Caseload midwifery Evaluation 2011-2014

Transcript of Caseload midwifery Evaluation 2011-2014

Evaluation of the

Caseload

Midwifery

Model of Care July 2011 – June 2014

Blue Mountains District Anzac Memorial Hospital

Final Report

Mel Lewis

2

Table of Contents Index of Figures .............................................................................................................. 4

Index of tables ................................................................................................................ 5

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 7

RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................................... 13

INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 18 Background to the report .......................................................................................................................................... 18 Aims .................................................................................................................................................................................... 19

LOCAL HISTORY AND CONTEXT ...................................................................................... 21

DEFINING THE TERMS .................................................................................................... 24

POLICY AND EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE MODEL .......................................................... 28 Establishment ................................................................................................................................................................ 29 Annualized salary agreement .................................................................................................................................. 29 The model ........................................................................................................................................................................ 31 Physical workspaces ................................................................................................................................................... 36 Women’s care journey ................................................................................................................................................ 37 Measures of birth continuity ................................................................................................................................... 42

WORK FLOW THROUGH THE MATERNITY UNIT .............................................................. 45 Booking into Blue Mountains hospital ................................................................................................................ 45 Who provides antenatal care? ................................................................................................................................ 45 Where do caseload women give Birth? ............................................................................................................... 46 All births at BMDAMH ................................................................................................................................................ 47

MATERNAL CHARACTERISTICS ........................................................................................ 48 Antenatal .......................................................................................................................................................................... 51 Admissions ........................................................................................................................................................................ 51 Plurality ............................................................................................................................................................................. 51

Labour ............................................................................................................................................................................... 51 Onset of labour ............................................................................................................................................................... 51 Induction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 52 Augmentation ................................................................................................................................................................. 53 Analgesia .......................................................................................................................................................................... 54

Birth .................................................................................................................................................................................... 54 Method of birth .............................................................................................................................................................. 54 Indications for caesareans-‐no labour (elective) .............................................................................................. 56 Perineal status after vaginal birth ........................................................................................................................ 57 Post-‐partum haemorrhage (PPH) ......................................................................................................................... 58

Babies ................................................................................................................................................................................ 58 Gestation ........................................................................................................................................................................... 58 Birth weight ..................................................................................................................................................................... 59 Live births ......................................................................................................................................................................... 59 Apgar score ...................................................................................................................................................................... 60 Admission to nursery ................................................................................................................................................... 61

Postnatal ........................................................................................................................................................................... 61 Breastfeeding .................................................................................................................................................................. 61 Length of stay after birth ........................................................................................................................................... 61 Home visits ....................................................................................................................................................................... 61

Attitudes to Professional Role (ATPR) ................................................................................................................ 62

3

Industrial Agreement Questionnaire (IQ) .......................................................................................................... 65 Work hours ...................................................................................................................................................................... 66 On call ................................................................................................................................................................................ 66 Yearly caseload .............................................................................................................................................................. 66 Caseload manageability ............................................................................................................................................. 67 Continuity of care .......................................................................................................................................................... 68 Professional supervision & Support ...................................................................................................................... 68 Midwives suggestions for change ........................................................................................................................... 69 Discussion ......................................................................................................................................................................... 71

WHAT THE WOMEN SAY – SURVEY RESPONSES ............................................................. 72 Methods ............................................................................................................................................................................ 72 Findings ............................................................................................................................................................................ 74 The women ....................................................................................................................................................................... 74 Model of care ................................................................................................................................................................... 75 Did women choose their model of care? .............................................................................................................. 75 Reasons for choice or allocation to a model of care. ..................................................................................... 76 Satisfaction with information -‐ Enabling informed choices ....................................................................... 77 Satisfaction with the information -‐ About the scope of services available at BMDAMH ............... 77 Were women’s wishes and needs respected and met by the service? ..................................................... 77 Did women attend parenting classes? ................................................................................................................. 77 Did women value antenatal information given by midwives or doctors? ............................................ 78 Caseload care – did women feel supported by their midwife? .................................................................. 79

The postnatal period ................................................................................................................................................... 82 Did women receive adequate information about the postnatal period? .............................................. 82 Did women feel confident about going home with a new baby? .............................................................. 82 What method of infant feeding did women choose? ...................................................................................... 82 Did women feel supported with, and informed about their choice of infant feeding? .................... 82 How long did women breastfeed for? ................................................................................................................... 83 Did women receive adequate information about community supports? ............................................. 83

Women have their say – Themes of importance ............................................................................................. 83

Appendix 2: Blue Mountains Hospital Obstetric Criteria ................................................. 93

Appendix 4: Industrial Agreement Questionnaire – Caseload Midwifery Model ............. 95

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................... 98

4

Index of Figures

Figure 1: Births per financial year trend, Koorana unit 22

Figure 2: Continuity of care models as reported in the literature 27

Figure 3: Proportion of birth attendance for primary midwife, Koorana unit 43

Figure 4: Proportion of births each primary midwife attended 44

Figure 5: Proportion of women per model of antenatal care, January 2011-June 2014 46

Figure 6: All Koorana unit births Jul 2011-Jun 2014 48

Figure 7: Age of Koorana mothers compared to NSW birth cohort 49

Figure 8: Proportion of ATSI women who birthed at Koorana unit 2011-2014 49

Figure 9: Parity group for mothers who gave birth in the caseload triennium 50

5

Index of tables

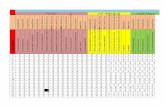

Table 1: Koorana caseload midwife staffing profile July 2011-June 2014 30

Table 2: Relational continuity between women and midwives at Koorana 41

Table 3: Booking-in visits at Koorana, according to intended maternity care provider 45

Table 4: No & proportion of women who received antenatal care, according to model 46

Table 5: Reasons why caseload women did not birth at Koorana, Jul 2011-Jun 2014 46

Table 6: Onset of labour type for all births, per caseload year 52

Table 7: Onset of labour profile for baseline and caseload triennium 52

Table 8: Method of labour induction 52

Table 9: List of indications for induction of labour 53

Table 10: Mode of birth for all mothers 54

Table 11: Comparison of mode of birth between mothers in baseline and caseload trienniums 55

Table 12: Indication for caesarean section –no labour 56

Table 13: Perineal status of vaginal births by instrumental and non-instrumental birth 57

Table 14: Blood loss at birth 58

Table 15: Blood loss at birth, vaginal v’s caesarean births 58

Table 16: Gestational age groupings 59

Table 17: Birth weight categories of infants 59

Table 18: Live birth and perinatal death rate 60

Table 19: Respondents according to parity, per birth year 74

Table 20: Respondents according to model of care, per birth year 75

Table 21: Caseload women, responses to feeling well supported per stage of maternity care 79

Table 22: Proportion of women who felt supported in labour & birth, according to primary midwife attending intra-partum care 79

Table 23: Numbers of positive and negative comments according to stage of maternity care 80

6

Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the caseload midwives at BMDAMH for their guidance in

completing this report; Robyn Carroll, Sally Whitson, Fiona Schonstein-Scott,

Barbara Rose, Jane Rutherford and Anne Couttes. To Peta Millard and Julie

Lahache (core staff) for assistance in folding and mailing out surveys to women. To

Ann Yates (District Nurse Manager of Midwifery Services) for review and addition of

some recommendations. To Juanita Taylor, (CMC Nepean) for assistance with file

audits and obstetriX reports. Therese Ross (NUM, BMDAMH) for your patience and

support, and supply of the design for the title page. To all the women who have

kindly taken the time to complete the surveys and leave valuable feedback, and all

those either directly or indirectly involved in the Caseload midwifery model at

BMDAMH.

