Wisdom, Sense Perception, Nature, and Philo’s Gender Gradient

Transcript of Wisdom, Sense Perception, Nature, and Philo’s Gender Gradient

Wisdom, Sense Perception, Nature, and Philo's Gender Gradient*

Sharon Lea Mattila The University of Chicago Divinity School

A panorama of female figures people the writings of Philo of Alexandria,1

ranging from the most sublime to the most debased.2 Amid this colorful array of characters are three female personifications of important conceptual constructs in Philo's world view—Wisdom (ή σοφία), sense perception (ή αϊσθησις), and Nature (ή φύσις). Like the concepts they represent, these figures have little in common, and it is hard to reconcile their heterogeneity with what Philo says about the "female" as a category in itself. Here the data become particularly contradictory and confusing, for Philo's gender categories are among the most rigid and consistently applied principles of his thought. My purpose here is to try to unravel this rather

*I would like to thank Alan Mendelson and David T. Runia for their very helpful comments

on this paper.

'The text of Philo used here is from Philo (trans. F. H. Colson: LCL; 10 vols.: London:

Heinemann; Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press. 1929-1965). with some modifica

tions made to the English translation. For the Quaestiones et solutiones in Genesin and Quaestiones

et solutiones in Exodum, mostly extant in Armenian. I have had to rely on the translation of

Ralph Marcus {Philo Supplements [LCL: 2 vols.: London: Heinemann: Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press. 1953]). 2On Philo's treatment of individual female biblical characters, such as Eve, Sarah. Rebekah.

Rachel, Leah, and others, as well as his description of contemporary women, see Dorothy Sly.

Philo's Perception of Women (BJS 209: Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1990). Judith Romney

Wegner's analysis ("The Image of Women in Philo" [SBLASP: Chico, CA: Scholars Press.

1982] 551-63) is unfortunately rather superficial.

8 9 2 ( 1 9 9 6 ) 1 0 3 - 2 9

104 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

glaring inconsistency between Philo's narrow perception of gender and the breadth of his female characterization as displayed by these three figures.

In order to approach this perplexing problem systematically, I have found it useful to introduce into my analysis a distinction that has become a basic paradigm in feminist criticism—the distinction between sex and gender. "Sex is a determination made through the application of socially agreed upon biological criteria for classifying persons as females or males."3 Gender has been more difficult to define, but is generally agreed to be primarily a socially and culturally determined construct—"a socially scripted dramatization of the culture's idealization of feminine and masculine natures."4

Throughout this essay, I shall place the words "female" and "male" in quotation whenever I mean them to refer to gender rather than to sexual categories.

The instances where Philo uses the terms "male" (το άρρεν γένος or ό ανδρείος) and "female" (το θήλυ γένος or ή προς γυναικών) 5 to refer to biological sexual distinctions are rare. The most striking example is his description of the sexually undifferentiated άνθρωπος of Gen 1:27. This archetypal άνθρωπος is "neither male nor female" (ούτ' άρρεν ούτε θήλυ); the male and female components merge as mirror images of each other into a sexless genus which, when differentiated, serves as the paradigm for both sexes.6 Philo applies the word "equality" (ίσότης) to such biological sexual differentiation, specifically with reference to the male and female reproductive functions.7 In addition, Philo offers a detailed cosmological classification system in which both women and men are placed squarely within the human category of rational, mortal beings, as distinct from irrational, mortal animals and rational, immortal heavenly bodies.8 As such, both women and men are understood to have a rational as well as irrational aspect.

3Candace West and Don H. Zimmerman, "Doing Gender,"' in Judith Lorber and Susan A.

Farrell, eds., The Social Construction of Gender (Newbury Park. CA: Sage, 1991) 14. 4Ibid.. 17. Like any attempt to categorize reality, this distinction is not without its prob

lems. Whether or not the social and the biological can be separated remains a point of conten

tion. The maximalist feminist perspective, which tends to valorize women's procreative and

nurturance proclivities, would be less inclined to separate these than would the minimalist

perspective, which stresses that women and men are more similar than they are different. 5 το θ ή λ υ γένος means literally "the female gender" and ή προς γ υ ν α ι κ ώ ν , the "wom

anly." Philo uses both these expressions, as well as variations of these, to refer to the category

"female," meaning much the same thing whenever he does. This is also true of το άρρεν

γένος, or "the male gender." and ό ανδρείος, or the "manly." and variations thereof. 6Philo Op mun 76, 134: compare Leg all 2.13. 7Philo Rer div her 164. 8Ibid., 137-40: schematic diagrams of this classification system are provided by Georgios

D. Farandos (Kosmos und Logos nach Philon von Alexandria [Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1976]

259) and Ursula Fruchtel {Die kosmologischen Vorstellungen bei Philo von Alexandrien [Leiden:

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 105

Unfortunately, Richard A. Baer makes altogether too much out of this anomalous treatment of the male and female in Philo, using it to back his hypothesis that "the male-female polarity in Philo's writings. . . does not function on a cosmic scale" and "is associated with the irrational part of the soul, not with the higher νους." 9 But the male-female polarity to which Baer refers is sexual, and is not the most fundamental "male"-"female" polarity underlying Philo's thought. As Baer correctly observes, Philo does indeed associate biological sexual differentiation with the irrational part of the soul. The rational part, the mind (ό νους), is indeed free of sexual differentiation and is in its purest form free of all differentiation, belonging to what Philo calls the "monad." But from the point of view of gender, Philo explicitly classifies the rational part of the soul as "male" and the irrational part as "female."10 Baer recognizes this pattern and calls it Philo's "second usage" of the categories male and female. Perhaps because he wrote in the early 1960s, however, he does not name this pattern as the gender polarity that it is—a "male"-"female" polarity pervading Philo's writings that functions very much on a cosmic scale.11

What results appears to be a logical incongruity. That which is asexual, Philo perceives as "male"—a concept which by definition should have at least some relation to a sexual category. As has long been recognized in feminist criticism, however, sex and gender are not necessarily logically connected. To compound the confusion, as will be seen in some of the examples given below, Philo often uses sexual imagery when representing that which he considers to be asexual.

The linking in Philo of the asexual with the "male" and the sexual with the "female" can be quite explicit. For instance, the number seven, as the archetypal "virgin," is distanced in every possible way from that which is "female." She is asserted to be "motherless" (άμήτωρ), begotten by the Father of the universe alone1 2—"the ideal form of the male (ιδέα της άρρενος γενεάς) with nothing of the female (αμέτοχος της προς

Brill, 1968] 42). Similarly, in the list of opposites in Agrie. 139-41, male and female are

mentioned as "human divisions" (τα άνθρωπου τμήματα) (for a schematic diagram, see

Farandos, Kosmos und Logos, 262). Curiously, male and female do not figure among the

lengthy list of opposites enumerated in Rer div. her 207-14. 9Richard A. Baer, Philo's Use of the Categories Male and Female (Leiden· Brill, 1970) 19. I0See Philo Spec leg. 1.200-201; Migr Abr 3, 206, 213. n Baer, Philo's Categories, 48-49; Baer is aware that "it is precisely Philo's depreciation

of woman that permits him to use her as a symbol of sense-perception, and, on the other hand,

his castigation of female sense-perception and the material world which leads in turn to a

further devaluation of woman" (p. 40). This is an apt description of how gender categories

operate, but Baer does not name it as such. l 2Philo Leg all 1.15: Rer. div her 170, 216; Vit. Mos 2.210; Q Gen. 2.12.

106 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

γυναικών)." She is "the manliest (άνδρειότατος) and doughtiest of numbers/'1 3 and transcends six which, as the number of creation, is "both male and female/'14 Through sexual intercourse, a "virgin" becomes a "woman." But when God begins to consort with the soul, "he makes what was before a woman into a virgin again." by taking away "the degenerate and unmanly desires (άνανδροι έπιθυμίαι) by which she was made female (αίς έθηλύνετο)." 1 5 Both Baer and Dorothy Sly have interpreted "virgin" and "male" to be soteriologicaliy equivalent in Philo.16 In essence, however, their identity runs deeper; the "virgin" is, in fact, far more "male" than "female."

But the "male" in Philo is not merely asexual. All the universal qualities which Philo considers most admirable are subsumed under the category of "male": the rational, the noetic-ideal and incorporeal, the heavenly, indivisible and unchanging, the active principle. Their opposites are categorized as "female": the irrational, the sense-perceptible and material, the earthly, divisible and changing, the passive principle.17 The superiority of that which is "male" over that which is "female" is one of the most consistently applied principles in Philo's thought. He is thus often found to compare the relative value of the various components of his conceptual universe according to their "maleness" and "femaleness."18

One can conceive, therefore, of a kind of gender gradient underlying much of Philo's thought, whose positive ("male") and negative ("female") poles are consistently defined, and whose predominant feature is hierarchy. In light of this gender gradient, it is scarcely surprising to find Philo declaring:

For progress is indeed nothing iess than the giving up of the female gender by changing into the male, since the female gender is material, passive, corporeal and sense-perceptible, while the male is active, rational, and more akin to mind and thought (Q. Exod. 1.8).

