About U and I

Transcript of About U and I

About U and I

Antonio Baroni DISLL-‐ Università degli Studi di Padova

GLOW Phonology Workshop

Brussels, 5 April 2014

A – I – U

• Place or Melody elements in Element Theory (KLV 1985, 1990, Harris 1990, Scheer 1999, Botma 2004, Backley 2011).

• |A| -‐ low vowels, sonorants. • |I| -‐ bright/acute, palatal Cs, front Vs • |U| -‐ dark/grave, labial Cs, back Vs • For some, |@| or |v| -‐ cold/neutral vowel

?, h, N, L, H

• Manner elements • |?| occlusion • |h| fricaYon noise (someYmes subsumed under H)

• |N| nasality (someYmes subsumed under L, e.g. Botma 2006, Botma et al. 2009, Breit 2013)

• |L| voicing, low tone • |H| voicelessness, high tone

Melody vs. Manner

• Place elements pa\ern together • They idenYfy the “color” of Vs and Cs • They can spread • Examples: – PalatalizaYon as I-‐spreading (e.g., LaYn cibu(m) [kibu] > Italian [tʃibo]).

– LabializaYon as U-‐spreading (e.g., Japanese /huta/ > [ɸuta] ‘lid’).

– Lowering as A-‐spreading (e.g., Proto-‐Germanic *sterron > English star)

However…

• Nasality can spread too, – E.g., an > ɑ̃n > ɑ̃

• |A| ooen behaves differently from |I| and |U|

• |I| and |U| display differences too.

|A| as the vocalic element • |A| is more vocalic than |I| and |U| (cf. van der Torre 2003:51, Botma 2004). • |A| and |?| should not combine in the same phonological expression (Scheer

1999:218). • Evidence from the stop series.

U I I U | | | | h h h h | | | | ? ? ? ? [p] [t] [c/tʃ] [k]

Typology of stop series

• Typically, a language has a series of three stops (voiceless/voiced): labial, coronal and dorsal. If there is a fourth stop, it is normally palatal/postalveolar.

• I argue that both labials and velars contain |U| (Backley 2011) and both coronals and palatals contain |I| (Botma 2004, van der Torre 2003).

Velars contain |U| • Contra KLV 1990, Harris 1990. • Contra van der Torre 2003, Botma 2004 (according to whom, velars contain |A|).

• Labial and velar interacYon, similar spectral characterisYcs, cf. Jakobson’s [grave].

• English: x > f, as in laugh. Roumanian: noapte < LaYn nocte(m). Caribbean Spanish: apto = akto [akto].

• Velar-‐labial or labial-‐velar sequences are much rarer than velar-‐coronal, coronal-‐velar, labial-‐coronal, etc. OCP effect?

Coronals contain |I|

• Contra Scheer (1999, 2004). • Coronals and palatals are acousYcally bright. • Fikkert & Levelt (2008): one-‐feature word phase in Dutch children: pop, Mt, kok. An all-‐coronal word has a front vowel.

• InteracYon, e.g., sibilants can only be coronal or palatal, i.e., they contain |I|.

Stops vs. Vowels • |A| shouldn’t combine with |?| so its presence in stops is highly marked.

• Basic stop series should only consist of combinaYon of |I| or |U| with |?|.

• Conversely, |A| belongs to the nuclear posiYon. Every language has at least a low vowel (Jakobson 1941, Greenberg 1966).

• |I| and |U| are less marked in consonantal posiYon, e.g., |I|-‐vowels and |U|-‐vowels typically alternate with glides, low vowels to a much lesser extent (rhoYcs? pharingeals?)

|U| as the consonantal element

• DefecYve stop series. No languages with only |I|-‐stops. – Hawaiian: [p, k] (U-‐stops) but not [t] (I-‐stop) – Xavante: [p] (U-‐stop), [t, c] (I-‐stops) – Wichita: [t] (I-‐stop), [k, kʷ] (U-‐stops).

Place assimilaYon • Dutch: /n/ + /p/ = [mp], /n/ + /k/ = [ŋk], /m/ + /t/ = [mt], /ŋ/ + /t/ = [ŋt].

• It seems to indicate that |U| is fi\er than |I| for the C posiYon. When |I| meets |U|, the la\er prevails. The coronal nasal |A,I| becomes labial |A,U| or velar |A,U| before labial and velar stops, respecYvely.

• The likeliness of velars to undergo palatalizaYon is arguably due to their non-‐headedness (U + I), whereas assimilaYons of the type kt > \ to coda-‐onset effect, e.g., LaYn aktu(m) > Italian aNo.

Vowel epenthesis

• Mostly, some kind of schwa, which is arguably non-‐headed |A| (Backley 2011).

• Otherwise, [ɨ] the colorless vowel, and [i]. • U-‐vowel epenthesis is una\ested (Lombardi 2002), unless it results from the surrounding consonants or copied from another V.

