Okinawa's Experience of Becoming Japanese in the Meiji and ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Okinawa's Experience of Becoming Japanese in the Meiji and ...

The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Volume 18 | Issue 20 | Number 7 | Article ID 5498 | Oct 15, 2020

1

Between a Forgotten Colony and an Abandoned Prefecture:Okinawa’s Experience of Becoming Japanese in the Meiji andTaishō Eras

Stanisław Meyer

Abstract:

Japan’s attitude towards Okinawa during theMeiji and Taishō periods defied concretedefinition. Although nominally a prefecture,Okinawa retained a semi-colonial status for twodecades after its annexation in 1879. Despitethe fact that Okinawan people acceptedJapanese rule with little resistance, whichultimately turned into active support for theassimilation policy, Japanese policy makersnever lost their distrust of Okinawan people.Similarly, Japanese society did not fullyembrace them, perceiving them as backwardand inferior, and even questioning theirJ a p a n e s e - n e s s . T h e e x p e r i e n c e o fdiscrimination strengthened the Okinawanpeople’s motivation to fight for recognition astrue Japanese citizens. Local intellectuals, suchas historian Iha Fuyū, embarked on a missionto prove that Okinawa was and always hadbeen Japanese.

From a certain perspective, Okinawan modernhistory falls into the paradigm of colonizationor integration under the Japanese nation-state.The crucial clue to understanding Okinawa’scase lies in the fact that it was a poor country,with little natural resources to offer. UnlikeHokkaido, there was no mass migration frommainland Japan to Okinawa. Unlike Taiwan andKorea, Okinawa did not attract skillful andambitious administrators. Accordingly,Okinawa was turned neither into a modelcolony, nor a modern prefecture, but remained

a forgotten and abandoned region.

Keywords: Japan, Okinawa, history, Meijiperiod, colonialism, modernization, nation-state, nationalism, identity

In 1888, Prince Paul John Sapieha (1860–1934),a member of a respected, Polish noble family,embarked on a journey to East Asia. Thejourney brought him to Japan, making him oneof the first Polish people to set foot on Japanesesoil. Sapieha kept a journal on his travels,which he published eleven years later underthe title Podróż na wschód Azyi (A Journey toEast Asia).1 In Tokyo, he met an Austrianpainter, Francis Neydhart (1860–1940), andtogether they made a short trip to Okinawa atthe end of March 1889.

Sapieha spent less than a week in Okinawa andhe described his impressions of the island inonly a few pages. Yet this short accountpresents valuable testimony about Okinawa inthe late nineteenth century. He rememberedthis journey with great nostalgia, in particularthe treatment he received from the governor,who assigned personal guards, interpreters, acarriage and a rickshaw to his entourage.“They must mistake me for some Austrianpr ince o f the b lood ,” he wrote wi thamusement. 2

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

2

The Okinawan people captured his heart. Hewas enchanted by the local culture, especiallyby the dances and music, which he found moreappealing and interesting than those of Japan.He depicted the local people in exceptionallywarm words that sharply contrasted with whathe wrote about the Japanese administrators ofthe island:

Yesterday, in the evening, the governor ofthis country – or better to say, this Japanesecolony – held a banquet in my honor.Al though the d inner was served inaccordance with old customs of the ShuriCourt, wine and vodka, called sake, thatstands for wine in these [Asian] countries,were served by sons of former senators ofthis country; none of the representatives oflocal aristocracy sat with us at the table, onlypaper pushers, pencil necks, Japaneseofficials, and kulturtraegers [culture bearers].And during the feast, when local dancersstarted to perform wonderful old dances,which were followed by one act of a greattragedy or national epopee, where a sonavenged the death of his father, I foundirrefutable proof that the Japaneseunderstand not a single word of the locallanguage, does not know and does not wantto know it; he perceives it as lower, stupid,and inferior. But because being in possessionof this land seems to him beneficial andimportant for his trade and strategy, hecaptures this land, imposes his languageupon local people, detains the king, stupefiesthe royal son with liquor and debauchery, andbleeds the country with taxes; but in front ofhimself and the world he pretends to be aphilanthropist and enlightener.

That is the history in a few words of Japaneserule in this country over the past dozenyears! That is the attitude of Japan, namely ofher present-day centralized government

towards the so-called Japanese colonies, thatis, the territories lying beyond the extent ofthe main archipelago. Looking at this royalcastle, at the castle abandoned by theRyukyuan king who had been forced to dwellin Tokyo, and today is occupied by Japanesesoldiery with uniforms reminding me of thePrussian army, I felt as if I saw Wawel orWarsaw Castle.3

Sapieha called Okinawa ‘a Japanese colony.’His testimony is a valuable contribution to thelong-standing dispute between Japanese andOkinawan scholars, specifically as to whetheror not prewar Okinawa should be discussed inthe context of colonialism.4 Of course, oneshould not take his words at face value. Afterall, his sympathies for the Okinawan peoplemight have come from the fact that he himselfcame from a country torn between threepowers and struggling to preserve its cultureand identity. But he was not alone in hisopinions. Henry B. Schwartz (1861–1945), anAmerican missionary who lived in Okinawafrom 1906 to 1910, also called Okinawa‘Japan’s oldest colony.’ But what makesSapieha’s testimony particularly valuable is thefact that he visited Okinawa in the early stagesof Japanese rule, when not many foreigners hada chance to visit Okinawa. The first twodecades of Japanese rule are described byscholars as a time of ‘preservation of oldcustoms’ (kyūkan onzon).5 Having annexed theRyūkyū Kingdom in 1879, Japan decided, forseveral reasons, to postpone structural reformsin Okinawa. Until the late 1890s, the wave ofmodernization had barely reached OkinawaPrefecture. At the time of Sapieha’s visit,Okinawa had no new infrastructure, itseconomy was backward, the society was largelyilliterate, not a single newspaper was incirculation, and the first public library wouldnot open for another 26 years. By the timeHenry B. Schwartz was in residence, Okinawa

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

3

was already a different country: the landreform had been completed and a moderntaxation system had been introduced, localautonomy had been gradually expanded andJapanese education had begun bearing fruit.Above all, Okinawan people had alreadyabandoned the dream of restoring the Kingdomand were subjected to the process ofassimilation, leading Schwartz to conclude thatthe “complete assimilation of the islands to theJapanese language and customs is only amatter of years.”6

By 1919, administrative integration with Japanwas complete and Okinawa became a fully-fledged prefecture. Japan and Okinawa seemedto have been united for good or ill. Thefollowing year, however, Okinawa plunged intoa long economic crisis that had disastrouseffects on Okinawan society. The crisistriggered a large wave of emigration tomainland Japan, where migrant workers fromRyūkyū were treated no better than theirKorean counterparts. Not only had the crisismade Japan’s negligence in modernizingOkinawa evident, but it also revealed theserious issue of Okinawan alienation,disproving the myth of ‘national unification.’Furthermore, subsequent developments provedthat Japan never hesitated to sacrifice Okinawafor the sake of national interest. One examplewas in 1945, when Okinawa was designated thebulwark protecting mainland Japan againstAmerican assault, resulting in the death ofmore than one quarter of the Okinawanpopulation; and another after the war, whenJapanese policymakers accepted the transfer ofOkinawa to the United States as a militarycolony and the cornerstone of the US-JapanSecurity Treaty. These developments aredifficult to ignore when interrogating Japan’spolicy and intentions for Okinawa in both theprewar and postwar periods to the present.

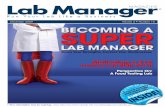

Figure 1: Prince Paul John Sapieha(first to the left) in the front of theKankaimon Gate at the ShuriCastle, Okinawa, March 1889. Thepicture was originally published inSapieha’s book Podróż na WschódAzyi, p. 189. Public domain.

Embracing Okinawa

Japanese rule in Okinawa had a touch ofcolonialism, particularly during the first twodecades. Although nominally a prefecture,Okinawa remained under a separate system ofadministration. Most of the governmentagencies and institutions, starting with theprefecture office, were manned by appointeesfrom Japan. Japanese merchants took controlover the local economy and monopolized trade

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

4

with other prefectures. Paternalism andarrogance characterized Japanese expatriates’attitudes towards the local people. BecauseOkinawa was poor in natural resources andgenerally unattractive to settlers7, itsdevelopment was low on the list of governmentpriorities. Unlike Hokkaidō, Taiwan or Korea,Okinawa had little potential for furthering one’spolitical career, and consequently, it did notattract highly qualified officials. UesugiMochinori (1844–1919), the second governor ofOkinawa Prefecture, whose attempted reformswere torpedoed by Tokyo, was an exception. Soi t was Governor Narahara Sh igeru(1834–1918), who paved the way to Okinawa’smodernization at the end of the 1890s. Mostofficials, however, bore attitudes closer to thatof Governor Odakiri Iwatarō (1869–1945), whoviewed his appointment in 1916 as a disgraceand resigned after just one week, without evengoing to Okinawa. As local journalist Ōta Chōfu(1865–1938) observed, Okinawa had beentreated like a ‘dumping ground’ for poorofficials.8

Under these circumstances, Okinawa’sdevelopment and modernization proceededslowly. In the middle of the 1920s, nearly fiftyyears after the annexation, and five afterbecoming a fully-fledged prefecture, Okinawalagged behind mainland Japan in every aspect.It had the worst infrastructure, with a verypoor network of roads, and only one, 48-kmlong railway line, as well as the worsthealthcare and education system, with virtuallyno industry. Moreover, with its quasi-colonialeconomy based on sugar cane production,developed at the cost of paddy fields acreage,Okinawa was heavily dependent on foodimportation. No other prefecture was hit by thepost-World War One economic crisis as badlyas Okinawa.

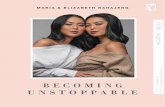

Figure 2: Ryukyu YaeyamaIriomote Island Coal Mine.Photographer unknown, Japanesesouvenir postcard c.1905-1910. Public domain. Themine operated from 1906 to 1943using convicts and workers fromTaiwan under horrific conditionsand facing rampant malaria.

The government’s policy towards Okinawa,however underdeveloped, nonetheless aimed atits integration rather than exclusion. After all,in the decades after 1879, Okinawan peoplereceived legal status equal to that enjoyed by

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

5

Japanese people on the mainland. This wascertainly not the case among the Ainu, whofaced segregationist regulations as well asattacks on Ainu culture and intense pressuresfor assimilation. Nevertheless, in light of nearlytwo decades of resistance from the Okinawanaristocracy, Japanese administrators longremained distrustful of Okinawan locals,frequently reproaching them for their allegedlypro-Chinese sentiments. When OkinawaPrefecture was finally granted suffrage in 1912,the ‘uncivilized’ islands of Miyako and Yaeyamaremained excluded from the electoral system,and Okinawa received only two seats in theDiet – fewer than other prefectures with thesame population.

The decision to postpone structural and socialreforms at the beginning of the 1880s was aresponse to local noblemen’s opposition, and ameasure taken in light of continued Ryūkyūanties to China. Some noblemen took refuge inChina, where they lobbied for Chinese militaryintervention, and many continued passiveresistance at home. To ease the situation, thegovernment pressed former King Shō Tai(1843–1901) to encourage Okinawan people toaccept Japanese ru le . The Japaneseadministration, however, correctly concludedthat its primary focus should be on rearing newgenerations of Okinawans with a focus on masseducation from 1880. Fortuitously for Japan,the Ryūkyū Kingdom had no existing system ofpublic schooling that could otherwise havebecome a source of alternative education and,by extension, a potential hotbed of resistance.

In 1880, the Okinawa Teachers College(Okinawa shihan gakkō) was established, whichbecame the cradle of Okinawan new elites. Thefollowing year, the government launched aprogram of prefectural scholarships to Japan.Schools became the primary channel ofJapanese culture and patriotic education. In1887, Okinawa became the first prefecturewhere, under the policy of promotingpatriotism, portraits of the Emperor were

introduced in schools.9 The OkinawanAssociation of Education, with its journalRyūkyū Kyōiku, played a crucial role infostering a new identity among the future elitesof Okinawan society. By 1911, Okinawa had159 elementary schools and 1342 teachers,with 96% of children of elementary school ageenrolled.10 By that time, most of the teacherswere Okinawan locals, who took up the task ofpromoting the assimilation policy. Theprefectural authorities leveraged young,enthusiastic teachers like Kuba Tsuru(1881–1943), the first woman to graduate fromthe Teachers College, and who created asensation after shedding her traditional dressfor a Japanese kimono. At the same time,however, the government was uninterested indeveloping education at the middle and highschool levels. By 1924, Okinawa had only twomiddle schools and no high schools.11 Studentswho wanted to pursue higher education had totravel either to mainland Japan or to Taiwan.

The Japanese administration was well aware ofthe potential danger posed by Ryūkyūtraditions, including tributary relations withChina from the fourteenth century forward, andtried to discourage memories of Ryūkyūanstatehood. It is not a coincidence that the newlyestablished prefecture was named ‘Okinawa’and not ‘Ryūkyū.’ The term ‘Ryūkyū,’ whichderived from the Chinese ‘Liuqiu,’ had beenbestowed by a Chinese emperor and served asa reminder that Okinawan rulers had beenvassals of China. ‘Okinawa,’ on the other hand,was a Japanese term.

Japanese ideologues made attempts to ‘de-Ryūkyūanize’ Okinawa. Between 1896 and1897, a Japanese teacher, Nitta Yoshitaka,published a long series of articles called“Okinawa wa Okinawa nari Ryūkyū ni arazu”(Okinawa is Okinawa and not Ryūkyū) inRyūkyū Kyōiku (Ryūkyū Education), where heargued that the terms ‘Ryūkyū’ and ‘Ryūkyūan’connote negative meanings of ‘foreign’ and‘barbarian,’ and should be discarded:

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

6

(…) Since we know that Okinawans belong tothe Japanese race, since we know that theyare our [Japanese] countrymen, and sinceOkinawa has broken all relations with China,there is no Chinese Ryūkyū anymore, only theJapanese islands of Okinawa. Therefore, wesha l l not use the term ‘Ryūkyūan ’(Ryūkyūjin). ‘Okinawan’ sounds much nicerthan ‘Ryūkyūan.’ The word ‘Ryūkyūan’reminds us of the past when Okinawa was a[foreign] territory belonging to Lord Shimazu.It harasses our ears l ike the ‘Dutch’(Orandajin), ‘Nankinese’ (Nankinjin) or‘Korean’ (Chōsenjin), leaving us with animpression that the Okinawans are foreignbarbarians (gaibanjin). People of Okinawamay receive the same treatment as foreignbarbarians because of this unfortunateappellation. Therefore, I urge everyone,beginning with the Society of Education, tostop using this term.12

Nitta disparaged the concept of ‘Ryūkyū’ byarguing that in the past, it also referred toTaiwan. Old Chinese chronicles recordedbarbarian customs in ‘Ryūkyū,’ such as headhunting and cannibalism, but these customs,Nitta argued, obviously did not refer toOkinawa, as the Okinawan people were pureJapanese.13 He insisted that the Okinawanpeople’s best interests lay in ending use of theterm ‘Ryūkyū’ to avoid being confused withTaiwanese indigenous peoples.

Nor did Nitta forget to reproach the OkinawanSociety of Education for naming its journalRyūkyū Kyōiku.14 The title was reportedlyproposed by Shimogoni Ryōnosuke,15 who, likeNitta, was a Japanese expatriate on Okinawa.Apparently, Japanese citizens were not all inagreement with the aggressive rhetoric of ‘de-Ryūkyūanization.’ Another Japanese teacher,Tajima Risaburō, countered: “It really does not

matter who introduces names. If we dislike thename ‘Ryūkyū’ for its Chinese origin, then whatshall we do with ‘Nippon,’ which was alsointroduced by the Chinese?”16 GovernorNarahara Shigeru, too, believed that oneshould handle the matter of Ryūkyūan pastwith a great caution. After all, the newgeneration of open-minded Okinawans, whohad granted him responsibil ity, weredescended from the former Ryūkyūanaristocracy. It was strategically unwise todisparage everything Ryūkyūan. Therefore,Narahara accepted the fact that the firstOkinawan newspaper, established in 1893,would be called Ryūkyū Shinpō, a name thatcontinues to the present.

Even so, the ‘de-Ryūkyūanization’ campaignwas quite successful. Nitta was right to predictthat ‘Ryūkyūjin,’ intentionally mispronouncedby many Japanese people as ‘Rikijin,’ wouldeventually be seen as a derogatory term. Theword came to be associated with lazyaristocrats, anti-Japanese reactionaries, or, atbest, backward losers, as portrayed byJapanese writer Hirotsu Kazuo (1891–1961) inhis novel Samayoeru Ryūkyūjin (RyūkyūanDrifters).17 Most importantly, Japan succeededin erasing ‘Ryūkyū’ as a self-identificationcategory of Okinawan people. It is worthmentioning that after World War Two, whenthe Americans tried to revive the ‘Ryūkyūannation,’ they failed as Okinawans rallied forreturn to Japan.

On the other hand, the Japanese administrationacknowledged that instead of fighting localtraditions on all fronts, it was easier toembrace and incorporate them into theirJapanese counterparts. Ryūkyūan religions, forexample, came to be recognized as archaicforms of Shintō, while Ryūkyūan heroes weredeclared Japanese heroes and enshrined inShintō shrines. The greatest Ryūkyūanstatesmen, Shō Jōken (1617–1675), GiwanChōho (1823–1876) and Sai On (1682–1761),received Japanese court ranks posthumously.

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

7

Japanese ideologists shrewdly used theJapanese figure of Minamoto no Tametomo(1139 – 1170) – the alleged father of theRyūkyūan King Shunten (1166–1237) – in orderto link the Japanese and Okinawan peoples.18

However, in the decades following Okinawanincorporation as a prefecture in 1879, Japaneseadministrators were undecided on how tohandle Ryūkyūan history and whether tointroduce the subject in schools. In 1906, adebate over history textbooks broke out inOkinawa. Local histories (kyōdoshi) had alreadybeen recognized on mainland Japan as animportant pedagogical tool that furthered theproject of nation-building, but the issue wasproblematic in Okinawa. The Japaneseadministration expressed concern that teachingRyūkyūan history might jeopardize theinculcation of “national spirit” amongOkinawan youth.19 The Okinawan Society ofEducation called for the introduction ofRyūkyūan history to the school curriculum, butgiven these concerns, and in the absence of anappropriate textbook, the project was shelved.When the authorities continued to ignore theissue, the local press accused the Japanese of“annihilating Okinawan history” (rekishiimmetsu saku).20

