What really improves employee health and wellbeing

Transcript of What really improves employee health and wellbeing

International Journal of Workplace Health ManagementWhat really improves employee health and wellbeing: Findings from regional AustralianworkplacesVirginia Dickson-Swift Christopher Fox Karen Marshall Nicky Welch Jon Willis

Article information:To cite this document:Virginia Dickson-Swift Christopher Fox Karen Marshall Nicky Welch Jon Willis , (2014),"What reallyimproves employee health and wellbeing", International Journal of Workplace Health Management, Vol. 7Iss 3 pp. 138 - 155Permanent link to this document:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-10-2012-0026

Downloaded on: 16 September 2014, At: 16:13 (PT)References: this document contains references to 43 other documents.To copy this document: [email protected] fulltext of this document has been downloaded 21 times since 2014*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:Lydia Makrides, (2008),"Editorial", International Journal of Workplace Health Management, Vol. 1 Iss 1 pp. -S. Lee, H. Blake, S. Lloyd, (2010),"The price is right: making workplace wellness financially sustainable",International Journal of Workplace Health Management, Vol. 3 Iss 1 pp. 58-69Jennifer K Dimoff, Kevin Kelloway, Aleka M. MacLellan, Paul Sparrow, Paul Sparrow, (2014),"Health andPerformance: Science or Advocacy?", Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance,Vol. 1 Iss 3 pp. -

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided byToken:JournalAuthor:C7FE8F60-EB76-4F4F-AB51-5C5DBECBD4DF:

For AuthorsIf you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald forAuthors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelinesare available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.comEmerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The companymanages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well asproviding an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committeeon Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archivepreservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

What really improves employeehealth and wellbeing

Findings from regional Australian workplacesVirginia Dickson-Swift

Rural Health School, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia

Christopher FoxFaculty of Medicine – Sexually Transmitted Infections Research Centre,

University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Karen MarshallRural Health School, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia

Nicky WelchPrevention & Population Health Branch, State Government of Victoria,

Melbourne, Australia, and

Jon WillisAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, University of Queensland,

Brisbane, Australia

Abstract

Purpose – Factors for successful workplace health promotion (WHP) are well described in theliterature, but often sourced from evaluations of wellness programmes. Less well understood arethe features of an organisation that contribute to employee health which are not part of a healthpromotion programme. The purpose of this paper is to inform policy on best practice principles andprovide real life examples of health promotion in regional Victorian workplaces.Design/methodology/approach – Individual case studies were conducted on three organisations,each with a health and wellbeing programme in place. In total, 42 employers and employeesparticipated in a face to face interview. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and the qualitativedata were thematically coded.Findings – Employers and senior management had a greater focus on occupational health and safetythan employees, who felt that mental/emotional health and happiness were the areas most benefitedby a health promoting workplace. An organisational culture which supported the psychosocial needsof the employees emerged as a significant factor in employee’s overall wellbeing. Respectful personalrelationships, flexible work, supportive management and good communication were some of the keyfactors identified as creating a health promoting working environment.Practical implications – Currently in Australia, the main focus of WHP programmes is physicalhealth. Government workplace health policy and funding must expand to include psychosocialfactors. Employers will require assistance to understand the benefits to their business of creatingenvironments which support employee’s mental and emotional health.Originality/value – This study took a qualitative approach to an area dominated by quantitativebiomedical programme evaluations. It revealed new information about what employees really feel isimpacting their health at work.

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available atwww.emeraldinsight.com/1753-8351.htm

Received 17 October 2012Revised 11 November 2013Accepted 10 January 2014

International Journal of WorkplaceHealth ManagementVol. 7 No. 3, 2014pp. 138-155r Emerald Group Publishing Limited1753-8351DOI 10.1108/IJWHM-10-2012-0026

This study was funded by the State Government of Victoria Department of Health. The authorswould like to acknowledge the contribution of the State and Regional Department of Health andBendigo Community Health Services as partners in this project, as well as the participatingorganisations and their employees.

138

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Keywords Australia, Organizational culture, Qualitative research, Workplace health,Health promotion, Mental and emotional health

Paper type Research paper

IntroductionGlobally the workplace has been recognised as a key contributor to the health andwellbeing of working-age people (European Network of Workplace Health Promotion,2005; Black, 2008; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2010). Healthpromotion in the workplace has been broadly recommended by international bodiesthrough numerous charters and declarations, including the 1986 Ottawa Charter forHealth Promotion, the 1997 Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion intothe 21st Century and the 2005 Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a GlobalizedWorld (World Health Organization, 2008). The European Network for WorkplaceHealth Promotion has issued a number of statements in support of WHP, including theLuxembourg Declaration on Workplace Health Promotion in the European Union,the Lisbon Statement on Workplace Health in Small and Medium Sized Enterprisesand the Barcelona Declaration on Developing Good Workplace Health Practice inEurope (European Network of Workplace Health Promotion, 2005). In addition to thesethere are a number of other programmes in place across the US, UK, Canada andNew Zealand (European Network of Workplace Health Promotion, 2005; BuckConsultants, 2008; Bull et al., 2008; Health Work and Wellbeing UK, 2008).

The workplace has been recognised as a key contributor to the health and wellbeingof individuals since the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion stated “work and leisureshould be a source of health for people” (World Health Organization, 1986). Morerecently a Global Plan of Action on Worker Health was endorsed by the World HealthAssembly in 2007 (World Health Organization, 2007) and in 2009 the WorldHealth Organization released a comprehensive model for action that advocates for anapproach to worker health which incorporates physical health, psychosocial health,healthy behaviours and environmental determinants (World Health Organization,2010). Promoting health in the workplace improves employee health and wellbeing,enhances productivity and therefore the success of organisations (Harden et al., 1999;Benedict and Arterburn, 2008; Black, 2008). The reduction of risk factors for lifestylediseases will improve health status and reduce the burden of disease (AustralianInstitute of Health and Welfare, 2010). There is strong evidence that small widespreadchanges to the workplace environment can result in significant health improvementsfor workers and their families (Makrides et al., 2007; Bellew, 2008; Black, 2008).