It must be reemphasized, however, that the "male" and "female" poles of this gradient are gender-linked; they are not sexually determined. Here I must take issue with Sly who. in a recent article, has argued that for Philo "women [and] homosexuals. . . either do not possess, or do not use, reason."1 9 This statement simply cannot stand, for instance, against the strik-

13Philo Spec leg 2 56 14Philo Op mun 13-14; compare Spec leg 2.58-59: Q Gen 3.38: Q Exod 2.46.

'"Philo Cher 50-52; compare Q Exod 2.3. ,6Baer, Philo s Categories. 51-53: Sly. Philo's Perception of Women. 219. r F o r example. Philo Leg all 1.1; 2.38-39: Q Gen 1.25: 2.18. 29: 3.3: 4.15: Spec leg.

1.200-201: 3.178; Ebr 73: Det. 172. 1 8For example. Philo Spec leg 1.200-201: 3.178: Sacr AC 102-103; Gig 4-5; Ebr 54-

55, 59: Q Gen 3.3:4.15. 38, 215. 19Dorothy Sly. "Philo's Practical Application of Δ ι κ α ι ο σ ύ ν η " (SBLASP: Atlanta. GA:

Scholars Press, 1991) 300.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 1 0 7

ing example of "manly" women found in Philo's portrait of the Thera-peutrides—women members of a Jewish monastic sect, who participate fully in the sect's life of study, prayer, and spiritual contemplation.20 To be sure, these women are the exception and not the rule, and Philo's views on the social status and role of women are generally quite conservative, as Sly demonstrates irrefutably.21 Philo does not, however, deny women, merely by virtue of their sex, the capacity to attain to the rational, "male" virtues to which men can attain.22 Neither are men, merely by virtue of their sex, denied the capacity to plunge down into the deepest recesses of the irrational or "female." Homosexuals are by no means the only "effeminate" men to be found in Philo's scheme although they enjoy, of course, his particular censure. Any man who in his judgment is attached to the material world and its pleasures earns the status of "effeminate," with its concommitant estrangement from the rational. Indeed in Philo's estimation, very few men can lay claim to being perfectly "male," free from any taint of the "female."

This is not to suggest that Philo's gender categories have no effect on his evaluation of the female sex as a whole.23 Given the observable social and cultural power that gender categories have wielded throughout history and society, such an eventuality would have been very unlikely, and indeed Sly has provided ample examples of the power they have wielded in Philo.24

There is no question that for Philo, the biological fact of being a woman does naturally pull one down toward the negative end of the gradient. Yet the example of the Therapeutrides demonstrates that being of the female sex does not preclude the possibility of climbing upwards toward the posi-

2 0Philo Vit Com 2, 32-33, 68-69, 72. 85-88; see Ross S. Kraemer. "Monastic Jewish

Women in Greco-Roman Egypt: Philo Judaeus on the Therapeutrides." Signs: Journal of

Women in Culture and Society 14 (1989) 342-70. Kraemer proposes that for Philo, "the

Therapeutrides were female in form only" (p. 353). There are places, however, where Philo

betrays that he views the Therapeutrides as women. First, he insists that although they are

virgins, yet they bring forth immortal progeny through the seed of the Father (Vit Cont 68).

This image is not applied to the male Therapeutae, but is commonly applied to "manly" female

allegorical or mythological figures who show up in his writings, such as Wisdom and the

Virtues. Second, in describing the partition which separates the men from the women in the

weekly worship hall, he speaks of "the modesty proper to women's nature (τη γ υ ν α ι κ ε ί α

φύσει)" (ibid.. 33). Thus for Philo the Therapeutrides are women—very "male" women, to be

sure, but women nonetheless. 2 ,Sly, " Δ ι κ α ι ο σ ύ ν η , " 305-7; idem, Philo's Perception of Women, 179-213.

—Another exception to the rule—whom Philo explicitly declares to be such—is Julia Au

gusta. In dedicating gifts to the temple, she "surpassed all her sex," for her reasoning had been

made "male" (αρρενωθείσα τον λογισμό ν) by her education under Augustus (Leg Gaj

319-20). Even if Philo does not explicitly raise the question of women's spiritual growth, as

Sly points out (Philo's Perception of Women, 223), the examples of the Therapeutrides and

Julia Augusta indicate that he allows for the possibility of such development in women. 2 3See, for example, Philo Leg Gaj 319; Op mun 156; Q Gen 1.25. 24Sly, Philo's Perception of Women, 179-213.

108 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

tive end. Nor does Philo ever imply that being of the male sex renders one immune to plummeting down toward the negative end.

It is moreover not possible to dismiss, on the grounds that they are allegorical or mythological figures,25 the fact that so many of the female characters who appear in Philo's writings possess distinctly "male" attributes. These figures tend to be represented as "virgins" who nevertheless bear children—the latter being an interesting feature that renders their female-ness unmistakable.26 It is not insignificant that such "manly" figures as Wisdom and the Virtues are styled as "virgin" women and fruitful mothers, not as men. The question of whether their characterization as women derives from Philo's imagination, from the popular culture of his time, from the constraints of the biblical text he allegorizes, or from some combination of these, is beyond the scope of this article; and at any rate, it is not certain how much these could be separated as sources. Regardless, there is something almost organic about the femaleness of these characterizations—something almost meriting the designation of sex as opposed to gender—that gives them the capacity, like their biological counterparts, to defy the gen-de category of "female."

• Divine Wisdom: Far More "Male" than "Female" The figure of Wisdom, who plays such an important role in the tradi

tions Philo has inherited,27 poses a particular problem for him, in that she embodies in female form everything he regards as "male." Of course, Wisdom is a "virgin," God's "true-born and ever-virgin (άειπάρθενος) daughter," begotten by God alone and "motherless."28

Only in relation to God does Philo depict Wisdom as "female"; she is his daughter, his wife, and the mother of his creation.29 Wisdom is decidedly "male" in relation to humanity. Philo is explicit about the exchange of genders that takes place, depending on whether Wisdom's relationship is to God or to humanity:

2 5This is what Sly appears to do in " Δ ι κ α ι ο σ ύ ν η , " 305 n. 23. 2 6Philo takes very seriously the injunction that "no man shall be childless and no woman

barren, but all the true servants of God will fulfill the law of nature for the procreation of children" (Praem. poen 108-9: see Det pot ins 147-48). For instance, he is careful to stress that Generic Virtue or Sarah is not incapable of bearing, and "indeed she bears only good things ceaselessly and without interval." It is only because Abraham is not yet ready to receive her offspring that she has seemed barren (Cong. 3-10). Philo also makes sure to aver that the virginal Therapeutrides, whom he so admires, bring forth immortal progeny through the seed of the Father (Vit Cont 68).

2 7Fruchtel (Die kosmologischen Vorstellungen, 172-75) discusses the parallels in the portrayal of Wisdom in Philo and in the books of Proverbs, Wisdom of Solomon, and Ben Sirach.

2SPhüo Fug 50; Q Gen 4.145. 29Philo Cher 49; Det. pot ins 54: Ebr. 30-31.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 1 0 9

while Wisdom's name is feminine, her nature is masculine. . . . For that which comes after God, even though it were chiefest (πρεσβύτατον) of all other things, occupies a second place, and therefore was termed feminine to express its contrast with the Maker of the Universe who is masculine, and its affinity to everything else. . . . Let us, then, pay no heed to the discrepancy in the gender of the words, and say that the daughter of God, even Wisdom, is not only masculine but father (την θυγατέρα του θεού σοφίαν άρρενα τε και πατέρα είναι), sowing and begetting in souls aptness to learn, discipline, knowledge, sound sense, good and laudable actions (Fug. 51-52).

The right reasonings of Wisdom (οι σοφίας ορθοί λόγοι) mount, impart seed, and impregnate the soul of deep rich virgin soil, bringing forth goodly, "male" offspring.30

Nevertheless, upon first inspection it would seem that at least in one respect Wisdom continues to play a "female" role with regard to humanity, and this is in her role as "mother of all things" (ή μήτηρ των συμπάντων).3 1

The nourishment she provides from her breasts, however, is of the heavenly kind,32 which must be carefully distinguished from the material sustenance provided by Mother Earth and Nature.33 When elevated onto a spiritual plane, the one female role most clearly associated with a woman's biological function—that is, the role of motherhood, especially the processes of childbearing and breast-feeding—carries for Philo a certain ambiguity with respect to his gender categories. The qualities that Wisdom brings forth from her breasts and womb are spiritual and "male"; they are of the same kind as those which she "sows" and "begets" in the soul.34

Far removed from the irrational, sense-perceptible, "female" world, Wisdom enjoys a supracosmological status, affirmed above all by her close affiliation and frequent virtual identity with the figure of the Logos.35 The

3 0Philo Som 1.200. 3 1 Philo Leg all 2 .49:0 Gen 4.97; Fug 109: Virt. 62; Ebr. 30-31: he prefers the model

of God and Wisdom as father and mother of the cosmos to that of sense perception and mind

(Det. 54: compare Poster C. 177; Fug. 109). 3 2Philo Det pot. ins 115-16; compare Ebr 112-13. 3 3For example, Philo Op mun 38-39. 43. 133. 3 4Philo Fug. 52; Som. 1 200: as another instance of this ambiguity, when the purified

"virgin" soul receives the divine seed (a passive "feminine"' role), she then "moulds it into

shape and brings forth new life" (an active "masculine" role) (Praem. poen 159-61). 3 5 E. R. Goodenough (By Light, Light [New Haven: Yale University Press. 1935] 23) de

clares that "Philo flatly identifies the Logos with Sophia." and Harry A. Wolfson calls one

"only another word for" the other (Philo: Foundations of Religious Philosophy in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam [2 vols.; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1947] 1. 258).