*Corresponding author at: c/o Koorana Unit, BMDAMH, Woodlands Drive, Katoomba. E-mail address: [email protected] (Mel Lewis)

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Overveiw

The Blue Mountains District Anzac Memorial Hospital (BMDAMH) Caseload

midwifery model of care was established by the Nepean, Blue Mountains Local

Health District (NBMLHD), in July 2011. The caseload model was set up in

response to the Towards normal birth - NSW Health policy directive (2010)[1], and

sought to address long-standing issues with recruitment and retention of midwifery

staff, as well as community concerns about the continuation of maternity service

provision at the BMDAMH[2]. The aim of the caseload midwifery model was to

improve the quality of maternity care for women and babies at the Blue Mountains

Hospital, and to also improve the productivity and work experience of midwives

working in the service. The caseload midwifery model became fully staffed in June

2013, and data for this evaluation was collected from July 2011 to July 2014 (three

complete years of caseload operation).

Methods Quantitative data

Retrospective maternal and infant health outcome data for all BMDAMH (Koorana

Unit) births are reported on for the three years of caseload operation (July 2011-

June 2014 – Caseload triennium). The proportion of caseload clients in the

caseload triennium increased to over 95% by the end of the reporting period (table

4). However not ALL births reported on were caseload clients. This is because

caseload midwives are generally called on to provide intra-partum care for all

women birthing at the Koorana unit, irrespective of the model they are booked

under, and have undoubtedly influenced the standard of midwifery care across the

whole unit. For this reason, ALL BMDAMH birth data was used to report maternal

and infant health outcomes, to evaluate the effect that the caseload model has had

on the unit as a whole.

A further three years of retrospective birth data for BMDAMH (July 2008 – June

2011 – Baseline triennium), was used when available, to compare maternal and

infant health outcomes before and after the onset of the caseload model. When

8

baseline data was not available, comparisons were made in some cases with

published NSW perinatal data[3], to help contextualize quantitative findings.

Quantitative perinatal data was obtained through ObstetriX and reported in excel

format. The data was then cleaned and analyzed using IBM-SPSS© Statistical

software for Mac (version 22), with alpha significance levels set at 0.05 (95%

confidence) for all Chi2 tests performed on categorical perinatal variables.

Attitudes to the professional role of caseload and core midwives are measured with

a quantitative survey instrument (appendix 3).

Qualitative data

Data is collected from the patient quality satisfaction survey, and the industrial

questionnaire to caseload midwives. Responses were de-identified, coded and

analyzed for content and themes.

Findings The establishment of the midwifery caseload model of care represented a

significant change in service provision for women booking into the BMDAMH. The

service has only been fully staffed for the last year of the evaluation (June 2013-

June 2014), but has demonstrated considerable success towards the aims of

improving service provision and standard of care since commencement. The

caseload midwifery model delivers woman-centered, continuity of care for most

women who book into the Koorana Unit, and has improved the quality and safety of

maternity care provided at the BMDAMH. The findings from the quality survey

suggests that having a known midwife in pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period,

has enhanced the experience for women and families as users of the service.

Maternal and infant health outcomes

The following statistically significant improvements (p<0.05) were found when

comparing maternal and infant health outcome data from the caseload triennium, to

the baseline triennium:

• Increase of 9.5% in the proportion of women who labored spontaneously (from 59.3% to 68.8%).

• A 4% reduction in labour augmentation rate (from 10.9% to 6.9%)

9

• A 2% reduction in the epidural rate (from 18.1% to 16.1%)

• A 5.3% reduction in the total caesarean section rate (from 28.9% to 23.6%) • A 6.6% reduction in the elective caesarean rate (from 19.7% to 13.1%).

• A 23.9% increase in the proportion of babies born after 40 weeks gestation,

from 20.9% to 44.8%

• A 50% reduction in the proportion of babies born with low Apgar scores, five minute <7), from 2.2% to 1.1%

The following changes were also observed when comparing the caseload cohort

to the baseline cohort, but were not statistically significant (p>.05).

• A higher proportion of primiparous women birthed with caseload (38%)

compared to before (35.2%)

• A 2.9% reduction in the induction of labour rate from 21% to 18.1%

• A 5.1% increase in the normal vaginal birth rate from 63.4% to 68.5%.

• A 2.2% decrease in the episiotomy rate from 5.9% to 3.7%.

• A 0.7% decrease in the post-partum haemorrhage rate (>500mls) from 19.3% to 18.6% for all births (see page 58 for breakdown and discussion)

• A 1.7% increase in the proportion of babies born with a birth weight over 4000 grams from 15.3%-13.6%

• A reduction in the proportion of neonatal transfers to higher levels of care.

• A 0.9% increase in the proportion of third and forth degree tears, from 2% to

2.9%.

• A 0.4% decrease in the live birth rate, from 99.8% to 99.4%, although all 4 cases were associated with fetal anomalies in the caseload cohort, and neonatal deaths not related to labour (see page 59-60 for details).

What the midwives say

The attitudes to professional role (ATPR) questionnaire, highlighted:

• Caseload midwives experience higher levels of professional satisfaction than core midwife do in their respective roles, and feel that they have more opportunities to make decisions about care.

10

• Core midwives perceived a higher degree of professional independence than

caseload midwives within their scope and expectations of practice.

• Caseload and core midwives both affirmed strong support from their midwifery colleagues

• Core midwives perceived a higher level of support from obstetric colleagues than caseload midwives, but both groups felt that obstetricians were supportive in general.

• Both groups perceived a relative lack of managerial support.

• Core midwives felt that they have enough time to do their jobs properly,

whereas caseload midwives felt there is often not enough time.

• Both groups did not agree that their work is stressful.

• Both caseload and core midwives felt that they have enough opportunities to provide personalized care to women.

• Core midwives felt that they had more time to give to women than caseload

midwives.

• On the whole, both groups were satisfied in the domain of client interaction, with caseload midwives feeling more satisfied with the level of continuity they offer women.

• Caseload midwives felt that they had more opportunities for professional

development than core midwives, as well as the opportunities to develop midwifery skills in the course of their work.

• Both groups felt that they had sufficient midwifery skills for their work, with

caseload midwives feeling particularly confident in this area. The industrial questionnaire (IQ) of caseload midwives indicates:

• Caseload midwives were satisfied with the arrangements for covering each other’s caseload whilst on a day off and flexibility for having days off.

• Midwives who regularly come in to work on their days off to care for their own women had a higher level of satisfaction with the continuity they could offer. Midwives who do not regularly come in in their own time, were not satisfied with the continuity of care component of their work.

• Midwives receive good professional support from each other

• Midwives are satisfied with the degree of professional development they can

engage in.

