Was Byzantium a major commercial force in the tenth-century eastern Mediterranean?

Transcript of Was Byzantium a major commercial force in the tenth-century eastern Mediterranean?

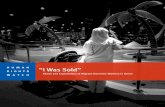

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Was Byzantium a major commercial force in the tenth-century eastern Mediterranean?

Andrew M. Small

20th November 2012

1

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

If general studies of tenth and eleventh century

Byzantium have been influenced by the ‘Manzikert

Conundrum’, finding long-term structural factors

behind the 1071 collapse, then analysis of Byzantine

economic and commercial life has long been dominated

by the ‘1204 question’. Why did the Venetians and

other Italian merchants become so dominant prior to

the sack of Constantinople in 1204? First posed by

Niketas Choniates in his Annals the answer has always

reflected the contemporary concerns of the person

asking it. For Niketas Choniates the sloth of the

Constantinoplitan merchants was symptomatic of the

malaise of the entire Byzantine social and political

system in the late twelfth century.1 Oikonomides

argued that protectionism of Byzantine merchants in

the Book of the Eparch left them unable to compete with

the Venetians when the Komnenoi granted them

privileged access to Byzantine markets.2 Harvey in his

monograph on the Byzantine economy and its growth

preferred to sidestep the issue of commerce and trade

and when he did, it was to confirm the view of

1 Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium: annals of Niketas Choniates, trans.Harry I. Magoulias (Detroit, 1984), p. 2132 Nicolas Oikonomides, ‘The economic region of Constantinople: from directed economy to free economy and the role of the Italians’, in G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (eds.), Europa medieval e mondo Bizantino (Rome, 1997), pp. 221-238.

2

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Venetian competitive advantage.3 The ‘1204 question’

also has contemporary political meaning in Russia. In

2008 Father Tikhon Shevkunov, Putin’s alleged

confessor, presented a TV series called “The

Destruction of the Empire: a Byzantine lesson” in

which the West, represented by a cloaked figure in a

long-nosed Venetian mask, was gifted the commanding

heights of the economy by weak and trusting emperors.4

Shevkunov was responding to xenophobic and anti-

western sentiment in Russia in the lead-up to the 2008

Russo-Georgian War, but he is not alone in using

Byzantium as a mirror to explain the success of the

West. In Lopez’s influential Western ‘commercial

revolution’ thesis, Byzantium appears as the

unsuccessful Eastern Christian alternative to the

Latin Christian West. Lopez’s thesis posits that

Byzantium lacked the capital, legal infrastructure and

commercial mentality of the Venetians and other

Italian maritime cities. This is an unfair view and an

unsophisticated approach to evaluating Byzantium’s

commercial presence.5 It does not analyse tenth-

century Byzantium on its own terms; it is guilty of

hindsight bias in trying to discover an inherent flaw

and not taking into account Byzantium’s commercial

3 Alan Harvey, Economic expansion in the Byzantine empire, 900-1200 (Cambridge, 1989).4 The Economist, ‘A Byzantine Sermon: the drawing of inaccurate parallels with Constantinople’, 14th February 2008.5 Roberto Sabatino Lopez, The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1976).

3

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

strengths. Lopez and Harvey often reduce commerce to

the carry trade- ships taking goods and people from

port to port. This argument ignores the importance of

manufacturing and the ‘added value’ accruing to

Byzantium through processing raw materials into high-

value goods such as silk textiles. The Byzantine

Empire controlled Constantinople, a major eastern

Mediterranean entrepôt but it was not the only such

market controlled by the Byzantine Empire. Byzantium’s

commercial clout should be evaluated across a range of

criteria including the carry trade and how prominent

Byzantine merchants were outside the Empire’s

territories. In addition we should consider the

attractiveness of Byzantium to trading diasporas and

foreign merchants and the spread of Byzantine

manufactured goods and raw materials across the

Mediterranean world.

One of the components of Lopez’s ‘commercial

revolution’ theory is that Byzantine merchants were

hampered by an over-regulating and over-powerful state

involvement in the economy. Laiou, Oikonomides and

Kazhdan have taken this up.6 Laiou argued that the

Byzantine aristocracy did not invest in trade to the

same level as their Venetian counterparts and

regulation of interest rates and profit margins in 6 Angeliki E. Laiou, ‘Byzantium and the Commercial Revolution’, in G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (eds.), Europa medieval e mondo Bizantino (Rome, 1997), p. 251; Oikonomides, ‘The economic region of Constantinople’, pp. 221-238; Alexander Kazhdan, ‘State, feudal and private economy in Byzantium’, Dumbartion Oaks Papers 47 (1993), p. 100

4

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Constantinople hampered the development of Byzantine

merchants and their commercial practices.7 The

Byzantine state and society were not antagonistic to

commerce and trade, indeed in the tenth century

Byzantium had arguably a more enlightened view of

trade and a better-developed legal infrastructure than

the west. Byzantium had generally been far more open

to lending at interest than the west. The practice had

been banned by Basil I but was restored by Leo VI in

Novel 83 on the pragmatic grounds that lending at

interest had continued to take place.8 Leo VI re-

instated the legal limits of Justinianic interest

rates but from the Book of the Eparch it is clear that

there was a considerable black market for loans and

financial services “from itinerant vendors of cash’

who were suspected of having links to established and

regulated bankers presumably charging different rates

to than the state legislated ones.9

Byzantine law also provided merchants with a rich

corpus of contract law and a number of options to

invest. Laws regulating exchange were founded on Roman

ideas of free contractual negotiation between

competent parties.10 In Constantinople there were the

7 Laiou, ‘Byzantium and the Commercial Revolution’, p. 245.8 ‘Ordinances of Leo VI, c.895, from the Book of the Eparch’, trans. E.H. Freshfield from Roman Law in the Later Roman Empire: Byzantineguilds, professional and commercial (Cambridge, 1938), Note p. 13.9 Book of the Eparch, Ch. 3; clause 2.10 Olga Maridaki-Karatza, ‘Legal Aspects of the Financing of Trade’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), p. 1106.

