Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists: Xunantunich and its Neighbors (2010)

-

Upload

ucriverside -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists: Xunantunich and its Neighbors (2010)

CHAPTER 3

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists Xunantunich and Its Neighbors

WENDY ASHMORE

IN PROPOSING A THEORETICAL BASE for interpretation, Lisa LeCount and Jason Yaeger (chapter 2) focus critically on models for strategies of incorporation, outlining implications of these strategies' application to Xunantunich. While the authors emphasize the interrelated roles ofgift giving, tribute exaction, marriage alliance, warfare, and political ritual in fluctuating strategies of state building, they also underscore the need to assess how the actions taken are received at varied scales-by external friends and foes, as well as by those within this or any polity. Most directly pertinent to this chapter, they argue that "states, polities, centers, and communities should be viewed as operating within complex social, political, and economic landscapes" (chapter 15), and that "the growth of Xunantunich transformed the political hierarchy within the upper Belize Valley centers" (chapter 15).

In the early seventh century, Xunanhmich emerged as a political center within fluid social, political, and economic milieus whose formation had begun nearly two millennia earlier. This chapter articulates local histories for the world around Xunantunich, with most detail for the seventh century through the tenth century. Consideration of nearby nodes, from Actuncan to Pacbihm, complements reflections on imposing but more distant foci, at Naranjo, Tikal, Caracol, and Calakmul, as well as on peasantry in the ambit oflarger polities. An overview of cumulative evidence and recent interpretations emphasizes implications for alliance, annexation, destructuration, and other strategies, as well as for responses to these strategies. The goal is to identify potential participants in, and their varied impact on, the founding, growth, and ultimate dissolution of the Xunantunich polity. To link these histories most clearly to developments in that provincial domain, discussion follows the chronological periods

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 47

established for Xunantunich (LeCount et al. 2002; LeCount and Yaeger, <LA Brief Description ofXunantunich," this volume).

Background Conditions: Pre-Sarnal (Sixth Century AD and Earlier)

Antecedents to the main periods of concern join together a long span of time and a complex array ofevents and developments. Perhaps their most

important aspect is the set of precedents and foundations they established. That is, together these antecedent people, places, and customs map out founding and immigrant groups, competing and complementary interests, and initial strategies for living, for coexistence with each other and in the larger world.

Within the area shown on figure 1.1, agrarian settlement was well established by the end of the second millennium BC. While individual households tended toward economic self-sufficiency, possessions and

mortuary practices point to diverse social identities among members of these fanning families. Ball and Taschek (2003) argue that the populace comprised at least two culhlfally and perhaps linguistically distinct groups. Local architectural fonns materialized rihlal performance among local populations of the Middle and Late Preclassic (9°0-100 BC), notably including a series of round platforms (Aimers, Powis, and Awe 2000).

Elsewhere, seemingly isolated monumental platfonns served ritual gatherings (e.g., Robin et a1. 1994). Caves and other landscape features, as well, were recognized in ritual visitations marked by materials left behind (e.g.,

Healy, Song, and Conlon 1996; Laporte et a1. 1994). That is, although neither ubiquitous nor uniform in appearance, these constructed and

natural features signaled crystallizing canons for settings of social integration, plausibly involving formalized ancestor veneration in a decidedly

public setting (cf. Brady 1997; Burger and Salazar-Burger 1986; McAnany

1995). Evidence for social hierarchy had emerged as an autochthonous development by at least AD 1 (e.g., Ford and Fedick 1992; Laporte and Mejia 2002; Willey et a1. 1965; Yaeger 2oo3a), and Joseph Ball and Jennifer Taschek (2003,20°4) are among those who place this emergence as many as five hundred years earlier.

By Middle and Late Preclassic times, a series of small centers had arisen across the same territory. Nearest the ridge that became Xunantunich,

48 WENDY ASHMORE

these places included Actuncan, Arenal, Blackman Eddy, Buenavista del Cayo, Cahal Pech, El Pilar, Nohoch Ek, Pacbihm, and Xunantunich itself

(Awe 1992; Ball and Taschek 2003, 200~ Ford and Fedick 1992; Garber 2004; Garber, Brown, and Hartman 1996; Healy 1990; Healy and Awe 1996; McGovern 1992; Taschek and Ball 1999; Yaeger, "Landscapes of the Xunantunich Hinterlands," this volume). Topographic locations varied from valley terraces (e.g., Actuncan, Buenavista del Cayo) to hilltops (e.g., Arenal, Blackman Eddy, Cahal Pech, Xunantunich), and the frequency of

open settings suggests that defensive siting was not a principal concern. Ball and Taschek (2003=210) argue, however, for long-term co-occupation ofthe area by "two distinct interacting groups competing for ascendancy." And Kathryn Brown and James Garber (2003) go further, identifying evidence of conflict in architectural desecration at Middle Preclassic Blackman Eddy. Whatever the political climate, these emerging settlement nodes were affiliated with nearby agrarian villages, and they contained formal plazas, platforms, and even pyramids, up to 27 m in height. Both architechue and artifacts mark the places as focal points for communal gatherings as well as, in many instances, nascent displays of wealth and authority.

