Understanding Different Functions of Ward Rounds In ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Understanding Different Functions of Ward Rounds In ...

Page 1/19

Understanding Different Functions of Ward RoundsIn Paediatric Oncology: A Qualitative StudyLea P. Berndt

Hannover Medical School: Medizinische Hochschule HannoverUrs Mücke

Hannover Medical School: Medizinische Hochschule HannoverJulia Sellin

University Hospital Bonn: Universitatsklinikum BonnMartin Mücke

University Hospital Bonn: Universitatsklinikum BonnRupert Conrad

University Hospital Bonn: Universitatsklinikum BonnLorenz Grigull ( [email protected] )

University Hospital Bonn: Universitatsklinikum Bonn https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8807-2874

Research Article

Keywords: Ward round, paediatric oncology, Interviews, interdisciplinarity

Posted Date: August 13th, 2021

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-693120/v1

License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License

Page 2/19

AbstractPurpose

The ward round (WR) is a core routine for interprofessional communication and medical care planning. Itallows health care professionals (HCP) and patients to meet regularly and encourages patients to take anactive role. Despite its high value for patient-centred care, there is no universal de�nition of WR. Little isknown about the attitudes of participants towards a ‘good’ WR. This study aims to capture theexperiences and expectations of participants to better understand WR needs.

Methods

13 Semi-structured interviews were conducted with patients, parents, nurses and doctors of a paediatriconcology ward. The phenomenological framework by Colaizzi was used to identify major themes.

Results

Four major themes (MT) were identi�ed by standardised analysis of the interviews: (1) Aims andfunctions of a WR; (2) Structure and organisational requirements; (3) WR participants and interpersonalcommunication; (4) Importance of education about WR. Further analysis elucidated differentopportunities stakeholders recognised in WR, such as its role in comforting families in stressfulsituations, and relationship building. Interviewees expressed their concerns about missing structures.Families pleaded for smaller WR teams and more layperson language. HCP underscored the lack offormal education on conducting WR. Paediatric patients stated that WR scared them without properexplanation. All interviewees emphasized the need for professionalization of the WR.

Conclusion

This study gives important insights into WR in paediatric oncology. Although performed universally, WRsare poorly explored. This structured analysis reveals important expectations of WR stakeholders,stressing the need for guidelines, training, and preparation for successful WRs.

IntroductionThe ward round (WR) is an essential part of daily hospital practice where the multidisciplinary teamexchanges information and discusses further care planning [1]. Contemporarily, WR do not only takeplace in a conference room, but also at the patient’s bedside, giving patients the opportunity to askquestions and take an active role [2]. Recent research shows that besides timing and location, teamworkand communication are also of great importance for a successful WR [3].

In paediatric oncology, parents participate in the WR, which can increase the satisfaction of both theprofessional team and families [4] and shorten hospital stay [5]. While family-centred rounds havebecome standard practice on paediatric wards, they also require special communication skills [6].

Page 3/19

Additionally, the seriousness of a cancer disease and the long-lasting therapy process place signi�cantemotional stress on families, which always has to be considered during WR [7, 8].

Despite being a core routine in every hospital ward, there is no agreed de�nition of a WR [9]. In the busyday-to-day work of nurses and doctors, the WR becomes an increasingly neglected element of theirroutine [10]. It also rarely appears in textbooks and is not systematically taught at university [11]. Younghealthcare workers learn to conduct a WR ‘on the job’, without any scienti�cally proven recommendationsor standardised feedback procedures [12]. There is a fair amount of research on certain WR aspects, liketime or location, but information about participants’ attitudes and personal experiences with WR are stilllacking.

Purpose

To understand what WR means to different stakeholders of a paediatric oncology round, we conductedsemi-structured interviews with doctors, nurses, patients, and parents. We intended to capture experiencesand perceptions made by different participants and understand their expectations and requirementstowards the WR.

Thus, we aimed to create a basis for multidisciplinary accepted and scienti�cally supportedrecommendations.