5

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

twenty-four legal notaries and probably likely some

illegal ones too.11 The state provided for foreign

merchants in the xenodochia legal services for handling

contractual disputes.12 The tenth century also saw the

development of the chreokoinonia, a legal contract that

enabled a merchant to endow a factor with capital who

would then engage in trade with the profits of the

factor’s activities being shared, often unequally,

between the two parties. The chreokoinonia developed

from long traditions in Roman and Byzantine law.

Indeed the chreokoinonia is the most likely predecessor

for the commenda or collegentia contracts developed in

Venice in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.13

Byzantium through its classical and Christian

inheritance had received Aristotelian ideas on

interest and patristic writings on social and economic

justice predicated on notions of just value, just

price, just profit and autarky. Hagiographies and

practice in the tenth century demonstrate that the

Byzantines were not culturally antagonistic to

merchants’ profits. The grain supply of Constantinople

appears to have relied on a monetised and private

system of exchange and supply, probably in the case of

the great houses of the magnates who possessed their

11 Book of the Eparch, Ch. 1.12Marlia Mundell Mango, ‘The Commercial Map of Constantinople’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54 (2000), p. 204.13 Olga Maridaki-Karatza, ‘Legal Aspects of the Financing of Trade’, pp. 1117-1120; Abraham L. Udovitch, ‘At the origins of the Western Commenda: Islam, Israel, Byzantium?’, Speculum 37/2 (1962), pp. 201-202.

6

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

own estates. A treatise by Symeon the New Theologian

on Ephesians 5:16, written c. 1000-1009, argued that

creation was a public good not a negative for society.

This ideology can also be seen in Symeon

Metaphrastes’s version of the Life of St Spyridon of Trimithous

that argued that borrowing for trade and expectation

of profit was not an intrinsic evil but that borrowing

for personal consumption was. Byzantine culture was

not anti-commerce.14 Lending at interest to invest in

trade was not frowned upon as it was in the

contemporary West. With the financial and legal

instruments Byzantine merchants had available to them

in the tenth century, they had an advantage over its

contemporaries in the west Byzantine merchants were

well-suited for commercial expansion during the period

of general economic growth within the empire from the

ninth century.

Another reason why the ideals of autarky failed

in part due to the need for pre-modern Mediterranean

communities to exchange goods. Their needs were driven

by geography and climate which created numerous

regions that could either have agricultural surpluses

or suffer famine. Trade equalised these imbalances and

as Horden and Purcell have theorised this trade formed

a constant in pre-modern Mediterranean history.15 These

14 Angeliki E. Laiou, ‘Economic thought and ideology’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 1123-1144.15 Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell, The corrupting sea : a study of Mediterranean history (Oxford, 2000), pp. 53-88.

7

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

base trade links could be stimulated to provide

longer-range flows of foodstuffs and goods. The Late

Antique Byzantine economy with the shipping of

Egyptian grain to Constantinople to provide the civil

annona was an example of this, however the Arab

conquests of the seventh century led to a severe

economic retraction with the ending of the annona and

severe urban and rural demographic contraction. Only

the gold nomismata remained of what was unique of the

Late Antique economy in the eighth century.

The Empire’s economic fortunes appear to have

experienced revival from the beginning of the ninth

century. There was an uptick in climatic conditions,

the ‘little climatic optimum’, which enabled larger

agricultural surpluses and a steady increase in rural

demography.16 There was also an increase in the

monetary system and its use in commerce and exchange.

In Athens and Corinth the annual growth of the index

of coins is found respectively to be one and four

percent, leading to fourfold or sevenfold increase in

969 versus 820.17 Even if these coins were distributed

to the regions by salary payments to the army, their

presence is indicative that they were exchanged

locally for goods and services, integrating the local

population into a more monetised economy. There is 16 Bernard Geyer, ‘Physical factors in the evolution of the landscape and land use’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), p. 42.17 Angeliki E. Laiou and C. Morrisson, The Byzantine economy (Cambridge, 2007), p. 88.

8

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

both rural and urban demographic expansion in central

and northern Greece the tenth to thirteenth centuries

were marked by the retreat of trees and increased

agricultural exploitation.18 The building regulations

in the Book of the Eparch suggest that Constantinople

was growing rapidly in the late ninth and early tenth

centuries.19 Corinth too was experiencing population

growth.20 Tentatively the Byzantine Empire was

undergoing broad-based economic growth.

