Life in the Atacama: Searching for life with rovers (science overview

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu

Transcript of The Legendary Life of Upamanyu

CROATIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS

Parallels and Comparisons Proceedings of the Fourth Dubrovnik International Conférence

on the Sanskrit Epies and Purânas September 2005

Editedby

Petteri Koskikallio

General Editor

Mislav Jezic Member of the Croatian Academy

of Sciences and Arts (Zagreb)

''8>C0Ct!O

Zagreb

Potporu za ovu knjigu osiguralo je

Ministarstvo znanosti, obrazovanja i Sporta Republike Hrvatske

Urednicki odhor Greg Bailey

• James Fitzgerald , vï.. , Mislav Jezic

Petteri Koskikallio Peter Schreiner

Renate Sôhnen-Thieme Christophe Vielle

Suorganizatori konferencije ïjek za indologiju i dalekoistocne studije, Sveuciliste u Zagrebu

Hrvatsko filozofsko drustvo, Zagreb

Table of Contents

Préface by the General Editor ix

Abbreviations xix

GREG BAILEY Introduction: Parallels and Comparisons 1

MUNEO TOKUNAGA Vedic Exegesis and Epie Poetry: À Note on o/râjt?/MûfâAaran//' 21

MISLAV JEZIC The Tristubh Hymn in the Bhagavadgîtâ 31

GEORG VON SIMSON T h eL u n a rCh a rac t e ro fBa l a r âma /Sa inka r sana 67

NICK ALLEN The Hanging Man and Indo-European Mythology 89

YAROSLAV VASSILKOV A n Epithet in the Mahâbhârata: mahâbhâga 107

ADAMBOWLES Toward a Framing Bhlsma's Royal Instructions: The Mahâbhârata and the Problem of Its 'Design' 121

SIMON BRODBECK The Bhâradvâja Pattem in the MaAâè/ ;âra/a 137

SVENSELLMER Towards a Semantics o f the Mental in the Indian Epies: Comparative and Methodological Remarks 181

DANIELLE FELLER H an u mân ' s Jumps and Their Mythical Models 193

v i i i Table of Contents

A N D R E A S V I E T H S E N

The Reasons for Visnu's Descent in the Prologue to the Krsnacarita of the Harivamsa 2 2 1

P A O L O M A G N O N E

Tejas (and sakti) Mythologemes in the Purânas 2 3 5

K E N N E T H R. V A L P E Y

The Bhâgavatapurâna as a Mahâbhârata Reflection 2 5 7

C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

The Legendary Life o f Upamanyu 2 7 9

H O R S T B R I N K H A U S ^

The 'Purânizat ion ' o f the Nepalese Mâhâtmya Literature 3 0 3

O L G A S E R B A E V A S A R A O G I

A Tentative Reconstruction o f the Relative Chronology o f the Saiva Purânic and :§aivaTantric Texts on the Bas i so f theYog in î - r e l a t ed Passages 3 1 3

R E N A T E S Ô H N E N - T H I E M E

Buddhist Taies in the Mahâbhârata 3 4 9

K L A R A G Ô N C M O A C A N I N

Epie vs. Buddhist Literature: The Case o f Vidhurapanditajâtaka 3 7 3

E V A D E C L E R C Q

The Jaina Harivamsa and Mahâbhârata Tradition: A Preliminary Study 3 9 9

A N D R É C O U T U R E

The Réception o f Krsna's Childhood in Three Jain Sanskrit Texts 4 2 3

N I C O L A S D E J E N N E

Parasurâma as Torchbearer o f a Regenerated Bhârat in a Contemporary Rewriting o f His Narratives 4 4 7

Contributors 4 6 9

Index o f Passages Cited 4 7 3

General Index 4 9 7

APPENDIX: Summaries in Croatian / Sazetci na hrvatskome (prepared by / priredio MISLAV JEÈIC) 5 3 3

Table o f Contents in Croatian / Sadrzaj na hrvatskome 5 4 9

Préface by the General Editor

The spécial thème o f the Fourth Dubrovnik International Conférence on the Sanskrit Epies and Purânas was Parallels and Comparisons. Since Greg Bailey undertook the effort in his Introduction both o f explaining the theoretical importance o f thèse concepts for Indology and philology, and o f presenting the différent ways in which the concepts have been applied in différent articles in thèse Proceedings, I shall limit myself to a summary and factual survey o f articles presented and to some gênerai remarks on the structuring ideas behind this volume. Even i f some éléments are re-peated in both texts, the tasks to be fulfiUed and purposes to be pursued by the theo-retician and critical reviewer among the members o f our Board and by the gênerai editor o f the proceedings w i l l differ sufficiently to hopeililly justify both o f them.

The twenty articles published in this volume approach the topic from différent view^joints o f their authors.

Muneo Tokunaga has looked for ail occurrences o f the term itihàsa in the Mahâbhârata and has found that single itihâsas are in the great majority o f cases intro-duced as examples corroborating some moral or légal injunction or philosophical or religious instruction. He sees the origin o f itihâsas in the arthavâdas o f the Brâhma-nas, and traces the formula o f introduction atrâpi udâharanti back to the Grhya-sûtras, and forward to the Nyâya concept o f udâharana. Thus he has explained the function o f the itihâsas in a surprisingly new light, although in a philologically and statistically so well grounded way that one wonders why nobody had brought the facts together in such way before. We can add that this function o f itihâsas as udâharana could be compared wi th that o f the paradeigmata and exempla in the Works o f ancient orators and Christian preachers and poets.

In the article on the Tristubh Hymn in the Bhagavadgîtâ the typology o f textual répétitions distinguishing the compositional or continuity répétitions on the syn-chronical or syntagmatic axis and reinterpretative or duplication répétitions on the diachronical or paradigmatic axis has permitted the author to argue that not only the majority (as established already in Jezic 1 9 7 9 and 1 9 8 6 ) , but very probably ail the tristubhs in the Gîtâ originated from a religious hymn which must have been com-posed, partly on the basis o f the Epie layer o f the Gîtâ, as an independent poem before it was included in the M B h during the bhakti rédaction o f the Gîtâ. The article is followed by a tentative reconstruction o f the order o f stanzas in the hymn. Wi th this analysis and reconstruction, the question about the Ur-Bhagavadgîtâ inaugurated almost two centuries ago by Wilhelm von Humboldt has been hopefully finally answered.

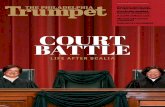

C H R I S T È L E BAROIS

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu

The name of Upamanyu is evoked in a wide range o f literature, usually just the name alone without any information on his life. Appar (7th century), a Saiva saint, and one of the authors o f the Tëvâram hymns, twice speaks o f him as having received the océan o f milk from Siva {Tëvâram 5190, 5806)'. Upamanyu is also the narrator o f the Periyapurânam (1 I th century), in which he is described as an eminent sage, who obtained the océan o f mi lk from Siva and who initiated Krsna.^ He is the named author o f the Sivabhaktavilâsa, a later (probably 16th-century) Sanskrit reworking o f the Tamil Purâna, and he is mentioned several times in the Basavapurâna o f Pâlku-r ik i Somanâtha, a reworking in Telugu (probably 13th century) o f the same text. A Sivastotra is attributed to h im, ' as well as a commentary on the Sivasûtra, called Nandikesvarakârikâ, which represents 'the monist current in âgamic linguistic spéculation' (Seyfort Ruegg 1959: 106). Upamanyu's name is mentioned once in the Rgveda (1,102.9), where he is described as a bard {kâru), and some texts mention a descendant o f Upamanyu {aupamanyava), especially the Chandogya-Upanisad (5.1 l . I and 5.12.1 f) and the Satapathabrâhmana (10.6.1). His name is also mentioned in the Kathâsaritsâgara, where a king, Hemaprabha, praises Siva 'who read-i ly bestowed the océan o f mi lk on Upamanayu who had come to him'.* Lastly, in the Harsacarita o f Bânabhatta, Durvâsâ quarrels with a sage, who is called Mandapâla in ail éditions o f the text except the Bombay édition where this sage is called Upamanyu.'

The numbering is according to the T. V. Gopal lyer's édition (1984). 'This Saint placed his feet on the crown of Yadhava, the king of Dwaraka; Peerless is his service to Siva, the Lord of Bhootas, And it knows neither beginning nor end. The Saint, of yore, was fed by the Océan of Milk by the grâce of Lord Siva, the Father; He grew solely sustained by the milk of Siva's grâce; Myriads of holy saints and suddha yogis sat encircling him' (Ramachandran 1990, verses 24-25). See Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts of the IFP, I I , no. 236.4. Published in the Brhatstotraratnâkara, Nimayasagar Press, Bombay 1965. Balbir 1997: 358. It may not be simply a coïncidence that this king, who performed asceticism to Siva In order to obtaln a son, had resolved that 'either Sarva shows him his satisfaction, or he will glve up his life' (cf. below). Harsacarita, prathama ucchvàsa, p. 2.