MethodsFor this study, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted from January 2018 until August2019. Interviews were transcribed and analysed using a qualitative descriptive method (Colaizzi [16]; Fig.1), in order to gain a deeper understanding of the lived experience of individuals [13]. Participants werenot restricted in their input to ensure that important aspects were not missed [14].

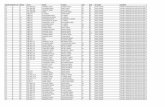

Ethics committee approval was obtained from Hannover Medical School prior to recruitment (No. 7700,05.03.2018). Inclusion criteria were: su�cient speech comprehension; participation in > 10 WR as anurse/doctor/parent/patient; age 11–18 (patients); inclusion of further interviewees until theoreticalsaturation [15]; written consent for participation. An overview of respondents is provided in Table 1.

Page 4/19

Table 1Overview of all interviewees. F = Female, M = Male, AML = Acute myeloid leukemia, ALL = Acute lymphoid

leukemiaInterview Group Sex Age

(years)Duration(min)

Work experience(years)

Patient’s disease

A Nurse M 23 27:55 1 -

B Nurse F 54 30:34 31 -

C Parent F 44 31:14 - Daughter: ALL

D Parent M 41 40:41 - Daughter: AML

E Doctor F 28 26:09 3 -

F Doctor F 32 22:02 5,5 -

G Patient M 15 07:03 - ALL

H Doctor M 28 14:07 2,5 -

I Patient F 17 12:25 - Lymphoma

J Nurse F 31 25:13 11 -

K Patient F 18 32:29 - AML

L Parent M 28 22:59 - Son: AML

M Patient M 11 10:15 - Medulloblastoma

Interviews started with a uniform beginning (“As a [nurse/doctor/parent/patient] you have alreadyexperienced several WR. In your own words, what is the meaning of the WR for you?”). For comparability,a structured part using an interview guide followed (Fig. 2). The interview guide was developedbeforehand, based on literature research, and discussed by two researchers (LB, LG) until consensus.

Each interview was analysed using the phenomenological framework by Colaizzi with respect tophenomena experienced during WR. This rigorous method is broadly accepted as an e�cient tool toextract relevant information from interviews or written text [16] and follows seven de�ned steps (see Fig.1): 1. Each interview transcript was read repeatedly. 2. Signi�cant statements were extracted andcollected in a separate analysing table. 3. Statements were then rephrased into formulated meanings and4. organised into clusters of major themes (MT). 5. Within these MT, formulated meanings were sortedinto categories and subcategories. 6. For each interview all formulated meanings within the categorieswere condensed into an essential structure. 7. Essential structures from all interviews were put togetherinto a table to enable comparison between different interviews. Table 3 shows an example of the analysisprocess.

Table 3: Example of the analysing progress from interview D (Father). Answer to the question: “Could youexplain a bit more detailed, why you restrained yourself during ward round?”

Page 5/19

Analysis was done by two authors (LB, LG) and validated by team discussions until reaching consensusand con�rmability.

ResultsA total of 13 respondents were recruited: 3 doctors; 3 nurses; 3 parents; and 4 patients. Interviews had atotal duration of 5 hours and 3 minutes with an average duration of 22 minutes 46 seconds per interview.

Page 6/19

Patients were between 11 and 18 years old, health care professionals (HCP) had between 1 and 31 yearsof work experience.

Four major themes with a total of 30 corresponding categories emerged (Table 2):

1. Aims and functions of a ward round

2. Structure and organisational requirements

3. Ward round participants and interpersonal communication

4. Importance of education about WR

Page 7/19

Table 2The four major themes and categories emerged in the analysing process, *Number of interviews, the

category appeared in out of 13 interviewsAims and functions of the ward round * Structure and organisational

requirements*

Exchange of information 11 Preparation 10

Brainstorming, joined thinking, creation ofsolutions

8 Systematic and structure 12

Making multidisciplinary agreements 8 Focus and concentration 6

WR as a paediatric consultation 9 Freedom from interruption 5

Discussion of the future 7 The right place 4

Control and revision of current status 4 A respectful working atmosphere 6

Structuring the day 5 Staff competencies 5

Emotional support 12 Time taking 7

Opportunity for families to ask questions 5

Explaining medical facts and knowledge 5 Participants and interpersonalcommunication

*

Multidisciplinary as a chance 8

Teamwork as a challenge 6

Importance of education about WR * Communication on eye-level 8

How is the WR taught? 4 Team makeup 8

How do participants learn about WR? 6 The right team size 5

WR as a learning process 9 Responsibility and job of nursing staff 5

Participation of nurses at the bedsideWR

5

Families in the WR 5

Page 8/19

Table 410 Recommendations for better ward rounds derived from the material

Ten ‚Golden Rules’ for a successful WR

RecommendationNo.

