Thick Food: A Risk-Sharing Network for Post-Fukushima Regional Planning

Transcript of Thick Food: A Risk-Sharing Network for Post-Fukushima Regional Planning

Food Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal

Volume 3, 2014, www.food-studies.com, ISSN 2160-1933

© Common Ground, Yutaka Sho, All Rights Reserved

Permissions: [email protected]

Thick Food: A Risk-Sharing Network for Post-

Fukushima Regional Planning

Yutaka Sho, Syracuse University, USA

Abstract: Japan’s post-WWII regional development strategy led to the spatial separation of production, distribution and

consumption of food and energy resources. The rural, poor and aging region of Tohoku helped provide the resources that

enabled Tokyo’s rapid urbanization and growth. The 2011 earthquake in Tohoku, however, revealed this geographic bias

that concentrated environmental, economic, social, and political risks in resource extraction areas such as Tohoku while

allowing metropolises to remain unscathed. The government’s reconstruction efforts have been slow and inadequate

while citizen groups, especially farmers, fishermen, and food sector workers have been central to the recovery. Seikatsu

Club, a food cooperative by homemakers in Tokyo, is one of them. Using both top-down and bottom-up solutions, they

ensure resilient food systems and the political representation of their constituents. Regional networks created by food

systems erase the categorical differences between production and consumption regions by sharing risks and creating

reciprocity among disparate communities. Through literary analysis and observational site visits to Tohoku, this paper

explores the effects of and antidotes to post-calamity reconstruction from the perspectives of food and regional planning.

Keywords: Seikatsu Club, Alternative Foods Movement, Food Co-ops, Regional Planning, Tohoku, Fukushima, Nuclear,

Risk, Homemaker

Introduction

n this paper I will survey the post-WWII development trend that concentrated food and

energy insecurity in Tohoku despite the efforts of planners and architects to install regional

connectivity, anticipate future changes, and to prepare for disasters. I argue that divisive

planning concentrated risks in the Tohoku region which exacerbated the effects of the meltdown

of Fukushima No.1 nuclear power plant and isolated farms and fishing ports since the

2011earthquake. I examine the work of one citizens’ organization, Seikatsu Club, which provides

an antidote to such planning by employing the food network to engage all involved to share both

risks and benefits.

Tohoku, the northern tip of mainland Japan that includes six prefectures (Akita, Iwate,

Fukushima, Miyagi, Niigata and Yamagata) has been known as a rich agricultural and fishing ground since before WWII. State-sponsored development after the war, however, rigidified

existing regional food production and consumption patterns via policies and divided the island

according to specific tasks. Food and energy production, labor provision, and the resultant

pollution, waste management and shrinking population were concentrated in rural, poor and

aging areas for the benefit of urban centers. I argue that the political and cultural ideals of the

post-war recovery era promoted an ethos of ambitious expansion, based on the false assumption

that food and energy would always be available and plentiful. Elsewhere, such development

projects that extracted resources without providing social amenities were termed socially thin

(Ferguson 2005, 198), and the term is applicable in Japan as well. Socially thin states proliferated

in rural areas of Japan as metropolitan areas grew exponentially.

In this context, the self-organized citizens’ group Seikatsu Club or SC has identified the regional gaps as the cause of the social, economic and political vulnerability and has been

attempting to reverse its effects using the food network. After the Tohoku earthquake of 2011,

SC has been active in post-calamity relief efforts using their socially thick food network against

slow and opportunistic government initiatives.

This paper will review the projects by SC and the political events, social trends and their

effects that the organization has been responding to between World War II and the Tohoku

Earthquake of March 11, 2011. I analyze thick food networks from an architectural designer’s

I

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

point of view, and my research will rely on literary scholarship, mostly by Japanese researchers

in urban planning, architecture and food cooperatives as well as SC’s own publications. To

investigate the effects of the Tohoku earthquake, informal interviews were conducted in addition

to literary analysis to supplement the findings. I visited Miyagi and Fukushima on three different

occasions, in December of 2011, 2012 and 2013, each time for two days. In Tohoku I spoke with

several SC employees, the president of a local fisherman’s union, an international nonprofit

organization PARCIC that conducts relief efforts, and several local farmers some of whom work

with SC. I have also conducted a one-hour telephone interview with each of the president of a

local fisherman’s union and the PARCIC’s Tohoku coordinator. Interviews are anecdotal and

reflect my impressions and observations only. Nonetheless I deemed it valuable and necessary to transmit testimonies from the ground that seldom reach the international audience. Their insights

and experiences proved to be productive in opening new research paths, and it is my hope that

they can be evidenced in this paper.

Figure 1: Minamisoma, Fukushima. It was a dense residential area before the earthquake.

Source: Sho, 2014.

Seikatsu Club and Food Networks in Japan

Food cooperatives in Japan originated in the post-WWII reconstruction period. During this

volatile time, food cooperatives provided a “counter balance to the increasing power of big

business interests during a period of rapid industrialization” (Maclachlan 2002:67). In parallel to

the break-up of large industrial dynasties and farm holdings by the General Head Quarters or

GHQ (the Japanese term for the occupying American government), food cooperatives

contributed to the democratization of Japan’s food industry from the bottom up in the early post-war period. While similar programs such as community supported agriculture (CSA) did not take

root in the U.S. until the 1980’s, by 1947 there were 6,500 small co-ops with the combined

membership of three million in Japan. With the start of the Cold War and the shift in spending

priorities, however, many allies of the co-ops in the GHQ returned to the U.S. and only 130

cooperatives remained active in 1950 (KSS 1997:48-49; Maclachlan 2002:68-69).