Burton L. Mack observes that "most scholars have commented on the identity of the figures

of Wisdom and the Logos in Philo" (Logos und Sophia: Untersuchungen zur Weisheitstheologie im hellenistischen Judentum [Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1973] 110 n. 10). In

1 1 0 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

whole universe was framed (δημιουργέω) through the Logos;36 equally, it is through divine Wisdom that the cosmos was wrought (δημιουργέω).3 7

Both divine Wisdom and the Logos are allegorized as the indivisible turtledove, identifying them with the "monad."3 8 They are both called the "eldest" or "chiefest" (πρεσβύτατος/πρεσβυτέρα), 3 9 and are both said to have many names, including "the beginning" (αρχή), "the image of God" (είκών θεού), and "the one who sees God" (ή ορασις θεού/ό ορών). 4 0

Wisdom is "God's archetypal (αρχέτυπος) luminary":41 the Logos, too, is is the model (παράδειγμα) or pattern of light.42 Both are compared to the heavenly food (ή ουράνιος τροφή) or manna which God rained down upon Israel.43 Like the Logos. Wisdom is involved in the activity of the creative (θεός) and kingly (κύριος) powers of God.44 In one place, Philo declares that Wisdom is the fountain (πηγή) from which the divine Logos flows; in another, she is called the Mother of the Logos.45 Elsewhere, the roles are reversed: the "supreme Divine Logos" is the fountain (πηγή) from which Wisdom springs. Or they are simply merged into one—"the divine logos is full of the stream of wisdom."46 On one occasion, the Logos even carries reminiscences of Wisdom's motherhood—he is "pregnant with divine luminaries" (ό μετάρσιος και έγκύμων θείων φώτων λόγος). 4 7

A close relationship also exists between Wisdom, the Logos, and Generic Virtue (ή γενική αρετή), or Sarah.48 It is therefore scarcely surprising to find Philo also emphasizing the "maleness" and "virginity" of the Virtues.49 Sarah is called the "virtue-loving mind" (ή φιλάρετος διάνοια). The feminine word, ή διάνοια, is often equivalent in Philo to ό νους. 5 0

addition to Goodenough and Wolfson. Mack lists as examples M. Heinze who also considers

them "identical"; A. Gforer and H. F. Weiss, for whom the Logos and Wisdom are "inter

changeable concepts"': and A. Wlosok, who describes them as "almost indistinguishable."

"l6Philo Spec leg 1 8 1 : compare Sacr AC 8; Deus imm 57.

^Philo Rer div her 199; Fug 109: compare Virt 62: Det pot ins 54. 3 8Philo Rer div her 127. 234. , 9PhiloFif£ 101:/ter dix her 205: Virt 62. 4 0Philo Conf ling 146: Leg all 1.43: Fug 101. 4 1Philo Migr Abr 40. 4 2Philo Som 1.75. 4 , PhiloFttg 137-38. for div her 79. 191. 4 4Philo Q Gen 1.57 4 5Philo Som 2.242. Fug 108-9 respectively. 4 6Philo Fug 97. compare 137: Som 2.245 respectively 4~PhiloLeg all 3.104. 4 8Ibid.. 1.64-65: compare Som 2.241-43. 4 9Philo Praem poen 53: Fug 51. 3 0The interchangeabihty of ή δ ι ά ν ο ι α and ό ν ο υ ς is especially evident in Philo Migr.

Abr. 213: "for the irrational faculties come from sense-perception, as do the rational from

understanding" (έκ γαρ α ι σ θ ή σ ε ω ς ori άλογοι ώς έκ δ ι α ν ο ί α ς αί λογικαί δυνάμεις

είσί).

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 111

Like Wisdom, she is "motherless" (άμήτωρ), having "no part in female parentage" (θήλεος γενεάς αμέτοχος), 5 1 a "virgin" but nevertheless a fruitful mother of spiritual benefits and qualities.52

An interesting gender reversal takes place when the "virgin" Virtue, Rebekah (constancy and perseverance),53 is compared to her brother, Laban. She is assigned to the rational part of the soul, whereas Laban or "whiteness," as "a figure of the honours (shown) to the splendour of sense-perceptible things," is assigned to the irrational part.54 As in the case of Wisdom, Philo is explicit about the gender reversal that takes place when Virtue is in relationship to humanity, even in relationship to human thought:

in the matings within the soul, though virtue seemingly ranks as wife, her natural function is to sow good counsels and excellent words. . . while thought (ό λογισμός), though held to take the place of the husband, receives the holy and divine sowings. Perhaps however the statement above is a mistake due to the deceptiveness of the nouns, since in the actual words employed νους has the masculine, and αρετή the feminine form. And if anyone is willing to divest facts of the terms which obscure them. . . he will understand that virtue is male (διότι άρρεν μέν έστιν ή αρετή φύσει), since it causes movement and affects conditions. . . while thought is female (θήλυ δε ό λογισμός), being moved and trained and helped, and in general belonging to the passive category (Abr. 100-2).

This gender confusion in Philo's treatment of Wisdom and the Virtues reveals the rigidity of the hierarchy of his gender gradient. Baer has explained this gender confusion as being an indication that Philo's use of the categories "male" and "female" is "purely functional, never ontological."5:)

But qualifying Wisdom or the Virtues as "male" whenever they play the active, dominant role, is not merely an assigning of function. Why are they "male" when they play such a role, if being "male" does not involve certain ontological qualities (the active, dominant, and higher rational principles) which being "female" excludes? Above all, it is when Philo declares that "progress is indeed nothing less than the giving up of the female gender by changing into the male"5 6 that the ontological nature of Philo's gender categories becomes apparent.

5 lPhilo£Z?r 61; Rer div her 62: Q Gen 4.68. 5 :Philo Spec, leg 2.54: the mind (ή δ ιάνοια), linked to the figure of Sarah, is on several

occasions said to be impregnated (for example. Sacr AC 102; compare Spec leg 2.29-31) 5 3 In a lengthy segment (Poster C 132-57), Rebekah is styled as the model teacher. 5 4Philo Q Gen 4.117, 118: Som. 1.45: Laban is given a somewhat more intermediate role

in Q Gen 4.239. As the simplest sense-perceptible color, white, he represents the middle

course between excessive indulgence and extreme asceticism. 55Baer. Philo's Categories. 66. 5 6Philo Q Exod 1.8.

112 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

Unlike his approach to some of his other philosophical assumptions, Philo never seems to feel the slightest need to defend his gender hierarchy. This suggests that the hierarchy has little to say about any personal misogyny on Philo's part; rather, this gradient was probably infused so deeply into the popular philosophy of his environment that it would have been equivalent to what we today would accept as "scientific fact."57 Like he did with other facts of his universe, Philo found it important to harmonize this fact with his allegorical and mythological interpretations of scripture. This harmonization appears rather disharmonious and confusing to the modern mind. Nevertheless, it is also significant that Philo did not attempt to transform the figures of Wisdom or the Virtues into men, which would not have been a logical impossibility. Perhaps their organic rootedness in the popular culture of his time did not permit such a transmutation.

• Sense Perception and Philo's Ambivalence toward the "Female"

In her close affinity with the material world, sense perception is predominantly "female," and Philo is quite consistent in depicting her as such. There is little gender confusion here. In addition to Eve, other figures allegorically representing sense perception are the five daughters of Zelophad, Rachel, and Lot's wife, all of whose affections are firmly tied to the earthly realm.58 The male figures of Laban, Lot, and Joseph are also identified with sense perception in order to stress their "effeminate" nature as men whose allegiance is primarily to the material world and its pleasures.59 The close affinity of sense perception with the irrational animal world is also emphasized by the frequent representation of the senses as cattle (κτήνη). 6 0

Although sense perception is predominantly "female," Philo is not consistently negative in his attitude toward her. Instead, he displays a marked ambivalence, which seems to mirror a certain equivocation on his part toward the material world itself. On the one hand, Philo frequently extolls the perfection and harmony of God's creation.61 In comparison to Plato's Timaeus, which itself espouses an admiring and reverential attitude for the created world,62 Philo is quite profuse in his praise of creation's wonders.