Category Recommendation

1 Prepare theward round

What documents do you need? Patient �le available? Notedown already known questions about the patient. Are thereany known concerns of the patient?

2 Create a safecommunicationspace

Introduce everyone involved to reduce anxiety. Encourage allparticipants to take an active part in the conversation. Makesure, everyone feels comfortable to ask questions or raiseconcerns.

3 Break the icesensibly

Focus the attention on the patient and his/her questions.Introduce yourself. Then start the visit with a proactivequestion about the patient's concerns. "How are you doing?"is the traditional way to open the dialogue; maybe a variationmakes sense or you try to �nd YOUR opening ritual. "Whatquestions do you have right now?", "What has changed foryou?"

4 Collectinformation

Ask speci�cally about current complaints and gatherinformation for your next steps. Be speci�c, for example, usea pain scale. Examine the patient speci�cally.

5 Deliverinformation

Convey important information. Prioritise it. Neither you northe patient can remember countless pieces of information.Clearly state: "The three most important things to me are ..."

6 Secureunderstanding

Ensure understanding with targeted questions or have themost important repeated from the patient's point of view."Can you repeat it in your own words? Then I'm sure I'veexplained it su�ciently." You may also paraphrase yourpatients words.

7 Focus on theneeds of thefamily

Clarify unanswered questions from the patient and family.

8 Use the powerof the team

Invite your team members to ask their own questions orshare observations. "Are there any open points andquestions?"

9 Plan next steps Discuss with the family the next steps that need to be taken.In terms of content, timing and reason.

10 Date reliably Will you come again today? When can you expect the resultsof the examination? How should the patient behave ifquestions arise later? Ask the patient to possibly create acollection of questions for the next visit.

All major themes (MT) and their categories are displayed in Table 2.

Page 9/19

Aims and Functions of a Ward RoundInterviewees from all four groups (11 out of 13, Table 2) named “The exchange of information” as oneimportant function of WR, including the discussion within the professional team and between HCP andfamilies. They stated, by this all participants were brought to the same level of knowledge. Exchangingknowledge initiated thinking processes and created the basis for cooperative problem solving. It alsoserved to control current health status, revise therapy plans, and reveal potential errors before theyhappen (critical incidents). Information exchange during WR had different meanings to different groups.One doctor said: “The ward round team has to manage the balancing act between: We have to get theward round done quickly and somehow just communicate medical knowledge, while always keeping inmind what the things we say actually mean to the families” (Interview F). Parents mentioned they found itdi�cult to ask questions, because they feared the meaning of the delivered information.

The category “Emotional support” was mentioned in 12 of 13 interviews, thus most frequently within thisMT. Parents explained, WR helped them to cope. Knowing their children were looked after comfortedthem. One parent said: “Because you have to face this situation. You can’t just talk it away and say: it willbe �ne and resolve itself […] and the ward round can support you doing that by saying: This is reality nowand we do our best so that everything will be �ne again” (Interview D). Patients underlined that the WRmade them feel valued and looked after as someone came to talk to them. This is illustrated by a quotefrom a patient’s interview: “It’s just nice that you are still seen by the doctors, just so they can ask you:How are you? Are you okay?” (Interview I). HCP felt more secure with regard to solving problems bysharing responsibility with their colleagues.