Okinawans had many reasons to criticizeJapanese attitudes toward their culture, butthese attitudes were not necessarily the resultof anti-Okinawan policy. Sometimes, theyreflected the lack of a decisive Japanese policy.The Japanese administration constantlyhesitated over how and to what extent toembrace Okinawa. The assimilation campaignhad little to do with kulturkampf. It primarilytargeted Ryūkyūan customs and habits thatwere perceived as signs of backwardness.Occasionally, such efforts were met withr e s i s t a n c e , a s w a s t h e c a s e w h e nschoolchildren were ordered to cut off theirtraditional topknots. But at other times, theRyūkyūan people abandoned their customs,such as the mortuary ritual senkotsu (bone-

washing), with little sign of regret. Even thecampaign against Ryūkyūan languages, whichhas been best remembered through the hōgenfuda, or ‘dialect tablet,’21 was not as radical asone can get the impression from the so-called‘dialect debate’ (hōgen ronsō) of 1940, whenJapanese scholars divided over the value ofpreserving or el iminat ing Okinawanlanguages.22 The ideological climate of thewartime mobilization, when Japan aggressivelypursued national unity, shall not becloud ourview on the whole prewar period. Ultimately,the Japanese administration not only failed toeradicate indigenous culture in Okinawa, butalso, by abolishing feudal laws and liftingconstraints in social mobility, it unintentionallycreated propitious conditions for Ryūkyūanhigh culture to spread throughout the islands,which ultimately gave rise to what is todayunderstood as Okinawan culture.23 Mostimportantly, the Okinawan people ultimatelyretained control over significant elements oftheir cultural heritage, a luxury out of reachfor, among others, the Ainu people, who lackedcontrol of their homeland and becamedependent on Japanese state patronage fortheir very survival.

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

8

Figure 3: Transporting pigs inOkinawa. Photo taken by Rev. EarlBull (1876-1974) at the beginningof the 20th century. Courtesy ofthe University of the RyukyusLibrary.

Embracing Japan

How did Okinawans during the Meiji eraperceive Japanese rule? Did they seethemselves as victims of Japanese colonization?

Okinawa’s assimilation gained momentum inthe second half of the 1890s, when China’sdefeat in the First Sino-Japanese War snuffedall hopes for the Ryūkyū Kingdom’s restorationand reinvigoration of its tributary relations withChina. Governor Narahara had just won theunconditional support of young Okinawanprogressives, largely by encouraging theestablishment of the prefecture’s firstnewspaper – the Ryūkyū Shinpō. The Shinpōturned out to be a loyal organ, rarely criticizingthe governor and his administration at a timewhen Okinawans were adopting a Japaneseidentity. Already during the war, a number ofyoung Okinawans volunteered for service in thearmy (conscription went into effect only afterthe war, in 1897).

The voices of Okinawans in the early twentiethcentury reveal pride in being Japanese,together, however, with a fear of becomingcolonial subjects. Okinawans were extremelysensitive to any attempt to call their Japanese-ness or loyalty into question. In 1903, forexample, the Ryūkyū Shinpō protested againstincluding Ryūkyūan people in an exhibition ofnative peoples for the World Trade andIndustrial Exhibition in Osaka. Ōta Chōfu wasparticularly offended to learn that theorganizers had dared presented the Okinawanstogether with the Ainu and Taiwanese ‘savages’

(seiban).24 In 1908, the Okinawan press reactedangrily to reports that the government wasconsidering a plan to merge Okinawa andTaiwan. As the Ryūkyū Shinpō warned, thiswould relegate Okinawa to Taiwan’s status as aco lony in contras t to i t s s ta tus as aprefecture.25 The famous philosopher andMarxist intellectual Kawakami Hajime(1879–1946) inadvertently sparked a wave ofcriticism during his visit to Okinawa in April1911, when he publicly praised the Okinawanpeople for their supposed indifference topatriotism.26

Once the Okinawan people accepted Japaneserule, there was no debate over the necessity ofintegration with the Japanese state. Onenotable exception was the Kōdōkai movementof 1896–97, the only attempt made byOkinawan leaders to win some degree ofautonomy for Okinawa. The movement unitedconservative noblemen, who had finally cometo terms with their defeat, and Okinawanprogressives, who opted for swift integrationwith Japan. Together, they petitioned thegovernment for a separate administrativesystem in Okinawa, with a hereditary office ofgovernor headed by former King Shō Tai. TheJapanese government, however, refused andthreatened to prosecute movement leaders.Subsequently, there was close cooperationbetween Okinawans and Japanese authorities.Years later, Ōta Chōfu, who had co-authoredthe petition, acknowledged that the movementleaders had jeopardized Japanese confidence inthe Okinawan people. 2 7 The Kōdōkaiexemplified an incipient Okinawan indigenousnationalism. Japanese policymakers, however,neutralized it, or, more precisely, redirected itto foster Japanese nationalism. In the followingyears, demands for ‘autonomy’ (jichi) appearedfrequently in Okinawan narratives. WhatOkinawan intellectuals understood by‘autonomy,’ however, was not autonomy butequality. That is, they sought the same statusand rights that people in other prefecturesenjoyed. This understanding of autonomy

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

9

required Okinawans to assimilate and provetheir ‘Japanese-ness.’

The project of assimilation was directed at oldcustoms, as well as at the ‘reactionarymentality’ of Ryūkyūan people. Iha Fuyū(1876–1947), a celebrated scholar of Okinawanstudies and a fervent advocate of assimilation,complained about the slave mentality of hispeople, by which he meant their failure toappreciate the value of unification with Japan.28

Ōta Chōfu went further, describing Okinawansprior to the Sino-Japanese War as ‘parasites’ –people without subjectivity, completelydependent on others.29 But such perspectivesdo not mean that Okinawans looked uncriticallyat Japan or that they blindly acceptedassimilation, which in Ōta’s interpretation,entailed that Okinawans should even “sneezelike Japanese.”30 Rather, they criticized Japanfor its delayed reforms, its unequal treatmentof Okinawa, and its failure to recognizeRyūkyūan cultural heritage. Ōta went toextremes in cal l ing Ryūkyūan people“parasites,” but he simultaneously held Japanresponsible for the mental state of Okinawansociety. The postponement of reforms for thesake of taming Ryūkyūan opposition, or strictadherence to the principle of ‘peace at anyprice’ (kotonakareshugi), which he saw ascharacterizing the first two decades ofJapanese rule, was a great mistake, the pricethat Okinawans were paying even five decadeslater in the 1930s.31

Assimilationist ideology left a strong mark onearly Okinawan scholarship. Iha Fuyūsubordinated his work to one goal: to provethat Okinawa was and always had beenJapanese. By doing so, he sought to helpOkinawans to overcome their inferioritycomplex and enhance their Japanese identity.He stated:

Since my early years, I have had a feeling

that there was a huge gap between theOkinawans (Okinawajin) and the Japanese(tafukenjin), and I thought that I should try tofill this gap. Later on, I wanted to build aspiritual bridge between the two peoples byproviding academic arguments thatOkinawans were part of the Yamato people. Icame to hold the belief that this would also bean expression of loyalty and patriotism to mycountry.32

