‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable military forces to protect Rome’s...

Transcript of ‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable military forces to protect Rome’s...

‘All roads lead to Rome’:how did Roman roads enablemilitary forces to protectRome’s territories and allowenemies a direct method ofattack during periods of

rebellion?

Gavin Alexander Green

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Gavin Alexander Green Page 2

Fig. 1. Via Appia.Source: http://www.rome.info/ancient/appian-way/

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Contents

List of Figures............................................................................ pg 3

Abstract ...................................................................................... pg 4

Introduction ............................................................................... pg 5

I. Origins of Roman Roads ........................................... pg 5

II. Construction Techniques of Roman Roads ............... pg 5

III. Categories of Roman Roads ...................................... pg 6

Methods of Communication ..................................................... pg 8

Roman Roads and Their Effect on the Army......................... pg 9Gavin Alexander Green Page 3

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Case Studies:

I. Third Servile War ...................................................... pg 11I.I – Background ....................................................... pg 11I.II – Rebel Advantage .............................................. pg 11I.III – Roman Response ............................................. pg 13I.IV – Analysis ........................................................... pg 15

II. The Boudiccan Revolt ............................................... pg 17II.I – Background ...................................................... pg 17II.II – Rebel Advantage............................................. pg 18

Gavin Alexander Green Page 4

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

II.III – Roman Response ........................................... pg 21II.IV – Analysis......................................................... pg 22

Conclusion .................................................................................. pg 25

Bibliography ............................................................................... pg 26

List of Figures

Fig 1. Via Appia .................................................................................................................. pg 1

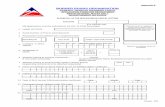

Fig 2. Map displaying Roman frontier provinces and linking Roman road network ........ pg 10

Fig 3. Map showing Rebel and Roman movement during Third Servile War .................. pg 16

Fig 4. Map showing Rebel and Roman movement during Boudiccan Revolt .................. pg 24

Gavin Alexander Green Page 5

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Abstract

Gavin Alexander Green Page 6

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

This dissertation will consider if Roman roads had both a

positive and negative effect on the Roman world in terms of

military engagements. The main thesis will focus on revolts

during which rebel forces utilised the pre-existing Roman road

network and caused substantial destruction to Roman

settlements and disruption to the Roman army. It is a general

consensus that roads provided an advantage to the Roman army

because the structures allowed for a direct route for the

transportation of troops, supplies and news. Contrariwise, I

will argue that Roman roads had a negative effect on

territories during periods of rebellion and made these areas

more vulnerable to attack.

The first matter which is examined is how Roman roads were

constructed and if there were any regulations which had to be

adhered to. Primary sources such as the Twelve Tables (7) from

the fifth century BC, writings by Siculus Flaccus and extracts

from Roman laws (Digest) have all been studied and help the

clarification of road types and the methods of their

construction. Secondary sources, such as articles and books,

are useful as they either back-up or contradict the

information provided by primary sources and this gives my

argument more balance. The method by which roads helped with

the diffusion of news and communications shall also be

considered, as well as how they affected the Roman army.

Gavin Alexander Green Page 7

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

The main body of my discussion will consist of two case

studies in which rebels utilised the established Roman road

network. To counter-balance this debate I shall also record

how the Roman army used the roads to their advantage so that

they could minimise the destruction of the territory. The

first case study will analyse the Third Servile War whilst the

second will evaluate the Boudiccan Revolt. Both rebellions

occurred in specific provinces and created panic amongst the

citizens due to the swift movements of enemy troops and the

apparent difficulty in stopping the revolt.

Introduction

I - Origins of Roads:

Historians will never discover the exact date when humans

first began constructing roads but it is feasible to suggest

that their origins may be early track-ways created by animal

movements and migrations. Early hunters employed their

impressive tracking skills when hunting animals and would have

learnt the routes along which specific species travelled.1

Chevallier (1989) reinforces this theory when he comments that1 Morgan, T. & Young, J. Animal Tracking Basics. 2007. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books: pg 5

Gavin Alexander Green Page 8

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

due to farming and the domestication of animals there was a

necessity for vehicles to be used without damaging them on

rough terrain and this lead to the creation of roads.2

II - Construction Techniques of Roman Roads:

Praise was given by ancient historians to the Roman road

network. Strabo (mid 1st century BC to early 1st century AD)

admires how the Romans paved rural routes3 whilst Dionysius of

Halicarnassus reiterates these feelings by referring to the

‘extraordinary greatness’ of paved roads.4 The ancient poet

Statius wrote a text praising the Via Domitiana which linked

the towns of Sinuessa and Pozzuoli:

‘The first task here is to trace furrows, ripping up the maze of paths, and then

excavate a deep trench in the ground. The second comprises refilling the trench with

other material to make a foundation for the road build-up. The ground must not

give way nor must bedrock or base be at all unreliable when the paving stones are

trodden. Next the road metalling is held in place on both sides by kerbing and

numerous wedges. How numerous the squads working together! Some are cutting

down woodland and clearing the higher ground, others are using tools to smooth

outcrops of rock and plane great beams. There are those binding stones and

consolidating the material with burnt lime and volcanic tufa. Others again are

2 Chevallier, R. Roman Roads. 1989. London: B.T. Batsford LTD: pg 11-123 Strabo. Geography. Jones, H. L. (Trans.) 1932. Harvard University Press. Book V. Chapter III.84 Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Roman Antiquities. Cary, E. (Trans.) 1950. Harvard University Press. Book III.67.5

Gavin Alexander Green Page 9

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

working hard to dry up hollows that keep filling the water or are diverting the

smaller streams’5

The poem above undoubtedly demonstrates how a Roman road

should be constructed; however it must be mentioned that the

road in question was set down in the late first century AD and

the Emperor requested that money should not be a hindrance to

the road.6 This route must be considered as the pinnacle of

road building but it should not be seen as the typical method

for building Roman roads. Ray Laurence (1999) suggests that

the text demonstrates a new level of perfection in terms of

road construction, however it should not be considered as the

definitive method which the Romans used.7 It is possible to

suggest the method by which the Via Domitiana was constructed

by analysing Duval’s commentary. Firstly, the road was marked

out by furrows and the road trench dug to reach the bedrock,

or at least a sufficiently firm foundation. This trench was

reinforced by ramming, piles, or brushwood and sections were

built at a time as with modern motorway construction. The

trench was packed with materials such as stones, gravel and

sand whilst the spine of the road cambered to aid drainage.

