Genetics of Obesity: Five Fundamental Problems With the Famine Hypothesis

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal

Transcript of The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal

jason king

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal

On 18 August 1847, during their honeymoon, Herman Melville’s new bride Elizabeth Shaw recorded that they had visited ‘[t]he Convents, Cathedral and Parliament House at Montreal’.1 In their immediate vicinity were the fever-stricken Grey Nunnery and the Hôtel Dieu convent, the female religious congregations which had been caring for Irish Famine emigrants in the city’s fever sheds for the past two months. Melville did not write about any of this in his fiction, but a few days later he accompanied Irish migrants on his return journey to the United States in a canal boat when, according to Shaw, he ‘preferred to remain on deck all night to being in this crowd’ – an experience which furnished the aloof self-image for his protagonist in Redburn.2 During their brief honeymoon, the Melvilles left more of a trace of their presence in Montreal than the tens of thousands of Famine emigrants who convalesced or perished in the city’s fever sheds in the summer of 1847. Although it is claimed that the incidence of ‘fever, suffering and death’ at the Grosse Île quarantine station downriver was ‘unique in the Famine exodus’,3 the scale of Irish migrant mortality was similar in Montreal and much higher for its host population than elsewhere in North America. Since the Irish Famine sesquicentenary, Presidents Mary Robinson, Mary McAleese, and Michael D. Higgins have all paid

1 Qtd in Jay Leyda, The Melville Log: A Documentary Life of Herman Melville 1819–1891, i: (1951; New York: Gordian Press, 1969), 256.

2 Qtd in ibid., 258; Herman Melville, Redburn: His First Voyage (New York: Harper Brothers, 1863), 26.

3 Ciarán Ó Murchadha, The Great Famine: Ireland’s Agony 1845–1852 (London: Continuum, 2011), 151.

246 jason king

tribute to English and French Canadians for their compassionate and humanitarian response to Famine emigrants, which is also commemorated by Parks Canada at Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site.4 According to Piaras Mac Éinrí, these emigrants were beneficiaries ‘of the quite extraordinary generosity extended to them by Québecois society, French- and English-speaking, Catholic and Protestant’.5

Nevertheless, there is substantial evidence of cultural conflict, ethno-religious tension and especially anxiety about proselytization occurring in the fever sheds of Montreal in 1847. Recent research has focused in par-ticular on the politically and socially disruptive impact of the arrival of the Famine Irish in the city. Dan Horner argues that their influx aggravated conflict between the British imperial and Canadian colonial authorities as well as more localized antagonisms between the colonial governor and municipal health officials about how to contain the typhus epidemic, how to allay public concern about increasing fatalities, and where to locate the fever sheds.6 The massive inflow of Famine migrants also intensified religious rivalries in Montreal and led to accusations of proselytization of Protestant fever victims, claims Maude Charest.7 More broadly, Sherry Olson and

4 Mary Robinson, ‘Address by Uachtarán na hÉireann Mary Robinson to Joint Sitting of the Houses of the Oireachtas’ (2 February 1995). <http://www.oireach-tas.ie/viewdoc.asp?fn=/documents/addresses/2Feb1995.htm> accessed 9 October 2013; Michael D. Higgins, ‘Message from President Michael D. Higgins’ (2012). <http://www.history.ul.ie/historyoffamily/faminearchive/pdf/Preface_for_Le_Typhus_de_1847_Virtual_Archive.pdf> accessed 9 October 2013;’President Opens Toronto Famine Memorial Park’, Irish Abroad (published online 21 June 2007). <http://www.irishabroad.com/Modules/CMS/Articles/DSSPrintArticle.aspx?ArticleID=888#fulltext> accessed 9 October 2013.

5 Piaras Mac Éinrí, ‘Famine and the Irish Diaspora’, in John Crowley, William J. Smyth, and Mike Murphy, eds, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine (Cork: Cork University Press, 2012), 593.

6 Dan Horner, ‘“The Public Has a Right to be Protected from a Deadly Scourge”: Debating Quarantine, Migration, and Liberal Governance during the 1847 Typhus Outbreak in Montreal’, Journal of the Canadian Historical Association/Revue de la Société Historique du Canada 23/1 (2012), 69–70, 91.

7 Maude Charest, ‘Prosélytisme et conflits religieux lors de l’épidémie de typhus à Montréal en 1847’, Cap-aux-Diamonds: la Revue d’Histoire du Quebec 112 (2013), 8–12.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 247

Patricia Thornton have tracked the upward social mobility of Irish Catholic Famine emigrants and their descendants, whose struggle to establish their own institutions in a city defined by its English Protestant and French Catholic majorities occasioned an escalation of ethno-religious friction in the later nineteenth century: ‘In the late 1840s, when the Irish arrived in such great numbers, they encountered a situation where a social bound-ary was already firmly defined in religious terms.’8 Yet, within a generation, they had created their own Irish Catholic social infrastructure through ‘the proliferation of new institutions’ that ‘generated a model for the reception of immigrant groups that followed them’.9 Olson and Thornton question whether this ‘upward trajectory of Irish Catholics [that] was more rapid in Montreal than in most cities of the United States’ should ‘cast suspicion on the entire historiography of the Irish in North America? Or does it simply mean that Montreal was different?’10 Finally, Colin McMahon has charted the confessional and communal divisions and fraught negotiations behind the commemoration of the city’s Famine emigrants in the latter nineteenth and twentieth centuries.11 Each of these studies examines the struggles of the Famine Irish to establish their own community and institutions in nineteenth-century Montreal. They complicate rather than repudiate received wisdom about the extraordinary generosity and hospitality of the Canadian host society.