5 7This is not to suggest that these constructs were necessarily the mainstay of all philo

sophical thought at this time. No matter how deeply ingrained and widely accepted, popular

philosophy never represents the worldview of all a culture's members. 5 8Philo Migr Abr 205-6: Ebr 54; Q. Gen 4.52. 5 9Philo Q. Gen 4.117-18: Fug 45; Som \A5\Migr Abr 13,203-4,213. 60Philo Leg. all. 3.111; Agrie 30-34; Sacr AC 104; Cher. 70: Poster. C 98; Migr. Abr

212: Q Gen 1.94; 2.56. 6 'For example. Philo Deus imm 106-7; Op mun. 78: Cong. 96. 6 2For example, Plato Tim. 32d-33a.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 113

As D. T. Runia observes, "Philonic prolixity stands in marked contrast to Platonic restraint."63 On the other hand, the mind's necessary association with the body and its material surroundings is for Philo an ever-threatening source of pollution, and because sense perception is the link between the mind and its environment, she is a part of that threat.

Insofar as sense perception is essential to the observation of creation's marvels, she is considered indispensable, a necessary corollary to the mind. Philo insists that before the mind (ό νους) had converse with sense perception, he was "blind, incapable," "truly powerless"; everything around him was "wrapped in profound darkness."64 For Philo, the loss of the sense organs, particularly of sight and hearing, is a singularly incapacitating plight.65 The most important reason why sense is essential to the mind, however, is that "without sense it is always impossible to obtain accurate knowledge of any of the phenomena in the sensible world which form the staple of philosophy."66

While the mind cannot apprehend an object apart from sense, neither can sense maintain the act of perceiving apart from the mind.67 Just as the mind is blind without sense perception, so sense perception without the mind is "a blind thing, inasmuch as it is irrational."68 Ultimately, it is the mind that extends to the senses their powers of perceiving, since sense gains impressions only of "the corporeal forms (τα σώματα) of things."69 Sense receives the impressions and the mind discerns their qualities.7 0 The relationship between mind and sense perception is thus very much one of interdependence.

Because of her close association with mind, sense is not entirely one with the material world. She lies "on the borderline between the intelligible realm and the sensible" (μεθόριοι γαρ αϊ αισθήσεις οΰσαι των νοητών τε και αισθητών), 7 1 and "occupies a position midway between the mind and the body, for she has a part in each of them; she is not inanimate like the body, and she is not intelligent like reason."72 From this perspective,

6 3 D. T. Runia, Philo of Alexandria and the Timaeus of Plato (Amsterdam: VU Boekhandel, 1983) 382. Runia notes that the frequency with which such passages occur in Philo "is quite out of proportion to the relative infrequency of their occurrence in the Timaeus'' (p. 89). For further examples of Philo on the theme of praise and thanksgiving for the cosmos, see ibid.. 88-92, 381-83.

6 4Philo Cher. 58-59. 65Phiio£¿?r 155-56. 66Philo Cong. 21; compare Migr. Abr 105. 67PhiloLeg. all 2.71. 68Ibid., 3.108-9. 69Ibid., 3.108-9; compare Cong 143; Fug 182. 70Philo Leg. all 3.57-58. 7 'Philo Mut. nom 118. 72Philo Q Gen. 4.117.

114 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

sense perception is not herself a source of evil. Philo can therefore affirm that she "comes under the head neither of bad nor of good things (ή αϊσθησις ούτε των φαύλων ούτε των σπουδαίων εστίν), but is an intermediate thing (άλλα μέσον τι αύτη) common to a wise man and a fool, and when she finds herself in a fool she proves bad, when in a sensible man, good."73 Interestingly, Adam, as the "neutral mind" (ό Άδαμ δε ό μέσος εστί νους), is described in much the same terms: "insofar as he is mind, his nature is neither bad nor good (ούτε φαύλος ούτε σπουδαίος), but under the influence of virtue and vice it is his wont to shift toward good and bad/'7 4

But Philo does not always maintain sense perception's intermediate status as a corollary to the mind. The boundaries between sense perception and the material objects she perceives are often blurred. For instance, in Quaestiones et solutiones in Genesin 2.21, Philo blends them into one by propounding that the five senses are "threefold, so that altogether there are fifteen: sight, the thing seen, (the act of) seeing; hearing, the thing heard, (the act of) hearing; smell, the thing smelled. (the act of) smelling; taste, the thing tasted, (the act of) tasting; touch, the thing touched, (the act of) touching." By being so intimately associated with the material world, sense perception also becomes closely connected with pleasure (ή ηδονή)—the figure in Philo most thoroughly engrossed within the "female." and thus the figure who occupies the very lowest position on his gender gradient. In the Eden story it is sense perception or Eve whom pleasure or the serpent first beguiles. For it is only through the senses that pleasurable impressions can be conveyed to the mind, and thus it is through the senses that the mind is rendered pleasure's slave.75

The identification of the serpent with pleasure is interesting because the Greek word for "serpent" is masculine (ό όφις), while the word "pleasure" is feminine (ή ηδονή). This results in Philo switching back and forth between masculine and feminine forms when speaking of this figure, and reveals how determined he is to represent the serpent, or pleasure, as "female." The serpent symbolizes all the material pleasures.76 Occasionally, Philo links the origin of sin specifically to sexual desire and he considers the pleasures ensuing from intercourse with women to be "the most violent of all in their intensity."77 But Philo's concern with pleasure is for the most part more general than this, and includes such pastimes as delicate living,

7 3Philo Leg all 3.67: compare Det pot ins 168-69. 7 4Philo Leg all 3 246. 7:>Philo Op mun 165-66: compare Q Gen 1.37. 47. 76PhiloZ.eg all 2.74-76: Op mun 157-62: Q Gen 1.48. 77Quotation from Leg all 2.74: see Op mun 151-52: Leg all 2.71-72.

SHARON LEA MATTILA 115

luxury, avarice, gluttony, drunkenness, and carousing.78 His attitude toward her is categorically negative: "The serpent, pleasure, (ό δε όφις ή ηδονή) is bad of herself (εξ εαυτής έστι μοχθηρά). . . she has in her no seed from which virtue might spring, but is always and everywhere guilty and foul."79 She "is a mighty force felt throughout the whole inhabited world, no part of which has escaped her domination."80 Philo also depicts pleasure as a whore, whose vivid image trails with it the longest list of vices preserved from antiquity.81

From this perspective. Philo presents another, altogether pejorative, portrait of the union of sense perception and mind. Before the creation of sense perception (Eve), the earthly man (Adam) had no means of contact with pleasure. Thus, being stamped out of the heavenly archetype, he was of perfect beauty, excelling in noble traits, and attaining "the very limit of human happiness."82 This state continued, so long as he remained in solitude. Philo is explicit: it is woman who "becomes for him the beginning (αρχή) of blameworthy life."83 In Quaestiones et solutiones in Genesbu Philo's language is stronger: "It was the more imperfect and ignoble element, the female, that made a beginning of transgression and lawlessness"; woman "was the beginning of evil and led him (man) into a life of vileness"; woman rules "over death and everything vile."84 Moreover, the passions are intrinsically linked with pleasure85 and "by nature feminine" (θήλεα δε φύσει τα πάθη). 8 6 They are the offspring (τα εκγονα) of sense perception or sense perception is "the cause of the passions" (ή παθών α ι τ ί α αϊσθησις). 8 7 Evil enters the soul through the passions, and passions through evil at the same time.88 Thus sense perception, as the source and spring of

7 8 It is not the mind alone to whom pleasure does her damage. Although pretending to be her lover, pleasure is actually a mortal foe to sense perception herself, maiming and dimming the senses with her surfeit (Leg all 3.111-12. 182-85: compare Q Gen 1.48).

7 9Philo Leg all. 3.68: compare Q Gen 4.245: Philo's acknowledgement that *'a created being cannot but make use of pleasure" and that "apart from pleasure nothing in mortal kind comes into existence" (Leg all 2.17-18) does little to mitigate his pronounced negative attitude toward her.

8 0Philo Spec leg 3.8. 8 1Philo Sacr AC 21-33. 8 2Philo Op mun 150-51. 8 3Ibid. 8 4Philo Q Gen 1.43.45. 37. 85Pleasure is the "source and foundation" (αρχή καί θεμέλιο*:) of passion (Leg all

3 113). and passion is also the source of pleasure (αρχή δε η δ ο ν ή ς μεν το π ά θ ο ς ) (ibid.. 3.185).

8 6Philo Det pot ins 28: compare Deus imm 3. 8 7Philo Leg all 2.6. 50. 8 8Philo Q Gen 2.29.