WHP can be any activity that aims to improve or promote the physical or mentalhealth and wellbeing of employees in their workplace. The range of different rolesand job sites mean that this is necessarily a broad and encompassing definition (Hymelet al., 2011). Traditionally workplace health has concentrated on occupational healthand safety (OH&S) measures with the aim of reducing physical harms and injury toemployees. Many employers continue to view their obligations to the requirementsof OH&S laws as the extent of their role or responsibility in their employees’ health andwellbeing. The value of supporting employee health results in positive outcomes forthe organisation as a whole with reported increases in productivity and reducedabsenteeism (Benedict and Arterburn, 2008; Black, 2008).

Historically, WHP has focused on physical health which ultimately relies onindividual behaviour change and biomedical measurements such as blood pressureand weight loss despite the greatest individual benefits being social and emotional.

139

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Contemporary OH&S approaches often include individual screening programmes thatare conducted on employees to determine these biometric measures such as bloodpressure, or behaviour patterns such as inactivity or excessive alcohol consumption(Worksafe Victoria, 2012). In this form it is up to the employees to seek to changetheir individual behaviour to improve their health. These type of WHP programmeshave been widely criticised for having a narrow individual employee focus withmany interventions directed solely at individual employee behaviour change withoutpaying attention to the contributing role of physical (e.g. facilities, buildings, furnitureetc.) and psychosocial workplace features (e.g. social support, social norms,management styles, organisational cultures) to employee health (Chu et al., 2000;Marshall, 2004; Black, 2008). These individual behaviour change programmeshave limited success (especially beyond the duration of the programme) when runas a “one off”, often attracting those already motivated to participate or change theirbehaviour (Marshall, 2004).

In recent years there has been a substantial broadening of the concept and scopeof workplace health from those programmes focusing on screening and individualapproaches, to considering the workplace as a whole setting with multiple influencesand opportunities (Hooper and Bull, 2009). A comprehensive review of workplacehealth and physical activity (WPHA) programmes in Australia undertaken byAckland et al. (2005) found that WPHA programmes have the potential to increasehealth awareness and motivation to change health behaviours but more importantlythey also noted that “the important benefits were primarily personal and social, ratherthan organisational” (p. 7). Although WHP is becoming more popular with manyprogrammes implemented in workplaces in Australia and elsewhere, the researchevidence base is still strongly focused on reporting results often related to individualbehaviour change (Hooper and Bull, 2009).

Workplace stress is another important aspect that requires consideration whenexamining WHP. Chronic exposure to stressful situations at work coupled withpoor management support has been linked to a range of health conditions includingdepression, anxiety and cardiovascular disease. Stressful working conditions can alsoimpact on employee health and well-being by limiting an individual’s ability to makepositive lifestyle changes (e.g. smoking or alcohol overuse). WHP programmes thatfocus almost exclusively on individual lifestyle changes such as diet, exercise andsmoking with little or no consideration of the contribution that the workplace itself(both the physical space and the organisational culture) can make to such behavioursare of limited benefit. WHP programmes directed at assisting people to cope withstressful working conditions without addressing the actual working conditionsthemselves contravene the OH&S legislation that exists in many industrialisedcountries including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK and the US (Chu and Dwyer,2002; Noblet and LaMontagne, 2006).

Despite a plethora of international studies documenting many of the successes ofWHP programmes and many Australian reports commissioned by governmentdepartments, quality evidence of what works in individual organisations is lacking(see, e.g. Bellew, 2008; Comcare, 2010; Hooper and Bull, 2009; The Health andProductivity Institute of Australia, 2010) Even with a growing interest in theimportance of WHP programmes in addressing employee’s health and wellbeingthere is still limited evidence that explores the success factors of WHP programmes inthe Australian context focusing on the perspectives of employers and employees. TheVictorian State government, through the Department of Health acknowledged this by

140

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

providing funds for research to investigate current WHP programmes and strategieswith a view to informing future policy directions.

The aim of this study was to inform policy on best practice principles and providereal life examples of health promotion in regional Victorian workplaces.

The objectives

To explore employers’ understanding of work place health.To explore employees’ understanding of work place health.To identify benefits and barriers to workplace health programmes.

This study did not attempt to define “WHP” or “health”. The participants in this studywere free to interpret health and wellbeing any way they chose. This enabledthe inclusion of data about factors which impacted on health and wellbeing that maynot have fallen under the banner of a defined WHP programme. This study did notdefine the “benefits” of WHP. Many studies have limited their measurement of benefitsto individual biomedical or behaviour indicators such as reduced blood pressure,weight loss or smoking cessation. In line with the broad scope of this study the benefitsto an individual or an organisation were not limited in this way by the researchers.

MethodA case study approach using mixed methodology was used to document andinvestigate the WHP programmes in three Victorian workplaces (Stake, 2008; Grbich,2012). The case study approach allowed for an examination of the unique factorsimpacting on WPH for each of the participating organisations. Each organisationhad an established WHP programme in place. The data collection methods includedindividual interviews with employers and employees which were then followed up by asurvey. For the purposes of this paper, we have focused on the qualitative componentpresenting the results from thematic analysis of the interview transcripts (Ezzy, 2002).The rationale for this is that it provides a unique insight into the perspectives of theemployers and employees regarding their understandings of WHP and the barriersand benefits of such programmes within their organisations.

Profile of the participating organisationsEach of the three participating organisations is located in regional Victoria. They wereselected for inclusion into the study based upon their established WHP programmesand commitment to employee wellbeing.

The largest of the three organisations is a national public company and a majoremployer in Victoria. Its head office is based in regional Victoria with approximately900 white collar employees. Only employees who worked at this site were eligible forthis study. A key feature of this organisation is the recently completed purpose builthead office which has a focus on employee health and comfort and a commitment to theenvironment through a five star energy rating.

