A. Sampson 2014, The Mesolithic in the Aegean, in Manen C., Perrin T. & Guillaine J.et al. (eds),...

Transcript of A. Sampson 2014, The Mesolithic in the Aegean, in Manen C., Perrin T. & Guillaine J.et al. (eds),...

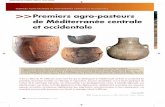

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

189189

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

The site of Maroulas on Kythnos is located along the coast, close to the modern settlement of Loutra. A rescue excavation at the site was initiated in 1996 and after an interval of several years the excavation has been continued by the University of the Aegean between 2001 and 2005.

Thirty-one circular or ellipsoid stone dwelling features have been excavated at Maroulas. These dwelling features seemingly have parallels in the Natufian and Harifian cultures that flourished in the Syro-Palestinian region between 12000 and 9500 cal. BC, as well as in Eastern Anatolia and on Cyprus.

During the first excavation season, eight burials have been unearthed in different locations within the excavated area. The skeletons were found in a crouched position, typical for that period. In 2005 additional human remains have been discovered in different parts of the settlement. In total, 26 burials have been recognized below the floors of the huts, excepted for a bone concentration corresponding to four burials laid down on the floor of feature C21. The practice of burying individuals below the floors of the houses is common in Mesolithic cultures in many parts of the world as in the Natufian and in most of the PPN sites in the Near East and in Anatolia, as in Çatal Höyük.

The gracile skeletons suggest that the Mesolithic settlers of the area belonged to the Caucasoid or Protomediterranean anthropological type and confirm the local roots of the inhabitants of the Aegean islands.

At the start of the 1996 excavation, two samples on shells yielded the dates 9522±50 BP (9140-8758 cal. BC) and 9621±40 BP (9188-8851 cal. BC). A sequence of six C14 dates on charcoal stems from trench 2 and indicates a dating within the first half of 9th millennium BC (8800-8600 cal. BC). As a conclusion, the constructions in the settlement of Maroulas were contemporary and had been used during a time span of several centuries at the beginning of the 9th millennium BC. Thus, the settlement, the earliest so far in the Aegean basin, is dated to the beginning of the Lower Mesolithic.

The lithic industry from Maroulas mirrors the adaptation of the groups inhabiting the site to local raw materials, especially quartz – the most important among them. As other Mesolithic industries in mainland Greece (e.g. Franchthi) the industry at Maroulas is a flake industry including a small component of microlithic forms.

The site yielded several thousand chipped stone artefacts made from quartz, flint, and obsidian. About 80% of the chipped

THE MESOLITHIC OF THE AEGEAN BASIN

LE MÉSOLITHIQUE DU BASSIN ÉGÉÉN

AdAmAntios sAmpson

ABSTRACT

stone artefacts were made from local quartz, 16.8% from Melian obsidian, and the others from white-patinated flint. The low proportion of microliths can be explained by decreasing importance of hunting while gathering, especially of land snails and plants, dominates. This type of subsistence economy favoured the production of scraping and cutting tools.

The economy of the Mesolithic inhabitants of Maroulas primarily focused on the exploitation of marine resources, first and foremost on fishing although the quantities are smaller than the ones recovered from Cyclops Cave and Franchthi. A few mammal species were represented such as brown hare, marten and red fox, while 41.32% of the total vertebrate fauna collected at Maroulas belonged to the Suidae family.

The Cyclops Cave project on the Gioura island started in 1992 and was achieved in 1996. Radiocarbon dating assigned the material to the Early Holocene, more specifically to the 9th-7th millennium BC, indicating contemporaneity with the Early Holocene levels at Franchthi. Local flint and Melian obsidian have been used for the manufacturing of the Mesolithic chipped stone industry of the Cyclops Cave, suggesting the existence of an exchange network for the exploitation of obsidian at such an early stage. The Cyclops Cave deposits yielded a rich collection of worked bone tools, such as fish hooks of various sizes and shapes, ranging from the U-shaped hook type to the bi-pointed implement. An important concentration of fish bones, sea shells, land snails, mammal bones and bird remains imply that the Cyclops Cave has been occupied on a seasonal basis by hunter-gatherers, specialized in fishing and bird hunting.

The study of the faunal material from the Cyclops Cave shows the occurrence of Capra aegagrus bones in a transitional stage of domestication in the Lower Mesolithic (8600-7500 cal. BC). In the lowest Mesolithic levels (end of 9th millennium BC) the majority of caprids (found in very limited numbers) belonged to goats (Capra aegagrus) and a few bones only to sheep. One can suppose a spread of such an early domestication in the Aegean basin as early experiments of domestication in the Zagros Mountains have been dated to 8500-8000 cal. BC.

Compared to the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic period, only small numbers of Mesolithic sites are known as most of them have been submerged or destroyed. Nevertheless, surveys on the Mesolithic on the Aegean islands and in mainland Greece are encouraging.

190190

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

Movements of people between the Aegean islands that are close to each other are beyond debate. Moreover, it is most likely that Mesolithic seafarers travelled to the western coast of Asia Minor. The recent discovery of five Mesolithic sites on Ikaria, Naxos and the Dodecanese showing strong similarities with Kythnos reinforces this theory.

As a conclusion, the Mesolithic, as it has been evidenced so far, was a period with sharp regional differentiation and economic complexity. It may also be viewed as a period of experimentation, with regard to food procurement strategies. Elements of proto- neolithization, appearing in the Aegean during the Mesolithic, may indicate, on the one hand, the existence of a centre of neolithization, comparable to the one on Cyprus

Le site de Maroulas à Kythnos est situé le long de la côte, près du village actuel de Loutra. Une fouille de sauvetage initiée en 1996 a été reprise après quelques années d’interruption par l’université de l’Égée, de 2001 à 2005.

A Maroulas, 31 structures d’habitat en pierre de forme circulaire ou ellipsoïdale ont été dégagées. Ces structures semblent trouver des parallèles dans les cultures natoufienne et harafienne qui se sont développées dans la région syro-palestinienne entre 12000 et 9500 BC ainsi que dans l’est de l’Anatolie et à Chypre.

À partir de la première saison de fouille, huit squelettes déposés en position fléchie, les jambes croisées, typiques de cette période, ont été découverts en différents points du gisement. En 2005, d’autres restes humains ont été mis au jour. Au total, vingt-six sépultures ont été retrouvées sous les sols des bâtiments, excepté pour une concentration de quatre sépultures sur le plancher de la maison C21. La pratique d’enterrer les corps sous les sols des habitations est habituelle dans les cultures mésolithiques dans de nombreux endroits du monde comme dans la culture natoufienne et dans presque tous les sites du Néolithique précéramique au Proche-Orient et en Anatolie, par exemple à Çatal Höyük.

La gracilité des squelettes suggère que les habitants mésolithiques de cette région appartenaient au type anthropologique caucasien ou protoméditerranéen, confirmant les origines locales des populations des îles égéennes.

Au début de la fouille en 1996, deux échantillons sur coquillage ont fourni les dates suivantes : 9522±50 BP (9140-8758 cal. BC) et 9621±40 BP (9188-8851 cal. BC). Une séquence de six dates 14C sur charbon, issues de la tranchée 2, ont donné une date se situant dans la première moitié du IXe millénaire (8800-8600 cal. BC). Les structures de l’habitat sont donc contemporaines et ont été occupées pendant une période de quelques siècles, au début du 9e millénaire BC. Ce site d’habitat

RÉSUMÉ

(theory of “multi-focus neolithization”), and on the other hand, the existence of sea routes for the diffusion of populations or ideas during Early Pottery Neolithic. Presuppositions for this diffusion are Mesolithic sea routes among the Aegean islands and Pre-Pottery Neolithic seafaring in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially between Anatolia, the Levantine coast and Cyprus.

