van vleck constitutional law moot court competition

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of van vleck constitutional law moot court competition

VAN VLECK CONSTITUTIONAL LAW MOOT COURT COMPETITION

2016-2017

BENCH MEMORANDUM

Final Round

January 25, 2017

Mariel Murphy, Chair

Bud Davis and Jordan Hess, Vice Co-Chairs

2016-2017 Van Vleck Competition Committee

THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL

2

INTRODUCTORY GUIDELINES

The issues, ideas, and suggestions presented herein are those of the competition problem’s student authors. Please feel free to question competitors based upon your own experience, knowledge of the law, and analysis, and to explore ideas not expressly addressed in the opinion below or in this memorandum. Additionally, while there is some overlap between the two issues in this competition problem, competitors have focused on their own issue and may be unable or even unwilling to argue their partner’s issue. If there is overlap and competitors are able to address their partner’s issue, feel free to reward them for that ability; however, please do not penalize students who are unable to do so. Also, please be aware that the competitors have had a very short amount of time to review and “respond” to their opponents’ brief. Accordingly, there may not be perfect agreement between the arguments made in the Petitioners’ and Respondents’ briefs that you have been assigned. Competitors should not lose points for this; however, they should be able to respond to any of their opponent’s arguments during oral argument, regardless of whether they raised the argument in their own brief. Finally, a list of suggested questions is appended to the memorandum. Judges should feel free to ask questions directly from the list or use the list as a starting point for formulating their own questions. The suggested questions are not meant to represent the range of questions permitted. We have prepared an Appendix to help you familiarize yourself with the facts of the case. First, we have provided a “screenshot” of the New Columbia Property Database. Competitors have been provided an identical copy in their competition packets. Second, to assist you with organizing the facts of the case, a timeline for each petitioner has been produced in the Appendix, showing how the state has complied with the various requirements of the law. Third, we have included a recent amicus brief filed in the U.S. Supreme Court to provide some relevant background on escheat law, which is the subject of the competition problem. If you have any questions or concerns regarding the competition problem or this bench memorandum, please do not hesitate to contact us. On behalf of the competitors, thank you for agreeing to serve as a judge. We look forward to a great competition! Sincerely, Mariel Murphy, Chair [email protected] Bud Davis, Co-Vice Chair Co-Author of Competition Problem [email protected] Jordan Hess, Co-Vice Chair Co-Author of Competition Problem [email protected]

1

CASE SUMMARY A. Purpose of the New Columbia Unclaimed Property Act of 2010 In 2010, the New Columbia Legislature enacted the New Columbia Unclaimed Property Act (“the Act”). The Act revised New Columbia’s “antiquated” escheat program by shortening dormancy periods from twenty to three years and by reaching new types of property, including small savings accounts and the contents of safe deposit boxes. After the three-year period expires, New Columbia obtains ownership of the property, and property owners cannot have their property returned. In doing so, the Legislature intends to generate revenue more expediently to reduce the state deficit. The Controller of New Columbia, respondent Elizabeth Thornberry, executes the Act and oversees the escheat program. That same year, the Legislature also enacted the New Columbia Adverse Possession Act, which reduced the limitations period to bring action against the adverse possessor from twenty to seven years, effective January 1, 2012. Although related to the disposition of unclaimed property, this Act has no bearing on the issues before the Supreme Court. It may, however, serve as a useful point of comparison in crafting competitors’ arguments. B. Procedural Requirements Regarding Savings Accounts The New Columbia Unclaimed Property Act imposes similar procedural requirements on the escheat of savings accounts and safe deposit boxes. Regarding savings accounts, the balance of any savings account is deemed “abandoned” if, during the prior calendar year, the owner makes no deposit or withdrawal. The bank must send written notice in January to the owner once the bank determines a savings account is unclaimed. The owner then has 30 days from the date of notice to “activate” the account by making a deposit or withdrawal. If no such transaction is made, the one-year “holding” period commences after which the bank transfers the balance, including any interest, to the State. The bank is not required to send additional notice to the owner when it transfers the balance. However, the bank must report to the Controller its efforts to notify the owner. Upon receipt, New Columbia sends written notice via certified mail to the owner. The notice states that if the owner does not file a claim with the Controller demonstrating proof of ownership within two years, the balance will permanently escheat to the State. At that time, the owner can no longer file a claim. Additionally, New Columbia must list the property as either “greater than” or “less than” $1,000 on the New Columbia Property Database (“the Website”) once it receives the balance and provide the owner’s name, last known address, and the name of the bank. (See Appendix, Figure 1, for sample screenshot of the Website). Lastly, New Columbia is free to use the balance during the two-year custodial period without liability to the owner. The Act further provides that owners are not entitled to any interest which may accrue on an interest-bearing account held by the State. C. Procedural Requirements Regarding Safe Deposit Boxes Regarding safe deposit boxes, the contents of any safe deposit box is deemed “abandoned” if the owner both fails to pay the annual lease fee to the bank and fails to access the box during the prior calendar year. The bank must send written notice to the owner once the bank determines a safe deposit box is unclaimed. The owner then has 30 days from the date of notice to “claim” the box

2

by paying the lease fee. If payment is not received, the one-year “holding” period commences after which the bank may access the safe deposit box at New Columbia’s expense and transfer any contents to the State. The bank is not required to send additional notice to the owner when it transfers the contents. However, the bank must report to the Controller its efforts to notify the owner. Upon receipt, New Columbia sends written notice via certified mail to the owner. The notice states that if the owner does not file a claim with the Controller demonstrating proof of ownership within two years, the property will permanently escheat to the State. At such point, the owner can no longer file a claim, and the State can dispose of the property as it chooses. Additionally, New Columbia must list the property as either “greater than” or “less than” $1,000 on the Website once and provide the owner’s name, last known address, and the name of the bank. The Act imposes an additional requirement on the Controller if the State appraises the property at over $10,000: the State must sell the property at public auction. Before the State can do so, the Controller must ensure the Website indicates that the property will be sold at public auction, although the Act does not require the State to provide further details. The Act also does not require that the State send additional, individualized notice to the owner. However, the State must provide notice in a widely circulated publication 90 days prior to the auction and 30 days prior to the expiration of the two-year custodial period. Once property is sold, the funds are placed in an escrow account for 60 days, after which time the State delivers the property to the new owner, and the State may dispose of the funds as it chooses. Lastly, if the property is valued at less than $10,000, the State may dispose of the property prior to the expiration of the two-year custodial period as it sees fit without liability to the owner. D. Facts Regarding Petitioner Susan Carmichael • Petitioner Susan Carmichael is eighty-nine years old and has long maintained a safe deposit

box at Goliath State Bank. The box has always contained what Ms. Carmichael believed to be an imitation Faberge Egg. In reality, the Egg is a genuine Romanoff Imperial Faberge Egg and is worth millions of dollars.