Co-‐occurrence of |I| and |U|

• If |I| is fi\er in a V posiYon and |U| in a C posiYon, it is to be expected that, in languages which avoid the co-‐occurrence of these two primes, |I| is preserved in V at the expense of |U|. – French [y] (consisYng of |I, U|) loses |U| when adapted in Louisiana French-‐based creole, e.g., French plus [ply], occupé [okype] Louisiana Fr. pli [pli], okipé [okipe] (cf. also HaiYan, Guyana, MauriYan, etc.).

– LaYn adaptaYon of Greek words containing [y]: y > i. – Turkish vowel harmony: Turkish has both I-‐harmony and U-‐harmony but the la\er is more restricted (Pöchtrager 2012).

Consonant Inventory

• It is more likely for |U| to be headed (labial) in Cs than non-‐headed (velar), i.e., normally labial Cs are more frequent than velar Cs.

• It is more likely for |I| to be non-‐headed (coronal) in Cs than headed (palatal), i.e., normally coronal Cs are more frequent than palatal Cs.

• Not surprising, assuming that headedness correlates with posiYonal fitness.

LAB first, DORS last, COR in the middle? (1)

• McNeilage & Davis (2000), Fikkert & Levelt (2008). Tendency for labials to occur in the onset and for dorsals to occur in the coda.

• E.g., Dutch infants pass through a stage when a word like kip ‘chicken’ is realized as [pɪk]. Dutch has more words beginning with a labial than with a dorsal.

LAB first, DORS last, COR in the middle? (2)

• In a number of languages (Veneto Italian, Kagoshima Japanese, Huallaga Quechua, Seri, etc.), nasals in the coda neutralize to [ŋ].

• According to De Lacy & Kingston (2013), [ŋ] is in fact the phoneYc realizaYon of a placeless nasal. However, they also report that in Uradhi phrase-‐final [ŋ] alternate with [k].

• Moreover, in English and Portuguese the coronal lateral becomes velar in the coda. In some varieYes of Brazilian Portuguese, the velar lateral vocalizes in [u]. Similar path from LaYn to French (e.g., alba > aube).

LAB first, DORS last, COR in the middle? (3)

• When an iniYal consonant cluster begins with a nasal, it is normally [m], e.g., [mn-‐] in Ancient Greek, Khasi, [mg-‐, mn-‐] in Russian, Polish, etc. The velar nasal is banned from the onset in a number of languages (e.g., Germanic lgs).

• Younger speakers of Kikun (Atayalic) turn final labials into dorsals, e.g., talap vs. talak ‘eaves’, qinam vs. qinaŋ ‘peach’.

• French: final Cs are normally deleted, but [k] is more likely than [p, t] to be preserved, cf. lac ‘lake’ [lak] vs. lait ‘milk’ [lɛ], coup ‘stroke’ [ku].

LAB first, DORS last, COR in the middle? (4)

• Georgian complex clusters (Butskhrikidze 2002, Gvinadze 1970): in six member clusters the order is the following: – C1 = labial, C2 = r, C3 = coronal/palatal, C4 = velar, C5 = v, C6 = liquid or nasal. Any set can be skipped, but the order cannot be reversed. Eg., /brdɣvna/ ‘to fight’, /prckvna/ ‘to peel’.

– U must precede I/I which precedes U.

What about Coronal?

• |I| as absolutely unmarked, regardless of posiYon (iniYal, medial, final) or the nature of the slot (C or V).

• As a result, consonant epenthesis ooen consists of inserYon of a coronal C.

• [t] occurs intervocalically much more than [p, k].

Frequency: Italian

• Voiceless obstruents in spoken Italian (Baroni 2014). [p, f] are more frequent word-‐iniYally than intervocalically, while for [t] the opposite holds true (relaYvely few words beginning with [t]).

• Data from four dialogues extracted from a spontaneous speech corpus (CLIPS 2009).

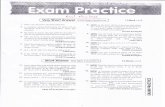

DistribuYon of stops • 489 tokens of [p], 405 tokens of [k], 1116 tokens of [t]. Italian doesn’t allow obstruents in the coda (except [s]).

• [p]: 62.5% word-‐iniYal (both pV and pRV), 22% medial, 15.5% C_.

• [k]: 54.3% word-‐iniYal, 15% medial, 30% C_. • [t]: 8% word-‐iniYal, 26% medial, 66% C_. • [p] and [k] occur mostly word-‐iniYally, [t] postC. • Word-‐iniYally: p > k > t. • Medially: t > p > k. • Post-‐C: t > k > p.

RealizaYon of stops

• Intervocalically, [t] is less likely than [p] and [k] to undergo reducYon and deleYon. [k] is more likely than [p] to be deleted.

• In general, – Full realizaYon: p > t > k – ReducYon: p > k > t – DeleYon: t > k > p.

Frequency: English

• English (using Bruce Hayes’ English Phonology Search sooware, based on the CMU Pronouncing DicMonary): labial Cs are most frequent word-‐iniYally, velars in the internal coda and coronals in the other posiYons.

DistribuYon of Cs by Place in English

Word-‐Initial

Post-‐C Coda Mirror

InterV Inter-‐ nal Coda

Word-‐Final

Coda

U 4797 1565 6362 3900 462 1566 2028

U 2216 369 2585 1339 1209 1105 2314

I 729 818 1547 1834 5 619 624

I 4281 2842 7123 6618 822 7878 8700

ObservaYons on the coda

• Coronals might be the preferred coda Cs in English and other languages because historically they used to be between two Vs.