Some places, such as Baking Pot, Blackman Eddy, Cahal Pech, and EI Pilar, included architectural arrangements resembling Uaxactun's "E-Group" solstice-equinox observatory, suggesting local leaders' strategy

ofaffiliation by emulation, in this case adopting particular elite-organized customs and creating the facilities appropriate to their performance and witness (e.g., Aimers and Rice 2006; Ashmore 1986; Chase and Chase

1995; Fialko 1988; Healy, Hohmann, and Powis 2004; Jamison, chapter 5). Early versions of these distinctive architechual assemblages are known from Middle Preclassic contexts at Uaxachm, Tikal, Naranjo, Nakbe, EI Mirador, and other sites in the Mirador Basin, as well as Caracol far to

the southeast (Fialko 2005; Hansen 1998). For Arlen Chase and Diane Chase, the significance of these groups is as a hallmark of "the reformulation of Preclassic Maya society into its Classic period sociopolitical and dynastic patterns [inasmuch as the E-Group] served as an architecturally standardized focal assemblage for integrating Late Preclassic and subsequently Early Classic Maya populations, first ritually and then dynastically" (1995:100-101). As materialized strategies, then, they reflect local self-promotion and affiliation by emulation. Similar attributions pertain to ballcourts and polychrome stucco masks, as discussed later.

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 49

Equally important for this discussion, the aforementioned local centers established what became enduring foci in the regional landscape. Garber suggests that positions of places from Xunantunich east to Blackman Eddy defined a cosmogram, pivoting on Cahal Pech and established in Middle Preclassic times. Collectively, these nodes partitioned the world into quarters according to Maya belief, mapped the world's creation through mythic activities at each of the collective positions, and provided arenas-ultimately linked to ballcourts-for ritual recreation ofthe world

in concert with key, cyclical astronomical events (Garber 19<)4; Mathews and Garber 2004). Such center-organized moves to situate the populace

within the well-ordered universe may relate to what William Ringle (1999) has suggested was a Preclassic dialectic exchange between emergent elites and potentially restive commoners in an increasingly stratified society; centralized labor demands for monumental, public, core construction were answered by more elaborate household shrines for individual high-ranking houses, which were met in turn by what were arguably intended, at least in part, as measures for local social integration. Materially, these included facilities for witnessing and even participating in political ritual, including ballcourts and causeways (cf. Helmke and Awe 2008; Rathje 2002).

For several of these same key sites (Actuncan, Blackman Eddy, Cahal Pech), architectonic stucco masks constitute material reference to other Late Preclassic and Early Classic elite idea systems known broadly in the

Maya lowlands (e.g., Garber, Reilly, and Glassman 1994; McGovern 1994; cf. Freidel 1979; Hansen 1998; Sharer et a1. 1999), as did Late Preclassic or Early Classic erection of stone monuments, bearing sculpture in at least

Blackman Eddy (Garber 1992; Garber et a1. 2004), Actuncan (McGovern

1992), and Pacbitun (Healy 1990; Healy, Hohmann, and Powis 2004). Although-as noted earlier-open site layouts, accessibility of settings, and lack of fortifications would seem to imply that raids or other military actions were relatively infrequent, the parallel growth of closely spaced centers such as Actuncan, Arenal, Buenavista del Cayo, Cahal Pech, Minanha, and Pacbitun nonetheless implies sustained competition for local labor and agricultural resources. It is possible, if undemonstrated, that contemporary Belize Valley stelae were already marking borderlands oflarger polities-linking Pacbitun with Caracol's domain, for example (cf. Chase and Chase 1998; Helmke and Awe 2008; Iannone 2001). The ridge top atXunantunich, however, seems to have remained a place solely

50 WENDY ASHMORE

for ritual, perhaps a pilgrimage destination (e.g., Brady and Ashmore 1999; also Keller, chapter 9).

Farther afield, early expressions of Maya statecraft were well underway. Warfare and defensive moats and walls had certainly appeared, as presumably had less-bellicose diplomatic and economic relations among solidifying polities. Imposing monumental centers at Nakbe and EI Mirador had already flourished and declined by AD 100. The nature and extent ofeach of that pair's wider connections and support populace, as well as their identity as states and the reasons for their decline, all remain incompletely understood (but see, for example, Folan, Marcus, and Miller 1995; Hansen 1998; Rathje 2002), although climate shift with regional warming and desiccation has been cited as a potential factor in their dissolution. In the meantime, however, Calakmul and Tikal had embarked on trajectories of demographic and architectural growth that would influence polity dynamics and state building across the Maya lowlands for more than

half a millennium (Folan 1992; Folan et a1. 1995; Jones 1991; Martin 2003; Martin and Grube 2008; Pincemin et a1. 1998; Rice 2004; Sabloff 2003). The centuries-long political competition between Calakmul and Tikal is manifest in their successive sovereigns' diverse ploys for incorporating,

manipulating, or destroying smaller Maya polities, as well as their varying degrees of success in doing so (e.g., Culbert 1991; Martin and Grube 2008). Whereas the primary evidence for specific actions is epigraphic,

their effects can be discernible in the material record, as can responses to such actions.