• Midwives on the whole perceive a lack of management support.

11

• The biggest frustration for caseload midwives in the past, has been filling

shifts on the core roster, and short staffing. This has impacted on their capacity to provide continuity of care to women on many occasions over the past three years. Improved staffing levels in 2014 have mostly rectified this problem.

• Caseload midwives on the whole, would like to change the model’s working

configuration to two smaller groups, providing on-call care to a smaller group of women in the future.

What the women say – Survey responses

• 95% of caseload clients felt that their wishes and needs were respected by the service.

• 92% of women felt well supported in the antenatal period, 93% in labour and

birth, and 96% felt supported in the postnatal period at home.

• Having their primary midwife provide care in labour and birth increased women’s satisfaction levels to 95.7% (from 89.6% when the primary midwife could not be present for labour or birth).

• Women valued having their own midwife, and feedback was overwhelmingly

positive.

• The small number of criticisms centered on; problematic communication (via text messages or when women did not get a response from a midwife), perceiving that their choices were not respected in some way, and a lack of warmth and connection with the primary midwife.

• The most common criticisms of the postnatal period was conflicting

breastfeeding advice whilst in hospital, and feeling pressured to go home too early.

• Besides the major theme of appreciation for the hospital and caseload

service, the following sub-themes emerged:

! Continuity and connection with the primary midwife is important to women.

! ‘Please offer vaginal (normal) birth after caesarean section (VBAC’s

or NBAC’s)’

! Women want the opportunity to birth in water at the Koorana unit.

! Women do not want to be rushed into early discharge from hospital.

! General concerns about the staffing and working conditions of midwives.

12

Conclusion

The first evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of the caseload model finds that

the model has been able to meet the aims of improving maternity care provision for

mothers and babies at the Koorana unit at the BMDAMH, evidenced by significant

decreases in the caesarean section rate, augmentation rate, use of epidural

analgesia, and babies born with low Apgar-scores over the three year period of

operation. The evaluation supports the available evidence that being cared for by a

known midwife throughout pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period enhances the

women’s experience of birth. The new model has succeeded in improving the

retention, productivity and satisfaction of midwives in the Koorana unit, and

contributed to a relative lack of maternity service interruptions at BMDAMH since

2011. The following recommendations are provided to support the continued

provision of the caseload model to women in the Blue Mountains region.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Governance Recommendation 1: Formulate business rules for the operation of the caseload

model, and clarify the processes around the acceptance (booking-in) and ongoing

care of non-caseload as well as caseload women receiving care in the Koorana

unit. Include guidelines about how the caseload model will manage increased

demands for its services (i.e. an ‘overflow’ of bookings in certain months).

Rationale and discussion: pages 31-41& 70

Recommendation 2: Investigate and strengthen sources of managerial support for

the model. Rationale and discussion: pages 63, 69 & 71

Continuity of care Recommendation 3: Support full staffing levels for core and caseload midwives in

the Koorana unit, to enable to caseload model to provide enhanced continuity.

Rationale and discussion: pages 42, 67, 71, 87-88.

Recommendation 4: Support the re-configuration of caseload midwives on-call

arrangements, to enhance the continuity of labour and birth care by primary

midwives. This would most likely resemble two groups of three or four midwives

who care for a smaller pool of women, and would relinquish the need for monthly

‘meet and greet’ sessions for all midwives and clients in the practice.

Rationale and discussion: pages 26, 30-32, 41, 68, 70-71.

Recommendation 5: In consultation with consumers, revise the processes of

communication between caseload midwives and women. In particular, the use of

‘text’ messaging to relay clinical information.

Rationale and discussion: pages 35 & 81

Clinical service provision Recommendation 6: Normal birth after caesarean section (NBAC, otherwise

known as VBAC) be included in the obstetric criteria for birthing at the BMDAMH, in

line with the NSW Health Guidelines for teired-level three maternity services

14

(2014)[4] and draft Maternity and Neonatal Service Capability Framework[5]. Offering

VBAC options at BMDAMH will ensure compliance with the NSW Health guidelines,

increase birth numbers in the Koorana unit, reduce the need for local women to

labour and birth at Nepean Hospital, improve continuity of care for women booked

at Koorana, give more women the opportunity to persue a normal birth, and

enhance the patient experience. The most common reason for healthy pregnant

women to have their babies at Nepean hospital is because they want a VBAC,

there are many more women who elect a repeat caesarean section at BMDAMH

because they do not want to travel to Nepean hospital. Offering VBAC services at

the Koorana unit is consitant with the goals of the Towards Normal Birth–NSW

Policy Directive[1], will reduce the strain on maternity services at Nepean Hospital,

and will help reconcile the long-standing expectations of local birthing community.

Rationale and discussion: pages 23, 47, 56, 85, 91-92.

Recommendation 7: Establish a working group to test and review occupational

health and safety concerns associated with conducting waterbirths in the Koorana

unit, in line with NBMLHD clinical and occupational health guidelines.

Rationale and discussion: pages 23, 85-86 & 92

Recommendation 8: That credentialled midwives perform well baby discharge

checks on neonates as per NBMLHD policy, to streamline and expediate the early

discharge process when clinically appropriate for mother and baby.

Rationale and discussion: page 40.

Recommendation 9: Ensure adequate discussion and preparation is provided to

women in the antenatal period, about the anticipated postnatal hospital stay and

home visiting supports available, in order to address consumer fears and

misconceptions about early discharge. Rationale and discussion: pages 86-87.

Recommendation 10: Investigate the feasability of enhanced primary caseload

care in the community, namely; antenatal visits, and early labour assesment and

support in the woman’s home. Rationale and discussion: pages 36-37 & 40

Recommendation 11: Conduct a clinical audit and review of all births resulting in

post-partum haemmorhage (PPH) and 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears at the

BMDAMH. Engage with midwives and obstetricians about ways to improve the

recording, reduce the proportion of births ending in PPH and anal sphincter injury,

and prioritise prospective monitoring and reporting of these outcomes.

Rationale and discussion: pages 57-58.

15

Recommendation 12: For periods of no obstetric or anaethetic cover to BMDAMH,

consider continuing birthing services by operating Koorana as a teired level-2

maternity unit as per Maternity and Neonatal Service Capability Framework[5], for

category-A[6], low-risk women rather than closing for all birthing services.

Recommendation 13: NBMLHD explore opportunities to engage with eligible

midwives by providing visiting rights for midwives to provide intrapartum services at

BMDAMH and the LHD.

Training and education Recommendation 14: Ensure caseload midwives have access to DAWN

(Discharge of the well neonate) training through the Nepean training program, and

are well supported by paediatric staff to establish and maintain competency in this

domain. Rationale and discussion: page 40. Recommendation 15: Support caseload midwives to complete a professional

credentialling process such as the Midwifery Practice Review (Australian College of

Midwives), and achieve NMBA ‘eligibility’. This would contribute to a culture of

professional reflection, and enhance the awareness of the ANMC Competency

Standards for the Midwife.

