Camera activism in contemporary People's Republic of China: provocative documentation, first person...

Transcript of Camera activism in contemporary People's Republic of China: provocative documentation, first person...

This article was downloaded by: [192.184.34.186]On: 26 February 2015, At: 20:11Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Click for updates

Studies in Documentary FilmPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsdf20

Camera activism in contemporaryPeople's Republic of China: provocativedocumentation, first personconfrontation, and collective force inAi Weiwei's Lao Ma Ti HuaTianqi Yua

a School of International Communications, University ofNottingham Ningbo ChinaPublished online: 12 Feb 2015.

To cite this article: Tianqi Yu (2015): Camera activism in contemporary People's Republic of China:provocative documentation, first person confrontation, and collective force in Ai Weiwei's Lao Ma TiHua, Studies in Documentary Film, DOI: 10.1080/17503280.2014.1002251

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2014.1002251

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

Camera activism in contemporary People’s Republic of China:provocative documentation, first person confrontation, and collectiveforce in Ai Weiwei’s Lao Ma Ti Hua

Tianqi Yu*

School of International Communications, University of Nottingham Ningbo China

Ai Weiwei’s film Lao Ma Ti Hua (aka Disturbing the Peace, 2009) is one of themost influential activist documentaries that emerged during the aftermath ofSichuan earthquake in 2009. The film relates to Ai’s ‘Public Citizen Investiga-tion Project’, which gathers many volunteers to explore the substandard ‘tofuconstruction’ of school buildings that took thousands of children’s lives whenthey collapsed in the earthquake. In August 2009, Ai’s group went to Chengducourt to support another independent investigator, writer, and environmentalistTan Zuoren who was prosecuted for subversion of state power. The night beforethe trial, Ai was beaten by secret security agents and the group was stoppedfrom going to the court. The film subsequently records the group searching foran official explanation from the authorities. Whilst acknowledging the power ofthe film in constructing a collective political subjectivity, and the discursiveeffect through screenings and discussions raised, this paper focuses on the veryaction of proactive, activist documentation of one’s witness to engage withfellow participants as well as viewer followers through digital camera. Under thetheoretical framework of participatory culture, I propose the term cameraactivism to understand the camera-enabled individual participation into activismas a form of socio-political intervention. The paper also analyses some of Ai’sproblematic actions as a charismatic celebrity, which sometimes overshadowand obscure the complexity of resistance by Chinese individuals within China,thereby neglecting full recognition of the complex collective forces whichsupport Ai. Nevertheless, ‘camera activism’ demonstrated in the making ofLao Ma Ti Hua reflects, and has the potential to reshape, the political landscapein twenty-first century China. The cinematic highlight of ‘I’, confronting andeye-witnessing what happens through the utilization of digital technologiespositions ‘camera activism’ as an important part of China’s iGeneration cinemaculture.

Introduction

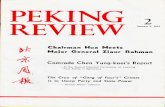

This self-portrait (Figure 1) of Ai Weiwei, the most politically outspoken contem-porary Chinese artist, was taken during an arrest on 12 August 2009, in the period ofhis investigation, with many volunteers, into substandard ‘tofu construction’ ofschool buildings during the aftermath of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Ai and hisvolunteers traveled to Sichuan to testify in the defense of Tan Zuoren, a Sichuan-based writer, and environmentalist who had also been independently investigatingthe school building scandal, but had been prosecuted for subversion of the state

*Email: [email protected]

Studies in Documentary Film, 2015http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2014.1002251

© 2015 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

power. The night before the trial, the local police forced their way into the hotelroom where Ai’s group was staying, hit Ai on his head, and arrested one of thevolunteers. This is the moment when Ai was accompanied by the police into a liftafter being beaten. Ai raised his left hand holding a mobile phone above his head.The flash of the phone camera sparkles, documenting this moment as visualevidence, as if he were using a gun to fight back the state authority. Immediatelyafter the incident, this image together with a sound recording were posted onto socialnetworks, and then reposted by thousands of international viewers, creating a strongsense of immediacy and urgency.

Together with the self-portrait and the sound record, Ai’s volunteer Zhaozhaoalso recorded the whole journey with a digital video (DV) camera. The footage wassoon edited into a documentary entitled Lao Ma Ti Hua (aka Disturbing the Peace),which literally means a local sichuan dish of boiled trotters, to avoid politicaldetection when it was circulated onto domestic video sharing sites and online forums.The film, documenting the journey of Ai and his group visiting local legalinstitutions asking for a justification for the brutal illegal treatment, becomes amonumental activist documentary, portraying detection an exceptional case in thehistory of Chinese independent documentary in a highly influential way. As a pieceof visual evidence, it constructs face-to-face first person confrontations between agroup of rights-conscious individuals and the state authority. The direct challenge tothe authority and explicit advocacy for social change create a collective identityamong the participants and the audience. The social media circulation of the filmacts as a continuation of the activism, for the potential effect in mobilizing awareness

Figure 1. Ai takes a picture of himself surrounded by policemen by a mobile phone.