Impact of the two "superpowers" on the region under concern here is attested sporadically at some locales, such as Ucanal, a place founded in Preclassic times and said to be under Tikal sponsorship in the mid-fifth

century (Laporte and Mejia 2002:3+ 39; Martin and Grube 2008:34-35). Juan Pedro Laporte and Hector Mejia (2002) note marked distinctions at that time between Ucanal and contemporaries in the middle and upper Mopan River valley, especially Ixkun and Calzada Mopan. Specifically, they note material contrasts in ceramic spheres and settlement patterns; they then suggest that the implied contrasts in social and economic networks, and presumably in alliances, helped foment the other sites' more pronounced growth, and further, that these disparities in affiliations and fortunes may have been seeds of later, eighth-century conflict among them (Laporte and Mejia 2002:41).

51 Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists

Most explicit and detailed, however, are the many texts describing the superpowers' interventions at Naranjo and Caracol. Both of the latter have archaeologically attested foundations in Preclassic times, and by the sixth century, they had long since become imposing polity capitals (e.g., Chase and Chase 1996a, 2003; Fialko 2005). Ruling houses at each were shaping forces in the region of interest here, and the reach of their kings was shaped, in tum, partly by war and diplomatic relations with their own overlords. Notably, Calakmul's king supervised the accession ofAj Wosal Chan K'inich, the subject-king at Naranjo whose loyalties to his overlord endured from AD 546 to 615 (Martin and Grube 2008:72). In contrast, Caracol's fealty and fortunes fluctuated dramatically with reference to Tikal and Calakmul, especially in the sixth century (Martin and Grube 2008:88~1). Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube summarize the wider impact ofalliances, annexations, and attacks thus: "During the sixth and seventh centuries [Calakmul] eclipsed its arch-rival [Tikal] and succeeded in building a widespread 'overkingship,' whose influence was felt in the farthest comers of the Maya world" (2008:101, also 20-21). It was within this world that Xunantunich as a polity center arose.

Context at Emergence: Samal (ca. AD 600-670)

For some reported chronologies, it is difficult to apportion Late Classic developments to specific spans within the larger period. It is clear, however, that by the early seventh century, the agrarian populace of the region had grown significantly. Indeed, B.L. Turner (1990) estimated the populace for the "Tikal" region at a bit more than 180,000 in 300 BC, less than 350,000 in AD 300, and more than 400,000 in AD 600, all within some 870 km2

embracing northeastern Guatemala from the central Peten lakes, north to Rio Azul, and east to encompass the upper Mopan River drainage. While analysts usually consider this area to have been more densely settled than the region most pertinent to this volume, the estimates are nonetheless instructive, and comparisons may be closer between such regions than sometimes thought (Neff 2008, also chapter 11). Certainly, numbers and densities varied within the region of interest, and scale of analysis can obscure that variation, artificially masking diversity (e.g., Chase and Chase 2003; Ford and Fedick 1992). In relative terms, settlement at Barton Ramie reached 85 percent of its ultimate maximum between AD 600 and 700,

52 WENDY ASHMORE

and the populace documented by the Belize River Archaeological Settlement Survey (BRASS) attained 98 percent of its maximum size between

AD 600 and 800 (Ford 1985, 1990; Willey et al. 1965; Yaeger 2003a:51). The time depth of household gardens plausibly reaches back at least this far (Ball and Kelsay 1992; Neff 2002; Robin 1999, 20023, 2002b, 2006), as does agricultural intensification by terracing (Neff 2008, also chapter 11;

Wyatt 2008). Whether occurring in this or later years of the Late Classic, Scott Fedick's data (1988,1994) suggest that intensification, at least north of the Belize River, was instigated at the household level: the small scale of the terracing that he observed "is no basis for suggesting the existence of a centrally controlled program of terrace development. Construction of the terraces does indicate a willingness by households to invest labor in land development, suggesting a secure pattern ofland tenure" (Fedick 1994:124). It may also (or alternatively) have involved response to tribute exactions, as imposed on and met by individual households.

As before, most households were those of farmers. Craft production was commonly associated with peasant households, but with economic diversity, specialization, and acquisition privileges among those households still relatively little developed (e.g., Ford 1991; Ford and Olson

1989; VandenBosch 1999; Willey et al. 1965). Social differentiation and hierarchy were undeniably present, however, as attested increasingly and emphatically by differences in mortuary offerings and architechtral investment in individual household groups throughout the social scale (e.g., Willey et a1. 1965; Yaeger 2°°3a; Robin, Yaeger, and Ashmore, chapter 14)' At the same time, some consistencies ofcustom became pronounced and unifying, notably a canonical preference across social rank for supine extended burials (e.g., Healy 1990:255; Willey et a1. 1965; Yaeger 2oo3a).

