Visual Style and the Looking Subject: Nell Brinkley's Illustrations of Modern Womanhood

Transcript of Visual Style and the Looking Subject: Nell Brinkley's Illustrations of Modern Womanhood

This article was downloaded by: [UAA/APU Consortium Library]On: 12 February 2014, At: 17:27Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Women's Studies in CommunicationPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uwsc20

Visual Style and the Looking Subject:Nell Brinkley’s Illustrations of ModernWomanhoodHeather Brook Adams aa Department of English , University of Alaska Anchorage ,Anchorage , Alaska , USAPublished online: 12 Feb 2014.

To cite this article: Heather Brook Adams (2014) Visual Style and the Looking Subject: Nell Brinkley’sIllustrations of Modern Womanhood, Women's Studies in Communication, 37:1, 90-110, DOI:10.1080/07491409.2013.867917

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2013.867917

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Visual Style and the Looking Subject: NellBrinkley’s Illustrations of Modern Womanhood

HEATHER BROOK ADAMS

Department of English, University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage,Alaska, USA

Comics artist Nell Brinkley’s early twentieth-century line drawings engageprovocative themes related to emerging expressions of and questions about modernwomanhood. Brinkley’s visually complex rhetorical techniques (strategicjuxtaposition, visual chiasmus, inversion, and motif) create a space for audiencecontemplation, and her use of the female ‘‘looking subject’’ produces a meta-discourseon the gendered politics of looking. This article examines these stylistic and thematicchoices through a feminist visual rhetorical analytic lens.

Keywords aesthetic techniques, comics, feminist art, visuality, visual rhetoric,working-class women

In 1913, comics illustrator Nell Brinkley received a fan letter that so moved her, shewrote about it to a colleague.

Here in my inky fist I hold a letter . . . from one of the valiant army of girlswho do battle shoulder to shoulder with the men . . .Plain and square andtyped, smelling of just clean air, the very sign and symbol of the trim, black-and-white, sane and cleanly sort of brainy girl it came from. [The] girlhad just covered a mile, more or less, of city streets on a stout pair ofpumps . . .The square white letter says—courteously and appealingly—‘‘Make if you please once, not the splendid creature of leisure and plenty,but just the plain business girl! There are a lot of us, you know.’’ (qtd. inRobbins, Nell Brinkley 57)

Brinkley was a rising star among illustrators and a daily contributor to the New YorkEvening Journal from 1907 through the 1930s. Her elaborate line drawings of variouskinds of bright-eyed, urban women captured the ebullience of youth and the spirit ofthis time of rapid social change. For scholars of visual rhetoric interested in women’srhetorical production, representations by and about women, and artistic techniquescalling attention to the gender politics of visual culture, Brinkley’s work offers a valu-able site of investigation. More than drawings of pretty ‘‘girls,’’ Brinkley’s pictorialexpositions1 explore women’s changing social roles and invite audiences to criticallyassess gendered assumptions about modern womanhood. This approach allowsBrinkley to engage a cultural preoccupation with women’s increasing public presence

Address correspondence to Heather Brook Adams, Department of English, Universityof Alaska Anchorage, 3211 Providence Dr., ADM 103-K, Anchorage, AK 99508-4614,USA. E-mail: [email protected]

Women’s Studies in Communication, 37:90–110, 2014Copyright # The Organization for Research on Women and CommunicationISSN: 0749-1409 print=2152-999X onlineDOI: 10.1080/07491409.2013.867917

90

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

through visual compositions that inspire contemplation instead of delivering asingular message.

To make these claims about Brinkley’s work, I employ feminist visual analysis—a lens that leverages visual rhetorical theory to address how images represent gender,allow or deny access (by the artist and her audiences), and rhetorically sustain, chal-lenge, or subvert existing forms of gendered power. Specifically, I employ a two-partanalytical frame to examine both the nature and function of Brinkley’s texts.2

Starting with close textual analysis, I ask three interrelated questions. What isdepicted? How is the work designed=composed? And finally, how does this construc-tion facilitate the image’s rhetorical function? Letting these questions guide myanalysis, I consider my observations in light of the gender dynamics readily availableto the rhetor and the audiences of the text. I then move onto broader conceptualconcerns, asking, How might the image disrupt or reconfigure gendered politics ofvisuality? For this particular study, I further refine this question to address a politicsof looking. My hope is that this methodological approach not only applies rhetoricalanalysis to images that might be valuable artifacts from a feminist perspective butalso supports the development of ‘‘broader theoretical conclusions about the powerof images’’ (Messaris 211) in relation to gendered structures of power.

In what follows, I recuperate a selection of Brinkley’s ink drawings and identifythree stylistic characteristics of these compositions that allow the artist to visuallycreate a space for expanding and contesting dominant notions of womanhood ofher day. First, Brinkley incorporates a range of subjects (e.g., working women andwomen of the leisure class) and strategically juxtaposes these subjects within a singlepanel, thus enabling perspective by incongruity and challenging the visual typogra-phy of identity categories popular during her time. This technique invites audiencesto reconsider assumed differences among incongruous subjects.

In addition, Brinkley’s work uses what I refer to as visual chiasmus as well as‘‘refigured’’3 motif to enhance the play of meaning within her panels. Takentogether, these graphic strategies enable Brinkley to engage provocative themes with-out off-putting audiences because they deliver balance and elegance—characteristicsthat appeal to audiences’ sense of fairness and beauty.

Finally, Brinkley’s female ‘‘looking subjects’’—subjects who are depictedexplicitly looking at one another—function as a medium for self-referentially explor-ing the act of looking. Brinkley’s use of looking subjects aligns with her largerpreoccupation with questioning how, why, and to what end people assess difference.However, these particular compositions can be understood as graphic scripts thatinvite female readers to practice looking and experientially resist their customarypositioning as gazed-upon objects. Given modern women’s evolving but vexedrelationship to visuality, these compositions can be appreciated for their originalityand rhetorical significance.

In this article, I begin by reviewing literature on visual rhetoric to identifyresources for feminist scholars conducting visual analysis. I next provide a biographi-cal overview of Brinkley before situating her work within its larger historical context.With this background in place, I then analyze five of Brinkley’s panels, suggestingthat their reliance on subject selection, strategic juxtaposition, visual chiasmus,refigured motif, and depictions of looking subjects encourage readers to reflect upontheir own visual and conceptual associations with womanhood. I conclude by sug-gesting that Brinkley’s compositions—with their aesthetic appeal and use of stylisticstrategies—showcase not only her artistry but also her ability to invite audiences to

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 91

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

engage her works actively, creating a space for critical contemplation rather thandidacticism.

Toward a Feminist Visual Analysis

As suggested, this article models one method of feminist visual analysis, a move thatextends the work of visual scholars, some of whom already investigate the relation-ship between graphic arts and issues of gender and rhetoric. Feminist rhetoricalscholars have been active contributors to visual rhetorical studies, accounting forthe ways that visual mediums, broadly defined, have enabled or constrainedwomen’s rhetorical production. For example, Mari Boor Tonn suggests that visualtechnologies bolstered the ethos of Mary Harris ‘‘Mother’’ Jones; and Sonja K. Fossmakes a case for how multimodality can be a strategy used to ‘‘empower and legit-imize women’s authentic voice’’ (‘‘Judy Chicago’s’’ 17). In addition, Anne Demo(‘‘Guerilla’’) identifies the visual means by which the activist Guerilla Girls haveconstructed rhetorics of subversion and resistance; and Jenna Vinson contends thatvisual images of pregnant teenagers in the popular press have obscured the racialpolitics of teen pregnancy. Wendy S. Hesford’s theoretical work on spectacle,‘‘discourses of vision’’ (23), representation, and human rights rhetoric contributessignificantly to the conceptual tools available to feminist rhetorical scholars examin-ing still and moving photographic images.