280 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

Upamanyu is not, however, simply a name wi th no substance, for a number o f chapters o f the Mahâbhârata, and o f différent Mahâpurânas, Upapurânas and Sthala-purânas, recount the legend of Upamanyu in more or less détail. The aim of this article is to présent the legend of Upamanyu, a sage who is a model for complète dévotion to Siva, on the basis o f a fairly large corpus o f Sanskrit texts and to point out, in the course o f this exposition, the éléments which distinguish the versions o f the narrative from one another. Thèse texts are, in alphabetical order: Cidambaramâhâtmya, Kâhcîmâhâtmya, Kûrmapurâna, Lingapurâna, Mahâbhârata (Anusasanaparvan), Saurapurâna, Skandapurâna'' and, lastly, Sivapurâna (Umâsamhitâ and Vâyavïyasamhitâ). The diversity o f genre here (epic, Purâna, Sthalapurâna) does not allow any viable chronology at this point. The Anusasanaparvan alone poses dating problems which cannot be resolved here. Some suggestions w i l l be put forward in the course o f the exposition, but I otherwise suspend judgement.

Thèse texts offer two distinct narratives: the asceticism of the infant Upamanyu directed to Siva, in order to obtain the océan o f milk, and the arrivai o f Krsna at the hermitage o f the Saiva sage with the intention o f performing asceticism to Siva. Some texts présent only the act o f asceticism the child Upamanyu performed to obtain the océan o f milk: Cidambaramâhâtmya (CMâ 10.14-34), Kâncîmâhâtmya (KMâ 15.1-15)', Saurapurâna (SauP 36.1-46ab) and Skandapurâna (SP 34.70-130). Others présent both narratives, the asceticism of the infant Upamanyu and the asceticism o f Krsna in the hermitage o f Upamanyu: Mahâbhârata ( M B h 13,14-18)^ Lingapurâna (LiP 1,107-108), and Vâyavïyasamhitâ (VâSa 1.34-35; 2.1)'. The Kûrmapurâna (KûP 1,25) and the Umâsarnhitâ (USa 1-3)'° give only the second narrative." Both o f thèse narratives have a simple and stable structure. The diver-

Slumdapurâna (SP) refers to the text as edited by Bhattarai (1988). This text, comprising 50 adhyâyas, is the Sanskrit source of the poem entitled Kâncl-purânam composed in Tamil by Civanânacuvâmi in the second half of the 18th century. It is presented as part of Kâlikâkhanda of Sanatkumârasamhitâ, which is itself presented as part of the SkP. It is differentiated from the KMâ of Vaisnava persuasion, in which a history of Upamanyu, devotee of Visnu (chapter 31) provides no particular information on this sage.

Kinjavadekar's Poona édition (1933). Regarding the choice of this version of the MBh, see Biardeau 1968 and 2002: 17-20. In the Àdiparvan there is also a narrative featuring a character called Upamanyu. Since the context is not Saiva, this need not be taken into considération, even though it does have thematic links with our Upamanyu. See Feller 2004: 209-251 ('Upamanyu's Salvation by the A^vin'). The VâSa is the seventh and last samhitâ of the Sivapurâna. It is the object of my doctoral thesis entitled 'Les enseignements de la Vâyavïyasamhitâ. Doctrine et rituel éivaïtes en contexte purânique' (Paris-III, Sorbonne nouvelle). The USa is the fifth samhitâ in that same édition. See the previous footnote. Though mentioned, the asceticism of the infant Upamanyu is not developed.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 281

gences that arise from one text to another, as shown in the présent paper, are related only to peripheral éléments aiming at inflecting the sectarian religious imprint.

I have limited myself to Sanskrit texts, amongst which the CMâ and the K M â w i l l suffice to link the legend of Upamanyu wi th the médiéval South Indian tradition. I t is by no means rare, however, to find the narrative o f the asceticism of the infant Upamanyu for obtaining the océan o f mi lk in the Tamil Sthalapurâna tradition.'^ I also heard o f the existence o f legends associated with the KsTrârama, a Saiva temple near Narasapuram (West Godavari, Andhra Pradesh), also known as Paalakollu, Dugdapovanam or Upamanyupuram, which I have, however, been unable to include here. Some secondary sources, especially temple booklets, mention that at this place Upamanyu, son o f the sage Kausika, asked Siva for the boon of a great quantity o f mi lk in order to accomplish the daily cuit, and that Siva filled the Ksïrapuskarinî tank wi th mi lk from the océan o f m i l k . "

1. The Infant Upamanyu's Asceticism Directed to Siva

LL Parallel contexts

The textual circumstances which give rise to the recitation o f this legend differ from text to text. In VâSa 1.34, the narrative o f the performing o f asceticism by the infant Upamanyu is instigated by the questions the sages put to Vâyu: How did that child reach the point o f being the propagator o f the treatise o f Siva?'" How, having come to cognition o f the existence o f Siva, did he give himself to asceticism? How, having gained the knowledge during his asceticism, did he obtain the protective ash, which is the eminent power issued from the fire o f Rudra?'' Thèse questions bear witness to a spécifie interest in the transmission o f a body o f knowledge (as denoted by the term sivasâstrapravaktrtâ) and its technical content, here wi th particular regard to the ash. In the LiP, the sages simply ask the Sûta for an account o f how Upamanyu obtained the océan o f mi lk {ksïrârnava) and the 'status o f Ganapati'

'^ Cf for example the Timvârûrppurânam of Alakai Campantamunivar, ed. Cu. Cuvâmi-nâtatecikar. Madras 1894; cited by Shulman (1980). He also mentions a story in which the sage Upamanyu is tumed into a rabbit after Pârvatî puts a curse on him! (One of the foundation myths of the great âaivite temple at Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu.) The Telugu poet Srînâtha (15th century) tells the story in his Bhïmesvarapurânam, but I have not yet been able to consult the Sanskrit sources. VâSa l,34.2ab:

sa katham sisuko lebhe sivasâstrapravaktrtâm I " VâSa 1.34.2cd-3:

katham vâ sivasadbhâvam jriâtvâ tapasi nisthitah II 2 II katham ca labdhavijhânas tapascaranaparvani I rudrâgner yat param vïryam lebhe bhasma svaraksakam II 3 II

282 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

igânapatya)}^ In the SauP, the question the sages ask the Sûta is a replica o f that in the L i P . " As I w i l l show below, thèse three texts (VâSa, LiP, SauP) are connected by a similar degree o f sectarian implication, évident in their unfolding o f the actual asceticism o f Upamanyu. The SP is the only one to indicate that the grâce granted by Siva to Upamanyu is bestowed during an act o f asceticism performed by the god-dess. In the M B h , the narrative o f Upamanyu's asceticism constitutes part o f the narrative o f the asceticism of Krsna, as told by Krsna himself to Yudhisthira. The narrating o f the story aims at achieving Krsna's recitation o f the 1008 names o f Siva as requested by the Pândava. Krsna has leamt thèse names from Upamanyu. In the CMâ, the story o f Upamanyu obtaining the océan o f milk is inserted into the 'cycle o f Vyaghrapada', who is the central subject in chapters 6-10 o f this Sthalapurâna (see Kulke 1970). Lastly, chapter 15 o f the K M â comprises the narration o f the asceticism o f Upamanyu to obtain the océan o f milk. This takes place beside the Liiiga Svâyambhuva which is located to the south o f the Jvâratîrtha at Kâiïcïpura.

1.2. A consistent identity ,,

The genealogical information found in thèse texts is without exception convergent and establishes a stable identity for Upamanyu. In the VâSâ, he is not an ordinary child but the son o f the wise Vyaghrapada'^ and the elder brother o f Dhaumya (VâSa 1.34.1), an identity wi th which the M B h concurs." It would appear that the Tamil Saiva tradition also identifies him as the son o f Vyaghrapada, {Periyapurânam 41).