2 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

among viewer followers, and fellow filmmakers/artists for further actions, theinternational communities, and even the decision makers.

Whilst acknowledging the power of the film’s text and the discursive effectthrough its screening, this paper, however, focuses on the very action of proactive,activist documentation of one’s witness and first person confrontation with anopposition, to engage with fellow participants as well as viewer followers throughdigital camera. Under the theoretical framework of participatory culture, I proposethe term camera activism to understand the camera-enabled individual participationinto activism as a form of socio-political intervention. This paper first introduces AiWeiwei’s public-engaged activist art practices and political activism in China inrecent decades, including online activism, and independent filmmaking as a form ofsocial engagement. Then it reviews current scholarly studies of activist documentaryand explains the configuration of ‘camera activism’ that highlights the action ofprovocative documentation, first person confrontation, and collective effort. Afterthe theoretical consideration, the paper analyses how the making of Lao Ma Ti Huabecomes ‘camera activism’. Lastly, the paper also points out some of Ai’sproblematic actions as a charismatic celebrity, which sometimes hinder acceptanceby Chinese individuals, and overshadow and obscure the complexity of resistance byindividuals within China, thereby neglecting full recognition of the complexcollective forces which support Ai. Overall, the cinematic highlight of ‘I’, eye-witnessing and challenging what happens through the utilization of digital techno-logies, as demonstrated in Lao Ma Ti Hua, positions ‘camera activism’ as animportant part of China’s iGeneration cinema culture that increasingly emphasizesindividual self-expression, and digital technology, under the global experience ofindividualization.

Political activism in twenty-first century China

As well as an artist, cultural critic, architect, curator, Ai Weiwei is mostly recognizedinternationally as a political activist and celebrity dissident. Political activism hasbecome a key theme in his art practice, and has gained much public awareness,especially since his ‘Public Citizen Investigation Project’ in 2008. The project, whichinvolved many of Ai’s followers and volunteers, has been developed into severalpublic-engaged art works. These explore and expose the cause–effect relationshipbetween ‘tofu construction’ – the low-quality, fragile school buildings which werenot built to code because of local official’s corruption, and the death of large numberof schoolchildren in the devastating high magnitude earthquakes in Wenchuan,Sichuan province. Examples include a visually astonishing installation called‘Straight’ shown at 2013 Venice Art Biennale, a collation of 150 tons of steelsupport beams that Ai and his group have collected from the collapsed school sites,after being painstakingly re-straightened. The work has been shown together with aninstallation of a wall of names of the dead children with an audio accompanimentspeaking such names through the voices of anonymous individuals who participatevoluntarily.

In many of Ai’s political activist art works, he encourages his participants to useDV cameras as a weapon to document their investigations, and the most well-knownone is Lao Ma Ti Hua, which is the focus of this paper. Such political artisticengagements are aligned with increasing activist movements in the People’s Republic

Studies in Documentary Film 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

of China (PRC) in recent decades. In what Yan Yunxiang regards as the state-enforced de-collectivization process in post-socialist China, the state’s retreat frompublic life also means that individuals have gained more freedom (Yan 2009, 2010).Along with the desire for personal happiness is the growing concern for individualrights, not just for political rights, equal opportunities, and the recognition ofmarginalized identities, but also the rights to enjoy a better environment and saferfood. Such activist movements, as an important part of the global history of fightingagainst oppression and for the realization of individual subjectivities, were firstevident on the Internet in China since the late 1990s (Damm and Thomas 2006;Lagerkvist 2006; Yang 2009). The US-based sociologist Yang Guobin regards it as‘online activism’, a direct reflection of the new citizen activism and ‘a response to thegrievances, injustices, and anxieties caused by the structural transformation ofChinese society’ (2009, 7). Such activism is visible in the constant environmentalprotests, migrant worker protests, anti-official corruption, and fight for freedom ofspeech on Chinese social media such as Weibo, literally meaning ‘mini blog’.Individual self-expressions have formed streams of political activism in the PRC,which continue to push boundaries. For example, in January 2013, when journalistsof Southern Weekly, representing the most outspoken Chinese newspaper, openlyrefused to participate in the censorship order enacted by the provincial propagandabureau, individuals from all over the country showed enormous support throughstreet demonstrations as well as social media. Wang Hui, an influential Chineseintellectual, regards China as being in an era of depoliticized politics in the last fourdecades, a time that is lacking in ‘political debates, political struggle, and socialactivism around specific political values and their attendant benefits’ (2006, 690–691). While it might be the case on the macro-level, I argue that, there has beenincreasing micro-political activism in the PRC. More activist movements havemoved beyond the Internet, with the support and assistance of digital technologies,including the growing number of politically engaged and activist-related independentdocumentary practice discussed later.

