Wyspiański's The Wedding: Three Case Studies

Transcript of Wyspiański's The Wedding: Three Case Studies

49

WYSPIAŃSKI’S THE WEDDING: THREE CASE STUDIES

Tony H. Lin

Stanisław Wyspiański’s symbolist drama The Wedding (Wesele) has been a prism for gauging Polish self-perceptions ever since its first production at the Miejski Theatre in Cracow in 1901. Based upon the wedding between the author’s friend, poet Lucjan Rydel, and his peasant bride Jadwiga Mikołajczyk, the play has been interpreted in different, sometimes opposing ways. In 1905 when his friend Ludwik Solski wanted to take The Wedding to the Russian partition for consideration to be staged, Wyspiański refused and told Solski that the play “accused Poles of spiritual torpor and inability to act.”1 Wyspiański’s own explication of his play, that it criticizes contemporary Polish society for its passivity, is in diametric opposition to that of his contemporary censors, who considered the play a patriotic and an incitement of the Poles to fight for their own freedom. I propose to look at three case studies from the beginning of the twentieth century, mid-century, and the beginning of the twenty-first century that show how the play as well as its reception can be manipulated to fit the social and political demands of the time.

Case Study No. 1: Partitioned Poland before 1918, Cracow Premiere,Teatr im. Juliusza Słowackiego, March 16, 1901

By all accounts, The Wedding caused a sensation when it premiered in Cracow, then part of the Austrian Empire. It was staged twenty-one times during the 1900–1901 season, and an additional twenty-seven performances occurred by the end of the 1903 season.2 The Wedding was relatively popular, but it was not a blockbuster by any means in terms of ticket sales.3 Most reviews of the premiere devote substantial space to explaining the plot and idea of the play.4 Several critics point out that many audience members did not understand what the play was about:

No one in the theatre understood the drama. This was supposed to change after the premiere, but it was the atmosphere of a great theatrical event that had an effect, rather than a basic understanding

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 31, No. 250

of the work. Parallel to the audience’s lack of understanding, the majority of reviewers wrote utter nonsense, and even a special literary conference was put together, in which lecturers . . . explained to the audience what the play was about.5

The linguistic peculiarities of the play did not prevent The Wedding from arousing strong emotions at the premiere. For many, the sound of the words alone was equally, if not more, important than their semantic meaning. The Wedding was a poetic drama, as was indicated on the advertising poster of the premiere: “Drama in three acts in verse by Stanisław Wyspiański” (emphasis mine). Wyspiański wrote his dramas in verse, following in the poetic tradition of Mickiewicz and Słowacki.6

In the censored version given to the theatre one day before the premiere, sixty-nine lines were censored.7 The censors seemed eager to erase any memory or trace of Polish statehood, including its history and culture, because the deleted lines depict Poland’s location, religion, and the Galician slaughter of 1846.8 In 1846, the peasants rebelled against the gentry in the Austrian partition, killing about one thousand noblemen. The Austrian government ostensibly used the uprising to eliminate nationalistic Polish nobles who were plotting an uprising against Austria. The Groom in the play says: “We have forgotten all of [the 1846 Uprising] / they sawed my grandfather in two / we have forgotten all of that.” The Austrian censorship did not take any chances and quickly erased the reference to the slaughter from the play.

In another scene, where enemies are specified in the phrases “against the Muscovites” and “beat the Muscovites,” the name is replaced by a more general reference to the “enemy.” The fact that the line “against the Muscovites” was deleted in the Austrian partition may seem curious, but it seems logical that the censors would suppress references to any of the three occupying powers. Furthermore, in act 3, scene 10, the line “they want to take up arms” is deleted. Moreover, the play’s conclusion lacks Jasiek’s shouting “Grab horses, / grab weapons, grab weapons. / Wawel Castle awaits you!” As demonstrated by this case study, censors deleted lines that they could easily grasp without considering the play’s subtleties. In imagining only one interpretation of The Wedding, they ignored the fact that its irony could be equally subversive.

In contrast to the Austrian partition, productions of The Wedding were banned altogether in Russian-occupied territory and did not emerge

51

until January 1906 in Łódź. Similarly, the Prussian court believed that The Wedding fomented “public incitement of different classes of people to acts of violence” and consequently banned the production of the play.9 We can see that censorship worked quite differently in the three partitions, because the internal situation within each partition was different.