• On January 10, 1983, Ms. Carmichael opened the safe deposit box account with Goliath State

Bank and immediately placed her Faberge egg into the box. Rent for the box is due annually by January 1st.

• On December 1, 2011, Goliath sent Ms. Carmichael a notice via regular mail informing her

that her safe deposit box rent was soon due. This “courtesy” notice is not statutorily required, but Goliath chooses to send these types of notices anyway. Despite the bank’s letter, Ms. Carmichael failed to pay the annual fee as a result of her advanced age and dementia, and her safe deposit lease lapsed.

• On February 1, 2012, Goliath sent the statutorily required, written notice via regular mail to

Ms. Carmichael’s home address which stated her safe deposit rent must be received within 30 days; otherwise, the box’s contents would be transferred to the Controller in one year. Goliath also attempted to call Ms. Carmichael at the number she had initially provided, but the line was disconnected. Like the courtesy notice, banks are not obligated to telephonically

3

reach out to clients regarding the potential escheat of their property. Despite these efforts, Ms. Carmichael never paid the rental fee.

• On March 2, 2013, Goliath informed the Controller that it was in possession of Ms.

Carmichael’s presumptively abandoned property, provided her name, home address, and phone number, and informed the Controller of its attempts to contact Ms. Carmichael.

• On March 6, 2013, Goliath opened Ms. Carmichael’s safe deposit box at the State’s expense

and delivered the Egg to the Controller. The Controller estimated its value to be $350. The Controller promptly mailed a written notice via certified mail to Ms. Carmichael, explaining that the State would become the owner of the Egg if she did not file a claim within 2 years. The Controller then listed the Egg on its escheat Website, indicating that it was worth “less than $1,000.”

• One week after mailing the certified letter to Ms. Carmichael, the letter was returned to the

the Controller unsigned and unclaimed. The Controller then sent an identical written notice via regular mail to Ms. Carmichael’s address but never received a response.

• On September 1, 2013, an Office of the Controller employee noticed the Egg’s distinctive

features and believed it to be genuine. A subsequent appraisal revealed that the Egg was a real Romanoff Imperial Faberge Egg worth approximately $20 million dollars. The Controller updated the Website to indicate that the Egg’s value was “greater than $1,000” and that it would be sold at public auction. The Website denotes that property will be sold at public auction by inserting a small asterisk after the estimated value.

• On December 8, 2014 The Controller published a half-page advertisement in the New

Columbia Gazette, explaining that the Egg would be auctioned on March 8, 2015. The advertisement described the property as “one Romanoff Imperial Faberge Egg” with an estimated value “in excess of $10,000”; it did not specify that the Egg was in fact worth millions of dollars.

• On February 4, 2015, thirty days before the 2-year custodial period expired, the Controller

published the same half-page advertisement in the Gazette. At the auction, Mr. Viktor Vekelsberg purchased the Egg for $25,000,000 and placed that amount in an escrow account pending the expiration of the statutory holding period.

• Having heard about the Egg’s sale from her daughter when its purchase had been covered on

the nightly news, Ms. Carmichael contacted the Bank on March 9, 2015, the day after the auction, and learned that the State had taken possession of the Egg.

• On March 15, 2015, Ms. Carmichael filed a claim of ownership of the Egg with the

Controller via the Website, but was informed that the two-year period had expired and that the Egg now belonged to the State

.

4

E. Facts Regarding Petitioner Gerald Johanssen • Gerald Johanssen is a seventy-five year old retired carpenter who was unaware of the Goliath

State Bank savings account belonging to his daughter, Phoebe Heyerdahl, at the time of her death. Petitioner Johanssen is the sole legal heir to his daughter’s estate.

• Phoebe was a multi-millionaire tech entrepreneur who sadly passed away with her husband, Siegfried Heyerdahl, in a tragic Segway accident on January 15, 2010. She had opened a savings account in 1985 while a student at New Columbia Tech under the name Phoebe Johanssen. The account’s contact information for Phoebe was limited to the address of Phoebe’s off-campus apartment and its landline phone.

• When Phoebe graduated in 1987, the account contained $700. Phoebe quickly became a very

successful entrepreneur and likely forgot about her modest savings account, as she never made a deposit or withdrawal on the account after graduating from college.

• As of January 1, 2011, the savings account remained under her maiden name and had grown

to $1,989.40 due to accrued interest. • On January 14, 2011, Goliath sent a written notice to Phoebe’s off-campus address, stating

that a credit or debit must be made to the account within 30 days of the date of the notice; otherwise, the amount would escheat to the State in one year. Goliath attempted to reach her by telephone, but the number had changed to another party.

• On February 15, 2012, Goliath notified the Controller that it possessed Phoebe’s savings

account and provided Phoebe’s maiden name, her off-campus address, and her old landline number. Goliath also informed the Controller of its attempt to reach Phoebe and reported that the savings account held $1,989.40 plus $40.17 of earned interest for 2011.

• On February 16, 2012, Goliath transferred the $1,989.40, plus the $40.17 in interest, to the

Controller. On February 17th, the Controller mailed a written notice via certified mail to Phoebe’s off-campus address, stating that the amount in her account would permanently escheat to the State if she did not file a claim within 2 years. The Controller also posted the relevant information to its Website under Phoebe’s maiden name and indicated that the property was valued at “greater than $1,000.” The Controller also attempted to reach Phoebe at the phone number Goliath provided, but the line was now disconnected.

• One week after mailing the certified letter to Phoebe, the letter was returned to the Controller

unsigned and unclaimed. The Controller then sent an identical notice via regular mail to Phoebe’s same address and did not receive a response.

