Congress and the Decline of Public Trust. Joseph Cooper (Book Review)

Transcript of Congress and the Decline of Public Trust. Joseph Cooper (Book Review)

Christy KaupertCooper Book Review

While Joseph Cooper’s Congress and the Decline of Public Trust

contains genuinely well-written analysis and should be read by

students of Congress; that is not to say that even upon a second

reading this reviewer’s perception of Cooper’s contribution had

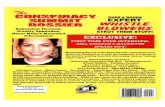

significantly changed. The book itself gives the appearance of

ominous contents that would portend, largely, a pessimistic view

of the mechanism and its members. The editors chose well the

graphic on the front cover which not only depicts “the hill” as

fragmented by the alternating colors of black and white but a

symbolic “stepping down” series of bars. The forward, by Bill

Bradley, provides a perception of an increasingly hostile climate

and the impediments faced by members, which is amplified by an

increased and inexorable suspicion of this body by the voting

electorate. The forward was well written and a nice addition to

an otherwise, discouraging book.

Having first read this book prior to 9/11; this reader was

curious if any of her initial perceptions have changed about this

work and largely, the answer is no. Obviously, as is typical in

times of crisis, the electorate seeks and demands strength from

their leaders and the election of 2002 would seem to validate the

impression that Republicans still maintain the reputation as the

party to cling to in times of crisis; particularly where America

is perceived as threatened from outside forces. Part and parcel

to a larger trend that was discussed in The Rise of the Southern

Republicans, the outcome then would seem predictable and public

trust in the body of Article I would at least temporarily (and

perhaps only superficially) rise.

Cooper begins to explore what he describes as “the puzzle of

democracy,” by illustrating (Figures 1.1 and 1.2) which reflect

polling results two distinct issues: public trust in government

in a broad sense, and public trust with respect to two specific

institutions in government. However; the question this reader

initially offered still lingers even after this second reading:

Did the public make the distinction in these two questions given

the similarities of the resulting data and the paradox of ‘hating

Congress but loving our Congressional representative? Comparing

these two figures, the Reagan years stand out, indicating a rise

in public trust in both government and the institutions of both

Congress and the President.

While one could argue that this phenomenon might be merely a

facet of Reagan’s “cult of personality,” this reader had pause to

reflect on the “hype” of the cold war and the rallying effect

2

this may have had on the public. Of course, given controversy

surrounding the election of 2000 and the subsequent crisis of

9/11, this reader is forced to draw connections between the hype

and the reality of crisis under both the Reagan and current Bush

administrations on a myriad of issues. The resulting connections

drawn by this reader alone would seem to explain away much of

increased ‘trust’ in polling numbers indicated; but it is

important to note that for this reason alone perhaps measuring

trust in government must, or at least should, exorcise the answer

‘trust in government” to do what? However; the in the end

analysis, and as correctly pointed out by Cooper, the issue of

trust and what factors impact it is not a new one; hence this

collection of essays from an array of scholars who have studied

this. Therefore, how we study public trust has changed and

Cooper argues there are ‘degrees” or “trust levels,” which,

although they are related, are distinct from each other. Public

trust, measured at the governmental level, the system level, and

at the policy level, produces data which, when assembled

collectively, create the “puzzle of public trust.”

These ‘degrees of trust” or “contours” as Cooper identifies

them, cannot be understood alone and must be examined as a part

of a larger, more general problem. The fundamental crux of why

3

government is not trusted appears to have shifted from the

public’s broad concern about legitimacy and the structural design

of the federal government to the more specific concern about

legislative behavior and motivation. Here Cooper cites much of

the literature with which students of Congress would be familiar

to support his position; but here this reader is forced to offer

criticism insofar as ‘design.’ The reader will not find

substantial explanation of the trends and the tables that depict

them until the appendix, and unfortunately Cooper fails to

reference these in the forward. Had these tables been discussed

within the context of the forward they would have been far more

useful rather than being simply anti-climatic.

