'Quick Strike' moves into area where Marines were kiled - DVIDS

Therapeutic Performance: When Private moves into Public

-

Upload

southwales -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Therapeutic Performance: When Private moves into Public

1

Therapeutic Performance: When Private moves into Public Thania Acarón, BC-DMT, LCAT, R-DMP Mayagüez, Puerto Rico & Cardiff, Wales [email protected] www.thania.info Citation: Acarón, T., 2017. Therapeutic Performance: When Private Moves into Public. In: V. Karkou, S. Oliver and S. Lycouris, eds., The Oxford Handbook for Dance and Wellbeing. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.219–238.

Abstract: This chapter explores whether the use of choreography, dance technique and performance in dance/movement psychotherapy (DMP) hinders or enhances the therapeutic process and how these modes of practice might impact the patient/client’s wellbeing. The inherent cathartic nature of performance proposes a tension between the healing facets of therapeutic material that emerges from dance and questions of ethics around client confidentiality. The therapeutic performance, as developed within a DMP context, is defined and described using examples from the author's practice as an active performer and dance movement psychotherapist. The use of choreographic tools, and specific dance styles in DMP are explored as potential interventions, taking into consideration its benefits and risks to the therapeutic relationship. A case study is presented which makes the connection between the therapeutic performance and patient/client wellbeing. Through making these connections, this chapter aims to explore an underdeveloped area within the field, focusing on the therapeutic potential of public performances of movement created during the sessions, to maintain a clinical balance between the private self within the session, and the public self that others witness. Introduction

Dance movement psychotherapy (DMP)1 developed from the alliance between dance practices and

psychotherapeutic frameworks. The pioneers of DMP came from dance and performance

backgrounds, and their work encouraged the development of an approach that connects body and

mind, and introduces the body as the focus of all experience and the principal agent in the healing

process. Wellbeing encompasses the fulfilment of our own human potential while developing the

resources to cope and transcend adversity (World Health Organization 2014). Movement within

DMP acquires communicative, emotional, symbolic and expressive qualities that take on an 1 The term for the profession in the UK is dance movement psychotherapy, although in the United States the term is dance/movement therapy. The UK version of the term and British spelling will be utilised in this chapter.

2

integrative role within the individual or group. DMP pioneers viewed “mastery or technique as

functional and aesthetic platforms for expression” (Fraenkel 2006, p.1). This included teaching

dance technique to clients to create a basic nonverbal vocabulary. To many dance movement

psychotherapists however, the use of choreography or dance technique within a therapeutic

framework may seem like a contradiction. Duggan (1995) states that some dance movement

psychotherapists argue that conventional dance steps “are inauthentic and keep individuals away

from their feelings” (p.229). Fraenkel (2006) also states that the term ‘dance technique’ elicits a

critical response which echoes the ambivalence of whether structuring a therapeutic process can

thwart a patient/client’s2 own voice. Arnheim (1992) argues that aesthetics are an “indispensable

trait” of human behaviour, and can be useful, even at times necessary within therapeutic contexts.

Choreography and performance, as major elements of dance hence exhibit a controversial role

within DMP, which will be unpacked in this chapter. I will focus on delineating the potential and

limitations of the use of choreographic approaches, movement techniques and performance

opportunities within the DMP setting: how dance performance functions as a therapeutic tool. The

therapeutic performance in DMP will be analysed as an intervention taking into consideration its

benefits and risks to the therapeutic relationship and patient/client wellbeing. I will use examples

from my practice to illustrate certain applications of choreography within DMP and will refer to

debates relating to ethical issues surrounding such applications.

As a dance movement psychotherapist, performer and choreographer who is still creating work for

the stage, my artistic background has offered many new perspectives that promote further

communication between the ramifications of dance/movement as a discipline. However, I have felt

the importance of also illustrating similarities and distinctions between artistic, educational and

therapeutic processes and their application. DMP holds many differences from dance education that

have been a way to demarcate the DMP field from its inception and align it within

psychotherapeutic contexts. Many authors, including Panhofer (2005), Schmais (1970), Duggan

(1995), Meekums (2002) and Hayes (2010) illustrate the fine and precarious line between dance

technique, education and DMP. In order to help my students and workshop participants understand

these differences, I created a working diagram (see figure 1) that encompasses the components of

therapeutic processes in DMP. In summary, it is the focus on the therapeutic relationship between

2 I use the words patient/client in slashes in order to allow for the terminology to be applicable to a variety of settings. In the case of schools and my work with normal neurotic adults, I refer to them as clients, whereas in hospital settings they can be referred to as patients.

3

practitioner and client, and the structures and interventions based on the client's needs and from the

client's movement and verbal contributions that distinguishes DMP from other body-based or

movement-based practices. Using this diagram, a movement-based practice can be distinguished

from DMP. A delicate exception, however, would be body psychotherapy and somatic psychology,

which would also use the body as the main focus of treatment, but may not use dance-based

practices as a mode of intervention, and also may include touch. Considering differences between

DMP on the one hand and somatic psychology and body psychotherapy on the other may require

more of an in-depth theoretical and practical discussion which is outside the scope of this chapter,

since their path and formation are indeed complementary to DMP.