The 1905 Revolution in Russia led to less censorship of the theatre in Poland.10 The preemptive censorship was thus lifted, and The Wedding was allowed to be staged in Warsaw for the first time in 1906. However, after only two performances, the censor Vladimir Ivanovsky banned the play. He stated:

This play, as is the majority of Wyspiański’s works, has symbolic character. The play introduces the contemporary dreary condition of the Polish society caused by its complete indifference with regards to the restoration of Poland. Everything is limited to loud words, and no one thinks about working for the common good of realizing cherished Polish ideals. The higher layer of the Polish society already showed a hundred years ago what it’s worth, selling its own fatherland to Russians; one could have expected something from the peasants, who produce heroes from their own milieu such as Głowacki,11 but presently the hope is bad for them; and they let go the golden horn, which was to awaken the society stuck in opportunism. On account of the work’s content, I would propose forbidding it on the basis of the Point 4 No. 2 of the Censorship and Printing Act.12

At no point does Ivanovsky mention that The Wedding stirs Poles to revolt; instead, he verbalizes the criticism of Polish society that Wyspiański implies in the text. The phrase “no one thinks about working for the common good of realizing cherished Polish ideals” suggests that, in Ivanovsky’s view, The Wedding is not a call to arms. Rather, The Wedding points out the problem of the passivity of Polish society. Would Ivanovsky have allowed The Wedding to be staged if the golden horn had been found and a revolution taken place? Ivanovsky’s example shows that censors have a variety of reasons for banning works of art. While Prussian censors believed The Wedding would cause unrest and incite Poles to rebellion, the Russian censor thought that The Wedding would have the opposite effect. Nevertheless, the outcome—The Wedding not being staged—was the same in the Prussian and in the Russian partitions.

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 31, No. 252

Poster for the World Premiere of The Wedding, Teatr im. Juliusza Słowackiego, March 16, 1901

53

Case Study No. 2: Second World War, Lwów, Państwowy Polski Teatr Dramatyczny (PPTD), April 14, 1945

World War II brought drastic changes to the landscape of Polish theatre. Most theatre buildings were destroyed, and many theatre workers, writers, directors, actors, and critics perished in the war, resulting in a shortage of capable cast members.13 However, wartime theatrical activity did not come to a standstill. Even though there were no official performances of The Wedding between 1939 and 1944, theatre lovers and actors managed to establish clandestine theatres and staged at least two known performances of The Wedding in private homes: first in Cracow in 1941 and second in Warsaw in 1944. The war also saw The Wedding performed in unusual places, such as in barracks and concentration camps.14

Polish theatres reopened in Lwów on August 18, 1944, after the retreat of the Germans and the establishment of the Soviet administration. Even though the city had been liberated by the Soviet army, the war was not yet over, and the political sensitivity of the period had direct influence on the theatre’s repertory. A meeting to address issues of Polish theatre in newly liberated territories took place in Moscow on October 26, 1944. The Polish Communist Committee on Artistic Matters (Komitet do Spraw Sztuki) stated: “Polish dramaturgy should take its proper place on Soviet stages, and above all on the stages of war fronts, serving units of the Red Army that are liberating the neighboring Slavic nations.”15 When this message reached the theatre director, Bronisław Dąbrowski (1903–1992), it became clear that there would be no autonomy in theatre. In Dąbrowski’s memoir, published more than thirty years later, he wrote:

Eclectic repertory of the theatre caused by specific circumstances did not allow for exact formulation of our stage profile. Undoubtedly the main role fell upon actors, and the directors were mainly putting pressure on actors’ interpretation within a realistic framework. No one dreamt about experiments and autonomy of theatre at the time.16

The eclectic recommended list includes both Polish and Soviet works, such as Wojciech Bogusławski’s folkloristic musical comedy Cracovians and

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 31, No. 254

Highlanders (Krakowiacy i Górale, 1794), Aleksander Fredro’s comedy Maidens’ Vows (Śluby panieńskie, 1832) and an adaptation of Nikolai Ostrovsky’s socialist-realist novel How the Steel Was Tempered.17 Since the list was only recommended, there was room for negotiation. Dąbrowski managed to include The Wedding in the 1944–1945 season but had to change the content of the play dramatically.

