The Materialization of Culture, in Rethinking Materiality (eds E DeMarrais, C Gosden, and C...

Transcript of The Materialization of Culture, in Rethinking Materiality (eds E DeMarrais, C Gosden, and C...

11

The Materialization of Culture

Chapter 1

The Materialization of Culture

ties, élites disproportionately direct or control theseactivities, as they generally have greater access toboth material and organizational resources. In de-veloping our approach, we stressed the importanceof understanding these activities in order to investi-gate agency and competition for power. We furtherargued that, where evidence exists, archaeologistsshould try to interpret symbols and their meaningsas far as possible. Finally, we emphasized that ananalysis of the materialization of ideology shouldseek to reveal the processes and mechanisms thatallow ideas and concepts to become broadly sharedamongst members of a society.

In order to link this last objective with thethemes explored in the present volume, I wish tohighlight a concern for understanding how ideas orconcepts achieve the status of ‘taken-for-granteds’or become ‘instititutional facts’ (Searle 1995). Initialefforts toward understanding the material basis ofthese social phenomena appear promising. For ex-ample, Earle (2001, 107) has argued that landscapefeatures are particularly effective for materializingsocial institutions because of their scale, visibility,and permanence. Similarly Renfrew (2001) arguesthat some institutional facts (those elements of sociallife dependent upon public agreement), such as cur-rency or the conventions of potlatch, depend criti-cally upon their material referents (e.g. coins usedfor a purchase or the goods accumulated and dis-played in anticipation of the potlatch).

In this paper,2 I seek to widen the discussion ofmaterialization beyond ideology and élite powerstrategies. Although in our earlier formulation, weasserted that the materialization of ideology is partof a broader process — the materialization of culture— these ideas have not yet been explored in anydetail. The materialization of culture may be definedas the transformation of ideas, values, stories, myths,and the like into a material, physical reality. In thesections that follow, I argue that the materialization

Elizabeth DeMarrais

In an earlier paper, my colleagues and I (DeMarraiset al. 1996) discussed the materialization of ideology1

as a means to highlight the active process thatunderlies the creation, dissemination and manipula-tion of ideologies. Our approach involved a mater-ialist perspective (see Introduction this volume), aswe were concerned with understanding politics,power relations, and the manipulation of resources.Using case studies, we highlighted the means bywhich concepts are given concrete, physical form, aspart of human interactions with symbols and icons,performances, monuments, and written texts. Fromour perspective, understanding the materializationof ideology facilitated recognition of economy, socialorganization, and symbolic practices as interdepend-ent spheres of human activity, particularly in large-scale societies.

The dissemination of symbols reflecting estab-lished concepts and ideas is critical for communicat-ing an ideology across a wide region, as seen, forexample, in the dissemination of the ‘great art styles’of the pre-Hispanic Americas. In our view, however,this activity constituted only one aspect of a broader,active, and reflexive process. We wrote that

. . . [i]n speaking of materialization we emphasizethe ongoing process of creation and do not assumethe primacy of ideas. In fact, ideas and norms areencapsulated as much in their practice and in theconditions of daily life as in individuals’ minds. Tomaterialize culture is to participate in the active,ongoing process of creating and negotiating mean-ing. Because ideology is part of culture, materiali-zation of ideology is a similar process, usuallyundertaken by dominant social segments (DeMarraiset al. 1996, 16)

Further, although we acknowledged the materialityof everyday life, our discussion focused primarilyupon the production, control, and manipulation ofhighly visible, elaborate symbols and icons, events,and monumental architecture. In large-scale poli-

12

Chapter 1

of culture (as an active, reflexive process) providesscope for thinking about the ways that knowledge,social practices, and material culture articulate toestablish contexts for social interaction. I suggestthat the concept of tradition can highlight the waysthat, through activities, culture is broadly shared.Finally, I consider (using an example from the southAndes) how analysis of the materiality of settings inthe archaeological record can shed light on aspectsof culture and social organization in past societies.

Social practice and materiality

Ethnographers have argued, in recent work, that so-cial practices involve not so much the representationof abstract symbolic realms, but rather an ongoingprocess of making and remaking social reality (Toren1999; Ingold 2000). Toren (1999, 18), for example,argues that meanings and knowledge are seldomsimply ‘received’ by individuals; instead they arecontinually ‘made anew’ through the materiality ofpractices. The emphasis placed upon practices is valu-able, as well as intuitively satisfying, since it is clearthat individuals — through their activities — createand transform their social realities. In common withthese authors (and with many contributors to thisvolume), I find it constructive to view the relation-ship between human beings and the material worldas an active, agent-centred process.

