The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside, Dandelion, December 2013

Transcript of The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside, Dandelion, December 2013

Isabella Streffen, ‘The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside’, Dandelion 4.2 (Winter 2013) 1

Article

The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

Isabella Streffen

/

__________________________________________

Isabella Streffen is an artist and Early Career Research Fellow at Oxford Brookes University. She works across media to examine and respond to fundamental problems of politics, perception, technology and narrative in contested sites. Her doctoral research at Newcastle University focused on military visioning technologies and strategies and their use in fine art practice. Recent projects include residencies at Hadrian's Wall, the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Library of Congress. She is co-curating 'Show Me The Money: images of finance 1700 to the present' (touring in 2014-15).

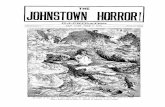

Isabella Streffen, Fylingdales in Winter (2012) porcelain, plastic, light, milk, eggs, glass (photo: R. Hollinshead)

VOLUME 4 NUMBER 2 WINTER 2013

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

2

Orange Herald, Violet Club, Yellow Sun, and Blue Streak: the names are reminiscent of tubes of oil paint or jars of pigment. In fact, they are all coded titles for military projects in the UK during the 1950s, many of which were concealed in top-secret rural bases like RAF Spadeadam in Cumbria. How have contemporary artists responded to the revelation of these once-classified schemes, their hidden locations, and the threatening presences that they engendered? These artists share many of the concerns voiced in Rachel Carson’s 1962 polemic Silent Spring, which drew attention to the impact that these secrets could have on our ecology and played an important role in shaping contemporary environmental consciousness. From the wilds of Orford Ness to the archives of the Library of Congress, via hard-boiled eggs and mysterious swamps, this essay proposes a brief introduction to some twenty-first century artistic practices that reflect on the twentieth century’s fall-out. In The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro writes of the underlying horror of the English countryside, an invisible threatening presence that lurks beneath the bucolic idylls, wild places and contented villages. It is the same horror as occurs over and over again in Carson’s Silent Spring:

The most alarming of all man’s assaults upon the environment is the contamination of air, earth, rivers and sea with dangerous and even lethal materials. This pollution is for the most part irrecoverable; the chain of evil it initiates not only in the world that must support life but in living tissues is for the most part irreversible.1

Widely attacked by the scientific community when it was published, Silent Spring makes explicit the links between wartime gas attacks and chemical experiments, and the sustained assault on the environment in the name of agriculture. Carson observes:

This industry is a child of the Second World War. In the course of developing agents of chemical warfare, some of the chemicals created in the laboratory were found to be lethal to insects. The discovery did not come by chance: insects were widely used to test chemicals as agents of death for men.2

In a series of chapters that discuss soil, insects, the air, and water sources, Carson catalogues the damage of a series of devastating bio-chemical offensives. Her work in unpicking the complex relationships between governmental and agricultural industry interests could be read as a harbinger of the military-industrial-entertainment complex and of the corroded relationships between industry and government that tax so many contemporary thinkers.

Silent Spring is a story of death, of denials from the authorities, of unexplained events, mysterious illnesses: it is a story of secrecy, of fear, of contamination, of abuse of power and of conspiracy. Of not knowing what is in the water, the air, or the food. Of dreading to think what the government or industry might be doing to you, without you knowing. It is a story of being afraid to dissent for fear of persecution. It is the same horror that Louise K. Wilson reveals in her 2003 film Spadeadam, where the artist uses archaeological survey equipment to expose the traces of Blue Streak – the UK’s secret experimental ballistic missile and rocketry research program – concealed for decades among the northern pine forests. Peter Sloterdijk gives the birth of this horror an exact date: April 22nd 1915, the occasion of the first large scale chlorine gas attack by German troops at the Ypres Salient.3 At precisely six pm, one hundred and fifty tons of chlorine were discharged into the air, billowing

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

3

into a gas cloud six kilometres wide and one kilometre deep. A new age of warfare – that of the ‘atmoterrorist’ – had begun. Death was the evidence of this invisible presence. Less than three decades after the horror of the Ypres Salient, and only a few short years after the end of the World War II, the use of similar technologies for crop spraying insecticides and herbicides was so common as to be unremarkable. According to Paul Virilio, each technology bears within it the seed of its own catastrophe.4 The aerial technologies that heralded the ‘atmoterrorist’ bring more than a new dromoscopic vision in which speeding forward and aerial perspective is combined, however.5 They also generate what I call techno-lust: the infatuation with technologies that comes at an enormous financial cost. The issues of money, and who profits, and the invisible networks of procurement and weaponry are constantly sifted by contemporary artists (examples range from Hans Haacke’s institutional critiques to Mark Lombardi’s schemes to David Young’s drone industry workshops), and they connect strongly with Carson’s concerns about the cost of profit in lives, be they animal, avian, microbial, marine or human. Using highly emotive language Carson openly accuses industry and government of collusion, and demands that a democratic account be answered:

It is also an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged. When the public protests, confronted by some obvious evidence of damaging results of pesticide applications, it is fed little tranquilizing pills of half truth.6 Who has made the decision that sets in motion these chains of poisonings, this ever-widening wave of death that spreads out, like ripples when a pebble is dropped into a still pond? […] Who has decided – who has the right to decide – for the countless legions of people who were not consulted that the supreme value is a world without insects, even though it be also a sterile world ungraced by the curving wing of a bird in flight? The decision is that of the authoritarian temporarily entrusted with power.7

Carson’s work could be said to operate as an ‘institutional critique’ of science policy, mirroring the type of strategy increasingly employed by artists during the 1960s on aesthetic matters. Although Silent Spring’s main impact on contemporary art practice has been as a catalyst for a widespread (non-specialist) debate on ecological matters, it is also possible to uncover traces of Carson’s method in artists’ practices that expose experts and their supporting structures to public and non-specialist scrutiny. It is here that an echo of Carson can be heard in artworks that do not have environmental activism at their cores. Posing a Carsonesque challenge to prevailing authorities and narratives through the presentation of observed data is a key strategy for contemporary artists responding to the once-secret military experiments of the Cold War, and their consequences. Looking at the practices and histories of Trevor Paglen, Joanna Griffin and Suzanne Treister (all artists currently working and exhibiting internationally) offers some insight into this strategy. Trevor Paglen Trevor Paglen’s work, like Carson’s, relies on observational evidence: where Carson revealed the remnants of military and industrial poisoning of land and water, Paglen exposes the poisonous traces of the torture and rendition trail.

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

4

Paglen is variously described as an artist, an experimental geographer, and an amateur theologian, and his academic training is typical of the blurred boundaries that are now identified as a hallmark of new media contemporary art.8 His personal history as the child of a military doctor with an early life spent on service bases in West Germany brings additional weight and complexity to his analyses. As an interdisciplinary researcher questioning the limits of democracy, secrecy, visibility and the knowable, he reveals not Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘known unknown’ Black Swans, invoked by the Secretary of Defense to account for the lack of evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, but rather Slavoj Žižek’s ‘unknown unknowns’; the ‘disavowed beliefs, suppositions and obscene practices we pretend not to know about, even though they form the background of our public values’.9 In his project The Other Night Sky, Paglen tracks and photographs classified American satellites, space objects and debris. Combining information from a variety of amateur sources, he uses long exposure images to reveal the traces of our current militarised network in iconic western landscapes made famous by Gilded Age photographers Eadweard Muybridge, George Fiske, and Timothy O’Sullivan. This is one of Paglen’s most deeply resonant works, less a political crusade and more a long-term reflection on the nature of photography as a tool of imperialism; a conceptual legerdemain that comments on the ideologies concealed in the original works. 10 The work is exquisitely cartographic, mapping the space between what the impressionistic images of shimmering light disclose as military information and what they insinuate to be part of an aesthetic tradition of the sublime. Even as Paglen reveals, his revelations fail, as the elusiveness of the sublime flirts with the limits of ontology. With aesthetics as his tool for demarcating what can or cannot be perceived (thus creating reality), Paglen’s work is a tactical elision of fact and fiction.11

Truth, witnessing, testimony – all these concepts are invoked in Paglen’s practice. He wants to reveal the hidden geographies of military secrets, not only in the present, but also in the nineteenth century. He operates in the territory of the open secret, where invisibility is visible and manifests itself as an aesthetic phenomenon less concerned with revelation than with declaring the concerns of those who wish to conceal (rather like an institutionally-critiquing confessional).12 Underpinning all of his work is a reliance on the weight of truth in photography even in the post-photographic era. His status as an academic geographer is an important part of this: it brings a resonance to his art practice, a weight and confidence in his word, and reveals a relation to photographic evidence that might be seen to pose a challenge to Jacques Rancière’s ideas about the modern fictionalisation impulse.13 For a viewer, Paglen’s visual work takes significant effort to unpick. The icy, mechanical eye of his long-exposures demands the support of interpretive text. The viewer can perhaps pick out some extra-bright track-lines, a speck of light on a dark ground, and some traces that seem to be flowing against the stream, but without the written contextual detail, we are unable to conjure up a viable explanation for these anomalies. His hazy, heat-drenched Limit Telephotography requires details to extract the fullest understanding: my experience of the Open Hanger at Cactus Flats is given depth by knowing that this is part of Area 51, and it is also useful to have confirmation that we are looking at an airfield. Black Sites could easily be titled Random Sites. Paglen’s work requires that we believe in truth, but also that we are suspicious of it. We must ask ourselves, are these things what he says they are? Or is he pandering to a nostalgic longing for the conspiracy theories of twentieth-century televised