Graphic work by women, or depicting issues faced by women, has been a morenarrow but nonetheless fruitful site of study. Michele E. Ramsey and CatherineH. Palczewski, for example, have explained how visual arguments shaped therhetorical context in which U.S. women agitated for suffrage. Hillary Chute andLaura R. Micciche study more recent graphic works, like memoirs and comic books,that depict women’s experiences with emotional and physical violation. Chute recog-nizes comics as an apt medium for life writers (many of whom are women) grapplingwith trauma that leaves emotional and psychological scars, which can incapacitateexpression (Chute 2–3). And Micciche contends sequential comics that feature‘‘disturbing’’ subject matters, such as incest, force readers to ‘‘deal with the gapbetween seeing and knowing’’ (18) that literally and symbolically appears in visualstorytelling forms.

Works like those of Ramsey, Palczewski, Chute, andMicciche contribute to grow-ing attention to graphic and comics rhetorical production, a line of inquiry inaugu-rated by Kathleen J. Turner. Encouraging communication scholars to appreciatethe rhetoricity of comics, Turner argues that these texts reflect and influence thesociety from which they emerge as they draw upon readers’ imaginations and helpshape notions of the possible. Turner’s work helped legitimize the study of graphictexts, and subsequent rhetorical scholarship has conceptualized pictorial persuasion(Olson), defined the visual ideograph (Edwards and Winkler), explained how wordsare expressed through visual strategies (Bates, Lawrence, and Cervenka), and theo-rized comics as narrative journalism (Lunsford and Rosenblatt). Each such studymakes a case for how drawn images function as sites of rhetorical invention and per-suasion that encourage active and imaginative participation by audiences, expandingthe repertoire of analytical tools rhetoricians can apply to their study of graphic works.

This attention to graphic=visual rhetoric also provides a basis for exploringquestions of gender, power, and expression that arise in pictorial images. My feministvisual analysis begins with the four ‘‘fundamental rhetorical issues’’ of gender and

92 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

power that Cheryl Glenn articulates in Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence. In any givenrhetorical situation, according to Glenn, one might examine ‘‘power, performance,and societal expectation’’ by asking ‘‘who speaks, who remains silent, who listens,and what [can] those listeners [. . .] do’’ (23). These questions can extend to visualrhetoric, prompting additional questions such as who sees, who is seen, and who isabsent? Such lines of inquiry can serve as a basis for exploring how the aesthetic oremotional quality of graphic arts might shape a medium’s rhetorical power and whatthese questions might mean for feminist analysis. Remembering feminist art historianGriselda Pollock’s call to ‘‘take seriously’’ aesthetics as a site of affectivity ‘‘so deeplylinked with the very processes of sexual difference’’ that it functions as a ‘‘creativelaboratory for what might one day become a social strategy or a new way of thinking’’(xxxiii) underscores the potential value of such an approach. In short, visual analysisattentive to issues of gender and power is one way to explore how through graphicmediums our ‘‘ways of seeing’’—and our ways of seeing gender—are, in the wordsof Demo, ‘‘modified, normalized, and (eventually) eclipsed’’ (‘‘Sovereignty’’ 298).

Understanding Brinkley: The Artist and Her Milieu

Raised in Colorado, Brinkley sold her first piece of art at age thirteen and was ‘‘discov-ered’’ by William Randolph Hearst, who relocated her to New York in 1907 to join thestaff of the New York Evening Journal (NYEJ) as an illustrator (Robbins, Nell Brinkley27; The Brinkley Girls 7). The NYEJ was part of Hearst’s booming business ofsensational, headline-driven, penny newspapers.4 Despite (or because of) its penchantfor exaggeration, the newspaper was wildly popular, outselling competing publicationssuch as the New York Times and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. Indeed, the NYEJenjoyed the largest readership of any U.S. evening newspaper (New York EveningJournal, n.p.). For Brinkley, this meant that her work would be seen by hundreds ofthousands of households representing different economic backgrounds.5 The NYEJbroke journalistic ground with its image-heavy style of reporting. As part of Hearst’scelebration of individual achievement, the paper was also unique in granting credit linesto its many contributors, including artists and, later, staff photographers (Flukinger).For these various reasons Brinkley gained renown among a vast readership—includinglow-income laborers as well as the growing number of middle-class households. Shortlyafter being hired, Brinkley was charged with illustrating the trial of infamous murdererHarry K. Thaw. Her drawings of Evelyn Nesbitt, modern ‘‘it’’ girl and wife of Thaw,rocketed her to national fame. Within several years, Brinkley was syndicated inall Hearst newspapers (Robbins, The Brinkley Girls 9). By 1913 a host of artists wasimitating Brinkley’s style; by the 1920s her image and name were used to advertisewomen’s beauty products; and by 1926 a newspaper industry magazine identified heras the most emulated artist in the world (Robbins, Nell Brinkley 47–51).

Although a primary contributor to the popular visual rhetoric of her time,Brinkley has largely faded from public memory and has drawn scant critical attention.Her color serial, ‘‘Golden Eyes and Her Hero, Bill,’’ dominates the limited recovery ofher work and showcases her patriotic art.6 Brinkley’s line drawings, however, remainlargely unpreserved despite their original circulation and popularity.7 Despite being bothprolific and beloved, Brinkley has been nearly erased from history, likely because herwork appeared in a daily newspaper read by the masses.

Brinkley’s art can be situated in the so-called golden age of illustration, afifty-year span between 1880 and 1930. According to historian Nancy Martha West,

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 93

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

during these years ‘‘noted’’ illustrators were granted ‘‘unprecedented authority’’ toserve as links between ‘‘the exclusive and confined world of fine art and the massifieddemands of the consumer public’’ (130). Female illustrators faced tremendous chal-lenges, despite the fact that, by the first decade of the new century, women wereenrolled in public and private art schools and participated in a blossoming artsand craft movement (Tickner 13). Nevertheless, women met fierce resistance whenthey fashioned themselves professionals, because the notion of a female artist wasthought oxymoronic; women could not make good art—and if they did, they wereunsexed in the process.

Illustration was, however, perceived to be less serious than other art forms andtherefore an acceptable ‘‘craft’’ for women, in part because many female illustratorsfocused on domestic or romantic themes (Robbins, Nell Brinkley 32–33). Forexample, the work of JessieWillcox Smith, a leading female illustrator around the turnof the twentieth century, primarily depicted children. Illustration as hobby work wasthought to allow women the time and energy to focus on their ‘‘primary’’ responsibi-lities as wives and mothers (Waldrep vii). One among the growing number of womenwhose work went unrecognized by the male-dominated world of high art, Brinkleypenned slender women with full faces, wide eyes, and cascading hair—women whoseemed awash in youthful romance. It is no wonder her popularity soared.

Brinkley’s ink compositions were featured on the NYEJ’s Magazine Page,a section of the newspaper specifically composed for its female readers. The NYEJpeddled its share of tawdry headlines, covering stories of disappearances, violent crime,political corruption, and bootlegging stings. Advertisements throughout the paper—like those for Lord and Taylor, Ivanhoe Tobacco, and Wrigley’s Gum—suggestthat its audience did, in fact, span a fairly wide economic range. The Magazine Pagefeatured columns such as ‘‘Meditations of a Wife,’’ ‘‘The Husband Hunters,’’ and‘‘Fashion Fads and Fancies,’’ which functioned as primers for women’s upwardmobility and endorsed traditional, gendered notions of women’s domestic interests.Brinkley’s illustration dominated the center of the page, directly below the headline,which surely attracted the attention of many readers, especially women.

This article examines a selection of Brinkley’s drawings from an incompletecollection of microfilmed NYEJ issues.8 I analyze five pictorial expositions fromthe hundreds I culled, identifying those that (a) feature multiple subjects and (b)explicitly address (or call into question) issues related to women’s economic, polit-ical, and=or ethnic identities. For the sake of space and depth of analysis, I furtherrefined my focus, choosing several representative panels that were published across aspan of Brinkley’s career. Although this method of selection did not result in randomsampling, I avoided exclusively choosing panels that might have responded to onlyone historic moment, such as passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. After settlingon these works, I used them to guide my inductive and contextual visual analysis.

Brinkley’s Stylistic Visual Strategies

A close analysis of Brinkley’s line drawings suggests why these texts might haveinitially attracted audiences and how their visual design rhetorically functions toencourage cognitive dissonance and reflection. Brinkley’s subject selection, strategicjuxtaposition, stylistic techniques of inversion, and refigured use of motif allow herto engage sensitive and disputed themes and visually construct indeterminate imagesthat push audiences to rely on their own powers of interpretation.