Dąbrowski’s task was to satisfy a public that was yearning for the return of Polish culture. In accordance with the Communist committee resolution, Dąbrowski decided to change one fundamental aspect of the plot: the loss of the golden horn. In this production, the golden horn is found and thus the intelligentsia and peasants could unite in the face of a common enemy. Dąbrowski in his memoir wrote: “In the current situation it was necessary to take the socio-political problems into consideration, to choose from Polish classics and foreign works those that are appropriate and suitable to be made more contemporary.”18 The phrase “to make something contemporary” (uwspołcześnienie) means that elements potentially offensive to the Russians were taken out. For example, the Black Madonna icon was removed,19 and reference to the 1846 Galician slaughter was taken out. The 1945 Lwów production is an example of how a play can be distorted for political purposes at the expense of the play’s integrity and even coherence.

The production’s optimism was intended to cheer up the audience members and raise their spirits so that they would continue fighting the Germans, who had deprived them of their freedom. The Romantic fervor of fighting matched the objective of this production perfectly. The irony, of course, is that Poles did not regain their freedom under a Soviet-imposed regime, and the production simply became a case of wishful thinking and Soviet propaganda.

Case Study No. 3: Twenty-First Century Poland, Katowice,Teatr Śląski (im. Stanisława Wyspiańskiego), October 6, 2007

For more than a hundred years, the production history of The Wedding has reflected the inherent complexities of the play and also the powerful impact of historical vicissitudes on its reception; directors have had to grapple with the text and its relevant performance traditions that began with Wyspiański’s own staging. The 2007 Katowice production deserves our attention for several reasons. First, the Katowice production has a connection to the 1945 Lwów

55

Bronisław Dąbrowski, director of The Wedding, Państwowy Polski Teatr Dramatyczny (PPTD), Lwów, 1945

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 31, No. 256

production. Due to the shifting border, Polish actors in Lwów had to move to Katowice permanently, where they staged The Wedding for the post-war inaugural performance on October 6, 1945, directed by Dąbrowski. Second, since the Polish Sejm declared the year 2007 the Year of Wyspiański, there was an unusual amount of press attention paid to the numerous plays staged as part of the festive activities. The director of the Katowice production was Rudolf Zioło, who had directed The Wedding two years earlier in Teatr Wybrzeże in Gdańsk. Zioło spoke extensively in the press about how he hoped that the production would embody a contemporary understanding of the play.

During International Theatre Day, the Minister of Culture and National Heritage, Kazimierz Michał Ujazdowski, designated the year 2007—the centenary of Wyspiański’s death—the Year of Wyspiański. Ujazdowski’s decision, supported by the President Lech Kaczyński, resulted in five million złoty of funding.20 As a result, Wyspiański’s plays, and particularly The Wedding, received renewed attention from directors and the general public alike. In Ujazdowski’s speech announcing the Year of Wyspiański, he states:

Wyspiański was the first of the twentieth-century playwrights who struggled with the problem of Polishness. He desired the collective bond of Poles to grow out of the internal freedom of each of the citizens, and patriotism to be an effect of spiritual greatness of individuals. He posed an extremely difficult task for the audience: in order for one to deserve the dignity of being a Pole, one must become a genuine person.21

Ujazdowski’s understanding of Wyspiański’s life and works projects his own view and inextricably infuses politics into art. He does not use specific language, nor is it always clear what “internal freedom” means, but one clearly sees the rather one-sided and pro-Poland nature of his statement. Ujazdowski’s statement reflects his political affiliation, since he belongs to the Law and Justice (PiS) Party, which generally advocates nationalistic views and often expresses anti-European sentiments. Ujazdowski’s official statement raises the question with which I have been concerned: how Wyspiański has once again become a political vehicle, subject to manipulation and appropriation.

In 2007, The Wedding was staged in several large cities such as Cracow, Szczecin, and Katowice. In numerous reviews of recent productions of The

57

Wedding,22 a question frequently posed is how the play, which centers on the clash between peasants and intelligentsia in Wyspiański’s time, remains relevant to today’s Poland. As in the 1945 Lwów production, making Wyspiański contemporary remains a major concern in the twenty-first century. One journalist even asks, “Why should one play a relic (truchło)?”23 We can begin to answer the question by considering the fact that Wyspiański’s text remains open to widely divergent interpretation. Several directors have pointed out that their aim in new productions is to “decipher the meaning of Wyspiański’s text.”24 Part of “deciphering” the text involves engaging both with Wyspiański’s text and its associated legend, but in the process also infusing one’s own belief and understanding of the play.