Nurses (3/3) and Patients (2/4) brought up the WR role in building relationship and trust. Creating a bondbetween HCP and patients made the therapy process more personal. Patients emphasized theimportance of getting to know the doctor’s character. It helped them understand the doctor’s decision-making process. A patient explained: “As a patient, you don’t have too many points of contact with thedoctors. But you nevertheless still allow them to take control over your therapy and everything else. So,you put a lot of trust in them without knowing who the person is. Who is the person that makes thosedecisions for me that I can’t make myself?” (Interview K).

Structure and organisational requirementsTwo categories named by all of the four interview groups were: “Preparation of WR” and “Clear Structureof WR”.

All interviewees wanted their co-participants to be well prepared before WR. Also, HCP expected theircolleagues to have all documents and records available. Important information should be easilyaccessible and prepared beforehand.

12 out of 13 interviewees criticized that WR proceeded unstructured, therefore “you sometimes don’tnotice certain things, you just jump to the obviously pathological results […] and then sometimes you

Page 10/19

overlook things”, as a doctor explained (Interview E). Not having a de�ned structure was also recognisedas time-consuming. Some interviewees suggested that a standardised guideline could help by de�ningthe order of topics and prioritising them.

Interviewees named a “respectful working atmosphere” as one requirement for a ‘good’ WR. They wantedWR participants to be appreciative, listen to each other, and accept people’s opinions. Every member ofthe WR team, including families, should feel they are allowed to tell their opinion openly and honestly.Families emphasised they always sensed if the healthcare staff worked as a team or not. A team workingtogether made patients and parents feel more secure.

‘Time’ was a controversial topic in the interviews. While parents and patients felt that WR was too short,doctors always talked about time pressure. They expressed the wish that WR should be effective and lesstime consuming. Interviewees from the professional team nevertheless said that it was importantplanning enough time to be able to answer all questions and go into detail if necessary. For HCPs, it wasmost important to ensure having enough time to thoroughly consider choices and make well-thought-outdecisions, as opposed to hasty ones, or even needing to postpone a relevant decision due to timepressure.

Ward round participants and interpersonal communicationInterviewees described both advantages and challenges of interprofessional teamwork in the WR.“Communication at eye-level” appeared in all interviews except for those with doctors: Parents andpatients said they would have liked more layperson language, and that the healthcare team should betteradjust communication to their emotional situation. One patient put special emphasis on non-verbalcommunication and sending signals. She described a situation experienced during WR: “To me, it lookedlike they were not sure what the results of the sample would be, or rather actually I already �gured outthat, when it takes so long to get the results, there’s a reason for that […]. The ward round team didn’tconvey any particular uncertainty, I would say, they just said: ‘we have to examine that further’. But whenyou think about it […], you will quite easily come to the conclusion that something must be abnormal”(Interview K). As the patient’s illness was serious, they interpreted the missing information as a negativesign. Excluding or trivialising information sends signals to the patient, even if the doctor doesn’t intend to,which can plunge the patient into a negative spiral of worst-case-scenarios. Patients also emphasisedthat doctors communicated through actions and facial expressions, such as looking at the clockfrequently or moving around nervously. Families got the impression that doctors had time pressure anddid not dare to ask questions anymore. One patient said: “The doctors have to go through all the otherrooms as well, […] I don’t want to delay someone like that, because I know, they need to go on” (InterviewI).

Interviewees from all four groups would have liked the psychosocial team to attend the WR to supportdecision-making and take care of questions concerning psychosocial topics. Most interviewees preferreda smaller group of people. A resident said, large WR teams made the ward round become a “show event”,which she thought was “absurd” (Interview F). A patient said: “When the senior doctor conducts the ward

Page 11/19

round, it feels as if basically everyone attends. I think there's a difference between three people standingaround your bed or �ve. You then feel like being under siege, when everyone is standing around looking atyou.” (Interview I). Other interviewees said, large groups created a less intimate atmosphere and could notassure that everyone got the required personal attention. They made patients and parents feeluncomfortable about asking questions and stop them from talking about sensitive topics.

Importance of education about WRAll HCP stated they never learned how to conduct a WR in nursing school/ university. They learned what aWR is and what to do on the job by attending and then simply copying what more experienced colleagueswere doing.