DMP has traditionally been aligned with improvisational processes – the patient/client being in the

moment in movement, the bringing forth of movement as a description of existence, of being. The

objective is to develop awareness of and with the body (Csordas 1993 in Tantia 2012), letting it be a

protagonist within the psychotherapeutic process, allowing expression to occur at a bodily level.

The role of teacher or choreographer is abdicated, making a transition from teaching to therapy:

judgement is suspended, aesthetics become secondary and the patient/client's movement repertoire

becomes the focus (Schmais 1970). This bi-directional process between therapist and patient

initiation and movement dialogue shapes the therapeutic relationship and lays down the foundations

for the therapeutic process, facilitating the delineation of therapeutic objectives in treatment.

The research focus on choreography, performance and the use of dance technique in DMP sessions

was originally introduced by DMP pioneers. However, apart from earlier writings from the pioneers,

there is very little on choreography as a therapeutic tool (Victoria 2012). Duggan (1995) uses

choreography as a flexible structure that both honours the clients', in this case adolescents’

contributions (versus a therapist/choreographer-directed process) and provides a therapeutic

framework. Her work was one of the first mentions of choreographic dance structures as a

therapeutic tool with adolescents. Swami & Harris (2012) and Hayes (2010) conducted their

research on DMP with dancers, Hayes (2010) describing how DMP sessions influenced dancers’

choreographic ability and technique while Swami & Harris (2012) focusing on body image and

body awareness. Jeppe (2006) suggests a model that incorporates music, poetry and DMP with

adults with mental illness, including several final performances that emerged from her work.

Allegranti (2009) uses creative multidisciplinary approaches to DMP that culminated with a film

4

generated by her clients' work. Bacon (2007) discusses the role of Jung's active imagination and

Gendlin's focusing method within performance contexts in DMP, arguing in favour of the

therapeutic processes involved in dance-making. Victoria (2012) proposes a “choreo-therapeutic

model using the psychodynamic concepts of externalisation, transformation, and re-internalisation

in dance choreography to work through and heal inner states” (p. 168). She exposes a process where

choreo-clients, as she terms them, are led through a creative process within sessions, using

performance as a therapeutic tool. Her methodology, which is still in development, indicates why

choreography has a wide potential to be used for therapeutic purposes. Victoria's (2012) model is

perhaps a great starting point for continuing a discussion and developing practice-based models

within DMP.

In terms of the use of specific dance forms, there has been a variety of applications to DMP. Capello

(2007) reviews the American Dance Therapy Association International Panel’s discussion during

their 2007 annual conference. Several DMP delegates from all over the world focused on different

elements of dance performance used both historically and contemporarily within the DMP

profession. Capello's article encapsulates the integration of folkloric forms into DMP contexts as a

way of using familiar and symbolic aspects of dance that are meaningful for the patient/clients'

cultural realm in the service of therapy. Figure 2 shows a summary of the statements provided by

the international panelists invited to this panel to speak on this context, and lists their mentions of

benefits of using their dance forms within DMP sessions. Some panelists offered examples of work

with specific populations, while others selected specific dance forms and their applicability.

Although not all have published research in each individual use of stylised and cultural dance forms

as far as their practice and the specific usage and percentage of application would need to be delved

in further in each country's case, this chapter presents these as possibilities into further research.

The Therapeutic Performance

I define a dance performance as a set of movements, either choreographed and structured in

advance or improvised in the moment, intended to be seen by an audience. The creator(s) of the

movement may develop a piece using material generated from their own internal states, their

therapeutic process, various aesthetic vocabularies, inspiration from the environment (landscapes,

buildings as in site-specific works), images, poems, other visual media, music or any combination

5

of the above. As Bacon (2007) remarks, “performance-makers working with therapeutic tools enter

an imaginal world whenever they begin the creative process” (p.20). There are endless relationships

between the creation of material, the creator and the audience. This is not to leave out the fact that

even in the private sphere, a patient/client may “perform” for the therapist – assuming roles that

they think will please him or her, or may adopt and act out various roles as defences. In many ways

this can be true in reverse, and the therapist may perform roles for the client. The private sphere

within therapy contributes to a sense of mutual construction of reality. Within the arts therapies3,

assuming different roles, acting out symbollically, and embodying metaphor is instrinsic to the work

(Ellis 2001). The concept of performativity, especially in regards to gender, has been much explored

within the social sciences. Butler (1999) claims that every human being performs their own roles

that are inscripted in the body (especially in terms of gender) within social contexts. One may even

question – what is private and what is considered public? Although my intention is not to provoke a

debate around this issue, I highlight this aspect to present that even if, throughout our lives we

manifest infinite types of private and public performances, for the purposes of this chapter, the

therapeutic performance is different – it is a client-led process of creation – the private self, or

private selves that are expressed through the therapeutic relationship make conscious decisions to

create dance/movement material choreographed for an outside audience.