Most recent surveys performed in the Aegean revealed several sites at small distances from the sea. Furthermore, it is expected that excavations in caves in the mainland will produce important discoveries, as is the case of the Theopetra and Sarakenos Caves in Boeotia. The fact that we are starting to understand the methods of surveying in order to detect Mesolithic open air sites, especially in the Aegean basin, gives hope.

est daté du début du Mésolithique ancien et il s’agit du plus ancien mésolithique de l’aire égéenne.

L’industrie lithique de Maroulas reflète l’adaptation des populations aux matières premières locales, spécialement le quartz, la plus importante d’entre elles. Comme pour d’autres industries mésolithiques de Grèce continentale (cf. Franchthi), l’industrie de Maroulas est une industrie sur éclats avec une petite composante microlithique.

Le site a livré plusieurs centaines d’objets taillés à partir de quartz, de silex et d’obsidienne. Environ 80% de ces objets ont été réalisés en quartz local, 16,8 % sur de l’obsidienne de Mélos et le reste sur du silex patiné blanc. La faible proportion de microlithes peut s’expliquer par un déclin de la chasse dans l’économie de subsistance alors que la cueillette domine, spécialement le ramassage d’escargots terrestres et de plantes. Ce type d’économie favorise la production de grattoirs et d’outils tranchants.

L’économie des habitants mésolithiques de Maroulas était en premier lieu basée sur l’exploitation des ressources marines, la pêche en particulier, mais la quantité des restes est moins importante qu’à la grotte du Cyclope et à Franchthi. Quelques mammifères étaient présents, tels le sanglier, la martre et le renard, tandis que 41,32 % du total des vertébrés retrouvés à Maroulas appartiennent à la famille des suidés.

Le projet de la grotte du Cyclope sur l’île de Youra a débuté en 1992 et s’est achevé en 1996. Les dates 14C permettent d’attribuer le matériel au début de l’Holocène, plus précisément au IXe-VIIe millénaires, ce qui place la grotte du Cyclope à un stade contemporain des niveaux du début de l’Holocène de Franchthi. Le silex local et l’obsidienne de Mélos sont utilisés pour la taille de l’industrie mésolithique, suggérant la présence de réseaux d’échange en relation avec l’exploitation de l’obsidienne à une date aussi précoce. Les dépôts de la grotte du Cyclope ont livré une riche collection d’outils en

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

191191

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

os travaillés, tels des hameçons de tailles et de formes variées allant du modèle en forme de U à des bipointes. L’importante concentration d’os de poissons, de coquillages marins, d’escargots terrestres, de restes de mammifères et d’oiseaux implique que la grotte du Cyclope a été occupée de manière saisonnière par des chasseurs-cueilleurs spécialisés dans la pêche et la chasse des oiseaux.

L’étude du matériel faunique de la grotte du Cyclope montre la présence de restes de Capra aegagrus en voie de domestication, dans le Mésolithique ancien (8600-7500 BC). Dans les niveaux les plus bas du Mésolithique (fin du Xe millénaire cal. BC), la majorité des caprinés (trouvés en nombre limité) appartiennent à des chèvres (Capra aegagrus) et quelques os proviennent de moutons. On peut supposer une diffusion de cette domestication précoce dans le bassin égéen étant donné que dans les montagnes du Zagros les premières expérimentations de domestication ont été datées de 8500-8000 cal. BC.

Pour la période mésolithique, nous ne connaissons qu’une petite fraction des sites comparé au Paléolithique et au Néolithique, la plupart se trouvant aujourd’hui submergés ou détruits. Néanmoins, les prospections concernant la recherche de sites mésolithiques dans le bassin égéen et en Grèce continentale sont encourageantes.

Des mouvements de populations entre les îles égéennes, proches les unes des autres, sont incontestables. De plus, il est fort probable que les navigateurs mésolithiques aient atteint la côte

ouest de l’Asie Mineure. Les récentes découvertes de cinq sites mésolithiques à Ikaria, Naxos et dans le Dodécanèse présentent de fortes ressemblances avec Kythnos et renforcent cette théorie.

En conclusion, le Mésolithique, tel qu’il se présente jusqu’ici, a été une période à forte différenciation régionale et à économie complexe. Cette période peut être considérée comme une période d’expérimentation concernant les stratégies de subsistance. Des éléments de proto-néolithisation apparaissent en Égée durant le Mésolithique et peuvent indiquer, d’un côté, un centre de néolithisation, comparable à celui de Chypre (« théorie polycentriste de la néolithisation ») et d’un autre côté l’existence de routes maritimes permettant la diffusion des personnes ou d’idées au cours du Néolithique ancien à poterie. Des conditions préalables pour cette diffusion sont l’existence de routes maritimes mésolithiques entre les îles égéennes et la navigation de groupes du Néolithique acéramique dans l’est de la Méditerranée, plus particulièrement entre l’Anatolie, la côte du Levant et Chypre.

De très récents travaux en Égée ont révélé la présence de sites à proximité de la mer. En outre, on peut espérer que les fouilles dans des grottes sur le continent vont permettre d’importantes découvertes, comme cela est le cas dans les grottes de Theopetra et de Sarakenos en Béotie. Le fait que nous commençons à comprendre les méthodes de prospections à mettre en place afin de localiser les sites de plein air mésolithiques, spécialement dans le bassin égéen, ouvre des perspectives nouvelles.

Over the last two decades a hitherto unknown cultural stage has been defined in the Aegean basin. In 1992, excavations in the Cyclops Cave yielded evidence for Mesolithic occupations underlying the Neolithic levels. In 1996, the excavation of the Mesolithic open air site of Maroulas on Kythnos revealed huts with circular ground plans including burials below the floors. Moreover, a survey on the island allowed identification of further five Mesolithic dwelling places. In 2004, on the island of Ikaria in the Eastern Aegean a survey permitted to recognize a cluster of Mesolithic sites, and, in 2007, during the excavation in Kerame 1

a large Mesolithic settlement has been unearthed of which the lithic industry shows similarities with the one of Maroulas. In addition, Mesolithic sites have been discovered on the Cycladic islands of Naxos and Melos as well as on the island of Chalki in the Dodecanese. Most recently, Mesolithic sites have been reported from eastern Crete and the island of Gavdos. Consequently, it appears that the Mesolithic stage is not an isolated phenomenon but extends over the entire Aegean basin. In parallel, surveys in the Greek mainland and excavations in caves (Theopetra, Sarakenos) revealed new variants of the Mesolithic culture.

INTRODUCTION

192192

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

CYCLOPS CAVE ON GIOURA

The Cyclops Cave on the Gioura island in the Northern Sporades (fig. 1, fig. 2) has been investigated between 1992 and 1996 within a research project (Sampson, 2008a and 2011). The vestigial remains were dated by radiocarbon to the Early Holocene, more specifically to the 9th-7th millennium cal. BC, implicating contemporaneity with the Early Holocene level at Franchthi. Local flint and Melian obsidian were used for the manufacturing of the chipped stone industry of Gioura suggesting the existence of an early network of exchange at that period of time. The deposits in the Cyclops Cave yielded a rich assemblage of bone tools, for example fish hooks (fig. 3) of various sizes and shapes, ranging from U-shaped to bipointed types (Moundrea-Agrafioti, 2011). Large concentrations of fish bones, sea shells, land snails, mammal bones and bird remains

indicate that this island has been occupied on a seasonal basis by hunter-gatherers who specialized in fishing and bird hunting (Mylona, 2011; Powell, 2011).