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

5

science fiction? Joanna Griffin Joanna Griffin is an elusive subject. It is hard to find images or accounts of any of her works. Her elusiveness fascinates me, as it seems connected to her own obsession with withheld information and accessibility to restricted technologies. It is clearly in her interest to operate discreetly but, paradoxically, it is very much not in her interest to be invisible within the art world. The inaccessibility of her work raises some important questions regarding what might be at stake that compels her to fly so far under the radar. The earliest traces of Joanna Griffin’s practice that I have located are works that track helicopters and submarines. Breaking The Surface, a study of both submarines and of the processes of research, was exhibited as a print and video installation in 2005 at Plymouth Arts Centre, and continues to have a presence in the form of a simple Flash-based website and an extended illustrated essay.14 Given Griffin’s emphasis on the experience of looking for information, the narrative of her research is largely hidden in this work. Curator Claire Doherty, reviewing the exhibition, detailed what some of the works actually were beyond their titles, and described Griffin’s practice as working with the substance of surveillance in a way that resists creating a theatre of spectacular narrative.15 Griffin herself wrote an elegant article for Cultural Politics journal, which evinces a narrative for her research, but gives no further details of the artworks (objects, processes) that she made.16 Griffin’s investigation into submarines was inspired when a Sea King helicopter flew low over her as she walked alone in the English countryside. She was more excited than frightened by the experience, which turned out to have a perfectly reasonable explanation, but the idea of the damselfly within the technology had drawn out an echo (surely, a sonar echo) with the idea and image of the sea beast within the submarine.17 Her methodology allowed her to make direct testimony to the supposedly secret submarine departures and arrivals.18 She made site visits to military bases at Devonport in Plymouth and Clyde at Faslane, to the British Library and the Imperial War Museum, to Loch Striven and Holy Loch, and she also visited an unidentified peace camp. She spoke to submariners, took a guided tour of a Hunter Killer model at Devonport, and obtained permission from the Ministry of Defence to film submarines at Faslane. Griffin is attracted to transgression, which she perceives as a misunderstood but necessary path to new thinking.19 She casts herself in the role of the trickster who negotiates the unstable edifice of postmodernism, as her subject matter moves from under the seas to above the atmosphere. She argues that she is pretending to make art to find out more about the operation of the state.20 This assertion sets up a complex set of relations and it is important to be aware of the ‘hall of mirrors’ effect that Griffin deploys as, despite her bitter opposition to militarism, she paradoxically uses militarised techniques to conduct her enquiry. Griffin manipulates the desire for an immutable, static position that can be dissected, analysed and defended, preferring to make everything she touches unstable, preventing a position from being established, constantly fragmenting and reforming. Griffin’s concerns about the accessibility of satellite technology are symptomatic of her wider interest in access to information about technologies used for military purposes. She contrasts the withholding of these technologies with the ease of access to the internet. On reflection, Griffin’s championing of

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

6

an internet that ‘wholeheartedly become[s] a civilian technology, a medium for democracy’ seems a discordant response when considered after the exposure of PRISM, the US clandestine mass electronic surveillance data mining program operated by the National Security Agency since 2007.21 Griffin’s reference to the utopian aims of the internet pioneers forces us to confront how (cyber) space has been colonised and haunted by data collection (whether by commercial or intelligence community operations). Griffin makes the point that the detachment inscribed into satellite technology is not purely connected to constraints of access to technology, but to the dominant concept of the aerial view. The new connections made to space profoundly alter the assured perspective that we have been accustomed to since the Renaissance, a perspective that places the ‘vanishing point’ on the horizon, and not at the centre of the earth (as it appears from the air).