This chapter considers how the remembrance of Famine migrants in the fever sheds of Montreal – contested cultural spaces – was subli-mated from these various forms of ethno-religious, social, and political tension into a global legacy not of conflict but of accommodation. The most detailed and extensive eye-witness accounts of the influx of Famine

8 Sherry Olson and Patricia Thornton, Peopling the North American City: Montreal, 1840–1900 (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2011), 351.

9 Ibid.10 Ibid. 11 Colin McMahon, ‘Ports of Recall: Memory of the Great Irish Famine in Liverpool

and Montreal’, PhD thesis, York University, Toronto, 2010, 140–93, 246–333; see also Colin McMahon, ‘Montreal’s Ship Fever Memorial: An Irish Famine Memorial in the Making’, Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 33/1 (2007), 46–60.

248 jason king

Irish in Montreal can be found in the unpublished French annals of the religious congregations who cared for them, especially the Grey Nuns, which were digitized and translated into English for a ‘Famine Archive’ hosted by the University of Limerick. The spectacle of Irish suffering they register became a site of memory and diasporic identity formation that was mediated and transmitted from eye-witness observation to narrative recollection in a variety of print and visual media and factual and fictional genres. Whether it be in Famine annals, letters, novels, or votive images, the Irish emigrants in the fever sheds were transformed into ‘figures of memory’12 through the textual and visual mediation and reconstruction of their historical experience.

I also want to argue, however, that the female religious eye-witness accounts of their suffering were only partially reproduced, and selectively informed the cultural memory and state commemorations of the event. Because they were unpublished and written in French, the Grey Nuns’ Famine annals were generally overlooked and played little role in shap-ing subsequent historical interpretations or popular recollections of what transpired in the fever sheds. Much more influential were the published reminiscences in English that attested to the nuns’ compassion, devotion, and self-sacrifice, but eschewed the remembrance of conflict occasioned by the arrival of Famine migrants. These accounts in English were also written later in the nineteenth century when the ethno-religious, politi-cal, and social tensions that were prevalent in the 1840s had diminished.13

As James Wertsch contends, ‘what constitutes a useable past in one sociocultural setting is often quite different from what is needed in another’.14 A case in point is the work of the Irish Catholic novelist Mary Anne Sadlier, who was resident in Montreal during the summer of 1847.

12 Jan Assmann, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity’, New German Critique 65 (1995), 129.

13 Jason King, ‘L’historiographie irlando-québécoise: Conflits et conciliations entre Canadiens français et Irlandais’, tr. Simon Jolivet, Bulletin d’histoire politique du Québec 18/3 (2010), 25–9.

14 James V. Wertsch, Voices of Collective Remembering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 43–4.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 249

As Marguérite Corporaal notes, Sadlier’s novels ‘offer a mediated memory of the Great Hunger’ based on her ‘correspondence with relatives and friends, and on accounts of immigrants who had escaped from their famine-stricken homeland’,15 yet it took her over forty years to describe her own impressions of the Famine influx in Montreal.16 When she finally did so, her recollections of religious heroism screened more troubling memo-ries of the proselytization of Protestant fever victims and female sexual impropriety associated with the arrival of Famine migrants in the city. Her reminiscences of these Irish immigrants represent a form of ‘screen memory’ that ‘illustrates concretely how a kind of forgetting accompanies acts of remembrance, but this kind of forgetting is subject to recall’.17 More broadly, her remembrance of Famine migrants in the fever sheds was based as much on the elision of ethno-religious tension as on the promulgation of a distinctly Irish Catholic version of the past.

Coffin Ships and Fever Sheds

The study of Famine memory and its textual mediation into narrative recollections of migration has developed into a new area of research in its own right. In his influential study The End of Hidden Ireland, Robert

15 Marguérite Corporaal, ‘Memories of the Great Famine and Ethnic Identity in Novels by Victorian Irish Women Writers’, English Studies 90/2 (2009), 144.

16 Mary Anne Sadlier lived in Montreal from 1844 to 1860 when she wrote the following novels about the Famine Irish in the United States and their homeland: Willie Burke; Or, The Irish Orphan in America (1850), New Lights; Or, Life in Galway (1853), The Blakes and Flanagans (1855), Con O’Regan; Or, Emigrant Life in the New World (1856), and Confessions of an Apostate; Or, Leaves from a Troubled Life (1858). Unlike these texts, her more autobiographical novel Elinor Preston; Or, Scenes at Home and Abroad (1861), is set in Montreal, but it recalls the arrival of the Famine Irish only in passing.