First emerging in the early 1990s and proliferating in the new century, Chineseindependent documentaries have largely raised the unheard voice of the socially andgeographically marginalized individuals and groups. By representing a reality that isin opposition to or alternative to the state-controlled media production, independentdocumentaries have shifted the power of representation from ‘authorized’ profes-sionals to amateur individuals (Jaffee 2006, 102). Many of these films that attractmuch scholarly attention (Lu 2003; Wang 2005; Berry and Rofel 2010; Robinson2013; Johnson et al. 2014) construct cinematic representation of contemporary socialconditions in China through the Vérite observational style. For example, the artist,filmmaker Zhao Liang’s documentary Petition (2009) is a long-term documentationof a large group of marginalized petitioners/activists, who for many years traveledfrom rural areas to gather in the suburbs of the capital Beijing to appeal their cases.While the petitioners fight for legal justice, the filmmaker Zhao has also aligned hisindependent intentions to encourage free artistic expression with that of hischaracters, searching for legal treatment and human rights. Compared to the mostvérite style independent Chinese documentaries, Ai’s documentaries have moredirect political engagement and belong to, what Qian Ying observes, a small groupof activist documentary cinema that explicitly urges for social change(2014, 182). Inaddition to Lao Ma Ti Hua, Ai’s studio also produced Yang Jia - Yige Gupi de Ren

4 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

(A Lonely Person, 2010), investigating the cause and effect of an incident in which ayoung citizen Yang Jia broke into a local police station in Shanghai and killed agroup of policemen. Filmmakers of activist documentaries also include Hu Jie, andAi Xiaoming who have been subversively conducting investigations into socialinjustice and human rights abuses (Zhang 2012). While Hu Jie investigates andexposes repressed historical issues or moments, such as in his films Searching for LinZhao’s Soul (aka Xunzhao Lin Zhao de Linghun 2004), Though I am gone (aka WoSui Si Qu 2006), Ai Xiaoming focuses more on contemporary social issues, such aswomen’s rights and inequality in her documentary The Vagina Monologue: BackstageStores (aka Yindao Dubai 2004); village elections, land ownership, and village levelanti-corruption in Tai Shi Village (aka Tai Shi Cui 2006). They have also been doingactivism through camera and documentary intensively, such as their collaborativefilm Our Children (aka Women de wawa, Ai Xiaoming, and Hu Jie 2009).

In comparison with the growing amount of scholarly attention to Chineseindependent cinema, activist documentary practice in the PRC has been relativelyneglected. Nevertheless, in the context of increasingly individualizing, and techno-logically mutable contemporary Chinese society, activist documentary practice,especially ‘camera activism’ discussed in the next section, is as an indispensable partof China’s iGeneration cinema that foregrounds individual amateur participation,technologically enabled filmmaking, and new forms of online distribution to engagegrassroots audiences (Jonson et al. 2014).

Camera activism as a form of critical social engagement

In the international field of documentary studies and cultural studies, recent worksby Angela J. Aguayo, D. Whiteman, Christian Christensen amongst others providesignificant insights into the impact of activist documentary. Aguayo focuses on thefinished production as a political object and points out the constitutive nature ofactivist documentary, and its potential to generate a sense of shared subjectivitiesamong the viewers. ‘The activist genre has the potential to create a spectator,deliberative, consumer or viewer-citizen identity that has varying ramifications forthe process of social change’ (Aguayo 2005, 6). In the case of Lao Ma Ti Hua, Iagree that the film has the potential to create ‘collective audience identity’ (Aguayo2005) during the viewing process. However, the number of viewers is still verylimited, and it still remains difficult to follow the audiences’ identification process, soto measure the effectiveness of how such activist documentaries are received.

The film was made shortly after the beating incident and was first posted ontointernational social media such as Twitter and Facebook. Ai’s incident as well as theXinjiang Riot incident on 5 July 2009 have raised intense online debates in andoutside China during that period, which ultimately resulted in the ban of Twitter andFacebook in China since August 2009. Meanwhile, the film was also circulatedthrough Chinese video sharing sites, such as tudou.com and online forums under thejovial non-sequitur Lao Ma Ti Hua, which as explained previously, is the name of alocal Sichuan dish, and also the name of the restaurant where the group gathered theevening before the incident. Again it was soon discovered by Chinese ‘Internetpolice’, and was subsequently blocked for users inside China. Ai Weiwei’s studio hasproduced a large number of DVDs1 which were circulated freely but mainly to sub-communities when requested. Given the enormous population of China, the number

Studies in Documentary Film 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

of viewers who have accessed the film was still very limited. Only focusing on thefilm text would neglect the fact that official banning of Ai’s work in China maycreate more desire for seeing the film. For Ai’s group, the dissemination of the filmitself could also be seen as a crucial part of their activism.

