An evolutionary perspective on the development and assessment of the national estuary program

Transcript of An evolutionary perspective on the development and assessment of the national estuary program

Coastal lvfanagement; Volume 20, pp. 311-341

Printed in the UK. AH rights reserved.

0892-0753/92 $3.00 + .00

Copyright © 1992 Taylor & Francis

An Evolutionary Perspective on the Development and Assessment of the National Estuary Program

MARK T. IMPERIAL

State of Rhode Island

Coastal Resources Management Council

Wakefield, RI 02879

DONALD ROBADUE, JR.

Coastal Resources Center

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, RI 02881

TIMOTHY M . HENNESSEY

Department of Political Science

University of Rhode Island

Kingston, RI 02881

Abstract This article addresses the U.S. approach to managing environmental quality in estuarine regions. ft reviews the progress that has been achieved in managing coastal environmental quality and looks at the factors that have affected the design of coastal and estuarine management programs by examining five experiences in environmental management that have been important influences on the development of the National Estuary Program (NEP): the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC); the federal river basin commissions; the Section 208 area-wide waste treatment planning; the federal coastal zone management program; and the Chesapeake Bay Program. These programs offer important strengths and weaknesses as models for managing estuarine environmental quality. The authors propose evaluation criteria based on the strategy, structure, and process of coastal environmental programs, which can be used to evaluate the structure and management process of contemporary coastal environmental programs such as the National Estuary Program, as well as to assess their contributions to the evolving field of coastal environmental management.

Keywords Coastal management, environmental management, environmental planning, estuary management, governance, and water quality management

Introduction

The National Estuary Program (NEP) is the latest in a long series of federal environmen

tal planning initiatives aimed at protecting and enhancing water quality and the coastal

environment of estuaries. There are five primary environmental management experiences for estuarine regions that have been important to the development of the NEP's

management process: the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), the federal river

basin planning program under the 1965 Water Resources Planning Act (WRPA), the

311

312 M. T. Imperial et al.

Section 208 area-wide waste treatment planning done pursuant to the 1972 Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments (hereafter Clean Water Act), the formulation of coastal zone management programs in response to the 1972 Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA), and the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP). These five programs represent the major estuarine and coastal management experience in the United States during the last 25 years. These programs, as well as contemporary financial and political constraints, have influenced the design of the NEP.

A historical perspective in program analysis is useful in understanding the NEP's design and innovative nature and in illustrating the advances in estuarine water quality management it is intended to achieve. This article will examine the strengths, weaknesses, and influences that these five experiences in basinwide planning and protection of coastal water quality have had on the NEP. This historical perspective will help to assess the NEP's contribution to coastal environmental management as well as its strengths and weaknesses as a model for future estuarine management initiatives. It will also provide criteria for the evaluation of the NEP.

Estuary Protection as a National Issue

Pollution threatens the ecologic vitality of estuarine systems. Estuaries provide critical habitat for a wide range of commercial and ecologically valuable species of fish, shellfish, birds, and other aquatic and terrestrial wildlife. For example, estuaries in the United States support fisheries whose value to the economy is more than $19 billion annually (EPA 1990b, 1). This accounts for 87 % of the dollar value and 82 % of the weight of finfish harvests in the United States (EPA 1989a, 3). Estuaries also provide aesthetic appeal and recreational value. While many of the aesthetic values are hard to quantify, several recreational values have been measured. In addition, in 1982, almost $5 billion was spent by federal, state, and local agencies to provide recreational opportunities in coastal areas (Calio 1987, 9). In 1984 in Florida alone, more than 13 million adults used the state's beaches with related sales estimated at more than $4.5 billion (EPA 1989a, 4).

Stresses on the Nation's Estuaries

A substantial portion of the nation's population resides in and visits the coastal zone, defined as counties entirely or substantially within 50 miles of the coastline. The actual number totals more than 120 million Americans now residing in this area (EPA 1990a; NOAA 1990a; and Edwards 1989). This results in an average population density in coastal counties almost five times greater than in noncoastal counties (EPA 1989a, 5). Projections estimate a continued increase in coastal zone populations such that by 2010, 53.6% of the U.S. population will reside in the coastal zone (Edwards 1989, 237). The effects of this development and human use have often overwhelmed estuaries and their coastal environments.

Success and Failure in Estuarine Protection

Estuaries have long been on governmental agendas with a series of legislative efforts directed at estuarine issues. These efforts have achieved measurable success. Since 1972 progress has been made at federal, state, and local levels in the management of water

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 313

quality and the coastal environment. Over $100 billion has been allocated to construct publicly owned treatment works (POTW s) via the Section 201 construction grants program of the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA) (Goldman 1990, 16). Controls on point sources of water pollution pursuant to the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), such as those for municipal wastewater treatment and industrial plants, have been effective in expanding wastewater treatment and reducing the loadings of conventional pollutants to estuaries (EPA 1990a, 1). A system for the management of dredging activities and wetlands alteration is well established. Twenty-nine of thirty-five possible coastal states and trust territories have prepared comprehensive plans for the management and protection of the coastal zones (NOA A 1990a). In addition, numerous programs have been enacted to manage coastal and offshore fisheries as well as to protect endangered species (Wise 1991 ; and EPA 1990c). The net result of these efforts is that only 72 % of the nation's 26,676 assessed square miles of estuaries are now fully supporting all of their designated uses (EPA 1990d, 50).

Despite these achievements, existing management systems have failed to guard against continued ecologic degradation. 1 It is estimated that an additional $88 billion is needed to meet the current needs of POTWs (EPA 1990a, 3). Wetlands are still being eliminated at alarming rates despite a "no net loss" national policy. In addition, many wetlands have been so degraded by the effects of pollution and other hydrologic modifications that they can no longer perform their ecologic functions as valuable habitats and spawning grounds. Approximately one-third of the nation's estuarine shellfish beds are closed because of pollution or lack of monitoring (NOA A 1991, 6; and EPA 1990a, 4). This is an acute problem in older urbanized estuaries (EPA 1990b, 32). Despite the federal government's success with a technology-based point source pollution control approach, the effects of nonpoint source pollution continue to plague the nation's coastal waters (EPA 1990c; and EPA 1989d).

More evidence is now becoming available that identifies previously suspected problems that pose significant threats to estuarine systems. For example, the effects of toxic contaminants, such as pesticides, PCBs, and heavy metals, have become an increasing concern for coastal areas, where 25% of monitored coastal waters register elevated levels of these toxic substances (EPA 1990d, 103). The contamination of sediments by toxic substances is a growing concern in many states and delays many dredging projects (EPA 1990d, 110; and National Research Council 1985). In addition, the implications of airborne contaminants on estuarine systems continue to be an area of extensive study (CEQ 1990, 358; EPA 1989e; and Great Lakes Water Quality Board 1989).

The fact that many of the problems affecting estuarine systems involve complex issues related to habitat protection, multimedia sources of pollution, and coastal land use planning is also gaining wider recognition. These issues do not readily fit the traditional domain of water pollution control or coastal zone management programs and are not adequately addressed under the present system of environmental protection (EPA 1990b, 1; and Davies 1989b, 4).