LiP 1,107.1: puropamanyunâ sûta gânapatyam mahesvarât I ksïrârnavah katham labdho vaktum arhasi sâmpratam II 1 II

The term gânapatya appears twice in the VâSa referring in both cases to a boon from Siva granted first to Daksa (VâSa 1.23.43cd) and then to Upamanyu. This term which appears very frequently in the Purânas is routinely translated by 'commander of troops' of Siva. h is often found in the LiP, notably in a verse (1,81.53) in which it is included in an interesting list:

devatvam vâ pitrtvam vâ devarâjatvam eva ca I gânapatyapadam vâpisakto 'pi labhate narah II 53 II

The term pada here is applied to a spécifie hierarchical position of the devotee. This spécifie status might refer here to the achievement by the devotee of a filial relationship with the divinity. SauP 36.1:

;;,, „ i,! . gânapatyam katham labdham îsvarâd upamanyunâ \ ksïrodadhih katham labdho hy etad àkhyâtum arhasi II 1 II

VâSa 1.34.4: na hy esa sisukah kascit prâkrtah krtavâms tapah I munivaryasya tanayo vyàghrapâdasya dhïmatah II 4 II

" MBh 13,14.1 llcd-112: purâ krtayuge tâta rsir âsîn mahâyasâh II 111 II

,, vyaghrapada iti khyâto vedavedângapâragah I tasyâham abhavam putro dhaumyas câpi mamânujah II 112 II

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 283

Even though neither the LiP nor the SauP mentions Vyaghrapada, they too identify Upamanyu as the elder brother o f Dhaumya (LiP 1,107.32, 108.1; SauP 36.2). The two Sthalapurânas, CMâ and KMâ, specify that his mother is the sister o f Vasistha. The SP gives no information at ail on the genealogy o f Upamanyu.^"

1.3. The origin of the infant 's désire for milk

The circumstances under which Upamanyu begins ardently desiring to drink mi lk are common to ail the texts. Whilst staying, as a child, in a hermitage, Upamanyu tastes mi lk for the first time and upon retuming home he insists on drinking it again. The hermitage belongs to his maternai uncle (mâtulâsrama) Vasistha, except in the M B h , where the référence appears as jnâtikula ( M B h 13,14.118ab), that is, close family.^' When the milk 's origin is mentioned, it is said that it comes from the cow Surabhi (CMâ 10.18; K M â 15.3) or is the remains o f an oblation made by the agnihotr (SP 34.72). The M B h provides a more elaborate version o f the arising o f the child's désire for milk. First, Upamanyu, accompanied by Dhaumya, sees a cow being milked in a hermitage ( M B h 13,14.113-114) and understands at that moment how milk is produced. Next, taken by his father to visit close relatives on the occasion o f a sacrifice, he tastes the mi lk o f 'the divine cow who rejoices the gods' (Surabhi), and he idendfies mi lk as nectar ( M B h 13,14.117cd-l 19). Ordinary milk is thus as-similated wi th divine mi lk in the eyes o f the child. In the LiP and VâSa, his désire is kindled by his envy o f his uncle's son who drinks his fill o f mi lk (LiP l,107.4-5ab; VâSa I . 3 4 . I l - I 2 a b ) .

1.4. The rôle of the mother

A trick that fails. The structure o f the CMâ differs from the other texts at this stage o f the évolution o f the narrative, probably because o f the lesser importance o f the Upamanyu épisode in comparison with that o f the cycle o f Vyaghrapada. Back in his parents' house, Upamanyu is given roots, bulbs and vegetables to eat (CMâ 10.20-22). But he refuses this food and weeps at the memory o f the milk o f Surabhi (CMâ 10.23). His father, seized with compassion for his son, tells h im that he possesses 'nothing except Siva' {akincano 'py aham satyam sivam ekam vinâ vibhum), by whose grâce ail may be obtained. He takes him to the Lihga SrîmQlasthâna at Cidam-baram, but Upamanyu continues to weep (CMâ 10.24-31). Moved by the tears o f the hungry child, Siva bestows upon him the océan o f mi lk (CMâ 10.32-34). So ends the story o f Upamanyu in this Sthalapurâna. Here, Vyaghrapada is the principal actor and the mother does not play the prépondérant rôle she does in the other versions o f

^° When Siva appears to the child in the guise of Indra, he introduces himself as a friend of the child's father whose name is, however, not mentioned. Cf below. A more spécifie meaning of jnâtikula is: 'close patemal family'.

284 C H R I S T È L E BAROIS

the narrative. Upamanyu's status as a child is fixed; he accomplishes no asceticism and his rôle is purely passive.

The other texts offer a common narrative schéma. Upon retuming to his parents' home, Upamanyu clamours for milk. This obstinate and incessant cry for milk on the part o f the child and his mother's inability to satisfy it overwhelms her with sorrow and forces her to think o f a stratagem. She offers her young son artificial milk {krtriman payah), made of powdered grains and water, but the child instantly sees through the subterfuge (KMâ 15.4-5; LiP l,107.5cd-10; M B h 13,14.115-117ab, 120-121ab; SauP 36.4-7ab; SP 34.74-76ab; VâSa 1.34.12cd-20). Thèse passages are more or less developed according to whether or not they emphasize the psycho-logical components o f the situation: the emotional relationship between mother and child, Upamanyu's stubbomness, his mother's helplessness.

The maternai justification. The mother justifies her inability to satisfy her son's désire with a séries o f reasons connected to their conditions o f life. They are ascetics {tapasvin, KM â 15.6; SP 34.76), sages absorbed in méditation (munînâm bhâvitât-manâm, M B h 13,14.122d), their family is poor {daridra, K M â 15.7; SauP 36.8d), and they live in the forest {vane nivasatàm, M B h 13,14.123a; SauP 36.8c), nourish-ing themselves on roots and fruits {kandamûlaphalâsinâm, M B h 13,14.123b). The M B h further develops the thème o f the contrast between the life o f a villager and that o f a forest-dwelling ascetic who neither practises agriculture nor breeds cattle.^^ This thème may also be seen in the différent treatment Upamanyu and his cousin receive, demonstrated by the cousin's being able to drink as much milk as he likes, and, again, in the préparation o f the artificial mi lk by the mother, where the flour is made of grains obtained by gleaning {silonchatalam, KMâ 15.5a; uhchavrttyârjitân bîjân, LiP 1,107.8a; VâSa 1.34.18a). In the CMâ, importance is also given to food obtained by gleaning, such as nourishes Vyaghrapada during his asceticism (CMâ 6.21), and as is prescribed in his hermitage (CMâ 10.8, 22).

In the KMâ, LiP and VâSa, the mother produces the particular explanation for the absence of milk, that they have not honoured Siva in their previous lives." Reduced

MBh 13,14.123cd-126: âsthitânâm nadim divyâm vâlakhilyair nisevitâm II 123 II kutah ksîram vanasthânâm munînâm girivâsinâm I

j . V ,': pâvanânâm vanâsânàm vanâsramanivâsinâm W \24\\ grâmyâhâranivrttânâm âranyaphalabhojinâm\ nâsti putra paya 'ranye surabhïgotravarjiteW 125 11 nadïgahvaraéailesu tîrthesu vividhesu ca I tapasâ japyanityânâm sivo nah paramâgatih II 126 II

In the MBh, a more gênerai argument referring to a fault {dosa) of some kind in previous births is spoken of by Upamanyu during his discourse to Siva, who has come to test him in the guise of Indra; MBhl3,14.191:

yadi nâma janma bhûyo bhavati madîyaih punar dosaih I tasmims tasmin janmani bhave bhaven me 'ksayà bhaktih II 191 II

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 285

to less than a verse in the KMâ {payah kutra tapasvinâm I visesena daridrânâm anârâdhitasulinâm I janmântaresu nah, K M â 15.6d-7c), this argument appears in its most developed version in the VâSa (1.34.22-32). The verses given below are common to the VâSa and the LiP:

Those with neither merit nor dévotion to Siva do not perceive the rivers of jewels of the celestial and infernal régions. Those with whom Bhava is never satisfied do not obtain favours: neither kingdom, nor heaven, nor libération, nor milk-based food. Everything is bom by the grâce of Bhava, and of no other deity. Those devoted to other gods err; they are unhappy and afflicted. How could there be milk here? Mahâ-deva has not been honoured by us.̂ "

The circumstances o f this fault (the fact o f Siva's not having been honoured in the previous births o f the line o f Upamanyu) are nowhere explained. A t most, a distant echo may be found in the CMâ where, during his asceticism, Vyaghrapada, the father o f Upamanyu, failed to honour Siva with the flowers appropriate for the cuit and those he did gather were insect-bitten, withered, and without scent. In despair, he then implored Siva in a discourse in which he présents himself as devoid o f dévotion {bhaktihîna) (CMâ 9.23-28).

In ail the texts (KMâ, LiP, M B h , SauP, SP, VâSa) , except the CMâ, whatever may be the extent and content o f the argumentation, the mother at last reveals to Upamanyu that the satisfaction of ail désire dépends upon dévotion to Siva.^' The

LiP l,I07.12-15ab = VâSa 1.34.22-25ab: tatanî ratnapûrnâs te svargapâtâlagocarâh I bhâgyahtnâ na pasyanti bhaktihînâs caye sive II râjyam svargam ca moksam ca bhojanam ksîrasambhavam I na labhante priyâny esâm no tusyati sadâ bhavah II bhavaprasâdajam sarvam nânyadevaprasâdajam I anyadevesu niratâ duhkhârtâ vibhramanti ca II ksîram tatra kuto 'smâkam mahâdevo na pûjitah I

KMâ 15.8: ksîrecchâ yadi te putra prînayâsu pinâkinam I kâficîksetre visesena prîtir devasya tasya va/ Il 8 II

LiP I,107.15cd-I6ab: pûrvajanmaniyaddattam sivam udyamya vai suta II 15 II tad eva labhyam nânyat tu visnum udyamya vâ prabhum I

MBh 13,14.127-128: aprasâdya virûpâksam varadam sthânum avyayam I kutah ksïrodanam vatsa sukhâni vasanâni ca II 127 II tam prapadya sadâ vatsa sarvabhâvena sankaram I tatprasâdâc ca kâmebhyahphalamprâpsyasiputraka II 128 II

SauP 36.9cd: bhuktis ca sivakârunyâl labhyate nanyathâ suta II 9 II

SP 34.77ab: ârâdhaya mahâdevam sa te sarvam pradâsyati I

VâSa 1.34.28cd: prasâdena vinâ sambho payas tava na vidyate II 28 II

286 CHRISTÈLE B A R O I S

child consequently résolves, at the moment, to perform an act o f asceticism for the god wi th the sole end o f obtaining an océan o f milk.

Upamanyu is initiated by his mother. The maternai figure is thus uniformly at the origin o f the fi l ial asceticism and, moreover, in the M B h and the VâSa, she initiâtes Upamanyu, that is to say, she transmits knowledge to h im before his asceticism. In the M B h , in response to the insistent questions o f Upamanyu ( 'Who is this Mahâ-deva? How is he to be honoured?' etc.)^* she tells h im o f the numerous forms {rûpâny anekâni) o f Siva which she heard about from the sages who, in times gone by, received them from the gods. Thèse 'forms o f Siva' are multiple and paradoxical, and include ail sorts o f divine and demonic créatures, ail sorts o f animais, and some-times terrible or degraded forms ( M B h 13,14.134-166)." In the VâSa, the mother transmits the five-syllable mantra (pahcâksard) 'namah sivâya' to Upamanyu, teach-ing h im about its power and its usage: 'an incomparable means o f protection for the Saivas'. She also confers on him 'ash obtained from his father, prepared in a pure fire, which averts great misfortunes' (VâSa 1.34.41^8). She ends her discourse by saying: 'The mantra I have given you, receive it with my approval. Through practis-ing this murmured prayer, you w i l l immediately obtain protection'.^* The différence between the M B h and the VâSa lies in the nature o f the knowledge transmitted to Upamanyu by his mother. In the former it is a hymn and in the latter the five-syllable mantra.

While the VâSa is not limited to any particular informative style and contains an enormous range o f ritual development, this is not true o f the Epic which is under the domination o f its literary genre to a greater extent. The question remains open as to whether the hymnic recitation has implications beyond its devotional feeling and visualization and whether an initiation is implied. In the LiP, there is only a half-verse, which also appears in the VâSa: 'authorized by her, he accomplished an ex-tremely difficult asceticism'.^' We may note that anujnâta can also carry a technical sensé, signifying the authorization o f the master, or o f Siva, during an initiation

MBh 13,14.129cd-131: prânjalilt pranato bhûtvâ idam ambâm acodayam II 129 II ko 'yam amba mahâdevah sa katharn ca prasïdati \ kutra vâ vasate devo drastavyo vâ kathahcana II 130 II tusyate vâ katharn sarvo rûpam tasya ca kîdrsam I katham jneyahprasanno vâ darsayej janani mama II 131 II

There is a great deal of material relating topâsupatas, in this recitation (MBh 13,14.156-161). VâSa 1.34.49:

mantram ca te maya dattam grhâtia madanujnayâ I anenaivâsu japtena raksâ tava bhavisyati W 49 \l

VâSa 1.34.52ab; LiP l,107.19cd: anujhâtas tayâ tatra tapas tepe sudustaram. The VâSa gives the reading: sa duscaram.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 287

ritual. Similarly, in the SauP we find matur ajnapranoditah, 'guided by maternai authority'. The VâSa clarifies the implicit meaning o f thèse expressions.

1.5. Upamanyu's asceticism

The ascetic practices are briefly described. The KMâ limits itself to paramam tapah, after having named the Jvâratîrtha, and the Mahâl ihga o f Kâflcîpura (KMâ 15.9-10). In the SauP, Upamanyu lives on wind for a hundred years (SauP 36.13) on the mountain Himavat, as he does in the LiP, wherein, however, the length o f his asceticism is not mentioned (LiP I,107.20ab). The description o f the ascetic practices in the M B h (13,14.167-170) is very similar to that in the SP: Upamanyu, facing the Sun, standing on one leg, his mind absorbed in the thought o f Hara, is nourished for periods o f one thousand years by fruits, fallen leaves, water and wind successively (SP 34.78-80). The VâSa alone adds a mention o f worship o f the linga. Upamanyu constructs a platform (prâsâda) wi th eight bricks and an earthenware linga, where he invokes Mahâdeva accompanied by Ambâ and the ganas, and offers h im worship by means o f the five-syllable mantra and offerings o f flowers and leaves. During his asceticism, he is tormented by démons, but protects himself wi th the fervent répétition o f the five-syllable mantra (VâSa 1.34.52-59).

1.6. The test of dévotion

Following the narrative o f the asceticism, three texts (the VâSa, LiP and SauP) give an unusual version o f the testing o f Upamanyu's dévotion by Siva. This forces h im towards a 'yogic suicide', which is représentative o f a particularly sectarian socio-religious atmosphère. The circumstances are as foUows: A t the request o f the gods, Visnu goes to Mandara mountain to complain to Siva o f Upamanyu's asceticism, which is heating up the world. Siva leaves in the form of Sakra for the hermitage o f the sage, in which guise he déclares himself satisfied wi th Upamanyu's asceticism and offers to exécute the child's désire. Upamanyu déclines the offer out o f devotional fidelity to Siva.'" Sakra tries to convince him with a eulogy on his own power and then by denigrating Siva (LiP 1,107.21-36; SauP 36.14-29; VâSa 1.35.1-19). In ail three texts, the key term in the slandering o f the god is nirguna, 'devoid o f [good] qualifies and virtues', 'vicions'. Upamanyu then realizes that he has heard calumny against Siva from the mouth o f Sakra, whom he had identified as a démon come to put obstacles in the way o f his asceticism:

VâSa 1.35.16cd; LiP l,107.33cd: varayâmi sive bhaktim ity uvâca krtânjalih; SauP 36.23ab: bhaktim sûliny ahamyâce sivâdeva na cânyaihâ; cf. MBh 13,14.178:

nâham tvatto varam kânkse nânyasmâd api daivatât I mahâdevâd rte saumya satyam etad bravïmi te II 178 II

288 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

What use is it to say more? Today, I deduce that a serious fault has been committed by me in a previous existence since I have heard calumny against Bhava. From the moment that one hears a calumny against Bhava, one must give up his body and slay the one [who has uttered the calumny], thus going swiftly to the realm of Siva. O inferior god, my désire for milk is now erased. Having killed you with the weapon of Siva I shall abandon this body."

Thèse verses from the VâSa figure integrally in the LiP, which inserts a supplemen-tary verse:

Whoever tears out the longue of one who slanders Siva saves twenty-one générations and goes to the realm of Siva.'^

The SauP also prescribes murder and suicide.'-' Each text mentions that a great fault has been committed, but only the LiP spécifies:

That which was recounted by my mother earlier is the truth; there is no doubt, the r Lord was not honoured by us in previous births.'"

Usually, in the Manusmrti or in the KûP, for example, the instance o f hearing slander against god or one's preceptor does not call for an act o f such violence. It is prescribed only that one should block one's ears or leave that place." In texts which deal wi th the suicide o f a yog in , " 'only a complète disgust wi th enjoyment, or rather mundane expérience, confers authority to terminale l i f e ' , " whereas the slandering o f

^' VâSa 1.35.26-28: bahunâtra kim uktena mayàdyânumitam mahat I bhavântare krtam pâpam srutâ nindâ bhavasya cet II 26 II

, émtvâ nindâm bhavasyâtha tatksanâd eva santyajet \ ; svadeham tan nihaty âsu sivalokam sa gacchati II 27 11

âstâm tâvan mameccheyam ksîram prati surâdhama \ nihatya tvâm sivâstrena tyajâmy etam kalevaram II 28 II

" LiP 1,107.42: yo vâcotpâtayej jihvâm sivanindâratasya tu I trihsaptakulam uddhrtya sivalokam sa gacchati II 42 II

" SauP 36.32cd-34a: tannindâsravanâtpâpâdadhikam tad upeksanât II 32 II

, sivanindâkaram drstvâ ghàtayitvâ prayatnatah \ hatvâtmânam punar y as tu sa yati paramâm gatim II 33 II iti sâstram samuddisya ...

" LiP 1,107.44: purâ mâtrâ tu kathitam tathyam eva na samsayah I ' pûrvajanmani câsmâbhir apûjita itiprabhuh II 44 II

" ManuSm 2.200: guror yatra parîvâdo nindâ vâpi pravartate \ karnau tatrapidhâtavyau gantavyam vâ tato 'nyatah II 200 II

This attimde is confirmed by KûP 2,16.41 (cited by the Sabdakalpadruma in its article on 'nindâ').

36 utkrânti, a term not appearing in any of the texts considered here.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 289

Siva is not envisaged as a pressing motive for suicide. The only similar passage I have found is chapter 39 in the second section of the VâSa. This chapter not only contains prescriptions for the regular kind o f voluntary death ('One takes to fasting and then offers his body in a Saiva fire as a sacrifice, or throws it into tîrthas o f Siva by jumping [into the water] '), and for natural death ('One, weakened by illness etc., who has taken refuge in a temple o f Siva, is liberated when he dies' [VâSa 2.39.47-52]); it also deals wi th a violent death subséquent to hearing a calumny:

He who has killed someone who slanders Siva, i f he is wounded [in combat], let him renounce life, which is difficult to abandon, and he will not be rebom. He who dies [in combat], being incapable of killing someone who slanders Siva, is liberated on the field along with his family for twenty-one générations. No man on the p'ath of libération is comparable with one who renounces life for Siva or for a devotee of Siva.'*

Thus conclude the three chapters 37-39 of the uttarabhàga o f the VâSa dedicated to yoga. I note that the suicide procédure, following upon hearing a calumny, is described at the time o f the testing o f Upamanyu's dévotion:

Then, having taken the terrible ash enchanted with the weapon Aghora, having thrown it at âakra, the sage Upamanyu shouted. Being reminded of the two feet of Sambhu he was ready to bum his own body. Upamanyu, retaining a mental fixation with regard to the fire, remained absorbed."

MVT, p. 437 f; see also testimonia to Mâlinîvijayottara 17.25-34, for a list of éaiva scriptures teaching comparable methods. VâSa 2.39.53-55:

sivanindâratam hatvâ pîditah svayam eva vâ I yas tyajed dustyajân prânân na sa bhûyah prajâyate II 53 II sivanindâratam hantum asakto yah svayam mrtah I sadya evapramucyata trihsaptakulasamyutah II 54 II sivârthe yas tyajet prânân chivabhaktârtham eva vâ I na tena sadrsah kascin muktimârgasthito narah II 55 II

VâSa 1.35.30-31: bhasmâdâya tadâ ghoram aghorâstrâbhimantritam I visrjya sakram uddisya nanâda sa munis tadâ II 30 II smrtvâ sambhupadadvandvam svadeham dagdhum udyatah I âgneyîm dhâranâm bibhrad upamanyur avasthitah II 31 II

LiP 1,107.46^7: bhasmâdhârân mahâtejâ bhasmamustim pragrhya ca I atharvâstram tatas tasmai sasarja ca nanâda ca II 46 II dagdhum svadeham âgneyîm dhyâtvâ vai dhâranâm tadâ I atisthac ca mahâtejâh suskendhanam ivâvyayah II 47 II

SauP 36.36-37: evam uktvâ samâdâya bhasmano mustim âdarât I atharvâstrena tajjaptvâ sakram dagdhum mumoca sah II 36 II vahnidhâranayâtmânam dagdhum samupacakrame I dhyâyan visvesvaram devantparamâtmânam avyayam II 37 II

290 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

The counter-procedure carried out by Siva and Nandi, annulling the yogic act o f Upamanyu, is also described:

Since the brahmin was resolute in this manner, the venerated destroyer of the eyes of Bbaga"*" prevented the mental fixation [with regard to the fire] of this yogi, by means of Saumya. By an injunction of Nandîsvara [i.e. Siva], Nandî, beloved of Sankara, seized in its middle the weapon Aghora which had been shot [and] sent."'

This suicide depended entirely on yogic techniques. The 'bipolar' fixations met wi th here (âgneyî, saumya) are close to the conception o f the four 'fixations' (âgne-yl, vârunï, ïsânï and amrta) presented in the Yogapâda o f the Mataiïgapâramesvara. In the description of the procédure o f the fixation on fire, the âtman is raised up to the fontanel and placed in the dvâdasânta, while the body is reduced to ash (bhasmî-bhûtam sarïram). In this spécifie context, the mental opération is carried out during the daily purification o f the subtle body {dehasuddhi) o f the Saiva initiate. None o f the texts presenting thèse four fixations"^ envisages the possibility o f the âtman not reintegrating into the body. I have found only a single allusion dealing wi th suicide. In the commentary o f Bhattanârâyanakantha on the Kriyâpâda o f the Mrgendrâgama (2.5) a référence to a missing passage from the Caryâpâda spécifies that one should not give up his body even i f misérable {na ca dehaparityâgah kâryo duhkhe 'py upa-sthite).

Ritual suicide subséquent to hearing a calumny against Siva is sufficiently unusual for its présence alone to give évidence o f the aims o f the text, and o f the socio-religious conditions o f its recitation in the state in which it has come down to us. Illustrating a dévotion quite out o f the common, it is a strong indication o f a sectarian position, especially in the case of the VâSa. There are traces o f this practice in the Vîrasaiva tradition; for example, in his Basavapurâna, (chapter 7 on the history

40 Siva is called 'the slayer of Bhaga' in référence to an épisode in the account of the destruction of Daksa's sacrifice. VâSa 1.35.32-33:

evam vyavasite vipre bhagavân bhaganetrahâ I vârayâm âsa saumyena dhâranâm tasya yoginah \i 22 W tad visrstam aghorâstram nandïsvaraniyogatah I jagrhe madhyatah ksiptatn nandî sahkaravallabhah W 33 W

LiP 1,107.48^9: • • • • evam vyavasite vipre bhagavân bhaganetrahâ I vârayâm àsa saumyena dhârariâm tasya yoginaii W 4S W atharvâstram tadâ tasya samhrtam candrakena tu I kâlâgnisadrsam cedan niyogân nandinas tathâ II 49 II

SauP 36.38-39ab: evam vyavasite tasmin pinâkî nîlalohitah \ saumyadhâranayâgneyîm vârayâm âsa sarikarah W 3S W sailâdinânyathâ tatra samhrtam câtibhîsanam I

N. R. Bhatt gives the parallel passages from Rauravâgama, Kiranâgama, and Agni-purâna, in the Mrgendrâgama, p. 261.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 291

of Allayya and Madhupayya), Pâlkuriki Somanâtha uses, word for word, the argument in favour o f the need to die after hearing a calumny, and this exemplary con-duct is ascribed specifically to Upamanyu, a paragon o f dévotion (Narayana Rao 1990: 262 ff).

Neither this practice nor even the intervention of Visnu asking Siva to put an end to the asceticism o f Upamanyu figures in the KMâ, M B h or SP, where it is said only that Siva appears in the form of Sakra to test the devotional faith o f Upamanyu, who does not consider Indra as a râksasa having come to put obstacles in the way of his asceticism but simply makes him privy to his f i rm and exclusive dévotion to Siva. In the M B h , the refusai o f a boon offered by Indra is an occasion for Upamanyu to chant a long panegyric to Siva,"' which describes the supremacy o f the god in his multiple aspects ( M B h 13,14.193-235). The SP puts Upamanyu to a triple test which emphasizes the existence of a form o f Siva that transcends the entire panthéon, in-cluding Rudra. Siva appears first in the form of Indra, and twice tries to convince Upamanyu wi th emotional arguments, presenting himself as a friend o f his father"" and offering to fulfi l his vow, but Upamanyu refuses. Rudra then appears to the child, who déclares himself to be attached {anâsritya) to no object, be it human or divine, and asks him for the océan o f milk, but Rudra cannot give him anything i f he is attached to nothing here on the Earth, and so asks him to reconsider his vow. Upamanyu is adamant and Rudra disappears. Lastiy, the god appears in the form of Brahmâ, but Upamanyu refuses any vow not given by Mahâdeva and Brahmâ disappears to give place to Siva (SP 34.81cd-l 13).

/ . 7. The manifestation of the god; the boons

Upamanyu, who has successfuUy passed the test o f dévotion, obtains a 'vis ion ' o f Siva. In neither o f the two Sthalapurânas is there any description o f the god. In the SauP Siva appears alone"' and in the SP in a terrible form, accompanied by his ganas.*^ In the M B h and the VâSa he appears in the company of the goddess, both

Upamanyu replies to Sakra's question (MBh 13,14.192): kah punar bhavane hetur îse kâranakârane I yena sarvâd rte 'nyasmâtprasâdam nâbhikânksasiW 192 II

SP 34.86: bhavato me pitâ vipra sakhâbhût paramah purâ I tena snehena drstvâham bhavantam tapasi sthitam I klisyamânam ihâyâto brûhi kim te dadâny aham II 86 II

Following the refusai of Upamanyu, Sakra raises his bid (SP 34.89): aharn pitus te snehena ihâyâto mahâvrata I dharmato hi suto me tvam brûhi tasmâd dadâmy aham II 89 II

SauP 36.40cd-41ab: paficavaktram dasabhujam bâlendukrtasekharam II 40 II dvîpicarmaparîdhânam triparicanayanam vibhum I

292 C H R I S T È L E BAROIS

seated upon the Bull . The VâSa gives a succinct description (VâSa 1.35.37-38), and the M B h an extensive one, regarding which I recall that it is Upamanyu himself who relates it to Krsna. Siva and U m â are seated on Nandî; the god's weapons are an-thropomorphic, and his entourage comprises Brahmâ, Nârâyana, Skanda and numerous rsis ( M B h 13,14.239-287). In the LiP, the god is accompanied by the goddess, but it is unclear whether this is somesvaramûrti or ardhanârîsvaramûrti.