In contrast to Aguayo, D. Whiteman takes a step further and looks at the largerpolitical context of the production, distribution, and exhibition of activist docu-mentary and the extended social movements that relate. Whiteman argues that onlyfocusing on the finished film text offers ‘a very limited understanding of the complexand multifaceted ways in which film enters the political process’ (2004, 54).Alternatively, he proposes a ‘coalition model’, which is to:

evaluate a film’s potential effects on its producers and other participants involved inproduction, on activist groups that might contribute to or use the film, and on decisionmakers and other elites that might hear about the film. A political documentary has amore extensive range of effects beyond changes in individual understanding or attitude.(Whiteman 2004)

For Whiteman, ‘coalition’ refers to a mutually beneficial ‘feedback loop’ betweenfilmmakers, film subjects, grassroots screeners, audiences, and political activists. Thisloop creates a coalition of organizations and individuals who use the documentary asa point of connection. In the case of Lao Ma TI Hua, as well as the impact on theviewers which is difficult to quantify, the film has become a point of connection thatlinks the participants together. It should also not underestimate Ai’s elite identity asa globally well-known artist, and political advocator in attracting volunteers toparticipate in his activist network. These individuals, collectively, made this filmpossible. Concurrently, the international wide circulation of the film through socialmedia has also influenced fellow independent filmmakers, cultural elites in China, aswell as decision makers, even though the official recognition to the impact wasthrough a ban on Ai Weiwei and his subsequent home arrest since 2011. As a leadingChinese independent filmmaker, Wu Wenguang shows great respect for Ai’s filmingpractice, regarding it as a ‘complete action’ (Author’s interview with Wu Wenguang,July 2010), a medium to create social contact and civic engagement.

The ‘coalition mode’ provides great insight into understanding the discursiveimpact of Lao Ma Ti Hua from different stages of the film, and through varyingperspectives. However, it is not the aim of this paper to overemphasize the politicalnature in the context of production and circulation. By looking at the beneficial‘feedback loop’, Ai himself might be the biggest benefiter of his own activist publicengagement. The international recognition of this film, together with Ai’s previouspublic art work, has further enhanced Ai’s position in the art world and as almostthe only critical voice on contemporary Chinese society from within China,recognized by the West.

Instead of just focusing on the political value of the film text and the discursiveimpact filtering through to different viewers, it is essential to focus on the actualaction of provocative documentation as a political gesture of critical socialengagement. This is especially crucial to an understanding of such activist filmsmade outside Western democratic political systems, particularly, in an authoritarianor politically repressed state, such as the PRC. Therefore, I proposed the term‘camera activism’ to understand the participation into activism through digital

6 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

camera, such as the making of Lao Ma Ti Hua. It is important to note that the filmis made through collective effort of all the participants. Digital technologies havelowered the barrier for the like-minded anonymous individuals to take part in Ai’spolitical art projects. Gathering around Ai, the group shares comments on,contributes to, and creates media and artistic content for a wider audience.

Such a phenomena taking place in contemporary PRC in the twenty-first centurymirrors what Henry Jenkin coins ‘participatory culture’ (2006). Developed originallyfrom Jenkin’s research on fandom communities, ‘participatory culture‘ has beenapplied widely in the discussion of digital literacy and grassroots media creation. Itemphasizes the human participation rather than interactive media as technologicaladvance (Jenkins 2006, 137). The key features of this concept include low barriers toartistic expression and civic engagement, strong social connections among membersto create and share one’s creation; informal mentoring, and a belief in collectiveeffort (ibid). Though initially Jenkin discusses ‘participatory culture’ in contrast withmass commercial culture and corporate media in the national context of America, itseems relevant to understand the grassroots, or ‘minjian’ cultural politicalparticipation, in contrast to the official and commercial media production in thecontemporary PRC. By paying attention to who is making the documentary andwho is speaking, we notice that the once consumers or receivers also become activeproducers and delivers of their own creations and agenda. Therefore, this paperproposes the term ‘camera activism’ to understand the participation into activismthrough digital camera, such as the making of Lao Ma Ti Hua. ‘Camera activism’also responses to the recent rise of the ‘citizen journalism’ in the field of news media,which defined by Allan and Thorsen, as ‘the spontaneous actions of ordinary people,caught up in extraordinary events, who felt compelled to adopt the role of a newsreporter’ (2009).