• Today final Cs might have been yesterday’s intervocalic Cs.

• As a ma\er of fact, internal coda Cs are mostly velar.

Default elements: Strong version (I)

• CVCV framework (Lowenstamm 1999, Scheer 1999, 2004, 2012) – Government as inhibiYng force – Licensing as corroboraYng force – Coda Mirror: # and C_ as strong posiYon (immune to leniYon, prone to forYYon)

– V_V and _ø, _# as weak posiYons

Default elements: Strong version (II)

• Certain elements prefer to occur in certain syllabic posiYon. Since the default consonantal element is |U|, |U| is projected/appears in C slots (or C slots are preferably interpreted as U-‐sounds). Conversely, |A| is projected in V slots or V slots are preferably interpreted as |A|.

• In strong posiYons, |U| is headed, i.e., labials prefer to occur in the onset.

• In the coda, C is weak but it’s not directly affected by a V à |U| (unheaded)

• Intervocalically, |I|, which is more vocalic than |U| yet being unmarked (|A| would be marked).

Default elements: Strong version (III)

• This would explain – Velar realizaYon of nasals and laterals in the coda – Absence of U-‐consonants as epentheYc segments (intervocalically).

It could also solve the long lasYng debate on markedness: is velar or coronal the unmarked PoA? Possibly both: coronal intervocalically, velar in the coda.

Default elements: Weak version

• Issues with the strong version: – Labials are never epentheYc (except [w], e.g., Chamicuro, De Lacy 2006:106). We should expect labials to be inserted to avoid empty onsets, but word-‐iniYal epenthesis normally consists of glo\al stops.

– In Tundra Nenets (Salminen 1998), the default iniYal C is [ŋ], e.g., Russian armija > Tundra Nenets ŋarmiya. In certain Mandarin dialects, [ŋ] and [ɣ] can be used as iniYal epentheYc Cs (Duanmu 1990:18).

– Possible soluYon: |U| is indeed the possible default element for C but epentheYc (non lexical) elements can never be headed.

|U| = C and |A| = V?

• Frameworks such as Dependency Phonology (Anderson & Ewen 1987) and Radical CV Phonology (van der Hulst 1994, 1995).

• Every element is either C or V. • Each segment consists of C, V or different combinaYons of the two.

• Manner-‐wise, C is stopness = [ʔ], V is sonority. • Proposal: Place-‐wise, C = |U|, V = |A|. |I| is a li\le bit of both and because of that, it is unmarked.

• Possibly |I| = C-‐V where neither C nor V prevails.

Conclusions • The three primes |A, I, U| differ in the degree of

vocalicness. |A| would be a direct phoneYc interpretaYon of V.

• Whether C can be placeless (i.e., [ʔ]) or not is a language-‐specific ma\er. There seems to be evidence that Cs tend to be U-‐colored, especially when they are in posiYons unaffected by Vs (ungoverned).

• If |U| interprets C and |A| interprets V, the real unmarked element is |I|, which appears to occur freely in both slots. Because of that, it is, at the same Yme, fi\er than |A| in C and fi\er than |U| in V.

• |I| is different from both |A| and |U|, e.g., immunity to OCP restricYons.

Selected references (1) • Backley, P. 2011. An IntroducMon to Element Theory. Edinburgh:

EUP. • Baroni, A. 2014. The Invariant in Phonology. The role of salience and

predictability. In prep. • Botma, B. 2004. Phonological Aspects of Nasality. An Element-‐

Based Dependency Approach. Utrecht: LOT. • Butskhrikidze, M. 2002. The consonant phonotacMcs of Georgian.

PhD diss., Utrecht: LOT. • De Lacy, P. & Kingston, J. 2013. Synchronic explanaYon. Natural

Language and LinguisMc Theory 31.2. 287–355. • Fikkert, P. & Levelt, C., 2008. How does Place fall into place? The

lexicon and emergent constraints in children's developing phonological grammar. In Avery, P., Dresher, B. E. & Rice, K. (eds.), Contrast in Phonology. Theory, percepMon and acquisiMon. Berlin, Mouton, pp. 231-‐268.

Selected references (2) • Kaye, J., Lowenstamm J. & Vergnaud, J.-‐R. 1985. The

internal structure of phonological representaYons: a theory of Charm and Government. Phonology Yearbook 2. 305-‐328.

• Pöchtrager, M. 2012. Binding in Phonology. In press. • Savy, R. & Cutugno, F. 2009. CLIPS. Diatopic, diamesic and

diaphasic variaYons in spoken Italian. Proceedings of the 5th Corpus LinguisMcs Conference, Liverpool, 20th -‐ 23rd July 2009.

• Scheer, T. 1999. A theory of consonantal interacYon. Folia LinguisMca 32. 201-‐237.

• van der Torre, E. J. 2003. Dutch sonorants. The role of place of arMculaMon in phonotacMcs. Utrecht: LOT.