Finally the surface was covered with paving stones and wedged-

shaped stones acted as clamps to hold the structure securely.

What is evident is that many different trades were involved in

5 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 836 Jones, B. W. The Emperor Domitian. 1992. London: Routledge: pg 727 Laurence, R. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. 1999. London: Routledge: pg 65

Gavin Alexander Green Page 10

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

road construction, such as woodcutters, quarrymen, carpenters

and stonemasons.8

III - Categories of Roman Roads:

Just like modern highways there were different definitions

given to the various Roman road types. To begin with there is

an apparent differentiation between the types of roads in

relation to their nature.9 For a route to be considered a road

or via it had to be wide enough for a vehicle to move along

it.10 When the route did not allow for a vehicle to travel down

it, due to its width, it was defined as an actus and must be of

a width to allow a pack animal to use it. If the route was any

narrower it was classed as a semita or iter which translates as

path or right of way.11 The width of a via was specified and it

was first noted in the Twelve Tables which records they must

be eight feet wide, along straight sections, and sixteen feet

wide where they went round a bend.12

In terms of via they can be subcategorised further which

demonstrates how the road was used and which individual, or

group of individuals, had the responsibility to manage its

surface. Siculus Flaccus writes that there were three

different types of roads: public roads (viae publicae), the local

8 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 839 Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 5810 The Digest of Roman Law. Book VIII.1.13; Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 5811 Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 5812 Twelve Tables 7; Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 58

Gavin Alexander Green Page 11

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

roads (viae vicinales) and private or estate roads (viae privatae).13

The viae publicae were public highways and it is generally

accepted that they were constructed by the government who paid

all the costs.14 These roads would have been of the highest

quality because they were built for the benefit of the Romans.

The Via Domitiana would have fallen under this particular sub-

category.

Viae vicinales are described as being local roads which are public

but maintained by local communities. These routes tended to

cut across the countryside and linked neighbouring highways

with towns and villages. As already mentioned local

communities (pagi) tended to look after these routes and it was

their responsibility to make sure landowners provided the

workforce or that the landowner was responsible for the

section of the road which crossed over their property. Viae

privatae are private roads which would have linked viae vicinales

with farms and estates. These would have been the

responsibility of the landowner who built the road and who

would have paid all the costs in relation to its construction

and maintenance.15

13 Siculus Flaccus, 146L; Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 5914 Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 5915 Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 60-61

Gavin Alexander Green Page 12

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Methods of Communication

At its peak the Roman road network consisted of over 120,000

kilometres and would have linked every strategically important

settlement in the Roman world.16 These roads provided a method

by which news could be transmitted long distances and at

relatively fast speeds. The utilisation of messengers is an

important aspect of communication and it is not surprising

that every empire of the past set up a system of messengers

for political and administrative reasons.17 The Emperor

Augustus created the Cursus Publicus which was an attempt to make

the diffusion of news swifter and more effective. On his

16 Quilici, L. Land Transport, Part I: Roads and Bridges. In Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. Oleson, J. P. (ed). 2008. Oxford: Oxford University Press: pg 55117 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 181 – the Persian Empire made messengers part of thearmy and are said to have sent horsemen along the Royal roads through the day and night

Gavin Alexander Green Page 13

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

personal letters Augustus first used a sphinx as a seal, then

the head of Alexander the Great, and finally his own head cut

by Dioscorides.18 The Cursus Publicus consisted of relay-stations

(mutationes) and resting-stations (mansiones) which housed

grooms, veterinarians, and anything else which was deemed

useful to the system.19 After the age of Augustus this method

evolved to become a civil-service matter where freedmen were

sometimes responsible for vehicles.20 The purpose of this

system was to make official government travel possible via the

utilisation of the high speeds allowed by the Roman road

network.21

In the modern world the speed of news transmission can happen

instantaneously due to telephones and the internet, however

during antiquity it depended on the speed which individuals

travelled. The most important news would have been transmitted

the fastest and most likely by the method of relay messengers,

whilst merchants may have been coaxed for news on entering a

new settlement.22 Julius Caesar was said to have sent a letter

to the Senate of which it travelled approximately 270 miles in

18 Suetonius. Lives of the Caesars. Edwards, C (Trans) 2008. New York: Oxford University Press Inc: Book II.50 19 Silverstein, A. J. Postal Systems in the Pre-Modern Islamic World. 2007. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: pg 3120 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 182-3 – the careers of messengers was gradually recognised due to their importance to the state21 Kolb, A. Transport and Communication in the Roman State: the Cursus Publicus. In Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire. Adams, C. & Laurence, R. (eds.) 2001. pp. 95-105:pg 102-10322 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 192

Gavin Alexander Green Page 14

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

three days23 whilst the news of the defeat at Aquileia was

transmitted to Rome after four days taking 130 to 140 Roman

miles per day.24 The timescales mentioned by ancient authors

are obviously at the extreme end of the scale because they

record crucially important events and there is a tendency for

ancient sources to exaggerate numbers. This fact should not

cloud our opinion on the reliability of the information

because it is clear that Roman roads helped to reduce the

amount of time that news took to be transmitted.