The second organisation is a local government authority. This organisationemploys approximately 193 full time and part time employees across a range ofsectors including administration, manual outdoor, service delivery and early childhoodeducation. The employees are spread across a large geographic area of approximately6,500 square kilometres, with many having no regular contact with colleagues in differentsectors or localities. Worker health checks (screening for risk factors such as high bloodpressure, overweight and fruit and vegetable intake) and health information sessions are

141

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

regularly provided by a visiting community health service. At the time of this study, astaff survey had recently been completed by the organisation to ascertain the needs ofstaff in future planning of their health and wellbeing programme.

The third organisation is an owner operated manufacturing company with eightnational sites. The regionally located head office was the workplace of all theemployees who participated in this study. At the time of the study, the companyemployed approximately 80 people at this site. Employees were engaged in manualduties with a small number employed in administration roles. A long standingrelationship with the local community health service has allowed the company toincorporate a range of health information sessions and worker health checks intobusiness activities. The cornerstone of the health programme is their on-site counsellorwho has been employed two days a week for the last three years. Her services areavailable to all staff and their family members, paid for by the company.

Data collection and analysisSemi-structured interviews were conducted with management and employees fromeach organisation to understand perspectives and issues in the development andimplementation of workplace health programmes (Grbich, 2007, 2012). The interviewstook place at the workplace within normal working hours and were typically between30 minutes to one hour in duration. With the permission of each participant, theinterview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were followed bya survey measuring participation in workplace health programmes, and aspects ofthe programmes including acceptance, understanding and potential benefits ona workplace level. The results from the survey are reported elsewhere.

The qualitative interview data was transcribed, coded and thematically analysedwith individuals’ quotes used to highlight the main findings. The quotes appear initalics in the results section below. All data were coded and analysed by one researcherwho had conducted each of the interviews to ensure consistency and rigour(Green et al., 2007). For conciseness and confidentiality the data from each organisationwill be combined and not presented as individual cases.

RecruitmentParticipation was open to all management and employees of each of the organisations.Promotion of the study was tailored to each organisation. Strategies includedonline and physical noticeboards, staff meetings and researcher attendance tointroduce the study. Recruitment was by participant sign up and was facilitated byeach organisation. Word of mouth peer recommendations encouraged more employeesto participate in interviews.

ParticipantsIn total, 42 interviews were conducted across the three organisations. This numberincluded at least one member of senior management at each workplace including thethree CEOs. In total, 19 of the interviewees were female, 23 were male.

ResultsTo protect the identity of the organisations and the confidentiality of participantsthe results are presented as a compilation of the interview data from the threeorganisations. For the purposes of this study, “employers” also included key seniormanagement personnel.

142

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

A definition of workplace health: employersDifferences between employers’ and employees’ understanding of workplace healthwere apparent. For employers a strong focus on OH&S was evident, with employersciting policies and procedures to maintain personal safety and avoid injury. Employersalso focused on productivity, with health (physical and mental wellbeing) a necessaryprerequisite for being “able to cope” with the demands of the job to meet expectedstandards. Activities such as training, supervision, counselling, managementsupport and OH&S measures was understood (if not eloquently described) to beworkplace health. Activities believed to improve the physical capabilities and/orpsycho-emotional capacity to cope with the requirements of a position were included indefinitions of workplace health. Despite each organisation having a self-declaredcommitment to employee health and wellbeing, including the existence of strategicplans, the employers interviewed typically struggled to define or describe workplacehealth/WHP:

Yep look I think it’s very important that people do have that health and wellbeing so that theycan cope with what gets put before them because [y] we have an obligation I think to ourpeople that they can perform the roles that they are given and that they are given the training[y] and the support to make sure that they can cope. So it’s really about making sure thatthey have got the capacity to do what they are being asked to do.

Some employers felt workplace health was more than “a capacity to do what isbeing asked”. Others suggested workplace health included providing the conditionsfor personal development and allowing individuals to become the best they can bethrough opportunities provided to them within the workplace. This view was basedon a humanistic belief that employees were entitled to have opportunities forself-improvement at work. It was these employers that focused more on healthpromotion rather than primarily illness or injury prevention:

Well we think that workplace health the opportunity to offer a focus on health and healthprograms to the people who work here that it is not just to benefit their work but [also tobenefit] their lives [y] In general we have an attitude to learning and development andhealth is just part of it. Simply it has got nothing to do with anybody working better. We justlike to provide opportunity for people so that they improve their life and that is what actuallyhappens with the Workplace Health Program in that it spills over into their private life-theripple effect is enormous.

A definition of workplace health: employeesEmployees also acknowledged the role of OH&S measures in workplace health,however, the main focus of their responses focused on mental health, emotionalwellbeing and happiness. Employees reported that good emotional health comes fromworking in a respectful workplace, whereas poor emotional health can be caused by ormade worse by an unhealthy working environment. Typically employees reported thatthey could take care of their physical health outside of work, but what really matteredat work was their mental and emotional wellbeing:

It’s fantastic to have the health programs. You really feel that they put you first as a personand your health first because if you are healthy you are going to be a better worker.

I am appreciated for what I do, that is really, really important and that’s probably one of thebiggest factors in as far as workplace health is that if you don’t feel appreciated you are notgoing to be healthy in your job and I do feel like I am appreciated.

143

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

What makes a health promoting workplace?Respondents (which will hereafter refer to both employers and employees) identifiedmany health promoting features within their organisation as having a positive impactupon their health. These can be grouped into three aspects:

(1) The organisational culture of a workplace: this includes management andhierarchy structure, management/ staff communication, friendly staffinteractions, flexible work options such as part time, work from home, ortime in lieu and how easy it is to use these options. It is also about the “feeling”within an organisation – all those little things that make an employee say “thisis a great place to work”. It’s not about the perks offered to employees – it’sabout how the organisation operates its day to day business. If this is ina way that respects employees, their needs, their family commitments, andtheir ideas, then it is likely that organisation has a “good culture”. This aspectwill be expanded upon later in the paper.

