Twenty nevi on the arms

Transcript of Twenty nevi on the arms

Twenty nevi on the arms: a simple rule to identify patientsyounger than 50 years of age at higher risk for melanomaGiuseppe Argenzianoa, Jason Giacomeld, Iris Zalaudekb,e, Zoe Apallag,Andreas Blumh, Paola De Simonec, Aimilios Lallasa, Caterina Longoa,Elvira Moscarellaa, Danica Tiodorovic-Zivkovici, Jelica Tiodorovici,Dragan L. Jovanovici and Harald Kittlerf

Patients with a high total nevus count (TNC) merit a total-body examination, but a simple strategy to identify thesehigh-risk individuals is essentially missing. The aim of thisstudy was to investigate the correlation between thenumber of melanocytic nevi on both arms and the TNC, andto evaluate patient variables that may have an effect on thisassociation. In this multicenter, cross-sectional study, 2175patients were examined and the mean number of arm neviin relation to TNC was calculated. A mean value of less than10 arm nevi was found in patients with TNC less than 51 anda mean value of greater than 19 arm nevi was scored inpatients with TNC greater than 50. These values remainedunchanged after adjustment for various patient variables. Inrelation to TNC greater than 50, the presence of 20 or morearm nevi had specificity and negative predictive values of95.2 and 89.6%, respectively. The sensitivity was 65.5% inpatients younger than 50 years of age and 37.5% in the olderage group. The number of arm nevi was significantly higherin individuals with a history of melanoma and in those with amelanoma detected during the study period. The presenceof 20 or more nevi on the arms is an independent predictor

of a high TNC and risk of melanoma. This sign thusrepresents a simple and rapid screening tool for either theprimary care physician or the dermatologist to help identifyhigh-risk patients. European Journal of Cancer Prevention00:000–000 © 2014 Wolters Kluwer Health | LippincottWilliams & Wilkins.

European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2014, 00:000–000

Keywords: arm nevi, clinical diagnosis AQ1, melanocytic nevi, melanoma,risk factor, total nevus count

aSkin Cancer Unit, bDermatology and Skin Cancer Unit, Arcispedale Santa MariaNuova IRCCS, Reggio Emilia, cDepartment of Dermato-Oncology, San GallicanoDermatological Institute, IFO of Rome, Rome, Italy, dSkin Spectrum MedicalServices, Como, Western Australia, Australia, eDepartment of Dermatology,Medical University of Graz, Graz, fDepartment of Dermatology, Division of GeneralDermatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, gState Clinic ofDermatology, Hospital of Skin and Venereal Diseases, Thessaloniki, Greece,hPublic, Private and Teaching Practice of Dermatology, Konstanz, Germany andiClinic of Dermatovenereology Medical University of Nis, Nis, Serbia

Correspondence to Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, Skin Cancer Unit, ArcispedaleSanta Maria Nuova IRCCS, Viale Risorgimento, 80, 42100 Reggio Emilia, ItalyTel: + 39 335 415093; fax: + 39 069 762 5822; e-mail: [email protected]

Received 14 July 2013 Accepted 21 October 2013

BackgroundTotal-body skin examination (TBSE) is a recommendedmethod to facilitate early detection of melanoma, parti-cularly in high-risk patients. For example, currentAmerican Cancer Society guidelines recommend thatcancer-related screening, including skin examination, bepart of a general periodic health examination (Smith et al.,2009). However, surveys of both general practitioners(GPs) and dermatologists have shown that the majority ofrespondents do not routinely perform skin cancerscreening on their adult patients (Kirsner et al., 1999;Federman et al., 2002).