Fiscal Constraints on Estuarine Management and Protection

Federal responses to contemporary coastal environmental issues have been tempered by budgetary constraints, most notably major cuts in federal government funding for the state implementation of clean water and coastal management programs. Budgetary deficits at federal, state, and local levels have severely impaired the implementation and operation of water quality management programs .2

314 M. T. Imperial et al.

---- --·-· -··------ --

The National Estuary Program was established to provide federal leadership in dealing with the increasingly complex estuarine issues at a time when states have faced long-term real declines in federal resources to fund environmental management programs (EPA 1990f; and Conservation Foundation 1984). Unlike earlier Clean Water Act planning and construction grant programs or the CZMA, which both promised implementation funds once state plans were approved, the states that seek to join the NEP are promised only five years of planning funds and must develop their own financing strategies.

Changing Focus in EPA's Environmental Management Strategy

Estuary programs also function within a constantly evolving political and administrative system. This system is shaped by economic realities and public concerns. These factors constrain governmental environmental protection efforts. For example, whereas early water pollution control activities were aimed at health and human safety (Capper et al. 1982), today's pollution control activities span an increasing spectrum of concerns.

Over the past 15 years, there has been an increased tendency toward coupling federal guidance with state implementation in the design of environmental protection programs (Welborn 1988). Returning environmental and water pollution control responsibilities to the states has had a major impact on the design and operation of new environmental programs (Lester 1986; and Ingram 1977). Within the EPA, there has been a continued devolution of a wide range of its environmental program activities to the states. This is illustrated by the fact that 68 % of states now have their own approved NPDES systems (GAO 1988, 146), and nearly all states have established revolving loan programs in response to the elimination of the construction grants program (EPA 1990a, 3).

In general then, the EPA has moved toward establishing federal-state partnerships to direct environmental protection efforts. The EPA believes that the continued delegation of responsibilities to the states offers the opportunity to deliver more effective environmental protection by placing decision-making authority closer to those affected by decisions, broadening the availability of resources and support by taking advantage of state advances in staffing and expertise, and reducing the unwarranted duplication of environmental protection efforts (GAO 1988, 145). Many states have also urged the continued delegation of responsibilities because they believe they have a better knowledge of the local environment and dynamics of the regulated community (GAO 1988, 146).

The EPA will continue to use these partnerships to direct environmental protection program activities in the future. "In effect, states will become the day-to-day operating arm of environmental management; EPA will set national policy and standards, while providing to states the research and technical support essential to the undertaking" ( Alm 1984, 3). In light of fiscal problems at the federal level and the continued delegation of water pollution control activities, states can expect more responsibility for protecting coastal lands and water quality. It is within this administrative and political context that the NEP assumes particular significance.

Introduction to the National Estuary Program

In many ways, the National Estuary Program represents the EPA's changing approach to natural resource management. The NEP began in 1985 when Congress appropriated $4 million to study four estuaries, with two more estuaries receiving funding in 1986. The 1987 Water Quality Act (WQA) formally established the NEP and expanded it to include

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 315

six additional estuary programs. This made the NEP a truly national program with clear legislative requirements. In 1990 the NEP was expanded by five more estuary programs and up to three more estuaries may enter the NEP in FY 1993 (Fed. Reg. 1992). Presently there are 17 estuary programs in the NEP, which encompass 14 different state jurisdictions. They include both heavily urbanized and rural watersheds, with several estuary programs that span state boundaries.

The 1987 WQA defined the NEP's primary goals to be the protection and improvement of water quality and the enhancement of living resources. To meet these goals, each estuary program incorporates federal, state, and local governments, the scientific community, and concerned members of the public in a collaborative decision-making

process called the management conference. The management conference combines these participants into a collection of committees. Typically these committees include a highlevel policy committee, a management committee that handles most of the planning and decision-making responsibilities, a local government committee, a scientific and technical advisory committee, and a citizens advisory committee (EPA 1989b, 16-22).

The primary purpose of the management conference is to produce a comprehensive conservation and management plan (CCMP) for the estuary within five years. The CCMP should address three management areas: water and sediment quality management, living resources management, and land use and water resources management (EPA 1990e, 6). The basic planning process consists of a series of federally mandated planning steps that promote basinwide planning, with an emphasis on the identification of priority environmental problems, the cause of these problems, and actions that should be taken to address them. It is important to note that the NEP was not intended to be simply a sophisticated planning exercise, but rather to require specific financial, institutional, and political commitments. Estuary programs are also supposed to utilize the existing management and regulatory systems to implement the provisions of the CCMPs. Thus one of the great challenges to the successful utilization of the management conference process appears to be its successful integration with existing federal, state, and local regulatory programs.

/ An Assessment of Pre-NEP Estuary Management Initiatives

Many of the managerial principles present in the NEP's design are not new; instead they represent a combination of old themes and characteristics from earlier environmental management programs that make the NEP quite different from its predecessors. The following sections contain a review of five programs that have influenced the design of the NEP. The strengths and weaknesses of these programs help to highlight the importance of the National Estuary Program.

The Delaware River Basin Commission Experience

The Delaware River Basin Commission is one of the earliest attempts at managing environmental impacts in an estuary. There is a century-long history of environmental problems and planning initiatives for this coastal region (Roberts 1989; Albert 1988; and Brezina 1988). Many of these experiences, particularly those of the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), have significantly shaped river basin planning and regulatory programs nationwide.

Creation of the DRBC coincided with the federally funded Delaware Estuary Com-

--·------------

316 M. T. Imperial et al.

prehensive Study (DECS) in 1961. The DRBC was established by an interstate compact between the basin states, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, and the federal government, for the express purpose of forming an agency to coordinate, plan, and manage the allocation and development of freshwater supplies in the entire river basin as well as to control pollution (Manko and Ward 1988, 388; and GAO 198la, 8). Membership on the commission is composed of the respective governors and a presidential representative. With few exceptions, decisions are made by majority vote (Hull 1978, 158). The compact has a 100-year initial term of existence.

To discharge its responsibilities, the DRBC was to prepare, adopt, and maintain a comprehensive plan for the management of water and related land resources (Hull 1978, 158). The compact permits the DRBC to plan, construct, finance, develop rates and charges, and operate and maintain projects for the management of water and land resources (Polhemus 1988, 314). Accordingly, the DRBC had considerable power to implement the recommendations of its plans. 3

During the 1960s, the DRBC focused on the progressively worsening water quality problems of the upper estuary (Polhemus 1988, 315). When it was created, the DRBC took over the responsibilities and functions of the Interstate Commission on the Delaware River Basin (INCODEL). INCODEL was established in 1936 and served as an advisory commission to the states. Initially, the DRBC adopted the INCODEL water quality and discharge standards as its own (Martin et al. 1960). Using the recommendations of the Delaware Estuary Comprehensive Study and a computer model, the DRBC formulated higher basinwide water quality standards for segments of the Delaware River and Delaware Bay and incorporated them into its comprehensive plan in 1967 (Hull 1975, 498). These included recreational standards that had not been included by INCODEL (Albert 1988, 103).4

In formulating these standards, the DRBC underwent an extensive process of consultation with citizen and technical advisory committees. The member governors then chose to implement one of the most ambitious of the five scenarios presented to them by the DRBC planners (Ackerman et al. 1974). To meet these standards, the DRBC issued waste load allocations to individual, industrial, and municipal dischargers in 1968. An administrative program was established to handle new dischargers and other changes to the allocation system. Critics of the waste load allocation system stated that it was too expensive and that nitrogenous oxygen-demanding wastes should have been addressed. While these criticisms had technical merit, the DRBC's combination of public participation and technical expertise served as a practical national model for how complex water pollution control problems could be handled in estuaries and river basins (Albert 1988, 104).