17 Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 13. I am grateful to Lindsay Janssen for introducing me to the concept of ‘screen memory’ in this context.

250 jason king

Scally argues that the concentration of Famine emigrants from all over Ireland in the confined settings of the Liverpool Docks, the steerage of trans-Atlantic passenger vessels, and the lazarettos on Grosse Île created the social conditions for such iconic motifs of Famine memory as the ‘coffin ships’ and ‘fever sheds’ to take shape. ‘Flanked by Skibbereen and Grosse Isle at either end of the voyage, the “coffin ships” stand as the central panel of the famine triptych’, he writes.18 They were not just consecutive stages in the Famine journey but also contiguous templates in its narrative recollec-tion, sequential reminders of ‘the miserable epic of the Atlantic crossing’.19 As both a physical place and a mnemonic device, the fever sheds marked the end of the Famine voyage.

More recently, Marguérite Corporaal and Christopher Cusack have examined the textual mediation of the memory of the ‘coffin ships’ into what they suggest has become a ‘schematic narrative template’20 in a wide variety of nineteenth-century Irish and Irish-diaspora novels. They contend that one of the functions of Famine remembrance in their literary corpus is to provide a vehicle for Irish immigrant integration and ethnic identity formation in North America. ‘The coffin ships facilitate the development of microcosmic Irish “imagined communities”’, they suggest, in which ‘the cultural clashes experienced in the homeland and the pending assimilation in the New World have to be negotiated’.21 Put another way, the compres-sion of social and spatial tension in the confined setting of the coffin ship both encapsulated and precipitated a wider sense of conflict that became one of its defining features as a literary motif and site of memory.

The role of Famine remembrance in the mediation and negotiation of cultural clashes between Irish migrants and members of host societies is quite similar in the case of the fever sheds. Like the coffin ships, the fever

18 Robert Scally, The End of Hidden Ireland: Rebellion, Famine and Emigration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 218.

19 Ibid.20 Wertsch, Voices of Collective Remembering, 61.21 Marguérite Corporaal and Christopher Cusack, ‘Rites of Passage: The Coffin Ship

as a Site of Immigrants’ Identity Formation in Irish and Irish-American Fiction, 1855–85,’ Atlantic Studies 8/3 (2011), 345.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 251

sheds have also become an iconic motif of Famine memory in part because they were a contested cultural space. The social construction of the steerage resembles that of the sheds insofar as both provide a temporary setting and volatile milieu for the intermingling of migrants from different classes and ethnic and religious groups. The hold of the emigrant vessel functioned as a forum for intercultural contact between various passenger classes while at the same time exacerbating their religious and social divisions. Indeed, the coming together of migrants from vastly different backgrounds who were brought into close proximity on board often exhibited what Mikhail Bakhtin describes as carnivalesque tendencies of licensed transgression, of the temporary suspension of social norms and the levelling of hierarchical class, gender, and religious distinctions that had defined their identities prior to the voyage.22 As in the hold of the emigrant vessel, incarceration in the fever sheds brought migrants across confessional and social lines into intimate and prolonged contact that could aggravate conflict between them. These clashes were not simply localized disputes but also prefigured the later confrontations that Irish emigrants experienced when trying to define the terms of their integration into the wider host society. They pro-vide a case study of contested acculturation, a struggle for self-sufficiency in the shadow of catastrophe.

Textual and Visual Mediations of Famine Memory

There is a strong emphasis on the compassion of French-Canadian nuns and the intense bodily suffering of fever- and grief-stricken Irish Famine emi-grants in both English- and French-language textual and visual depictions

22 M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination, ed. Michael Holquist, tr. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1981), 70, 77–9.

252 jason king

of the fever sheds.23 The full stories of what transpired inside the sheds, however, can only be found in the annals of the female religious who admin-istered them. There are over three hundred pages of unpublished records of the Grey Nuns in the digital Irish ‘Famine Archive’,24 while the Sisters of Providence and the cloistered nuns of the Hôtel Dieu also kept extensive annals of their experiences in 1847.25 These cumulative records provide the most detailed descriptions of the cultural encounters that took place between the Famine Irish and their caregivers in Montreal.

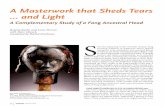

At first glance, there appears to be little difference between the visual depictions of compassionate nuns caring for Famine emigrants and the textual recollections of these events in their religious annals. The only contemporary visual image of the fever sheds was completed by Théophile Hamel in his 1848 painting Le Typhus, which records each of the three orders of nuns who ministered to the Famine Irish in turn (Figure 16). ‘We have in Montreal a large picture of the interior of the fever-sheds’, wrote Mary Anne Sadlier over forty years later, ‘showing with painful reality the rows of plague-stricken patients with the clergy and religious in attendance on them. In the far background, the good Bishop himself is seen in purple cassock ministering to the sick’.26 Sadlier describes the composition of the religious figures in the painting in terms of their consecutive arrival in the sheds. In her own words:

23 See in particular Sharon Doyle Driedger, An Irish Heart: How A Small Community Changed Canada (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2010), 41; and Maximilian Montagu Hammond, Memoir of Captain M. M. Hammond, Rifle Brigade (New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1858), 113.

24 Jason King, ‘Famine Archive’ (2012). <http://www.history.ul.ie/historyoffamily/faminearchive> accessed 9 October 2013.

25 Jason King, ‘Remembering Famine Orphans: The Transmission of Famine Memory between Ireland and Quebec’, in Christian Noack, Lindsay Janssen and Vincent Comerford, eds, Holodomor and Górta Mor: Histories, Memories and Representations of Famine in Ukraine and Ireland (London: Anthem Press, 2012), 141.

26 Mary Anne Sadlier, ‘The Plague of 1847’, Messenger of the Sacred Heart ( June 1891), 208–9.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 253

First came the Grey Nuns who gave themselves heart and soul to the fearful labors of the vast lazar-house […]. Then the Sisters of Providence […] took their places beside the coffin-like wooden beds of the fever patients in the sheds […]. When these two large communities were found to be inadequate to take care of the ever-increasing multitude of the sick, a thing came to pass which struck the whole city with admira-tion. The cloistered Hospitallers of St. Joseph [Hôtel Dieu nuns], whom the citizens of Montreal had never seen except behind the gratings of their chapel or parlor, or in their own hospital wards, petitioned the Bishop to dispense them their vows of long seclusion, that they might go to the aid of their dear sister communities in the pestilential atmosphere of the fever sheds.

The permission was freely given, and the strange sight was seen day by day in the streets of our ancient city, of the close carriage that conveyed the Sisters of the Hôtel Dieu from their quiet old-time convent to the lazar-house […]. People pointed it out to each other with solemn wonder, as the writer well remembers, and spoke with bated breath of the awful visitation that had brought the cloistered nuns from their convent into the outer world, in obedience to the call of charity.27

Sadlier was one of the most popular and prolific novelists of the nineteenth century and her works often featured Famine orphan protagonists strug-gling to maintain their faith, but her 1891 essay ‘The Plague of 1847’ provides the only irrefutable evidence that she bore witness to the Famine influx. Her recollection of the release of the Hôtel Dieu cloistered nuns actually occurred in the first week of July, 1847. This image of the uncloistered nun with the Irish orphan became deeply imprinted in popular memory.28

The recurrent motif, however, in Théophile Hamel’s Le Typhus and the annals is that of Irish infants being removed from the breast of their stricken mothers by each of these three orders of nuns. Because the painting is installed in the ceiling of the vestibule of Bonsecours Church, which is not particularly well lit, observers need to crane their necks and can inad-vertently miss background details. One of the more startling images in the middle background of Le Typhus is that of the grieving husband cradling his dead wife (Figure 17). As described in the ‘Grey Nuns Famine Annal’:

27 Ibid., 207–8.28 Jason King, ‘Remembering and Forgetting the Famine Irish in Quebec: Genuine and

False Memoirs, Communal Memory and Migration’, Irish Review 44 (2012), 26–31.

254 jason king

One day came a man from GROSSE ILE, where he had remained upon his arrival, being too sick to be transported to Montreal, where his wife, who was in good health, was sent with everyone else who had yet to be infected with the contagion. This poor man was looking everywhere for his wife without being able to find her; […] he enters the SHEDS and looks on every cot to no avail. Finally, he goes out to pursue his search; while crossing the courtyard, he sees a great number of dead bodies. He comes nearer to examine them more closely. What does he see? […] The inanimate body of his wife whom he was looking for all this time. He takes her in his arms, seeming to doubt that she is in fact dead; he wants to bring her back to life, talks to her, calls her by her name, kisses her tenderly; but for all these demonstra-tions, the only answer he receives is death’s silence. Once he is convinced that she no longer exists, he abandons himself to his pain, the air is filled with his cries and sobs, the spectacle was most heart wrenching. Scenes of this nature occur several times a day.29

The same spectacle is recorded more fleetingly in the Montreal Transcript: ‘Many cases of extreme distress came to our knowledge during a recent visit to the sheds. We met with one poor heart-broken man, whose children were in the hospital at Grosse Isle, and whose wife was uttering her last sighs in our shed’.30

The graphic display of the removal of children from the corpses of their parents in the painting is also corroborated in the Grey Nuns’ annal ‘The Typhus of 1847’. It recounts how one ‘morning Sister Montgolfier was completing her usual visits when she noticed that young children had entered the enclosure where their dead father lay; these poor little ones were calling him caressing him and playing amongst themselves’ until she removed them from his cadaver.31 It is only through cross-referencing between textual, visual and contemporary press accounts of such iconic images that they can be traced to their historical moment of origin.