This was not solely a climatic phenomenon; the

expansion of the Byzantine Empire’s borders increased

the security of the core of the empire. Expansion also

secured the Empire’s grip on key communication and

trade routes. Basil II’s Bulgarian campaigns firmly

secured the Via Egnatia, an old Roman Road, across the

Balkans from Constantinople to Durazzo and thence to

Italy and the west. The capture of Crete in 961 and

Cyprus in 965 secured sea-routes in the Aegean and

were important maritime way stations opening up the

Islamic eastern Mediterranean to Byzantine mercantile

exploitation.21 Ships in the tenth century could not

tack headwinds so had to use the prevailing winds and

18 Archibald Dunn, ‘The exploitation and control of woodland and scrubland in the Byzantine world’, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 16(1992), p. 244.19 The Book of the Eparch, ch. 22.20 G.D.R Sanders, ‘Corinth’, in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic Historyof Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 647-654.21 Anna Avramea, ‘Land and sea communications, fourth-fifteenth centuries’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from theseventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 57-90.

9

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

currents. With the capture of Cyprus and Crete

Byzantine merchants had a clear advantage with their

northern approach for east-west voyages over their

Muslim counterparts.22 Byzantine Empire also had

excellent maritime connections with the Crimea and

then to the Eurasian steppes through the Don and the

Dnieper. It could take as little as one to four days

to travel from Constantinople to Cherson.23 With its

geographic position astride important communication

routes between the west, the Eurasian steppe and the

Near East, the Byzantine Empire and Constantinople in

particular, was physically able to communicate with

all three spheres of Shepard’s overlapping circles

thesis and is important for understanding Byzantine

commercial activity in the tenth century.24

The growth of Constantinople in the late ninth

and tenth centuries acted as a stimulus that

encouraged the creation of new trade routes and the

re-routing of others. The supply of foodstuffs and

goods to the growing population was an important spur

to monetised commerce and exchange. There was no

public annona system instead the city relied on a

22 John H. Pryor, Geography, Technology and War. Studies in the Maritime Historyof the Mediterranean (Cambridge, 1998), pp. 1-24.23 Jonathan Shepard, ‘’Mists and portals’: the Black Sea’s north coast’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries : the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), p. 423.24 Jonathan Shepard, ‘Byzantium’s overlapping circles’, in E. Jeffreys and F.K. Haarer (eds.), Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies : London, 21-26 August, 2006, vol. 1 (Aldershot, 2006), pp. 15-55.

10

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

system where farmers in provinces such as Bithynia and

Thrace relied on selling their goods onto to the

market to pay largely cash rents to the Byzantine

aristocracy, pay their taxes and support themselves.25

Other foods like legumes, fish, wine and olive oil

were transported and supplied through the mandatory

guilds.26 Laiou criticised the Book of the Eparch as it

discouraged innovation by merchants but as Maniatis

idealistically argued the regulations for grain, fish,

and other foodstuffs were attempting to prevent market

fragmentation, cap profit margins and price, not only

for ideological reasons but to stimulate volume and

increased supply.27 The only way a fish-broker, for

example, could increase his overall profits was to

import and sell more fish, thereby stimulating

production and increasing market competition for the

share of the catch.28

Supply routes in Constantinople stimulated the

creation of trade routes in Byzantine territories and

brought in regions peripheral or even outside the

Empire. The expansion of wine production in southern

25 Paul Magdalino, ‘The grain supply of Constantinople, ninth-twelfth centuries’ in C. Mango and G. Dagron (eds.), Constantinople and its hinterland (Aldershot, 1995), pp. 35-42.26 Book of the Eparch, ch. 13, 15, 16, 17, 1827 Laiou, ‘Byzantium and the Commercial Revolution’, p. 251; George C. Maniatisk, ‘The domain of private guilds in the Byzantine economy, tenth-fifteenth centuries’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers55 (2001), pp. 339-369.28 George C. Maniatis, ‘The organisational setup and functioning of the fish market in tenth century Constantinople’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54 (2000), pp. 13-42.

11

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Italy could be linked to exports to Byzantium first

articulated by Guillou through his analysis of a

surviving mid-eleventh century a brebio, or inventory,

drawn up in Reggio, the capital of the Calabrian

theme.29 The shipwreck at Serçe Limanu is famous for

collection of glassware, but the cargo included

thousands of grape seeds and amphora that suggests

that Byzantium was importing raisins and wine from

Syria.30 Even the north Black Sea was drawn into

Constantinople’s supply network. Hasdai ibn Shaprut

reported in the mid-tenth century from Byzantine

envoys that fish came to Constantiniple from the Sea

of Azov; the Byzantine-Rus trade treaty stipulated “If

Russian subjects meet with Khersonian fisherman at the

mouth of the Dnieper, they shall not harm them in any

way.”31 The DAI contains a reference to Chersonite salt

works between the Dnieper and the city, and there is

archaeological evidence of medieval fish salting pans

in Cherson and Bosporos.32 Shepard argues that the

export of salted fish from the north Black Sea Coast

29 Guillou, André, ‘Production and Profits in the Byzantine province of Italy (tenth to eleventh centuries): an expanding society’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 28 (1974), pp. 91-92.30 Frederick H. van Doornick, Jr., ‘The Byzantine ship at Serçe Limanu: an example of small-scale maritime commerce with Fatimid Syria in the early 11th century’ in R. Macrides (ed.), Travel in the Byzantine World (Aldershot, 2002), pp. 137-148.31 Shepard, ‘Mists and portals’, p. 427; The Russian Primary Chronicle. Laurentian Text, trans. and ed., S.H. Cross and O.P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (Cambridge, MA, 1953), p. 76.32 Constantine Porphyrogenita De Administrando Imperio, ed. and trans. Gy. Moravcsik and R.J.H. Jenkins (Washington D.C., 1967), ch. 42, lines 70-72, p. 187; Shepard, ‘Mists and portals’, p. 427

12

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

was as important to imperial authorities as local

Constantinopolitan supplies of fish.33

The commercial network supplying Constantinople

should not be seen as unique within the Empire.