The movement for alternative governance radicalized in the 1960s against a series of

unpopular policies, and a new food cooperative movement grew out of this era. The presence of

U.S. military bases despite the end of the mandate was the main cause of the nationwide student

demonstrations. The eviction of farmers for the construction of Narita International Airport

incited intense protests that continue to this day. It is also during this time that the escalation of

production and energy extraction projects were proceeding in Tohoku (Shinoda 55). Seikatsu

Club, a food cooperative in Tokyo, aimed to offer an alternative political movement to the

20

SHO: THICK FOOD

increasingly militant student organizations.1 SC focused on food systems and deployed

communal buying power over armed force.

Alternative Food Network

Seikatsu Club is one of the most politically engaged cooperatives among about 500 food-focused

cooperatives in Japan. Since 1965, starting with 200 members collectively buying organic milk

and eggs directly from farms, SC has been working to close regional gaps via the food network.

Most of today’s nationwide 300,000 members, mainly in suburbs, are female homemakers who are both consumers and unpaid or low-paid activists. As stewards of the domestic realm, their

projects range from food safety and security to environmental sustainability, elderly care,

orphanages, microcredit banking, clean energy creation and sustainable housing construction,

among others. For instance, SC’s can recycling program in the 1970s was the first of its kind in

Tokyo (Amano 1996). For Tokyo’s 60,000 members, all vegetables are supplied by organic

urban farms in the immediate Kanto region, reducing the carbon footprint and transforming the

dense and green-less metropolitan landscape that post-war development helped create. Many of

their fish, rice and fruit come from Hokkaido and Tohoku. In 1989 they received the Right

Livelihood Award which has been termed a politically independent alternative to the Nobel

Prize. SC’s “proxies,” distinguished from “representatives” who have the authority to act

independently, elected from their political party Netto (Network) push for legislation in city halls and parliaments.

One illustration of their thick food system is the Whole Pig Project (Iwane 2012; Yokota

1991). SC purchases not just particular cuts of pork but whole pigs and, working with farmers

and processing plants, they invent products so as to use all parts of the pig. The Whole Pig

Project attempts to return agency and responsibility to both consumers and producers to control

the quality, prices, processes and distribution of food. For this reason, they call themselves

seikatsu-sha, people who engage in livelihood, and not consumers. Modern policies and regional

planning have separated spaces of production (farms in rural areas), consumption (cities and

suburbs) and distribution (highway network and commercial zones). The division creates

corresponding subjectivities of producers, consumers, and distributors. These spaces and

subjectivities become hierarchical in economic, social and political structures and risks are

disproportionately concentrated and isolated. The seikatsu-sha movement, shown in the Whole Pig Project, counters such disengagement by reconceptualizing the subject and reintegrating in

seikatsu-sha.

The seikatsu-sha movement started with the redesign of the food system. SC’s initial

distribution system guaranteed the sales of products for farmers before planting seasons. The

orders and down payments from SC members were given to farmers to buy seeds or stocks,

which stabilized costs, reduced waste and minimized risk.2 This risk-sharing relationship allows

the food system to scale up geographically and financially, not by engulfing the producers via

centralization but by establishing networks between them. SC’s networks differ from the typical

CSA model in the U.S., however, in their connections between participants. As shown in the

Whole Pig Project, SC members are integral to the production and distribution processes.

Therefore members’ dissatisfaction cannot manifest as complaints against producers as it does persistently in a CSA (Lang 2010; Stone 1998). While CSA members strive to share risks

associated with food production, their identity remains as that of passive customers. On the other

hand, SC members identify problems or opportunities for projects, set up task forces to create

1 For instance, students from the Red Army sect immigrated to Lebanon in 1971 and joined forces with Popular Front for

the Liberation of Palestine as Japan Red Army. They were engaged in numerous global terrorist attacks until the 1990s. It

was officially dissolved in 2001.2 Today the down payment system has been discontinued due to the secure reputation of SC.

21

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

plans, and conduct fund raising themselves. Their identity as seikatsu-sha is at the root of all SC

initiatives, and the food produced in this process becomes socially thick.

The social connection is created not only among members, and between members and

producers, but also among producers. In 2007, 121 producers who work with SC established their

own association called Shinseikai, and they invest part of their profit in workshops, field trips,

symposiums and festivals. They aim at information transparency, deployment of appropriate

production facilities and technology, dissemination of safe production processes to the wider

society, boycotting investment in unjust practices, and practicing sustainability in the entire food

process from production to waste management (Shinseikai 2013). One of the projects that

illustrate their commitment to information transparency is the Producers’ Encyclopedia. Every producer and product is slated to be indexed, and for each entry lists the producing location,

production process, photographs of the facility, Q&A, recipes and the history of product research

and development (Ibid). The purpose of such a project is not to attract customers, since SC

members have already committed to buying from the contracted producers. As Shinseikai

declares, the purpose is self-governance and -regulation of responsibilities and rights for

producers, as equal partners of the SC administration and the members. Their work shows that

SC producers are seikatsu-sha as well who question the established roles and boundaries in the

food industry.

