi-crore fodder scam, the electoral fight in Bihar that looked like a onesided

affair at the beginning for the BJP-Janata Dal (United) combine has become tough as we near the voting dates

(‘Bihar 2020’, October 26th, 2020). The main reason is the poor performance of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar

over the past five years. If you look at the questions in the latest opinion survey also, you will see that

while people still prefer him to anyone else, they are also complaining about him individually, not the

coalition. That should give the BJP some hope. Nitish Kumar rose in Bihar politics as a whiff of fresh air

and promised to transform the state but got waylaid in between. He made prohibition his main plank

but that has not helped grow the economy of Bihar. Instead, the Bihar government is losing revenue to

both neighbouring states and smugglers. The LJP, the Congress and the RJD are full of discredited leaders. Nitish Kumar has become a shadow of himself and

his agenda of growth and development seems to have taken a backseat. It’s a sorry state of affairs where no

matter who wins—Lalu’s son Tejashwi or Nitish once again—Bihar ends up losing.

Bholey Bhardwaj

open mail

Editor S Prasannarajan managing Editor Pr rameshExEcutivE Editor ullekh nPEditor-at-largE Siddharth SinghdEPuty EditorS madhavankutty Pillai (mumbai Bureau chief), rahul Pandita, amita Shah, v Shoba (Bangalore), nandini naircrEativE dirEctor rohit chawlaart dirEctor Jyoti K SinghSEnior EditorS Sudeep Paul, lhendup gyatso Bhutia (mumbai), moinak mitra, nikita dovalaSSociatE Editor vijay K Soni (Web) aSSiStant Editor vipul vivekchiEf of graPhicS Saurabh Singh SEnior dESignErS anup Banerjee, veer Pal SinghPhoto Editor raul iranidEPuty Photo Editor ashish Sharma

national hEad-EvEntS and initiativES arpita Sachin ahujaavP (advErtiSing) rashmi lata Swarup gEnEral managErS (advErtiSing) uma Srinivasan (South)

national hEad-diStriBution and SalES ajay gupta rEgional hEadS-circulation d charles (South), melvin george (West), Basab ghosh (East)hEad-Production maneesh tyagiSEnior managEr (PrE-PrESS) Sharad tailangmanagEr-marKEting

Priya SinghchiEf dESignEr-marKEting champak Bhattacharjee

cfo & hEad-it anil Bisht

chiEf ExEcutivE & PuBliShErneeraja chawla

all rights reserved throughout the world. reproduction in any manner is prohibited. Editor: S Prasannarajan. Printed and published by neeraja chawla on behalf of the owner, open media network Pvt ltd. Printed at thomson Press india ltd, 18-35 milestone, delhi mathura road, faridabad-121007, (haryana). Published at 4, dda commercial complex, Panchsheel Park, new delhi-110017. Ph: (011) 48500500; fax: (011) 48500599

to subscribe, Whatsapp ‘openmag’ to 9999800012 or log on to www.openthemagazine.com or call our toll free number 1800 102 7510 or email at: [email protected] alliances, email [email protected] for advertising, email [email protected] any other queries/observations, email [email protected]

volume 12 issue 43for the week 27 october- 2 november 2020total no. of pages 68

disclaimer‘open avenues’ are advertiser-driven marketing initiatives and Open assumes no responsibility for content and the consequences of using products or services advertised in the magazine

www.openthemagazine.com 52 november 2020

efore 2020, there was 1968. then: the streets erupted in counter-cultural romance of what Le Monde called the “bored” generation. In Paris, they occupied universities and factories and invited Sartre for philosophical input—and old icons of communism

were worthy of being there on the wall and the placard. that was a time when capitalism and imperialism were synonyms for evil, a time when the guardian of Gallic essentialism, Charles de Gaulle, had to temporarily flee the republic. In the religion of protest, conscience conditioned by ideology was the only temple.

elsewhere, in the United States, it was a war and an assassination that brought dissent to the street. Vietnam was the wrong war for a generation angered by the extra-territorial terror of the imperium, and the foot soldiers dying in the faraway swamps and jungles of Vietnam mostly came from the working class and the Black community. the war was not unsolicited martyrdom; it was sacrifice to please the wrong god. then riots broke out after the assassination of rev Martin Luther King Jr. the republican candidate richard Nixon campaigned on the platform of law and order—and would win. And at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the “rioters” included hippies, pacifists and ideologues. one year later, in the beginning of the Nixon era, their ordeal would come to be known as the trial of the Chicago 7—the drama of youthful dissent and insensitive state staged in the backdrop of a culture war.

When you watch Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7, streaming on Netflix, in 2020, five decades after 1968, the distance in time is reduced by the mythology of protest, its morals and methods. the culture war is back, with the progressives in righteous rage set against the state without justice. then it was the assassination of King that set the street on fire; in 2020 it was the death of George floyd under the knee of a white policeman. then it was Nixon who extolled the virtues of the strong state (“We see cities enveloped in smoke and flame”); today there is a Donald trump, seeking re-election on law and order, to pull the presidential trigger, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.” the cultural divide was as sharp then as it is today, with the dictatorship of correctness enforcing its own taboos in public discourse. The Trial of the Chicago 7 should be watched as a memorial service and a moral rejoinder, which is also an explicit directorial demand.

And the director being Aaron

Sorkin, a courtroom drama becomes a verbal arena where the kinetic force of dialogues is matched by the moralism of the self-conscious idealist. As a scriptwriter and filmmaker (the repertoire includes The West Wing, The Newsroom and The Social Network), he is the polemicist of here-and-now, carrying within him an overabundance of headlines-driven rage. In The Trial, the dramatisation of moral crime and predetermined punishment parades the idealists, bigots and conspirators from the year that America believes it’s reliving today.

here they are. the hippies, Abbie hoffman and Jerry rubin, played with comic irreverence by Sacha Baron Cohen and Jeremy Strong (of Succession) respectively, come to the court one day dressed as judges, and hoffman never misses an opportunity to defy the system with some of Sorkin’s best lines. tom hayden (eddie redmayne), the ideologue, is a conflicted soul waiting for validation. he will have his moment, even if it’s at the expense of historical fact. rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John froines, and Lee Weiner complete the list of rebels accused of being the rioters of ’68. for a while they are joined by the Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), without legal representation. When he stands up for his rights, he is gagged and chained to his seat, and the scene provides the film’s most eloquent reminder that racial dehumanisation is a constant in America’s trials. the defence attorney William Kunstler (Mark rylance) argues with stoic restraint, and he is constantly undercut by the federal judge Julius hoffman, a looming tower of conservative partisanship and a ruthless wielder of contempt-of-court order, brilliantly played by frank Langella.