Thessalonica was also supplied like Constantinople

with networks stretching across the Mediterranean and

Black Sea.34 Grain merchants from Constantinople were

prevented from entering. Cherson was heavily reliant

on foodstuff imports from Paphlagonia, a factor that

Constantine VII was very aware of.35 Though evidence is

strongest for Constantinople there appears to be a

commoditised market for foodstuffs across the Empire

in supplying its urban centres. Merchants from outside

the borders of the Empire, with Venice and the Rus

amongst others, wanted to be able to participate

alongside Byzantine merchants.

Byzantium, and Constantinople in particular, was

a major entrepôt for goods and not just foodstuffs and

this made it attractive for foreign merchants to

settle there. It was a centre of trade as well as a

place of consumption. According to Book 10 of the Book

of the Eparch, Constantinople had a large spice market

selling pepper, cinnamon, aloes wood, musk, myrrh and

other spices, dyes and perfumes concentrated between

the milarion and the ‘eikon of Christ’.36 The Ruses main

33 Shepard, ‘Mists and portals’, p. 427.34 Avramea, ‘Land and sea communications’, p. 70.35 De Administrando Imperio, ch. 53, lines 512-525, p. 287.36 The Book of the Eparch, ch. 10, clause 1.

13

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

commodity in their treaties appears to be slaves not

fur.37 Slaves and spices were amongst other goods that

were available for trade in Constantinople. It is

clear that in the tenth century that the Imperial

authorities were largely in control of the process of

settling foreign merchants in the city. The creation

of Italian merchant colonies by Romanos I Lekapenos

for the Amalfitans and Venetians near the Neorion

harbour on the Golden Horn was given from a position

of strength. Similarly the trade treaties with the Rus

in 907, 912 and 945 were concerned with balancing

incentives for Rus to come with security precautions.38

There was also a ‘Syrian’ population of merchants

resident in Constantinople. Importers and

manufacturers of spices were limited to three month

stays at their mitaton but the Book of the Eparch also

mentions there were also permanent Syrian merchants

living in the city for over ten years.39 There were

also a Jewish community in Constantinople; indeed the

Karaite sect flourished in the city as part of an

ethnic, religious and commercial network that

stretched from Iraq, Persia, Egypt to Iberia.40 Foreign

merchants could provide opportunities for Byzantine

merchants in partnerships as well as exchange. The 37 The Russian Primary Chronicle, pp. 73-77.38 Ibid., pp. 64-77.39 The Book of the Eparch, ch. 5; clause 2, 5.40 Solomon Dob Goitein, A Mediterranean society: the Jewish communities of the Arab world as portrayed in the documents of the Cairo Geniza, volume 1, Economic Foundations (Los Angeles, CA, 1967), p. 65; Ankori, Zvi, Karaites in Byzantium : the formative years, 970-1100 (Oxford, 1959).

14

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

shipwreck of Serçe Limanu contained personal

possessions with lead coming from the Rhodope

Mountains in Bulgaria, and the names on the amphora

indicated Greek and Bulgarian owners with a Leon,

Nikolaos, Michael, Iōannis and a Miroslav.41

Constantinople was not the only entrepôt in the

Byzantine Empire. Cherson connected the Rus and the

Pečenegs with goods from the Black Sea and

Constantinople.42 From the map of Cyprus in the Arabic

‘Book of Curiosities’, c. 1020-1050, Cyprus was a key

centre of trade between Byzantium and the Fatimids.43

Trebizond was a major node on the spice route with Ibn

Hawqal, a tenth century Arabic geographer, estimating

the kommerikon44 to be 72,000 nomismata per annum.45 Much

of the traffic of spices traded in Trebizond probably

then moved onto Constantinople. Constantinople and

Byzantium in general could be said to be the most

important market for goods and luxuries in the eastern

Mediterranean operating on the crossroads again

between north, south, east and west. Constantinople

was a major commercial hub operating in the eastern

41 van Doornick, Jr., ‘The Byzantine ship at Serçe Limanu’, pp. 139-140.42 De Administrando Imperio, ch. 6, lines 1-12; ch. 53, lines 528-535;Bartoli, Anne and Michel Kazanski, ‘Kherson and its region’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 659-665.43 Savage-Smith, Emily, ‘Maps and trade’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and internationalexchange (Farnham, 2009), p. 27.44 Customs revenue45 Laiou and Morrisson, Byzantine economy, pp. 83-84.

15

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Mediterranean comparable only to Alexandria in scale.