In terms of the institutions themselves, Cooper notes a

higher level of public trust in the office of President than for

Congress and indicates this is due likely because the public has

adopted a higher degree of accountability therefore, the

possibility of higher levels of frustration emerge as a result.

Nevertheless, this reader speculates that it may be more a

product of superficial levels of understanding the public has of

the two institutions and here, another criticism emerges: Cooper

makes no mention of this possibility impacting trust. Cooper

attempts to support his argument here by using the 1998

4

Clinton/Lewinsky scandal as having very little impact on the

level of trust indicated in approval polls of either the

President or Congress, but mentions, albeit briefly, the ultimate

decline and subsequent rise in Congressional approval without so

much as an explanation as to when or why. Again, the flaw of

design is apparent because one is not given explanation for this

until the epilogue, wherein ponderous detail, Cooper discusses

the impact this scandal had on the levels of trust in both

institutions.

While acknowledging the dissonance of the contributing

authors’ speculations for the causes and potential solutions for

the decline of public trust, Cooper gives no support to one or

another, indicating that no one scholar may ever cogently

assemble the multi-dimensional ‘puzzle.’ Cooper contentedly

states that the distrust appears simply as an amalgam of

misunderstandings, primarily with respect to the concept of

democracy as opposed to the operation of our institutions

themselves. He concludes that in spite of the differing opinions

offered by the contributors, their respective works are best

viewed in terms of their similarities, and, largely, that all

their work, to some degree, considers the micro-level of

psychology and the impact of agents of socialization

5

(particularly the media and education) which are necessary

considerations when approaching the study of political attitudes

and behavior in and among the electorate.

For example, the second article by Shribman concentrates on

the external causes and outside factors that reinforce the

decline of public trust. He argues that the public’s perception

that special interests have an inordinate amount of influence on

policy outcomes is pervasive. This ubiquitous belief has a

profound effect on internal levels of efficacy; but assures us

that this belief is not exclusive to opinions about governmental

institutions. Table 2.1 illustrates that all institutions

experienced a decline in public trust; certainly, Congress was

not the hardest hit among them. Over the last thirty-six years,

medicine and business were the most affected, indicating a forty-

four point and thirty-seven point decline, respectively; however

Congress and educational institutions are the most recent

recipients of this decline. In fact, the latest Harris Polls

indicate the military is remarkably the most trusted institution

in America.1

1Harris Poll. The Harris Poll® #4, January 22, 2003. Leaders of the military continue to enjoy a far higher level of

confidence than those of any other institutions. Fully 62% of the public say they have a great deal of confidence in them;

this is down from 71% last year but far ahead of the other institutions at the top of the list – the White House (40%), the

U.S. Supreme Court (34%) and major educational institutions (31%)

6

Insofar as the factors that have contributed to the decline

of public trust, the 1996 Post-Modernity Project compiled by the

University of Virginia, appears to indicate the media is largely

responsible but this is the most recent polling data available to

this reader. Ultimately, the crucial factor is not so much the

amount of coverage the media gives to Congress, which according

to Schribman, has certainly declined, but more, the content of the

coverage. Schribman explains that from the period spanning 1972-

1978, articles about Congress had declined from a monthly average

of 124 to forty-two; but by the period spanning from 1986-1992

not only was the decline still present but stories of failure,

scandal and ‘gridlock’ become the sujet de jour; rarely, if ever, were

stories of successes discussed. Schribman proclaims this latter

trend as ultimately exacerbating what he calls the ‘twin

dangers:’ ignorance and growing alienation with which this reader

absolutely concurs. It is the opinion of this reader that

coupling Schribman’s argument with Hibbing and Morris’ theory

would connect the majority of the pieces which make up the

‘puzzle’ described by Cooper in his forward.