‘Camera activism’ pays attention to the camera-empowered individual parti-cipation into activism as a form of socio-political engagement. It highlightsindividuals’ utilization of digital cameras like a shield to document one’s witnessas evidence for self-protection, and like a gun to directly confront the opposition,and engage with fellow activists as well as potential viewer-followers. The action ofconfrontational filming by the participants, most of whom are amateur filmmakers,demonstrates the very act of engaging and enraging, also generating affective andcritical expression among the viewers, potential followers. In Our Children (2009),multiple witnesses, parents who lost their children in the 2008 Sichuan earthquaketook amateur footage with their mobile phones and other digital cameras todocument the collapses of school building as visual testimony. In Meishi Street(2006), the director Ou Ning handed the DV camera to his protagonist Zhang, alocal resident in Da Zhanlan, Beijing, which was facing the state-forced demolition.Zhang used the camera to protect his rights and to confront the local officials,fighting for his personal familial space.

In such a provocative, confrontational documenting act, ‘camera activism’demonstrates subjective, first person perspectives. It is the moment of ‘I’ beingthere, eye-witnessing what is happening, often together with many other like-minded,camera-enabled individuals, that has been foregrounded. Such subjective visionsedited together form a force of first person plural. The emphasis on individual self-expression with the use of personal and digital technologies precisely incorporates‘camera activism’, an important part of China’s iGeneration moving image culture

Studies in Documentary Film 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

that demonstrates the emergence of alternative, non-industry-based filmmakers andsites; the ubiquity of digital technologies and new media; and globalization ofindividualization and self-realization, under the specific conditions of ‘neoliberalismwith Chinese characteristics’(Wagner, Yu with Vulpani 2014, 4).

In addition to confrontational documenting act, and subjective vision, ‘cameraactivism’ indicates another dimension which is collective force among all theparticipants. In Lao Ma Ti Hua, the footage was taken by multiple cameras bydifferent members in the group, including Ai Weiwei himself, the main cameramanZhaozhao. Using Verité and amateur images, sound recording, photos of all theparticipants in the end, Ai and his volunteers construct a first person plural of agroup of rights-conscious selves drawn together by their shared concern forindividual rights. In the next section, this paper will examine how the making ofLao Ma Ti Hua becomes camera activism.

Lao Ma Ti Hua: provocative documentation, first person confrontation, and collectiveforce

The film begins with Ai sitting under a spotlight, directly addressing the camera in amedium close-up. Subsequent to the incident, Ai is explaining the purpose of theirtrip to Chengdu, which is to support an independent investigator Tan Zuoren. As theleader of the project, he addresses the message of the film: ‘We are doing what anycitizen should for fairness and justice in our society’. Emphasizing ‘we’ and ‘our’belief, rather than an individual ‘I’, Ai naturally represents a collective voice ofhimself and his volunteers. By addressing the audience directly, Ai creates aconnection between the participants and the audience. This opening establishes thepolitical gesture of Ai’s group, represented by Ai, seeking social justice for thevictimized children in the Sichuan earthquake, as well as human rights for allChinese individuals in the PRC.

The majority of the film is shot by the main cameraman Zhao Zhao, who is alsoan artist and one of Ai’s closest followers, involved in many of Ai’s investigations.The closeness to the ‘“raw visibility” of the political’(Corner 2009, 115) documentedthrough the Vérite style creates an intimate experience whereby the audience is ableto immerse themselves into what is going on to the character-participants, as eventsunfold.

It is important to notice the changing role of the camera before and after theincident. Ai reveals in an interview that before the incident, the camera serves simplyas a recorder for archival purpose, documenting their journey without an intentionto craft the footage into a film (Sun TV 2011). The handheld image is shaky and inlow resolution. Zhao does not seem to care whether it is too dark or too noisy tofilm, and neither does he intentionally capture anything dramatic. After the incident,Zhao seems to be more conscious of the power of the camera, to record what theyhave experienced as evidence, as well as to disturb local authorities.

In one sequence where one of the participants, Liu, is released from custody,Zhao holds the camera to look for her in the police station to interview her. Zhaodoes not try to hide his identity when he talks to Liu from behind the camera. Theirconversations are not only informative but also expose the audience to more voices,which together construct a rights-conscious collective.

8 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

Zhao exercises the power of camera as an investigator and a weapon, to engage,and provoke the State authorities. His fearless and forceful filmmaking demonstrateshis persistence to fight for individual rights. Mostly using long takes, the images arevery rough. However, this roughness and the imperfect framing indicate thedifficulty in filming, and a sense of being there on spot. In one scene, when thegroup forces themselves into a local police station, Zhao holds the camera facing upfrom a lower angle, pretending the camera is not switched on. As a witness, itcaptures the arguments between the police and the group. At the most fierce point ofthe dispute when it is difficult to film, Zhao puts the camera facing the floor, using itas a secret sound recorder, capturing the evidence of the awkward behavior andprocedures of the police. Ironically, when Ai uses his mobile phone to take a pictureof the police, several policemen also hold up a small DV camera and start to film theprotestors. At this moment, Zhao openly turns his camera toward the faces of thepolicemen. The two groups are in an irreconcilable confrontation, not only throughvoice, but also through cameras as a weapon, and an extension of power. WhileZhao’s and Ai’s cameras are a demonstration of their exercise of rights to film, thepolice’s cameras, on the other hand, are shown as an authoritarian eye keeping thecitizens under control (Figure 2).