• On March 8, 2015 Mr. Johanssen saw the story about the Faberge Egg on the nightly news,

which prompted him to search the Controller’s Website for property belonging to Phoebe. After discovery of Phoebe’s account, he contacted the Controller the following day and was advised that the money in Phoebe’s account had permanently escheated to the State in 2014.

F. Procedural History

5

On April 15, 2015, petitioners Carmichael and Johanssen filed suit against Controller Elizabeth Thornberry. The complaint seeks (1) a declaration that the Act violated the Due Process and Takings Clauses of the U.S. Constitution; (2) just compensation in the amount of $2,149.05 to be paid to petitioner Johanssen to reimburse the value of his escheated savings account plus interest; and (3) an injunction to prevent the Act’s enforcement, to void the sales contract between Viktor Vekelsberg and New Columbia, and to direct New Columbia to return the Egg to petitioner Carmichael. Respondent Viktor Vekelsberg, the Faberge Egg’s purchaser, agreed to be bound by the judgment of the court. On November 2, 2015, the District Court for the District of New Columbia found that petitioner-plaintiffs failed to show a genuine issue of material fact and granted respondent-defendants’ motion for summary judgment. The district court also observed that New Columbia had afforded all process that was due and that New Columbia lawfully escheated petitioner-plaintiff’s property because they abandoned it. On April 10, 2016, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Thirteenth Circuit affirmed the district court, with Judge Quiggley dissenting. On appeal, the parties stipulated that the case presented no Eleventh Amendment issues. On September 1, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court granted petitioners’ petition for writ of certiorari limited to the following two issues: (1) Did respondent Controller of New Columbia violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution by failing to provide petitioners adequate notice of the proposed escheat of their property?, and (2) Did respondent Controller of New Columbia violate the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment as incorporated through the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution by improperly treating petitioners’ property as abandoned and hence subject to escheat by the State?

6

DISCUSSION

I. Issue I: Did respondent Controller of New Columbia violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution by failing to provide petitioners adequate notice of the proposed escheat of their property?

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that no state shall “deprive

any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”1 Under the heavily cited

Mullane standard, the Amendment requires that the state provide “notice reasonably calculated

under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and afford

them an opportunity to present their objections.” Mullane v. Cent. Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339

U.S. 306, 314 (1950). The Supreme Court “has not committed itself to any formula achieving a

balance between these interests in a particular proceeding or determining when constructive notice

may be utilized or what test it must meet.” Id. However, “notice must be of such nature as

reasonably to convey the required information, and it must afford a reasonable time for those

interested to make their appearance.” Id. (internal citations omitted). Thus, due process is satisfied

if “the practicalities and peculiarities of the case . . . are reasonably met.” Id. at 314–15; see also

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 481 (1972) (“[D]ue process is flexible and calls for such

procedural protections as the particular situation demands.”). On the other hand, due process is not

satisfied if notice is no more than “a mere gesture,” and the means employed are not “desirous of

actually informing the absentee.” Mullane, 339 U.S. at 315.

Notwithstanding the lack of a bright-line rule, the Court has recognized three crucial factors

in analyzing the sufficiency of due process: “[f]irst, the private interest that will be affected by the

official action; second, the risk of erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures

used, and the probable value, if any, of additional or substitute procedural safeguards; and finally,

1 It is undisputed in this case that the issue of procedural due process involves the alleged deprivation of property.

7

the Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative

burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirement would entail.” Mathews v.

Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319, 335 (1976) (emphasis added); see also Mullane, 339 U.S. at 314 (“Against

this interest of the State we must balance the individual interest sought to be protected by the

Fourteenth Amendment. The fundamental requisite of due process of law is the opportunity to be

heard.”) (citation omitted). Accordingly, the procedural due process issue asks whether New

Columbia’s efforts to notify petitioners satisfied both the individuals’ and State’s interests, and

whether New Columbia’s notification procedures resulted in the erroneous deprivation of

petitioners’ property.

While due process ought to employ means “desirous of actually informing the absentee,”

due process “does not require that a property owner receive actual notice before the government

may take his property.” Jones v. Flowers, 547 U.S. 220, 226 (2006). This principle invites debate

into whether the State’s methods and means were constitutionally sufficient to inform the affected

property owner. Jones v. Flowers addressed “whether due process entails further responsibility

when the government becomes aware prior to the taking that its attempt at notice has failed.” Id.

at 227. The Court held that, in the forfeiture context, a state government must do something more

“when a certified letter sent to the owner is returned unclaimed” before the government forces a

tax sale of one’s residence. Id. at 227, 229 (“If the Commissioner prepared a stack of letters to mail

to delinquent taxpayers, handed them to the postman, and then watched as the departing postman

accidentally dropped the letters down a storm drain, one would certainly expect the

Commissioner’s office to prepare a new stack of letters and send them again.”). The Court

suggested that the State could send a letter by regular mail “so that a signature was not required”

or to post a notice directly on the taxpayer’s front door. Id. at 234–35. However, the State was not

8

required to go as far as searching for the taxpayer’s current address in a local phonebook or

government records (i.e., income tax rolls) because an “open-ended search for a new

address . . . imposes [significantly greater] burdens on the State.” Id. at 235–36; see also Taylor v.

Westly, 780 F.3d 928, 939 (9th Cir. 2015) (holding that Due Process Clause did not obligate

California Controller to consult government databases to retrieve updated information because “it

exceeds the minimum due process requirements”). Accordingly, Jones v. Flowers asks whether

New Columbia was constitutionally required to notify petitioners through additional means when

its certified letters can back unclaimed, or whether New Columbia had satisfied its due process

obligations by sending one letter by regular mail, despite actual knowledge that the bank had also

failed to reach petitioners before transferring their property.

Another important aspect of the procedural due process issue is the constitutional

sufficiency of the Website and newspaper publications in informing property owners of their

escheated property. Courts frequently question the adequacy of publications because “[c]hance

alone brings to the attention of even a local resident an advertisement in small type inserted in the

back pages of a newspaper . . . . The chance of actual notice is further reduced when . . . the notice

required does not even name those whose attention it is supposed to attract, and does not inform

acquaintances who might call it to attention.” Mullane, 339 U.S. at 315. Such is the case here

because New Columbia is not required to list the property owner’s name in the New Columbia

Gazette.