At the same time, building on Bourdieu’s (1990,57) influential insights, I believe that agency must beconceptualized in terms of a dialectic relationshipwith structure, or, in simpler terms, with referenceto the ‘rules of the game’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant1992, 22). While archaeologists routinely acknowl-edge that agency is enabled and constrained by struc-ture, some researchers emphasize the former to adegree that agents become ‘over-active’ or even‘hyper-active’, (a view criticized recently by Moore(2000, 260)). Here, I direct attention to the ways thatthe materiality of the world contributes to the gen-eration of the ‘durable, adjusted dispositions’ towhich Bourdieu has drawn attention. Specifically,the concept of habitus refers to a

. . . structuring mechanism that operates from withinagents, though it is neither strictly individual norin itself fully determinative of conduct . . . Habitusis creative, inventive, but within the limits of itsstructures, which are the embodied sedimentationof the social structures which produced it . . .(Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992, 18–19).3

To the extent that practices and experience are widelyshared, so are common evocations and associations

of symbols and other forms of material culture(Hodder 1999; Brumann 2002). This process gener-ates the

. . . permanence and cumulativity of material andsymbolic acquisitions . . . [which] can then subsistwithout the agents having to recreate them con-tinuously and in their entirety by deliberate action(Bourdieu 1977, 184).

Social interaction depends upon these ‘material andsymbolic acquisitions’ and upon the mutual intelli-gibility of symbols as well as actions. Sharedunderstandings encompass both conscious and ex-plicit forms of knowledge as well as the unconscious,embodied dispositions and routines of habitus. Im-portantly, to suggest that these shared under-standings exist is not to argue that they are the samefor any two individuals. Indeed, it is precisely thevariability of these understandings and the materialforms by which they are materialized that makesreference to a broad, general concept such as cultureessential, as I argue in the next section.

Culture and tradition

Definitions of culture vary widely, but many em-phasize the set of ideas, meanings, beliefs, knowl-edge, institutions, practices, and material thingsshared amongst the members of a society. In a recentoverview, Goodenough (2003, 6) suggests that

. . . culture . . . consists of what humans learn asmembers of societies, especially in regard to theexpectations their fellow members have of them inthe context of living and working together. Cul-ture, in this sense, . . . [does] not consist of patterns ofrecurring events in a community . . . Rather, as some-thing learned, culture . . . [is] like a language, whichis not what its speakers say but what they need toknow to communicate acceptably with one another,including constructing utterances never made be-fore yet immediately intelligible to others . . .

Because culture consists of what each individual haslearned, he continues, it must be located in eachindividual’s mind and body. Culture is variable fromone individual to the next, but achieves coherence intraditions and shared understandings (Barnes 1988).Goodenough (2003, 7, emphasis added) argues fur-ther that

. . . a community’s cultural makeup . . . thoughchanging through time in response to a number ofdifferent processes . . . [is] not the basic unit ofcultural evolution. Discrete bundles of how to dothings, such as build a house or celebrate a mar-riage, become relatively distinct traditions as they

13

The Materialization of Culture

are passed down across generations. These tradi-tions are the main units of cultural evolution andchange . . .

While Goodenough does not focus explicitly on ma-terial culture, his formulation articulates a clear link-age between culture and activities (through tradition).Since traditions involve activities (such as the build-ing of a house or the making of a pot), we can beginto envision more clearly the dialectic between struc-ture and agency, as individuals engage with mate-rial things as part of the unfolding of the activities ofdaily life.

Thinking about the materialization of culturedraws attention to the interaction of knowledge, so-cial practices, and material things. Bourdieu (seeabove; also Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992, 19) and oth-ers (Kus & Raharijaona this volume) refer to an on-going process of sedimentation of local knowledge asindividuals and groups solve the problems of theirdaily lives. Individuals accumulate a store of knowl-edge and experience that is materialized in theiractivities and in the things of the world and to whichthey have ongoing access as they confront new situ-ations. The archaeological record consists primarilyof the material traces of repeated activities and henceit is particularly well-suited to investigating and char-acterizing this process of sedimentation. Bourdieu(1990, 57–8) writes of a ‘history objectified in institu-tions’ while Arroyo-Kalin (this volume) also empha-sizes the historical dimensions of this dynamic,arguing that engagement with the material worldpresupposes, and depends upon, a set of prior rela-tions and dispositions that linked agents and theirmaterial surroundings.

My aim here is not to redirect attention towardstructure at the expense of a dynamic conception ofagency; however, I do wish to emphasize themateriality of habitus, as seen for example in theubiquitous cues in the built environment that guidemovement, shape behaviour, and structure socialinteraction (see Watkins this volume). These elementsof habitus are ‘. . . inculcated as much, if not more, byexperience as by explicit teaching’ (Jenkins 1992, 76).In the following section, I shall consider the implica-tions of these ideas for archaeological investigation,to show how an analysis of the materiality of a set-ting reveals aspects of social organization and cul-tural practices.