And yet. There is a sense of distance about satellites that is not connected to their orbits.22

A Connection To A Remote Place operates as the theoretical underpinning of Griffin’s 2007-9 work Satellite Stories. The title has been applied to both workshops and performances, and it seems that Griffin adapted the material content according to the context. She has acknowledged that some space organisations do not want to work with artists, preferring to involve them solely in designing spacesuits. She consequently developed her strategy of working in ‘radical’ education projects and workshops as a compromise method of ‘deep cover’. In Satellite Stories, Griffin mixes quotations from literary and philosophical texts by Martin Heidegger, Jules Verne and Maurice Blanchot with live data from the internet, in order to make a satellite reveal its own narrative to an audience. In the piece, Griffin ranges through translating the position of celestial bodies, to images and poetics, to create a fascinating symbiosis of objective facts and subjective musings on the colonising of space and the neglected semantics of satellite architecture. In its internet iteration, the work touches on the issue of censorship as it presents a collection of various data from philosophical texts, to manifestations of the electro-magnetic interference of a storm as an image, to the audience/participants. Art/science specialist producer Nicola Triscott described Griffin’s Satellite Stories in unusually romantic and affective terms, emphasising its ‘radical departure from the usual’, and focusing on the spell cast by Griffin’s deployment of highly seductive aesthetics, all twilight and enchantment.23 Triscott follows Griffin’s lead in concentrating on the relationships between humans and their stories and experiences of space objects, rather than on the space technology itself. I suggest that her emphasis on the (almost) haptic is connected with her own bodily experiences as a sky-diver. The softness of these images is radical when considered in relation to the Kittler-inspired ‘non-human turn’ inherent in much contemporary thought in the humanities-led study of technology. 24 The ‘non-human turn’ is a way of describing the ascendancy of actor-network theory (the Latourian politics of things); and the deployment of Deleuzian-DeLandian assemblage theory and systems theory (amongst others) in humanities research during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.25 This is why and where Griffin’s reading against the grain is most evident. The images are so explicitly human, tangible, and delicate, so much the opposite of this prevailing fashion, as Griffin focuses on reminding us that technology does, in fact, have humanity in its foundations.

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

7

Suzanne Triester Suzanne Triester was born in London in the late 1950s and studied there before moving to Australia, New York and Berlin. Triester’s earliest works gained her recognition as a painter, but she moved into creating digital works in the early 1990s, and is now considered a pioneer in the field. In 1995, she developed Time Travelling With Rosalind Brodsky, in which her avatar, the delusional Rosalind Brodsky who believes herself to be working at the (wholly fictional) Institute of Militronics and Advanced Time Interventionality (IMATI), is able to investigate the traumatic history of the twentieth century by travelling to its pivotal moments.26 Using Brodsky’s adventures as a tool, Treister was at liberty to play with imagery from science fiction and religious sources, and to use autobiographical material to make sense of history, politics and war. One of Brodsky’s key acts was the attempt to rescue Treister’s grandparents who were killed in the Holocaust. The manifestation of the Brodsky projects is too various to discuss in depth here, but in addition to artefacts that include costume, drawings, and objects, there are videos of apparent ‘sightings’, the recordings of a rock band, accounts of her psychoanalyses with leading analysts, evidence of her lecturing on IMATI at the Guggenheim, bus-trips, an online estate agency, and other performances in public and gallery spaces. At first glance, the military setting for these works is not explicit but is referenced humorously in terms of IMATI; an unwary viewer could easily miss the obvious referent. The entire structure, of course, is built upon a military edifice, an artistic mirror of Virilio’s society.27 Virilio developed the concept of the ‘war model’ of modern society (borrowing freely from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s ‘Nomadology’) and states throughout his work that military projects drive history and the development of society. He argues that the military foundation of society is so embedded as to be invisible. Some of the Brodsky projects engage more openly with this than others (for example HEXEN 2039), but in many, the presence of the military as foundational is but a whisper. Treister’s work straddles disciplines, discourses and cultural hierarchies in its attempt to understand the trajectory of post-war history and the rise of the military-industrial complex. She deals with notions of identity, power and the imaginary (or hallucinatory) by revealing aspects of the hidden, opening up to marginal and occult knowledge, in order to speak from outside the history of the victors.28 She uses the tools of traditional surveillance, including detailed research, compilations of systematically cross-referenced information, reports, photographs and videos, alongside tools from hypothetical projects, and psychic and occult research programmes, to take an oddly aerial (dare I say, dromoscopic) view of modern intellectual and scientific history. NATO (2004-8) comprises over two hundred watercolours illustrating the NATO codification system, a taxonomy that classifies everything in the world numerically, for the purposes of military procurement. It is a work that relates strongly to Manuel de Landa’s concept of the logistical (in which the planning for operations must exist before the apparatus of the operation exists), and to the interpretative regime of tracking that can be modelled onto this level of his structure, paralleling the contemporary civilian manufacturing economy which ‘receives its catalytic stimulus from the original defense-related efforts of the State to create the group of strategic industries’.29 Military and civilian commercial classification networks meet here once again, enmeshed with Treister’s personal history. Treister’s father, a Polish exile, ran a defence spare-parts business, and it was while helping him build a website for his products