Some dance movement psychotherapists incorporate performance as part of their therapeutic

interventions, while others use dance technique as a way to address the therapeutic objectives

within sessions (some examples are summarised in Figure 2). Within this chapter, I illustrate the key

aspects of the therapeutic performance within DMP as follows:

1. Therapeutic performance is a part of a patient/client/group process of dance

movement psychotherapy.

2. The movement material is generated from patient/client/group work within the

sessions.

3. The process of generation and selection of material is client-led.

4. Concepts from artistic dance-based processes are in dialogue with therapeutic

connotations.

3 Arts therapies is the British and European term that encompasses music therapy, art therapy, dramatherapy and dance movement psychotherapy. Please see the European Consortium for Arts Therapies in Education (www.ecarte.info) for more information. In the United States, this category is termed Creative Arts Therapies and includes psychodrama and poetry therapy. Please see the National Coalition for Creative Arts Therapies Association (www.nccata.org).

6

These aspects correlate to Diagram 1 in that the therapeutic performance4 (and embedded within it

all the movement codes used to create it) remains within the Structures/Interventions, which are

hence generated from the patient/clients, and tied into the therapeutic objectives of the session.

Therapeutic performance is one of many interventions that emerge from the sessions, and serve as a

vehicle to structure and clarify the material the patient/clients bring.

Background

During my work as a dance movement psychotherapist in schools, the question came up often: “Can

I do something for the Holiday Show this year?” The student’s gaze turned to me expecting for

permission to bring the private into the public arena. My role was established as a dance movement

psychotherapist but the school demanded a show for the parents and community, and year after year,

as I remained the only “dance/movement person” within these settings, this performance

expectation started to become a ritual. My initial compromise was to hold ‘performance groups’

separate from those therapeutic in nature. These performance groups had technique classes as part

of their formation, and performed several times a year. I also held different types of sessions:

individual therapy sessions, dyads and group therapy sessions, juggling a myriad of roles within this

setting. The settings' expectations of a performance for the community felt at first as an insult to my

professional career – I felt I had to defend the privacy of DMP and the distinction from dance as a

performing art and communicate this to the school – to administration directly, and then to the staff

through professional development workshops. Additionally, I needed to explain this further to my

young clients, since part of our therapeutic process was defining how movement could benefit them,

and how different our sessions were from a dance class or dance training. This blurring of

boundaries in others enforced an internal boundary in myself: I needed to clarify these different

roles within me in order to create safety and ethical lines within the setting. After transitioning to

work community-based contexts with adults, and teaching DMP in higher education and in South

America and Europe, I realised that therapeutic performances were quite common amongst

practitioners, yet employing this tool needed careful unpacking and analysis.

Therapeutic Rationale and Benefits of Performance 4 Therapeutic performance has also been utilised by psychodrama and dramatherapy4, and within dramatherapy has been termed therapeutic theatre.

7

Developmental psychologists and psychoanalysts, such as D.W. Winnicott (1971), argue that the

existence of an Other shapes us from infancy and ultimately defines our sense of self. The Other is

represented by a multiplicity of roles throughout our lives. In a formal performance situation, the

Other becomes the audience and the situation is taken into a hyper-reality: All eyes descend on the

performer. There is no escape from criticism or approval. There is no stopping or re-doing. An

external view of the performer is immediately injected into what was previously a dual or closed

group process. In the practice of Authentic Movement, awareness of oneself is often developed

through both being witnessed (by the therapist or fellow group therapy members) and witnessing

our own experience (Musicant 1994, 2001; Adler 1996). Therapeutic performances to some extent

can fulfil some of these experiences. The challenge, however, is that the audience-as-witness is not

trained in DMP or familiar with the therapeutic process involved. The audience member will not

necessarily hold the patient/client, sustain and contain the emotional charge spent on what is

presented, might not be willing to manage the intricacies of the patient/client's world. In a public

performance, both therapist and client take a risk plunging into the unknown hands of its audience

members, and need to be prepared for all the configurations of reactions and feedback that are

inherently involved. On the other hand, Jeppe (2006) reports a sense of confidence, and social

affirmation as aftermath of the therapeutic performance which links performance to patient/client

wellbeing. The effects of witnessing a community’s acceptance, and overcoming struggles and

challenges to put up a specific product on stage become instrumental for a patient/client’s personal

growth.

Decision to perform

The process of deciding to get up on 'stage' (whether it is an open community room or a theatre)

involves a unique process of preparation initiated by a self-reflective process and assessment of

readiness and willingness. For many artists, even after decades of training, there is always the

moment of anxiety before a performance. In the case of some patient/clients, where there is little to

no performance background, the decision to purposefully place themselves in an anxiety-ridden

situation may seem controversial and perhaps contraindicated. Pre- and post- performance

assessments can ultimately determine its effects on the patient/client and therapeutic relationship.