In the end, it doesn’t matter whether the judgment was custom-made for Nixon’s “spoiled rotten”. It doesn’t matter whether the seven would be acquitted by a higher court. It also doesn’t matter whether we all along knew that the riot was instigated not by the seven but the cops who put their badges inside their pockets before charging. What we are meant to know is that The Trial of the Chicago 7, even if we shuffle the text and context, retains its message in the age of angry streets and a president worse than Nixon. We are meant to remember that our conscience is still on trial in a world where the lies of the state continue to borrow from history.

the post-credits question is: What does it take for a filmmaker or a writer to let polemics and pedagogy diminish his art for the sake of social, cultural and ideological obligations? n

B

LOCOMOTIF

by S PRASANNARAJAN

THE TRIAL THEN AND NOW

The Trial of the Chicago 7

2 november 20206

For a Few days or maybe a week at most, a large section of

the social media behaved as if the most important thing in India—after Covid—was an advertisement issued by the makers of Tanishq jewel-lery. There were spirited exchanges between those who described the ad-vertisement as a sensitive portrayal of the togetherness of India and those who believed—equally sincerely— that, behind the touching portrayal of multi-religious accommodation, this was nothing but a justification of ‘love jihad’. The furore was signifi-cant enough for the Tata company to withdraw the advertisement and the share price of the company took a hit as a boycott campaign was launched by those who were outraged.

what is striking is that the opinions on the Tanishq advertise-ment differed significantly according to class. For much of upper-middle class, cosmopolitan India, there was nothing strange about a Muslim boy marrying a Hindu girl and his family accommodating the girl’s customs as much as possible. In our social life, we know of many inter-faith marriages where there is no question of conver-sion. The more complex question of what faith the children should fol-low—if they are not to be atheists—is, of course, left unaddressed.

slightly lower down the social ladder, ‘love jihad’ is a touchy issue. There is, in any case, an innate conservatism of families that fear the free social interaction of the sexes. on top of that, the bush telegraph suggests that Muslim boys are somehow adept at enticing Hindu girls into a relationship and then securing their conversion to Islam. The fear is always centred on the intentions of Muslim boys. The question of Hindu boys striking up a

relationship with Muslim girls is again left unaddressed. anyway, this section strongly felt that the portrayal of Muslim open-mindedness was an eyewash and that as far as their experience suggested, the Muslim community was never going to accept multiplicity of faith. They will point to the horrible predica-ment of Hindu and sikh minorities in Pakistan and the familiar tales of conversions to Islam.

In a facile article that seems to be the hallmark of the foreign media in India, it was suggested in Financial Times that this intolerance is a feature of post-2014 India and that Narendra Modi’s victories have narrowed the Hindu mind. This is complete hogwash. I recall in my youth being told by kindly relatives that we could marry anyone suit-able, but never a Muslim. despite the shuddhi Movement of the arya samaj in the late-19th century, most Hindus didn’t factor in the possi-bilities of conversions to Hinduism. Conversion was always regarded as a one-way street—from the Hindu faith to Islam. This was seen to be as true for Hindu boys who married Muslim girls as it was for Hindu girls wedding Muslim men.

It is for historians and sociologists to provide credible explanations of what lay behind such attitudes. However, before the faultlines are

debunked under the all-embracing category ‘prejudice’, it is worth reflecting on what creates prejudice. I am often reminded of why edmund Burke, often described as the archi-tect of modern conservatism, never considered prejudice to be a pejora-tive term. To Burke, prejudice was invariably the outcome of accumu-lated experiences which have been passed down the generations. To him, prejudice was always based on uncodified knowledge. Being devoid of prejudice involves being socialised in a very different ecosystem—a rea-son why cosmopolitan India saw the Tanishq advertisement in a different light from Middle India.

However, there are exceptions. My grandfather’s sister was a feisty lady. she secured a doctorate from Heidelberg in the 1930s, became a trade unionist on her return and earned considerable fame—and notoriety—as the leader of sweepers employed by the Calcutta Corpora-tion. within the family she was regarded with both awe and dread.

My grandaunt did something that was unusual, even by her eccentric standards: she married a Muslim. If she was a battle axe, Mirza sahib—as he was known in the family—was quite the opposite. a refined, highly educated scion of a Hyderabad family, he was soft-spoken and well liked by everyone. He had a distin-guished career as a diplomat and a politician. There was no question of my grandaunt changing her religion. Indeed, after marriage, she gave up activism and became a devout Kali worshipper, doing puja each day in a flaming red sari.

Her life didn’t reshape the notion of prejudice in our family. But we adored Mirza sahib and regarded my grandaunt as totally bonkers. n

Swapan Dasguptaopen diary

Available as an e-magazine for tablets, mobiles and desktops via Magzter

openthemagazine

To subscribe, ‘openmag’ to 9999800012

openthemag

www.openthemagazine.com

Pick up and subscribe your copy today

Read

[ No one makes an argument better than us ]

“THE NATION IS EVOLVING AND

SO ARE YOU" OPEN brings to you, your weekly

thought stimulant

2 november 20208

On Monday, october 19th, in a not alto-gether unanticipated decision, the Indian defence establishment abandoned its self-restraint, or rather self-imposed restraint, to invite australia to the 2020

Malabar exercises with itself, the US and Japan. the absence of surprise didn’t entail a lack of optimism, or even euphoria in some quarters. In the mix of the tangible and the symbolic, the latter usually has the first say and australia’s ‘return’ to the Quadrilateral Security dialogue (Quad) is as symbolic as it reconfigures the Quad’s raison d’être. Malabar, of course, is not held under the auspices of the Quad but the forum can finally live up to its name. and it was now or never.

the Quad had disintegrated in 2008 when Kevin rudd’s Labor administration had pulled australia out and enthusiasm had waned in both Japan—with Shinzo abe, whose brainchild it had been, leaving office in September 2007—and India—where the UPa Government, with its overcautious defence minister, bent over backwards to stay out of china’s way. In the years that followed, two, not unrelated, geopolitical develop-ments had progressed simultaneously. china’s continued economic rise with the attendant, now overtly prioritised, military modernisation and the growing defence and strategic closeness between new delhi and Washington.

the fear of an angry china had afflicted not merely South block. china had protested vehemently when the double Malabar of 2007 had expanded to include australia and Singapore. In the end, the chinese had won both ways. rory Medcalf, strategic expert and head of national Secu-rity college at the australian na-tional University, recently wrote in Australian Foreign Affairs: ‘the main criticism of the Quad back then was that it would needlessly provoke china down a perilous path of military modernisation and destabilising behaviour. yet beijing chose such a road anyway. the perils the Quad’s critics thought it would invoke ended up arising in its absence (emphasis

added). the next decade brought such geopolitical instability that the four governments became convinced their disbanded dialogue had been an idea ahead of its time.’

In the autumn of 2020 going on winter, china has risen from the beating it initially took over the pandemic to revel in military aggression and aggressive posturing brazen by even the People’s republic’s (Prc) standards since the time of the chairman. after the summer of bloodshed in the himalayas with the Indian military, President Xi Jinping has given a call for war-readiness to the People’s Liberation army (PLa) and reportedly the Prc is seri-ously planning an invasion of taiwan, or at least that’s the mes-sage it’s intent on conveying. In a retaliatory diplomatic measure following up on the dragged-out but still unfinished trade war, the US has appointed a special coordinator for tibetan issues. the irony of the situation is that, having evidently got several things wrong at home and abroad, the trump administration got two things obviously right—china and the Quad—among certain other things it most likely got right in foreign policy and geopolitics. (It’s more than just a joke that covid-19, originating in Wuhan and then damaging donald trump, the first US Presi-dent to put real roadblocks on beijing’s long and quick march to global supremacy, has been a windfall for the Party.)

It was the trump administration that in 2017 had helped begin the resurrection of the Quad. this had perfectly dove-

tailed with new delhi, with a new Government in office, by then having realised that staying out of beijing’s way only embold-ened the Prc and made it take you for granted. rather, greater proximity to Washington would squeeze beijing at one end and make it more amenable to dia-logue at the other. It worked to an extent where china went into a mode of alternating between dismissing the US-India partner-ship and raising its protest pitch. all the time, the border face-offs went on as did china’s continued efforts to block India from export control regimes like the nuclear Suppliers Group. by the time an

openingsThe Return of the Quad

NOTEBOOK

Australia rejoins Malabar and Delhi, by rights, will practise its

minilateralism within and without the Quad. But

sometime in the near future, it may want to note that alliances are not commitments till death

do nations part. They are also functional tools to

realise mutual goals with likeminded partners

2 november 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 9

angry India, in the fall of 2020, invited australia to Malabar, the die had been cast. the catalyst was the second ministerial meet of the Quad in tokyo earlier this month—a face-to-face, physi-cal meeting despite the pandemic—where mutual interest and intent converged with all eyes on the clock.