Roman Roads and Their Effect on theArmy

Roads had a substantial effect on military manoeuvres. With

their ability to unify a geographically divided landscape

Roman roads enabled the army to travel greater distances at

faster speeds.25 These structures gave the Roman army an

advantage in terms of the speed by which they could manoeuvre

from one location to another. The normal speed of the Roman

army has been recorded to be between thirty and thirty-five

miles per day whilst on the march,26 however if an army was23 Appian. Civil War. 1996. London: Penguin Books Ltd: Book II.3224 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 19325 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 203 ; Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 19726 Polybius. The Histories. 2010. Cambridge: Harvard University Press: Book II.25 ; Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 82

Gavin Alexander Green Page 15

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

laden with booty it could barely make five miles per day.27 If

a general determined to make a faster pace with the army he

could remove its equipment. Julius Caesar lightened the load

of four legions so that they could travel a return journey of

seventy-five kilometres in less than thirty hours.28

Roads also provided direct access to strategically important

locations and this was vital during periods of violence and

civil unrest. The ability for the Roman army to swiftly put

down rebellions and move against invading armies meant that

the Roman world could survive against these threats. During

the Later Roman Empire the importance of the road network,

especially in the frontier provinces, is evident when

Diocletian reformed the army to cope with barbarian

incursions. The creation and differentiation between comitatus

and limitanei displays a clear utilisation of the road network

which helped the army defeat invading armies. Comitatus were

heavy troops who were stationed along the frontiers in

established forts and garrisons whilst limitanei were positioned

behind the frontier zone. Limitanei were units who could

mobilise rapidly and effectively manoeuvre to regions which

needed military assistance. The limitanei would have exploited

the existing road network in the frontier provinces to allow

for a swifter movement of troops (Fig 2).29

27 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 19428 Caesar, The Gallic War. Hammond, C. (Trans) 2008. New York: Oxford University Press:Book VII.4129 Christie, N. The Fall of the Western Roman Empire: an Archaeological & Historical Perspective. 2011. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC: pg 54-55

Gavin Alexander Green Page 16

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Case StudiesGavin Alexander Green Page 17

Fig 2. Map displaying Roman frontierprovinces and linking Roman road network.

Source: Cornell, T. & Matthews, J. Atlas of theRoman World. 2006. London: Angus Books Ltd,

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

I – Third Servile War:

I.I – Background:

The Third Servile War was recorded by Plutarch and Appian but

it is only because of modern novels and films that the name

‘Spartacus’ is remembered.30 The origins of the rebellion lay

with a gladiator school in Capua, an area which was owned by

Lentulus Batiatus and was populated mainly by Gauls and

Thracians. The method by which the gladiators escaped is not

certain because Plutarch (1st century AD) records that two

hundred planned to escape but only seventy-eight were able to

obtain cleavers and spits from the kitchen and overpower the

guards.31 Appian (2nd century AD) on the other hand writes that

seventy gladiators decided to escape and overpowered the

guards but only acquired weapons, such as daggers and clubs,

when they stole them from travellers on the roads.32 In

Appian’s case it appears he is attempting to portray the

gladiators as barbarians who have to rob individuals on the

streets, whereas Plutarch depicts the rebels as being

opportunistic who understand how to use their surroundings to

their advantage.

30 Baldwin, B. Two Aspects of the Spartacus Slave Revolt. In The Classical Journal. Vol. 62. No. 7. (April). 1967. Northfield: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South:pg 28931 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 1916. Loeb Classical Library: 8.1-8.232 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.116

Gavin Alexander Green Page 18

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

I.II – Rebel Advantage:

After their escape the rebels advanced towards Mount Vesuvius

where they established a camp deep within the undergrowth and

allowed other slaves to join their rebellion.33 The route by

which the gladiators reached the volcano is not mentioned but

it is reasonable to suggest that they travelled along the Via

Popilia. With Appian mentioning that weapons were obtained

from travellers on the roads and since Via Popilia linked

Capua and Rhegium by running past Mount Vesuvius,34 it is

plausible to suggest that the rebels utilised the road network

to escape Capua and its Roman units. By proceeding down an

established road the rebels would have been able to obtain

more weapons and supplies from travellers to aid their fight

against the Romans. We also learn that Spartacus and his

supporters plundered the surrounding countryside35 which would

have been populated by small villages and farms situated

around the volcano and which benefited from the fertile soils

of the region.36

In response to the rebellion, the Senate sent a force under

the command of Gaius Claudius Glaber37 who besieged the rebels

but was routed from the rear. A second force was sent by the

33 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.11634 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 13435 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.11636 Moser, B. Ashen Sky: The Letters of Pliny the Younger on the Eruption of Vesuvius. 2007. J. Paul Getty Museum: pg 937 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.1-9.3 – mentioned as Clodius; Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.116 – mentioned as Varinius Glaber

Gavin Alexander Green Page 19

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Romans to put an end to the revolt. It was led by Publius

Varinus with reinforcements from Cossinius.38 Plutarch

specifically mentions that Spartacus carefully watched the

movements of Cossinius and attacked him when he was bathing

near Salinae. The rebels were able to seize his baggage and

chased him back to his camp where they killed many, including

the general.39 Cossinius’ baggage included supplies intended

for his army as well as personal equipment for the higher

ranking officials.40

From this information it is reasonable to infer that Cossinius

was moving along a local Roman road, possibly the Via Popilia,

and this explains how Spartacus could keep a close eye on his

movements because he knew that this was the route to be taken

by the army. It would have been necessary for the baggage

train to be travelling along a road which was able to sustain

the weight of the wagons and horses.41 This fact reinforces the

suggestion that Cossinius was utilising a Roman road. After

these victories the slaves retreated to a winter camp and

replenished their supplies by ravaging the towns of Nola,

Nuceria, Thurii and Metapontum.42

38 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.439 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.4-9.540 Roth, J. P. The Logistics of the Roman Army at War (264 BC – AD 235). 1998. Leiden & Boston: Brill: pg 7941 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 203 – Roman roads allowed for the transportation of heavy goods, such as supplies, and reduced the damage on vehicles42 Florus. Epitome of Roman History. Watson, J. S. (Trans) 1889: Book II. Chapter XX.

