Where Is “Community” in Community-Based Forestry?

Transcript of Where Is “Community” in Community-Based Forestry?

This article was downloaded by:[EBSCOHost EJS Content Distribution]On: 7 July 2008Access Details: [subscription number 768320842]Publisher: Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Society & Natural ResourcesAn International JournalPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713667234

Where Is “Community” in Community-Based Forestry?Courtney G. Flint a; A. E. Luloff b; James C. Finley ca Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University ofIllinois, Urbana, Illinois, USAb Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, Pennsylvania StateUniversity, University Park, Pennsylvania, USAc School of Forestry, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania,USA

Online Publication Date: 01 July 2008

To cite this Article: Flint, Courtney G., Luloff, A. E. and Finley, James C. (2008)'Where Is “Community” in Community-Based Forestry?', Society & Natural Resources, 21:6, 526 — 537

To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/08941920701746954URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08941920701746954

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expresslyforbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will becomplete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should beindependently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with orarising out of the use of this material.

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

Policy Reviews

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-BasedForestry?

COURTNEY G. FLINT

Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences,University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA

A. E. LULOFF

Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology,Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA

JAMES C. FINLEY

School of Forestry, Pennsylvania State University, University Park,Pennsylvania, USA

Community-based forestry and community-based natural resource managementhave become increasingly common terms in both the scientific and popular press.However, as with so many other concepts currently in vogue, rarely do studiesinvoking them incorporate either a grounded theoretical understanding or prac-tical inclusion of the central term: community. Community emerges through com-munication and interaction among people who care about each other and theplace they live. In its purest form, community is marked by its multiple and oftenconflicting perspectives. This article draws upon recent research experience withthe Ford Foundation’s community-based forestry initiative to illustrate theimportance of solidly framing community in order to successfully link forestecosystem management with community well-being.

Keywords community, community-based forestry, community-based naturalresource management

Community-based forestry and community-based natural resource management havebeen increasingly employed to describe a wide range of activities associated withthe use and management of natural resources in rural and small town settings. Onthe surface, invoking these terms elicits positive connotations. Such terms recollectand are associated with a sense of grass-roots citizen participation that brings thegoals of sustainable natural resource management and community well-beingtogether.

Received 7 October 2005; accepted 29 June 2007.Address correspondence to Courtney G. Flint, Department of Natural Resources and

Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois, 1023 Plant Sciences Laboratory, MC-634,1201 S. Dorner Dr., Urbana, IL 61801, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

Society and Natural Resources, 21:526–537Copyright # 2008 Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 0894-1920 print/1521-0723 onlineDOI: 10.1080/08941920701746954

526

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

Beneath the surface, however, it is clear that no shared conceptual understand-ing or use of the core concept—community—exists. A recent review of its use innatural resource management studies associated with the International Symposiaon Society and Resource Management and Society & Natural Resources articlesunderscored the elusive nature of the community concept (Luloff et al. 2004). Com-munity has been treated as both unit and level of analysis, as a central and peripheralconcept, and as an independent and dependent variable (Luloff et al. 2004).

Such slippage does little to anchor community’s relevance to natural resourcemanagement issues. Brosius et al. (1998) urged a more cautious approach, callingfor a continued movement toward uniformity in terminology. Regardless, researcherscontinue to provide ambiguous definitions for their use and application of communityprocesses in research and practice. If our efforts are truly focused on local empower-ment through participation in natural resource management decision making, thenresearchers and policymakers need to better define and operationalize community.Absent grounding to a coherent theoretical framework, a proper understanding ofthe role and place of community in natural resource issues will not be advanced.

Community-Based Forestry and Community-BasedNatural Resource Management

In general, we suspect there would be broad agreement over the goals articulated bymany working in the area of community-based forestry=natural resource manage-ment. According to the National Forest Foundation (2006), ‘‘The aim of com-munity-based forestry is to empower those who work, live, and recreate in thewoods to organize and strive toward a common set of goals.’’ Similarly, Bakerand Kusel (2003, 8) identified community forestry’s objective as being ‘‘to conserveor restore forest ecosystems while improving the well-being of communities thatdepend on them.’’