Interviewees from all four groups described how their opinions and skills changed over time, and howthat changed the WR. Professionals said they gained experience, which boosted their self-con�dence sothat they participated more actively in WR and expressed their opinion more openly. Parents underlinedthat initially they did not dare to criticise medical staff during WR. They only received information, butnever communicated their own opinion. Gaining more knowledge on the illness, they became more criticaland questioned decisions. Additionally, parents asked for a guideline to make the WR more transparent inthe beginning of the treatment. A mother said: “I would like to have an information lea�et for familiesabout the ward round before the �rst stay in hospital. That information could explain: what is the wardround, what parts does it consist of? And what should it clarify?” (Interview C). At �rst, parents oftendidn’t understand the purpose of WR and if they were allowed to ask questions.

When patients started their treatment, the WR scared them as something special and alarming. Onepatient explained: “In the beginning, you are rather intimidated when so many experts come into thebedroom” (Interview K). Another patient added: “In the beginning it’s always like, […] really terrifyinganxieties: ‘Oh my god, the doctors are coming, something really important must be going on’. And thenover time you simply learn: okay, they just want to look how you are and tell you the next steps and nottell you the next dreadful news” (Interview I). After attending a few rounds, they realised that WR werenormal daily routine.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge this is the �rst study analysing the function of WR in paediatric oncologythat considers all relevant stakeholders. Altogether we identi�ed four MT, comprising a total of 30categories. Respondents collectively stated that requirements for a successful WR were not yet standardpractice and should be implemented in daily routine.

An essential �nding was that 12 out of 13 interviewees de�ned “emotional support” as one of the mainWR functions. It even appeared more often than “handing over information” (mentioned in 11 interviews).Research shows that parents are encouraged by seeing so many different people care for their children[17], and that including families in the discussion process during WR improves the satisfaction of parents

Page 12/19

and patients [4, 18, 19]. Additionally, collecting information comforts parents of children with cancer [20].It is a coping mechanism helping people in stressful situations by reducing uncertainty and regaining asense of control [21, 22]. A recent study exploring parents’ perceptions of ward rounds highlighted thatparents highly value it primarily for the opportunity to collaborate with the clinical team and to askquestions [42].

In this study, only patients and nurses described the WR as an opportunity to build and strengthenrelationships, while neither parents nor doctors mentioned this. Patients explained that knowing theirdoctors helped them understand decisions. Decision-making is a complex process and is in�uenced bypersonal attitudes, values and beliefs [23]. Understanding how decisions are made helps patients toaccept and support the decision and improves their cooperation [24]. Another study showed that a goodpatient-doctor relationship could reduce the risk behaviour of adolescents with cancer [25]. The fact thatthis aspect was not mentioned by doctors in the present study suggests that they are not aware of thispotential.

Research shows that errors in the treatment of hospitalised children lead to prolonged hospital stays andhigher mortality [26, 27]. Sharma et al. [28] identi�ed the WR as a potential source of errors: Badcommunication can cause lost, misunderstood or unarticulated information. By contrast, goodcommunication within the team and between doctors and patients can reduce errors [29]. Poorcommunication can be attributed to the use of medical jargon, apparent time constraints and the lack ofempathic change of perspective [43]. Interviewees in our study underlined that they missed structure inverbal exchanges. Doctors raised concerns about potentially missing warning signs. As this is a uniformand global challenge, there are however �rst attempts to implement guidelines, which reduce error rates,and improve communication [28, 30].

Despite previous research suggesting open and honest communication with families, our study highlightsthat this is still lacking in practice [31, 32]. We see a need for more open communication, whereeverything is said explicitly so patients do not have to focus on non-verbal communication.

Our data shows that interviewees would prefer a member of the psychosocial team to attend the WR. Inliterature, the optimal team composition in WR is not yet de�ned and often varies [33]. Literature showsthat multidisciplinary WR achieve greater patient involvement, improved teamwork and betterconsideration of patient’s needs than multidisciplinary team meetings [34]. In paediatric oncology, lookingafter families’ psychosocial concerns can prevent noncompliance [35]. Involving members of thepsychosocial team in WR could therefore improve cancer treatment. However, when implementingmultidisciplinary rounds, team size has to be considered as our data shows that most patients andparents would prefer smaller WR teams.