Gavin Alexander Green Page 20

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

It is at this point that the ancient sources differ in their

detailed accounts of the rebellion but in general they only

vary in a small number of facts and it is possible to bring

Plutarch and Appian together to build a clearer account of the

rebellion. Spartacus’ main objective was to lead his

supporters across the Alps to their homelands because he

understood they could not win a war against the Romans;

however a split in ideals occurred when a number of the rebels

wanted to plunder the Italian countryside.43 The force which

decided plunder is mentioned as being German by Plutarch44 and

under the command of Crixus by Appian.45 This band of rebels

was attacked by the consul Gellius when they had separated

themselves from the main body of Spartacus’ army and were in a

vulnerable position.46 The attack took place near Mount

Garganus.47 It is possible to suggest that this engagement took

place along the Via Minucia which ran in close proximity to

Mount Garganus and had origins in Brundisium.48 Gellius

destroyed Crixus’ forces but he could not defeat Spartacus who

was travelling behind the first band of rebels. The governor

of Cisalpine Gaul, Cassius, then met Spartacus’ army as they

were forcing their way towards the Alps, however they could

43 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.5-9.644 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.745 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.11746 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.747 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.11748 Cornell, T. & Matthews, J. Atlas of the Roman World. 2006. London: Angus Books Ltd: pg38

Gavin Alexander Green Page 21

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

not defeat the rebels and narrowly escaped a complete

routing.49

I.III – Roman Response:

After these defeats the Senate ordered Crassus to put an end

to Spartacus and his supporters. The general decided it was

beneficial to take up a position on the borders of Picenum

because he believed that Spartacus would be going through this

territory in order to reach the Alps.50 The strategic

importance of this territory is clear when we consider that it

lay adjacent to the fastest and most direct route out of

Italy. At the northern most part of Picenum was the Via

Aemilia and it would not have been far out of reach when the

rebels emerged from the Apennines.51 This route was a very

important link between the northern settlements and the towns

located in central Italy whilst being a vital trade artery

which followed the course of an ancient Etruscan road.52 The

military importance of the Via Aemilia is emphasised by Livy

(late 1st century BC – early 1st century AD) who records that it

runs through the territory of the Boii and takes the savage

Ligures in the rear whilst linking with the Via Flaminia.53

Crassus presumably knew that if the rebels reached this artery

they could easily utilise it and escape north through the Alps49 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.750 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.151 Cornell & Matthews. Atlas of the Roman World. pg 10 ; Bunson, M. Encyclopaedia of the Roman Empire. 2002. New York: Facts on File Inc: pg 57752 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 13653 Livy. History of Rome. Roberts, C (Trans). 1905. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd: BookXXXIX.2

Gavin Alexander Green Page 22

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

to their native lands. He recognised the urgent necessity to

stop this from happening.

After a small battle with Mummius54 Spartacus moved south

towards Sicily because he realised that he was not strong

enough to conquer Rome whilst Crassus had blocked his escape

route to the north. Spartacus also hoped to escape across the

sea and reignite the slave wars which had consumed the

island.55 Plutarch mentions that the slaves moved towards the

southern coast and occupied the peninsula of Rhegium,56

possibly along the Via Popilia.57 It was only after Cilician

pirates broke a treaty with the rebels that Spartacus

attempted to move his army, however they were confined in the

peninsula after Crassus had built a wall across the isthmus to

prevent them resupplying.58 Appian describes this event

differently59 but the general consensus is that Spartacus moved

his troops south to escape across the sea and Crassus built a

wall to prevent them from escaping north after they were left

stranded at the coast.

54 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.1 – Mummius was order by Crassus to take two legionsand follow the rebels but not engage in any battle or skirmish. He decided to attack and lost many men to the sword and fleeing. He was punished by Crassus and the practice of decimation was used on his troops.55 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.356 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.3-457 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 13458 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.3-459 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.117-118 – Spartacus decided not to march on Rome but escape via the sea to the south. He occupied the mountains around Thurii and took the city whilst preventing precious materials, such as gold and silver, to be bought in but allowed iron and brass. With his army re-equipped he raided the surrounding countryside and won many encounters with the Romans.

Gavin Alexander Green Page 23

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

The fear that Spartacus would march on Rome is apparent after

he escapes Crassus’ wall and moves his army north. Plutarch

specifically records that Crassus was in fear of this event

and was relieved when he found many of the slaves encamped on

a Lucanian lake. The Senate recalled Pompey from Spain and

Lucullus from Thrace which caused Spartacus even greater

stress as he knew he could not win the war.60 In an attempt to

escape the slaves attempted to move to Brundusium and use the

port facilities to cross the sea. For a swift movement to the

harbour town the rebels could travel along the Via Minucia and

Via Appia as these linked the settlement with towns in central

Italy.61 It was only when Spartacus learnt that Lucullus had

arrived in Brundusium, from Greece,62 that he decided to make a

stand and force a final battle with the Romans.63

I.IV – Analysis:

What is apparent from the Third Servile War is that the

rebels, under the command of Spartacus, were able to move up

and down the Italian countryside with relative ease. To begin

with the gladiators from Capua were able to obtain weapons and

supplies with ease from travellers they met on the road

60 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 11.1-261 Cornell & Matthews. Atlas of the Roman World. pg 3862 Chevallier. Roman Roads. pg 132-133 – Brundusium was the main location to embark to Greece and arrive from Greece63 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.120

Gavin Alexander Green Page 24

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

towards Mount Vesuvius.64 It is evident that at the start of

the rebellion there was a utilisation of the Roman road

network, perhaps specifically the Via Popilia, which helped

Spartacus and his followers escape. The Romans were left

vulnerable when Cossinius was ambushed and his baggage seized

with the rebels forcing them back to their camp and killing

many.65 Once again it is reasonable to suggest that the Roman

army was travelling along the Via Popilia and that this was

how the rebels were able to follow Cossinius’ movements so

closely and attack at the most opportune time.

It was the intention of the rebels to escape from Italy

through the Alps to the north66 but after a divide in ideals

the army of slaves, lead by Crixus, was destroyed by the

consul Gellius.67 With Spartacus and his followers moving north

the Romans knew that they must stop any escape from Italy.