Recommendation 16: Maintain strong education and support linkages with

Nepean Hospital midwifery services, to ensure Koorana midwives have access to

the full range of professional support and education. Ensure that any rotations to

Nepean Hospital are planned well, to ensure women are prepared and informed

about their primary midwife being on away on rotation.

Rationale and discussion: pages 42, 80-81.

Recommendation 17: The Koorana unit consider acheiving BFHI (Baby Friendly

Health Inititative) accreditation, to improve the quality and consistency of

breastfeeding information given to women whilst in hospital.

Rationale and discussion: pages 82-83.

Resources Recommendation 18: Source additional laptops for use in the community for all

caseload midwives. Rationale and discussion: pages 36-37.

16

Recommendation 19: Authorise remote modum access for hospital laptops, in

order to access obstetriX and iPMs patient records during antenatal visits outside of

hospital grounds. Rationale and discussion: pages 36-37.

Recommendation 20: Antenatal clinic rooms to be booked in advance to avoid

overload in the unit. Rationale and discussion: page 36.

Feedback and information Recommendation 21: Continue to collect and report on all caseload clinical

outcomes. Ensure caseload midwives collect and maintain their own birth statistics.

Rationale and discussion: page 36.

Recommendation 22: Commence re-design of the quality satisfaction survey

instrument to simplify future analysis and reporting of consumer satisfaction.

Ensure all women who birth at the Koorana unit have the opportunity to provide

feedback on their experience of the service, and their individual caseload midwife.

Rationale and discussion: pages 72-73.

Community partnerships and cultural responsivness Recommendation 23: To support an enhanced focus on primary health care in the

community by forging partnerships with community facilities and services such as;

Women’s health and resource centre, Aboriginal resource centre and youth

centers. To explore options of antenatal care provision outside the hospital in such

venues, as appropriate to the woman (this is dependant on meeting

recommenndation 19). Rationale and discussion: page 37.

Recommendation 24: Foster partnerships with local Aboriginal women and

services to understand how the caseload midwifery model can better meet the

needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander birthing women in the region.

Rationale and discussion: pages 18 & 49.

Recommendation 25: Consider the development of a consumer reference group

for the Koorana unit, ensuring representation of socially disadvantaged or

marginalised members of the community. Rationale and discussion: pages 18 & 91.

Promotion of the caseload service Recommendation 26: That the BMDAMH engages midwives, local woman,

community stakeholders and GPs in publicising and showcasing the acheivments

17

of the caseload midwifery service at BMDAMH. Consider a Koorana caseload

service ‘page’ under the NBMLHD service directory, or multimedia promotion of

service. Rationale and discussion: pages 22-23 & 67.

Recommendation 27: Address community perceptions about the Koorana unit

being ‘closed’ by engaging local consumer groups and the media to promote the

service. This will help address the current unused capacity of the caseload model.

Rationale and discussion: pages 22-23 & 67.

18

INTRODUCTION

Background to the report In January 2014 I was approached by the Midwifery unit manager (MUM) to

undertake an evaluation of the caseload midwifery model at the Blue Mountains

District Anzac Memorial Hospital (BMDAMH). A submission made by a previous

MUM in July 2013, was successful in obtaining funding ($3,840) for the evaluation

(as part of the ‘Nurse Strategy Reserve Initiative’ (NSRI) funding process, stream

three; “Evidence-Based Patient Focused programs that develop midwifery practice

and knowledge”).

The initial NSRI proposal aims were to:

• Evaluate the resources available within the caseload midwifery model, with a

focus on the most efficient, and cost-effective patient journey through the

service.

• Review the collaboration and job satisfaction of core midwives as well as

caseload midwives.

• Identify current and future educational needs of caseload and core midwives.

• Identify ways to increase service provision to the community, particularly the

local indigenous community.

• Reporting on perinatal indicators; birth, breastfeeding, epidural and perineal

trauma rates.

• Report on the patient, demographical characteristics using the service.

• Highlight future innovations that could be adopted.

After resurrecting the document, amendments were made in consultation with the

Local Area District Midwifery Manager, current MUM, and caseload midwives, in

line with the current needs of the service. A concurrent initiative to specifically

identify, and provide, for the educational needs of midwives has since been

undertaken by the area district midwifery manager, and as a result has been

omitted from this evaluation. It was thought that a formal economic analysis would

best evaluate ‘cost-effectiveness’ of the caseload model, but unfortunately this was

beyond the scope and resources available for this report.

19

Extensive community forums (Appendix 1) were held with women in the Blue

Mountains local government area in 2008, as part of the proposal to reform

maternity services at BMDAMH[7]. Some community concerns have been

addressed over this time by the adoption of a caseload midwifery model of care, but

for this reason as well as time and resource limitations, we did not repeat

community consultations of 2008.

Aims The overarching aim of this evaluation is therefore to report on the clinical

effectiveness, quality and sustainability of the BMDAMH caseload model.

The specific objectives were to:

1. Undertake a process, impact and outcome evaluation of the Blue Mountains

Caseload Midwifery Model, using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

2. Describe the model of care, and the women’s journey through the service.

3. Evaluate protocols and guidelines used in the context of supporting

maternity services.

4. Identify significant emerging issues that may arise during the course of the

evaluation.

5. Outline and provide support to a clinical governance framework, to ensure

that all those involved in the model of care are accountable for ensuring high

standards. The goal being, to create an environment in which excellence in

clinical care will flourish.

The need for an evaluation is somewhat overdue, with the service being in

operation for over three years now. Perinatal outcomes under the caseload model

of care are reported over a three-year (triennium) period from July 2011 to June

2014. Data analysis therefore did not commence until after June 2014, to allow for

the availability of three full years (caseload triennium) of retrospective birth data.

20

Information sources

Consultations and information

Therese Ross, (Midwifery Unit Manager) Women and Children’s Unit, BMDAMH.

Anne Yates, (District Nurse Manager, Midwifery), Nepean.

Dr Anmar Mariud (Staff Specialist - Obstetrics), BMDAMH.

Dr Ruby Rashid (Registrar – O&G, BMDAMH)

Andrea Williams (General Manager), BMDAMH

Juanita Taylor (Clinical Midwifery Consultant), Nepean.

All caseload midwives, BMDAMH

All core midwives, BMDAMH.

Surveys

The Maternity unit quality satisfaction survey

Industrial questionnaire

Attitudes to professional role

Demographic data

Information management Group (IMU), NBMLHD

Blue Mountains City Council

Australian Bureau of Statistics

ObstetriX database reports

Perinatal data

ObstetriX database reports, raw in excel format

ObstetriX perinatal reports

NSW Government Health Stats

Bookings, transfers, model of care, and Continuity-of-care data

Caseload midwives diaries

Ward bookings diary

Patient medical records files.

Ward transfer register

ObsetriX reports.

21

Nursery admission register

Caseload midwives – participation and feedback

A participatory action research framework (PAR)[8] has guided the conduct of

information exchange with midwives for this evaluation. Interim reports have been

shared and discussed with midwives and management as they become available.

This enables verification of findings as well as affirming experience, and affecting

change collectively within the caseload group.

Other collateral outputs from this evaluation have included the supply of individual

birth databases and statistics to all caseload midwives in electronic format for use

in professional credentialing.