The DRBC programs work cooperatively with individual state programs and the federal government. Commission standards are adopted as state standards, and their requirements become part of state and federal discharge permits. The DRBC's planning has been an ongoing process. The comprehensive plan has developed with time and is much broader in scope than the original plan in 1966 (Hull 1978, 159; GAO 1986; and GAO 198la). The DRBC has been a positive force in clean-up activities by shaping major improvements in the Delaware River's water quality, which now is in compliance with current water quality standards. While progress in cleaning up the Delaware River Basin has been successful, much more remains to be done. 5

There are several strengths of the DRBC's experience as a model for water quality improvement. One has been the DRBC's reliance on applied research and evaluations of

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 317

water-body conditions. The DRBC experience also demonstrates the value of possessing a workable computer model to help predict the consequences of various waste load allocations and reductions, and it also shows the advantage of utilizing waste load allocation systems for pollution control. Among its other strengths as a pollution control model is the recognition that water pollution control efforts require bridging jurisdictional boundaries, continuous monitoring of conditions and progress, and the maintaining and updating of the comprehensive plan as more information becomes available.

But the DRBC experience is not without its weaknesses as a model. For example, without the technology-based standards, national permit system, federal construction grants, and enforcement actions, the DRBC's plans of the 1960s would not have been implemented. In practice, the implementation of pollution control policy was determined by federal, state, and local agencies and not the DRBC. Oftentimes the DRBC failed to get states to go beyond the recommendations of the comprehensive plan, which in reality only set basic policies. Another weakness in using the DRBC as a model is that there were major problems related to implementation funding especially in Philadelphia, Camden, and Trenton. However, despite these weaknesses, the DRBC remains one of the important early water quality management programs, and its activities continue to shape pollution control policy in the basin today.

The 1965 Federal River Basin Planning Program

The Water Resources Planning Act (WRPA) of 1965 established the River Basin Planning (RBP) Program. The RBP program was composed of a four-tiered planning system administered at the federal level by the Water Resources Council (WRC). The WRPA provides for the establishment of federal-state river basin commissions at the request of the states and on the recommendation of the WRC. The affected states and federal agencies have representatives on the commissions (Cunha et al. 1977, 97; and Steele 1971, 33).6

The river basin commissions (RBCs) served as the principal agency for the coordination of federal, state, interstate, local, and nongovernmental plans for the development of water and related land resources. Separate river basin commissions were created for regions and subregions to guard against overcentralization in water planning (Gere 1968, 60). The RBCs were intended to develop new approaches and relationships with respect to national water policy. The WRPA encouraged alternative policies to be set forth and required decisions to be made by consensus (Foster 1984, 76). The RBCs were also afforded significant flexibility with respect to the composition of plans.

Of particular interest are RBC activities pursuant to the preparation of comprehensive plans that made a conscious attempt to obtain participation from the local government and the general public at every stage of the planning process (Irland 1976, 260; Nelson 1975, 607). The planning approach assessed a range of alternative methods to meet projected future needs. In addition, the results of the study were based primarily on existing knowledge, were advisory in nature, and were designed to guide actions by private, local, state, and federal interests. They also provided guidance for other federal and state grant-in-aid programs (Irland 1976; and New England River Basin Commission 1975).

Unfortunately these studies were dominated by federal agencies and sought to address issues on the federal agenda that were not necessarily on state or local agendas (Irland 1976, 266). 7 As a result, the public's response to this program was mostly negative. For example, in the case of the Long Island Sound Study, the plan contained

318 M. T. Imperial et al.

some relatively radical proposals that threatened vested interests and commitments. These included restrictions on the placement of major energy facilities and the aesthetic regulation of coastal development. Because of their lack of participation, state agencies wre also critical of the study.

As a result, river basin commissions failed to emerge as the principal coordinators of planning and development of water and related land resources. Useful comprehensive plans were not produced because the underlying concept of river basin planning was poorly defined and other federal and state agencies failed to support plan development and implementation (GAO 198lb, 15). Moreover, the inventory phase was too long and the plan formulation stage too short in the preparation of these plans (Nelson 1975, 611). The lack of implementation power and governmental support further reduced the number of comprehensive plans that were actually adopted (GAO 198lb, 22).

Federal disappointment in the River Basin Planning Program (GAO 1981b) and the opposition of the Reagan administration to centrally funded regional planning led to its abolition by executive order in 1981. However, while few supported the river basin commissions, most endorsed river basin planning as both theoretically and conceptually sound (American Society of Civil Engineers 1985; and GAO 198lb).

The Federal River Basin Planning Effort as a Model

The limited success of the river basin planning efforts weakens its use as a model for coastal and water quality management. But despite this limited success, there are a few strengths of this approach. Like the DRBC, this program took a geographic approach to problem solving and focused on multiple environmental policy issues at a basinwide level. This allowed for considerable flexibility in the content of the comprehensive plans even though they were dominated by federal issues when perhaps a focus on state issues was more appropriate. These programs also made a conscious attempt to incorporate the public into the planning process. ·

Perhaps the most important lessons from the federal river basin planning efforts can be derived from the weaknesses of the process. For example, the recognition that all regulatory actors at both state and federal levels need to be involved in the planning effort did not go far enough to incorporate direct collaboration with implementing agencies. As a result, the comprehensive plans often contained recommendations that were predominantly advisory in nature and often at odds with state policies. Therefore, few of these planning provisions were implemented. Accordingly, important decision-making authority should have been granted to those responsible for the implementation of these plans: state agencies and local governments. This implies that basinwide planning needs to be carried out in conjunction with environmental planning activities at the state and local levels to ensure state support of the comprehensive planning process, as well as regional support of individual state environmental initiatives.

The Section 208 Areawide Waste Treatment Planning Program

The 1970s ushered in a new era in environmental management planning for the protection of the nation's estuaries. New legislation was adopted by Congress that redefined the national approach to protecting and improving coastal water quality. One of the most pervasive set of changes was the 1972 Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments (FWPCAA), known as the Clean Water Act. The Clean Water Act (CWA) contained

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 319

three primary components: The National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), which prohibits the discharge of pollutants into navigable water without a permit; the construction grants program, which provided financing for the construction of municipal waste treatment facilities; and four regional planning programs. It is the review of the areawide waste treatment planning required by Section 208 of the 1972 CWA administered by the EPA that is most relevant.