SC’s networks also differ from typical infrastructural ones. Infrastructure focused

development tends to search for basic and universal networks, such as industry, high-speed

transportation and communication systems as regional enablers. In contrast, SC’s network supports excess that are seemingly secondary to economic growth such as social and cultural

programs. SC’s work also claims that specificities such as in-depth local knowledge will reduce

risk. Supported by excessive cultural practices and cultivated by specific local knowledge, food

produced by SC acquires social significance above its nutritional value and gives communities

more tools to manage risks and gain resilience in today’s precarious society.

SC’s projects were born from and responded against the post-WWII reconstruction practices

in Japan that promoted socially thin regional planning.

Post-WWII Regional Planning

Tohoku and Post-War Development

Early planners for Japan’s post-war reconstruction believed in the balanced development of rural

and urban areas instead of dividing the nation into production/ rural and consumption/ urban

regions. At the end of WWII, Japan was left to deal with 160,000 acres over 215 cities flattened by air raids: 50% of Tokyo and 60-88% of 17 cities, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Morris,

2003, Koolhaas and Obrist, 2011, 78; Tamura, 2011). 2.2 million buildings were destroyed and

9.7 million people or 10% of the population were affected (Inoue 2011). Sensing the impending

loss of the war, urban planner Takeo Ohashi, who would later become Minister of Labor, began

planning the reconstruction days before Japan’s surrender. Ohashi saw that, win or lose, cities

would need to be rebuilt and the plan needed to be installed quickly before the refugees flooded

the cities. Ohashi’s plan provided boulevards 80 to 100 meters wide and set aside 10% of the city

for green space compared to 3% in a pre-war plan to help mitigate evacuation and refugee

management in future disasters. Out of numerous affected cities 115 were designated as

reconstruction areas, nine of them in Tohoku (Koshizawa 2005; Inoue 2011). Four and a half

months after the war ended, Ohashi’s “Base Plan for Reconstruction of War-Affected Areas” became a national policy (Dept. of Interior 1945). Ohashi’s plan attempted to limit the growth of

metropolises and focus development efforts in rural regions, thus avoiding the production/

consumption dichotomy. While ensuring the efficiency and better hygiene of urban centers to

improve slum dwellings, disaster preparedness was the most important factor (Koshizawa 2005;

22

SHO: THICK FOOD

Inoue 2011), particularly valuable foresight given the recent disaster in Tohoku. Regional and

urban planning was part of the reconstruction effort, and the equal development of rural regions

was seen as integral to national recovery.

The GHQ and corroborating native government cut the scope of the Ohashi plan

substantially, however, and halved the budget by 1949. The GHQ opposed the plan by saying the

100 meter boulevards looked like a celebratory project for the winner of the war (Koshizawa

2005). To diminish the plan even further, in 1949 Joseph Dodge instituted a stringent economic

measure known as the “Dodge Line” that made Japan the frontline of the Cold War. The Dodge

Line cut public spending and instead poured resources into industrialization, including Tohoku

and benefitting the region, which in turn supplied the U.S. military in the Korean War. Originally planned to reconstruct 49,000 acres, Ohashi’s plan dwindled after commencing the work on mere

8,000 acres in 1946 (Koshizawa 2005; Kōmura 2011). Soldiers returned from the war to

crowded, still ruined cities, setting up hazardous and over-populated shanty towns. Others settled

in rural areas instead, many in Tohoku and Hokkaido as agricultural laborers.

Although the GHQ blocked the national planning policy, it promoted others that

fundamentally restructured Japanese society. The U.S. believed that economic and social

inequity lead to the militarization of the former Japanese government, and blamed the system in

which a handful of dynasties held a majority of the agricultural and industrial shares. In response,

the GHQ implemented the Anti-Monopoly Law and the Economic Decentralization Law (House

of Rep. 1947; Shinoda 2012, 48). The policies did not affect specific dynasties in Tohoku, yet

they liberate ownership and practices of agricultural, manufacturing and infrastructural industries of the region. For instance, fishing licenses were now issued to individual fisherman instead of to

corporations, and they formed consortiums of self-governing fisherman’s unions. The GHQ also

broke up large farms, and the land was redistributed to small holding farmer-owners, 70% of

Tohoku farmers, and to many unemployed workers who moved to Tohoku. The GHQ’s post-war

decentralization laws empowered individual fishermen and farmers and increased their

productivity many times over, making the region an important contributor to the Rapid Economic

Growth Era (Shinoda 2013, 48).

Fisherman’s and farmers’ unions not only represented the workers but also urged them to be

the guardians of ecological balance and geological knowledge. Especially in Tohoku whose

coastal regions are characterized by jagged cliffs, severe winter weather and moody seas, each

port and its fishing territory require deeply rooted understanding of native habitat and seasonal

changes, and strong social support. Fishermen and farmers themselves built and maintained necessary infrastructure, set the limits of fish to be sent to market to regulate price, and created

cultural events to celebrate and wish for bountiful harvests and to create social networks

(Hamada 2013). They have been and still are responsible for socially thickening the Tohoku food

production areas.