116 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

passions, leads to transgression and sin.89 From this perspective, therefore, Philo often makes the connection between sense perception and the origin of evil.90

For Philo, mind and sense perception are locked in a continual power struggle for ascendancy in the soul.91 In Legum allegoriae.92 Plato's image of reason as charioteer and pilot over the horses of high spirit and lust, a theme derived from Phaedrus,93 is applied not to Plato's tripartite division of reason, high spirit, and lust94 but to a bipartite division of mind versus sense perception, in which the senses play the role of unruly horses.95 Mind must be ever-heedful. If the understanding (ή διάνοια) is awake, then sense is deactivated; if the mind (ό νους) sleeps, then the senses awake to hold the mind in slavery.96 Philo recognizes that sense perception can never be entirely under the control of mind:

should the mind choose to bid the sight not to see, the sight will nonetheless see what lies before it. The hearing, again, when a sound has reached it, will assuredly give it entrance, even if the mind resolutely command it not to hear. And the sense of smell, when odours have found their way into it, will smell them, even though the mind forbid it to welcome them (Leg. all. 3.56).

In Philo's imagination it is this stubborn recalcitrance of sense perception that renders it a constant threat of pollution to the soul. In short, Philo is aware that the human soul cannot extricate itself totally from its body and material environment. Thus the mind must be ever on the alert, ever engaged in the struggle to free itself from the matter in which it is immersed. Such matter is mortal and changeable, perfused as it is with nerves, impulses, needs, and desires.

The power struggle between mind and sense perception sometimes finds itself expressed in decidedly dualistic terms. That is, they are sometimes represented not merely as opposing categories, but as primary and irreducible divisions.97 Such dualism ineluctably leads to the conclusion that, at

89Ibid., 3.41. 9 0For example. Philo Cher 52: Q Gen 4.238. 242. 9 'The mind can cooperate with sense perception, rather than struggle against her. in which

case the results are disastrous: see Q Gen 2.18. 9 2Philo Leg all 3.222-24: compare Det pot ins 52-53. 9 'Plato Phaedrus 253d. 94Plato*s tripartite division of the soul is found in Phaedrus 246b-246d (reason as chari

oteer and pilot): Tunaeus 69c-71a; Republic 434e-444d. 9 5As Ruma (Philo and the Timaeus. 263-64) observes, Philo has the tendency to view the

soul as essentially bipartite, divided into rational and irrational parts. 9 6Philo/ter div her 257; Leg all 2.70: compare Fug 188-93. 9 'This understanding of dualism is derived from Jean Duhaime. "Le dualisme de Qumrân

et la littérature de sagesse vétérotestamentaire." Église et Théologie 19 (1988) 401-2.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 1 1 7

the end of the conflict, there can be no middle ground. If superior mind acquiesces, it "resolves itself into the order of flesh which is inferior, into sense perception, the moving cause of the passions."98 If sense perception yields, "there will be flesh no more (ούκέτι εσται σαρξ), but both of them will be mind (άλλα αμφότερα νους) . " 9 9

Yet dualism does not always mark Philo's depiction of the struggle between mind and sense. Elsewhere a yearning for the eventual reconciliation of mind and body is evident. For instance, Philo explains that in this present "time of war," "the sovereign mind like a father should join with its particular thoughts as with its sons, but (not join) any of the female sex, (that is) what belongs to sense."1 0 0 For "one must separate one's ranks and watch out lest they be mixed up and bring about defeat instead of victory."1 0 1 But when the time has finally come for the relentless battle to cease, then it will be

fitting and proper. . . to bring together those (elements) which have been divided and separated, not that the masculine thoughts may be made womanish and relaxed by softness, but that the female element, the senses, may be made manly by following masculine thoughts and by receiving from them seed for procreation, that they may perceive (things) with wisdom, prudence, justice, and courage, in sum, with virtue.102

Here the categories are not irreducible. The flesh does not become pure mind; the earthly "female" does not dissolve itself into the disembodied perfection of the "male." Instead, the "female" blends and merges with the "male." She is "made manly"—she does not become "male." The desire for reconciliation and harmony between mind and sense perception finds its most vivid expression in Philo's description of the choir by the seashore in Exodus 15: "The choir of the men shall have Moses for its leader, that is mind in its perfection; that of the women shall be led by Miriam, that is sense perception made pure and clean"1 0 3 (αϊσθησις κεκαθαρμένη). Thus "our whole composite being, like a full choir all in tune, may chant together one harmonious strain rising from varied voices blending one with another."104

98PhiloL<?g all 2.50.

"Ibid.; compare Vit Mos 2.288. , 0 0Philo Q Gen 2.49: compare Rer div. her 185. 1 0 ,Philo Q. Gen 2.49. , 0 2Ibid. l 0 3Philo Agrie 80-81. 1 0 4Philo Migr Abr 104: Philo uses this image of Exodus 15 to describe in glowing terms

the joining of male and female choirs at the sacred vigil after the banquet of the Therapeutae

(Cont. 85-88).

118 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

Although the senses are a potential source of evil with which the mind must be in continuous struggle, they also play a necessary role in the soul's journey toward perfection. The individual who seeks after God must spend some time in Haran, "the place of sense-perception" (το xf\ç αίσθήσεως χωρίον), as an intermediate stage of the journey.1 ( b For self-knowledge includes knowledge of the senses, what they are and how they operate.106

Once one has gained a thorough familiarity with the nature of one's bodily parts, however, it is time to move on.1 0 7 Ultimately, the most desirable state must involve the rejection of sense perception, which is why "the persons to whose virtue the lawgiver has testified, such as Abraham. Isaac. Jacob and Moses, and others of the same spirit, are not represented by him as knowing women."108 Nevertheless. Philo recognizes that one cannot sever oneself from her absolutely, "since to issue such a command as that would be to prescribe death/*109

Philo's highly ambivalent depiction of sense perception as predominantly "female" is by far the most common representation in his writings. It is not. however, the only one. Curiously, Philo is truer to Plato's tripartite division in Le gum allegoriae 3.115 and assigns the senses to the rational part of the soul (το λογικόν). Here the two horses are. as in Plato, high spirit (το θυμικόν) and lust (το έπιθυμητικόν). while the senses are styled as "bodyguards" (οι δορυφόροι)—located with the mind in the region of the head (περί κεφαλήν)—who assist the mind in its war against the passions. This is a decidedly "male" image of the senses and one which casts them into a role that is almost the antithesis of the role they play elsewhere in Philo. Yet this anomalous portrait occurs in quite a few places and is too striking to ignore.110 Runia has observed that a number of other authors such as Cicero, the Platonists Albinus and Galen, and the commentator Calcidius have recast the Platonic imagery in the same way as Philo has in these particular passages.111 He concludes that Philo's use of this image is "by no means an original adaptation, but shows dependence on the way the Timaeus was traditionally read."1 1 2 Indeed, in Legum allegoriae 3.115. Philo explicitly attributes this image of the senses to certain unnamed "philosophers." Hence, it would seem that Philo incorporated this

, 0 5Philo Migr Abr 187. 189. 195. 1 0 6Alan Mendelson (Secular Education in Philo of Alexandria [New York: Kta\. 1982] 69-

76) argues that the encyclical studies provide this service as the intermediate stage of the

soul's journey toward the higher knowledge of Wisdom. 1 0 7Philo Migr Abr 189. 197: Som 1.46. 1 0 8Philo Cher 40. 1 0 9Philo Migr Abr 1. , 1 0Compare Philo Spec leg 3.111: 4.92. 123: Som 1.27. 32; Conf ling. 19-20: Det pot

ins 35. 85. 1 1 'Ruma, Philo and the Timaeus, 265-67. 1 I 2Ibid.. 267.

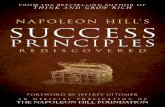

DESCRIPTIVES Ι GOD(TOÖV) DESCRIPTIVES

GENDER GRADIENT

LU

r

rational / active / heavenly incorporeal / unchanging / indivisible

undifferentiated (monad)

GENDER GRADIENT

LU

1 Wisdom (ή σοφία) / Logos

rational / active / heavenly incorporeal / unchanging / indivisible

undifferentiated (monad)

- 1

< the Powers (θεός and κύριος)

the Virtues (αϊ άρεταί)

World of Forms noetic-ideal (ο έκ των ιδεών κόσμος)

\ "h,*?H k

Man / Adam Platonic governing principle

Invisible

¡¡¡ΒΙΕ Ι ΚΛΙ~Λ , Ι . ._~ _ ,-l e . X Man / Adam Platonic governing principle

Invisible

• ' ι iviiiiu ^υ νους/η oiixvoiuj Man / Adam Platonic governing principle

Invisible •ΙΙ Nature 1 fn ibiSfTi'")

Man / Adam Platonic governing principle

Invisible

'

Man / Adam Platonic governing principle

Invisible

ι

1 f

Differentiated / Visible

Woman / Eve Hi Sense/Perceptior 1 f

Differentiated / Visible

Woman / Eve

II (ή αίσθησις)

¡H Vision Miriam

^H Hearing

^H Smell effeminate male / Laban

^H Taste

H Touch bestial / cattle

• Passions (τα πάθη) Platonic spirited

H Body (το σώμα) Platonic appetitive

H. Pleasure (ή ηδονή) Serpent (ό όφις) / Whore

*

' Unformed Matter (ή ΰλη) 1 irrational / passive / earthly material / changing / divisible

120 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

popular interpretation of Plato into his writings where it fit into his allegorical exegesis of a given biblical text.

in Legum allegoriae 3.114-15. Philo must find a way to work into his allegorical scheme the detail from Gen 3:14 that the serpent was cursed to crawl on its breast and belly. Thus the biblical text itself constrains him to employ this popular interpretation of Plato's tripartite division, which assigns to the breast and belly the "female" aspects of the soul, or the passions (Plato's το θυμικόν) and pleasure (Plato's το έπιθυμητικόν). What is left is the region of the head, to which the mind (Plato's το λογικόν) and the senses are now assigned by this popular Platonic tradition, despite the fact that such a classification of the senses fits in so poorly with the vast majority of what Philo has to say about sense perception elsewhere. Thus the restrictions of Philo's allegorical method tend to lead him into such inconsistencies.