The risk of missing melanoma or nonmelanoma skincancer (NMSC) is relatively high in patients seen by GPsand dermatologists who do not routinely perform TBSE.It has been estimated that 63% of patients diagnosedwith melanoma had seen their GP in the year beforediagnosis (Geller et al., 1992). However, only 20% ofthese individuals received a physician skin cancerexamination and only 24% examined their own skinduring that time. Therefore, to improve the detection

rates of early melanoma, it appears prudent for the busyGP to be able to conveniently and rapidly identify high-risk patients for periodic skin cancer examinations (Gelleret al., 2004). Furthermore, in a previous study involvingdermatologists consulting patients with focused skinsymptoms (who would not normally receive a routineTBSE), we found that the risk of missing one malignancyif not performing TBSE was 2.17% (Argenziano et al.,2012). In that study, we examined 14 381 patients andcalculated that 47 patients needed to be examined todetect one skin malignancy and 400 patients needed tobe assessed to detect one melanoma. These results sug-gest that TBSE, and not simply a problem-focusedapproach, should at least be considered for selected,high-risk patients.

One of the strongest risk factors for melanoma is thepresence of a high number of melanocytic nevi on theentire body, especially in patients younger than 60 yearsof age (Gandini et al., 2005). These high-risk patientscertainly merit a TBSE, but in a busy clinical setting,performing a TBSE can be time consuming and

Research paper 1

0959-8278 © 2014 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins DOI: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000053

APP Template V1.03 Article id: ejcp061680

somewhat impractical, and a simple strategy to identifythese individuals is essentially missing. It has been sug-gested that the presence of 20 or more nevi on the arms isassociated with an increased risk of melanoma comparedwith patients with lower nevi counts at this anatomic site(Gandini et al., 2005; Quéreux et al., 2011). This cluemight facilitate the selection of high-risk patients whorequire a TBSE but, currently, studies of adults that linka high number of nevi on the arms with a high total nevuscount (TNC) are few in number and are of a relativelysmall sample size (English et al., 1988; Augustsson et al.,1992; Fariñas-Alvarez et al., 1999). The aims of the pre-sent study were to investigate the strength of the corre-lation between the number of nevi on both arms and theTNC in a large cohort of adult patients, and to testwhether other patient variables have an effect on thisassociation.

Materials and methodsThe study wasAQ2 designed as a multicenter, cross-sectionalstudy and approved by the ethics board of theArcispedale Santa Maria Nuova IRCCS of Reggio Emilia,Italy. Participating sites were two dermatology clinics(Nis, Serbia; and Thessaloniki, Greece) and two specia-lized pigmented lesion clinics (Reggio Emilia and Rome,Italy) affiliated with academic institutions, and one der-matology private practice (Konstanz, Germany).

During a period of 4 months (February–May 2012), allconsecutive patients seeking a dermatologic consultationwere considered for recruitment. Failure to providewritten informed consent was the only exclusion criter-ion. We used an electronic data sheet to record patientdata, which consisted of age, sex, reason for consultation,skin phototype (according to the Fitzpatrick classifica-tion), history of sunburns before the age of 20 years,personal and family history of melanoma and/or NMSC,number of nevi on both arms (i.e. including both com-mon and ‘atypical’ nevi, size > 2 mm, excluding frecklesor lentigines), TNC (0–10, 11–50, 51–100, and > 100nevi), and presence of freckles or lentigines. After patientexamination (performed by a dermatologist), lesionssuggestive of melanoma or NMSC were excised orbiopsied. The histopathologic diagnosis was recorded foreach of the biopsied or excised lesions.

Absolute numbers and percentages of the patient vari-ables were calculated. Continuous variables are given asmean and the SD unless otherwise specified. Analysis ofvariance was used for the calculation of adjusted means ofarm nevus counts per TNC by adding age, sex, reason forconsultation, skin phototype, and presence of freckles ascovariates. We used χ2-tests for the comparison of pro-portions. A logistic regression analysis was used formultivariable analysis. All given P-values are two-tailed,and a P-value less than 0.05 indicates statisticalsignificance.