In the last scene when Ai’s group comes out of the police station, Ai uses hiscamera to take a picture of the building. Immediately a guard comes to him, askshim to switch off his camera and forces him to leave. Ai insists that he is in a publicspace and should have the freedom to film. Zhao’s camera records this absurdmoment when the policemen aggressively force them to turn off the camera. BecauseZhao’s camera is still on, the policemen do not dare to do anything more violent.When Ai insists on seeing their police IDs, they can do nothing but present the IDsto Ai. (Figure 3).

While Zhao’s recording takes up themajority of the film, twomonumental momentsin the film are Ai Weiwei’s own first person documentation. One is the self-portrait

Figure 2. A police officer in a local police station also films them with a small DV camera.

Studies in Documentary Film 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

photo which I mentioned in the beginning of this paper. The other is a sound recordingmade by Ai’s audio recorder. In the first part of the film, after the group goes back totheir individual rooms, the screen suddenly turns black. At the upper left corner, thetime is shown as: 3 am, 12 August, 2009. In the darkness, we hear the sound of fiercedoor knocking. Ai’s determined voice asks firmly: ‘Who?’ A voice says: ‘Police!’ Aiasks: ‘What police?’No one answers. Ai asks again, and the voice says ‘Police from thelocal police station.’ Ai insists: ‘Why are local cops knocking at my door at this hour?’‘Inspection!’ ‘Inspect what?’ ‘Inspect ID!’ Ai does not yield: ‘Who allows you to checkID at this time? …’

Having been dealing with the police for a long time, Ai is very conscious ofkeeping a record with any means possible. At this point, Ai switches on the soundrecorder to document this moment of violence. As Ai refuses to open the door,demanding a response to the question ‘How can you prove you are the police?’,which is answered by breaking in and beating him. Admittedly, there are elements ofperformance by Ai at this point. While Ai knows that the event is being recorded, thepolice do not. Though Ai is the victim, he clearly has control over how the event willbe interpreted. Facing illegal treatment by the so-called police, Ai does not show anycompromise, but keeps asking in the dark: ‘Is this how police behave?’, which drawsthe audience to question their heavy-handed approach.

Tension between the collective effort and Ai’s individual public image

While ‘camera activism’ focuses on actual action of provocative documentation,Leshu Torchin argues that to have a camera is not enough as images need anideological framework to reinforce the messages that images are meant to convey(2012). In Ai’s camera activism, his celebrity image, just like that of the Americandocumentary-maker Michael Moore, who is well used to deliver messages and

Figure 3. When the police ask Ai not to film, Ai insists on seeing their police identity cards inthe ending sequence of Lao Ma Ti Hua (2009).

10 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

attitudes. Whereas Ai’s public persona as a subversive power becomes increasinglywell-known internationally, he has accumulated authority among his followers. Aiknows well how to use the collective power of his volunteers to construct an activistmessage, and is highly aware of the kind of media attention he can attract. Hesuccessfully articulates the power of art, camera, the Internet, and the media toengage with the public and to achieve an interactive effect on society.

In Lao Ma Ti Hua, some of Ai’s actions are conscious performances of his publicimage. Given Ai’s image as a symbol of resistance to Chinese authority, starting thefilm with his image and voice clearly marks the nature of the film. After the policebreaks in, there is a shot taken in the hotel corridor, in which Ai stands in front ofthe camera wearing a white T-shirt with a big head printed on it. It is difficult torecognize the face – whether it is the face of Tan Zuoren, the independentinvestigator they wanted to defend or Ai’s own. No matter whose face it is on Ai’sT-shirt, Ai standing in front of the camera is clearly a political gesture speaking tothe international audience.

However, Ai increasingly presents himself as a highly individualistic andsometimes ostentatious political figure. When Ai comments on the 2013 contempor-ary Chinese art exhibition at Hayward Gallery London as misrepresented, PaulGladston criticizes Ai’s reductive view of the criticality of Chinese contemporary art.Gladston (2013) points out that Ai’s assertive confrontational approach towardauthority is more easily accepted in the Western democratic context, hence easy togain support from international media; however, it somehow simplifies the specificand complicated conditions of political struggle within China. Raising Ai’s personalvoice does not seem to do much good to the voice he is trying to represent. Behindhis individualistic and even skeptical voice, there are many different voices, whichneither surrender to the state authorities nor are they all identical. How Ai Weiweidestabilizes and decentralizes his own authority has become a question.