£* Universal Nature in Philo In Stoicism, the word "nature" (ή φύσις) can refer to several interre

lated but distinct concepts. The literal meaning of the word is "growth," then "the way a thing grows," and by extension "the way a thing acts and behaves." By further extension, it comes to mean "the force that causes a thing to act and behave as it does"—such as the nature of a plant, or the nature of an animal. Since the Stoics envisioned the cosmos as a living organism (ζωον). the universe itself has a "nature."1 1 3 All these uses of the word are found in Philo.

Needless to say. Philo is not a believer in Stoic pantheism; nor does he acknowledge the Stoic concept of a material pneuma pervading ail things.114

In De opificio mundi 129-30, Philo assigns Universal Nature a most interesting mediating role—not between the material world and the deity himself, but between the material world and the world of forms (ό έκ των ιδεών κόσμος). The incorporeal ideas in the world of forms are the "seals" (σφραγίδες) after which sensible objects are molded. Universal Nature is the one who uses these incorporeal patterns (ασώματα παραδείγματα) to bring forth finished products into the world of sense (τελεσιουργει των έν αισθήσει). This connection of Nature with the world of forms is another significant departure from Stoic Nature, and serves to bring Nature in con-

m F . H. Sandbach, The Stoics (London: Chatto & Windus. 1975) 31-32. 79-80: A. A.

Long. Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics (2d ed.: Berkeley/Los Angeles:

University of California Press. 1986) 189. Plato described the universe as a "a living being

imbued with mind and soul"' (ζωον εμψυχον εννουν) (Timaeus 30b). but no one "had

applied the analogy as extensively as the Stoics" (Michael Lapidge, "Stoic Cosmology." in

John Rist, ed.. The Stoics [Berkeley. CA: University of California Press. 1978] 163). l , 4 For example. Philo Migr Abr 178-81.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 121

tact with the divine Logos, with whom the "intelligible world'* (ό νοητός κόσμος) is identified.115

Nevertheless, in some striking respects the figure of universal Nature in Philo is reminiscent of Stoic Nature.1 1 6 This is so especially in her role as master craftswoman (the power or principle which shapes and organizes all material things), and in her perfection, providence, and essential "right reason" (ορθός λόγος φύσεως), often expressed in Philo as the "Law of Nature" (νόμος φύσεως or θεσμοί φύσεως). 1 1 7 Her connection with the world of forms notwithstanding, all the works of Nature appear in the material world, for "she has not generated more than three dimensions"118

(πλείους γαρ τριών διαστάσεις ούκ έγέννησεν). Like the earth whom Philo relates explicitly to Demeter, Nature is often depicted as a mother whose breasts supply drink and whose womb provides food for all living creatures.119 In contrast to Wisdom, Nature's food is clearly material sustenance; it is "bread and the spring water which gushes up in every part of the inhabited world."120

In addition to materially sustaining life. Nature's primary role is to dig her hands into the formless mass of matter in order to mold it and give it shape. While understood to be the "gifts of God," the harmonious and wondrous workings of the cosmos are repeatedly attributed to Nature.1 2 1

Even human beings, fashioned out of the four elements, are called the "works of Nature" (τα φύσεως έργα), and she is said to have endowed humanity with reason.122 Nature is also at center stage when the intricate mechanisms of the human body are being considered.123

, , 5 Philo Op mun 20. 24-25. 36: Fug 12-13. l l 6 See Long's summary of the concepts associated with Stoic Nature (Hellenistic Philoso

phy. 148-49). Philo's Nature does not undergo continuous cycles of death and rebirth as does

Stoic Nature. 1 , 7Helmut Koester has argued, not compellingly. that Philo was the originator of the con

cept "Law of Nature" ("ΝΟΜΟΣ ΦΥΣΕΩΣ: The Concept of Natural Law in Greek Thought."

in Jacob Neusner, ed.. Religions in Antiquity [Leiden: Brill, 1968] 521-41). As Richard A.

Horsley has contended, "both Cicero and Philo are dependent on an established Stoic tradition

for the argument on the law of nature" ("The Law of Nature in Philo and Cicero." HTR 71

[1978] 40), even if their treatment is not a perfect match with traditional Stoic concepts (pp

40-42) Less certain is Horsley's hypothesis that both Cicero and Philo have drawn their

formulations from an eclectic philosophical movement inaugurated specifically by Antiochus

of Ascalon (pp. 42-59). u*Vh\\o Decal 24-26. 1 , 9Philo Op mun 38-39, 43, 133; Plant 15; Deus imm 39: Decal 41; Spec leg 2.100-

103: Omn prob lib 79. 1 2 0Philo Praem poen 99: Spec leg 2.205; Virt 129-30. 1 2 , For example. Philo Virt 93-94, 129-30; Spec leg 1.322; 2.100-103. 172-73: Mut

nom 158-60, 231; Som 1.103: Rer div her 152-53. 1 2 2Philo Decal 132; Spec leg 1.266. , 2 3 For example, Philo Spec. leg. 1.146; 3 184, 198; Sacr AC 98; Poster C 4. 104: Leg

122 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

The task of directly fashioning and organizing the nuts and bolts of creation appears to be beneath the dignity of the transcendent deity himself.124 Quaestiones et solutiones in Gene sin 2.7 has a rare instance in which God actually gets his hands into the dirty work of creation. He is said to have coiled up the human intestines so that food would not pass too quickly from the stomach to the buttocks, an idea derived from Timaeus 73a. As in the Timaeus, however, the emphasis here is on divine providence, which would force an entrance of the deity onto the scene.125 It is noteworthy that even here Nature regains center stage toward the end of the passage, where the processes of digestion, metabolism, and excretion are delineated in more detail. This distancing of the creator from the matter out of which his creation is formed stands in marked contrast to the Timaeus. As Runia observes, "the Platonic demiurge, as ποιητής και πατήρ, does not hesitate to deal directly with the material at his disposal, as is shown by the wealth of demiurgic imagery."*126

In her role as craftswoman and sustainer of life, Nature is described in terms that give her the status of a demiurge in her own right, in some ways independent of the transcendent God:

[Nature] is uncreated >et she generates life (γένεσιν άγένητος ούσα), needs no nourishment yet gives it. changes not yet gives growth, admits neither of diminishment nor increase yet gives the ages of life in succession. . . she knows neither old age nor death. And why should we count it strange that the uncreated (το άγένητον) does not deign to use the good which belongs to the created (Sacr. AC 98-100).

In Qui s rerum dixinarum heres sit 114-16. Philo stresses that the "beginnings (αι άρχαί) of things both corporeal and incorporeal (και σωμάτων και πραγμάτων) are found to be by God only (κατά θεον εξετάζονται μόνον)." Yet he ascribes to invisible Nature ''the original, the earliest and the real cause (δ* άνωτάτω και πρεσβυτάτη και ώς αληθώς α ι τ ί α ) " of all living creatures from plants to human beings. Nature is "the fountain or root or foundation (πηγή και ρίζα και θεμέλιος), or whatever name you give to the beginning which precedes all else." The k'lore of each science" is "a superstructure built on Nature." While it is always understood in the background that the cosmos is created by God, Nature, who is herself "uncreated" (άγένητος ούσα) and eternal, repeatedly appears as the one who shapes, fashions, and even generates the material world.

Gaj. 128. in Op mun 67. Philo displa>s some confusion as to whether Nature is the artificer

(τεχνίτης) who forms living creatures or rather the art (τέχνη) by which they are formed. Yet

God himself plays no role in this description of how living beings are fashioned. Onh Nature

figures here , 2 4See especially Philo Spec leg 1.329. 12:>See Runia" s discussion of Philo's use of Timaeus 73a in Philo and the Timaeus. 212-14. , 2 6Ibid., 374. emphasis mine.

SHARON LEA MATTILA 123

Reflecting the common Greek axiom that nothing can come out of nothing, unformed matter in Philo is itself uncreated and eternal, having an existence, as Runia has framed it, "in some way independent of God."127

But matter is negative, irrational, and passive, that is, altogether "female" as an original principle, while the figure of Nature is both rational and active in her generative and creative role. Yet Nature is also identified with the cosmos she has formed, and like the cosmos is a living organism,128

having both a "masculine" and "feminine" aspect. Predictably, her "feminine" side is material, suffering, and passive;129 the matter she has formed is somehow also a part of her.