A foreign mercantile presence in Constantinople should

be interpreted as a sign of Byzantine commercial

strength, sophistication and vitality not as a

weakness. The legal system and hostels provided by

Imperial authorities for foreign merchants in

Constantinople has much in common with Polanyi’s

theory of the ‘port of trade’, but the level of

monetised profit-making exchange seen in the Book of

the Eparch and the Rus treaties indicated a more

sophisticated commercial system than the tribute and

barter system Polanyi envisaged.46

Niketas Choniates’ critique was not that

Constantinople was not a great market but that it made

the merchants of Constantinople lazy and beholden to

foreign merchants.47 The same argument can be found in

Oikonomides.48 The point can appear to be proved in the

Book of the Eparch with guild members of the

fishmongers and raw silk merchants, amongst others,

being banned from trading outside the city.49 However,

in Kitab surat al-ard (c. 988), Ibn Hawqal criticised the

Fatimids for allowing Byzantine ships and merchants to

enter Egyptian and Syrian ports during Tzimiskes’ 46 Polanyi, Karl, ‘’Ports of Trade’ in Early Societies’, Journal of Economic History 23 (1963), pp. 30-45; Laiou, Angeliki E., ‘Exchange and noneconomic Exchange’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 681-696.47 Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium, p. 213.48 Oikonomides, ‘The economic region of Constantinople’, pp. 221-238.49 The Book of the Eparch, ch. 6, 17.

16

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

eastern campaigns; he believed they were acting as

spies.50 A letter in the Jewish Cairo Genizah of 959

recorded that there was a ‘Market of the Greeks’ (shuq

ha-Yevanim) in Fustat.51 By the end of the tenth century

there were Amalfitan and Venetian merchants in Egypt,

but they were outnumbered by Byzantine ships and

merchants.52 In the tenth century all Latin and Greek

Christian traders in the Genizah are called Rumi. The

conflation of Venetian and Amalfitan merchants with

Byzantine ones may be due to Italian merchants sailing

and trading under some form of protection of the

Byzantine Emperor or that their numbers were low

compared to the number of Greek Byzantine operating in

the eastern Mediterranean. It was only after the First

Crusade that a distinction between Ifranj (Franks) and

the Rumi (Greeks) became clearer.53

Tenth-century Egypt benefited from structural

changes in the spice and incense trade that shifted

from the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea and Alexandria.

This shift was due to the political instability of the

Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad.54 Byzantine merchants in

Egypt were active in buying spices, but it was not a

one-way exchange. Byzantine merchants, as well as

Venetians, exported timber from Cyprus, Crete and Asia

50 David Jacoby, ‘Byzantine trade with Egypt from the mid-tenth century to the Fourth Crusade’, Thesaurismata 30 (2000), p. 35.51 Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, p. 44.52 Jacoby, ‘Byzantine trade with Egypt’, p. 37.53 Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, p. 43.54 Jacoby, ‘Byzantine trade with Egypt’, pp. 30-31.

17

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Minor to provide shipbuilding material for the

construction of the Fatimid navy.55 Byzantine merchants

also exported classical pharmacological plants like

dodder of thyme from Crete, or Mastic gum from Chios;

silk textiles and furniture and even cheese from Crete

and Asia Minor.56 It becomes clear that in the tenth

century Egypt and Byzantium were increasingly

economically interdependent which only increased after

the Fatimid conquest in 969.

Byzantium and Fatimid Egypt were more than

economically interdependent, they were culturally

interlinked as well. In Shepard’s influential

‘overlapping circles’ thesis, Byzantium’s power came

from the application of its cultural, religious and

historical prestige across three spheres; one to the

north on the Eurasian steppe with the Rus; another to

the west in Latin Europe and a final one to the east

in the Islamic Near East.57 Due to its classical

inheritance, Christian heritage and widely

acknowledged antiquity Byzantine styles, manufactures

and fashions became a mark of taste across all three

spheres. Constantinopolitan polychrome white tiles

have been found in Preslav in Bulgaria and in the

55 Ibid., 36; Donald M. Nicol, Byzantium and Venice: a study in diplomatic andcultural relations (Cambridge, 1989), pp. 39-42.56 Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, pp. 46-47, p. 124; Anne McCabe, ‘Imported ‘materia medica’, 4th-12th centuries and Byzantine pharmacology’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 273-291.57 Shepard, ‘Byzantium’s overlapping circles’, pp. 15-55.

18

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Grand Ummayad Mosque in Cordoba.58 Similarly, the silk

textiles were equally revered by Abbasid Caliphs,

Jewish brides in Damascus, Hugh of Italy, the Rus

king’s burial in Ibn Fadlan and even in Britain.59 The

Byzantine state had its own craftshops producing high-

quality silk textiles, especially for dyeing textiles

with purple murex due.60 It can thus be difficult to

distinguish between silks that were gifted by the

Byzantine state and those produced and sold

commercially in Constantinople. Gift exchanges to the

Abbasid Caliph or King Hugh of Italy were not

economic, according to the typology of Mauss, but they

did prime demand for the commercial market as

Byzantine silks became status and elite objects in

foreign societies.61 In Egypt, where local supplies of

silk textiles were available, Byzantine silks were

58 R.B. Mason and M.M. Mango, ‘Glazed ‘tiles of Nicomedia’ in Bithynia, Constantinople and elsewhere’ in C. Mango and G. Dagron(eds.), Constantinople and its hinterland (Aldershot, 1995), pp. 313-331; Rossina Kostova, ‘Polychrome ceramics in Preslav, 9th to 11th centuries: where were they produced and used’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 273-291.59 Book of Gifts and rarities (Kitab al-Hadaya wa al-Tuhaf): sections compiled in the fifteenth century from an eleventh-century manuscript on gifts and treasures, trans.Ghada al-Hijjawi al-Qaddumi (Cambridgem MA, 1996), pp. 99-101; Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, p. 46; Ibn Fadlan’s journey to Russia: a tenth-century traveller from Baghdad to the Volga river, trans. Richard Frye (Princeton, NJ, 2002), p. 67; Anna Muthesius, ‘Silken diplomacy’ in J. Shepard and S. Franklin (eds.), Byzantine diplomacy: papers from the twenty-fourth spring symposium of Byzantine studies (Aldershot, 1992), pp.237-248.60 Anna Muthesius, ‘Essential processes, looms, and technical aspects of the production of silk textiles’, in A.E. Laiou (ed.),The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 147-168.61 Laiou, ‘Economic and noneconomic exchange’, pp. 692-693.