As a final point, it is essential to note that be-cause the materialization of culture involves mate-rial things and labour, analysis must also considerthe conscious (and strategic) intentions of social ac-tors and their capacities for action. Agency depends

upon cultural competence (Cohen 1987), but also —sometimes crucially — upon the position of an agent(or agents) vis-à-vis others in the community. EricWolf recently articulated the relationship betweenculture, power, and materiality, and his elegant for-mulation is worth quoting at some length:

The concept of culture remains serviceable as wemove from thinking about what is generically hu-man to the specific practices and understandingsthat people devise and deploy to deal with theircircumstances. It is precisely the shapeless, all-en-compassing quality of the concept that allows us todraw together — synoptically and synthetically —material relations to the world, societal organiza-tion and configurations of ideas. Using ‘culture’,therefore, we can bring together what might other-wise be kept separate. People act materially uponthe world and produce changes in it; these changesthen affect their ability to act in the future. At thesame time, they make and use signs that guidetheir actions upon the world and upon each other.In the process they deploy labor and under-standings and cope with power that both directsthat labor and informs those understandings. Then,when action changes both the world and people’srelationships to one another, they must reappraisethe relations of power and the propositions thattheir signs have made possible . . . (Wolf 1999, 288–9)

In summary, I have suggested that the analysis ofmaterialization can move beyond asking what a givenicon or monument may ‘symbolize’ or ‘stand for’.We can inquire about the associations, values, memo-ries, and meanings materialized in the objects, prac-tices and settings of daily life; indeed, as Bradley(this volume) notes, in many societies it may not bepossible to distinguish a ‘symbolic’ or ‘ritual’ sphereof activity from that of the ‘everyday’.

With these ideas in mind, we can ask furtherquestions about the potentials of distinct categoriesof material (objects, rituals, and the built environ-ment4) to materialize culture. For example, objectsmight materialize the techniques and skills involvedin manufacture or procurement; a ‘mental template’in the mind of the artisan; the social or ethnic iden-tity of the artisan; intended functions; messages aboutstatus or social position; or sacred ideas, religiousbeliefs, and cosmology. Events and rituals also ma-terialize culture, because they incorporate objects andperformers and are conducted in structured settings.Rituals may materialize the social order by enacting(and in some cases transforming) social conventionsor rules of conduct; rituals may further materialize

14

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1. Map of the northern Calchaquí Valley, Argentina, showing the location of modern towns and thearchaeological site of Borgatta (SSalCac 16).

.

15

The Materialization of Culture

elements of the supernatural, in the process express-ing and reworking aspects of worldview or cosmol-ogy. Finally, the built environment, because itcomprises both buildings and settings for activities,has the same potentials as objects and rituals, as Idiscuss in the next section.

The materialization of culture: analysis of thesetting

In the remainder of this paper, I consider how inves-tigation of the materiality of the setting (Rapoport1988; 19905) can provide insights into social organi-zation, ritual activity, and tradition. The example isdrawn from recent research in the northern CalchaquíValley, located in the province of Salta, northwestArgentina. In this region, mountains rise steeply onboth sides of the valley floor, reaching elevations ofalmost 6400 m on the western side. Moist windsfrom the Atlantic are blocked on the eastern edge tocreate a rain shadow. Precipitation is therefore scarceand agriculture is limited to the irrigable lands alongthe Calchaquí River and its tributaries. Other pro-ductive resources include pastures for camelids anddeposits of mineral ores and precious stones. Around100 BC, small villages appeared along the main riverand, later, in transverse quebradas including CachiAdentro (Fig. 1.1). Archaeological evidence and docu-mentary sources characterize the Regional Develop-ments period (c. AD 1000–1445) as a time of populationgrowth and rapid change (Díaz 1992; DeMarrais 1997;González & Pérez 1990; Raffino 1991; Tarragó 1974;2000; Tarragó & De Lorenzi 1976).

The indigenous peoples of the Calchaquí prac-tised bronze metallurgy from an early date and, dur-ing the Regional Developments period, developed atradition of infant and child burial in funerary urns.The urns, decorated with elaborate geometric, an-thropomorphic, and zoomorphic representations(González 1979; Serrano 1953; 1976) and diagnosticof the Santamariana culture, are broadly distributedthroughout northwest Argentina (Bennett et al. 1948).Colonial period documents describe a ‘cultural mo-saic’ of ethnic groups (Lorandi & Bunster 1987–88;Lorandi & Boixadós 1987–88) across the region. Com-munities were small and widely scattered (Sotelode Nárvaez 1885, II, 147), and the documents stressthe ‘tribal’ nature of political organization. Leadersapparently derived authority from coordinatingdefense, and Lozano (1874–75, IV) observes that alli-ances were formed only in times of conflict. Theauthority of leaders diminished in times of peace(Márquez Miranda 1942, 10; see also Lozano 1874–

75, IV, 163, 174; V, 209). The impression that emergesfrom the documents6 is one of relatively small-scalepolities and incipient leadership.