The sector investigated within the cave has yielded 179 lithic artefacts in total. Comparison of the raw material composition between the Early and the Late Mesolithic layers highlights slight increase of the proportion of obsidian in the more recent layers. It is likely that the residents of the Cyclops Cave produced tools from flakes including cortical flakes stemming from sources in mainland Greece (Sampson et al., 1998; Kaczanowska and Kozlowski, 2008). Within the toolkit, splintered pieces dominate. They are also used for the production of thin blanks. In addition, end-scrapers on flakes, retouched flakes and notched tools are present.

Tools made from obsidian, such as trapezes with retouched sides and segments resemble the types recovered from

THE MAIN MESOLITHIC SITES

Fig. 1: The Northern Sporades area.

La région des Sporades du Nord.

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

193193

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

Fig. 2: The western coast of the Gioura island.

La côte ouest de l’île de Youra.

Fig. 3: Mesolithic fish hooks from Cyclops Cave.

Hameçons mésolithiques de la grotte du Cyclope.

Fig. 4: The stratigraphy of the Cyclops Cave.

La stratigraphie de la grotte du Cyclope.

194194

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

Neolithic contexts dated to the Early/Middle Neolithic and Late Neolithic. These tools occur during a long period of time mirroring specialized activities performed by the inhabitants of the Cyclops Cave but also an adaption to local environmental conditions and an atypical economy characterizing this region during both the Mesolithic and Neolithic. This hypothesis can be confirmed through the presence of similar types in Middle/Late Neolithic contexts on the island of Kyra Panagia (Moundrea-Agrafioti, 1992). Intrusions from overlying deposits have to be excluded. In order to confirm the excavation data, the recent SIMS-SS obsidian hydration dating method has been employed for the obsidian artefacts (Laskaris et al., 2011).

The study of the faunal remains from the Cyclops Cave revealed the presence of wild goat (Capra aegagrus) at a transitional stage of domestication during the Early Mesolithic period (8600-7700 cal. BC). In the lowest levels assigned to the Mesolithic (at the end of the 9th millennium cal. BC) most of the caprid bones (discovered in very small numbers) belong to goats (Capra aegagrus) and only some to sheep (Trantalidou, 2003 and 2011). The spread of such an early domestication into the Aegean basin can be assumed given that early attempts of domestication in the Zagros Mountains have been dated to 8500-8000 cal. BC. As a matter of fact, goat domestication in the Zagros region (Helmer, 1994) has been first attempted between 8500 and 8000 cal. B.C., at the same time as in Anatolia and on Gioura. For this period, early exploitation of sheep is reported from Zawi Cemi Shanidar, Karim Shahir in Iran, Asiab, Cayonü in Turkey, and Mureybet in Syria (Uerpmann, 1981). However, according to K. Trantalidou, the absence of wild ancestors in the Aegean and mainland Greece at the start of the Holocene implicates that these animals have been introduced from the Near East where domestication was first completed (Masseti, 1998).

With regard to the economic relevance of domestic animals, it is important to mention that a trend of slaughtering young animals can be observed on Gioura in parallel to changes in animal management during the Mesolithic, for example the predominance of goat compared to boar and a higher age of the slaughtered animals. At the end of the Mesolithic period in the Cyclops Cave, the clear stratigraphy of the site (fig. 4) indicates the presence of herding and farming, similar to the Neolithic.

With regard to the presence of boar in the Cyclops Cave and at the site of Maroulas, K. Trantalidou (Trantalidou, 2003 and 2010) assumes particular management combining animal control and hunting (semi-wild animals roaming on the island), a theory, however, lacking substantial support given the small and heterogeneous samples. In any case, the abundance of oak trees and thus of acorns during the Mesolithic in the Aegean basin (the latter being suitable also for human consumption as argued for Mesolithic Europe and modern Kurdistan) may indirectly have favoured the free pasturage of boar. Contemporaneous ethnographic parallels showing the use of boar in order to clean fishing nets provide additional ideas about the possible

management of animals by Mesolithic fishermen in the Aegean basin. As a conclusion, the domestication of boar, dated to the Mesolithic or PPNA in Hallan Cemi in Anatolia (Rosenberg, 1996), and also in Aetokremnos on Cyprus (Simmons, 1999) occurs much earlier.

MAROULAS ON KYTHNOS

The site of Maroulas on Kythnos (fig. 5, 6) is a coastal site, located close to the modern settlement of Loutra (Honea, 1975). Rescue work at this site started in 1996 (Sampson, 1996) and after an interruption of several years the excavation has been continued by the University of the Aegean up until 2005. In total, thirty-one circular or ellipse-shaped stone dwelling features have been excavated (Sampson et al., 2002 and 2010). They are mainly located in the eastern part of the settlement, close to the coast (fig. 7). Due to heavy erosion and in the absence of sedimentation, the features were seriously damaged. The paving of the dwelling features 2 and 3 was stratified indicating their repeated use. At the north-eastern margin of the site, a stone-paved floor of irregular dimensions has been uncovered, partly destroyed in the seawards area. Further to the south, in trench 3, an oval-shaped construction, probably the best preserved in the site, has been excavated including at least four superimposed floors (fig. 8).

The settlement features on Kythnos seemingly have parallels in the Natufian and Harifian cultures (Valla, 1998; Lieberman, 1998) that developed in the Syro-Palestinian region 12000 and 9500 cal. BC, as well as in Eastern Anatolia (Rosenberg, 1999) and on Cyprus (Guillaine and Briois, 2001).

From the first excavation season on, eight individuals buried in a crouched position, typical for this period, have been discovered in different locations within the area (fig. 9). In 2005, additional human remains have been discovered in different parts of the settlement. In total, 26 burials have been found below the floors, except for the bone concentration grouping together four burials on the floor of feature C21. The practice of burying individuals below the floors of the huts is widespread in Mesolithic cultures in many parts of the world as in the Natufian (Perrot, 1966), and in almost all pre-pottery sites of the Near East and Anatolia, as for example in Çatal Höyük. The gracile skeletons suggest that the Mesolithic people of the area belonged to the Caucasoid or proto-Mediterranean anthropological type and confirm the local roots of the inhabitants of the Aegean islands (Poulianos, 2010).

A sequence of five radiocarbon dates on charcoal stemming from trench 2 and six further samples from other parts of the site cover the first half of the 9th millennium (8800-8600 cal. BC). As a conclusion, the settlement features discovered in the site of Maroulas were contemporary and had been used during a time span of several centuries at the start of the 9th millennium cal. BC. Thus, the settlement is dated to the beginning of the Early Mesolithic and is the earliest one identified so far in the Aegean area, contemporaneous to the PPNA of the Near East.

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

195195

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

Fig. 5: Mesolithic sites on Kythnos.

Les sites mésolithiques de l’île de Kythnos.

Fig. 6: The site of Maroulas.

Le site de Maroulas.

The lithic industry recovered from Maroulas shows the adaptation of the human groups inhabiting the site to local raw materials, especially quartz (rock crystal) – the most important among them. Like other Mesolithic industries in mainland Greece (e.g. Franchthi, Perlès, 1990), the chipped stone industry of Maroulas is a flake industry including a minor component of microlithic shapes. The site yielded several thousand chipped stone artefacts made from quartz, flint, and obsidian. About 80% of the chipped stone artefacts were made from local quartz, 16.8% from Melian obsidian, and the other from flint with a white patina. The small number of microliths can be explained by decreasing importance of a subsistence economy based on hunting whilst foraging dominates, especially the gathering of land snails and plants. This type of subsistence economy favoured the production of scraping and cutting tools.