Medcalf tells Open: “It was worth the wait. australia’s inclusion in the 2020 Malabar naval exercise is a confirma-tion of the logic of practical Indo-Pacific security cooperation centred on the Quad. For many years now it has been clear that these four countries offer an exceptional convergence of strategic interests, competent capabilities, mutual respect for a rules-based order and willingness to work together. china and its affronts to regional order provided the final glue, making manifest the pre-existing alignment of interest among the four.” as neatly as that sums up the resurrection of the Quad, what has changed in delhi can’t be reduced to the post-Galwan heat. the message, despite attempts to mute it, is quite clear: India’s counter-aggression vis-à-vis china now officially spans land and sea, from Ladakh to the Indo-Pacific, notwithstanding delhi’s communiqué that the Quad should not be conflated with the Indo-Pacific. the truth, or what one hopes is the truth, should be that the immediate end here is cutting off the Straits of Malacca from the PLa navy whenever the need arises.

each of the four members of the Quad is in beijing’s crosshairs. but the fact is that the Quad is not the only strategic forum of its kind in the Indo-Pacific. While the idea was to ex-pand it to include the UK and France—an idea that may yet see the light of day given Japan’s permanent membership in Mala-bar since 2015 and now australia’s return—there are already at least two trilaterals that have surfaced in the region: a for-malised broad-issue forum involving India, australia and Indo-

nesia and a less formalised maritime exercise and exploration trilateral among India, australia and France. as Medcalf points out, there’s also the ‘less famous quadrilateral’ of australia, new Zealand, the US and France in the South Pacific. the Quad, in fact, may now scale things up and broaden its horizons, taking a leaf out of the South Pacific diplomatic quadrilateral’s book. Medcalf says: “after this, the Quad won’t look back, and we are likely to see collaboration broaden across other domains like supply-chain resilience, cyber security and coordination of diplomatic efforts in multilateral organisations.”

the question, for the others though, would inevitably return to India. Soon after the announcement on october 19th, abc journalist Siobhan heanue tweeted: ‘australia joining ex Malabar is significant - but it is India that will make or break the Quad.’ delhi has been more driven and seemingly determined than ever in reviving the Quad but it apparently remains the weak link. Japan and australia are both alliance partners of the US. India is not likely to be one in the foresee-able future, especially given the persistence of apathy towards the idea of big-time alliances in South block. delhi, by rights, will practise its minilateralism within and without the Quad but sometime in the near future it may want to sit up and note that alliances are not commitments till death do nations part. they are also functional tools to realise mutual goals with likeminded parties. china has forged and broken alliances with one and all, often based on single, extremely short-term objectives. From where delhi looks at the world, it will not find ‘big’ countries, with a stake in its maritime neighbourhood, more likeminded than its three partners in the Quad. n

By sudeep paul

I l lustration by SauraBh SiNgh

2 november 2020

openings

For fans of Tamil cinema, the name Prem evokes not a salman Khan character, but the 2012 film Naduvula Konjam Pakkatha Kaanum,

in which the lead played by actor Vijay sethupathi loses his memory after sustaining a small injury playing cricket with his friends. “I tripped and fell. I got hurt here... that is where the medulla oblongata is. The shock must have resulted in short-term memory loss. It’s ok, it will come back on its own,” Prem assures himself, in words that every fan of the actor has committed to memory. sethupathi, 42, would have played cricket again onscreen, por-traying one of the greatest cricketers of all time, sri Lankan offspin legend Muttiah Muralitharan. Cast in a biopic named 800—after the number of Test wickets Muralitharan has to his name—sethupathi had announced the project in early october, only to be browbeaten into withdrawing from it within a couple of weeks. The opposition came from a section of Tamil society that feels betrayed by Muralitharan’s politics. a Tamil who grew up in sri Lanka during the civil war, Muralitharan is accused of disclaim-ing his ancestry and siding with the Mahinda rajapaksa government that oversaw the genocide of Tamils in the country. “Muralitharan is an example for achievers in cricket and a historically important figure. But his political posturing and alleged identity swaps are controversial and cannot escape a portrayal in his biopic,” says Maravanpulavu K sachithananthan, a Hindu Tamil activist in sri Lanka. as detractors took to social media and urged the star to back out of the project, sensible voices condemned the slurs and a rape threat directed at his daughter. The backlash finally prompted Muralithar-an, who is coaching bowlers of sunrisers Hyderabad for the Indian Premier

League season underway in the UaE, to issue a statement asking the actor to quit for the sake of his own safety and image.

“When I spoke to him, sethupathi seemed unaware of the political purposes that a biopic on a problematic figure like Muralitharan could serve,” says V Gowthaman, a Chennai-based filmmaker, pro-Tamil activist and politician. “We have nothing against a film on Muralitharan. But it is being made in Tamil, with one of the most loved stars of Tamil cinema playing the character. It cannot be seen as just art—if the film comes out and sethupathi becomes a tool in the hands of an anti-Tamil establishment to promote a hero who toes their line, it will hurt Tamil sentiment no end,” he says. Muralitharan has put out statements clarifying that the film is intended to inspire a generation of upcoming cricketers. He has also claimed affiliation with the Tamil plantation workers in sri Lanka and said that his father and relatives lost their lives to the ethnic conflict. “The Tamil identity issue still rages in sri Lanka, and an actor of sethupathi’s stature should not be seen to endorse a man who has never before empathised with his own people,” Gowthaman says.

The sobriquet of ‘Makkal selvan’ (People’s Man) has stuck to sethupathi since director seenu ramasamy popularised it ahead of the release of his film Dharma Durai (2016). a rare actor in Tamil cinema who trespassed several boundaries, including the one between the commercial and the indie worlds, Vijay sethupathi had a late start—after a career as an accountant in Dubai—and one that coincided with a new wave in the industry. Character-centric films, like the crime comedy Soodhu Kavvum (2013), the nostalgia trip that was 96 (2018) and Super Deluxe (2019) where he plays a transgender, made him a darling of Tamil audiences.

sethupathi has, on occasion, spoken up against communal tension, fan wars and the abrogation of article 370. In an interview last year to SBS Tamil Australia, a radio channel, after winning the best actor award at the Indian film festival in Melbourne, he invoked Dravidian leader Periyar EV ramasamy and criticised the narendra Modi Government’s “anti-democratic” stand on Kashmir. His statements on the issue are rumoured to have come in the way of his bagging the Tamil nadu Government’s Kalaimamani award for excellence in art and literature.

Bowing out of 800, which could have won him an oscar nomination, is a personal setback for sethupathi the artist, but it has only reaffirmed his stature as the conscience-keeper of Tamil cinema. n

By V shoBa

bowled outThe Tamil star is browbeaten into withdrawing from a biopic on cricketer Muralitharan

portrait vijay Sethupathi

Courtesy KarthiK SrinivaSan

2 november 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 11

‘The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little’ Franklin D rooseveltformer us president

Word’S Worth

progreSSPope francis endorsing same-sex marriages has to be a dramatic moment for the Catholic Church, but it is also an inevitable one because that is the nature of civilisation’s progress. outdated values that seem ossified in stone in institutions find it difficult to withstand the self-evident ideas being accepted in the rest of the world. The present Pope, who was always known to be a liberal, was preceded by a hardliner. sustainable progress builds up gradually until it becomes conventional wisdom abruptly. Think of the sun going around the earth, a belief which the Church held for centuries. n

ideaS

ge

tt

y i

ma

ge

S

angLe

SoMETHInG so PoWErfUL that it controls access to your

consciousness itself, which knows more about you than you yourself, and can predict decisions that you are going to make even before it has crossed your mind, must be allowed into society with extreme caution. But the tech-nology and the companies that wield them came in almost without notice, making it seem as just a natural pro-gression of entrepreneurship. It clearly wasn’t. We see the signs of it all around, from appliances that hear every word you say to posts targeted so minutely to individuals that it can veer you to vote for a certain candidate in elections. online technology has encroached into areas no one predicted and yet the companies that own it don’t nearly get challenged enough about the power they wield. That might end by the Us government’s actions this week.