The Section 208 planning program was important because it coupled water quality planning with the implementation of pollution control permits and municipal construction grants (Lienesch and Emison 1976, 283). These plans were to include the identification of treatment works necessary to meet anticipated municipal and industrial treatment needs over a 20-year period, establish construction priorities for these treatment plants, and a regulatory program to control point and nonpoint sources of pollution, including those resulting from land use activities, identify the agencies necessary to construct, operate, and maintain treatment facilities, and identify the appropriate measures necessary to implement the plan. These measures were to include the economic, environmental, and social impacts, as well as a description of existing state and regulatory programs that would be used to implement the plan (Sales 1979; Wicker 1979; and Dean 1979).

Pursuant to Section 208, state governors were to identify areas with serious pollution problems and to designate an organization capable of carrying out the planning functions. Typically, these organizations were regional planning agencies or councils of local governments (Wilkins 1980, 486). For areas not designated by the governor as critical, the state was to act as the lead planning agency. Thus Section 208 mandated national areawide waste treatment planning. 8

The management system chosen by a state had to demonstrate administrative efficiency, comprehensive and effective capabilities to deal with the relevant environmental, economic, and social problems, equity powers, political accountability to individuals and groups, and political acceptability (Wilkins 1980, 487). It also emphasized coordination and participation among local governments as well as public participation in the development and implementation of management plans (Lienesch and Emison 1976).

Section 208 plans had to be submitted to the governor for certification and approval as well as to the EPA. The state also had to designate one or more water quality management agencies to implement the plan. A wide range of methods have been used in the implementation of Section 208 plans nationwide, from interagency agreements to changes in permit procedures, policy, and decision-making coordination and interagency budget or program reviews (Dean 1979, 292, 295).9

Incentives and sanctions were specifically granted to the EPA to enforce the provisions of Section 208. For example, the EPA could not make any grant for the construction of a municipal treatment facility to any part other than the designated management agency, and only for facilities in conformance with approved plans. Also, NPDES permits had to be issued in conformance with approved plans. These provisions added legitimacy to approved plans and management agencies.

This federally mandated comprehensive water pollution control program was also subject to many political obstacles. Ultimately, the EPA made all of the key decisions under Section 208 (Jungman 1976, 1077). Hence, the program was not favorably received and acted on by many state and local officials. The political sensitivities of local governments toward regional approaches presented significant obstacles to the implementation of many plans. This was particularly evident in states where local governments have significant land use authority (Wilkins 1980, 489, 494).

320 M. T. Imperial et al.

Implementation of Section 208 plans nationwide has not been a success overall. This is not surprising given the lack of support ultimately given to the process by the EPA. In the early months following passage of the act, the EPA virtually ignored Section 208, instead choosing to focus on other provisions it judged to be of greater importance (Jungman 1976, 1048). Delays in funding and administrative guidance also hindered a state's use of this planning process. 10

The Section 208 Experience as a Model

One of the primary strengths of the Section 208 process was the required participation of both the public and municipal governments. This participation helped to accurately identify planning issues. The planning process also addressed multiple sources of pollution, including nonpoint source pollution, and tried to incorporate growth management into the pollution control process. Local capacities for water quality management that had previously been lacking now became important pollution control tools. Finally, Section 208 plans were able to address interjurisdictional coordination and to define implementation responsibilities.

There are also some deficiencies in the Section 208 process that limit its usefulness as a pollution control model for estuaries today. State water quality management agencies did not take the lead in plan preparation. In many cases, the Section 208 plans were often prepared out of sequence and at odds with other 1972 CWA and CZMA plans. Consequently, Section 208 plans often conflicted with other planning initiatives and their usefulness was therefore reduced.

Another weakness of the Section 208 program was the lack of federal support. Financing for the program was inadequate during its formative years, as was federal guidance on how to prepare plans. As a result, states often resisted full participation in the effort. Moreover, Section 208 planning efforts were hindered by the absence of new or complete information on water body conditions and inadequate enforcement power to implementing agencies, especially with respect to coastal land use issues. State coastal management programs, which were being developed at the same time, deferred to the Section 208 process, thus losing the opportunity to place coastal water quality at the center of their program.

Coastal Zone Management Act

In 1972 another federal-state program was created for the management and protection of coastal resources. The 1972 Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA), subsequent amendments, and congressional funding were the impetus for voluntary state-level planning for the wise use and protection of the coastal zone. The CZM program focuses on the development of an integrated approach that remains sensitive to the interactions among resources and their uses (Knecht 1979, 264). While the law's requirements focus on creating state management processes, the CZM program did permit states to address resource-related problems, such as concerns related to economic development, land use, port development, and fisheries management, as well as coastal resource protection. It also was designed to address organizational and managerial process problems (Englander et al. 1977, 219-220).

The CZMA sets no standards and prescribes no intervention technologies comparable in scope to the CWA. Instead, it establishes broad national goals and a process by

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 321

which states, in cooperation with federal officials, could develop specific management objectives for coastal areas. The goals of the CZMA are the preservation, protection, development, and where possible, enhancement of the nation's coastal zone (Section 303(1)). The CZMA is intended to encourage states to exercise full authority over the lands and waters in their coastal zones to ensure their preservation and protection. These voluntary, state-managed programs coordinate resource use activities of public agencies and private actors. The federal role in the CZM program is to provide funding during the planning stage, coordinate plan development, and provide technical expertise so that the states would be eligible for additional implementation grants (Lowry 1985, 291).

Substantive results were expected in several key areas: protection of natural resources, such as wetlands, estuaries, and fish and wildlife; management of coastal development to minimize loss of life and property; providing an orderly process for siting major facilities that gives priority consideration to coastal-dependent uses; participation in the planning of ports and urban waterfront redevelopment; access to the coast for recreation purposes and protection of historic, cultural, and aesthetic resources; and increased governmental cooperation and coordination to achieve greater predictability and efficiency in public decision making (16 USCS § 1452). 11 The CZM program has realized varying degrees of success in all of these areas (Center for Urban and Regional Studies 1991; and Knecht 1979).

The primary incentives for states to join the CZM program were federal funding for planning and implementation of state programs, and the federal consistency provisions. 12

Although controversial, the federal consistency provisions have led to increased state involvement in federal management decisions affecting the coast (Archer and K,,echt 1987, 107). The CZM program also assured state planners of technical support at the federal level to assist their efforts.

The CZMA gave significant flexibility to states to decide how these outcomes were to be achieved. The lack of federal standards allowed for diversity in the composition of state programs (Center for Urban and Regional Studies 1991). 13 However, all workable state programs had to address the major coastal issues, establish policies to deal with them, and provide adequate state statutes, regulations, and other authorities to enforce the provision of the CZM plan (Matuszeski 1985, 270). 14 The principal management tools used by state programs include regulatory permit systems, comprehensive planning, land use designations, land acquisition, negotiation, promotion of desirable coastal development, and federal/state consistency (Healy and Zinn 1985, 301, 302; and Archer 1988). The CZMA also required broad public participation, adequate consideration of federal views, and coordination with local, regional, and interstate planning initiatives.