Fig. 7: Reconstruction of a Mesolithic hut.

Reconstitution d’une hutte mésolithique.

196196

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

Fig. 8: Maroulas. A semi-subterranean structure.

Maroulas. Une structure semi-enterrée.

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

197197

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

The economy of the Mesolithic inhabitants of Maroulas primarily focused on marine resources, mainly fishing, but the faunal assemblage is much smaller than the one recovered from Cyclops Cave and Franchthi. Only a few mammal species were represented such as brown hare, marten and red fox, while 41.32% of the total vertebrate fauna collected at Maroulas belong to the Suidae family (Trantalidou, 2010). Ground stone tools and querns indicate the processing of wild cereals and grasses. Fishing was an important activity for the Mesolithic inhabitants at Maroulas according to a recent study (Mylona, 2010). The fishermen focused on two types of resources, the migratory, seasonal fish, and distinct inshore species. They caught medium size migratory fish and the large size inshore fish. Maroulas provides evidence for the processing and preservation of fish, and therefore the specific size range might have been chosen as being the most suitable for this purpose.

THE OTHER MESOLITHIC SITES OF THE AEGEAN

Ikaria is a large island of the Eastern Aegean that remained isolated from Antiquity to more recent days due to its lack of natural ports and its rough and mountainous environment. To date, archaeological research has been rare, and the prehistory of the island has remained completely unclear.

Since 2003 new prehistoric sites have been identified in the western and eastern part of the island and, more significantly, in the area between Agios Kirikos and Faros. During a systematic survey in 2004 more than 20 prehistoric sites including five pre-Neolithic sites have been located. The fact that five sites featuring Mesolithic stone industry have been spotted is indicative of a network of sites and not just an occasional frequentation of the area. Kerame 1 is considered as being a major site of the Mesolithic, while the other sites seemingly are smaller occupations. As a matter of fact, its area of settlement extends over a surprisingly large area, much bigger than the one of Maroulas on Kythnos. Adding the eroded part, this settlement presumably has been even larger. It therefore was not a small camp site, but a real settlement. The stone artefacts were scattered over an area of 8000 m2, mainly in the low-lying eastern part of the site which probably corresponds to the westernmost part of the settlement.

Kerame 1 is a peninsula with steep coasts jutting into the sea (fig. 10). In the past it was much more extended as shown by large rocks that collapsed in the sea because of earthquakes or natural erosion. It can be assumed that only the westernmost part of the site has been preserved, while its main part was destroyed by erosion and the collapse of rocks in the sea. Recent terrestrial

Fig. 9 : Maroulas. Mesolithic skeleton.

Maroulas. Squelette mésolithique.

198198

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

Fig. 10: The site of Kerame 1 on Ikaria.

Le site de Kerame 1 sur l’île d’Ikaria.

Fig. 11: Kerame 1. The excavation.

Kerame 1. La fouille.

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

199199

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

Fig. 12: Kerame 1. Lithic industry.

Kerame 1. Industrie lithique.

Fig. 13: The Mesolithic site on Chalki.

Le site mésolithique sur l’île de Chalki.

and submarine geological research performed in the area has shown that the peninsula extended over another dozens of square meters seawards. Prior to the excavation, artefacts of obsidian and flint have been collected from the entire area slightly inclined to the eastern direction.

Field research in the area lasted three weeks in 2007 and three weeks in 2008. Within an excavation grid, eleven trenches have been opened (fig. 11). Their profiles have been documented and they revealed the same stratigraphic sequence. Three layers have been identified: the first and thickest (0.20 – 0.30 m) being composed of pure brown soil, followed by the second (0.30 m) constituted by light brown soil including small- or large-sized stones, and the third mainly containing gravel (Sampson et al., 2008).

Apart from several thousands of stone artefacts made from obsidian and flint, no organic remnants or clear features have been recovered in that the archaeological remains have suffered damage from intensive cultivation of the area. Slabs in horizontal position identified in trenches C and E are most likely remnants of features and it cannot be excluded that one part may have been destroyed by erosion. These features were made of perishable material (timber and plant material) and left no traces. The eastern low-lying part of the settlement probably hosted further architectural remains or burials which have been submerged and destroyed as a result of the rise in sea level.

It is striking that the lithic tools found in these sites (fig. 12) bear close similarities with the ones recovered from the site of Maroulas on Kythnos (Sampson et al., 2010). These similarities help us to establish a comparative dating framework for the Early Mesolithic and may attest to contacts and movements in the Aegean from such an early period on.

More particularly, the presence in Kerame 1 of a large number of obsidian pieces stemming from Yali on Nissyros (Sampson, 1987, 1988 and 2006) is noteworthy. It highlights the introduction of raw materials of lower quality from nearby sources in parallel to Melian obsidian.

Three samples recovered from the two upper layers of trenches C and D have been addressed for Optical Luminescence dating, but unfortunately the results of the analyses indicate more recent ages (2nd-3rd millennium cal. BC) than expected. Equally three samples of charcoal from the trenches provided quite recent dating. Finally, samples of obsidian artefacts dated with the recent SIMS-SS method (Laskaris et al., 2011) indicate ages that correspond to the chronology of the site (10152±1640 BP and 11085±3282 BP).

In the last few years, numbers of new sites have completed the picture of Mesolithic site distribution and settlement. The recent discovery of a Mesolithic site in the south-eastern part of Naxos, on the supply route of obsidian from Melos to Ikaria, as well as the affinities of the lithic industry with those of Maroulas and Kerame 1 seems to enlarge the network of contacts during this period (Sampson, 2010). The long-lasting search for Mesolithic sites in the Dodecanese has been worth the effort with the recent discovery of an important site on the island of Chalki near Rhodos (fig. 13). The large quantities of Yali obsidian seem reasonable given the short distance from this source, whilst resemblances of the lithic industry with those of the Cycladic islands and Ikaria attests to the spread of networks of influence to the southern direction.

200200

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

Notwithstanding the research progresses registered in mainland Greece and in the islands, gaps currently subsist given the still unequal distribution of Mesolithic sites. In northern Greece, recent research carried out in Thrace as well as in central and western Macedonia has been unsuccessful with regard to the detection of Mesolithic sites. A survey in the region of Langada (Kotsakis and Andreou, 1999) failed to detect Mesolithic sites, except for the site of Sarakina, probably representing a Mesolithic or Early Neolithic settlement (Kotsakis, 2000).

Although northwestern Greece witnesses particular dense distribution of Palaeolithic sites, the Mesolithic stage remains unknown. The survey conducted by C. Runnels in the region of Preveza (Runnels et al., 1999; Runnels and Van Andel, 2003) has been encouraging with regard to the presence of Mesolithic lithic artefacts in numerous sites. Although true camp sites have not been discovered there, the concentrations of artefacts near the current coast are noteworthy because they indicate an economic change for this period and are reminiscent of Holocene sites in northern Europe. The site of Sidari on Corfu (Sordinas, 1969 and 2003) provides evidence for the same type of economy. It is not a permanent settlement but probably a seasonal camp for the gathering of some special food. In the same area, further Mesolithic findings have also been reported from Thesprotia at the occasion of surveys carried out by Danish archaeologists.