They filed an antitrust lawsuit that could potentially lead to Google being broken up because of, it said, too much influence that was used to prevent competition. as Reuters reported, ‘The U.s. sued Google on Tuesday, accusing the $1 trillion company of illegally us-ing its market muscle to hobble rivals in the biggest challenge to the power and influence of Big Tech in decades. The Justice Department lawsuit could lead to the break-up of an iconic company that has become all but synonymous with the internet and assumed a central role in the day-to-day lives of billions of people around the globe.’ Effectively, as a search engine, Google is a monopoly and the money it makes from that posi-

tion, makes it perpetuate the monopoly. While the case will take time for a verdict, should the government suc-ceed, the spillover to the other big tech companies is inevitable. social media, which defines modern existence, too might eventually get out of the strangle-hold of a handful of companies that exert extraordinary control over a large swathe of mankind.

There are no answers to what the alternative world will look like but the present everyone recognises is a calamity in progression. former Google CEo Eric schmidt who came in an online event of Wall Street Journal recently, said that they had not foreseen or intended ‘social net-works serving as amplifiers for idiots and crazy people…Unless the industry gets its act together in a really clever way, there will be regulation.’ But what did they intend then? To make vast profits by cap-turing attention at a scale never known before while ignoring secondary effects. It was through Google’s search engine money that they bought YouTube, the company’s social media cash cow.

now when the consequences are be-coming real, these companies are trying to plug holes in the Titanic with paper. spelt out in schmidt’s statement is also the next danger that these companies pose. once Google decides who are the ‘idiots and crazy people’, then anyone who does not meet their standard is essentially an outcaste in the neighbour-hood. and such powers and their abuse are limitless in scope. regulation might be bad for entrepreneurship but mo-nopolies that have appropriated godlike powers onto themselves are worse. n

The US government’s attempt signals recognition of the dangers of tech monopolies

By madhaVankutty pillai

Breaking Up google

2 november 202012

the insiderPR Ramesh

Chirag Paswan, who took over as Lok Janshakti Party (LJP) chief

after the death of his father Ram Vilas Paswan, might have chosen the over-the-top option of letting his audience see how dear he held Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his heart. Even as Chirag dropped out of the NDA in Bihar and chose to contest alone, vowing to oust Nitish Kumar and ring in a BJP chief minister, the BJP’s leadership—which launched a multi-pronged attack on him in both Delhi and Patna recently—is actually livid with him for the decision to walk out of the alliance. For sure, some blame Nitish and his refusal to share power and responsibility for Chirag’s decision.

But the BJP leadership believes that in offering 15 seats to the LJP and in suggesting that the Janata Dal-United, or JD(U), share 10 other seats with the LJP—a suggestion Nitish outright rejected—it did Chirag more than a favour. Consequently, it disapproves of what it sees as tantrums from the LJP leader, who is considered callow and politically untested by several people in the JD(U). Against this backdrop, a comfortable victory for the NDA in Bihar could mean curtains for Chirag Paswan. His party’s following could

well be up for grabs too. A big loss could also be prime real estate in New Delhi where Ram Vilas Paswan had

occupied a spacious residence on Janpath for years as

minister under various dispensations. The LJP,

which suffered a big dip in popularity among

its Dalit vote base with the advent of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), has been on the decline since 2005. In 2005, it won 10 Assembly seats. In 2010, that came down to three. And in 2015, the number plunged to two. Even Ram Vilas Paswan, known as an astute leader who understood which way the wind was blowing to effect a seamless switch, openly acknowledged that he could not become a political force in the state on the strength of just votes from the Paswan community. It was this that had dictated his support for the Mandal Commission report as well as other political somersaults in his career. This year’s Bihar election could prove to be the biggest risk the LJP leadership has taken in its existence—especially if voters, notwithstanding Chirag’s claims of loyalty to Narendra Modi, decide to vote directly for Modi’s candidates and his closest allies instead.

This seems to be the season of books on the history of

India’s economic reforms. Often, it’s about conflicting versions of that history—and equally conflicting versions of ownership of key proposals in the 1992 Union Budget. A book by Isher Judge Ahluwalia, former Chairperson of the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) who died recently, has rekindled interest in the subject as well as turned the spotlight on what went on backstage. Her husband, Montek Singh Ahluwalia, then Finance Secretary and the most important public policy official on economic reforms in the Manmohan Singh regime, also

released a book—Backstage: The Story behind India’s High Growth Years—recently on the period of key economic reforms. For many of the books on those years, Manmohan Singh, the crucial driver of the reforms, becomes a footnote or is pushed to the margins while the writer himself becomes the protagonist. Now, some of that self-trumpeting is not going uncontested, even the more articulate versions. Arvind Virmani, a close associate of Montek, has now

come out in the open with his version of what went on backstage in the key reform years. He maintains: “The 1992 Budget speech included the Dual Exchange Rate proposal

that I formulated and gave to the DEA Secretary Montek Ahluwalia in a 10-page note. The note was then sent to the RBI, which worked out the operational details. The final version was worked out in the home of RBI Governor Venkitaramanan, with me and

Joint Secretary YV Reddy representing the [Ministry of Finance].” Voila!

The Real RefoRmeR

ChiRag’s Way

2 november 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 13

Expenditure Secretary TV Somanathan may not have

been a well-known name earlier, but since end-2019—after the 1987 batch officer from the IAS’ Tamil Nadu cadre was appointed to his current post in the finance ministry—his star has been ascending. In March 2015, Somanathan was appointed Joint Secretary in the PMO. Before that, he was Commercial Taxes Commissioner and Principal Secretary in the Tamil Nadu government. When he was raised to expenditure secretary in December

last year, the post had been vacant after the appointment of GC Murmu as the first Lieutenant Governor of the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. On October 29th, Murmu relinquished the post of expenditure secretary and Atanu Chakraborty, a 1985 batch IAS officer, was given the additional charge. Somanathan

was awarded the gold medal for the best IAS trainee in his batch and has a PhD in economics from the University of Calcutta. A trained chartered accountant (CA), this bureaucrat’s inimitable talents—including those of a CA, CMA and chartered secretary—

apparently carry a lot of weight in policy formulations. The good news is that he has five years left in service and is tipped to scale greater heights.

‘India’s Turning Point: An Economic Agenda to Spur

Growth and Jobs’ was a report from the McKinsey Global Institute released in August this year. The widely read document bats heavily for a reform agenda in the next 12-18 months to accommodate 9 crore more workers in non-farm sectors by 2030, especially in the thick of policy decisions that lead to high growth in the manufacturing and construction sectors. In 2017, there was ‘India’s Labour Market: A New Emphasis on Gainful Employment’. McKinsey became the most favoured agency for many establishments. Its policy perspectives became the core ideology for many businesses to ‘rationalise’ their workforce over the years. Thus buoyed, the agency drafted its newsletter to advise on pruning and redeploying staff in major organisations in the capital. The man McKinsey tasked with the job is now wreaking havoc on the job market and being blamed for largescale retrenchments.

sCaling The heighTs

WReCking Ball

The Congress rebel in Rajasthan, Sachin Pilot, and Ghulam Nabi

Azad, Leader of the Opposition in Rajya Sabha, have both been added to the list of star campaigners for the Bihar Assembly elections along with party chief Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi and Priyanka Gandhi Vadra. Azad was among the 23 dissenters who wrote to Sonia Gandhi earlier, demanding a complete overhaul of the party’s organisational structure. Pilot revolted against Rajasthan Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot. The move to include these two in the campaign A-list of 30 is, therefore, seen more as a symbolic act of mollifying them. With the three heavyweights of the Congress’ first family featured high on the list, Azad

seems destined to linger near the margins. That the old timer, among others, had already been relegated to the sidelines was evident when the party tasks performed earlier by him were handed over to lightweights such as KC Venugopal. That shift was evident in the last Parliament session when men known to punch much above their political weight were assigned the task of handling the Congress’ parliamentary group in the Upper House. They were at the forefront of leading loud protests in the well of the House. And the leaders who orchestrated these unseemly theatrics now seem to be eyeing the opposition leader’s post that will become vacant when Azad retires early next year.