ResultsGeneral dataDuring a period of 4 months, 2175 patients were recrui-ted in five centers in Italy, Germany, Greece, and Serbia.The mean age of the patients was 44.6 years (SD17.2 years), and 1215 (55.9%) were women. About two-third (N= 1440, 66.2%) of the study patients soughtconsultation for a skin tumor check, followed by 453(20.8%) patients consulting for an inflammatory orinfectious skin disease, and 282 (13%) patients for otherskin disorders. Most patients had skin phototype III(N= 978, 45%) or II (N= 934, 42.9%), followed by skintype IV (N= 138, 6.3%) and I (N= 125, 5.7%). A greaterproportion of fair-skinned patients (skin type I and II)were recruited in Germany and Serbia (61.5%) comparedwith patients from Italy and Greece, where patients withskin type III and IV were slightly prevalent (58.8%). In AQ3

all, 275 (12.6%) and 158 (7.3%) patients reported a per-sonal history of melanoma or NMSC, respectively, and120 (5.5%) and 141 (6.5%) patients reported a familyhistory of melanoma or NMSC, respectively. A personalhistory of melanoma was more frequently reported bypatients recruited in pigmented lesion clinics than ingeneral dermatology clinics (23.2 vs. 5.5%).

Prediction of the total nevus count by number of armneviAs shown in Fig. 1, an increasing number of nevi on botharms was associated with a higher TNC. A mean value ofless than 10 arm nevi was found in patients with TNCless than 51 and a mean value of more than 19 arm neviwas scored in patients with TNC greater than 50. Thesemean values remained almost unchanged after adjust-ment for age, sex, reason for consultation, skin phototype,

Fig. 1

120

100

80

60 ∗

∗∗∗∗

∗

∗

40

20

00−10 11−15 51−100 >100

Total number of nevi

Num

ber o

f nev

i on

the

arm

s (n

)

Melanocytic nevi. Box plot showing the number of arm nevi according tothe total nevus count for 2175 patients. Thick horizontal lines withinboxes indicate median values. Lower and upper limits of the boxesindicate the 25th to 75th percentiles, upper bars indicate the 90thpercentiles, and the lower bar indicates the 10th percentile. Outliers aremarked with open circles and extreme outlier/s with asterisks.

2 European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2014, Vol 00 No 00

presence of freckles or lentigines, and recruiting center(Table 1).

In relation to a TNC of more than 50 nevi [a commonthreshold to distinguish high-risk from moderate-risk tolow-risk patients (Holly et al., 1987)], the presence of 20or more arm nevi had sensitivity and specificity values of59.8 and 95.2%, respectively, with positive and negativepredictive values of 77.6 and 89.6%, respectively(Table 2).

When subdividing patients into two groups aged below51 years and above 50 years, remarkable differences werefound in terms of TNC and arm nevi. Patients in theyounger age group had a TNC greater than 50 morefrequently (374 of 1424 patients, 26.3%) compared withpatients in the older age group (96 of 751 patients,12.8%), and more frequently had greater than 19 arm nevi(21.8% of patients) compared with older patients (6.8% ofpatients). As shown in Table 3, the mean number of armnevi was higher than 20 in the younger age group withTNC greater than 50, whereas it was constantly below 20in the older age group, independent of the TNC. Thesensitivity of the 20 nevi rule for TNC greater than 50was 65.5% in the younger age group and 37.5% in theolder age group, with a specificity of 93.7 and 97.7%,respectively.

Number of arm nevi and history of skin malignanciesThe number of nevi on the arms was significantly asso-ciated with a history of melanoma. The mean number ofarm nevi in individuals with a personal history ofmelanoma was 13 (SD 15) and significantly higher thanthat in individuals without a history of melanoma, whohad a mean of nine nevi (SD 11; P< 0.001). In the

univariable analysis, 19.2% of patients with skin type Ihad a history of melanoma in comparison with 15.7% withskin type II, 10.1% with skin type III, and 5.6% with skintype IV (P< 0.001). Individuals with freckles (n= 1252)had a personal history of melanoma in 23.0% (n= 208)compared with 5.0% (n= 63) of 903 individuals withoutfreckles (P< 0.001). Of 1079 individuals who reported tohave a least one sunburn before the age of 20, 17.9%(n= 193) had a personal history of melanoma comparedwith 7.2% (n= 78) of 1089 individuals who reported nosunburns (P< 0.001). Patients with a personal history ofmelanoma were significantly older than patients withouta personal history of melanoma (52 ± 15 vs. 43 ± 17 years;P< 0.001). Other factors (sex and family history ofmelanoma) were not associated with a personal history ofmelanoma in the univariable analysis. In a multivariableanalysis (Table 4), the number of nevi on the arms wassignificantly and independently associated with a historyof melanoma after controlling for potential confounders.The number of nevi on the arms was not associated witha history of NMSC (data not shown).