(2) WHP programmes: these are add-on programmes often about a specific healthtopic that are run at work in or outside normal working hours. They take manyforms which often include some aspect of individual behaviour change as theintended outcome:

. Health information session topics include men’s health, women’s health,quit smoking, diabetes education, healthy cooking, sleep and relaxation.

. Fitness programmes can include workplace team or individual fitnesschallenges run for a specified amount of time, healthy eating programmesdesigned to increase fruit and vegetable intake and reduce unhealthy foodintake, walking groups or provision of pedometers to staff, subsidised gymmemberships and/or lunchtime yoga.

. Medical screening includes hearing tests, blood pressure/weight/cholesterol/heart/skin checks and influenza vaccinations. These are alsoknown as Worker Health Checks.

. Training can include training in leadership, communication, personality styles,bullying prevention, first aid, ergonomics, manual handling and heavy lifting.

(3) Amenities: these are somewhere between organisational culture and healthpromotion programmes. These amenities often reflect the culture of anorganisation and its level of commitment to the health of employees andthe importance of a healthy and happy workforce for organisational harmonyand good productivity.

These amenities can include physical aspects of the organisation’s property such asa large staff room with outdoor seating, a childcare centre, a homework room foremployee’s children, comfortable chairs and opening windows. It can also includesmaller items such as tea/coffee and newspapers in the staff room, fresh fruit, andemployer supplied breakfasts, morning tea or lunches for special occasions.

Benefits of WHPThere are benefits to the organisation and the individual worker. Employees andemployers reported that the organisations benefited from an increase in productivity,staff retention, staff morale and loyalty, a reduction in absenteeism and the

144

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

organisations gain a reputation as a great place to work. The quote below typifiesthe responses from employers:

What do we get for [having a health and wellbeing program]? We get a more productive workforce. More importantly we get a reputation as a really good place to work that really caresabout their staff and so people want to work here. So we get to cherry pick the best out of theemployment pool.

Employees report improvements in happiness, confidence, job satisfaction, physicalhealth, work ethic, healthy behaviours such as increasing fruit and vegetableconsumption and decreasing alcohol intake, and a gain in enthusiasm for healthychoices which is often shared with family members resulting in healthy meal optionsfor example. When employers make an effort to do something for the good of theemployees, such as offer flexible time, run a health information session or have a staffBBQ at lunchtime, employees feel willing to repay this through extra hard work.Employees often reported a perception of being cared for by employers through theprogrammes on offer as highlighted in the excerpts below:

I think that it is really good [that my boss cares for me through providing programs] and I thinkthat it probably shows in the stuff that we make because we want to actually do a good job.

It’s good, it’s a good place to work, it is [like] a family environment [y] you feel like you arepart of something.

Employees like programmes that:

. are free;

. are confidential;

. are easy to participate in;

. are enjoyable;

. make them feel valued;

. offer opportunities for socialising;

. increase health and wellbeing knowledge;

. increase motivation;

. develop personal skills; and

. are available in work time.

Barriers to WHPOrganisations may be reluctant to undertake WHP with employers reporting thatworker safety is their responsibility but worker health is not. Barriers exist foremployees to engage with health promotion programmes. This is often due to time.Outside of working hours many employees have other commitments and prioritiesand will not return to work for an evening programme. Inside of working hours,employees are reluctant to give up their lunch break for a programme. They mayalso resist participating in a programme if their work piles up when they are away orthey will suffer disapproval from their managers or co-workers for their absence:

One bloke there had to go to the Quit course and his boss said “You can’t go to that you havegot something else that you have got to do” – so he didn’t go.

145

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Employees did not like programmes that:

. lack choice;

. lack staff engagement;

. lack management support;

. are poorly timed;

. focus on just information provision;

. are not targeted to specific issues;

. are not targeted to specific audiences;

. are repetitive; and

. are based on a “one size fits all” model.

Organisational culture and its influence on healthThe following organisational aspects emerged as important factors which impacted onthe health promoting environment within the organisations. These factors repeatedlyarose when participants were discussing mental and emotional wellbeing which wasreported as being more important at work than physical health.

Management supportCommitment by all levels of management to a respectful culture and to WHPprogrammes was a motivating factor for employees to participate in the programmesand model the respectful characteristics. Where management support was lackingor different levels of management displayed differing commitment to WHP, theemployees felt less motivated to participate in WHP programmes:

[The manager] is always trying to get people to do [the health promotion programs],to get involved with it because she wants everyone else to stay healthy at work and shedoesn’t mind if it takes a bit of our work day out just to make sure that we are healthy.

An employee of the largest of the organisations whose job it was to promote healthand wellbeing in the workplace revealed that gaining top level executive supportfor health promotion initiatives was sometimes hard due to competing priorities. Ina post global financial crisis environment there could be resistance to items notconsidered to be “core business” or a lack of time for the executive members to focus onWHP which may not be considered important in the bigger scheme of things. Businessdownturn is one possible reason for core business to be prioritised, however rapidbusiness growth was another reason given for lack of management support for WHPprogrammes. Management was considered too busy to either notice or care aboutsmall WHP initiatives:

We provide tea, coffee and biscuits and I just think “biscuits you know it is not a fantasticidea”. I would rather be providing fruit or something like that so if I put up to them [theexecutive members] that we should be changing the biscuits to fruit they probably would bejust thinking “Nah this is not a priority at the moment”.

Workplace flexibilityOne of the most valued things for many employees was workplace flexibility with manyemployees referring to family friendly policies as being the best thing about their jobs.

146

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

They described their workplaces as being supportive, caring, valuing of employees,family friendly, flexible and assisting with a work/life balance. Such things as workingschool hours, access to flexi-time and the readiness of management to support thesetypes of arrangements were highly valued:

Well when I started I was coaching the junior soccer team so they let me go like fifteenminutes early to get there on time and like you know you put in the extra ten minutes at thestart of the day, so they are really flexible with things like that.