Not only are these worthy goals of collaborative efforts, they generate the goodfeelings often associated with community involvement (Daly and Muir 1998). A reviewof recent literature invoking the notion of community-based forestry=natural resourcemanagement suggested a common practice of using community to refer to almost any-thing, regardless of who was involved, including special-interest groups or smallgroups of citizens (cf. Brunner 2002). Also, community has been used in efforts orig-inating at a state scale or within nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to attractattention to hyped public participation frames (cf. Brunner 2002; Whitman and Geis-ler 2005). An inherent risk to such practices is the failure to reflect the multiplicity ofvalues and interests present within any given community. Such failure contributes tothe marginalization of voices and needs (Agrawal and Gibson 2001).

Many studies portray communities as being unified, organic, homogeneouswholes without conceptualizing or recognizing the complexity and diversity foundwithin them or how these differences affect natural resource-based outcomes(Agrawal and Gibson 2001). Continued vague and ambiguous use of thecommunity term diffuses the ability to achieve the ultimate goal—broadening thedecision-making structure to include those with relevant local natural resourceknowledge. The nonmarginalization of these people is best achieved by broadeningthis decision making structure.

Community-based forestry and=or natural resource management is generallyfound in studies of developing countries. Typically, these studies occur in places

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based Forestry? 527

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

where land is either communally owned or held by the central government. The latteris often associated with ambiguity over access to these forest resources, resultingin the emergence of seemingly ‘‘common pool resource’’ characteristics (cf. Gauld2000; McKean 2000; Gray et al. 2001; Pardo 1985; 1993; 1995; Whitman andGeisler 2005).

In contrast, American communities rarely own significant acreages of forest ornatural resource assets. Such a difference in possession reflects a common stumblingblock to community involvement in natural resource management in the UnitedStates. Here, generally, privatization has been associated with the diminution ofcentral government control over natural resources in and around communities. Thisis no small distinction. In many developing countries resources are shared—amonglocal residents and between residents and the central government.

Such sharing requires communal decision making and local involvement in dayto day management for sustainable use over the long term. In the United States,resources are sometimes figuratively shared, but management decisions are madein a complex jurisdictional mosaic where private landholders maintain control overtheir land and resources while public land is managed in a bureaucratic, top-downapproach. However, despite differences in community land ownership patterns inter-nationally, inadequate conceptualizations of community remain common (Kumar2005; Whitman and Geisler 2005). Variations in conceptualizations of communityin the context of natural resource management are also expected between countrieseven within developed regions, given their different cultural, biophysical, and policycontexts. Community forestry in Canada, for example, is framed quite differentlythan in the United States (Shindler et al. 2003).

Land ownership and management authority have important implications forcommunity-based natural resource management. The promotion of communitywithin the context of natural resource management needs to build on and extendexisting management and science across ownership contexts. For example, someadvocates of community-based forestry=natural resource management reflect anantagonistic approach through their suggestion that control be wrested from tra-ditional gatekeepers (Baker and Kusel 2003, 1). Such antagonism is unlikely to facili-tate collaborative resource management among the wide range of stakeholders, landmanagers, and landowners. Where communities neither own the land nor havedefined collective rights to local natural resources, the value of a community-basedapproach is its ability to raise the level and quality of dialogue and participation innatural resource management decision making. To more fully understand the role ofsuch interaction, a more careful articulation of ‘‘community’’ is needed.

Defining Community

Community in almost every use implies some level of interaction. It does not mean nor isit reflected by a measure of capital—economic, human, social, natural, or any other per-mutation. Such reductionism demeans the value of local people interacting over com-mon concerns. Nor is interaction measured with simple sociodemographic data.Community is what people who care about each other and the place they live createas they interact on a daily basis (Wilkinson 1991; Flint and Luloff 2005; 2007). Rarelycan communities be characterized as homogeneous groups of like-minded people.

Community is an emergent phenomenon. It arises through the concerted actionsof locals who are tied to a place by their shared values, concerns, interests, and

528 C. G. Flint et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

actions. We believe that it is only in such places, that a commitment to community-based forestry—or more importantly, community-based anything—can occur. Such adefinition is drawn from the work of Kaufman (1959) and Wilkinson (1970; 1991),who developed the interactional conception of community. According to this frame-work, where there is common space, shared way of life, and collective actions, localcitizens are able to overcome petty differences and special interests to recognize thecommon good. In such places, community emerges when the conditions are right—and it lasts as long as the people in an area continue to care about each other and theplace, and express this caring in the actions they take to enhance general well-being.The mobilization of locality-based, collective human resources is a significant andgenerally ignored feature of community. Indeed, we think it is the signal character-istic of place—and the vital ingredient to explain what makes a place a community.