29 ‘Grey Nuns Famine Annal’, Ancien Journal 1 (1847), tr. Jean-François Bernard (2012), 7. <http://www.history.ul.ie/historyoffamily/faminearchive/pdf/Grey_Nuns_Famine_Annal_Ancien_Journal_Volume_I_1847.pdf> accessed 9 October 2013.

30 Montreal Transcript (19 June 1847).31 ‘The Typhus of 1847’, Ancien Journal 2 (1847), tr. Philip O’Gorman (2012), 27. <http://

www.history.ul.ie/historyoffamily/faminearchive/pdf/The_Typhus_of_1847.pdf> accessed 9 October 2013.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 255

Anxiety of Proselytization

Implicit within these images of Irish suffering and female religious com-passion and devotion is also the anxiety of proselytization. While there is limited evidence of actual religious conversions taking place in the fever sheds, the fear of them was intense. The Grey Nuns’ ‘Typhus of 1847’ annal recounts that Sister Collins, ‘in seeing Protestant ministers circulating in the shelters […] made a good guard against those that wished to indoctri-nate’. Likewise, Father Richards, the first English-language priest for Irish Catholics in Montreal, who ultimately succumbed to typhus, is recorded as taking charge of Famine orphans and insisting that ‘a shed specifically [be] designated for children […] in the fear that the Protestants would seize these poor little ones’. On 16 July 1847, Sister Collins is also recalled as ‘having absented herself for a few moments from the bedside of her patients, a Protestant minister exerted his propaganda and by consequence argued for the alleged reform. But the Sister entered suddenly, her patients screaming’. Later, in September 1847, after the Grey Nuns had recuperated and returned to the fever sheds, they became embroiled in controversy when they converted shed number eight into a Catholic chapel so that their patients could ‘hear the voice of the sisters accompanied by their little orphans singing […] their national hymn of Saint Patrick; […] Since then, mass was regularly celebrated daily’, records the annal.32 The reclamation of public space for this Catholic chapel to accommodate the Famine migrants foreshadows later Irish endeavours to build their own social institutions. In fact, the chapel’s establishment became a catalyst for the intensification of ethno-religious rivalry in the sheds in the autumn of 1847.

Although the struggle to consecrate shed number eight occurred less than six months after the opening of Montreal’s St Patrick’s Church, now Basilica, on 17 March 1847, this much smaller, ramshackle facility epito-mized the development of the city’s Famine Irish social infrastructure. The fever sheds themselves had been erected, along with the quarantine station

32 ‘The Typhus of 1847’, 26, 28, 41, 78.

256 jason king

at Grosse Île, fifteen years earlier when the first wave of disease-stricken Irish emigrants had arrived during the cholera epidemic of 1832. As Bettina Bradbury notes, ‘the epidemic stimulated the creation of […] female-led charitable associations’ and ‘enduring new institutions to shelter both widows and children’.33 It was not until the influx of Famine emigrants in 1847, however, that the city’s Irish Catholic community was mobilized to create its own network of social institutions for their support.

The endeavours of Father Patrick Dowd, in particular, to gather desti-tute children and widows from the fever sheds and makeshift shelters under a single roof provided the impetus for the development of the city’s Irish Catholic social facilities. In the Grey Nuns’ annal entitled ‘Foundation of St Patrick’s Asylum’, he is recalled as ‘a zealous young priest who was willing to work’ tirelessly with the Grey Nuns as the ‘chaplain for the poor Irish’.34 One of the most poignant sections of the annal recounts how Father Dowd was cast in a King Solomon-like role to reunite a Famine orphan with her mother. It records how an Irish widow, Suzanne Brown, became separated from her youngest daughter, Rose, in Montreal’s fever sheds after she had nearly succumbed to typhus, only to recover from her illness having lost contact with her child. While convalescing under the care of the Grey Nuns, she helped educate the orphans they had taken in. According to the annal,

When she found herself surrounded by the orphans who absorbed her teachings like thirsty earth absorbs the dew, she thought of her little Rose: ‘If I had her here with me[’], she said, [‘]I would teach her with all the others.’ With this weighing on her mind, one March evening, she attended a Lenten prayer service or a benediction of the Holy Sacrament in St Patrick’s church. In the silence of the ceremony, she was disturbed from her contemplation by the sound of a marble rolling on the floor which came to rest in the folds of her clothes. She had barely raised her eyes when she saw a little girl aged three or four running to collect it. ‘Is this not my little Rose’, she said

33 Bettina Bradbury, Wife to Widow: Lives, Laws, and Politics in Nineteenth Century Montreal (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2011), 185, 295.