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

8

that she first encountered the NATO system. She identified it as a code that would seem ordinary to its users, but delusional or alienating to outsiders. Both the military coding and the NATO drawings bear the marks of the obsessional mapping and drawing so frequently associated with ‘outsider art’ – a tactic that Treister deploys repeatedly throughout her works. Treister offers up her work in a deadpan style, leaving a viewer unclear as to the level of irony in the interwoven pieces. A close perusal of the NATO watercolours, however, establishes that some very unusual objects are being classified: Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant is followed by a copy of Penthouse, the Russian crown jewels by a classical Greek altar used by the Nazis. The viewer is left to wonder exactly what sort of operations NATO might be planning, and under what category s/he might be absorbed into this endless enumeration. It is an effective strategy for destabilising the foundations of knowledge. MTB (2009), a five metre-long wall-drawing, was originally installed at Alma Enterprises in London, in the latter part of 2009. It consisted of designs for a military training base of the future, and was in many ways a futurological work, weaving together a web of histories and projections to suggest hypothetical scenarios for military training. Through MTB, Triester draws our attention to the special status of military bases as not only ‘extra-legal jurisdictions not subject to civil law’, but as potentially sovereign sites in separate territories (and consequently highly contentious) and as repositories of withheld knowledge.30 This has a clear link to the work of Joanna Griffin, especially her research into submarines in Breaking The Surface. Griffin alludes throughout her writing on the project to the double-identity of these types of base, and questions how and why one nation can be permitted to station weaponry within another. A great strength of Treister’s work, however, is that she never takes up a specific political position, maintaining a conscious ambivalence while not shying from highly politicised issues:

In terms of the military material and focus, it’s not really about ambivalence but more about ideas of complicity, since we are all complicit […] I developed a love-hate relationship with things associated with the military, which is different to ambivalence […] I certainly never wanted to make didactic, political work that’s against war per se, it’s unrealistic.31

These subtle attentions to a legal frame allude to the logistical structure of a work that might seem initially to be a play of materials. Treister does not hold back from the fantastical, invoking though her drawings of varied structures a vast and vivid potential playground. At the core of the work is the concept of the sandbox exercise, now most likely to be realised as a physical training base for operations (such as Fort Irwin, in California, often called ‘Fake Iraq’), or as a ‘serious’ video game such as Virtual Battle Space 2 or DARWARS Game After Ambush.32 Treister encourages us to conjure up exercises that might take place in real and fantastical training facilities that include replications of Afghanistan, an art school (based on the Woodland Bunker at the former RAF Bentwaters in Suffolk), a cathedral of erotic misery, Dallas Arts District, East Berlin circa 1970, the Israeli West-Bank barrier, Manhattan, an occupied zone and the ruins of the palace of the Queen of Sheba. We understand (with a catch of terror in our hearts) that the MTB could in fact be anywhere, in any location where we think we know the rules and the status of law. We could be in it. We could be

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

9

not subject to civil law, or subject to laws with which we are culturally unfamiliar. We could be being experimented on right this minute. In HEXEN 2039, Treister employs old technologies to think about new ones, using diagrams to chart a frenzied web of connections that reveal links between US rocket research in World War II, the disconcerting reappearances of Nazi technicians, the mysterious dark arts of Aleister Crowley and his ilk, psy-ops (the military’s favourite abbreviation for psychological operations), science fiction, and the Kabbalah. By doing this, she enables us to glimpse recent history as if from a great distance. But occult ritual is not just the subject matter of the research, it is also its method. Many of the drawings are ‘remote drawings’ of places, people and situations that the artist has not seen. Others are garnered through the process of scrying, a method of divination that requires a reflective, translucent or luminescent substance to psychically ‘see’ things. In the case of HEXEN 2039, this substance was the crystal globe of John Dee, Welsh scholar, polymath, advisor to Elizabeth 1, and widely considered one of the most learned men of his age. According to Treister’s statement about the project, the Dee Crystal was originally used in the sixteenth century to ‘foretell and provide political and military intelligence’ and is an exemplar of the military-occult complex at work.33 HEXEN 2.0 was shown throughout 2012 in London, Dortmund, Vienna, Leipzig, Berlin, Paris and New York in the form of alchemical diagrams, a Tarot deck, photo-text works, pencil drawings, a video and a website. This work takes up some of Treister’s favoured themes: the histories of scientific research behind government programmes; parallel histories of counter-cultures; the development of cybernetics; intelligence gathering; the framework of post-World War II military imperatives; and diverse philosophical, literary and political responses to advances in technology. These concerns align her practice with the theoretical works of media archaeologists and philosophers holding a range of differing but overlapping theories about advances in technology. HEXEN 2.0 operates as a space where the individual tools of the work (for example, the Tarot cards) can be used to envision (or predict) possible alternative futures. In his essay ‘The Secret Life of Control’, Danish art historian Lars Bang Larsen interprets the work as ‘not a quick-fix attempt at re-enchanting the world, but […] a structuring device that mirrors and performs procedures of mass intelligence gathering in the service of a new epistemology. One can perhaps compare it with a Turing Machine: a virtual system capable of simulating the behaviour of any other machine or apparatus of knowledge, including itself.’34 It is a perfect summation of Treister’s practice.

Other artists Of course, Paglen, Griffin and Triester are not the only (or necessarily the most important) artists working with this ‘underlying horror’. In this final section, I offer a brief and highly subjective introduction to a number of artists or projects working specifically with nuclear, biological and chemical materials, themes and artifacts.35 The most evident response to Carson in my own practice was my recent exhibition Requisite in 2012, which played with the interstices between optical objects and weapons. It referenced both the past and the future of objects by generating projections alluding to the Strategic Defense Initiative, and by using food products to suggest biological experiments, demonstrated by Fylingdales in Winter and Rocket (The Object and Its Shadow). Rocket in

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

10

particular, with its obvious phallic joke, simultaneously invokes desire and contamination. Linda Lear, Carson’s biographer, points out that Carson was ‘deeply influenced by the nuclear tensions of the Cold War period in which she worked’, and the web of secrecy that surrounded the Bikini Atoll tests.36 One of the most striking messages in Silent Spring is that of time, in particular the time taken by elements to degrade:

One of the most important things to remember about insecticides in soil is their long persistence, measured not in months but in years. Aldrin has been recovered after four years, both as traces and more abundantly as converted to dieldrin. Enough toxaphene remains in sandy soil ten years after its application to kill termites. Benzene hexachloride persists at least eleven years; heptachlor or a more toxic derived chemical, at least nine. Chlordane has been recovered twelve years after its application in the amount of 15 per cent of the original quantity.37

All of these time frames pale into insignificance when discussing the time frames involved in the matter of radioactive waste, where the years are counted in their millions and become unimaginable. It is hardly surprising that many artists are haunted by these toxic legacies that have been exposed by public-facing scientists. James Acord (1944-2011) was the only private individual in the world licensed to own and handle radioactive materials. Certain that fine art sculpture could ‘make a contribution to society’s understanding of matters nuclear’, he spent much of his post-1986 career battling to convert highly radioactive nuclear waste into inert materials for use in sculpture and art events.38 Acord’s work exposed the secrecy and security with which society cloaks the nuclear industry, as he probed the history of nuclear engineering in projects that include powering a table-top nuclear reactor with uranium mined from Fiestaware and found in thrift stores. In 1999, Acord created his famous ‘round table’ around which he brought together scientists, engineers and environment agencies to discuss the possibilities and dangers of working with nuclear materials, an event which was re-created in 2013 by curator, artist and activist Ele Carpenter for her current Nuclear Culture research project.39 Joy Garnett’s The Bomb Project is a comprehensive (to approximately 2005) online compendium of nuclear–related links and images, intended as a resource for artists, but also useful to a wider range of researchers. 40 It comprises nuclear image archives, historical documents, treaties, labs, and activist organisations, and makes accessible the declassified files and documentation of the nuclear industry itself. The database – itself derived from military experimentation – demonstrates the kind of organisation and decentralisation of information that is possible when using (what were then) the new technologies. British artist Louise K. Wilson is interested in how the ‘technologies of the audible create new ways of engaging with the lost traces of institutional spaces’.41 These spaces have included the Nurrungar listening station near Woomera in Australia; the former military test site at Orford Ness (Record of Fear, 2005) and RAF Spadeadam. Her film work Spadeadam focuses on her observation of an English Heritage archaeological survey of the Blue Streak rocket launch site at Spadeadam in Cumbria. In this work she used noise recorded on site by sound artists :zoviet*france: together with electronically created sounds that emulate the low frequency rumble of the site when still