8

Duggan suggests that the decision to perform depends upon the establishment of a performance

contract versus a therapeutic contract (personal communication, 27 August 2012). She mentions that

patient/clients (especially in school-based settings) have self-referred solely to participate in a DMP

group for performance purposes. Their desire to perform fuelled their initial contact. She has hence

formed specific performance groups with this output in mind. This is different from the cases in

which the contract is initially a therapeutic one, in which there is a decision to perform that has

emerged from the process. Both cases are included within my definition of therapeutic performance

in DMP.

In my practice, I constantly offered my patient/clients the option of not performing, and had to be

susceptible to possible signs of them feeling overwhelmed, not ready or assess potential

psychological harm as in the case of my children clients that had been previously traumatised. The

work within the sessions needed to provide support and as Winnicott (1971) terms it, a holding

environment and a therapeutic relationship had to be well established before any decisions to

perform were discussed. Many conversations and movement explorations constantly fed the

possibility and intention behind performance and the client's readiness was monitored until the

moment before the performance.

The Therapeutic Material in Movement

The way in which the body is able to express its inner workings through has many pathways in

DMP. Each therapist has their own style of working according to the populations' needs. From my

training in the United States, my approach has encompassed strong elements both from Authentic

Movement and Marian Chace (Lewis 2004), and I have been able to interweave my experience as a

performer and dance educator as well. This section describes some of the choreographic tools I

have employed in my sessions that have culminated in therapeutic performances.

Along with Victoria (2012), I too found extreme validity in DMP Pioneer Trudi Schoop's claim that

structuring unconscious material that had been brought to the conscious into movement phrases was

a useful way of being able to organise thoughts and being able to ground perspectives. “The process

of formulating dance movement sequences served the function of slowing down the expressive

process and in this way allowed more time for the exploration of inner conflicts. Through

9

choreographing conflicts, Schoop believed the individual could gain some control, insight and

mastery over his or her problems.” (Levy, 2005, p. 64). Peggy Hackney (2002) defines phrasing as

“perceivable units of movement which are in some sense meaningful” (p. 239). Hackney (2002)

speaks about 'practicing' new patterns as they are brought to awareness, in an effort to re-train the

body to discover alternatives ways of being. In my work, I use the making of phrases of movement

as a tool in order to bring awareness to an individual's behavioural patterns. These themes of

repetition, patterns or ‘stuckness’ can be explored within the space, with specific movements the

patient/client generates. This tool is often used in dance education frameworks, yet, within the

concept of therapeutic performance in DMP, can be employed as a form of crystallisation of internal

into external states, to aid the identification of intra-psychic conflicts. It can help the client construct

multiple perspectives with which to view a particular issue.

Other choreographic tools that involve explorations of space can be particularly useful. For example,

in the case of one patient/client choreographing for the group, or in group choreography, the use of

spatial formations, or the use of mapping of the space and allocating movement and meaning to

specific locations can be useful. This tool was particularly useful in my work with children in foster

care, in which we explored transitions between the homes of biological parents to the foster homes.

Pathways can be drawn on the map to symbollise a client’s personal events or indicate ways in

which transitions between the events or places took place which the patient/clients can then enact

through movement.

Incorporating dance technique into sessions can also be used to generate therapeutic movement

material and expand the patient/client’s movement repertoire. Maintaining clarity of intention, as

Hackney (2002) suggests, helps structure our world. Through employing dance technique, however,

the focus of sessions may become more “educational”, involving teaching specific steps or

combinations which may then be applied to the choreography. This is not to say that teaching does

not occur at times during therapy. With some clients, psychoeducational tasks may be incredibly

beneficial. The challenge lies in the delicate balance between the patient/client's needs, their

therapeutic process and what elements within the dance technique may address them appropriately.

However, the use of social dances and partner dances may enforce gender stereotypes and need

careful consideration. Duggan (2005) argues that reinforcing traditional gender roles and dynamics

may perpetuate oppressive societal norms. In these cases, the therapist can investigate creative ways

10

in which these traditional dance forms and gender roles can be challenged, providing a safe place

for differences in gender expression and sexual orientation.

The aesthetic value of dance technique is intrinsically linked to dance performance and the

choreographic process. The choreographer employs a specific set of aesthetic values that shapes

their vision of the work. This is a difficult challenge, as the integrity of the patient/client’s material

must not be sacrificed to put on something pleasing to the eye for a performance. It is, nevertheless,

a rich discussion to have with patient/clients around what they consider aesthetically pleasing.

