Translating Technology in Japan's Meiji Enlightenment, 1870–1879

Transcript of Translating Technology in Japan's Meiji Enlightenment, 1870–1879

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment,1870–1879

Ruselle Meade

Received: 27 October 2014 / Accepted: 2 March 2015

q Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan 2015

Abstract The enthusiasm for translation during the early Meiji period is well docu-

mented. However, beyond Fukuzawa Yukichi, the publishing sensation of the era,

little is known about those who translated works on technology or their motives for

doing so. During the 1870s, the heyday of Japan’s Meiji enlightenment, over fifty

works on technology were translated from Western languages. Although the govern-

ment often spearheaded this drive, many translators took advantage of inexpensive

printing technologies and an accessible book market to publish their own works on

Western technologies. This article examines who translated such works and their

motives for doing so. It sheds light on how translators exploited traditional means

of asserting their authority to ensure the spread of new, “modern” knowledge.

Keywords Meiji era�bunmei kaika�civilization and enlightenment�translation�technology�publishing

1 Introduction

Throughout the 1870s Japan’s nascent telegraph network began to take shape, criss-

crossing the country and linking major centers to hitherto remote provincial ones. For

the new Meiji government, the introduction of this system was a tangible sign of the

country’s development. However, the sudden appearance of these strange contrap-

tions in the countryside provoked alarm among villagers. Rumors that the blood of

virgins was being used to paint the telegraphic wires caused panic. Villagers rushed to

Acknowledgments An earlier draft of this article was presented at the “New Horizons in Modern Japan

History of Technology” workshop at the Needham Research Institute in May 2014. I thank the organizer,

AleksandraKobiljski, for her invitation. I am also grateful to Erich Pauer, Dagmar Schafer, TogoTsukahara,

Francesca Bray, and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

I would also like to acknowledge the continued support of TakehikoHashimoto, withwhom I have hadmany

productive discussions about Meiji industrial history.

R. Meade

School of Modern Languages, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AS, United Kingdom

e-mail: [email protected]

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal (2015) 9:253–274

DOI 10.1215/18752160-3120392

destroy this insidious “Christian magic,” and mobs uprooted telegraphic poles, threat-

ened workers, and even burned down telegraph stations (Teishinsho 1940: 93).1 This

greatly distressed one, Takase Shiro. “I hear that people are damaging telegraphic

lines. Why, oh why is such a thing happening” (Aa kore nan no tame zo ka na嗚呼之

レ何ノ為ゾ哉), he lamented (Takase 1873). Deciding that this behavior was the

result of “a most pitiful ignorance” (sono fugaku momai jitsu ni awaremu beshi 其

不学蒙昧実ニ憐ム可), he took it upon himself to enlighten those in rural areas by

translating a book on telegraphy that explained, in an accessible and patient style, how the

telegraphworked and the benefits its presencemight bring. After personally arranging for

his manuscript to be printed, he distributed copies of his book to village heads in the hope

that they would explain its contents to their villagers to placate them (Takase 1873).

Little is known of Takase Shiro. He produced no other works, and his only other

foray into publishing appears to be as a scribe of lectures on criminal law. We also

know little of others like him who translated technical books. When it comes to

translators of the West during the Meiji period, discussion is usually dominated by

the towering figure of Fukuzawa Yukichi. It was Fukuzawa who explained new tech-

nologies, such as the telegraph, to the public for the first time. His translations and

otherwritingswere best sellers; by his estimationGakumon no Susume学問のすゝめ(AnEncouragement of Learning) sold over two hundred thousand copies andwas used

as a textbook in the nascent nationwide school network. He was so successful that his

works and those of his associates came to comprise its own genre, called Fukuzawa

books (Watanabe 2012: 393). However, his considerable achievements should not

blind us to the other figures involved in translating works on Western technologies

during this period. Over fifty books on various new technologies were translated into

Japanese during the heyday of the 1870sMeiji enlightenment. The government-driven

nature of much of the industrial development during this period meant that most of

thesewere translated under the aegis of governmentministries and departments, which

often had their ownprinting facilities. But nearly half of theseworkswere published by

the commercial sector, often through small operations and sometimes by translators

themselves. Books produced by such publishers are significant because they targeted

audiences that the government-produced books were not intended to reach.

Although the government invested heavily in education, at both elementary and

tertiary technical levels, the beneficiaries were initially limited as the state still lacked

the means to reach beyond its own institutions. The constituencies served by the

government comprised those that studied at institutions, such as the Kaisei School

(later Tokyo University and then the Imperial University) or at the Kobu Daigakko

工部大学校 (Imperial College of Engineering). At both establishments, foreign

experts were brought in at considerable expense. There were also specialist insti-

tutions such as the Numazu Military Academy, and a few privately run schools

such as Fukuzawa’s Keio Academy and Mitsubishi’s Merchant Marine School. The

elite students also include the ryugakusei—those who were sent to study abroad,

usually to the Netherlands, Germany, France, United States, and Britain. Their com-

petence in foreign languages meant that they could access Western works in their

1 Telegraphs were also destroyed by anti-Meiji government forces during civil disturbances, and in some

cases vandalismwas linked to a general frustrationwith the government for its new impositions into people’s

daily lives (Wakai and Takahashi 1994: 88).

254 R. Meade

original languages and were often expected to do so. Any works in Japanese required

by this group would be produced by the government, and their circulation beyond the

institutions in which these elite were ensconced would have been limited.

This article examines commercially published translations, which tended to be used

outside of the elite, primarily in government-administered institutions to understand

whowas involved in shaping thewider Japanese public’s perception of the value of new

Western technologies during Japan’s early-Meiji enlightenment, theirmotives for doing

so, and the means by which they promoted the spread of new knowledge. It starts by

surveying the landscape of science and technology publishing in Japan during the 1870s

before addressing the role of translation in this enterprise. It then sheds light on the

practices of technical translators and examines their backgrounds and motives. It con-

cludes by considering the implied audiences of theseworks and how readersmight have

engaged with these texts. In doing so, it reveals that, despite the practical knowledge in

these works, translators’ efforts were generally undergirded by a desire to promote a

culture of science as befitted Japan’s aspirations to be a “modern” nation. It goes on to

show that, while many translators hoped to discard the past and usher in a new techno-

logical future, they remained reliant on traditional social structures in order to do so.

These works have so far been overlooked in the scholarship of Meiji technological

history because of their less specialist readerships. However, scholars examining

popularizations of science and technology in other new emerging nation-states have

underscored the tendency of such nonspecialist texts to embody a strong nation-

building agenda (Papanelopoulou, Nieto-Galan, and Perdriguero, 2009). In Italy,

another country seeking to forge a new unified national identity in the late nineteenth

century, efforts were made to acquaint the public with new developments in science,

which was seen as “the driving force behind progress, modernity and . . . the new

nation” (Govani 2009: 30). Thus, while these translations may not tell us a great

deal about the elite engineers most credited with Japan’s rapid industrialization in

the late nineteenth century, they can shed light on how other elites sought to shape the

Japanese public’s idea of the relationship between technical knowledge and Japan’s

hoped-for status as a “modern” nation.

Scholars have debated what exactly constitutes popularization, and there has been

considerable unease about the term itself (Secord 2004; Cooter and Pumfrey 1994).

Much of this criticism stems from the fact that the term popularization (or popular

science) suggests a top-down exercise wherein elites impart their professionally

acquired knowledge to an undifferentiated public through a process of simplification.

The aim here is not to add another challenge to this admittedly problematic positivist

diffusionmodel. Rather, this article accepts the contingency of the distinction between

the elite and the public and seeks instead to understand how translators—who, by

virtue of their competence in Western knowledge, were part of an elite (albeit a

nonscientific one)—sought to project their right to act as mediators, and how they

used their privileged position to do so.

2 Publishing Science and Technology during Japan’s Age of Enlightenment

It is not coincidental that the kyurinetsu 窮理熱 (science fever) of the early

Meiji period largely coincided with the bunmei kaika 文明開化 (civilization and

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 255

enlightenment) movement. Although bunmei kaika was sometimes associated with

superficial fads, such as eatingmeat and the appearance of newhairstyles andmodes of

dress, its core aims were ambitious. None was more so than its putative objective of

recasting civilization from its traditional definition of moral order to one grounded in

equality and scientific rationalism. The Meiroku Zasshi 明六雑誌 (1874–75), the

journal of the intellectual society Meirokusha, was the most emblematic represen-

tation of the enlightenment movement, and it was often a forum for those who argued

that modernization was inextricably linked to the development of scientific culture.

For example, in his “Methods for Advancing Enlightenment,” Meirokusha member

Tsuda Mamachi famously argued:

There are empty studies (kogaku) that are devoted to such lofty doctrines as

nonexistence and Nirvana [of Buddhism], the theory of the five elements [of

Sung Confucianism], intuitive knowledge and intuitive ability [of Yomeigaku].

And there are practical studies ( jitsugaku) that solely explain factual principles

through actual observation and verification, such as astronomy, physics, chem-

istry,medicine, political economy, and philosophy of themodernWest.Wemay

call a society truly civilized when the reason of each individual has been illu-

mined by the general circulation of practical studies through the land. (Quoted

in Braisted 1976: 38)

Members of the Meirokusha were themselves involved in promoting science and

technology. Fukuzawa Yukichi, whose 1868 work Kyuri zukai窮理図解 (Illustrated

Explanations of Scientific Principles) instigated this science fever, was a founding

member. Others members, such asMitsukuri Shuhei and Tsuda Sen, created their own

schools to promote practical learning, while Shimizu Usaburo opened his own book-

store to sell enlightenment works and was the author of a work introducing Western

chemistry to Japanese audiences (Braisted 1976: xxxiii). Some members, such as

Nishimura Shigeki and Mitsukuri Rinsho, were involved in the translation of some

of the technical works explored here.

Publishing has been called the “motor of the enlightenment movement” (Yayoshi

1993: 301). Evidence of this can be seen in the appearance of hundreds of publications

with bunmei or kaika in their titles, such as Bunmei kaikoku orai 文明開国往来

(Textbook on Civilization and Enlightenment) or Kaika kotohajime 開化事始 (The

Origins of Civilization). The use of such termswas not simply clevermarketing. These

works were often educational and covered practical fields as varied as tea farming,

forestry, bookkeeping, armament production, water management, and insurance.

Over five hundred such didactic works were produced during the 1870s (this figure

includes published magazines and reports) (Miyoshi 1992: 542). Among these were

works that sought to revive traditional techniques, such as silkworm cultivation and

architecture, while somewere publications of works that circulated only inmanuscript

form during the Edo period. Nevertheless, outside of agriculture and architecture,

attention was often directed toward the West. Many translators felt that Western

countries were powerful because they possessed advanced technologies. Therefore,

if Japan possessed these technologies, the thinking went, it too would be powerful.

Simple though this syllogismmay appear, it had considerable appeal, as can be seen in

the decision of many translators to shoehorn references to “the West” in the titles of

works even where there was no such reference in the original title.

256 R. Meade

The works considered here are those on technologies most associated with Japan’s

“modernization” (Table 1). Awide range of fields can lay claim to being technical. For

example, sericulture and farming still provided the bulk of the government’s revenues,

and translations were produced on these subjects. However, translation did not play as

significant a part in these fields, as they were not often deemed areas where Western

technology would be of much help. Furthermore, these fields were seen as the means

to, rather than the aim of, the modernity that Japan aimed to achieve. The focus on

works published outside of the government also excludes the considerable body of

translations produced by the Ministry of Education and the Naval Academy. Larger,

well-connected commercial publishing houses, such as Maruzen, were sometimes

commissioned by the Ministry of Education to publish textbooks and other pedagog-

ical works (Yayoshi 1993: 306). However, as these works were published under the

aegis of the government, they are not considered here alongside other commercially

published works. The works examined were selected on the basis of the National Diet

Library’s Catalogue of Books Published during the Meiji era (Kokuritsu Kokkai

Toshokan 1973: 473–553).

There is no specific date that can mark an end to the Meiji enlightenment. The

Meiroku Zasshi stopped publishing in 1875, the year after its launch, due to the intro-

duction of severe press laws. There was also a distinct conservative backlash from the

1880s, some of it coming from those who had initially championed Westernization.

From the standpoint of technical publishing, however, 1879 is an appropriate end. The

number of foreign government experts declined sharply in the 1880s as the govern-

ment started its indigenization drive whereby these expensive foreigners were

replaced with trained Japanese specialists. Consequently, the use of Western

languages for instruction in elite institutions was phased out, and increasing numbers

of Japanese specialists started writing and publishing books. Translations thus also

comprised a diminishing proportion of technical books. Unlike their early Meiji

counterparts, this new professional class of writers could point to their new, modern

engineering or science degrees as evidence of their authority. And, as the government

withdrew from publishing, the commercial sector increasingly took over the specialist

market of technical works for professionals.

3 Practices of Technical Translation

Translation ofWestern technical works in Japan long predates theMeiji period. Since

the late eighteenth century there had been concerted efforts to translate works on

Western military technology (Goodman 2000). The emphasis then was on acquiring

the know-how required to enforce the Tokugawa shogunate’s exclusion policy by

repelling Western ships attempting to enter Japanese waters. As the Dutch were the

only Europeans permitted to trade directly with Japan during much of the Edo period,

their language became the conduit for knowledge about the West, and in addition to

military works, books on anatomy, botany, and other fields of natural philosophy were

translated and studied by Rangakusha 蘭学者 (Dutch studies scholars) (Sugimoto

1995). The Chinese language was also a vector of knowledge of theWest. Because the

learned class was able to read Chinese, translations—first by the Jesuits and then, in

the nineteenth century, by Western protestant missionaries—were imported in sig-

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 257

Table 1 Self-published and commercially published translations of technical books in Japan from 1870

to 1879

Year TitleOriginal Title(Author), If Knowna Translator Publisher

1871 New Western Irrigation

Methods

西洋水利新設

Wakayama Gi’ichi

若山儀一

Wan’ya Kiei

椀屋喜平衛

1872 Manual for the Construction

of Western Dwellings

西洋家作ひながた

. . .Cottage Building . . .

(C. Bruce Allen)

Murata Fumio,

Yamada Koichiro

村田文夫・山田

貢一郎

Gyokusando

玉山堂

1873 The Story of the Telegraph

電信ばなし

Takase Shiro

高瀬四郎

Takase Shiro

高瀬四郎

1873 Textile Weaving Methods

織絎工術

Illustrated Instructions

for . . . the Bickford

Family Knitting Machine

(Dana Bickford)

Nishimura Shigeki

西村茂樹

Eikyusha

永久社

1873 A Summary of Western

Manufacturing Methods

西洋厚生一覧

Yokoyama

Shinsuke

横山深介

青藍舎

Seiransha

1873 New Land Surveying Methods

測地新法

A Manual of Land

Surveying

(W. M. Gillespie),

Military Surveying

(B. Jackson), Military

Surveying (G. H. Mendell)

Okamoto

Noribumi

岡本則録

Ryugido

龍曦堂

1873 Practical Geometry

幾何実用

Yamada Masakuni

山田昌邦

Seiransha

啓明堂

1874 NewMethods of Manufacturing

Glass

玻璃精造新法

Yokochi

Shunkichiro

横地儁吉郎

Yuhigakusha

有斐学社

1874 A Surveying Primer

測角便蒙

Asada Seiryu

浅田世良

Shokodo

尚古堂

1875 An Explanation of Machinery

器械撮説

Oshima Choshiro

大島長四郎

Ikkando

一貫堂

1875 Elementary Drafting

小学罫画法

Various (including

Hansell? and Bradley),

Naito Ruijiro

内藤類次郎

Naito Ruijiro

内藤類次郎

1876 Textbook of Drafting

訓蒙罫画法

Practical Plane Geometry

(John S. Rawle)

Oka Michisuke

岡道亮

Oka Michisuke

岡道亮

1876 A New Work on Dyeing

Experiments

染工新書化学実験

Miyazato

Masayasu

宮里正静

Ikkando

一貫堂

258 R. Meade

nificant quantity to Japan. These latter texts initially circulated in their Chinese

original form, but later annotations, variously called hyochu 標注, chukai 注解, or

goto 鼇頭, started to appear. Such annotations were Chinese texts to which reading

aids, called kunten 訓点, and short explanations were added to improve their com-

prehensibility to Japanese readers (Fig. 1). In the early 1870s when the Meiji govern-

ment instituted the new educational system, many schools carried out their own

Japanese translations of these Chinese texts (Meijimae Nihon Kagakushi Kankokai

1964: 226; Higuchi 2007: 423). Several versions of these translations, called wage和

解, remained in circulation even when newer translations from Western languages

(the preferred term in this case was yaku 譯) were being produced.2

1877 A New Work on Miscellaneous

Manufacturing Methods

百工製作新書

(Howell?) Miyazaki Ryujo

宮崎柳条

Bokuya Zenbei

牧野善兵衛

1877 A New Book on Surveying

測量新書

Elements of

Trigonometry . . . ?

(C. W. Hackley)

Arai Ikonosuke

荒井郁之助

Arai Ikonosuke

荒井郁之助

1878 A Complete Treatise on Dyeing

Experiments

染工全書化学実験

Miyazato

Masayasu

宮里正静

Yamanaka

Ichibei

山中市兵衛

1878 A Short Introduction to

Meteorological Instruments

風雨鍼用法略記

Nakai Kotaro

中井幸太郎

Yurinjuku

有隣塾

1878 A Handbook of Mineralogy

金石学必携

Manual of Mineralogy,

Systems of Mineralogy

(J. Dana),Manual of

Determinative

Geology (G. J. Brush),

and others

Sugimura Jiro

杉村次郎

Sugimura Jiro

杉村次郎

1878 Elementary Geometrical

Drawing Methods

小学幾何画法

Yamada Masakuni

山田昌邦

Yamada

Masakuni

山田昌邦

1879 Geometry for Drafting

画用幾何

Shizuma Mitsu

静間密

Sakata Yasujiro

阪田保次郎

1879 AHandbook on the Hydrometer

験液器用法箋

Nakai Kotaro

中井幸太郎

Nakai Kotaro

中井幸太郎

The original titles and names of authors are gleaned from such sources as frontispieces and prefaces. During

the early Meiji period, many publishers were simply booksellers rather than commissioners of works.

Furthermore, republished editions may have different publishers.a A question mark indicates an educated guess based on incomplete or unclear information.

2 Typicallywagewere identified as such by suffixing this term to the title of the book,whereas the term yaku

would be suffixed to the translator’s name.

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 259

Rangakusha were noted for their close adherence to source texts when translat-

ing (Fukuzawa 1897, cited in Itakura 1968: 68), but the need to appeal to the new

audiences engendered by the new bunmei kaika movement necessitated greater

flexibility, and this gave rise to a plethora of experimental approaches to translation.

This meant that although the West may have served as an aspirational model,

Japanese translators did not give much deference to its texts. They intervened

radically, shaping them in ways that often make it difficult to discern the sources

from which they drew. One way that translators across all genres often distanced

themselves from their sources was by neglecting to record bibliographic infor-

mation. Only rarely is the name of the author displayed on covers or frontispieces

of translations, and although prefaces do sometimes provide the name of the author,

these are often transliterated into kanji, making it difficult to reconstruct the original

author’s name. Even when sources are provided, they cannot necessarily be taken at

face value. To give one example, the Frenchman Adolphe Ganot, author of Traite

elementaire de physique experimentale et appliquee et de meterologie, which is

identified as one of the sources of A Short Introduction to Meteorological Instru-

ments, is mistakenly identified as an American seemingly because the English

translation of the French work was used as the source.

Tracing sources is further complicated by the fact that translations were sometimes

syntheses of various works. William M. Gillespie alone is cited as the original

Fig. 1 Two early Meiji-era approaches to translation. These are Japanese versions of the Chinese natural

philosophy book Bowu xinbian 博物新編 by Benjamin Hobson. Both translations were produced by the

same translator, Fukuda Takanori, in 1875 and 1876, respectively. In the 1875 version (left), reading

markers, which include verb inflections and indication the order in which the characters should be read

to conform to Japanese grammatical patterns, have been added. In the 1876 version (right) the original

Chinese text is provided with fewer reading markers. Each line of Chinese text is instead followed by

explication in Japanese. Courtesy of the National Diet Library, Tokyo

260 R. Meade

author on the frontispiece of New Land Surveying Methods. However, the translator,

Okamoto Noribumi, acknowledges in the preface that Gillespie’s manual was sup-

plemented with material from two identically titled but solely authored works called

Military Surveying by the British authors Jackson and Mendell, alongside other

unnamed works. When one compares Okamoto’s forty cho (equivalent to eighty

pages) of text to Gillespie’s five-hundred-page tome, it is immediately apparent that

few sections correspond to each other, and the debt to theMilitary Surveying texts is

less clear. Gillespie assumed that his readers had an awareness of the tools required for

surveying and thus focused on trigonometric calculations for surveyors. Okamoto, on

the other hand, sought to “reduce the complexity of vocabulary andmake it suitable for

a beginner” (yogaku ni ben narashimu o i to su幼学に便ならしむるを意とす) and

instead introduced each of the surveyor’s tools individually, providing an illustration

for each one and explaining their components in detail.

Bringing together sources—sometimes from disparate genres—into a single trans-

lation was common. For example, NewMethods of Manufacturing Glass was a trans-

lation of books by unnamed “Prussian” and “British” authors, and Short Introduction

to Meteorological Instruments cited as sources an 1864 work by a British author and a

book by two Americans (one of whom is the aforementioned Ganot, the second likely

his translator). Supplementary works were sometimes used to redress some perceived

inadequacy in the main source—Okamoto said that he had made changes to “rectify

deficiencies” (ketsu o oginai 欠を補い) in the source—but often these materials

provided translators with much needed guidance in deciphering the English original.

Sugimura Jiro, the Japanese translator of James Dana’s Manual of Mineralogy,

wrote of his indebtedness to a previous Chinese translation of the same work. Not

only would the translator’s likely previous education in reading the Chinese classics

make reading the Chinese text helpful in understanding the English text, but also the

translator could rely on neologisms coined in Chinese rather than having to reinvent

new terms. At least one case—ANewWork onMiscellaneousManufacturingMethods

by Miyazaki Ryujo—appears to be entirely based on a previous Chinese translation

rather than the English original.

Translators not only relied on other works to improve their texts but also drew on

their own experiential learning. In compiling A Complete Treatise on Dyeing Exper-

imentsMiyazato Masayasu claimed to have enhanced the original, which he does not

identify, by relying on knowledge acquired from “years of experience carrying out

experiments” (sekinen jikken suru tokoro 積年実験スル所) and through “acquiring

and closely observing several imported fabrics” (hakusai no kagamihin jusu rui o ete,

shitashiku kore o mokugekishi 舶載ノ鑒品十数種ヲ得テ、親シク之ヲ目撃シ).

Likewise, Sugimura Jiro, the translator of Dana’s Manual of Mineralogy, relied on

his knowledge of mineral deposits in Japan, which was likely gleaned in some part

from an already sizable body of literature on mining in Japanese. Additions were not

limited to text. Noribumi Okamoto (New Land Surveying Methods) added images,

such as the one shown in Figure 2, in an attempt to clarify how surveying tools were

actually used. This image does not merely convey information about surveying. It is

repletewith symbols designed to evoke “civilization,” such as stereotypicallyWestern

clothing (trousers, jackets, and hats), as well as ships. Brick buildings with spires were

also a common motif in bunmei kaika books as these were considered emblematic of

the West.

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 261

Omission, however, was themost common intervention. Translators sometimes cut

content as they aimed simply to provide a “foundation” (taihon 大本) or merely a

“summary” (taiyo大要) where they considered the field “too vast” (kokan tatan浩瀚

多端) (e.g., Elementary Drafting). Sometimes omissions were necessary to remove

any material that was potentially offensive or was likely to be misconstrued, as in the

case of the Japanese translation of Rudimentary Treatise on Cottage Building, or,

Hints for Improving the Dwellings of the Labouring Classes (1854) by C. Bruce Allen.

The original British publication was part of a Christian drive to raise the morals of

the poor by providing them with inexpensive yet sound housing; Allen noted in his

introduction:

The condition of the poor is, without doubt, unfriendly to mental culture and

progress. . . . A family crowded into a single and narrow apartment, which is at

once living-room, kitchen, bedroom, nursery, and often hospital, must, without

great firmness and self-respect, be wanting of neatness, order, and comfort. The

want of an orderly and comfortable home is among the chief evils of the poor.

(Allen 1854: 2)

Allen’s explanation of the Christian basis for his building methods runs to twenty

pages. It is the introductory chapter and thus frames the work as part of a morally

driven mission. However, the 1872 Japanese translation was published at a time when

Christianity had only just been legalized in Japan and proselytismwas still frowned on.

The translators therefore not only removed this material but also completely refash-

ioned the significance of the work by renaming it Manual for the Construction of

Fig. 2 An image added to New Land Surveying Methods, translated by Okamoto Noribumi. Images were

often presented in an imagined modern context and symbolic of “civilization,” such as brick buildings,

oceangoing vessels, and Western-style clothing, conspicuously displayed. Courtesy of the National Diet

Library, Tokyo

262 R. Meade

Western Dwellings (Seiyo kasaku hinagata 西洋家作ひながた), thereby presenting

the buildingmethods as being typical ofWestern houses. In the preface they argued the

superiority of the new building methods by reframing it to address a local preoccu-

pation, widespread destruction by fire, arguing that “Westerners do not prioritize

beauty when building houses, but protection against fire” (yojin no kashitsu o chikuzo

suru ya, moto yori birei o mune to suru ni arazu, moppara kasai no bogyo o shu to

suru 洋人ノ家室ヲ築造スルヤ、素ヨリ美麗ヲムネトスルニアラズ。専ラ火

災防禦ヲ主トスル).

The most obvious explanation for such interventions is the translator’s desire to

make their works more accessible to their new audiences. Indeed, translators often

cite the fact that a book was “easy to read and understand” (yomiyasuku kaiyasuki

no sho 易く解し易きの書) as a reason for translating it. However, another reason

was the translator’s time constraints. When he published the first volume of his

translation Practical Geometry, Yamada Masakuni told his readers there would be

seven further volumes, but it appears that he did not have the time to fulfill this

ambition. Likewise, Wakayama Gi’ichi said that his translation of New Western

Irrigation Methods had to be done in a “rush” (soso 怱々) because his substantive

employment as a government bureaucrat left him little time to translate the work. It

is probable, too, that many Japanese translators found the Anglo-American style of

writing tedious. The typical nineteenth-century British technical manual was for

many authors a forum to demonstrate their expansive knowledge and rhetorical

flair. Books in excess of five hundred pages filled with seemingly superfluous

minutiae were the norm, and authors could easily get carried away if not reined

in by a strict publisher. Another factor is that the practice of intoning the text,

which was common to early Meiji readers, considerably slowed the pace at which

books could be consumed (Maeda 2004: 260).

These are all important considerations, but in other contexts the expectation of

fidelity to the original trumps all other concerns. The fact that early Meiji translators

felt no such duty to the original is revelatory of their privileged social and legal status.

Social status is discussed in the next section, but a note now about the translator’s legal

position: translators’ activities and their ownership of their work were protected by

law. The Publication Statute of 1869 provided protections for translations to “[pro-

mote] the importation of western knowledge” (Ganea 2005: 501). Furthermore, the

Japanese PublishingAct of 1875 enshrined the rights of translators as identical to those

of authors (albeit placing them in a more subordinate position vis-a-vis publishers),

giving them both exclusive rights to publish and sell their works for thirty years

(Nunokawa 1971: 371). The translator’s position as a powerful mediator acting

under his own agenda was also reflected in the materiality of the translations, particu-

larly through the visibility accorded to the translator (and frequent invisibility of

original authors) on covers and frontispieces, and sometimes even in prefaces.

This diverges markedly from contemporary practices, where translators’ relative

“invisibility” is attributed to their self-identification as a servant of the author (Venuti

2008 [1995]). Far from identifying with the author, most early Meiji translators

completely usurp the original author’s position as the economic and intellectual

proprietor of the publication.

The ownership granted by the publication statues referred to the right of translators

to retain ownership of the woodblocks used to print the texts. Woodblock printing was

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 263

the predominantmode of book production in the earlyMeiji period before it eventually

succumbed to the rise of typesetting in the mid-1880s (Kornicki 2001). Typesetting

had been reintroduced to Japan in the 1850s, but its expense put it well beyond the

means of most publishers. Not only did typesetting require the casting of thousands of

type to accommodate the use of Chinese characters, but such works had to be printed

on machine-manufactured rag-based paper, which was not produced in sufficient

quantities in Japan to sustain commercial publishing until the mid-1870s. This

meant that typeset works were overwhelming produced by the government or those

having close associations with it.

Woodblock printing was entirely free of mechanization and therefore labor inten-

sive. But it was also a “rather cheap and quick method” (Forrer 1985: 26) that pre-

sentedmuch lower barriers to participation in publishing. The translator could produce

a manuscript, purchase their own blocks, find a carver to transfer the manuscript onto

these blocks, and then employ a printer to prepare the books. The blocks would remain

the property of the translators, thereby granting them copyright, while the books could

be entrusted to prominent booksellers for sale (Kornicki 2001). This economic own-

ership gave translators considerable clout, as no further books could be produced

without their consent. (However, the practice of pirating books by creating newwood-

blocks was common.) The rise of typesetting in the 1880s completely upset this model

and had the effect of excluding self-publishers and small commercial enterprises,

which did not have the resources to invest in the expensive equipment required.

The book historian Adrian Johns (1998: 33) has pointed out that modern author-

ship, as defined under copyright law, is both “economic” and “epistemic.” It is econ-

omic in that authors typically own the work in the same sense as they would a physical

object and gain financially from its sale. It is also epistemic in that whatever is

inscribed on the page is considered the intellectual property of the author. The author

must be consulted and attributed if any portion of the work is used. In the case of

translations, the author retains ownership. However, early Meiji translators usurped

the author’s position in both economic and epistemic senses. The original text was

merely a basis—sometimes only a form of inspiration—for their project. It was the

translator who decided how the material would be presented and gained financially

from its sale. Rather than being a servant of the author, translators placed the original

text and author in a subordinate position.

4 Translators and Their Motives

Explaining why he had written Elementary Drafting, Naito Ruijiro recounted a con-

versation with an education official, Higaki Naosuke, during a visit back to his home-

town on the island of Shikoku. The provincial educator remarked that although

geometry was on the new school curriculum, there was a need for books as few people

had expertise on the subject. He then said to Naito, “I heard that you have studied

engineering in Europe, so why don’t you translate a book?” (katsute oshu ni asobi,

kogaku ni juji seri to, yoroshiku sara ni keiga no hon o yakushi嘗テ欧州ニ遊ヒ工学

ニ従事セリト宜ク幸ニ罫画ノ書ヲ訳シ). Naito thus compiled a book using the lec-

ture notes he takenwhile a student atKing’sCollege London, supplemented, it appears,

with material from textbooks used during his course. The field was too vast to write a

264 R. Meade

comprehensive volume, he explained, so thisworkwasmerely an outline for beginners.

He promised that a further volume for advanced learnerswould be forthcoming, but this

later work does not seem to havematerialized. This anecdote illustrates the background

of translators, aswell as theirmotives. It shows thatwhile translators of technicalworks

would not have been blind to the potential financial benefits of the publishing activities,

such rewards were very much a secondary concern, and translations were typically

done as a part-time pursuit alongside substantive employment.

Often this employmentwas as a civil servant, and even sometimes as a translator for

theMeiji government. Nishimura Shigeki (1828–1902), translator of TextileWeaving

Methods, was head of the Ministry of Education’s editorial office, where he translated

works on the history and practice of education, such as L. P. Brockett’s History and

Progress of Education, for use in teacher training schools (Ueda et al. 2001). Like

other translators, such as Wakayama Gi’ichi and Arai Ikonosuke, he had previously

cultivated a considerable reputation as a Rangakusha, having studied under the emi-

nent scholar Testuka Rituzo. The manuscript of his Dutch-Japanese dictionary Jisho

Genko字書原稿, which is now housed at the National Diet Library in Tokyo, demon-

strates his accomplishments in Dutch studies. He was also an associate of Mori Ari-

nori, who was ambassador to the United States and who invited him to join the

Meirokusha group of Meiji intellectuals (Usui et al. 2001: 791). He was thus firmly

connected to the leadership of the Meiji government. Wakayama Gi’ichi, for his part,

was an apprentice of another famed Rangakusha, the physician Ogata Koan, and his

closeness to the scholar manifested by his adoption of the professional name Ogata

Gi’ichi (1170). Arai Ikonosuke received his training from the Dutch-administered

naval academy in Nagasaki before being made a commander in the navy (35).

It is also clear fromNaito’s recollection that he was considered ideal because of his

experience studying in England. Murata Fumio, cotranslator of Manual for the Con-

struction of Western Dwellings, and another former apprentice of Ogata Koan, is

another example of a translator who studied abroad. Murata had studied mathematics,

surveying, and geography in London and Aberdeen (Niwa 1999: 339). As has been

pointed out, those such as Naito and Murata, who had the enviable experience of

studying in Europe or North America, were propelled to the top of the technical

hierarchy on their return (Tsunekawa 2005). When he came back to Japan, Murata

worked as both a teacher and surveyor for the Ministry of Public Works (Niwa 1999:

340). BothMurata andNaito thus apparently combined their writingwith their work as

engineers (in Murata’s case he eventually gave this up to go into publishing full time).

Why did these individuals, who circulated in rarefied circles, go beyond the call of

duty and translate works in their free time? The high official positions of these trans-

lators meant that, in some cases, they were involved in crafting government policy. It

is therefore not surprising that they would have been highly invested in ensuring that

these policies were successful. It is also telling that while Nishimura’s translations in

his capacity as a government translator were primarily theoretical works on education,

his privately translated works were in such practical fields as textile spinning and

household finance. Working privately meant that translators could respond to what

they considered the nation’s immediate needs and produce works of benefit to those

not served by the government’s publication activities. It therefore granted them free-

dom to explore new topics and fresh approaches to translation. Translations produced

by the Ministry of Education tended to meticulously cite their sources, and translators

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 265

rendered mostly full and faithful translations (Naganuma 2012), whereas the trans-

lations they produced outside of this environment weremuchmore fluid. For example,

Nishimura completely refashioned Dana Bickford’s Illustrated Instructions for Set-

ting Up and Running the Bickford Family Knitting Machine (1871) in translating it.

Bickford intended that his machine be used as a domestic appliance to “enable the

weary housewife to have a few hours of rest and recreation, as well as the matrons of

young ladies of leisure and fashion to have a never failing foundation of pleasure as

well as solid enjoyment” (v). Nishimura, however, had the freedom to transform the

work into a manual for those with entrepreneurial intentions.

Naito’s reminiscence also makes clear that the new school and curriculum stimu-

lated some of this translation activity. The Ministry of Education invested heavily in

translation, but, as his recollections indicate, the demand for pedagogical material

outstripped the ministry’s ability to supply it. Until the introduction of the elementary

school curriculum in 1881, textbooks were not strictly prescribed by the Ministry of

Education. Some authors wrote didactic works in the hope that their books would be

adopted as textbooks for primary schools and thereby provide them with a lucrative

source of income (Miyoshi 1992: 633). Meanwhile, some teachers felt they had no

choice but to redress the lack of suitable books by producing their own translations.

Indeed, most translations on geometry were for use in schools. For example, Oka

Michisuke, translator of John S. Rawle’s Practical Plane Geometry, was a teacher of

mathematics in Ryukoku, while Yamada Masakuni, formerly a teacher of mathemat-

ics at the Numazu Military Academy (Higuchi 2007: 556), decided to translate

Elementary Geometrical Drawing Methods as he had “yet to find a good book that

provides adequately detailed coverage of this subject” (imada kono gaku o shosetsu

suru zensho aru o mizu未だ此学を詳説するの善書あるを見ず) for those studying

at an elementary level. Similarly,Geometry for Draftingwas translated by the teacher

Shizuma Mitsu to fit the mathematics curriculum for elementary schools in Sakai

province. Yokochi Shunkichiro, the translator of New Methods of Manufacturing

Glass, was also a teacher. He had set up a division in his school, he explained,

where students gained new knowledge from the West by orally reciting the Japanese

translations of foreign works. He downplayed his translation abilities but said that he

had no choice but try his hand at it: “if I leave this for another month, it is another

month the children are not helped” (hitotsuki kore o ta ni yuzureba, hitotsuki yodo no

tasuke sukunashi 一月之ヲ他ニ譲レバ一月幼童ノ助ケ少シ).

Other textbooks targeted the commercial sector. Sugimura Jiro explained that A

Handbook ofMineralogy had been written in response to a request to “translate a book

onmining as it is urgently needed by those working in the industry” (kogyo ni juji suru

mono no tame ni kin’yo no kozansho o yakushutsu坑業ニ従事スルモノ丶為ニ緊要

ノ鉱山書ヲ訳出). The appeal had come from Godai Tomoatsu, a prominent entre-

preneur who had established the Koseikan, a business for developing mines through-

out the country. His motives for soliciting the translation were thus linked to his

business interests. Godai was aware of the need in the private sector for books to

introduce new knowledge. After establishing another operation, the Choyokan—this

time to benefit from the restrictions on the import of indigo—he authored Seisei

Aizomegyo Suchi 精製藍染業須知 (On Producing Indigo Dyes) for that industry.

This was the same industry Miyazato Masayasu aimed to reach with his translation, A

Complete Treatise on Dyeing Experiments, which he claimed presented “a wealth of

266 R. Meade

information that will be beneficial engaged in the business of manufacturing dyes”

(zosen o gyo to suru mono oini eki suru tokoro ari造染ヲ業トスル者大ニ益スル所

アリ). Godai and Miyazato had previously been associates. Fifteen years before the

Meiji Restoration, Godai was sent to Britain by his domain, Satsuma, for study. On his

return he established Japan’s first Western-style spinning plant, where Miyazato was

put in charge (Hasegawa 2006). They were therefore both pioneers in integrating

Western techniques into traditional Japanese productionmethods. Like the other trans-

lators discussed above, theywere of the elite, but theywere not part of the government,

demonstrating that there was some diversity even within this narrow demographic.

Expertise in foreign languages was a highly regarded skill, but was not pursued for

its own sake. New yogakko 洋学校, or “schools of Western studies,” appeared with

great frequency from the late 1850s once Japan had signed treaties with the major

Western powers. Mere competence in languages was not the aim of these schools.

Rather, language was seen as a means of acquiring expertise that was trapped behind a

language barrier. It is therefore not surprising that those with such coveted skills were

able to attain (or, in most cases, maintain) a life of economic stability as government

officials or entrepreneurs. But this does not mean that all translators hailed from a

privileged section of society. Furthermore, they did not all translate in a paternalistic

attempt to enlighten “ignorant” villagers, educate school children, or train industrial

workers. For some, translation was less about creating a translated product and more a

means of close personal engagement with books. Both A Short Introduction to Mete-

orological Instruments and A Handbook on the Hydrometer were a by-product of

Nakai Kotaro’s research wherein he “consulted various works by Western experts”

(taisei shotaika no chosho泰西諸大家の著書) on how tomake and use these respect-

ive instruments. The books, he explained, were published as they “might be of use to

someone who wants such an instrument” (aru hito kono ki o seikyu shite yamazu或人

此器ヲ請求シテ已マス). Like Nakai, Miyazaki Ryujo was an autodidact. However,

his knowledge ofWestern techniques seems to have comemostly from Chinese trans-

lations ofWestern works. He was a keen reader who consulted and translated books as

part of his research into manufacturing and out of a “love of in depth study of the

natural laws” ( fukaku kakubutsu no gaku o konomi 深く格物の学を好み). An arti-

san, he claims to have spent all of his free time reading everything from flora and fauna

to machines and maps. When he needed clarification he would ask a teacher friend or

seek out conversations with Westerners. Eventually he published the outcome of his

research because, he noted, “if [readers] applied themselves more than [Westerners],

perhaps it will be of some help in promoting development” (i yori ken ni ireba kaichi

no tame ni shoho arankaya 夷ヨリ険ニ入レバ開地ノ為ニ小補アラン歟).

Much of what we know about translators and their motives comes from what

they reveal about themselves in the prefaces to their works. As these are a site

where translators aim to craft their persona and to convince readers of the special

import of their works, the information cannot be accepted uncritically. Yet, it is this

suasive function that makes these prefaces so valuable. They reveal translators’

desire to let readers know that the knowledge they were presenting was new and of

value to the development of the nation. They also sought to underscore their

familiarity with the material. They projected themselves not as mere linguistic

conduits but as experts who had a direct experience of using and engaging with

the knowledge they were conveying.

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 267

5 Implied Readers

The well-rehearsed methodological challenges of investigating reading practices

(Chartier 1994)3 are compounded in the case of these earlyMeiji technical translations

by the unavailability of publisher records. Asmany of theseworkswere self-published

by translators or published by small commercial enterprises that went defunct with the

upheaval of Japan’s publishing industry in the 1880s, we lack information on the

number of copies sold and their distribution. Insight into readers must thus be gleaned

from how translators and publishers addressed their readers through paratexts such as

the frontispieces, colophons, and prefaces, as well as through the register and the

content of the text itself. What this tells us, then, is not so much about the actual

readership as about implied readers (Booth 1961).

There is, too, some anecdotal material about reading in the early Meiji period that

can shed some light on how books were acquired by readers. One such account comes

from the anarchist thinker Ishikawa Sanshiro (1876–1956), who recalled that his

father had to travel from Saitama to Tokyo to buy a copy of Fukuzawa Yukichi’s

Gakumon no Susume (Maeda 2004: 224). Others fromoutside Tokyo speak of the need

to borrow other such best-selling books from friends or to use the postal service to have

them sent from the capital. The colophons of technical translations, which typically

list where the books are sold, reveal the book market to be predominantly Tokyo-

centric. And althoughmost technical books were relatively affordable, ranging from a

mere four sen in the case of A Handbook on the Hydrometer to fifty-five sen for

Elementary Drafting, they were not necessarily easily obtainable.4 Moreover, even

the more comprehensive bookseller catalogues, which were a key means of advertis-

ing books, include only a few technical works. Both the Osaka and Tokyo versions of

the List of Books Published since the Boshin War (Matsuda 1874; Ota 1874) include

only Practical Geometry and The Story of the Telegraph (at twenty and ten sen,

respectively), and only a few other technical works can be found in smaller catalogues.

If even the most popular works were so difficult to acquire in the provinces, and

technical works were not widely advertised, their circulation is likely to have been

highly limited.

Limited circulation does not, however, necessarily mean limited influence. Anoth-

er important means by which readers could learn of books was by recommendation,

and the paucity of extant hard copies of books suggests that they were often copied

rather than bought. Moreover, it would make little sense for more specialist works,

such as A Handbook of Mineralogy or New Western Irrigation Methods, to appear in

advertisements aimed at audiences looking for lighter fare. In addition, early Meiji

bookstores did not operate on an open shelf system whereby books could be freely

perused—books had to be fetched by an assistant depending on the needs of the

customer (Forrer 1985: 51). In such a situation, the buyer would direct inquiries to

3 Chartier (1994: 50) notes that investigating reading poses a particular challenge because it is “a practice

that rarely leaves traces, that is scattered in an infinity of singular acts, and that easily shakes off all

constraints.”4 It is possible that some technical translations were more expensive than this, but this is the highest price

verifiable from the colophons.

268 R. Meade

the master of the shop, and the reputation of the translator—or any other name associ-

ated with the work—could then be a strong selling point.

The involvement of supervisors illuminates one means by which translators and

publishers sought to attract readers and convince them of their authority to act as

mediators. The putative role of supervisors was proofreading works to ensure accu-

racy of translation and sophistication of prose. However, the prominence afforded to

their names on frontispieces and the bestowal of titles such as sensei betray their

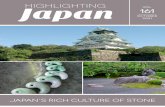

significance in marketing the books (Fig. 3). It is clear that publishers assumed that

readers would be aware of and be awed by supervisors’ considerable reputations.

Usually such supervisors had worked at the Bansho shirabesho 蕃書調所 (later

Fig. 3 The frontispiece to A Summary of Western Manufacturing Methods.

The name of the translator is preceded by that of the supervisor, Mitsukuri-

sensei. This likely refers toMitsukuri Rinsho箕作麟祥, a well-knownWest-

ern scholar and grandson of the family’s renowned Rangakusha patriarch,

Mitsukuri Genpo 箕作阮甫. Use of the name Mitsukuri alone suggests an

attempt to draw on the cachet of the entire family. Courtesy of the National

Diet Library, Tokyo

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 269

Yosho shirabesho 洋書調所), where the shogunate assembled leading scholars

to translate materials relating to the West, and they were often doyens of esteemed

Rangaku clans, such as the Mitsukuri 箕作 and Katsuragawa 桂川. Although

these were luminaries, their names would be immediately recognizable only to fellow

scholars, bureaucrats, and aspirational merchant-class readers. This was a relatively

restricted demographic, but relatively high literacy rates in 1870s Japan meant that it

was still large enough to be commercially attractive.

The lack of phonetic glossing ( furigana) alongside kanji in many of the works and

the use of the katakana-based style of writing provide further evidence that the books

were targeted mainly at a relatively well-educated audience. By the late Edo period,

most (but by no means all) samurai, who comprised only 5–6 percent of the popu-

lation, were highly literate, and literacy levels approached 40 percent in large urban

areas, such as Osaka and Edo (Tokyo) (Rubinger 2007). The use of a katakana-based

writing style, rather than themore “feminine” hiragana, also suggests that the material

was for men of learning. The relatively small size of this demographic, as well as their

elevated level of education, meant that translators were often writing for their students

and peers. The relatively equitable relationship between translators and their readers

can been sensed from translators’ dialogic overtures to their readers: translators had a

habit of professing themselves “ignorant and poorly informed” (sengaku kabun浅学

寡聞). Such humility was indeed a formulaic requirement of the translators’ intro-

ductory notes. Yet such assertions are often followed by an appeal to readers to report

corrections—an indication that their humility was not entirely contrived. There is

enough to suggest that they considered their readers as their coequals. Translators

were legally required to give their addresses in the colophons of works, so it was

certainly feasible for readers to bring errors to the attention of the translator. It is likely

that some readers of the translations by Sugimura and Miyazato, who worked in the

mining and textile industries, respectively, were fellow professionals with whom they

had direct contact. Some translations were republished in revised editions.Miyazato’s

1878 A Complete Treatise on Dyeing Experiments, for example, was a revised and

expanded edition that “addressed deficiencies and omissions in his previous work”

(zensho no ketsuro o oginai前書ノ缺漏ヲ補ヒ). Were any of these corrections from

readers? It is difficult to say with certainty, but the possibility cannot be discounted.

The peers atwhom translationswere targeted could also be fellow scholars from the

literate urban classes. Although a teacher, Yokochi Shunkichiro did not make any

concessions to those with lower levels of literacy. Not only was there no phonetic

glossing of kanji, but also the endorsements provided at the front of his book were

written bywell-known scholars in kanbun漢文. Prefaces in this highly Sinicized form

of Japanese, which would have been legible only to the very well educated, were

often found in technical manuals. There was a mania for “enlightenment” among the

kanbun literate, with many devouring any book on the West regardless of topic.

Evidence of such avaricious reading habits can be seen in the enthusiastic endorse-

ment by the high-ranking military bureaucrat, Toda Tadayuki, for New Methods of

Manufacturing Glass:

[The years since] the Restoration has seen the opening of an era of cultural

progress, and study of the West is flowering. Boys and girls, men and women,

everyone must now engage in [this] learning. There are now also people

270 R. Meade

who [can] translate western books and this is convenient for learning. From

information on government systems, to cultural customs to their curious

technologies and details of their daily life, translated works have through [the

Japanese] language or through pictures, provided clear information on countries

over the world. Now translated books of many kinds are appearing in great

numbers and are truly flourishing. . . . I depend on these translated books for

my knowledge of foreign countries, so when a new translated book appears I get

it and read it.5

Toda’s kanbun preface was preceded by another by Yanagimoto Naotaro. Yanagi-

moto was an accomplished scholar who had served as Prince Hirostune’s personal

assistant during his studies in the United States (Nihon Rekishi Gakkai 1981: 1026).

These were thus endorsements from the highest echelons. Kanbunwas used to under-

score this fact and to assert the scholarly pedigree of their writers. Notably, both

endorsements emphasized the book’s ability to promote cultural advancement rather

than any utility for industry. Similarly, although the content in Nakai Kotaro’sA Short

Introduction to Meteorological Instruments (Fig. 4) might have been useful for rural

farmers, the katakana-based writing style and the copious inclusion of calculations

using Arabic numerals suggest that the readers were men of learning (former samurai

and rich merchants), as well as their sons.

Nakai’s other translation, A Handbook on the Hydrometer, however, was likely

more successful in cultivating not simply cultural but also technological understand-

ing beyond such audiences. It is a much shorter work and provides less material.

However, it is written in hiragana-based style with phonetic glossing of kanji. More-

over, Arabic numerals are also always glossed with their Japanese equivalent in kanji.

The same writing style can be seen in other texts, such as New Land Surveying

Methods (Fig. 2), which the translator, Okamoto, explicitly directed at “beginners.”

Although aimed at less literate audiences, A Handbook on the Hydrometer provided

practical benefit. The hydrometer could be used to determine the strength and quality

of liquids such as alcohol and dyes, and although Okamoto’s work did not provide

insight into the finer details of trigonometry in New Land Surveying Methods that

would be essential for the surveyor, it provided clear explanations of the tools that

surveyors would use and how to use them.

Takase Shiro’s The Story of the Telegraph, which was introduced at the beginning

of this article, shows the diversity of readers and reading practices in earlyMeiji Japan.

This work is aimed at a rural population and is written in a simple style with illus-

trations and copious amounts of phonetic glossing. Although literacy was less wide-

spread in rural areas than in urban ones, each village would have a literate head. This

was a legacy of the shogunal system of governance, which necessitated that there be

one among the village to ensure that edicts and other correspondence from the

domain’s central administration could be passed on to each person in every village

around the country. As Takase’s account demonstrates, it was not only political cor-

respondence that was circulated in this way. Those seeking to propagate useful knowl-

edge about modern technologies could exploit this traditional information network.

5 This translation is based on rendering of the kanbun text intomodern Japanese provided byMiyoshi (1992:

182–83).

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 271

6 Conclusion

The enthusiasm for civilization and enlightenment during 1870s Japan saw a whole-

hearted desire among some elites to “discard the old ways.” Yet it was traditional

social and legal structures that enabled the propagation of knowledge about new

technologies. This can be seen not only in the case of Takase Shiro’s use of Edo period

information networks to have his books reach as many rural dwellers as possible but

also in the way that many translators sought to assert their legitimacy as mediators.

They gained authority from their role as Western scholars rather than from any pro-

fessional background as engineers—an identity that was still being formulated in early

Meiji Japan. They also drew on the cachet of those who were associated with Edo-

periodRangaku (Dutch studies) traditions. Similarly, although theWest was replacing

China as an aspirational model, endorsements were often written in kanbun to lend an

air of authority. The ability to write in elegant Chinese remained a means of dis-

tinguishing the learned, even if one was a specialist in Western studies. The existence

of woodblock printing and traditional book circulation networks, too, allowed many

self- and commercial publishers to participate in the book market.

Much of this was to change in the 1880s as barriers to entry into publishing became

more imposing as a result of the growing adoption of typesetting technology.

Increased reliance on this expensive printing method meant that many early Meiji

publishers, particularly small commercial houses and individual self-publishers, who

Fig. 4 A page from A Short Introduction to Meteorological Instruments. The katakana-based writing style

without phonetic glossing and calculations using unfamiliar Arabic numerals identify it as a work for

relatively well-educated men. Incidentally, the calculation contains an error likely introduced during the

engraving process: the final minus sign should in fact be a plus sign. Courtesy of the National Diet Library,

Tokyo

272 R. Meade

were ill-equipped to weather this technological shift, fell by the wayside. The gov-

ernment, having played an important role in the field in its nascent stage, began to take

a backseat as the private sector—now dominated by large publishing houses with

extensive bookselling networks—began to extend its influence over the technical

literary field. The backgrounds of those translating technical works also changed.

The first cohort of engineers graduated from the Kobu Daigakko in 1879. Many of

those who had been sent to study abroad in large numbers in the 1870s were also

returning at this time. These mediators had new means of asserting their legitimacy,

and they made frequent reference to their degrees and professional experience on the

frontispieces of works. This new demographic represented the new status quo that the

early Meiji era enlighteners sought to beckon. It was by bringing together the tra-

ditional and the modern—the familiar and the unfamiliar—that they were able to

accomplish their goal.

References

Allen, C. Bruce (1854).Rudimentary Treatise onCottage Building; or, Hints for Improving theDwellings of

the Labouring Classes. London: John Weale.

Bickford, Dana (1871). Illustrated Instructions for Setting Up and Running the Bickford Family Knitting

Machine. Hartford: Case, Lockwood, and Brainard.

Booth, Wayne C. (1961). The Rhetoric of Fiction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Braisted, William R. (1976). Meiroku Zasshi: Journal of the Japanese Enlightenment. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Chartier, Roger (1994). The Order of Books: Readers, Authors, and Libraries in Europe between the

Fourteenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cooter, Roger, and Stephen Pumfrey (1994). Separate Spheres and Public Places: Reflections on the History

of Science Popularization and Science in Popular Culture. History of Science 32: 237–67.

Forrer, Matthi (1985). Eirakuya Toshiro, Publisher at Nagoya: A Contribution to the History of Publishing

in Nineteenth Century Japan. Amsterdam: Gieben.

Fukuzawa Yukichi 福澤諭吉 (1897). Fukuzawa Zenshu Shogen 福澤全集緒言 (Preface to the Collected

Works of Fukuzawa). Tokyo: Jiji Shimpo.

Ganea, Peter (2005). Copyright Law. In History of Law in Japan since 1868, edited by Wilhelm Ro hl andHorst Hammitzsch, 500–522. Leiden: Brill.

Goodman, Grant (2000). Japan and the Dutch, 1600–1853. Richmond, UK: Curzon.

Govani, Paola (2009). The Historiography of Science Popularization. In Papanelopoulou, Nieto-Galan, and

Perdriguero, Popularizing Science and Technology, 21–42.

Hasegawa Masayasu 長谷川雅康 (2006). Kindai Nihon reimeiki ni okeru Satsuma-han Shuseikan jigyo

no shogijutsu to sono ichitsuke ni kansuru sogoteki kenkyu近代日本黎明期における薩摩藩集成館

事業の諸技術とその位置付けに関する総合的研究 (A Comprehensive Study of the Various Tech-

nologies and Their Role in the Operations of Satsuma Domain’s Shuseikan at the Dawn of Modern

Japan). Kagoshima: Kagoshima Daigaku (http://hdl.handle.net/10232/119).

Higuchi, Takehiko 樋口雄彦 (2007). Numazu heigakko no kenkyu 沼津兵学校の研究 (Studies on the

Numazu Military Academy). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Itakura, Kiyonobu板倉聖宣 (1968).Nihon rika kyoikushi日本理科教育史 (History of Science Education

in Japan). Tokyo: Daiichi Chihoki Shuppan.

Johns, Adrian (1998). The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Kokuritsu Kokkai Toshokan国立国会図書館, ed. (1973).Kokuritsu kokkai toshokan shozo: Meijiki kanko

tosho mokuroku dai san maki 国立国会図書館所蔵:明治期刊行図書目録 第 3 巻 (National Diet

Library Holdings: Catalog of Books Published during the Meiji Era, vol. 3). Tokyo: Kokuritsu Kokkai

Toshokan.

Kornicki, Peter F. (2001). The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth

Century. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Translating Technology in Japan’s Meiji Enlightenment 273

Maeda, Ai (2004). Text and the City: Essays on Japanese Modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Matsuda Masasuke松田正助, ed. (1874). Boshin irai shinkoku shomoku ichiran戊辰以来新刻書目一覧

(List of Books Published since the Boshin War). Osaka: Shishodo.

Meijimae Nihon Kagakushi Kankokai 明治前日本科学史刊行会 (1964). Meijimae Nihon butsuri

kagakushi 明治前日本物理化学史 (The History of Physics and Chemistry in Japan before Meiji).

Tokyo: Nihon Gakujutsu Shinkokai.

Miyoshi, Nobuhiro三好信浩 (1992).Kindai Nihon sangyo keimosho no kenykyu近代日本産業啓蒙書の研究 (A Study of Introductory Textbooks on Industry in Modern Japan). Tokyo: Kazama shobo.

Naganuma, Mikako 長沼美香子 (2012). Kaika keimoki no hon’yaku koi―Monbusho “Hyakka zensho” o

megutte 開化啓蒙期の翻訳行為―文部省『百科全書』をめぐって (Translating in the Early Meiji

Period: A Case of Chamber’s Information for the People). Honyaku kenkyu e no shotai翻訳研究への招待 7: 13–39.

Nihon Rekishi Gakkai 日本歴史学会 (1981).Meiji Ishin Jinmei Jiten明治維新人名辞典 (Dictionary of

Meiji Restoration Biography). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Niwa, Kazuhiko丹羽和彦 (1999). Murata Fumio to “Seiyo kasaku hinagata” ni tsuite村田文夫と『西洋

家作ひながた』について (A Study on FumioMurata andHisManual for the Construction ofWestern

Dwellings). InNihon kenchiku gakkai taikai gakujutsu koen kogaishu日本建築学会大会学術講演梗

概集, 339–40. Tokyo: Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai.

Nunokawa, Kakuzaemon 布川角左衛門, ed. (1971). Shuppan jiten 出版事典 (Dictionary of Publishing).

Tokyo: Shuppan Nyususha.

Ota, Kan’emon, ed. (1874).Boshin irai shinkoku shomoku binran戊辰以来新刻書目便覧 (Guide of Books

Published since the Boshin War). Tokyo: Baigando.

Papanelopoulou, Faidra, Agusti Nieto-Galan, and Enrique Perdriguero, eds. (2009). Popularizing Science

and Technology in the European Periphery, 1800–2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Rubinger, Richard (2007).Popular Literacy in EarlyModern Japan. Honolulu:University ofHawai’i Press.

Secord, James (2004). Knowledge in Transit. Isis 95, no. 4: 654–72.

Sugimoto, Tsutomu杉本つとむ (1995).Edo no hon’yakutachi江戸の翻訳家たち (Translators of the Edo

Period). Tokyo: Waseda Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Teishinsho遞信省, ed. (1940). Teishin jigyoshi逓信事業史 (History of Telecommunications Industries).

Tokyo: Teishin kyokai.

Tsunekawa, Seiji 恒川清爾 (2005). Meijiki Nihon no doboku jigyo o sasaeta gijutsusha shudan to sono

tokucho 明治期日本の土木事業を支えた技術者集団とその特徴 (Civil Engineers and Their

Characteristics in Meiji Japan: An Analysis of Their Educational and Social Background). Kagakushi

kenkyu 科学史研究 44: 177–90.

Ueda, Masaaki上田正昭, Nishizawa Jun’ichi西澤潤一, Hirayama Ikuo平山郁夫, and Miura Shumon三

浦朱門, eds. (2001). Nippon jinmei daijiten 日本人名大辞典 (Dictionary of Japanese Biography).

Tokyo: Kodansha.

Usui, Katsumi臼井勝美, Takamura Naosuke高村直助, Toriumi Yasushi鳥海靖, and Yui Masaomi由井

正臣, eds. (2001). Nippon kingendai jinmei jiten 日本近現代人名辞典 (Dictionary of Modern and

Contemporary Japanese Biography). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Venuti, Lawrence (2008 [1995]). The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London: Routle-

dge.

Wakai, Noboru 若井登, and Yuzo Takahashi 高橋雄造 (1994). Terekomu no yoake: Reimeiki no honbo

denki tsushinshiてれこむノ夜明ケ:黎明期の本邦電気通信史 (The Dawn of Telecommunications:

A History of the Birth of Japanese Telecommunications). Tokyo: Denshin Tsushin Shinkokai.

Watanabe, Hiroshi (2012). A History of Japanese Political Thought, 1600–1901. Translated by David

Noble. Tokyo: International House of Japan.

Yayoshi, Mitsunaga 弥吉光長 (1993). Bakumatsu Meiji shuppan shiryo 幕末明治出版史料 (Primary

Sources on Bakumatsu and Meiji Publishing). Tokyo: Yumani shobo.

RuselleMeade is Lecturer in Japanese Studies at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the circulation

of scientific and technical knowledge, particularly through translation and popularization, in modern Japan.

She is currently working on a monograph that explores how popular representations of technology have

helped shaped notions of Japanese identity from theMeiji period onward. This article was completed during

a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Tokyo.

274 R. Meade