Iha’s earlier scholarship was stronglyinfluenced by social Darwinism. He wasconvinced that assimilation was the best optionfor the Okinawan people, and he toured theprefecture with public lectures on ‘racehygiene,’ encouraging people to change theirlife habits. Throughout his life, he wrestledwith the dilemma of how to recognize theRyūkyūan people’s independent subjectivity asmembers of a highly civilized nation, and at thesame time, recognize them as Japanese.33 Hedeveloped the theory of ‘Japanese-Ryūkyūancommon ancestry’ (Nichiryū dōsoron), andpresented Ryūkyūan history in terms of adivorce and reunification with Japan. Theannexation of Ryūkyū, in his view, was not onlyinevitable, but also desirable for Okinawa’sdevelopment. Put simply, Japan set Okinawaback on the path of progress. His claim that the“disposition of the Ryūkyūs (Ryūkyū shobun)was a kind of liberation from slavery”34 becamehis manifesto, one that he repeated numeroustimes in his publications. Iha did not regret thepassage of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, because, as heargued, “a system that has completed itsfunction should give way to a new one, (…)otherwise it becomes a prison that enslavespeople.”35 He justified the drastic measuresthat the Meiji government introduced, arguingthat, faced with Ryūkyūan resistance, which healso saw as understandable, Japan had nochoice but to enforce “negative socialization”(destruction of statehood and local cultures).Had it not done so, unification would not have

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

10

been possible.3 6 At the same time, Iharecognized Ryūkyūan heritage as an elementthat enriched Japan, and therefore warnedagainst total assimilation. Okinawa had theright to preserve its “uniqueness,” and thiswould also serve Japan’s interests:

There is infinite uniqueness in Japan, and aninfinite amount of new uniqueness willcontinue to emerge. A nation that has thecomposure to embrace people with suchvaried kinds of uniqueness is none other thana great nation.37

Iha was convinced that the rules of evolutionwere universal and thus applied equally toJapan. Japan was changing, so “old systems”should give way. In particular, Japan was nolonger a homogenous nation, so it needed toproactively respond by setting out new valuesthat could embrace new peoples – the Ainu, theRyūkyūan, Korean, Chinese and Malay peoples– and create a great multiethnic nation. Ihawarned Japan not to indulge its old ideas of‘Japanese-ness,’ lest it risk meeting the samefate as the Roman Empire, which, faced withnew cultures, had tried to preserve its oldvalues at all costs and eventually collapsed.38

In his later years, after witnessing thedevastation of Okinawa from the economiccrisis of the 1920s, Iha’s faith in the power ofassimilation waned. He departed from socialevolutionism at the ontological level, revisedhis views on Ryūkyūan history, and depicted itin more pessimistic colors, as if Okinawa hadalways been a lonely, impoverished place,unable to control its fate. Even so, Iha neverchanged his opinion that Okinawa’s destiny wasreunification with Japan.

Iha’s younger colleagues, Higashionna Kanjun(1882–1963), Higa Shunchō (1883–1977),

Nakahara Zenchū (1890–1964) and others, allsubscribed to the concept of Nichiryū dōsoron,trying to establish stronger ties betweenRyūkyū and Japan. Higashionna might havebeen reaching too far, when, swept up innationalist fervor, he ascribed the Japanesespirit of hakkō ichiu (‘eight corners, one world,’a nationalist slogan justifying Japan’s territorialexpansion in the 1940s) to Ryūkyūanmerchants, who in the 15th–16th century hadtraded with remote countries in SoutheastAsia.39 The efforts of Higashionna and theothers to situate Okinawa within the scope ofJapanese civilization reflected their truefeelings and identity.

Conclusion

At the early stage of territorial expansion,namely before the Sino-Japanese War, Japanwas acting more like a ‘territorial state’, ratherthan ‘nation state’, eager to incorporate newpeoples who had been traditionally lyingbeyond the scope of Japanese society. Japan didnot yet have a system of modern citizenship, ora clear concept of nationality. The transitionperiod towards a nation state ended by the endof 1890s., when the Meiji government decidedto set a clear boundary separating Japan properfrom Taiwan, and introduced the firstcitizenship law (1899), which was based on thejus sanguinis principle. It is worth noting thatin the preceding years the system of koseki(household registry) functioned as an ersatz ofcit izenship, and i t covered al l newlyincorporated peoples, including even a tinycommunity of white settlers from theOgasawara Islands.40Ryūkyūan people thus, in amanner of speaking, were granted Japanesecitizenship ‘on credit,’ although initially unableto enjoy the rights and benefits it granted.Their racial and cultural qualifications forJapanese citizenship were later reconfirmed byscholars in the social sciences,41 whoserevelations, however, did not necessarily

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

11

correspond with the sentiments of everydayJapanese citizens who tended to exoticizeOkinawa.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, it isworth noting that Okinawa was nearly absentfrom Japanese colonial discourse. First of all,the Ryūkyūan peoples did not undergo theprocess of modernization with the same burdenof negative stereotypes in Japanese eyes thatthe Ainu did, the latter having been demonizedfrom the Edo era onwards. This is not to saythat the Japanese were free of racial prejudicestowards the Ryūkyūans or that they neverhappened to juxtapose the Ryūkyūans with‘savage’ Ainu or Taiwanese – just to mentionthe infamous Mankind Hall at the Osaka Expoin 1903. But generally speaking, the Ryūkyūanpeople escaped classification as ‘natives.’ No‘natives protection act’ was applied to theRyūkyūans, as it was the case of the Ainu.Indeed, many Japanese expatriates in Okinawaexperienced cultural shock. Newspapers andmagazines reported on the exotic customs inRyūkyū, confirming Japanese preconceptionsthat it was culturally al ien territory.Nevertheless, with the 1879 incorporation ofOkinawa as a prefecture, it did not registeramong Japanese people as an internal colony,and, in comparison to other Japaneseterritories including Hokkaido and later Taiwanand Korea, it was relatively absent from publicdiscourse. Hypothetically, the lackluster appealof Okinawa might have saved the Ryūkyūanpeople from being deemed ‘natives’ or ‘colonialsubjects.’ Had it been rich in oil, iron, coal,timber or other natural resources, had itoffered vast lands for settlers, then Japan mighthave coined an ideology justifying itsappropriation in the name of progress andcivilization. But this was not the case. Okinawawas simply a poor and forgotten province. Eventhe Imperial Army appreciated its strategicvalue not earlier than in 1944.