LOCAL HISTORY AND CONTEXT The Blue Mountains District ANZAC Memorial Hospital is situated within the Blue

Mountains Local Government area (LGA) comprising 26 townships[9]. The hospital

is within a five-kilometer radius of the Three Sisters rock formations, which forms

part of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage area, and attracts many tourists

each year. The Blue Mountains Aboriginal community is made up of many Gully

and non-Gully Darug and Gundungurra peoples[10]. Fertility rates for women who

reside in the Blue Mountains region remain above the national average, at 2.02

children per women, however the birth rate across the Blue Mountains LGA has

declined by almost 10% over the last decade[11].

In 2012, there were 810 women giving birth from the Blue Mountains LGA, with only

219 (27%) birthing at the Blue Mountain Hospital[11, 12]. Nepean hospital cares for

the majority of women who do not give birth at Blue Mountains hospital, and

Nepean Private hospital cares for another smaller proportion of Blue Mountains

women. The Blue Mountains LGA has a higher than average home-birth rate

(second highest in NSW)[13], and features a vibrant and politically engaged home

birth community, where several independent midwives provide maternity care to

women in the region.

22

A maternity unit was established at the Blue Mountains Hospital in 1945 and has

undergone two significant renovations and upgrades over this time. The original

maternity wing was known by the Indigenous name of ‘Koorana’ (to bring forth the

young). The name faded into obscurity for decades before being restored by the

hospital Aboriginal reconciliation committee in 2012. The Koorana unit now has

eight single maternity beds, two birthing suits, and one neonatal bed. The majority

of women who birth at Koorana come form the Upper Mountains area (66%), and

this declines to 18% from the mid Mountains, and 16% for the lower Mountains

area[12], which is geographically closer to Nepean hospital in Sydney.

A drop in the number of births at the BMDAMH since 2008 (see fig. 1), is evident

following intermittent maternity service disruptions in 2008 and 2009[14]. The

inability to attract specialist obstetric, anesthetic, and midwifery staff at BMDAMH

led to birthing service closures, resulting in women being transferred via ambulance

to Nepean hospital in labour. Whilst intra-partum transfer was considered to be the

safest option for women, media and parliamentary attention [15, 16], given to the

suspension of birthing services, has undoubtedly contributed to the perception that

women cannot give birth at BMDAMH anymore.

Figure 1: Births per financial year trend, Koorana unit.

The Koorana unit has struggled to recruit and retain midwifery staff in the years

leading up to commencement of the caseload model, owing to national shortages of

midwives and local birthing service interruptions. Nine out of nineteen midwifery

staff had resigned between 2008 and 2009, and ten more out of fifteen resigned in

2011[17]. This provided an impetus to change the way the BMDAMH utilised

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 Koorana unit -‐ Births per year

Ser

23

midwives to provide maternity care. Since the advent of the caseload midwifery

model in July 2011, recruitment into the caseload model has increased from four to

seven midwives over three years, and core staffing has remained stable. No

midwives have resigned since the commencement of caseload in July 2011.

The issue of where and how to birth in the Blue Mountains, has been represented

in the mainstream and social media[15]. Women’s voices opposing maternity service

interruptions have been captured in the mainstream press and television on several

occasions. Headlines such as; “Women in labor sent packing”[16] and “Blue

Mountains residents rally to save their maternity ward”[18] published in the Sydney

Morning Herald, are testimony to the strength and organizing abilities of the Blue

Mountains birthing community, in response to diminishing local birthing services.

Birthing numbers have not been restored to pre-2008 levels, and for this reason,

there is a need to engage with the local community once again to re-build trust, as

well as showcase the achievements of the caseload midwifery model of care at

BMDAMH.

Community forums were held in 2008, when women consistently voiced feeling like

they had ‘no choice’ when required to birth at Nepean hospital. Whilst appreciating

the role of Nepean hospital as a tertiary referral center, Mountains women wanted

to be assured they could birth closer to home when their pregnancy was low risk,

and they also wanted midwifery continuity of care by a known midwife. Next to

these issues, women wanted vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) and

water-birth to be offered at BMDAMH[7]. Midwifery continuity of care has now largely

been realized for women who birth at the BMDAMH, however water-births and

VBACs have remained on the community agenda, as evidenced by consumer

surveys returned and reported on in this evaluation.

24

DEFINING THE TERMS

Continuity of care Over the last 10 years researchers have attempted to achieve consensus on a

definition of continuity of care [19-22]. In the midwifery literature the concept of

continuity has been variously described [23-28]. Midwifery continuity of care is defined

as “continuity over time that allows the development of a relationship in which the

woman and midwives may get to know each other and form a contract of

commitment” [28]p.29 Providing continuity of care allows a woman to establish a

relationship of trust with a named midwife, or small group of midwives throughout

her pregnancy, labour, birth and postnatal period.

Midwifery continuity of care models have demonstrated significant improvement in

maternal Infant outcomes when compared to standard care and address women’s

specific needs, preferences and expectations [24, 29]. Outcomes include:

• Reduced length of labour

• Reduced need for pharmacological pain relief

• Reduced need for intervention in labour, including operative vaginal births

and caesarean sections

• Lower rate of admission of babies to Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU)

• Increased satisfaction for the mother

• Reduced rates of postnatal depression

• Improved rates of successful breastfeeding

• Improved rates of attendance at antenatal classes

Caseload Midwifery Caseload midwives provide care to a number of women per year, organize their

time flexibly around their woman’s care needs, and do not work rostered shifts [28].

In this model, one midwife assumes the role of ‘primary’ midwife, providing

antenatal, birth and postnatal care to caseload of women. As well as being ‘primary’

midwife for an agreed number of women each midwife is also the backup midwife

for women who have another midwife as their primary carer. The primary midwife is

25

the woman’s coordinator of care, facilitating her access to more complex care

(often obstetricians), according to her needs. Also referred to as “continuity of carer

model” or “one-to-one” midwifery care. Privately practicing midwives generally

provide care in this model. The model established in BMDAMH in 2011, is basically

a caseload model, except midwives work ‘shifts’ with a ‘team’ style shift

arrangement for on-call birthing care.

Team midwifery Team midwifery is care provided throughout pregnancy, birth and postnatally for a

set number of women by a small team of midwives. These midwives are usually

employed in a maternity or birth unit, and are rostered to work shifts. The team

approach, limits opportunities for continuity of carer and the ability to establish

relationships with women, because care is provided by a team rather than a

primary midwife. The emphasis in these models is on continuity of ‘care’ rather than

continuity of ‘carer’ [28].

Team midwifery improves management and informational continuity for women and

families, and puts less emphasis on the relational dimension of continuity (i.e.

between a primary midwife and the women). In effect, the whole team carries a

caseload collectively, with the opportunity for the women to meet all the midwives

antenatally to provide some measure of intra-partum continuity. Caseload midwives

at BMDAMH, use an element of the ‘team’ approach with respect to birthing care,

by using a roster system to cover on-call with some flexibility for primary midwives

to attend their own women in labour if they choose to.