94 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

Subject Selection and Visual Juxtaposition

As suggested by the opening quotation in this article, Brinkley earned great fameamong a portion of her readership—young working women—in part because shechose to include them in her compositions. At times, Brinkley directly addressesher female, working-class readers, identifying herself as one among their ranksand giving them advice on the need to balance work, leisure, and other demandsof modern life. Brinkley’s willingness to portray, appeal to, and empathize with(White) working women likely invigorated this audience. Aside from appearancesin Brinkley’s work, if female wage workers saw themselves depicted in newspaperillustrations of the day, they were likely looking at suffrage illustrations addressedto affluent women who were encouraged to agitate on behalf of their poor sisters(Tickner 174–75). For her broader audiences, Brinkley’s subject selection works rhet-orically to ‘‘establish visibility,’’9 drawing attention to marginalized women whoremained largely ‘‘invisible’’ in dominant culture (Gallagher and Zagacki 177). Thisdemocratic impulse surely captured the attention of many NYEJ readers.

Rather than narrowing her expositions to feature just one woman or one scenefrom a modern woman’s life, Brinkley repeatedly juxtaposes subjects, collocatingwomen of greater and lesser means in the shared space of her pictorial exposition.In fact, Brinkley’s recurrent practice of juxtaposition enables her to bringtogether various subjects: women of differing political leanings, women of differentethnicities, and even incongruous men.10 In this article I have chosen to focus myattention on those compositions that reflect various types of diversity amongmodern women. These compositions reveal Brinkley’s use of her serializedexpositions as an organ for displaying and encouraging reflection upon the diver-sity that she and her early-twentieth-century audiences were likely to experience.This juxtaposition frequently informs the commentary Brinkley includes beneatheach panel, suggesting her interest in stimulating cognitive dissonance withinher readers. Such dissonance is what Kenneth Burke refers to as ‘‘perspective byincongruity’’ (102). Burke values an alteration of perspective that jars one fromher situated position and allows her to ‘‘see’’ from an alternative vantage point;perspective by incongruity results when a stark juxtaposition provokes suchperspectival revisioning. Brinkley’s juxtaposition of women of differing orien-tations, which forces readers to grapple with seemingly incompatible iterationsof womanhood, is an example of perspective by incongruity that indexes women’scomplex and changing roles during the early twentieth century.

In her examination of the feminist activist group the Guerrilla Girls, Demoexplains that the group uses perspective by incongruity to juxtapose ‘‘incongruentideals, values, practices, and symbols’’ to shatter various gender ideology ‘‘pieties’’or conceptual frames of reference (139). The notion of such pieties is theorized byBurke and further explored by Thomas Rosteck and Michael Leff, who argue that‘‘old pieties must fall to provide space for new ones’’ (qtd. in Demo 139). Brinkley’swork employs what Demo calls ‘‘strategic juxtaposition’’ (147) to provide a similarperspective by incongruity that has the potential to shatter early-twentieth-centurypieties related to womanhood. Brinkley’s juxtaposition of subjects calls attentionto their various subject positions and lived experiences, differentiating her work fromher contemporaries, like illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, who typified womanhoodthrough repetition of supposedly ‘‘womanly’’ qualities (such as physical appearanceand dress).

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 95

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

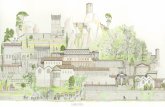

The situational disparities and underlying similarities between working womenand rich women are a trope Brinkley explores through strategic juxtaposition. In‘‘The Tug of War’’ (see Figure 1), six women appear on a hillside, three ‘‘girl[s] ofleisure’’ struggling against three working women, each dressed in shirtwaists. Brinkleyexplains that the latter group represents the ‘‘girl who must toil with brain, or some-times with weary little hands and feet for the clothes that cover her brave shouldersand the butter that goes on her bread.’’ The working women stand high on the hilland look downward, metaphorically suggesting their uphill battle and the forces(e.g., influence, wealth) that, like gravity, work in the rich women’s favor. Brinkleyestablishes the visibility of class struggle by juxtaposing women of means and womenwho need to work, using the visual metaphor of the tug-of-war to collocate thesesubjects within the same panel and playfully introduce the serious theme of economicdisparity. Brinkley encourages audiences to use the panel to question pieties ofwomanhood with her caption, which asks, ‘‘Who wins? Is there any winning? Doesit just depend on the girl? . . . . Which one fills best the definition of the soft wordWoman?’’ With the aid of the juxtaposed image and Brinkley’s questions, readersare encouraged to rely on their own hermeneutic strategies to interpret the work.

A later panel, appearing just two months after the ratification of the NineteenthAmendment granting women the right to vote, speaks to political difference inrelation to suffrage. ‘‘Clothes Don’t Always Make the Woman’’ (see Figure 2)features two incongruous women—one stern, the other stylish—each absorbed in abook as they ride the subway. In addition to the juxtaposition of the appearance ofthe two women, Brinkley’s panel presents another element of surprise, as the stylishwoman reads Essays on Political Economy while her stodgier counterpart consumesYoung Love: A Novel. Brinkley’s message is reinforced by her commentary: ‘‘Judging

Figure 1. ‘‘The Tug of War.’’ Illustration by Nell Brinkley, 1915.

96 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

by appearances is all wrong when you come to what’s behind the cover.’’ ‘‘Clothes’’relies on the audience’s enthymematic notion that suffrage work is for unsexedwomen, while style is the province of women who, for fun or for a chance at upwardmobility, were primarily interested in attracting the attention of men. Young Lovesurely represents one of the glut of dime novels that presented melodramatic fictioncentering on such stock characters as the working-class female heroine (Enstad37–41). Such heroines, all unrealistically ‘‘perfect,’’ nevertheless needed socialacknowledgment of their worth to feel validated (Enstad 70). Thus, the irony ofthe panel heightens the juxtaposition of two stereotypical women: The modernwoman whose presence is seemingly fashioned to draw spectatorship consumesherself with concerns of women’s social equality, while the dowdy moralist plungesherself in a pulpy romance highlighting women’s validation by men.

Brinkley’s juxtaposition within the frame of a comics panel enables rhetoricalplay of space and context, which heightens the potential for dissonance. The juxta-position in ‘‘Clothes’’ is purposeful and contextualized on the subway, a quintessen-tially modern, urban, and democratic space that provides transportation but oftenleads to encounters with the unfamiliar. The panel invites audiences to tease outhow difference functions within a context where one is likely to find it. Alternately,‘‘The Butterfly and the Bee’’ (see Figure 3) juxtaposes figures of the leisure andworking classes within the class-distinct space of the home. In the left panel appearsa lounging woman and her pets. She is draped in lacy gowns and concerned with‘‘her beauty and naught else.’’ Opposite, a woman irons and watches a small child.She ‘‘makes the world go ‘round, washes babies and feeds men,’’ reads the caption.Brinkley’s portrayal of this working woman functions rhetorically to establish thevisibility of women who are primarily defined by their service (largely undervaluedand invisible) to others. The prescribed point of comparison here is the notion of

Figure 2. ‘‘Clothes Don’t Always Make the Woman.’’ Illustration by Nell Brinkley, 1920.

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 97

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

feminine beauty, as Brinkley comments, ‘‘there are those who would say that [theworking woman] is beautiful, too.’’ But this panel visually intensifies the subjectjuxtaposition by situating both women within their respective homes and then con-joining these homes within the split frame. Brinkley invokes gendered notions ofdomesticity with this scene, a move that highlights similarity between the two femalesubjects. The split-frame panel, however, forces audiences to consider how socioeco-nomic status differentiates the experience of the home for women and how women’svarious ways of relating to the space of the home indexes difference. The split frameenables Brinkley to collapse real space to perform a visual-spatial juxtaposition noteasily available in the era of early photography: Audiences can ‘‘peer’’ into twohouses at once. ‘‘Home’’ thus functions simultaneously to equate and differentiatethe women and encourages audiences to interpret the juxtaposition.