Finally, assimilation was imposed by Japan asmuch as it was willingly pursued by many

Okinawans. Okinawan leaders quickly tookmany of their cues from Japanese teachers andofficials. Okinawa’s integration with Japan,therefore, falls under the paradigm of the riseof modern nation-states, where people ofvarious cultural and social backgrounds eagerlyassimilate into so-called ‘high culture,’ whichopens the doors to citizenship, higherstandards o f l iv ing and, in genera l ,opportunities for a better life. To put it simply,the Okinawan people found ‘high culture’ inJapan. Their drive towards assimilationreflected their will to live in a modern,centralized country with a unified culture andstandardized language. The question remainsas to why they did not find ‘high culture’ intheir Ryūkyūan heritage, as well as why theydid not evoke their own indigenous nationalismas a means to resist Japan. Indeed, underAmerican military rule in the decades after1945, they organized effectively to return toJapanese sovereignty. There is no simpleanswer, but at the very least , we canunderstand, based on Ernest Gellner’stheoretical work on nationalism, that there wasnothing unusual in that. As Gellner argued,

The clue to the understanding of nationalismis its weakness at least as much as itsstrength. It was the dog who failed to barkwho provided the vital clue for SherlockHo lmes . The number o f po ten t i a lnationalisms which failed to bark is far, farlarger than those which did, though they havecaptured all our attention.42

Bibliography

Beillevaire, Patrick. “Assimilation from within,appropriation from without: The folklore-studies and ethnology of Ryūkyū/Okinawa.” InAnthropology and Colonialism in Asia andOceania. Edited by Jan van Bremen, and

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

12

Akitoshi Shimizu. Richmond, Surrey: CurzonPress, 1999, 172–196.

Higashionna Kanjun. “Hōshin o motomeyo” [Letus demand a policy]. Ryūkyū Shinpō, August14, 1943. In Higashionna Kanjun zenshū[Collected works of Higashionna Kanjun], vol.10. Tōkyō: Ryūkyū Shinpōsha, 1982, 373–374.

Hiyane Teruo. Kindai Nihon to Iha Fuyū[Modern Japan and Iha Fuyū]. Tōkyō: San’ichiShobō, 1981.

Howell, David L. Geographies of Identity inNineteenth-Century Japan. Berkeley: Universityof California Press, 2005.

Iha Fuyū. “Ryūkyūjin no kaihō” [Liberation ofRyūkyūans]. In Iha Fuyū senshū [Selectedworks of Iha Fuyū], vol. 1. Naha: OkinawaTaimususha, 1961, 272–276.

Iha Fuyū. “Ryūkyūshi no sūsei” [The current ofthe Ryūkyūan history]. Okinawa Shinbun,August 1, 1907. In Okinawa rekishi monogatari.Tōkyō: Heibonsha, 1998, 265–296.

Iha Fuyū. Ko Ryūkyū no seiji [Politics of OldRyūkyū]. In Iha Fuyū zenshū [Collected worksof Iha Fuyū], vol. 1. Edited by Hattori Shirō,Nakasone Seizen, and Hokama Shuzen. Tōkyō:Heibonsha, 1974–1976.

Iha Getsujō. “Iha bungakushi no dan” [The talkof Mr. Iha, Bachelor of Arts]. Okinawa MainichiShinbun, June 15, 1909. In: Okinawaken shi,vol. 19, 393–395.

Ishigakishi shi: shiryō hen, kindai [History ofIshigaki, compilation of documents, moderntimes], vol. 4. Ishigaki: Daiichi hōki shuppan,1983.

Kamoto Itsuko, Kokusai kekkon no tanjō:‘Bunmeikoku Nihon’ e no michi [The birth ofinternational marriages: the road to ‘civilizedJapan’], Tōkyō: Shin’yōsha, 2001.

Kyōiku nenkan [Education yearbook], vol.1/7

(Shōwa 2). Tōkyō: Nihon tosho sentā, 1983.

Matayoshi Seikiyo. Taiwan shihai to Nihonjin[The rule over Taiwan and the Japanese].Tōkyō: Dōjidaisha, 1994.

Meyer, Stanisław. “Ōta Chōfu, an Okinawanjournalist (1865–1938).” In Civilisation ofEvolution, Civil isation of Revolution:Metamorphoses in Japan 1900-2000. Edited byArkadiusz Jabłoński, Stanisław Meyer, and KōjiMorita. Kraków: Museum of Japanese Art &Technology Manggha, 2009, 397–406.

Nishizato Kikō. Okinawa kindaishi kenkyū:kyūkan onzonki no shomondai [Studies onOkinawan modern history: on the period of‘preservation of old customs’]. Okinawa:Okinawa jiji shuppan, 1981.

Nitta Yoshitaka. “Okinawa wa Okinawa nariRyūkyū ni arazu,” [Okinawa is Okinawa and notRyūkyū], Ryūkyū Kyōiku 4 (1896), 8 (1896), 10(1896), 14 (1897), 41 (1899). In Ryūkyū Kyōiku,vol. 1, 2, 5. Edited by Nishizuka Kunio. Tōkyō:Hompō shoseki, 1980.

Okinawaken shi [History of Okinawaprefecture], vol. 19, 20. Haebaru: Ryūkyū seifu,1967.

Ōta Chōfu. “Seiryoku no keitō” [The system ofpower]. In Ōta Chōfu senshū, vol. 1, 249–250.

Ōta Chōfu. “Dōhō ni taisuru bujoku” [An insultto our countrymen]. Ryūkyū Shinpō, April 7,1903. In Ōta Chōfu senshū [Selected works byŌta Chōfu)], vol. 2, 211–212.

Ōta Chōfu. “Jinruikan wo chūshi seshimeyo”[Stop the Mankind Hall!]. Ryūkyū Shinpō, April11, 1903. In Ōta Chōfu senshū, vol. 2, 213–214.

Ōta Chōfu. Ōta Chōfu senshū [Selected worksby Ōta Chōfu)], vol. 1–3. Edited by HiyaneTeruo, and Isa Shin’ichi. Tōkyō: Daiichi Shobō,1995–1996.

Ōta Chōfu. Okinawa kensei gojūnen [Fifty years

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

13

of Okinawa prefecture]. Tōkyō: KokuminKyōikusha, 1932.

Ōta Masahide. Okinawa no minshū ishiki [TheOkinawan popular consciousness]. Tōkyō:Shinsensha, 1995.