Nature is therefore probably best described as semi-immanent. She is immanent insofar as she is identified, as a living organism, with the material cosmos she has formed, and insofar as the products of her activity are confined to the material world. Yet Philo's Nature is not fully immanent like Stoic Nature, for she is in contact with the transcendent Logos and the world of forms, and the paradigms from which she shapes the corporeal objects lie beyond the material realm. Furthermore, the "right reason" of Philo's Nature, or the "Law" by which she operates, is identified with the Law of the transcendent God.130

As in Stoicism, in Philo Nature is a perfect organism.131 There are times when she appears to be "at strife in herself, when her parts make onslaught one on another and her law-abiding sense of equality is vanquished by the greed for inequality." Drought, rainstorms, violent winds, intense cold, ir-

127Ibid., 378. 454. Wolfson's theory that Philo believed in a creatio exnihilo (Philo 1. 295-324) has been challenged by Runia, who argues that Philo espoused a creatio continua (Philo and the Timaeus, 96-103. 140-57, 215-22. 280-83. 287-91. 416-20, 426-33, 451-56. 505-19). David Winston argues that he espoused a creatio aeterna (Philo of Alexandria: The Contemplative Life, the Giants, and Selections [New Jersey: Ramsey. 1981] 13-21). See the summary of the debate with an extensive bibliography in Gregory E. Sterling, "Creatio Temporalis, Aeterna, vel Continua? An Analysis of the Thought of Philo of Alexandria," Studia Philonica Annual 4 (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1992) 16-21. While Sterling defends Winston's position (pp. 21-41), I find Runia's more convincing.

128Philo Q. Gen. 3.48; 4.188; Runia remarks that "Philo makes surprisingly infrequent use of this common doctrine" (Philo and the Timaeus, 128). While it is true that only two explicit statements identify the cosmos as an organism, the figure of Nature herself belies a tendency on the part of Philo to think of the cosmos in these terms.

129Philo Q Gen. 3.3. ,30Philo Op mun 3, 143, 171; Spec leg 2.13; Abr. 5-6; Vit Mos 2.14, 48; John W.

Martens maintains that "the law of nature, except for its quality of préexistence, is contained in full in the law of Moses in Philo's work" ("Philo and the 'Higher' Law" [SBLASP; Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1991] 320; compare V. Nikiprowetzky, Le commentaire de l'écriture chez Philon d'Alexandrie [Leiden: Brill. 1977] 117-55). For a bibliography on those who hold the opposing position, see Martens, 309 n. 1.

,31Philo Q Exod 2.1; Chrysippus (the standard of reference for orthodox Stoicism) found "no fault with the universe since all is arranged according to the best nature" (Long, "The Stoic Concept of Evil," Philosophical Quarterly 18 [1968] 330-31).

1 2 4 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

regularities in the seasonal patterns can occur,132 but these are not due to any imperfection in Nature herself as a whole.133 Like the Stoics, Philo espouses an optimistic teleology: "the question before us is not whether the events are pleasant to us personally but whether the chariot and ship of the universe is guided in safety like a well-ordered state."1 3 4 While these phenomena may harm certain individual cells of the organism, ultimately they are to the benefit of the organism as a whole.135

Philo's view of the cosmos is thus multifaceted. The cosmos is at one and the same time a rational organism, fashioned by a semi-immanent Nature, and the creation of the transcendent God. This multifacted view of the cosmos accounts for Philo's tendency to pass back and forth within the same discourse between speaking about Nature and speaking about God.1 3 6

In this respect. Nature is not independent of God, for her teleological design and ordering of the cosmos are also his. It must be underscored, however, that this is an overlap: a region of intersection in a Venn diagram in which God's sphere is one of transcendence and Nature's sphere one of immanence with an overlapping region of transcendence. Nowhere in Philo are Nature and God identified.137 Nature is consistently differentiated from God; her primary arena of activity is located in the material world, while God is almost entirely removed from this sphere.138

It is important to stress that, as a figure, Nature herself in Philo does not ascend beyond the world of forms. While in Stoicism Nature and the Logos are identified,139 they are not identical in Philo. Perhaps this phenomenon is associated with a contrast Philo makes between "the Logos of Nature,"

1 3 2Philo S/?ec leg. 2.190-91. , 3 3Philo Provid 2.41-53. 1 3 4Philo Praem poen 34. I 3 5Philo Provid. 2.43-53: Sandbach suggests this modern terminology (The Stoics, 31-32).

Philo can resort to more traditional notions of divine recompense, and attribute these mishaps

to visitations against "impiety" (ασεβεί a) for the purpose of promoting virtue (Spec, leg

2.190-91: Provid. 2.41). Plutarch also cites some Stoic examples of the "old-fashioned notion

that plague and famine punish the wicked" (Long. "Evil," 331). 1 3 6For example, Philo Som. 1.103; Sacr AC 98-101: Spec leg 3.198-200. , 3 7With Martens, I must emphatically take issue with those scholars who have argued that

Nature and God are synonymous in Philo. These include Goodenough, By Light, Light, 31-54,

and Hans Leisegang, "Physis,"PW20.1 (1941) 1160-61. For a fuller list of commentators, see

Martens, "The Superfluity of the Law in Philo and Paul: A Study in the History of Religions"

(Ph.D. diss., McMaster University. 1991) 94 n. 158. The Philonic passages discussed here

should demonstrate the serious problems with such an identification. 1 3 8Runia (Philo and the Timaeus, 136-37) notes that, in the treatise De opificio mundi.

Philo does not dwell quite as intensely on God's transcendence in creation or on God's divine

intermediaries. He explains this as being due to Philo's desire in this treatise to avoid implying

there is more than one creator. ,39Long, Hellenistic Philosophy, l¿8-49.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 125

"by which things in the sense-perceptible world are analysed," and the divine Logos, which is found "in those forms which are called incorporeal, by which the things of the intelligible world are analysed."140 The former Logos overlaps with Nature, while the latter Logos is the twin brother of Wisdom. In short, the Logos seems to span the range of Wisdom and Nature put together, while Wisdom and Nature themselves inhabit distinct spheres. These distinct spheres are delineated in De virtutibus 6-8: while the "wealth of Nature" amply supplies the needs of the body and is available to all, there is a "higher, nobler wealth" which does not belong to all, namely the wealth bestowed by Wisdom.141

• A Schematic Overview of Wisdom, Sense Perception, Nature, and Philo's Gender Gradient

The diagram above offers a summary schematic representation of where Wisdom, sense perception, and Nature lie along Philo's gender gradient, with respect to God, the Logos, the mind, and other key components of Philo's worldview. A broken line is used to represent the division between the sense-perceptible world (κόσμος αισθητός) and the realm of the noetic-ideal (κόσμος νοητός), in recognition of the difficulties that exist in ascertaining precisely where this line is to be drawn.142 This attempt to place Wisdom, sense perception, and Nature along Philo's gender gradient does not pretend to be fully comprehensive; it is by no means an endeavor to provide a grand synthesis of Philo's thought. Although the gradient's presence can be detected often enough, it does not imply that all Philo's thought is determined or even necessarily influenced by this gender gradient. The schematic diagram is meant merely to help clarify in broad terms how these figures and Philo's concepts of gender are for the most part interrelated.

Beyond the peak of the gradient's positive "male" pole lies the transcendent God or Existent One (το öv), "who is better than the good, purer than the one and more primordial than the monad" (το öv, ο και αγαθού κρεΐττόν έστι και ενός ειλικρινέστερον και μονάδος άρχεγονώτερον).1 4 3

There are occasions when Philo asserts that God is beyond human apprehension, that one can only know that God is, not what he is.1 4 4 Here Philo

1 4 0Philo Q. Gen. 3.3; compare Migr Abr. 102. 1 4 1Compare Philo Provid frg. 1. 1 4 2 0 n the often fluid relationship between these two realms, see the diagram in Farandos,

Kosmos und Logos, 306. Also see the comments of Robert Mclver, "'Cosmology' as a Key to

the Thought-World of Philo of Alexandria," Andrews University Seminary Studies 26 (1988)

277 n. 11. 1 4 3Philo Vit. Cont 2; compare Praem. poen. 40. , 4 4Philo Praem. poen. 40, 44; Fug 165.

126 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

seems to place God beyond all categories of thought, including gender categories. In a certain sense, then, το όν lies beyond the scope of the gradient. Yet in De fuga et inventione 51, Philo explicitly calls the maker of all things "male" (άρρεν το τα ολα ποιούν) with respect to the very "male" Wisdom who is "female" only with respect to God himself. Moreover. Philo associates the true image of God with the rational or "male" part of the soul, while insisting that the irrational, corporeal or "female" has no part in this image.145 Thus it cannot be argued that the relationship of το öv to Philo's gender gradient is one of indifference. Given that the gradient is hierarchical, and το öv is envisaged as being higher than the gradient's "male" pinnacle, the transcendent God may even be said to be more "male" than "male," or "ultramale." I do not wish to push this argument too far, however; as indicated, there are instances where Philo exhibits a genuine reticence to define το öv using any of his philosophical categories. Nevertheless, there are other instances where Philo clearly positions the transcendent God at the utter "male" extreme of his gender gradient. In recognition of both these tendencies in Philo, I have placed το öv beyond and above the positive or "male" end of the gradient.