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

11

active. It is a menacing reminder of things that have passed but still remain. BioArt is a broad term for practices which work with live tissues, bacteria, living organisms and life processes in laboratories, galleries, studios and domestic settings, much of which reflects Carson’s concerns about ownership of processes and responsibilities. Critical Art Ensemble (a tactical collective) uses any media necessary to engage with a specific socio-political context. They use easy-to-access lab equipment and ordinary household supplies to render complex science and technology accessible to the non-specialist public. Works such as GenTerra and Molecular Invasion aim to involve the public in the development of an informed and critical debate around biotechnologies, and to expose the misuse of biotechnology by large corporations. Carson might have found them useful allies, alongside Beatriz de Costa and Kavita Phillips who argue in their book Tactical Biopolitics that the political challenges at the intersection of life, science and art are best addressed through artistic intervention, critical theorising and reflective practices. 42 Finally, it is impossible to reflect on Carson’s work without referring to the many artists who explicitly position their work in an environmentalist context. One such is the Canadian artist Kelly Richardson. Richardson situates her work between the apocalyptic sublime and straight science fiction, evoking environmental atrocities with her painstaking application of digital effects to documentary footage. Leviathan (2011) seethes with chemical menace, as Caddo Lake at Uncertain, Texas glows and pulsates in acidic yellow.43 Her recent work Mariner 9 (2012) is a forty-three foot wide rendering of Martian terrain (with technical data supplied by NASA) that demands our reflection on questions of what we might yet become, and the damage we might do in the process: a visual essay on the ruin that our quest for chemicals is creating. All of these artists reflect not only on the fall-out of the twentieth century and its impact in the early twenty-first century, but also on some of the key themes of Silent Spring: the ownership of technologies and materials, and the responsibility to successive generations; and the making visible of the consequences of secrecy and evasion of accountability. Carson called for the world to notice: it seems that contemporary artists are paying attention.

Oxford Brookes University Notes 1 Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (1962; London: Penguin, 2000), p. 24. 2 Carson, Silent Spring, p. 31. 3 Peter Sloterdijk, Terror From The Air, trans. by Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran (Los

Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009), p. 10. 4 Paul Virilio, Politics of the Very Worst (New York: Semiotext(e), 1999), p. 89. 5 Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception (London: Verso, 1989), p.

22. 6 Carson, Silent Spring, p. 29. 7 Carson, Silent Spring, p. 121. 8 Christopher Knight, ‘Trevor Paglen’s Seeing In The Dark’, Los Angeles Times, 10

September 2010 http://www.altmansiegel.com/tpaglen/tpaglenpress5.pdf [accessed 4 November 2013].

9 Attributed to former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, February 12, 2002, Department of Defense press transcript: http://www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=2636 [accessed 1 August 2012]. Žižek links this back to Lacan’s description of the Freudian unconscious: ‘the knowledge which doesn’t know itself’: http://www.lacan.com/zizekrumsfeld.htm.

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

12

Originally published on the In These Times weblog at http://www.inthesetimes.com/ [accessed 4 November 2013].

10 Chris Smith, ‘Strange Renderings: the secret Geographies of Trevor Paglen’ (San Francisco: Altman Siegal Gallery, undated); printed ephemera.

11 Pamela M. Lee, ‘Open Secret: The Work of Art between Disclosure and Redaction’, Artforum, May 2011, pp. 220-229.

12 Lee, ‘Open Secret’. 13 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. by Gabriel Rockhill (London:

Continuum, 2004). 14 Joanna Griffin, ‘Breaking The Surface’ (2005), exhibition at Plymouth Arts Centre,

Plymouth. http://breakingthesurface.net/ [accessed 1 July 2012]. 15 Clare Doherty, ‘Breaking The Surface’ (Plymouth: Plymouth Arts Centre, 2005). Works

by Joanna Griffin comprising part of the Breaking The Surface exhibition, (note that this may not be an exhaustive list): MD902, a video work with helicopter; An Earlier Mission, Super8 and digital video; Field Work, an installation of varied materials; Chrysalidding, digital print; S173, video installation; Moby Dick; Airshow, bookwork.

16 Joanna Griffin, ‘Breaking The Surface’, Cultural Politics, 1.2 (2005), pp. 233-242. 17 Not only is there a large type of forest-dwelling damselfly called a ‘Helicopter

damselfly’, there is also an Italian armaments company that produces a helicopter-like UAV (drone) called Damselfly.

18 Griffin states that their timetables are published in the Western Morning News. 19 Joanna Griffin, ‘Moon Vehicle: Reflections from an artist-led Children’s Workshop on

the Chandrayaan-1 Spacecraft’s Mission to the Moon’, LEONARDO, 45.3 (2012), pp. 219-224.

20 Joanna Griffin, ‘Moon Vehicle’. 21 Joanna Griffin, ‘A Connection To A Remote Place’ (unpublished master’s thesis,

University of Westminster, 2003). 22 Joanna Griffin, ‘A Connection To A Remote Place’. 23 Nicola Triscott, ‘Satellite Stories and Human Futures,’ 3 November 2008

http://www.artscatalyst.org/network/blogarticle/satellite_stories_human_futures/3/11/08 [accessed 1 August 2012].