Ryūkyū Shinpō, October 27, 1906. InOkinawaken shi, vol. 19, 302.

Ryūkyū Shinpō, October 31, 1906. InOkinawaken shi, vol. 19, 302–304.

Sapieha, Paweł. Podróż na wschód Azyi [Ajourney to East Asia]. Lwów: Nakład KsięgarniGubrynowicza i Schmidta, 1889.

Schwartz, Henry B. In Togo’s Country: SomeStudies in Satsuma and Other Little KnownParts of Japan. New York: Eaton and Mains,1908.

Siddle, Richard. “Colonialism and Identity inOkinawa before 1945.” Japanese Studies 18,

no. 2 (1998): 117–133.

Smits, Gregory. Visions of Ryukyu: Identity andPolitics in Early Modern Thought and Politics.Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999.

Tipton, Elise K., ed. Society and the State inInterwar Japan, New York: Routledge, 1997.

Tomiyama Ichirō. “The Critical Limits of theNational Community: The Ryukyuan Subject.”Social Science Japan Journal 1, no. 2 (1998):165–179.

Yonetani, Julia. “Ambiguous Traces and thePolitics of Sameness: Placing Okinawa in MeijiJapan.” Japanese Studies 20, no. 1 (2000):15–31.

This article is a part of The Special Issue: Race and Empire in Meiji Japan. Please seethe Table of Contents.

Stanisław Meyer (MA Jagiellonian University, MA University of the Ryukyus, PhD Universityof Hong Kong) is lecturer at the Department of Japanology and Sinology, JagiellonianUniversity in Krakow. His main research focus is on Okinawan history and Japaneseminorities. His recent publications include a monograph on Okinawan history HistoriaOkinawy, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego (2018)[email protected]

Notes1 Paweł Sapieha, Podróż na wschód Azyi [A journey to East Asia] (Lwów: Nakład KsięgarniGubrynowicza i Schmidta, 1899).2 Ibid., 189.3 Ibid., 185–186.4 The question of colonialism extends to early modern times. In 1609, Satsuma invaded the

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

14

Ryūkyū Kingdom and imposed vassal relations on it. The extent to which Satsuma had beeninterfering in the Kingdom’s sovereignty and economically exploiting it has been a matter of aheated debate among scholars. On the one extreme, we find the view that Ryūkyū had beencolonized by Satsuma. On the other, scholars argue that early modern Ryūkyū had beenincorporated (though not entirely) into the bakuhan system. The latter view has been widelyaccepted by scholars for the past thirty years. Gregory Smits, for example, followingOkinawan historian Takara Kurayoshi, describes early modern Ryūkyū as a “foreign country(ikoku) within the bakuhan system.” See Gregory Smits, Visions of Ryukyu: Identity andPolitics in Early Modern Thought and Politics (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999),48.5 See: Nishizato Kikō, Okinawa kindaishi kenkyū: kyūkan onzonki no shomondai [Studies onOkinawan modern history: on the period of ‘preservation of old customs’] (Okinawa: Okinawajiji shuppan, 1981).6 Henry B. Schwartz, In Togo’s Country: Some Studies in Satsuma and Other Little KnownParts of Japan (New York: Eaton and Mains, 1908), 141.7 As to 31 December 1912, the community of Japanese expatriates in Okinawa Prefecturenumbered only 6368. See Okinawa Mainichi Shinbun, July 30, 1913, in: Ishigakishi shi: shiryōhen, kindai [History of Ishigaki, compilation of documents, modern times], vol. 4 (Ishigaki:Daiichi hōki shuppan, 1983), 561.8 Ōta Chōfu, Okinawa kensei gojūnen [Fifty years of Okinawa prefecture] (Tōkyō: KokuminKyōikusha, 1932), 301.9 Matayoshi Seikiyo, Taiwan shihai to Nihonjin [The rule over Taiwan and the Japanese](Tōkyō: Dōjidaisha, 1994), 48.10 Okinawaken shi [History of Okinawa prefecture], ed. Ryūkyū seifu, vol. 20 (Haebaru:Ryūkyū seifu, 1967), 775, 835, 859.11 Kyōiku nenkan [Education yearbook], vol. 1/7 (Shōwa 2) (Tōkyō: Nihon tosho sentā, 1983),ha65–ha67, ha194–ha196.12 Nitta Yoshitaka, “Okinawa wa Okinawa nari Ryūkyū ni arazu,” [Okinawa is Okinawa and notRyūkyū], Ryūkyū Kyōiku 4 (1896), in Ryūkyū Kyōiku, vol. 1, ed. Nishizuka Kunio (Tōkyō:Hompō shoseki, 1980), 129 (hereafter cited as RK)13 Ryūkyū Kyōiku 10 (1896), in RK, vol. 1, 408–11; Ryūkyū Kyōiku 14 (1897), in RK, vol. 2.107.14 Ryūkyū Kyōiku 8 (1896), in RK, vol. 1, 311.15 Ryūkyū Kyōiku 41 (1899), in RK, vol. 5, 28.16 Hiyane Teruo, Kindai Nihon to Iha Fuyū [Modern Japan and Iha Fuyū] (Tōkyō: San’ichiShobō, 1981), 18–19.17 Hirotsu’s novel, though sympathetic towards the Ryūkyūan people, outraged the Okinawancommunity on mainland Japan, who accused Hirotsu of perpetuating negative stereotypesabout Okinawa. See Ōta Masahide, Okinawa no minshū ishiki [The Okinawan popularconsciousness] (Tōkyō: Shinsensha, 1995), 321–322.18 Interestingly, there is a similar legend linking the Ainu to Japanese people. It is a story ofMinamoto no Yoshitsune, the brother of Minamoto no Yoritomo, the founder of the Kamakurashogunate. Allegedly, Yoshitsune did not die in the war against his brother, but escaped toEzo, where he became an Ainu chieftain. See David L. Howell, Geographies of Identity in