CommunicationWhen employees feel they have an approachable boss and communication betweenmanagement and employees is two-way, easy, frequent and respectful, employeesreport feeling valued, able to express their ideas with confidence, and well supported intheir day to day role. This was considered an especially significant aspect to theenjoyment of their jobs by a majority of employees:

Being able to actually talk to my manager about a lot of my personal stuff so that helps mymental health.

One manager stated that:

What we want to develop here is a place whereby not only are [staff] encouraged to have theirideas they are encouraged to be able to articulate those ideas and have the self-confidence toshare those ideas and then also be recognized for having them and being engaged andinvolved in the implementation of those ideas. We don’t want them to sit on their handsand be quiet and have great ideas and just let the time pass. We don’t want that. We wantmuch more than that and the workplace health program is a big part of that.

The smallest of the three organisations had a counsellor who worked two days a weekattending to employees and their families. She provided a valuable alternative avenuefor communicating about work and personal issues. An employee described whathaving the service of the counsellor meant to him:

It just shows how much they [the employers] care about their staff and making sure that theirminds are healthy and making sure that they are feeling better about themselves I suppose.

Personal relationshipsEmployees like to feel valued and to know that their boss actually cares about them asa person. Attributes like respect, trust, caring, being approachable and the ability todevelop personal relationships with different levels of management was important formany employees:

The people in management often ask how you go. The family that runs the business knowabout me and they ask about [my wife], they remember my wife’s name, my oldest son theyhave met a few times they remember his name and ask about him.

RewardsRewards were reported across the three organisations. Rewards included financialbonus payments, movie tickets, employee of the month/year awards and staff parties.It was not the size of the reward that was important, but rather the intention and themanner with which the reward was given. Rewards had more meaning to employeesand increased the employee’s sense of self-worth more when they were personalised(not given to everyone), unexpected (not a part of a regular bonus system), directly

147

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

linked to an event or period of time (e.g. as a thank you for hard work over the busyChristmas period) and personally given by management to the employee (the valuewas reportedly lessened when supervisors rather than the most senior manager gavethe reward). Peer nominated rewards were also valued highly:

My area had a lot of problems at that stage. We had a few people cause us a few problems andthey quit and after they left the area picked itself up and kept going and management noticedthat we were doing really well. So they gave us all movie tickets.

[It was] something small but it actually means something if it comes from management. It isgood to know that management knows that we are working hard.

Physical spacesEmployees often referred to the physical environments in which they worked mostlyciting factors relating to their immediate work stations (ergonomics and comfort). Forsome the physical space was one of the best things about their work environment withclean, bright open spaces as being important. The provision of car parking, bikeshelters and showers were also seen as positives. Each of the organisations had madesome provisions relating to family friendly environments including such things asseparate rooms for employees’ children to do homework, to attend work with a parent,and for breastfeeding employees to feed their infants. The manufacturing organisationhad implemented a system of ordering, storing and streamlining the raw materials attheir factory site acknowledging the mental health benefits of working in an organisedenvironment:

It feels rewarding to be here in a building like this.

It is great to have a family friendly environment where I don’t feel at all any pressure if I bringkids into work or anything like that, there is no stresses. We are very lucky from that pointthey have an area here where you can breast feed [y] and that is fantastic.

The common benefit resulting from the organisational aspects detailed abovewas the feeling of being valued. Feeling valued was described during the interviewsas associated with good mental and emotional health. Previous studies have notrevealed this as a factor of WHP potentially because many of them focus onquantitative outcome measures only. All of the organisational aspects are interrelatedand each can contribute to increasing an employee’s sense of feeling valued. Forexample the physical environment can facilitate communication and peer interactionby having a large staff room dining table; the provision of newspapers at the tableleads to shared discussions and finding things in common with co-workers;the resulting relationships provide good social support both inside and outside of theworkplace.

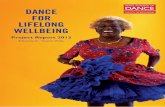

Figure 1 depicts the components of a health promoting workplace as reported bythe participants in this study. A strong emphasis on mental and emotional health isevident through the prioritising of interpersonal relations (personal relationships,communication and management support). Physical health programmes are notpresent in the figure as in and of themselves they will not create a health promotingworkplace. The components in the figure are essential foundations for improvinghealth in the workplace. Once the components are in place in an organisation,additional programmes to improve physical health may be implemented and are morelikely to achieve their aims.

148

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Discussion: what makes for successful WHP?The breadth of participant’s responses demonstrates how extensive WHP can be.Emotional and mental wellbeing which employees reported as being stronglyinfluenced by their workplace has not to date attracted the same interest or funding asphysical health improvement campaigns such as the Victorian state governmentfunded work health checks. The improvement of mental and emotional health comesthrough the “culture” of a workplace supporting the psychosocial needs of employees(Noblet and LaMontagne, 2006). This culture is embedded into the organisationalstructure of a workplace and is not a discrete health promotion programme. Simplestrategies can support this, such as encouraging managers and staff to praise theirco-workers for a job well done which will assist to build a culture within theorganisation that does not take these small things for granted. Employees in our studyreported that something as simple as receiving a birthday card or movie tickets inrecognition of extra effort can make a difference. Employees need to feel valued in theirrole. This has very little to do with the role’s status and everything to do with how anemployee is treated. Employees appreciate when management know the role andimportantly know how the employee is going. These findings were supported ina quantitative study by Arnold and Dupre (2010, pp. 146-147) who found that“employees clearly react emotionally to their perceptions of being valued andsupported by their organisation and this in turn impacts their physical health”. Theprovision of a counselling service was highly regarded by participants at oneworkplace explaining how this service enabled them to manage some personal issuesthat were affecting them at work. The value of workplace counselling has beenrecognised internationally as an effective means of assisting employees to cope with a

physical environment

management support for WHP

two-way communication

flexible work

rewards

personal relationships

Figure 1.A health promoting

workplace

149

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

range of psychological, emotional and behavioural problems that may impact onthem at work (Kirk and Brown, 2003; McLeod, 2010).