Schribman differentiates between the media’s coverage of the

President and Congress in relation to their respective roles in

the policymaking process. The media’s portrayal of Congress’s as

7

a story of “a work in progress” and the President as “a work

completed” may go far in explaining the level of distrust among

the electorate in these institutions. What is significant

however is the similarity between Cooper’s introductory remarks

and Shribman’s article with respect to the general lack of

appreciation for the democratic process they perceive the public

as possessing. Of course, Hibbing’s article expands further on

this perception.

“Appreciating Congress” is still, by far, the best-written

article included in this collection of essays. The writing style

was comparatively, the most fluid but that point aside, it was

also the most optimistic, which this reader found appealing.

Hibbing echoed that trust, viewed in its proper historical

context, is not new; nor are its disturbingly low levels

sufficient to categorize Congress as an exceptionally noxious

institution in the mind of the public. Throughout history, there

have been a myriad of institutions that have experienced waxes

and wanes in public trust and that largely; the public has grown

increasingly suspicious of all major institutions. Interestingly,

Hibbing’s research tended to contradict the model, which has

historically been used to define the efficacious citizen. It

appears that the demographic characteristics that we have used to

8

define an attentive and participating member in the electorate

(i.e. higher educations, higher income, etc.) now indicate a

citizen who is less likely to exhibit trust in government; at least

at the governmental level. Whether this translates to lower

levels of internal efficacy is unexplained to date; but certainly

lower levels of external efficacy are partly attributable to the

decline of voter participation.2

The strength of Hibbing’s article lay in the inclusion of

interview comments made by test subjects and provides interesting

material to consider more thoroughly; however, as very little

information was disclosed with respect to the subjects’

individual characteristics, one cannot ruminate long on the

hypothesis of a changed model of an efficacious citizen.

Ironically, the conclusion to draw from Hibbing is that the

blame, if you will, for the mistrust and outright ignorance

citizens exhibit for the democratic process is to be placed

squarely at the feet of educators. Hepburn and Bullock’s article

expand upon this supposition in the sixth article by directing

2 This reader would note the caveat that the Motor Voter Act had an equally depressing impact on vote turnout merely by virtue of increasingthe universe of voters who would not have otherwise registered or cast aballot. This could be easily discovered by examining eligible voters toregistered voters to voters who indeed voted controlling for population growth since the decline was first evidenced in the 1960s.

9

specific attention to areas within the education process itself,

which are in need of address.

“Congress, Public Trust and Education,” builds upon

Hibbing’s conclusions and goes further, specifically identifying

the weaker aspects of civic instruction citizens receive.

Textbooks, pedagogy, and the very lack of skill among those

involved in civic education are damaging citizens. Sheer lack of

political knowledge among high school students is problematic;

however, more troublesome, and ignored by the authors are the

dismally low levels of internal efficacy exhibited in the polling

data among students from 1974 through 1996. Like Hibbing, these

contributors are concerned about low levels of trust and what it

ultimately means for democracy, but no one author draws the

connection between how these efficacy levels affect distrust. If

these low levels of internal efficacy translate into low levels

of external efficacy, it is arguable that at some point in the

future, citizens may well pose the question of legitimacy with

respect to the system itself; a point which Cooper rightly makes note

of in the last chapter. In fact, one could argue this likelihood

was evidenced in the debacle of the 2000 presidential election

wherein the Electoral College’s modern utility was very

10

vigorously debated among media, scholars and the public at

large.3

The authors pay particular attention to secondary civic

education, denouncing the focus on “abstract governmental

arrangements,” but fail to define this. The reader can only

surmise that they refer to the pedagogy that reflects theory as

opposed to reality. Very little attention is given to

instructing students on the process of ‘doing the peoples’