The cave of Theopetra in western Thessaly (Kyparissi-Apostolika, 2003) is a particular site. However, due to the lack of a reliable stratigraphy and to the thin Mesolithic strata, we cannot draw a clear picture of the lithic industry, neither of plant and animal remains. The cave may be considered as a base camp. However, in the absence of other Mesolithic sites in the area and given the thin occupation layers, this site corresponds rather to a temporary settlement. Nonetheless, the inland location of this site is very important, because it challenges theories on the desertification of Thessaly during that period. Moreover, additional open air sites dated to the same period may be expected in the area. Hopefully, the final publication of the excavations carried out these last years, will provide new data.

Further south, excavations in the Sarakenos Cave in Central Greece (fig. 14) are still in an initial stage with regard to the Mesolithic layers. This cave, the only one amongst hundreds of small and large caves and rock shelters in the region of the former lake Kopais, which has not been affected by past lake fluctuations, may have been an important base camp. The outstanding preservation of the pre-neolithic layers (fig. 15), the presence of large hearth features and a large series of radiocarbon dates are promising discoveries on this dark period of the Early Holocene and particularly the transition between the Mesolithic and the Early Neolithic (Sampson, 2008b; Sampson et al., 2009). According to absolute dating chronologies, the beginning of the Mesolithic period in the cave starts in the 10th millennium cal. BC.

In Attica, it is still uncertain whether the Keratsini Cave features a Mesolithic stage. This discovery of a Mesolithic skull fragment in a cave in the region of Kokkinovouni, in the Mesogeia area, is not ascertained. Nonetheless, in western Attica the Mesolithic evidence in the cave of Zaimis (Markovits, 1933) should be considered as certain despite objections raised by other researchers.

Research into the Mesolithic in the Peloponnese should be considered incomplete except for the region of the Argolid presenting substantial density of Mesolithic sites. Following the excavation of Franchthi Cave a survey carried out in this region resulted in lithic assemblages stemming from about thirty sites (fig. 16), and recently, a survey in the eastern part of the Argolid led to the discovery of numerous findspots but no settlement site (Runnels et al., 2005; Runnels, 2009). Rock shelter 1 in the Klissoura Gorge is another stratified site in the Argolid (Koumouzelis et al., 1996 and 2003) where the excavation results give rise to still open questions. Except for the caves of Franchthi, Klissoura in the Argolid, Theopetra, Sarakenos and Zaimis in Attica, there are no other stratified Mesolithic sites in the mainland.

Next to research in the mainland, research on the islands in the Aegean has been profitable. The Cyclops Cave on the isolated islet of Gioura was a small seasonal or permanent camp for hunters and fishermen who exploited the island. However, the important stratigraphic sequence that spans the entire Mesolithic period and the large amounts of fish bones led to the assumption that Mesolithic groups stemming from the area of the Northern Sporades frequented the cave mainly during the summer months when the fishing activities were at their peak.

The site of Maroulas lies off the Eastern Peloponnesus and seems to present a more direct connection with less distant Attica. Nomadic residential mobility is more suitable for the Mesolithic groups of Kythnos that probably exploited other islands or distinct regions of Attica on a seasonal basis. Maroulas has been a permanent or semi-permanent settlement in contrast to the other five small Mesolithic sites that were found in coastal areas in the eastern part of the island. The same model is also advanced for the eastern part of Ikaria where Kerame 1 seems to be a seasonal base connected with the other four sites in close vicinity.

Currently, Maroulas is the only example for a true settlement including dozens of circular buildings and burials, but other similar sites should exist in the Aegean or in mainland Greece. However, the site cannot be considered as an isolated settlement of Mesolithic groups incoming from the Eastern Mediterranean as presumed by Runnels (Runnels, 1995). In our opinion the theory of their eastern origin has always been an easy explanation, while the indigenous origin requires reflection and careful research. Furthermore, recent strontium analyses (Nafplioti, 2010) performed on a small sample of human teeth stemming from the burials in Maroulas, indicate that the origin of the residents was most likely located somewhere in mainland Greece, more particularly in Attica or southern Euboea.

THE AEGEAN MESOLITHIC AND ITS PERSPECTIVES

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

201201

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

Fig. 14: The entrance of Sarakenos Cave.

L’entrée de la grotte de Sarakenos.

Fig. 15: The Mesolithic layer in Sarakenos Cave.

La couche mésolithique de la grotte de Sarakenos.

202202

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

Fig. 16: Location of Franchthi Cave and other Mesolithic sites.

Localisation de la grotte de Franchthi et d’autres sites mésolithiques.

Fig. 17: Map of the Mesolithic sites in the Aegean basin.

Carte de répartition des sites mésolithiques du bassin égéen.

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

203203

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

Maroulas on Kythnos and Kerame on Ikaria are currently the only excavated settlements in the Aegean. Kythnos is part of a route between Melos and the Greek mainland related to the trade of obsidian (Melos – Kimolos – Siphnos – Seriphos – Kythnos – Keos – Attica – Argolid). By following this route, one could avoid the dangerous open sea from Melos to the Eastern Peloponnesus in the Myrtoon region as it is the case in Franchthi where obsidian from Melos had been imported since the end of the Palaeolithic period. The Mesolithic sites on Ikaria are of greatest importance with regard to the prehistory of the Aegean basin. No further sites of this period have been recognized to date in the Eastern Aegean or on the coast of Asia Minor. Undeniably, further sites of the same period must have existed on other islands in the Aegean, but as a result from the rise of the sea level up to 40-50 meters (Lambeck, 1996), most of them are no more accessible today as they are lying on the sea bottom. Nevertheless, research projects on the Mesolithic in the Aegean and in the Greek mainland are encouraging.

The similarities between the stone industries from Ikaria and Kythnos may lead to the assumption that an easier sea route had existed since the 9th millennium cal. BC connecting both sides of the Aegean along the chain of the Cycladic islands (Andros, Tenos, Mykonos, Ikaria, and Samos). Although between Mykonos and Ikaria lies the vast open sea (“Ikarion Pelagos”), the sight distance between the two islands as well as marine currents would facilitate seafaring. In fact, recent studies (Papageorgiou, 2008) have proved that the sea currents dominating during winter and summer in the islands of the Cyclades facilitate expeditions from Asia Minor to the western Aegean and vice versa.

However, the presence of Mesolithic sites in the Eastern Aegean cannot be considered as proof that this flourishing culture of the Aegean originated from the East. First, such early sites have not been detected along the coast of Asia Minor, and, second, the technology of the stone tools of the Mesolithic sites in the Aegean feature characteristics that originated in the West and not in the East. The specific Mesolithic culture of the Aegean with its Epigravettian tradition indeed was evidenced recently in the northern, central and southern Aegean, more particularly in the six important sites on Kythnos, in the Cyclops Cave on Gioura (Sampson, 2008 and 2011), the five sites on Ikaria and in Franchthi Cave in the Eastern Peloponnese (Perlès, 1990).

However, the relationship of the Mesolithic with the preceding Upper Palaeolithic is not yet clarified. There appears to be a more or less long lasting gap between both periods (600-700 radiocarbon years in Franchthi, 200-250 years in Cyclops Cave and 150-200 years in Sarakenos Cave). This may be indicative of a decrease of the local population but could also be exclusively connected with the specific use of caves. Yet, it will be possible to answer this question in the near future. C. Perlès (Galanidou and Perlès dir., 2003) who studied the stone material from Franchthi noted resemblance of the lithic industries and assumed cultural continuity since the Final Palaeolithic period. It is, however, more likely that the Mesolithic

residents stemmed from local populations, certainly not very numerous albeit existent. The gaps between the Palaeolithic and the Mesolithic are not proof that the region was unoccupied. The former residents may have changed settlement locations due to climate changes and/or radical economic transformations. After all, the Greek territory has never been unpopulated as its climate was suitable, providing food resources for the survival of foragers and hunters.