At the "female" pole of the gradient lies the primordial Unformed Matter (ή ύλη). It is so utterly alien to the transcendent God that it constitutes a kind of independent principle in itself, uncreated and eternal. All other aspects of Philo's cosmological/anthropological scheme lie somewhere in between these "male" and "female" poles, each being an admixture of varying degrees of the rational, active, and incorporeal (or "male" qualities) combined with varying degrees of the irrational, passive, and material (or "female" qualities). The relative proportions of "male" and "female" qualities embodied in a particular allegorized concept determine where it lies along the gender gradient.

Directly emanating from the transcendent God (το öv) at the "male" pole are Wisdom and the Logos—twin figures who relate both to God and to the human mind (ό νούς/ή διάνοια). As such, they serve as mediators between God and human understanding as well as between God and creation. These twin figures are one. They do not represent differentiated aspects of God, but are both his direct emanation, and as such are part of the indivisible or "monad." Being derived directly from the transcendent deity, they are positioned just below him on the gradient; being secondary to him, they possess some of the "female," expressed mostly in the figure of Wisdom. Overall, however, they are far more "male" than "female"— more "male" than all other components of Philo's cosmologica! scheme, except the transcendent God himself. In turn, the creative and ruling powers (θεός and κύριος) emanate from the Logos. By contrast to the Logos,

1 4 5Philo Rer div her 230-31; Op mun 69; see Baer, Philo's Categories, 21-26.

S H A R O N LEA MATTILA 127

these are differentiated aspects of the deity, and the world of forms is a further differentiation of the noetic-ideal.146 The four cardinal and other virtues are also differentiated emanations from Wisdom and the Logos.147

Of all the figures in the scheme, mind spans the broadest range along the gradient. Although fundamentally "male," under the influence of pleasure, passion, and sense perception, mind can plummet to the depths of the negative "female" pole of the gradient. Alternatively, through strenuous spiritual effort, mind can climb up to the heights of Wisdom/Logos, although he can never reach as far as the transcendent God himself.148

Wisdom, sense perception, and Nature have very little in common. Sense perception is enmeshed in the material, differentiated, and visible world. She is well removed from the undifferentiated, noetic-ideal realm of Wisdom/Logos. Philo often emphasizes the polarity between Wisdom and sense perception.149 His attitude toward the latter is heavily marked by ambivalence, reflecting his equivocating view of the material world as, on the one hand, the splendid creation of God and, on the other hand, a potential source of evil. While sense perception gives the mind the power to perceive the immediate and the visible, it is only through a mutual effort, in which she is largely the subservient party, that she can reach further into mind's invisible world. Sense readily plummets down into the passions, body and pleasure, with which she is closely associated, and thus she presents a constant threat, against which the mind must continually struggle.

The five senses themselves do not escape Philo's proclivity to arrange everything according to his gender-linked hierarchy.150 Sight is the "queen of the other senses" (βασιλίδα των άλλων), because the eyes play an active role in the perception of visible objects.151 The ears rank below the

, 4 6This has already been illustrated by Goodenough. See, for example, his diagram in An

Introduction to Philo Judaeus (2d ed.; Oxford: Blackwell. 1962) 105. It should be mentioned,

however, as Mclver ('"Cosmology,"' 277) observes, that Philo is not consistent in his enu

meration of the Powers. 147Wisdom is the fountain (πηγή), and Generic Virtue (here identified with the Logos) is

the river which divides into four "sources" ( α ρ χ ά ς ) or the four "specific" (είδος) cardinal

\irtues: prudence (ορόνησις) . self-mastery (σωφροσύνη), courage (ανδρεία), and justice

(δ ικαιοσύνη) (Leg all 1.64-65; cf. Som. 2.241-43). 1 4 8See, for example. Philo Som. 1.66; Praem poen 40; also see Runia" s discussion of the

limitations Philo imposes on humanity's quest for God (Philo and the Timaeus. 366). 1 4 9For example. Philo Leg all 2.49: 3.216-19. 243-45;/ter div her 53.98. I 5 0 ln Q Gen 3.5, 32. Philo ranks only four of the senses, since touch, he claims, "is

common to the (other) four." This parallels Aristotle who in De anima 2.2 (413b) declares that

"the primary form of sense is touch, which belongs to all the animals. . . touch can be isolated

from all other forms of sense" (The Basic Works of Aristotle [trans. J. A. Smith: ed. Richard

McKeon: New York: Random House, 1941]). 1 5 1Philo Abr. 149-50; Deus Immut. 79. Different varieties of the extramission hypothesis

of vision, in which the eyes are understood to be themselves sources of light and active in the

process of seeing, had become part of the common wisdom in antiquity, and are evident in

128 HARVARD T H E O L O G I C A L REVIEW

eyes because, as the passive recipients of sound, they are "more sluggish and effeminate (θηλύτερα) than eyes."1 5 2 Smell is "a mean between the good and the bad," for it is "clearer and purer than taste and touch," but "duller and more short-sighted than sight or hearing."153 Taste and touch are the "most animal and servile" of the senses.154

While Nature is the one who fashions (δημιουργέω) sense perception,155

unlike sense perception, she is not implicated in the lower parts of humanity, such as pleasure and the passions. And while she molded all the various mechanisms of the body, she is not linked with the body as the appetitive part of the soul. Neither does Nature span into Wisdom's territory beyond the world of forms. She is the active principle which shapes the ideas or paradigms derived from the world of forms into their corresponding corporeal objects in the material world. Both Wisdom and Nature are invisible, but their spheres of activity are distinctly separate. Wisdom's status is supracosmological, while Nature is, in a certain sense, the cosmos itself, albeit without the evils and imperfections inherent in the human microcosm.

As a perfect, uncreated, and eternal organism, Nature holds the status of a semi-immanent demiurge in some ways independent of God. This is not to suggest that Philo deliberately intended to style her as such. But this is the figure who emerges from his multifaceted understanding of the universe, its laws, and its origins—a view deriving from a desire to harmonize a Stoic-influenced popular philosophy with the Pentateuch. In addition, Nature's immanent aspect and predominantly material sphere of activity, inherited largely from Stoicism, conveniently spare the transcendent God and even his divine intermediaries from much involvement in the nuts and bolts of creation.

Of the three female figures, Nature is the most balanced in terms of her "male" and "female" attributes. Wisdom is decidedly "male" and sense perception decidedly "female." As the rational, active craftswoman who forms the various parts of the cosmos, Nature is "male"; in her semi-immanence and her material sphere of activity, she is "female." Yet she is

pagan, New Testament, and Jewish sources. See the summary of the sources in Dale C. Allison,

Jr., "The Eye is the Lamp of the Body (Matthew 6.22-23 = Luke 11.34-36)," NTS 33 (1987)

63-71. Philo opportunistically alternates between Plato's extramission-intromission theory of

vision (Timaeus 45B-46D) and the Stoic theory (see Ruma, Philo and the Timaeus, 231-33). 1 5 2Philo Abr 149-50. , 5 3Philo Q Gen 4.147. 1 5 4Philo Abr. 149-50: this presents an interesting contrast to Aristotle who observed.

"While in respect of all the other senses we fall below many species of animals, in respect of

touch we far excel all other species in exactness of discrimination. That is why [human beings

are] the most intelligent of all animals" (De anima 2.9: ET 421a). 1 5 5Philo for div her 53.

SHARON LEA MATTILA 129

not a composite of Wisdom and sense perception. For Philo, these latter female figures are important especially insofar as they relate to the human mind. Nature is a figure independent of the mind, even if the mind is capable of investigating her. In her perfection, she stands apart from humanity and its oscillation between good and evil, and this leaves her possessing less depth in Philo's overall scheme.

As the figures of Wisdom, sense perception, and Nature demonstrate, the breadth of Philo's female characterization in effect spans almost the entire range of his gender gradient. The single male figure of the mind, of course, spans this entire range on his own, possessing by far the greatest depth. Even if this is accomplished piecemeal, however, these female characters combined display all the capacity Philo's male characters do to attain to the heights and plunge to the depths of his gender gradient. Only the transcendent deity lies beyond their sphere, who also lies beyond the sphere of either mind or Logos.

This phenomenon, intriguing as it is, does not diminish the offense to a modern feminist critic caused by the gender gradient's pervasiveness and rigidity. It must not be forgotten that gender "is a powerful ideological device, which produces, reproduces, and legitimates the choices and limits that are predicated on sex category."156 Yet the figures of Wisdom and Nature would imply that, with respect to the organic mythology that sprang out of Philo's concrete world, the power of this ideological device had its limits.

l56West and Zimmerman, "Doing Gender," 34.

^ s

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement.