Tuan Guru, community and conflict in Lombok, Indonesia

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Tuan Guru, community and conflict in Lombok, Indonesia

Tuan Guru, community and conflict in Lombok, Indonesia

Jeremy Kingsley

Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

August 2010

Melbourne Law School The University of Melbourne

iii

Abstract

Violence is an ongoing issue of concern in Indonesia. Recent periods of political,

social and economic instability have seen outbreaks of violence across the

archipelago, often between rival religious or ethnic groups. This has also been the

case on the eastern Indonesian island of Lombok, which has both an ethnically and

religiously diverse population. Lombok’s capital, Mataram, and the surrounding area

of West Lombok form the focus of the field research for this thesis. Both have a

Muslim majority and large Christian and Hindu minority communities. This religious

and cultural diversity has at times been a source of tension.

This thesis explores two local communities in Mataram and West Lombok, as well as

looking more broadly at Mataram during provincial elections. The research examines

not only communal and political tensions that arose in these communities, but also

how conflict was successfully avoided or resolved. This thesis argues that

partnerships between state and non-state actors and institutions are integral to conflict

management. This cooperation is of particular importance given the relative weakness

of state institutions in Lombok, including the police and courts. Therefore, the value

of local communities and non-state actors in conflict avoidance and resolution cannot

be underestimated.

Local religious leaders, Tuan Guru, are key non-state actors who are essential to

conflict management processes in Lombok. Tuan Guru have a high degree of

influence in pious Lombok society. This means that they are able to act as social

stabilisers and mediators during periods of tension in local communities.

This thesis also points to the localised nature of dispute resolution, as highlighted in

case studies of conflict avoidance during the 2008 NTB gubernatorial elections and

dispute resolution in the West Lombok village that I have named ‘Bok’. These cases

demonstrate that social relationships both within and between communities, adat

(customary practices) and local leadership all play vital roles in resolving tensions and

protecting citizens from the effects of violence. Of particular importance are good

social relations, the absence of which can lead ethnic minorities to become

iv

marginalised and alienated from the rest of the community. Without strong social

relationships, minorities are vulnerable to violence should tensions arise.

This thesis demonstrates that conflict management in Mataram and West Lombok,

whether it be during local provincial elections or within a local community, is an

intricate process. Rather than creating ‘one-size fits all’ solutions, conflict

management in the highly localised context of Lombok draws upon local legal

culture(s) that offer a range of social and legal tools. These include drawing upon

sources of locally relevant authority, both state and non-state, such as religious

leaders, public servants and the police. Working together, these groups can assist in

facilitating community solutions to avoid or resolve conflict. The actors involved and

approaches used will differ from community-to-community and depend upon the

circumstance, but in most cases Tuan Guru are key to the outcome.

v

Declaration

This is to certify that

i. the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD,

ii. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used,

iii. the thesis is less than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps,

bibliographies and appendices.

Signed: Dated:

vi

Acknowledgements

Writing a doctoral thesis is like the Tour de France. In many ways it is a very

individual activity, but without the encouragement, strategic guidance and support of

one’s riding team, no cyclist can take on the mountains and successfully complete the

event. I could not have sustained this four year journey alone. There are many people

whose assistance, love, guidance and encouragement has kept me going.

Throughout this journey, including my frequent and lengthy travels far from home,

one constant has been my family’s support. My parents’ patience and understanding

(despite often finding my trajectory in life perplexing) is something that I cherish.

Yotti, Ruthie, Ryan and little Daniel your love, support and technical assistance has

sustained me. Thanks must also be extended to my larger family, the Gonns, Platts

and Pressers. You have all created a warm and laughter-filled world for me.

My research was assisted by several university students in Mataram, whose expertise

and knowledge I relied upon everyday in Lombok. We learned together and they have

seen me at my best and worst. These four fantastic assistants were Zey Sahnan,

Herawati, Nurmala Fahriyanti and Muhammad Dimiati. My local sponsor, Bapak H.

Asnawi, and the staff and students of the State Islamic University of Mataram made

me feel welcome and at home from my first day on campus.

Life is about family and friends. In Lombok, I had the privilege of making some

wonderful friends, including Lalu Nurtaat, Kartini, Abdul Wahid, Atun Wadatun and

Mohammad Abdun Nasir. Your generosity of spirit and friendship during my time in

Mataram made life so much easier and more enjoyable. While in Lombok my family

in Kampung Lom provided me with a generosity that enriched my experience

exponentially. They became my second family. Their joy and tears gave this outsider

a glimpse of what Lombok is really about.

My principal supervisor, Tim Lindsey, helped me start this crazy venture and has

been there every step of the way. Whether it was our meetings in Jakarta or his ‘tough

love’ in Melbourne, his support and mentorship is more than appreciated. My two

vii

other supervisors, Abdullah Saeed and Michael Feener, have encouraged me along

this lengthy journey. I am thankful for their critical feedback and wisdom.

During my studies many people at the Asian Law Centre, Centre for Islamic Law and

Society and the Melbourne Law School have been there for me too. I would like to

make particular mention of Dina Afrianty, Melissa Crouch, Denny Indrayana, Quan

Nguyen, Helen Pausacker, Arskal Salim and Kerstin Steiner. Watching these scholars

take on their doctoral studies has been an inspiration.

The task of completing a thesis is an academic exercise, but with many administrative

hurdles. As a consequence, I would also like to thank several staff of the Melbourne

Law School Research Office and Asian Law Centre, particularly Kathryn Taylor,

Kelly McDermott, Jessica Cotton and Lucy O’Brien. They fielded my million and one

questions, often asked from thousands of kilometres away.

I was financially supported in my doctoral studies and field research by Tim

Lindsey’s ARC Federation Fellowship for a Doctoral Scholarship, an Endeavour

Australia Cheung Kong Fellowship, a Melbourne University Travelling Abroad

Scholarship, a Melbourne University Asia Fieldwork Scholarship, a Melbourne Law

School Research Support Fund Grant and the Bernard Lustig Scholarship. For this

generous support I am grateful.

Before leaving for the field, Tim Lindsey told me, almost tauntingly, that Indonesia is

addictive. I refused to believe him – I was no sentimentalist! This turned out to be one

of the many assumptions that was proven wrong while living in Lombok. As it turned

out, I was deeply affected. I remember going to the bathroom on the flight from

Lombok to Singapore at the end of my field research locking the door and then

crying… was it joy, relief or sorrow? The answer is that it was a cocktail of these

emotions. Whatever the case, Lombok and Indonesia are now part of me.

My final note of appreciation is the most important. I am lucky to have met my

partner in life, Maria Platt. We have done our doctoral studies in parallel, spending

over a year in the field together. From this experience we have come out stronger!

Maria, I would not have been able to complete this thesis without you.

viii

Table of contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................ iii

Declaration.....................................................................................................................v

Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................vi

Table of contents........................................................................................................ viii

List of tables, figures and illustrations...........................................................................x

Currency.......................................................................................................................xii

Photographs..................................................................................................................xii

Glossary ..................................................................................................................... xiii

Chapter 1 Weak state, strong communities?.............................................................1

Situating this research ...............................................................................................6

Weak state, strong communities?.............................................................................12

Interpreting Lombok society and legal structures – A view from outside ...............18

Chaotic harmony in difficult circumstances ............................................................26

Conclusion ...............................................................................................................31

Chapter 2 The troubled transition ...........................................................................33

The law enforcement void ........................................................................................35

Power shifts local.....................................................................................................46

Community responses to crime ................................................................................50

The economics of violence .......................................................................................58

The January riots – More than burning tyres..........................................................63

Conclusion ...............................................................................................................72

Chapter 3 Tuan Guru – guardians of religious traditions......................................75

Who are Tuan Guru?................................................................................................78

The historical emergence of Tuan Guru..................................................................94

Locating religion in Lombok....................................................................................98

Embedded power....................................................................................................109

Guardians of religious traditions – The key to social stabilisation.......................119

Conclusion .............................................................................................................125

Chapter 4 Adat, leadership and community ..........................................................129

Lom – Unity in diversity?.......................................................................................132

Adat – Lore of the local .........................................................................................139

Local leadership.....................................................................................................143

Communal relationships – The importance of mutual benefit...............................148

A time of riots – Testing a community’s resolve ....................................................154

Local security measures – Paid ronda and pamswakarsa.....................................158

Conclusion .............................................................................................................165

ix

Chapter 5 The art of conflict management............................................................167

Avoiding and resolving conflict .............................................................................167

Case study – provincial elections and the power of partnerships .........................169

Ethnic tensions and political violence in Lombok ......................................169

Political and religious cooperation ............................................................174

Implementation of conflict management.....................................................181

Case Study – Testing times in Bok .........................................................................186

The pressures of leadership ........................................................................186

Local political rivalries...............................................................................190

The temperature continues to rise...............................................................192

Powerful negotiations .................................................................................196

Conclusion .............................................................................................................200

Chapter 6 Chaotic harmony ...................................................................................203

The crux of conflict management...........................................................................205

Bibliography ..............................................................................................................209

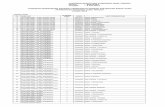

Appendix 1 – Court data............................................................................................235

x

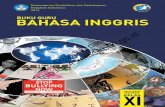

List of tables, figures and illustrations Picture 1.1 An idul fitri parade ......................................................................................3

Picture 1.2 Scaffolding outside the front of Santa Maria Immaculate...........................4

Picture 1.3 The altar of Santa Maria Immaculate ..........................................................4

Picture 1.4 Santa Maria Immaculate during renovations...............................................4

Picture 1.5 Hindu celebrations in early 2007.................................................................8

Picture 1.6 A joget in Mataram....................................................................................10

Picture 1.7 Former NTB Governor, Lalu Serinata.......................................................28

Picture 2.1 A Mataram police station ..........................................................................37

Picture 2.2 The Magistrates Court in Mataram............................................................43

Picture 2.3 Amphibi post in central Mataram...............................................................45

Picture 2.4 A member of pamswakarsa, Satgas..........................................................57

Picture 2.5 Governor TGH Bajang and Deputy Governor Badrul Munir....................62

Picture 2.6 An anti-violence billboard .........................................................................70

Picture 3.1 Pondok Pesantren Abhariyah....................................................................75

Picture 3.2 TGH Sofwan Hakim..................................................................................81

Picture 3.3 TGH Mustiadi Abhar.................................................................................82

Picture 3.4 TGH Abdul Hamid ....................................................................................82

Picture 3.5 TGH Ulul Azmi .........................................................................................83

Picture 3.6 Pondok Pesantren Nurul Hakim................................................................89

Picture 3.7 TGH Subkhi Sasaki ...................................................................................91

Picture 3.8 A Mataram Mosque.................................................................................100

Picture 3.9 Pengajian in Memben, East Lombok......................................................102

Picture 3.10 Minaret in Jerneng, West Lombok ........................................................112

Picture 3.11 Crowds at an NW Pancor anniversary rally ..........................................113

Picture 3.12 TGH Bajang addressing the NW Pancor anniversary ...........................118

Picture 4.1 Komplek Lom..........................................................................................133

Picture 4.2 Komplek Lom..........................................................................................133

Picture 4.3 Kampung Lom.........................................................................................134

Picture 4.4 Kampung Lom.........................................................................................134

Picture 4.5 Common area in Lom..............................................................................136

Picture 4.6 Multi-purpose area in Lom......................................................................149

Picture 4.7 Komplek Cina Lom .................................................................................153

Picture 4.8 Kampung Lom’s musholla......................................................................157

Picture 4.9 Kampung Lom resident in Amphibi uniform...........................................162

Picture 4.10 Kampung Lom resident in Lang-Lang uniform ....................................162

Picture 4.11 Amphibi identity card.............................................................................163

xi

Picture 4.12 View of Lom from the fields .................................................................165

Picture 5.1 Gubernatorial campaign material ............................................................173

Picture 5.2 Polling booths in Mataram ......................................................................184

Picture 5.3 Bajang-Munir Posters ..............................................................................186

Picture 5.4 A sporting tournament in Bok .................................................................198

Picture 5.5 Santri at Pondok Pesantren Nurul Hakim...............................................201

Picture 6.1 A nyongkolan...........................................................................................204

Map 1.1 Indonesia, with Lombok circled ......................................................................7

Map 1.2 Lombok, with Mataram and West Lombok circled.........................................7

Map 4.1 Lom..............................................................................................................131

Table 2.1 Traffic-related matters lodged in the Magistrates Court Mataram. .............43

Table 3.1 Religious leadership in Bok.........................................................................81

Table 4.1 NTB government structure – 2008 ............................................................146

xii

Currency

At the time of undertaking the field research during 2007-2008, one Australian dollar

($AU) equalled approximately 8000 Indonesian Rupiah (Rp). Therefore, this will be

the exchange rate used throughout this thesis.

Photographs

All photographs used in this thesis were taken by the author while undertaking field

research in Lombok, Indonesia, in 2007-2008.

xiii

Glossary

All Indonesian and Sasak words are indicated through the use of italics throughout

this thesis, except for place names. Sasak words are further denoted by the letter (S) in

this glossary. Words of Arabic origin which are in common usage in the Indonesian

language are not denoted with a specific marker.

abangan Indonesians who are nominally Muslim but also

observe aspects of adat and other cultural traditions

adat local custom and social expectations, akin to local rules

agama religion

akidah belief, faith

Aliansi Masyrakat Adat Nasional (AMAN)

National Alliance for Adat Societies – the word ‘aman’ means safety

Amphibi the name of the largest of Lombok’s pamswakarsa.

Bahasa Sasak Sasak language

berugaq (S) a traditional pavillion/sitting platform used for socialising

Bintara Pembina Desa (Babinsa)

military liaison officer in Indonesian villages

Babinmaspol police liaison officer in Indonesian villages

Bujak a pamswakarsa that is no longer active in Mataram and West Lombok.

Bupati Regent, Head of Regency

dakwah Islamic outreach or missionary activities

dana taktis a discretionary source of government expenditure outside normal accountability and audit requirements (also known as non-budgetar)

Departemen Agama Ministry of Religious Affairs

xiv

desa rural village

Dharma Wisesa Hindu pamswakarsa in Lombok

dukun traditional healer

dusun hamlet

fatwa non-binding religious opinion of an Islamic scholar or organisation

Fiqh Islamic jurisprudence

Forum Kerukunan Umat Beragama (FKUB)

Forum to Maintain Inter-religious Harmony

Hadith the prophetic traditions

Haj pilgrimage by Muslims to Mecca

halus cultured or refined

haram forbidden according to Islam

Hezbullah the Lombok pamswakarsa controlled by NW Anjani

ibadah religious devotion

idul fitri celebration marking the end of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan

Institut Agama Islam Negeri Mataram (IAIN)

The State Islamic Institute Mataram

jilbab Islamic head scarf worn by women

joget traditional dance

jumatan Friday prayers

Kabupaten Regency

kampung urban village

kawin lari a form of spontaneous elopement

Kepala Camat head of kecamatan (sub-district)

Kepala Desa head of rural village

xv

Kepala Dusun head of hamlet

Kepala Lingkungan head of residential area

Kepala Polda (Kapolda) Police Chief, Provincial Police

Kepala RT / RW neighbourhood leaders

Kepolisian Republik Indonesia the national police

kerukunan social harmony

kekerasan violence, riots

Kesatuan Bangsa dan Perlindungan Masyarakat (Kesbanglinmas)

Office of National Unity and Community Protection. Essentially local intelligence

Ketua chair, chief of an organisation

khutbah sermon delivered during Friday prayers

kitab kuning literally ‘yellow books’ – religious texts used at Islamic schools containing commentaries on the Qur’an and Islamic law

Kiyai Islamic religious leader and teacher in Java. In Lombok, the word is also used to identify a village-level state-appointed religious official

komplek a housing development, typically inhabited by middle-class residents

Korps Brigade Mobil (Brimob) ‘Mobile Brigade’, national paramilitary police unit

kul-kul wooden drum which is struck to sound an alarm

Lang-Lang Jagad Titi Guna (Lang-Lang)

Mataram-based pamswakarsa

Lembaga Bantuan Hukum – Asosiasi Perempuan Indonesia Untuk Keadilan (LBH-Apik)

Legal Aid Foundation - Indonesian Women’s Association for Justice

Lembaga Dakwah The Muslim Outreach Institute (in Lombok)

Majelis Ulama The Ulama Association (in Lombok)

Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI)

Council of Indonesian Muslims – a quasi-state body that oversees religious matters and delivers

xvi

fatwa

masjid mosque – Muslim place of public worship

masyarakat society

muamalah social relationships

Muhammadiyah an Indonesian modernist mass Muslim religious movement

mushawara consultative community meeting

musholla small mosque, no Friday sermon is given at these places of prayer

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) a traditionalist mass Muslim religious movement

Nahdlatul Wathan (NW) a local traditionalist mass Muslim movement in Lombok (similar to Nahdlatul Ulama)

Negara Hukum law-based state

nyongkolan (S) traditional Sasak wedding parade

ojek motorcycle taxi driver

Orde Baru literally ‘New Order’, refers to the era when President Soeharto’s government administered Indonesia

pamswakarsa community-operated militia or security groups

Partai Bulan Bintang (PBB) Crescent Star Party

Partai Daulat Rakyat (PDR) People’s Sovereignty Party

Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan (PDI-P)

Indonesian Democracy Party of Struggle

Golkar literally ‘Functional Work Groups Party’

Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS)

Prosperous Justice Party

Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB)

National Awakening Party

Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (PPP)

United Development Party

Pastor Catholic Priest

xvii

pemuda youth

Penghulu a village-level state appointed religious official

Pendeta Reverend

Pengadilan Negeri Magistrates Court

Pengadilan Tinggi High Court

pengajian Qur’anic study group

Peraturan Daerah (PerDA) Regional Regulations

Perlindungan Masyarakat (Linmas)

unarmed police auxiliary

Polisi Daerah (Polda) Provincial Police

Polsek abbreviation for sectoral police – police operating at the sub-district level

pondok pesantren Islamic boarding school

pura Hindu temple

Qur’an the main religious text of the Islamic faith

Reformasi Reformation – the political reform process that brought democracy and decentralisation to Indonesia after the resignation of President Soeharto in 1998

ronda a traditional night watch, usually involving community members guarding their kampung

Rukun Tetangga (RT) a neighbourhood association that encompasses several streets

Rukun Warga (RW) a governmental unit that encompasses several RT

santri students of a pondok pesantren and religious followers of Tuan Guru

Sasak ethnic group indigenous to Lombok

Sasak Buda non-Muslim Sasak who adhere to animist and Buddhist beliefs

Satgas the Lombok pamswakarsa controlled by NW Pancor

xviii

satpam private security guards

suku literally ‘ethnic group’ or ‘tribe’

Sunnah behaviour of the Prophet Muhammad which acts as a guide for Muslims.

Syari’ah Islamic law

tabligh akbar mass religious meeting

Tentara Nasional Indonesia (TNI)

Indonesian National Army

tokoh adat adat (local customary rules) leader

tokoh agama religious leader

tokoh masyarakat community leader

Tuan Guru (TGH) a Sasak Islamic teacher and leader similar to Kiyai in Java

ulama Muslim religious leader

umat/ummah the Islamic community

Undang-undang statute produced by the national legislature (DPR)

Universitas Mataram (UNRAM)

The University of Mataram

upacara ceremony

ustadz (male)/ustadzah (female)

Muslim religious teacher

Waktu Lima refers to the orthodox Sasak Muslim majority in Lombok.

Walikota mayor

warga residents or citizens

warung food stall

Wetu Telu this is a syncretic Muslim group predominantly found in northern Lombok

zikir bersama group prayers

1

Chapter 1 Weak state, strong communities?

Research for this thesis commenced with a day of surfing the internet. I was searching

for stories of communal violence in Indonesia. What were the issues and where

should I undertake my research? I wanted to study the social instability and violence

that occurred in the wake of the fall of President Soeharto and his government in

1998. However, this topic was simply too large for a doctoral thesis and refinement

was necessary. So after several hours of trawling through dozens of articles covering

events as varied as the riots in Jakarta and ethnic conflict in Kalimantan, I stumbled

across a news report about five days of riots in Mataram and West Lombok that

occurred in January 2000. These events had seen Chinese and Christian Indonesian

residents flee the island for Bali or further afield, along with more than 4000 foreign

tourists. During these riots significant property damage and looting also occurred.

With this one news clipping my interest was piqued. This is where my research into

conflict management processes in Mataram and West Lombok began.

Flash forward just over one year later… and I am transfixed while seated in the small

office of Pastor Rosarius next to his church, Santa Maria Immaculate, in Mataram.

Causing this hypnotic effect were images of flames shooting across the computer

screen in front of me. These were images of Santa Maria Immaculate ablaze during

the January 2000 riots, when the church was razed by Muslim rioters.1 It was a potent

reminder of the continuing emotional effects of the riots. These five days saw an

anarchic and violent reality distant from the core teachings of Islam as understood by

many Muslim scholars in Lombok.2

There is, of course, significant support for the “peaceful and non-violent resolution of

conflicts” within Islamic teaching.3

1 Field notes, 11 October 2007. 2 Interview with TGH Ulul Azmi (Jerneng, West Lombok, 17 December 2007); Interview with TGH Mustiadi Abhar (Mataram, 23 July 2008); Interview with TGH Sofwan Hakim (Kediri, West Lombok, 13 August 2008); Interview with TGH Munajid Khalid (Gunung Sari, West Lombok, 24 August 2008). “TGH” means Tuan Guru Hajji. 3 Mohammed Abu-Nimer, ‘A Framework for Nonviolence and Peacebuilding in Islam’ (2000) 15 Journal of Law and Religion 217, 219. See also Karl-Wolfgang Troger, ‘Peace and Islam: In Theory and Practice’ (1990) 1 Islam and Christian – Muslim Relations 24; Mohammad Abu-Nimer, Nonviolence and Peacebuilding in Islam – Theory and Practice (2003).

2

… The meaning of the word Islam, which is too often

translated quickly by the mere idea of submission but… also

contains the twofold meaning of “peace” and “wholehearted

self-giving.4

Listening to Pastor Rosarius, however, it was hard to avoid the question of where

peace or the humility of submission to God was during the January 2000 riots? The

capacity of the symbols of Islam to be mobilised to support communal violence was

recognised by the local Islamic religious leaders, Tuan Guru.5 With their followers

(santri), many Tuan Guru sought to provide restitution to their Christian neighbours

in the period following the January 2000 riots for what had happened. Several Tuan

Guru also told me of their personal shame about these events. They said that the

rioters’ behaviour was against the teachings of Islam, which dictates to Muslims that

at the core of their religion’s belief is the imperative to strive to be ‘good’.6 This

involves seeking to understand people of different backgrounds and religious

perspectives.7

O humankind, God has created you from male and female and

made you into diverse nations and tribes so that you may

come to know each other…

Qur’an, 49:13.8

Perhaps naively, I had not realised the extent to which religion can be a force in social

issues, but over the past decade the mainstream media has often pointed to its

troubling connection with violence. The Qur’anic verse above highlights an important

religious injunction for Muslims – the requirement of respect for plural religious and

ethnic realities. One interpretation of the verse, common on Lombok, is that God has

4 Tariq Ramadan, The Messenger – the Meanings of the Life of Muhammad (2008) 1. 5 Tuan Guru and their role as socio-religious leaders will be considered in Chapter 3. 6 For an in-depth account of this theological issue, see Michael Cook, Commanding Right and Forbidding Wrong (2000). 7 Interview with TGH Sofwan Hakim (Kediri, West Lombok, 13 August 2008); Interview with TGH Muharror (Electronic Interview, 11 May 2009); . Interview with TGH Wawan Stiawan (Electronic Interview, 18 July 2009). 8 Abdullah Yusuf Ali (translator), The Holy Qur’an (2000).

3

created this diversity among people and that there is, therefore, an obligation to

engage with people from various faiths and different backgrounds. It highlights that

despite the extreme opinions and the violence sometimes perpetrated by some radical

religious groups, at the heart of most religions, including Islam, peaceful coexistence

is an important objective. This Qur’anic verse has a high level of salience in

Lombok’s largest city, Mataram, and the surrounding area of West Lombok, because

they have a Muslim-majority with large Christian and Hindu minoritycommunities.

The symbolism of religious affiliation and ritual can be reflected in communal

celebration as seen, for example, in the photograph below. It can also be utilised,

however, for the purpose of mobilising communal tensions.

Picture 1.1 An idul fitri parade (the Muslim celebration at the conclusion of the fasting month of

Ramadan) in Mataram

The reconciliation process between religious groups in Lombok has been protracted

since the January 2000 riots. For instance, Santa Maria Immaculate only reopened in

early 2008, after nearly eight years of restoration work. It is from these difficult and

emotional events that this thesis emerges. The research investigates state and non-

state actors and organisations in Lombok involved with avoiding or resolving

communal tensions and conflict.

4

Picture 1.2 Scaffolding outside the front of Santa Maria Immaculate during renovations in 2007

Picture 1.3 The altar of the church during renovations

Picture 1.4 Santa Maria Immaculate during renovations

5

In this thesis I seek to develop an understanding of conflict management processes

Mataram and West Lombok, a place that has experienced limited communal conflict

over the past decade. Much of the literature on Indonesian social tensions have,

understandably, explored the worst examples of tragic mob brutality and conflict, with

significant deaths and violence reported, for example in Jakarta, Ambon and Poso.9 In

these places, sharp communal and political violence occurred. By comparison,

Lombok’s January 2000 riots (which will be considered in Chapter 2) were limited to

only property damage rather than murders and sexual assaults. In essence, this was an

example of a society that, although affected by the broader political and economic

instability, did not descend into violence to the same extent as in other parts of

Indonesia around this time. I was interested to consider why this was so, given that

Lombok is one of Indonesia’s poorest provinces; poverty and economic disparities

have been widely recognised as important precursors to communal and political

violence across Indonesia.10

To add substance to my analysis of Lombok’s conflict management processes, two

case studies are used to investigate the management of communal and political

tensions and conflict in Lombok (see Chapter 5). The events documented in these case

studies occurred during 2008. They aim to provide tangible examples of conflict

avoidance and resolution in order to answer the key question of this thesis: what are

the legal and social mechanisms that have prevented communal violence in Mataram

and West Lombok?

9 See Freek Colombijn and Thomas Lindblad (eds), Roots of Violence in Indonesia: Contemporary Violence in Historical Perspective (2002); Jacques Bertrand, Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict in Indonesia (2004); Kasuma Snitwongse and W. Scott Thompson (ed), Ethnic Conflicts in Southeast Asia (2005); Jemma Purdey, Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia 1996-1999 (2006); Charles A. Coppel (ed), Violent Conflicts in Indonesia – Analysis, Representation, Resolution (2006); John Sidel, Riots, Pogroms, Jihad – Religious Violence in Indonesia (2007); Jamie S. Davidson, From Rebellion to Riots – Collective Violence on Indonesian Borneo (2008). 10 Patrick Barron, Kai Kaiser and Menno Pradhan, ‘Local Conflict in Indonesia – Measuring Incidence and Identifying Patterns’ (Presented at the 75 Years of Development Research Conference, Cornell University, 7-9 May 2004) 5; Luca Mancini, ‘Horizontal Inequality and Communal Violence: Evidence from Indonesian Districts’ (Working Paper No. 22, Centre for Research on Inequity, Human Security and Ethnicity, University of Oxford, 2005) 8; Rizal Sukma, ‘Ethnic Conflict in Indonesia: Causes and the Quest for Solution’ in Kusuma Snitwongse and W. Scott Thompson, Ethnic Conflicts in Southeast Asia (2005) 19-20; David Brown and Ian Wilson, ‘Ethnicized Violence in Indonesia: The Betawi Brotherhood Forum in Jakarta’ (Working Paper No. 145, Asia Research Institute, Murdoch University, 2007) 13.

6

The key findings of this research relate to the crucial role of religious leaders, Tuan

Guru, in conflict management processes in Lombok as social stabilisers and

mediators. Consequently, this thesis is the first comprehensive study of Tuan Guru

and their role in conflict management, although their high social status and socio-

political influence on Lombok affairs has certainly already been covered by a number

of scholars.11

The remainder of this chapter provides an outline of this thesis. The next section

considers some basic geographic, social and economic background. Following this, I

review weaknesses in state function and practice on the island. I then describe the

research methodologies and theoretical underpinnings of this thesis. The final section

of Chapter 1 then investigates social tensions and violence in Lombok, while

evaluating the mechanisms for conflict management and the economic and social

‘price’ (effect on the community) of violence over the past decade. The central

argument of this thesis will be examined in the following sections, namely that non-

state actors, particularly Tuan Guru, play a vital role in the maintenance of social

harmony in Lombok.

Situating this research

I conducted on over 15 months of field research in Mataram and West Lombok during

2007–2008. While in the field, I conducted over 75 in-depth interviews, undertook

detailed observational research and reviewed the archives of the Lombok Post over

key years of social conflict (1999-2000 and 2007-2008).

11 See, for instance, Judith L. Ecklund, Marriage, Seaworms, and Song: Ritualized Responses to Cultural Change in Sasak Life (PhD Thesis, Cornell University, 1977); Judith L. Ecklund, ‘Tradition or Non-tradition: Adat, Islam, and Local Control on Lombok’ in Gloria Davis (ed.), What is Modern Indonesian Culture? (1979); Sven Cederroth, The Spell of the Ancestors and the Power of Mekkah – A Sasak Community on Lombok (1981); Bartholomew Ryan, Alif Lam Mim – Reconciling Islam, Modernity, and Tradition in an Indonesian Kampung (PhD Thesis, Harvard University, 1999); Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak – Waktu Telu Versus Waktu Lima (2000); Leena Avonius, Reforming Wetu Telu: Islam, Adat, and the Promises of Regionalism in Post-New Order Lombok (2004); John MacDougall, Buddhist Buda or Buda Buddhists? Conversion, Religious Modernism and Conflict in the Minority Buda Sasak Communities of New Order and Post-Soeharto Lombok (PhD Thesis, Princeton University, 2005); Asnawi, Agama dan Paradigma Sosial Masyarakat (2006).

7

Mataram is the capital city of the province of Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB). Along

with the island of Sumbawa, Lombok makes up NTB. The island of Lombok is

located east of the Indonesian islands of Java and Bali. Mataram is a multi-ethnic and

multi-religious city,12 with a population of over 350,000.13

The majority of Mataram’s population identify as Sasak, the indigenous ethnic group,

who are predominantly Muslim. There are also substantial minorities of Christians

(10%) and Hindus (15 – 20%).14 In Lombok, sources of social tension include

economic disparities and historical animosities, but the era of democracy and

decentralisation have also seen the emergence of local political tensions that often

coalesce around ethnic and religious ‘fault lines’.15

Map 1.1 Indonesia, with Lombok circled

Map 1.2 Lombok, with Mataram and West Lombok circled

12 Fathurrahman Zakaria, Mozaik Budaya Orang Mataram (1998) 9-14; Mustain and Fawaizul Umam, Pluralisme Pendidikan Agama Hubungan Muslim-Hindu di Lombok (2005) 91-93. See also Badrul Munir, ‘NTB Dalam Mozaik Keindonesiaan’, Lombok Post (Mataram), 9 November 2007. 13 Badan Pusat Statistik NTB, Mataram Dalam Angka (2008) 83. 14 ‘Meredam Konflik, Menghidupkan Kasadaran Multikultur’, Religi (Mataram, Lombok), 16 April 2007. 15 Hendardi, ‘Republik Pluralis’, Kompas (Jakarta, Indonesia), 14 August 2007; Abdul Wahid, ‘NTB Plural Perlu Gerakan Harmoni’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 11 August 2008.

8

Mataram’s residents are heavily involved in religious rituals and organisations. This is

reflected in the local government’s slogan ‘Mataram – Progressive and Religious’

(‘Mataram – Maju dan Religius’).16 Religious places of worship are highly visible in

Mataram. According to the Indonesian Bureau of Statistics, there are over 1898 places

of Muslim worship in Mataram and West Lombok alone.17 Complementing this are 17

churches, 307 Hindu temples, 10 Buddhist temples and one place of Confuscian

worship.18 The vibrancy of this cultural diversity, and the colour that it brings to

Mataram, is seen with the Hindu religious festival, Hari Nyepi. The parade that forms

a major part of the Nyepi festivities on Lombok is seen in Picture 1.5 (below).

There are two reasons for emphasising Mataram and West Lombok. First, these are

the places where the riots of January 2000 took place. Second, these areas are more

religiously and ethnically diverse than other parts of Lombok. This leads potentially to

more points of communal tension and conflict. Additionally, limiting my research to

Mataram and West Lombok ensured a more focused and manageable sphere of

research.

Picture 1.5 Hindus celebrate, Hari Nyepi, in early 2007

16 This government slogan is discussed in Lalu Agus Fathurrahman, Menuju Masa Depan Peradaban – Refleksi Budaya Etnik di NTB (2007) 23-33. The devout nature of Mataram, and Lombok more broadly, has been discussed in Bartholomew Ryan, Alif Lam Mim – Reconciling Islam, Modernity, and Tradition in an Indonesian Kampung (PhD Thesis, Harvard University, 1999); Asnawi, Agama dan Paradigma Sosial Masyarakat (2006). 17 Badan Pusat Statistik NTB, Lombok Barat Dalam Angka (2007) 133; Badan Pusat Statistik NTB, Mataram Dalam Angka (2008) 145. 18 Ibid.

9

To research the whole of Lombok is difficult because of significant political, cultural

and religious diversity.19 Adat practices, for instance, vary among the Sasak across the

island, in fact, “Sasak adat varies in each village”.20 An example of this is the

traditional Sasak dance party, known as a joget. These events are usually held in local

communities to celebrate upcoming weddings or other festive occasions. This cultural

practice comes from Bali – it is, in fact, part of the Balinese colonial legacy in

Lombok, discussed further below.21 This celebration involves two or three female

dancers performing a traditional dance with male members and guests of the

community, accompanied by a traditional Sasak orchestra. The beautifully dressed

woman dances seductively with male members of the community as seen in Picture

1.6 (below). This tradition is often referred to as seksi dansing (sexy dancing) because

of its provocative nature, although, no touching is allowed. At the end of each song

the women dancer is paid by the man who has had the privilege of dancing with a

beautiful woman. This is a broadly acceptable social activity in West Lombok,22

however, in East Lombok, which has been less influenced by Balinese practices,

many Tuan Guru actively discourage this practice.23

19 There has been recent scholarship on Lombok that considers the way that the local political elite has sought to create a politicised single cultural identity for the Sasak, but I feel that this overlooks the island’s cultural diversity. The following are articles detailing the politicised use of adat, see Leena Avonius, ‘Reforming Adat: Indonesian Indigenous People in the era of Reformasi’ (2003) 4 The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 123; Kendra Clegg, Ethnic Stereotyping by Local Politicians in Lombok Fails to Please All (2004) Inside Indonesia <http://www.insideindonesia.org> at 19 January 2010. 20 Ruth Krulfeld, ‘Fatalism in Indonesia: Comparison of Socio-Religious Types on Lombok’ (1966) 39 Anthropological Quarterly 180, 181. 21 The complex engagement between Balinese and Sasak cultural practices is discussed in David Harnish, ‘Isn’t This Nice? It’s Just Like Being in Bali: Constructing Balinese Music Culture in Lombok’ (2005) 14 Ethnomusicology Forum 3. 22 This emphasis upon Mataram and West Lombok means that Sasak minority groups, such as the Sasak Buda and Wetu Telu, will not be considered in great depth. These groups are predominantly found in northern Lombok outside the area covered in this field research. For greater discussion of these groups, see Sven Cederroth, The Spell of the Ancestors and the Power of Mekkah – A Sasak Community on Lombok (1981); Erni Budiwanti, Islam Sasak – Waktu Telu Versus Waktu Lima (2000); Leena Avonius, Reforming Wetu Telu: Islam, Adat, and the Promises of Regionalism in Post-New Order Lombok (2004); John MacDougall, Buddhist Buda or Buda Buddhists? Conversion, Religious Modernism and Conflict in the Minority Buda Sasak Communities of New Order and Post-Soeharto Lombok (PhD Thesis, Princeton University, 2005). 23 Field notes, 9 January 2008.

10

Picture 1.6 A joget held in Mataram

Another example of this cultural and religious diversity can be seen with wedding

parades (nyongkolan). Nyongkolan are a popular adat ceremony in Mataram and West

Lombok, but in East Lombok they face prohibition, or are at least frowned upon. TGH

Humaidi Zaen, a Tuan Guru Lokal24 from Memben, East Lombok, told me that he had

advised his community not to undertake nyongkolan, because these ceremonies were

unnecessarily expensive and disruptive to road users as they can cause traffic jams.25

There are many other differences, within Lombok itself, including linguistic diversity

– the Sasak language, for example, has at least five dialects.26

These differences among the Sasak can be linked to many factors, and include the

island’s geography and long period of colonial occupation. It has also been suggested

that this cultural, linguistic and religious particularity dates back to the period even

before Balinese imperialism, when Lombok was “divided into numerous minor

kingdoms”.27 The Balinese controlled Lombok from around 1677, and by 1740, they

24 Tuan Guru can be divided into Tuan Guru Lokal (local Tuan Guru) and Tuan Guru Besar (important Tuan Guru). These categories reflect their spheres of influence and will be discussed in Chapter 3. Put simply, Tuan Guru Besar are important religious leaders with influence across the island, while Tuan Guru Lokal are less significant religious leaders, whose influence tends to be restricted to their own, local communities. 25 Interview with TGH Humaidi Zaen (Memben, East Lombok, 9 August 2008). 26 Mahyuni, Speech Styles and Cultural Consciousness in Sasak Community (2006) 44. 27 Albert Leemann, Internal and External Factors of Socio-Cultural and Socio-Economic Dynamics in Lombok (Nusa Tenggara Barat) (1989) 23.

11

had taken over the whole island.28 There was, however, continual resistance in eastern

Lombok and a major revolt by the Sasak from there in 1891-94, supported by the

Dutch. This rebellion ushered in a Dutch phase of colonial rule.29 Balinese

colonialism of over 200 years had a cultual impact on the island. It was felt more

potently in west and northern Lombok, where Balinese control was most entrenched.

This led to importation of their cultural practices into these areas to an extent much

greater than in other parts of Lombok.

Additionally, Lombok’s eclectic nature extends to the influence of religious

organisations. Muhammad Dimiati, a young religious leader from Mataram, told me

something that I had heard several times, namely that different mass Islamic

movements are dominant in different parts of Lombok. For instance Nahdlatul Ulama

(NU) is stronger in West Lombok, while Nahdlatul Wathan (NW), currently split into

two rival factions NW Pancor and NW Anjani, are the foremost religious

organisations in East Lombok. However, all these groups conduct activities across the

island.30 Despite highlighting the socio-cultural differences, there is fluidity in

groupings and affiliations across the island. For instance, in the village I have called

‘Lom’ 31 in Mataram32 many of the religiously-active members of the community are

affiliated to NW Pancor in East Lombok, and they go there almost every week for

Friday prayers rather than attending major mosques nearby.33 Therefore, my choice of

Mataram and West Lombok had a substantive rationale – the cultural and political

diversity on the island. However, it was also necessary to limit the geographic

boundaries of the research, which provided a more manageable area for fieldwork.34

28 W. Cool, The Dutch in the East – An Outline of the Military Operations in Lombock [Lombok], 1894 (1897); Alfons van der Kraan, Lombok: Conquest, Colonization and Underdevelopment, 1870-1940 (1980) 16-58. 29 Robert Cribb, Historical Dictionary of Indonesia (1992) 269. 30 Field notes, 9 August 2008. 31 ‘Lom’ is a pseudonym used to protect the anonymity of one of the areas where I undertook research within. This is in compliance with the University of Melbourne Ethics Committee approval for this project. 32 This community is focused upon in Chapter 4. 33 Interview with Mukhsin (Mataram, 14 July 2008). 34 The effect of diversity across Lombok on research findings has been noted in Bianca J. Smith, ‘Stealing Women, Stealing Men: Co-creating Cultures of Polygamy in a Pesantren in Eastern Indonesia’ (2009) 11 Journal of International Women’s Studies 189, 192.

12

Weak state, strong communities?

My analysis of Lombok involves reflection upon the strengths and weaknesses of

national institutions, such as the police and courts. Local affairs are directly affected

by the national context. Since declaring independence in 1945, Indonesia has

undergone several periods of social and political instability. This includes the

transition from the first to second Indonesian President in 1965-67. This event saw

hundreds of thousands of Communists (and alleged Communists) murdered in a semi-

sanctioned outbreak of political violence.35 Another period of instability followed the

Asian economic crisis of 1997 and the subsequent collapse of the Soeharto

Government in 1998. It led to outbreaks of violence across the Indonesian

archipelago.36

Economic and political turmoil during 1997-99 led to serious instability in Lombok.

The island confronted a ‘crime wave’ involving high rates of theft, anti-Chinese riots,

often out-of-control private militia and community security groups (pamswakarsa),

and sporadic periods of politically-motivated conflict between ethnic groups.

Underpinning this social instability was a weakening of state institutions. When state

institutions failed to function adequately due to the collapse of the Soeharto

government, local non-state authority figures and community groups sought to fill the

‘law and order’ void, specifically in relation to the provision of law enforcement

activities. There were many visible examples of this, such as the emergence of large

pamswakarsa, including Amphibi and Bujak.37 The weakness of the Indonesian state

and its ineffectiveness in Lombok is dealt within Chapter 2.

One of the practical problems caused by state weakness is that, rightly or wrongly,

government officials are held in low regard by many people in Lombok.38 If conflict

35 See Robert Cribb, The Indonesian Killings of 1965-1966: Studies from Java and Bali (1990); Fathurrahman Zakaria, Geger – Gerakan 30 September 1965 Rakyat NTB Melawan Bahaya Merah (2nd Edition, 2001). 36 For an in-depth exploration of various geographical outbreaks of violence and topics related to this period, see Charles A. Coppel (ed), Violent Conflicts in Indonesia – Analysis, Representation, Resolution (2006). 37 John M. MacDougall, Self-reliant Militias (2003) Inside Indonesia <http://insideindonesia.org> at 8 December 2009. 38 This was a common point made to me by informants when discussing perceptions of government officials. For instance, Interview with Herawati (Mataram, 7 October 2007); Interview with Imam (Mataram, 20 October 2007).

13

avoidance and dispute resolution partnerships discussed throughout this thesis are to

be strong and durable, then it is important that all parties, both state and non-state, are

respected and effective. The significant and valued role of non-state leaders will be

discussed in Chapters 3 – 5. One of the reasons for the importance of non-state actors

has been the relative ineffectiveness of state actors. There has, for example, been

widespread public criticism of government officials in Mataram (see Chapter 2). They

are seen as being akin to thieves, with people openly suggesting that many public

servants perceive themselves as being above the law.39 Local politicians have been

vocal for many years about the necessity for the provincial bureaucracy to be

‘slimmed’ down. They feel it to be ‘fat’ or bloated (gemuk). Public servants, it has

been suggested, need to change their attitude and no longer consider themselves to be

kings (raja) sitting above the community.40 During the worst periods of the political

transition to democratic governance, and the consequent ‘crime wave’ in Lombok,

people did not go to the police for assistance, but rather to pamswakarsa and non-state

leaders, particularly Tuan Guru.41 The police were not considered to be effective. In

fact, in many cases, people perceived that seeking their help would make the situation

worse.42

While I was in the field during 2007–2008, there were no significant reforms to the

performance of government departments and law enforcement agencies in Lombok,

although TGH Bajang made reforming the provincial public service a priority of his

incoming provincial administration.43 Dahlan Bandu, a senior provincial public

servant, felt that the NTB public service was slowly changing, but that the process

must be seen “as a marathon, rather than a sprint”.44

39 ‘Kinerja Aparat Hukum Patut Dikritik – Soge: Banyak Putusan di PN yang Selalu Dicurigai’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 27 December 1999; ‘Reformasi Birokrasi Menjadi Kunci Perubahan’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 3 November 2007. 40 ‘Reformasi, Baru Pada Tatanan Kepala dan Kaki – Taqiuddin: Belum Ada Wacana Demokrasi di Birokrasi’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 17 June 2000; ‘Birokrasi Yang Rigit, Ancam Iklim Democrasi’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 29 June 2000. Similar sentiments are also discussed by Denny Indrayana who considers the ‘feudal’ nature of the implementation of law and behaviour of the Indonesian judiciary which he felt fosters corrupt activities, see ‘Denny: Karakter Hukum Nasional Masih Feodal’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 3 June 2007. 41 ‘Perdamaian Disepakati, Lombok Selatan Aman Kembali’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 9 December 1999. 42 ‘Mengapa Kasus Pidana Tidak Dilaporkan ke Polisi?’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 27 December 1999. 43 TGH Bajang, ‘Pre-Inauguration Comments’ (Speech Delivered at Hotel Bukit Senggigi, 2 August 2008). 44 Interview with Dahlan Bandu (Mataram, 13 November 2007).

14

This thesis often emphasises non-state actors. However, when reflecting upon

governance reform, it is necessary not to lose sight of the day-to-day realities and

problems caused by poor management of government services. For instance, the

power grid is unreliable in Lombok. During the wet season power outages are a daily

occurrence – varying in duration from some minutes to several hours. Various reasons

are given for these problems, including the poor maintenance of the power

stations/electrical cabling or diversion of electricity to the hotels in Senggigi (a beach

resort town close to Mataram), which take too much power from the grid.45 Whatever

the true cause, it is seen locally as a continuing example, among many others, of the

state’s poor functioning in Lombok.

Today the Indonesian state remains weak. Arguably it is strengthening, but, even if so,

improvement is inconsistent and varies across the archipelago.46 In Lombok, there is

still a heavy reliance on non-state and local community organisations to fill gaps in

government activities, such as health, education and welfare services. This involves a

number of community organisations run by Tuan Guru and other community leaders.

The state in many ways does not play a significant role within people’s lives, or at

least not as significant a role as do Tuan Guru,47 whose socio-religious status and

function is discussed in greater depth in Chapter 3. This thesis, therefore, considers

how non-state players can augment state action and reinforce the Indonesian legal

concept of being a law-based state (Negara Hukum)48 by supporting state institutions

in conflict management.

As mentioned, these issues of conflict management are investigated through in-depth

analysis of local communities and two case studies. In all of these, partnerships

between state and non-state actors and institutions are emphasised. Chapter 4

considers the way that local leadership and community relationships operate,

particularly focusing on the area of Lom, Mataram, during and subsequent to the

January 2000 riots. The two case studies are presented in Chapter 5. The first case

study explores how the provincial government prepared for NTB gubernatorial 45 Field notes, 20 December 2007. 46 Christian von Luebke, ‘The Political Economy of Local Governance: Findings from an Indonesian Field Study’ (2009) 45 Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 201, 225. 47 Inflasi Tuan Guru (1976) Tempo < http://www.tempointeraktif.com/> at 18 May 2009; Muhammad Noor, Visi kebangsaan TGH Zainudin Abdul Madjid (2004). 48 This legal concept will be considered in greater detail in Chapter 2.

15

elections in July 2008. These preparations aimed to avoid religious, ethnic or political

conflict in the lead up to, and following, the elections. The second of these case

studies investigates events in the village of ‘Bok’ ,49 West Lombok, particularly

focusing on how state officials and communal leaders managed to defuse an outbreak

of social and political turmoil during July 2008. These chapters show how conflict

avoidance and dispute resolution mechanisms actually function ‘on the ground’.

Throughout this thesis the terms ‘state’ and ‘non-state’ leadership, actors and

organisations are used. When discussing state actors and institutions I refer to three

elements. The first are state institutions. These include government departments,

police and courts. The second element includes political leaders and public servants.

The final element covers legal instruments, such as legislation.50 When referring to

non-state actors and institutions I mean, first, social structures, rules and customary

practices or adat (predominantly Sasak adat).51 The second aspect of the non-state

category is leadership – communal (tokoh masyarakat) and religious leadership (tokoh

agama).52 This categorisation into state and non-state has become blurred in recent

years, as Tuan Guru have become actively involved in provincial and local politics.

For instance, TGH Bajang is now the NTB provincial governor, which makes him a

state actor, yet he is also a religious leader and head of the non-state religious mass

movement, Nahdlatul Wathan Pancor. I have found that this dichtomy of state and

non-state remains a useful typology for understanding socio-political affairs in

Lombok, even if the elements within them are often blurred and sometimes overlap at

their edges.

49 ‘Bok’ is a pseudonyms used to protect the anonymity of one of the areas where I undertook research within. This is in compliance with the University of Melbourne Ethics Committee approval for this project. 50 For a comprehensive explanation of Indonesia’s national legal structures, see Tim Lindsey and Mas Achmad Santosa, ‘The Trajectory of Law Reform in Indonesia: A Short Overview of Legal Systems and Change in Indonesia’ in Tim Lindsey (ed), Indonesia Law and Society (2008) 2-22. 51 In relation to the definition of adat, as a social process and form of local practices and rules, see M.B. Hooker, Adat Law in Modern Indonesia (1978) 50-51; Leena Avonius, ‘Reforming Adat – Indonesian Indigenous People in the Era of Reformasi’ (2003) 4 The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 123, 123; Greg Fealy and Virginia Hooker (eds), Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia – A Contemporary Sourcebook (2006) xxxiii; Craig Thorburn, ‘Adat, Conflict and Reconciliation: The Kei Islands, Southeast Maluku’ in Tim Lindsey (ed), Indonesia Law and Society (2008) 116. 52 Adat leaders (tokoh adat) are not included in this leadership category because people in Lom and Bok saw these roles as being fulfilled by community and religious leaders. They do not form a discrete category of leadership in these communities. This was confirmed in several interviews: Interview with Mukhsin (Mataram, 14 July 2008); Interview with Zaini (Bok, West Lombok, 16 July 2008). This was also the situation in other parts of Mataram, see Interview with Djalaluddin Arzaki (Mataram, 27 July 2008); Interview with Lalu Nurtaat (Mataram, 16 August 2008).

16

On the surface, conflict management in Lombok seems to ‘just happen’. However,

after closer scrutiny I realised that Lombok’s ‘chaotic harmony’53 is actually based on

a complex series of local relationships, leadership structures and social norms,

examples of which are highlighted in the following chapters. These strategies are not

perfect or neat ‘one-size-fits-all’ arrangements, but, rather, complex partnerships

based on networks and relationships between neighbours, religious leaders,

community figures and state actors. These partnerships are useful in two situations:

the first are ad hoc solutions to particular conflicts or potential problems. The second

involve ongoing conflict avoidance and dispute resolution processes.

Community relationships and the role of local non-state leaders, both of which

underpin the findings of this thesis, are explored in Chapter 4. An important aspect of

the local security mechanisms emerges not from a group or government agency, but

rather residents from different ethnic and religious groups protecting each other in

times of communal tension and violence. These social relationships are characterised

by regular communication and reliance on one and another. This role of community

relationships has been described to me by many informants as an important element of

Sasak adat.54 There are examples of communities in Mataram where relationships

were pivotal during difficult times – for instance, Kampung Sukaraja Barat in

Ampenan. This village is made up of Arab, Chinese and Sasak residents, who worked

together during the January 2000 riots to ensure each others’ protection. The local

press reported that community leaders from this kampung cooperated to ensure the

security and safe evacuation of those under threat.55

What will be seen time and again in the case studies is cooperation between state,

community and religious leaders to avoid or resolve disputes. How does this occur? A

community leader from East Lombok, Faharudin Hamdi, explained to me how, in

53 I use this notion of ‘chaotic harmony’ to identify the fluid and flexible nature of the maintenance of social harmony in Lombok, which operates in what sometimes seems to be chaotic environment. 54 The importance of communal relationships was discussed by many of the informants. They came from various social and class positions, as well as both community and religious leaders. See Interview with Sahnan (Mataram, 15 October 2007); Interview with Pendeta Hasanema (Mataram, 12 December 2007); Interview with Djalaluddin Arzaki (Mataram, 27 July 2008); Interview with TGH Munajid Khalid (Gunung Sari, West Lombok, 24 August 2008). 55 ‘Sukaraja Barat, Miniatur Kerukunan Antar Etnis’, Lombok Post (Mataram, Lombok), 27 January 2000.

17

general terms, these leaders coordinate their efforts. He said that religious leaders,

particularly Tuan Guru, lay the groundwork for conflict resolution through their

actions. This is achieved by Tuan Guru visiting protagonists and tailoring their

teaching and sermons to facilitate an atmosphere that would create calm amongst the

protagonists. State and non-state community leaders then undertake the practical

activity of negotiating a resolution of the dispute. They often do this through a

community meeting (mushawara).56 An example of this process and the use of a

mushawara is considered in Chapter 5.

Conflict avoidance and resolution frameworks are a complex amalgam of activities,

communal relationships and leadership. Included in these responses is the use of ritual

to bring different ethnic and religious groups together. These activities can be used as

a “medium for celebrating unity and ties between groups”.57 An example of this is the

annual Lombok festival of Perang Topat (war of the rice cakes), which is held in

fields just outside Mataram. Youths from Lombok’s Sasak and Hindu communities

engage in a mock battle against each other. Their ‘weapons’ are rice cakes, which

they throw at each other. This has the affect of turning the sometimes tense

relationships between these two groups into a festive ‘game’. At the end of the ‘war’,

the two communities, led by their respective spiritual leaders, hold separate religious

ceremonies side-by-side.58 This reinforces a distinct, but respectful, communal

arrangement. Groups celebrating joint activities together have also been considered an

important element for maintaining social harmony elsewhere in Indonesia, for

example in Manado, North Sulawesi, where events such as “wedding feasts or funeral

ceremonies” based on “community and family linkages” help create relationships that

are later used to manage social tension and resolve disputes.59 The application of joint

activities and festivities cannot be underestimated (examples of this are discussed in

Chapter 4). People both working and having fun together often has a powerful

unifying effect in Lombok.

56 Field notes, 10 August 2008. The importance of these community meetings in Lombok within conflict management and local decision-making was also discussed by Mohammad Koesnoe, Musjawarah Een Wijze van Volksbesluitvorming Adatrecht (1969) 22. 57 Leena Avonius, Reforming Wetu Telu: Islam, Adat, and the Promises of Regionalism in Post-New Order Lombok (2004) 27. 58 Mustain and Fawaizul Umam, Pluralisme Pendidikan Agama Hubungan Muslim-Hindu di Lombok (2005) 209-265. 59 Karen P. Kray, Operasi Lilin dan Ketupat: Conflict Prevention in North Sulawesi, Indonesia (MA Thesis, Ohio University, 2006) 7.

18

Despite believing that Lombok has, for the most part, been successful in maintaining

communal harmony, I do not suggest that it is free of problems. As noted, riots

occurred in January 2000 (as is described in Chapter 2). Fights can also arise over the

smallest things, for instance, disputes between youth on the basketball court can

become inflamed and lead to larger disputes.60 In Lombok, communal norms

precipitate an almost automatic sense of social solidarity. In these conditions, when

conflict emerges, villagers often move without question to defend other members of

their community, regardless of whether they have acted appropriately or were in fact

fully or partially at fault.61

Interpreting Lombok society and legal structures – A view from outside

Central to this thesis is an investigation of how to maintain social stability or resolve

conflict at a time or in a place where the ‘state’ is weakened, dysfunctional or simply

not functioning. From a legal perspective this is difficult, because ‘law’ and legal

responses to issues normally assume state action. It is expected that a ‘problem’ will

be managed by legal instruments, such as legislation, which authorise the police or

courts to act. But what happens if these instruments and institutions are non-existent,

irrelevant or greatly weakened by changing local conditions?

Due to the weakened state structure in Lombok, my research is at an intersection

between the disciplines of law and political science. Essentially, I sought answers that

extend beyond ‘traditional’ legal responses to social tensions and communal conflict.

Further to this, interdisciplinary research methods became imperative, because of the

need to give depth to Lombok’s complex social, political and legal context.

60 Interview with Achand (Mataram, 6 August 2008). 61 Institut Agama Islam Negeri (IAIN) Mediation Center, Social Conflicts in Lombok 1998-2006 (2007).

19

This thesis uses the concept of ‘legal culture’62 developed by Lawrence Friedman as

its theoretical cornerstone.63 This notion is best expressed by Friedman himself when

he wrote that “the legal culture… is a general expression for the way the legal system

fits into the culture of the general society”.64 When using this theoretical framework

‘law’ is considered to be courts and state institutions engaging, and being affected by,

society and cultural factors (and visa–versa). This allows for the study of ‘law’ not

just through the lens of formal written law (textual analysis), commonly known as

‘black-letter law’, but also considers the relationship between a society’s members

and its legal structures and rules, that is, contextual analysis.65 American legal

comparativist, John Merryman, considered that comparative legal studies, or the study

of foreign legal systems, needed to be cognisant of context: “legal systems have been

formed, and are sustained, by the action of historical events, social imperatives and

cultural forces… law is more than a body of rules”.66 Legal scholars undertaking

cross-cultural legal research, such as this, need to move beyond embedded

assumptions in order to gain an understanding of a ‘legal culture’ other than their

own.67

In Lombok, I heard frequently-repeated statements that local leaders, social norms and

community rules were more important than the state. For instance, the owner of small

local food stall (warung) close to my home told me that to resolve disputes in her

kampung (urban village) people went to communal or religious leaders rather than the

police or other state players or institutions.68 Implicit in the concept of legal culture is

the need to move beyond undertaking a legal analysis that only considers state-

62 The utility of legal culture came to my attention while undertaking research for my Masters thesis, see Jeremy Kingsley, Subverting the Global and Listening to the ‘Local’ – Reclaiming the Stories With(in) Comparative Legal Studies (LLM Thesis, Melbourne University, 2005). 63 See, for instance, Lawrence M. Friedman, ‘On Legal Development’ (1969) 24 Rutgers Law Review 11; Lawrence M. Friedman, ‘The Concept of Legal Culture: A Reply’ in David Nelken, Comparing Legal Cultures (1997). See also: David Nelken, ‘Disclosing/Invoking Legal Culture: An Introduction’ (1995) 4 Social & Legal Studies 435; Jothie Rajah, ‘Policing Religion: Discursive Excursions into Singapore’s Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act’ in Penelope Nicholson and Sarah Biddulph, Examining Practice, Interrogating Theory: Comparative Legal Studies in Asia (2008) 273. 64 Lawrence M. Friedman, ‘On Legal Development’ (1969) 24 Rutgers Law Review 11, 29. 65 Lawrence M. Friedman, ‘Legal Culture and Social Development’ in Lawrence M. Friedman and Stewart Macaulay, Law and the Behavioral Sciences (1969) 1004. 66 Pierre Legrand, ‘John Henry Merryman and Comparative Legal Studies: A Dialogue’ (1999) 47 American Journal of Comparative Law 3, 38. 67 Lawrence M. Friedman, ‘On Legal Development’ (1969) 24 Rutgers Law Review 11, 56-57. 68 Field notes, 19 June 2007.

20

sanctioned laws and institutions.69 It is essential to understand the intricate socio-

political realities within which legal systems operate and tailor the analysis

accordingly.70 Therefore, the non-state actors and organisations, as well as adat

practices, important in Lombok, should be incorporated into an analysis of the local

legal culture(s). These non-state institutions can, depending upon the circumstances,

be more potent and relevant than legislation and state institutions. This perspective

correlates with observations made by Clifford Geertz, when he researched Bali half a

century ago. He asserted that investigating non-state factors is essential in order to

comprehend how Indonesian societies function and regulate themselves.71 My

research findings endorse this perspective by investigating the role of both state and

non-state actors and institutions in conflict management processes.

An example of the complexity of Lombok’s legal cultures emerged in the Mataram

community of Lom.72 One of their leaders, Sahnan, told me that during the January

2000 riots several local residents from his urban village, Kampung Lom, had become

involved in the disturbances. The kampung leadership and a majority of its members

were unhappy with this. When the rioters returned from “misbehaving”, as Sahnan

described it, they were detained by community members.73 They were then taken to a

small empty building at the edge of the community and held until the police came to

collect them two or three days later. From there they were then taken to prison where

they stayed for a few months – until they had “cooled down”.74

No formal charges were ever laid against these rioters, nor did they ever appear before

a court. Justice was perceived to have been done by combining non-state (local justice

in the kampung) with state action (police intervention) to provide an outcome that was

supported by many, if not all, Kampung Lom residents.75 This highlights an overlap in

activity of state and non-state actors, while also showing a blurring of authority and

69 What is defined as ‘legal’ and ‘non-legal spheres’ is a troublesome, but important element of a legal culture, see Michael King, ‘Comparing Legal Cultures in the Quest for Law’s Identity’ in David Nelken, Comparing Legal Cultures (1997) 132-133. 70 Lawrence M. Friedman, The Legal System – A Social Science Perspective (1975) 193. 71 Clifford Geertz, ‘Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight’ (2005) 134 Daedalus 56, 58 [Reprinted from (1972) 100 Daedalus 1]. 72 Discussed in Chapter 4. 73 Interview with Sahnan (Mataram, 15 October 2007). 74 Ibid. 75 Ibid.

21

control. This example also identifies an inherent contradiction within the legal culture

of Lombok. The community and police cooperated to provide a ‘justice process’, but

to suggest it complied with formal legal processes or substantive Indonesian law

would be untenable.76

Roscoe Pound noted that law should not be considered ‘a stand-alone tool’, but as an

agent for achieving social control.77 In Lombok, social control emanates from both

state and non-state sources. This flexible use of ‘legal culture’ allows for an

exploration of the ‘baggage’ that exists underneath Lombok’s legal cultures.78 The

challenges and complexity of Lombok’s legal cultures require robust research

methods. But even before implementing these methodologies it is necessary to have