19

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

still prized for their quality and their rarity value.

Liudprand of Cremona tartly noted that silks like the

ones he attempted to smuggle were available on the

open market in Venice.62 The Book of the Eparch also

devotes chapters 6, 7, and 8 to the silk trade and the

manufacturing process for the commercial market and

the strict regulations the state tried to impose on

the production process.63 Both of these indicate that

there was a considerable commercial market for

Byzantine silks whether they were smuggled out or as

legal exports.

Byzantium through its high-value manufactured

goods was capturing the ‘added-value’ of processing

raw materials like silk, gold, silver, enamels and

glass into goods and art that were desired across the

Near East and Europe. These ‘industries of art’

produced wealth and earned commercial profits even if

they were not being bought for their classical

virtues, but their craftsmanship and the weight of

precious materials contained within them, as Brubaker

argues.64 The Book of the Eparch and the treaties with

the Rus restricted the value of silks that could be

bought by foreign merchants to ten nomismata and those 62 Liudprand of Cremona, Legatio in Paolo Squatriti (trans.), The Complete works of Liudprand of Cremona (Washington D.C., 2007), ch. 53-55.63 The Book of the Eparch, ch. 6-8.64 Anthony Cuttler, ‘The Industries of Art’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 555-587; Brubaker, Leslie, ‘Material culture and the myth of Byzantium, 750-950’ in G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (eds.), Europa medieval e mondo Bizantino (Rome, 1997), p. 41.

20

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

that did not have the stamp of the eparch but there

were just as heavy punishments for allowing trained

silk workers to leave the city.65 In his work on

‘archaic globalisation’, C.A. Bayly argued that it

was the skills of craftsmen that were prized in pre-

modern economies and that they had to be jealously

guarded.66 The retention of these skills and the

attempted restriction of supply in the tenth century

meant Byzantine silks and other products still had a

commercial advantage and caché. It is still unclear

whether silk production took place outside

Constantinople in the tenth century but with painted

glassware bracelets it seems there were production

centres in Corinth, Cherson and Amorion as well as the

capital. These bracelets have been found across the

empire but also on all major trade routes in Russia,

Fustat and even one in Sweden.67 Whilst the evidence

for Constantinople is strongest it is probable that

urban centres across the Byzantine Empire were

involved in creating goods that were then exported.

The carry trade was less profitable than the added

value gained from the manufacturing process.

65 The Book of the Eparch, ch 8; clause 3, 5, 7, 966 Christopher Bayly, ‘’Archaic’ and ‘Modern’ Globalisation in the Eurasian and African Arena, c.1750-1850’ in A.G. Hopkins (ed.), Globalization in World History (London, 2002), pp. 47-73.67 Natalija Ristovska, ‘Distribution patterns of middle Byzantinepainted glass’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: thearchaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 199-220.

21

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Byzantine commercial strength can be measured

through the entrepôts it controlled, the goods it

produced, the commercial networks operating within it

and the quality and desirability of its goods were its

underpinnings. Tenth century Byzantium was the major

commercial power in the eastern Mediterranean and the

Byzantine state was aware of its diplomatic potential.

The famous 992 chrysobull granted to Venice by Basil

II that granted tax-relief was used to entice Venetian

merchants to Constantinople, and strengthen a key and

traditional ally against growing Ottonian influence in

northern Italy.68 Similarly, diplomatic pressure by

John Tzimiskes led to a Venetian and Byzantine embargo

on timber exports to the Fatimids in 971 when the

emperor was on campaign.69 Trade agreements could be

agreed with the Shia Fatimids as well as Christian

Venice. In 987/88 Basil II also concluded a treaty

with Caliph al-‘Aziz, which enabled Byzantine freedom

of trade in Fatimid territories, and allowed for the

proclamation of the caliph’s name in the mosque for

Muslim merchants in their mitaton.70

The Byzantine state was also keenly aware of the

value of customs revenue (the kommerikion) it could

levy on trade. Trebizond, Hieron and Abydos on the

68 Nicol, Byzantium and Venice, pp. 39-42.69 David Jacoby, ‘Venetian commercial expansion in the eastern Mediterranean, 8th-11th centuries’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange(Farnham, 2009), pp. 371-391.70 Jacoby, ‘Byzantine trade with Egypt’, p. 36.

22

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Dardanelles were important choke-points for trade that

the empire used to control and tax trade.71 Romanos I

Lekapenos’s attempted annexation of Ardanouj in the

Caucasus was linked to controlling the trade links

passing through the city to Trebizond.72 It could also

explain Basil II’s naval campaigns against “Chazaria”

in the Crimea in 1017; the towns of Bosporos and

Tmutarakan controlled the strategic route through the

Straits of Kerch, and the long-term Byzantine interest

in holding Ani as a possession though their prominence

may have stemmed from their location outside imperial

territory in neutral ground.73 Byzantine expansionism

had a commercial aspect to it.