business” and therein, lies the fundamental flaw. Their

position, similar to that of an earlier article by Mutz and

Flemming, supports students learning about the deliberative

process. Students should be exposed to the messiness that is

democracy: conflict and compromise, which does not necessarily

connote loss in every sense. It is ironic that Goals 2000 did not

originally mandate civic education and only after significant

lobbying was it added as a requirement. Whether not or why

individual states reject Goals 2000 is unimportant, the imperative

3Rothwell, Jennifer Truran. Prospects for the Electoral College after Election 2000. Social Education. Jan/Feb. 2001. Julian E. Davis, “The Electoral College: What’s the Fix? Take Your Pick,” The Washington Post (11/19/00): Outlook. E. J. Dionne, Jr., “Scrap This System,” The Washington Post (11/9/00): A29; George F. Will, “No, the System Worked,” The Washington Post (11/9/00): A29; Akhil Reed Amar, “The Electoral College, Unfair From Day One,” The New York Times (11/9/00): A23; Fred Barbash, “What Did You Expect? The Framers Were Politicans, Too; That’s Why We Don’t Know Who Won,” The Washington Post (11/12/00): Outlook, B1, 4-5.

11

remains that each state ensures that its citizenry is adequately

prepared to participate in our democratic system.

Respecting those who are responsible for teaching civics and

government, the authors offer a specific criticism, not

particularly at them, but to their lack opportunities for either

adjusting deficiencies in their own education or expanding their

knowledge of the discipline. Programs that would strengthen the

ability of teachers to translate the more subtle aspects of civic

education to their students have only limited impact due to

insufficient funding or financial assistance. Adding further

difficulties for these teachers are the poor-quality materials

they have at their disposal; whether in book form or what is

often the preferred medium of many: video; are at best banal and

need significant improvement if teachers are to utilize them.

Most appalling however, is the condition present in higher

education. Sadly, only two states, Texas and Oklahoma, require

all students taking a Bachelor’s degree from a state university

to have had a separate course in American government, and

notably, at least in one regard, Texas stand shoulders above its

peers, requiring two courses. While it is certainly a disturbing

realization that a person deemed educated by its state has a

poor, if at all, working knowledge of their own government, what

12

might be more problematic are those who pursue a career in

journalism. The notion that the majority of this discipline’s

students, having met no formal requirements for understanding a

bulwark on which our society is based but will be responsible for

reporting or writing on, is disturbing. This is very telling and

merits further consideration if attempts to improve civic

education and public understanding in America are genuine.

Echoing also the sentiments of Schribman, these contributors

indicate some of the responsibility rests with the media and

their negative portrayal of Congress. Even after acknowledging

the dalliances of individual members, the exaggeration and

generalization by the media of this behavior onto the collective

membership is simply surely irresponsible and perhaps unethical

reporting. Like Davidson, Hepburn and Bullock view the media as

having a positive bias in their coverage of policymaking by the

President; however, there seems to be a collective “hinting” that

there lack of understanding the media has for the nuances of

politics, which makes this bias moot. It is commonly understood

that covering the President is far easier than Congress, simply

by virtue of size, but for the media to oversimplify and reduce

the politics of Congressional deliberation as both partisan

bickering (which, undeniably, it is at times) or as a persistent

13

and purposeful attempt to block the presidential agenda is more

damaging. This aspect, if not explained properly or out of

context, contributes to the unrealistic expectations of democracy

and the misunderstandings about the function of congressional

members and the principle of checks and balances intentionally

designed.

While this article was second in preference only to

Hibbing’s work, substantively Hibbing’s research was presented

more concisely and the relevant points discussed in proper scope

in this reader’s view. In a few instances, however, Hepburn and

Bullock appear to have made many more observations based upon

common assumptions within our discipline. For example, in

discussing college freshmen’s responses to questions involving

the importance of politics and the frequency of political

discussions, the typical low figures are presented; but are not

used to support their argument that positive attitudes are

declining nor do they assure the reader that these figures are

not unexpected or atypical which is somewhat telling of their own

misunderstanding of political behavior in this reader’s opinion.