Our framework takes social interaction as the central element of community—that is, community emerges from social interaction. Community, from this perspec-tive, occurs in places and is place oriented, but the place itself, strictly speaking, isnot the community. Instead, community is conceptualized as a process of place-oriented social interactions that express shared interests among residents of a localsociety and are expressed in prevailing local narratives. Use of the interactionalapproach in rural and small town settings directs attention to forces that blockor retard the emergence of the interactional community in particular settlements(Wilkinson 1986; Luloff and Swanson 1995). Without such interaction, thebottom-up processes essential to involving local people in decision making arestymied.

People have the capacity to manage, utilize, and enhance the resources availableto them. We call this ability to act community agency and define it simply as thecapacity for collective action (Luloff and Swanson 1995; Luloff and Bridger 2003).It is one of the most important dimensions of a community’s social infrastructureand using it places attention on the key natural resource a place has—its people.When we use the term community agency, we focus our attention on the comingtogether of people in a local society to address local needs. These folks may haveintense conflicts or be of like mind, it really does not matter, but the will to act col-lectively comes from their recognition of shared needs and concerns. Communityagency should not conjure up romantic notions of strong local solidarity. The collec-tive capacity of volition and choice, however narrowed by structural conditions,makes community agency a central element in local well-being and in understandingwhat makes a place a community. That is, communities make choices and act onthem. Knowing how these choices are made, what and how perceptions of localissues are constructed, and the ability of members of such communities to accessand process information are essential elements in the utilization of economic, social,and natural resource endowments.

Emphasizing ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based NaturalResource Management

Emphasizing the shared concerns and the capacity for community agency using thecommunity framework described earlier brings meaning to the concept and prac-tice of community-based forestry or community-based natural resource manage-ment. Including multiple perspectives and articulating shared identity and valueshelps guide the dual, intersecting processes of promoting ecological and community

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based Forestry? 529

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

well-being (Orr 2004; Wilkinson 1991). However, community-based objectives arerarely easily stated and the process of achieving them is both arduous and poten-tially conflicting. Advocates of community-based natural resource managementwould do better to focus on bringing people together instead of jumping straightinto outcome-based planning and action. Through interaction, communication,and the articulation of what people share, the opportunity arises for communityto emerge. In the rare case where values and goals coincide, decisions andimplementation of plans are streamlined. Most of the time, life is far more com-plex. Simply measuring the success of community-based natural resource manage-ment as the attainment of specific outcomes or results is unrealistic and likely tolead to disappointment.

Community-based natural resource management is generally a slow process—one that evolves, reflecting open discussions of often conflicting local interpretationsand interests. Exclusive emphasis on consensus keeps important issues from theirrightful place at the table. Community-based forestry involves local citizens indialogue and decision making about forest resources precisely because of their sig-nificant knowledge and information about the broader community and theircommitment to local environmental resources.

Thus, the measure of success for community-based natural resource manage-ment is found in the inclusion of multiple, conflicting perspectives, and in the emerg-ence of interaction and dialogue. Bringing people together in the name of managingnatural resources for the benefit of the community and the environment in whichthey share common interests is a solid reason for natural resource scientists to careabout and use a community-based natural resource management approach.

Our work in community and natural resource studies suggests that how projectsare framed, especially in the context of community-based forestry=natural resourcemanagement has direct implications for whether or not progress is made in articulat-ing goals and objectives. The Ford Foundation’s Community-Based Forestry initiat-ive provides clear examples of how paying lip service to community detracts from theoverall progress and success of participatory natural resource management efforts.Also, this initiative provides important lessons on how clear framing, understanding,and inclusion of the community can lead to the creation of more sustainable, localnatural resource management efforts and results. Without such an understandingof community, locally based forestry efforts are just that—local.