In light of observed differentiation, factions and competition were doubtless present, although evidence of the strategies for mitigating (or exploiting) such rifts are not always clearly assignable to this particular part of the Late Classic span. Gift exchange helped cement some vertical relations, as sumptuary or prestige goods apparently moved down the hierarchy. Well-known gift categories include fancy pottery, shell, jade or other greenstone, and the eccentric flints encountered widely in medium- to large-scale centers in the region (e.g., Freidel, Reese-Taylor, and MoraMarin 2002; Iannone 1992; leCount 1999). Feasting also solidified social bonds, at varied social scales, even as it helped underscore differential

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 53

abilities to host such events (Ashmore, Yaeger, and Robin 2004; Blackmore 2008; Connell 2003; LeCount 2001; Robin 2002b; Yaeger 2000a, 2000b; LeCount, chapter 10). Among commoners, evidence points to essential self-sufficiency in daily life, if with variable interdependence among peer households for some tools and supplies (e.g., VandenBosch 1999, also chapter 12).

Indeed, writing of the Classic lowland Maya generally, Patricia McAnany (1992:86) sees possibilities for "a significant degree of economic autonomy within the agrarian class as one moved beyond the political economy (appropriation of a stimulated surplus or corvee labor)" (see also Lohse and Valdez 2004). Such autonomy would relate directly to variation in political centralization. Localized decision making seems to have marked the decentralized area north of the Belize River, 10--20 km downstream from Xunantunich (e.g., Fedick and Ford 1990). Despite some clustering of settlement around elite centers such as El Pilar, and possible reservation of alluvium for cacao production (e.g., Fedick 1989; Willey et a1. 1965), distribution of habitation sites in this long-occupied area correlates strongly with the soil classes Fedick describes as most attractive to ancient farmers, from which he infers those farmers' relatively high freedom of locational choice (e.g., Fedick 1988, 1995; Fedick and Ford 1990).

Similar distinctions in access and tenure may pertain in the Chaa Creek-EI Chial zone, where the flat, fertile El Chial expanse seems to have been reserved for agricultural production rather than residence (Connell 2003)' The small alluvial pocket along the Maca!, at NegromanTipu, may be yet another such example (Muhs, Kautz, and MacKinnon 1985), with control plausibly vested in the little-known monumental center at Guacamayo (Neff et a1. 1995). Although Guacamayo has yet to be surveyed (Neff et al. 1995:145-46), it is said to have at least four major architectural groups, the largest of which included several structures estimated at 15-20 m high.

Elsewhere, correlation of settlement location with agrarian considerations is loosely consistent but demonstrably more complicated. In the Valley of Peace, for example, Lisa Lucero and her colleagues (2004) contend that aspects of the sacred landscape-prominently the pools of Cara Blanca - make it clear that some agriculturally "poor" lands may be nonetheless significant places.

54 WENDY ASHMORE

All of these instances, however, stand in opposition to more centralized contexts, like Caracol, in which rulers closely managed both land tenure and the development ofagricultural technology, as implied by the regularly arranged agricultural terraces amid the dense settlement (e.g.,

Chase and Chase 1990, 2003; Healy et a1. 1983). The region's centers of ritual and governance, noted previously, dem

onstrated varied records of fortune, decline, and realignment. South and east of Xunantunich, for example, such places as Minanha and Pacbitun began what was to be their main period of construction growth (Healy

1990:257; Healy, Hohmann, and Powis 2004; Iannone, Connell, and Menzies 2001:1). At the latter site, tomb burial ofa probable ruler is ascribed to the Coc ceramic phase (ca. AD 550-700). That intemlent involved not only Spondylus shell head gear like that ofconfirmed royalty elsewhere (Healy

1990:257; Healy, Awe, and Hellmuth 2004), but also the regional preference for supine burial described earlier and a widespread and longstanding lowland Maya practice of interring authority figures in eastern shrines, often monumental in size (Becker 2003:258-262; Chase and Chase eds.

1994) and in this case, the largest structure at the site (Healy 199°:251). Both centers may well have been subordinate to Caracol at this time.

Polities in the middle and upper Mopan Valley were perhaps shifting alliances and networks. At Ucanal as well as other sites in the area, the ceramic assemblage, notably the presence of red-slipped ash ware, indicates affinity with ceramic traditions of Belize and the Caribbean coast (Laporte and Mejia 2002:28), suggesting that political and economic relations were oriented east and south more uniformly than they had been in preceding centuries. Still, intravalley contrasts in settlement and polity organization persisted, as plausibly did factionalism and conflict.

For Xunantunich, LeCount and Yaeger relate political establishment directly to the fortunes of Naranjo during the turbulent seventh century. Although the exact relationship between the two remains unclear, the effort expended on initial construction ofthe Castillo without the aid ofa large hinterland population signals significant ties to outsiders (LeCount and Yaeger, chapter 15; Leventhal, chapter 4). A member ofat least local nobility was interred in Structure A-4, the southern pyramid ofthe hilltop center's E-Group. And polychrome sherds dating to the time ofAj Wosal Chan K'inich found within early Castillo fill levels point to connections

with the Naranjo ruling house (LeCount and Yaeger, chapter 15).