While the articles by Hibbing, Hepburn and Bullock indicate

failings in civic education, the article by Davidson highlights

the weaknesses of Congress and its outright inability to

14

enlighten citizens of the difficulties inherent to the process at

both the institutional as well as individual levels itself.

Davidson underscores the anger and disgust the electorate has for

Congress by citing poll results from Morin and Dewar, which

depict “all time lows” for Congressional approval. However, an

important point which he fails to mention, is the 1992 election

which brought 110 new members into Congress (sixty-three

Democrats and forty-seven Republicans) making it one of the

largest freshmen classes in history. That lack of approval

evidenced by the backlash toward incumbents seems to correlate

with significant action by the electorate indicating some degree

of confidence that elections, which are a vital component of

democracy, are valid can produce positive results; at least

insofar as raising levels of government trust, if not ultimately,

levels of policy trust.

To describe the process of lawmaking as difficult is an

understatement; here one need only recall Barbara Sinclair’s

testament to this. Davidon, to his credit, accurately

characterizes the institution itself as a convolution of

committees and subcommittees, caucuses and informal groups, which

to the average American would likely be incomprehensible and

perhaps duplicitous. Complicating the labyrinth of structure is

15

the arduous task of lawmaking itself. Explaining the process of

introducing a bill and its ultimate passage takes Herculean

effort by those who are scholars of Congress; attempts by the

media to explain this process produces a chuckle at the absurd

picture of the “blind leading the blind” as well as somber

admission that the oversimplifications made by the media that

“money motivates” and is the primary catalyst serves only to

breed further cynicism among voters.

An example used by Davidson to illustrate the complexity of

lawmaking was the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts)

appropriation. While this example indicated a “two step forward,

one step back” style, it is imperative to note that the bulk of

legislation would not take these ‘twists and turns’ but is

indicative of both appropriations bills today and are the ‘nature

of the beast’ with respect to controversial spending. Had

Davidson chosen a less niggling case, this reader might have

nodded more quickly in agreement but that notwithstanding, his

point was made.

Implying that the media does portray Congress correctly when

it is depicted as partisan, assuring readers that if increased

partisanship is perceived there is good reason: party loyalty

scores by interest groups have generally been on the rise over

16

the last generation. However, given the Blacks’ research on the

defection of southern Democrats to the Republicans in the 1980s

through today, the apparent regional schism developing between

the northern and southern Republicans as well as the lack of

mandate received by either party, the question of platform seems

rather innocuous given the rise of voters identifying as

‘independent.’

If partisanship is, in fact, on the rise, then it logically

follows that there would be a decline in Congressional members

characterized as moderate. While the strength of the party

overall has declined, the power afforded the leadership is still

such that members who merely hesitate, let alone reject key party

positions, can be ostracized at minimum. Of course this was

wholly apparent following the midterm elections where many of the

northern Republicans in the House were denied key appointments

after they refused to march in ‘lockstep’ with their southern

leadership’s dictates.4 If former Senator Rudman’s comment that

the ‘spirit of civility is drying up” is indicative of the

political environment, the other authors must not unfairly omit

Congressional behavior from the ‘puzzle.’ Based upon Davidson’s

4 By Jim VandeHei and Juliet Eilperin. GOP Leaders Tighten Hold In the House Hastert, DeLay Reward Loyalty Over Seniority. Washington Post. Monday, January 13, 2003; Page A01

17

article, one is left to conclude that if the media depicts

Congressional members as partisan and petty, they are not being

entirely manipulative or deceptive, nor if the public perceives

Congress as bickering over minutia, is their perception without

merit.

Davidson summarizes by state that Congress must come to its

own defense. Much of what is done by the membership is hardly

demystified by C-SPAN and what may be more helpful are voice-

overs or non-partisan commentary might markedly improve citizens’

understanding of what goes on in that great hall.