Depending on their therapeutic framework, dance movement psychotherapists may become more

directive in their interventions. Dance movement psychotherapists might also teach choreographic

concepts and structures to form the material as well (i.e. canon, spatial formations, specific

structures such as theme and variation or ABA formats). They may also propose complementary

movements that may support, contrast or expand the patient/client’s movement repertoire (Sandel et

al. 1993). Some dance movement psychotherapists from more of a psychodynamic stance, however,

would adopt a more therapist-as-witness role within session, not moving with clients, but holding

their experience in their bodies and attuning to the client’s movement.

Another device that can facilitate the generation of movement material is the videocamera.

Although videotaping might not be allowed in some settings, and patient/client consent is essential,

it can become a useful tool for self-reflection and documentation of the process. Managing the

anxiety of a “technological eye” is not an easy process when working with a group or individual

client, since enough time has to be allowed in sessions for patient/clients to feel comfortable with its

presence. There is little mention in DMP literature about the use of video with the exception of

Allegranti (2009), who combines film-making as joint part with DMP with self-referred adults. Art

therapist Henley (1992) describes the process and benefits of using videotaping with

developmentally disabled clients within art therapy, adding an embodied way of both patient/client

and therapist assessment during art-making. Henley (1992) states that “video can increase

awareness of self and others through body animation, facial expressivity and interpersonal relating

when taped sequences are played back as a prelude to drawing” (p. 443). Within my practice,

videotaping clients and film-making have been an incredibly useful tool. An example of this was

demonstrated by an adolescent client with selective mutism in my school-based therapy group. As

part of a collective group film project, she was able to speak to the camera and manage her severe

anxiety around adults, whilst providing a creative venue for social interaction and inclusion.

11

The Therapeutic Relationship in Performance

Every element of the creation, development, performance and evaluation of therapeutic

performance material poses both a threat and an opportunity to the therapeutic relationship.

Clarkson & Pokorny (2013) argue that one of the most effective types of therapeutic relationships is

the working alliance relationship, where client and therapist “join forces” to engage in mutual

cooperation (p. 32). The therapeutic relationship is hence negotiated throughout the performance,

ebbing and flowing within a system of unknowns (i.e. audience reaction, client’s perceived ‘success’

of the performance, effect on the relationships with the therapist). Duggan (1995) conveys the

struggle to get her adolescents' choreography to the stage, and how performance impacted the lives

of the youngsters' lives within their school community. As with many of my patient/clients that

chose to perform their therapeutic material, performance day becomes a synopsis about how the

patient/client copes with stressful or difficult situations, which is one of the pillar elements of

wellbeing. Some of my clients were incredibly determined to show their mastery. Some debated

whether to perform almost seconds before going on. Some groups became fragmented due to the

stress, or grew more cohesive. However, all new that they had to make a clear choice to perform

which could be rescinded at any point. As a therapist, these moments when a patient/client(s) were

the most vulnerable became opportunities to offer support without judgment, and model ways of

coping with stressful events.

Debriefing a performance with a client was one of the most fascinating and pivotal moments in our

therapeutic process. They described, drew or moved how they embodied exposure, criticism,

anticipation, self-doubt, pride, anxiety and/or mastery. The therapeutic performance does not end

when the curtain falls or the audience stops clapping; it becomes embedded in the relationship and

therapeutic development of the individual and marks an important point of growth, break or

transition in their life.

Ethics, Benefits and Risks

12

Therapeutic performance in dance, as a process developed within the DMP context carries several

ethical issues. Confidentiality is essential. Within the therapeutic performance process in DMP,

measures need to be taken to protect the confidentiality of the patient's specific history. In this way,

since dance is inherently nonverbal and movement can be interpreted in an infinity of ways, this

brings forth an advantage to the use of this art form. The same may apply to the consideration of the

performance space, which may include from the common treatment room with family and friends,

to the school auditorium, or it may be a general area. The choice of space is important in preserving

a client's confidentiality if he/she belongs to a mental health setting. Videotaping also involves a

heavy component of confidentiality and care as to who has access to the material.

Patient/client safety is also an important consideration – psychological, physical and emotional

safety. In terms of the physical dimension, for example, props decided to be used in performance

should be chosen according to the capabilities of the patient/clients. Patient/clients with sensory

integration problems should be considered, where the extreme noise or over-stimulation can be

potentially detrimental to the client. This was often the case when I worked with children in the

autistic spectrum. If they decided to perform, it was in small group settings or with family members.

In other cases, collaboration with therapeutic assistants was crucial, since they could monitor

specific individuals within a group and be able to leave the premises if needed in order for a child to

have a break from the overstimulation. Additionally, measures of the patient/client's stamina,

condition and bodily abilities must always be monitored, since the adrenaline of performance can

sometimes work against even the most trained of bodies. Emotional and psychological safety should

also be the priority when selecting therapeutic material. This is not to say that movement cannot

betray even the most private of matters. The interpretation of what is seen by the audience cannot be

controlled – but the way in which patient/clients choose their own material can be guided and

discussed. The rationale behind the therapeutic performance is to provide a context of expression.

The patient/client may feel too vulnerable about certain material, so it is important to consider the

potential benefits and risks. Gender and sexuality need also to be considered among the dynamics of

groups and to promote psychological safety amongst members regardless of their gender identity

and sexual orientation within the group.

Snow et al. (2003) reiterated that the drama therapist should not foresake their clients’ needs in

order to prioritise their own artistic ambitions. This also applies to the distinct roles of

13

choreographer and therapist. I must admit there were times in which I noticed during sessions, the

choreographer role emerged in me. It was a moment of internal reflection and I identified my own

countertransferential feelings as an artist being called into question. At times I would find myself

wanting the choreography to ‘look good’ or yearning to adjust or correct a client’s steps, and needed

to hold back. I understood it was my need; the aesthetics wanting to influence the process. Brown

(2008) argues that dance movement psychotherapists must maintaining their own dance practice

alive and consistent in order to address this. Brown (2008), Boris (2001) and Myers et al. (1978)

recommend the maintenance of creative practices as a powerful burnout prevention and professional

development tool for practising creative arts therapists. Brown (2008) states that: “creative arts

therapists must continue to embody the creative spark that first birthed our respective disciplines

and first drew individuals to this creative field” (p. 201). I agree that nurturing our embodied

practices and continuing to create artistic work or developing our movement skills can benefit

ourselves as practitioners and our clients; the fulfilment of our own performance needs are realised

and are kept separate from the patient/client process.

In the next section, I will address a case from my practice in which therapeutic performance was

implemented in order to paint a picture of its application in DMP.

CASE STUDY

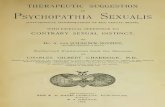

Image 1. Body SoxTM (Not actual client)

14

Photo by: Ellen Ríos Padín (Puerto Rico) Dancer: María de Lourdes Biaggi

I had been working at school-based setting as a dance movement psychotherapist where I had

individual and group work for children aged 5-13. Sylvia, a client I had been seeing in individual

sessions, much to my surprise, asked me if she could be in the end of the year performance at an

after-school programme I had been working in. Sylvia was twelve years old, very verbose and

extremely precocious, with incredible responsibilities of taking care of her younger siblings. Sylvia

already at twelve thought of herself as a 'caretaker', and was able to rationalise and justify her

situation in an adult-like manner. She had profound issues with her body image and was very self-

conscious about her body. She had a reputation within her peers as the “tough one”, and it made me

extremely curious that by performing, she was inviting others to see a vulnerable side of herself.

Sylvia had chosen as part of her sessions to use a Body SoxTM (see figure 3), stating she felt safe

inside it. The Body SoxTM is a type of human sized encasing made of lycra in which people can

crawl inside and their body be covered completely, with an option to cover or reveal their face. It

allowed Sylvia a way to cover her body while she moved. Sylvia often used the Body SoxTM with

her head uncovered, finding comfortable ways of moving and exploring the space around her. The

lycra provided proprioceptive feedback and she felt held by this flexible structure, providing her

with the physical boundary she craved from the adult figures in her world, and the nurturance she

lacked everywhere else.

I always had the option of a videocamera available to clients, and Sylvia agreed we videotape5 her

sessions in order to reflect on how she moved through the improvisations. The video footage was

only to be seen by both of us, and her parents consented that if needed, my clinical supervisor

would have access to the material. Selecting the material for the performance was the most difficult

process. Sylvia also had a way of masking her emotions in movement in a similar fashion as she

used her language and adult-like behaviour to create alliances with the adult figures in the

programme and alienate her peers. Some of her improvisations always included the theme of hiding

using external objects such as scarves. She had limited affective range in her facial expressions, and

5 Authorisation for videotaping was obtained from parents and Sylvia since it was an educational setting. Parents

signed consent forms that authorised the use of videos in sessions, for therapeutic purposes and for clinical supervision. At the end of the year, the children were given copies of all the sessions videotaped for them to keep.

15

she used many props to cover her face. One of our therapeutic objectives was to be able to

encourage a deeper involvement with the strong feelings she had about herself, her body, and the

incredible burden of responsibility she carried.

Sylvia decided that she would perform her material with her head inside the Body SoxTM, and I

remember her expressing that this way, she didn't have to worry about her clothes and accidentally

revealing any skin or showing her face, a clear representation of the strong protective measures she

had been applying even throughout the sessions. Sylvia selected a very emotional song that had

come up in our closing movement ritual that expressed the struggle between what was being

demanded of her and what she should do, and that as expressed in the lyrics of the song, the “need

for a pause”, to think for herself. The process of choreographing her piece involved certain shapes

in conjunction to the music, and also included some structured improvisation.