One of the greatest effects of this federal assistance has been the improved planning capabilities of local governments and improved communication between state and local governments on coastal zone issues (Sorensen 1979, 299).The imposition of new planning requirements on state programs has continued over time. This is well represented by the recent reauthorization of the CZMA (P.L. 101-508), which imposed requirements for states to develop nonpoint source control programs. 15 These new requirements make coastal zone management a dynamic program that continues to evolve to meet society's demands for environmental protection.

The CZM Program as Model

The coastal zone management program has many positive attributes that make it a model for managing estuarine environmental quality. It continues to evolve over time both by

---------i

322 M. T. Imperial et al.

improving its management capacity and by addressing new issues. Federal requirements with respect to specific information and policies have diversified the scope of many state programs and advanced federal objectives for the coastal zone. An interesting factor that makes the CZM program a strong model is the diffusion of innovation and learning that has taken place during the program's development. The national program office has served as a conduit for information so that state programs can benefit from each other's experience, and it provides technical information often lacking at state levels.

The CZM program demonstrates that a highly structured voluntary management process can be designed to achieve broadly defined goals. One key has been to stress collaborative relationships that account for participant learning during program growth. Another key has been to allow states significant flexibility with respect to the organization of their programs, and the selection of problems and of the policies selected to address these problems. It also demonstrates the value of relying on policy statements, instead of plans in their traditional sense, to direct development activities. This is especially true when the policy statements contain measurable standards and can be enforced by the management program. Many state CZM plans also contain exhortative rather than directive language. However, these nonenforceable policies are not subject to a coastal program's federal consistency authority.

An important factor in the success of the coastal zone management program model has been the provision of federal financial support during both planning and implementation. This helped to develop local and state planning capacities. The development of these coastal management programs also tries to incorporate input from other agencies, interest groups, and the general public into the management process. Perhaps the greatest strength of the coastal management program has been its conscious attempt to balance conservation goals with development interests inherent in land use controls. Unlike many earlier coastal environmental management programs that dealt with land use issues, the coastal zone management programs had the authority to implement enforceable policies that balance the interests of both conservation and development.

While the experience of CZM programs in the United States reveals important strengths as a model for managing coastal environmental quality, there are also several limitations on its use. The primary limitation is that, for the most part, the federal coastal zone management program has not addressed fisheries and water quality issues or been coordinated with the regulatory authorities responsible for addressing these issues. Only recently with the 1990 reauthorization of the CZMA have water quality issues begun to be addressed seriously. This reauthorization contains requirements for formation of nonpoint source pollution control plans by federally approved CZM programs.

Another weakness has been the federal evaluation process. Before the 1990 amendments to the CZMA, NOAA never had a sanction other than the decertification of a coastal program available to it. Thus, while the periodic evaluations have been helpful, they have often been superficial and have failed to stimulate state responses to negative findings. Ideally, the changes brought on by the 1990 amendments to the CZMA, which included the allowance of "interim sanctions," will help to strengthen the evaluation process (P. L. 101-508). Another important limitation of this model has been in building an actively involved constituency. Many coastal programs have found it difficult to generate active interest in program activities outside confrontational settings, such as permit hearings. Nonpoint source pollution and program design and implementation generally do not keep a constituency's interest. Finally, unless there is a major shift in federal policy, it is less likely that future coastal environmental planning and manage-

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 323

ment programs will be able to obtain substantial prolonged federal funding during the ~doption and implementation phase of the management program. However, the effectiveness of the CZM program has been amply demonstrated.

The Chesapeake Bay Program

Despite innovative environmental legislation such as the 1972 CZMA and the CWA Congress felt that certain protective measures were necessary in specific areas of national significance. The Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) was created by Congress in _1~75 to d_eal with an interstate body of water that was not adequately addressed by existm_g ~nvi_ronmental legislation. 16 Congress authorized a $25 million five-year study to begm m fis~al year 1976 that required the EPA to assess water quality problems in ~he bay, e_stabhsh a data collection and analysis mechanism, coordinate all activities mvolved m bay res~arch, and make recommendations on ways to improve existing management mechamsms (EPA 1983a, 12-13). At the conclusion of the study in 1983 several reports were published synthesizing the results (for example, EPA 1983a; EPA 1_9~3b; and EPA 1983c). These studies pointed to three key problems: declines in hvmg resources and submerged aquatic vegetation, increased nutrient loadings, and elevated l~vels of_toxi~ contam~nants. The EPA also identified four factors contributing to the bay s detenorat10n: contmued population growth, increased urbanization intensified agricultural activity, and wetlands loss (Hutter 1985 189-190· and EPA '1983b 14-16). ' ' '

. ~h~ findings of the study spurred the Chesapeake Bay states to action. Maryland, Virgmia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, and the EPA signed the 1983 Chesape~ke Bay ~greement (Tripp and Oppenheimer 1988, 425; and Hutter 1985, 192-193). This committed the states to prepare plans for the improvement and protection of the Bay's _water quality and living resources, and established the Chesapeake Executive ~ouncil. Pursua~t to this agreement, the individual states were left to implement corrective _and protective measures that would ensure the improvement of the Bay's water quahty (Barker 1990, 746-747; and Hutter 1985, 195-206).

Through special agreements with the EPA, six additional federal agencies joined the Chesapea~e Bay partnership i~ 1984. These "memorandums of understanding" pledged the ~gencies to go beyond their mandated programs and in some cases to initiate regionspecific efforts to help meet the objectives of the 1983 agreement (Bonner 1988, 113-114). In 1985, Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia and seven federal age~cies examined their programs and produced a Chesapeake Bay Restoration and ~rotection Plan (Chesapeake Executive Council 1985a) that cataloged their goals and illustrated _the commitments that the signatory parties had made to the Chesapeake Bay effort. This plan, as well as the future plans and strategies appended to it remains the basis of~he interstate management plan for the Chesapeake Bay (Bonner 1988, 118).

~ _plannmg and evaluation process was adopted in 1986 to help develop more specific answer~ to key estuarine protection issues. The four steps in this process were: ~he ~stabhshment of water quality, living resource, and habitat objectives; the d~termmat10n of ~ollutant loading levels necessary to meet these objectives; the evaluat10n of the techmcal alternatives that could be used; and the selection and recommendati~n ~f _actions that s~ould be undertaken (Bonner 1988, 117). In 1987, the governor of Virgima and the chairman of the executive council called for a review of the 1983 agreement.

324 M. T. Imperial et al.

The review resulted in the initiation of the Chesapeake Bay Agreement (CBA), which considerably strengthened the substance of the original 1983 document. It contained recommendations for governance; public access; public information, education, and participation; population growth and development; living resources; and water quality. One of the ways the 1983 agreement was strengthened was through the use of numerical commitments. For example, the 1987 CBA commits the states and the District of Columbia to implement basin wide strategies to achieve a 40 % reduction in nitrogen and phosphorus entering the main stem of the Chesapeake Bay by 2000. 17

Individual states have been left to implement the CBA's goals and recommendations as they see fit. Thus there is tremendous diversity with respect to the activities taken pursuant to the agreement (Barker 1990). 18 This flexibility has kept the states committed to voluntary compliance in implementing provisions of the CBA.