Finally, our results indicate that neither professional team members nor families felt well prepared for WR.International research has already revealed that this is not only a problem in Germany, but can be foundglobally. While communication skills become more important in university education programmes, theWR is not yet part of the curriculum [11]. Recently, research has explored new WR training programmes

Page 13/19

for healthcare staff [36, 37]. It is striking that many of these are designed for medical students only,despite scienti�c agreement on teamwork and communication being signi�cant elements of WR [5].Research shows that interprofessional learning can improve both [38].

Patients of this study unveiled that emotional preparation for WR was challenging. Originally, they werescared of WR, until they understood that it is a daily routine and nothing bad happens necessarily. Thisgoes hand-in-hand with Berkwitt and Grossman’s �ndings [39], who observed that paediatric patientsassociate WR with negative feelings when starting treatment. It can therefore be assumed that healthcarestaff could spare patients anxieties and insecurity by explaining the purpose of WR early-on, which isconsistent with other studies [44].

Little is known about the relevance of different competences in speci�c disciplines. An interesting studycompared relevant competences in surgery and psychiatry by interviewing ward staff and found, notsurprisingly, that clinical skills were mentioned more often in surgical interviews, while nonverbalcommunication was described more often in psychiatric interviews [45]. However, the patients’ or therelatives’ perspectives were not considered. To ensure the best possible doctor-patient communication allrelevant perspectives have to be included, as our study demonstrates and explores.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. The interviews provided a realistic understanding of theparticipant’s experiences and covered a wide range of aspects. However, a limitation inherent toqualitative research is that results cannot easily be generalised. Nevertheless, our data can serve as abase for further research with more respondents to reach greater generalisability.

Our data represents experiences from a single institution. Experiences of members of WR on otheroncology wards may differ. However, our study focused on a multidisciplinary team, patients with severeillnesses and their families, emotional and stressful situations, and relationships between different WRmembers. These aspects can be found in other oncology wards accordingly. We therefore assume thatour results have some sort of external validity.

As we could only include interviewees who were able to speak and understand German, our resultscannot be generalised to foreign-language speakers and participants with a migratory background astheir experience might be different. Language barriers are still a huge problem in healthcare [40]. Social,cultural and religious differences are additional obstacles in the treatment of paediatric patients [41]. Asthe WR is the central place of communication, these aspects should be examined in future research.

Lastly, we included only a limited number of interviewees. Nevertheless, within this small cohort,maximum diversity was attempted to achieve representation of all major groups participating in WR,work-experience from 1 to 31 years, different genders and age variation. We stopped the recruitment ofparticipants when we reached a theoretical saturation [15].

The amount of literature regarding WR in paediatric oncology is limited, and, to our knowledge, does notcover comparing experiences of all stakeholders. Thus, this study adds substantially to the small but

Page 14/19

growing body of literature regarding WR in general and in paediatric oncology in particular.

ConclusionOur research shows that for stakeholders in in-patient paediatric cancer care, WRs have several importantfunctions, aims and potentials. In accordance with recent research attempting to de�ne a ‘good’ WR, ourresults highlight the need for improvement. Especially in terms of relationship building, emotional supportand communication, the potential of WR is not yet fully explored. Additionally, WR require guidelines toprevent errors and help the team structure discussions. Lastly, families and carers should be preparedbefore their �rst WR. The data from this study can be used to develop a successful WR training for nursesand doctors. It also gives an understanding of what a ‘good’ WR needs in order to meet the expectationsof all stakeholders and to improve the quality of cancer care.

DeclarationsAcknowledgements

We would like to thank all interviewees for their willingness to dedicate their time and contribute theirinsights to this project.