The organisational culture of the workplace plays a significant role in the uptakeof WHP programmes (Makrides et al., 2007; Goetzel and Ozminkowski, 2008). Goodorganisational characteristics are the platform from which workplace healthprogrammes may be launched. Without factors such as good management support,good communication and job flexibility, any programmes are likely to suffer froma lack of interested participants and/or a lack of desired outcomes. The above factorsundoubtedly improve mental health which is the first step to improving peerrelationships, physical health, family relationships, engagement with the widercommunity and worker productivity (Russell, 2009).

All employers in our study (even those who provided the most generous amenitiesto their staff for the benefit of the employees’ health and wellbeing) maintainedan understandable priority for productivity and their financial bottom line. This is notat odds with successful WHP. Changes to an organisation which can improve healthdo not need to be expensive, and as these results show, the organisation’s productivityand bottom line benefits through decreased absenteeism and increased staff moraleand work ethic. A report commissioned by the large Australian medical insurerMedibank Private confirmed these results, finding that the healthiest Australianworkers are three times more productive than the unhealthiest workers (MedibankPrivate, 2005). Employees are happy to work hard in a role where they feel respectedand valued. Employers can improve employee health and wellbeing by implementingor improving:

. Leadership – lead by using good examples and use leaders as mentors andchampions of workplace values and virtues (Russell, 2009).

. Build health and wellbeing into the core daily business – take every opportunityto improve respect and communication among staff as a part of day to day work(Ackland et al., 2005).

. Align health promotion initiatives with the organisation’s values – if theorganisation values passion, make the programme fun; if it values teamwork,make the programme feature a team competition (Black, 2008).

. Design a strategic plan for health promotion and review it annually and allocatea budget to support the initiatives in the strategic plan (Ackland et al., 2005).

. All employees must get equal opportunities to be involved – don’t excludedistantly located employees (Ackland et al., 2005).

. Tap into existing public events – national or local community health awarenesscampaigns. This encourages participation, is fun, and strengthens links with thecommunity (Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH), 2011).

This whole of organisation approach in which health promotion is embedded into theday to day running of the business is a significant shift from the individual behaviourchange approach currently dominating WHP. Providing a supportive environmentand improving the organisational culture within a workplace are essential first stepsto ensuring the success of WHP programmes. The goals of the programmes should beto ensure that positive health behaviours become engrained into the culture of anorganisation. For many organisations this requires “a shift in thinking, so that theinterventions are not seen as short-term programmes, but as part of the culture of the

150

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

workplace” (Marshall, 2004, p. 64). In order for this to be achieved it is vital to havefull management support and commitment to the goals of the programme ( Junget al., 2011). The European Network for WHP has developed a “healthy organisationmodel” which depicts the factors crucial for the success of WHP (Institute ofOccupational Health and Safety (IOSH), 2010). This embedded approach reducessome of the barriers to participation (lack of time or lack of management support forprogrammes) reported in this study. Each of the organisations in this study hadundergone changes due to mergers and/or the global financial crisis. This left manyemployees acutely aware of the tenuousness of their positions (having seen colleaguesretrenched) or upset about staff bonus payments being suspended when they wererequired to do more work with less staff. It is precisely when employees are feeling thisvulnerable that they most need the reassurance of feeling valued in their role. This canbe achieved reasonably cheaply, and have the potential to swing staff morale fromdisillusioned and resentful to encouraged and motivated to work hard for the company.Simple ideas such as movie tickets as a reward for employee of the week, or a familypicnic day can produce feelings of being valued.

What policy makers can do?Policy makers must broaden the scope and definition to effectively support the wholeof organisation approach identified in this study. The narrow biomedical individualbehaviour change view is of limited effectiveness in terms of population health as itdoes not address the social determinants of health (Ravia and Thomson, 2011).However, the current work health checks campaign in Victoria (which falls into thebiomedical behaviour change category) has created an awareness of workplace healthand a momentum which it would be prudent to build upon. Mental health is alreadyacknowledged in Australia and around the world as a significant public health issue(Department of Health and Ageing, 2008; World Health Organization, 2008).

The role of the workplace in supporting good mental health must be prioritised.Already Australia has moved to heighten the awareness of bullying and harassmentin the workplace and has bought to account those who transgress through the legalsystem, (a toughening of the laws now sees workplace bullying come under the CrimesAct 1958 rather than the less severe penalties in the Occupational Health and SafetyAct 2004 (Department of Justice, 2012). This system however, is a deficit modeloperating on the “what not to do” end of the scale rather than supporting “what to do”initiatives. As Butterworth and colleagues concluded:

From a policy perspective it is important to recognise that, just as adverse psychosocial jobconditions may lead to poor mental health, it is possible that workplace changes whichimprove the quality of one’s job could be an effective strategy to improve population mentalhealth (Butterworth et al., 2011, p. 570).

Policy makers can support initiatives by employers through the provision of grants toimplement business coaching, leadership training, and health coaching. The formertwo initiatives are more readily associated with business psychology but this is thepoint – that “health” programmes, to be truly effective, must expand their focus andassociated funding beyond what has traditionally been defined as health. While thisposes challenges to government departments who often operate in isolation from oneanother, there is a real need for inter-sectoral collaboration and understanding. Anappreciation is needed by policy makers and funders that organisational change takestime and that neither tangible initiatives (specific time limited, distinct “programmes”)

151

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

nor measurable (biomedical/physical) health outcomes may be present in the way theyhave been traditionally expected and quantified.

Limitations of this studyThis study was conducted in three workplaces in regional Victoria in Australia.The study was not designed to yield a representative sample of all workplacesor all workers. The researchers acknowledge that there exists a wide variety ofworkplaces and working situations not captured in this sample. The sample size of42 interviews is quite large for a qualitative study and the results provide someunique insights into WHP programmes and how these are viewed by employersand employees.