Crassus believed it was beneficial to place an army on the

borders of Picenum68 and attempt to prevent the rebels reaching

the Via Aemilia because it lay adjacent to the fastest and

most direct route out of Italy.69 The fear that the rebels

would march on Rome is evident from Crassus’ decision to

blockade them in the peninsula of Rhegium after Spartacus and

64 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.11665 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 9.4-9.566 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.167 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.11768 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.169 Cornell & Matthews. Atlas of the Roman World. pg 10 ; Bunson, M. Encyclopaedia of the Roman Empire. 2002. New York: Facts on File Inc: pg 577

Gavin Alexander Green Page 25

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

his followers were betrayed and left stranded on the southern

coast.70 After the slaves escaped they moved in haste to the

harbour town of Brundusium but when they discovered

reinforcements had arrived at the port a final battle was

imminent. This eventually resulted in the destruction of the

rebel army.71

It is evident from the information mentioned in relation to

the Third Servile War that the Romans were vulnerable when the

rebels, under the command of Spartacus, utilised the road

network to accomplish swift movements across the Italian

countryside. The ability to ambush local Roman units and

understand the best method by which they could escape

demonstrates that they realised the importance of the road

network which had been in place for many decades. Captured

members of the slave army who survived the final battle were

crucified along the Via Appia from Capua to Rome.72 It is

possible to suggest that this was an attempt by the Romans to

demonstrate the significance of the road network to the war,

both its positive and negative factors which attributed to the

rebel advantage and the Romans’ eventual victory.

70 Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 10.3-471 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.12072 Appian. The Civil Wars. 1.120

Gavin Alexander Green Page 26

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

II – The Boudiccan Revolt:

II.I – Background:

Britain had always been a land of uncertainties for the Romans

ever since Julius Caesar attempted to conquer the island in 55

and 54 BC.73 Between Caesar’s invasion attempts and Claudius’73 Caesar, The Gallic War. Book 4 & 5 – Julius Caesar crossed the English Channel late in the season of 55BC but had to return to Gaul, whilst in 54BC he obtained more success and created alliances after defeating native tribes.

Gavin Alexander Green Page 27

Fig 3. Map of Rebel and RomanMovements.

Adapted from Cornell, T. & Matthews, J.

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

subjection of Britain, some hundred years later, the region

was kept under a watchful eye by emperors and generals.74 In

the years following the successful invasion the majority of

the native Britons were oppressed whilst a small minority were

given confiscated money due to their hierarchy and political

malleability.75 The rebellion by Boudicca during AD 60/61/6276

was recorded by several ancient writers and the most complete

accounts were written by Tacitus (late 1st century AD – early

2nd century AD) and Cassius Dio (mid 2nd century AD – mid 3rd

century AD) who relate well with each other, similar to the

ancient sources collation on the Third Servile War.

Animosity towards the Romans had been brewing several years

prior to the rebellion but Tacitus correlates the origin of

the revolt to another event. He records that a power struggle

between the Romans and the Iceni caused the Britons to rise up

against their oppressors. Boudicca’s husband, Prasutagus, was

King of the Iceni and after his death he left his land to both

the Roman Empire and his two daughters. This was an attempt to

place his kingdom out of harm’s way so that it would continue

to prosper under Roman suzerainty, whilst remaining74 Webster, G. The Roman Invasion of Britain. 1980. London: Batsford Academic and Educational Ltd: pg 63 – Augustus considered an expedition but rebellion in Spain prevented this; Suetonius. Lives of the Caesars. IV.44-46 – Caligula was recorded to have taken the surrender from the son of a British king and attempted to invade.75 Cassius Dio, Roman History. Cary, E. & Foster, H. B. (Trans) 1927. London: W. Heinemann: LXII.1-2.76 Carroll, K. K. The Date of Boudicca’s Rebellion. In Britannia, Vol 10. 1979. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: pg 197 – Tacitus places the outbreak ofthe revolt in AD 61 but the belief is he was wrong and it actually occurred in AD 60-61

Gavin Alexander Green Page 28

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

independent.77 The will of Prasutagus is an important event

prior to the rebellion because it has been considered as the

‘official’ reason for Boudicca’s uprising. Braund (1996)

comments that the division of the will is not clear and

Tacitus is usually interpreted to mean that Nero was to

receive half the kingdom with Prasutagus’ daughters inheriting

the other half. Another interpretation refers to Nero being

appointed as guardian of Prasutagus’ daughters or,

alternatively, that he was heir to the region with the

daughters being legatees. The most likely interpretation is

that Nero was to inherit half the region with Prasutagus’

daughters retaining the other half because the Iceni had been

Romanised in some aspects - most notably their coinage - and

Prasutagus would have held Roman citizenship.78

II.II – Rebel Advantage:

Whatever the terms of his will it was not followed through and

Boudicca was flogged and her daughters raped. The Romans also

went further by removing the possessions of the Iceni

chieftains and placing the King’s relatives in slavery. With

the tribe distraught and seeking revenge they gathered others

who wanted to reclaim their freedom, most notably the

Trinovantes, and created a secret conspiracy to remove the

Romans from Britain. The first Roman settlement to be targeted

77 Tacitus Annals. Martin, R. H. & Woodman, A. J. (Trans.) 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: XIV.3178 Braund, D. Ruling Roman Britain: Kings, Queens, Governors and Emperors from Julius Caesar to Agricola.1996. London & New York: pg 133

Gavin Alexander Green Page 29

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

was the veteran colony of Camulodunum (modern Colchester)

which lay south of Iceni territory. Tacitus mentions that the

Britons had the deepest hatred of the veterans in Camulodunum

as they had forced the natives from their homes and called

them slaves. Disgust was also aimed at the temple dedicated to

the deified Claudius in Camulodunum because it was seen as a

stronghold of eternal tyranny.79

With the majority of the Roman army attempting to conquer

Wales, under the command of Suetonius Paullinus, the rebellion

began at the most opportune time. There were smaller groups of

Roman units littering Britain, such as Catus Decianus

(Procurator) and Petilius Cerialis (Legate of the IX Legion).