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 55

The overarching political and economic climate in this period, however, highlighted shifting relations between Calakmul and both Naranjo and CaracoL In AD 626, eleven years after Naranjo's Aj Wosal Chan K'inich died, his successor (whose name remains unkno\\tTI) broke the enduring alliance with Calakmul. Choosing to wage war on both Caracol and their mutual overlord, the unnamed Naranjo king was in turn decisively defeated in AD 631, "almost certainly ... at the hands ofCalakmul" under its king, Yuknoom Head, and his Caracol vassal, K'an II (Martin and

Grube 2008:72, 92). The effects of war can include enhanced prosperity, as illustrated in K'an II's Caracol, where an expanded road system, growth in monumental core architecture, and the famous hieroglyphic stairway describing the AD 631 assault (in Caracol style, ultimately recovered in large part at Naranjo) are among the better-known material byproducts

(e.g., Chase and Chase 1987, 1989, 2003; D. Chase and A. Chase 1998; Martin and Grube 2008:73, 92). Where battles ended in defeat, the results are different, but not always catastrophic: at Tikal, despite severe effects of war at the level ofroyalty, "evidence suggests that political upsets between AD 562 and 682 had little effect on most people" (Haviland 2003=140).

These first seven decades of the seventh century were thus times of disruption and reorientation in the region's political landscape, and possibly its economic landscape as well (cf. Helmke and Awe 2008). Alliance networks associated with Tikal were relatively reduced in efficacy, while those linked ultimately to Calakmul benefited by relations with Caraco1. In contrast, provinces for which the intermediary link was Naranjo were compelled to weather the documented turbulence in its fortunes as best their own strategies allowed them. The times and fortunes, however, were about to change.

Context of Florescence: Hats' Chaak (ca. AD 670-780)

The next eleven decades, associated with Hats' Chaak ceramics at Xunantunich, were times of accelerated transformation at that center, as discussed extensively elsewhere in this volume. In general, these were years of prosperity, dramatic new construction, and growth in much of the region of concern in this book (e.g., Iannone 2001; Taschek and Ball 1999:222). And population maxima seem to pertain most closely to this

century (e.g., Ford 1990; Willey et a1. 1965; Yaeger 2oo3a; Neff, chapter n).

56 WENDY ASHMORE

Within the same span, however, the boom times also witnessed widespread upheavals and alterations, at varied scales ofsocial interaction.

On a relatively localized scale, for example, the small site of Zubin, very near Cahal Pech, had been since ca. 850 Be solely a ritual gathering place, perhaps a focus of pilgrimage. «Sometime around AD 675," however, it was reconstituted as «a moderately restricted, internally differenti

ated, rural farmstead" (Iannone 2°°3:15, 24)' Gyles Iannone interprets the change as a form of resistance, in his words, "denial of complete

Cahal Pech control" (2003:24), and perhaps representing greater sharing ofgovernance with old established families in the hilltop center's domain (compare implications of such sharing at eighth-century Copan: Fash et al. 1992). In contrast, the nearby site ofX-ual-Canil evinces what appear to be direct intervention and successful attempts at control by Cahal Pech. That is, X-ual-Canil was established relatively abruptly in the Late Classic, adjacent to a long-standing, dispersed farming populace too small in aggregate to have supplied the new site's requisite construction labor, and creating a place designed specifically for the administration of local water and land, with both ritual and economic management emanating directly from Cahal Pech (Iannone 2003). These inferred dynamics are particularly intriguing in comparison to the assertiveness ofXunantunich sovereigns in the lives of established (or re-established) communities under their sway (e.g., Robin 1999; Yaeger 2oooa, 2000b; also see Connell, chapter 13; Robin, Yaeger, and Ashmore, chapter 14) and all happened in tandem with multifaceted renegotiations and strategic shifts in other segments ofsociety.

Farthest up the political scale, the same eleven decades witnessed both the fragility and dramatic resilience of established alliances, in addition to frequent war, all attested to archaeologically as well as epigraphically. It was thus a time when social, political, and economic relations, old and new, were negotiated at multiple social scales. Setting the tone were three critical actions, and the processes and responses they set in motion. First, the thirty-seventh ruler of Naranjo, whose name we do not know, is said to have driven CaracoI's ruler briefly from his own capital; with that attack in AD 680, he set the stage for revitalization ofhis polity lasting some sixty years and initiated a political crisis at Caracol that lasted even longer, until the end of the eighth century (Martin and Grube 2008:73, 95). Second, Calakmul's king Yuknoom Yich'aak K'ahk', an important architect of

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 57

alliance and intrigue, installed a new dynasty at Naranjo in AD 682. lbird, in AD 692, Tikal's king Jasaw Chan K'awiil I (Ruler A) inflicted a crushing defeat on his archrival Yuknoom Yich' aak K'ahk' ofCalakmul, overlord of the deeply mutually contentious Naranjo and CaracoI. According to the textual record, the major political lines had been redrawn significantly, with major players continuing in greatly altered roles. Changes in tlle material record broadly substantiate this as a time of major initiatives and adjustments.