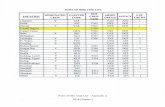

The Ford Foundation and Community-Based Forestry

In 1999, The Ford Foundation initiated a Community-based Forestry Demon-stration Program to address a wide array of issues in purposively selected forest-dependent communities characterized by high poverty rates. Ford’s effort wasguided by the premise that community-based forestry was an effective and sustain-able strategy for forest restoration and conservation, community strengthening,and poverty alleviation. The major goal of its project was to foster accelerated dif-fusion of best-practice strategies for forest and other forest-related resource manage-ment, while engaging local communities in the decision-making process (AspenInstitute 2005). In its initial stage, the Ford program included 12 self-designatedcommunity-based organizations involved in local natural resource managementand economic development (see Table 1).

530 C. G. Flint et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

Table 1. Ford initiative organizations, locations and goals

Organization Place Goals

Alliance of ForestWorkers and Harvesters

Pacific Northwest 1) Marketing nontimber forestproducts

2) Conflict resolution3) Harvester education and

certification4) Teaching English as second

languageJobs and Biodiversity Silver City (Grant

Co.), New Mexico1) Forest restoration and

ecological integrity2) Jobs and active participation

in communityDelta Montrose Ouray

Public LandsPartnerships

Western Colorado 1) Adding value to ranchoperations

2) Mule deer habitatrestoration

3) Recognition and marketingfor indigenous products

4) Cowboy-logger demonstrationproject

Federation of SouthernCooperatives

Epes (Sumter Co.),Alabama

1) Education2) Technical assistance3) Entrepreneurship4) Demonstration

Makah Tribal Council Neah Bay, Washington 1) Healthy, productive forestsfor future generations

2) Develop nontimber forestresources

New England ForestryFoundation

North QuabbinRegion,Massachusetts

1) Small landownercertification, chain ofcustody and marketing

2) Training in recreationservices

3) Selling shared pride incommunity and products

Penn Center Incorporated Island communities,Georgia and SouthCarolina

1) Revitalization strategies2) Developing a forest

products sector3) Identify and promote

sectoral networks forcommunity conservationand forest products andmarkets

(Continued)

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based Forestry? 531

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

Methods and Project Description

The authors’ involvement centered on the implementation of a monitoring andassessment process that relied, in large part, on case studies of each organizationand=or community. Their participation in the project included site visits, regularlyscheduled interviews with the 12 community-based organizations selected by Fordfor participation in the project and their principals, key informant interviews1 witha cross-section of community leaders and participants, review of relevant local orstate documents, and analysis of all written project documents (e.g., proposals,project reports, and the like). No data were available from the Alliance of ForestWorkers in Portland, OR.

Participation by the authors with the Ford Foundation’s CBF DemonstrationProgram occurred from 2000 to 2004. The project continued after our involvementended, and more recent updates on the Ford Community-Based Forestry Project canbe found elsewhere (Aspen Institute 2005).

Table 1. Continued

Organization Place Goals

Rural Action Trimble, Ohio 1) Nontimber forest productsproduction and marketing

2) Forest restorationSustainable Northwest Southwestern Oregon 1) Build local capacity

2) Use media to create brandname

3) Third-party certification4) Technical assistance5) Working partnerships

among communitiesWallowa Enterprises Wallowa, Oregon 1) Improve forest ecosystems

2) Generate sustainable localbenefits from resources

Watershed Research andTraining Center

Hayfork, California 1) Log sorting yard for small-diameter timber

2) Create a value-added forestproducts center for trainingand business incubation

3) Secondary manufacturingand forest restorationbusiness development

Working Forests forVermont WorkingFamilies

Addison County,Vermont

1) Implement sustainableforestry practices togenerate income

2) Develop green certifiedproducts

3) Management cooperative tobenefit low-income members

532 C. G. Flint et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

The 12 Ford-funded organizations represented an eclectic set of projects (seeTable 1). An organization’s involvement was premised on an agreed upon mutualsharing of experiences under the auspices of community-based forestry. However,there was a strong disconnect between the organizational use of the termcommunity-based forestry by the both the Ford Foundation and its local partnersand the place-based or community-based references of local residents attemptingto link natural resource management to broad-based community well-being. The fullset of Ford Foundation Projects reflected a very mixed set of goals, which isexpected, but they lacked a common thread to bind them together. Communitywas not a common element. We suggest it should have been.