News of the uprising first reached the veterans in Camulodunum

and they requested help from Catus.80 The route which the rebel

army took from Iceni territory to Camulodunum is not mentioned

but it is possible that they utilised the Pye road which

connected Venta Icenorum and Camulodunum.81 This would have

provided the Britons with a direct and well known route which

they could use to their advantage to spring a surprise attack.

Catus sent two hundred men without full equipment perhaps in

an attempt to allow them to travel faster.82 The veterans

79 Tacitus. Annals. XIV.3180 Tacitus. Annals. XIV.3281 Press Release. The Boudicca Way: pg 2 - http://www.theoldbakery.net/user_files/downloads/boudicca-way-press-release-270810.pdf82 See footnote 28 – Caesar lightened his legions to allow quicker movements

Gavin Alexander Green Page 30

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

utilised the temple of Claudius as a fortification but after a

two day siege the Britons destroyed the settlement.83 The

destruction which occurred was incredible and archaeologists

have discovered the layer, termed the ‘Boudican destruction horizon’,

which demonstrates the carnage which occurred during the siege

and subsequent looting. This stratigraphic layer ranges in

depth between a few centimetres to as much as one meter. The

fires which consumed the colony reached such a great

temperature that molten glass solidified whilst daub, which

normally reverts back to clay, appeared more like pottery in

characteristics.84

With Camulodunum under attack Petilius Cerialis, the Legate of

the IX Legion, led a relief force to help the colony. This

rescue force never reached the settlement because it was

intercepted by rebels and the legions were routed with only

Cerialis and the cavalry escaping to safety.85 The size of the

relief force is debatable with opinions ranging from fifteen

hundred86 to six thousand men.87 Whatever the size it is

apparent that the Romans were ambushed between their base and

Camulodunum. The vulnerability of the Roman army was

demonstrated during the Battle of Teutoburg Forest which

83 Tacitus. Annals. XIV.3284 Sealey, P. R. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. 2004. Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications Ltd: pg 2285 Tacitus. Annals. XIV.3286 Sealey. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. pg 2287 Dudley, D. R. & Webster, G. The Rebellion of Boudicca. 1962. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd: pg 62

Gavin Alexander Green Page 31

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

resulted in three legions being destroyed.88 The location of

the ambush is also debatable because it is not mentioned in

any ancient source so scholars have made educated guesses on

the possible setting. Webster (1978) has calculated that the

ambush may have taken place approximately twenty to thirty

miles from Camulodunum in wooded country;89 however in an

earlier book he is more specific and places it between Water

Newton (Durobrivae) and Godmanchester (Durovigutum) along the

road to Camulodunum.90

After the meticulous looting of Camulodunum91 the rebels made

their way towards the market town of Londinium. This settlement

was not a colony92 so the Britons were not intent on killing

veterans who had oppressed natives. Instead they were

attacking a city populated with both natives and foreigners

who primarily functioned as merchants.93 Merrifield (1983) has

compared Roman Londinium in AD 60 favourably with modern London

in respect of the large number of merchants who imported and

exported on a large scale. He also mentions that the

transactions were of a significant level due to the language

88 Tucker, S. C. Battles That Changed History. 2011. California: ABC-CLIO: pg 75 – TheGermanic tribes planned the ambush as they had knowledge of the route the Romanswould utilise.89 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. 1978. London: B. T. Batsford Ltd: pg9190 Dudley & Webster. The Rebellion of Boudicca. pg 6291 Sealey. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. pg 25-26 – no gold or silver has been found in the burnt layers apart from the odd Roman coin92 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 33 – Tacitus records that Londinium was not distinguished by the title of colony.93 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 33

Gavin Alexander Green Page 32

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

used by Tacitus when describing the city.94 It is therefore

plausible to suggest that the rebels utilised the Roman road

which linked Camulodunum and Londinium as it provided another

direct and swift method of attack.

When news reached Suetonius he took the decision to make haste

to Londinium with his cavalry so that he could assess the

situation. He made his way undaunted through the midst of the

enemy and this terminology suggests that the province was

still hostile. On arrival he gave orders to abandon the

settlement in a bid to save the whole province.95 The speed at

which Suetonius travelled is difficult to calculate although

it may have taken him three or four days hard riding. The

distance from Mona to Londinium is approximately two hundred

and fifty miles but if he sailed by fast galley to Chester he

could have reduced his overland travel to one hundred and

eighty miles.96 The location of Londinium in a key position at

the lowest bridging point of the Thames and at the hub of the

new Roman trunk road network made the settlement easy to

access.97

The destruction of Londinium had parallels with Camulodunum and

demonstrates a systematic attack on the settlement. A layer of

94 Merrifield, R. London: City of the Romans. 1983. Berkeley & Los Angeles: pg 41-42 – He argues that Tacitus uses the word negotiatores instead of the more commoner mercatores when mentioning the trade transactions which occurred in Londinium.95 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 3396 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. pg 9397 Sealey. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. pg 30

Gavin Alexander Green Page 33

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

bright red burnt daub has been uncovered ranging from thirty

to sixty centimetres in depth whilst burnt debris had

accumulated in open pits to make it as much as one and a half

meters deep. Once again meticulous looting is apparent but it

is noticeable that the rebels missed some booty such as a

cache of four sealstones concealed in a pot at Eastcheap.98

With Londinium destroyed Boudicca moved her force towards

Verulamium because it was rich with plunder and was

unprotected. The most direct route between the two settlements

was along Watling Street and Sealey (2004) proposes that the

rebels utilised this military road.99

The Boudican destruction horizon in Verulamium reached a maximum of

fifty centimetres and consisted of the same red daub and ash

found at Londinium. Not all of the settlement was

systematically razed to the ground but there is evidence for

intensive looting in areas of devastation.100 Webster writes

that Verulamium suffered because of its strong pro-Roman

sentiments after being awarded the status of municipium101 and

obtaining an element of self-government.102 It would have not

been a coincidence that this settlement was attacked when we

consider its location along Watling Street which provided a

direct link from the previously sacked sites.