The manifest Siva grants Upamanyu the océan o f mi lk and other boons such as immortality, omniscience, etemal youth, absence of illness, etc. (KMâ 15.12; LiP 1,107.51-58; M B h 13,14.356-363; SauP 36.42cd-43ab; SP 34.118-122; VâSa 1.35.41-45). Except in the SP, additional boons are requested by the child. In the SauP, etemal dévotion to Siva, in the LiP and the VâSa, etemal dévotion as well as the etemal présence o f the god with Upamanyu,"' and in the KMâ, the etemal présence o f the god in the linga at Kâiïcïpura."* In the M B h thèse boons are formulated by Upamanyu after a eulogy to Mahâdeva. He desires etemal dévotion to the god, knowledge o f the past, présent and future, the delight o f the océan o f milk for himself and those close to him, as wel l as the etemal présence o f the god in his hermit-

SP 34.115-117ab: tryakso jatî visâlâksah kundalî dïptalocanah I jvâlâmâlâdharah srïmân bhujagâbaddhamekhalah II 115 II sarpayajfiopavïtî ca vyâghracarmâmbaracchadah I krsnâjinottarîyas cakamandaludharas tathâ W \\6\\ dandî sûlï mahâhâso ganapair bahubhis vrtah I

SauP36.44ab: bhaktim eva virûpâkse punah punar ayâcata I

VâSa 1.35.55cd-56: svabhaktim dehi paramân divyâm avyabhicârinîm II 55 II sraddhân dehi mahâdeva svasambandhisu me sadâ I svadâsyamparamam sneham sânnidhyam caiva sarvadâ II 56 II

LiP 1,107.63 prasîda devadevesa tvayi câvyabhicârinï I sraddhâ caiva mahâdeva sânnidhyam caiva sarvadâ II 63 II

KMâ 15.13-14ab: so 'pi vavre varam cânyam bhaktiyuktena cetasâ I asmin svàyambhuve linge tava sânnidhyam îsvara II 13 11 sarvadâstu krpasindhor bhuktimuktipradam nrnâm I

MBh 13,14.352-354: yadi deyo varo mahyam yadi tusto 'si me prabho I bhaktir bhavatu me nityam tvayi deva suresvara II 352 II atîtânâgatam caiva vartamânam ca yad vibho I jânîyâm iti me buddhisprasâdât surasattama II 353 II ksïrodanam ca bhunjïyâm aksayam saha bândhavaih I âsrame ca sadâsmâkam sânnidhyamparamas tu te II 354 II

Cf also the parallel passage in USa 1.46-49.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 293

Even i f it is not a conclusive point, we should note that the 'présence o f the god ' ' ° is at the heart o f the dévotion expressed by the Tamil saints (Nâyanmâr) , most completely expressed in the localization o f sivaloka in the Periyapurânam, as Anne E. Monius has noted:

Civalokam, literally 'the world of Siva', in fact, lies not simply in the heavens or in Siva's wondrous abode of Mount Kailâsa, Cekkilar emphasizes, but anywhere that devotees gather to adore the lord. The lord enshrined at Tiruppunkur for example, is named Civalokan, 'he who belongs to the world of Siva', implying that the temple itself is Civaloka. (Monius 2004: 190)

The Sthalapurâna tradition represents the most remarkable development o f the devotional expression of the présence o f the god.

Upamanyu 's intimate relationship with Siva and Pârvatî. In the VâSa and the LiP, which have verses in common, the boons o f Siva as regards the profusion of foods offered to the child are o f an abundance unparalleled in the other texts. Not only the océan o f milk, but an océan o f yoghurt, one o f clarified butter, one o f honey, moun-tains o f sweetmeats, and an océan o f nectar o f fmits, etc. are bestowed. In both thèse texts the affection shown by Siva and Pârvatî toward Upamanyu is that o f parents toward their child. Siva w i l l think o f him from now on as his son, Pârvatî thus be-coming his mother," and the god lifts the child up so that the goddess can kiss h im on the head."

This same fil ial relationship to the god defines the type of dévotion represented in the Tamil tradition by Nânacampantar , one o f the three authors o f the Tëvâram," who is considered by that tradition as having attained a state o f identification {sa-rûpa) wi th Subrahmanya. The resemblance between Upamanyu and Nânacampantar is, in fact, striking. Both are children and both receive the océan o f milk after having a vision o f the couple Siva-Pârvat l

The épisode o f the manifestation o f the god and the boons as presented in both the VâSa and the LiP thus links the narrative o f the asceticism of the infant Upa-

The 'présence of the god' here refers to the term sânnidhya; in the Tamil tradition we more often find sâmîpam. LiP l,107.54cd-57 = VâSa 1.35.42-45ab:

upamanyo mahâbhâga tavâmbaisâ hi pârvatî I maya putrîkrto 'sy adya dattah ksîrodadhis tathâ I madhunas cârnavas caiva dadhnas cârnava eva ca I âjyodanârnavas caiva phalalehyâriyavas tathâ I apûpagirayas caiva bhaksyabhojyârnavah punah I pitâ tava mahâdevah pitâ vaijagatâm mune I mâtâ tava mahâbhâga jaganmâtâ na samsayah I

VâSa 1.35.47: evam uktvâ mahâdevah karâbhyâm upagrhyatam I mûrdhny âghrâya sutas te 'yam iti devyai nyavedayat II 47 II

See François Gros's introduction to Vol. I of Gopal lyer's édition.

294 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

manyu wi th the Tamil devotional tradition that developed out o f the hymns o f the Tëvâram and was perpetuated in the much later philosophical developments o f Tamil Saivasiddhânta. In the commentary o f Sivajfiânasiddhiyar (13th century) on the Siva-

jnânabodha, we find the présentation o f four relationships which jo in the bhakta to the divinity: dâsamârga, master-servant relationship; putramârga, parent-child; sahamârga, friend to friend; and sanmârga, unconditional union'", thèse catégories being arranged, respectively, according to the personal devotional expression o f the devotee: cârya, kriyâ, yoga and jhâna. The Timmantiram o f Tirumular (probably lOth century) contains thèse same developments" in a more poetic register.

2. Krsna's Asceticism in the Hermitage of Upamanyu

2.1. Parallel contexts

The narrative o f the asceticism performed by Krsna to obtain a son"^ is the second to evoke Upamanyu, no longer as a child devotee to Siva but as a Saiva master at the head of a hermitage. As before, the textual circumstances which give rise to the recitation differ from text to text. In the first chapter o f the second section o f the VâSa, the sages désire to hear how Krsna, having accomplished the pâsupatavrata, obtained pâsupata knowledge." This second account introduces a teaching in the form of a treatise on doctrine and ritual (âgama or paddhati) which takes up the greater part o f the second section o f the VâSa (chapters 2-39) and, according to its content, is a Saivasiddhânta exposition ( in particular, o f the ritual procédure for in i tiation o f the Saiva devotee). Upamanyu, a pâsupata master, is the propagator o f this treatise'* whilst Krsna is his disciple. Chapter 1,108 o f the LiP, which foUows the account o f the asceticism o f the infant Upamanyu, opens wi th a question similar to

Commentary on 8th sûtra, 270-274. " Timmantiram, Tantra 5. " The VâSa gives the etymological explanation of the name of the son of Krsna and

Jâmbavatî, Sâmba, thus called because he was bestowed on them by Mahâdeva accompanied by Ambâ (VâSa 2.1.25cd-26ab):

yasmât sâmbo mahâdevah pradadau putram âtmanah II 25 II tasmâj jâmbavatisûnum sâmbam cakre sa nâmatah I

" VâSa2.1 .10d- l l : ... krtvâpâsupatam vratam II 10 II prâptam ca paramam jhânam iti prâgeva susruma\ katham sa labdhavân krsno jnânam pâsupatam param II 11 II

58 " . . . . Another source mentions the fact that Upamanyu is in connection with the propagation of a text. Chapter 235 of the Uttarakhanda of Padmapurâna, entitled 'The birth of heretics' (pàsandotpattivarnanam), cites Upamanyu in a list of ten tamasic sages to whom Siva recited the bad Purânas and treatises, so that their transmission by thèse 'bad sages' would mislead the démons.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 295

that o f the V â S a . " I recall that in the M B h the account o f the asceticism of Krsna leads to the recitation, at the request o f Yudhisthira, o f the 1008 names o f Siva. The structure o f the narrative is as foUows: Yudhisthira asks Bhîsma to recite the names o f Siva (MBh, 13,14.1-2). Bhîsma, déclares himself incompétent, praises the supremacy o f Siva and says that only Krsna, who has accomplished asceticism for Siva, is compétent (14.3-16). Bhîsma conveys Yudhisthira's request to Krsna (14.17-21) who obliges (14.22-24). In the opening o f the USa, the sages ask the Sûta for a rendering o f 'the deed of Sambhu, which consists o f varions stories included in the Umâsarnhitâ'.^ The Sûta then says that he is going to recount to the sages specifically what Sanatkumâra told Vyâsa who asked the same question (USa 1.4-5), namely, what had Upamanyu told Krsna, when he came to accomplish asceticism for Siva in order to obtain a son (USa 1.4-8). A t last, in chapter 25 o f the first part o f the KûP, the account o f the asceticism o f Krsna for obtaining a son is recounted by the Sûta without any particular question from the audience being mentioned. The chapter continues on from the preceding one, which gives the Yadu lineage.*' The Sûta introduces the account by saying that Krsna had performed terrible ighora) asceticism with the aim of obtaining a son (KûP 1,25.1-2). Besides thèse four texts, in chapter 1,69 o f the LiP we should note a short passage relating to the asceticism of Krsna, and dealing wi th the genealogy and the life o f Krsna from a Saiva point o f view (LiP 1,69.73-77). Surprisingly it désignâtes the hermitage in which Krsna accomplished his asceticism as being that o f Vyaghrapada, although Upamanyu is not mentioned.