34 ‘Foundation of St Patrick’s Orphan Asylum’ (1847), tr. Philip O’Gorman (2012). <http://www.history.ul.ie/historyoffamily/faminearchive/pdf/Grey_Nuns_Famine_Annal_Foundation_of_St_Patricks_Orphan_Asylum.pdf>, accessed 24 April 2014.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 257

trembling with emotion. Indeed, it was this child who she mourned and thought she had lost forever, now returned to her at this moment by our Lord, and by instinct, she reached out. However, her adoptive mother who had missed nothing of what happened, intervened and protested. Before the ceremony had even finished both women went to the sacristy to submit the case to Father Dowd. He did not delay in resolving the issue, and that very evening, Madame Brown triumphed, coming back to the refuge with little Rose.35

In reuniting families afflicted by famine and creating shelters for orphans and widows, Father Dowd placed himself at the heart of Irish communal life in Montreal. More specifically, he founded St Patrick’s Temperance Society (1850) and St Patrick’s Orphans Asylum (1851), expelled Protestants from St Patrick’s Society (1856) and created St Bridget’s Home for the old and infirm (1865). ‘In establishing these institutions, Dowd insisted upon their independence from the structures of both Protestant and French Catholic associational networks – thereby underscoring the extent to which the associational culture Dowd advanced was Irish-Catholic in character’.36 Indeed, his steadfast insistence on a resolutely Catholic identity for the Famine Irish in Montreal often brought them into conflict with the city’s French-Canadian and Protestant communities.37

These struggles to create Irish Catholic social institutions were fore-shadowed in the ethno-religious confrontations that took place in the fever sheds. The Grey Nuns’ ‘Typhus of 1847’ annal recounts an escalating sense of conflict in late summer when ‘a great number of Protestants cir-culated in the shelters, and saw with an envious eye the happy catch that the charity and selflessness of our sisters and priests were making daily. A great number converted to Catholicism. Children especially were col-lected with care to be placed in good families’.38 The Protestant newspaper

35 Ibid., 10–11. 36 Kevin James, ‘Dynamics of Ethnic Associational Culture in a Nineteenth-Century

City: Saint Patrick’s Society of Montreal, 1834–56’, Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 26/1 (2001), 59.

37 King, ‘Remembering Famine Orphans’, 130–40.38 ‘The Typhus of 1847’, 84.

258 jason king

the Witness fulminated against such religious conversions.39 ‘There were a considerable number of Protestants among the patients, who had never openly confessed themselves to be such, and forty or fifty who had been nominally converted, in their illness, to Roman Catholicism’, it claimed:

The reason for concealment, on the part of the Protestants [was that] they saw priests and nuns continually going about, and found that nearly everyone around them, whether nurses or patients, belonged to the Church of Rome, and they naturally inferred either that it was a Roman Catholic hospital, or that they would get much better treatment if they said nothing about their Protestantism.

According to the Witness, ‘one man, after letting the priest work his will upon him, lay and moaned, repeating continually that his character was broken’. The paper insists upon the need to separate Protestant patients into their own wards ‘where they may be visited by ministers, and Scripture read-ers, without the interruption arising from the neighborhood Romanists. For such is the hatred of the Gospel’, it laments, ‘that even when they are under the influence of disease, […] they will, if anyone attempts to read the Bible to a neighboring Protestant, often make as much noise as they can to drown out his voice’. The screams of Sister Collins’s patients in the presence of a Protestant Minister seem less defensive than disruptive from the paper’s perspective.

These conflicts also spread along with contagious disease from the fever sheds into the city. It is not sufficiently appreciated that the Famine Irish in Montreal suffered a similar scale of mortality to their counter-parts on Grosse Île but in full public view of the inhabitants of what was Canada’s capital and most populous city, who themselves became infected in turn. There was a constant traffic of Irish emigrants, their benefactors, and onlookers across the permeable boundary that separated the sheds from the surrounding communities.40 This led to considerable public controversy about the increasing risk of an epidemic and the threat of civil unrest. By 10 July 1847, typhus had spread to both the Grey Nunnery

39 ‘Proselytizing at the Emigrant Hospitals’, Witness (23 August 1847).40 Horner, ‘The Public Has a Right to be Protected’, 79–80.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 259

and Hôtel Dieu, and fatalities in the city exceeded those in quarantine.41 Under these circumstances, any public gathering could accelerate the spread of infection.

Fever and Festivity

Nevertheless, crowds continued to congregate in the public spaces of Montreal at the height of the ‘ship fever’ epidemic. In the midst of this catas-trophe, the Irish impresario Samuel Lover performed ‘Paddy’s Portfolio’ at several venues in Montreal in July of 1847 to both critical and popular acclaim. This raised the ire of the Witness, which contrasted such theatrical performances with the spectacle of Irish suffering in the sheds. It noted that

We have Hospital Sheds, capable of holding fifteen hundred human beings at one end of the city, full to overflowing with the victims of want and disease, as ghastly a sight as probably ever was witnessed under the canopy of heaven; and we have a Theatre, just opened at the other end of the city, capable of holding fully more, and also […] crowded to overflowing with men and women of the same flesh and blood with those who are lying dying at the sheds. In one place all is groaning, pain, tears, sickness and death; in the other, all is tinsel finery, mirth, music, and vanity, yet the crowds in both are fast hurrying to the same judgment seat […] Death and the stage are holding their jubilee at the same time, each being in the height of its carnival, in the very flood-tide, as it were, of its saturnalia, […] [in an] unseeming conjuncture in the same city […] of festivity and fever.42

The Witness’s juxtaposition of death and the stage, of fever and festivity as vehicles for the propagation of ‘moral, if not physical contagion’, accentuates the seeming impropriety of performing saturnalian rituals in the shadow of catastrophe. It emphasizes the Irish ethnicity of both groups of fever patients and theatre patrons and performers ‘of the same flesh and blood’

41 Driedger, An Irish Heart, 48.42 ‘The Two Jubilees’, Witness (19 July 1847).

260 jason king

who congregated in public spaces and became a source of infection. Both off and on stage, these venues provided a catalyst and a forum for the nego-tiation of ethnic identity formation that prefigured later social struggles. Like the coffin ships, the fever sheds became carnivalesque and contested spaces in which ethno-religious frictions were stirred.