More generally, the scarcity of Mesolithic sites hitherto results not only from incomplete research, but also from great difficulty to recognize such sites because they are usually eroded and covered by overlying deposits. A large number of sites have been found near to the sea, often destroyed due to the rises of sea levels. The lack of careful observation during past surveys may also be a reason. Most likely the settlements were small, made of perishable, locally available materials. Because of the great mobility of the groups the camps would have been temporary, seasonal or periodical. If we accept that Mesolithic people were few, they probably had, according to C. Runnels (Runnels et al., 2005), the possibility to select the best regions for food procurement, aiming at the exploitation of coastal areas and entering the hinterland through gorges or fluvial valleys. Rock shelters or caves would have been ideal places, because they provided view of the coastal areas and the interior. Anyway, abundant discoveries made over the last years have completed the distribution map of Mesolithic sites (fig. 17). Moreover, they have shown that the arguments in favour of uninhabited areas in mainland Greece have been advanced on weak methodological bases.

Admittedly, on-going research focusing on the Mesolithic is making great progress, although there are still open questions on the interpretation of the Mesolithic society and economy in Greece. Certainly, Mesolithic layers still remain undiscovered and have not been excavated because of the overlying deposits. Consequently, cave excavations may offer new material and show the real importance of Mesolithic presence in each area. Moreover, it is essential to apply a strategy of research in combination with excavations in rock shelters or caves and at the same time to carry out intensive surface survey and study of the material by means of stratigraphy and absolute dating.

The identification of a Mesolithic site should not be based on typological assemblages including earlier and later periods but on the presence of specific Mesolithic tool assemblages exclusively (Runnels, 1995; Runnels et al., 2005). In our opinion, Thessaly is convenient for further research since the identification of numerous 7th millennium sites indicates the presence of Mesolithic sites that do not include earlier remains. Thus, Mesolithic sites are not necessarily located below Neolithic levels or in similar locations. On the contrary, research may also concentrate on environments suitable for hunters and food gatherers (Kotsakis, 2003). We take comfort from the fact that we begin to understand the methods of surveying in order to detect Mesolithic open air sites, especially in the Aegean basin.

204204

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

For the detection of sites in coastal areas it is essential to restore the coastline using terrestrial or submarine observations or geophysical methods. The rises of the sea levels of the Mediterranean Sea were rapid at the beginning of the Holocene (50 m in 10500 BP), while they stabilized towards the end of the Mesolithic. Consequently, new environments formed due to the continuous shift of the coast to the hinterland.

To sum up, the Greek Mesolithic, as it has been evidenced so far, was a period characterized by considerable regional differentiation and economic complexity. General differentiation emerges primarily between the islands of the Aegean and mainland Greece, where the question remains still open when analysing the issue more in detail. During the same period in mainland Greece a different way of life is recorded, more conservative in its choices. For example, the Mesolithic hunters of the Sarakenos Cave in the Kopais plain used local limestone materials for the manufacturing of their

tools (Sampson et al., 2009). At the same time, the occupants of Franchthi Cave and Maroulas employ obsidian and grinding tools. Similarly, elsewhere in the Near East (Cayönü, Gobekli Tepe etc.) from the 9th millennium cal. BC onwards, domestication of animals already existed, while in other sites such as Çatal Höyük in the 7th millennium cal. BC people still hunted wild animals. Equally, in the southern Syro-Palestinian region domestication is evidenced later, between 7200 and 5500 cal. BC (Horwitz, 1993), and in the region of the Black Sea considerably later, at approximately 6000 cal. BC.

Important differences can be identified among the Aegean Mesolithic sites, as some of them are closer to the stage of production by contrast to others still exclusively practicing hunting and gathering. Among the former, variants in the application of domestication practices exist with regard to the preference of distinct animals, or plants, as well as variants with regard to the treatment and the typology of stone tools, and to settlement and environment choices.

The important discoveries made during recent excavations in the Aegean indicate primary achievements such as incipient animal and plant domestication. On the one hand, these latter presume the possible existence of direct or indirect connections between the local populations and Eastern groups and, on the other hand, the possible existence of cases of local domestication triggered by particular economic and social habitats and land use. Unfortunately, the theories of the “demic diffusion” (Ammerman and Cavali-Sforza, 1984) have hindered the formulation of alternative theories that could identify the local processes contributing to the transition from hunting and gathering to food production without rejecting the participation of the Near East, placing it however on a different level.

The opposed view initially expressed several decades ago by D. Theocharis (Theocharis, 1967 and 1973) and afterwards developed by K. Kotsakis (Kotsakis, 2000 and 2003), and others (Halstead, 1993; Sampson, 2005, 2006 and 2008a; Seferiades, 2007; Zvelebil dir., 1986) provided the theoretical framework to cast doubt on the theory of the “cradle” importing “neolithization”: the progressive adoption of production economy by the local populations of the Greek area with or without the help of the knowledge they acquired through networks of contacts (cultural diffusion). One wonders why foreign prehistorians instead of applying current processual approach, entrenched themselves in the conservative perception of the “demic diffusion” and, at best, assumed indigenist processing: C. Perlès (1990) excludes local development for Thessaly, but not for Franchthi, while J. Hansen (1991), without abandoning the idea of imported Neolithic, pointed out the need for further archaeobotanic analyses in the pre-neolithic sites of Greece.

THE AEGEAN MESOLITHIC AS A STAGE OF PROTO- NEOLITHIZATION

The Aegean Mesolithic may also be considered as being a hybrid culture and a period of experimentation with regard to food production. Elements of proto-neolithization emerging in the Aegean during the Mesolithic may indicate, on the one hand, the existence of a centre of neolithization comparable to the one on Cyprus, and, on the other hand, sea routes transporting and diffusing ideas to the western direction (Sampson et al., 2010). However, the centres of origin currently recorded place the Aegean islands inside a new framework. The Aegean basin is upgraded from the former regional area to a centre of origin on the map of polycentric neolithization (Sampson and Katsarou, 2004; Sampson, 2005 and 2006), which gradually replaces the one and unique “cradle” in the Eastern Mediterranean related to the theory of demic diffusion. A social area, open and creative, emerges in the islands that does not have neither the attribute of the exclusive receptor (demic diffusion theory), nor of the isolated and introvert model, notably the extreme “indigenist Neolithic” proposed by M. Seferiades (Seferiades, 2007).

A “model” of an Aegean area inhabited for roughly 2000 years by groups living in a mixed Mesolithic/Neolithic stage, familiar with the sea, navigation and geography, and participating into common networks of exchange of raw materials and sharing common technological types seems to become prevalent. This cultural diffusion is based on the Mesolithic sea routes between the Aegean islands and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic seafaring in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially between Anatolia, the Levantine coast, and Cyprus. It is very likely that these maritime communication and contacts were not unilateral but reciprocal and diffused into both directions, i.e. from the East to the West and vice versa (fig. 18).

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

205205

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

Fig. 18: Probable Mesolithic and PPN sea routes. Routes maritimes potentielles durant le Mésolithique et le PPN.

AMMERMAN, Α. J.- CAVALI-SFORZA L. L. (1984) - Measuring the rate of spread of early farming in Europe, Man 6, p. 674-788.