Number of arm nevi and skin malignancies detectedduring the study periodAfter TBSE, 318 suspicious lesions were excised orbiopsied, with histopathologic examination indicating 39

Table 1 Adjusted and unadjusted mean number of nevi on thearms according to the total nevus count

Totalnevuscount Patients (n)

Arm nevi(mean,

unadjusted) 95% CI

Arm nevi(mean,

adjusteda) 95% CI

0–10 889 2.5 2.3–2.8 2.8 2.2–3.311–50 816 8.8 8.3–9.2 8.5 7.9–9.151–100 287 19.9 18.5–21.4 19.8 18.8–20.8>100 183 26.9 24.2–29.5 27.0 25.8–28.2

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CI, confidence interval.aNumbers are adjusted for age, sex, reason for consultation, skin phototype,presence of freckles, and recruiting center.P-value for difference between groups <0.001 (ANOVA).

Table 2 Number of arm nevi in relation to total nevus count and agegroups (values refer to the number of patients)

Arm nevi<20 [n (%)] Arm nevi>19 [n (%)]

TNC<51 nevi (n=1705) 1624 (95.2) 81 (4.8)TNC>50 nevi (n=470) 189 (40.2) 281 (59.8)Age<51 years (n=1424) 1113 (78.2) 311 (21.8)Age>50 years (n=751) 700 (93.2) 51 (6.8)

TNC, total nevus count.

Table 3 Mean number of nevi on the arms according to the totalnevus count in different age groups

Total nevuscount

Age group(years)

Mean number ofarm nevi (median)

95% CI ofmean

25–75%percentile

0–10 <51 3.2 (2) 2.8–3.6 1–4>50 1.8 (1) 1.5–2.0 0–3

11–50 <51 9.9 (8) 9.3–10.4 5–13>50 5.9 (4) 5.1–6.8 1–8

51–100 <51 21.7 (22) 20.1–23.3 13–28>50 13.3 (7) 10.4–16.1 4–24.75

>100 <51 29.5 (26) 26.5–32.5 17.5–37.5>50 16.1 (13) 12.3–19.9 7–24.75

CI, confidence interval.

Table 4 Multivariate analysis of predictors of personal history ofmelanoma AQ4

Odds ratio (95% CI) P-value

Age<30 1.00 <0.00130–49 3.20 (1.82–5.65) <0.00150–69 4.68 (2.60–8.41) <0.001≥70 6.20 (3.27–11.76) <0.001

History of sunburns 0.94 (0.65–1.35) 0.72Skin typeI 1.00 0.51II 0.95 (0.57–1.59) 0.85III 0.95 (0.55–1.63) 0.85IV 0.50 (0.18–1.43) 0.20

Freckles or lentigines 4.34 (3.00–6.27) <0.001Nevi on the arms0–19 1.00≥20 2.14 (1.53–2.99) <0.001

Family history of melanoma 1.10 (0.64–1.87) 0.74

CI, confidence interval.

20 nevi rule Argenziano et al. 3

melanomas, 140 NMSC, and 139 benign lesions. Thenumber of nevi on the arms was associated significantlywith a melanoma detected during the study period. Themean number of arm nevi in the 39 individuals withexcised melanoma was 16 (SD 12) and significantlyhigher than that in individuals without a history ofmelanoma, who had a mean of nine (SD 11; P< 0.001). Inthe univariable analysis, all other factors (age, sex, per-sonal history of melanoma, family history of melanoma,freckling, and skin type) were not significantly associatedwith a melanoma detected during the study period. In amultivariable analysis (Table 5), the number of nevi onthe arms remained the only variable that was associatedsignificantly with the diagnosis of melanoma. The num-ber of nevi on the arms was not associated significantlywith a NMSC detected during the study period (data notshown).