sTaR CampaigneRs

2 november 202014

W hat is a ‘Gita’? i have been writing about Gitas in the Mahabharata. But whether it is Gitas in the Mahabharata or in other texts, that question can’t be answered

satisfactorily. ‘Gita’ simply means something that was sung. it may certainly be the case that the Bhagavat Gita was the first such Gita. it is certainly the case that the Bhagavat Gita is the most important of these Gitas. Nevertheless, one should be aware that there are other such Gitas. there is a website that has sanskrit documents. it has a listing of such other Gitas and their texts. that lists 55 Gita texts. there are a couple more on the Gita supersite maintained by iit Kanpur. that means, the Gita corpus has around 60 texts. One might argue that, to be called a Gita, a text has to be explicitly described as a ‘Gita’. there is a problem with this argument. those descriptions will typically be in the chapter heading, or in the colophon added at the end of a chapter or text. But the vintage of these chapter headings and colophons is later. there is no means of knowing whether they were part of the original text.

Let me stick to the Mahabharata and let me stick to the Critical Edition of the Mahabharata, published by the Bhandarkar Oriental Research institute (BORi) in Pune. From 1916 to 1966, the BORi sifted through more than 1,200 versions of the sanskrit Mahabharata and produced what is inferred to be the closest to the original text. this text is known as BORi’s Critical Edition. Nothing can be established with certainty and hence there is subjectivity in inferring. some critiques have criticised BORi, both on grounds of omission and commission, though more the former. today, the Mahabharata text is divided into 18 parvas. they are not even in size and their names are 1) ‘adi Parva’ 2) ‘sabha Parva’ 3) ‘aranyaka (Vana) Parva’ 4) ‘Virata Parva’ 5) ‘Udyoga Parva’ 6) ‘Bhishma Parva’ 7) ‘Drona Parva’ 8) ‘Karna Parva’ 9) ‘shalya Parva’ 10) ‘souptika Parva’ 11) ‘stri Parva’ 12) ‘shanti Parva’ 13) ‘anushasana Parva’ 14) ‘ashvamedhika Parva’ 15) ‘ashramavasika Parva’ 16) ‘Mousala Parva’ 17) ‘Mahaprasthanika Parva’ and 18) ‘svargarohana Parva’. Most people are familiar with these names. the Mahabharata was composed over a period of time. there was an earlier

segment. Let’s call it Mahabharata (O); ‘O’ standing for ‘original’. there was a final text. Let’s call it Mahabharata (F), ‘F’ standing for ‘final’. these things are difficult to date with any precision. therefore, Mahabharata (O) probably dates to 500 BCE, while Mahabharata (F) probably dates to 500 CE. this is a range of 1,000 years. Most scholars will agree on this range. at best, some will say 400 BCE for Mahabharata (O) and 400 CE for Mahabharata (F).

there have been attempts to identify later layers and distinguish them from older layers, such as through examining the evolution of the sanskrit language. But all such attempts are inherently subjective. a quote from 10.35 of Bhagavat Gita is relevant. in this section, Krishna is telling arjuna how he is the most important among various categories. For example, among all shining bodies, he is the sun. among all the gods, he is indra. among all the mountains, he is Meru. among all animals, he is the lion. among all rivers, he is Ganga, and so on. that bit of 10.35 states: ‘among months, i am Margashirsha.’ Margashirsha is also known as agrahayana, roughly from around November 21st to December 20th. Calendars differ across the country, but most people will agree the calendar begins with the month of Chaitra, roughly from March 21st to april 20th. Why would Krishna imply that Margashirsha was the most important among all the months? that can only be because the calendar then started with the month of Margashirsha. One should note that the word ‘agrahayana’ literally means the first month of the year. therefore, when this bit of the Bhagavat Gita was composed, Margashirsha (named after the nakshatra Mrigashira) was the first month of the year and the year started with the full moon in the month of Margashirsha. Many important festivals are still concentrated in Margashirsha. there are reasons why it is difficult to use astronomical data to date events, such as the date of the Kurukshetra War. astronomical calculations moved from nakshatras to rashis (signs of the zodiac), from lunar months to solar months. Lunar months sometimes started with purnima (the day of the full moon), sometimes with amavasya (the day of the new moon). therefore, one has to make assumptions, which in the last resort, are subjective.

Reimagining the GitaThe limits of reading it as an independent text

By Bibek Debroy

indian accents

2 november 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 15

subject to this, a respected astronomer named VB Ketkar (Indian and Foreign Chronology, 1921) gives us an answer to the question of when Margashirsha was the first month of the year. his answer gives us a range between 699 BCE and 452 BCE. this part of the Bhagavat Gita is therefore as old as Mahabharata (O).

sanskrit grammar evolved over a period and, after Panini, came to assume a certain structure, especially in what is called classical sanskrit. We haven’t been able to date Panini satisfactorily. sixth century BCE, fifth century BCE or fourth century BCE are reasonable guesses. Linguistic evidence from parts of the Bhagavat Gita show that these sections were written before classical sanskrit became the norm. therefore, fifth century BCE, fourth century BCE, third century BCE—something like that. these parts of the Bhagavat Gita, therefore, pre-date Mahabharata (F) and belong to more or less the same period as Mahabharata (O). Couldn’t there have been a Bhagavat Gita (O) and a Bhagavat Gita (F), with these earlier sections belonging to Bhagavat Gita (O)? Couldn’t there have been multiple authors of the Bhagavat Gita? this is an old issue, discussed threadbare, but never seems to go away. the dead horse keeps kicking every once in a while. in these columns, i have mentioned Yardi’s work, who tested for multiple authorship of both the Bhagavat Gita and the Mahabharata. so as not to maintain the suspense, there was a single author for the Bhagavat Gita and five authors for the Mahabharata. Naturally, this is probabilistic, not deterministic. Nothing can be confidently asserted with certainty. But that’s the way science works. there was a Mahabharata (O) and a Mahabharata (F). But there is no Bhagavat Gita (O) or Bhagavat Gita (F). the Bhagavat Gita is an integrated whole. MR Yardi did his analysis when artificial intelligence (ai) couldn’t be used for such work. ai has now been used to vivisect William shakespeare’s works, such as Henry VIII. Who knows, in the future, ai may also be used to refine the Yardi kind of work.

therefore, a single author composed the Bhagavat Gita around fifth century BCE. Couldn’t the Bhagavat Gita have been authored as an independent text that was spliced into Mahabharata (F) later? i suspect many people who read

the Bhagavat Gita don’t read the Bhagavat Gita sub-parva. Most people are familiar with the 18-parva classification of the Mahabharata, listed earlier. What may not be known is that there is also a parallel 100-parva classification of the Mahabharata, which probably pre-dated the 18-parva classification. Remnants of that remain in the sub-parvas that are part of the 18 main parvas. For example, the Bhagavat Gita occurs in ‘Bhishma Parva’, when Bhishma was the commander of the Kaurva army. Within ‘Bhishma Parva’, there is a Bhagavat Gita sub-parva. this has 994 slokas and 27 chapters. those who know about the Bhagavat Gita will be surprised. isn’t the Bhagavat Gita supposed to

have 700 slokas and 18 chapters? indeed, the Bhagavat Gita does have 700 slokas and 18 chapters, but the sub-parva named after the Bhagavat Gita has a little bit more than what we know as the Bhagavat Gita text. in the 100-parva classification of the BORi edition, this Bhagavat Gita sub-parva is numbered 63. the first nine chapters are about preparations and preliminaries. the 10th chapter then starts with the famous words: ‘Dhritarashtra asked, ‘O sanjaya! having gathered on the holy plains of Kurukshetra, wanting to fight, what did my sons and the sons of Pandu do?’ the first nine chapters lead to the 10th chapter, which is the first chapter of the Bhagavat Gita. there is no break in continuity between the ninth and 10th chapters. the Bhagavat Gita is part of Mahabharata (F). Lest we forget, slokas from the Bhagavat Gita are also found elsewhere in the Mahabharata,

sometimes with minor variations. those who seriously suggest that the Bhagavat Gita is an independent text, interpolated into the Mahabharata later, have probably not read the Mahabharata.