Recent archaeological investigations7 suggestthat, although some settlements were sizeable, cov-ering areas as large as 25–30 ha or more, withpopulations of several thousands, the most visibleforms of ritual and symbolic activity involved prac-tices undertaken within households, relating to in-fant and child burial under the floor. The discussionhere focuses on one large community, known locallyas Borgatta (Fig. 1.2), whose main sector is 25 ha insize, with 250–300 residential enclosures arrangedaround open patios to form ‘patio groups’. Despiteextensive investigation, Borgatta has not yielded evi-dence of a discrete sector of élite, or higher-status,patio groups, although the upper, terraced slopes docontain some larger, better-constructed enclosures.Although Borgatta is larger and its layout more com-plex than that of surrounding villages (Fig. 1.3), ourexcavations have uncovered little material evidencefor social inequality, or for integrating activities8 be-yond the level of the household.

The lack of evidence for the materialization of ahierarchical social structure at Borgatta raises ques-tions about the nature of social and political organi-zation. As Brumfiel (2000, 250) has argued recently,when social inequalities and status differences arepresent, archaeologists often find them relatively easyto identify, because they are usually clearly materi-alized and hence prominent and visible. Archaeolo-gists interested in studying societies where socialdifferentiation or social hierarchy are less clearly de-veloped, however, may be harder pressed to iden-tify the alternative forms of social division — thosebased, for example, on ‘age, gender, ethnicity, line-age, [or] locality’ — that shaped the social fieldswithin which social actors were embedded.

At Borgatta, given limited material evidencefor social differentiation or leadership, it makes senseto consider alternative forms of social division mate-rialized in the built environment. One approach tothis problem is to identify distinct settings. The con-cept of the setting is drawn from environment-behaviour studies; by definition, a setting incorpo-rates not only architecture, but also the furnishings,portable objects, and the people involved in a givenevent or activity (Rapoport 1988). Settings shape so-cial practices primarily through nonverbal forms ofcommunication, especially cues for behaviour. Forexample, the furnishings, decorations, and sacredimages inside a Christian church, in conjunction withits architecture and layout, comprise a set of redun-

16

Chapter 1

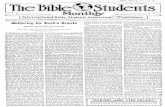

Figure 1.2. Schematic site plan of the south sector of Borgatta, showing the layout of earthen mounds, plaza, andresidential sectors.

Plaza

910

908

902

modernhouse

mound

mound

Rid

ge

Hills

mound

Hills

Borgatta

South sector

0 25 50 m

N

E.D. 1996

901

903

909

905

907

S Sal Cac 16

17

The Materialization of Culture

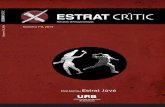

Figure 1.3. Surface architectureof Borgatta, looking northeast. Inthe foreground on the left side thewall stones defining a semi-subterranean enclosure arevisible. In the background, anelongated mound is visible,surrounding a cluster ofdeteriorated enclosures (locatedbehind, and to the left of, thefigure in the photo).

16=15-40

16=13

Patio

C

Mound

?

?

?

N

0 5 10 m

mound

Figure 1.4. Detailed plan of aresidential sector at Borgatta.Although it is difficult to identifypatio groups clearly from surfacearchitecture, one example of awell-defined patio group can beseen at the south end. Threesmaller enclosures lie adjacent tothe patio on the north side; eachhad access to the patio. The patiois enclosed by a low earthenmound along its south and westedges. Black lines show stone wallfoundations, while numbers referto excavated areas. The hatchedlines show areas of deterioratedsurface architecture and smallcircles mark the locations of adultcist tombs interspersed amongstthe enclosures.

18

Chapter 1

dant cues that remind visitors how to behave. Bydefining settings, the built environment makes mean-ingful ‘co-action’ possible and — importantly — aidsother, more explicit forms of communication andinteraction, such as speech events. Rapoport (1988,323–4) observes that

. . . the semi-fixed elements [e.g. portable objectsand furnishings] are indeed the most important inthe communication of environmental meaning . . .[consequently] the overlap between built environ-ments and what anthropologists and archaeolo-gists call material culture becomes clearer and moreimportant . . .

In the analysis of Borgatta, then, the first problemwas to identify settings, with the additional aims ofassessing where activities took place, who was in-volved, and how they were organized. Returning tomy earlier discussion, I also considered the visibil-

ity, through materialization, of traditions structur-ing the activities that took place within the site.

The patio group as a setting for ritualEncompassing some 250–300 residential enclosuresinterspersed with low earthen mounds, paths, and aplaza, the settlement exhibits an irregular layoutmarked by substantial variation. The impression isthat of a community that grew gradually during thethree centuries following AD 1000, without centralplanning. As mentioned earlier, individual residen-tial enclosures were grouped around unroofed pa-tios to create patio groups (see DeMarrais 2001)probably occupied by members of an extended fam-ily. Patio groups differ widely in their dimensions,layout, and in numbers of component structures,reinforcing the impression that the site grew slowlythrough agglomeration of new residences over time.

The construction of discrete patio groups, re-peated many times across the site, reveals a concernwith providing space for the daily activities of thehousehold, but the patio group was also a setting (inRapoport’s sense) for ritual. Infants and children wereburied within decorated urns under the floor. Infanturn burial took place in a setting that incorporated

Figure 1.5. A Santamariana funerary urn with modelledfeatures in the form of a human face, with serpents andgeometric designs in red and black.

Figure 1.6. A Santamariana funerary urn, painted witha face and geometric designs, in red and black on white.

19

The Materialization of Culture

fixed features (the patio group) aswell as portable objects (the urns)and the people who participated inthe burial rite. The placement of de-ceased infants under the floor,within the patio group itself, high-lighted the household unit as a keysetting for ritual. The patio group’swalls and layout furnished cues thatmarked the boundaries of the patiogroup, controlled access, and di-vided the space internally (Fig. 1.4).

Funerary urnsSettings include portable objects aswell as architecture, and certainlythe most dramatic element of sym-bolic material culture within the site(and the region) were funerary urns.The urns communicated messagesthrough an elaborate iconography

ing Santamariana cultural identity and cosmology.Although we cannot yet interpret the meanings ofthe symbols, they are rich and varied, representingboth animals and human beings. The longevity ofthis symbolic tradition and its wide distribution,among communities that did not share common lead-ership are notable. Household-based ritual — andparticularly the urns themselves — were a focus ofactivity within the community.

Debris from other craft-production activities,including bronze metallurgy, shell-bead manufac-ture, textile production, and lapidary work is alsopresent at Borgatta, suggesting that the materializa-tion of culture may have taken shape in materialmedia other than pottery. Nevertheless, the densi-ties of objects, tools, and debris suggest that the over-all intensity of these activities was relatively low,although it is likely that some perishable materials,such as textiles or carved wood, were important me-dia for materializing culture alongside the funeraryurns. To date, however, only low densities of spin-dle whorls have been recovered from excavations,and thus it seems unlikely that textiles were as nu-merous or as visible as the funerary urns.

DiscussionThroughout the world, sub-floor burials and rever-ence for ancestors are common focal points for ritual,as seen more widely in the Andes as well as in earlyNeolithic sites of central Anatolia (Hodder 2000, 29–30). Therefore, while the presence of ritual centred inthe patio group is not altogether surprising, what is

Figure 1.7. An infant burial in a plain-ware pot being excavated fromunderneath the floor in the corner of a large enclosure at Borgatta.

depicting serpents, birds, and frogs, as well as hu-man forms and faces. Tall and narrow, with an ovoidcross-section and everted rim, some urns stand astall as 75 cm. Some urns are modelled to resemblehuman forms, complete with plastic modelling ofeyes, eyebrows, mouth, and ears (Fig. 1.5), whileothers have arms painted or modelled on the lowerportion of the vessel. Still other vessels have ex-tended necks to which the features of a human facehave been added using both painted and modelledfeatures. Like the individuals buried inside them,each urn is unique. In addition to their unusual forms,which are perhaps suggestive of the human body,urns are decorated with painted designs. Most aresubdivided into distinct sectors, each decorated withmotifs including cross-hatching and spirals,zoomorphic images (especially birds and snakes),and anthropomorphic features9 (Fig. 1.6).

Although the urns were used as containers forburial, their decorative treatment suggests that theywere also perceived as canvases10 for a complex ico-nography. The urns vary locally in form, decoration,and paste, but the consistency of the iconographyand general form is also notable for its wide distri-bution across northwest Argentina (Baldini 1980).My regional survey of the area revealed that largercommunities yielded higher densities of urn sherds(in surface collections) than did smaller sites, al-though urn sherds were found on the surfaces ofalmost all sites from this time period. This ubiquitysuggests that the rituals and symbols associated withinfant and child death were a focal point materializ-

20

Chapter 1

striking about Borgatta is the absence of other well-defined settings for ritual or public activity. Formalpublic buildings are absent, although there is a plaza(or cleared space, measuring 60 × 100 m) in the NWsector. Our excavations there reveal that this ‘plaza’was regularly swept clean, although concentrationsof debris around the edges contained decorated pot-tery, including bowls. It is therefore reasonable tosuggest that feasting took place within the settle-ment, reflected by the presence of libation bowls inthe ceramic assemblage more generally. Neverthe-less, it remains difficult to identify the settings, andhence to infer the intensity or scale, of feasting ac-tivities. It is entirely possible that feasting took placeprimarily within individual patio groups, rather thanin public spaces (as suggested for the late LIP poli-ties of the Upper Mantaro Valley, Peru: see DeMarrais2001), although we have not yet recovered sufficientarchaeological evidence from Borgatta to resolve thisquestion.

The rituals accompanying the burial of infantsin urns under the floor therefore can be said to havecomprised a tradition, with each individual burialrite reinforcing the social and spatial autonomy ofthe patio group. The burial of infants under the floorssuggests continuity through time in the occupationof the patio group, an impression reinforced by theuse of stone as a building material. At the same time,settings are never determining, and there was con-siderable scope for agency. The fact that each urn isunique in its form and decoration reflects the agencyof both the potter and the individual who paintedthe urn (if indeed these were different individuals).Additionally, some infants and children were buriedin undecorated pots, rather than in decorated urns(Fig. 1.7), which hints — potentially — at social dif-ferentiation along one of the dimensions suggestedby Brumfiel (2000). Still another variation is visiblein the burial of funerary urns in cemetery sectorsoutside the residential sectors. A final, recent dis-covery has been a vessel buried with its rim juttingout above the floor, suggesting that the occupantshad ongoing access to the contents.

For a settlement of its size and density of occu-pation, Borgatta displays limited evidence for formalpublic activities, institutions of political hierarchy,and prestige goods or imported luxury items. Thesite contains a high density of decorated funeraryurns, however, whose idiosyncratic features of pasteand decoration conform broadly to the Santamarianaregional cultural tradition. Given their large size,overall quantities, and elaborate decorative treat-ments, the urns constitute a dramatic and visible

element within the symbolic assemblage recoveredfrom Borgatta and other northern Calchaquí Valleysettlements.

Further work is needed to understand the or-ganization of ceramic production within the site andregion, although the urns appear to have been pro-duced locally, perhaps by part-time specialists. Al-though the form and firing of an urn may not, byitself, have required great skill, the range and elabo-rateness of the painted decorations suggest at least apractised hand. The urns therefore signal not onlythe local character of production activities and ritualorganized at the household level; they also material-ize a cultural identity shared across a broad region.Coupled with the relatively limited material evidencefor political hierarchy, it is tempting to see the pro-duction of urns responding to what Spielmann (1998,153) has recently characterized as ‘. . . the demandsof ritual performance [that] may underwrite the spe-cialized production of esoteric, intricate, skillfullymade items’ which have ‘. . . considerable spiritualpower’. Why did the urn, rather than other materialthings, take on such importance at Borgatta and othersites? This question is not easy to answer, althoughas a starting point, we might consider the integrat-ing potential of ritual in societies where hierarchi-cal relationships and leadership are not welldefined.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have suggested that analysis of thematerialization of culture can help to reveal the waysthat knowledge, social practices and material cul-ture articulate to establish contexts for social action.If culture is seen as something learned as well asinculcated (as habitus), then the concept of a tradi-tion helps us to see how activities and practicalknowledge are broadly shared, as traditions arehanded down through generations. The materialityof the world of things and settings plays a key role ingenerating habitus, producing the embodied disposi-tions that allow spontaneity and creativity, but alsoorient agency along the lines of a collective social‘logic’ embedded in history and precedent.

Applying these ideas to an archaeological ex-ample from the Calchaquí Valley, Argentina, I haveargued that the investigation of settings (a conceptfrom built environment studies: Rapoport 1988), ena-bles us to identify where activities took place, thematerial symbols and other objects that were in-volved, who participated, and how the activity wasorganized. The analysis of settings in the commu-

21

The Materialization of Culture

nity of Borgatta reveals that a rich and elaboratesymbolic material culture (most importantly funeraryurns) was produced and used for child and infantburial rituals that took place within the household. Ithas been more difficult to identify other settingswithin the site, such as those used for larger-scalepublic rituals or feasting. Research at the site is con-tinuing, but current evidence indicates that the patiogroup was an important locus of daily activity aswell as ritual.

Notes

1. Ideology is ‘. . . a system . . . of ideas, strategies,tactics, and practical symbols for promoting, perpetu-ating, or changing a social and cultural order; in briefit is political ideas in action’ (Friedrich 1989, 301).This is a critical conception of ideology (Thompson1990), acknowledging ideology as symbols used tocreate and maintain power and authority, but whichthemselves belong to broader spheres of symbolic ac-tivity — to what might be termed a worldview orcosmology (Wolf 1999).

2. I have benefited from discussions and from teachingan undergraduate course on this subject with ColinRenfrew, whose ideas have led me to think in newways about materialization. Other colleagues havekindly provided comments and reactions to earlierdrafts of this paper, including Kirsten Olson and Timo-thy Earle and many of the participants at the confer-ence. I would like especially to thank ManuelArroyo-Kalin for commenting in detail on an earlierdraft and focusing my attention on the historical di-mensions of engagement and materialization. Anyerrors are of course my own.