GALANIDOU N., PERLÈS C. dir. (2003) - The Greek Mesolithic. Problems and perspectives, London, British School of Athens, 224 p.

GUILAINE J., BRIOIS F. (2001) - Parekklishia Shillourokambos. An early Neolithic site in Cyprus, in S. Swiny S. (dir.), The Earliest Prehistory of Cyprus. From Colonization to Exploitation, Boston, Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute (Monograph Series vol. 2), p. 37-53.

ΗELMER D. (1994) - L’animal maitrisé 8500 av. J.-C, in Les chasseurs de la préhistoire, Paris, Errance, p. 68-78.

HALSTEAD P. (1993) - The Development of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Greece: When, How, Who and What?, in D. R. Harris (dir.), The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, London, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 296-309.

HANSEN J. (1991) - Excavations at Franchthi Cave, Greece. Fasc. 7. The palaeoethnobotany of Franchthi cave, Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 280 p.

HONEA K. (1975) - Prehistoric remains on the island of Kythnos, American Journal of Archaeology, 79, p. 277-279.

HORWITZ L.K. (1993) - The development of ovicaprine domestication during the PPNB of the Southern Levant, in H. Buitenhuis, A.T. Clason (dir.), Archaeozoology of the Near East, Proceedings of the first international symposium on the archaeozoology of southern Asia and adjacent areas. Leiden, Universal Book Services, p. 27-36.

KACZANOWSKA M., KOZLOWSKI J. (2008) - Chipped stone artifacts in A. Sampson (dir.), Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol 1, Philadelphia, INSTAP, Monograph Series, 169-179 p.

ΚOTSAKIS Κ. (2000) - The beginning of the Neolithic in Greece, in Ν. Κyparissi-Αpostolika (dir.), Theopetra Cave, Twelve years of excavations (1987-1998), Athens, Institute for Aegean Prehistory, 2000. p. 173-177.

ΚOTSAKIS Κ. (2003) - From the Neolithic side: Neolithic Interface, in N. Galanido, C. Perlès (dir.), The Greek Mesolithic. Problems and perspectives, London, British School of Athens, p. [My p217-221.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

206206

The MesoliThic of The Aegean basinAdAmAntios sAmpson

KOTSAKIS K., ANDREOU S. (1999) - Surface survey in Langadas. Pre-neolithic and Early Neolithic sites, Archaeological work in Macedonia and Thrace, 13.

KOUMOUZELIS M., KOZLOWSKI J. K., NOWAK M., SOBCZYK K., KACZANOWSKA M., PAWLIKOWSKI M., PAZDUR A. (1996) - Prehistoric settlement in the Klissoura Gorge, Argolid, Greece (excavations 1993-1994), Préhistoire Européenne, 8, p. 143-173.

KOUMOUZELIS M., KOZLOWSKI J. K., GINTER B. (2003) - Mesolithic finds from Cave 1 in the Klissoura Gorge, Argolid, in N. Galanido, C. Perlès (dir.), The Greek Mesolithic. Problems and perspectives, London, British School of Athens, p. 113-122.

ΚYPARISSI-APOSTOLIKA N. (2003) - The Mesolithic in Theopetra Cave: new data on a debated period of Greek prehistory, in N. Galanido, C. Perlès (dir.), The Greek Mesolithic. Problems and perspectives, London, British School of Athens, p. 189-198.

LAMBECK K. (1996) - Sea-level change and shore-line evolution in Aegean Greece since Upper Palaeolithic time, Antiquity, 70, p. 588-611.

LASKARIS N., SAMPSON A., MAVRIDIS F., LIRITZIS I., (2011) - Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene seafaring in the Aegean: New obsidian hydration dates employing the novel SIMS-SS method, Journal of Archaeological Science, 38, 2475-2479.

LIEBERMAN D. E. (1998) - Natufian ‘sedentism’ and the importance of biological data for estimating reduced mobility, in T. R. Rocek, O. Bar-Yosef (dir.), Seasonality and Sedentism. Archaeological Perspectives from Old and New World Sites, Cambridge, Peabody Museum Bulletin 6, p. 75-92.

MARKOVITS A. (1933) - Die Zaimis-Höhle (Kaki Skala), Megaris, Griechenland. Mitteilung: Lage, Morphologie, Genesis und Höhleninhalt, Speleologisches Jahrbuch XIII/XIV, 1923-33, p. 133-146.

MASSETI Μ. (1998) - The prehistorical diffusion of the Asiatic mouflon, Ovis gmelini Blyth, 1841, and of the bezoar, Capra aegagrus Erxleben, 1977, in the Mediterranean region beyond their natural distributions, in E. Hadjisterkotis (dir.), Proceedings of the 2nd Symposium on Mediterranean Mouflon, Nicosia, Game Fund., p. 1-19.

MOUNDREA-AGRAFIOTI A. (1992) – Agios Petros Kyra-Panagias. Stoiheia tis lithotechnicas tou laxemenou lithou, in Diethnes sinedrio gia tin Archaia Thessalia sti mnimi tou Dimitri P. Theochari, Athens, p. 191-201.

MOUNDREA-AGRAFIOTI A. (2011) - The Mesolithic and Neolithic bone implements, in A. Sampson (dir.), Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol II: Dietary resources and Palaeoenvironment, Philadelphia, INSTAP, Monograph Series, p. 3-52.

MYLONA D. (2010) - Mesolithic fishers at Maroulas, Kythnos: the fish bones, in A. Sampson, M. Kaczanowska, J. Kozlowski (dir.), Τhe prehistory of the island of Kythnos and the Mesolithic settlement at Maroulas, Krakow, Polish Academy of Sciences and Arts and University of the Aegean, p. 151-162.

MYLONA D. (2011) - Fish vertebrae, in A. Sampson (dir.), Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol II: Dietary resources and Palaeoenvironment, Philadelphia, INSTAP, Monograph Series, p. 237-266.

NAFPLIOTI A. (2010) - The Mesolithic occupants of Maroulas on Kythnos: skeletal isotope signatures of their geographic origin, in A. Sampson, M. Kaczanowska, J. Kozlowski (dir.), Τhe prehistory of the island of Kythnos and the Mesolithic settlement at Maroulas, Krakow, Polish Academy of Sciences and Arts and University of the Aegean, p. 207-215.

PAPAGEORGIOU D. (2008) - Sea routes in the Prehistoric Cyclades, in N. Brodie, J. Doole, G. Gavalas, C. Renfrew (dir.), Horizon: A Colloquium on the Prehistory of the Cyclades, Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, p. 9-11.

PERROT J. (1966) - Le gisement Natoufien de Mallaha, Israel, L’ Anthropologie, 70, p. 437-483.

PERLÈS C. (1990) - Excavations at Franchthi Cave, Greece. Fasc. 5. Les industries lithiques taillées de Franchthi (Argolide, Grèce). Tome. II. Les industries du Mésolithique et du Néolithique initial, Indiana University Press, 288 p.

POULIANOS N. (2010) - Mesolithic palaeoanthropological remains from Kythnos, in N. Brodie, J. Doole, G. Gavalas, C. Renfrew (dir.), Horizon: A Colloquium on the Prehistory of the Cyclades, Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, p. 179-206.

POWELL J. (2011) - Non-vertebral fish bones, in A. Sampson (dir.), Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol II: Dietary resources and Palaeoenvironment, Philadelphia, INSTAP, Monograph Series, p. 151-236.

ROSENBERG M. (1996) - A preliminary description of the lithic industry from Hallan Chemi, in S.K. Kozlowski, H. G. Gebel (dir.), Neolithic chipped stone industries of the Fertile Crescent and their contemporaries in adjacent regions, Berlin, ex oriente.