In many ways, The Wedding provided an ideal platform for Zioło, who had earlier stated: “Theatre should irritate, arouse objection, pose difficult questions and provoke bitter answers.”25 Zioło has also expressed his pessimism with Poland in multiple interviews. For example, in an interview for the Katowice production, Zioło describes the political situation in overwhelmingly negative terms (time of chaos, time of poaching in national ideas, etc.) and even recalled the famous phrase by Jan Nowak-Jeziorański: “The biggest threat for Poland is Poles.”

In Aleksandra Czapla-Oslislo’s review of the play, published under the title “Association of Dead Patriots” two days after her interview with the director, she points out several unusual characteristics about this production: there is no celebratory atmosphere and the lack of collectivity (zbiorowość) is overwhelming. Wyspiański’s lines are recited standing; actors never sit at the dinner table all at the same time, thus not allowing the feast to occur. In another review titled “Nie-weselmy się…” (a word play that is perhaps best rendered by “We are not merry…”), journalist Marta Odziomek seconds Czapla-Oslislo’s observation that the actors did not smile or show any sign of happiness at the wedding party. Furthermore, the actors did not converse, but talked to the world “with hatred for other people.”26 Odziomek also points out that the realistic first act—where the guests ostensibly celebrate and enjoy themselves—lacks a lively tempo. Odziomek ends her review by defending Poland against Zioło’s indirect criticism by stating “today is not all that bad.”27

By now it should strike the reader that the shifting interpretations and understandings of The Wedding continue to the present. While Minister Ujazdowski proudly links Wyspiański with patriotism, director Zioło takes a

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 31, No. 258

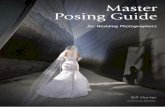

Poster for The Wedding, directed by Rudolf Zioło, Teatr Śląski (im. Stanisława Wyspiańskiego), Katowice, 2007

59

decidedly more pessimistic stance that is perhaps not only the genuine message conveyed by The Wedding but also an attack on the contemporary political situation in Poland. When we look at the promotional poster, designed by Piotr Pągowski, we see the Polish eagle with the Solidarity, European Union, and Holy Mary Mother of Jesus Christ (the symbol to the right of the tie) lapel pins, the latter being a clear reference to Lech Wałęsa, who frequently wears it. The Polish eagle is shown wearing a jester’s hat and tied by a rope, the red/white color of which suggests the Samoobrona (Self-Defense) Party, then headed by Andrzej Lepper.28 Odziomek’s review makes reference to the poster, describing it as “humorous, but at the same time provoking deeper thought.” The rich allusions of the poster force one to come to terms with both the past and the present and offer no joyous vision of the future. Even though Zioło’s staging of The Wedding takes place more than a hundred years after Wyspiański’s 1901 premiere, the productions are bookends. The inability to unite and the lack of social solidarity among Poles remain relevant in the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgment: I warmly thank David Frick and Anna Muza for their guidance and thoughtful comments throughout my research for this project

NOTES

1. See Alicja Okońska, Stanisław Wyspiański (Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1971), 292. With a few exceptions where I provide the original Polish, I have translated the quotes in this paper. 2. As quoted in Aniela Łempicka, “Wesele” we wspomnieniach i krytyce (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1961), 46. 3. Dziady, Kordian, and Faust were more popular than Wesele in terms of ticket sales. See Jan Michalik, “O premierze Wesela inaczej,” in O teatrze i dramacie, ed. Edward Krasiński (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1989), 142. The article states that The Wedding’s popularity may have been exaggerated as an advertising tactic. 4. See, for example, Adolf Neuwert-Nowaczyński’s “Wesele,” as quoted in Adam Grzymała-Siedlecki, O twórczości Wyspiańskiego (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1970), 295. 5. Jerzy Got, Stanisław Wyspiański: “Wesele,” tekst i inscenizacja z roku 1901 (Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1977), 287–288. 6. Though Wyspiański has been called the “new national bard,” his relationship with the Romantic bards is complex, often ambivalent. On the one hand, Wyspiański revered them for tackling the question of nationhood. On the other hand,