When Shepard spoke of the overlapping circles he

was re-conceptualising Byzantium as a cultural,

theological and ideological entity, rather than as a

straightforward territorial empire. He was attempting

to explain why Byzantium had the considerable

influence on its neighbours, be they Christians, Rus

pagans or Islamic caliphs and thus ensured its

survival, so the hard power it wielded appeared

deceptively strong. I would argue that a commercial

addendum to Shepard’s thesis is necessary. Tenth

century Byzantine commerce was a dynamic and thriving

71 Oikonomides, ‘The economic region of Constantinople’, pp. 221-238.72 De Administrando Imperio, ch. 46, pp. 217-223.73 John Skylitzes, A synopsis of Byzantine history, 811-1057, trans. John Wortley (Cambridge, 2010), p. 336; Shepard, ‘Mists and portals’, p. 441.

23

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

force. It was a physical link through which goods of

Byzantium could flow and influence neighbouring

cultures as effectively as the Orthodox church. The

profits earned and taxed helped to fund Byzantine

expansion and possibly encouraged it and its merchants

and lawyers were at the forefront of creating new

partnerships and contracts for commerce that were, at

least, the inspiration, if not directly borrowed, by

merchants of Venice, Genoa and Amalfi. The spread of

Byzantine ideas and culture can often be characterised

by its travelling monks and clergy, but its merchants

were as important, albeit rather underappreciated by

Niketas Choniates and other historians who have

followed him.

24

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Book of Gifts and rarities (Kitab al-Hadaya wa al-Tuhaf): sections compiled in the fifteenth century from an eleventh-century manuscript ongifts and treasures, trans. Ghada al-Hijjawi al-Qaddumi (Cambridgem MA, 1996).

Constantine Porphyrogenita De Administrando Imperio, ed. and trans. Gy. Moravcsik and R.J.H. Jenkins (Washington D.C., 1967).

Ibn Fadlan’s journey to Russia: a tenth-century traveller from Baghdad to the Volga river, trans. Richard Frye (Princeton, NJ, 2002).

The Russian Primary Chronicle. Laurentian Text, trans. and ed., S.H. Cross and O.P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (Cambridge, MA, 1953).

‘Ordinances of Leo VI, c.895, from the Book of the Eparch’, trans. E.H. Freshfield from Roman Law in the Later Roman Empire: Byzantine guilds, professional and commercial (Cambridge, 1938).

Bass, George F.; Sheila D. Matthews; J. Richard Steffyand Frederick H. van Doornick, Jr., Serçe Limanu: an eleventh-century shipwreck, volume one: the ship and its anchorage, crewand passengers (College Station, TX, 2004).

25

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

John Skylitzes, A synopsis of Byzantine history, 811-1057, trans. John Wortley (Cambridge, 2010)

Liudprand of Cremona, Legatio in Paolo Squatriti (trans.), The Complete works of Liudprand of Cremona (Washington D.C., 2007).

Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium: annals of Niketas Choniates, trans. Harry I. Magoulias (Detroit, 1984).

Secondary Sources

Ankori, Zvi, Karaites in Byzantium : the formative years, 970-1100 (Oxford, 1959).

Avramea, Anna, ‘Land and sea communications, fourth-fifteenth centuries’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 57-90.

Bartoli, Anne and Michel Kazanski, ‘Kherson and its region’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (WashingtonD.C, 2002), pp. 659-665.

Bayly, Christopher, ‘’Archaic’ and ‘Modern’ Globalisation in the Eurasian and African Arena, c.1750-1850’ in A.G. Hopkins (ed.), Globalization in World History (London, 2002), pp. 47-73.

Brubaker, Leslie, ‘Material culture and the myth of Byzantium, 750-950’ in G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (eds.), Europa medieval e mondo Bizantino (Rome, 1997), pp. 33-41.

Cuttler, Anthony, ‘The Industries of Art’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 555-587.

26

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

van Doornick, Jr., Frederick H., ‘The Byzantine ship at Serçe Limanu: an example of small-scale maritime commerce with Fatimid Syria in the early 11th century’ in R. Macrides (ed.), Travel in the Byzantine World (Aldershot, 2002), pp. 137-148.

Dunn, Archibald, ‘The exploitation and control of woodland and scrubland in the Byzantine world’, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 16 (1992), pp. 235-298.

Geyer, Bernard, ‘Physical factors in the evolution of the landscape and land use’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 31-45.

Guillou, André, ‘Production and Profits in the Byzantine province of Italy (tenth to eleventh centuries): an expanding society’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 28 (1974), pp. 89-109.

Goitein, Solomon Dob, A Mediterranean society: the Jewish communities of the Arab world as portrayed in the documents of the Cairo Geniza, volume 1, Economic Foundations (Los Angeles, CA,1967).

Harvey, Alan, Economic expansion in the Byzantine empire, 900-1200 (Cambridge, 1989).

Horden, Peregrine and Nicholas Purcell, The corrupting sea : a study of Mediterranean history (Oxford, 2000).

Jacoby, David, ‘Byzantine trade with Egypt from the mid-tenth century to the Fourth Crusade’, Thesaurismata 30 (2000), pp. 25-77.

Jacoby, David, ‘Venetian commercial expansion in the eastern Mediterranean, 8th-11th centuries’ in M.M. Mango(ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 371-391.

27

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Kazhdan, Alexander, ‘State, feudal and private economyin Byzantium’, Dumbartion Oaks Papers 47 (1993), pp. 83-100.