Brinkley’s panels disrupt fixed notions of difference by putting women who arenot alike within a tight frame and using context to provoke questions as to how dif-ference is determined. Through strategic juxtaposition, these works call on audiencesto acknowledge difference and grapple with ontological uncertainty. Brinkley com-plicates notions of similarity and difference while appealing to working-class womennot used to seeing themselves so featured in illustration. Brinkley’s subject selectionsuggests that she was cautious of the potential to flatten and ‘‘fix’’ her subjects,rendering them mere caricatures of themselves. By employing strategic juxtaposition,Brinkley foregrounds the differences between and among her subjects, finding avisual-rhetorical strategy for encouraging audiences to recognize and grapple withsometimes invisible, sometimes uncomfortable differences that surrounded them.

Figure 3. ‘‘The Butterfly and the Bee.’’ Illustration by Nell Brinkley, 1917.

98 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

Stylistic Techniques of Inversion

Within many of her panels that juxtapose subjects, Brinkley employs what I call‘‘visual chiasmus,’’ a formal arrangement that deepens the aesthetic appeal of herwork. Chiasmus is a rhetorical scheme of stylistic inversion—a structural reversalthat enhances the meaning of a message (Corbett 478; Fahnestock 123). Brinkley’suse of juxtaposition incorporates inversions that compare and sustain the overallvisual and thematic balance of the composition. For example, in ‘‘The Butterflyand the Bee’’ (Figure 3), Brinkley balances the two halves of the panel but usesinversion and substitution to call special attention to the relationship between thetwo subjects. To complete the inversion of leisure and toil, Brinkley substitutes abirdcage for a clock, a chaise lounge for an ironing board, and a pet bird for a youngchild. Brinkley’s selective substitution marks differences between the women butmaintains visual parallelism.

To complement the visual chiasmus, Brinkley uses mirroring and repetition: Shemirrors the large window in the background of both halves of the panel but repeatsthe dominant lines of the composition. The woman of leisure looks up toward thebirdcage, creating a strong diagonal that extends through her supporting arm;the working woman looks down at her charge, her arms matching this diagonal asshe irons. Playing on the rich woman’s dreamy detachment (hence her upward look)and the poorer woman’s focus on her work (hence her downward look), this linecreates the visual chiasmus that encourages Brinkley’s audience to see thesesubjects—dissimilar in social class, wealth, and (a)vocation—as equally beautiful.Visual chiasmus is also at work in the substitution of book covers in ‘‘Clothes’’(Figure 2) and in the mirroring of subjects in ‘‘The Tug of War’’ (Figure 1).

Chiasmus is a rhetorically powerful form because of its ability to please audi-ences through the playful manipulation of signs. This rhetorical figure, typically usedto describe the inversion of two sentences, phrases, or lines of poetry, does notdepend on signification but rather on the phonetic quality, or in this case the visualform, of the signs. Nevertheless, this play can enable audiences to experiencemeaning in a powerful way that is enhanced by the beauty and balance of the form.Paul de Man praises the rhetorical power of chiasmus, claiming that the form sets‘‘polarities’’ into ‘‘rotating motion’’ (49), a metaphor that alludes to the dynamicquality of this figuration. According to de Man, chiasmus works structurally andaesthetically to cross and conjoin the seemingly incompatible, encouraging audiencesto accept a relationship even if that same relationship would not hold up on the solebasis of signification (Grosholz 427).

Visual chiasmus enables Brinkley to create aesthetically rich texts that visuallybalance representations of socially unequal subjects. The proportional qualities ofthe visual chiasmus panels simultaneously evoke the polarity and the synthesis ofBrinkley’s subjects, ultimately conjoining them in a reader’s perceptual field. Gaugingthe aesthetic quality of art is an aspect of visual rhetoric that can seem too subjectiveor insubstantial to lead to claims of rhetorical efficacy. Visual appeal, however, is aformidable part of the experience of ‘‘reading’’ image texts, and, according to comicsscholar Stuart Medley, a necessary ‘‘visceral’’ condition of understanding audienceperception (68). Similarly, Robert Hariman advocates increased attention to styleas a method for rhetors (in his case, politicians) to evoke aesthetic reactions inaudiences, adding to these speakers’ overall rhetorical success. Specifically, Harimanexamines otherwise ‘‘inexplicable, irrational, or uninteresting’’ political events

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 99

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

through ‘‘aesthetic norms’’ and other seemingly extrarhetorical aspects of such rhe-torical situations (5–6). Defining political style as a ‘‘coherent repertoire of rhetoricalconventions depending on aesthetic reactions for political effect’’ (4), Hariman makesa case for the necessity of exploring the stylistic moves that add to a rhetorician’saesthetic appeal.

Brinkley’s works are not political ‘‘events,’’ but they do represent serializedillustrations of womanhood that showcase her artistry and her attention to thepolitics of women’s shifting relationship to public life and the varied peoples thatcomprise early twentieth-century publics. I surmise that the affective quality ofvisual chiasmus helps explain how Brinkley maintained such wide popular appealwhile creating at least some pictorial expositions that, upon close study, encourageaudiences to critically examine doxa of the day. In short, the heavy rhetorical liftingdone by Brinkley’s panels is downplayed by the beauty of her line work and thesymmetry she exploits in the expositions examined here.

‘‘Refigured’’ Motif

As I have argued, Brinkley’s compositions do not construct a singular message butrather encourage audiences to compare and contrast juxtaposed subjects and tograpple with ensuing observations, associations, and complications. Brinkleyshuttles between the familiar and the unfamiliar in visual depictions of similarityand dissimilarity, encouraging her audiences to identify with her work and reflecton the dissonance it stimulates. This rhetorical approach is more evocative thanhortative and likely helped Brinkley garner wide popularity while affording her anopportunity to visually explore politically and culturally sensitive themes. Brinkley’spenchant for calling on audiences to interpret her work rather than explicating asingular meaning is particularly evident, however, in her use of a Cupid motif.

Most of Brinkley’s line drawings have some sort of woman-centered theme thatspeaks to women’s changing roles and choices as well as their relationship to love.Cupid, the young god of desire who inspires love, appears as a motif relating towomanhood in Brinkley’s line drawings. Here I rely on Olson’s description ofa motif as an image (or emblem and device) that functions as a ‘‘vehicle to explore[an] evolving vision’’ (8). The Cupid motif delivers familiarity while allowingBrinkley to toy with women’s unexpected subject positions. At the same time, theartist’s depiction of Cupid as a plump, curly-haired baby adds to her panels’aesthetic appeal where he serves as yet another winsome Brinkley subject.

Cupid figures into Brinkley’s work as more than a pretty face. He symbolizesromantic love and functions as a recognizable visual anchor. But he also serves asa symbolic expression of the complexity and unexpectedness of women’s changingsocial and familial roles. In one of Brinkley’s panels, Cupid looks into a crystal ballbut is labeled a ‘‘fake clairvoyant.’’ In other pieces, Cupid is similarly unable—orunwilling—to act upon women. ‘‘Clothes’’ (Figure 2) features Cupid sitting betweenthe two subway riders, leaning toward the spinsterish Young Love reader but eyeingthe Political Economy reader closely. Cupid seems to be puzzling over how to ‘‘read’’these women, whose appearances deceive, unsure of how they square with hisheretofore untroubled notion of femininity. His arms open outward; Cupid gesturesto readers to make sense of these perplexing modern women. Elsewhere, Cupidpassively observes the rich and poor tug-of-war, contemplating a competition thatmight not produce one clear winner (Figure 1).