In parallel, Tohoku’s food production focus meant that its success depended on the ability to

provide for growing metropolises, especially for Tokyo. A series of Tohoku development

projects were passed in the Diet during the post-war Growth Era that lasted until around 1970.

Subsequently heavy industry grew in addition to agriculture and fishing, with accompanying

power plant projects. 33 hydroelectric power plants and six nuclear power plants were

constructed in Fukushima alone beginning in the 1950s. Increase in production and income

certainly benefitted the Tohoku people. Most funded projects, however, were designed for Tokyo’s growth. Out of 54 existing nuclear power plants today 13 are in the Tohoku region, all

of them owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Company or TEPCO and most of the produced

energy sent to Tokyo (JANTI 2013).

The Japanese archipelago straddles four tectonic plates. Most settlements have been built

along flatter seashores, susceptive to tsunamis. Flat seashores are also home to nuclear power

plants which require large property near the water source. Living with nuclear power plants

requires host towns to accept enormous risks given the inevitabilities of earthquakes and

23

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

tsunamis. Because of risks, the Japanese government, TEPCO and some scientists in support of

the construction, a group known as the Nuclear Village for their clientelism, needed to provide an

incentive. They established a set of policies termed Three Laws for Electric Power Resource

Sites that earmarked millions of yen to build public amenities such as stadiums and city halls in

host towns. The overall effect of the Three Laws was to use architecture to institutionalize and

camouflage the regional risk disparity. The subsidies, though insufficient to balance the risks

Tohoku accepted, created an atmosphere that made critique against the Nuclear Village taboo.

Expensive public buildings sat idle in depopulated rural villages (Shimizu 2012a & 2012b). The

tsunami caused by the Tohoku earthquake washed them away in 2011.

In the year of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, Ulrich Beck showed that in specialized fields such as nuclear technology and modern market, the select few are able to transfer risks to those

who are denied access to knowledge and power. While they may be managed by a select few,

modern risks cannot be predicted and they impact everyone indiscriminately and globally (Beck

1986). Yet the Tohoku earthquake proved that the negative impact could be sealed off in an

isolated region: the Nuclear Village who held knowledge and decision making power

concentrated food and energy production in Tohoku, which resulted in concentration and

isolation of damages and radiation. Post-war development in Japan had exacerbated Beck’s

already grim risk theory.

“An Advancement Plan for the Japanese Archipelago”

Japan’s spatial division during the post-war Rapid Economic Growth Era was not only supported

by the GHQ’s Dodge Line. It also aligned with imperial Japan’s colonial project that was cut

short in Manchuria (Koolhaas and Obrist 2011: 74; Yatsuka 2011: 33 and 2012: 12). During the

war, the imperial government designed several new cities in Manchuria for Japanese farmers to

settle the “frontier.” Most settlers and some of the bravest soldiers in WWII were from the

Tohoku region, and their urgent need for new territory was driven by poverty and famine back home (Yatsuka 2011: 31; Shinoda 2012: 3). After the failure of the massive continental

colonization project, it was imperative for Japan to find a domestic source of food, energy and

labor.

In parallel, some policies aimed at creating regional connectivity and decentralizing political

power to assist isolated municipalities to flourish. The rising star politician Kakuei Tanaka

published An Advancement Plan for the Japanese Archipelago in 1972 and proposed a nation-

wide infrastructural network that included bullet trains, national highway and train systems, and

computer and TV networks to connect urban areas to producer regions in the countryside

(Tanaka 1972). Expansion of farm holdings and monocrop farming were also proposed to

increase productivity and the larger market share. Hailing from the Tohoku area himself, Tanaka

wanted to reverse the flow of people, goods and money so that they would move from the center to the periphery (Ibid 78). Tanaka was elected to the prime minister’s position one month after

the publication of the book.

Tanaka’s plan, however, did not have the effect he hoped for. Infrastructural connectivity

exacerbated the concentration of labor and resources in metropolises. Many secondary cities

ended up resembling a less sophisticated version of Tokyo after focusing on the singular goal of

economic development. In rural areas, the intensification of cash crop farming has threatened the

biodiversity and financial security of the farmers, and accelerated the flow of out-going migrants.

All of these factors contributed to the depopulation of rural villages and made them ideal sites for

risky and untested facilities such as nuclear power plants (Iida and Miyadai 2011). The trend to

concentrate power supply facilities in remote, aging and depopulating Tohoku for the benefit of

Tokyo was under way, and the same urban-rural development typology was repeated nationwide. Land speculation incited by Tanaka’s plan caused an economic collapse, coinciding with the

global oil shortage in 1973. It effectively ended the Rapid Economic Growth Era.

24

SHO: THICK FOOD

Tanaka used words such as “decentralization,” “flexibility” and “free market” to describe his

plan that aimed at the empowerment of small towns. These are the same words used by

contemporary designers, planners, international development workers and anthropologists whose

goal is to regain agency from policy makers and to transfer it to people on the ground. These

words, however, are also used in neoliberal policies to describe their economy-focused agendas

(Ferguson, 2013). Contrary to the populists’ aim, neoliberal policies have been shown to reduce

public services and widen economic gaps (Feher 2007; Harvey 2007), to create socially thin

development, and, in the case of Japan, they intensified risks in Tohoku.