3. Perhaps most tellingly, Bourdieu writes: ‘Of all formsof “hidden persuasion” the most implacable is theone exerted, quite simply, by the order of things’(Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992, 168).

4. In our original paper (DeMarrais et al. 1996), my co-authors and I described four ‘means’ for the materi-alization of ideology: monuments, icons or symbols,events, and written texts. Although written texts arean important means of materializing culture in liter-ate societies, I do not discuss them here for reasons ofspace. In discussing the materialization of culture, Ialso find the term ‘built environment’ (as elaboratedlater in the chapter) more appropriate than ‘monu-ments’ because it encompasses the full range of cul-turally-constructed settings for human activities.

5. The concept of the setting can be extended to consider‘systems of settings’, which for reasons of space I donot explore further here, but see Ingold (1993),Rapoport (1990), Ashmore (2002).

6. The documents must be interpreted cautiously, asthey describe an indigenous political landscape thathad been dramatically transformed, first by the Inkaconquest and resettlements, and then during a period

of prolonged resistance to Spanish rule.7. The results described here were obtained as part of a

broader archaeological field project, the ProyectoArqueológico Calchaquí. Kirsten Olson contributedto the success of the research at Borgatta, and I grate-fully acknowledge her assistance. I also gratefully ac-knowledge financial support from the John Heinz IIIFamily Foundation, a Gibbs Travelling Fellowshipfrom Newnham College (Cambridge), the McDonaldInstitute for Archaeological Research, and two grantsfrom the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropologi-cal Research.

8. When I began my research at Borgatta, I expected(based on site size and density of residential occupa-tion) to find evidence of public activities that involvedmost, or perhaps all, members of the community orpolity, in the form of settings or architectural com-plexes used for large-scale ritual or feasting. To date,settings for these activities have not been found, withthe exception of the plaza.

9. The most common colour schemes include black-on-white, red-on-black, or black-and-red-on-white, al-though some vessels have black designs painted ontothe (orange- or beige-coloured) undecorated clay sur-face.

10. The notion of the vessel as a surface or canvas forpainting is set out by Brody (Brody et al. 1983, 76) inan analysis of Mimbres bowls.

References

Ashmore, W., 2002. ‘Decisions and dispositions’: socializ-ing spatial archaeology. American Anthropologist 104,1172–83.

Baldini, L., 1980. Dispersion y cronología de las urnas detres cinturas en el noroeste argentino. Relaciones dela Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 14, 49–61.

Barnes, B., 1988. The Nature of Power. Cambridge: PolityPress.

Bennett, W.C., E.F. Bleiler & F.H. Sommer, 1948. NorthwestArgentine Archaeology. (Yale University Publicationsin Anthropology 38.) New Haven (CT): Yale Uni-versity Press.

Bernbeck, R., 1999. Structure strikes back: intuitive mean-ings of ceramics from Qale Rotam, Iran, in MaterialSymbols, ed. J. Robb. (Occasional Paper 26.)Carbondale (IL): Center for Archaeological Investi-gations, Southern Illinois University, 90–111.

Bourdieu, P., 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cam-bridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P., 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford (CA):Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. & L. Wacquant, 1992. An Invitation to Reflex-ive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Brody, J., C. Scott & S. LeBlanc, 1983. Mimbres Pottery.New York (NY): Hudson Hills Press.

Brumann, C., 2002. On culture and symbols. Current An-thropology 43, 509–10.

Brumfiel, E.M., 2000. On the archaeology of choice: agency

22

Chapter 1

studies as a research stratagem, in Dobres & Robb(eds.), 249–55.

Cohen, I., 1987. Structuration theory and social praxis, inSocial Theory Today, eds. A. Giddens & J. Turner.Oxford: Polity Press, 273–308.

DeMarrais, E., 1997. Materialization, Ideology, and Power:the Development of Centralized Authority among thePre-Hispanic Polities of the Valle Calchaquí, Argentina.Ann Arbor (MI): University Microfilms.

DeMarrais, E., 2001. The architecture and organization ofXauxa communities, in Empire and Domestic Economy,eds. T. D’Altroy & C. Hastorf. New York (NY): Ple-num Press, 115–53.

DeMarrais, E., L. Castillo & T. Earle, 1996. Ideology, mate-rialization, and power strategies. Current Anthropol-ogy 37, 15–31.

Díaz, P.P., 1992. Sitios arqueológicos del Valle Calchaquí(IV). Estudios de Arqueología (Museo Arqueológicode Cachi) 5, 63–77.

Dobres, M. & J. Robb (eds.), 2000. Agency in Archaeology.London: Routledge.