if they do, they will discover these other Gitas in the Mahabharata. We come back of course to the definition of ‘Gita’. if Gita is defined as a text where Krishna himself speaks to arjuna, other than the Bhagavat Gita, one will only have anu Gita. But if Gita is defined as any text that talks about the four human objectives (purusharthas) of dharma, artha, kama and moksha, there are several other texts. Of course, the entire Mahabharata is also about these objectives. n

If GIta Is defIned as a text where KrIshna hImself speaKs

to arjuna, other than the BhaGavat GIta, one wIll only

have anu GIta. But If It Is defIned as any text that talKs aBout the four human oBjectIves (purusharthas) of dharma,

artha, Kama and moKsha, there are several other texts

2 november 202016

The voice of emperor hirohito of Japan was famously heard for the first time when he declared on the radio his country’s surrender in World War ii. essayist Richard Lloyd Parry writes that so

unprecedented was the whole event for the Japanese that many listeners had difficulties understanding the emperor on account of his highly stylised speech. Throughout his long reign, from 1926 to 1989, the emperor had given only one interview in 1975 to an American journalist. his son, emperor Akihito (who abdicated the throne in 2019 to make way for emperor Naruhito, thus bringing to a close the heisei era of the chrysanthemum Throne), did slightly better. he gave occasional but highly scripted press conferences where questions had to be submitted and vetted by the imperial household Agency. on a rare occasion however, this persona of royal discreteness slipped—the word ‘persona’ comes from the Latin word ‘prosopon’, a ‘mask’ used during a performance in order to become another—and Akihito broke away from the script and, uncharacteristically and movingly, spoke out against the pressures that had been put on his wife empress Michiko by social expectations and the vicious gossip sheets. for a brief moment, Akihito the man set aside Akihito the emperor and revealed his inner thoughts, only to recede back into the elaborate persona that had been patiently created over decades through acts of personal sincerity and the halo bestowed by royalty.

on the other end of this menagerie of political inner voices is Donald Trump who—like most politicians who steer their ship within the maelstrom of democratic waters—misses no opportunity to appear in front of cameras and speak ex tempore. Despite his usual grabbag of conspiratorial gossip, innuendo, paranoia, faux nostalgias and racist dogwhistles, unlike other great megalomaniacs in history there is no confusion about who is doing the talking. his speech is littered with first person singular. his administration’s achievements and victories are solely his (and their failures are solely because of others). it is often as if he were inviting us to see the squalid inner quarters of his steadily declining mind which once had the self-confidence of a veteran braggart to declare, “i have the best words.”

But for much of history, the inner worlds and soliloquies

of political leaders, knaves and villains—including in litera-ture—have often posed greater challenges to any efforts to discern who exactly is doing the talking. is it the head of state, the potentate who dictates terms, the man behind the facade or the human cloistered behind the accoutrement of power? for centuries, ever since that great Shakespearean villain Richard iii declared on stage ’Now is the winter of our discontent/ Made glorious summer by this son of York/ And all the clouds that lour’d upon our house/ in the deep bosom of the ocean buried’, authors and scholars have wondered who exactly the ‘our’ is in those lines. They ask this because a few lines later, Richard iii re-sorts to a more familiar first person pronoun: ‘But i, that am no shap’d for sportive tricks… i, that am rudely stamp’d, and want love’s majesty… i, that am curtail’d of this fair proportion…’. This ‘pronoun shifting’ in speech has often been a way for the exteriority of a person, especially in a performative context, to recede and allow for a more reflective inner voice to emerge and allow insecurities and anxieties to burble forth.

in the case of Trump, however, this first person singular is often merely not just an opportunity to catalogue and enumer-ate his self-declared greatness but also an opportunity to use the bully pulpit of the president’s office to speak as if there were no inner restraint. No prejudice was too shameful to utter in public and no paranoia unworthy of treating as fact. it is therefore unsur-prising that many have resorted to thinking of Trump’s manner of speaking that is indistinguishable from a steady lurch towards chaos and cruelty as the id of American body politic.

in the freudian vocabulary, the id is born from unconscious and the ego from the conscious. These mental constructs are drawn as being in directly in opposition—as if the mind’s role was often to participate in an election to choose between the two. The critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis tells us, ‘The id is primitive, the ego civilized; the id is unorganized, the ego organized; the id observes the pleasure principle, the ego the reality principle; the id is emotional, the ego rational.’ All of this naturally lends to useful, but arguably facile, juxtapositions when talking about Trump and Biden. This contrast between the two is played up by a third and singular presence in the American (and democratic) electoral politics: the mainstream media and its handmaiden, social media. To wit, they act like

An American Folk TaleAn alternative portrait of Donald Trump

By Keerthik Sasidharan

touchstone

2 november 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 17

the superego—that hectoring, bullying, self-critical part of the ego that borrows freely from the unconscious, and therefore the id. The superego, writes British psychoanalyst Adam Phil-lips, acts a permanent faultfinder. it echoes a line from Samuel Beckett’s novella called Worstward Ho: ‘Something there badly not wrong.’ The superego is like a self-aggrandising Tv anchor or a hectoring father, whose usual rhetorical style is to accuse, to insinuate weakness, to bore you with their righteousness and ultimately pummel you daily with cruel assessments. if we resort to this tripartite division of the American or, more gener-ally, the Western, political mind, the age of Trump has been one where the id and the superego have come together to browbeat the rational ideas of the American self, its ego, into trembling submission. it is perhaps therefore not surprising that Trump’s rallies continue to attract hundreds of thousands of attendees, who pooh-pooh away any risk from the coronavirus and who travel from far and wide to hear him rail against all his, and

implicitly their, complaints about the world: ‘hillary clinton’, ‘china virus’, ‘immigrants’, ‘Mexicans’ and so on.

The fact that despite his catastrophic handling of the covid-19 pandemic, he continues to poll within the margin of statistical error in many states against Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden should give all a pause. Trump may very well lose by a landslide on November 3rd but Trumpism has sown its seeds in American political grounds. Much like the Reagan-Thatcher era birthed a generation-long belief in neo-liberal institutions and market fundamentalisms, the Trump era has birthed a set of vocabularies that has mainstreamed old, primordial urges of the American body politic: isolationism, xenophobia, white nationalism—all in the name of the collec-tive good. emotions and prejudices which had somehow been tempered by custom, rules and inner restraints of common people have now found ways to appear reasonable and ineluc-table thanks to Trump’s singular presence.

in this sense, Trump has been that little understood phenom-ena in present-day political vocabularies, but one that is all-too-familiar in folk tales—a Great Seducer who, through his own autobiographical soliloquies, has tapped the listener’s subcon-scious complaint that the world is unjust. Seduction, of course, is a dirty word especially in our times when men and women speak about ‘agency’ as if it were a sacramental truth of our inner psychologies. But seducers have appeared throughout history, in guises that are often hidden in plain sight. in folk tales, which are often morality plays—such as ‘Little Red cap’ (made famous in the 17th century version by charles Perrault called ‘Le Petit Chaperon Rouge’ or ‘The Little Red Riding hood’)—they are ex-plicitly visible. The wolf in that folk tale, as psychologist Bruno Bettelheim has written, is a ‘dangerous seducer’, who ‘represents all the social, animalistic tendencies within ourselves’.