24 See Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wurtz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), where Kittler ‘effectively divests humanity of its subjectivity, naming it as a mere function of media by identifying the autonomy of technology’ (Isabella Streffen, ‘I Spy With My Military Eye: strategies of military vision in fine art practice’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Newcastle University, 2012), p. 45).

25 Bruno Latour, Reassembling The Social: An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

26 Suzanne Treister, The Brodsky projects, 1995-2010, varied media. 27 Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2006), p. 63. Quoted in

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 386.

28 Attributed to Winston Churchill, but of unknown origin. 29 Manuel De Landa, War In The Age of Intelligent Machines (New York: Zone, 1991), p.

111. 30 Suzanne Treister website:

http://ensemble.va.com.au/Treister/MilitaryTrainingBases/MTB.html [accessed 1 August 2012].

31 Suzanne Treister interviewed by Roger Luckhurst, December 2009 http://ensemble.va.com.au/Treister/info/Interviews/Treister_Luckhurst.html [accessed 4 November 2013].

32 Simulation games developed and used by the military for battle training. 33 Suzanne Treister website

http://ensemble.va.com.au/tableau/suzy/TT_ResearchProjects/Hexen2039/Diagrams&Drawings/remotedraw.html [accessed 1 August 2012].

34 Suzanne Treister, Hexen 2.0 (London: Black Dog, 2012). 35 Also see work by Jane and Louise Wilson, Stephen Felmingham, Angus Bolton, David

Chapman, and Gair Dunlop. 36 Carson, Silent Spring, p. 260. 37 Carson, Silent Spring, p. 65. 38 Chris Arnot, ‘Sculpting with Nukes’, Guardian, 26 October 1999

http://www.theguardian.com/culture/1999/oct/26/artsfeatures [accessed 15 February 2013].

Dandelion: postgraduate art journal and research network Isabella Streffen Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter 2013) The Underlying Horror of the English Countryside

13

39 Ele Carpenter, Nuclear Culture http://nuclear.artscatalyst.org/ [accessed 1 May 2013] 40 Joy Garnett, The Bomb Project

http://www.firstpulseprojects.net/bombproject/Index.html [accessed 4 November 2013].

41 Artist’s website http://www.lkwilson.org/index.php?m=welcome&sub=statement [accessed 4 November 2013].

42 Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Phillips (eds.), Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism and Technoscience (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2010). Also see work by Stelarc, Anna Dumitriu, and Brian Degger.

43 Site of the first drilling for oil underwater in 1912.

Works Cited Carson, Rachel, Silent Spring (1962; London: Penguin, 2000) Deleuze, Gilles, & Guattari, Félix, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. by Brian Massumi

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987) Doherty, Clare, ‘Breaking The Surface’ (Plymouth: Plymouth Arts Centre, 2005) Griffin, Joanna, ‘Moon Vehicle: Reflections from an Artist-Led Children’s

Workshop on the Chandrayaan-1 Spacecraft’s Mission to the Moon’, Leonardo, 45.3 (2012), pp. 219-224.

‘Breaking The Surface’, Cultural Politics, 1.2 (2005), pp. 233-242. ‘A Connection To A Remote Place’ (unpublished master’s thesis,

University of Westminster, 2003) Ishiguro, Kazuo, The Remains Of The Day (London: Faber & Faber, 1989) Knight, Christopher, ‘Trevor Paglen’s Seeing In The Dark’, Los Angeles Times, 10

September 2010 http://www.altmansiegel.com/tpaglen/tpaglenpress5.pdf [accessed 4 November 2013]

De Landa, Manuel, War In The Age of Intelligent Machines (New York: Zone, 1991)

Latour, Bruno, Reassembling The Social: an introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Lee, Pamela M., ‘Open Secret: The Work of Art between Disclosure and Redaction’, Artforum, May 2011, pp. 220-229

Rancière, Jacques, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. by Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004)

Sloterdijk, Peter, Terror From The Air, trans. by Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009)

Smith, Chris, ‘Strange Renderings: the Secret Geographies of Trevor Paglen’ (San Francisco: Altman Siegal Gallery [n.d]); printed ephemera

Treister, Suzanne, Hexen 2.0 (London: Black Dog, 2012) Virilio, Paul, Politics of the Very Worst (New York: Semiotext(e), 1999) Speed and Politics, trans. by Mark Polizotti (Cambridge MA: MIT Press,

2006) War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception (London: Verso, 1989) Žižek, Slavoj, ‘What Rumsfeld doesn’t know that he knows about Abu Ghraib’,

In These Times, 21 May 2004 http://www.lacan.com/zizekrumsfeld.htm [accessed 1 August 2012]