However, “publication traditionally has been acceptable as notification supplemental to

other action which in itself may reasonably be expected to convey a warning.” Id. at 316 (emphasis

added). In fact, this minimal form of notification may be adequate when the state (lawfully)

assumes “that one who has left tangible property in the state either has abandoned it, in which case

9

proceedings against it deprive him of nothing, or that he has left some caretaker under a duty to let

him know that it is being jeopardized.” Id. (internal citation omitted). Because this case deals with

the escheat of unclaimed property, one question is whether New Columbia’s notification

procedures accord with the state’s presumption of abandonment because the risk of erroneous

deprivation is (arguably) not significant.

Notably, one Justice has recently observed that “States have shortened the periods during

which property must lie dormant before being labeled abandoned and subject to seizure. And some

States still rely on decidedly old-fashioned methods that are unlikely to be effective. . . . [M]any

states appear to be doing less and less to meet their constitutional obligation to provide adequate

notice before escheating private property.” Taylor v. Yee, 136 S. Ct. 929, 930 (2016) (Alito, J.,

concurring in denial of certiorari) (internal citations omitted). To rectify this alarming trend, Justice

Alito stated that “States must employ notification procedures designed to provide the pre-escheat

notice the Constitution requires.” Id. This has been a prevailing view in several courts, including

the Ninth Circuit.

In the Taylor line of cases, the Ninth Circuit first granted injunctive relief to plaintiff

property owners because the Controller had erroneously relied on corporations and banks to

provide pre-escheat notice. See Taylor v. Westly, 488 F.3d 1197, 1201 (9th Cir. 2007) (“[T]he State

again cites no authority for the proposition that reliance on the likelihood that a third party will

give notice is ‘constitutionally adequate.’ In fact, because the Jones decision clearly holds that the

State must give notice, California’s argument is not only novel, it is apparently foreclosed by

Supreme Court precedent.”). The court also found problematic that California placed

advertisements in newspaper to inform citizens about the state’s escheat website and that the state

provide written, post-escheat notices to owners. Id. The following year, after California amended

10

its law to cure its procedural due process defects, the Ninth Circuit rejected plaintiffs’ facial due

process challenge because “the Controller is [now] required to provide pre-escheat notice.” Taylor

v. Westly, 525 F.3d 1288, 1289 (9th Cir. 2008). The Ninth Circuit later upheld its decision in an

as-applied challenge in Taylor v. Westly, 780 F.3d 928 (9th Cir. 2015). The Taylor cases yield

questions as to whether New Columbia took adequate steps to inform citizens about the existence

of the State’s escheat website—the only forum through which individuals can file claims—and

whether New Columbia was obligated to provide pre-escheat notice to petitioners, in addition to

Goliath State Bank’s pre-escheat notices.

A. Petitioners’ Arguments

Petitioners will likely argue that New Columbia did not provide adequate notice because

(1) only Goliath State Bank took efforts to notify petitioners before Goliath transferred their

property; (2) under Taylor v. Yee’s interpretation of Jones v. Flowers and the Due Process Clause,

New Columbia could not constitutionally rely on the pre-escheat efforts of a third party to satisfy

its own due process obligations; (3) New Columbia had actual knowledge that Goliath had failed

to get in touch with petitioners (i.e., while Goliath had sent notices via regular mail, its telephone

calls were unsuccessful because the lines were either disconnected or assigned to someone else),

which obligated New Columbia to retrieve more up-to-date information because the Controller

likely knew that petitioners no longer resided at the listed residences; and (4) New Columbia did

not individually notify Petitioner Carmichael when it revalued the Egg from $350 to tens of

millions of dollars and instead inserted a small asterisk on its Website next to the listed property,

indicating that it would be sold at public auction. Petitioners could point to Mathews to argue that

the State should have done more to notify Petitioner Carmichael when the State realized the

significant difference in the Egg’s value. Accordingly, Mullane’s admonition that the “means

11

employed must be such as one desirous of actually informing the absentee might reasonably adopt

to accomplish it,” 339 U.S. at 315, was not satisfied for Carmichael. Relatedly, petitioners could

argue that the New Columbia Gazette notices did not satisfy the due process requirement because

there was no guarantee that Petitioner Carmichael would actually read it, despite the Gazette being

a publication of wide circulation.

Further, petitioners might challenge the adequacy of the Website. They could say that the

Website does not describe the escheated property in detail, that the Website only lists property that

has already escheated to the State, and that the Website conveys inaccurate information by listing

the property as either “greater than” or “less than” $1,000. Accordingly, this arbitrary benchmark

does not inform owners of the precise value of the escheated property, which frustrates efforts to

identify their property and file a claim. Petitioners could also argue that the Controller failed to

abide by its statutory mandate to “routinely maintain” the database “to provide reasonably

accessible information” by listing individuals, such as Phoebe Heyerdahl, who have long since

deceased. Lastly, petitioners could argue that the Website is largely unknown to the public, which

defeats its principal purpose as the forum through which to file claims with the Controller.

Petitioners may try to argue that the Controller should have taken additional, “reasonable”

steps to inform petitioners when its certified letters came back, such as by consulting government

databases to retrieve up-to-date information regarding petitioners’ whereabouts. However,

petitioners will have to reconcile Jones v. Flowers and Taylor v. Westly, which both stand for the

proposition that “open ended” searches are too excessive and burdensome under the Due Process

Clause, notwithstanding the Mullane requirement that the state must take reasonable steps to

inform property owners.

B. Respondent’s Arguments

12

Respondents will likely argue that New Columbia satisfied its due process obligations

because, under Jones v. Flowers, it sent notice via regular mail once the certified letters came back

unsigned and unclaimed. New Columbia, therefore, was under no further obligation to conduct an

“open search” of government databases, such as the New Columbia Tax Board which collects

taxpayers’ Social Security numbers and related information including current addresses. To

require New Columbia to conduct limitless searches for each resident with whom they cannot

easily contact would be too administratively burdensome and beyond the requirements of the Due

Process Clause.

To that end, respondents may also argue that neither the Due Process Clause nor the

Supreme Court impose a bright-line rule prescribing what steps the state must take to inform

property owners. Accordingly, New Columbia chose constitutionally adequate means under the

circumstances and abided by its statutory obligations by sending written notices when required

and promptly listing the property on its Website. Additionally, the Due Process Clause does not

require, and the Supreme Court has not held, that the state must provide pre-escheat notice in

tandem with third parties. One argument for this position is that the owner has already abandoned

the property in question and therefore has little to no interest at stake. If pre-escheat notice is

required, the bank satisfied this pre-escheat obligation and in fact took extra-statutory measures to

contact petitioners. Although those measures were unsuccessful, their failure did not then obligate

New Columbia to take its own “extra-constitutional” measures to contact petitioners.