Conclusion and recommendationsWHP is the domain of all employers and everyone who works. Good population health,especially mental and emotional wellbeing, depends upon health promoting workingenvironments. This study has revealed that health promotion in the workplace is notonly about providing health programmes such as a fitness challenge designed to bringabout individual behaviour change, but rather it is the supportive organisationalculture of a workplace that provides the most benefits to individual workers. Topositively influence health in the workplace a shift in focus is required from individualor personal behaviour change to a more strategic, comprehensive approach. Thisincludes a range of multi-strategy interventions but the most important component ismanagement support and integration of WHP into the organisational structure.In the cases reported here it was clearly evident that when WHP is embedded into theculture of a workplace and supported by management on all levels that real healthgains are possible.

Further benefits to the organisations through improved productivity and reducedabsenteeism make the case for implementing change a sound one for employers.Employers will need guidance and support to make positive changes, especially as manyemployers may currently see worker health and wellbeing as not their responsibilitybeyond legislative OH&S requirements. It is recommended that workplaces are supportedby policy and government initiatives that enable clear pathways for employers to makeorganisational adjustments to enhance the health and well-being of staff and be rewardedfor doing so. Workplaces are uniquely placed to have a positive impact on health and well-being but need to be supported to make changes to such things as organisationalstructures that impact negatively on the employers and employees. Whilst this study hasprovided some unique insights into how employers and employees view WHP withinthe context of their organisations, further research that documents the many successes inWHP is warranted.

References

Ackland, T., Braham, R., Bussau, V., Smith, K., Grove, R. and Dawson, B. (2005), “Workplacehealth and physical activity review report”, available at: www.dsr.wa.gov.au/assets/files/Healthy_Active%20Workplaces/review%20of%20workplace%20health%20program.pdf(accessed 7 October 2012).

Arnold, K. and Dupre, K. (2010), “Perceived organizational support, employee heath andemotions”, International Journal of Workplace Health Management, Vol. 5 No. 2,pp. 139-152.

152

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2010), “Australia’s health 2010”, available at: http://aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id¼6442468376 (accessed 4 April 2012).

Bellew, B. (2008), “Primary prevention of chronic disease in Australia through interventionsin the workplace setting: an evidence check and rapid review”, available at: http://docs.health.vic.gov.au/docs/doc/977A6788FBDAF83ECA2578CC001AA886/$FILE/workplace-setting-rapid-review.pdf (accessed 4 April 2012).

Benedict, M.A. and Arterburn, D. (2008), “Worksite-based weight loss programs: a systematicreview of recent literature”, American Journal of Health Promotion, Vol. 22 No. 6,pp. 408-416.

Black, C. (2008), “Working for a healthier tomorrow: review of the health of Britain’s working-agepopulation”, available at: www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/hwwb-working-for-a-healthier-tomorrow.pdf (accessed 11 November 2012).

Buck Consultants (2008), “Working well: a global survey of health promotion and workplacewellness strategies”, available at: www.worldcongress.com/events/HR09015/pdf/thoughtleadership/Global%20Wellness%202008%20Survey%20Report.pdf (accessed21 March 2011).

Bull, F., Adams, E., Hooper, P. and Jones, C. (2008), Well@Work: Promoting Active and HealthyWorkplaces Final Evaluation Report, School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, LoughboroughUniversity, Loughborough.

Butterworth, P., Leach, L.S., Rodgers, B., Broom, D.H., Olesen, S.C. and Strazdins, L. (2011),“Psychosocial job adversity and health in australia: analysis of data from the HILDAsurvey”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, Vol. 35 No. 6, pp. 564-571.

Chu, C. and Dwyer, S. (2002), “Employer role in intergrative workplace health management:a new model in progress”, Disease Management and Health Outcomes, Vol. 10 No. 3,pp. 175-186.

Chu, C., Bruecker, G., Harris, N., Stitzel, A., Gan, X., Gu, X. et al. (2000), “Health-promotingworkplaces: international settings development”, Health Promotion International, Vol. 15No. 2, pp. 155-167.

Comcare (2010), “Effective health and wellbeing programs”, available at: www.comcare.gov.au/Forms_and_Publications/published_information/our_services/safety_and_prevention/safety_and_prevention/effec_health_wellbeing_prog (accessed 14 April 2012).

Department of Health and Ageing (2008), “National mental health policy 2009”, available at:www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/532CBE92A8323E03CA25756E001203BF/$File/finpol08.pdf (accessed 12 November 2012).

Department of Justice (2012), “Bullying law in Victoria-‘Brodie’s law’ ”, available at: www.justice.vic.gov.au/victimsofcrime/utility/newsþandþevents/newþbullyingþlawþ-þbrodiesþlaw(accessed 8 August 2012).

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2010), “Workplace health promotion foremployees”, factsheet 94, Belgium European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

European Network of Workplace Health Promotion (2005), “Luxembourg declaration ofworkplace health promotion-updated”, available at: www.enwhp.org/workplace-health-promotion.html (accessed 12 March 2011).

Ezzy, D. (2002), Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation, Crows Nest, Allen &Unwin, NSW.

Goetzel, R. and Ozminkowski, R. (2008), “The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs”, Annual Review of Public Health, Vol. 29, April, pp. 303-323.

Grbich, C. (2007), Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction, Sage, London.

Grbich, C. (2012), Qualitative Data Analysis, 2nd ed., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

153

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Green, J., Willis, K., Hughes, E., Small, R., Welch, N., Gibbs, L. et al. (2007), “Generating bestevidence from qualitative research: the role of data analysis”, Australian and New ZealandJournal of Public Health, Vol. 31 No. 6, pp. 545-550.

Harden, A., Peersman, G., Oliver, S., Mauthner, M. and Oakley, A. (1999), “A systematic review ofthe effectiveness of health promotion interventions in the workplace”, OccupationalMedicine, Vol. 49 No. 8, pp. 540-548.

Health Work and Wellbeing UK (2008), “Improving health and work: changing lives”, TheGovernment’s Response to Dame Carol Black’s Review of the Health of Britain’s Working-age Population, available at: www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/hwwb-improving-health-and-work-changing-lives.pdf (accessed 16 November 2010).