DiscussionThe development of an accurate, simple, and practicalmethod for the identification of high-risk patients formelanoma has the potential to improve physicians’motivation to perform TBSE or refer patients for TBSE.This may translate into the detection of thinner mela-nomas, which is currently the only strategy to decreasemelanoma mortality (Epstein et al., 1999; Brady et al.,2000; Richard et al., 2000; McPherson et al., 2006; Peuvrelet al., 2009; Aitken et al., 2010; McGuire et al., 2011).

The 20 nevi on the arms rule can be considered a quick,simple, and accurate method for identification of high-risk patients. First, it involves a convenient and fastexamination of a portion of the body that is frequentlyuncovered and easily inspected. Second, calculation ofarm nevi does not require special expertise as it consistsof simply counting the number of moles that are largerthan 2 mm and that do not resemble a freckle or solarlentigo. As such, an accurate count can be performed byeither the GP or the dermatologist, and an approximate

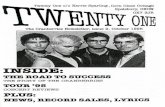

count might even be carried out by the patient as self-screening (Quéreux et al., 2011). Third, in our studyinvolving a relatively large sample size of patients, therule was predictive of a high TNC, which is one of thestrongest risk factors for melanoma (Fig. 2) (Holman andArmstrong, 1984; Grob et al., 1990; Garbe et al., 1994;Gandini et al., 2005; Rhodes, 2006; MacKie et al., 2009;Stratigos and Katsambas, 2009).

As largely expected by the different melanoma risk pro-files in different age groups, the 20 nevi rule appears toapply more specifically to patients younger than 50 yearsof age. In the latter age group, this sign had 65.5% sen-sitivity for TNC greater than 50, compared with only37.5% sensitivity in the older age group. Overall, thespecificity and the negative predictive value of the 20nevi sign were 95.2 and 89.6%, respectively. This meansthat only about 5% of low-risk patients (TNC< 50) werefound to be falsely positive for the 20 nevi sign and about10% of patients negative for the 20 nevi sign were high-risk patients (TNC> 50).

The association of numerous arm nevi and increased riskof melanoma has been reported in a number of studies.For example, Holman and Armstrong reported anincreased risk of melanoma for patients with numerouspalpable nevi on the arms compared with patients withno palpable nevi at this site. In their study, a count of 5–9nevi was associated with a four-fold higher risk ofmelanoma, and a count of 10 or more nevi was associatedwith an 11-fold risk (Holman and Armstrong, 1984). Grobet al. (1990) found that the presence of four or more nevion one forearm (i.e. left side) was associated with anapproximately two-fold greater risk for melanoma com-pared with patients with no nevi at this anatomical site.The association of more than 20 nevi on the arms andincreased risk of melanoma in patients aged younger than60 years has also been reported recently in a case–controlstudy testing three methods for scoring the risk ofmelanoma (Quéreux et al., 2011). Comparably, in a mul-tivariable model that also included age, skin type, historyof sunburns, freckling, and family history for melanoma,we found that the number of nevi on the arms was sig-nificantly higher and independently associated withindividuals with a history of melanoma (as reported bythe patient, but not verified) and with individuals with amelanoma detected during the study period.

The 20 nevi rule can thus be generally considered asimple screening tool to detect high-risk melanomapatients younger than 50 years of age. However, theseresults appear to differ for older patients. In a previousstudy assessing the risk of missing a skin cancer if TBSEwas not performed, we found several factors to be asso-ciated significantly with the risk of melanoma(Argenziano et al., 2012). Among these, older age per sewas associated with increased risk. Overall, we calculatedthat 400 patients need to be examined to detect one

Table 5 Multivariate analysis of predictors of melanoma diagnosisduring the study period