Respondents can also defend the use of its Website because it is widely accessible by virtue

of being an online system, and the Act requires that each written notice include a link to the

Website. Therefore, both the individualized notices and the general publications inform citizens

about where they can access the database and how they can file a claim with the Controller. New

13

Columbia is not obligated to more broadly advertise the Website’s existence. Further, the Due

Process Clause does not require more than the necessary information to reasonably inform property

owners so that they can timely make their appearance known to the State. See Mullane, 339 U.S.

at 314. Accordingly, the Website provides necessary information by listing the owner’s full name,

the last known address, and the bank which formerly held the property. By searching for one’s

name and zip code, the Website yields necessary, if not sufficient, information to locate one’s

property.

II. Issue II: Did respondent Controller of New Columbia violate the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment as incorporated through the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution by improperly treating petitioners’ property as abandoned and hence subject to escheat by the State?

In Anderson National Bank v. Luckett, the Supreme Court stated that “it is no longer open

to doubt that a state . . . may compel surrender to it of deposit balances, when there is substantial

ground for belief that they have been abandoned or forgotten.” 321 U.S. 233, 240 (1944). For

years, states have escheated property on the theory that once property has been abandoned—and

ceases to have an owner—the State has a residual claim to the property’s title that trumps the claim

of the institution holding the property. Teagan J. Gregory, Note, Unclaimed Property and Due

Process: Justifying “Revenue-Raising” Modern Escheat, 110 Mich. L. Rev. 319, 320-321 (2011).

Recently, financial institutions and individuals whose property the state escheated have

challenged escheat statutes by claiming that they exact Fifth Amendment takings without paying

“just compensation.” See Am. Express Travel Related Servs., Inc. v. Sidamon-Eristoff, 669 F.3d

359 (3d Cir. 2012); Taylor v. Westly, 402 F.3d 924 (9th Cir. 2005). The crux of the takings issue

is that in “recent years, States have shortened the periods during which property must lie dormant

before being labeled abandoned and subject to seizure.” Taylor v. Yee, 136 S. Ct. 929 (2016) (Alito,

J., concurring in denial of certiorari); T. Conrad Bower, Note, Inequitable Escheat?: Reflecting on

14

Unclaimed Property Law and the Supreme Court’s Interstate Escheat Framework, 74 Ohio St.

L.J. 515 (2013) (noting that five states have reduced their dormancy periods to three years).

In early Supreme Court cases, the dormancy periods were much longer and the process for

determining abandonment was not automatic. For instance, in Anderson, the dormancy periods for

various property ranged from ten to twenty-five years and property could only permanently escheat

after a judge declared that the property had been abandoned under the State’s general abandonment

laws. 321 U.S. 238; see also Security Savings Bank v. California, 263 U.S. 282, 284 (1923)

(escheat statute required a twenty-year dormancy period and a judicial declaration that the property

was abandoned); Provident Institution for Saving in the town of Boston v. Malone, 221 U.S. 660,

662 (1911) (escheat statute had a thirty-year dormancy period).

Accordingly, the question becomes whether the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment

restricts a state’s ability to establish a dormancy period below a certain number of years—e.g.

twenty years, as is standard for adverse possession—or whether a State may establish as short a

dormancy period as it deems appropriate.

A. Ms. Carmichael’s Egg

Petitioners’ Position

Petitioners will argue that New Columbia’s taking of Ms. Carmichael’s Faberge Egg is a

classic per se taking of personal property. See Horne v. Dep’t of Agriculture, 135 S. Ct. 2419, 2426

(2015) (“Nothing in the text or history of the Takings Clause, or our precedents, suggests that the

rule is any different when it comes to the appropriate of personal property”). Ms. Carmichael

owned her Egg in fee simple, and New Columbia broke into her safe deposit box, physically

removed the Egg, and sold it to the highest bidder. Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v.

15

Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 535 U.S. 302, 324 (2002) (noting that a classic taking occurs

when “the government directly appropriates private property for its own use.”).

Petitioners may argue that the Fifth Amendment may allow a taking involving abandoned

property, but that the Fifth Amendment imposes a limit on how states may statutorily define

“abandonment.” Petitioners may argue that the Supreme Court should strike the Act because New

Columbia is clearly trying to circumvent the Fifth Amendment by fiat. First, the Act’s legislative

history shows it is being used as a tool to close state deficits, not to build roads or provide other

public goods. Second, they may argue that New Columbia’s reduction of the holding period from

twenty years to three years and expanding of the categories of property subject to escheat is proof

of the State’s “slippery slope” into aggressive property appropriation.

Respondents’ Position

Respondents will argue that the Supreme Court has long held that states may escheat

property abandoned at common law or by statute. See Anderson National Bank v. Luckett, supra.

The logic is airtight: when a person abandons property, they are giving up all of their ownership

rights to it. Therefore, the former owner of abandoned property cannot claim that the state took

anything from them when the state escheats abandoned property.

Respondents counter Petitioners’ policy argument regarding states attempting to

circumvent the Fifth Amendment by arguing that states escheat property to protect their citizens,

not abuse them. Respondents would argue that that States are more stable than banks or other

financial entities, so they are better equipped to protect private property until the owner comes to

claim it and that they are easing the pressure on an already overburdened banking industry by

relieving them of the duty to manage abandoned property. Last, they might argue it is better for

16

States to put abandoned property to use for state purposes than for private banks to profit from

abandoned property.

B. Mr. Johanssen’s Savings Account

Petitioners’ Position

Regarding the principal of Mr. Johanssen’s savings account ($1,989.40 + $40.17 in accrued

interest at the time of transfer), Petitioner’s will argue that it is a per se physical taking in the same

manner as Petitioner Carmichael’s Egg because Petitioner had tangible property saved in an

account which New Columbia took.

Regarding the future interest on the savings account after the transfer to New Columbia,

however, Petitioners will argue New Columbia committed a regulatory taking. A regulatory taking

occurs when Government restrictions on one’s use of their property go “too far.” Horne v.