100 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

Brinkley’s use of the motif aligns with other cartoonists’ use of Cupid toemphasize a woman’s role as a wife and mother (Kohler 171), but her reliance onan ambiguous Cupid provides an aperture for audiences to consider women’s chan-ging roles, rather than praise or lament any particular choice—it ‘‘refigures’’ themotif. I borrow this notion of refiguration from Joan Faber McAlister, who arguesthat the practices and processes through which figures are produced (figuration)and purposefully redeployed (refiguration) enable material rhetorical analysis ofverbal, visual, and spatial ‘‘figural operations’’ that have the potential to ‘‘transformlogics, norms, and subjectivities’’ (‘‘Figural Materialism’’ 282). Consider, forexample, Brinkley’s Cupid in comparison to that of Walt Van Arsdale, an illustratorwhose line work is strikingly similar to Brinkley’s. In Van Arsdale’s 1924 ‘‘InadequateProtection,’’ three young women hide behind a snowman as Cupid pursues them,finding a strategy to ‘‘warm’’ their ‘‘frozen’’ hearts and assuring readers that ‘‘asalways, Love laughed last.’’ Van Arsdale’s panel features independent women beingfoiled by a determined Cupid, visually underscoring the gendered belief that awoman’s greatest aspiration should be to secure the affection of a man. Independencehere is trivialized through the depiction of women playing in the snow, and the panelmoralizes to readers, warning them to learn from the foolishness of these headstrongbut overpowered women. Brinkley’s Cupids, in contrast, model the contemplationthat readers might employ in engaging with the indeterminacy of her panels. Withtheir ambiguous presence, Brinkley’s Cupids provide a familiar visual trope thatrhetorically complicates her work, dissuading audiences from resting on one, easyinterpretation.

Stylistic Visual Strategies and Rhetorical Possibility

Attention to the formal and aesthetic qualities of Brinkley’s work not only illuminatesthe rhetorical nature of her compositions (i.e., how audiences might ‘‘read’’ them) butalso suggests how pictorial compositions are uniquely situated to enhance therhetorical possibilities of their composers. For example, just as verbal chiasmus hasa mnemonic quality (many people can easily call to mind poignant examples ofchiasmus, such as President John F. Kennedy’s ‘‘Ask not’’ injunction), visualchiasmus might well serve to enhance the mnemonic quality of a pictorial exposition.The cross and conjoin function of visual chiasmus demands that the artist constructa work so that the visual balance of the piece amplifies its meaning or message.Thus, this doubling of the work’s rhetorical action—both through significationand form—might make the composition particularly memorable to audiences. Theusefulness of visual images as mnemonic tools that ‘‘trigger’’ and extend humanmemory is part of the world’s rhetorical tradition and has particular use inindigenous communities, reminds Franny Howes (40). Thus, from a rhetoricalperspective, visual compositions—particularly those that employ chiasmus—havethe potential to activate audiences’ visual memory and increase the likelihood of laterrecall. Might Brinkley’s urban readers recall ‘‘Clothes’’ when riding on the subway?And could such recall shape their experience in that space? Although answeringthese questions is impossible, the mnemonic potential of Brinkley’s work suggestsa capacity to visually ‘‘re-function our memories and imaginations’’ (Mitchell, qtd.in Demo, ‘‘Sovereignty’’ 297).

More fundamentally, pictorial expositions enabled Brinkley to place thought-provoking, potentially subversive texts in front of newspaper readers’ eyes on a

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 101

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

regular basis. As the history of women’s rhetorics has taught, nineteenth- andtwentieth-century women who sought a platform for affecting political and socialchange struggled mightily to enact their power as rhetors in male-controlled publicforums (Campbell). To respond to the barriers they met when attempting to com-municate on their own behalf, some women created opportunities and apparatuses(e.g., the suffrage press) for sharing their positions and galvanizing support(Solomon). Although I do not read an overt persuasive message into Brinkley’scompositions, I maintain that her work is clearly interested in challenging fixednotions of womanhood and femininity. Without assigning intent, one can appreciatehow Brinkley’s medium—feminized, low-brow illustration—gave her access to amajor publication and the opportunity to create rhetorically rich compositions thatfrequently reflected on the vexing concept of ‘‘modern’’ womanhood. Throughvisual means, Brinkley enabled dissonance, providing an opportunity for audiencesto further complicate, even destabilize, gendered assumptions that were being calledinto question in popular and political realms.

The Looking Subject

Stylistic visual strategies encourage Brinkley’s audiences to play with the category‘‘woman,’’ but her work also generates a graphic meta-discourse on the politics ofvisuality and looking that prompts a revisioning of ‘‘woman’s’’ agential capacity.Brinkley’s panels frequently depict modern women doing modern activities: work-ing, occupying public spaces, physically exerting themselves. But in addition, theyalso feature women looking at one another—gazing at, contemplating, and seem-ingly assessing their own notions of gender identity. Brinkley’s compositions positionwomen as looking subjects and visually construct looking as a subjective act withethical implications. Brinkley shifts her subjects from their looked-upon positions,visually and symbolically rupturing what has since been identified as a gaze of objec-tification and homogenization upheld by masculinist logics (Berger 36–64; Mulvey;McAlister, ‘‘Collecting’’ 4). Within Brinkley’s panels women look at one anothermeaningfully and questioningly, and the act of looking emerges as an additionalsubject worthy of contemplation. In this way, Brinkley’s work can be appreciatedfor encouraging readers to identify and situate themselves within the genderedpolitics of visuality.

To understand the significance of Brinkley’s meta-discourse on looking, it ishelpful to consider the complex ways that visuality was shaping modern women’sexperiences during her lifetime. The New Woman, the flapper, and the consumerare three historical iterations of modern womanhood that relate directly to visualityand the gendered politics of looking. The ‘‘New Woman,’’ iconically renderedby Charles Dana Gibson, describes young women of the late nineteenth and earlytwentieth centuries who explored new levels and methods of independence andself-expression. The capacious term, according to historian Martha H. Patterson,signifies ‘‘a character type, a set of distinct goals, and a cultural phenomenon’’and describes ‘‘a distinctly modern ideal of self-refashioning’’ (2). Gibson’s pictorialtake on the type solidified the New Woman in the nation’s imagination. In makingher visible, his illustrations also made her accessible and easy to duplicate. Recogniz-able by their tall, thin, Anglo-American look and their supposed freedom of move-ment, Gibson Girls frequently appear on a bicycle, at the beach, or with golf club inhand—although they remain statuesque and composed, never truly in motion. Aloof

102 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

and independent, yet romantic, Gibson Girls were vanguards of fashion andmodernity from the early 1890s through World War I (Croce).

The Gibson Girl seemed to embody women’s changing status; nevertheless, shewould ultimately remain the object of male scrutiny and a homogeneous, relativelyunattainable representation of ideal womanhood. An image of perfection andself-control, the Gibson Girl helps explain the allure of New Womanhood at a timewhen the political and social status of women was so contested. As Gibson’s creation,the New Woman was apolitical, alluring, and consumable. ‘‘[N]ot a thinker oractivist, nor even sexually provocative,’’ writes comics scholar Alice Sheppard, theGibson Girl was ‘‘male fantasy, being eternally young, beautiful, and unobtainable—the perfect image to adorn the pedestal’’ (63).

Gibson Girls, like other ‘‘girl’’ types produced by illustrators such as HowardChandler Christy, Harry McVickar, Harrison Fisher, and Joseph ChristianLeyendecker, flirt with the notion of modernity but ultimately fail to break free fromtheir position as looked-upon objects. Just as these New Women were named fortheir male creators, they remain situated within a legacy of Western culture wherebywomen function primarily to be the object of a male gaze. Art historian John Bergerpoignantly suggests the pervasiveness of this visual epistemology through his surveyof Western art, which collectively, over centuries, has reinforced and normalized thisunequal distribution of visual power. ‘‘[M]en act and women appear. Men look atwomen. Women watch themselves being looked at’’ (Berger 47).

Reacting to this visual objectification, some women of the early twentiethcentury, dubbed ‘‘flappers,’’ experimented with finding agency from within the gaze.In the post–World War I era, ‘‘flapper’’ described an emerging subculture of womenwhose methods of self-expression were based on strategies of being seen: bobbingtheir hair, hemming dresses above rouged knees, binding their breasts, and dancingthe Harlem-based Charleston (Sagert 2, 111). By actively vying for attention,flappers resisted succumbing to the male gaze while still remaining complicit in itspower. Historian Liz Conor explains that a flapper ‘‘was not prepared to enter theperceptual field as a mere spectator. She wanted to dominate the scene and controlthe anonymous play of looks within it’’ (232). For such women, visuality functionedas a way to experiment with self-display in order to be seen by others.