This use of consensus decision making in setting priorities, goals, and objectives has also proven important. The EPA has provided some implementation funding to fulfill the provisions of the CBA and the restoration and protection plan. States have also contributed considerable funding to implement specific provisions of the agreement. The willingness of federal agencies to act as partners in the CBP and to cooperate with the terms of the agreement is a significant factor in the strong state commitment to this effort (Hutter 1985).

The CBP as Model

The success of the Chesapeake Bay Program makes it a good model for the management of regional water bodies. It demonstrates the importance of obtaining institutional commitments at both federal and state levels in the management of these resources. It also illustrates the merits of an intergovernmental system that relies heavily on states to determine the method of implementation for a plan based on the use of policy statements. The CBP also shows that a clearly defined role for science in the assessment of key issues and specific water body conditions is important. Research was focused on the causes of specific ecological problems, and coordinated environmental monitoring programs were specifically established to try to evaluate the effectiveness of management actions. Strong, well-planned public education programs have further assisted in building and maintaining long-term public support for the CBP.

In general terms, the CBP has relied on a structured planning process consisting of problem identification, characterization, and phased management processes structured around specific environmental issues. The use of a phased rather than a comprehensive management approach addresses a key limitation in our capacity as humans to deal with complex ecosystemic problems. By attacking problems at simpler levels and progressing to more complex issues, the program maintains credibility and builds public understanding while technical knowledge is itself advanced. This is a major strength of this program. It also allows for error correction through the evaluation and alteration of existing management strategies based on the results of continued scientific study and public opinion.

Like all of the previously studied models, there are weaknesses in applying the Chesapeake Bay approach to managing other estuarine systems. The reliance on states for implementation may not be feasible in all circumstances because of significant costs associated with implementing some of the policies. In addition, the lack of specificity in some of the broad policy statement that enabled the CBP to gain political support could be construed as a weakness during the implementation phase because of the lack of clear standards or

I Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 325

objectives. Perhaps its major weakness as a model for future programs is the extensive expenditure on scientific studies prior to management action. The level of funding was unrealistic in contemporary, state-led estuarine protection efforts.

Some Lessons Learned from Managing Estuaries

in the United States

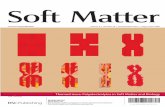

Taken together, these five programs represent the main thrust of the U.S. attempt to protect and manage estuarine waters in the 1970s and 1980s. While these pro?ramsdiffer in their jurisdictional complexity and management process, they all focus on issues that continue to be at the forefront of coastal environmental management. Each program serves as a potential model for designing contemporary coastal environmental protection programs. Accordingly, each program has varying strengths and weaknesses as a present-day model for managing coastal environmental quality (see Figure 1).

Several lessons can be discerned from both the positive and negative aspects of this collective experience. Perhaps the most important lesson is that coastal environmental planning initiatives should have an audience interested in the plan that is produced. Accordingly, the program should plan for implementation. These programs need to have a strategy that includes producing plans that address issues important to the general public and that are politically salient. This is required for obtaining and maintaining political commitments for plan implementation and for working within the contemporary fiscal constraints at federal, state, and local levels.

Another lesson lies in the need for federal support for both planning and implementation. Most programs have been structured so that they receive federal financial and technical support for planning but very little support for the implementation activities that take place after the decision is made to adopt the program. However, it is also important that these programs be given adequate authroity and federal financial assistance for plea implementation. Very often states need federal support during the planning phase to develop both state and local capacities for planning and management. States also need financial support to implement the provision of these plans and to maintain the ability to plan beyond the initial stage.

A third lesson learned is the importance of employing a consensus-based decision-- making process that is collaborative. The successful programs included all of the rele

vant political actors affected by decisions as participants in the decision-making process.Obtaining this consensus on management actions and collaboration during the planningprocess can serve as a bridge to plan implementation by obtaining both the support andcommitment of implementing authorities and the regulated community. It can also createallies and partnerships that could improve institutional coordination.

Many of these lessons, as well as a number of the strengths of prior programs, can be seen in the design of the National Estuary Program. Deriving evaluative criteria from the experience of these five programs allows for an assessment of the NEP on the basis of its contribution to the evolving field of managing coastal environmental quality.

Creating a Model for Managing Coastal Environmental Quality

The collective experience of these programs can be used to identify basic criteria for the evaluation of coastal environmental programs. Many different approaches have been

326 M. T. Imperial et al.

Program Strengths as a Model Weaknesses as a Model

• continuous monitoring of water body • states never went beyond the minimum conditions recommendations of the

Delaware River • use of computer models comprehensive plan Basin • use of waste load allocations • instJHicient power to enforce discharge

Commission • interjurisdictional approach to basin permits under the plan problems • problems with funding implementation

• maintains and updates a comprehensive plan

• involves multiple state and federal • dominated by federal instead of state regulatory actors issues

Federal • flexibility in issues and content of plans • state agencies not directly involved in River • ccnscious attempt at public involvement planning process Basin , tiers uf planning • did not enhance state capacity for

Planning • focused on environmental problems at coastal and water quality planning the basinwide level • recommendations advisory

• no linkage of planning and decision-making body to implementing authoriiy

, participation of public and local • state water quality management agencies

governments did not lead plan preparation

• addressed multiple sources of pollution • plans prepared out of sequence with other Section including nonpoint source pollution 1972 CWA and CZMA plans

208 • planning helped enhance lac.al capacities • lack of federal support-technical and Planning for water quality management financial

• developed integrated pollution control • absence of new or complete information

work plans for priority issues on water body conditions

• interjurisdictional coordination • inadequate implementation authority • definition of implementing responsibility

• addressed new issues over time • no special attention given to fisheries , diffusion of innovations among coastal and water quality issues

programs • superficial federal evalualions • structured management process with • trouble in building actively involved

broad goals constituencies

Coastal Zone • flexibility in program structure, issues • failed to address problems on basinwide

Management addressed, and management actions or multistate scale

Planning • effectively used policy statements that are

subject to enforcement instead of instead of plans

• public involvement • developed local planning capacities • federal financial support during planning

and implementation • focus on implementation authority for

program approval

• institutional commitments among • lack of specificity in policy statements agencies at federal and state levels • slow progress towards goals

, flexibility in state implementation • extensive expenditures on science • broad policy statements help to gain • voluntary state implementation.

political acceptance • helped influence state coastal program

Chesapeake development Bay Program • explicit role for science in the

management process • expansion into new issues • strong federal support , phased management process with

cycles of planning • strong public involvement and

education

Figure 1 Summary of individual program strengths and weaknesses as models for managing coastal environmental quality.