Modernity has spawned many seducers, especially when old order crumbles and fosters cognitive crises—be it when the gods and magic surrendered to scientific explanation (Max Weber called this ‘the disenchantment of the world’), when rituals that marked the relationship between the sacred and the profane eroded (Marcel Mauss called it ‘desacralisation’) or when an individual was set afloat in a sea of meaninglessness thanks to breakdown of social relations (emile Durkheim called this ‘anomie’). Trump, and his soliloquies which are all bile and much fury, appeared at a similar juncture: when economic order has over the past two decades changed all-too-dramatically for many. This is, in parts, the real reason to be pessimistic irrespective of the electoral results. The underlying faultlines of the American polity are only likely to widen as economic insecurity marries with demographic changes to birth strange new anxieties with no names. in a decade from now, we may come to think of Trump as a symptom of malaise and divisions that was intermittently successful in overpowering the rational part of the American po-litical mind. only by then however—faced with a powerful and belligerent china—there will be more calls for an efficient and radical version of all that Trumpism, in its malevolent genius, has set in motion. Winter, after a brief spell of spring, is coming. n

modernity has spawned many seducers, especially when old order crumbles and fosters cognitive crises—be it when the gods and magic surrendered to scientific explanation, when rituals that marked the relationship between the sacred and the profane eroded or when an individual was set afloat in a sea of meaninglessness thanks to breakdown of social relations

I l lustration by Saurabh Singh

2 november 202018

Your freedom ends where my nose begins. As long as what you say or write does not incite violence or cause public disorder, freedom of speech is absolute.

The supreme Court is wrestling with a slew of issues around the limits of free speech. If hate speech causes communal or caste enmity, it breaks the law. There are established provisions in the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) to deal with such breaches of law. There should be no ideological bias in judging these issues, just the sensible application of law.

The controversy over a pro-right bias in social media is facetious. If anything, facebook and Twitter, for example, suffer from a pro-left bias. Hate posts from left extremists are tolerated. Hate poets from right extremists are banned. Both obviously should be banned. But the bias is clear.

Part of the problem is that the left ecosystem is more united and strategic than the right ecosystem. It moves fast, orchestrates a social media storm and ruthlessly discredits key members of the right. The right ecosystem is more divided and less tactical.

The extreme left disguises its fascism and intolerance to other points of view with finesse. The extreme right lets its fascism hang out to dry.

History favours the left: young people are naturally left-leaning and anti-establishment. The right’s demography is older, wealthier and (in America) whiter. In a battle of perception between hoodies and suits, there can be only one winner.

The extreme left covers its tracks well. some of the worst human rights crimes have been perpetrated by left-communist despots from mao Zedong and stalin to Castro and Pol Pot.

The right ecosystem is inarticulate and ponderous. It is shrill and apologetic at the same time, burdened by grievance and constantly seeking approval and validation from the left which treats it with disdain.

Left-leaning TV news channels delight in hectoring members of the right ecosystem who are uncomfortable with english and mumble their way through panel discussions. Left panelists in contrast lie with a straight face and often win the argument.

The left-leaning media in the West forms a cartel of opinion. The modus operandi is well-rehearsed: reuters flashes a piece of inaccurate news, the BBC follows it up, The Guardian adds context, The New York Times picks up the threads, Cnn closes the circle.

The principle of exclusion is an important weapon in the armoury of the left. In media, it ostracises right voices. The left cabal monopolises op-eds in dailies and TV panels. Left-aligned media like NDTV 24X7, The Wire, Scroll, The Caravan, The Telegraph and The Hindu keep up a barrage of negativity.

Good journalism is always adversarial to the government and, to use a tired cliché, must speak truth to power. But it often speaks lies to power. That subverts everything that good journalism stands for.

Criticism is the lifeblood of media. some of the criticism is ideological. so be it. some is made up. Again, so be it. Good journalism delivers news and opinion based on facts. The

plurality of opinion in a democracy evens out the narrative.

If facts are twisted, the market will punish the newspaper, website or channel. A quick glance at television broadcast ratings (BArC) and the Indian readership survey (Irs) show how the market is punishing those who pursue an agenda-driven narrative.

There are fascists on both the left and the right. But those on the left use bullying as standard operating procedure (soP). The real target of every attack by the leftwing-Congress

ecosystem is of course Prime minister narendra modi. read between the lines—or the lines themselves—

and it boils down to an attack on Hindutva, creeping majoritarianism and the erosion of institutional governance. some of these criticisms are justified. The modi Government has failed to tame the bureaucracy, cut over-regulation and take old corruption cases to their conclusion.

modi’s Government must be held to account over its handling of Covid-19, the economy, China and a host of other issues. The criticism should be fierce and fearless. In India, and in the West as well, that is simply not the case.

Left-leaning media deals in fake news to tarnish the government rather than criticise it constructively and offer solutions. right-leaning media on the other hand behaves like the propaganda machinery of the government and loses credibility. It is appalling to see powerful sections of the electronic and print media allowing themselves to be used as arms of the government, abandoning all

critical faculties. Balance—the cornerstone of journalism—is

the victim. n

Left, Right and NowhereWho’s more fascist than the other?

By Minhaz Merchant

saurabh singh

opinion

Minhaz Merchant is an author, editor and publisher

A new generation of leaders has become very relevant to the

Bihar election. The Rashtriya Janata Dal’s Tejashwi Yadav has arrived as the main opposition leader. Lok Jan-shakti Party’s Chirag Paswan is the joker in the pack who might have a crucial role to play after the election. For the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), however, the main draw remains its perennial trump card—Narendra Modi. In an attempt to create a wave in favour of the Janata Dal (United)-BJP alliance, Modi is all set to address as many as 12 rallies, three in a day. Also, for the first time, he will seek votes for Nitish Kumar, a man who had opposed his elevation as the BJP’s prime ministerial face in 2013 and ended his alliance over it then.

Whisperer Jayanta Ghosal

Old FavOurite

HOme BOund

In what was highly unusual, Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan complained in a letter to Congress President Sonia Gandhi about her party’s senior leader

Kamal Nath. The latter had in an election rally used derogatory language against a female BJP by-election candidate. Rahul Gandhi, too, had criticised the language but Kamal Nath did not apologise. Instead, he shocked his party by saying that it was Rahul’s personal opinion. A minor issue has now blown up into a major one in the Congress.

The Unusual Complaint

20 2 november 2020

Former Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis may have become the BJP’s in-charge of Bihar for the

election, but it is said he remains busier in his home state. In earlier elections, when Arun Jaitley or any other senior BJP leader was at the helm in a state, they used to stay there for a few months at a stretch, even taking a flat or house on rent. But that is difficult in the times of Covid. So, Fadnavis comes on and off to Patna.

21 september 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 21

I l lustrations by Saurabh Singh

Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, in Mumbai, is extraordinarily wealthy and powerful. Elections to it are,

therefore, very important. For 25 years, the Shiv Sena has been in power there, but last time it fought alone without the BJP in alliance and retained power only by a slender margin. The next elections are only due in 2022 but with the estrangement between the two parties, moves are already afoot on how it will be fought. The big question is what will the Sena do. There are rumours that it might ally with the BJP and that is why its senior leader Sanjay Raut met Devendra Fadnavis recently. But it is also being said that the Sena could fight alone, and if necessary, have a tie-up with the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) and the Congress after the election. The NCP, however, is keen on a pre-poll alliance. Many secret discussions are reportedly already underway.