Department of Agriculture, 135 S. Ct. 2419, 2427 (2015). Mr. Johanssen does not own the interest

he would have received had the savings account remained at Goliath bank (because the Bank had

not yet paid it); however, Petitioner Johanssen certainly would have received that money but for

the State’s interference.

The Supreme Court has established three independent tests for determining whether a

regulatory taking occurred. The first comes from Loretto: “where government requires an owner

to suffer a permanent physical invasion of her property – however minor – it must provide just

compensation.” Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A. Inc., 544 U.S. 528, 538 (2005) (citing Loretto v.

Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419 (1982)). A second variety of a regulatory

taking, a Lucas taking, “occurs when a regulation completely deprives an owner of all

economically beneficial use of her property.” Lucas v. S.C. Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003, 1019

17

(1992). If either a Loretto or Lucas taking occurs, the regulatory action is a “per se” taking. Lingle

v. Chevron U.S.A. Inc., 544 U.S. 528, 537–39 (2005).

Finally, the Supreme Court also analyzes whether a regulatory taking occurred using an ad

hoc, fact-based balancing test with three main factors: (1) the “economic impact of the regulation

on the claimant,” (2) the “extent to which the regulation has interfered with distinct investment-

backed expectations,” and (3) the “character of the government action,” which evaluates the extent

to which Government action infringes on the owner’s property rights. Penn Central Transp. Co.

v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104, 124 (1978).

Petitioner Johanssen may argue that a Lucas taking occurred because the government

denied Petitioner all economically beneficial use of the savings account by preventing him from

earning interest in that interest is the only way savings accounts earn money.

Alternatively, Petitioner may argue a taking occurred under Loretto, especially in response

to Respondent’s argument that the interest does not amount to a taking because it represents tens

of dollars at the most. Under Loretto, it makes no difference how small the government’s invasion

is, at the point in which New Columbia deprives Petitioner of any portion of the savings account

to which he is entitled, a taking has occurred and compensation must follow.

Petitioner Johanssen may also argue that a taking occurred under Penn Central occurred

although the factors do not weigh in his favor: (1) the economic impact of the regulation on the

claimant is minimal because he is only out a very small amount of interest and just inherited

millions from his daughter, and (2) he had no “investment-backed expectations” because he

received the account as a gift as part of his daughter’s estate. Petitioner Johanssen does have a

good argument that the “character of the government’s action” indicates it was a taking because

18

the government totally deprived him of the property. However, it is a balancing test, so when all

three factors are considered together, Petitioner Johanssen’s case is not strong.

Respondents’ Position

Regarding the principal in the saving’s account, Respondents will make the same

arguments as it did regarding the Ms. Carmichael’s Egg—namely, that the property was

abandoned, therefore Petitioner Johanssen cannot claim anything was taken from him. However,

if Respondents “lose” on the argument that the property was abandoned, there does not appear to

be a colorable argument that a taking did not occur.

Regarding the Lucas and Loretto arguments—that New Columbia’s escheat of the savings

account’s future interest is a regulatory taking—Respondents would argue that nothing was taken

from the Petitioner because he did not yet own the interest because the bank had not yet paid it.

If Petitioners do argue Penn Central, then Respondents would make the argument given

above—namely, that Petitioners argument is very weak on the first two prongs, so, when the

factors are balanced against one another, no taking occurred.

19

SAMPLE QUESTIONS

I. ISSUE I – PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS Questions for Petitioners

1. Is there a constitutional obligation for states, rather than banks or other third parties, to provide pre-escheat notice to property owners?

2. If the state is not constitutionally required to provide pre-escheat notice itself, is there a binding decision that requires states to provide pre-escheat notice?

3. Is the risk of erroneous deprivation particularly low or insignificant because the state can lawfully assume that petitioners abandoned their property?

4. Should the state have done more to obtain updated information about the petitioners’ whereabouts? Wouldn’t this be overly burdensome for the state to conduct “open searches” on government databases?

5. Did the state not fulfill its due process obligations by sending a second letter by regular mail to petitioners when the certified letters came back unclaimed?

6. What other reasonable steps should the state have taken to provide notice to petitioners? 7. What obligated the state to again inform Ms. Carmichael about her Egg when the

Controller realized it was worth millions of dollars? 8. Were the petitioners themselves not obligated to provide the bank or the state with

current and up-to-date information? 9. Is there a bright-line rule that a state must follow in affording due process? 10. How much should the Court weigh the individual’s private interests? What about the

state’s interests? 11. How does the Court know when a citizen, who has presumptively abandoned their

property, received all the process that was due? Questions for Respondents

1. How much due process did New Columbia owe to petitioners? 2. Is the state not constitutionally obligated to provide pre-escheat notice before it seizes

unclaimed property? 3. Why was the state not under an obligation to conduct an “open-search” of government

databases to retrieve updated information regarding petitioners’ whereabouts? 4. If the Controller had knowledge that petitioners no longer resided at their last listed

addresses, shouldn’t the state have taken alternative steps to inform or locate petitioners? 5. Shouldn’t the Controller have individually informed Ms. Carmichael of her escheated

Faberge Egg when the Controller realized the Egg was worth millions of more dollars? Didn’t this substantially increase the risk of erroneous deprivation?

6. Is inserting an asterisk on the Website considered adequate notice to the interested property owner that his or her property will be sold at a public auction?

7. Isn’t the chance of notifying specific individuals significantly reduced when the state relies on general publications?

8. Is the risk of erroneous deprivation high when the state assumes, without verifying, that an individual has abandoned his or her property?

9. How does the state know it has afforded all the process that was due?

20

II. ISSUE II – ESCHEAT AND TAKINGS Questions for Petitioners

1. Are you asking this Court to overrule our previous holding in Anderson v. Luckett, 321 U.S. 2333 (1944) that States may escheat abandoned property?

2. Has a taking occurred when New Columbia custodially escheats the property, although it may be returned?

3. Is there a point after which property has sat untouched for so long that a State could escheat it?

a. (If Petitioner responds “No”) That does not seem like an efficient or equitable way to dispose of unclaimed property. Does the Constitution really require that property be left with the holder for all time if it is not claimed?

b. (If Petitioner responds “Yes”) How should the Court determine the length of time after which abandoned property may be escheated without implicating the Fifth Amendment?