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 327

taken in the evaluation of coastal environmental quality programs.19

These approaches tend to focus on either the planning process or the outcomes of the program. In this article, the focus is principally on the process of coastal environmental quality programs. None of the criteria proposed assess the actual outcomes or effects of these programs, nor do they address how feedback on the results of the process should be used to modify the basic strategy and structure of management programs. All of the earlier programs reviewed in this article did experience changes to their strategy and structure, most often as a result of being perceived as ineffective by regulators or program participants.

On the basis of the five programs reviewed in this article, 12 criteria have been proposed that help to assess contemporary coastal environmental management programs such as the NEP. These criteria relate specifically to the basic strategy of the program; the functional, administrative, and institutional structure of the program; and the process used to reach and then implement policy choices, especially in terms of openness to public participation, new information, and new policy proposals. It should be noted that these criteria are interrelated. The strategy of the program should influence how it is structured as well as which planning process is utilized. The key is to properly match the program's strategy, structure, and process so that an effective outcome results.

Strategy

The analysis of these five programs reveals four basic criteria related to the strategy of coastal environmental quality programs. These criteria reflect the need to match policy objectives and available resources with political and economic realities. The program should

• Address environmental problems ecologically -focus on the basin (ecologic unit) -cross jurisdictional (state) boundaries if necessary -give greatest attention to issues important to resource users and citizens

• Coordinate and improve existing regulations and planning capacities -increase scope of influence to address critical variables not covered by other

laws -strengthen existing laws -strengthen existing organizations charged with implementation and enforcement

• Involve all appropriate political actors including -federal, state, and local governments -public interest groups, and -private sector organizations

• Temper the ambitions of a program with the reality of constraints and competing interests -work within existing political, economic, and sociocultural constraints -avoid overstretching staff and budget -resist the impulse to be synoptic, remaining flexible and adaptive

Address Environmental Problems Ecologically. Both the DRBC and the river basin planning program focused their efforts at the basin level. Later, this geographic approach to ecological problems was refined by the Chesapeake Bay Program. All three of these programs and especially the efforts of the CBP illustrate the advantages of an

328 M. T. Imperial et al.

approach that spans state boundaries and confronts the problems of the estuarine basin as a whole.

Coordinate and Improve Existing Regulations and Planning Capacities. The system of environmental legislation, regulation, and case law that has emerged since the 1960s remains fragmented and needs integration if it is to be effectively used to solve the problems of geographic regions. One of the primary goals of environmental programs must be to improve existing regulatory mechanisms at federal, state, and local levels. The Section 208, CZM, and Chesapeake Bay programs illustrate the need to design implementation strategies that help coordinate governmental activities. It is also important for programs to help improve the planning capabilities of local and state governments, especially as the federal government continues to delegate increased environmental responsibilities to the states. In addition, programs such as the CZM and Section 208 illustrate the benefits to state and local governments when their planning capabilities are improved.

Involve all Appropriate Political Actors. The Section 208, CZM, and Chesapeake Bay programs all show the advantages of involving the appropriate political actors in the management process. This involvement helps to identify the interests and concerns of implementing agencies and gains support for plan implementation. These programs also demonstrate the potential advantages of involving the public and private interests in the planning process.

Temper the Ambitions of a Program with the Reality of Constraints and Competing Interests. It is essential that coastal environmental quality programs work within the existing political, economic, and sociocultural conditions. It does little good to design a program that produces plans that are not politically salient, carry unbearable financial burdens on implementing authorities, or are unpopular with the citizenry. The federal river basin planning program was eliminated, in part, because it failed to work within existing political and sociocultural constraints. While citizens were becoming aware of particular environmental problems during the late 1960s and the 1970s, river basin planners often chose instead to keep their focus on water resources development. This led to clashes with local residents. As a result, plans were produced that were not coordinated with state efforts. Essentially, the river basin planning program ignored existing political and public opinions and produced plans that were unacceptable to those responsible for plan implementation.

Structure

In addition to the program's strategy, a functional, administrative, and institutional structure is necessary to carry out the planning and decision-making processes. This requires a prescribed set of relationships that, when working well, can ease decision-making and implementation tasks. From the review of these five programs, several criteria can be derived for evaluating the effective program structure.

• Decision makers should be the direct client -citizens' and resource users' input is sought and directly utilized -local leaders are included as decision makers

• Financial assistance for planning is provided right up to the decision point

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 329

• Adequate implementation authority and financing is available to the program to -enforce plan components and -supervise implementation activities

• Planning goes beyond implementation of the first plan

Decision Makers Should Be the Direct Client. It is important that the planning unit be clearly defined and have the flexibility to operate. This allows the programs to address issues that are important politically and socially. It also allows for the exclusion of issues that could block successful completion of the planning process. It is important to structure the planning unit in a manner that helps to coordinate and maximize the availability of planning resources.

The CBP illustrates the advantage of targeting, indeed creating, its own decisionmaking group that was the client for the program output. In the CBP, great emphasis has been placed on keeping local interests close to the decision-making effort and on providing adequate opportunity for citizen and resource user input. Accordingly, these efforts have built and maintained support for program outputs and enabled the individual states to keep implementing management actions.

Financial Assistance for Planning Is Provided Right Up to the Decision Point. The experiences of these programs illustrate the benefits of providing financial and technical assistance up until the key decision points. The issues that coastal environmental programs often address are complex and may require significant changes and modifications to regulatory policies and management systems. They involve technical questions and are often regulated by multiple federal and state agencies. Federal assistance helps states address these issues. In addition, this financial assistance helps to develop state and local capacities for planning and management that will have long-term benefits.

Adequate Implementation Authority and Financing Is Available to the Program. Implementation of a plan's recommendations often poses the greatest challenge for coastal environmental programs. Accordingly, it is essential that clients for the planning process have adequate authority to implement the plans that are produced. This fact was recognized by the CZM program, which linked plan approval to implementation authority. The river "basin planning programs, which contained recommendations that were largely advisory in nature, demonstrate the disadvantage of inadequate implementation authority.

The Section 208 and CZM programs show that federal assistance should extend to the implementation phase. The Section 208 program did not receive strong federal support. Technical assistance was lacking and funding for implementation was cut once a majority of the plans were ready for implementation. Not surprisingly, many states failed to fully implement these plans. On the other hand, the CZM program continues to receive federal support for its implementation activities and demonstrates the advantage of federal support for plan implementation.

Planning Goes Beyond Implementation of the First Plan. Finally, coastal environmental quality programs should be structured to provide for planning beyond the implementation of the original plan. The advantages of this approach have been illustrated by the Chesapeake Bay Program. This allows issues that were left out the original plan to be addressed in the future. It also allows for the preparation of future plans that revise and alter past strategies on the basis of experience and subsequent research. As the effort

330 M. T. Imperial et al.

builds and maintains the support of citizens and public officials, it also becomes possible to address new issues once thought too controversial.

Process

The assessment of these five programs suggests that there are several criteria for the management process of coastal environmental quality programs.