Because of Covid and its economic impact, several Government projects have stalled. But in this go-slow

situation, the Prime Minister’s dream project of a new Parliament building and a makeover of the area has continued. Old Government buildings will be demolished and the old Parliament will be a museum of the Indian freedom movement. From Rashtrapati Bhavan to India Gate, several buildings will come up. Opposition parties are protesting about the resources being spent but Team Modi maintains this needs to be done.

Kumar Vishwas, who used to be an impor-

tant leader in the Aam Aadmi Party, might have fallen out of favour with its leader Arvind Kejriwal, but both the Congress and the BJP seem to have a soft spot for him. He was a candidate against Rahul Gandhi in Amethi in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, but in Rajasthan, Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot has made Vishwas’ wife Manju a member of Rajasthan Public Service Commission. A Rajasthani, she is a professor from the Mali com-munity to which Gehlot too belongs. Meanwhile, Vishwas’ brother Sanjeev Sharma, a professor at Meerut’s university, was made the vice chancellor of Mahatma Gandhi Central University in Bihar. Some say it was at the behest of the BJP.

advance Plotting

house on Track

Man For all ParTieS

Maharashtra Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari seems to be in some trouble after dashing off a letter attacking

Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray over the reopening of temples, something that the state BJP is keen on. But Union Home Minister Amit Shah, in a media interview, did not support the Governor. Now the Shiv Sena wants the Governor changed. NCP chief Sharad Pawar too hit out at him asking how anyone with self-respect could continue in office. There could be a reshuffle of governors after the Bihar elections and Koshyari must be wondering about his fate. The Centre not supporting Koshyari led to much interest in West Bengal where Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has also written a letter to the Prime Minister complaining about the Governor there, Jagdeep Dhankhar. She asked why, if there is so much reaction to Koshyari’s utterances, no action has been taken against Dhankhar who has been speaking against her for a long time.

In Karnataka, senior Congress leader MB Patil, who is a figurehead of the

powerful Lingayat community, could be switching to the BJP. Although Patil tweeted that the rumours are baseless, he did not rule out the possibility. The BJP central leadership may also be searching for a Lingayat leader as a counter to their state leader and Karnataka Chief Minister BS Yediyurappa who, too, retains enormous pull in the community.

backfired attack

Lingayat Alternative

2 november 202022

he ceasefire announced by the Prc in the sino-indian war came into effect on 20 november 1962. it meant different things to different people, particularly those involved as prominent personalities in the autumn war.

in the opulent and sybaritic luxury of room 118 in the Great hall of the People in the Zhongnanhai district of Peking, chairman Mao Tse Tung stared at the collection of late autumn leaves on the lawn outside his window. he needed to be distracted from the matters of state. The distraction was in the form of a coy teenage girl.

in a riveting book, Mao’s physician, dr Li Zhisui, has revealed that Mao had an insatiable appetite for sex and was quite happy to manifest his sexual desire with either gender. But in november 1962, during the sino-indian war, Mao was besotted by a young 14-year-old girl called chen. she was his favourite partner from the diverse supply of young people available in his harem. Mao was obsessed with longevity and, according to dr Li, he used to follow the ancient daoist prescription for ageing men to supplement their declining yang or male energy with yin shui or the water of

yin. Yin shui was the vaginal secretion of young women. Because yang is considered essential to health and power, it cannot be dissipat-ed. Thus, when engaged in coitus, the male rarely ejaculates. frequent coition is, therefore, necessary to increase the amount of yin shui.

however, in pursuit of many women, Mao contracted trichomonas vaginalis, but because he was asymptomatic, he refused to be treated for it. instead, he became a chronic source of transmission of the disease. interestingly, trichomonas vaginalis also leads to psychiatric disorders. What is fascinating is that Mao, who professed to be an atheist and a communist, was actually a follower of the ancient chinese religion of daoism. This religious philosophy co-existed along with confucianism in ancient china, particu-larly during the eastern Zhou period which gave rise to the chinese dream of world domination. Was Mao’s ruthless cruelty along with his delusions of grandeur a consequence of this disease? dr Li Zhisui obliquely alludes to it. it is unfortunate that in those days, the Government of india had an inadequate system of intelligence from within china and that it was, therefore, unable to decipher the reasons for Mao’s almost visceral hatred of india.

For nehru, The news of the dire threat to the plains of assam, brought to him on 19 november by General Thapar, was devastating. according to shiv Kunal Verma, the author of The War that Wasn’t, on the morning of 20 november 1962, all of

india was still in the dark about the ceasefire because the indian chargé d’affaires in Peking had not relayed the news to new delhi. nehru had summoned Lt. Gen. Thorat, now retired, by special aircraft to new delhi, ostensibly to offer him the job of coas in the wake of General Thapar’s resignation. When Thorat met him in the morning, a sleep-deprived nehru was cutting a cigarette into tiny pieces with a pair of scissors. since the conversation between nehru and Thorat veered round to Krishna Menon and degener-ated into acrimony, nehru was distracted and Thorat left without receiving a job offer.

nehru wanted Kaul to succeed General Thapar; however, President radhakrishnan dissuaded nehru from taking that step. The next

When the CIA came to India’s rescue in 1962

Mao against nehru

T

open essay

By iqBal Chand Malhotra

2 november 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 23

in line to be offered the job was Lt. Gen. daulet singh, who passed on the offer. after Menon’s resignation was accepted by nehru on 1 november 1962 in the midst of the war, nehru personally took charge of the Ministry of defence. Menon, with due credit to him, recommended Thorat for the top job, even though he had earlier sabotaged Thorat’s natural succession. now, with Thorat getting nehru’s goat, the job by default went to Lt. Gen. J.c. chaudhuri.

For Mao, Who had successfully drained the indian establishment of their ‘collective mojo’, the task of keeping

Lop nor out of public gaze remained, notwithstanding the ‘victory’ over india.

in the early 1950s, soviet aerial surveys of the shaksgam Val-ley revealed that the shaksgam river originated in an area be-tween the shaksgam Glacier and the shaksgam Pass. This river merges with the raskam river at a point called chog Jangal and, thereafter, the combined river is known as the Yarkand river. The Yarkand river merges with the Tarim river. The shaksgam river lies on the northern side of the Karakorum watershed as does the Karakash river that flows north from aksai chin

and merges into the Tarim river. Both the shaksgam river and the Karakash river originate within the political boundary of Maharaja hari singh’s state of Jammu and Kashmir that merged with india on 26 october 1947. Because of his unwillingness to let the indian army recover the entire lost territory of this state from the clutches of the Pakistan army whose proxies invaded the state on 22 october 1947, nehru was responsible for india losing territorial control over the shaksgam river in 1947. further, because of nehru’s unwillingness to prevent the sino-soviet invasion of aksai chin in March 1950, india lost territorial control over the Karakash river to china.

Both the shaksgam river and the Karakash river flow into the western part of the Tarim river. The eastern part of the Tarim river that flowed into Lake Lop nor was scheduled to become radioactive; so was Lake Lop nor. The latter was going to be the drainage point of all the radioactive debris from china’s proposed nuclear tests. it, therefore, became crucial for china to usurp and claim ownership over both the shaksgam river and the Karakash river in order to provide for the future irrigation needs of the entire Tarim Basin post the nuclear tests that were planned. in effect, china had to steal both these rivers

At the White House on 19 November, Kennedy convened a high-powered meeting that discussed increased US military assistance to India and options for a show of force in the region. Also mentioned was the possibility of using the CIA’s Tibetan guerrillas. The new CIA Director John McCone, who replaced Allen Dulles after the Bay of Pigs, was on hand to brief Kennedy on such covert matters. With McCone was Des FitzGerald, the CIA’s Far East Chief

John F Kennedy and Jawaharlal Nehru at the White House, November 1961

ap

2 november 202024