Funding: not applicable

Con�icts of interest/Competing interests: There are no con�icts of interest to declare

Ethics approval: The study was approved by local ethics

Consent to participate: All participants gave written consent before participating in interviews

Consent for publication: All authors and participants gave written consent for publication

Availability of data and material: All data are available on request

Code availability not applicable

Authors' contributions LB and LG conceptualized and conducted the study. All authors analysed data andparticipated in writing and revision of the manuscript

References1. Kirthi V et al (2012) Ward rounds in medicine: Principles for best practice. IOP RCP of London.

https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/ward-rounds-medicine-principles-best-practiceAccessed 01 November 2020

2. Mittal V et al (2010) Family-centered rounds on pediatric wards: A PRIS network survey of US andCanadian hospitalists. Pediatrics 126:37–43

Page 15/19

3. O’Hare JA (2007) Anatomy of the ward round. Eur J Intern Med 19:309–313

4. Aronson PL, Yau J, Helfaer MA, Morrison W (2009) Impact of family presence during pediatricintensive care unit rounds on the family and medical team. Pediatrics 124:1119–1125

5. Mittal V et al (2013) Pediatrics Residents’ Perspectives on Family-Centered Rounds: A QualitativeStudy at 2 Children’s Hospitals. J Grad Med Educ 5:81–87

�. Latta LC, Dick R, Parry C, Tamura GS (2008) Parental responses to involvement in rounds on apediatric inpatient unit at a teaching hospital: A qualitative study. Acad Med 83:292–297

7. Hovén E, Grönqvist H, Pöder U, von Essen L, Lindahl Norberg A (2017) Impact of a child’s cancerdisease on parents’ everyday life: a longitudinal study from Sweden. Acta Oncol 56:93–100

�. Boles J, Daniels S (2019) Researching the Experiences of Children with Cancer: Considerations forPractice. Children 6:93

9. Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE (2007) De�ning family-centered rounds. Teach LearnMed 19:319–322

10. Shankar PS (2013) Ward Rounds in Medicine. RGUHS J Med Sci 3:135–137

11. Powell N, Bruce CG, Redfern O (2015) Teaching a ‘good’ ward round. Clin Med J R Coll PhysiciansLondon 15:135–138

12. Mansell A, Uttley J, Player P, Nolan O, Jackson S (2012) Is the post-take ward round standardised?Clin Teach 9:334–337

13. Giacomini MK, Cook DJ (2000) Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research inhealth care A. Are the results of the study valid? J Am Med Assoc 284:357–362

14. Flick U (1991) Stationen des qualitativen Forschungsprozesses. In: Flick U, von Kardoff E, Keupp H,von Rosenstiel L, Wolff S (eds) Handbuch Qualitative Sozialforschung: Grundlagen, Konzepte,Methoden und Anwendungen. Eds. Beltz. Psychologie Verlags Union, Munich, pp 147–173

15. Przyborski A, Wohlrab-Sahr M (2014) Qualitative Sozialforschung. Ein Arbeitsbuch. OldenbourgWissenschaftsverlag GmbH, Munich

1�. Colaizzi PF (1978) Psychological Research as the Phenomenologists view it. Existent Altern Psychol48–71

17. Birtwistle L, Houghton JM, Rostill H (2000) A review of a surgical ward round in a large paediatrichospital: Does it achieve its aims? Med Educ 34:398–403

1�. Knoderer HM (2009) Inclusion of Parents in Pediatric Subspecialty Team Rounds: Attitudes of theFamily and Medical Team. Acad Med 84:1576–1581

19. Rappaport DI, Ketterer T, Nilforoshan V, Sharif I (2012) Family-centered rounds: Views of families,nurses, trainees, and attending physicians. Clin Pediatr 51:260–266

20. Mack JM, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC (2006) Communication about prognosis betweenparents and physicians of children with cancer: Parent preferences and the impact of prognosticinformation. J Clin Oncol 24:5265–5270

Page 16/19

21. Eheman C et al (2009) Information-seeking styles among cancer patients before and after treatmentby demographics and use of information sources. J Heal Commun 14:487–502

22. Lambert S, Loiselle C, Macdonald ME (2009) An In-depth Exploration of Information-SeekingBehavior Among Individuals With Cancer: Part 1: Understanding Differential Patterns of ActiveInformation Seeking. Cancer Nurs 32:11–23