4. How short of a dormancy period is too short, and, why should we not leave it up to the States so that the citizens may decide—at the ballot box—how their property may escheat?

5. Can either Petitioner claim that they had an “investment backed expectation” in their property because both the savings accounts and the Egg were received as gifts? Doesn’t this mean they lose under Penn Central?

6. Petitioner Johanssen did not “own” the interest he would have received had his savings account remained with the bank. How, therefore, can the State “take” property that does not belong to Petitioner Johanssen?

7. Why isn’t the state law allowing it not to pay interest on savings accounts during the two year holding period not just a tax or fee to cover the state’s custodial escheat expenses?

8. Is it not preferable that property escheat to the State instead of remaining in the bank’s hands where it only enriches the bank’s shareholders?

9. Why does it matter that the Statute had a three-year dormancy period? Both Petitioners neglected their property for decades. Can’t the State escheat the property based on the theory of common law abandonment?

10. Have we, or a lower court, ever struck an escheat statute of Fifth Amendment grounds? 11. How does due process intersect with the takings issue before us? Can’t we just hold that

the property was abandoned because both Petitioners failed to timely respond to the multiple notices sent by the bank and the State?

12. Was there really a taking of the interest given its de minimis value? Questions for Respondents

1. The government physically broke in to Petitioner Carmichael’s safe deposit box and removed $25 million in personal property. How is this anything other than a taking?

2. Could the State escheat property were it not abandoned? 3. How could Petitioner Johanssen abandon property that he did not know existed? Doesn’t

it seem wrong to escheat his savings account given the circumstances? 4. How is taking Petitioner Johanssen’s interest not a Lucas taking? The state has denied

him all economically viable uses for their property.

21

5. All other things being equal, would the Act pass muster under the Fifth Amendment if it had a one year combined dormancy and custodial escheat period.

a. (If the response is Yes) What about a month or a Day? If there is a line, where and how do we draw it?

6. Does Loretto apply to Petitioner Johanssen’s interest? 7. Could the state constitutionally amend the statute so that property that has sat unused in a

safe deposit for 20 years may be escheated even when the box’s lease continuing to be paid?

8. In our previous decisions have we ever approved so short a dormancy period? 9. One of the rationales for the statute is that the State is a more stable entity than a bank,

so, the State should escheat private property to protect it until its owner claims it. Is New Columbia really protecting private property when the ultimate result of the Act is that the State takes title to escheated property?

23

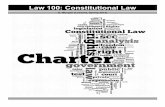

Welcome To The New Columbia Property Database

www.whereismyproperty.newcolumbia.org Home General Info Resources Help

SEARCH! First Name Last Name Zip Code

Susan Carmichael 00003

Please complete all fields.

Name Last Known Address Reported By Estimated Value CARMICHAEL, SUSAN PO BOX 1

Newtown, New Columbia 00003 GOLIATH STATE BANK, INC. Greater than $1,000

CARMICHAEL, SUSAN 415 White Street, Apt. 104 Newtown, New Columbia 00003

MONTGOMERY INVEST. FUNDS Less than $1000

CARMICHAEL, SUSAN 1405 Old Harbor Way Newtown, New Columbia 00003

GOLIATH STATE BANK, INC. Greater than $1,000 *

CARMICHAEL, SUSAN 1 Black Bird Circle Newtown, New Columbia 00003

UNITED BANK CO. Greater than $1,000

CARMICHAEL, SUSAN PO BOX 199 Uptown, New Columbia 00003

GOLIATH STATE BANK, INC. Less than $1000

Displaying 1-5 of 5 results NEXT LAST

NEXT LAST

PROPERTY OF

OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER 100 CENTRAL WAY

NEWTOWN, NEW COLUMBIA 00002 WWW.CONTROLLER.NCOL.GOV

Think you found your property? Click here to access the New Columbia Abandoned Property Claim Form to start the process. You can also access the New Columbia Abandoned Property Act here.

24

Timeline for Petitioner Susan Carmichael

Date Statutory Milestone Description of Event

January 10, 1983

Petitioner leases a safe deposit box with Goliath State Bank (“Goliath” or “the Bank”) and provides her then home address and telephone number. She does not provide an email address, and the Bank does not require one. She places what she thinks at the time is an imitation Romanoff Imperial Faberge Egg with negligible value.

2010 The State Legislature enacts the New Columbia Abandoned Property Act, which reforms how banks handle safe deposit boxes.

early 2011 Petitioner moves in with daughter, Clara Thompson, given Petitioner’s deteriorating mental health.

December 1, 2011

Goliath mails courtesy notice to Petitioner, reminding her of the annual lease fee that is due by January 1. Goliath is not statutorily obligated to provide courtesy notices.

January 1, 2012

Triggering event

Due date for annual lease fee, which Petitioner fails to pay as a result of her age and advanced dementia. Petitioner has also failed to access her safe deposit box in 2011.

February 1, 2012

Bank’s pre-escheat notice

Goliath audits its safe deposit boxes which (1) have not been accessed in the previous calendar year and (2) for which the required lease fee has not been received. Goliath mails written notice via regular mail to Petitioner, giving her 30 days to pay; otherwise, her property may escheat to the State one year thereafter. Goliath also calls Petitioner at the number she provided in 1983 to inform her of the risk of escheatment. The Bank is under no statutory obligation to do so. The number, however, is disconnected, and the Bank cannot leave a voicemail.

March 2, 2012 1-year holding / dormancy

period begins

The 30-day period expires because Petitioner did not submit the annual fee. The 1-year holding period commences during which the safe deposit box’s contents are considered “presumptively abandoned.” Under the statute, Petitioner must simply pay the annual fee during this 1-year hold period to reclaim her property.

March 2, 2013 1-year holding / dormancy

period ends

The 1-year hold period lapses because Petitioner still did not submit the annual fee. Goliath files a report with the State, informing the Controller that it has transferable,

* The property is considered high-value and will be sold at public auction.

Updated as of December 8, 2014

25

“presumptively abandoned” property. Goliath also supplies Petitioner’s contact information (which is still pulled from the 1983 lease agreement she signed) and explains what steps it has taken to notify Petitioner (e.g., the Feb. 1 notice and phone call).

March 3, 2013 Controller instructs the Bank to access the safe deposit box at the State’s expense.