ROSENBERG M. (1999) - Hallan Cemi, in M. Ozdogan, N. Başgelen (dir.), Neolithic in Turkey, The cradle of civilization, Istanbul, p. 25-34.

RUNNELS C. N. (1995) - Review of Aegean Prehistory: the Stone Age of Greece from the Palaeolithic to the advent of the Neolithic, American Journal of Archaeology, 99, p. 699-728.

RUNNELS C. N. (2009) - Mesolithic sites and surveys in Greece: A case study from the Southern Argolid, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 22,1, p. 57-73.

RUNNELS C. N. et al. (1999) - Human settlement and landscape in the Preveza region, Epirus, in the Pleistocene and Early Holocene, in G.N. Bailey, E. Adams, E. Panagopoulou, C. Perlès, K. Zachos (dir.), The Palaeolithic Archaeology of Greece and Adjacent Areas, Proceedings of the ICOPAG Conference, Ioannina, September 1994, British School at Athens, London (Studies 3), p. 120-129.

RUNNELS C. N.,VAN ANDEL T.H. (2003) - The Early Stone Age of the Nomos of Preveza: landscape and settlement, in J. Wiseman, K. Zachos (dir.), Landscape Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece, Princeton, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, p. 47-134.

RUNNELS C. N., PANAGOPOULOU E., MARRAY P., TSARTSIDOU G., ALLEN S., MULLEN K., TOURLOUKIS E. (2005) - A Mesolithic landscape in Greece: testing a site-location model in the Argolid at Kandia, Journal of Mediterranean Achaeology, 18, 2, p. 259-285.

SAMPSON A. (1987) - The Neolithic period in Dodecanese, Athens, Archaeologikon Deltion Monographs 35, 196 p.

PSON A. (1988) - The Neolithic settlement at Yali of Nissyros, Athens, Euboïki archaiophilos etaireia, 264 p.

SAMPSON A. (1996) - New evidence for the Mesolithic period in Greece, Archeologia and Technes, 61, p. 46-51.

SAMPSON A. (2005) - Early productive stages in the Aegean Basin from 9th to 7th mill BC, in C. Lichter (dir.), How Did Farming Reach Europe? Anatolian-European Relations from the Second Half of the 7th Through the First Half of the 6th Millennium Cal. BC, Proceedings of the International Workshop, Istanbul 2004, Istanbul, Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Istanbul, BYZAS 2, p. 131-141.

La diffusion par Chypre, L’ÉgÉe et L’adriatique

the diffusion by Cyprus, eagean and adriatiC

207207

Le Mésolithique du bassin Égéén

SAMPSON A. (2006) - Prehistory of the Aegean, ed. Atrapos, Athens, 259 p.

SAMPSON A. (2008a) - Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol 1, INSTAP, Monograph Series, Philadelphia, 255 p.

SAMPSON A. (2008b), The Neolithic and Bronze Age Occupation of the Sarakenos Cave at Akraephnion Boeotia, Greece. Vol I. The Neolithic and the Bronze Age, University of the Aegean and Polish Academy, Athens, 549 p.

SAMPSON A. (2010) - Mesolithic Greece, Athens, ed. Ion.

SAMPSON A dir. (2011) - Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol II: Dietary resources and Palaeoenvironment, Philadelphia, INSTAP, Monograph Series, 395 p.

SAMPSON A., KACZANOWSKA M., KOZLOWSKI J. K. (2008) - The first Mesolithic site in the eastern part of the Aegean Basin: excavations into the site Kerame I on the Island of Ikaria, Annual of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2008, p. 321-329.

SAMPSON A., KACZANOWSKA M., KOZLOWSKI J. K. (2009) - Sarakenos Cave in Boeotia from Palaeolithic to the Early Bronze Age, Eurasian Prehistory, 6 (1), p. 1-33.

SAMPSON A., KACZANOWSKA M., KOZLOWSKI J. (2010) - Τhe prehistory of the island of Kythnos and the Mesolithic settlement at Maroulas, Krakow, Polish Academy of Sciences and Arts and University of the Aegean, 215 p.

SAMPSON A., KATSAROU S. (2004) - Cyprus, Aegean and the Near East during the PPN, Neo-lithics, 2/2004, p. 13-15.

SAMPSON A., KOZLOWSKI J., KACZANOWSKA M. (1998) - Εntre l’ Anatolie et les Balkans: Une séquence mésolithique-néolithique de l’île de Youra (Sporades du Nord), in M. Otte (dir.) - Préhistoire de l’Anatolie, Genèse de deux mondes, Université de Liège, ERAUL, p. 125-142.

SAMPSON A., KOZLOWSKI J., KACZANOWSKA M., GIANNOULI V. (2002) - The Mesolithic settlement at Maroulas, Kythnos, Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 2, p. 45.

SEFERIADES M. (2007) - Complexity of the processes of Neolithization: Tradition and modernity of the Aegean world at the dawn of the Holocene period (11–9 kyr), Quaternary International, 167, p. 177–185.

SORDINAS A. (1969) - Investigations of the prehistory of Corfu, dating 1964-1966, Balkan Studies, 10, p. 393-424.

SORDINAS A. (2003) - The Sidarian: maritime Mesolithic non-geometric microliths in Western Greece, in N. Galanido, C. Perlès (dir.), The Greek Mesolithic. Problems and perspectives, London, British School of Athens, p. 89-98.

THEOCHARIS T. (1967) - He Ayge tes Thessalikes proïstorias, Volos, Thessalika meletemata, 1, 186 p.

THEOCHARIS T. (1973) – Neolithic Greece, Athens, National bank of Greece, 356 p.

TRANTALIDOU K. (2003) - Faunal remains from the earliest strata of the Cave of Cyclops, in N. Galanido, C. Perlès (dir.), The Greek Mesolithic. Problems and perspectives, London, British School of Athens, p. 143-172.

TRANTALIDOU K. (2010) - Dietary adaptations of coastal people in the Aegean Archipelago during the Mesolithic period: The macrofauna assemblages of Maroulas on Kythnos, in A. Sampson, M. Kaczanowska, J. Kozlowski (dir.), Τhe prehistory of the island of Kythnos and the Mesolithic settlement at Maroulas, Krakow, Polish Academy of Sciences and Arts and University of the Aegean, p. 163-178.

TRANTALIDOU K. (2011) - From Mesolithic fisherman and bird hunters to Neolithic goat herders: The transformation of an island economy in the Aegean, in A. Sampson (dir.), Τhe Cyclops Cave on the island of Youra, Greece. Mesolithic and Neolithic networks in the Northern Aegean Basin, vol II: Dietary resources and Palaeoenvironment, Philadelphia, INSTAP, Monograph Series, p. 53-150.

SIMMONS A. H. (1999) - Faunal extinction in an island society: Pygmy hippopotamus hunters in Cyprus, New York, Springer, 382 p.

UERPMANN H. P. (1981) - The major faunal areas of the Middle East during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene, in J. Cauvin, P. Sanlavile (dir.), Préhistoire du Levant, Paris, Édition du CNRS, p. 99-106.

VALLA F. R. (1998) - Natufian seasonality: A Guess, in T.R. Rocek, O. Bar-Yosef (dir.), Seasonality and Sedentism. Archaeological Perspectives from Old and New World Sites, Cambridge, Mass, p. 93-108.

ZVELEBIL M. dir. (1986) - Hunters in transition. Mesolithic societies of temperate Eurasia and their transition to farming, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 194 p.