In Lao Ma Ti Hua, the individual activists who work with Ai become relative lessknown. One of the major reasons for the making of this film is because of thepersonal incident of Ai being beaten by the police, even though some othervolunteers experienced similar aggressive treatment. The struggle for justice for thecollective victims has become a story about the persecution of the celebrity AiWeiwei. After that, Ai and some other participants visit several local legalauthorities, searching for an explanation. As a power of his own, Ai speaks in alanguage that is highly aggressive and domineering. While the camera is used to as aconfronting power to the authorities, it nevertheless also records Ai’s own speech,which is delivered in a violent dictatorial manner with little space for negotiation. Atthe same time, when Ai is challenging the authoritarian state, he nevertheless mirrorsexactly the authoritarian feature of the system they seek to resist. Following Lao MaTi Hua, Ai has uploaded another documentary So Sorry (Shen biao yi han) (2012),named after his exhibition at Munich in 2009. It is a continuous documentation ofthe life-threatening hospitalization he received from the authorities. While his role asan artist attracts more individuals to participate into his activism, such collectiveeffort also further promotes his artwork.

Beyond the tension between the collective effort by Ai’s activist group and Ai’sindividual public image is what has changed in the larger political landscape in thePRC. Ai’s celebrity image, from its positive aspect, has the potential to encouragemore political participation among young Chinese individuals. As for the state

Studies in Documentary Film 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

authority, it is hard to say whether the large amount of camera activism circulatedon Chinese social media, as well as the series of offline activist movements in the pastfew years have no impact on the recent change of policy. Since the PRC’s newleadership centered around Xi Jingping coming into power in 2013, the anti-corruption movement and the restructure of Chinese civil servant have led to a seriesarrest of corrupted officials from central to regional government, as well as in state-owned enterprises. While Ai himself is still under house arrest, he has undeniablyraised the debates about the possibility of activism in China. Camera activism, asdemonstrated in the political art practice of Ai and many others, provides a channelfor individuals to act as watchdog for social problems.

AcknowledgmentI would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, the special issue editors, my colleagues A.T.McKenna, David Fleming, Paul Martin, and Stuart Danvers at UNNC for their valuablefeedback and comments. I would also like to thank the organizers of public seminar series at LauChina Institute, King’s College London, ‘Documentary Now! Conference’ London, ChineseFilm Forum UK Symposium, British Association for Chinese Studies Annual Conference forgiving me opportunities to present various work-in-progress versions of this paper.

Disclosure statementNo potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Note1. In the year following the incident, 100,000 copies of the film were given out to people. Ai

reviews in his public dialog with Dr Katie Hill at Tate Modern, 2010.

Notes on contributorTianqi Yu is a documentary filmmaker and Assistant Professor of Film and Media Studies,School of International Communications, the University of Nottingham Ningbo China. Shereceived an M.Phil in Sociology from the University of Cambridge, and a Ph.D. from theCentre for Research and Education in Arts and Media, the University of Westminster. Yupublishes on first person documentary, amateur cinema culture, Chinese cinema, culture andart. Yu is the co-editor of China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for theTwenty-First Century (Bloomsbury, 2014). She is completing her monograph ‘My’ Self OnCamera: First Person Documentary Practice in 21st century China (Edinburgh UniversityPress). As a filmmaker, Yu directed and produced Photographing Shenzhen (2007, Discovery),Memory of Home (2009, collected by DSLCollection). Currently she is producing a long termdocumentary China’s Van Gogh (2015).

ReferencesAi, Weiwei. 2009. Lao Ma Ti Hua [Disturbing the Peace]. [Documentary film]. China: Ai

Weiwei Studio.Ai, Weiwei. 2010. Yang Jia - Yige Gupi de Ren [A Lonely Person]. [Documentary film]. China:

Ai Weiwei Studio.Ai, Weiwei. 2012. So Sorry (Shenbiao Yihan). [Documentary film]. China: Ai Weiwei Studio.Ai, Xiaoming. 2004. The Vagina Monologue: Backstage Stories (Yindao Dubai). [Document-

ary film]. China.Ai, Xiaoming. 2006. Tai Shi Village (Tai Shi Cun). [Documentary film]. China.Ai, Xiaoming, and Hu Jie. 2009. Our Children (Women de Wawa). [Documentary film].

China.

12 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

Allan, S., and E. Thorsen, eds. 2009. Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives. New York:Peter Lang.