With Naranjo's resurgence in AD 680 and 682, alliances with the upper Belize River valley were reaffirmed. A well-known illustration of such affirmation is the "Jauncy" vase from Buenavista del Cayo, recovered from the early eighth<entury tomb of a young man, probably a member of the local royal family (Houston, Stuart, and Taube 1992; Reents-Budet 1994; Reents-Budet et a1. 2000:117; Taschek and Ball 1992). The Holmulstyle cacao drinking vessel was probably commissioned and owned by Naranjo's ruler, K'ahk' Tiliw Chan Chaak (Houston, Stuart, and Taube 1992; Reents-Budet et a1. 2ooo:u7), presented as a gift for the young man's father (1aschek and Ball 1992:494) in a gesture confirming the alliance.

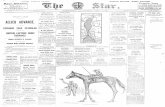

The massive growth spurt at Xunantunich early in the time of Hats' Chaak ceramics corresponds more dramatically with re-establishment of Naranjo control under Lady Six Sky and K'ahk' Tiliw, who may have directly annexed this Mopan Valley subordinate. Alternatively, it remains possible that other local allies-perhaps the ruling house at Actuncanintensified affiliation with Naranjo. Whoever was in charge physically transformed the hilltop site, emulating key portions of the civic cores at both Naranjo and Calakmul (Ashmore 1986, 1998; Ashmore and Sabloff 2002; also Keller, chapter 9), and the locally unprecedented capacity to command local labor and materials is perhaps most consistent with outside intervention by the revitalized state and dynasty at Naranjo (see fig. 3.1). By the time the voluminous Str. A-I was erected, local labor tribute exactions would have been solidified, and the construction units comprising the fill in A-I plausibly marked tribute and fealty within province bounds (Zeleznik 1993)' In AD 744, however, texts assert that Naranjo was soundly defeated by a resurgent and imperialist Tikal under Yik'in Chan K'awiil (Ruler B; Martin and Grube 2008:49, 78-79), a king who not only waged further campaigns in the Naranjo-Yaxha region (Martin and Grube 2008:32) but also reaffirmed his and his capital's importance

Naranjo, Group B

FIGURE 3.1. Comparison ofXunantunich and Naranjo architectural layouts (after Keller 2006: fig. 7.1).

.~. .. "1G .

® BaIiCourt2~

Xunantunich, Group A

meters _-_-:oJ o 50 100

Plaza A-II

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 59

by monumental construction projects (Jones 1991) that included transforming Tikal's core into a huge cosmogram (A<;hmore 1989). The same expansionist sovereign likely re-opened Tikal's economic and other connections eastward, with implications for Xunantunich considered later.

Whoever commissioned the transformation ofXunantunich, the advantages of claiming its control were indisputably substantial, prominently including its unequalled 36o-degree view, for military as well as more pacific administrative use. Such a claim also restated the long-standing significance of the mountain location, a fixture on the ritual landscape since Middle Preclassic times, when a cobble causeway may have linked

it to Actuncan (Neff et a1. 1995; Keller, chapter 9; see also Garber 1994; Taschek and Ball 2004).

Evidence for increased local militarism is ambiguous, thus far pointing to a strategic wariness (i.e., creation ofsight lines among hilltop locations) rather than evidence of battles or formal fortifications. Even ifXunantunich's ridgetop location was chosen in part for its defensive advantage, its founding as a civic center took place while the more openly situated centers of Buenavista del Cayo, Arenal, and Achmcan were still active. Warfare was frequent elsewhere in the region during these years. Before it was subject to defeat in AD 744, Naranjo was quite aggressive, and its "Stela 22 alone reads like a conflagration of the eastern Peten" (Martin and Grube 2008:76).

Certainly, the larger dynamics sometimes affected subject polities profoundly. At Minanha, for example, Iannone suggests that

In broader tenns, it is likely significant that Minanha saw its greatest period ofgrowth during the eighth century AD, after Naranjo had gained independence from Caracol (ca. 680 AD), and during a period when both Naranjo and Caracol were relatively quiet on the regional front. ... the mimicry of CaracoI's royal residential compound and stelae monuments can be interpreted as evidence of Minanha's semi-independent border centre status during the eighth century AD. (Iannone 2001:131).