Kostova, Rossina, ‘Polychrome ceramics in Preslav, 9th to 11th centuries: where were they produced and used’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 273-291.

Laiou, Angeliki E., ‘Byzantium and the Commercial Revolution’, in G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (eds.), Europa medieval e mondo Bizantino (Rome, 1997), pp. 239-253.

Laiou, Angeliki E., ‘Economic thought and ideology’ inA.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 1123-1144.

Laiou, Angeliki E., ‘Exchange and noneconomic Exchange’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (WashingtonD.C, 2002), pp. 681-696.

Laiou, Angeliki E., ‘Exchange and trade, seventh-twelfth centuries’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 697-770.

Laiou, Angeliki E. and C. Morrisson, The Byzantine economy(Cambridge, 2007).

Lopez, Roberto Sabatino, The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1976).

Magdalino, Paul, ‘The grain supply of Constantinople, ninth-twelfth centuries’ in C. Mango and G. Dagron (eds.), Constantinople and its hinterland (Aldershot, 1995), pp. 35-47.

Magdalino, Paul, ‘Medieval Constantinople: built enviromen and urban development’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.),

28

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 529-537.

Mango, Marlia Mundell, ‘The Commercial Map of Constantinople’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54 (2000), pp. 189-207.

Maniatis, George C., ‘Organisation, market structure, and Modus Operandi of the private silk industry in tenth-century Byzantium’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 53 (1999), pp. 263-332.

Maniatis, George C., ‘The organisational setup and functioning of the fish market in tenth century Constantinople’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54 (2000), pp. 13-42.

Maniatis, George C., ‘The domain of private guilds in the Byzantine economy, tenth-fifteenth centuries’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001), pp. 339-369.

Maniatis, George C., ‘The corps of overseers of the equestrian trade market of Constantinople, tenth-twelfth centuries’, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 34/2 (2010), pp. 142-159.

Maridaki-Karatza, Olga, ‘Legal Aspects of the Financing of Trade’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 1105-1120.

Mason, R.B. and M.M. Mango, ‘Glazed ‘tiles of Nicomedia’ in Bithynia, Constantinople and elsewhere’ in C. Mango and G. Dagron (eds.), Constantinople and its hinterland (Aldershot, 1995), pp. 313-331.

McCabe, Anne, ‘Imported ‘materia medica’, 4th-12th centuries and Byzantine pharmacology’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 273-291.

29

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Muthesius, Anna, ‘Silken diplomacy’ in J. Shepard and S. Franklin (eds.), Byzantine diplomacy: papers from the twenty-fourth spring symposium of Byzantine studies (Aldershot, 1992), pp. 237-248.

Muthesius, Anna, ‘Essential processes, looms, and technical aspects of the production of silk textiles’,in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from theseventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 147-168.

Nicol, Donald M., Byzantium and Venice: a study in diplomatic and cultural relations (Cambridge, 1989).

Oikonomides, Nicolas, ‘The economic region of Constantinople: from directed economy to free economy and the role of the Italians’, in G. Arnaldi and G. Cavallo (eds.), Europa medieval e mondo Bizantino (Rome, 1997), pp. 221-238.

Oikionomides, Nicolas, ‘The role of the Byzantine State in the economy’ in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 973-1058

Polanyi, Karl, ‘’Ports of Trade’ in Early Societies’, Journal of Economic History 23 (1963), pp. 30-45.

Pryor, John H., Geography, Technology and War. Studies in theMaritime History of the Mediterranean (Cambridge, 1998), pp. 1-24.

Reinert, Stephen W., ‘The Muslim presence in Constantinople, 9th-1th centuries: some preliminary observation’ in H. Ahrweiler and A.E. Laiou (eds.), Studies on the internal diaspora of the Byzantine Empire (Washington D.C., 1998), pp. 125-150.

Ristovska, Natalija, ‘Distribution patterns of middle Byzantine painted glass’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 199-220.

30

Was Byzantium a major commercial force?

Sanders, G.D.R., ‘Corinth’, in A.E. Laiou (ed.), The Economic History of Byzantium: from the seventh through the fifteenth century (Washington D.C, 2002), pp. 647-654.

Savage-Smith, Emily, ‘Maps and trade’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries: the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 15-29.

Shepard, Jonathan, ‘Constantinople- gateway to the north: the Russians’ in C. Mango and G. Dagron (eds.),Constantinople and its hinterland (Aldershot, 1995), pp. 243-260.

Shepard, Jonathan, ‘Byzantium’s overlapping circles’, in E. Jeffreys and F.K. Haarer (eds.), Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies : London, 21-26 August, 2006, vol. 1 (Aldershot, 2006), pp. 15-55.

Shepard, Jonathan, ‘’Mists and portals’: the Black Sea’s north coast’ in M.M. Mango (ed.), Byzantine trade, 4th-12th centuries : the archaeology of local, regional and international exchange (Farnham, 2009), pp. 421-441.

Teall, John L., ‘The grain supply of the Byzantine Empire, 330-1025’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 13 (1959), pp. 87-139.

Udovitch, Abraham L., ‘At the origins of the Western Commenda: Islam, Israel, Byzantium?’, Speculum 37/2 (1962), pp. 198-207.

Whittow, Mark, ‘The Middle Byzantine Economy (600-1204)’ in J. Shepard (ed.), The Cambridge history of the Byzantine Empire. c. 500-1492 (Cambridge, 2010), pp. 465-492.

31