Aguayo, A. J. 2005. “Documentary Film/Video and Social Change: A Rhetorical Investiga-tion of Dissent.” Doctoral diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Berry, Chris, and Lisa Rofel. 2010. “Alternative Archive: China’s Independent DocumentaryCulture.” In The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement: For the Public Record, editedby Chris Berry, Xinyu Lu, and Lisa Rofel, 135–154. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UniversityPress.

Corner, John. 2009. “Documenting the Political: Some Issues.” Studies in Documentary Film 3(2): 113–129.

Damm, Jens, and Simona Thomas, eds. 2006. Chinese Cyberspaces: Technological Changesand Political Effects. London: Routledge.

Gladston, Paul. 2013. “Getting Over Ai Weiwei”. Accessed November 20. http://www.randian-online.com/zh/np_feature/getting-over-ai-weiwei/.

Hu, Jie. 2004. Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul (Xunzhao Lin Zhao de Linghun). [Documentaryfilm]. China.

Hu, Jie. 2006. Though I Am Gone (Wo Sui Si Qu). [Documentary film]. China.Hui, Wang. 2006. “Depoliticized Politics, Multiple Components of Hegemony, and the Eclipse

of the Sixties.” Translated by Christopher Connery. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 7 (4): 683–700. doi:10.1080/14649370600983303.

Jaffee, Valerie. 2006. “‘Every Man a Star’: The Ambivalent Cult of Amateur Art in NewChinese Documentaries.” In Underground to Independent, edited by Paul G. Pickowicz andYinjing Zhang, 77–108. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York:New York University Press.

Johnson, M. D., K. B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, and L. Vulpiani, eds. 2014. China’s iGeneration:Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-first Century. New York: Bloomsbury.

Lagerkvist, J. 2006. The Internet in China: Unlocking and Containing the Public Sphere. Lund:Lund University.

Lu, Xinyu. 2003. Jilu Zhongguo: Dangdai Zhongguo Xin Jilu Yundong [Documenting China:Contemporary Chinese New Documentary Movement]. Beijing: Shenghuo, dushu, xinzhi,sanlian shudian.

Ou, Ning. 2006. Meishi Street. [Documentary film]. China: Alternative Archive.Qian, Y. 2014. “Working with Rubble: Montage, Tweets and the Reconstruction of an

Activist Documentary.” In China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for theTwenty-first Century, edited by M. D. Johnson, K. B. Wagner, T. Yu, and L. Vulpiani,181–195. New York: Bloomsbury.

Robinson, Luke. 2013. Independent Chinese Documentary: From the Studio to the Street. NewYork: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gregory, Sam. 2005. “Introduction.” In Video for Change: A Guide for Advocacy and Activism,edited by Sam Gregory, Gillian Caldwell, Ronit Avni, Thomas Harding, and WITNESS,xii. London: Pluto Press.

Sun TV. 2011. “(yangguang weishi)’s Interview with Ai Weiwei.” Accessed September 30,2011. http://loveaiww.blogspot.com/2011/09/blog-post_2825.html.

Torchin, Leshu. 2012. Creating the Witness: Documenting Genocide on Film, Video and theInternet. Milleapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wagner, Keith B., Tianqi Yu, with Luke Vulpiani. 2014. “China’s iGeneration Cinema:Dspersion, Individualisation and Post-WTO Moving Image Practices.” In China’s iGenera-tion: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-first Century, edited by M. D.Johnson, K. B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, and L. Vulpiani, 1–20. New York: Bloomsbury.

Wang, Yiman. 2005. “The Amateur’s Lightning Rod: DV Documentary in PostsocialistChina.” Film Quarterly 58 (4): 16–26.

Whiteman, D. 2004. “Out of the Theaters and Into the Streets: A Coalition Model of thePolitical Impact of Documentary Film and Video.” Political Communication 21 (1): 51–69.doi:10.1080/10584600490273263-1585.

Yan, Yunxiang. 2009. The Individualization of Chinese Society. London: London School ofEconomics Monographs on Social Anthropology.

Studies in Documentary Film 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5

Yan, Yunxiang. 2010. “Introduction: Conflicting Images of the Individual and ContestedProcess of Individualisation”. In iChina: The Rise of the Individual in Modern ChineseSociety, edited by M. Halskov Hansen and Rune Svarverud, 1–38. Copenhagen: Nias Press.

Yang, Guobin. 2009. The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online. New York:Columbia University Press.

Zhang, Zhen. 2012. “Yishu, Gandongli, he Xingdong Zhuyi Jilupian [Art, Affect, ActivistDocumentary].” Zhongguo Duli Yingxiang [Chinese Independent Cinema] (11).

Zhao, Liang. 2009. Petition (Shang Fang). [Documentary film]. China: 3 Shadows. France:Arte France, UK: BBC Storyville.

14 Tianqi Yu

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

192.

184.

34.1

86]

at 2

0:11

26

Febr

uary

201

5