98 Sealey. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. pg 3399 Sealey. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. pg 34100 Sealey. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. pg 37 – buildings in Insula XIV survived whilst a lack of precious possessions have been excavated in the destruction debris101 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 33102 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. pg 96

Gavin Alexander Green Page 34

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

II.III – Roman Response:

Up to seventy thousand citizens and provincials fell in the

three settlements103 but scholars suggest that this is an over-

exaggeration by Tacitus. Some place the figure at half the

number recorded104 whilst others suggest if we include all the

areas which could have been attacked by Boudicca, Tacitus’

figure may not be so difficult to comprehend.105 With the

destruction of three Roman settlements the tide now turned

against the Britons with Suetonius joining his infantry who

were marching along Watling Street.106 The location of the

final battle between Boudicca and Suetonius Paulinus has been

a fascination for archaeologists and ancient historians but

there is no concrete evidence to support any theory put

forward by scholars.107 Webster suggests that Mancetter is a

possible location for the battle as it is similar to the

description mentioned by Tacitus. This setting is based on the

fact that Suetonius would have moved back up Watling Street in

order to meet his infantry at a pre-planned location. The

Romans would then have needed to head back down Watling

Street, towards Verulamium and Londinium, so that they could

103 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 33104 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. pg 96 – Webster writes that it is difficult to believe that the total population of the three settlements was in excess of eighty thousand and that half that amount would still seem excessive.105 Dudley & Webster. The Rebellion of Boudicca. pg 69 – Dudley and Webster mention that if we include pro-Romans in isolated farms, along with the populations of the threesettlements, then Tacitus’ figure may not be so wild.106 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 34107 Hingley, R. & Unwin, C. Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. In British Archaeology, Issue 83. July/August. 2005. Hambledon & London: Features

Gavin Alexander Green Page 35

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

force a pitched battle against the rebels.108 The Britons could

have been attempting to attack another Roman settlement which

is why they were travelling along Watling Street. The military

road would have provided them with a direct route to another

strategically important Roman settlement, but instead of

meeting a town they encountered Suetonius and his army.

The fear of being ambushed en-route is demonstrated by Poenius

Postumius. He did not follow the orders of Suetonius and

remained in south-west Britain acting as the Camp Prefect of

the II Legion. He was instructed to lead his troops to a

rendezvous point so that a combined Roman army could force a

battle with the rebels.109 To the dismay of Suetonius, Poenius

did not meet at the rendezvous point and it is suggested that

he was afraid of being ambushed in the same manner as Petilius

Cerialis.110 Webster also comments that he could have been

pinned down in his fortress by the Durotriges as they may have

joined Boudicca’s revolt.111 It is my opinion that Poenius

decided not to join Suetonius because of the high possibility

of an ambush on his forces. News would have reached him about

the rebellion and the destruction of Petilius as they

attempted to release Camulodunum from siege. Evidence that

news was passed on from military garrisons is apparent when we

108 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. pg 97109 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 37110 Dudley & Webster. The Rebellion of Boudicca. pg 63-64 111 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. pg 95

Gavin Alexander Green Page 36

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

consider that messengers travelled using relays or

individually at high speed.112

II.IV – Analysis:

It is clear from the Boudiccan revolt that the Britons

utilised the established Roman road network. They were able to

move swiftly through Roman territory and destroy the

settlements of Camulodunum, Londinium and Verulamium.113 The

rebellion began at the most optimum time when the majority of

the Roman army was campaigning two hundred miles away and they

were able to ambush a relief force led by Petilius Cerialis.114

It is also apparent that the Romans knew they were vulnerable

when moving through hostile territory, especially when

travelling down an established Roman road, and Poenius

Postumius demonstrates this when he does not follow his

commander’s orders and remains in his fortifications.115 The

swift movements of Boudicca and her army must be attributed to

the roads which linked the aforementioned settlements because

the structures provided a swift and direct method of attack.

What is also evident is that the established road network

helped the Roman army manoeuvre their forces quickly and

effectively through the countryside. If Suetonius Paulinus had

not been able to gather his troops and forced march to

confront Boudicca then the rebellion could have engulfed other112 Laurence. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change. pg 81113 Cassius Dio, Roman History. Cary, E. & Foster, H. B. (Trans) 1927. London: W. Heinemann: LXII.7-8114 Tacitus. Annals. XIV.32115 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 37

Gavin Alexander Green Page 37

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

tribes. The utilisation of the road network as a form of

communication is evident when we consider that Paulinus heard

about the revolt and made sure that the Roman forces should

mobilise against the rebels.116 The ability to also understand

the movements of the rebel army is noticeable as the final

battle is mentioned to have occurred along Watling Street as

Suetonius moved south-east and Boudicca moved north-west.117

The Boudiccan Revolt was aided by the established Roman road

network which enabled the rebels to wreak carnage in and the

destruction of three important settlements. The capability for

the rebels to attack Roman settlements with alacrity must be

attributed to the road system which provided a direct link to

Camulodunum, Londinium and Verulamium.118 The vulnerability of

the Roman army to be ambushed is demonstrated by the attack on

Petilius Cerialis119 and the decision of Poenius Postumius to

remain in his fortification.120 The advantage of being able to

use constructed roads by the Roman army is apparent with the

swift movements by Suetonius and the ability to communicate

with other Roman units so that they could put an end to the

rebellion spearheaded by Boudicca.121 What is clear is that

116 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 37 – Paulinus sent orders to Poenius to mobilise and force march to a pre-set rendezvous point ; Tacitus. Annals. XIV.32 – help was requested by the inhabitants of Camulodunum to Petilius Cerialis when news of the revolt reached the settlement.117 Webster. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. pg 97118 Cassius Dio, Roman History. LXII.7-8119 Tacitus. Annals. XIV.32120 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 37121 See footnote 116 Tacitus. Annals. XIV: 37 ; Tacitus. Annals. XIV.32

Gavin Alexander Green Page 38

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

both factions were able to communicate with relative ease with

their supporters and used the road system to their advantage

when making movements against their enemy.