2.2. The meeting of Krsna and Upamanyu

The VâSa, LiP, M B h and USa share a similar and rather simple narrative structure o f Krsna's asceticism. This includes a motive for undertaking asceticism for Siva, the meeting between Krsna and Upamanyu, the initiation and asceticism o f Krsna, the vision o f the god and the bestowing o f the anticipated favour. The différence between thèse texts is again the présence or absence of specialized ritual éléments, though to a lesser extent than in the narrative o f Upamanyu's asceticism.

Description of the sage. Ai the time of Krsna's arrivai at the hermitage o f Upamanyu, the latter is termed a sage (muni, LiP 1,108.4) or maharsi (USa 1.6), king o f

LiP l,108.1-2ab: drsto 'sau vâsudevena krsnenâklistakarmanâ I dhaumyâgrajas tato labdham divyâm pâsupatam vratam II 1 II katham labdham tadâ jhânam tasmât krsnena dhïmatâ I

USa 1.3; athomâsamhitântahsthanânâkhyânasamanvitam I brûhi sambhos caritram vai sâmbasya paramâtmanah II 3 II

Colophon: iti srlkûrmapurâneyaduvamsânukîrtanam nâma caturvimso 'dhyâyah II

296 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

sages, best o f yogis (munîndra, yoginâm srestham, KûP 1,25.26), and is described in the VâSa as having ail his limbs brilliant with ash, his head marked with three Unes, and adomed wi th rosaries o f rudra seeds, omamented by a knot o f braided hair.''^ In the M B h he is a lord with matted hair, illuminating by his luminous energy and asceticism, like fire, followed by disciples, peaceful, young, and like the bull o f the Brahmins." His hermitage is the subject o f a great deal o f description. In every case, Upamanyu has the status o f Saiva master, a repository o f knowledge. It is thus that Krsna considers him, honouring him wi th a salutation and, as is the rule for respect-ing the guru, performing a triplepradaksina around him (LiP 1,108.5; VâSa 2.1.16).

Initiation of Krsna. The initiation o f Krsna by Upamanyu marks the différence between the narratives in terms o f ritual development. In the VâSa and the LiP, at the very sight o f the sage, ail stain adhering to Krsna, that bom o f Mâyâ and o f karman, is wiped out." I f we refer to the définition in chapter 15 o f the VâSa dealing wi th initiation, we shall see that it is a 'direct' (sâksât) initiation, 'relative to Sambhu' (sâmbhavT), which is 'the clear consciousness which brings about the destmction o f bonds obtained only by the regard o f the gum through touch or word'.*' Upamanyu next covers Krsna wi th ash, using the mantra 'agnir iti\' has him accomplish the twelve-month pâsupata observance, and transmits the suprême knowledge to him.*' Thus, in both texts, Krsna accomplishes a pâsupata vow under the direction o f

62

63

65

66

67

VâSa 2.1.14: bhasmâvadâtam sarvângarn tripundrânkitamastakam I rudrâksamâlâbharanam jatâmandalamanditam II 14 II

MBh 13,14.63cd-64: pravisann eva câpasyam jatâcîradharamprabhum II 63 II tejasâ tapasâ caiva dlpyamânam yathânalam I sisyair anugatam sântamyuvânam brâhmanarsabham II 64 II

VâSa 2.1.17: tasyâvalokanâd eva muneh krmasya dhïmatah I nastam âsïn malam sarvam mâyâjam kârmam eva ca II 17 II

The version of the LiP (1,108.6) differs a little: tasyâvalokanâd eva muneh krsnasya dhïmatah I nastam eva malam sarvam kâyajam karmajam tathâ II 6 II

('Due to the sight of the sage, ail stain of Krsna the intelligent, bom of his body and his karman, was destroyed'.) VâSa 2.15.7:

guror âlokamâtrena sparsât sambhâsanâd api I sadyah samjriâ bhavej jantoh pâsopaksayakàrinï II 7 II

C f Atharvasira-Upanisad 5. VâSa 2.1.18-19:

tatah ksïnamalam krsnam upamanyur yathâvidhi I bhasmanoddhûlya tam mantrair agnir ity âdibhih kramât II 18 11 atha pâsupatam sâksâd vratam dvâdasamâsikam I kârayitvâ munis tasmai pradadau jhânam uttamam II 19 II

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 297

Upamanyu and on completion o f this receives pâsupata knowledge. Chapters 2-39 o f the second section o f the VâSa represent precisely the exposition o f this knowledge, taught to Krsna by Upamanyu, in the form of a religious treatise o f the Saivasiddhânta school - a cohérence which the LiP is not able to sustain since the material in it is widely scattered. The M B h , too, describes Krsna as the disciple o f Upamanyu. Though it only briefly mentions the initiation without specialized ritual development, followed by performance o f ascetic acts ( M B h 13,14.379cd-381cd), it gives, as a persuasive argument, an extensive enumeration o f the sages and divinities who have accomplished fruitful asceficism for Siva ( M B h 13,14.62-108). On the évidence o f the three chapters conceming this épisode, the USa borrows numerous verses from the M B h . Chapter 2 is more or less a replica o f the enumeration from the M B h . Chapter 3 is distinguished by the transmission to Krsna o f the mantra 'namah sivâ-ya' and the prescription o f its murmured recitation.

2.3. The case of the Kûrmapurâna

The narrative o f the asceticism of Krsna presented in chapter 1,25 o f the KûP is sin-gularly distinguished by Vaisnava dévotion that shows through it, manifested by praises to Krsna. The accent is on the power o f Krsna, who is identified with Visnu (carrying the conch, the dise and the mace) and with Nârâyana, and who is praised as such by the ascetics o f the hermitage. Upamanyu himself pays homage to Krsna as 'Visnu unmanifest, who has taken on the form o f a disciple'.** The very motive for the asceticism has altered as Krsna desires a vision o f Siva, but not to obtain a son. Krsna obtains, not only a vision o f Siva but also o f Visnu, who stands beside Siva and in whom Krsna recognizes himself and contemplâtes himself by an effect o f infinité mirroring.*' Thèse éléments corroborate the thesis o f the KûP being o f pâhcarâtra inclination (Hazra 1940: 57-75) and being reappropriated afterwards by the pâsupatas; and chapter 1,25 o f the KûP illustrâtes how the inclusion o f a narrative moti f (here the initiation o f Krsna into Saivism) inflects the initial doctrine of a text.

LiP 1,108.7-8: bhasmanoddhûlanam krtvâ upamanyur mahâdyutih I tam agnir iti viprendrâ vâyur ity âdibhih kramât II 7 II divyâm pâsupatam jhânam pradadau prïtamânasah I muneh prasâdân mânyo 'sau krsnahpâsupate dvijâh II 8 II

KûP l,25.29ab: visnum avyaktasamsthânam sisyabhâvena samsthitam I

KûP 1,25.55: tadânvapasyad girisasya vâme svâtmânam avyaktam anantarûpam I stuvantam ïsam bahubhir vacobhih sahkhâsicakrânvitahastam âdyam II 55 II

298 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

The épisode o f the initiation o f Krsna by Upamanyu, which dénotes a polemical contest between Krsna and Saiva bhakti, gained a réputation in the Vïrasaivite miUeu. Thus the Basavapurâna"' stipulâtes,

because he was initiated into the Saiva creed by the sage Upamanyu, Visnu himself wears a sapphire linga, which he puts in his box and worships.

3. Conclusion

Here the exposition o f the legend o f Upamanyu ends. This study o f the life o f this character, which has received very little scholarly attention up until now, is an occasion to raise broader questions. I retum now to some o f the main aspects discussed above, involving both formai issues and issues o f content.