Nevertheless, the social levelling that took place both on stage and in the sheds also helped to alleviate some of these tensions between natives and newcomers and facilitated their acculturation. As highly performative Irish figures who generated extensive publicity, Lover’s comic spectacle and the tragic plight of fever victims made Montreal residents more recep-tive to the Famine migrants in their midst. The pathos of Irish orphans in quarantine was reported on an almost daily basis and in heart-rending detail. Impromptu adoptions of these stricken children also attested to the permeability of the boundary between the sheds and the surrounding city.43

Famine Memory and the Elision of Ethno-Religious Conflict

Thus, it was both the remembrance of compassion and the erasure of conflict that shaped the cultural memory of Famine migrants in the fever sheds. As Mary Anne Sadlier recounted, it was the ‘strange sight’ of the ‘Sisters of the Hôtel Dieu’ leaving their confines that made an indelible impression not just on her but on many people, who ‘pointed it out to each other with solemn wonder […] and spoke with bated breath of the awful visitation that had brought the cloistered nuns from their convent’.44 Their incongruous appearance ‘in the pestilential atmosphere of the fever sheds’ to care for Famine orphans was highly memorable in itself.45 Inscribed in this sacred

43 ‘The Public Health’, Witness (21 June 1847); ‘The Emigrant Orphans’, Witness (6 July 1847).

44 Sadlier, ‘The Plague of 1847’, 208.45 Ibid.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 261

image of the uncloistered nun with the Irish child is also its sacrilegious opposite: the collective memory of Maria Monk. Elsewhere I have noted that the very same priests and nuns who were venerated for their compas-sion, devotion, and self-sacrifice in the fever sheds in 1847 had been vilified a decade earlier when Maria Monk’s The Awful Disclosures of the Hôtel Dieu Nunnery in Montreal (1836) was first published. The novel became a staple of anti-Catholic nativism and the second best-selling novel in the antebel-lum United States, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin.46 It is inconceivable that Sadlier was unfamiliar with the Awful Disclosures, which accused Montreal’s Irish Catholic parish priest, Father Phelan, of impregnating the cloistered nuns and then burying their offspring in the convent’s cellar around the corner from her house.47 A steady stream of visitors like the Melvilles walked past its front door to see the infamous convent.48

Not only were the city’s Irish Catholic clergy and female religious implicated in the Maria Monk controversy, but in 1847 recently arrived Irish women were alleged to be following in her footsteps. ‘Rumors were circulating that young female Irish emigrants were turning to prostitution’, notes Horner, ‘an accusation that was confirmed by an anonymous gentle-man with links to the Magdalene Asylum, who told the Gazette that several young women had sought refuge with the Magdalene Sisters after being lured into the trade’.49 Indeed, Father Phelan’s successor, Father Patrick Dowd, later declared in an unpublished letter (25 October 1850) that

whole cargoes of widows with small children and young females [who have been] emptied out from the poor houses in the south and west land here not knowing where to turn to – their young exposed to the worst of dangers from their exposed condi-tion […] This is one of our greatest embarrassments in Montreal. Why send out a

46 King, ‘Remembering and Forgetting’, 26–31.47 In 1847, Mary Anne and James Sadlier lived at 179½ Notre Dame street, which was

around the corner from the Hôtel Dieu convent. See Robert Mackay, The Montreal Directory (Montreal: Lovell, 1847), 179.

48 Jenny Franchot, Roads to Rome: The Antebellum Protestant Encounter with Catholicism (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994), 160.

49 Horner, ‘The Public Has a Right to be Protected’, 82. Also see Bradbury, Wife to Widow, 98–9.

262 jason king

poor woman with three or four helpless children to lose herself and them in a strange land where she will have no neighbor or relative to pity or assist her? Hundreds of children are yearly [sent to] this country by the cruel – I would say barbarous policy of your landlords and Poor Law guardians.50

As late as 1855, the same year that Sadlier’s husband James became a Charter Trustee of Father Dowd’s St Patrick’s Orphan Asylum, Dowd noted in the Drogheda Argus that ‘in Montreal we suffered much, and still suffer, from a large importation of very badly conducted girls’ whose reputation has proven ‘damaging to the character of the good Irish girls in this place’.51