Before the performance, Sylvia remained pretty calm, but at times was a bit ambivalent about her

upcoming performance. When the time came, she decided to perform, much to the surprise of her

community. Her performance brought tears to everyone's eyes. Even though she was covered in the

Body SoxTM, the emotionality and deep connection to her struggles were evident. The audience held

her experience, and the energy felt in the room reaffirmed the power of her movement. When she

finished dancing, she poked her face out of the Body SoxTM and smiled. Her performance marked

the development of our work together – to be able to show vulnerability and emotion through

movement. To her, in the confined boundary inside the Body SoxTM, she didn't have to be a “tough

girl”, or the caretaker – she could just be Sylvia. Some staff members came to me afterwards and

commented on how different Sylvia had portrayed herself versus her usual self within the school.

They were surprised at her expressivity, and glad she had a place where she could explore this

within DMP. As we debriefed the performance, she expressed she was pleased with what she did,

and discussed the possibility of doing other dances without the Body SoxTM in the future. I took this

as a gesture that her therapeutic performance had benefited her therapy in DMP; she was beginning

to be ready to go deeper within herself, and without her “mask”. A beginning of her journey towards

wellbeing.

This case study presents the cathartic aspect of therapeutic performance in dance and its

possibilities for the development of the therapeutic relationship. The patient/client led the process,

chose what she wanted to portray to her audience, what facets of herself she felt comfortable

16

exposing. The Body SoxTM provided a protective barrier in her case, yet the shapes created were

able to transmit much more than she probably anticipated. I interpreted the final detail of peeking

out of the Body SoxTM to take a bow as a sign that she was willing to show a part of herself to the

outside world. My role was not that of a choreographer, looking for the aesthetics of it, but more as

a source of support and offering a contained environment where she could have the independence of

her own voice. The process of selecting the material and shaping it involved asking questions both

verbally and through inviting her to move certain emotions she wanted to portray or offering other

improvisations to develop her movement vocabulary as well, in conjunction to her theme.

Sometimes we used the song she selected, and other times we used different types of music to elicit

other efforts and dynamics. The video provided us with the continuity and external eye, as she was

able to further select movement sequences from her previous sessions she was drawn to. The video

footage also allowed her to view herself, and I guided the process of expressing feedback about

seeing herself on camera, suggesting ways in which she could view herself without the overly

critical eye she had about her body.

The case of Sylvia is only one out of the many powerful stories that came out of the use of

therapeutic performance within my DMP sessions. At times, the experiences were not always

positive, especially with particularly “honest” audience members, whose feedback was not always

censored and at times pretty destructive. However, even the difficult comments or feedback were

useful tools within the context of our sessions. The performances were a hyper-reality of the outside

world, with the exception that this was a world situation I could navigate and process with my

patient/client while being there. I could embody with my client a live mise-en-scene, and I could

incorporate the myriad of aspects within this experience into our therapy. The therapeutic

performance is one of the few ways in which the dance movement psychotherapist and client both

interact with an external audience.

Conclusion

Creativity is “the doing that arises out of being” (Winnicott et al, 1986, p.39). If the therapeutic

relationship is prioritised, choreographic tools and dance forms/styles which are underpinned by

movement techniques, with or without explicit aesthetic objectives can be made available as

therapeutic interventions. The practitioner, however, needs to be aware of how these interventions

17

serve the patient/clients' therapeutic objectives and be also sufficiently familiar with choreographic

principles and dance-based artistic concepts and structures. The dance movement psychotherapist's

previous experience in choreography and performance can be extremely beneficial to the process, if

the tools that are brought forth are used to clarify a patient/clients' artistic vision and are continually

being checked for fulfilment of the patient/clients' needs. At all times, ethical guidelines must be

upheld and the balance between education and therapy need to be maintained. Since a therapeutic

performance can occur or be suggested at any time during the therapeutic process, the challenges

and benefits to the client are intrinsically interwoven. To create something that links to a

patient/client’s life, to witness a client being seen by others, and to have a patient/client witness

themselves being seen by an outside community can have a powerful effect, which can be

incredibly constructive and/or possibly destructive to their process. Although the case study

presented indicates that the therapeutic performance enhanced the client’s wellbeing, this may not

be the case of all therapeutic performances. However, the times when it has been implemented in a

safe way and through the considerations expressed in this chapter, the benefits to the patient/client

have been immense. It is a delicate balance and risk with an enormous amount of potential

therapeutic opportunities which needs to continue to be explored and researched.

(Not actual client) Photo By: Ellen Ríos Padín (Puerto Rico) Dancer: María de Lourdes Biaggi

18

Figure 1. Design by: Claudia Peces This diagram illustrates the therapeutic process interrelations that distinguishes DMP from other dance/movement-based practices

REFERENCES

Adler, J., (1999). The Collective Body. In: P. Pallaro, ed., Authentic movement: moving the body, moving the self, being moved : a collection of essays.. London; Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley, pp.190–208.

Allegranti, B. (2009). Embodied performances of sexuality and gender: A feminist approach to dance movement psychotherapy and performance practice. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 4(1), 17–31.