In Japanese metropolitan areas, the spatial separation of work and living, and production and

consumption spaces has rigidified. Physical and social separation worked well for the hyper-production and -consumption of the Growth Era. In the early 1970s, however, a series of world

and domestic events exposed risks and inequity in the Japanese society such as the global oil

shortage, the end of the Growth Era, and the liberation of women. It was no longer sufficient to

herald economic growth as the only motivator of social and spatial structuring. Yet, even though

demand for industrial goods was decreasing, energy consumption was leveling out and

population growth had slowed, Prime Minister Tanaka and others attempted to revive the

economy of the Growth Era. Around this time prominent architects designed infinitely

multiplying units as a symbol of flexible growth. 22 out ofthe 23 nuclear power stations in Japan

were built after the end of the Growth Era. Strangely the building rush and energy plants came

after Japan stopped growing.

Post-3.11 Regional Planning

The Fukushima Brand

After the earthquake on March 11, 2011, the contrast between Tokyo and Tohoku widens

proportionate to the spread of nuclear radiation. In Tohoku the cleanup and recovery remain a

continuous struggle, while the government in Tokyo pushes for the export of nuclear energy

technology to the rising economies of Asia. A little known agreement in the contract stipulates

that the seller of the technology, Japan in this case, is to process all of the radioactive waste

under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently returned from

Turkey with a signed contract to export nuclear reactors, up to eight of them. Abe is currently

under negotiation to construct 37 reactors in Russia, two in UAE, two in Vietnam, seven in India

and 16 in Saudi Arabia (Asahi 2013b). Tellingly, the only spent rod processing plant in Japan is

located in Rokkasho Village, in the Aomori prefecture in Tohoku.

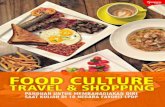

Figure 2: Apple farmer Hata with “Fukushima brand” harvest that he could not sell.

Source: Sho, 2012.

25

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

In the bullet train heading for Tohoku in December of 2012, the Geiger counter showed .062

micro Sievert/ hour in Tokyo. The Ministry of Environment guarantees the cleaning of

radioactive contaminants in areas above .230 micro Sievert/ hour. In Sōma city in Fukushima, the

air in the apple orchard that supplies the fruit and the juice to Seikatsu Club had .376 micro

Sievert/ hour that day. But the radioactive substances inside the apples measured below the

regulated level, the farmer Toshio Hata confirmed. Many farmers and fishermen in Fukushima

including this orchard cannot sell their “Fukushima brand” no matter what the radiation level is.

The aftermath of the Fukushima disaster attests that the trust in food safety depends more on the

perception of safety than facts.

The president of the local fisherman’s union Seigo Sato has been living in emergency housing in Jusanhama in Miyagi prefecture. Sato and his union is one of the non-member

producers that collaborate with SC since the disaster. The union is part of the prefecture-wide

consortium, and each union member passes specific knowledge of the local sea to subsequent

generations. By accumulation of individual fisherman’s work, Miyagi has always been one of the

most productive fishing prefectures in the country. Because individual union members lost all

they owned in the disaster, reconstruction of the industry proved a Herculean task.

The fishing industry in Miyagi is facing a substantial policy change that threatens Sato’s

efforts. The mayor of Miyagi together with the conservative Japan Business Federation proposed

a law that allowed fishing rights to be issued to large commercial corporations (Asahi 2013a).

Under the banner of “Return the sea to all Japanese citizens,” the policy sounds ethical when

understood as the redistribution of fishing certificates which have been monopolized by individual fishermen since after the war (Takagi 2007). However, fishermen and SC, who are

collaborating to block this law, fear that the policy will return the democratic fishing industry to

the hegemonic control of the pre-WWII era (Hamada 2013; Sato 2013). Many Tohoku fishermen

have used fishing rights to leverage their position against the construction of nuclear power

plants in their communities. Once the policy comes into effect, TEPCO, the government and

large fishing corporations will be exempt from compensating the local population, rendering null

the Three Laws for Electric Power Resource Sites. The mayor’s office of Miyagi prefecture will

not have to pay for the port reconstruction because private corporations will be able to construct

their own. The policy that was once struck down resurged, thanks to the disaster.

Whenever SC representatives come to visit, Sato serves fresh catch from the sea. In

hindsight, all the delicacy he generously shared might have been contaminated. In August 2013

TEPCO admitted the continual leakage of 300 tons of highly radioactive water from Fukushima No.1 into the sea since the disaster, and it has not been stopped as of this writing (Tabuchi 2013).

A conundrum in Japan today is what to do with Fukushima-brand food. Some say that adults

should eat them: because they are responsible for construction of the nuclear plants without

proper emergency measures in place; that the domestic food industry needs to be revived; and

that safe imported food needs to be saved for children who are more sensitive to internal

radiation. Others call such a proposal naïve, citing the cost of universal health care that would be

required to care for the sick (atPlus 2012). The fact that the argument is being had at all shows

that food and energy systems involve societal and ethical investigations. Yet policies and

development plans are written by scientists and bureaucrats of the Nuclear Village.