These sacrilegious memories of the Awful Disclosures and female sexual impropriety were displaced and repressed in Sadlier’s fiction and subse-quent recollections of the fever sheds. Sadlier had emigrated from Ireland to Montreal in 1844 where she met and married James Sadlier and helped him develop D. & J. Sadlier and Co. into the largest Catholic publisher in North America. In 1847, however, she was still unknown. Indeed, in the Bartholomew O’Brien papers at McGill University’s McCord Museum, which contain an extensive, itemized inventory of texts owned by Montreal’s Irish Catholics in 1849 – an invaluable book history repository to recon-struct the reading habits of an ethnic community – not one Sadlier publi-cation is listed.52 Shortly afterwards, though, she wrote Alice Riordan: The Blind Man’s Daughter (1851), a historical novel set in Montreal in 1839. In Alice Riordan, the plot revolves around the reading habits of young female Irish emigrants and the dangers that are posed by Gothic fiction, which makes them susceptible to seduction and loss of their faith.

More to the point, the novel is partially set within and meticulously describes the interior of the Grey Nunnery, where Alice’s blind father comes to reside, as a place of refuge for Irish orphans and the elderly who

50 Unpublished letter from Father Patrick Dowd, Montreal Seminary, to his father Patrick Dowd, Listulk, Dunleer, 25 October 1850. I am grateful to Gabriel Matthews for making this letter available to me.

51 Patrick Dowd, ‘Letter to the Poor Law Guardians in Drogheda’, Drogheda Argus (24 September 1855).

52 ‘English Books’, Bartholomew O’Brien Papers, McCord Museum, Montreal, box 1, P083/2.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 263

are cared for by the Sisters and the Irish Catholic community’s parish priest, Father Smith, a surrogate for the historical Father Patrick Phelan. As the narrative comes to a crisis, Alice Riordan is tempted by her fellow dress-makers to read Matthew Lewis’s Gothic novel The Monk – the most important source text for Maria Monk – but instead she deliberately rec-ollects ‘the beautiful chapel of the Gray Nunnery […] and the soft sweet voices of the nuns’ to inure herself against ‘impure images emanating from a morbid and diseased imagination’.53 The memory of the ‘Gray Nunnery’ is thus specifically invoked to protect Sadlier’s protagonist as well as her readers from the influence of Maria Monk. More specifically, her allusion to Lewis’s The Monk serves as a screen memory to substitute for and repress more scandalous recollections of The Awful Disclosures of the Hôtel Dieu Nunnery in Montreal. Sadlier recasts anxieties about proselytization and prostitution associated with the Famine Irish into an anti-Gothic allegory and cautionary tale about female susceptibility to sacrilegious rather than sacred role models. Indeed, her veneration of the Grey Nuns requires the suppression of Maria Monk from Irish communal memory. Ultimately, her recollection decades later of female religious piety ‘in the pestilential atmosphere of the fever sheds’54 was filtered by a kind of forgetting of their more unsavoury associations with proselytization and sexual impropriety.

Conclusion

If Famine memory is really to provide what President Mary Robinson proclaimed to be ‘an education in diversity’,55 then it should recall the dif-ferent types of adversity encountered by Irish migrants in 1847. Like the

53 Mary Anne Sadlier, Alice Riordan, the Blind Man’s Daughter (Boston: Patrick Donahoe, 1851), 101–2.

54 Sadlier, ‘The Plague of 1847’, 208.55 Robinson, ‘Address’.

264 jason king

coffin ships, the fever sheds have become established not only as a site of memory but also as a vehicle for the negotiation of Irish identity formation in which widespread ethno-religious and social tensions were compressed and defined. Certainly the annals of the Grey Nuns recall their compas-sion and heroic self-sacrifice, but they also attest to considerable cultural conflict and deeply entrenched fears of religious conversion that provided an impetus for Irish institution-building which became obfuscated and overshadowed in subsequent commemoration. Their struggle to consecrate shed number eight anticipates subsequent Irish communal endeavours to create its own social infrastructure. The establishment of Father Dowd’s St Patrick’s Orphan Asylum under the trusteeship of James Sadlier and later St Bridget’s Refuge for the Old and Infirm ‘reinforced the “national” identity of Irish Catholics in Montreal’ in the decades that followed.56 The remembrance of ethno-religious and social conflict in the sheds also pro-vides a salutary reminder that the Famine migrants were never passively assimilated but negotiated the terms of their integration into wider host societies. The consignment of their memory of conflict to a disposable past was a vital part of their acculturation.

56 Sherry Olson, ‘St Patrick’s and the Irish Catholics’, in Dominique Deslandres, John A. Dickson, Ollivier Hubert, eds, The Sulpicians of Montreal: A History of Power and Discretion, 1657–2007 (Montreal: Librairie Wilson & Lafleur, 2013), 315; Olson and Thornton, Peopling the North American City, 237–42, 270–2, 350–2.

The Remembrance of Irish Famine Migrants in the Fever Sheds of Montreal 265

Figure 16: Théophile Hamel’s Le Typhus (Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel/Museum Marguerite-Bourgeoys 1848).