Notwithstanding an improved public relations campaign, structural

reorganization, easing the burden of the individual legislator is

suggested as well. However, would improved public relations,

structural changes or improved media coverage really make a

difference? Mutz and Flemming’s article “How Good People Make

Bad Collective Choices” seems to indicate otherwise.

Exploring Fenno’s “paradox” on a macro-level, the distrust

exhibited by the pubic seems to stem from the different standards

of judgment people employ for evaluating individuals and

institutions. This article, while providing much support for the

wider phenomenon of distrust, seemed to be based upon common-

sense suppositions about how humans view their world, both from

18

near and far. Again, their research indicates that the decline

of public trust is consistent across many larger institutions,

but going further, they find a general consistency with logic of

Fenno’s paradox (Figures 5.1, 5.2, 5.4).

The authors are also comfortable with positing that the

phenomenon of increasing distrust is not limited to Congress, but

call attention to the apparent contradiction present when

comparing the collective body of doctors and the bigger economic

picture to the larger body of Congress. In this instance it

appears those interviewed are ‘missing the forest for the trees.’

How can the entire collective, in either the case of the economy

or the medical profession, be substandard yet the assemblage,

taken individually, be profoundly better? An interesting

question and one addressed simply as “it is the way humans view

their world.” It appears that we seek to validate personal

choices internally as some ego-protecting mechanism and when our

personal choices are no longer valid, they are rejected and join

the ranks of the larger, more poorly viewed collective.

Mutz and Flemming attribute part of the pessimism against

Congress to simple errors in human awareness or sampling bias.

The disjuncture is the result of both positive and negative

perceptual bias. They describe both as likely deriving from

19

media coverage as this is where most citizens obtain their

information about Congress. The size and finances of the media

source are key, which is evident when surveying the amount and

type of coverage given. Smaller, less-prosperous media outlets

rely less upon investigative reporting and more upon information

provided them by Congressional members themselves. Logically,

this results in often more positively biased coverage;

conversely, larger media outlets with broader circulation have

less positively biased coverage due to their ability to seek out

and find information. This “booster” role played by smaller

media outlets serves to promote members to their constituents,

reinforcing Fenno’s “paradox.”

Ultimately, this article implies however, that distrust is a

product of merely being human. The authors do not appear to

offer solutions to this problem, if being human is that, but

disagree with Hibbing’s hypothesis of increased civic education

as a potential solution. Perhaps, this may be an indicator of

their unconscious realization that the model of the efficacious

citizen has changed, as was alluded to earlier in this review.

In any event, simply ensuring Americans learn about our

democratic institutions and processes would not be sufficient

according to Mutz and Flemming; mere exposure to theory is

20

insufficient and citizens must be compelled to understand the

reality which is the” messiness of democracy.”

Citizens must be exposed to exercises in deliberative

discussions about tough policy issues, learning that there can be

reasonable positions held by all involved and that the answer

must lie in the melding of those ideas. Implicit in this

suggestion is the point that whether or not a viable solution

emerges during the discussions, trust would improve if citizens

understood the very process of decision making in its functional,

but inherent disorder and ultimately provide an accurate

impression of the responsibility Congress has within the process.

Many political scholars would quickly admit to a measurable

lack of trust in government exhibited by the electorate, but in

terms of providing a source of concrete explanation for this

phenomenon, this collection of articles falls somewhat short. It

appears that this problem, with its complicated nuances, may not

be explainable by any measurement or poll. In Cooper’s final

chapter, he again, volubly, attempts to connect all the articles

for the reader. He effectively defines the levels of trust as a

reflection of our feelings of alienation and appropriately

provides the analogy of a “ladder,” arguing that there are strong

ties between public perception of legitimacy and compliance with

21

policy, which are both indices, related to public trust.

Congress is the lighting-rod for the expression of public

distrust, and Cooper is rightly concerned that the persistently

high levels of distrust could ultimately pose a threat to our

system’s stability.