Hooper, P. and Bull, F. (2009), “Healthy active workplaces: review of evidence and rationale forworkplace health”, available at: www.dsr.wa.gov.au/assets/files/Healthy_Active%20Workplaces/Convincer%20Document%20-%20Review%20of%20Evidence%20of%20Workplace%20Health%20Programs.pdf (accessed 11 November 2012).

Hymel, P.A., Loeppke, R.R., Baase, C.M., Burton, W.N., Hartenbaum, N.P. and Hudson, T.W. et al.(2011), “Workplace health protection and promotion: a new pathway for a healthier-andsafer-workforce”, Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, Vol. 53 No. 6,pp. 675-702.

Institute of Occupational Health and Safety (IOSH) (2010), “Working well: guidance onpromoting health and wellbeing at work”, available at: www.enwhp.org/toolbox/pdf/1008111447_Working_well%255B2%255D.pdf (accessed 3 November 2012).

Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) (2011), “Working well. Guidance onpromoting health and wellbeing at work”, available at: www.iosh.co.uk/books_and_resources.aspx (accessed 3 November 2012).

Jung, J.M.N., Dipl Soz, A., Ernstmann, N., Driller, E., Wasem, J., Stieler-Lorenz, B. and Pfaff, H.(2011), “The relationship between perceived social capital and the health promotionwillingness of companies: a systematic telephone survey with chief executive officers inthe information and communication technology sector”, Journal of Occupational &Environmental Medicine, Vol. 53 No. 3, pp. 31-323.

Kirk, A. and Brown, D. (2003), “Employee assistance programs: a review of the mangement ofstress and wellbeing through workplace counselling and consulting”, AustralianPsychologist, Vol. 38 No. 2, pp. 138-143.

McLeod, J. (2010), “The effectiveness of workplace counselling: a systematic review”, Counsellingand Psychotherapy Research, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 238-248.

Makrides, L., Heath, S., Farquharson, J. and Veinot, P. (2007), “Perceptions of workplace health:buiding community partnerships”, Clinical Governance: An International Journal, Vol. 123,pp. 178-187.

Marshall, A.L. (2004), “Challenges and opportunities for promoting physical activity in theworkplace”, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 60-66.

Medibank Private (2005), “The health of Australia’s workforce”, available at: www.trenchhealth.com.au/articles/MEDI_Workplace_Web_Sp.pdf (accessed 15 November2012).

Noblet, A. and LaMontagne, A.D. (2006), “The role of workplace health promotion in addressingjob stress”, Health Promotion International, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 346-353.

Ravia, J. and Thomson, C.A. (2011), “A systematic review of behavioral interventions to promoteintake of fruit and vegetables”, Journal of The American Dietetic Association, Vol. 111No. 10, pp. 1523-1535.

Russell, N. (2009), “Workplace wellness: a literature review for NZWell@Work”, available at:www.nzwellatwork.co.nz/pdf/wrkplc-wellness-lit-rev-feb09.pdf (accessed 14 October 2012).

154

IJWHM7,3

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)

Stake, R.E. (2008), “Qualitative case studies”, in Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds), Strategies ofQualitative Inquiry, 3rd ed., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

The Health and Productivity Institute of Australia (2010), “Best-practice guidelines: workplacehealth in Australia”, available at: www.hapia.org.au (accessed 29 March 2012).

Worksafe Victoria (2012), “Work health checks”, available at: www.workhealth.vic.gov.au/workhealth-checks/what-are-they (accessed 13 August 2012).

World Health Organization (1986), “The Ottawa charter for health promotion”, available at:www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/Ottawa-charter_hp.pdf (accessed 12 April 2012).

World Health Organization (2007), “Global plan of action on worker’s health”, available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB120/B120_28Rev1-en.pdf (accessed 12 April 2012).

World Health Organization (2008), “Preventing noncommunicable diseases in the workplacethrough diet and physical activity.

World Health Organization (2010), “Healthy workplaces: a model for action for employers”,workers, policymakers and practitioners, avaialble at: www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/healthy_workplaces_model.pdf (accessed 12 April 2012).

About the authors

Dr Virginia Dickson-Swift is a Senior Lecturer and the Head of Department in the Department ofPublic & Community Health at the LRHS, Bendigo. Virginia has an interest in health promotionand public health with a particular focus on the role of workplaces. She teaches across a broadrange of undergraduate and graduate public health programmes and has expertise in a range ofqualitative methodologies for health research. Dr Virginia Dickson-Swift is the correspondingauthor and can be contacted at: [email protected]

Dr Christopher Fox is a Senior Lecturer in Sexual Health Counselling and Therapy.Christopher previously was a Senior Lecturer in Public Health at the La Trobe Rural HealthSchool.

Karen Marshall is a Researcher and Casual Academic at the La Trobe Rural Health School.Karen has an honours Degree in Public Health from the La Trobe University and a specialinterest in public health policy. Her research topics have included the HPV vaccine andworkplace health promotion.

Dr Nicky Welch is a Sociologist with a background in public health. She is presently a seniorpolicy officer at the Victorian State Government Department of Health. Her research interestsinclude rural health, qualitative methodology, healthy eating and physical activity, workplacehealth promotion, and community health promotion.

Dr Jon Willis is an Associate Professor in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander StudiesUnit at the University of Queensland. He has a PhD from the Australian Centre for theInternational and Tropical Health and Nutrition, focused on Pitjantjatjara men’s practices ofmasculinity and sexual risk. Since the completion of his PhD, he worked as a Lecturer inIndigenous Health at the University of Queensland (1997-1999), as a Research Fellow and aSenior Research Fellow at the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society since July1999, and as a Senior Lecturer in Public Health at La Trobe University Bendigo from 2007-2012.

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: [email protected] visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

155

What reallyimproves

employee healthand wellbeing

Dow

nloa

ded

by D

octo

r C

hris

toph

er F

ox A

t 16:

13 1

6 Se

ptem

ber

2014

(PT

)