Regardless of their interest or intent, many modern women had yet anotherdeveloping relationship to visuality. Women were increasingly interpellated as con-suming subjects, encouraged to look as a market-driven activity, an act of longingand desire. The Gibson Girl was one such catalyst for budding female-consumer-directed visual appeals. West contends that no matter what activity she was pictureddoing, the Gibson Girl always communicated to women viewers that ‘‘by consuminggoods one could produce a better self’’ and that discernment— cultivated in large partthrough visual means—was a requisite skill needed to achieve this goal (120–21). Thealoofness of the Gibson Girl is what marked her as glamorous. Her desire to be‘‘observed with interest,’’ but her unwillingness to ‘‘observe with interest,’’ producedan ‘‘illusion’’ of power (Berger 133). As the most self-directed form of visualexperimentation of this time, consumer-driven practices of seeing were a chimera ofpower tethered to the whims of capitalism and the constraints of capital markets.

The appearance of the glamorous and envied woman, the experimentation of theflapper, and the affected, conspicuous consumption11 of the consumer: All of theseorientations to visuality failed to help women assume control over the act of looking,much less recognize it as a potential source of power. Women’s modernization

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 103

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

during the early twentieth century, however, rested largely on feminine visibility’srelationship to agency, for, as Conor explains, the ‘‘dramatic shift from incitingmodesty to inciting display, from self-effacement to self-articulation, is the pointwhere feminine visibility began to be productive of women’s modern subjectivities’’(29). Enabling the subjective experience of looking, then, could be one of Brinkley’smost significant contributions to the visual rhetoric of graphic art during her time.

Brinkley used her expositions to reflect on women’s potential as lookingsubjects, portraying them exercising their power to look, categorize, and classify,and providing graphic scripts for how to practice such looking. Brinkley’s 1924‘‘Rich Girl, Poor Girl’’ (see Figure 4) can be viewed as one such study in looking.Two sisters face each other on a bench, one dressed simply and surrounded by twochildren, the other donning a fur and jewels. Their direct gaze into each other’seyes intensifies the paradox of similarity and contrast and accentuates Brinkley’scommentary, which explains that the affluent woman secretly longs for thehappiness—the richness of spirit—that her more modest sister enjoys. The sistersboth display, however differently, evidence of their womanliness. Their juxtapo-sition calls attention to one gendered challenge for modern women: assessingthe affordances and limitations of being able to take greater control over one’srelationship to domesticity and motherhood. Audiences are drawn to the central‘‘action’’ in the panel, the sisters’ mutual gaze, by the symmetry of their turnedfaces and the invisible line of sight that they share. Thus, the subject of theexposition becomes this silent, uninterrupted act of looking, which encouragesaudiences to move beyond ‘‘reading’’ the women themselves as objects of inter-pretation. Visually, the piece communicates the intensity of looking and enablesaudiences to experientially practice looking in a new way.

Figure 4. ‘‘Rich Girl, Poor Girl.’’ Illustration by Nell Brinkley, 1924.

104 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

Brinkley’s 1915 ‘‘My, But You’re Funny’’ also depicts women looking at oneanother and suggests that looking has limited, sometimes faulty, epistemologicalpotential. The panel features a young, White New Yorker (a ‘‘perfect little nineteen-fifteen maiden’’) scrutinizing a group of women, each from various parts of the world.In the caption, Brinkley recounts observing a woman on the subway making ‘‘hiddenfun’’ of another ‘‘plain little person’’ on the train. Brinkley ‘‘watched and found apicture in it all,’’ leveraging the anecdote to pictorially capture her meditation on dif-ference and visual judgment. In the exposition, Brinkley troubles the objectifying gazeon the basis of ethnic difference instead of beauty alone. Significantly, Brinkley depictsthe women looking at one another, portraying each of them as looking subjects insteadof exoticized objects. In her caption, Brinkley emphasizes the reciprocal nature of thisexchange, suggesting that these women of the world likely find the flapper ‘‘funny’’with her furs, ‘‘debutante slouch,’’ and ‘‘tripping walk.’’ Although Brinkley’s depictionof various ethnicities (e.g., ‘‘Esquimo,’’ ‘‘Araby,’’ ‘‘Chinee’’) is problematically exoti-cizing in its own right, the panel’s overall message invites the young, White woman toquestion the universality of her perspective. It ruptures centric thinking both themati-cally and pictorially; the flapper, in this moment not the center of attention, looks atthe other women from the far left of the panel. As is the case in ‘‘Clothes’’ (Figure 2)and ‘‘Rich Girl, Poor Girl’’ (Figure 4), this panel suggests the potential inaccuracyof visual perceptions and the implications of relying too heavily upon an ocular-centricepistemology.

Brinkley’s work presents women who actively explore the potential and thelimitations of their own capacity to look and to know through looking, suggestingthat women could be modern because of their visual agency, not merely because theypushed boundaries of gendered space, dress, and comportment. Given the historicalmoment, this meta-commentary on visuality represents an unusual opportunity forwomen to reflect on their own subject positions.

Modeling woman-as-viewer is especially significant because, as Conor argues,‘‘the reading of women-objects as pleasing heterosexual spectacles seemed to confirmthat the woman-object was the opposite of the modern subject, who looked and whowas male’’ (30; emphasis added).

Always already looked upon, modern women had few, if any, models that helpedthem think critically about the politics of looking. Even the Kodak girl, a marketingcreation that encouraged women to buy Kodak cameras and fashion themselves asphotographers, largely ignored the latter. While Kodak males were pictured takingphotographs, the Kodak girl was frequently pictured gazing at her camera, enjoyingit as a commodity rather than a tool; this arrangement reified women’s function asconsumers, not compositionists (West 121). The most prominent message relatedto female sight, then, was that it should be used as an aid for consumption and theendless process of cultivating the self as desirable and desired.

Brinkley’s panels model women’s active looking, delivering graphic scripts ofthis action and engaging readers who participate in this looking as they read herwork. Experiential practice might have aided female readers in recognizing them-selves as the looking subjects depicted in Brinkley’s panels. Feminist film theoristLaura Mulvey’s foundational scholarship on scopophilia (the desire to look atanother person ‘‘as an erotic object’’) and the process by which individuals can breakout of this object position makes clear that images, in particular, can aid in theprocess of self-recognition (10). Similar to Jacque Lacan’s explanation that egodevelopment begins with a child’s recognition of her image in a mirror, Mulvey

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 105

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

contends that filmic images have ‘‘structures of fascination strong enough to allowtemporary loss of ego while simultaneously reinforcing the ego’’ (10). Brinkley’snonmoving images supply their own ‘‘structures of fascination,’’ in part, throughtheir visual complexity, fine detail, and overall aesthetic quality.12

From the tip of Brinkley’s pen came women—different types of women—whowere looking at one another and puzzling over what they saw. The effect of thisemphasis on the looking subject cannot be measured, but the potential for these sub-jects to provide graphic scripts for readers to engage and emulate is noteworthy. ErinJ. Rand articulates the rhetorical implications of visibility politics, a set of dynamicsthat provoke scholars to ask ‘‘under what conditions, on whose terms, for whosebenefit, and at whose expense certain bodies can become visible’’ (137). Brinkley’suse of the looking subject encourages rhetoricians to ask similar questions of visualpolitics and gender: Under what conditions, with what provocation, and to whatpotential effect might women or others who have been aesthetic objects of a gaze,begin to look back?

Conclusion

Feminist art historian Whitney Chadwick explains that despite ubiquitous visualrepresentations of modern womanhood, the ‘‘image that promised a new worldfor the modern woman in twentieth-century industrial society would exist as a realityonly for wealthy and privileged women.’’ For working women, such imagery ‘‘func-tioned more and more as a fantasy, remote from the realities of most women’s lives’’(278). As a ‘‘mere’’ illustrator of women’s comics, Brinkley produces work thatseems playful and unthreatening despite its provocative themes, its visually complexrhetorical techniques, and its relevance to the lived realities of many women of herday. Brinkley’s sustained focus on the looking subject, along with her reliance onsophisticated stylistic visual strategies, points to her work’s ability to invite cognitivedissonance, skepticism of the accuracy of visual epistemology, and an awareness ofthe gendered politics of looking.