Caseload The actual number of women a caseload midwife provides care to in a year (i.e. her

workload). This is usually set at 35-42 women a year, depending on risk, complexity

and full or part-time status of midwives working in the model. [30]. The caseload is

40 women per full-time equivalent (FTE) midwife at BMDAMH.

Midwifery Group Practice A Midwifery Group Practice (MGP) is the organizational or management unit in

which caseload midwives usually work [28]. The MGP is organized to maximize

26

continuity of carer for individual women, while supporting and sustaining midwives

in their work. Continuity is usually achieved by midwives working in groups of two or

three, and negotiating backup arrangements for each midwife’s women. This

maximizes the women’s access to a known midwife at her birth, because the ‘pool’

of possible caregivers is small (2-3 midwives).

In larger MGPs (>3), women’s access to continuity of carer, particularly for intra-

partum care can be compromised[31]. Broadly distributed backup arrangements

(e.g. the whole group providing backup, such as the BMDAMH model), will tend to

provide only a small proportion of women with care from their named midwife in

labour and birth, unless individual midwives choose to come in for their women

when not rostered to work. Figure 2 provides an overview of continuity of care

models as reported in the literature.

Core midwives Core midwives are based in hospitals, usually work rostered shifts and provide

clinical support to the primary midwife. Core midwives provide the majority of

clinical care to women who are admitted to hospital.

POLICY AND EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE MODEL In June 2010 the NSW Health Department introduced a policy directive for NSW

Maternity services; Towards Normal Birth [1]. The directive was partly a response to

the rising caesarean section rates that were published in The Mothers and Babies

report of 2006 [33], and a concern about the morbidity and mortality associated with

multiple caesarean sections in subsequent pregnancies (unexplained stillbirth,[34]

placenta accreta and percreta [35, 36], placental abruption, decreased fertility, ectopic

pregnancy, spontaneous abortion[37] and neonatal respiratory problems[38]).

The resultant 10-point action plan for normal birth, aims to decease the caesarean

section rate and increase the vaginal birth rate in NSW, as well as improving

women’s experience of birth, by ensuring access to continuity of midwifery care. The

Towards Normal Birth action plan runs parallel to the priorities and recommendations

contained in the National Maternity Services plan that recommends reforms

embracing improved access to models of care, collaboration and the expanded role

of the midwife[39].

The BMDAMH Caseload midwifery model fulfills steps three, four and nine of the

Towards normal Birth policy directive [1]. Namely; ‘To provide or facilitate access to

midwifery continuity of carer programs’ (step 3), ‘inform all pregnant women about

the benefits of normal birth and factors that promote normal birth’ (step 4), and

‘Provide one to one care to all women’ (step 9).

Midwife-led care has been consistently associated with higher rates of spontaneous

vaginal birth [24, 40, 41], and a reduction in caesarean section operation rates [42].

Furthermore, high-level evidence from randomized controlled trials indicate that

caseload midwifery is an ‘intervention’ that reduces obstetric intervention, (including

episiotomy and epidural analgesia rates) increases breastfeeding rates, and

provides high levels of satisfaction for women, with no measured detriment to

mothers or babies [43, 44]. In line with published evidence, it is anticipated that a

change to caseload midwifery model at the BMDAMH, has enhanced the quality of

maternity care in the region, without compromising the safety of women and babies.

29

DESCRIPTION OF THE MODEL OF CARE

Establishment There is a long history of consumer support for caseload midwifery care and birthing

in the Blue Mountains region. Plans were drafted in 2003 and 2008 for a caseload

model at BMDAMH that did not eventuate [2]. However, the current model did

commence at BMDAMH in July 2011, shortly after a similar model was established

at Nepean Hospital. The commencement directive came from the Local Area Health

Service in early 2011, and a caseload midwife from the Nepean program was

seconded to BMDAMH to support and mentor new caseload midwives in the

Koorana unit. The model was rolled-out in much the same way as the Nepean

model, with midwives being assigned a caseload of women each, but sharing on-call

birthing among the group. The new model that was established at Koorana did not

resemble earlier models proposed, with respect to the working configuration and on-

call arrangements of midwives (presumably because of the small number of

midwives recruited at commencement would have made it difficult to work in smaller

groups of twos or threes).

Annualized salary agreement Caseload midwives at BMDAMH are employed under an industrial agreement with

the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District, ratified by the NSW Nurses and

Midwives’ Association, and based on the Model NSW Department of Health MGP

annualized salary agreement[45], the agreement allows for flexible working

arrangements and self-management of midwives workload, deciding their own

working patterns and negotiating their own leave. This type of arrangement

empowers caseload midwives to be attentive to the needs of the women in their

care, rather than to the dictates of traditional shiftwork. Caseload midwives receive a

base salary in accordance with their year of service or clinical award, with a 29%

loading that replaces shift loadings and on-call allowances. Caseload midwives self-

roster, having nine days off a month (FTE), and are entitled to six weeks annual

leave per year. The agreement stipulates that midwives not work longer than 12

hours at a time, handing over care (usually of a woman in labour) to their caseload

30

colleague after the 12 hours has expired.

Table 1: Koorana Caseload midwife Profile July 2011 – June 2014

Date Team structure July-11 Recruitment 3 x fulltime midwives start + Aug-11 Working as one group of four 1 x fulltime midwife Nepean Sept-11 seconded as a mentor Oct-11 1 midwife leaves for 6 months Nov-11 1more fulltime midwife starts & Dec-11 Nepean mentor midwife Jan-12 leaves & is replaced Feb-12 Mar-12 1 X 0.7 FTE midwife starts Apr-12 Working a one group of five & Nepean midwife leaves May-12 1 fulltime midwife comes back

from 6 months leave June-12 (Caseload midwives care for 62.3% of all July-12 women who book into BMDAMH) Aug-12 Sept-12 Oct-12 Nov-12 Dec-12 Jan-13 Feb-13 Mar-13 Apr-13 May-13 June-13 Working as group of six 1x fulltime midwife starts July-13 Working as group of seven 1 x 0.5 FTE midwife starts Aug-13 (Caseload service care for 72.7% of all FULLY STAFFED Sept-13 women who book into BMDAMH) Oct-13 Nov-13 Dec-13 Jan-14 Working as group of six 1 x fulltime midwife Feb-14 Transferred to Nepean & 0.5 FTE

becomes 0.8 FTE Mar-14 (understaffed again) Apr-14 May-14 (Caseload midwives care for 95.6% of all June-14 women who book into BMDAMH)

31

The model Staffing for the model was taken from the existing complement of 12.53 full time

equivalent (FTE) midwives on the maternity ward. Six FTE caseload positions were

taken from the ward complement, and 6.53 FTE positions remained as ‘core staff’.

Each FTE midwife takes up to 40 women per year in her caseload (four women

booked per month, per midwife). The caseload practice started with a complement of

four midwives (one from Nepean), and only reached full capacity (6x FTE = 7x

midwives) in July 2013. For the duration of the model, the midwives have worked as

a whole group (of four, five, six and seven depending on stages of staffing capacity),

rather than in pairs, or groups of three (see table 1), and relieve each other for

annual holidays. (i.e. there is no holiday relief midwife position built into the model).

Midwives plan their holidays in advance and do not book women into their caseload

who are likely to birth whilst on leave.