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 31, No. 260

he also attacked his predecessors’ inability to unite and mobilize the masses in a joint fight against the enemy. In The Wedding, one can see the ways in which Wyspiański both paid tribute to and ironized the work of his Romantic predecessors. 7. Rafał Węgrzyniak, Wokół “Wesela” Stanisława Wyspiańskiego (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1991), 21. 8. See Leon Płoszewski’s „Dodatek Krytyczny,” in Stanisław Wyspiański, Dzieła zebrane Vol. 4, 289–292. 9. Węgrzyniak, 22. 10. Ibid., 24. 11. Here Ivanovsky refers to Wojciech Bartosz Głowacki, a peasant famous for fighting in the Kościuszko Uprising against Russians in 1794. Głowacki is the subject of a painting “Bitwa pod Racławicami” by Jan Matejko, Wyspiański’s teacher. 12. See Henryka Secomska, Akta cenzury (Warsaw: Redakcja Pamiętnika Teatralnego, 1966). 13. Kazimierz Braun, A Concise History of Polish Theatre (Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2003), 197. 14. In the barracks outside of Poznań and in the Gross-Rosen and Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camps. See Diana Poskuta-Włodek, Co dzień powtarza się gra... (Kraków: Państwowy Teatr im. J. Słowackiego, 1993), 163–164. 15. Bronisław Dąbrowski, Na deskach świat oznaczających (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1977), 181–182. 16. Ibid., 184. 17. Ibid., 182. 18. Ibid., 181. 19. The famous icon of Black Madonna of Częstochowa (Matka Boska Częstochowska) is believed to have miraculously saved the monastery of Jasna Góra. The icon is Poland’s holiest relic and one of the country’s national symbols. 20. However, as Jacek Popiel points out, there was no effort to promote Wyspiański internationally. See interview with Wacław Krupiński in Dziennik Polski (November 29, 2007). 21. See http://www.gim3.net/news.php?readmore=59 (last accessed December 13, 2009). 22. See, for example, Mirosław Baran in Gazeta Wyborcza (June 16, 2005). 23. Roman Pawłowski in Gazeta Wyborcza (June 20, 2005). 24. See, for example, Monika Wasilewska’s interview with Ryszard Peryt in Gazeta Wyborcza, Łódź (March 23, 2007). 25. Rzeczpospolita, August 29, 1996. 26. Marta Odziomek, Dziennik Teatralny (October 11, 2007). 27. Ibid. 28. An interesting coincidence—Andrzej Lepper committed suicide in August of 2011 by hanging himself with a rope.

85

CONTRIBUTORS

DONATELLA GALELLA is a doctoral student in the Ph.D. Program in Theatre at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and a graduate teaching fellow at Brooklyn College. She serves as the production manager of PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, and she worked as an assistant editor of SEEP. She has published reviews in both journals.

TONY H. LIN is a Ph.D. Candidate in Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California–Berkeley, specializing in Polish and Russian literature. He received Fulbright and Kosciuszko Foundation grants to study and research in Poland for two years. He has presented and published papers on the relationship between music and literature and is currently writing a dissertation on the myth and appropriation of Chopin in Polish and Russian literature and culture.

SUZANA MARJANIĆ is on the staff of the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research in Zagreb, Croatia, where she pursues her interests in mythic topics in oral literature, animal studies, and theatre/performance art anthropology. Along with articles on the above topics, she has also published a book on Miroslav Krleža’s diary entries 1914–1921/1922 (2005) and has co-edited Cultural Bestiary (2007) with Antonija Zaradija Kiš, Folklore Studies Reader (2010) with Marijana Hameršak, and Mythical Anthology (2010) with Ines Prica.

OLGA MURATOVA is a native of Moscow, Russia. She teaches Russian Studies in the department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. She received her M.A. degree in Linguistics at the Moscow University of Linguistics and her Ph.D. in Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She is a regular contributor to SEEP.

CHRISTOPHER OLSEN worked as a professional actor and director of his own Off-Off Broadway theatre in the late 1970s, and has taught theatre at a number of universities and is currently teaching at the University of Puerto Rico. He has recently had a book published by Amazon.com on New York theatre of that era, Off-Off Broadway: The Second Wave: 1968–1980.