The contradiction of what we learn, in terms of our ability

to affect government, and the remoteness we feel to it, causes

Cooper to vacillate between why citizens feel this distrust. He

first says our perception of the aspiration or our expectations

of democracy are the cause and then, no, this is too simplistic;

ending that it derives from the ambiguity of the values and

beliefs we use as a yardstick for judging the behavior and

subsequent decisions of our representatives. Cooper’s concluding

remarks become largely difficult to follow and so verbose as to

be tedious; however, at a later point he does return to the

“ladder of alienation” analogy and attempts to solidify his final

thoughts in relation to it. Using this ladder analogy to

describe the ebb and flow of distrust, Cooper treks through

history to illustrate that, in fact, levels of distrust reflects

the public’s acceptance or rejection of policy and this

oscillation rests upon subsequent generations to rethink the

scope and role of government within society, both domestically

22

and globally. He accurately depicts the short-run

disappointments with the long-term retrospective view as lending

support to the degree to which generations are able to reassess

government’s scope. One might note however, that those policy

decisions that cause these oscillations are largely the result of

more than a minor crisis.

There is little conjecture about the speed and breadth of

change society has experienced both in terms of demographics as

well as the governmental institutions themselves, which have been

modified, largely, to address the changes. In fact, Cooper notes

that the American public has placed even more demands upon

government to manage the larger issues of general welfare and

these increased demands are almost certain to produce

discontentment in both the short-run policy levels and the short-

run levels of public trust. Coupled with the media’s less than

neutral framing of the issues, particularly in times of crisis,

the increased likelihood of grandstanding by individual

politicians during said times is bound to produce a public view

of those involved in the process as well as the process itself,

as seamy.

Cooper, benefiting from the articles submitted by others,

sees fit to conclude with specific remedies to address low levels

23

of trust. He first states that the remedy for distrust cannot

simply rationalize the professional versus the citizen as

lawmaker, nor will simplistic explanations of how a bill becomes

law solve the dilemma. We must somehow reeducate our citizens

to accept innovative and ‘statesman-like” behavior in our

politicians; eschewing the glitter of ‘talk radio” and prime-time

political pundits

with their consistently negative and hyper-cynical views of

government. We often cite our founding fathers, and can, even

sup through the twentieth-first century name members of Congress

who were genuinely admired and considered to be leaders working

for the general welfare; though we are losing them regularly as

this reader stops to recall a wonderful piece on the political

career of Moynihan a few weeks ago following his death USA

Today.5 Today, unfortunately more often than not, a politician

who attempts innovative policy reform would risk swimming against

the tide of public opinion or challenging a party position only

to find him or herself rewarded with defeat in the next primary

or election.

5 John Machacek. “Scholar, politician Moynihan dies at 76 Was known as 'intellectual statesman'“ USA Today. Pg 11A March 27, 2003.

24

Cooper agrees with former Senator Bradley that the

deleterious problem of money in politics must be addressed

effectively and the media’s negligent treatment of the political

process brought under control. On reform, former House Speaker

Thomas Foley once said, “It takes a real carpenter to build a

barn, but any jackass can kick it down.” Structural reform may

not be quick in coming, and if one chooses to call

Shays-Meehan/McCain-Feingold campaign reform that, one could but

this reader question the quality of the lumber used to build this

barn. Genuine reform is difficult because of the complexity of

our society and the difficulty government has in dealing with it.

Therefore this reader would argue the best opportunity and

perhaps most promising area to affect decline in trust may lie at

the feet of educators, which leads to Cooper’s final

recommendation.

In order for Americans to have an appreciation for their

delicate but long-lived democracy, they must be taught to put

conflict and compromise in their proper perspective, to use the

words of Cooper. Civic education should concentrate on the

tensions produced by a body politic seeking redress of societal

ills, and second only to that, the structure and fundamental

functions of the institutions of democracy themselves.

25