March 6, 2013 2-year custodial period begins

State’s post-

escheat notice

Goliath access the safe deposit box and delivers the imitation Faberge Egg to the Controller’s office. The Controller (1) appraises the Egg at approximately $350 on the basis that it an imitation, (2) sends written notice via certified mail to Petitioner, and (3) posts the property to the Website as “less than $1,000.”

March 13, 2013

The Controller’s written notice comes back unclaimed and unsigned. The Controller then immediately mails a written notice to Petitioner’s same address via regular mail. There is no response.

September 1, 2013

Six months after the Controller received the Egg, the Controller instructs the Egg be re-appraised given an employee’s concern. It is discovered the Egg, an authentic Romanoff Imperial Faberge Egg, is worth somewhere in the range of $15 to $30 million. The Controller updates the Website to (1) list the property as now “$1,000 or greater” and (2) insert an asterisk that the property will be publically auctioned.

December 8, 2014

State’s first pre-auction

notice

The Controller publishes in the local gazette that the property will be auctioned in 90 days.

February 4, 2015

State’s second pre-auction

notice

The Controller publishes a second spread in the local gazette stating that the property will be auctioned on March 8, 2015.

mid-February 2014

A local reporter, based on a tip received from the Office of the Controller, writes a story that New Columbia will be auctioning a Romanoff Imperial Faberge Egg and publishes a front-page spread, which generates widespread attention including that of Viktor Ekelsberg, a Russian billionaire.

March 6, 2015 2-year custodial period ends

The 2-year custodial period expires because Petitioner has not filed a claim via the Website.

March 8, 2015 Public auction The Controller holds the public auction at which Viktor Ekelsberg pays $25,000,000. The Controller and Mr. Ekelsberg enter into a sales contract, and the money is deposited into an escrow account for 60 days.

26

The evening of the auction, Petitioner’s daughter, Clara Thompson, sees on the nightly news that the State has recently sold the Faberge Egg which she knows her mother had placed in the safe deposit box decades ago.

March 9, 2015 Ms. Carmichael calls the Bank to inquire about her safe deposit box, but the Bank says the State of New Columbia has taken possession of it.

March 15, 2015

Clara Thompson, on behalf of her mother, files a claim with the Controller on the Website to reclaim the property, but she is informed she cannot do so since the State has taken ownership of the Egg.

April 15, 2015 Ms. Carmichael brings suit against the Controller and Viktor Ekelsberg in the District Court for the District of New Columbia.

May 8, 2015 Date by which the State would transfer the Egg to Viktor Ekelsberg and the $25,000,000 would be deposited into the State Treasury

27

Timeline for Petitioner Gerald Johanssen

Date Statutory Milestone Description of Event

1985

Ms. Phoebe Johanssen, Petitioner’s daughter, opened a savings account with Goliath State Bank while a student at New Columbia Tech. When she opened the account, she provided her off-campus apartment address and landline.

1987 Ms. Phoebe Johanssen graduates from New Columbia Tech. The savings account holds $700.00. After graduation, she did not make any deposit or withdrawal. NOTE: New Columbia’s old escheat program did not apply to savings accounts of less than $10,000, so accounts could lay dormant and inactive for an indefinite period of time.

(between 1987 and 2010)

Phoebe marries Siegfried Heyerdahl, but Phoebe neglects to update the savings account to reflect her married surname because she has (presumably) forgotten about this small account.

2010 The State Legislature enacts the New Columbia Abandoned Property Act, which reforms how banks handle small savings accounts.

January 15, 2010

Mrs. Phoebe Heyerdahl dies with her husband in a Segway accident. Her only remaining legal heir is her father, Petitioner Gerald Johanssen.

January 1, 2011

Triggering event

Account has been inactive for the previous calendar year (i.e. 2010) because Phoebe has not made a transaction on the account, which now holds $1,989.40 due to accrued interest over the years.

January 14, 2011

Bank’s pre-escheat notice

Goliath mails written notice via regular mail to Phoebe’s old off-campus address, giving her 30 days to make a deposit or withdrawal; otherwise, her property may escheat to the State one year thereafter. Goliath also calls Phoebe at the number she provided in 1985, but it has been assigned to someone else. The Bank is under no statutory obligation to make such a call.

February 15, 2011

1-year holding / dormancy

period begins

The 30-day period expires because Phoebe did not make a deposit or withdrawal. The 1-year holding period commences during which the savings account is considered “presumptively abandoned.” Under the state, Phoebe must simply make a deposit or withdrawal during this 1-year hold period to reclaim her property.

28

February 15, 2012

1-year holding / dormancy

period ends

The 1-year holding period expires because Phoebe did not make a deposit or withdrawal. Goliath files a report with the State, informing the Controller that it has transferable, “presumptively abandoned” property. Goliath also supplies Phoebe’s contact information (which is pulled from the Bank’s 1985 records) and explains what steps it has taken to notify Phoebe (e.g., the Jan. 14 notice and unsuccessful phone call).

February 16, 2012

Goliath transfers the $1,989.40—with accrued interest of $40.17 for 2011—to the Controller. The sum is deposited in the State Treasury.

February 17, 2012

2-year custodial period begins

State’s post-

escheat notice

The Controller (1) sends written notice via certified mail to Phoebe’s off-campus address, (2) lists the property on its Website under Phoebe’s maiden surname (it did not have information regarding her married name), and (3) attempts to call Phoebe at the number Goliath provided, but the line is now disconnected.

February 24, 2012

The Controller’s written notice comes back unclaimed and unsigned. The Controller then immediately mails a written notice to Phoebe’s same, old address via regular mail. There is no response.

February 17, 2014

2-year custodial period ends

The 2-year custodial period expires because Phoebe, or Petitioner, has not filed a claim via the Website. The State takes ownership of the funds, no longer serving as mere custodian.

March 8, 2015 Gerald has audited Phoebe’s estate, which did not reveal the small savings account. He also watched the nightly news regarding the sale of the Faberge Egg, which discussed the State’s escheat Website. This prompted him to check the Website that evening, and then he discovered Phoebe’s listed savings account.

March 9, 2015 Gerald contacts Controller, who informs him that the property had already permanently escheated to the State so he could not take any action.

April 15, 2015 Petitioner joins suit in the District Court for the District of New Columbia.