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

15

Nineteenth-Century Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 147–148.19 Ryūkyū Shinpō, October 27, 1906, in Okinawaken shi, vol. 19, 302.20 Ryūkyū Shinpō, October 31, 1906, in Okinawaken shi, vol. 19, 303.21 Hōgen fuda was used in schools to stigmatize students violating the “no dialect” rule.22 The ‘dialect debate’ was sparked by Japanese ethnologist Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889–1961)during his visit to Okinawa in January 1940, when he publicly criticized Okinawan authoritiesfor their over-zealousness in promoting standard Japanese. In response, the local presslaunched an attack on Yanagi, accusing him of failing to understand Okinawa’s specialcircumstances. For details see Hugh Clarke, “The great dialect debate: the state andlanguage policy in Okinawa,” in Society and the State in Interwar Japan, ed. Elise K. Tipton(New York: Routledge, 1997), 193–217.23 Like other countries in East Asia, early modern Ryūkyū adopted a Confucian model ofsociety with a highly elaborate system of statuses with different rights and privileges. Thefeudal system hardened cultural barriers between the aristocrats and commoners, townsmenand peasants, and between Okinawa and remote islands. The culture of Shuri and Naha,which aspired to the status of high culture, had thus a limited range of influence. It was afterthe fall of the Ryūkyū Kingdom that it started disseminating in the countryside. This processwas stimulated by the ongoing pauperization of aristocracy, who had no choice but to minglewith commoners, and, in extension, by the fall of feudalism, which was dismantled byJapanese officials.24 See Ōta Chōfu, “Dōhō ni taisuru bujoku” [An insult to our countrymen], Ryūkyū Shinpō,April 7, 1903, in Ōta Chōfu senshū [Selected works by Ōta Chōfu)], vol. 2., eds. Hiyane Teruoand Isa Shin’ichi (Tōkyō: Daiichi Shobō, 1995–1996), 211–212; “Jinruikan wo chūshiseshimeyo” [Stop the Mankind Hall!], Ryūkyū Shinpō, April 11, 1903, in Ōta Chōfu senshū,vol. 2, 213–214.25 Ibid., 301.26 Ōta Masahide, Okinawa no minshū ishiki, 316–317.27 Ōta Chōfu, Okinawa kensei gojūnen, 251–252; “Seiryoku no keitō” [The system of power], inŌta Chōfu senshū, vol. 1, 250.28 Iha Fuyū, “Ryūkyūjin no kaihō” [Liberation of Ryūkyūans], in Iha Fuyū senshū [Selectedworks of Iha Fuyū], vol. 1 (Naha: Okinawa Taimususha, 1961), 274.29 Ōta Chōfu, Okinawa kensei gojūnen, 235.30 Ōta used this expression in a public lecture with the intent to emphasize the need forwomen’s education. Because of these words, he has been remembered by future generationsas an advocate of radical assimilation. For more on this, see Richard Siddle, “Colonialism andIdentity in Okinawa before 1945,” Japanese Studies 18, no. 2 (1998): 130–131; StanisławMeyer, “Ōta Chōfu, an Okinawan journalist (1865–1938),” in Civilisation of Evolution,Civilisation of Revolution: Metamorphoses in Japan 1900-2000, eds. Arkadiusz Jabłoński,Stanisław Meyer, and Kōji Morita (Kraków: Museum of Japanese Art & Technology Manggha,2009), 397–406.31 Ōta Chōfu, Okinawa kensei gojūnen, 70–72, 288–289.32 Iha Getsujō, “Iha bungakushi no dan” [The talk of Mr. Iha, Bachelor of Arts], OkinawaMainichi Shinbun, June 15, 1909, in Okinawaken shi, vol. 19, 393–394. Note the usage of theword ‘tafukenjin’ (lit. people from other prefectures). Iha tried to avoid any suggestion that

APJ | JF 18 | 20 | 7

16

the Japanese and Okinawan peoples were of two different nations. A similar strategy can befound in Ōta Chōfu’s works, where Ōta used the word ‘honkenjin’ (people from thisprefecture) for Okinawan people and ‘tafukenjin’ for Japanese people.33 Iha had no doubt that the Ryūkyūan people constituted a ‘nation,’ and this was what madethem superior to the Ainu, whom he dismissed as ‘a people’ (he used neologisms ‘nēshon’ and‘piipuru’). He praised the efforts of the Okinawan people to highlight their Japanese-ness bydistancing themselves from inferior ‘natives.’ See Iha Fuyū, “Ryūkyūshi no sūsei” [Thecurrent of the Ryūkyūan history], Okinawa Shinbun, August 1, 1907, in Okinawa rekishimonogatari (Tōkyō: Heibonsha, 1998), 285.34 Iha Fuyū, “Ryūkyūjin no kaihō,” 274.35 Iha Fuyū, Ko Ryūkyū no seiji [Politics of Old Ryūkyū], in Iha Fuyū zenshū [Collected worksof Iha Fuyū], vol. 1, eds. Hattori Shirō, Nakasone Seizen, Hokama Shuzen (Tōkyō: Heibonsha,1974–1976), 484.36 Iha Fuyū, “Ryūkyūshi no sūsei,” 290.37 Ibid., 292, quoted and translated in Tomiyama Ichirō, “The Critical Limits of the NationalCommunity: The Ryukyuan Subject,” Social Science Japan Journal 1, no. 2 (1998): 170.38 Iha Fuyū, Ko Ryūkyū no seiji, 488–489.39 See: Higashionna Kanjun, “Hōshin o motomeyo” [Let us demand a policy], Ryūkyū Shinpō,August 14, 1943, in Higashionna Kanjun zenshū [Collected works of Higashionna Kanjun], vol.10 (Tōkyō: Ryūkyū Shinpōsha, 1982), 374.40 American and British settlers in Ogasawara were included in the koseki registry in 1882,although they were prohibited to move to mainland Japan. See: Kamoto Itsuko, Kokusaikekkon no tanjō: ‘Bunmeikoku Nihon’ e no michi [The birth of international marriages: theroad to ‘civilized Japan’] (Tōkyō: Shin’yōsha, 2001), 200–202. In Japan citizenship and thekoseki system remain closely intertwined, as the household registry serves as a certificationof citizenship. Note that whereas the Taiwanese and Koreans were covered with separatekoseki systems, and thus they received at least a promise of full citizenship in the undefinedfuture, it was not introduced to the Mandate Territories in Southern Pacific. We can observethat with the imperial expansion the institution of Japanese citizenship was becomingexclusionary.41 For early anthropological studies in the Ryūkyū Islands and the beginning of Okinawanfolklore studies, see Julia Yonetani, “Ambiguous Traces and the Politics of Sameness: PlacingOkinawa in Meiji Japan,” Japanese Studies 20, no. 1 (2000): 15–31; Patrick Beillevaire,“Assimilation from within, appropriation from without: The folklore-studies and ethnology ofRyūkyū/Okinawa,” in Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania, eds. Jan van Bremenand Akitoshi Shimizu (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1999), 172–196.42 Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983), 43.