Research Findings

Based on analysis and synthesis of interview data, site visits, and program evalua-tions, only four of the 12 cases had the potential for community-based forestry totruly be about community. These included the community-based forestry efforts inWallowa, OR; Hayfork, CA; Neah Bay, WA; and Trimble, OH. In these cases, com-munity and the integration of multiple interests and strategies among communityresidents were at the heart of their community-based forestry efforts despite the dif-ficult and often conflict-laden process of bringing people together. Interaction anddialogue clearly played a role in these four cases as efforts were made to link forestmanagement processes with a greater sense of community well-being. Three themesfrom these cases reveal community at the core of their forest management efforts: (1)linking natural resource management with broader concerns about community well-being; (2) appreciating the need to incorporate multiple interests regardless of theconflict this engendered; and (3) recognizing community and resource managementas processes, not endpoints, and the importance of change.

Several examples articulate the connections between local forest managementinitiatives and broader shared commitment to community well-being. In Hayfork,CA, through the efforts of the Watershed Research and Training Center (WRTC),emphasis was placed on using and restoring forests in new, creative ways to havewide-reaching implications for the broader community. Forest management planswere envisioned as enhancing employment opportunities, reducing fire hazard,restoring disturbed forests, and improving area amenities for a higher quality of lifefor residents. A response from a Hayfork key informant encapsulated this sentiment:

I would like to see a thriving business incubator that spins off meaning-ful, relatively well-paying jobs. I want to see a healthier landscape thatresists fire and is in a state of recovery . . . a happy healthy valley.

In Neah Bay, forest management initiatives related to timber and nontimber for-est products through the Makah Forest Enterprise (MFE) were envisioned as effortsto address some critical problems within the community, including poor educationalaccess and quality, drug and alcohol abuse, and the need for economic motivation.In Trimble, OH, the forest management activities of Rural Action were clearly tiedto the realization of a broader need to address the classic Appalachian povertyexperienced in the community. High unemployment, low incomes, and welfaredependence were defining properties of the economic setting in Trimble and othernearby communities. In Rural Action’s region of influence there was little difference

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based Forestry? 533

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

of opinion among respondents about the degree of poverty in the area. The inter-views contained multiple descriptions of the region’s abject poverty, its desperateneed for help, and its widespread deprivation. Rural Action was widely regardedby community residents as leading the movement toward a sustainable communityeconomy using natural resources and emphasizing the production of nonforest tim-ber products, such as mushrooms and herbs (e.g., ginseng and goldenseal) as nutra-ceutical products. Rural Action’s efforts were serving as a catalyst for communityagency in the Trimble, OH, community.

Truly community-based Ford Foundation Projects readily acknowledged themultiple interests of diverse stakeholders and made efforts to build dialogue amongthese people while still recognizing the inherent conflict and associated difficulties.For example, the complexity and challenge of attempting to transition from tra-ditional large-scale timber harvesting to creative local alternatives in Wallowa,OR, is tied to the key role of multiple stakeholders:

Natural resource-based economies are going to change. This requireschange in attitudes by natives, immigrants, and retirees. Lots of possiblesolutions exist, but none is likely to have broad based support.

Perseverance in spite of competing interests and complexity is a clear sign of anemerging community process that lies at the foundation of community-based naturalresource management efforts.

Anticipating the need for change in community elements beyond specific forestmanagement goals is an indication of a vision of community and community-basednatural resource management as processes rather than endpoints or clear outcome-based objectives. For example, MFE in Neah Bay recognized the need for retoolingand retraining its community members to keep up with changing emphases withinforest management and related economic development:

Members of the community need training in the use and harvesting ofalternative forest products, especially sustainable harvesting. To marketthe products they have to understand the market demands and packagingneeds. Most importantly, they have to find more outside buyers.

Neah Bay’s forest management initiative reflected community members’ under-standing of the need to better position the community to be successful in a broadercontext.