23. Smith M, Higgs J, Ellis E (2008) Factors in�uencing clinical decision. In: Higgs J, Jensen G, Loftus S,Christensen N (eds) Clinical in the health professions. Elsevier, Munich, pp 89–100

24. Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G, Gibson F (2014) Children’s participation in shared decision-making:Children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. Eur JOncol Nurs 18:273–280

25. Phillips CR, Haase JE, Broome ME, Carpenter JS, Frankel RM (2017) Connecting with healthcareproviders at diagnosis: Adolescent/young adult cancer survivors’ perspectives. Int J Qual Stud HealthWell-being https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2017.1325699

2�. Woods D, Thomas E, Holl J, Altman S, Brennan T (2005) Adverse events and preventable adverseevents in children. Pediatrics 115:155–160

27. Slonim AD, LaFleur BJ, Ahmed W, Joseph JG (2003) Hospital-reported medical errors in children.Pediatrics 111:617–621

2�. Sharma S et al (2013) ‘Safety by DEFAULT’: Introduction and impact of a paediatric ward roundchecklist. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13055

29. Stebbing C, Wong ICK, Kaushal R, Jaffe A (2007) The role of communication in paediatric drugsafety. Arch Dis Child 92:440–445

30. Cox ED et al (2017) A family-centered rounds checklist, family engagement, and patient safety: Arandomized trial. Pediatrics https:/doi. org/10.1542/peds.2016-1688

31. DeLemos D et al (2010) Building trust through communication in the intensive care unit: HICCC.Pediatr. Crit Care Med 11:378–384

32. Zwaanswijk M, Tates K, van Dulmen S, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kamps WA, Bensing JM (2007) Youngpatients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: Results ofonline focus groups. BMC Pediatr 7:1–10

33. Walton V, Hogden A, Johnson J, Green�eld D (2016) Ward rounds, participants, roles andperceptions: literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 29:364–379

34. Monaghan J, Channell K, McDowell D, Sharma AK (2005) Improving patient and carercommunication, multidisciplinary team working and goal-setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil19:194–199

35. Spinetta JJ et al (2002) Refusal, non-compliance, and abandonment of treatment in children andadolescents with cancer: A report of the SIOP Working Committee on Phychosocial Issues inPediatric Oncology. Med Pediatr Oncol 38:114–117

Page 17/19

3�. Harvey R, Mellanby E, Dearden E, Medjoub K, Edgar S (2015) Developing non – technical ward- roundskills. Clin Teach 12:336–340

37. Thomas I (2015) Student views of stressful simulated ward rounds. Clin Teach 12:346–352

3�. Giguere A et al (2013) Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcareoutcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:4

39. Berkwitt A, Grossman M (2015) A Qualitative Analysis of Pediatric Patient Attitudes RegardingFamily-Centered Rounds. Hosp Pediatr 5:357–362

40. Jacobs E, Chen AH, Karliner LS, Agger-Gupta N, Mutha S (2006) The need for more research onlanguage barriers in health care: A proposed research agenda. Milbank Q 84:111–133

41. Pergert P, Ekblad S, Enskär K, Björk O (2007) Obstacles to transcultural caring relationships:Experiences of health care staff in pediatric oncology. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 24:314–328

42. Barrington J, Polley C, von Heerden C, Gray A (2021) Descriptive study of parents’ perceptions ofpaediatric ward rounds. Arch Dis Child

43. Reddin G, Davis N F, Mc Donald K (2019) Ward stories: lessons learned from patient perception of theward round. Ir J Med Sci 188:1119–1128

44. Walton V, Hogden A, Long JC, Johnson JK, Green�eld D (2019) Patients, health professionals, andthe health system: in�uencers on patients' participation in ward rounds. Patient PreferenceAdherence 13:1415–1429

45. Vietz E, März E, Lottspeich C, Wölfel T, Fischer M, Schmidmaier R (2019) Ward round competences insurgery and psychiatry - a comparative multidisciplinary interview study. BMC Med Educ 19:137

Figures