Gavin Alexander Green Page 39

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Conclusion

The Roman road network played an important part in military

affairs. It is evident that the Romans found it necessary to

Gavin Alexander Green Page 40

Fig 4. Map of Rebel and RomanMovements.

Adapted from Chevallier, R. Roman

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

link potentially strategic settlements, and regions, by road

due to a number of reasons. The ability to transmit news and

other communications at higher speeds is one benefit which was

provided by a well maintained road network. The Cursus Publicus

utilised this network after it was created by the Emperor

Augustus and set the foundation for messengers to become very

important for the running of the Roman Empire. In terms of

military forces, these structures allowed for a faster

movement of troops across longer distances as they provided a

more direct and stable method for manoeuvring. Even though

Roman roads were meant to provide an advantage to Roman

movements, they ultimately gave rebel armies a swifter way of

attacking. For enemies who lived in occupied regions and

encountered the road network, they were able to use the roads

to spring ambushes and attacks on Roman units and settlements.

During periods of rebellion it is apparent that the Roman road

network provided the rebels with a direct method by which they

could attack important settlements. During the Third Servile

War it is noticeable that Spartacus and his followers utilised

the existing road system so that they could escape Capua and

ambush local Roman units. Boudicca and the British rebels used

the road network to a greater extent as they were able to

destroy three Roman settlements before the main body of the

Roman army met with them in battle. It is clear that during

these two rebellions the road network provided both positive

Gavin Alexander Green Page 41

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

and negative effects on the Romans and the rebel armies. The

myth that Roman roads provided Rome with a substantial

advantage against her enemies may not be as transparent as

initially set out.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Appian. The Civil Wars. 1996. London: Penguin Books Ltd

Caesar. The Gallic War. Hammond, C (Trans.) 2008. New York:

Oxford University Press Inc.

Cassius Dio, Roman History. Cary, E. & Foster, H. B.

(Trans) 1927. London: W. Heinemann

Digest of Roman Law

Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Roman Antiquities. Cary, E.

(Trans.) 1950. Harvard University Press

Florus. Epitome of Roman History. Watson, J. S. (Trans) 1889

Gavin Alexander Green Page 42

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Livy. History of Rome. Roberts, C. (Trans). 1905. London: J.

M. Dent & Sons Ltd

Plutarch. The Life of Crassus. 1916. Loeb Classical Library

Polybius. The Histories. 2010. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press

Siculus Flaccus, 146L

Strabo. Geography. Jones, H. L. (Trans.) 1932. Harvard

University Press.

Suetonius. Lives of the Caesars. Edwards, C (Trans.) 2008. New

York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Tacitus Annals. Martin, R. H. & Woodman, A. J. (Trans.)

1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The Twelve Tables

Secondary Sources:

Baldwin, B. Two Aspects of the Spartacus Slave Revolt. In

The Classical Journal. Vol. 62. No. 7. (April). 1967. Northfield: The

Classical Association of the Middle West and South, pp.

289-294

Braund, D. Ruling Roman Britain: Kings, Queens, Governors and Emperors

from Julius Caesar to Agricola. 1996. London & New York.

Bunson, M. Encyclopaedia of the Roman Empire. 2002. New York:

Facts on File Inc:

Gavin Alexander Green Page 43

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Carroll, K. K. The Date of Boudicca’s Rebellion. In

Britannia, Vol 10. 1979. London: Society for the Promotion of

Roman Studies, pp 197-202

Chevallier, R. Roman Roads. 1989. London: B.T. Batsford LTD

Christie, N. The Fall of the Western Roman Empire: an Archaeological &

Historical Perspective. 2011. London: Bloomsbury Publishing

PLC.

Cornell, T. & Matthews, J. Atlas of the Roman World. 2006.

London: Angus Books Ltd

Dudley, D. R. & Webster, G. The Rebellion of Boudicca. 1962.

London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

Hingley, R. & Unwin, C. Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen.

In British Archaeology, Issue 83. July/August. 2005. Hambledon &

London

Jones, B. W. The Emperor Domitian. 1992. London: Routledge

Kolb, A. Transport and Communication in the Roman State:

the Cursus Publicus. In Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire.

Adams, C. & Laurence, R. (eds.) 2001. pp. 95-105

Laurence, R. The Roads of Roman Italy: Mobility and Cultural Change.

1999. London: Routledge

Merrifield, R. London: City of the Romans. 1983. Berkeley & Los

Angeles

Morgan, T. & Young, J. Animal Tracking Basics. 2007.

Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books

Moser, B. Ashen Sky: The Letters of Pliny the Younger on the Eruption of

Vesuvius. 2007. J. Paul Getty Museum

Gavin Alexander Green Page 44

‘All roads lead to Rome’: how did Roman roads enable militaryforces to protect Rome’s territories and allow enemies a

direct method of attack during periods of rebellion?

Quilici, L. Land Transport, Part I: Roads and Bridges. In

Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World.

Oleson, J. P. (ed). 2008. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Roth, J. P. The Logistics of the Roman Army at War (264 BC – AD 235).

1998. Leiden & Boston: Brill

Sealey, P. R. The Boudican Revolt against Rome. 2004.

Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications Ltd

Silverstein, A. J. Postal Systems in the Pre-Modern Islamic World.

2007. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Tucker, S. C. Battles That Changed History. 2011. California:

ABC-CLIO

Webster, G. Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60. 1978.

London: B. T. Batsford Ltd

Webster, G. The Roman Invasion of Britain. 1980. London:

Batsford Academic and Educational Ltd.

Websites:

http://www.rome.info/ancient/appian-way/

http://www.theoldbakery.net/user_files/downloads/

boudicca-way-press-release-270810.pdf

Gavin Alexander Green Page 45