Initiating a shift in perceptions of identity surely ranks among the mostformidable of rhetorical challenges. During Brinkley’s time, women artists faced whatLisa Tickner describes as ‘‘powerlessness in the production of social meaningsrelated to the roles of artists and of women’’ (13–14). Since the early twentiethcentury, women have made more explicit attempts to redefine their identity, facingresistance and backlash in the process. For example, second-wave, lesbian feminists’‘‘Woman-Identified-Woman’’ position, according to Kristan Poirot, ‘‘attemptednothing short of constituting a new notion of woman as well as a new space for womento exist, a structural alternative’’ (276). Investigating how this woman-identifiedidentity relied on containment rhetorics to demarcate difference and identityboundaries, Poirot suggests that a more effective alternative could be to broachidentity with a ‘‘more open orientation to future possibilities’’ instead of delineatingdifference (286). In light of this suggestion, the merits of Brinkley’s invitational,13

nondirective, visual approach become increasingly apparent.My selection of newspaper panels for this analysis discourages reading Brinkley

as a protofeminist, a label that flattens her nuanced responses to complex andchanging exigencies. ‘‘Rich Girl, Poor Girl’’ (Figure 4), for example, engages withthe gains and losses of women making traditional and nontraditional life choices,displaying sentimentality toward motherhood and sacrifice, while also portraying

106 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

independence as viable pursuit for some women. What I do suggest, however, isthat Brinkley’s visual compositions are engaging, not didactic, and her ambiguousheuristic scripts allow for varying interpretations. Many analytical apparatuses invisual rhetorical studies encourage scholars to unearth the argument of a pictorialtext. This examination of Brinkley’s work questions that very impulse andconsiders the invitational potential of visual rhetoric by exploring how its playof form and content open apertures for contemplation as well as persuasion. Manybenefits might result from mindfully adopting feminist methods of visual analysisthat can examine the rhetorical nature of a visual text’s content and design whileexploring how texts shape our ways of seeing or potentially alter gendered politicsof visuality.

Brinkley’s work, appearing on pulpy newsprint, has largely disintegrated frompublic memory. Nevertheless, her rhetorical and artistic talent suggests that hercontributions to a time of significant social and political change for many womenshould no longer go unnoticed.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank editor Joan Faber McAlister, Anne Demo, ananonymous reviewer, Cheryl Glenn, Michelle Smith, and Ersula Ore for giving valu-able feedback during various stages of this project’s development. A previous versionof this manuscript was presented at the Rhetoric Society of America conference.

Notes

1. Comics scholar Robert C. Harvey describes pictorial expositions as hybrid verbal andvisual texts that need not be sequential. Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics remainsthe germinal text in the study of comics, despite McCloud’s emphasis on comics’ sequenti-ality. I prefer to use Harvey’s terminology because it accounts for single-panel art, whichhas a long history and might serve as an antecedent to contemporary graphic works intheir many forms.

2. I borrow these two areas of focus from Foss’s ‘‘Theory of Visual Rhetoric.’’3. As I will discuss in greater detail, my use of ‘‘refigured’’ relies on Joan Faber McAlister’s

discussion of figuration and refiguration in ‘‘Figural Materialism: Renovating MarriageThrough the American Family Home.’’

4. The University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center provides an overview ofHearst’s Journal newspapers in its New York Journal–American Photographic MorgueWeb site (http://norman.hrc.utexas.edu/nyjadc/).

5. Circulation figures were sometimes included on the newspaper’s masthead. For example,the circulation on June 9, 1915, was 854,858. And according to historian Kenneth Whyte,by the late 1920s one in four Americans were thought to have gotten their news fromHearst publications (464).

6. Comics artist and writer Trina Robbins and independent historians Loise E. Collins andTom J. Collins have been largely responsible for preserving Brinkley’s work.

7. Robbins’s Nell Brinkley and the New Woman in the Early 20th Century is an exception tothis claim, as it features reproductions of a selection of Brinkley’s line drawings. To findBrinkley’s work, I searched available microfilmed copies of the New York Evening Journal.Some issues are missing and many are damaged, likely due to the high acidity and lowdurability of newsprint.

8. These microfilmed issues of the New York Evening Journal are available at the New YorkPublic Library.

9. Victoria Gallagher and Kenneth S. Zagacki use the term establish visibility to explain anartist’s ability to ‘‘make visible people, attitudes, and ideas’’ in their analysis of NormanRockwell’s civil rights paintings. Their analysis suggests that images that establish

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 107

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

visibility are rhetorical in their ability to ‘‘invoke self-awareness about the conscious livedexperience of the other’’ (182).

10. For example, another one of Brinkley’s illustrations from 1915 depicts a woman flankedby two fawning men—a rich serenader with a bag of gold and a poor man with only hisheart to give.

11. Here I refer to Thorstein Veblen’s idea of spending money to display one’s wealth and beseen as wealthy (49–69).

12. It is also worth acknowledging that Brinkley calls upon audiences experientially in muchthe same way that Berger later does in his influential Ways of Seeing, a collection of essaysthat includes some solely pictorial compositions.

13. My use of the term invitational is based on Sonja K. Foss and Cindy L. Griffin’s conceptof invitational rhetoric. Foss and Griffin suggest that rhetoric can be understood as ‘‘aninvitation to understanding’’ that cultivates ‘‘relationship[s] rooted in equality, immanentvalue, and self-determination’’ in addition to more competitive and exclusionary notionsof persuasion (5).

Works Cited

Bates, Benjamin R., Windy Y. Lawrence, and Mark Cervenka. ‘‘Redrawing Afrocentrism:Visual Nommo in George H. Ben Johnson’s Editorial Cartoons.’’ Howard Journal ofCommunications 19 (2008): 277–96. Communication and Mass Media Complete. Web. 1May 2012.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, 1972. Print.Brinkley, Nell. ‘‘The Butterfly and the Bee.’’ Cartoon. New York Evening Journal 17 Feb.

1917: 16. Microfilm. New York City Library private collection.———. ‘‘Clothes Don’t Always Make the Woman.’’ Cartoon. New York Evening Journal 23

Oct. 1920, Magazine sec. Microfilm. New York City Library private collection.———. ‘‘My, But You’re Funny.’’ Cartoon. New York Evening Journal 30 Jan. 1915: 10.

Microfilm. New York City Library private collection.———. ‘‘Rich Girl, Poor Girl.’’ Cartoon. New York Evening Journal 12 June 1924: 10.

Microfilm. New York City Library private collection.———. ‘‘The Tug of War.’’ Cartoon. New York Evening Journal 16 July 1915: 14. Microfilm.

New York City Library private collection.Burke, Kenneth. Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose. 3rd ed. Berkeley: U of

California P, 1954. Print.Campbell, Karlyn Kohrs. Man Cannot Speak for Her. 2 vols. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1989.

Print.Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. 5th ed. New York: Thames, 2012. Print.Chute, Hillary L. Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York:

Columbia UP, 2010. Print.Conor, Liz. The Spectacular Modern Woman: Feminine Visibility in the 1920s. Bloomington:

Indiana UP, 2004. Print.Corbett, Edward P. J. Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford

UP, 1971. Print.Croce, Ann Jerome. ‘‘Gibson Girl.’’ Encyclopedia of American Studies. Ed. Simon J. Bronner.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2012. Web. 6 Feb. 2012.de Man, Paul. Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and

Proust. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979. Print.Demo, Anne Teresa. ‘‘The Guerrilla Girls’ Comic Politics of Subversion.’’ Women’s Studies in

Communication 23.2 (2000): 133–57. Communication and Mass Media Complete. Web. 3Feb. 2012.

———. ‘‘Sovereignty Discourse and Contemporary Immigration Politics.’’ Quarterly Journalof Speech 91.3 (2005): 291–311. Communication and Mass Media Complete. Web. 5Aug. 2013.