Arnheim, R. (1992). Why aesthetics is needed. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 19(3), 149–151.

Boris, R. (2001). The Root of Dance Therapy: A Consideration of Movement, Dancing, and Verbalization vis-à-vis Dance/Movement Therapy. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 21(3), 356–367. doi:10.1080/07351692109348940

Brown, C. (2008). The importance of making art for the creative arts therapist: An artistic inquiry. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 35(3), 201–208. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2008.04.002

Butler, J. (1999). Bodily Inscriptions, Performative Subversions. In J. Price & M. Shildrick (Eds.), Feminist Theory and the Body: A Reader (pp. 416–422). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Capello, P. (2007). Dance as Our Source in Dance/Movement Therapy Education and Practice. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 29(1), 37–50. doi:10.1007/s10465-006-9025-0

Clarkson, P. and Pokorny, M., (2013). The Handbook of Psychotherapy. East Sussex and New York: Routledge.

Dragon, D. A. (2008). Toward Embodied Education, 1850s-2007: Historical, Cultural, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives Impacting Somatic Education in United States Higher Education Dance (PhD Thesis).

Duggan, D. (1995). The“ 4’s”: A dance therapy program for learning-disabled adolescents. In F. J. . Levy, J. Pines Fried, & F. Leventhal (Eds.), Dance and other expressive art therapies: When words are not enough (pp. 225–240). New York and London: Routledge.

Espenak, L. (1981). Dance therapy: Theory and application. Springfiel, Illinois: Thomas Publishers.

European Consortium for Arts Therapies in Education. (2013). Retrieved from www.ecarte.info

Fraenkel, D. L. (2003). Dance / Movement Therapy: The LivingDance Approach. In S. S. Fehr (Ed.), Introduction to group therapy: a practical guide (pp. 162–166). New York: Haworth Press.

Fraenkel, D. L., & Mehr, J. D. (2006). Valuing the dance teacher and dance technique in dance/movement therapy. In 41st Annual Conference American Dance Therapy Association: Choreographing Collaboration: A Joint Conference with NDEO. American Dance Therapy

Association.

Gilbert, A. G. (1992). Creative Dance for All Ages: A Conceptual Approach. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance.

Hackney, P. (2002). Making connections : total body integration through Bartenieff fundamentals. New York: Routledge.

Hayes, J. (2010). Dancers in a dance movement therapy group: links between personal process, choreography and performance. Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

Henley, D. R. (1991). Therapeutic and aesthetic application of video with the developmentally disabled. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 18(5), 441–447.

Jeppe, Z. (2006). Dance/movement and music in improvisational concert: A model for psychotherapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 33, 371–382.

Levy, F. J. (2005). Dance/Movement Therapy. A Healing Art. (Revised.). AAHPERD Publications. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED291746

Lewis, P. (2004). The Use of Marian Chace’s Technique Combined With in the Depth Dance Therapy Derived from the Jungian Model. Musik-, Tanz Und Kunsttherapie, 15(4), 197–203. doi:10.1026/0933-6885.15.4.197

Meekums, B. (2002). Dance movement therapy: A creative psychotherapeutic approach. Sage.

Musicant, S. (1994). Authentic movement and dance therapy. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 16(2), 91–106. doi:10.1007/BF02358569

Musicant, S. (2001). Authentic Movement: Clinical Considerations. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 23(1), 17–28. doi:10.1023/A:1010728322515

Myers, M., Kalish, B. I., Katz, S. S., Schmais, C., & Silberman, L. (1978). Panel discussion: “What’s in a plié: The function and meaning of dance training for the dance therapist’. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 2(2), 32–33. doi:10.1007/BF02593065

National Coalition For Creative Arts Therapies Association. (n.d.). Retrieved December 3, 2014, from www.nccata.org

Panhofer, H. (2005). El cuerpo en psicoterapia: Teoría y práctica de la Danza Movimiento Terapia. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Schmais, C. (1970). What dance therapy teaches us about teaching dance. Journal of Research in Health, Physical Education, 41(1), 34–35.

Shoop, T., & Mitchell, P. (1974). Won’t you join the dance? A dancer’s essay into the treatment of psychosis. Palo Alto, CA: National Press Books.

Snow, S., D’Amico, M., & Tanguay, D. (2003). Therapeutic theatre and well-being. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 30(2), 73–82.

Tantia, J. F. (2012). Mindfulness and Dance/Movement Therapy for Treating Trauma. In Rappaport, L. (Ed.), Mindfulness in the Creative Arts Therapies (pp. 96–107). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Victoria, H. K. (2012). Creating dances to transform inner states: A choreographic model in Dance/Movement Therapy. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 7(3), 167–183. doi:10.1080/17432979.2011.619577

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. New York: Basic Books.

Winnicott, D. W., Winnicott, C., Shepherd, R., & Davis, M. (1986). Home is where we start from: essays by a psychoanalyst. New York: Norton.