The other projects within the Ford Foundation’s Community-Based ForestDemonstration Program were never community structured. For example, in Addi-son County, Vermont (Working Forests for Vermont’s Working Families), and insouthern Oregon (Sustainable Northwest), community was never a defined compo-nent to the organizational efforts. Instead, sets of individuals or groups—not com-munities—were interested in participating in forest or natural resourcemanagement projects. Even when organizations were more specifically place-based,significant portions of community populations were neither participants nor targetedrecipients in the CBF goals. This was the case with Penn Center in South Carolinaand Georgia, Jobs and Biodiversity in Silver City, NM, and the Federation of South-ern Cooperatives in Epes, AL, where social and racial lines continued to divideparticipation in natural resource and community projects. One key informant

534 C. G. Flint et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

from Epes, AL, articulated this problem by saying, ‘‘There is no trust along raciallines. There is no real interaction between the races other than at work.’’ Withoutdialogue and interaction, key stakeholders were excluded from important decisionsregarding natural resource management and community-level decisions thereby lim-iting the potential for community agency.

The Delta Montrose Ouray Public Lands Partnership in Colorado and the NewEngland Forestry Foundation in the North Quabbin region of Massachusetts hadmultiple natural resource objectives beyond forestry and lacked clear focus on thelinkages between forest resources and community well-being. In sum, the majorityof Ford Projects did not have community at the core of their natural resource or for-est management efforts. This may explain the lack of glue or collective focus amongthese initiatives.

A participant from Wallowa, OR, illustrated a key component of what webelieve should be at the core of our interpretation of community-based forestry:‘‘(Community-based forestry) bridges community and agency, bringing folks togetherto find solutions.’’ Despite variations in scope, strategy, geographic location, andinner tensions, the organizations funded by the Ford Foundation Program were seenmore positively and more likely to succeed in communities where people, fromdifferent and often competing perspectives, came together to address communityproblems.

Concluding Thoughts and Implications

Efforts to localize forest management efforts that are not community-based haveboth purpose and contribution, but are marked by different focus and goals whencompared with efforts that are truly community-based. Perhaps non-community-based forest management efforts should be called ‘‘locally-based forestry’’ or‘‘locally-based natural resource management’’ or even ‘‘regionally-based naturalresource management’’ to indicate a larger spatial scope when and where relevant.Such efforts may involve special interest groups and=or networks of producersand marketers across a regional area. When the goal of locally based naturalresource management is to use the processes of interaction and dialogue amongthose sharing common interests in their place and community and who view resourcemanagement as a means of collective action toward achieving greater ecological andcommunity well-being, then community-based forestry or community-based naturalresource management would be appropriate descriptions.

However, simply invoking community in discussions and efforts relating toaccess to and management of forest and other natural resources without a clearunderstanding of the term in frameworks, methods, and implementation endangersefforts to link natural resource management with improvements in community well-being. Few attempts at assessing community-based forestry=natural resource man-agement in the U.S. context are truly about community. Where they are, it is causefor celebration—not because they have achieved some end product or nirvana in for-est management, but because they have succeeded in creating community dialogue.Bringing people who previously wouldn’t have been seen together on the same streetto learn they share common values and commitment to a shared place is a criticalstep toward ensuring continued dialogue and problem solving.

Our analysis of the Ford Foundation’s Community-based Forest Demon-stration Program revealed that when forest management efforts were not about

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based Forestry? 535

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

community there was often an incomplete articulation or recognition of sharedvalues and=or relatively little effort to tie the people and places affected by manage-ment decisions or plans together. The admirable goals of community-basedforestry—addressing the dual mission of restoring forest ecosystems and improvingcommunity well-being—are likely to remain elusive until we begin to ground our stu-dies more carefully. When we collectively recognize the value of framing communityas an emergent process among a multiplicity of local voices we will be better able toidentify and work on shared interests.

What the communities involved in the Ford Program wanted was the ability toaccess resources and use them in constructive ways that they saw as relevant withouthaving to shape their approach to extralocal forces. Contrary to a recent perspectivearticulated in American Forests (Gray 2007), community-based forestry is not anational dialogue, nor do local efforts typically seek to engage national policy.The focus of community-based forestry is and should remain at the local level, wherelocal people come together to manage and utilize local natural resources in ways thatblend multiple dimensions of community and ecological well-being.

Note

1. Key informants are individuals who are knowledgeable about community affairs and arerepresentative of particular community perspectives (Krannich and Humphrey 1986; Luloff1999).

References

Agrawal, A. and C. C. Gibson. 2001. Communities and the environment: Ethnicity, gender, andthe state in community-based conservation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Aspen Institute. 2005. Growth rings: Communities and trees. Washington, DC: The AspenInstitute.