Despite the annualized salary arrangement and associated assumptions for flexible

work arrangements, caseload midwives essentially work to a roster system at the

Koorana unit. Roster codes describe several types of shifts (J, K, M6 and M5) and

the duties expected of these shifts. Shift types were developed by management to

enable working hours to be entered into the ProAct hospital roster database.

Caseload shifts at the Koorana unit are described below:

1. J: 7am – 7pm on-call caseload midwife, who is called to care for women in

labour during these hours

2. K: 7pm-7am on-call midwife who cares for women in labour overnight, even if

these women are not allocated to caseload.

3. M6: 2nd on-call midwife during the day, however no specified start and finish

time. Midwife can schedule ante or postnatal visits on these days.

4. M5: Midwife works to own schedule, or can have this day off is she is has

worked too many hours. M5 days are only included in the roster when there is

close to a full complement of staff.

32

The shift system used in the model thus far, aims to give each caseload midwife time

to attend antenatal appointments for the women in her caseload, as well as visit

postnatal mothers and babies at home or on the ward. Intra-partum care is provided

in a rotating, on-call system where one caseload midwife in the group is on-call for

all birthing women in the practice after hours (shifts J and K). Thus each midwife

does a proportion of on-call shifts each month, where she only attends work if a

women presents in labour.

All caseload midwives divert their phone to the on-call midwife after hours, who is

the first port-of-call for all women’s phone calls to the practice, and cares for all

women in labour. A commonly occurring exception to this, is when the primary

midwife makes a arrangement with the on-call midwife ahead of time, that she will

come in and care for her women in labour should women present after hours, or

whilst the primary midwife is on a day-off. Provision for primary midwives to attend

their own women in labour when not rostered to work is built into the draft rules of

the model [46]. In effect, this means that a woman allocated to a primary midwife has

a one in six chance (or one in four, five or seven, depending on number of midwives

in the practice at the time) of having her primary midwife care for her at birth if all

midwives adhere to the roster. However, often the woman’s named midwife does

attends her birth on a day off, or when not rostered to be on-call, which improves the

chances for the woman, of her primary midwife attending her birth.

Despite the larger ‘pool’ of women for the on-call caseload midwife to potentially care

for in labour each shift, caseload midwives at Koorana on average still manage to be

present for over half of their own women’s births*, with an array of 44%† of their

women’s births, if midwives working in accordance with the roster, to up to 81% of

their women’s births, when midwives regularly attend women in labour outside of

roster hours. This is evidence that caseload midwives are flexible to varying extents,

and that frequent communication has boosted birth continuity outcomes within the

constraints of the rostering system that is in place.

The woman is given her primary midwives mobile phone number, and on-call

* Average Continuity at birth rate for all caseload midwives at BMDAMH between the period of July 2013 - June 2014. † Corrected, to exclude women who birthed at Nepean hospital, for the period July 2013 – June 2014.

33

arrangements are explained to all women on booking in to the service. Women have

the opportunity to meet the other caseload midwives (who they might otherwise meet

in labour) at monthly meet-and-greet sessions organized and hosted by Koorana

caseload midwives.*The purpose of meet-and-greet sessions is for women to meet

all of the caseload midwives, and make connections with other women.

Staffing and Support Management

The Nurse/Midwifery Unit Manager (NUM) of the combined Maternity and Children’s

ward (Women and Children’s Health) is responsible for leadership, management and

facilitation of communication relating to the Koorana caseload practice, and

processing of time sheets.

Administration

The ward clerk on the Maternity ward provides some administration support to the

caseload service by providing women with booking and administration forms to

complete. The ward clerk processes the completed paperwork that enables caseload

midwives to allocate women to a primary midwife.

Core midwives

Core midwives make up about half of the midwifery staffing component of the

maternity unit, and are employed on a rotating roster. They provide back up to the

caseload midwives after hours for intra-partum care, and care for the small

proportion of women (5%) who are not booked under caseload care (e.g. doctors

clinic or Nepean caesarean sections). Core-staff provide 24-hour care to all women

and babies who stay in hospital following the birth. Three core midwives are needed

to staff the unit in a 24-hour period (one per shift). Caseload midwives were often

called in to fill core staff roster gaps or sick leave in the preceding three years of the

evaluation.

Obstetric staff

Three part-time, specialist obstetricians and one part-time registrar provide the bulk

34

of obstetric support to the caseload model. All women wanting to book into the

caseload model of care, will be reviewed (or have her notes reviewed) by obstetric

staff at the Koorana unit soon after their initial booking visit. Collaboration occurs

between the caseload midwife and obstetric staff in the event of risks or

complications in any stage of the pregnancy, in accordance with the National

Midwifery Guidelines for Consultation and Referral [6] or at the wishes of the woman.

The woman consults again with the obstetrician at 40 weeks gestation to initiate a

post-dates induction of labour plan.

Specialist obstetricians, (and locums on occasions), provide 24-hour, on-call

obstetric support to caseload midwives who are the lead providers of intra-partum

care, as well as conducting elective Caesarean section theatre lists. The proportion

of women receiving obstetric-led care has diminished from 50% (2011) to less than

3% (2014) as a result of the introduction of the caseload model at BMDAMH (fig. 5).

This has considerably reduced the workload of specialists, and redirected their

efforts to clinically appropriate obstetric cases, and enhanced gynecological services

at BMDAMH.

Birthing services at BMDAMH were regularly suspended in 2008 and 2009 due to a

lack of either; obstetric, anesthetic and paediatric cover at BMDAMH. When there

are no specialists available to fill the roster, women in labour are re-directed to

Nepean hospital, 50 minutes drive away. It is likely that the unfolding of the caseload

model, as well as the appointment of a part-time obstetric registrar at BMDAMH has

contributed in a positive way to the retention of specialist obstetric staff in the unit,

resulting in a drastic reduction of maternity unit closures since the model

commenced.

Cars

Caseload midwives use their own private vehicles for visiting women and babies in

their homes, and claim these expenses back on personal tax. All midwives vehicles

carry baby scales, dopplers, and other equipment necessary to perform antenatal

and postnatal visits in women’s home.

Phones

Each caseload midwife is provided with a mobile phone to be used in accordance

35

with NDMLHD policy, and paid for by the health service. All midwives divert their

incoming calls on their phone to the midwife who is on-call from 7pm – 7am (K shift)

each night, and the day on-call midwife, (J shift), between the hours of 7am – 7pm.

When midwives are running clinics or doing home visits during the day, they may

also un-divert their phone to enable communication with women who have

appointments or need advice. Women, and other midwives communicate by ‘texting’

each other about appointments, or women in labour. A text message will register on

primary midwife’s phone, whereas a phone call will often be diverted to another

caseload midwife. In this way, the primary midwife can choose to check her work

phone messages and respond to text messages that women or colleagues leave on

her days off.

IT systems

Caseload midwives are required to enter all their antenatal appointments in the iPM

system as an occasion of service, as well as ObstetriX, an obstetric information

database for each client, based on the clinical perinatal dataset. Ward computer

terminals are used for data entry, as well as two laptops (whilst connected to hospital

Wi-Fi).

Clinical governance

Caseload midwives adhere to the National Guidelines for consultation and referral[6,

47].The guidelines ensure the appropriate referral and consultation pathways are

negotiated with the obstetric staff in the Koorana unit, and women significant risk

factors have their care transferred to Nepean hospital according to The Blue

Mountains Hospital Obstetric Criteria, last revised in 2009 (see appendix 2).

Midwives professional conduct and practice is guided by the Australian Nursing and

Midwifery Council’s National Competency Standards for the Midwife (ANMC 2008).

Critical incidents are reported using the Incident Information Management System

(IIMS) reporting framework [48].

Monthly maternity morbidity and mortality meetings (M&M meetings) are held

between all midwives on the unit, management and obstetric staff. These meetings

are an audit and quality assurance exercise, as well as an opportunity for the

professional development for all staff involved. It is recommended that caseload

36

midwives also keep individual monthly statistics of their activity and birth outcomes,

and submit these periodically to management. However this has largely not occurred

for various reasons, including the huge volume of other essential electronic and

paper-based documentation/reporting that is required of caseload midwives.

Physical workspaces The caseload practice operates out of the Koorana unit at BMDAMH. A beautiful unit

consisting of two birth suites, eight single maternity rooms, and one neonatal bed in

a level two nursery. A reception desk seats a ward clerk who greets women, families

and visitors on their way into both the maternity unit and Children’s ward. Directly

behind this, is an open ‘midwives work station’ with a computer. Outside the two

birthing suite rooms, there is a similar workspace, used by all clinicians in the

maternity unit.

The ‘caseload office’ serves the whole group of seven midwives and is a 2.4 x 3

meter space with a desk, computer and cabinets housing postnatal files, and

caseload documentation. The office serves as storage for all personal and

professional resources that are used by caseload midwives. Another small

consulting room provides the space for all antenatal consultations conducted by

midwives and obstetricians on the unit. During office hours the clinician demand for

this room is high, due to privacy and computer access, it enables contemporaneous

documentation in women’s electronic antenatal record whilst the consultation is in

progress. The problem with this however, is there is rarely only one caseload

midwife or doctor consulting with women at any one time. Caseload midwives keep

their own separate appointments diaries, often resulting in several caseload

midwives plus core staff in the workspaces at the same time, waiting for women to

arrive or for clinic space to become available.

The frustration of this scenario has been partly relieved with the introduction of two

laptops for the caseload service, which makes it possible for caseload midwives to

use an unoccupied maternity room with the laptop to complete an antenatal visit.

However, a lack additional laptops and remote access prevents midwives being able

to use a laptop outside the hospital environment. Caseload midwives could

37

potentially do antenatal visits in the woman’s own home, or a community venue such

as; Woman’s Health Centre, Aboriginal Resource Centre or a Youth center as

appropriate for each women.

Midwives at BMDAMH have historically conducted weekly antenatal clinics at the

Women’s Health and Resource center in nearby Katoomba. These community

clinics were well attended, and valued highly by women in the Blue Mountains area [7], and enjoyed by the midwives who conducted them. Such arrangements foster

linkages with community organisations, and provide women with convenient and

culturally safe places to access other than the hospital. For women with small

children, and limited transportation, antenatal visits in the home can reduce ‘no

shows’ and be a positive experience for the woman and the midwife. Midwives

currently have the equipment and transportation to conduct antenatal visits outside

the maternity unit, but lack remote computer access for laptops to connect with the

clinical databases required, which has proved to be a significant barrier to exploring

these options.

Women’s care journey Women usually attend their GP for pregnancy confirmation, antenatal screening

pathology and early ultrasounds. She is then advised to phone the maternity ward to

request a one page ‘booking in form’ that the W&CH ward clerk can mail or give to

her in person. The ‘booking in form’ is mailed or dropped back to the maternity unit

once the woman has completed it, along with a copy of any antenatal test results the

GP has initiated.

The women should receive a call from her newly appointed caseload midwife within

two weeks of sending in the form (after the midwife has reviewed her medical history

and any other requirements she has made explicit in the booking in form and GP

correspondence), this phone call is usually the woman’s first contact with her

caseload midwife, when they arrange a suitable time for a booking history visit at the

hospital. At this initial visit, a yellow pregnancy card is initiated (if not already by the

GP), and pregnancy record commenced on the ObstetriX electronic database. The

woman is introduced to the service, the philosophy of the model, and given her

38

primary caseload midwife’s phone number and guidelines for contacting her midwife.

The woman and her partner are also encouraged, and enrolled in parenting classes

conducted on the hospital grounds if they are interested in this. During the booking

visit, the woman is given a pamphlet pack pertaining to her pregnancy, and an

appointment is made for her to see the obstetric staff if there are medical or obstetric

concerns of consequence to the woman or midwife in the booking visit. The woman

in most cases attends the same venue to see an obstetrician. At this appointment

she can pursue specialist or allied health referrals as appropriate (e.g.

physiotherapy, psychology, psychiatry, medical, anesthetics), and be ‘cleared’ to

receive her care under the caseload midwifery model.

As Koorana is a low-risk, level three maternity unit, all women who meet the criteria

(appendix 2) for birthing at Koorana, are eligible to be cared for in the caseload

midwifery model. Even if the women should need to see an obstetrician periodically

throughout her pregnancy, the relationship with her caseload midwife is retained

throughout her pregnancy, birth and postnatal period. If a women's recommended

pregnancy care lies outside the Blue Mountains Obstetric guidelines (e.g. Vaginal

birth after caesarean section, VBAC), the woman is advised to also book in to

Nepean hospital for birth.

An average of seven (depending on gestation at booking) mutually convenient

antenatal appointments are arranged between the primary midwife and the women

to attend at the hospital in accordance with the antenatal visit schedule. The primary

midwife calls, or texts the woman if an appointment needs to be rescheduled due to

the midwife attending another woman in labour. The woman occasionally may see

another caseload midwife for an antenatal visit when her primary midwife is away on

annual leave. The primary midwife will arrange, and follow up any pathology or

ultrasounds and communicate results to the woman. The primary midwife also

liaises with obstetricians, allied health, and community agencies in consultation with

the woman if required. The woman is invited by her primary midwife to attend a

meet-and-greet evening sometime in her third trimester. Meet-and-greet sessions

allow the woman to make contact with the other five or six midwives in the caseload

practice in a friendly informal environment.

39

The woman will be transferred to Nepean hospital by ambulance if she presents to

the Koorana unit with threatened premature labour at less than 36 weeks gestation,

or if another significant risk factor emerges such as pre-eclampsia. If the woman

requires additional ultrasounds in her pregnancy, she can attend a private ultrasound

service in Katoomba, or the Feto-Maternal Assessment Unit (FMAU) facility at

Nepean hospital. The woman will also be advised to present at the FMAU - post-

dates clinic if she is still pregnant at 41 weeks gestation.

The women calls her primary midwife in the event of her labour starting, waters

breaking, vaginal bleeding, or reduced fetal movements (or any other concern). In

most cases she will encounter the caseload midwife on call on the other end of the

phone (unless her primary midwife’s phone is un-diverted), who will advise the