Odds ratio (95% CI) P-value

Age<30 1.00 0.1230–49 1.15 (0.46–2.88) 0.7750–69 3.13 (0.37–3.41) 0.83≥70 3.36 (1.07–10.55) 0.04

History of sunburns 1.82 (0.82–4.04) 0.14Skin typeI 1.00 0.85II 0.84 (0.24–2.97) 0.79III 1.15 (0.31–4.23) 0.83IV NA NA

Freckles or lentigines 0.91 (0.44–1.90) 0.80Nevi on the arms0–19 1.00≥20 6.49 (3.20–13.18) <0.001

Family history of melanoma 0.71 (0.16–3.09) 0.65

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

4 European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2014, Vol 00 No 00

melanoma, but this figure was reduced to only about 200patients in the age group of more than 60 years. Otherassociated factors included a history of previous NMSC,fair skin type, the presence of an equivocal lesion on aproblem or uncovered area, but not the number of nevi.These results suggest that risk factors for melanoma varywith age. In effect, two different age-related groups ofhigh-risk melanoma patients can be identified: the first,where the risk of melanoma is related to the number ofnevi (i.e. in younger patients, <50 years) and the secondwhere the risk of melanoma is associated with evidenceof chronic sun-damaged skin (i.e. older patients). Thus,we recommend performing a TBSE on patients olderthan 50 years who have chronically sun-damaged skin onuncovered areas (i.e. dermatoheliosis, with numeroussolar lentigines and/or actinic keratoses). The latterrepresents a fast and simple guide to detect high-riskpatients in this age group, but this needs confirmation byfurther studies.

A limitation of our study might be related to the fact thatpatients were included from dermatology and pigmentedlesion clinics in Europe. As these patients had a reason tovisit a dermatology clinic, they may have had more neviand a higher prevalence of melanoma than patients vis-iting a general clinical practice. The results of this studymay therefore not be generalizable to all clinicalsituations.

ConclusionFor patients younger than 50 years old, the presence of20 or more nevi on the arms is an independent predictorof a high TNC and risk of melanoma. It thus represents a

simple and rapid screening tool for either the primarycare physician or the dermatologist to help identify high-risk patients to be examined by TBSE.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported in part by the Italian Ministryof Health (RF-2010-2316524).

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

ReferencesAitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, Youl P, English D (2010). Clinical whole AQ5-body

skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer126:450–458.

Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Bakos RM, Bergman W,Blum A, et al. (2012). Total body skin examination for skin cancer screeningin patients with focused symptoms. J Am Acad Dermatol 66:212–219.

Augustsson A, Stierner U, Rosdahl I, Suurküla M (1992). Regional distributionof melanocytic naevi in relation to sun exposure, and site-specific countspredicting total number of naevi. Acta Derm Venereol 72:123–127.

Brady MS, Oliveria SA, Christos PJ, Berwick M, Coit DG, Katz J, Halpern AC(2000). Patterns of detection in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Cancer89:342–347.

English JS, Swerdlow AJ, MacKie RM, O’Doherty CJ, Hunter JA, Clark J,Hole DJ (1988). Site-specific melanocytic naevus counts as predictors ofwhole body naevi. Br J Dermatol 118:641–644.

Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, Mofid M, Koch SE (1999). Is physiciandetection associated with thinner melanomas? JAMA 281:640–643.

Fariñas-Alvarez C, Ródenas JM, Herranz MT, Delgado-Rodríguez M (1999). Thenaevus count on the arms as a predictor of the number of melanocyticnaevi on the whole body. Br J Dermatol 140:457–462.

Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Kirsner RS (2002). Skin cancer screening by der-matologists: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol 46:710–714.

Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini P, Abeni D, Boyle P, Melchi CF(2005). Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: I. Commonand atypical naevi. Eur J Cancer 41:28–44.

Garbe C, Büttner P, Weiss J, Soyer HP, Stocker U, Krüger S, et al. (1994).Associated factors in the prevalence of more than 50 common melanocyticnevi, atypical melanocytic nevi, and actinic lentigines: multicenter

Fig. 2

Melanocytic nevi. A 38-year-old man with more than 20 nevi on the arms and a total nevus count of more than 50 nevi.