Today Japanese citizens are excluded from the decision making processes worse than before

the disaster. The Fukushima news coverage has been strictly controlled, and Reporters Without Borders reported that Japan’s press freedom ranking has gone down from 22nd to 53rd after the

earthquake (Reporters Without Borders 2014). This is due to the Official Secrets Act that passed

the Diet on October 28, 2013 that allows the Japanese government to censor all information as it

sees fit. In the meantime reconstruction efforts have stalled in Tohoku because construction

materials and personnel have been deployed to Tokyo for the preparation of the 2020 Olympics

(Asahi 2014).

26

SHO: THICK FOOD

Space, Risk Sharing and Seikatsu Club

Seikatsu Club and Tadashi Maruko, a strawberry farmer in Miyagi’s areas hardest hit by the

earthquake, are searching for an alternative restructuring method for Tohoku’s food industry.

They issued a “Strawberry Stock Option” which promises to use 30% of the proceeds for

recovery: mending cultural artifacts such as ancient festival floats used for the harvest

celebration; training young strawberry farmers; and helping the strawberry industry recover. In

return, investors receive socially thick fruit in the mail in the next harvest season. Similar to SC’s

Whole Pig Project and western CSA model, consumers share the risks that the producers

normally bear alone. Unlike most CSA programs, however, the scope of the project expands

beyond the provision of local organic food and supports excessive cultural programs. The

recovery of cultural artifacts rooted in specific region such as festival floats, costumes and masks will encourage recovery efforts and sustain their heritage in post-quake Tohoku.

Figure 3: Strawberry farmer Maruko in his reconstructed hothouse.

Source: Sho, 2012.

Another site of SC’s relief efforts is refugee housing. In Shinchi temporary housing in

Fukushima, SC organizes monthly open-air markets. Without these events people tend to dwell

on their misfortune in solitude and never step outside of their private units (Arai 2011). But on

this market day people came out to shop for fish and vegetables, and children made rice cakes on the terrace. The relief donations from the SC members amounted to 2.7 million dollars and it is

growing. SC’s activities in Tohoku are mostly for non-members and non-partner producers, as

open-air markets, the collaboration with Sato, and donations exemplify. The work of SC is the

product of solidarity born of sharing risks with those far away.

27

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

Figure 4: SC’s market at Shinchi temporary housing, Fukushima.

Source: Sho, 2011.

A custom of sharing land that helps mitigate risk have a long history in Japan. Iriaichi is a

type of commons, privately or communally owned but always communally managed, provides

necessary resources such as firewood and space for foraging and animal grazing. This tradition

mediates the over-extraction of natural resources through explicit or implicit regulations and also

constructs socially thick communities that support those in need (Kijima, Sakurai and Otsuka

2010; Yamashita 2011:2). Keiyaku-kō is a special type of commons in Tohoku that is both a

contract and a governing body that oversees land and forest management, fishing practices,

community regulations and the curation of ceremonies and festivities. Kō leaders were once

representatives of their community parallel to elected officials. Usually kō benefits are limited to

the members. After the Tohoku earthquake, however, in reaction to the slow government relocation of the refugees to permanent housing, kō land owners in many parts of Tohoku have

consolidated their holdings and opened them to the entire community so they may move and

rebuild together (Tsuda 2011: 66). Kō members have always collaborated in agriculture and

fishing in Tohoku. Their co-ownership over space and food are now extended to benefit the

region at large. In essence SC’s work could be understood as the modern equivalent of this old

practice of solidarity.

Conclusion

Food networks can be effective tools in the construction of solidarity across regions, classes, and

between those at risk and those who are not. Partially this is because food is essential for our

biological survival, but food does more than feed. The cultural critic Hiroki Azuma recently

claimed that Japanese youth is turning to an animal state (Azuma cited in Osawa 2008:5). Severed from social ties, responsive only to the flashing lights and saturated colors of video

games, and pausing the game only to eat and relieve themselves, Japanese youth are like animals,

says Azuma. If food is only for survival, it would simply exacerbate the animal era we live in.

This paper has tried to show that food connects people and spaces not when it provides

sustenance but when it is excessive, specific and socially thick. Separated by desires for

efficiency and growth in the post-war recovery era, spaces of food production, distribution and

consumption have been assigned tasks and accompanying risks that were presumed to be a

necessary sacrifice. The discipline of regional planning has been a part of this divisive

28

SHO: THICK FOOD

development. The Tohoku earthquake and the subsequent nuclear disaster at Fukushima No.1

have revealed that post-war food system impacts the political, social, economic and cultural

dimensions of our lives in addition to the biological. Thick food allows us to share risks with

those who are far away, who belong to different social groups and those with varying

representations.

The Tohoku earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear disaster have revealed the vulnerability

of food as well. It is common sense that food is exposed to elements such as tsunamis and

radioactivity, as it is cultivated over vast tracts of land, takes different forms and scales, and is

grown across all natural environments of water, soil and on trees. Food in Tohoku is also at the

mercy of a government bureaucracy miles away in Tokyo, and its safety depends more on social perception than scientific facts. On the other hand, scientific facts that should liberate food are

written in an opaque language by technocrats, policy makers and energy companies, such as

members of the Nuclear Village. Those who understand the language are the ones who determine

where to build unwanted facilities (Beck 1986).

Natural and man-made disasters occur cyclically in Japan, creating seasons of a peculiar

kind. What shocks us about Fukushima is its large scale of destruction repeatedly shattering a

specific locale. Fukushima’s destruction tells us that the goal is not to eradicate disasters, a futile

endeavor, but to create a socially thick state that ensures equity in management and sharing of

risks. Such consideration was absent in the post-war regional planning that enabled the Tohoku

disaster. The problem is even more difficult today because the types of risks that we face are not

bound by space or time. Climate change, nuclear radiation and social inequalities affect future generations yet to be born, with whom we are struggling to form an alliance (Osawa 2011). This

un-imaginability of our peers makes the construction of solidarity difficult. The development of

thick food production is one of the tools available to help re-conceptualize solidarity, for

individuals, regions, across the globe and in time.

Acknowledgement

I thank the president of the Jusanhama Fisherman’s Union Seigo Sato, PARCIC Tohoku

coordinator Risa Hikata, and Isamu Arai and Yoshihiro Akasaka of Seikatsu Club Cooperative

for their generous contributions. James Setzler’s editorial support was invaluable.

29

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

REFERENCES

Amano, Masako. Who is Seikatsu-sha?: History of Citizens’ Self-Governing Movement (Tokyo:

Chuko Shinsho, 1996).

Arai, Isamu. Interview with the designated Tohoku reconstruction project liaison of Seikatsu

Club during the visit to Miyagi and Fukushima. December 19 and 20, 2012.

Asahi, 2013a. “Ishinomaki Fishing Recovery Special Zone Begins. Fishing Rights for Industry.

Aims for New Model for Reconstruction.” [石巻水産復興特区始まる 企業に漁業権

再生モデル目指す] September 2, 2013.

_______. 2013b. “Exporting Nuclear Technology, Contract Signed with Turkey Despite

Concerns, Prime Minister Colluding with the Industry.” [原発輸出、懸念置き去り ト

ルコと正式合意 首相前面、企業と一体] October 31, 2013.

digital.asahi.com/articles/TKY201310300781.html?_requesturl=articles/TKY20131030

0781.html&ref=comkiji_txt_end_s_kjid_TKY201310300781

http://www.asahi.com/shimen/articles/TKY201309010293.html

_______. 2014. “(3 Years After East Japan Disaster) ‘The Olympic Detrimental to Recovery’

Say 42 Mayors of Affected Regions.” [(東日本大震災3年)「五輪、復興に逆風」

6割 被災42市町村長へ朝日新聞社調査] March 3, 2014.

http://www.asahi.com/articles/DA3S11008507.html?iref=comtop_list_ren_n09

atPlus symposium “Earthquake, Nuclear Power Plants and New Social Activism” in atPlus issue 09, August 2011 (Tokyo: Ota Publishing).

Avenwell, Simon Andrew. Making Japanese Citizens: Civil Society and the Mythology of the

Shimin in Postwar Japan. University of California Press, 2010.

Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage, 1992. Originally published in

Germany as Risikogesellschaft, 1986.

Department of Interior, the Committee of Post-War Reconstruction, Tokyo, Japan, “The Base

Plan for Reconstruction of War-Affected Areas.” [戦災地復興計画基本方針] Takeo Ohashi, committee chair. In Post-War Reconstruction Document No. 3. Ministry of

Construction, Urban Planning Department, 1958, 1-4. National Diet Library, 318.2-

Ke119s. http://rnavi.ndl.go.jp/politics/entry/bib00699.php#content

Feher, Michel. “The Governed in Politics,” in Nongovernmental Politics, ed. Michel Feher with

Gaëlle Krikorian and Yates McKee (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 12-27.

Ferguson, James. “Humanity Interview with James Ferguson pt. 2.” Interview by editorial

collective in Humanity Magazine web, June 12, 2013. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. http://www.humanityjournal.org/blog/2013/06/humanity-interview-

james-ferguson-pt-2-rethinking-neoliberalism

Hamada, Takeshi. Fishing Industry and Disaster. [漁業と震災]Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 2013.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

House of Representatives, Tokyo, Japan, “the Act of Economic Decentralization Act no. 207.”

[過度経済力集中排除法] Dec. 18, 1947. http://www.shugiin.go.jp/itdb_housei.nsf/

html/houritsu/00119471218207.htm

Iida, Tetsunari, and Miyadai, Shinji. Departure from the Nuclear Power Society: Toward

Renewable Energy and Community Self-Governance. [原発社会からの離脱:自然エネ

ルギーと共同体自治にむけて] Tokyo: Koudansha Gendai Shinsho, 2011.

Inoue, Makoto. “Post-War Reconstruction Planning: Memory and Heritage of Japan

Revitalization, Series1.” [戦災復興 – 日本再生の記憶と遺産] Nippon Keizai Shinbun,

August 10, 2011.

Iwane, Kunio. A Lifestyle Called Seikatsu Club: Philosophy That Makes Business out of Social

Movement [生活クラブという生き方-社会運動を事業にする思想]. Tokyo: Ohta Books, 2012.