108 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

Edwards, Janis L., and Carol K. Winkler. ‘‘Representative Form and the Visual Ideograph:The Iwo Jima Image in Editorial Cartoons.’’ Quarterly Journal of Speech 83 (1997):289–310. Communication and Mass Media Complete. Web. 1 May 2012.

Enstad, Nan. Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: WorkingWomen, Popular Culture, and LaborPolitics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Columbia UP, 1999. Print.

Fahnestock, Jeanne. Rhetorical Figures in Science. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.Flukinger, Roy. ‘‘History.’’ New York Journal–American Photographic Morgue. Harry

Ransom Center. n.d. Web. 12 May 2013.Foss, Sonja K. ‘‘Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party: Empowering Women’s Voice in Visual

Art.’’ Women Communicating: Studies of Women’s Talk. Ed. Barbara, Bate and AnitaTaylor. Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1988. 9–26. Print.

———. ‘‘Theory of Visual Rhetoric.’’ Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods,and Media. Ed. Ken Smith, Sandra Moriarty, Gretchen Barbatsis, and Keith Kenney.Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2005. 141–52. Print.

Foss, Sonja K., and Cindy L. Griffin. ‘‘Beyond Persuasion: A Proposal for an InvitationalRhetoric.’’ Communication Monographs 62 (1995): 2–18. Communication and Mass MediaComplete. Web. 10 April 2011.

Gallagher, Victoria, and Kenneth S. Zagacki. ‘‘Visibility and Rhetoric: The Power of VisualImages in Norman Rockwell’s Depictions of Civil Rights.’’ Quarterly Journal of Speech91.2 (2005): 175–200. Communication and Mass Media Complete. Web. 5 Aug. 2013.

Glenn, Cheryl.Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2004. Print.Grosholz, Emily. ‘‘Angels, Language, and the Imagination: A Reconsideration of Rilke’s

Poetry.’’ Hudson Review 35.3 (1982): 419–38. JSTOR. Web. 20 Aug. 2013.Hariman, Robert. Political Style: The Artistry of Power. Chicago: U of Chicago P,

1995. Print.Harvey, Robert C. ‘‘How Comics Came to Be: Through the Juncture of Word and Image from

Magazine Gage Cartoons to Newspaper Strips, Tools for Critical Appreciation Plus RareSeldom Witnessed Historical Facts.’’ A Comics Studies Reader. Ed. Jeet Heer and KentWorcester. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2009. 25–45. Print.

Hesford, Wendy S. Spectacular Rhetorics: Human Rights Visions, Recognitions, Feminisms.Durham: Duke UP, 2011. Print.

Howes, Franny. ‘‘Imagining a Multiplicity of Visual Rhetorical Traditions: Comics LessonsFrom Rhetoric Histories.’’ ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies 5.3 (2010): n.p.Web. 11 Aug. 2013.

Kohler, Angelika. ‘‘Charged With Ambiguity: The Image of the New Woman in AmericanCartoons.’’ New Woman Hybridities: Femininity, Feminism, and International ConsumerCulture, 1880–1930. Ed. Ann Heilmann and Margaret Beetham. London: Routledge,2004. 158–78. Print.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and Adam Rosenblatt. ‘‘ ‘Down a Road and Into an Awful Silence’:Graphic Listening in Joe Sacco’s Comics Journalism.’’ Silence and Listening as RhetoricalArts. Ed. Cheryl Glenn and Krista Ratcliffe. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2011.130–46. Print.

McAlister, Joan Faber. ‘‘Collecting the Gaze: Memory, Agency, and Kinship in the Women’sJail Museum, Johannesburg.’’ Women’s Studies in Communication 36.1 (2013): 1–27.Web. 10 Aug. 2013.

———. ‘‘Figural Materialism: Renovating Marriage Through the American Family Home.’’Southern Communication Journal 76.4 (2011): 279–304. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.Print.

Medley, Stuart. ‘‘Discerning Pictures: How We Look at and Understand Images in Comics.’’Studies in Comics 1.1 (2010): 53–70. IngentaConnect. Web. 24 Aug. 2013.

Messaris, Paul. ‘‘What’s Visual About ‘Visual Rhetoric’?’’ Quarterly Journal of Speech 95.2(2009): 210–23. Communication and Mass Media Complete. Web. 11 Aug. 2013.

Visual Style and the Looking Subject 109

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4

Micciche, Laura R. ‘‘Seeing and Reading Incest: A Study of Debbie Drechsler’s Daddy’sGirl.’’ Rhetoric Review 23.1 (2004): 5–20. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Mulvey, Laura. ‘‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.’’ Screen 16.3 (1975): 6–18. OxfordJournals Archive. Web. 11 Aug. 2013.

New York Evening Journal. What’s in the New York Evening Journal: America’s GreatestEvening Newspaper. 1928. Project Gutenburg. Web. 3 June 2012.

Olson, Lester C. Benjamin Franklin’s Vision of American Community: A Study in RhetoricalIconology. Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 2004. Print.

Palczewski, Catherine H. ‘‘The Male Madonna and the Feminine Uncle Sam: VisualArgument, Icons, and Ideographs in 1909 Anti-Woman Suffrage Postcards.’’ QuarterlyJournal of Speech 91.4 (2005): 365–94. Communication and Mass Media Complete.Web. 1 May 2012.

Patterson, Martha H., ed. The American New Woman Revisited: A Reader, 1894–1930. NewBrunswick: Rutgers UP, 2008. Print.

Poirot, Kristan. ‘‘Domesticating the Liberated Woman: Containment Rhetorics of SecondWave Radical=Lesbian Feminism.’’ Women’s Studies in Communication 32.3 (2009):263–92. Web. 11 Aug. 2013.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity, and Histories of Art. 1988.London: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Ramsey, E. Michele. ‘‘Inventing Citizens During World War I: Suffrage Cartoons in TheWoman Citizen.’’ Western Journal of Communication 64.2 (2000): 113–47. Communicationand Mass Media Complete. Web. 1 May 2012.

Rand, Erin J. ‘‘An Appetite for Activism: The Lesbian Avengers and the Queer Politics ofVisibility.’’ Women’s Studies in Communication 36.2 (2013): 121–41. Taylor and Francis.Web. 11 Aug. 2013.

Robbins, Trina, ed. The Brinkley Girls: The Best of Nell Brinkley’s Cartoons from 1913–1940.Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2009. Print.

———. Nell Brinkley and the New Woman in the Early 20th Century. Jefferson: McFarland,2001. Print.

Sagert, Kelly Boyer. Flappers: A Guide to an American Subculture. Santa Barbara:Greenwood, 2010. Print.

Sheppard, Alice. Cartooning for Suffrage. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1993. Print.Solomon, Martha. A Voice of Their Own: The Woman Suffrage Press, 1849–1914. Tuscaloosa:

U of Alabama P, 1991. Print.Tickner, Lisa. The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–14. Chicago:

U of Chicago P, 1988. Print.Tonn, Mary Boor. ‘‘ ‘From the Eye to the Soul’: Industrial Labor’s Mary Harris ‘Mother’

Jones and the Rhetorics of Display.’’ Rhetoric Society Quarterly 41.3 (2011): 231–49.Print.

Turner, Kathleen J. ‘‘Comic Strips: A Rhetorical Perspective.’’ Central States Speech Journal28 (1977): 24–35. Print.

Van Arsdale, Walt. ‘‘Inadequate Protection.’’ Cartoon. New York Evening Journal 8 Jan. 1924:32. Microfilm. New York City Library private collection.

Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class. 1899. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. Print.Vinson, Jenna. ‘‘Covering National Concerns about Teenage Pregnancy: A Visual Rhetorical

Analysis of Gender and Race in Images of the Pregnant Teenage Body.’’ Feminist Forma-tions 24.4 (2012): 140–62. Print.

Waldrep, Mary Carolyn, ed. By a Woman’s Hand: Illustrators of the Golden Age. Mineola,NY: Dover, 2010. Print.

West, Nancy Martha. Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 2000.Print.

Whyte, Kenneth. The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst.Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2009. Print.

110 H. B. Adams

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UA

A/A

PU C

onso

rtiu

m L

ibra

ry]

at 1

7:27

12

Febr

uary

201

4