The comparative reading corroborâtes what we already know. The USa borrows extensively from the M B h , the KiiP is distinguished by its Vaisnava provenance, the LiP and the VâSa contain similar pâsupata material, even though there is in the LiP no such cohérent exposition o f this knowledge as is provided by the VâSa. The great number o f verses the LiP and the VâSa have in common raises the question, yet to be resolved, o f the relation between thèse two texts. Without a deeper examination o f the relevant passages one cannot décide i f the chapters o f the LiP are a condensation o f those o f the VâSa, or i f the VâSa interpolâtes from the L i P . "

When they coexist in the same text, the link between the two narratives is not systematic. In the LiP and VâSâ they follow one another. In the M B h , the asceticism o f Upamanyu is inserted into that o f Krsna. The ordering o f the two narratives is more complex here wi th respect to temporal organization and the strata o f the dialogues. This same structure is also perceptible in the USa. Yet, in the KûP, only the asceticism of Krsna is actually related, but the narrative o f the asceticism o f Upamanyu is mentioned. However that may be, the narrative o f the obtaining o f the océan o f mi lk is prépondérant, the relevant texts being more abundant and probably earlier. The mention o f Upamanyu's asceticism in the KMâ, CMâ and Periya-

'"̂ Narayana Rao 1990: 229 (the story of Sankaradâsi in chapter 6). The chronological place of the LiP in relation to the VâSa is a controversial question. Regarding the myth of Daksa, the question has been discussed by Mertens (1998: 231) and Bisschop (2006: 189, n. 219), who bases himself on the convergences with the SP to conclude that the LiP is prior to the VâSa. The case of the legend of Upamanyu is différent. The SP, the narrative of which is very différent from the LiP and the VâSa, cannot be called on in support of this daim. My first intuition on reading thèse two texts is to argue for the LiP as a condensation of the VâSa. But this is just an intuition, based on the fact that the information provided by the LiP appears to me to be partial, and that chapters 107 and 108 are the last ones of the first part of LiP, which makes them seem like an addifion. This remark calls for confirmation or invalidation, which can only come about through the comparative study of thèse chapters, now underway. I would not be surprised i f this study did not provide a décisive answer.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 299

purânam is strong évidence o f its blossoming, i f not o f its origin, in the South. Additionally, the importance in the VâSa and LiP o f the notion o f the 'p résence ' o f the god and the fi l ial relation between Upamanyu and the pair o f Siva-Pârvatî tend to bring the legend doser to the tradition o f the Saivite saints.

The isolation of, and comparison between, the narrative séquences thus bears witness to marked représentations o f Saivism. Without re-orientating the gênerai narrative schéma, the présence or absence of rites and the précise exposition o f their procédure détermine the sectarian degree o f the texts. Upamanyu is the central figure in thèse ritual acts, essentially represented by two thèmes: initiation and 'yogic suicide'. The présence o f extrême rituals specifically characterizes this sectarian de-gree.'^

Emotional bhakti is the canvas upon which thèse particulars are drawn. In this respect, there is also a differentiation operating through a mythological or eulogic extension, as in the M B h . We have touched only lightly upon the fact that the présence or absence of eulogies is also a major criterion o f differentiation. A formai statement o f praise is by its nature opposed to a technical exposition o f rites, etc., but its présence may also be interpreted as implying a ritual teaching, especially when it is found in the same place as the initiation in two texts whose narrative structure is similar. Upamanyu is associated wi th the transmission o f Saivite knowledge, as indi-cated by the term sivasâstrapravaktrtâ. In the M B h and USa this knowledge is represented by the litany o f the 1008 names o f Siva.

Bibliography

Primary sources

CMâ [Cidambaramâhâtmya] The Chidambara Mâhâtmyam. Edited & published by Sastracharya, Panditaraja Somasekhara Dikshitar, Chidambaram. ICadavasal: Sri Meenakshi Press, 1971.

[Harsacarita] Harsacarita of Bânabhatta. Text ofUcchvâsas I-VIH. Ed. by Pandurang Vaman Kane. Delhi: MLBD,'1965"

KMâ [Kâhcîmâhâtmya] Transcript no. D2381 in Telugu script, 251 pages. (See Descriptive Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, IV.2. Madras.) Copy of the Srikurvetinagaram édition, 1889. (Telugu script.)

In this regard, it might be fruitful to try to establish a classification amongst the rites in the purânic and epic contexts according to the following criteria: 'induced rite', that is, a rite whose présence is understood, 'rite integrated into the narration' which usually appears in the form of a paraphrase, and 'rite additional to the narration', which is an autonomous technical séquence not directly involved in the progression of the narrative (there may be extensive development, but it may equally be indicated by a technical term alone).

300 C H R I S T È L E B A R O I S

KOP [Kûrmapurâna] The Kûrma Purana. Ed. by A. S. Gupta. Varanasi: All-India, Bombay: Laksmivenkatesvara Press, 1926 (V.S. 1983).

LiP [Lingapurâna] Lihga Purâna of Sage Krsna Dvaipâyana Vyâsa. With Sanskrit Commentary èivatosiixîof Gariesa Nâtu. Ed. by J. L. Shastri Delhi: MLBD, 1980.

MBh Srîmanmahâbhâratam, part V I : XII I Anusasanaparvan. With the Bhâralabhâva-dîpa by Nîlakantha, Edited by Pandit Râmacandrasâstrî Kinjavadekar. Poona: Shankar Narahar Joshi, Chitrashala Press, 1933.

[Mrgendrâgama] Mrgendrâgama. Kriyâpâda et Caryâpâda avec le commentaire de Bhatta-Nârâyariakaritha. Ed. by N. R. Bhatt. (Publications d'Institut Français d'Indologie, 23.) Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry, 1962.

MVT [Mâlinïvijayottaratantra] The Yoga of the Mâlinîvijayottaratantra. Chapters 1-4, 7, 11-17. Ed. & trans. by Somadeva Vasudeva. (Collection Indologie, 97.) Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry, 2004.

SauP [Saurapurâna] Saurapurânârn vyâsakrtam. Ed. by Kâsinâtha Éâstrî 'Lele'. (Ânandâsrama Sanskrit Séries, 18.) Poona: Ânandâsrama, 1889 (saka 1811).

SP [Skandapurâna] Skandapurânasya Ambikâkhartdah. Ed. by Krsnaprasâda Bhatta-râî. (Mahendraratna-granthamâlâ, 2.) Kathmandu: Mahendra Sanskrit University, 1988.

[Tëvâram] V. M. Subramanya Ayiar, J. L. Chevillard, S. A. S. Sarma, Digital Tëvâram. (Collection Indologie, 103.) Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry, 2007. Tëvâram. Hymnes sivaïtes du Pays tamoul. Edition established by T. V. Gopal lyer, under the direction of François Gros. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry, 1984.

USa [Umâsarnhitâ] The 5th sarnhitâ in: Srîs'ivamahàpurânam, Ed. by Shri Ramtej Pandey. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Vidyabhawan, 1998.

VâSa [Vâyavîyasarnhitâ] The 7th sarnhitâ in: Srîsivamahâpurârtam. Ed. by Shri Ramtej Pandey. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Vidyabhawan, 1998.

Secondary sources

BALBIR, Nalini 1997. Océan des rivières de contes. (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade) Paris: Gallimard.

BIARDEAU, Madeleine 1968. Some more considérations about textual criticism. Purâna 10.2: 115-123. 2002. Le Mahâbhârata. Un récit fondateur du brahmanisme et son interprétation, I - I I . Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

BISSCHOP, Peter C. 2006. Earfy Saivism and the Skandapurâna. Sects and Centres. (Gronin-gen Oriental Studies, 21.) Groningen: Egbert Forsten.

FELLER, Danielle 2004. The Sanskrit Epies ' Représentation of Vedic Myths. Delhi : MLBD. HAZRA, Rajendra Chandra 1940. Studies in the Purânic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs.

Dacca: University of Dacca (Reprint: Delhi: MLBD, 1975.) KULKE, Hermann 1970. Cidambaramâhâtmya. Eine Untersuchung der religiongeschichtlichen

und historischen Hintergrûnde fîir die Entstehung der Tradition einer siid-indischen Tempelstadt. (Freiburger Beitrage zur Indologie, 3.) Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

The Legendary Life of Upamanyu 3 0 1

MERTENS, Annemarie 1998. Der Daksamythus in der episch-purânischen Literatur. Beob-achtungen zur religionsgeschichtlichen Entwicklung des Gottes Rudra-Siva im Hinduismus. (Beitrage zur Indologie, 29.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

MONIUS, Anne E. 2004. Siva as heroic father: Theoiogy and hagiography in médiéval South India. Harvard Theological Review 92.2: 165-197.

NARAYANA RAO, Velcheru (trans.) 1990. Siva's Warriors. The Basava Purâna of Pâlkuriki Somanâtha. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

RAMACHANDRAN, T. N . (trans.) 1990. St. Sekkizhar's Periya Purânam. Thanjavur: Tamil University.

SEYFORT RUEGG, David 1959. Contributions à l'histoire de la philosophie linguistique indienne. Paris: Boccart.

SHULMAN, David Dean 1980. Tamil Temple Myths. Princeton: Princeton University Press.