• Clear planning goals and/ or issues that -generate public support/media interests and -provide clear goals for the management process

• Decision making based on consensus so that -those affected by decisions are part of the process, -the planning process serves as a bridge to implementation, and -the program creates allies and partnerships

• A specific role for science to - focus on linking causes to specific problems and -monitor present and future conditions

• Participating organizations learn from the experience through -flexibility in issue selection, -cycles of planning, -ability to share management innovations, and -adaptability of implementation process

Clear Planning Goals and/or Issues. It is important that the planning process have a clear decision point or event. This is evident in the federal approval of state CZM programs, the governor's approval of the DRBC and Section 208 plans, and the federal, as well as state, government approval of the CBP. This single decision point helps to focus the planning process on a clear goal and generate the interest of government officials and the general public.

Decision Making Based on Consensus. Coastal problems often involve contentious issues and numerous political actors. The programs reviewed here all demonstrate, to varying degrees, the value of collaborative or consensus-based decision making processes. Collaborative decision making can serve as a bridge to implementation activities by permitting resource users and regulators to make decision jointly. This broadens the information base for the decision making environment. It also builds constituency support for the plan that is produced.

A Specific Role for Science. One difficult aspect of coastal environmental management is defining the role of science in the management process. Both the DRBC and the CBP illustrate the advantages in using science to link causes to specific environmental problems. This helps establish management priorities, legitimize management actions, and direct protective actions. Thus science can help to select and then elevate issues on political agendas. Science also plays an important role in monitoring both present and future conditions, which allows programs to evaluate the effectiveness of management activities and the progress toward plan objectives.

Participating Organizations Learn from the Experience. Several factors make a coastal or water quality program's decision-making environment conducive to learning. First is

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 331

flexibility in the issues that the planning program will address. This enlarges the pool of management situations addressed by programs and broadens the collective base for experience. It also allows a program to choose issues relevant to its political, economic, and sociocultural conditions.

A second factor that enhances a program's learning environment is the use of cycles of planning. The utility in a cyclic approach to environmental planning, which allows new issues to be addressed over time, has been demonstrated by the CBP. It also allows the program to restructure existing management approaches on the basis of increased scientific understanding and its own practical management experience.

Third, the diffusion of management innovations across programs also facilitates program learning. For example, the CZM program has demonstrated the ability of individual states to learn form each other's experiences, and a few states such as Rhode Island have initiated periodic comprehensive revision to their programs. A similar situation has occurred in the CBP where the individual states have taken different approaches to addressing the same issues and have benefited from each other's mutual experience.

A fourth factor that enhances a program's learning environment is the use of an adaptive process for program implementation. The coastal zone is a dynamic environment both politically and environmentally. An adaptive approach to implementation puts states in a better position to ensure reaching the plan's objectives. It also allows them to learn from their efforts and to adapt their approach on the basis of the implementation experiences observed. An adaptive approach to state implementation has been a considerable strength of the Chesapeake Bay approach. It allowed the individual states to develop their own approaches to the CBA's recommended actions that were politically salient and at the same time advanced the objectives of their existing environmental programs.

Preliminary Application of Criteria to the National Estuary Program

The criteria proposed in this article represent a distillation of past experience and are intended to be applied, for the most part, to current and future coastal environmental programs. Because of the evolutionary nature of coastal environmental management, it would be inappropriate to apply many of these criteria to the earlier programs. For example, one of the criteria requires that a contemporary program coordinate and improve existing regulatory and planning capacities. Applying this criterion to either the CZM or Section 208 programs would be inappropriate. In 1972, there was no existing regulatory system comparable to that of the 1990s and many of these programs created the regulatory systems that current programs should seek to coordinate and improve. Thus the true value of these criteria lies in their application to contemporary coastal environmental management programs such as the NEP.

Together, these criteria provide a firm basis for assessing the design and management process of the National Estuary Program. By focusing on the strategy, structure, and process of a program such as the National Estuary Program, it is possible to assess the effectiveness of its design and determine its usefulness as a model for future coastal environmental programs. While a detailed application of the criteria is beyond the scope of this article, a preliminary application demonstrates their value in assessing the design and process of the NEP.

'"':li i

I

I i: !

I ,

I

332 M. T. Imperial et al.

Preliminary Application of the Strategy Criteria

The strategy of the NEP focuses on addressing ecological problems on a basinwide level for specified estuaries of national significance. When necessary, the estuary programs in the NEP span jurisdictional boundaries. The EPA gives the estuary programs significant flexibility in the selection of planning issues. This provides an opportunity for the individual estuary programs to address and give greatest attention to issues that are important to state agencies, resource users, and the general public. However, because of the flexibility in issues selection, it is not clear at this time whether individual estuary programs have tempered the ambitions of their programs with the realities of existing political, economic, and sociocultural constraints. In some cases, estuary programs may produce comprehensive conservation and management plans (CCMPs) that are beyond a state's capacity to implement.

According to Section 320 of the 1987 Water Quality Act, the individual estuary programs are required to involve all appropriate political actors in the decision-making process. However, at the individual estuary program level there may be instances in which certain interest groups or agencies have not been adequately represented in the estuary program's management conference. For example, two of the early estuary programs, the Narragansett Bay Project and the San Francisco Bay/Delta Estuary Program, did not view the state coastal zone management programs as equal partners at the onset of the planning process. In these instances, the state coastal zone management program was placed on the high level policy committee several years into the planning process.

According to a 1988 memorandum of agreement between the EPA and NOAA, the estuary programs are supposed to implement the recommendations and proposed actions contained in CCMPs through existing regulatory authorities, primarily EPA's water quality and nonpoint source management programs and NOAA's coastal zone management programs. This requires taking the recommended policies and actions contained in the CCMP and incorporating them into existing state and local regulatory programs. Thus the strategy of the NEP does allow the existing regulatory programs to be strengthened if the policies and recommended actions contained in the CCMP are implemented. While an individual estuary program's CCMP has the potential to strengthen existing regulatory programs, it is unclear whether these programs are actually improving existing state agency and local government planning capacities. However, as local governments and state agencies transform recommended actions and policies contained in the CCMPs into regulatory program changes, this may very well occur.

Preliminary Application of the Structure Criteria

The activities of individual estuary programs are structured around the management conference, a collection of committees composed of all appropriate public and political actors. To the extent that it involves appropriate representatives from the regulated community and the agencies responsible for the future implementation of recommended policies and actions in the CCMP, the management conference represents the client of the output of the planning process.

To create the CCMP, the NEP is structured to provide financial and technical assistance for planning activities up to the approval of the CCMP. However, unlike many of the early programs discussed in this article, the NEP does not provide any substantive implementation funding at this time. The 1987 Water Quality Act also does not require the continuation of the management conference beyond the approval of the CCMP. This

Evolutionary Perspective on the NEP 333

structure does not provide the individual estuary programs with financial and technical assistance necessary to continue planning beyond the implementation of the first CCMP and develop the recommended policies and actions into regulatory program changes. The capital-intensive nature of many recommended actions may also make successful state and local government implementation unlikely. In addition, by not requiring the management conference to extend beyond the adoption of the CCMP, the structure of the NEP does not assure that there is an administrative entity responsible for supervising the plan's implementation.

Preliminary Application of the Process Criterion