30

SHO: THICK FOOD

Kijima, Yoko, Takeshi Sakurai and Keijiro Otsuka. “Iriaichi: Collective versus Individualized

Management of Community Forests in Postwar Japan.” Economic Development and

Cultural Change, Vol. 48, No. 4 (July 2000), pp. 867-886. The University of Chicago

Press, accessed October 20, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/452481

Kōmura, Kenyu.“Effects, Shortcomings and Reflections on Post-Disaster and Post-War

Reconstructions: Do Not Repeat the Failure of Tokyo in Fukushima.” [震災復興・戦災復

興の成果・失敗とその反省を踏まえて~東京の失敗を東北に持ってくるな!~] Presentation at the Japan Institute of Country-ology and Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, May 30, 2011.

http://www.jice.or.jp/oshirase/201110111.html

Koolhaas, Rem and Obrist, Hans-Ulrich. Project Japan: Metabolism Talks. Koln; London:

Taschen, 2011.

Kosizawa, Akira. “Post-War Reconstruction Planning, its Value and Heritage” [戦災復興計画の意

義とその遺産] in Toshi Mondai, Vol. 96, Issue 8, August 2005. Tokyo: Tokyo Institute of Municipal Research, 2005. http://www.timr.or.jp/shinsai/docs/06_koshizawa_

toshimondai0508.pdf

Lang, K. Brandon. “The Changing Face of Community-Supported Agriculture” in Culture &

Agriculture Vol. 32, Issue 1 pp. 17–26, 2010 by the American Anthropological

Association.

Maclachlan, Patricia L. Consumer Politics in Postwar Japan: The Institutional Boundaries of Citizen Activism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

_______. “The Struggle for an Independent Consumer Society: Consumer Activism and the

State’s Response in Postwar Japan.” In The State of Civil Society in Japan, edited by

Frank J. Schwartz and Susan J. Pharr, 214-232. New York: Cambridge University Press,

2003.

Maki, Norio. History of Housing in Disasters: People’s Movement and Residency [災害の住宅誌:

人々の移動とすまい]. Tokyo: Kashima Publishing, 2011. Morris, Errol. The Fog of War. Sony Pictures Classics, 2003.

Osawa, Masachi. The Impossibility Era. Tokyo: Iwanami Bunko, 2008.

_______. "Possible Revolution 2: Commune of Fellowship and a Pseudo "Sophie's Choice"."

AtPlus 08, (May, 2011): 4-17.

Reporters Without Borders, “World Press Freedom Index 2013,” accessed March 3, 2014

<http://fr.rsf.org/IMG/pdf/classement_2013_gb-bd.pdf >.

Sato, Seigo. Telephone Interview on October 2, 2013.

Shimizu, Shuji, 2012a. "The Damage is 15 Times the Benefit: “Questioning Federal Policies”

Series- with Shuji Shimizu." Okinawa Times via WEB Shinsho 1, Asahi Shinbun

Digital (March 1, 2012): June 23, 2012. _______, 2012b. Looking Back at Nuclear Power Plants: What It Means to Live in Fukushima

Today [原発とは結局なんだったのか -いま福島で生きる意味]. Tokyo: Tokyo Shinbun, 2012b.

Shinoda, Hideaki. “Construction of Modern Nation State in Japan and Post-War Peace Building:

Case of Tohoku.” [日本の近代国家建設と紛争後平和構築: 東北に着目して (平和構築

としての日本の近代国家建設: 研究序論)]. IPSHU Research Series no.47, 2-58 (2012-

05). Hiroshima: Institute for Peace Science, Hiroshima University, 2012

<http://ir.lib.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/metadb/up/kiyo/ipshu/ipshu_47_2.pdf>. Accessed February 9,

2014.

Shinseikai < www.s-shinseikai.com>. Accessed February 9, 2014. Stone, Pat. "Hoes for hire. Community supported agriculture." Mother Earth News No. 114: 54-

59 (November/December 1988).

31

FOOD STUDIES: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL

Tabuchi, Hiroko. “Tank Has Leaked Tons of Contaminated Water at Japan Nuclear Site” New

York Times, August 20, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/21/world/asia/300-

tons-of-contaminated-water-leak-from-japanese-nuclear-plant.html

Takagi Committee for Fishing Industry Improvement. “Recommendation for Expedited

Implementation of Fundamental Improvement Strategies for the Fishing Industry to

Protect Fish Consumption Culture.” Japan Economic Research Institute. Published July

31, 2007, http://www.nikkeicho.or.jp/result/水産業改革髙木委員会 提言発表/ Tanaka, Kakuei. An Advancement Plan for the Japanese Archipelago [日本列島改造論]. Tokyo:

Nikkan Kogyou Sinbunsha, 1972. Tsuda, Daisuke. “Can Social Media Regenerate Tohoku?: Reconstructing Autonomous Tohoku

Communities.” Hiroki Azuma, ed. Shiso Chizu Beta Vol. 2. Tokyo: Contextures, 2011.

Yamashita, Utako. The Transformation of Communal (Iriai) Forests in Today’s Japan. [入会林

野の変容と現代的意義] Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2011.

Yatsuka, Hajime, ed. Metabolism Nexus [メタボリズム・ネクサス]. Tokyo: Ohmsha.

_______, 2012. Metabolism: The City of the Future. Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011.

Yokota, Katsumi. I among Others. Yokohama: Seikatsu Club Seikyou Kanagawa, 1991.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Yutaka Sho: Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New

York, USA

32