Earle, T., 2001. Institutionalization of chiefdoms: why land-scapes are built, in From Rulers to Leaders, ed. J.Haas. New York (NY): Plenum, 105–24.

Friedrich, P., 1989. Language, ideology, and politicaleconomy. American Anthropologist 91, 295–312.

Goodenough, W., 2003. In pursuit of culture. Annual Re-view of Anthropology 32, 1–12.

González, A.R., 1979. The Pre-Columbian metallurgy ofNW Argentina, in Pre-Columbian Metallurgy of SouthAmerica, ed. E. Benson. Washington (DC): Dumbar-ton Oaks, 133–202.

González, A.R. & J.A. Pérez. 1990. Historia Argentina 1:Argentina indígena, vísperas de la conquista. BuenosAires: Editorial Paidos.

Hodder, I., 1999. The Archaeological Process: an Introduction.Oxford: Blackwell.

Hodder, I., 2000. Agency and individuals in long-termprocesses, in Dobres & Robb (eds.), 21–33.

Ingold, T., 1993. The temporality of the landscape. WorldArchaeology 25, 152–74.

Ingold, T., 2000. Making culture and weaving the world,in Matter, Materiality, and Modern Culture, ed. P.Graves-Brown. London: Routledge, 50–71.

Jenkins, R., 1992. Key Sociologists: Pierre Bourdieu. London:Routledge.

Lorandi, A. & R. Boixadós, 1987–88. Etnohistória de losValles Calchaquies en los siglos XVI y XVII. Runa17–18, 263–420.

Lorandi, A. & C. Bunster, 1987–88. Reflexiones sobre lascategorías semánticas en las fuentes del Tucumáncolonial. Los Valles Calchaquíes. Runa 17–18, 221–62.

Lozano, P.S.J., 1874–75. Historia de la conquista del Para-guay, Río de la Plata y Tucumán. 5 vols. Buenos Aires:Imprenta Popular.

Márquez Miranda, F., 1942. Los Diaguitas y la guerra.Anales del Instituto de Etnografia Americana 3, 83–117.

Moore, H., 2000. Ethics and ontology, in Dobres & Robb(eds.), 259–63.

Raffino, R., 1991. Poblaciones indigenas en Argentina. Bue-nos Aires: Tipográfica Editora Argentina.

Rapoport, A., 1988. Levels of meaning in the built envi-ronment, in Cross-cultural Perspectives in NonverbalCommunication, ed. F. Poyatos. Toronto: C.F. Hogrefe,317–36.

Rapoport, A., 1990. Systems of activities and systems ofsettings, in Domestic Architecture and the Use of Space:an Interdisciplinary and Cross-cultural Study, ed. S.Kent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 9–20.

Renfrew, C., 2001. Symbol before concept: material en-gagement and the early development of society, inArchaeological Theory Today, ed. I. Hodder. Cam-bridge: Polity Press, 98–121.

Searle, J., 1995. The Construction of Social Reality. London:Penguin.

Serrano, A., 1953. Consideraciones sobre el arte y la cronologiaen la region Diaguita. Buenos Aires: Publicacionesdel Instituto de Antropologia, Universidad Nacionalde Litoral, Facultad de Filosofia, Letras y Cienciasde la Educación 1.

Serrano, A., 1976 [1958]. Manual de la cerámica indígena,tercera edicion. Córdoba (Argentina): EditorialAssandri.

Sotelo de Narváez, P., 1885 [1583]. Relación de lasProvincias del Tucumán, in Relaciones geográficas deIndias, II, ed. M. Jiminez de la Espada. Madrid:Ministerio de Fomento, 143–53.

Spielmann, K., 1998. Ritual craft specialists in middle rangesocieties, in Craft and Social Identity, eds. C. Costin &R. Wright. (Archeological Papers 8.) Arlington (VA):American Anthropological Association, 153–60.

Tarragó, M.N., 1974. Aspectos ecológicos y poblamientoprehispánico en el Valle Calchaquí, Provincia deSalta, Argentina. Revista del Instituto de Antropología5, 195–216.

Tarragó, M.N., 2000. Chacras y pukara: Desarrollos socialestardíos, in Nueva historia Argentina, ed. M.N. Tarragó.Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 257–300.

Tarragó, M.N. & M. De Lorenzi, 1976. Arqueología delValle Calchaquí. Etnía (Museo Etnográfico Munici-pal ‘Damasco Arce’, Olavarría, Instituto de Investi-gaciónes Antropológicas) 23–24, 1–35.

Thompson, J.B., 1990. Ideology and Modern Culture: CriticalSocial Theory in the Era of Mass Communication. Cam-bridge: Polity.

Toren, C., 1999. Mind, Materiality, and History. London:Routledge.

Wolf, E., 1999. Envisioning Power: Ideologies of Dominanceand Crisis. Berkeley (CA): University of CaliforniaPress.