Baker, M. and J. Kusel. 2003. Community forestry in the United States: Learning from the past,crafting the future. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Brosius, J. P., A. Lowenhaupt Tsing, and C. Zinner. 1998. Representing communities: Histor-ies and politics of community-based natural resource management. Society Nat.Resources 11(2):157–168.

Brunner, R. D. 2002. Problems of governance. In Finding common ground: Governanceand natural resources in the American West, eds. R. D. Brunner, C. H. Colburn,C. M. Cromley, R. A. Klein, and E. A. Olson, 1–47. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Daly, C. and M. Muir. 1998. Repairing the system. Am. For. 103(4):32–35.Flint, C. G. and A. E. Luloff. 2005. Natural resource-based communities, risk, and disaster:

An intersection of theories. Society Nat. Resources 18(5):399–412.Flint, C. G. and A. E. Luloff. 2007. Community activeness in response to forest disturbance in

Alaska. Society Nat. Resources 20(5):431–450.Gauld, R. 2000. Maintaining centralized control in community-based forestry policy construc-

tion in the Philippines. Dev. Change 31(1):229–254.Gray, G. 2007. Putting community in forestry. Am. For. 113(1):11–13.Gray, G. J., M. Enzer, and J. Kusel. 2001. Understanding community-based forest ecosystem

management. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.Kaufman, H. F. 1959. Toward an interactional conception of community. Social Forces

38(October):9–17.Krannich, R. S. and C. R. Humphrey. 1986. Using key informant data in comparative com-

munity research. Sociol. Methods Res. 14(4):473–493.

536 C. G. Flint et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[EB

SC

OH

ost E

JS C

onte

nt D

istri

butio

n] A

t: 18

:55

7 Ju

ly 2

008

Kumar, C. 2005. Revisiting ‘community’ in community-based natural resource management.Commun. Dev. J. 40(3):275–285.

Luloff, A. E. 1999. The doing of rural community development research. Rural Society9(1):313–327.

Luloff, A. E. and J. C. Bridger. 2003. Community agency and local development. In Challengesfor rural America in the 21st century, eds. D. Brown and L. Swanson, 228–241. UniversityPark, PA: Penn State Press.

Luloff, A. E., R. S. Krannich, G. L. Theodori, C. Koons Trentelman, and T. Williams. 2004.The use of community in natural resource management. In Society and natural resources:A summary of knowledge, eds. M. J. Manfredo, J. J. Vaske, B. L. Bruyere, D. R. Field,and P. J. Brown, 249–259. Jefferson, MO: Modern Litho.

Luloff, A. E. and L. E. Swanson. 1995. Community agency and disaffection: Enhancingcollective resources. In Investing in people: The human capital needs of rural America,eds. L. J. Beaulieu and D. Mulkey, 351–372. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

McKean, M. A. 2000. Common property: What is it, what is it good for, and what makes itwork? In People and forests: Communities, institutions, and governance, eds. C. C. Gibson,M. A. McKean, and E. Ostrom, 27–55. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

National Forest Foundation. 2006. Community-based forestry. http://www.natlforests.org/consi_01_comm.html (accessed 15 May 2007).

Orr, D. W. 2004. Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect.Washington, DC: Island Press.

Pardo, R. 1985. Forestry for people: Can it work? J. For. 83(12):733–741.Pardo, R. 1993. Back to the future: Nepal’s new forestry legislation. J. For. 91(6):22–26.Pardo, R. 1995. Community forestry comes of age. J. For. 93:20–24.Shindler, B. A., T. M. Beckley, and M. C. Finley. 2003. Two paths toward sustainable forests:

Public values in Canada and the United States. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.Whitman, H. and C. Geisler. 2005. Negotiating locality: Decentralization and communal

forestry management in the Guatemalan highlands. Hum. Organiz. 64(1):62–74.Wilkinson, K. 1970. Phases and roles in community action. Rural Sociol. 35(March):54–68.Wilkinson, K. 1986. In search of the community in the changing countryside. Rural Sociol.

51(1):1–17.Wilkinson, K. 1991. The community in rural America. Middleton, WI: Social Ecology Press.

Where Is ‘‘Community’’ in Community-Based Forestry? 537