This strategy for architectural expression is reminiscent ofXunantunich's emulation of Naranjo and Calakmul, likewise in a period of ascendance for the transformed center involved. Chaa Creek provides an additional instance, in part reminiscent ofstrategies and responses at Minanha, albeit

at a smaller spatial scale (Connell 2003, also chapter 13)'

60 WENDY ASHMORI';

These accounts are partial substantiation for the remark~ quoted earlier, that the growth ofXunantunich transformed the political hierarchy within the upper Belize River valley centers. In that regard, Taschek and Ball direct particular additional attention to

the relations between the eighth to ninth centuries for the lower Rio Mopan zone-essentially the same local realm likely controlled by Xunantunich through the ninth century and into the tenth century .... The relationship ofXunantunich to Las Ruinas [de Arenal] also warrants attention~ as the latter small center appears to have experienced its final surge of public monumental construction during the same late eighth- to ninth-century span that saw the site of the ridge top rise to preeminence. (Taschek and Ball 1999:232)

The same authors specify Arenal as experiencing that surge between AD 737 and sometime around AD 900 or after (Taschek and Ball 1999:222). Yaeger (personal communication, 2004) notes that it is tempting to correlate at least part of the surge with Naranjo's defeat by Tikal in AD 744. Relations with Xunantunich and other peers and competitors still remain to be resolved, but whether through competition or alliance, the results seem to have been beneficial to many.

Similar inquiries about relations could be posed productively~ if not conclusively, concerning relations between Xunantunich and other contemporaries, at Cahal Pech, Actuncan, and Buenavista del Cayo. All persisted as foci, but their relative hold on the surrounding populace seems to have shifted, at least in some cases. An intriguing case in point is some apparent reorientation of peasant affiliation from Buenavista del Cayo toward Xunantunich, in Hats' Chaak times. Pottery of diagnostically Samal-phase types was remarkably pronounced in test-pit yields from the platform center of Callar Creek and adjacent farmsteads, all nearly opposite Buenavista del Cayo, across the Mopan River (Ehret 1995; Yaeger 2008). On an open platform most directly visible from Buenavista del Cayo, Callar Creek also exhibited what may be stumps of three broken stelae, as if oriented for visibility from the larger site across the river (Ehret 1995). These data, alone, are not indisputable evidence of local attachment to Buenavista del Cayo. Subsequent changes support that inference, however. That is, changes at Xunantunich, and relations between Buenavista del Cayo, Actuncan, and Xunantunich, appear to

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 61

have changed the intervening political, demographic, and economic

landscape, for that same occupation zone around Callar Creek yielded a paucity of Hats' Chaak sherds, simultaneous with pronounced expansion

ofoccupation in zones closer to Achmcan and Xunantunich (Ehret 1995)· Based on complementary evidence, Taschek and Ball (2004:2°3) likewise believe that Xunantunich had supplanted Buenavista del Cayo as local

paramount by the end of the eighth century (also Helmke and Awe 2008).

Still to be addressed are the wider range ofstrategies and counterstrategies adopted by nonroyal sectors of regional society. Not only was this

a time of population maxima, it was also surely a time of agricultural

intensification (Fedick 1994; Healy 1990; Neff 2008, also chapter 11). The general level of prosperity seems to have attracted new residents to even

nonoptimal locales at Chan Nobhol (Robin 1999; also Robin, Yaeger, and Ashmore, chapter 14), newcomers who were also then responsible

for contributing to the agricultural productivity. Tribute exactions on this productivity have been prospectively linked to needs (or claims) at

Tikal (Ashmore, Yaeger, and Robin 200~ Culbert 1988), but could also have been directed to the coffers at war-ravaged Naranjo as well as to the province of Xunantunich itself. As militarism among the larger polities

grew during the Late Classic, and as demand increased for foodsht:ffs to

feed their beleaguered populations, the natural attractions of this part of the Belize River valley area likewise rose. Within what had always been an

important corridor and, in some stretches, a breadbasket (e.g., Fedick and

Ford 1990; Willey et a1. 1965), control of the area's productive resources was increasingly coveted (Ashmore, Yaeger, and Robin 2004).

Craft production continued to be associated principally with commoner households. Two exceptions are the slate and shell production in the nobles'

compound, Xunantunich Group 0 (Braswell 1998, also chapter 8), and the potters' workshop reported from a "palace" context at Buenavista del Cayo

(Ba111993; Ball and Taschek 200~ Reents-Budet et a1. 2000). Both seem to represent attached specialists, and their products were currency in social

relations. Those in Group 0 underwrote the elite standing of the compound heads, while those in Buenavista del Cayo were involved in larger networks of production and consumption, controlled by and for the benefit of royal houses from Holmul to Naranjo and beyond (Reents-Budet et a1. 2000).

By AD 780, however, the stability and effectiveness ofall these strategies was about to be challenged severely.

62 WENDY ASHMORE

Context for Dissolution: Tsak' (ca. AD 780-890)

The succeeding eleven decades witnessed developments overshadowed by

violence, reprisal, decline, and dissolution in much of the region. Population was stilI high at Barton Ramie, but it declined significantly in the area

investigated by BRASS (Ford 1990; Yaeger 2oo3a). Other places manifested variable records of continuity or decline. In Martin's words, "it is clear that the falls of the most important Classic dynasties were closely spaced

in time" (2003:34-35). Among supraregional powers, TikaI's twenty-ninth ruler, Yax Nuun Ahiin II (Ruler C), commissioned monumental works,

including the final pair and largest of the city's Twin Pyramid Groups, in

observance of the katun-endings of AD 771 and 790, but inscriptions of his reign fade in number and length (Jones 1991; Martin 2003; Valdes and Fahsen 2004). Caracol underwent a renaissance of sorts, and its satellite communities prospered in these times as well. The dynasty, however, seems

to have failed after AD 830, and the last text seems to be at AD 859, pointing

to occupation "amid the crumbling city" (Martin and Grube 2008:99)' And while Calakmul endured as a city into Colonial times, it never fully

recovered from its crushing defeat at the hands ofTikal's forces in AD 692.