20 nevi rule Argenziano et al. 5

case–control study of the Central Malignant Melanoma Registry of theGerman Dermatological Society. J Invest Dermatol 102:700–705.

Geller AC, Koh HK, Miller DR, Clapp RW, Mercer MB, Lew RA (1992). Use ofhealth services before the diagnosis of melanoma: implications for earlydetection and screening. J Gen Intern Med 7:154–157.

Geller AC, O’Riordan DL, Oliveria SA, Valvo S, Teich M, Halpern AC (2004).Overcoming obstacles to skin cancer examinations and prevention counsel-ing for high-risk patients: results of a national survey of primary care physi-cians. J Am Board Fam Pract 17:416–423.

Grob JJ, Gouvernet J, Aymar D, Mostaque A, Romano MH, Collet AM, et al.(1990). Count of benign melanocytic nevi as a major indicator of risk fornonfamilial nodular and superficial spreading melanoma. Cancer66:387–395.

Holly EA, Kelly JW, Shpall SN, Chiu SH (1987). Number of melanocytic nevi asa major risk factor for malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol17:459–468.

Holman CD, Armstrong BK (1984). Pigmentary traits, ethnic origin, benign nevi,and family history as risk factors for cutaneous malignant melanoma. J NatlCancer Inst 72:257–266.

Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG (1999). Skin cancer screening in pri-mary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol 41:564–566.

MacKie RM, Hauschild A, Eggermont AMM (2009). Epidemiology of invasivecutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol 20 (Suppl 6):vi1–vi7.

McGuire ST, Secrest AM, Andrulonis R, Ferris LK (2011). Surveillance ofpatients for early detection of melanoma: patterns in dermatologist vspatient discovery. Arch Dermatol 147:673–678.

McPherson M, Elwood M, English DR, Baade PD, Youl PH, Aitken JF (2006).Presentation and detection of invasive melanoma in a high-risk population.J Am Acad Dermatol 54:783–792.

Peuvrel L, Quéreux G, Jumbou O, Sassolas B, Lequeux Y, Dreno B (2009).Impact of a campaign to train general practitioners in screening for melan-oma. Eur J Cancer Prev 18:225–229.

Quéreux G, Moyse D, Lequeux Y, Jumbou O, Brocard A, Antonioli D, et al.(2011). Development of an individual score for melanoma risk. Eur JCancer Prev 20:217–224.

Rhodes AR (2006). Cutaneous melanoma and intervention strategies to reducetumor-related mortality: what we know, what we don’t know, and what wethink we know that isn’t so. Dermatol Ther 19:50–69.

Richard MA, Grob JJ, Avril MF, Delaunay M, Gouvernet J, Wolkenstein P, et al.(2000). Delays in diagnosis and melanoma prognosis (I): the role ofpatients. Int J Cancer 89:271–279.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW (2009). Cancer screening in the UnitedStates, 2009: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines andissues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 59:27–41.

Stratigos AJ, Katsambas AD (2009). The value of screening in melanoma. ClinDermatol 27:10–25.

6 European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2014, Vol 00 No 00

AUTHOR QUERY FORM

LIPPINCOTTWILLIAMS AND WILKINS

JOURNAL NAME: CEJ

ARTICLE NO: ejcp061680

QUERIES AND / OR REMARKS

QUERY NO. Details Required Author's Response

Q1 The keyword ‘clinical diagnosis’ is not used in the text. Please checkand replace with new keywords (3 to 10 keywords).

Q2 Please check and confirm whether the change of section title from‘Methods’ to ‘Materials and methods’ as per the journal style is OK.

Q3 The meaning of the sentence ‘A greater proportion of fair-skinnedpatients..........’ is not clear. Please rephrase it for clarity.

Q4 Please check and confirm whether the changes made to the P-valuesfor Tables 4 and 5 are OK.

Q5 References have been validated using PubMed. Hence, pleaseconfirm whether the insertion of missing elements for all journalreferences is OK.