On a more localized scale, by at least the 750S, Ocana} was politically superior to its neighbors in the middle and upper Mopan Valley. But with the exception of its relations with Sacul, interactions were not harmonious

(Laporte and Mejia 2002:35-36; see also Laporte 2004). By AD 780, Dcanal had been "destroyed" by Ixkun and had become a vassal of Calakmul. In AD 800, however, Caracol Altar 23 shows Dcanal's king as a bound

captive, along with the king of the unidentified site of B'ital (Martin and

Grube 2008:97)' Then, twenty years later, Dcanal was again in Caracol's good graces, and in that same year, it was honored to host ceremonies presided over by Naranjo's last documented king, as recorded on Stela

32 at the latter site. Nevertheless, tlle archaeological record suggests its

fortunes ultimately declined, such that Ixtonton, farther south, supplanted

Dcanal in the region - itself persisting as a political force into perhaps the eleventh century (Laporte et al. 1994)'

What the texts say of B'ital is that it was a minor foe of Naranjo, by whom it was then defeated (Martin and Grube 2008:97). Iannone (2001:131) contends that the archaeological site of Minanha is ancient B'ital, citing as support for his argument the Caracol-like forms and placement of

Antecedents, Allies, Antagonists 63

architecture, sculpture, and artifacts (especially censer style and use),

as well as a sequence of materially attested events at Minanha that are

consistent with history from the inscriptions. His description ofthe eighthcentury royal compound and its Caracol characteristics were described earlier. In his view, it "is plausible ... that the subsequent 800 AD destruc

tion of these features reflects the wrath of either Naranjo or Caracol, as these powerful centers once again strove to reassert themselves in regional politics. The end result was the elimination of Minanha's ruling 'house,'

and the eradication of those features that were most fundamental to its

identity" (Iannone 2001:131-132). Certainly Xunantunich underwent dramatic and rapid retrenchment

in this period, as is described at length in later chapters. Its subject populace, too, diminished in size and in the complexity of social hierarchy

they could or would sustain. Other sectors of the farming populace, as at Barton Ramie, seem to have been more resilient, however, as were some centers, like Cahal Pech and Baking Pot-many of them having stood as

foci for ritual and governance for fifteen hundred years or more.

Aftermath (ca. AD 890-???)

There is evidence from artifacts to suggest that Minanha persisted for an undetermined period into Postclassic times (Iannone, Connell, and Men

zies 2001:1), and places like Tipu continued to fulfill key roles and func

tions for a greatly reduced subject public over a correspondingly patchy

settlement landscape (Aimers 2004; Ba111987; Bullard 1973; Connell 2003; Graham, Jones, and Kautz 1985; Connell, chapter 13)' But many others, such as Pacbitun, Buenavista del Cayo, and Arenal, had ceased substantial occupation, let alone new construction, within the tenth century or

shortly thereafter (Ball and Taschek 2004:163; Healy 1990; Taschek and Ball 1999:22<)-231). Much of the earlier vibrancy ofpolitical ritual, intrigue, and extended social negotiation was replaced by largely empty monumental centers, visited by the occasional pilgrim leaving offerings or other scant

traces of human presence among tlle ruins (Schmidt 1976-77; cf. Hammond and Bobo 1994)' When the Spanish sought locations for proselytizing and to found visita churches, the local place they chose-Tipu-was but a small remnant of the once extensive and complex society of the region

(Jones 1989; Pendergast, Jones, and Graham 1993).

64 WENDY ASHMORE

Conclusion

TIle record of human occupation in this part of the Maya lowlands is a richly textured tapestry of lives lived, choices made, and consequences met. Whether their identities were as farmers, kings, or something else, the people of the region left material traces of many strategies of incorporation as well as of reactions to how others' strategies affected them. It seems abundantly clear that the emergence ofXunantunich as a new political, economic, and social force had significant impact on existing people and strategies, in many places and in many forms. At the same time, Xunantunich was itself shaped inexorably by the diverse participants already active across the region. This chapter provides simply a working backdrop against which to consider the data and interpretations the Xunantunich Archaeological Project has assembled about the provincial polity ofXunantunich.

Acknowledgments

I thank Richard Leventhal for inviting me into the Xunantunich Archaeological Project investigations in the first place, and Lisa LeCount and Jason Yaeger for encouraging my preparation of this chapter. I am grateful to Tom Patterson, Jason Yaeger, Lisa LeCount, and two anonymous reviewers for thoughtful comments.